Abstract

This paper reviews the results of more than a hundred small archaeological “test pit” excavations carried out in 2013 within four rural communities in eastern England. Each excavation used standardized protocols in a different location within the host village, with the finds dated and mapped to create a series of maps spanning more than 3500 years, in order to advance understanding of the spatial development of settlements and landscapes over time. The excavations were all carried out by local volunteers working physically within their own communities, supported and advised by professional archaeologists, with most test pits sited in volunteers’ own gardens or those of their friends, family or neighbors. Site-by-site, the results provided glimpses of the use made by humans of each of the excavated sites spanning prehistory to the present day; while in aggregate the mapped data show how settlement and land-use developed and changed over time. Feedback from participants also demonstrates the diverse positive impacts the project had on individuals and communities. The results are presented and reviewed here in order to highlight the contribution archaeological test pit excavation can make to deep mapping, and the contribution that deep mapping can make to rural communities.

Keywords:

archaeology; excavation; test pits; rural settlement; rural communities; England; prehistoric; Roman; Anglo-Saxon; medieval 1. Introduction

Deep mapping, as epitomised by William Least Heat-Moon in PrairyErth [1], encompasses a range of approaches—cartographic, geographical, historical, literary, philosophical, scientific, anthropological, sociological and theological—to weave multiple strands of evidence, observation, impression and memory into a distillation of place which is part local history, part biography, part travelogue [2]. Heat-Moon’s work occupies just one point within a vast and wide-ranging multi-disciplinary profusion of diachronically inflected, socially informed studies of place, whose various practitioners might or might not identify themselves variably as local historians, writers, performers, film-makers, philosophers, farmers or householders [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. While travel writing, folklore studies and local history have often lain at (or beyond) the margins of academic scholarship, research espousing many of the tenets of deep mapping can be found within disciplines such as historical geography [10], psychogeography [11], landscape archaeology [12] and the newer field of spatial humanities [13]. Modern technology is catalysing innovation, with digital geographical information systems (GIS) now enabling scholars to combine “bottom-up” data and “top-down” technology in new ways [14,15] to create spatially articulated, scalable representations of space which can encompass a range of natural, built, tangible and intangible heritage [16].

Exploring time depth is often an explicit aim of deep mapping, reflecting Heat-Moon who described PrairyErth as a “vertical journey” through time and referred often to archaeology when presenting his material and discussing his approaches [17]. Archaeology itself is a discipline which aims is to understand the past through the study of its physical remains and has long embraced spatial thinking: many archaeologists create maps which do include evidence found beneath the ground, created at scales ranging from the individual site to entire continents [18]. Deep mapping and archaeology might thus seem to have compatible aims that would encourage effective interdisciplinary working in pursuit of common goals.

However, perhaps surprisingly, this has not proved to be the case [19]. Despite frequent references to verticality, little of the deep mapping literature involves actual penetration below the physical surface of the explored terrains: Heat-Moon uses archaeological excavation as a metaphor rather than a practised technique, while recent deep maps such as Ethington and Toyosawa’s palimpsest of Los Angeles reveals a rich history, but no data from below the surface [20]. Within archaeology, antiquarian chorographic approaches to holistically representing places in time have fallen from favour, while more recent attempts at revival and reinvention of this tradition have been acknowledged as too protean to gain widespread academic traction [21]. GIS has been used by archaeologists since the 1980s to map and interrogate diverse datasets [22,23], but such studies, while displaying increasing technical virtuosity, can be overly absolutist and lose connection with humans, past and present [24,25]. Conversely, phenomenological studies within archaeology which since the 1990s have aimed to foreground the past lived human experience [26] have generated inferences which appear overly subjective and difficult to substantiate. Crowdsourced projects [27] represent a different approach again to involving contemporary publics in generating dynamic, expanding, continuously evolving place maps with time depth but such projects do not always prioritise reflexive scholarly analysis.

Such difficulties in creating meaningful links between the “soft” people-centred inputs and “hard” archaeologically-visible outputs of human societies, in the past and the present are familiar to those involved in public archaeology [28], but are not always easily resolved, especially if volunteers, researchers and communicators have incompatible or conflicting interests or priorities. This paper reviews recent research in which new archaeological excavations were carried out by residents of rural villages within the spaces they currently inhabit in order to make new discoveries about the past history of those places. The excavations were carried out in collaboration with university researchers who provided technical and methodological advice and on-site supervision as well as specialist evaluation of the results which were reported on jointly with community groups. These projects about communities, in communities, for communities, with communities and by communities generated data from more than 100 individual sites within four villages which could be aggregated to create new maps showing how spaces and places occupied by today’s communities were used in the past spanning thousands of years. This activity contributes to academic research as well as local knowledge, while also connecting volunteers with the pasts of the spaces they live in today and building social capital within communities for the future. The completion of a number of similar projects shows that their outcomes can be achieved widely to significant public benefit.

2. The Cambridge Community Heritage (CCH) Project

The four projects presented here formed part of the “Cambridge Community Heritage” (CCH) programme [29] which was funded in 2012–2013 under the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Connected Communities theme’s Research for Community Heritage (R4CH) call [30] jointly with the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) All Our Stories [31] fund. R4CH was intended to help community groups explore their heritage by giving them access to resources and expertise that exists within universities, and to create new opportunities for academics to work in a community context. Community groups chose for themselves the aspect of their heritage they wished to explore, and were the main drivers in deciding what approaches should be used to achieve this. In 2012 CCH issued an open call to community groups in eastern England (Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire) for expressions of interest in heritage-related community project of any type. Submitted ideas ranged extremely diversely across tangible and intangible heritage, proposed by groups representing communities of place, occupation, interest and identity including local historical societies, football clubs, church groups, traveller communities, schools, women’s groups and military regiments [32].

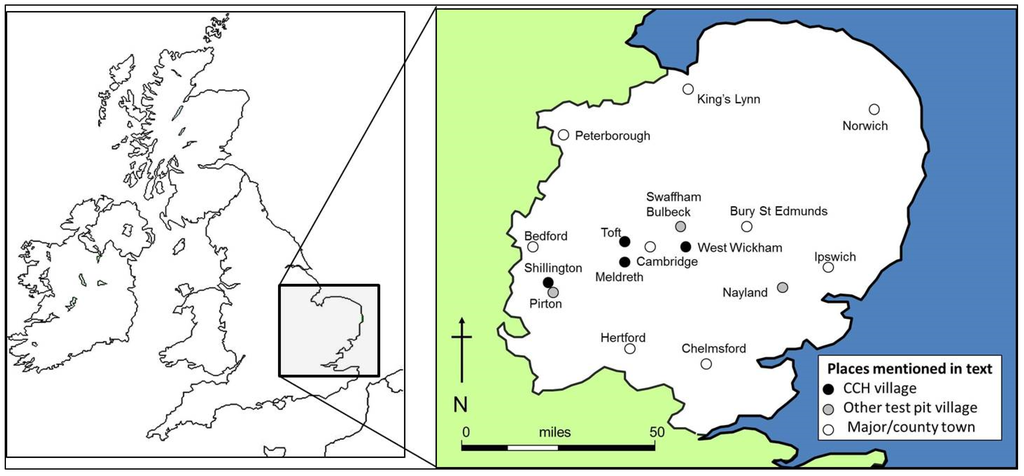

Out of a total of 23 community groups who were successful in securing funding within CCH, four were local history societies, based in the southern English villages of Meldreth, West Wickham, Toft and Shillington (Figure 1), who wished to find out more about their community’s history through excavating small archaeological “test pits”. The test pit approach, which involves the excavation of standard-sized metre-square in numerous different places across a site such as a historic settlement, can be used to recover buried archaeological data from largely built-up environments (such as today’s villages, hamlets and towns), within which open-area excavation of larger trenches is impossible [33]. Dating and mapping the distribution of finds recovered from the test pits, in particular worked flint and pottery sherds which are datable and found in large numbers, allows the changing spatial pattern of activity over time to be reconstructed [34,35]. Within the field of historic settlement studies, work in these currently occupied rural settlements (CORS) is an important priority as it allows the development of non-deserted settlements to be included in research which otherwise focusses primarily on deserted sites which are more easily accessible for archaeological excavation [36,37,38,39].

The CCH excavations in Meldreth, Shillington, Toft and West Wickham involved hundreds of local residents. Participation was open to everyone who lived in the communities, and to friends and family members resident elsewhere, and could include excavating and/or offering a site for excavation and/or helping with project planning and organisation. Within each excavation team, opportunities were present for both able-bodied and less able people of all ages (participants ranged in age from a few months to over eighty years) to take part in a wide range of activities including digging into the ground, searching through excavated spoil, finds washing and maintaining written records (the task of preparing refreshments was not a formal part of the process but drew in many other helpers). More than 100 separate excavations were completed, from which worked flint and pottery sherds were identified, dated and located to produce a series of maps showing which plots, streets and neighbourhoods within each of the four communities had produced finds from which historic periods. This information was contextualised and assessed in a technical report drafted for each settlement [40,41,42,43] summarised for publication in Medieval Settlement Research (e.g., [44]) and are contributing to ongoing academic research into the development of settlement, landscape and demography in southern England [33,45].

