2. Long Street: Street of Differences

In the introduction to

Imagining the City [

11], Steve Field describes different positions from which Cape Town can be observed. He gives the example of two rhetorical images through which Cape Town is represented for tourists (that of the gateway to Africa and the multicultural Cape Town of the Rainbow Nation.) The first scene includes: “Devil’s Peak, Table Mountain, Lion’s Head and Signal Hill, and the city center located between the mountains and the bay” ([

11], p. 6). The second includes: “The center of the view is of sprawling suburbs from the edge of Devil’s Peak and the Cape Flats, reaching as far as the outer limits of Khayelitsha. The view is framed at the edges by Table Bay to the north and False Bay to the south, and is best observed from the vantage point of Rhodes Memorial, the monument erected in honour of the architect of imperial conquest, Cecil John Rhodes” ([

11], p. 6).

Each of these images reveals different aspects of Cape Town, but, as Field notes, these images both reveal and conceal. One of the most interesting aspects of the first image is the “hidden perspective of the viewer,” which is the point where the image is taken: Blouberg Beach. During Apartheid, this beach was a “white only area.” “For the majority of Capetonians classified colored, African and Asian, it was for many decades one amongst many sites of racist exclusion by the apartheid government” ([

11], p. 12).

Through this example, Field wants to suggest that no representation (written or visual) of the city can be considered complete and comprehensive. Every view of the city is necessarily selective and cannot capture it fully in its complexity. As a representation reveals something of the object it wants to show, it conceals something of it too. This example is particularly significant in studying South African cities in the post-apartheid period; as Mbembe and Nuttal have noted, they were often observed through the lens of a single development paradigm ([

12], p. 8), often more concerned “with whether the city is changing along vectors of institutional governance, deracialisation of service provision and local politics than with citiness as such” ([

12], p. 9).

Nonetheless, few studies have focused on the different ways of perceiving the urban territory by regular people. Recently, among many scholars of post-Apartheid phenomenon, the need has arisen to abandon the broad generalizations that framed the relationship between the public and urban places within and adopt more complex approaches that can observe processes of signifying urban places, keeping aware of their discontinuous and contradictory character. (Mbembe & Nuttal [

13], Murray [

12], Field, Meyer, Swanson, [

11]). Field, for example, suggests a reading of Cape Town in which the city is observed through meanings produced from below, through the memories, imaginations, and thoughts of regular people. “We assert the centrality of people’s creative attempts to construct, contest and maintain a material and emotionally secure sense of place and identity in Cape Town” (Field [

11], p. 7). The author’s choice is in keeping with a tendency shared by many South African authors, who have shown distaste for the tendency to see the post-apartheid city in a monologic and verticalistic view. Drawing from these works, in my project I intended to explore Cape Town through a multiple perspective model of exploration, observing it through the different viewpoints of its inhabitants.

In order to pursue my objectives, I decided to take Long Street as a starting point for my research. One of Cape Town’s oldest streets, it is known as one of the most diverse, mixed places in the city. Since apartheid, Long Street has been considered a tolerant, liberal space, in some ways separate from the rigid social control of other areas of Cape Town. Despite the many restrictions, here people of different races continue to live in a relatively cordial atmosphere, far from the state of tension that pervaded other areas of the city. In the post-apartheid period, the street continued to be a crossroads of people of different races, geographic origins, and economic and socio-cultural backgrounds. The street is seen as divided into two parts: Lower Long Street and Upper Long Street. The lower part includes many offices and the headquarters of major companies and national and international banks. The lower part has many shops, restaurants, night clubs, coffee shops, sex shops, small hotels and bed and breakfasts.

Every evening, and especially on weekends, this part of the street is invaded by people who come from different areas of the city and from other parts of the world. There are students from Rondebosch and Observatory, arriving by taxi or private car. I met Mike, a young German man, who had lived in South Africa for several years, having done his PhD and then his post-doc there. He had married a black woman from Zimbabwe and explained to me that she preferred frequenting areas like Observatory and Long Street “where mixed couples are not the exception.”

There are young people from the townships who have come to Long Street by minibus and will not return home before the next morning, when the first public transport leaves for Langa, Kayelithsa or Nyanga. Some wear pins and symbols which extol the African National Congress and give a clear indication of their ideological stance. Many of them are poor, often unemployed, and others have menial jobs; Shumbuko, a young Zulu living in Kayelitsha explained to me that being in Long Street for the evening and not in a township bar or shebeen is already a real privilege:

“I come here often because I work here, but there are guys who, even though they live in Cape Town, have never been to Long Street.”

Shumbuko’s dream is to “make loads of money.” His role-models are the so-called “black diamonds,” prototypes of the new upwardly mobile black middle class. Shumbuko explains that they are “the idols and forbidden dream of the boys and girls from the townships and the nightmare of the new white working class.” In this area of the city, it is not unusual to see them hurtling past in high-powered Mercedes and Audis, dressed in pure silk shirts and often with ostentatious jewelry.

The tourists who stay in Long Street’s bed and breakfasts usually move around in groups, discussing how to spend the evening under its porticos. One of them has a T-shirt that says “Googletu,” ironically combining the name of the most-visited search engine in the world with that of the city’s poorest and most marginal township: Guguletu. This wordplay humorizes, defuses and distances the destitution and violence of Cape Town’s urban slums.

Upper Long Street is also somewhere you can find a job; many taxi drivers have found work on Long Street. Often they come from other African countries. Lying in wait outside the busiest bars and clubs, Long Street’s taxi drivers study their customers and, over time, can develop into “spontaneous anthropologists,” adept at spotting potential regular customers at first sight. Desmond, a refugee from Zimbabwe who has become a Cape Town taxi driver, explained to me how being able to spot a customer immediately can “enable you to have a wage for several months”; just as not spotting one can mean “putting your life on the line.” The singular character of Upper Long Street has its origin in the heterogeneous nature of the voices which pass along it. Different needs, desires, and possibilities, different economic, psychological and social backgrounds all meet up and intersect here.

I often ended up heading for The Stones: a large billiard hall, which becomes a dance club on weekends. Customers can have a break on one of The Stone’s balconies while they smoke a cigarette or have a drink and watch passersby down on the street. I would stay there for hours, observing the people walking along the street. Some were dancing, others drunk; sometimes I saw tourists walking by very quickly because they were afraid, while some drug dealers were trying to sell drugs to the passersby.

After a few months, I learned to recognize different characters who seemed like extras in a play to me. Mumford compared the city to a theater, “a collective experience in which dwellers are actors rather than merely spectators in the drama of urban life” ([

14], p. 2). Long Street struck me as a theater stage whose habitués could play particular roles on it. In the Pretoria, a bar frequented by a predominantly black clientele, I got to know Jane, a prostitute from Mali, who would pick up her clients there. One day I saw her wearing a T-shirt with the slogan “No money: No honey.” Like on a stage, Jane played the role of herself, taking on a particular role and giving different personalities to the other characters who were “acting” on her stage. She knew the street’s every nook and cranny and would study the behavior of her potential clients who she had even subdivided into twelve categories: “There are clients who want to be with you for a night; these ones just want sex. There are those who want to stay with you for a few days; these ones want company. There are those who want a relationship; you can stay with those for months, even years...”

