Abstract

This article proposes that the experiences of screen tourists in Oxford help to create a theoretical “deep map” of the city which explores place through narrative. Building on the travel writing of William Least Heat-Moon and other recent work in the spatial humanities, two case studies of major screen tourism drivers are considered and analyzed. The British television drama Inspector Morse (1987–2000) explores the ambiguity of Oxford intellectualism through its central character. Morse’s love of high culture, especially music, provides suggestive additional layers for multimedia mapping, which are realized online through user-adapted Google Maps and geolocated images posted on the Flickr service. Harry Potter fans may not be “pure” or independent screen tourists, but they provide a wealth of data on their interactions with filming locations via social media such as Instagram. This data provides emotional as well as factual evidence, and is accumulating into an ever richer and deeper digital map of human experience.

Keywords:

deep mapping; screen tourism; Oxford; Harry Potter; Inspector Morse; intellectualism; social media 1. Introduction

As I sit writing this article in the hallowed halls of the Bodleian Library’s Radcliffe Camera reading room in the heart of Oxford, my immediate surroundings are hushed and quiet, filled with ancient books and students blinking in the light of laptop screens. By contrast, outside the window is the hustle and bustle of a major international tourist attraction. Couples, families and organized groups wander gazing at the landmark within which I am sitting, most of them making their own images of the building with cameras or mobile phones. Occasionally a cluster of sun hats pops up apparently atop one of the high walls which surround Radcliffe Square and partition Oxford’s famous quads. The hats belong to tourists being guided around Exeter College, which (a quick Google search reveals) is the alma mater of pre-Raphaelite artist William Morris, but also the home of the perfect green lawns upon which bucolic television detective Inspector Morse (John Thaw) collapsed of a fatal heart attack. More recently, director Peter Jackson visited the college to discuss his blockbuster adaptations of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), written (according to Google Maps) 27 minutes’ walk away in North Oxford. Just over the road larger groups of school children and foreign language students queue to walk up the beautiful vaulted staircase of The Divinity School in order to take photos of themselves apparently in Hogwarts. These photos will be posted immediately (and often publicly) on image sharing services such as Flickr or Instagram along with discussions about how much visiting Oxford makes you feel like you’re in a Harry Potter film.

It is therefore possible to imagine Radcliffe Square as the symbolic centre of an imaginary map of “Oxford” which is made and remade countless times by its many visitors. Each of these visitors starts the day with their own expectations and itineraries, primed by a combination of physical guide books, prior cultural experiences—such as watching Inspector Morse on television—and online recommendations from sites such as TripAdvisor. At the end of the day they will have added a further layer of lived experience to this imaginary map, yet often even these “real” memories will be heavily mediated by photographs, videos and Facebook posts. The instant digital mediation of tourist activity lends further grist to the mill of those who believe that such experiences are essentially meaningless, brief encounters with a complex city which only locals really understand. Many of these locals (particularly the academics) despair about the resulting commodification of Oxford’s history and identity into gift shops and over-priced museum cafes. But to write off and disparage tourism is to ignore so much of the vitality of contemporary Oxford. After all, what makes my own insider experience of the Radcliffe Camera any more valuable than that of the tourists who are kept safely outside? Aren’t Oxford’s students and scholars actually just types of tourists themselves, drawn to study or work in the city by an ideal of Oxford-ness and its historical associations with knowledge and power? As Leshu Torchin describes, the critical discussion of tourism is dominated by a binary opposition between authenticity and artificiality, rendering tourists as either frustrated seekers of the real or anchorless revellers in the unreal [1]. In this article, I will follow Torchin by granting tourists greater agency to negotiate between these two poles. This agency is demonstrated through an active remapping of space, positing tourists as co-creators of a theoretical “deep map” of the city, one which enables the navigation of “Oxford” in both the real and the imaginary senses.

As the concept of the “deep map” is relatively unknown outside academic discourse, and not yet fully explored even in a critical sense, it is well worth beginning with a discussion of the term and its origins. Most obviously, the modification of the noun “map” with the adjective “deep” highlights the thinness and two-dimensionality of traditional cartography. All maps are symbolic and selective, and when we consider that they have frequently been created by those with social and political power, they can be read as a means of ideological control over the citizens of a place. Hence politically-motivated groups such as the French Situationists of the 1950s and 1960s literally deconstructed (as in chopped to bits and remade) street maps of Paris according to their personal emotional experience of the city. The Situationists called this process “psychogeography” and were particularly interested in the relationship between the environment and human behavior [2]. The term “deep map” probably originated some years later in the distinctive travel writing of William Least Heat-Moon: it is the subtitle of his detailed and multi-layered account of a small patch of the Kansas grasslands PrairyErth [3]. Whilst Heat-Moon chooses to avoid a precise definition of his methodology, the literary critic Susan Naramore Maher has unpicked his mysterious style in the following terms:

