FiCT-O: Modelling Fictional Characters in Detective Fiction from the 19th to the 20th Century

Abstract

1. Introduction1

the character is a product of combinations: the combinationis relatively stable (denoted by the recurrence of the semes)and more or less complex (involving more or less congruent,more or less contradictory figures); this complexity determinesthe character’s “personality,” which is just as much a combinationas the odor of a dish or the bouquet of a wine

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

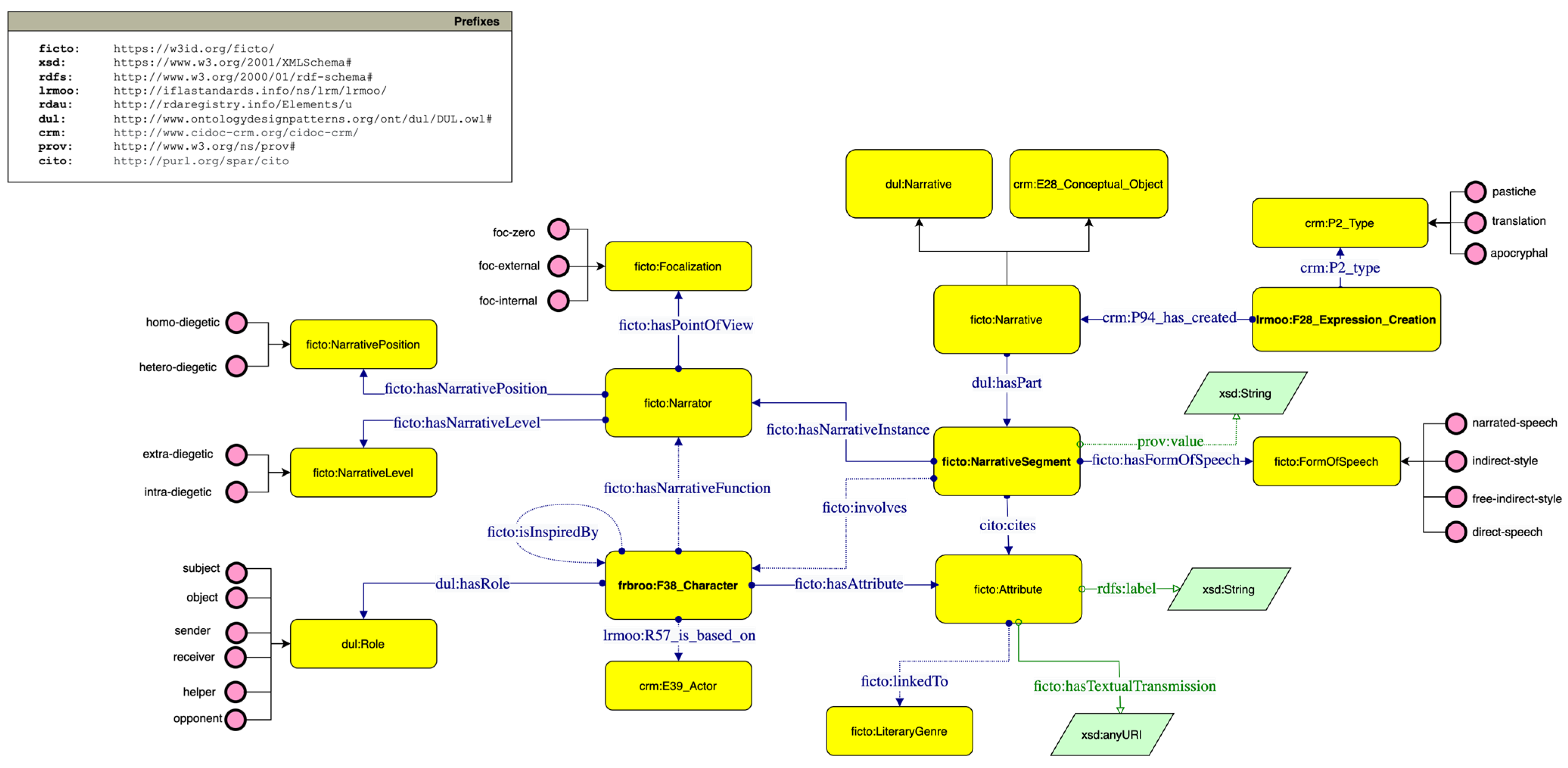

- (1)

- Narrative instance or the narrator’s ontological and functional position about the story, classified along the axes of extradiegetic/intradiegetic and heterodiegetic/homodiegetic;

- (2)

- Focalization, i.e., the filtering perspective of narrative information, ranging from zero to internal and external focalization;

- (3)

- Modes of discourse, encompassing the stylistic and structural forms used to convey speech, thought, or action, including narrated discourse, direct and indirect speech, and free indirect discourse.