Sometimes I would go out onto the street and walk around listening to how the different types of music, sounds and voices emanating from the bars overlapped. For me this interwoven palimpsest of sounds brought to mind another of the city’s polyphonies: those of the submerged voices, of the personal histories from the deepest levels, familiar to no one, but which become superimposed in the street through the meanings that their life experiences elicited. “To capture the hidden meanings,” and “to reveal the invisible”—this is how I see the role of anthropology. I would have liked to capture all the meanings of Long Street, but the street was incommensurable and my view only partial. I decided to surrender myself to its polyphony.

After many months spent in the field, I had given up on the idea of finding an explicative synthesis and had started to accept the contradictions of the street. In order to capture the multiplicity of the voices of Long Street I had had to lose myself within it. By listening to the life stories of my interviewees and going through the places of the city with them, I had observed it from different points of view, adopting the perspective of the taxi driver, the young middleclass man out for a good time, the tourist, or the prostitute.

By observing Long Street, I have discovered how my fieldwork is made up of the multiplicity of the viewpoints of people whose lives follow different paths, who have different aspirations, dreams, desires and fears. Every time I attempted to find a “synthesis” for Long Street, to find a stable and definitive viewpoint to which a single meaning could be anchored, it crumbled before the multiplicity of the street’s voices.

Long Street could not be considered as a single subject; there were an infinite number of Long Streets, as many as the points of view people had on it, and these changed continually depending on how it was regarded: the time of the day, everyday events, meetings and fleeting thoughts which constantly transformed the lives of my interviewees. Long Street could be observed only by accepting its heterogeneous nature. Long Street is marked by the continuous flow of different viewpoints, voices, behaviors, different ways of perceiving its urban spaces that do not converge in a single homogenizing perspective, branching instead into a polyphonic view. Bauman compares the identity of modern society to a prism through which different aspects of contemporary life are codified and understood ([

15], p. 471). We can use the same metaphor to observe the identity of urban spaces: Long Street, in this instance. The street was ensnared in the paradox of being unique and multiple at the same time. Like a prism, though it was defined by a single organism, it could reflect the various identities that crossed through it.

I wondered how I could represent such enormity. The only way to represent Long Street in its entirety and totality would be to create a map representation that could include each building, establishment, alley, traffic light, and object in it and try to understand the meaning it had for each of its regulars. This solution was not only unrealistic, but would also be useless and fruitless.

The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, in the short story “On Exactitude in Science” [

16], envisions a realm where the art of cartography is so important that the map of a province covered the entire area of the city. In this story, Borges narrates the story of a cartographer who creates a map so vast and accurate that it covers the entire kingdom. However, later generations found this representation so useless and meaningless that they decided to leave it to the “Inclemencies of Sun and Winters” in the “deserts of the West.” In this story, Borges poetically suggests that any attempt to represent a territory in its entirety is both useless and destined to fail. A map that tries to assimilate the territory which it is intended to represent in a total way, conceals the intention of negating its otherness; it is a delirium of omnipotence. No scientific or artistic representation, and especially no ethnographic representation, will ever coincide with the actual object. The attempt to assimilate the other (whether a person, a social group, a ritual, or an urban territory) in its totality entails the very negation of its essence. Emmanuel Levinas [

17] noted that it was only through recognizing the otherness of the other that can we establish any kind of a relationship based on recognition. Discovering Long Street let me recognize it in its incommensurate, unrepresentable nature. Attempting to portray it completely meant more than venturing on an ill-advised path; it meant threatening its otherness. But if the map of Long Street, like any kind of map, can never grasp the territory in its entirety, which aspects should I consider and which should I ignore? And what point of view should I take to describe it?

3. Bateson at Cape Town

On this point, an important source of inspiration came from one of Gregory Bateson’s early works,

Naven (1958), in which he explores a ritual of sexual inversion of the Iatmul people of the Skip River in New Guinea). Bateson organizes his work into a series of chapters in which he observes the ritual through different analytical perspectives.

Naven was initially met with very little attention, but later was reevaluated and became an anticipatory example of post-modern ethnography. George Marcus [

18] cites it as an example of a text for the new alternative forms of ethnographic representation: “Bateson’s experimental ethnography, which worries over several alternative analyses of a single ritual of a New Guinea tribe, is remarkable precisely because it was exceptional and unassimilated in the anthropological literature for such a long time, but now is an inspirational text in the current trend of experimentation” ([

18], pp. 40–41). According to Marcus, what ties Bateson’s anthropology with post-modern experimental trends is precisely its multi-perspective and multi-narrative approach: “One common idea of text construction is to string together a set of separate essays dealing with different themes of interpretation of the same subject” ([

19], p. 192). James Clifford considers

Naven’s methodological collage as a major forebear of the poetics and politics of cultural inventions. It can be considered an example of what he calls ethnographic surrealism: “The ethnography as a collage would leave manifest the constructivist procedures of ethnography knowledge: it would be an assemblage containing voices other than the ethnographer’s, as well as an example of “found” evidence data not fully integrated within the work’s governing interpretation” ([

20], p. 147).

In many ways,

Naven can be considered a precursor of major ideas that have recently informed the study of cartography and the practice of mapping in general. Over the last twenty years, interest in maps and the practice of “mapping” has grown in several disciplines, including anthropology, cultural studies, marketing, museum studies, architecture and popular music studies. Les Roberts [

21] has emphasized how this interest can be traced to the impact of a epistemological reorientation, called a “spatial turn,” in which scholars in diverse disciplines approached their field of interest with a flourishing “spatial critical imagination,” finding its “defining trope” ([

21], p. 18) in the use of maps. At the same time, disciplines like geography and cartography, which have traditionally used maps as analysis tools, have started to reconsider the very nature of maps as a tool of representing reality. This “cartographic turn” was bolstered by the publication of

Maps, Knowledge and Power (1988) in which Brian Harley presented an analysis of the social nature of map representations with its connections to political power. The authors reconsider the idea—widespread since the Enlightenment—that maps are a neutral, objective representation of the world. He highlights that maps can only be understood in light of the historical, political and social context in which they were made. Maps, far from presenting “the truth of the world,” were and are “social constructions presenting subjective versions of reality” ([

22], p. 43). From this perspective, a map, any map, can only be read as a historical and social product situated in a specific context and in light of the cultural values driving its maker. According to Harley, maps act as metaphors for a “discourse” (meant as a system of meanings) that is more general than what they reference. The sense of the map as a “mirror of nature” ([

22], p. 34) comes from the non-recognition of discourses (contained in them). The author considered the deconstruction of a map as a tactic of reading through which we can challenge “the apparent honesty of the image.” ([

23], p. 21) While it is true, in the words of Jeremy Crampton [

24], that the practice of mapping has been continually contested, Harley’s challenge to the presumed scientific objective of maps helped generate a more explicit critique of cartography, with renewed interest about the practice of cartography and mapping in general. Several scholars have studied the practice of mapping by researching the historical, political and ideological contexts in which the practice emerged and developed (Anderson [

25], Cosgrove [

26], Dodge, Kitchin, Perkins [

27], Wood [

28]). Like Bateson, the cartographic critics start from the assumption that no map can be considered a faithful replica of the territory, and every representation must be read and considered as a limited vantage point of the observer. The analytical convergence between Bateson and scholars of cartographic criticism leaves room for adopting models of multiple observation and representation of the same territory.