Figure 1.

Map of the British Isles showing places mentioned in the text.

2.1. Meldreth

The village of Meldreth is situated in south Cambridgeshire, England, 15 km southwest of Cambridge, centred on TL 37610 45812 (Figure 1). The parish lies in the valley of the River Cam or Rhee, which marks the northern parish boundary. The River Mel rises immediately south of the village at Melbourn Bury and runs through the village along the back of properties on High Street, before joining the Rhee north of the parish church. The parish of Meldreth lies on fairly flat and low-lying Cretaceous chalk bedrock between 15 m and 40 m above OD. The surrounding landscape is presently composed of gently rolling open arable farmland with drainage ditches and small streams and fragmented hedgerows forming field boundaries.

The existing village of Meldreth (Figure 2) is broadly linear in layout on an N-S orientation immediately west of the River Mel, forming an almost continuous polyfocal settlement more than 2 km long running between the neighbouring villages of Shepreth (to the north) and Melbourn (to the south). Analysis of the first edition of the 6-inch to 1 mile Ordnance Survey map shows that in the latter part of 19th century settlement at Meldreth was more dispersed than it is today and less continuous, divided into several discrete elements. The largest of these along High Street (Figure 2(Aa)) (immediately west of the River Mel), comprising a north-south-orientated nucleated planned linear row approximately 400 m long. This was separated by more than 200 m from three small clusters of settlement to its south (around the railway station (Figure 2(Ab)), its west (Chiswick End (Figure 2(Ac))) and its north (Manor Farm (Figure 2(Ad))). Approximately 200 m north-east of Manor Farm there was a smaller, less regular east-west orientated row running past the church (Figure 2(Ae)) and another even further to the north-east at North End (Figure 2(Af)), arranged around a small green. An isolated farm lay south of the village beyond the railway line (Figure 2(Ag)).

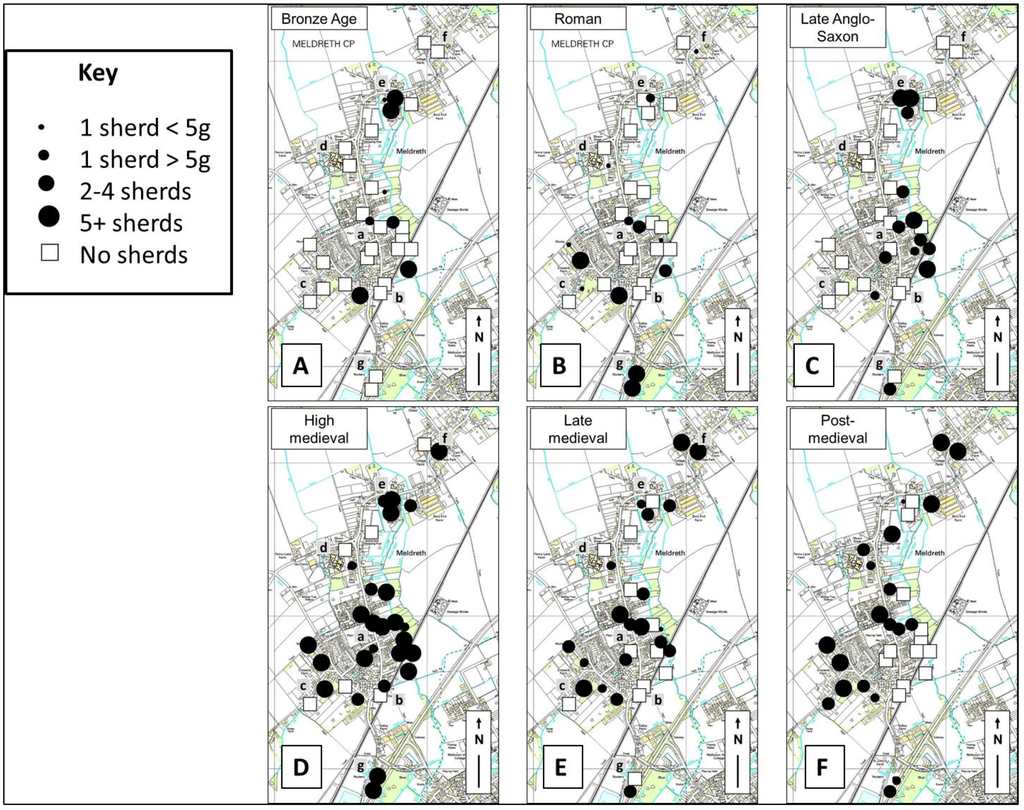

Figure 2.

Pottery from test pits excavated in Meldreth. (A) Bronze Age; (B) Roman; (C) Late Anglo-Saxon; (D) High medieval; (E) Late medieval; and (F) Post-medieval.

The 2013 test pit excavations were coordinated by Meldreth Local History Group [46] and involved more than 300 local residents in excavating 32 test pits ([47]; [48], pp. 120–21) as part of an extended suite of community-centred activities. These included a village hall lecture by the supervising university archaeologist delivered some months before the excavations, explaining their aims and speculating on the site-specific potential of the Meldreth excavations. The excavations themselves were each carried out over two days during one of three weekends spaced at intervals of approximately one month in summer 2013. Each of these weekends began with a short briefing explaining the excavation process (which had to be closely followed in order to ensure data validity) to participating volunteers (local residents along with families, friends and neighbours), who then dispersed to their gardens, or those of the friends or neighbours, to begin the excavation. Each site was visited frequently during the two days by a professional archaeologist from the university in order to ensure required procedures were being followed, provide advice and talk to volunteers about their finds and more generally about aspects of the excavations or their property which interested them. One resident filmed the talks and as much of the excavations as possible. At the end of the second, final day of each digging weekend, each team brought the finds from their test pit and the records they had kept to a central venue where tea and cake was provided and volunteers could view each other’s finds. A representative of each team then provided a short verbal summary of their excavation to the assembled group, chaired by the supervising archaeologist who also provided an assessment of the emerging “bigger picture” generated by the new finds in their final summary. In the months following the excavations, the results were formally analysed and contextualised and a technical report prepared by the university CCH team [41], an exhibition was held in the village hall in which finds were displayed along with a range of other local historical research carried out by local volunteers and the final results were presented to the local community in another talk held the following winter, which included new maps which included the excavated date and showed how the place had changed over time.

Analysis of the excavated finds (Figure 2) showed Bronze Age pottery (c. 1800–800 BC) to have been recovered from several different areas (Figure 2A) in the centre and north of the present village. Such finds are rare from test pits and this quantity from Meldreth suggests unusually intensive or persistent use by humans around three thousand years ago of the part of the landscape covered by the present village, especially around (“e”). This may have involved either settlement or mortuary activity, or possibly both. No evidence for the succeeding Iron Age period (800 BC–43 AD) was found from any of the pits, but this does not necessarily suggest the area was unused at this time, as pottery is relatively scant in settlements of this date. Pottery of Roman date (43–410 AD) (Figure 2B) was found, however, mostly in the centre and south of the present village (Figure 2(Ba–c and Bg)) in a pattern which suggested that settlement by then took the form of a dispersed scatter of small settlements such as farmsteads. Smaller amounts of pottery from test pits to the north suggest that area may then have been in less intensive use, possibly as arable fields. No pottery was found dating to the period between the 5th–9th centuries AD, but this is not unusual as settlements as this time tend to be small and produce little pottery therefore are easily missed by test pits, so this does not necessarily indicate the area was unused by humans at this time. In contrast, however, pottery of late Anglo-Saxon date (mid-9th to late 11th century AD) (Figure 2C) was found widely in two different areas (Figure 2(Ca,Ce)). A concentration from three pits in the north of the present village (Figure 2C,E) suggest the later-documented manorial site of Topcliffe originated at this date, while pottery from seven pits in the centre of the village (Figure 2C, west of “a”), all between the present High Street and the river, suggest the settlement at this time formed a linear row on one side of the street only, with smaller amounts of pottery from pits west of High Street suggesting this side of the street was used as arable fields. This pattern of settlement is significantly different to that in the Roman period, with much less Anglo-Saxon pottery found to the south and south-west of the present village (areas “b”, “c” and “g”) than in the Roman period, suggesting that use of this area may have changed from dispersed settlement to arable fields.