From a literary and more broadly a humanities perspective then, the deep map is essentially a means of reconciling place and narrative. This is not simply a matter of geolocating literary or cinematic texts, although much interesting work is being done in this area (see for example Julia Hallam and Les Roberts’ Locating the Moving Image [5]). In Heat-Moon’s work, deep mapping requires a “plethora” of “stories” and “tales”, and results in a destabilization of concrete space: place becomes “indeterminate” and “elusive”.What distinguishes the deep map form from other place-based essays is its insistence on capturing a plethora of interconnected stories from a particular location, a distinctive place, and framing the landscape within this indeterminate complexity. Deep maps present many kinds of tales in an effort to capture the quintessence of place, but the place itself remains elusive and incompletely limned.([4], pp. 10–11)

Such a description of place might equally be applied to popular publications such as Tony Reeves’ Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations [6], where real places are fragmented into multiple pieces of filmic narrative and precise filming locations. Whilst Reeves’ expansive global project is too broad to qualify as deep mapping, there are plenty of more detailed publications which feel closer to Heat-Moon’s obsessively localized methodology. Pop into any Oxford gift shop and you will almost certainly find at least one example, such as Bill Leonard’s The Oxford of Inspector Morse and Lewis [7], a slim but dense volume designed to accompany walking tours of the city and filled (like PrairyErth) with simplehand-drawn maps. Here the plethora of stories are mostly fictional—summaries of key episodes which draw attention to place over and above plot—but there are also historical accounts of the city and its landmarks. Such guides and the omnipresent “movie maps” produced by tourist boards are fascinating collisions between narrative and place, and yet they have received little attention from the growing critical literature on the phenomenon of screen tourism. Les Roberts work on the movie maps of the city of Liverpool is a notable exception in this regard.

Roberts argues that, for a city such as Liverpool which is often used as a cheaper cinematic “stand-in” for other cities—principally London—the benefits of screen tourism can be obscure at best. In fact, active “destination marketing” using screen products may only serve to exacerbate historical inequalities between the South and North of England. My own focus upon Oxford presents a very different dynamic in terms of class and English regional identity, and although Oxford also “stands-in” for Hogwarts, the fantastical blending of real and imaginary locations presents no obvious barrier to pleasure for the Harry Potter tourist visiting the city. Therefore unlike Roberts’ example of Liverpool where movie maps arguably represent a “disembedding of place, identity and cultural memory” ([8], p. 201), I want to propose that screen tourists in Oxford use movie maps, guides and online cartography to enable a seductive fantasy of embodiment, a means to temporarily inhabit a fictional hero by entering their world. This fantasy space is not quite the real Oxford, and it requires different tools to navigate. These tools can be thought of as a “deep map” in the sense that they are a space where narrative and place are indistinguishable.

A different branch of academic research has recently taken up the literary metaphor of deep mapping and used it as a means of building bridges between the humanities and the social and physical sciences. This is especially driven by the development of technology known as Geographical Information Systems (GIS), which offer sophisticated means of mapping data. In an effort to encourage the use of GIS outside of the social sciences, David Bodenhamer, Trevor Harris and John Corrigan have called for humanities scholars to “design and frame narratives about individual and collective human experience that are spatially contextualized”, enabling the construction of “increasingly more complex maps…of the personalities, emotions, values and poetics, the visible and the invisible aspects of a place” ([9], pp. 172–74). Whilst the construction of a deep map of Oxford using GIS is beyond the scope of this article, I will incorporate and analyze geospatial data which is already publicly available, in particular photographs taken by tourists in Oxford and posted online. Such data has the crucial deep mapping characteristic of user-interactivity: the map as modified and constructed by its users. This is compatible with Maher’s notion of “interconnected stories”, and although Heat-Moon is credited as the sole author of PrairyErth, the book is constructed from a complex web of quotations and tales from local people, giving the sense that it grows organically out of the land itself. Whilst these geotagged images and their commentary emerge digitally rather than organically, there is no reason why they should not be just as evocative of lived experience. The digital mediascape is certainly a recent phenomenon compared to the much broader historical scope of Heat-Moon’s book, but when considered as a conduit for historical information, social media can function as an enabler—or even an automatic generator—of deep maps, as I hope to demonstrate below.

2. Inspector Morse: “Sophocles did it!”

According to novelist Philip Pullman, Oxford is particularly suited to an imaginative engagement with place due to its long history of producing fantastical narratives. From Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) to C. S. Lewis’ Narnia tales, to the urtext of fantasy literature The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955), Pullman’s Oxford is a city where “the real and the unreal jostle in the streets” ([10], p. i). We don’t need to go as far as this playfully supernatural conceit to acknowledge that central Oxford with its cobblestone streets, narrow lanes and omnipresent gargoyles is the kind of landscape that inspired much of the medievalist iconography of fantasy literature including most recently J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter novels.

