Abstract

This article traces the transformation of hairworks in America during the mid-nineteenth-century. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin transformed the meaning of hair and hairworks in the American cultural imaginary by endowing Little Evangeline St. Clare’s hair with sacred, moralizing power. Likewise, after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln’s hair achieved nationwide, relic-like significance. The Abraham Lincoln Papers contains six hair requests; these letters demonstrate that the cultural meaning of Lincoln’s hair resembles the fictional power of Eva’s hair in Stowe’s novel. Analyzing this phenomena of relic-like hair modifies our understanding of the unprecedented sentimental reaction to Lincoln’s assassination and particularly the fascination with seeing and approaching the president’s body.

1. Introduction

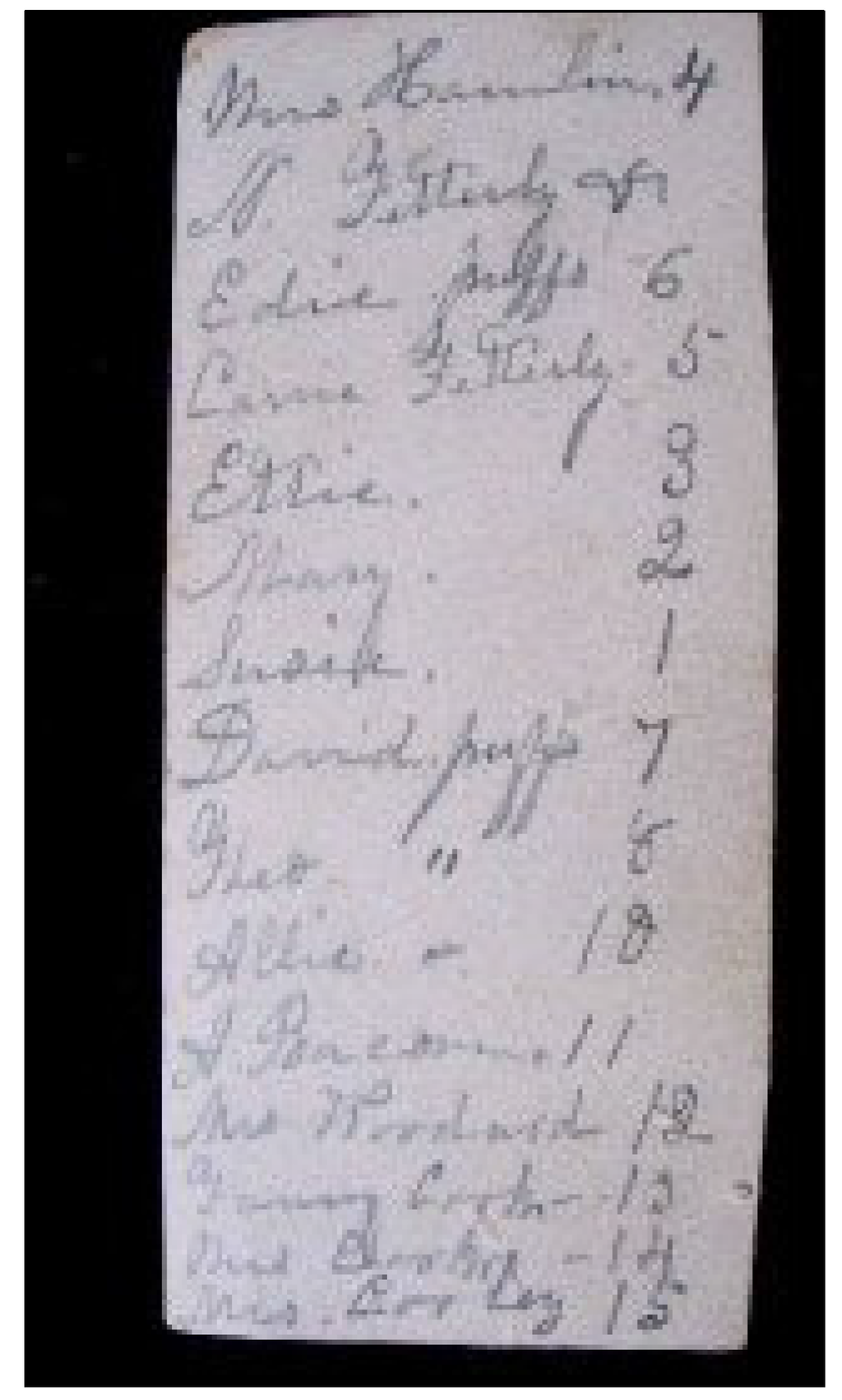

In Omaha, Nebraska, during the late nineteenth-century, a hair bouquet was crafted with the hair of fifteen individuals for a woman named Mrs. Hamlin (Figure 1). A number was attached to each lock of hair in the hairwork, corresponding to a numbered list of names (Figure 2). This hairwork was preserved with its list of names, passed along from mother to daughter, until it no longer functioned as an object of memory for the living1. Hairworks such as this were a nineteenth-century phenomena; like other fancy work, hairworks were a genteel art practiced exclusively by women. However, unlike lace-edged handkerchiefs or embroidered pillowcases, which could be made by genteel women and sold for a profit2, hairworks were intimate creations comprised of the hair of family or close friends, as demonstrated by the hair bouquet from Nebraska. Moreover, as the numbered hair samples and carefully preserved list of names demonstrate, Mrs. Hamlin’s hairwork as a whole was not as significant as the individual locks of hair that comprised it. Hairworks were not just aesthetic creations; they functioned as objects of remembrance and, eventually, as objects of mourning3.

Figure 1.

Hair Bouquet, Late-Nineteenth-Century, Omaha, Nebraska.

Figure 2.

List of names with Hair Bouquet.

This article traces the way Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, plays a role in transforming the meaning of hairworks as cultural artifacts in America. Stowe’s novel created new meaning for hair and hairworks in the American cultural imagination by endowing Little Evangeline St. Clare’s hair with sacred, moralizing power. Little Eva’s relic-like hair also transcends the boundaries of the sentimental novel tradition, which Stowe’s novel epitomizes.

Eleven years after Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published, this same transformation of the symbolic power of hair becomes apparent in the public demand for President Lincoln’s hair. After the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln’s hair achieved nationwide, relic-like significance. The Abraham Lincoln Papers preserved in the Library of Congress contain six hair requests from across the Union; these letters demonstrate that the cultural meaning of Lincoln’s hair resembles the fictional power of Eva’s hair in Stowe’s novel. Analyzing this phenomenon of relic-like hair modifies the scholarly interpretation of the national bereavement following Lincoln’s assassination.

This study looks at an extension of the traditional meaning of hairworks as it has been defined in recent scholarship, such as Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America by Helen Sheumaker. Hairworks were traditionally secular objects of sentimental exchange that European colonists brought to the New World ([3], pp. 1–5). In “Fashioning Death/Gendering Sentiment: Mourning Jewelry in Britain in the Eighteenth Century”, Arianne Fennetaux claims that mourning jewelry, including hairworks, functioned to transition early modern audiences away from Catholic rituals of mourning. In addition, between 1780 and 1800, mourning jewelry made another transition from functioning as a momento mori to a momento moveri: “a reminder of sentiments” ([4], p. 34). Thus, the Anglo-American practice of hairworks in the mid-nineteenth century was a firmly secular and sentimental practice4. However, Stowe pushes the boundaries on this sentimental trope with Little Eva’s relic-like hair. Later, Lincoln’s hair pushes similar boundaries at auctions during the Civil War.