Drawing from these ideas, I envisioned a map of the city that could observe, describe and represent its inhabitants’ different ways of perceiving the city. This map could not be considered a mere representation of the city, but rather an observation of how its inhabitants produce the territory. As Bateson said, the appreciation of differences is not just recognizing the traits of a territory or multiplying viewpoints on it, but it is the differences that arise and develop from the relationship between the two agents. Accordingly, in my map, I sought to identify the discrepancies in the different ways that its inhabitants relate to the territory, perceive it and relate it to their own socio-cultural situations and individual lives.

4. On Method

In building a map of Long Street, I drew from several sources both from the worlds of art and ethnographic research.

One of the most important sources of inspiration came French surrealists’ deambulations. In surrealist thought, the act of wandering aimlessly is considered related to the practice of automatic writing, through which they sought to explore the spontaneous mechanisms of human thought. The French surrealists saw space as an empathic place (an active, living subject), with which they could forge a mutual dialog. The act of wandering can be seen, in this sense, as an attempt to explore a place’s invisible reality, as well as a way to investigate unexplored facets of one’s inner life (or ones that could not be explored otherwise). Inspired by surrealism, I sought to explore the memories, hopes and desires of my interviewees by wandering through the city. As in the surrealists’ deambulations, I considered Cape Town’s urban territory as an empathetic territory through which I could investigate the inner lives of its inhabitants. Wandering through the city’s streets with the interviewees, I explored their memories, hopes and desires in relationship to the city’s urban spaces.

Another essential contribution came from Andrew Irving’s research in Kampala, London, and New York about how HIV-positive individuals perceived the urban territory (2004–2008). Irving’s method involved identifying different places in the city that the interviewees considered important for their personal experience connected to the disease. He intends these places as performance stages where the most important moments of their experience can be explored and performed. Revisiting a house abandoned in the outskirts of Kampala lets an interviewee explore the moments when he likely contracted the HIV virus; returning to the room of a hospital evokes the moment when he learned that he had contracted the virus. Moving through the city’s areas with his interviewees, Irving traces urban pathways intended as mnemonic and emotional itineraries. This type of urban movement can be understood as a form of mapping the territory through which the inhabitants attribute meanings to urban spaces in the light of their introspective journeys. Irving’s walking fieldwork is not merely a tactic for gathering data from the urban territory; on the contrary, it can be seen as a way of making place. By wandering through the city and projecting their memories, fears, hopes and emotions on the urban spaces, Irving’s interviewees create urban pathways through which the city’s urban territory takes on different meanings. Though Irving never produced a map of his work, walking fieldwork can be considered a practice of mapping in which the city’s territory is not only rediscovered but also continuously recreated by its inhabitants.

In recent studies related to cartography, we have seen new theoretical directions, among which we could include a post-representationalist perspective in which the relationship between map and territory is less clear and delineated than it had been previously. Several authors (James Corner [

3], Tim Ingold [

8], Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge [

27], Vincent Del Casino and Stephen Hanna [

29]) have contrasted the static, stable conception of the structural school, favoring a dynamic conception based on peformativity in which the map is seen a process, or rather a “constellation of ongoing process” ([

27], p. 547). Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin and Chris Perkins have noted that this approach reflects “a philosophical shift towards performance and mobility and away from essence and material stability” ([

27], p. 554). The map stops being considered a fixed, stable product and is seen as something in a state of becoming. Vincent Del Casino and Stephen Hanna see the map as a flux in which each encounter produces new meanings and engagements with the world. “Maps,” they write, “are not simply representations of particular contexts, space and time” ([

29], p. 42). On the contrary, “they are mobile subjects infused with meaning through contested, complex, inter-textual and interrelated sites of social-spatial practices.” ([

29], p. 42). The map is a process in a constant state of becoming, created through a series of practices that are reflected in how the territory is understood. “It can be seen as, far from fixed, unmoving entities” ([

29], p. 45) In a study in the historical Town of Fredericksburg in Virginia, they explored how visitors to the town were able to enrich the meaning of tourist maps through contact with the territory, and how, at the same time, the map was a tool through which they could give a particular meaning to the town’s places. Map and territory are understood as co-constituting agents to the extent that we cannot recognize how much the map is built by the territory and the territory by the map. Map and territory can be understood only in the light of the complex, interdependent relationship between them. Comparably, Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge emphasized how maps cannot be understood as “secure representations” but rather as “a set of unfolding practices” ([

27], p. 557). Maps are transitory and fleeting, being contingent, relational and context dependent” ([

27], p. 559).

Drawing from these works, we can envision building a map based on urban movement that aims to represent a city through the different ways its inhabitants have of producing the territory. Put differently, we can imagine a map of the city made up of different urban pathways chosen and built by the city’s inhabitants by wandering in the city and which do not just represent the territory but recreate it. Borrowing from the French surrealists’ deambulations and Irving’s walking fieldwork technique, I built a map of the city through the urban movement of its inhabitants. However, in my case, urban movement was seen as more than a tactic for exploring the relationship between my interviewees’ inner worlds and the city’s urban spaces; it had the ultimate aim of revealing how the relation to different social groups, economic conditions and personal experiences led the people of Cape Town to map the urban territory differently.

At the beginning, I chose ten regulars of Long Street who had different traits in terms of gender, language, race, political orientation, economic level and socio-cultural background. I then asked my interviewees to choose ten places in the city that had particular importance for them because of being (directly or indirectly) tied to their personal experiences. Next, I asked my interviewees to move through the city’s places, re-evoking the feelings and impressions that were elicited. These places were seen as mnemonic and emotional areas in which they remembered and evoked important memories from their pasts. While taking the urban pathways I photographed the places, recorded the interviews and wrote down their comments. In the final phase, I asked my interviewees to explore the pathways we took, showing their routes drawn on a sheet of paper and the pictures taken on the pathways, taking notes of the comments and memories aroused by this phase of map and photo eliciting.