Of course there are more prosaic ways to account for Oxford’s connection with fantasy literature. In order to become a fantasy novelist in the 19th and early 20th centuries you needed access to a store of ancient knowledge about mythology and legend, as well as an occupation providing sufficient time to write. So it is certainly no coincidence that Lewis Carroll, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien and Phillip Pullman all studied or taught at Oxford University. The University so dominates the centre of Oxford both physically and imaginatively that Oxford as a fictional setting carries unavoidable associations of intellectualism. Hollywood cinema has occasionally exported all-American characters to the University setting in order to create dramatic or humorous counterpoint. In A Yank at Oxford (1938) rugged Lee Sheridan (Robert Taylor) is prized for his physical prowess on the running track and rowing on the river, but his forthright masculinity gets him into trouble with married and flirtatious Elsa (Vivien Leigh). Oxford Blues (1984) also contrasts the physicality and cocky sex appeal of its star Rob Lowe with a parade of eloquent but spineless English undergrads. It is also notable for completely disregarding Oxford’s geography in its construction of space. For a more recent example, consider X-Men: First Class (2011) in which the English Charles Xavier (James McAvoy) is a graduate of Oxford University with mutant powers. These powers make him the ultimate personification of Oxford intellectualism: an all-powerful telepathic brain and (eventually) a worthless incapacitated body. All these narratives are animated by a tension between Oxford intellectualism and American physicality. Whilst none of these films are likely to incite tourist demand individually, as part of a collective imaginary of the city they offer an enticing fantasy for visitors.

However, as visitors to Oxford quickly discover, the city’s intellectual power and its associated spaces are certainly alluring, but they are often inaccessible. There is only very limited access to the inside of the Radcliffe Camera for those without a precious library card, and whilst walking around the city centre, college life with its dorms, dining halls and quads can often only be glimpsed through locked gates carrying signs that unambiguously state “Closed to Tourists”. This is a rude reminder that Oxford’s brand of intellectualism functions as an exclusive club, wonderful and empowering for those inside but opaque and impenetrable to those who are not. Behind closed doors, secrets lurk, and secrets lead to corruption. The corruption of Oxford’s elite has certainly not gone unexplored in narratives set in the city. Indeed the abuse of intellectual power is an important theme of Oxford’s most successful and popular television export: Inspector Morse (1987–2000). Morse is a very useful example of a media tourist driver for several reasons. Firstly, the huge international success of the original and follow up series mean that Morse is a character well known to audiences all over the world. The show’s long-form structure—running at two hours including advert breaks—was unusual for British television when it was first transmitted in the late 1980s, but meant that overseas it could be sold as a “miniseries” or even as a sequence of one-off TV movies. At its peak, the show’s global audience was estimated to be around 1 billion viewers in over 200 countries [11]. Secondly, just as important as the series’ international reach is its strong local flavor. The show makes extensive use of location shooting in and around Oxford, and this is an important element of its high production values and status as “quality television” [12]. Inspector Morse’s convoluted murder mystery plotlines typically rely upon the city’s eccentricities, such as “The Wolvercote Tongue” (first transmitted on Christmas Day in 1988) which has a self-reflexive interest in Oxford tourism as criminal suspicion falls upon tourists, tour guides and even employees of the Ashmolean Museum. Finally, as Steijn Reijnders has pointed out, detective narratives have a topophilic nature, and a particular affinity with tourist activity, in that a fan can literally “follow in the footsteps of his or her beloved inspector, criss-crossing the local community, looking for signs and clues” ([13], p. 177).

As Reijnders suggests, the intense relationship here is not only between narrative and place, but between place and character, the “beloved” detective who is inseparable from the place he or she investigates. By exploring the visited location in detail, sometimes going back over the same spots many times, tourists can find signs which accumulate into a kind of cartography of character: personality as action which takes place on a map. The key elements of Morse’s character all locate him spatially within Oxford and provide suggestive clues for his tourist fans. What separates Morse most clearly from the majority of policeman from British crime drama is that he is presented as a cultured intellectual. In this respect he has more in common with earlier sleuths Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot than his contemporaries, such as John Thaw’s previous role in the genre, the tough-talking DI Jack Regan from The Sweeney (1975–1978). Morse inhabits Oxford intellectualism in both literal and symbolic ways. In the most literal sense, Morse was himself an Oxford undergraduate, although he failed his final degree under mysterious circumstances. This trope places the character in an interestingly ambivalent relationship with the city’s intellectual elite. The show’s plotlines often depict this same elite as corrupt in murderous ways, setting up a problematic relationship between knowledge and power which is perhaps at the heart of the show’s appeal. To give just one example: in “The Last Enemy” (first broadcast in January 1989), a body is found in the Oxford canal, leading Morse to investigate the fellows of a fictional composite college called “Beaumont”. It transpires that rivalry for a senior academic post led to the first murder, committed by another Professor, and a further two killings also take place amongst the college’s academic staff. In Morse’s Oxford, intellectualism gives access to the secretive spaces of the colleges where corruption festers.