2. Shaping the American Cultural Imagination: Stowe’s Blond Relic and the Patron Saint of Abolition in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin impacted the American cultural imagination when it was published in 1852, changing the way Americans perceived the institution of slavery5. One of the reasons her novel was so effective is that Stowe appropriated Victorian rhetorical strategies and reemployed them for her abolitionist message. Hair is among the Victorian tropes Stowe redefined in the American cultural imaginary.

Like a magic charm, hair emerges at important junctures in the lives and deaths of the characters in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, shaping their destinies. For example, Emmeline’s fate is determined by her tempting hair. Despite her best efforts to look plain, Emmeline is forced to expose her beautiful locks on the block in New Orleans ([8], pp. 347–48). The beauty of her hair, as well as her body, inspires Simon Legree to purchase her as a concubine ([8], pp. 350–51). Conversely, Eliza is able to control her destiny and secure her freedom by controlling her hair. By cutting off her hair and wearing men’s clothing, she disguises her identity and escapes to Canada with her husband and son ([8], p. 394). Elisabeth Gitter analyzes the treatment of hair in Victorian fiction; in the groundbreaking article “The Power of Women’s Hair in the Victorian Imagination”6, she states:

In painting and literature, as well as in their popular culture, they discovered in the image of women’s hair a variety of rich and complex meanings, ascribing to it powers both magical and symbolic…Silent, the larger-than-life woman who dominated the literature and art of that period used her hair to weave her discourse…([9], p. 936)

Thus, Stowe’s treatment of hair utilizes popular Victorian shorthand; hair is a symbol of femininity, both its power and its vulnerability.

The progressive blondness of Eva’s hair also reflects Victorian mythology about hair. Eva is introduced as a brunette ([8], p. 178), but she dies as a fair-haired angel ([8], p. 317). The term “golden” occurs with increasing frequency in descriptions of Eva just prior to her death ([8], pp. 296, 306, 317). According to Gitter, blond hair has a special mystique in Victorian literature; it is especially symbolic of feminine ideals; she states:

While women’s hair, particularly when it is golden, has always been a Western preoccupation, for the Victorians it became an obsession...When the powerful woman of the Victorian imagination was an angel, her shining hair was her aureole or bower; when she was demonic, it became a glittering snare, web, or noose.([9], p. 936)

Stowe’s increasingly blond Eva appeals to an established Victorian trope. In fact, the transformation of Eva’s hair corresponds to her transformation into a symbol or a saint.

However, Evangeline St. Clare’s blond locks exceed traditional Victorian tropes, both in fiction and in practice. Eva’s golden hair allows her to remain an active, angelic force on Earth after her death. When Eva realizes that her death is imminent, she has her hair cut and then she personally distributes the locks to the household slaves. Eva explains her gift, stating:

“…I want to give you something that, when you look at, you shall always remember me, I’m going to give all of you a curl of my hair; and when you look at it, think that I loved you and am gone to heaven, and that I want to see you all there”.([8], p. 264)7

This statement establishes her hair as a memento or even a token of love, like traditional Victorian gifts of hair, which functioned as sentimental objects to be viewed8. However, through the injunction to join her in heaven, Eva implies that her hair exceeds the typical passive role ascribed to tokens of hair in Victorian culture. Eva intends for her hair to actively inspire recipients to good, pious behavior; this is especially evident in her words to Topsy: “Yes, poor Topsy! to be sure, I will. There—every time you look at that, think that I love you, and wanted you to be a good girl!” ([8], p. 265)9.

During the later decades of the nineteenth-century in America, people often gave hair to friends and family for hairworks or hair jewelry. Like the daguerreotype of Eva and Augustine St. Clare, which Augustine gives to his wife Marie ([8], p. 195), hairworks and hair jewelry functioned as sentimental tokens, which could quickly shift from objects of memory to objects of mourning10. However, Eva’s mass distribution of hair in preparation for her impending death is a deviation from traditional nineteenth-century practices. In her article, “New England Funerals” (1894), Pamela McArthur Cole describes the practice of leaving instructions about mourning jewelry in wills ([12], pp. 220–21). Although someone might leave directions in their will regarding the cutting of locks for hairworks and mourning jewelry after death, hair was not distributed on a large scale in preparation for death.

Tom keeps a lock of Eva’s hair on the string with a coin from George Shelby ([8], p. 383). Stowe’s audience would have been familiar with this sort of practice; mourning jewelry commonly featured a locket containing the hair of the deceased. Cole states that this tradition began in the first decades of the nineteenth-century in New England, and it spread quickly ([12], pp. 223–24). However, in Tom’s keeping, Eva’s hair quickly shifts from a passive object of remembrance to an active relic with the power to effect the living. Like Dante’s Beatrice, Eva brings Tom a heavenly vision, which inspires him to continue resisting Simon Legree and remain true to his religious convictions ([8], pp. 400–1). The presence of Eva in Tom’s vision seems to reflect the presence of Eva’s hair in Tom’s life.

Eva’s hair becomes undeniably active when it confronts Simon Legree. When Legree first touches Eva’s hair, it almost seems to attack him like a snake: “hair which, like a living thing, twined itself round Legree’s fingers” ([8], p. 383). The apparent physical agency of the hair reflects real spiritual agency; the “curl of fair hair” ([8], p. 383) evokes the memory of a blond lock of hair his pious mother sent to him along with an offer of forgiveness ([8], pp. 383–84). There is explicit triangulation among Eva’s hair, Mrs. Legree’s hair, and the Eucharist; in Christ-like fashion, Legree’s mother sent a piece of her dying self to her son with an offer of redemption. Legree rejects his mother’s hair just as he rejects Christian salvation ([8], p. 383), but he cannot resist the relic-like power of Eva’s hair. It brings him a vision of hell that so unnerves him, he fails to rape Emmeline ([8], pp. 384–85). Moreover, the association of these locks of fair hair and the Eucharist resonates with descriptions of Stowe’s beliefs about the nature of this sacrament. According to Michael Gilmore in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the American renaissance: the sacramental aesthetic of Harriet Beecher Stowe,” Stowe had a “post-Calvinist” ([13], p. 63) perception of the Eucharist; she believed it was “neither merely symbolical nor the actual physical substance of the crucified God” ([13], p. 63). Likewise, Stowe allows the meaning of Eva’s hair to change and fluctuate throughout the novel as something that is more than just a symbol or object of remembrance11. Scholars, such as Arianne Fennetaux and Marcia Pointon, have suggested that hairworks and mourning jewelry did the cultural work of displacing Catholic mourning and religious rituals, anchoring hairworks in an increasingly secular and sentimental tradition12. Thus, Stowe’s creation of a relic-like use of hair particularly exceeds the sentimental tradition.