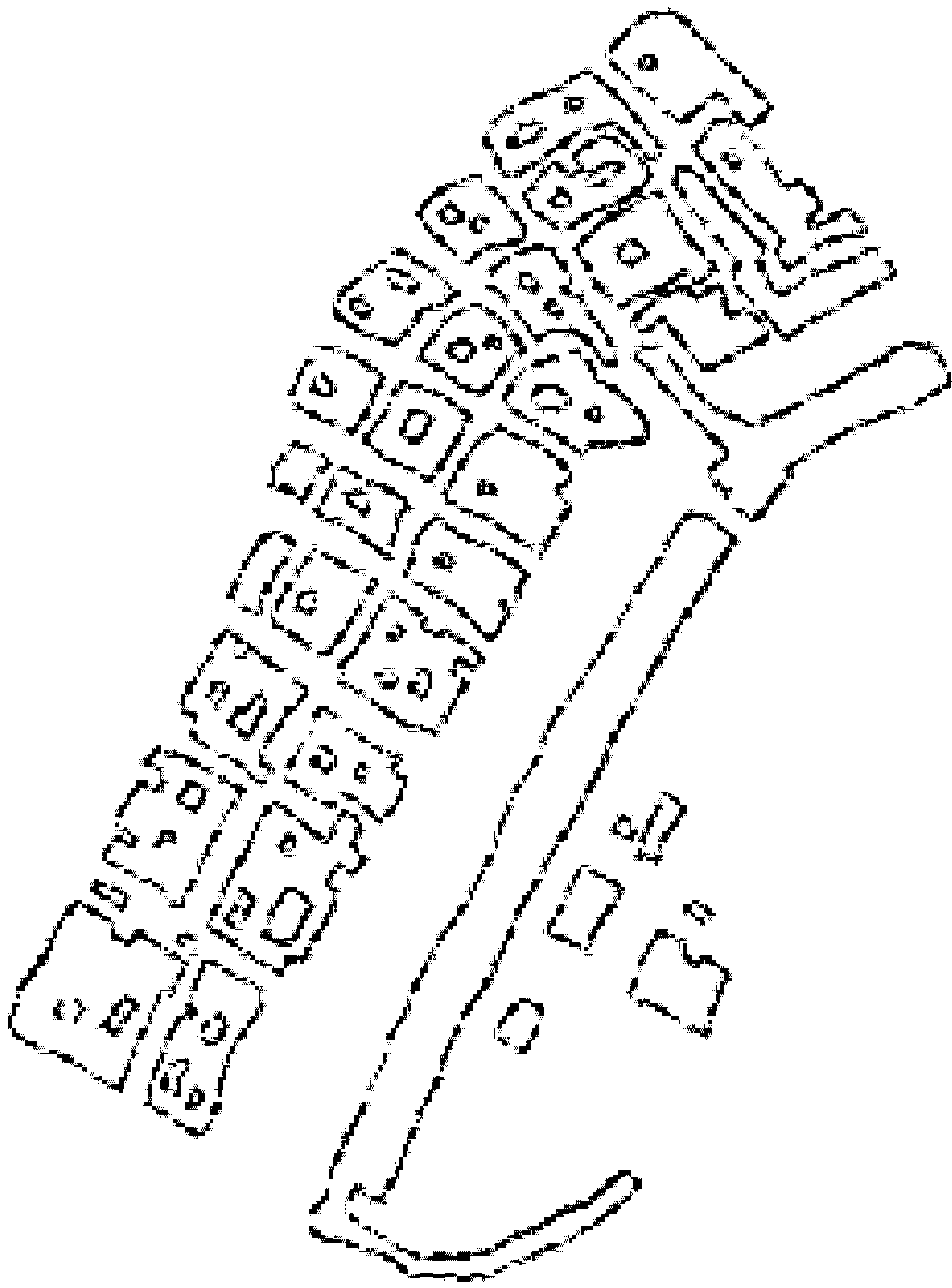

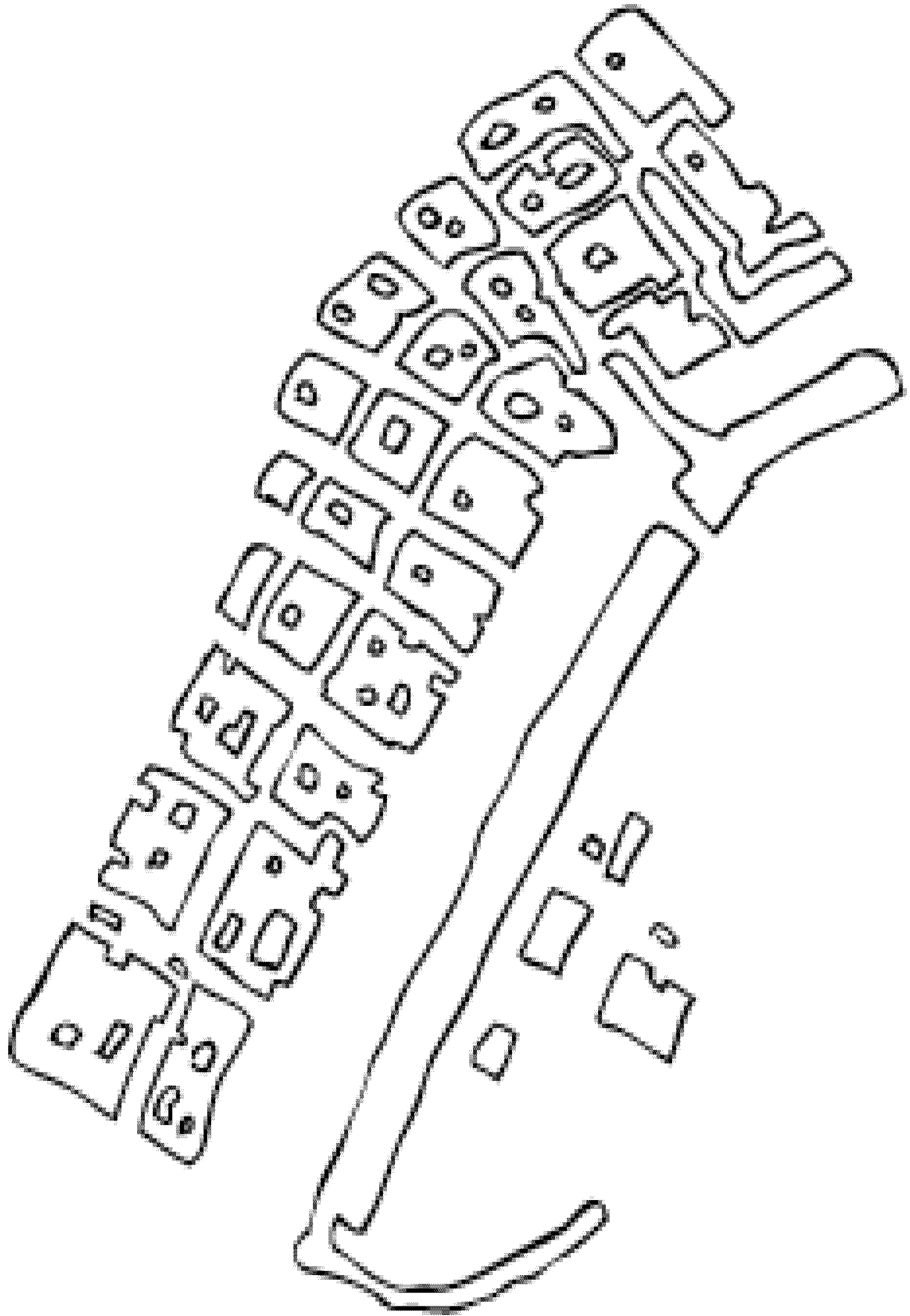

The first step entailed tracing lines to mark the pathways that I had taken in the city by myself and with my interviewees, drawing the places where we did the interviews. I personally drew the territorial stages, taking inspiration from a photographic map of the city. The drawings are intentionally approximate and do not faithfully reflect these areas (

Figure 1). My goal was to represent the “distance” between my topographic representation and the urban territory.