In the subsequent period, the amount of pottery of high medieval date (12th–14th century AD) (Figure 2D) indicates that in this period the settlement increased in size. Several pits west of the High Street (Figure 2(Da)) produced high medieval pottery, suggesting that new tofts were added in the 12th or 13th century along the west side of the High Street, probably laid out over former arable (explaining and dating the narrow property boundaries still observable on the 19th century maps). Other new additions to the settlement pattern at this time appear to have included smaller dispersed hamlets at Chiswick (west of the present village) (Figure 2(Dc)), North End (at the far north of the present village) (Figure 2(Df)) and near the present garden centre (Figure 2(Dg)), possibly the site of a separate farm. Pottery dating to the late medieval period (14th–16th centuries) (Figure 2E) was found in fewer pits and in lesser amounts, suggesting that settlement expansion ceased at this time, although it does not appear to contract in size significantly at his time, although the volume of late medieval pottery recovered from two historically documented medieval manorial sites (Topcliffe (Figure 2(De)) and Flambards (Figure 2D south-east of “a”) is dramatically less than previously. Overall, comparison with settlements elsewhere suggests that Meldreth was less severely by demographic decline than many settlements in the eastern region ([33], pp. 330–434; [45]). In the subsequent post-medieval period (16th–18th centuries) (Figure 2F), the test pit data suggest that Meldreth stagnated, with the south-eastern part of the settlement (Figure 2F, between “a” and “b”), which had produced large amounts of earlier pottery, particularly badly affected.

2.2. Shillington

Shillington is situated in south Bedfordshire near the border with Hertfordshire, 17 km southeast of Bedford, centred on TL 12562 34625 (Figure 1). The present settlement lies between 50–60 m above OD between the Pegsdon Hills a few kilometres to the south (part of the Chilterns), and the Greensand Ridge in Bedfordshire to the north. The parish lies among the headwaters of the Ouse catchment and its southern boundary follows the course of the Icknield Way over a spur of the Chiltern Hills at Pegsdon. A small brook flows in a northerly direction on the west side of a prominent hill and drains into the River Hitt and ultimately the Great Ouse. The surrounding land is today broadly composed of gently rolling open farmland with drainage ditches, water courses and fragmented hedgerows forming field boundaries.

Settlement in Shillingont parish today (Figure 3), which includes the formerly separate parish of Higham Gobion and the village of Pegsdon, is moderately dispersed, extending over more than 2 km along a succession of lanes which loop around to form two large polygons. A largely continuous stretch of housing extends between Woodmer End (Figure 3(Aa)) through Hillfoot End (Figure 3(Ab)) to Marquis Hill (Figure 3(Ec)) and east and south of the 14th century parish church of All Saints (located on the summit of the prominent chalk hill) (Figure 3(Ad)), affording it clear views of the surrounding landscape and rendering it visible from some distance. Settlement elsewhere in Shillington today is much more dispersed, arranged in several “Ends” including Apsely End (Figure 3(Ae)), Hanscombe End (Figure 3(Af)), Upton End (Figure 3(Ag)) and Bury End (Figure 3(Ah)). Discrete farms sited around the settlement include Hanscombe End Farm, Moorhen Farm, Northley Farm, Lordship Farm, Upton End Farm and Clawders Hill Farm.

The 19th century settlement, as depicted on the first edition Ordnance Survey 6-inch to one mile scale map, sprawled across an equally large area but contained fewer houses and retained a very much more dispersed character. The greatest concentration of housing was along Church Street (Figure 3A south-east of “d”) running east from the church), which was flanked by a nucleated double row of housing (although several plots north of this street were devoid of buildings), extending into the lane leading north towards Hillfoot End (Figure 3(Ab)). The church was then on the very edge of the settlement, with no houses then present to its north or west. To its south, housing was much more intermittent along the north side of High Road, with an intermittent succession of small properties forming an interrupted row extending north-east as far as Marquis Hill (Figure 3(Ac)) where the settlement petered out. Hillfoot End (Figure 3(Ab)) in the 19th century was an entirely separate hamlet comprising around a dozen or so cottages mostly south-east of a tiny triangular green where three lanes meet. Hanscombe End (Figure 3(Af)) was extremely dispersed with a handful of properties of varying size arranged along a winding lane. Woodmer End (Figure 3(Aa)) comprised perhaps 20 properties along a single lane arranged as an interrupted row at the south end and a more compact double row to the north, where it merged with the similar but smaller hamlet of Bury End (Figure 3(Ah)). Upton End (Figure 3(Ag)) comprised just 4–5 larger properties either side of the road towards Marquis Hill (Figure 3(Ac)), where there is very little settlement at all. Northley Farm and Shillington Bury Farm were isolated sites with no near neighbours.

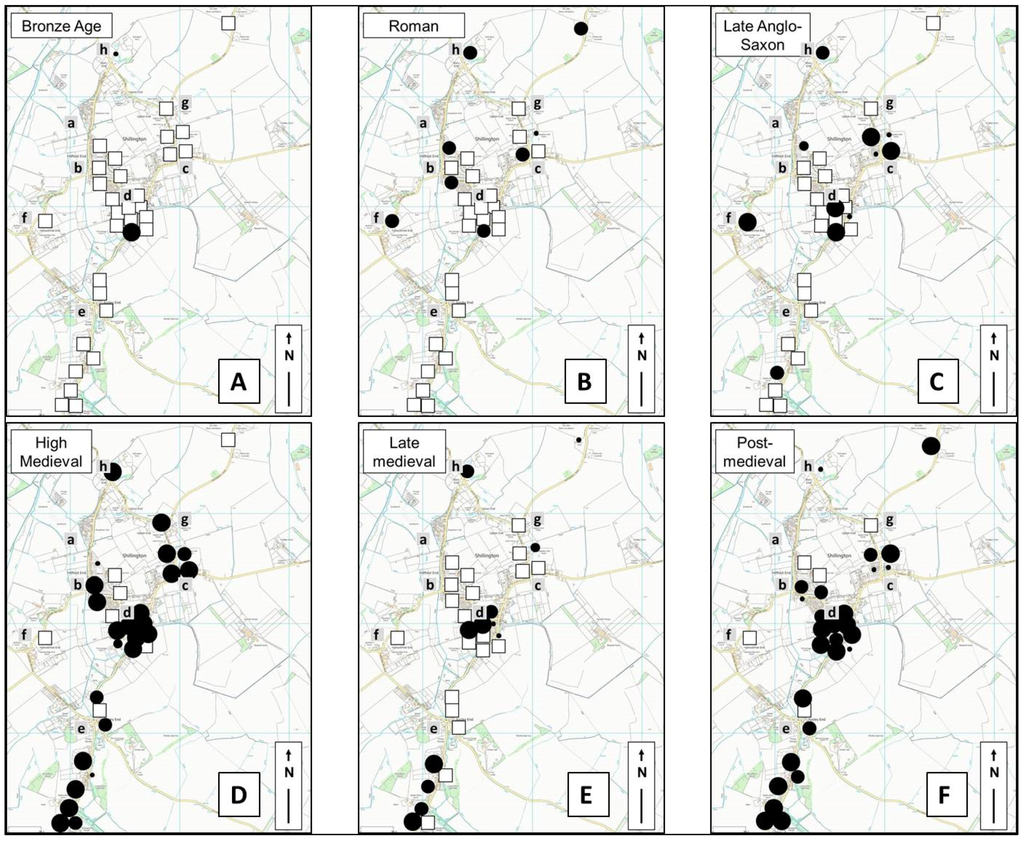

Figure 3.

Pottery from test pits excavated in Shillington. (A) Bronze Age; (B) Roman; (C) Late Anglo-Saxon; (D) High medieval; (E) Late medieval; and (F) Post-medieval.

The excavations were coordinated by Shillington Local History Society [49] and involved more than 300 residents of the village of Shillington and its local area in completing 23 test pits throughout the present village over a single two-day weekend in summer 2013. This began with refreshments and a short briefing after which volunteers dispersed to their chosen or allocated sites to begin the excavation. As at Meldreth, each site was visited frequently by supervising archaeologists and the second, final day ended with refreshments and a finds-viewing plenary in which each team reported on their finds. The finds were subsequently analysed and a report prepared [42] which mapped the finds and showed changes in the spatial disposition of human use of the landscape and settlement over time.