While the religious power vested in the hair supports the relic interpretation, associations between Eva St. Clare and the Catholic Saint Clare of Assisi cement this reading13. Although the staunchly Evangelical Beecher family wrote anti-Catholic tracts, Harriet Beecher Stowe was interested in aspects of Catholicism. According to Lori Merish in “Sentimental Consumption: Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Aesthetics of Middle-Class Ownership”, Stowe appropriated the “aestheticism of Roman Catholic religious culture and its redemptive, expressly feminine religious iconography” ([16], p. 1) in her third novel, The Minister’s Wooing. Merish explores the way Catholicism offered Stowe an extended metaphor for her sentimental materialism in her later work. However, this essay suggests that the allusions to Catholic hagiography in Uncle Tom’s Cabin exceed the sentimental tradition.

Stowe foregrounds the association between Eva and Catholic hagiography; both Tom and the reader are introduced to Eva as “Evangeline St. Clare” ([8], p. 176). The attributes of the Roman Catholic Saint Clare are reflected both in Eva’s angelic character and the power of her hair. Like the selfless Eva, Saint Clare took a vow of poverty. Like Eva, who gradually but painlessly succumbs to tuberculosis, Saint Clare was afflicted with poor health all her life, but her devotion to God made her impervious to pain. Finally, Saint Clare cuts off all her hair when she takes her vows and founds the order of nuns later known as “Poor Clares” or “Order of Poor Ladies”, just as Eva cuts her hair before she severs her ties with the world. Furthermore, the effect of Eva’s hair on the evil Legree parallels the effect of Saint Clare’s ailing body on the Viking hordes attempting to storm her convent. Saint Clare repulsed a Viking attack by appearing on the walls of her convent with the Eucharist ([15]). Similarly, Eva’s blond hair prevents Emmeline’s rape by terrifying Legree ([8], p. 388).

Thus, Stowe transforms the power of hair in the American cultural imaginary, infusing it with relic-like power. This power is specifically associated with combating the evils of slavery. Eva’s consumption is the result of her exposure to the blight of slavery not exposure to tuberculosis14, and her hair actively resists the embodiment of slavery, Simon Legree. According to Gitter, blond hair was especially symbolic of Nordic femininity in Victorian culture ([9], p. 936–37) and Stowe imposes the hope of emancipation onto this racialized symbol. In Race, Slavery, and Liberalism in Nineteenth-Century American Literature, Arthur Riss also recognizes the racial implications of Little Eva’s hair. According to Riss, the climax of Stowe’s message about race comes when Eva distributes her hair to the slaves. Stowe attempts to dematerialize racial markers by symbolically uniting them in this climactic sentimental scene, but instead this juxtaposition of African-American bodies and blond hair accentuates physical differences ([18], pp. 88–91)15. Thus, Eva is portrayed as the patron saint of emancipation; the blond relic she leaves behind attempts to fulfill the mission she fails to accomplish in life. Eva tells Tom: “I would die for them, Tom, if I could” ([8], p. 296). Eva’s death does not save anyone, but after her death, her hair continues to challenge the institution of slavery in the lives of individuals in Stowe’s novel. However, the message of abolition embedded in Eva’s hair is problematized by the racial nature of the symbol Stowe uses; Eva’s blond hair makes it possible for white Americans to appropriate ideas of abolition while ignoring the presence and stake of African Americans in this issue.

In Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction 1790–1860, Jane Tompkins claims that the sentimental novel, particularly Uncle Tom’s Cabin, has always been imbricated in the mythology of the domestic sphere: “the sentimental novelist elaborates a myth that gave women the central position of power and authority in the culture” ([19], p. 125). This mythology was augmented by the cult of the dying child ([19], p. 129). Little Eva’s hair exceeds both of these traditions; it is a relic that functions as an active force of terror that works outside the home, particularly in its effect on Simon Legree ([8], p. 388). As an active relic, Eva’s blond hair exceeds Stowe’s later amalgamations of Catholicism described by Merish. Furthermore, Eva’s hair is not an incidental object; it is necessary to the plot of Uncle Tom’s Cabin because it allows Stowe to confront human depravity that cannot simply be redeemed by motherly love or the sacrifice of a pure child.

3. Abraham Lincoln: The Making of an American Relic (1864)

After issuing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Abraham Lincoln received six requests for locks of his hair to be used in hairworks and sold at bazaars. These requests came from American citizens across the Union, none of whom knew Lincoln personally. Thus, these hair requests were an unprecedented phenomena in Victorian America; with these letters, American citizens assumed a level of intimacy with the president usually reserved for family and close friends. Gitter claims that a request for a lock of hair was “the most intimate and serious of demands” ([9], p. 943) in Victorian culture16. Moreover, Lincoln complied with at least two of these requests. Before the letter from Penfield and the letter from Spies and Champney were filed in Lincoln’s papers, someone (perhaps Lincoln’s secretary) wrote on each note that Lincoln donated an autographed note and a lock of hair to the sanitary fair17. Thus, these six requests and Lincoln’s response to them indicate that there was a unique understanding of the symbolic value of Lincoln’s body in American culture following the Emancipation Proclamation18.

The language of the requests merits further scrutiny. James Penfield and an unnamed representative of the Spies and Champney firm each write concise notes, under two-hundred words19. Both requests are written by businessmen on behalf of other artists. These notes foreground the commercial nature of all the hair requests; the statement that this hair will be sold to benefit a sanitarium is the only explanation included with the request. Penfield states, “the specimen would have substantial worth”, and Spies and Champney claim that it can be “turned to golden account at the coming Fair”20. This indicates that Lincoln’s hair had an artistic, and ultimately, a monetary value in American culture in 1864.

The explicitly commercial nature of these requests without further explanation highlights the unspoken acceptance of a dramatic break with the American tradition of hairworks. Hairworks were traditionally personal, private art. Although hairworks were made by both amateurs and professionals, they did not typically have a mass market value because they were unique works that had meaning for specific individuals21. According to Sheumaker, this was especially true for men, who could only receive hairworks from women with whom they shared a socially acceptable emotional relationship, such as a mother or spouse ([3], p. 125). However, these notes assume that Lincoln’s hair has nationwide significance and a good market value. Moreover, since these notes do not attempt to explain the unique value of Lincoln’s hair, the petitioners assume that this distinction is generally understood.

There is no record of other mid-nineteenth-century male American celebrities or politicians receiving similar requests22. Although Victorian fiction trafficked liberally in women’s hair, Cole’s documentation of New England funerary practices emphasize the intimate nature of hairworks and hair jewelry in New England culture ([12], pp. 222–23). Celebrity did not merit a request for hair in nineteenth-century America. Moreover, there is no indication that other presidents received similar requests in the documents preserved in the digital archives at the Library of Congress23.