In a second phase, I included writings on my map taken from conversations I had with my interviewees and put them in relationship to the urban pathways taken. The writings serve to represent the urban territory through the meanings that its people attribute to them. By aligning with writings taken from interviews with the drawings on the map, a meaning can be attributed to them. The second function of the writings is to orient visitors in discovering the city. By relating the writings with the lines drawn on the map, readers can go over the urban pathways taken during the interview and match them with the interviewees’ mnemonic reconstructions.

For example, in an interview with Kay, a 35-year-old black woman originally from a town in Western Cape who came to Cape Town when she was 20, I traced the most important moments of her experience in the city. She remembered the period when she was involved with a Russian man and told me how the fact that she was going out with a “white man” let her access a world from which she felt excluded. Walking by Camps Bay, she remembered a day when she went to a restaurant with her boyfriend and was served by a white waitress for the first time in her life. She said:

“One night we came here and there was a white waitress serving the tables. When I saw her I felt a sense of triumph. I’d spent many years of my life listening to white customers’ protests and complaints, often while keeping a forced smile on my face. Now I was on the other side of the fence. I went into the restaurant, she greeted me and I didn’t reply and put my arm around my partner: it felt fantastic.”

Connecting a phrase from an interview with Kay to the representation of Camps Bay, I started to map the pathway taken with her (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

“Now I was on the other side of the fence.”

Figure 2.

“Now I was on the other side of the fence.”

In an interview conducted with Ibrahim, a young Somali man who came to Cape Town in search of a city where he could live freely as a homosexual, I went to the club where he had his first job and where he felt free to express himself for the first time.

“I’ve found this work thanks to a friend. A foreigner guy who had many contacts in the gay environment of Cape Town. When he told me that I had a job, I could not believe that. When I cross the door of the club it was like passing the finishing line of a long walk that I did for years. Here things have changed completely. I’ve started dressing and speaking as I like. Acting and pretending are what had characterized my whole life. Acting, playing a part was a pleasant feeling, because I could maintain a secret identity, I could cherish it and protect it. In a certain sense, acting gave me the freedom to be myself in the purest sense, because the mask I put on protected me. Coming here brought about a transformation in my life and in a certain sense I’ve stopped acting. When I started working here, I discovered another part of myself. It was like I was hiding all over again (

Figure 3).”

Figure 3.

“When I cross the door of the club it was like passing the finishing line of a long walk that I did for years.”

Figure 3.

“When I cross the door of the club it was like passing the finishing line of a long walk that I did for years.”