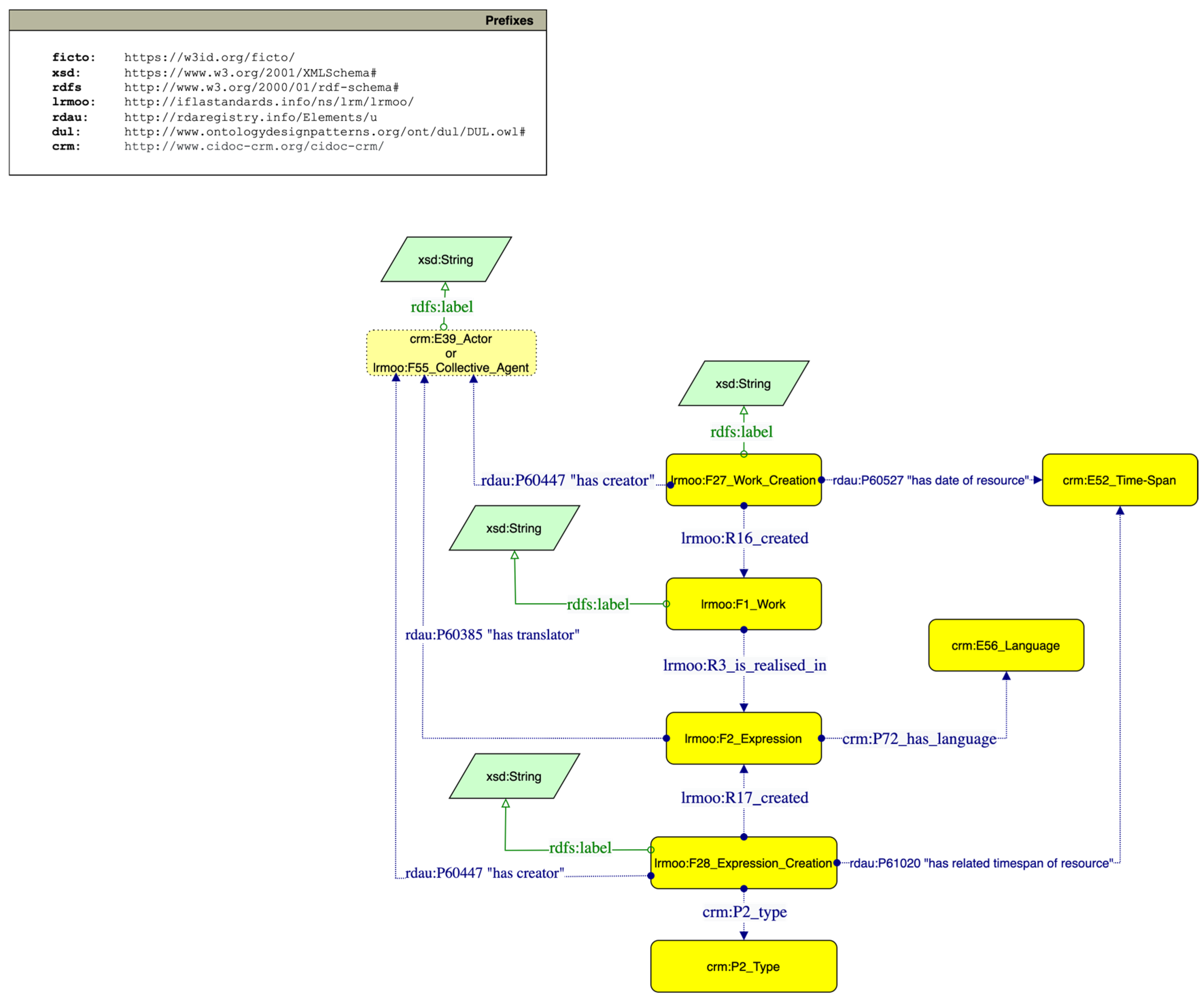

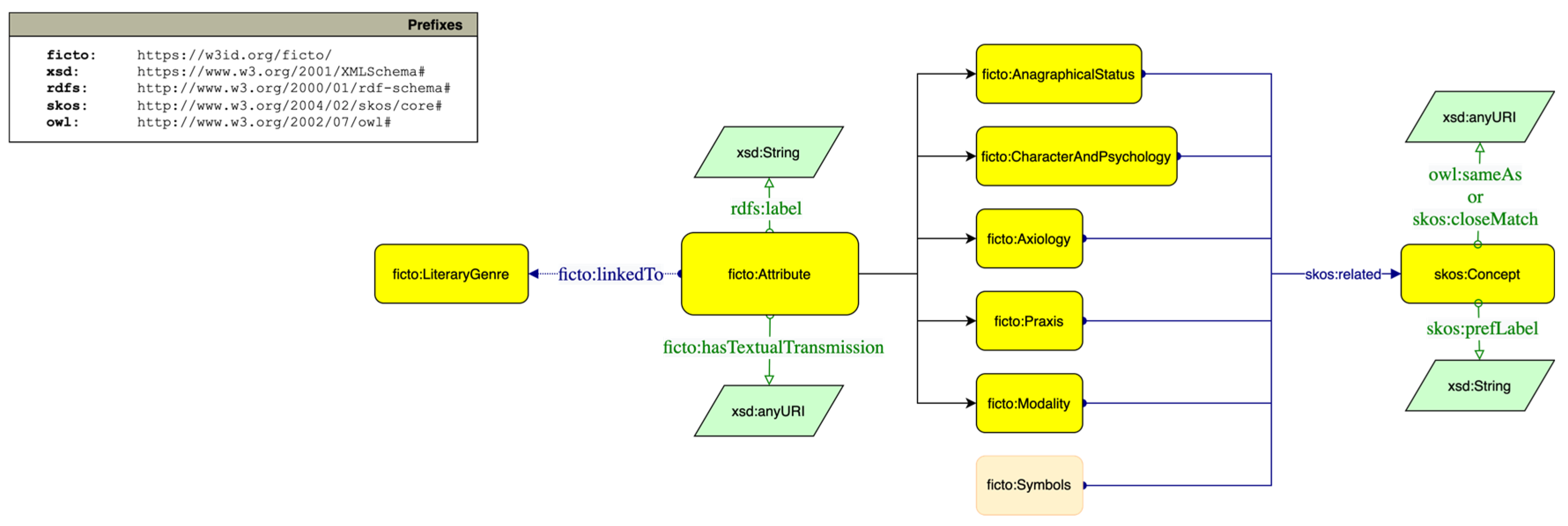

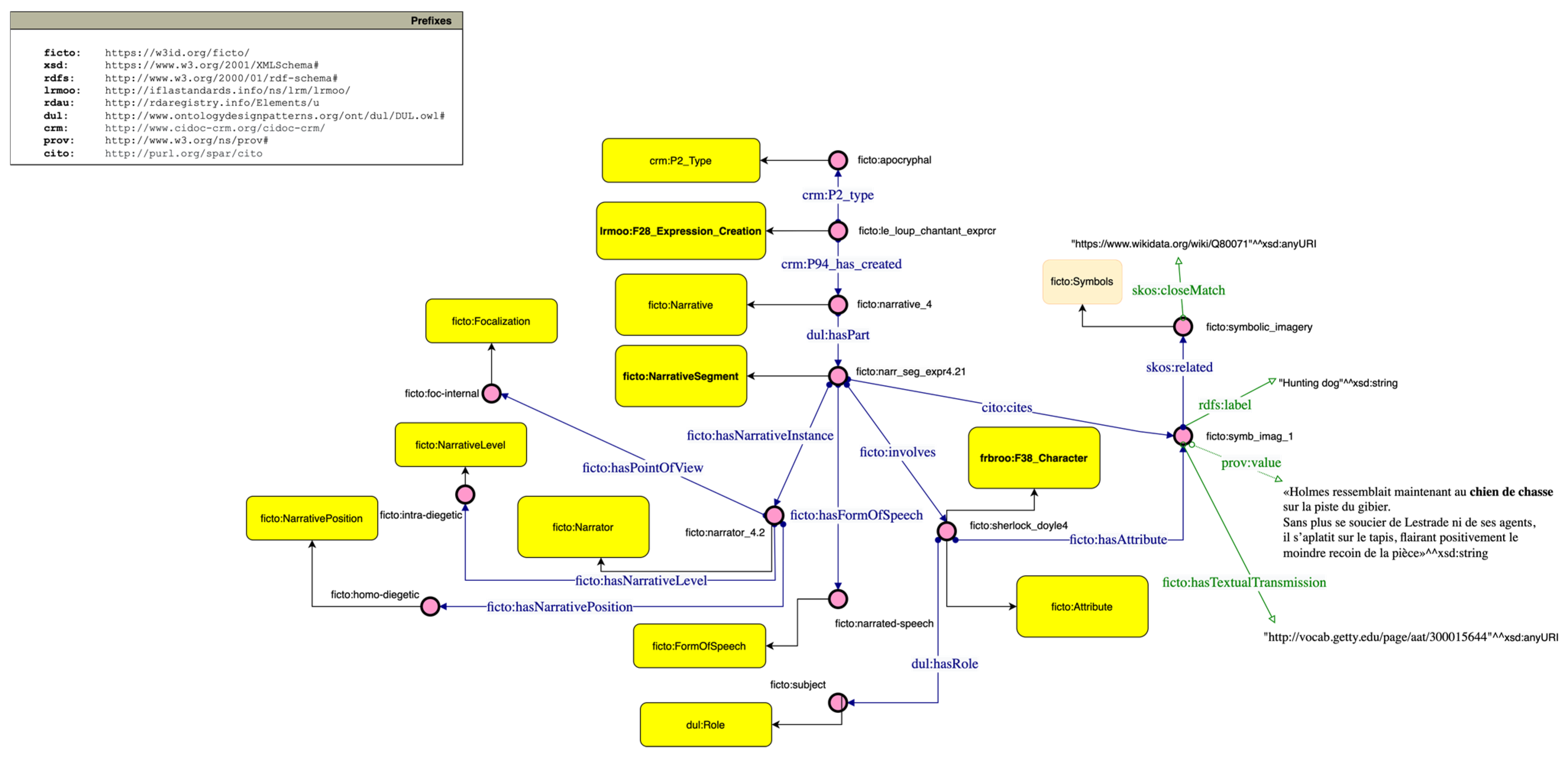

2.2. The Model

Holmes ressemblait maintenant au chien de chasse sur la piste du gibier. Sans plus se soucier de Lestrade ni de ses agents, il s’aplatit sur le tapis, flairant positivement le moindre recoin de la pièce. […] Puis il considéra longuement la surface de marbre qui couvrait celle-ci, allant jusqu’à la mesurer à l’aide du mètre pliant qui ne le quittait jamais.

| Listing 1. RDF/Turtle snippet illustrating part of the encoding of Le loup chantant de Forest Gate by OuLiPoPo. |

| <https://w3id.org/ficto/ExpressionCreation/le_loup_chantant_exprcr> a lrmoo:F28; rdfs:label "Le loup chantant de Forest Gate"^^xsd:string; crm:P2 "http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300404309"^^xsd:anyURI; crm:P4 "1987"^^xsd:gYear; crm:P94 <https://w3id.org/ficto/Narrative/narrative_4>. <https://w3id.org/ficto/Narrative/narrative_4> a ficto:Narrative; dul:hasPart <https://w3id.org/ficto/NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.21>. <https://w3id.org/ficto/NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.21> a ficto:NarrativeSegment; cito:cites ficto:symb_imag_1. ficto:symb_imag_1 a ficto:Symbols; rdfs:label "Hunting dog"^^xsd:string; skos:related <https://w3id.org/ficto/Concept/symbolic_imagery>; ficto:hasTextualTransmission "http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300015644"^^xsd:anyURI. |