The anonymous request Lincoln received from Philadelphia is longer than the notes from New York, but it also emphasizes the monetary worth of Lincoln’s hair. It states that the hair will be used in a “magnificent loyal National Hair Wreath; to be elegantly framed and placed as a free will offering—in the great Fair—to be sold for One thousand dollars…” [22]. Although the price set on the hair may be an over estimation or an example of hyperbole, this statement demonstrates the tremendous value of Lincoln’s hair. Moreover, it unites the price of the hair with its artistic and nationalistic cache, but it does not explain why Lincoln’s hair had this unique value in American culture.

The more elaborate notes of Sarah B. Howell and A St. Louis Lady explicitly articulate the unspoken assumptions of the other notes. A St. Louis Lady’s letter is the longest of the four preserved in the Abraham Lincoln Papers. Apparently aware of the bold nature of her request, the author alternately justifies herself with a sentimental appeal to the suffering soldiers and a scolding appeal to the president’s duty to the nation. In fact, her conclusion clearly implies that the president owes a lock of hair to the sanitarium in St. Louis: “It is earnestly hoped that, being made in all sincerity, and for so laudable a purpose, no refusal will be given” [23]. This note has a maternal tone; it almost seems to direct the president to send hair rather than request it. She emphasizes the necessity of an immediate delivery of hair, indicating that she is expecting the President to comply with her request. However, neither the imperative nature of the note nor its appeals to duty explain the reason for the change in Victorian precedents. This request does not explain why the nation feels an intimate connection with the president, it merely indicates the presence of that connection and that it is associated with patriotic duty and sentiment.

The note from Sarah B. Howell articulates the distinctly religious sentiment behind this unique cultural reverence for Lincoln’s body. Howell’s note is prayerful. She invokes “a nations benedictions [sic]” [24] and “a nation’s prayers”, implying appeals to God on Lincoln’s behalf. However, she also approaches Lincoln “with faith in our asking” [24]; this phrase resembles the language used in prayers, thus blurring the distinction between Lincoln and God. Lincoln’s identification with a beneficent God is more apparent in Howell’s closing: “…thy thanksgiving may come in many a prayer & blessing from a Soldier’s lips, as he breathes thy name—The blessing of him that is ready to perish be thine, is the prayer of A daughter of thy people [sic]” [24]. This explicitly sacred terminology is distinct to Howell, it is not featured in the other requests24. However, Howell’s religious reverence can explain why Americans felt a unique affinity with his physical body: he was more than an individual man, he was a relic-like national symbol. Moreover, Howell implicitly unites her request for a lock of hair with the idea that Lincoln has physically sacrificed himself for the nation: “Thee has given thyself body and soul so entirely to thy people, that we presume to ask almost any favor at thy hand without dread of a refusal…” ([24]). Thus, Howell portrays Lincoln as a living martyr for America; as a martyr, a lock of his hair would be a relic25.

4. Patron Saint of Abolition: Little Eva and President Lincoln

Although neither Howell nor any of the individuals requesting locks of hair refer to the abolition of slavery, all of the requests are from 1864, after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. In “The Emancipation Proclamation: The Decision and the Writing”, John Franklin discusses the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation changed the meaning of Lincoln and the Civil War ([25], p. 198); after it was issued in 1863, the ideological basis for the war shifted from the preservation of the Union to abolition ([25], p. 204), and the public image of Lincoln shifted along with it26. In 1864, when Lincoln received four requests for locks of his hair to be used in hairworks and sold to benefit sanitariums across the Union, the Civil War had already been raging for three years. What makes 1864 distinct is the ideological shift of the war and corresponding change in national perceptions of Lincoln. Thus, the requests for locks of Lincoln’s hair seem to indicate that, like Little Eva in Stowe’s novel, Abraham Lincoln was a martyr or patron saint for abolition in the American cultural imaginary. While there are numerous examples of suffering African-American bodies in sentimental abolitionist fiction, Little Eva sets the precedent for martyred white bodies. Furthermore, in March of 1864, Lincoln’s manuscript of the Emancipation Proclamation was also sold for $1000 to benefit New York sanitariums ([25], p. 201)27. The value of Lincoln’s handwritten copy of the Emancipation Proclamation demonstrates the personal, physical relationship between Lincoln and this document in American culture.

Thus, the artistic and monetary value of Lincoln’s hair parallels the Little Eva paraphernalia generated by the popularity of Stowe’s novel. According to Jo-Ann Morgan’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture, Eva was not only the darling of the novel for American audiences, she had huge selling power in the visual arts ([14], p. 50). Moreover, the national acclaim of Uncle Tom’s Cabin explains the nationwide nature of the hair requests. The popularity of Lincoln’s hair was not a trend that began in one location and spread across the Union, these requests arrive from New York City, New York, Trenton, New Jersey, and St. Louis, Missouri relatively simultaneously. Moreover, the first five hair requests preserved in the Abraham Lincoln Papers do not reference a general trend; the notes from Philadelphia, Trenton, and St. Louis do not appeal to Lincoln’s previous gift of hair to the sanitarium in New York City. Only the last hair request from the Perkins Sanitarium, posted in August 1864, references other Sanitary fairs where locks of Lincoln’s hair were sold: “The loyal citizens of Perkins and vicinity have determined to hold a Sanitary Fair similar to those which have been held with such unprecedented success in several of our western and some eastern cities…” [26]. Since the majority of requests for Lincoln’s hair are not in conversation with each other, they must be in conversation with a different cultural trend. The death scene of Little Eva in Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a likely common source of these requests28. The relic-like nature of Eva’s blond locks could inspire the relic-like value of Lincoln’s hair after the Emancipation Proclamation. Like Little Eva, Lincoln’s proclamation made him the white embodiment of the abolitionist desires of the nation. The popularity of Little Eva’s death scene was kept alive in dramatizations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. These dramas also kept this novel in the forefront of the American cultural imagination ([14], p. 51).

Race seems to be a factor in Lincoln’s symbolic worth29. The nation rallies around and deifies a white symbol of abolition, ignoring the role and presence of African Americans in the issue of emancipation. The use of hair as a white symbol of abolition, first through Little Eva and then through Lincoln, is problematic because it allows Americans to ignore the issue of African American slavery while still utilizing the concept of a morally righteous, ideological war. This silence is overt in the sale of Lincoln’s manuscript of the Emancipation Proclamation ([25], p. 204) and lurking beneath the surface of the hair requests Lincoln received throughout 1864.

In Sentimental Materialism, Lori Merish identifies the interrelationship between the material representations of sentimental culture and the sentimental novel in the United States. Merish anchors these interlaced motifs in the middle-class home; she claims that the sentimental novel generates a “realm of domesticity as the sphere of fulfillment and plentitude” ([28], p. 137). However, both Lincoln’s hair requests and Eva’s relic-like hair exceeds these secular and sentimental boundaries; they are objects that work outside the home. Stowe gives Eva’s hair agency because her plot exceeds the traditional boundaries of the sentimental tradition; it demands a new kind of power that exceeds the cult of mother love or the dying angel, which dominates sentimental fiction. Through the potential relationship between Lincoln’s hair and Eva, the distinctive mythology within Stowe’s novel generates a national, public symbol.