The 2013 excavations at Shillington produced Bronze Age pottery from two different locations in the north and centre of the area covered by the present parish (Figure 3(Ad,Ah)), suggesting a scattered pattern of land-use. Most notably, a test pit (Figure 3A, south of “d” ), near the small brook running west of the prominent chalk hill produced sufficient material to indicate intensive activity such as settlement or burial. Romano-British pottery came from seven different sites (Figure 3B), two of them (Figure 3(Bc) and north of “g”) away from the brookside area hinting at activity in this period extending beyond the lower lying stream-side zone. No evidence was found for any activity dating to the period between the 5th–9th centuries AD, but late Anglo-Saxon pottery (9th–11th century date) was found in two distinct concentrations (Figure 3(Cc,Cd)) sufficient to suggest the presence of small nucleated settlements with three other locations (Figure 3(Ce,Cf and Ch)) yielding sufficient pottery to hint at the possibility of outlying dispersed hamlets or farms present at this time. The high medieval period saw all these settlements grow, creating two apparently sizeable, probably nucleated, settlements south of the church and at Marquis Hill (Figure 3(Dd,Dc)) and a probably more dispersed attenuated row settlement up to 750 m long at Aspley End (Figure 3D, south of “e”). At the same time, habitative activity appears to commence at Hillfoot End and Upton End (Figure 3(Db,Dg)), indicating a pattern of mixed dispersed and nucleated settlement. This growth in settlement size and number was thrown into reverse in the late medieval period, with the mapped pottery data (Figure 3E) suggesting Shillington was particularly badly affected in this period of widespread demographic and settlement contraction compared to many settlements in the eastern region. Habitation at Marquis Hill, Upton End, Hillfoot End (Figure 3(Ec,Eg and Eb)) and the north of Aspley End (Figure 3E, north of “e”) appears to have ceased almost completely. In the post-medieval period, however, the test pit data indicates that Shillington gradually recovered (Figure 3F) , with the area around the church (Figure 3(Fd)) and most of the high medieval dispersed settlements reoccupied, although some of the medieval “ends” remained uninhabited for longer, especially in the north of the parish (Figure 3(Fb,Fh and Fg)).

2.3. Toft

The village of Toft lies in the county of Cambridgeshire, 9 km SWW of Cambridge and just 10 km north of Meldreth centred on TL 3596 5600 (Figure 1). Toft is one of several parishes lying on the northern bank of the Bourn Brook, which rises a few miles west of Toft and joins the River Cam just south of Grantchester. Toft parish lies on a south-facing slope between 25 m and 40 m OD on Cretaceous sedimentary Gault mudstone bedrock which is capped in the northern part of the parish by superficial Quaternary deposits of sands and gravels. The surrounding landscape is today broadly composed of gently rolling open arable farmland with drainage ditches and small streams and fragmented hedgerows forming field boundaries.

The excavations in 2013 focussed on the south of the present village of Toft, which comprises a nucleated settlement arranged either side of two main approximately north-south-orientated streets, High Street (Figure 4(Aa)) and School Lane (Figure 4(Ab)), and another row running perpendicular to these along Comberton Road running gently upslope (Figure 4(Ac)). The medieval parish church (Figure 4(Ad)) is now largely isolated and lies adjacent to fields south east of the present village.

Figure 4.

Pottery from test pits excavated in Toft. (A) Roman; (B) Early Anglo-Saxon; (C) Late Anglo-Saxon; (D) High medieval; (E) Late medieval; and (F) Post-medieval.

The 19th century Ordnance Survey maps shows the settlement then to have been much smaller and more dispersed than it is today, arranged loosely around a square grid of lanes between Comberton Road and the Bourn Brook. The most compact part of the settlement then was arranged as a linear row along the Comberton Road near its junction with Church Road (Figure 4(Ae)). Settlement along the northern end of the High Street (Figure 4A, north of “a”) was much more intermittent than today, constituting little more than a Methodist chapel and an inn. This is separated by some 150 m from a small north-west-south-east orientated single row of farms and cottages along a lane now called Brookside (then called Water Row) (Figure 4(Af)), which appears then to have constituted a separate hamlet. The dispersed character of the settlement pattern in this area is further emphasised by the presence of just a couple of cottages along School Lane, leaving the church even more isolated than it is today, with only the Rectory and a small terrace of three cottages for company.

The CCH test pit excavations at Toft were instigated by Toft Historical Society [50]. As in Meldreth, the project included a range of linked activities which in Toft included a village archaeological survey exploring earthwork remains in an area of deserted settlement, the excavations during which more than 600 residents of the village and the local area took part in excavating or visiting excavations in 16 different locations throughout the present village, the making of a film, preparation of a written technical report [43], a post-excavation winter talk on the results and a public exhibition when finds and the film were shown.

Analysis of the results showed that the area encompassed by the excavations was intermittently and lightly used by humans in the prehistoric period, with possible indications of a small settlement of Neolithic date beside the brook, beyond the south-eastern limits of the present village. No later prehistoric material was found, but the distribution of pottery of Roman date (Figure 4A) suggests a settlement of some substance to then have been present then in the same brook-side area (Figure 4(Ag)), with smaller numbers of sherds found in some of the pits to the north and north-west (Figure 4A near “a” and “b”) suggesting the present village may overlie an area in use for arable cultivation during the Roman period. The area around the church (Figure 4(Ad)) also produced small amounts of sherds of Roman date and may possibly indicate contemporary settlement nearby. One small sherd of pottery dating to the 5th to 9th century AD (Figure 4B, west of “g”) is a relatively unusual find which hints at the possibility that the Roman stream-side settlement continued into the post-Roman period. This same area (immediately north of the brook and about 200 m south-west of the church) also produced a considerable amount of late Anglo-Saxon pottery (Figure 4(Cg)), suggesting a small settlement, possibly a nucleated village, was by then present in this same location. Whether this represents continuation from the early Anglo-Saxon period or a new foundation cannot be ascertained from the known data—either scenario must currently be considered to be possible. Smaller amounts of pottery found test pits north-west of the brook-side area (Figure 4C, west of “f” and “a”) suggest that the arable fields of the Anglo-Saxon settlement lay in this direction, continuing the landscape use pattern of the Roman period.

In the high medieval period (Figure 4D) the settlement appears to have expanded markedly, with many more pits producing pottery of this date, notably in the area north-west of the Anglo-Saxon core (Figure 4(Df)) and south of the Bourn Brook (Figure 4(Dh)). The latter produced no material of any earlier date whatsoever and appears to be newly used for habitation at this time of known demographic growth in England. In the succeeding period (Figure 4E), by contrast, Toft experienced severe contraction, with the stream-side sites (Figure 4(Eg,Eh)) entirely abandoned in the late medieval period. When the settlement began to recover in the post medieval period (Figure 4F), apparently rather falteringly, its focus appears to have shifted north and west (Figure 4F, around “a”, “f” and possibly “c”), mirroring the extent of the present settlement, with the areas beside the stream settlement remaining permanently deserted. The demographic crisis of the 14th century can thus be seen to have terminated the history of settlement immediately north of the brook (“g”) spanning more than a millennium, as well that of the much more recently colonised area south of the brook (“h”).

2.4. West Wickham

West Wickham lies 19 km south-east of Cambridge near the county boundary between Cambridgeshire and Suffolk (Figure 1). The parish is mainly on tertiary chalk underlying an extensive drift cover of glacial clays with small areas of brickearths, with the present village situated on a gradually undulating ridge. There are no streams in the village, however a line of springs present along a gravel ridge running parallel and c. 100 m west of the High Street feed a number of ponds which are still extant to the rear of many of the houses. The present village lies near the centre of the parish and is mostly arranged along a linear High Street (Figure 5(Aa)) running north-east from the parish church of St. Mary (Figure 5(Ab)) for about 1.2 km. Streetly End (Figure 5(Ac)) is a separate hamlet of around a dozen houses located about 0.8 km south of West Wickham.