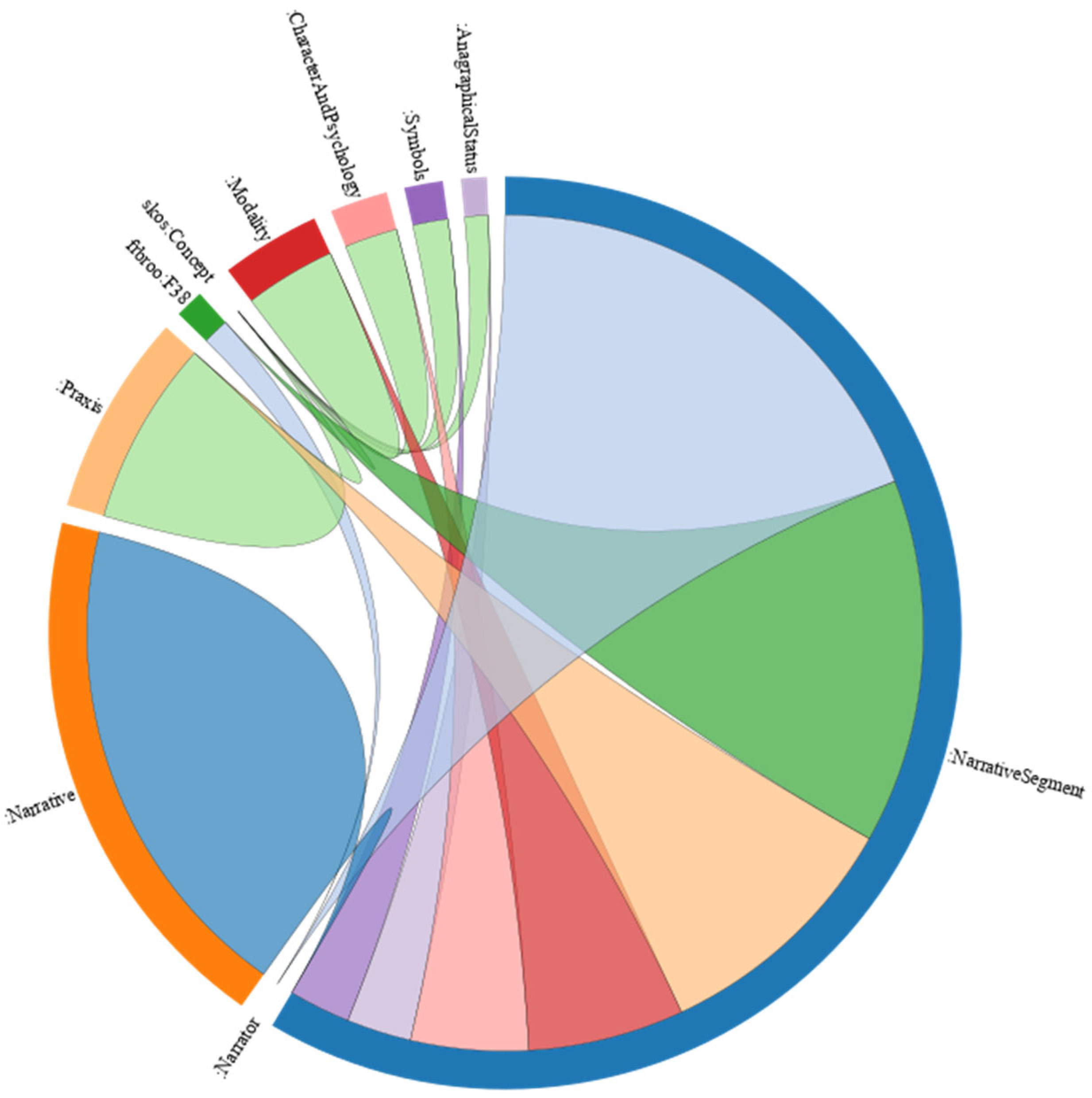

3. Results

- Q1: How many attributes are apocryphal, and to which class do they belong?This question investigates the distribution of character attributes that emerge specifically in those apocryphal portions of the corpus that deviate from the canonical tradition. This investigation is conducted through semantic alignment with the Getty AAT concept [http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300404309 (accessed on 19 August 2025)], which is a controlled vocabulary term used to classify non-canonical or derivative works. By classifying each attribute according to its ontological type, the query aims to identify which conceptual domains, such as axiology, psychology, or praxis, are most subject to reinterpretation, expansion, or transformation across rewritings. This approach allows us to assess how later or non-original versions of the text contribute to the evolution of character construction through intertextual variation.

| attributetype | numOccurrences | |

| 1 | ficto:Axiology | “6”^^xsd:integer |

| 2 | ficto:CharacterAndPsychology | “8”^^xsd:integer |

| 3 | ficto:Modality | “1”^^xsd:integer |

| 4 | ficto:Praxis | “11”^^xsd:integer |

| 5 | ficto:Symbols | “3”^^xsd:integer |

- 2.

- Q2: How many attributes are original to which class do they belong?This question complements Q1 by shifting the focus to the attributes that originate in the canonical core of the corpus—that is, in those narrative segments considered part of the original textual layer. These segments are identified through semantic alignment with the Getty AAT concept [http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300015644 (accessed on 19 August 2025)], which defines the category of “original works” within a controlled vocabulary framework. By classifying these attributes according to their ontological type, the query establishes a baseline semantic profile of the character. This profile serves as a reference model to assess the impact of later reinterpretations. It allows us to measure how much subsequent versions preserve, elaborate on, or subvert the character’s initial narrative configuration.

| attributetype | numOccurrences | |

| 1 | ficto:AnagraphicalStatus | “22”^^xsd:integer |

| 2 | ficto:Axiology | “16”^^xsd:integer |

| 3 | ficto:CharacterAndPsychology | “32”^^xsd:integer |

| 4 | ficto:Modality | “52”^^xsd:integer |

| 5 | ficto:Praxis | “76”^^xsd:integer |

| 6 | ficto:Symbols | “18”^^xsd:integer |

- 3.

- Q3: Does the psychological dichotomy of apathy and hyperactivity, introduced in A Study in Scarlet, persist across later textual transmissions?This question focuses on a recurrent psychological contrast that defines Sherlock Holmes’s characterization from the very beginning of the canon—specifically, the tension between apathy and hyperactivity. By examining references to this duality across various narrative segments and expressions, the inquiry investigates the consistency of this trait in different rewritings and adaptations. The goal is to determine whether certain psychological aspects of the character are preserved, reinterpreted, or disrupted over time, thereby providing insight into the ongoing continuity of narrative identity.

| exprcr | narrseg | value | attribute | |

| 1 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/studio_rosso_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_1.52 | “«S’infilo in fretta il soprabito, muovendosi con una celerità che dimostrava come alla fase di abulia fosse subentrata una crisi di iperattivismo»” | ficto:psych_prof_5 |

| 2 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/studio_rosso_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_1.9 | “«Non c’era sforzo superiore alle sue energie quando lo prendeva un accesso di attivismo, ma ogni tanto cadeva preda di una reazione contraria e rimaneva sdraiato per giorni di fila sul divano del salotto»” | ficto:psych_prof_5 |

| 3 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/le_loup_chantant_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.13 | “«Et Holmes retomba dans une apathie analogue à celle qui a dû saisir Wellington et toute l’Angleterre lorsque nous eûmes cloué Napoléon au rocher de Saint-Hélèn»” | ficto:psych_prof_5 |

| 4 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/le_loup_chantant_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.17 | “«Je trouvai à Sherlock Holmes des allures de félin tandis qu’il marchait de long en large dans un état de fébrilité qui contrastait avec son abattement de l’heure précédente»” | ficto:psych_prof_5 |

| 5 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/studio_rosso_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_1.52 | “«S’infilo in fretta il soprabito, muovendosi con una celerità che dimostrava come alla fase di abulia fosse subentrata una crisi di iperattivismo»” | ficto:psych_prof_4 |

| 6 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/studio_rosso_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_1.9 | “«Non c’era sforzo superiore alle sue energie quando lo prendeva un accesso di attivismo, ma ogni tanto cadeva preda di una reazione contraria e rimaneva sdraiato per giorni di fila sul divano del salotto»” | ficto:psych_prof_4 |

| 7 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/le_loup_chantant_exprcr | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.17 | “«Je trouvai à Sherlock Holmes des allures de félin tandis qu’il marchait de long en large dans un état de fébrilité qui contrastait avec son abattement de l’heure précédente»” | ficto:psych_prof_4 |

- 4.