5. Changing Perspectives on the Cultural Meaning of Lincoln’s Funeral Rituals

The significance of the hair requests Lincoln received modifies the current interpretation of the national bereavement following the President’s assassination. In “Mourning and the Making of a Sacred Symbol: Durkheim and the Lincoln Assassination”, Barry Schwartz argues that Lincoln is a unique example of Durkheim’s theory of the making of the sacred through ritual. Schwartz states:

Embodying society’s cherished ideals, mundane objects and undistinguished people thus come to be respected or revered. I show, however, how Lincoln became an object of intense mourning at a time when most people held him in mixed or low regard. It becomes apparent that Lincoln’s case is one of many in which positive rituals are enacted independently of negative beliefs about their object.([29], p. 344)

Schwartz convincingly demonstrates the nationwide fascination with approaching Lincoln’s physical body and the national affirmation of this communal mourning ([29], pp. 346–49).

However, Schwartz predicates his argument on the idea that this reverence for Lincoln spontaneously appeared after his death; he states:

After Lincoln’s official funeral was concluded at the Capitol, his body was removed to the train station in the presence of a massive crowd…There was no reason to believe this meticulously contrived procession would spontaneously turn into the most striking state ritual that Americans had ever witnessed or would ever witness again.([29], p. 347)

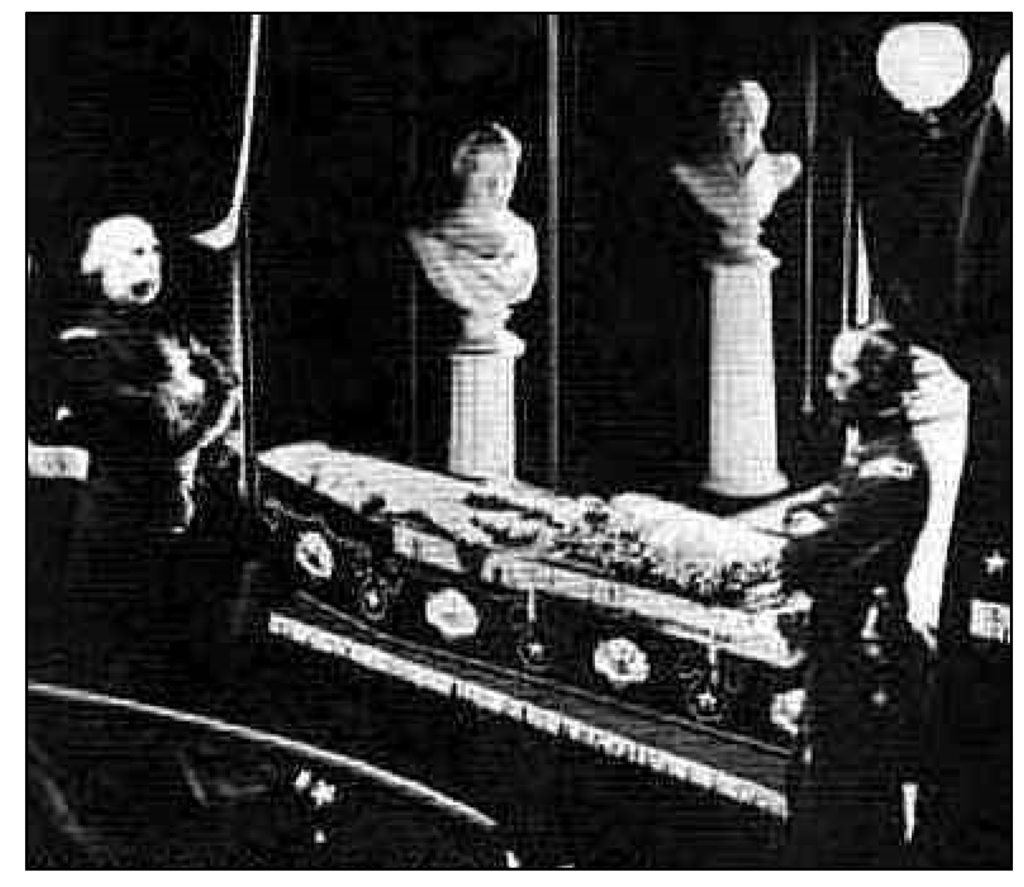

Schwartz does not account for the symbolic value of Lincoln’s physical body before his assassination. Moreover, Schwartz’s theory has been perpetuated in the assumptions of recent scholars like Sean Wilentz30 and Thomas Craughwell. In Stealing Lincoln’s Body, Craughwell specifically marks Lincoln’s death at “7:22 on the morning of April 15, 1865” ([31], p. 1) as the moment when Lincoln was transformed from a man into a symbol (Figure 3). Unlike Craughwell, Schwartz claims it was the communal mourning rituals that began on April 19 that vaulted Lincoln into sainthood. However, the six hair requests Lincoln received in 1864 demonstrate that the President had already achieved an unprecedented symbolic status in American culture. The fact that there was a paying public willing to purchase hairworks made with Lincoln’s hair demonstrate that this exalted status was widespread. Thus, the sanctifying communal ritual Schwartz identifies solely in Lincoln’s death was already appearing in his life, especially after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued.

Figure 3.

Photograph of Abraham Lincoln’s open casket lying in state, April 1865.

Moreover, Secretary of State Edward Stanton’s decision to embalm Lincoln on April 15th conflicts with Schwartz’s claim. According to the records of the Brown and Alexander funeral home, embalming Lincoln was not a foregone conclusion ([32], p. 1)31. Preparing Lincoln for an open casket viewing and then keeping his body presentable throughout the fifteen-day funeral procession taxed mortuary practices to the limit ([32], p. 1)32. Thus, Stanton’s arrangements were deliberate, not merely expected rituals. In fact, in 1862, while there were thirteen undertakers, there were no embalmers in Washington D.C. according to Craughwell ([31], pp. 5–6). Although it may be true that no one could have predicted the public response to Lincoln’s funerary rituals ([30], p. 347), Stanton must have anticipated not only a significant response, but also the public need to both see and approach the late president’s body33.

The embalming and prolonged funeral procession of Lincoln allowed the American public access to the body in a manner usually reserved for family and close friends. Victorian rules about proximity to the body were bent as hundreds of thousands of Americans attempted to view Lincoln in his open casket ([31], p. 18). This resonates with the sentiment that inspired requests for Lincoln’s hair during his presidency. Like his hair, his physical body had national significance, but scholars have failed to recognize this continuity and its significance. Lincoln’s death alone did not transform him into a national symbol: his unique status began after the Emancipation Proclamation and reflects the cultural work of Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

6. Conclusions: Reinvesting in the Cultural Imaginary

In his introduction to a century of scholarship on Abraham Lincoln, Wilentz states: “As emancipator, commander-in-chief, orator, and martyr, Lincoln—or the image of Lincoln—stands for the nation’s highest values” ([30], p. xi). Lincoln was an idea as well as a man; his image has become the embodiment of America’s sacred freedoms in the cultural imagination. Since Lincoln’s first presidential campaign in 1860, his image and distinctive face had been associated with his politics34. However, after the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln embodied ideals that exceeded politics. While Lincoln’s status as a white symbol of abolition maybe problematic, requests for his hair demonstrate the relic-like reverence for Lincoln that permeated American culture even before his death immortalized him as an American martyr.