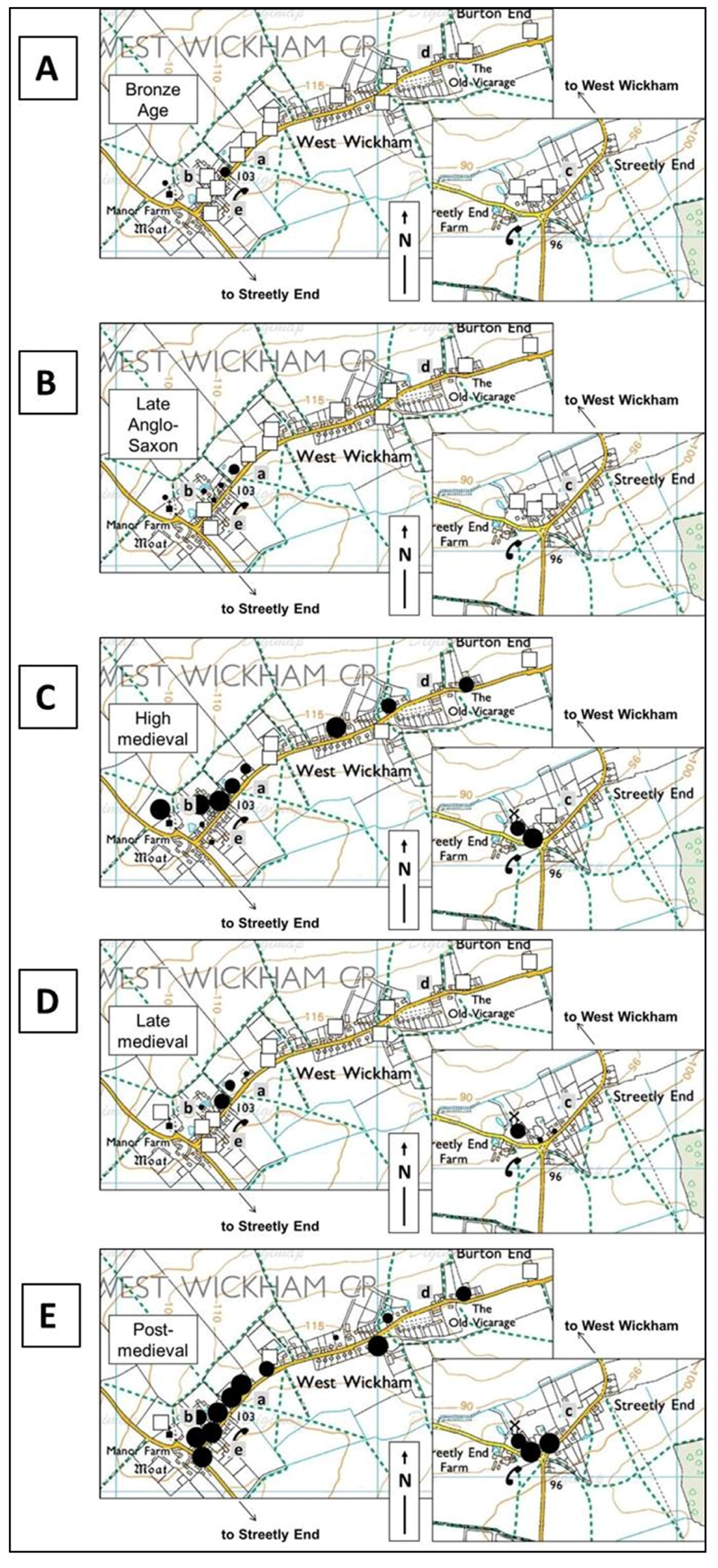

Figure 5.

Pottery from test pits excavated in West Wickham. (A) Bronze Age; (B) Late Anglo-Saxon; (C) High medieval; (D) Late medieval; and (E) Post-medieval.

The 19th century Ordnance Survey map shows West Wickham at this time to be formed of two discrete elements separated by more than 200 m. The compact linear settlement near the church favours the north (upslope) side of the High Street and is composed of mostly short plots, while Burton End (Figure 5(Ad)) has a more dispersed character, arranged as an interrupted row of fewer than ten residences most separated by fields. Streetly End appears much as it does today, although the pattern of plot boundaries suggests the High Street there has cut diagonally across an earlier more regular planned block of settlement.

The CCH excavations at West Wickham were organised by the West Wickham District Local History Group [51] and involved more than 70 local people in the excavation of 18 archaeological test pits over a single weekend. These followed the standard procedure of initial technical briefing accompanied by refreshments before the excavations, frequent visits by professional archaeologists during the weekend, a final get-together with refreshments, finds-viewings and reports from each team, followed by formal finds analysis and technical reporting [40] and a winter lecture in the village on the results.

The excavations suggested that the site of West Wickham was only lightly used by humans before the tenth century AD, although a slight concentration of finds of worked flint at the west end of West Wickham (Figure 5(Ae)) was present in contexts which suggest more intensive Bronze Age activity (c. 1800–800 BC), possibly settlement, in the in the area south-east of the (much later) church. Somewhat surprisingly, given finds elsewhere in the parish, no evidence of Roman date was found in any of the test pits within the present village. Material of early or middle Anglo-Saxon date was also absent, but pottery of late Anglo-Saxon date found near the parish church of St. Mary (Figure 5B either side of “b”), suggests that the present settlement at West Wickham was founded in this period. In the high medieval period (11th–14th century) an absence of pottery from the area immediately adjacent to the present High Street south of the church (Figure 5C between “b” and “e”) appears not to have been used for habitation, suggesting that there may have previously been an open green in this area, with houses sited along the northern edge of this. Both Streetly End (Figure 5(Cc)) and Burton End (Figure 5(Cd)) appear to come into existence at this date, and therefore appear later in date than West Wickham. These settlements appear small, but as few test pits were excavated, especially in Burton End, the findings to date might underestimate the level and extent of activity in this area. Overall, settlement in the parish of West Wickham in the high medieval period seems likely to have been somewhat dispersed in form, with a small village green surrounded by at least two small ends and probably several other isolated moated farms or homesteads (which were not excavated in 2013). This process of high medieval settlement expansion was abruptly arrested in the later medieval period (Figure 5D), which saw the settlement pattern particularly severely scaled back, with many outlying sites producing no pottery of later medieval date (mid-14th–mid-16th century) at all and only two pits producing more than a single sherd. Recovery at Burton End and Streetly End does not appear to have been established until after the end of the medieval period: all but three of the pits produced pottery of 16th–18th century date (Figure 5E). The pottery distribution suggests that when this robust recovery did take place, a nucleated row village developed at West Wickham near the church, where large amounts of pottery found close to the road suggests the green had been built over. At Burton End and Streetly End, the dispersed character of the settlement pattern established in the high medieval period appears to have been re-established.

3. Discussion: Deep Mapping and Wider Impacts

The four projects described above involved more than 1200 members of rural communities of place in a highly-engaged manner which involved significant contributions of time and effort by volunteers and which, as outlined above, succeeded in producing new spatial understanding of the long-term development of these four historic communities. The maps created using the data excavated from the archaeological test pits are, like all maps, partial in both senses of the word. They are selective in the types of evidence they encompass, and there are gaps in the datasets the maps do include, caused here by the incomplete nature of the archaeological record and the sampling process used which inevitably only recovers a tiny fraction of the total surviving buried data, which itself is only a fraction of that which was originally left behind by past users of the explored spaces. The practical limitations of the test pit approach when used within inhabited communities, where site selection is contingent on access which may be restricted by physical or social factors, means that some of the more fragmentary or isolated data, such as single sherds of prehistoric pottery in test pits sited far from any others, is not easily amenable to interpretation or explanation. However, each pit reveals unique new information about its individual location, and when the data from many pits are combined, analysed, and mapped, the patterns which emerge provide meaningful new perspectives on the changing use of space and place over time. The test pit excavation process thus contributes to the “depth” of mapping of settlement and landscapes at a range of scales.

Detailed discussion of how this is advancing knowledge and understanding of wider regional changes in settlement, landscape and demography [33] is beyond the scope of this paper. However, consideration will now be given to the social impact of test pit excavation projects within living communities, as the CCH projects were funded by HLF and AHRC with the aim of developing collaborations between university researchers and community groups which would enable group members and wider publics to benefit from exploring their chosen aspects of their chosen heritage. Accordingly, as well as the formal analysis, mapping and reporting of the archaeological finds, the impact of the projects was assessed by informal participant observation and formal written feedback taken from community group leaders at the end of the delivery phase in 2013 using paper forms and online surveys to elicit scalar metric assessments as well as free-text comments.

3.1. Enhancing Participant Knowledge and Engagement with Local Heritage

The projects had a significant positive impact on knowledge and engagement with local heritage within the host communities. All groups reported that the excavations had increased their own and volunteers’ knowledge of their heritage, these included knowledge amongst residents of the past of their own property (gained through taking part in the excavations) and of the new wider historical maps of the village (through attending plenary social events and following digital media outputs). Overall, the extent to which involvement increased a sense of connection with heritage was rated by groups (using a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest)) at an average of 9.33. Participant observation and free-text comments alike suggested that the impact was enhanced for excavation volunteers by the fact that the investigations (firstly) took place within volunteers’ own gardens and (subsequently) contributed to a wider body of new knowledge and understanding at local, regional and national level: this enhanced the sense that the outcomes at all levels were of direct relevance to volunteers. On almost every visit to each test pit, supervising archaeologists witnessed new discoveries being greeted with pleasure, interest, surprise and pride by participating community volunteers who were learning the extent, identity and significance of relics from the past recovered from beneath their lawns, playgrounds, verges and vegetable patches. Such sentiments were evident in individuals of all ages and backgrounds, and were enhanced by the intimate nature of much of the recovered evidence which strengthened the sense of connection between different people occupying the same spaces at different times. Fragments of personal items which would have been in daily use, such as tobacco pipe stems, cooking pot sherds, dolls’ limbs or flint tools, which had been made or chosen, owned or used and lost or discarded by former human users of very familiar spaces, acquired a value to their finders which considerably exceeded their conventional “research value”, let alone any realisable monetary value. “It was a lot of work, but hugely rewarding and we have been overwhelmed by the interest that our project has generated” (MLHG).