Despite this ambivalence around the use and control of knowledge, the detective genre requires knowledge to be gradually gained and acquired throughout the narrative arc. This means that Morse will always be simultaneously enthralled and appalled by Oxford intellectualism; he needs knowledge to do his job, but what he learns is frequently disturbing to the status quo. How Morse gains knowledge is both a physical, located process—he drives (in his vintage Jaguar), walks or runs around Oxford’s landmarks—and an intellectual one: he ponders, thinks and researches like an academic, using theories where evidence is absent or misleading. For example, in his first television film “The Dead of Jericho”, first broadcast in January 1987, Morse attempts to solve a case involving the death of a maternal figure with both a classical (and psychoanalytical) conclusion that “Sophocles did it!” This turns out to be a red herring, but it is a misfire which almost makes sense thanks to the rarefied Oxford setting. The same episode also introduces Morse’s passion for classical music, particularly of the choral or operatic kind. As Pierre Bordieau described, an affiliation with classical music or opera is a particularly strong bearer of cultural capital in Western society due to its perceived inaccessibility or difficultness [14], so Morse’s extensive knowledge of the subject marks him as a middle-class traditionalist. Unlike visual art, novels and films, music does not directly represent landscape or place and it can therefore be thought of as the most abstract and least spatial of the art forms. However, music has a particularly strong connection with emotion and memory, and famous pieces of music build up webs of cultural and personal associations. These associations and memories are often spatially located, so it is certainly not impossible to incorporate music into a multi-media deep map of Morse’s Oxford, especially given that Morse’s use of music within the diegesis is especially localized. Playing records is his major pastime whilst off duty, in fact a brief shot of a turntable with diegetic classical music is usually enough to establish that Morse is at home, but he also sings in a choir which rehearses in recognizable tourist landmarks such as the Holywell Music Rooms.

Music is vital to the characterization of Morse and therefore the show itself, so the producers of one particular guide to Morse’s Oxford showed impressive ingenuity when they included a bonus CD of soundtrack music stapled to the front cover [15]. The potential uses of this music in terms of memory work are very interesting: it could function either as a powerful and exciting reminder of the show whilst planning a trip, or a pleasurable aide memoire of both the show and the trip it inspired in years to come. Doubtless some tourists even bring this type of musical accompaniment with them on portable devices to listen to whilst travelling or even whilst walking round the streets in Morse’s footsteps. In a similar vein, Gundolf Graml’s work on Sound of Music tourism notes the “kinaesthetic experience” of travelling through the Austrian landscape on open-topped tour buses which play music from the film to blur the boundary between filming location and narrative setting ([16], p. 152). Such multimedia approaches to locating screen narratives pre-figure the boundless opportunities presented by the uptake of social media and smartphone technology. Those who are now researching a trip to Oxford and want to explore Morse locations have a multitude of options: from traditional guidebooks, to video guides on YouTube [17], to maps constructed using adaptable mapping technology. Figure 1 shows one example of a user-modified Google Map of Morse’s Oxford including places described in Colin Dexter’s original novels, shooting locations from the television series and even walking routes which, like Reijnders detective tourists “criss-cross” the city centre [18]. When used with an internet enabled smartphone this map and others like it are clearly capable of displaying the tourist’s real location within Morse’s fictional world.

Figure 1.

User-modified Google Map of “Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse” [18]. ©2015 Google.

Figure 1.

User-modified Google Map of “Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse” [18]. ©2015 Google.

Figure 2 is taken from Flickr, a photo sharing service used by keen amateur and semi-professional photographers [19]. Because most images taken with modern devices are automatically “geo-tagged” (i.e., marked with geographical data indicating where there were taken), Flickr can present the uploaded and publicly-shared photographs in the form of a searchable map. Each of the pink dots on the map can be selected to display a preview of the image, which when clicked is opened in higher definition and with comments by users and fans. In this example the possibilities of the internet to enable or even automatically generate deep maps begins to become clear. This map captures images which were inspired by stories; written as novels, adapted onto television screens and then played and replayed around the world. This type of map certainly fits both Heat-Moon and Bodenhamer et al.’s definitions of what a deep map is and how it may enhance our understanding of place and narrative. The images it relays are in themselves fragments of narratives—of tourists’ experiences and fans engagement with fictional heroes—as I will explore in more detail in the following section.

Figure 2.

Flickr’s searchable map of images uploaded in Oxford [19]. © 2012 Digital Globe.