The relationship between Lincoln’s relic-like status and Uncle Tom’s Cabin also demonstrates how Stowe’s novel extends the limits of the sentimental tradition that it epitomizes. Stowe pushes beyond religion of motherly love and even the social and political activism associated with the sentimental novel. Through the relic-like hair of Eva, which becomes an active force outside the domestic sphere, Stowe engages in a unique kind of myth-making. Although Eva’s sacrificial death epitomizes the sentimental tradition, her active hair does not merely offer salvation, it confronts and even prevents evil by protecting Emmeline ([8], p. 388). Moreover, her myth seems to materialize in the treatment of Lincoln’s hair.

Stowe provides the national imagination with an object that symbolizes the sort of power necessary to confront the problem of slavery. In fact, the blond relic is the only white body to physically confront the darkness of slavery. It allows the other white characters and Stowe’s white audience to avoid that confrontation by making it symbolically through Eva’s hair. It also provides a way to ignore or circumvent the real body involved in slavery.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Tom Cooper for the use of his beautiful hairwork in this study and the images used here. Additionally, I would like to thank the staff and curators at Leila’s Hair Museum for their help in tracking down specific examples of hair works.

Appendix

Transcripts from three of the six requests for a lock of Abraham Lincoln’s hair. The spelling and grammar here reflect the original manuscripts [34].

James Penfield to Abraham Lincoln, Saturday, February 13, 1864 (Requests lock of hair to be used in artwork sold at Brooklyn Sanitary Fair)

Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois.

From James Penfield to Abraham Lincoln, February 13, 1864

Bridgeport Feb 13th 1864.

Sir—At the Sanitary Fair to be held in Brooklyn the 22nd inst [sic] there is to be a New England department for which, among other things in the artistic line, Specimens in Hair work are solicited.

Mrs Penfield wishes to contribute in that line, and to make a long story short, she wishes a lock of the Presidents hair, also of Mrs Lincoln’s—then the specimen would have substantial worth. As no other Hair would be used in connection, pretty good locks & long, would be needed.

An autograph letter from President Lincoln certifying to the genuineness &c would be invaluable.1

Resptly Yours

Jas Penfield

Bridgeport Conn.

[Note 1 Lincoln donated an autograph note to the New England department of the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair. See Collected Works, VII, 220.] [35].

Spies & Champney to Abraham Lincoln, Tuesday, January 12, 1864 (Request lock of Lincoln’s hair for sale at a Sanitary Fair)

Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois.

From Spies & Champney to Abraham Lincoln, January 12, 1864

Respected Sir

we are now engaged in getting up a Fair in our goodly city of Churches for the benefit of the sanitary Commission whose good deeds you are probably better acquainted with than we are and it suggested itself to us that if you would allow us we could work up a lock of your hair in some national device which if accompanied by only a line or two from your own hand could be turned to golden account at the coming Fair and you thus be the means of easing the pain of many a one of our brave suffering soldier boys if you feel favorably disposed please send us by mail as large a lock as you can well spare and if you would accept it we should be pleased to make a duplicate of the device and send it to you for presentation to Mrs Lincoln who would probably value your hair more than you would yourself--1

we are with all due respect

Your obt sevts and

loyal americans

Spies & Champney

133 Fulton St.

Brooklyn N Y.--

Brooklyn Jany. 12/64.

[Note 1 Lincoln donated an autograph note to the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair. See Collected Works, VII, 220.] [20].

Sarah B. Howell to Abraham Lincoln, Monday, June 06, 1864 (Requests lock of Lincoln’s hair)

Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois.

From Sarah B. Howell to Abraham Lincoln, June 6, 1864

Trenton June 6th 1864.

Burdened as thee is by the weight of a nations cares, her woes felt in every heart-throb as thine own, my somewhat trifling appeal may reach thee inopportunely.

Thee has given thyself body and soul so entirely to thy people, that we presume to ask almost any favor at thy hand without dread of a refusal, but with faith in our asking: for no other President has come so near our hearts, no other one whose name falls so like music on the private ear, a name crowned with a nations benedictions, a name always remembered in a nation’s prayers. A lock of hair that now shades the brow that has done the planning and thinking for this great nation in her hour of peril—is the boon I crave—to be woven into a bouquêt for the ‘Sanitary Fair’; And as I would not set a marketable value upon they locks, every one may have the privilege of contributing to the purchase to be returned to thee—Please let those who may attend to it procure such hair as thee would value to complete the boquêt or wreath, either that of thy own family or members of the Cabinet &c having each marked with the name of the person—

If I have been rash in the request may not my motives plead my apology—Thy missing locks will be replaced by the faithful historian who shall twine a more enduring chaplet than the one my fingers would weave: and thy thanksgiving may come in many a prayer & blessing from a Soldier's lips, as he breathes thy name—

The blessing of him that is ready to perish be thine, is the prayer of

A daughter of thy people

Should thee listen to my request, my address is

Miss. Sarah B. Howell

Care of Joseph Howell

No. 66. Warren St. Trenton

N. J. [24].

References and Notes

- Victorian Hairwork Society Webpage. “Hamlin Hairwreath.” Available online: http://www.hairworksociety.org/ (accessed on 7 August 2008).

- Frank K. Prochaska. Women and Philanthropy in Nineteenth-Century England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Helen Sheumaker. Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Arianne Fennetaux. “Fashioning Death/Gendering Sentiment: Mourning Jewelry in Britain in the Eighteenth Century.” In Women and the Material Culture of Death. Edited by Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin. Burlington: Ashgate, 2013, pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Michell Iwen. “Reading Material Culture: British Women’s Postion and the Death Trade in the Long Eighteenth Century.” In Women and the Material Culture of Death. Edited by Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin. Burlington: Ashgate, 2013, pp. 239–50. [Google Scholar]

- Teresa Barnett. Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ronald Walters. “Harriet Beecher Stowe and the American Reform Tradition.” In The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 171–89. [Google Scholar]

- Harriet Beecher Stowe. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. 1852. Edited by Elizabeth Ammons. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elisabeth Gitter. “The Power of Women’s Hair in the Victorian Imagination.” Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 99 (1984): 936–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funeral museum. “Bejeweled Bereavement.” Available online: http://www.funeralmuseum.org (accessed on 7 August 2008).

- Carolyn Karcher. “Stowe and the Literature of Social Change.” In The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 203–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pamela McArthur Cole. “New England Funerals.” The Journal of American Folklore 7 (1894): 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael Gilmore. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the American Renaissance: The Sacramental Aesthetic of Harriet Beecher Stowe.” In The Cambridge Companion to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jo-Ann Morgan. Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- New Catholic Encyclopedia. “Saint Clare of Assisi.” New Catholic Encyclopedia. 2007. Available online: http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04004a.htm (accessed on 10 March 2009).