- Q4: Is the idiomatic expression “Elementary, my dear Watson!” present in Doyle’s texts, or is it apocryphal?This question investigates one of the most iconic expressions attributed to Sherlock Holmes: the idiomatic phrase “Elementary, my dear Watson!”, widely entrenched in the collective imagination. The query aims to determine whether this expression is present in the canonical works of Arthur Conan Doyle or whether it emerged through apocryphal rewritings and adaptations. By tracing its occurrence across both original and non-original narrative segments, the question assesses the extent to which cultural memory and popular reception are grounded in textual evidence or shaped by intertextual reconstruction and reception-driven invention.

| exprcr | narrseg | attribute | value | transmission | |

| 1 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/problema_finale_exprcr | ficto:narr_seg_expr_2.4 | ficto:expression_1 | “«Interessante, per quanto elementare,» concluse, tirando a sedersi nel suo angolo preferito del divano»” | “http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300015644”^^xsd:anyURI |

| 2 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/le_loup_chantant_exprcr | ficto:narr_seg_expr_4.18 | ficto:expression_2 | “«Elémentaire, mon cher Watson!»” | “http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300404309”^^xsd:anyURI |

| 3 | ficto:ExpressionCreation/verità_d_exprcr | ficto:narr_seg_expr_5.2 | ficto:expression_3 | “«- Elementare, mio caro Dupin!—sorride Holmes, seccato in realtà di essere stato prevenuto»” | “http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300404309”^^xsd:anyURI |

- 5.

- Q5: How are praxis-related traits distributed across different literary genres?This question investigates the distribution of praxis-oriented character traits—that is, elements related to action, behavior, gestures, and stylistic embodiment—across distinct literary genres. By correlating praxis attributes with genre classifications, the query seeks to reveal patterns of narrative conduct and expressive stylization that contribute to the construction of genre-specific conventions. The results provide insight into how characters act, behave, or present themselves differently depending on the narrative tradition in which they are inscribed, and how certain gestures or performative codes may serve as genre indicators.

| attribute | genre | first_narrseg | first_value | |

| 1 | ficto:expression_1 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_2.4 | “«Interessante, per quanto elementare,» concluse, tirando a sedersi nel suo angolo preferito del divano»” |

| 2 | ficto:expression_2 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.18 | “«Elémentaire, mon cher Watson!»” |

| 3 | ficto:pers_style_7 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/fairy_tales | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.27 | “«Holmes ridiculement accoutré d’une pèlerine rouge et d’une petite jupe»” |

| 4 | ficto:pers_style_8 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/fairy_tales | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.27 | “«Holmes ridiculement accoutré d’une pèlerine rouge et d’une petite jupe»” |

| 5 | ficto:expression_3 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_5.2 | “«- Elementare, mio caro Dupin!—sorride Holmes, seccato in realtà di essere stato prevenuto»” |

- 6.

- Q6: Which symbolic character traits are associated with one or more literary genres?This question focuses on recurring symbolic traits—such as emblematic objects (e.g., the magnifying glass) and codified gestures—that contribute to the visual and cultural construction of the fictional character. By examining the relationship between these symbolic elements and the literary genres in which they appear, the query explores how such motifs function as genre markers, reinforcing stylistic expectations and interpretive frameworks. The findings highlight how semantic objects come to be associated with specific literary traditions, suggesting that certain physical or material signs can serve as anchors of continuity in the portrayal of the detective figure across canonical and apocryphal texts.

| attribute | genre | first_narrseg | first_value | |

| 1 | ficto:recur_p_obj_1 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_1.56 | “«Non aveva ancora finito di parlare che tirò fuori di tasca un metro a nastro e una grossa lente d’ingrandimento»” |

| 2 | ficto:recur_p_obj_1 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.23 | “«Puis il considéra longuement la surface de marbre qui couvrait celle-ci, allant jusqu’à la mesurer à l’aide du mètre pliant qui ne le quittait jamais»” |

| 3 | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_1.56 | “«Non aveva ancora finito di parlare che tirò fuori di tasca un metro a nastro e una grossa lente d’ingrandimento»” |

| 4 | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_2.3 | “«Poi, con un’espressione di vivo interesse, posò la sigaretta, si avvicinò alla finestra e lo osservò nuovamente con una lente di ingrandimento»” |

| 5 | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_4.22 | “«sa loupe»“ |

| 6 | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_5.1 | “«Stanno poi sorbendo i loro cappuccini quando un uomo alto, ben riconoscibile dal mantello a larghe pieghe e dal singolare berretto, viene a esaminare le loro targhette con una grossa lente—Permettete? Holmes,—dice presentando anche il suo compagno, sul risvolto del quale si legge: «Dr. Watson»” |

| 7 | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 | ficto:LiteraryGenre/detective_fiction | ficto:NarrativeSegment/narr_seg_expr_5.3 | “«[…] per dare la parola a Holmes, che ha alzato la sua lente.—C’è—dice l’esperto di cani fluorescenti,—un puntino che vorrei mettere subito su una certa i […]»” |

- 7.