The projects had a significant positive impact on knowledge and engagement with local heritage within the host communities. All groups reported that the excavations had increased their own and volunteers’ knowledge of their heritage, these included knowledge amongst residents of the past of their own property (gained through taking part in the excavations) and of the new wider historical maps of the village (through attending plenary social events and following digital media outputs). Overall, the extent to which involvement increased a sense of connection with heritage was rated by groups (using a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest)) at an average of 9.33. Participant observation and free-text comments alike suggested that the impact was enhanced for excavation volunteers by the fact that the investigations (firstly) took place within volunteers’ own gardens and (subsequently) contributed to a wider body of new knowledge and understanding at local, regional and national level: this enhanced the sense that the outcomes at all levels were of direct relevance to volunteers. On almost every visit to each test pit, supervising archaeologists witnessed new discoveries being greeted with pleasure, interest, surprise and pride by participating community volunteers who were learning the extent, identity and significance of relics from the past recovered from beneath their lawns, playgrounds, verges and vegetable patches. Such sentiments were evident in individuals of all ages and backgrounds, and were enhanced by the intimate nature of much of the recovered evidence which strengthened the sense of connection between different people occupying the same spaces at different times. Fragments of personal items which would have been in daily use, such as tobacco pipe stems, cooking pot sherds, dolls’ limbs or flint tools, which had been made or chosen, owned or used and lost or discarded by former human users of very familiar spaces, acquired a value to their finders which considerably exceeded their conventional “research value”, let alone any realisable monetary value. “It was a lot of work, but hugely rewarding and we have been overwhelmed by the interest that our project has generated” (MLHG).

3.2. Confidence Building within Community Groups

Another significant impact of the projects was in building confidence within community groups for running community heritage projects, which will build capacity for the future. This was evident as early as the pre-submission development stage in 2012. During this period, three of the four groups expressed a desire at one point or another to withdraw from the process of devising project plans and preparing funding bids, with the main factor cited being anxiety over the complexities of the HLF application process and the possible adverse consequences of both failure and success in participating in the bid process. In each case, university support in the form of reassurance, advice, advocacy and/or problem-solving restored confidence amongst group leaders and led to all four bids not only being submitted, but in being successful in securing funding. 18 months later, when the projects had all been completed, the experience overall of running the project was rated very highly by group leaders, averaging 8875 out of 10. “Would never have had the knowledge or confidence to embark on a project like this without the University’s help and the involvement of the University was intrinsic to the success of our project…With the knowledge and skills that we have gained we now have the confidence to run similar projects in the future” (MLHG).

3.3. Extending Social Networks within Communities

The projects also developed social networks within and between groups and communities. Group working is an integral part of an activity such as test pit digging which usually requires at least two people to complete (and can easily accommodate a dozen or more friends, family, children and neighbours). Fostering opportunities for wider social exchanges before, during and after the excavations and planning for these to be lively social gatherings was actively encouraged by the CCH team, as prior experience had shown this to be a popular and hence effective way of encouraging people to attend briefings—not necessarily a top priority for people who might be tired, busy, or simply culturally disinclined to attend “talks”. Noting the addition of tea and cake to such events might seem trivial, but this encouraged volunteers to linger, relax and enjoy informally exchanging stories, information and ideas about their individual excavations, maximising the impact of the project as a nested activity which could be engaged with on a number of different levels and could lead on to other activities or interests in the future. Providing refreshments also provided opportunities for residents unwilling or unable to take part in the excavations to get involved in the project in different ways and drew in other community groups such as local Women’s Institutes. All CCH community group leaders felt their test pit projects had increased their knowledge of and connectivity with people locally who were interested in their heritage, and most felt this had increased their capacity to explore other projects in the future: “As a direct result of the project, new members have joined our Group and are now going on to research other aspects of the village’s history” (MLHG).

3.4. Instilling Skills

Another observable wider outcome of the CCH test pit projects was in the wide range of skills which were developed, including specific heritage-related skills as well as more broadly transferrable ones. Heritage-related skills included a range of skills in archaeological excavation and recording, creating photographic records, using archives and collections, creating archives, writing for publication and conducting local historical research. Broader transferrable skills included organising and running events, making films/audio recordings, developing webpages, using social media and working with press/media. A major driver of much of this skills development derived from a condition of HLF funding that groups should digitally disseminate the outcomes of their projects. This pushed some group members well beyond their comfort zones, but achieved very positive results in instilling skills as well as bringing the outcomes to wider audiences.

3.5. The Example of Meldreth

The Meldreth CCH project was selected as a case study by project evaluation consultants ICF GHK, commissioned by the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) to assess the effectiveness of All Our Stories programme [48]. ICF GHK identified 10 outcomes achieved by the Meldreth project for heritage, people and communities. The outcomes for heritage included the significance of the finds, the fact that these were formally reported on and the quality of the exhibition and documentation of the heritage project outcomes on the group’s website. Outcomes for people included acquisition of new skills and new heritage knowledge, which included primary and secondary school students as well as adults and younger families. Outcomes for the community highlighted the inclusive and engaged character of the project: “We were really struck by the kindness and enthusiasm of everyone. You managed the ‘inclusive’ event with flying colours”...“I have been incredibly impressed with the way the project has engaged so many and awakened so much curiosity about the village’s past”...“it pulled the whole village together and much was learnt about Meldreth in the process”. A district and county councillor noted the “community building” achieved by the test pit project.

The enduring legacy of the project in Meldreth was evident in subsequent developments. Encouraged by the success of their test pit project, Meldreth History Group quickly developed a range of ideas for new future activity, included “…Geophysical survey, fieldwalking and digging more test pits. We may also be interested in archaeological investigations on a larger scale if geophysics suggests that this is warranted. Other projects which may benefit from the involvement of a university student or researcher include research into the village’s manorial history and the use of dendrochronology/radio carbon dating to date old timbers in buildings”. These ambitious intentions have not remained mere wishful musings [47]: In 2014 members excavated more test pits involving residents of a retirement home and a special school, as well as carrying out a geophysical survey on a manorial site excavated during the CCH project, while in 2015 they are actively planning further funding bids for larger-scale community excavations on this site. In addition, members of the group are now providing another group in the nearby village of Stapleford with equipment, advice and on-site help in running their new test pit excavation project. The CCH project thus achieved specific and measurable culture change: Meldreth Local History Group, which was previously small and had no knowledge or experience in archaeological investigation, is now growing in size and has excavation firmly established as a popular core activity which is expanding the reach and impact of the group within and beyond their community to widespread benefit and which appears securely embedded for the future.

4. Beyond CCH

CCH was a large programme which involved more than 5000 people in 28 different projects ranging from excavation to oral history, all supported simultaneously by the same small university team on a tight budget over a single 12-month period: take-up of the programme was much larger than anticipated by the funders, and resources were not available to collect written feedback from individual participants. However, similar community test pit excavation projects elsewhere, carried out using identical approaches and supported by the same university team as the four CCH projects, show that the positive social impacts achieved in the CCH projects are widely achieved, and here feedback provides more detail about the nature of this impact. Between 2008 and 2014 written feedback data was collected from the excavators of more than 400 test pits in 12 different communities in eastern England [33]. With each respondent typically representing between four and fifteen volunteers, the results represent the impact on perhaps 2000–5000 individuals.

4.1. Impact on Local Knowledge, Engagement and Well-Being amongst Project Volunteers

Feedback confirms the observation from CCH that test pit excavation projects have strong and diverse positive impacts on volunteers. 77% of the volunteers felt that taking part in the test pit excavations had improved their knowledge of the archaeology and history of the place they lived in, and the fact that 75% had no prior experience of archaeological excavation shows that the activity reaches well beyond those who are already engaged. The impact of participation on levels of engagement with heritage was also explored in feedback, which showed that 84% felt the experience had led them to feel more engaged with their local heritage. Nearly the same number (83%) said that as a result they would take more interest in their local heritage in the future. Also looking to the future, 96% of respondents said they would recommend the experience to others. A follow-up question on the feedback forms invited those replying “yes” to this “recommend?” question to add free-text comments explaining why they would recommend the activity to others. Responses (taken here from a project in Nayland in Suffolk in 2012 [52] which typifies responses from other projects), illuminates the nature of the impact of this activity on participants as a number of recurring themes become apparent.

The first of these is the sheer enjoyment people had in the activity: “It’s such good fun” (PR); “I noticed too a lot of young, inexperienced people taking part who were clearly hugely enjoying themselves” (KH). This enjoyment is reflected in aggregate data: 97% of respondents rated the community test pit experience as “good” or “excellent”. The activity is also appreciated for its educational value: “It was a great educational experience, and enlightening to find out the history of Nayland. I developed good practical skills” (KP); “Good for all ages to learn about the history of an area (particularly their own)” (DD); “A great learning experience” (RH); “[I enjoyed] finding out about the history of the local area and about history/archaeology generally” (PR). The social aspect of the excavations is repeatedly specifically listed as a reason people would recommend the activity: “Brings strangers together working in teams” (AC); “I loved working with different people” (PR); “Getting to meet new and interesting people especially within the village” (ME); “…A good way to…meet new people when working as part of a team” (GE). This positive social impact is often described in ways which show its potential to generate enduring bonds between people and within the host communities: “Being part of a team creates and promotes social support and knowledge of each other” (LF); “Promotes a common interest and helps the village to bond” (LF); “It is very social, you begin to feel one of a team, one of a community” (DC). Importantly in this respect, the excavations also attract people from a range of backgrounds: “Good for bringing together people of all ages” (RH). This hints at the range of ways in which participation contributes to personal well-being, but building social links has the capacity also to strengthen and foster resilience within communities.