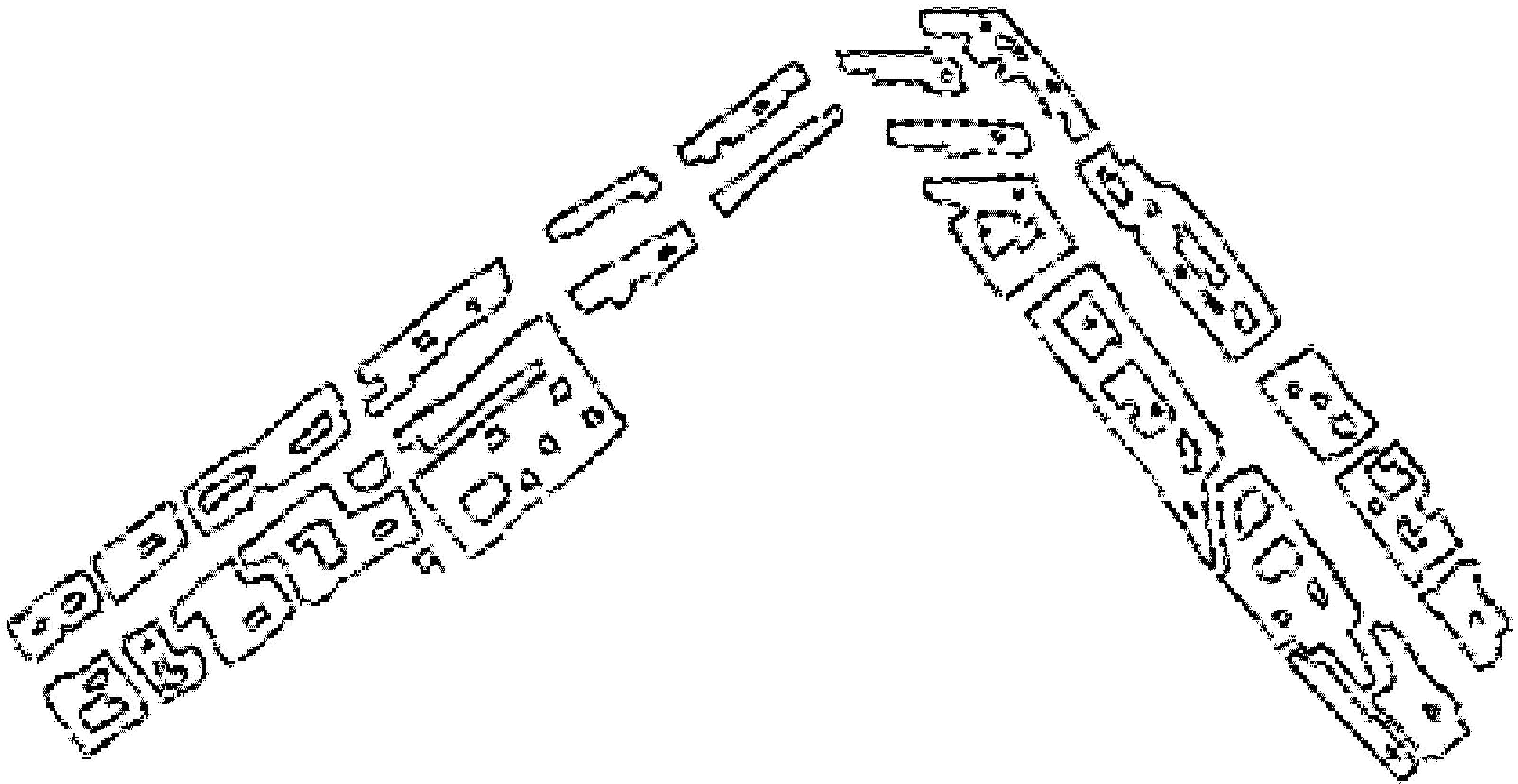

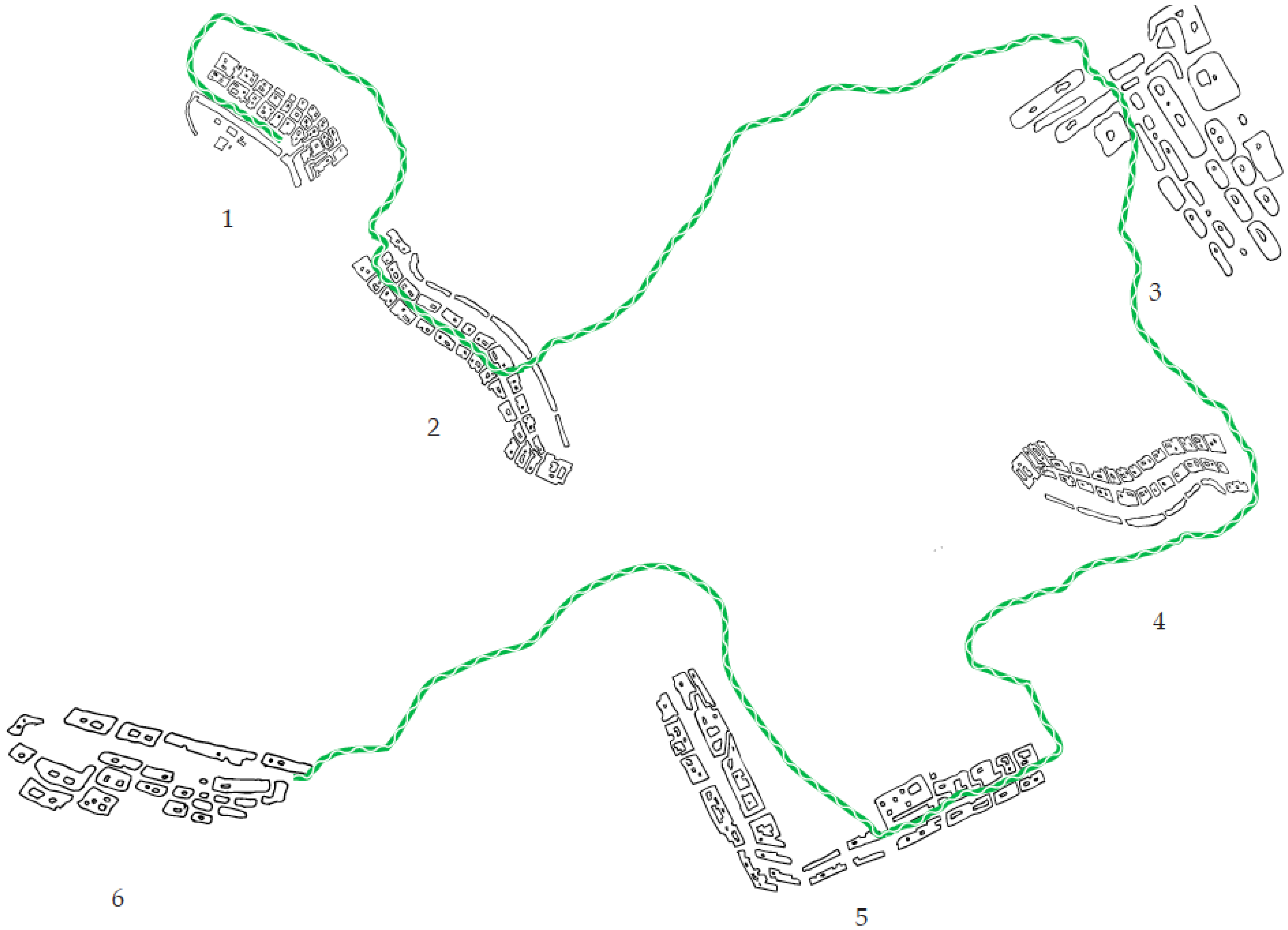

In a third phase, I connected the territorial stages through some vectors representing the urban pathways taken with my interviewees. The vectors suggest a possible movement, but leave open the option of taking other pathways. Recalling

The Naked City [

30] by Guy Debord, the city is intended as a psychological landscape comprised of holes. Entire parts are forgotten or erased to build entire possible cities in the empty space. The model is an archipelago, a series of islands surrounded by an empty sea cut through by wanderings (

Figure 4). The empty space that separates the territorial stages underscores the possibility of taking new urban pathways and developing new interpretations. The map is simultaneously an invitation to take the pathways already marked and an invitation to get lost amidst its different ethnographic landscapes.

Figure 4.

Ibrahim pathway.

Figure 4.

Ibrahim pathway.

A third element of the map is made up of pictures portraying where we went and taken in the pathways. The function of these pictures in an exploratory sense was both to orientate a discovery of the city, establishing points of reference, and evoking memories in the interviewees in the photo elicitation phase. Likewise, placing the photographs (e.g.,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) on the city map, I sought to guide readers to discover the city, showing the places that we passed through during the research phase. By putting the photographs into relief with the writings and drawings, readers can reconstruct the urban pathways.

The last step for building the map was assembling the data. In this phase, I thought of how to put together the elements that I had collected in my work and how I could represent Long Street.

A suggestion on how to think about this came out of a happenstance visit to the District Six Museum in Cape Town and the discovery of the district’s map. The memorializing District Six Museum is one of the museums in Cape Town that is most recognized internationally. The aim of the museum is to promote social justice “as a space for reflection and contemplation, and as an institution for challenging the distortions and half-truths, which propped up the history of Cape Town and South Africa.” ([

31], p. 152).