Figure 2.

Flickr’s searchable map of images uploaded in Oxford [19]. © 2012 Digital Globe.

3. “Any of You Harry Potter Fans Recognize Where I’m at?”

Just as with Inspector Morse, the huge global success of the Harry Potter franchise (2001–2011) is well documented, as is the powerful draw of the films for international tourists. Chieko Iwashita’s survey of Japanese tourists visiting the UK in 2002 found that over a third of respondents cited Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001) as the film which had most increased their interest in visiting the UK, and it seems certain that this effect has only intensified as further films in the series were released [20]. However the franchise’s fantastical blending of many different locations with digital effects work makes the location of tourist demand diffuse throughout the UK. Whilst a few “real” locations are named and hence visited (e.g., King’s Cross Station), in the Harry Potter films the landscape of the UK speeds by like a kaleidoscope of spectacular valleys, towering turrets and dusty libraries. Whilst there are certainly keen Harry Potter fans who engage with targeted tourism over large distances, it is important to acknowledge that the lure of visiting a real life bit of Hogwarts in Oxford is generally a part of a larger set of forces. The long queues outside the well-known Potter locations of Christchurch College or the Bodleian Divinity School are made up of much younger fans than those of Inspector Morse, with many still in their teens and therefore unable to make the same types of decisions to travel available to older tourists. Therefore Potter fans come with their families, or in larger school and college coach tour size groups. Such family or school tours would probably have happened even without the additional draw of Harry Potter.

Tourists are complex individuals with a myriad of motivations to travel, and this is one of the primary reasons why establishing the precise impact of film and television products on tourist activity is extremely difficult. One empirical study which rose to this challenge interviewed tourists in Oxford in 2009 and found “it was only 28% true to say that but for screen portrayals they would not have visited Oxford. In other words, it was 72% true to say that they would have visited Oxford anyway, even if they had never seen Oxford or the UK portrayed on screen.” ([21], p. 207). However the same survey also found that 70% of visitors to Oxford had been influenced by screen products to some degree, which given the size of tourist numbers over the summer is still an extremely significant factor. It is no surprise then to find that the choice of destinations within Oxford has clearly been skewed by Harry Potter tourism. The Dean of Christ Church Cathedral stated in 2012 that visitor numbers had grown significantly over the previous decade, and that the average age of visitors was now much lower than before the Potter franchise was released [22]. Even the Bodleian Library acknowledged the power of Potter by including J. K. Rowling’s annotated edition of Harry Potter and The Philosopher’s Stone (1997) in their “Magical Books” exhibition of 2013 alongside Tolkien’s maps and drawings. The multiple motivations of screen tourists are further proof that even deeper maps of the city are required than those which incorporate screen narratives and filming locations. Shopping, cinema-going and café culture are also on the map for younger tourists, just as museums and galleries are vital for more mature visitors.

Due to the complexity of their production processes and the fantastical nature of their mise-en-scène, the Harry Potter films place greater physical and imaginative demands upon their tourist fans than those of other more localized products, such as Inspector Morse. Imaginative work is required because the physical filming locations used are almost always “playing” an imaginary other place. This means that they may look very different “in real life”, as they were expensively dressed or digitally manipulated before making it onto the screen. Christina Lee’s study of Harry Potter tourism argues that the potential disparity between the real and the fictional places is reduced when the locations are “historically authentic”, such as the dining hall of Christ Church College; which is a functioning mess hall for a great educational institution both on and off screen ([23], p. 58). Nonetheless, there remains a layering effect where the pre-existing cultural context of the real location overlaps with the fictional universe. Thus the deep map of Oxford for Harry Potter tourists is complex and multi-layered, comprising lived experience of physical Oxford, much-anticipated but uncertain encounters with the film location itself, and an imaginative interplay between the location and memories of the film’s spectacular imagery. Much of this cognitive work would be difficult to evidence were it not for the fact that the younger average age of the Harry Potter fan means that they are very likely to be heavy users of social media, especially when travelling.

It is plain to those who have witnessed younger tourists in a city such as Oxford that many of them are not just gazing at landmarks, they are also taking photos—often of themselves—with their smart phones, pausing to write brief tags or status updates, and then instantly posting them online. The UK’s media regulator Ofcom carries out an annual survey of media use and attitudes, which in 2015 confirmed that 90% of UK respondents aged 16 to 24 use social media at least once a week, compared to just 44% of those aged 55 to 64. In addition this use is far more likely to be mobile for younger users, who go online via smartphones almost as much as computers or laptops [24]. For international tourists, historically high data roaming charges used to limit internet access abroad, but within the EU this price restriction is less significant since legislative changes in 2014, and in any case densely-populated city centers such as Oxford have a high concentration of free Wi-Fi hotspots for tourists to use when posting online. These rapid technological changes have certainly contributed towards a generational shift in attitudes concerning the public/private divide, especially when it comes to photographs. As social media observer Jacob Silverman puts it: “‘Pics or it didn’t happen’—that is the populist mantra of the social networking age. Show us what you did, so that we may believe and validate it” [25]. Naturally then, for unusual activity such as visiting the shooting location of your favourite film, instantly proving that “it really happened” via images on social media is increasingly important to younger tourists.