The opportunity the excavations provide for close contact with past is also frequently commented on: “It was a great way to spend the weekend outdoors, learning about history in a hands-on and up close and personal manner” (KP); “It is really good to touch and find things that no one will have seen for many years” (SW); “It is very satisfying to get some hands on experience” (SW); “Being actively involved is very different to just reading about it” (DC). A feeling that taking part changed volunteers’ perspectives on their community and its connection with its past was also often cited: “It’s a really mind-opening experience” (PR); “Helps to give you a sense of the context of your community” (RH); “Archaeology is about our history, it belongs to all of us” (DC); “Encourages you to think about the people who lived here before us and how they lived” (SM). The knowledge-enhancement aspect of the excavations were also appreciated as extending beyond individuals, being satisfying because they generating new knowledge for others: “It helps to improve knowledge of Nayland’s history and it was a very interesting experience as it encourages a more active interest in history and archaeology” (GE); “Fascinating insight into local history. Contributing to a national grid of archaeological information” (MH). Creating stronger perceptual links between people and their social and historical landscapes has evident synergies with deep mapping.

While the “discovery” and “social” impacts of participation can be seen as distinct achievements, they are appreciated by volunteers as entirely integrated, typified by comments such as: “I loved working with different people and helping to contribute to adding to the knowledge of this region” (PR); “It was great to be part of something that involved so many of the village and that feeds into a much bigger picture” (RH).

4.2. Impact of Participation on Volunteer Skills

A framework has been developed [53] for assessing the ways in which taking part in test pit excavations instils transferrable skills in teenagers participating in the aspiration-raising Higher Education Field Academy (HEFA) programme [54] where they carry out exactly the same archaeological procedures as the CCH project. A review of the assessment data [55] showed that in 2012–2014, 77% of nearly 1000 HEFA students felt participation had developed their verbal communication skills (with assessors grading 74% of students at A*–B in this skill); 87% felt it had developed structured working skills (76% graded A*–B by assessors); 79% developed creative thinking skills (66% graded A*–B); 78% developed reflective learning skills (72% A*–B); 86% developed perseverance skills (88% A*–B) and 87% developed team working skills (82% A*–B).

Participation in test pit excavation projects has also been shown to help people who face particular challenges. In 2012, collaboration with Cambridgeshire charity Red2Green [56] involved adults affected by autism in tailored test pit projects intended to increase participants’ interest in archaeology and local history and to develop their teamwork and communication skills [57]. In 2012, 15 volunteers who belonged to Red2Green’s “Aspirations” life-skills building group took part in test pit excavations in Swaffham Bulbeck for up to three days. Most excavated alongside pupils attending the local primary and secondary schools, and subsequently worked with an artist to create display items drawing on their experience including patchwork quilts and decorated ceramic tiles. Feedback on the excavation element of the project ([57], Appendix) showed that 73% of the Red2Green participants rated the experience very highly, with 85% saying they would like to get involved with practical archaeology projects again in the future. 69% said they would like more chances to discuss archaeology or local history with others, supporting the observation by Red2Green staff that the learners had demonstrated a “noticeable increase of confidence when talking to new people”. One parent commented enthusiastically that her son, who did not usually talk much about his day “would not stop talking about the project!” highlighting not only his enjoyment, but also the impact the project had on his ability and desire to vocalise his experiences. These are notable outcomes given the difficulties these Red2Green clients normally encounter when communicating verbally with others.

4.3. Enduring Legacies

The long-term outcomes of sustained involvement with community test pit excavation projects can be seen at Pirton in north Hertfordshire, ([33], pp. 325–26) (which lies immediately adjacent to the CCH 2013 village of Shillington). Test pit excavation at Pirton started in 2007 as a school HEFA project with a small group of teenagers completing just five pits ([58], pp. 52–53). It might have stopped there, but when local residents heard of the results from other HEFA communities where more than 30 pits had by then been excavated, they were inspired to take up the challenge. Over the course of a series of biannual weekend community excavations, scores of local residents completed more pits and cumulatively gained the skills and knowledge to be able to work effectively without professional archaeological supervision, although contact with the university was maintained throughout. Excavations continued for eight years, and by 2015 more than 100 pits had been completed in Pirton, more than has yet been achieved in any currently occupied rural settlement. In 2015, aware of the academic context and recognising the wider importance of their results, the Pirton community decided to move onto the next stage, as announced in coordinator Gil Burleigh’s Facebook post on 17 May 2015: “Sad and exhilarating weekend! Dug 115th test pit in Pirton, found western extent of 13th century manorial building first identified in 2013, plus 15th–18th century barn, at Bury End. That’s the end of the project though—time to write it all up, everything since 2007. Thanks to everyone who has volunteered and contributed over past eight years…” [59]. There is clearly ample potential here for creating a deep map of Pirton which encompasses the intangible contributions of time, energy, local knowledge and ideas made by scores of local volunteers as well as the tangible artefactual evidence spanning thousands of years.

Indeed, the potential of this stage of community test pit excavation projects can be seen in the results from Great Bowden, whose local historical society [60] collects village photographs and other memorabilia and publishes local historical studies [61]. In 2013–2014 the society secured funding for a community test pit excavation project and completed 30 pits across this Leicestershire village. The results were analysed by the same University of Cambridge team as the CCH projects in collaboration with the Great Bowden Heritage and Archaeology Group, whose members contributed accounts of the local and oral history of each of the excavated sites which were included in the formal excavation report [62]. As a result, site-by-site analyses and time-deep maps consequently enmesh local history, archaeology and personal memory.

5. Conclusions

A deep map can be defined as “a finely detailed, multimedia depiction of a place and the people, animals, and objects that exist within it and are thus inseparable from the contours and rhythms of everyday life…simultaneously a platform, a process and a product…a way to engage evidence within its spatiotemporal context and trace pathways of discovery…framed as a conversation and not a statement” ([13], pp. 3–4)—an answer to the challenge of holistically comprehending space, time, people and place. Archaeology is often overlooked in the scholarly literature on deep mapping, but has the capacity to contribute significantly to the creation of deep maps, not only by adding greater time-depth but also, though the palpable, grounded, on-site physicality of its evidence base, strengthening the connections between people, space, time and map.

The data presented here, from CCH projects and other similar programmes, show that archaeological test pit excavation within currently occupied rural settlements—today’s villages, hamlets, farms and small towns—generates deep maps which elicit unique new spatiotemporal perspectives. They can show how different areas within today’s inhabited places were used at different times in the past, revealing the often turbulent ebb and flow of human endeavour concealed underneath the for-now quiescent lawns of 21st century rural villages, showing observers which spots have been continuously inhabited for a millennium or more, which are new expansions within the last couple of centuries, and which have for generations oscillated between habitation, abandonment and re-occupation. The data also glimpse more personal histories—the ravaging of Shillington by the demographic catastrophes of the 14th century; the aspirational consumption of the manorial lords of Meldreth, evident in the exotic mirror found at Flambards manor; and the simpler everyday pleasures of rural life evidenced by numerous finds of fragments of clay tobacco pipes and children’s toys. These data create multi-media maps whose depth is both temporal and psychological, derived from the living landscape, imbued with the physicality of the tangible nature of the recovered evidence and dynamically capable of growing and changing as new data is added or ideas change.

When the excavations are carried out by residents of those communities, they acquire depth in another dimension as people search, for themselves, within their own familiar places, for evidence from the seemingly remote past. The process of data recovery involves participants in performance of the processes of excavation which are both structured and improvised: each team will have carried out the same actions, but in their own way in response to the unique qualities of their site, their team. Enacting this performance creates bonds between participants, whether they have excavated on the same site or different ones. Furthermore, the palpable physicality of the recovered archaeological evidence creates an umbilical link between present inhabitants and their predecessors that can be appreciated both intellectually and empathetically, and which can engage, meaningfully, people with very different levels of prior knowledge and interest1.

Community test pit excavation responds to the notion of deep mapping, perhaps even epitomises it, as it involves people in exploring evidence which is neither finite nor constrained, simply recovering whatever is present beneath a single square metre of ground and weaving the resulting material into a narrative about a place. It combines subjective, experiential and performative inputs with objective, standardised frameworks of method and analysis to create multi-media outputs which are academic, personal and capable of dynamic evolution in the future.