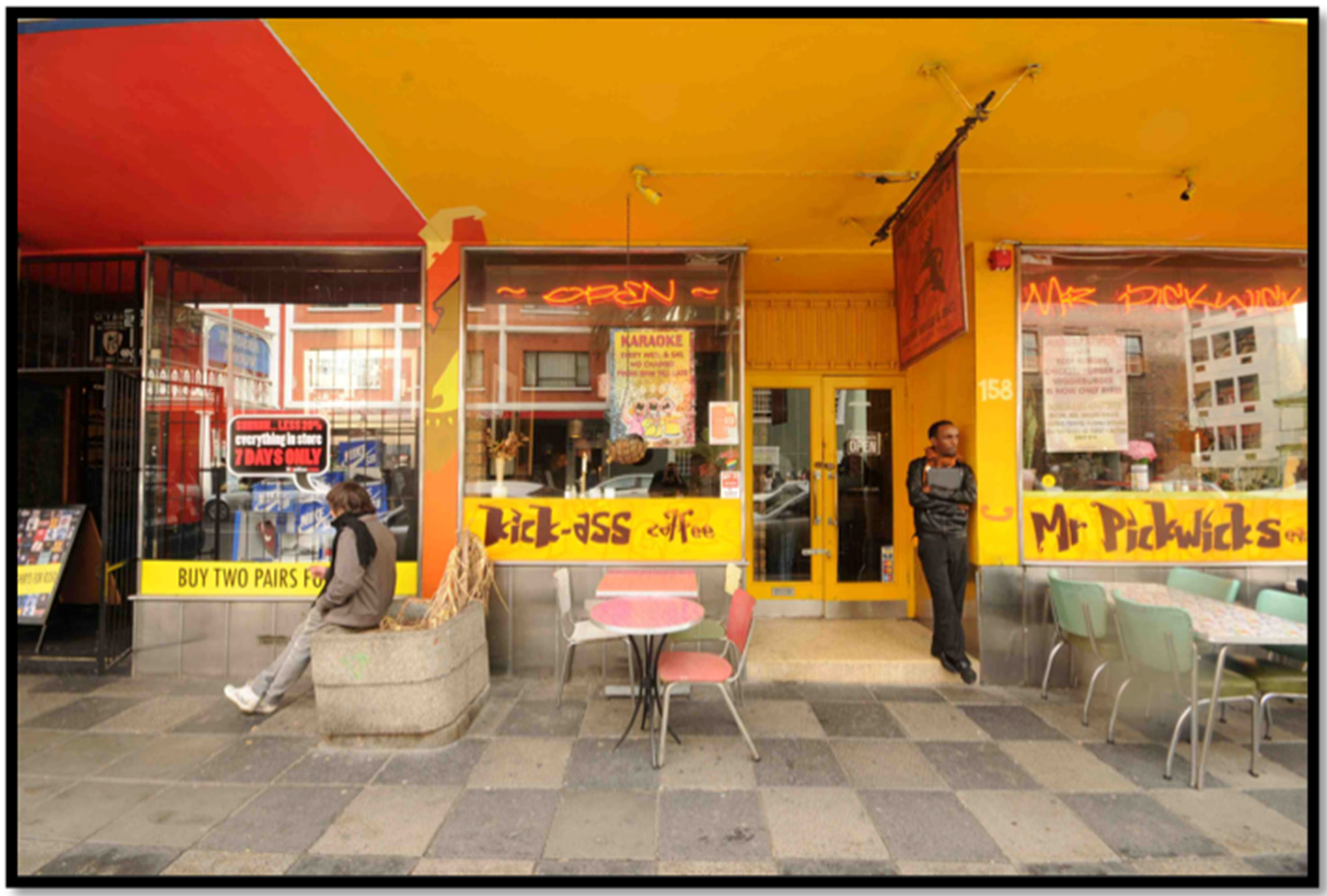

Figure 5.

Kick Ass on Long Street; interview with Ibrahim.

Figure 5.

Kick Ass on Long Street; interview with Ibrahim.

Figure 6.

Camps Bay interview with Kay.

Figure 6.

Camps Bay interview with Kay.

The District Six Museum Foundation drove the museum’s creation. The organization was founded in the late 1980s with the mission of preserving the memory of the district’s ex-residents in the belief that this could impede the rise of new forms of social oppression. One of the foundation’s first initiatives was in organizing the exhibition

Streets (1994); it sought to represent District Six through street signs that had once appeared in the neighborhood. Sandra Prosalendis, the director and founder of the museum, remembered when she was trying to gather the material for the first exhibitions. She explained that one idea about how to arrange the street signs was to put them back in their original places, but this idea was soon abandoned: “The landscape as it exists, as a space of absence, has its own message; it is a huge scar in the center of the city, and it speaks volumes” ([

32], p. 59). The museum’s foundation decided to display District Six’s urban area as it was before the demolitions, represented through a map created by several artists, including many ex-residents of the district. Prosalendis enthusiastically remembers when the exhibition first opened:

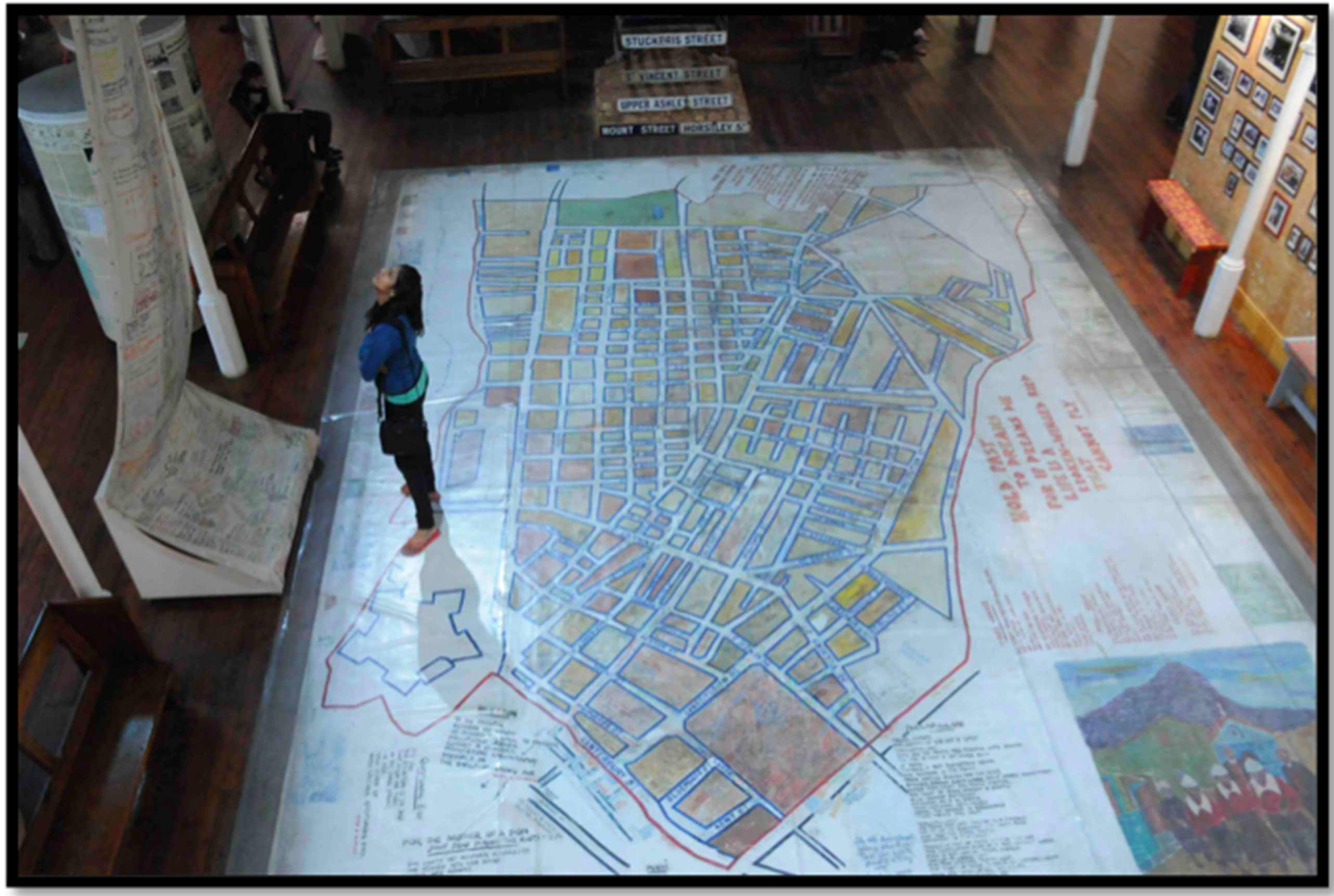

“From the minute the museum opened its door to the public, the ex-residents came and began to sign the map themselves, to write themselves back into the center of the city, to claim their history, and to claim the space. People marked bus stops, places where somebody sold peanuts, their old schools, and their homes.”.