- Lori Merish. “Sentimental Consumption: Harriet Beecher Stowe and the Aesthetics of Middle-Class Consumption.” American Literary History 8 (1996): 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizabeth Ammons. “Heroines in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” American Literature 49 (1977): 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur Riss. Race, Slavery, and Liberalism in Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jane Tompkins. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790–1860. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. “Spies & Champney to Abraham Lincoln, Tuesday, January 12, 1864 (Request lock of Lincoln’s hair for sale at a Sanitary Fair).” In American Memory. Available online: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d2940200)) (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- C. Jeanenne Bell. Collector’s Encyclopedia of Hairwork Jewelry: Identification and Values. Paducah: Collector Books, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Library of Congress. “Philadelphia to Abraham Lincoln, 1864 (Request lock of Lincoln’s hair for sale at a Sanitary Fair).” In American Memory. http://memory.loc.gov/ (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- The Library of Congress. “‘A St. Louis Lady’ to Abraham Lincoln, 1864 (Request lock of Lincoln’s hair for sale at a Sanitary Fair).” In American Memory. Available online: http://memory.loc.gov/ (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- Sarah Howell. “Sarah B. Howell to Abraham Lincoln, Monday, June 06, 1864 (Requests lock of Lincoln’s hair).” In American Memory. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d3356500)) (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- John Franklin. “The Emancipation Proclamation: The Decision and the Writing.” In The Best American History Essays on Lincoln. New York: Palmgrave Macmillan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- The Library of Congress. “Perkins Sanitarium to Abraham Lincoln, August 1864 (Request lock of Lincoln’s hair for sale at a Sanitary Fair).” In American Memory. http://memory.loc.gov/ (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- Ashley Byock. “Domesticating Death in the Sentimental Republic: Commemoration and Mourning in US Civil War Nurses’ Memoirs.” In Women and the Material Culture of Death. Edited by Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin. Burlington: Ashgate, 2013, pp. 157–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lori Merish. Sentimental Materialism: Gender, Commodity Culture, and Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barry Schwartz. “Mourning and the Making of a Sacred Symbol: Durkheim and the Lincoln Assassination.” Social Forces 70 (1991): 343–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sean Wilentz, ed. The Best American History Essays on Lincoln. New York: Palmgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Thomas Craughwell. Stealing Lincoln’s Body. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Funeral museum. “Embalming of President Lincoln.” Museum of Funeral Customs. Available online: http://www.funeralmuseum.org (accessed on 7 August 2008).

- Herbert Mitgang. “The Art of Lincoln.” American Art Journal 2 (1970): 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Abraham Lincoln Papers and the Library of Congress. ” Available online: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/alhtml/malhome.html (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers and the Library of Congress. “Penfield to Abraham Lincoln, February, 1864 (Request lock of Lincoln’s hair for sale at a Sanitary Fair).” In American Memory. Available online: http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d3050600)) (accessed on 17 January 2009).

- 1The hair bouquet was finally inherited by Mrs. Hamlin’s granddaughter, who sold it to a collector. The granddaughter guessed that this hairwork was created by Fanny Cooper, a close friend of Mrs. Hamlin, but there is no documentation to indicate the name of the artist [1].

- 2According to F. K. Prochaska, the sale of fancywork became an acceptable practice in Great Britain during the early nineteenth-century, and it quickly spread to America ([2], pp. 49–50, 53).

- 3Helen Sheumaker makes a similar claim about the function of hairworks in America ([3], pp. xiv–xv).

- 4Sheumaker’s work has attained broad scholarly consensus in its characterization of hairworks as secular, sentimental objects, as well as its positioning of hairworks in “moral market culture” ([3], p. 5). Sheumaker describes the cultural stakes involved in the purchase of hairworks: “one’s successful integration of the emotional attitude of sentiment through the action of selecting and purchasing a good on the market” ([3], p. 5). Michelle Iwen reiterates the conjunction of sentimentalism and consumerism in hairworks ([5], pp. 246–47). Iwen also reinforces the secular and romantic meaning of these artifacts; demonstrating their distinction from religious relics of an earlier era ([5], p. 247). Teresa Barnett has recently challenged this view. Barnett suggests that modern scholars have missed “a sensibility in which the relic could have meaning” ([6], p. 3) in America. However, Stowe’s deliberate creation of Eva’s relic-like hair seems to exceed the examples in Barnett’s study because Stowe was deliberately moving beyond the limits of sentimentalism. Furthermore, despite the title, Barnett’s definition of the American relic seems to be relatively secular. For example, Reverend Bentley’s collection of early American memorabilia discussed in the first chapter has no overt religious significance ([6], pp. 13–15). By contrast, Stowe’s treatment of hair is explicitly spiritual in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

- 5Ronald Walters seems to articulate the scholarly consensus when he states that Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin not only had a “substantial readership” ([7], p. 172) but also the ability “to bring a controversial message to a large audience in a powerful and compelling fashion” ([7], p. 172). Whether or not Stowe’s fiction actually changed society, her works were recognized as influential reform literature in her lifetime ([7], pp. 171–73).

- 6For two decades, Gitter’s article has been a central text in the scholarly conversation about the cultural work of hair in the nineteenth-century. Various scholars have utilized her arguments without displacing her foundational article; for example, Joann Pitman quotes Gitter extensively in her recent book Blondes.

- 7Eva’s words recall the language of Christ as he institutes the Last Supper in the Gospel of Luke: “This is my body given for you; do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19). The relationship between Eva’s hair and the Eucharist will be discussed at length later in the paper.

- 8The Museum of Funeral Customs articulates the importance of spectacle in Victorian mourning rituals; the primary role of hair and jewelry in the Victorian era was the public display of bereavement: “The Victorian Era (1837–1901), by contrast, turned the entire ritual of mourning into a public display, and the jewelry changed accordingly, becoming larger, heavier, and more obvious.” ([10], p. 1) Scholars such as Sheumaker have established the sentimental meaning of hairworks in American culture ([3], pp. 1–3).

- 9Carolyn Karcher lauds the religious fervor of Little Eva as a powerful rhetorical strategy that had a potentially universal humanistic appeal: “Stowe’s crowning achievement lay in infusing Uncle Tom’s Cabin with the religious fervor that gave the novel its irresistible power. By wrapping her anti-slavery message in evangelical garb, Stowe succeeded in reaching ‘a much larger class of readers…’ as Lydia Maria Child remarked wryly. Yet readers of other religious persuasions—Unitarians, Quakers, Catholics, and even freethinkers and devotees of non-western faiths—found themselves no less moved by Uncle Tom’s and Eva’s sacrificial deaths and the core belief they symbolized: that men and women willing to lay down their lives for a cause could transform their fellows and ultimately the world” ([11], p. 208).

- 10Also see Sheumaker ([3], pp. 1–4).

- 11Religious connotations of the blond Eva were most popular in visual culture, according to Jo-Ann Morgan ([14], p. 11). Visual reproductions, including playbills, paintings, and illustration reinforce religious nature of Eva’s blond hair in the cultural imagination.

- 12See Fennetaux ([4], pp. 33–35).

- 13This essay utilizes the New Catholic Encyclopedia for a description of the life and acts of Saint Clare of Assisi [15].