The implications of this behavior for the tourist experience as a whole are wide-reaching. As John Urry has noted, taking photos has long been central to the holiday experience as a means of capturing “the tourist gaze” [26], but prior to the uptake of social media the primary use of these images was one of private memory work, or of building narratives to be relayed at a later date to friends and family once back home from a trip. The instantaneous relay of these experiences to one’s “friends” or even to the wider public adds a new dimension of performativity, which is particularly well-suited to the photography habits of the screen tourist. Stefan Roesch’s survey of The Experiences of Film Location Tourists details many variants of playful image making amongst movie fans including “shot re-creations”, “filmic re-enactments” and even “miniature positioning”: for example placing toy figurines of Star Wars characters so that real desert shooting locations form a cinematic backdrop ([27], pp. 159–80). The many thousands of images of Harry Potter fans visiting Oxford locations which are publicly-available on Instagram (a photo sharing service particularly popular amongst younger social media users) tend to be rather more spontaneous and ad hoc in nature, but display a similar passion for embodiment within the cinematic universe.

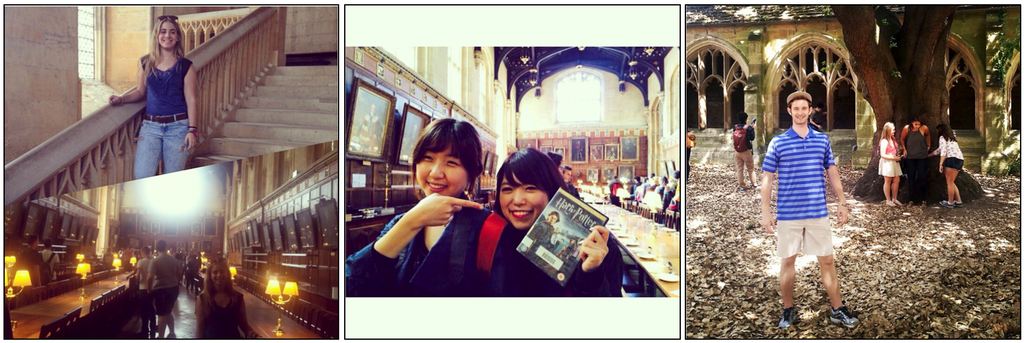

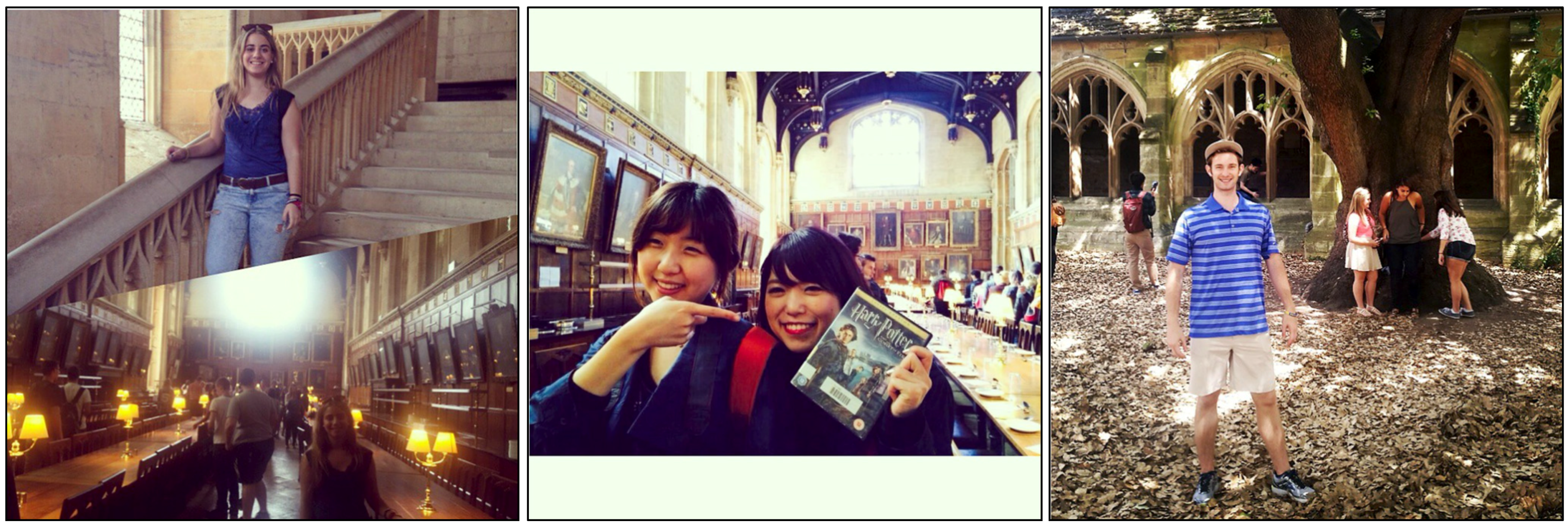

I will discuss just three representative examples of images posted on Instagram in July 2015. In the first, a young woman combines smiling images of herself standing on the stairs of the Divinity School and in Christ Church Dining Hall and comments “Happier? Impossible!” In the second, a pair of young women pose in the same Dining Hall, grinning and pointing at their handy visual prop: the DVD of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002). And finally in the third a young man student stands in the cloisters of New College next to an ancient oak tree recognizable from the franchise and poses the challenge: “Any of you Harry Potter fans recognize where I’m at?” His friend replies: “The real Hogwarts” [28,29,30]. Figure 3 combines these three images, all of which are publicly available on the Instagram service, however the text and comments have been omitted to protect other users’ identities. All three examples display a genuine and infectious excitement on behalf of the screen tourists pictured: big goofy smiles like these are impossible to fake for the camera. Clearly these moments of collision between reality and fantasy are meaningful and pleasurable for a great many people, even including academic researchers, as Sue Beeton’s enthusiastic experience of “The Wizarding World of Harry Potter” confirms [31]. But the fact of their posting on the Instagram service turns these images into something other than private memories: they function more like elements of a conversation between friends and sometimes like-minded strangers. The participants in the larger global conversations sparked by the images are fan communities who can find the images because they are (hash)tagged with key words such as “#harrypotter” or “#hogwartsismyhome”. They are also localized, both via the tag “#oxford” and because, as with the Flickr photos taken by fans of Inspector Morse, they can be presented in the form of a map. Therefore Instagram and its fellow image-sharing services together posit a global map of experience which becomes increasingly deeper as the services mature and accumulate. There is much further research to be done on this subject in order to uncover the riches of these visual sources.