- Q7: What types of symbolic traits recur across the corpus, and how frequently do they appear?This question explores the typology and frequency of symbolic traits associated with fictional characters across the entire corpus. These traits include both recurring physical objects (such as the magnifying glass or tape measure) and symbolic metaphors or expressions (such as “hunting dog” or “devil of a man”), each of which contributes to the semantic construction of character identity and genre coherence. By quantifying the number of occurrences of each symbol and grouping them according to their ontological label, the query highlights which motifs are most persistent across canonical and apocryphal texts. This allows us to assess how symbolic recurrence functions as a mechanism of narrative stabilization, fostering continuity of interpretation and recognizability within the evolving fictional universe.

| attribute | genre | first_narrseg | first_value | |

| 1 | ficto:recur_p_obj_1 | “Tape measure” | “2”^^xsd:integer | ficto:recur_p_obj_1 |

| 2 | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 | “Magnifying glass” | “5”^^xsd:integer | ficto:recur_p_obj_2 |

| 3 | ficto:symb_imag_1 | “Hunting dog” | “3”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_1 |

| 4 | ficto:symb_imag_2 | “Bloodhound” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_2 |

| 5 | ficto:symb_imag_3 | “Lark” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_3 |

| 6 | ficto:symb_imag_4 | “General” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_4 |

| 7 | ficto:recur_p_obj_3 | “Pipe du matin (morning pipe)” | “3”^^xsd:integer | ficto:recur_p_obj_3 |

| 8 | ficto:recur_p_obj_4 | “Silver cigarette case” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:recur_p_obj_4 |

| 9 | ficto:symb_imag_5 | “Diable d’homme (devil of a man)” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_5 |

| 10 | ficto:symb_imag_6 | “Feline-like manner” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_6 |

| 11 | ficto:recur_p_obj_5 | “Persian babouche (Persian slippers)” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:recur_p_obj_5 |

| 12 | ficto:symb_imag_7 | “Expert in fluorescent dogs” | “1”^^xsd:integer | ficto:symb_imag_7 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The authors contributed to this paper as follows: Lorenzo Sabatino was responsible for the Introduction and the Conclusion. Enrica Bruno was responsible for the sections concerning the Model and the Results. Both authors jointly contributed to the Methods and Discussion sections. Francesca Tomasi acted as scientific supervisor for the overall research project. |

| 2 | For a comprehensive survey, see (Varadarajan and Dutta 2022). Additionally, refer to the more recent preprint by (Scotti et al. 2021). |

| 3 | For a comprehensive overview of all the materials, please visit the following link: https://github.com/enricabruno/ficto (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 4 | GO FAIR Initiative. FAIR Principles. Available online: https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 5 | Wikidata. Available online: https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Wikidata:Main_Page (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 6 | Getty AAT (Art & Architecture Thesaurus). Available online: https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 7 | DBpedia. Available online: https://www.dbpedia.org/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 8 | IFLA. FRBR: Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records. Available online: https://repository.ifla.org/items/54925d49-b08d-4aeb-807c-1b509ec40b55 (accessed 19 August 2025). |

| 9 | IFLA. IFLA Library Reference Model (LRM). Available online: https://repository.ifla.org/items/94aedb49-2d6e-4a6d-9974-f33abb7e3c0e (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 10 | RDA Registry. Resource Description and Access (RDA). Available online: https://www.rdaregistry.info/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 11 | CIDOC CRM. CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 12 | W3C. PROV-O: The PROV Ontology. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/prov-o/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 13 | Peroni, Silvio. CiTO: Citation Typing Ontology. Available online: https://sparontologies.github.io/cito/current/cito.html (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 14 | LOA-CNR. DOLCE: Descriptive Ontology for Linguistic and Cognitive Engineering. Available online: https://www.loa.istc.cnr.it/ontologies/DUL.owl (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

| 15 | Daquino and Tomasi (2015). HiCO: Historical Context Ontology. Available online: https://marilenadaquino.github.io/hico/ (accessed on 19 August 2025). |