- 14When Eva hears her father and Miss Ophelia discussing slavery, she bursts into tears and tells him “these things sink into my heart” ([8], p. 258); even after she stops crying her face continues to “twitch” ([8], p. 258). This twitching could be interpreted as evidence that Eva’s body is physically afflicted by the institution of slavery. Soon after this episode, Tom notices Eva’s increasing weakness ([8], p. 282)—slavery is killing her. Elizabeth Ammons states: “The child identifies with the slaves’ misery, telling Tom finally: ‘…I would die for them, Tom, if I could’. On the figurative level—the only level on which Eva makes sense—she gets her wish. Stowe contrives her death to demonstrate that there is no life for a pure, Christ-like spirit in the corrupt plantation economy the book attacks” ([17], pp. 168–69).

- 15Sheumaker claims that hairworks were distinctly Euro-American cultural artifacts: “Many non-European cultures shunned, and still avoid, the decorative use of human hair that has been detached from the head and is intended for a use other than augmenting one’s remaining hair. Most Native American groups most African Americans, and Asian Americans had, and have, cultural and religious prohibitions against using human hair in the memorial fashion of Euro-American ornamental hairwork” ([3], p. xiii). Thus, the very use of a hairwork in Stowe’s novel is ethnically distinctive.

- 16Gitter uses the courtship correspondence of the Brownings to demonstrate the intensely intimate nature of a request for hair: “Robert Browning asks for ‘what I have always dared to think I would ask you for…one day! Give me…who never dreamed of being worth such a gift…give me so much of you—all precious that you are—as may be given in a lock of your hair’…(Elizabeth Barrett replies), ‘I never gave away what you ask me to give you, to a human being, except my nearest relatives and once or twice or thrice to female friends…’” ([9], p. 943).

- 17On 12 January 1864, Spies and Champney request a lock of hair for the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair. James Penfield also writes regarding a Sanitary Fair to be held in Brooklyn. Although it is likely the same fair, that fact is unclear in the wording of the requests. They seem to be referring to two different events held in Brooklyn, one organized by the New England department (Penfield) and one organized by an affiliation of Churches [20]. If it is the same fair, the notes on the bottom of each of these requests may indicate that Lincoln donated a single lock of hair to the Brooklyn Sanitary Fair rather than two locks of hair.

- 18This study modifies and builds upon the idea of the American relic that Teresa Barnett develops in Sacred Relics: Pieces of the Past in Nineteenth-Century America. Barnett demonstrates the proliferation of objects that offer a specific connection with the past. However, this connection does not seem to be particularly religious or spiritual in nature (such as the collection of John Fanning Watson) ([6], pp. 16–18). The hair requests here, made during Lincoln’s life, are also distinct from the material distributed after his assassination, which Barnett mentions in her Introduction ([6], pp. 6–7).

- 19See the appendix for all the transcripts from the hair requests. Three of the six are available.

- 20This poetic phrase in the midst of a prosaic note seems to be alluding to the Victorian mythology about blond hair.

- 21See the discussion of Mrs. Hamlin’s hairwork [1]. Sheumaker references similar private examples. Even hairworks commissioned by professional jewelers and hairworkers are valued because of the specific identity of the individual from whom the hair came ([3], pp. ix–x).

- 22In the Collector’s Encyclopedia of Hairwork Jewelry, C. Jeanenne Bell identifies a few celebrated British women who received hair requests early in the century, prior to the Victorian Era ([21], pp. 8–10). American author Fanny Fern also refers to hair requests in the autobiographical novel published in the 1850s, Ruth Hall. In the novel, Fern describes the intimate, imagined connection that developed between author Ruth Hall and her readers. This assumption of intimacy resulted in a massive amount of fan mail, which includes marriage proposals from strangers and hair requests. However, it is difficult to determine if Fanny Fern (Sara Willis) actually received hair requests. Furthermore, all these examples involve women with whom the public developed an imagined intimacy; there is no record of any men receiving similar requests.

- 23Sheumaker claims that the world of sentimental hairworks was a “minefield of possible missteps for many men” ([3], p. 136). Thus, it is unlikely that men, especially men with carefully crafted public personas, would ever offer their hair for a hairwork to be sold at a public auction.

- 24In the request from Philadelphia, the proposed hairwreath is described as a “free will offering”, a term that appears frequently in the Bible (see Exodus 36:3), but this note lacks the religious sentiment of Howell’s hair request.

- 25After Lincoln’s death, more than one individual referred to mementos from the president as “sacred relics” ([6], p. 6). However, this study analyzes hair requests that Lincoln received before his “sanctifying” death.

- 26Franklin makes it clear that the Emancipation Proclamation was not met with unanimous acclaim ([25], p. 204). Radical republicans were disappointed with its limitations while other politicians feared that it would provoke the loyal border states to join the confederacy ([25], pp. 200–1). Despite negative reactions from both the right and the left, Franklin still claims that this proclamation impacted the national understanding of the Civil War ([25], p. 204).

- 27The price paid for Lincoln’s manuscript validates the Philadelphia request, which claims the hairwreath made with the President’s hair would be sold for $1000.

- 28Ashley Byock directly links the conceptualization of soldiers’ deaths in nurses’ memoirs with “the structures and iconography of antebellum sentimental narratives like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin” ([27], p. 160). However, these narratives are primarily published after the hair requests in the Lincoln archives, and they do not include the taking of hair or other relics from the dead. Rather, sentimental novels offer nurses and the American public a way to view and understand death.

- 29The problematic racialized meaning of Lincoln’s body is accentuated by the practice of hairworks, which Sheumaker identifies as a distinctly Euro-American art form. According to Sheumaker, this exclusion exceeds market forces that ignore anyone outside the white middle-class ([3], pp. 2–3). Sheumaker claims that religious and cultural taboos made the art of hairworking unacceptable for African Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans in the United States ([3], p. xiii).

- 30Wilentz clearly identifies Lincoln’s assassination as the action that immortalized him in American culture ([30], p. xi).

- 31The embalming of Lincoln’s body changed the American attitude towards embalming. According to the Museum of Funeral Customs, the funeral journey “introduced embalming to a broad audience and popularized the procedure” ([32], p. 1).

- 32Prior to Lincoln’s assassination, no other American was laid in state. The cities where Lincoln lay in state are: Washington, DC; Baltimore, MD; Harrisburg, PA; Philadelphia, PA, New York, NY; Albany, NY; Buffalo, NY; Cleveland, OH; Columbus, OH; Indianapolis, IN; Chicago, IL; Springfield, IL. The decision to have twelve viewings of the body would have been not only unprecedented, but excessive, unless the funeral rituals planned for Lincoln were a part of a continuum of reverence for the president that began during his lifetime.

- 33The sentimental reaction to Lincoln’s embalming may also illustrate the novelty of this practice in mid-century America. According to Craughwell, the embalmer’s bill was returned with “This was done and well done” written across the top ([30], p. 9).

- 34Herbert Mitgang describes how Lincoln utilized emblematic political cartoons, as well as portraits, to “arouse enthusiasm” ([33], p. 8) and gain public recognition.

© 2015 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).