Figure 3.

Instagram photos posted by Harry Potter fans in Oxford [28,29,30].

Figure 3.

Instagram photos posted by Harry Potter fans in Oxford [28,29,30].

4. Conclusions

All maps are an argument about space, and all maps have a purpose. Most obviously, maps help us to navigate unfamiliar terrain and avoid getting lost. They lead us to places which we want to see and help us find places which fulfill our basic needs. They may also demarcate territories and reinforce political power. But as historian of cartography Jerry Brotton argues, maps also fulfill a deeper imaginative function, as they are “always images of elsewhere, imaginatively transporting their viewers to faraway, unknown places” ([32], p. 15). Considering the map as an instrument of fantasy brings us back to the particular focus of this article: international tourists to Oxford who are (at least partly) motivated to travel by cultural texts. When the must-see object is less a building or place than a fictional character that inhabits it, a traditional map is not fit for purpose. What is required is a deeper engagement between place and narrative, a space where stories are just as important as history, and history has many of the best stories. To return to the author’s working environment discussed at the start of this article, when eating lunch on the steps of the Radcliffe Camera in Oxford there are ample opportunities for eavesdropping upon the many walking tours which pause by the building to contemplate its famous curves. Listening for more than a few minutes the same stories get repeated over and over again, echoing round the walls of Radcliffe Square: one favourite with tourists concerns a duck which flew out of the foundations of All Souls College in 1437, prompting a bizarre college tradition involving a moonlight procession led by a “Lord Mallard”.

The telling and retelling of these tall tales highlights the extent to which the tourist experience is made up of stories. Stories provide insight into the place visited, and may be communicated to the tourist via a bewildering array of media. Screen narratives provide compelling characters who inhabit particular places so completely that to visit the place is to feel a deep connection between reality and fantasy. The tools used (and increasingly created) by tourists in order to navigate these imaginary places may be thought of as “deep maps”, in the sense that they “capture a plethora of interconnected stories from a particular location” [4]. They are guides not just to finding filming locations but also ways to understand “the personalities, emotions, values and poetics, the visible and the invisible aspects of a place” [9]. They are heavily mediated and re-mediated, and yet they clearly provide meaningful emotional experiences for visitors who may be searching for clues like Inspector Morse or marveling at the magical places touched by Harry Potter himself. In this sense, screen tourist activity participates in a collective deep mapping of destinations such as Oxford, enabling all visitors, be they day-trippers or visiting scholars, to navigate the relationship between narrative and place.