References

- Ascari, Maurizio. 2014. The Dangers of Distant Reading: Reassessing Moretti’s Approach to Literary Genres. Genre 47: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, Mieke. 1990. Teoria della narrativa. Translated by Patrizia Violi. Milano: Bompiani. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bartalesi, Valentina, Carlo Meghini, and Daniele Metilli. 2016. Steps Towards a Formal Ontology of Narratives Based on Narratology. In 7th Workshop on Computational Models of Narrative (CMN 2016). Edited by Mark A. Finlayson, Bernhard Fisseni, Benedikt Löwe and Jan Christoph Meister. Open Access Series in Informatics (OASIcs). Kraków: Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, vol. 53, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, Roland. 1967. La mort de l’auteur. In Le Bruissement de la langue. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1971. Introduzione all’analisi strutturale dei racconti. In Semiologia e urbanistica. Torino: Einaudi, pp. 127–57, Originally published as 1996. Communications 8. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1974. S/Z. Translated by Richard Miller. Oxford: Blackwell. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Beretta, Francesco, and Gideon Bruseker. 2022. CRMsoc v 0.2: A New Foundational Perspective. CIDOC-CRM Resources. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/crmsoc (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Bode, Katherine. 2017. The Equivalence of Close and Distant Reading; or, Toward a New Object for Data-Rich Literary History. Modern Language Quarterly 78: 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brémond, Claude. 1974. Logique du récit. Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations 29: 757–76. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Alex. 2001. Truth in Fiction: The Story Continued. In Content and Modality: Themes from the Philosophy of Robert Stalnaker. Edited by Judith Thomson and Alex Byrne. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 189–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cawelti, John G. 1976. Adventure, Mystery, and Romance: Formula Stories as Art and Popular Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatman, Seymour. 1978. Storia e discorso. Translated by Luigi Fassò. Torino: Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Ciotti, Fabio. 2016. Toward a Formal Ontology for Narrative. Matlit 4: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciotti, Fabio. 2021. Distant Reading in Literary Studies: A Methodology in Quest of Theory. Testo e Senso 23: 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, Rossana, and Antonio Lieto. 2013. Ontological Representations of Narratives: A Case Study on Stories and Actions. Open Access Series in Informatics (OASIcs) 32: 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, Rossana, Vincenzo Lombardo, and Antonio Pizzo. 2019. The Ontology of Drama. Applied Ontology 14: 79–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daquino, Marilena, and Francesca Tomasi. 2015. Historical context ontology (HiCO): A conceptual model for describing context information of cultural heritage objects. In Metadata and Semantics Research. Edited by Eva Garoufallou, Richard Hartley and Panorea Gaitanou. Communications in Computer and Information Science. Cham: Springer, vol. 544, pp. 424–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, Daniel C. 1990. The interpretation of texts, people and other artifacts. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 50: 177–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Arthur Conan. 2015a. Il mastino dei Baskerville. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore, Originally published as 1902. The Hound of the Baskervilles. London: George Newnes. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Arthur Conan. 2015b. Uno studio in rosso. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore, Originally published as 1887. A Study in Scarlet. London: Ward, Lock & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Arthur Conan. 2018. Il problema finale. In Sherlock Holmes. Tutti i romanzi e tutti i racconti. Milano: Mondadori, pp. 713–26, Originally published as 1893. The Final Problem. London: The Strand Magazine. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Johanna. 2017. Why Distant Reading Isn’t. PMLA. Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 132: 628–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, Umberto. 1979. Lector in fabula. La cooperazione interpretativa nei testi narrativi. Milano: Bompiani. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto. 2002. Sulla letteratura. Milano: Bompiani. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, Umberto, and Thomas A. Sebeok, eds. 1983. The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, Jens, Fotis Jannidis, and Ralf Schneider. 2010. Characters in Fictional Worlds: Understanding Imaginary Beings in Literature, Film, and Other Media. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1969. Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur? Bulletin de la Société Française de Philosophie 63: 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, Stacie. 2007. Fictional Characters. Philosophy Compass 2: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruttero, Carlo, Lucentini Franco, and Charles Dickens. 1989. La verità sul caso D. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci, Giorgia. 2023. Close Reading e Codifica Interpretativa: Edizione Digitale di Libretti d’Opera. Umanistica Digitale 7: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carpintero, Manuel. 2020. Co-Identification and Fictional Names. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 101: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genette, Gérard. 1976. Figure III: Discorso del racconto. Translated by Roberta Pellerey. Torino: Einaudi. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1989. Palinsesti: La letteratura al secondo grado. Translated by Maria Donzelli. Torino: Einaudi. First published 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien. 1966. Sémantique structurale: Recherche de méthode. Paris: Larousse. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien. 1973. Les actants, les acteurs et les figures. In Sémiotique narrative et textuelle. Paris: Larousse, pp. 161–76. [Google Scholar]

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien. 1979. Du sens. Essais sémiotiques. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, Thomas R. 1993. A Translation Approach to Portable Ontology Specifications. Knowledge Acquisition 5: 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, Thomas R. 2009. Ontology. In Encyclopedia of Database Systems. Edited by Ling Liu and M. Tamer Özsu. New York: Springer, pp. 1963–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, Janna, and Stefan Schulz. 2019. Representing Literary Characters and Their Attributes in an Ontology. Paper Preserted at the Joint Ontology Workshops (JOWO 2019), Graz, Austria, September 10–12; CEUR Workshop Proceedings 2518. pp. 1–10. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2518/paper-WODHSA4.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Hermans, Theo. 2007. The Conference of the Tongues. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Horstmann, Jan. 2020. Undogmatic Literary Annotation with CATMA: Manual, Semi-Automatic and Automated. In Annotations in Scholarly Editions and Research: Functions, Differentiation, Systematization. Edited by Julia Nantke and Frederik Schlupkothen. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, Jan, Christian Lück, and Immanuel Normann. 2024. Systems of Intertextuality: Towards a Formalisation of Text Relations for Manual Annotation and Automated Reasoning. Digital Humanities Quarterly 17. Available online: https://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/17/3/000731/000731.html (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Ingarden, Roman. 1973. The Literary Work of Art: An Investigation on the Borderlines of Ontology, Logic, and Theory of Literature. Translated by George G. Grabowicz. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Italia, Paola. 2020. Editing Duemila: Per una filologia dei testi digitali. Roma: Salerno Editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Jockers, Matthew L. 2013. Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History. Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kestemont, Mike, and Luc Herman. 2019. Can Machines Read (Literature)? Umanistica Digitale 3: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautter, Benjamin. 2024. The Scales of (Computational) Literary Studies: Martin Mueller’s Concept of Scalable Reading in Theory and Practice. In Zoomland: Exploring Scale in Digital History and Humanities. Edited by Florentina Armaselu and Andreas Fickers. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 261–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, Fred, and Alberto Voltolini. 2018. Fictional Entities. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/fictional-entities/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Lotman, Jurij M. 1980. Testo e contesto: Semiotica dell’arte e della cultura. Edited by Susan Salvestroni. Biblioteca di cultura moderna. Roma and Bari: Laterza. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Marchese, Angelo. 1983. L’officina del racconto: Semiotica della narratività. Milano: Arnoldo Mondadori Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Matković, Sanja. 2018. The Conventions of Detective Fiction, or Why We Like Detective Novels. Digital Humanities Quarterly 11: 445–60. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, Willard. 2008. Neglected, Not Rejected: Is There a Future for Literary Computing? Paper presented at the School of Humanities 20/20/20 Lecture Series, London, UK, March 12; London: King’s College London. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Franco. 2000. Conjectures on World Literature. New Left Review 2: 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Franco. 2013a. Distant Reading. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Franco. 2013b. Operationalizing. Or, the Function of Measurement in Literary Theory. New Left Review 84: 103–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, Martin. 2012. Scalable Reading. May 29. Available online: https://sites.northwestern.edu/scalablereading/2020/04/26/scalable-reading/ (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Mueller, Martin. 2014. Shakespeare His Contemporaries: Collaborative Curation and Exploration of Early Modern Drama in a Digital Environment. Digital Humanities Quarterly 8. Available online: https://dhq-static.digitalhumanities.org/pdf/000183.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Munday, Jeremy, Sara Ramos Pinto, and Jacob Blakesley. 2022. Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications, 5th ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Katherine, and Barry Smith. 2008. Applied Ontology: An Introduction. Metaphysical Research. Frankfurt am Main: Ontos Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- OULIPOPO. 1975. Le loup chantant de Forest Gate. Winchester: Subsidia Pataphysica. [Google Scholar]