Reference to the future raises another important point. Given the diverse academic and social benefits of this approach to deep mapping, it is clear that extending this activity is desirable. To do this, it is crucial that the knowledge and understanding which these deep maps represent should not be restricted, within either academia or local communities, not least because dissemination will help fulfil potential. Dissemination is not, however, automatically consequential on the primary activity and needs to be specifically planned for. All the CCH projects presented here returned the outcomes to host communities in in public events where finds could be examined, new maps presented and the results discussed (dissemination was an explicit requirement of the HLF, who prioritise the social impact of funded projects). Some groups created permanent physical displays, and all added content to websites. These disseminations, especially the events, were popular and highly impactful locally, but nonetheless, their impact will dissipate over time. Public broadcast disseminated the outputs of community test projects similar to CCH in Kibworth (Leicestershire) in Story of England in 2010 [63]; and in six different communities in eastern England in On Landguard Point (an Arts Council-funded commissioned for the London 2012 Olympic Games’ Cultural Olympiad [64]). Such dissemination massively increased the reach of these projects: most of the CCH community partners had been inspired by Story of England. Realistically, however, such broadcast opportunities are rarely available, and if deep mapping is to be advanced and embedded within wider publics in a truly sustainable way, a framework for continued exploration is needed which stimulates mass engagement at a local level. This seems ambitious, perhaps, but experience of community test pit excavation projects suggests that it is achievable, and routes to such achievement, through publicly engaged research involving community groups and school curricula, are currently being explored by this author.

Viewed in the context of deep mapping, it is salient that community test pit excavation projects create performative and perceptual links between present and past communities, as people are connected with both the process and product of following horizontal and vertical pathways of discovery about their own locales, while simultaneously generating new evidence which can be mapped within its spatio-temporal context and aggregated to advance wider understanding of changing places in time. That such projects simultaneously nurture personal well-being and build social capital for the future within those same communities demonstrates the wider value of such participatory community-engaged research.

Acknowledgments

The CCH project was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Heritage Lottery Fund, and their support is gratefully acknowledged. The Principal Investigator and Archaeological Director for CCH (and for HEFA, Story of England and On Landguard Point) was Carenza Lewis. Alexander Pryor, Britt Baillie, Catherine Ranson, Matthew Collins and Sue Oosthuizen provided archaeological advice and supervision to excavating volunteers and coordinators within the community groups and Clem Cooper provided essential administrative support to the PI. Paul Blinkhorn, Lawrence Billington and Vida Rajcovaca respectively reported on the pottery, worked flint and animal bone from the excavations. Volunteers locally who took part in the excavations are far too numerous to name here individually, but special acknowledgement is due to Kath Betts and Joan Gane (Meldreth Local History Group): Janet Morris and Andrew Morris (West Wickham Local History Group); Derek Turner (Shillington Local History Society); Mike McCarthy, Ann Mitchell and Colen Lumley (Toft Historical Society), who suggested and ran the projects within their local communities, without whom none of the CCH test pit projects presented here would have happened. Gil Burleigh, Helen Hofton, Andora Carver and Rosemary Culkin were responsible for coordinating test pit excavation projects at Pirton, Nayland and Great Bowden, also discussed in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References and Notes

- William Least Heat-Moon. PrairyErth: A Deep Map. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J. Wydeven. “Review of PrairyErth: A Deep Map.” Great Plains Quarterly 1 (1993): 133–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mike Pearson. In Comes I. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jack Kerouac. On the Road. New York: Viking, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Bill Bryson. A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail. London: Random House, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Wood. The Story of England. London: Penguin Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ida McMaster, and Kathleen Evans. Mount Bures: Its Lands and Its People. Bures: privately printed, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley Cooper. The Long Furrow: 2000 Years of Rural History along the Suffolk-Essex Border. Bulmer: Bulmer Local History Group, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Hallman. “Thundersley and Daws Heath: A History.” 2015. Available online: http://www.hadleighhistory.org.uk/page/thundersley_and_daws_heath_a_history (accessed on 5 July 2015).

- William George Hoskins. The Making of the English Landscape. Leicester: Penguin Books, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Bob Trubshaw. “Book Review—Psychogeography.” Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture 2 (2009): 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendy Ashmore, and A. Bernard Knapp, eds. Archaeologies of Landscape: Contemporary Perspectives. Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

- David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris. Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Anne Kelly Knowles. Past Time, Past Place: GIS for Historians. New York: ESRI Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley David, and Mark Gillings. Spatial Technology and Archaeology. London: Taylor and Francis, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anne Kelly Knowles, and Amy Hillier. Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship. New York: ESRI Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cinzia Schiavini. “Writing the Land: Horizontality, Verticality and Deep Travel in William Least Heat-Moon’s PrairyErth.” Rivista di Studi Americani 15–16 (2004–2005): 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno David, and Julian Thomas. Handbook of Landscape Archaeology. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- David Petts. “Archaeology and Psychogeography.” Available online: http://outlandish-knight.blogspot.co.uk/2011/12/archaeology-and-psychogeography.html (accessed on 7 September 2015).

- Philip Ethington, and Nobuko Toyosawa. “Inscribing the Past: Depth as Narrative in Historical Spacetime.” In Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. Edited by David J. Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015, pp. 72–101. [Google Scholar]

- Darrell J. Rohl. “Chorography: History, Theory and Potential for Archaeological Research.” In TRAC 2011: Proceedings of the Twenty-First Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2012, pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Aldenderfer, and Herbert D.G. Maschner, eds. Anthropology, Space and Geographic Information Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- James Conolly, and Mark Lake. Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Denis Byrne. “Counter-mapping in the Archaeological Landscape.” In Handbook of Landscape Archaeology. Edited by Brund David and Julian Thomas. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2008, pp. 609–16. [Google Scholar]

- John J. Bradley. “When a Stone Tool is a Dingo: Country and Relatedness in Australian Aboriginal Notions of Landscape.” In Handbook of Landscape Archaeology. Edited by Brund David and Julian Thomas. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2008, pp. 633–37. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher Y. Tilley. A Phenomenology of Landscape. Oxford: Berg, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Know Your Bristol. “Exploring local heritage and culture through the eyes of Bristol communities.” 2015. Available online: http://knowyourbristol.org/about-us/ (accessed on 17 July 2015).

- Robin Skeates, Carol McDavid, and John Carman, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Public Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- “Cambridge Community Heritage.” Available online: http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/communities/cch (accessed on 30 June 2015).

- “Arts and Humanities Research Council Connected Communities.” Available online: http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/research/fundedthemesandprogrammes/crosscouncilprogrammes/connectedcommunities/ (accessed on 7 September 2015).

- Heritage Lottery Fund. “All Our Stories: Heritage Lottery Fund launches new funding programme.” 2012. Available online: https://www.hlf.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/all-our-stories-heritage-lottery-fund-launches-new-funding (accessed on 5 July 2015).

- Carenza Lewis. Cambridge Community Heritage. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2013, submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Carenza Lewis. “The Power of Pits: Archaeology, outreach and research in living landscapes.” In Living in the Landscape. Edited by Katherine Boyle, Ryan J. Rabett and Chris O. Hunt. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2014, pp. 321–38. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher M. Gerrard, and Michael Antony Aston. The Shapwick Project, Somerset: A Rural Landscape Explored. Leeds: Society for Medieval Archaeology, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Jones, and Mark Page. Medieval Villages, Beginning and Ends. Macclesfield: Windgather Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maurice Warwick Beresford, and John Hurst. The Lost Villages of England. London: Alan Sutton, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Della Hooke, ed. Deserted Medieval Villages: A Review of Current Work. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology, 1985.

- Christopher Dyer, and Richard Jones, eds. Deserted Villages Revisited. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2010.

- Neil Christie, and Paul Stamper, eds. Medieval Rural Settlement. Britain and Ireland AD 800–1600. Oxford: Windgather and Oxbow Books, 2012.

- Carenza Lewis, and Britt Baillie. “Archaeological Test Pit Excavations at West Wickham, Cambridgeshire.” 2013. Available online: http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/reports/cambridgeshire/west-wickham/2013 (accessed on 7 September 2015).

- Carenza Lewis, and Alex Pryor. “Archaeological Test Pit Excavations at Meldreth, Cambridgeshire.” 2013. Available online: http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/reports/cambridgeshire/meldreth/2013 (accessed on 7 September 2015).

- Carenza Lewis, and Alex Pryor. “Archaeological Test Pit Excavations at Shillington, Bedfordshire.” 2013. Available online: http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/reports/bedfordshire/shillington/2013 (accessed on 7 September 2015).

- Carenza Lewis, and Alex Pryor. “Archaeological Test Pit Excavations at Toft, Cambridgeshire.” 2013. Available online: http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/reports/cambridgeshire/toft/2013 2013 (accessed on 7 September 2015).

- Carenza Lewis. “Test pit excavation within occupied settlements in East Anglia in 2013.” Medieval Settlement Research 29 (2013): 78–89. [Google Scholar]

- Carenza Lewis. “Disaster Recovery—New archaeological evidence for the long-term impact of the ‘calamitous’ 14th century.” Antiquity, 2015, forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Kathryn Betts. “Meldreth Local History Group.” 2007. Available online: http://www.meldrethhistory.org.uk/page_id__23.aspx (accessed on 5 July 2015).

- Meldreth History. “2013 Test Pit Project.” 2013. Available online: http://www.meldrethhistory.org.uk/category_id__103.aspx (accessed on 5 July 2015).