Acknowledgments

The ideas in this article were first explored in a conference paper given at the ECREA Conference at the University of Lund in 2013. My thanks go to the organizers of this event and the participants who provided useful feedback. A similar debt is due to those attending the recent symposium “Developing Film Tourism: Theory and Practice” held at the University of Glasgow in May 2015. In particular I want to acknowledge the influence of an instructive paper given in Glasgow by Meghann Ormond on embodiment in medical tourism. Finally, many thanks to Instagram users Misako Kawamura, Matthew Holt and Carmen Temmler for giving permission to use their images in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Leshu Torchin. “Location, Location, Location: The Destination of the Manhattan TV Tour.” Tourist Studies 2 (2002): 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon Ford. The Situationist International: A User’s Guide. London: Black Dog, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- William Least Heat-Moon. Prairyerth: A Deep Map. London: Deutsch, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Susan Naramore Mayer. Deep Map Country: Literary Cartography of the Great Plains. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Julia Hallam, and Les Roberts. Locating the Moving Image: New Approaches to Film and Place. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tony Reeves. The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations, 3rd ed. London: Titan Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bill Leonard. The Oxford of Inspector Morse and Lewis. Stroud: Tempus, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Les Roberts. “Projecting Place: Location Mapping, Consumption and Cinematic Tourism.” In The City and the Moving Image: Urban Projections. Edited by Richard Koeck and Les Roberts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- David J. Bodenhamer, Trevor M. Harris, and John Corrigan. “Deep Mapping and the Spatial Humanities.” International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 7 (2013): 170–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip Pullman. Lyra’s Oxford. London: Corgi Books, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- William Gallagher. “Morse’s Last Grumble.” BBC News. 14 November 2002. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/1022958.stm (accessed on 27 May 2015).

- Lyn Thomas. “In Love with Inspector Morse: Feminist Subculture and Quality Television.” Feminist Review 51 (1995): 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stijn Reijnders. “Watching the Detectives: Inside the Guilty Landscapes of Inspector Morse, Baantjer and Wallander.” European Journal of Communication 24 (2009): 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre Bourdieu. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Annie Bullen. Morse in Oxford. Andover: Pitkin, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gundolf Graml. “(Re)mapping the Nation: Sound of Music Tourism and National Identity in Austria, ca 2000 CE.” Tourist Studies 4 (2004): 137–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studio 8 Video Production. “Inspector Morse’s Oxford: Introduction.” 2010. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QrexVyBDn1o (accessed on 2 July 2015).

- Google Maps. “Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse.” 2015. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=zEiHoRM0-99k.kD_DPkIlS_0c (accessed on 2 July 2015).

- Flickr. “World Map.” 2015. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/tags/inspector%20morse/map?&fLat=51.7507&fLon=-1.257&zl=16 (accessed on 16 July 2015).

- Chieko Iwashita. “Roles of Films and Television Dramas in International Tourism: The Case of Japanese Tourists to the UK.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 24 (2008): 139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anita Fernandez Young, and Robert Young. “Measuring the Effects of Film and Television on Tourism to Screen Locations: A Theoretical and Empirical Perspective.” Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 24 (2008): 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. “Harry Potter Fans Boost Oxford Christ Church Cathedral.” BBC News. 25 March 2012. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-17434129 (accessed on 28 February 2015).

- Christina Lee. “‘Have Magic, Will Travel’: Tourism and Harry Potter’s United (Magical) Kingdom.” Tourist Studies 12 (2012): 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofcom. “Adults Media Use and Attitudes Report 2015.” 2015. Available online: http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/market-data-research/other/research-publications/adults/media-lit-10years/ (accessed on 6 June 2015).

- Jacob Silvermann. “‘Pics or it didn’t happen’: The Mantra of the Instagram Era.” The Guardian. 26 February 2015. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/news/2015/feb/26/pics-or-it-didnt-happen-mantra-instagram-era-facebook-twitter (accessed on 25 March 2015).

- John Urry, and Jonas Larsen. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. Theory, Culture & Society. London: SAGE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stefan Roesch. The Experiences of Film Location Tourists. Bristol: Channel View, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carmen Temmler. “Happier? Impossible! ” 2015. Available online: https://instagram.com/p/5X4JasCUEQ/ (accessed on 21 July 2015).

- Misako Kawamura. “#canteen of #HarryPotter.” 2015. Available online: https://instagram.com/p/5ZotzKpfqT/ (accessed on 21 July 2015).

- Matthew Holt. “Any of you Harry Potter fans recognize where I’m at? ” 2015. Available online: https://instagram.com/p/5W8tiPL15t/ (accessed on 21 July 2015).

- Sue Beeton. Travel, Tourism and the Moving Image. Bristol: Channel View Publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jerry Brotton. A History of the World in Twelve Maps. London: Allen Lane, 2012. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).