Annie Coombes noted how the act of writing on the map and the other museum installations served to establish a direct dialog “without mediation” between the ex-residents and its visitors. By inscribing the district map with their thoughts, hopes, memories and dreams, District Six’s ex-residents sought to give voice to the district’s “dehumanized” places. The District Six map still covers almost the entire surface of the museum’s first floor and is used by the guides and museum attendants to describe the district’s history and various changes. The work in itself may look like a regular representation of the district, not unlike the anonymous topographic representations made by apartheid’s planners: “It is empty, devoid of life, able to be manipulated in the interests of those in authority” ([

33], p. 143). It shows the arrangement of the streets and their times that once defined the urban district. However, it takes on a special meaning when we walk on its surface. Walking on the map’s surface and beyond its borders, we can explore the different meanings that its residents attributed to its urban places. On the surface of the installation and those around it, there are sheets, molds and objects imprinted with the ex-residents’ writings. Visitors discover through the map the different meanings once attributed to the district. In this sense, the District Six map should not be seen only as a representation of a territory, but a territory itself that can be explored by crossing it. Charmaine McEachern noted that the District Sixers used exactly the same representation of the district during apartheid, which on the floor of the museum also began as an “empty” representation but took on a completely different meaning: “But their articulation of memory and walking provide for it a totally different meaning, one which resists the apartheid regime’s judgment, while at the same time criticizing its acts of destruction” ([

34], p. 505). Walking on the map allows us to discover that territory through the multiple meanings that its residents attributed to its spaces (

Figure 7). In this sense, walking on the map can be understood as “making place” in which the urban territory’s spaces take on meaning and substance. While it is true that by building the District Six map the ex-residents of the district recreate the urban territory by projecting onto it their thoughts, memories, hopes and desires, it is by moving on the map that we can discover them and bring them back to life.

Figure 7.

The District Six Museum walking map.

Figure 7.

The District Six Museum walking map.

The practice of walking can be seen as a place making through which the reader “appropriates” the territory through the meanings that its ex-residents attributed to it. The map does more than show the urban movement on the territory; it provokes new types of movement with which to explore the city. Reading the cartographic representation of the city and the practice of mapping as construction of the territory seem to coincide here. Taking inspiration from the District Six map and comparing it with Bateson’s epistemology of differences, we can envision a kind of ethnographic representation of the city that is both map and territory, and where its differences can be discovered through movement. Based on these premises, I started to imagine a cartographic representation of the city made up of different meanings that its inhabitants attribute to its urban places and in which the action of walking coincides with their interpretation. Like the District Six map, I would create a platform from which the city could be explored through the act of walking and where it could be discovered through its differences.

By combining the three constituent elements of the map, the map drawings, photographs and written texts, I sought to create a multiple perspective representation of the city. “Long Street” is made up of different forms of communication whereby the interactions create a hybrid, multi-dimensional representative form. The drawn maps, the written text and the visual texts are not meant here as an illustrating support for each other, but as complementary, integral parts of one expressive, interpretive flow. Inspired by the District Six map, I decided to think of my map as a walking map through which visitors could explore the street. Placing the territorial stages, vectors, writings and photographs on the platform (through paper representations and/or projections), I created a map-territory of the city. Walking on the map of Long Street, the city is discovered through the different perspectives of its residents. Walking on the map is intended as a way of connecting the different viewpoints. However, this connection is precarious and feeble. We can change the pathway for the interpretation of the city to take on a completely different meaning. In this sense, the representation of Cape Town is multiple, both because the city is articulated through different voices and different languages. The combination of different languages helps to reveal the object’s multi-dimensional nature. The map is multiple both in the object to which it refers and in the method that it uses.

5. Conclusions

In this article, I described the construction of an ethnographic map of Long Street representing post-apartheid Cape Town through the different viewpoints and voices of its inhabitants. The primary goal of this work was to observe the city through these multiple perspectives. My intent was to take different viewpoints on my object of study to create a crisis of belief in the viewer accustomed to reading an ethnographic account of the city as the only possible view of the city. In other words, I wanted to show that no map is ever the territory and that viewpoints and representations could be multiplied on the same territory, achieving different results. In order to expose the difference between my representation and the object of my study, I began to recognize the city as a subject. I had to listen to its different messages and voices without the fixation of having to bend them to a unified, all-encompassing view, whether holistic or reductionist.

For this purpose, a solution came from Bateson’s epistemology of difference which he continued from his earliest works to his last ideas on the process towards an ecology of mind. Taking this epistemological perspective, the city could no longer be considered an object of study, but rather an animate subject that expresses itself through different voices. Long Street regulars were not considered “inhabitant objects” of post-apartheid Cape Town, cut off from the historic flow dictated by grand narrativees and political upheavals. Rather, they are “inhabitant subjects” who can shape, invent, and create their stories. In this view, the city is read as the whole of the inventions and creations of the memories, reasoning, and imaginations of its inhabitants. Because I could no longer give a final, all-encompassing explanation of the city, stopped at offering a montage of its voices so that they can continue to express themselves freely.

I considered the activity of “montage” not as something which follows from observation, but as a fundamental part of observation. Putting together the data, reflecting on it, discovering “new juxtapositions” between the life stories I had listened to and the places I had visited could not be considered merely a stylistic exercise, as it was also an integral part of its hermeneutic activity. In this phase, I also found a convergence between Bateson’s ideas and the District Six map. George Marcus noted that, for Bateson, the method was expressed less in what was done in the field than in what was done with the data when behind the desk ([

18], p. 295). It is the preparation of the data, not its collection, that creates the method. In

Naven, the expression of contrasting methods is meant as the premise of their combination through montage. The explanation is therefore a collage of different perspectives. Likewise, it is through the assembly of different elements that the District Six map constructs its narrative to represent the district. We saw how the creation of the museum’s map (and the museum itself) was shaped by juxtaposing different elements of the district, such as street signs, objects and clothes that the ex-residents brought to bear witness. We saw how its reconstruction (through the assembly of these elements) can be seen as bringing the district back to life. The map is not, as such, a faithful replication of District Six, but a (political and poetic) remixing done through a new order suggested by its residents. District Six is represented in the museum as a district in fragments, reconstructed through its material and immaterial elements and waiting to be reconstructed through the visitor’s gaze. For Bateson, representation is not the attempt to replicate the object of study, but a process of deconstruction (destruction) and reconstruction of the data. We can see how the way that its ex-residents reconstruct District Six cannot be reduced to a mere exercise in style, but should be tied to a particular way of historically interpreting apartheid.

Annie Coombes noted that one of the District Six Museum’s distinctive traits is in replacing apartheid’s monologic perspective with a dizzying multitude of different voices. The homogeneous, internally cohesive apartheid ideology is replaced by the heterogeneous collection of its citizens’ thoughts, reflections, doubts, and hopes. We can follow the museum’s trajectory only by taking on the different viewpoints, thoughts, and memories of the ex-residents reconstructed through a series of installations, objects, and writings spread throughout the museum. Visiting the District Six Museum, visitors are invited to lose themselves amidst the viewpoints of the district’s ex-residents and to adopt a multiple, differentiated viewpoint. Every point of view of its inhabitants can be read and interpreted through the social and cultural product of its origin, but they do not converge. Apartheid’s monologic perspective is answered with a response of overlapping voices. Considering the map in particular, we can see how the act of walking coincides with discovering the district through its differences. It is movement on the “territory/map” that reveals the district through its polyphony. This map of Long Street does not seek to represent Cape Town through a single point of view; instead, it is an invitation to get lost in the different ways of observing the city. This invitation to walk on the map of Long Street is to be taken as an invitation to build one’s own interpretative pathway and one’s own map of the city.