- Pannach, Franziska, Luotong Cheng, and Federico Pianzola. 2024. The GOLEM-Knowledge Graph and Search Interface: Perspectives into Narrative and Fiction. In Proceedings of the Computational Humanities Research Conference 2024. Edited by Wouter Haverals, Marijn Koolen and Laure Thompson. Aarhus: CEUR, pp. 462–71. [Google Scholar]

- Petronio, Giuseppe, ed. 1985. Il punto su: Il romanzo poliziesco. Bari: Armando Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Pierazzo, Elena. 2015. Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories, Models and Methods. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, Andrew. 2015. Novel Devotions: Conversional Reading, Computational Modelling, and the Modern Novel. New Literary History 46: 63–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, Andrew. 2019. Enumerations: Data and Literary Study. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pistelli, Maurizio. 2006. Un secolo in giallo. Storia del poliziesco italiano. Roma: Editori Riuniti. [Google Scholar]

- Presutti, Valentina, and Aldo Gangemi. 2016. Dolce+D&S Ultralite and its main Ontology Design Patterns. In Presutti, Valentina and Aldo Gangemi, Ontology Engineering with Ontology Design Patterns—Foundations and Applications. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, Graham. 2013. Creating Non-Existents. In Truth in Fiction. Edited by Françoise Salvan. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 107–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestman, Martin, ed. 2003. The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Propp, Vladimir Ja. 1966. Morfologia della fiaba. Translated by Gian Luigi Bravo. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, Paul. 1983–1985. Temps et récit. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Rouillé, Louis. 2023. The Paradox of Fictional Creatures. Philosophies 8: 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepka, Charles J. 2005. Detective Fiction. London: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., Antonio Sotgiu, Gaia Tomazzoli, Claudio Masolo, Daniele Porello, and Roberta Ferrario. 2023. Ontological Modelling of Scholarly Statements: A Case Study in Literary Criticism. In Formal Ontology in Information Systems. Edited by Roberta Ferrario and Werner Kuhn. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 349–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., Pietro Sichera, and Daria Spampinato. 2021. Toward the Representation of Claims in Ontologies for the Digital Humanities. Paper Preserted at the SWODCH 2021: Semantic Web and Ontology Design for Cultural Heritage, Joint Workshop of ICBO 2021, Bolzano, Italy, July; CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Available online: https://iris.cnr.it/handle/20.500.14243/442914 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Schöch, Christof. 2017. Topic Modelling Genre: An Exploration of French Classical and Enlightenment Drama. Digital Humanities Quarterly 11. Available online: https://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/2/000291/000291.html (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Schöch, Christof, Maria Hinzmann, Julia Röttgermann, Katharina Dietz, and Anne Klee. 2022. Smart Modelling for Literary History. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 16: 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, Luca, Federico Pianzola, and Franziska Pannach. 2021. Grounding the Development of an Ontology for Narrative and Fiction. arXiv. Available online: https://www.semantic-web-journal.net/system/files/swj3880.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Segre, Cesare. 1974. Le strutture e il tempo. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Barbara Herrnstein. 2016. What Was Close Reading? A Century of Method in Literary Studies. Minnesota Review 87: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Barry, and Werner Ceusters. 2015. Aboutness: Towards Foundations for the Information Artifact Ontology. Paper Preserted at the Sixth International Conference on Biomedical Ontology (ICBO 2015), Lisbon, Portugal,, July 27–30; Edited by Paulo Costa and João Almeida. , CEUR Workshop Proceedings. vol. 1515, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1515/regular10.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Tally, Robert T. 2007. Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. Modern Language Quarterly 68: 132–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, Amie L. 1999. Fiction and Metaphysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Todorov, Tzvetan. 1966. Typology of Detective Fiction. In Poética de la prosa. Paris: Seuil, pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, Francesca, Gioele Barabucci, and Fabio Vitali. 2021. Supporting Complexity and Conjectures in Cultural Heritage Descriptions. Paper Preserted at the Collect and Connect: Archives and Collections in a Digital Age (COLCO 2020), Leiden, The Netherlands, November 23–24, CEUR Workshop Proceedings. vol. 2810, pp. 104–15. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11585/820304 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Tomaševskij, Boris. 1965. La poetica: Teoria della letteratura. Translated by Remo Faccani. Torino: Einaudi. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Tomazzoli, Gaia, and Jansan Favazzo. 2024. Sanfilippo-Tomazzoli-Paolini Paoletti-Favazzo-Ferrario, per un’analisi dei personaggi tra letteratura, filosofia e ontologia applicata. Paper presented at the del XIII Convegno Annuale AIUCD, Me.Te. Digitali. Mediterraneo in Rete tra Testi e Contesti, Catania, Italy, May 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, Ted. 2017. A Genealogy of Distant Reading. Digital Humanities Quarterly 11. Available online: http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/2/000317/000317.html (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Underwood, Ted. 2019. Distant Horizons: Digital Evidence and Literary Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan, Udaya, and Biswanath Dutta. 2022. Models for Narrative Information: A Study. Knowledge Organization 49: 172–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuti, Lawrence. 2017. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation, 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, Kendall L. 1990. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weitin, Thomas, and Niels Werber, eds. 2017. Scalable Reading. Special Issue. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 47. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens, Matthew. 2012. Canons, Close Reading, and the Evolution of Method. In Debates in the Digital Humanities. Edited by Matthew K. Gold. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 249–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimsatt, William K., and Monroe C. Beardsley. 1946. The Intentional Fallacy. The Sewanee Review 54: 468–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zöllner-Weber, Amélie, and Andreas Witt. 2006. Ontology for a Formal Description of Literary Characters. Paper Preserted at the Digital Humanities 2006, Paris, France, July 5–9, pp. 350–52. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruno, E.; Sabatino, L.; Tomasi, F. FiCT-O: Modelling Fictional Characters in Detective Fiction from the 19th to the 20th Century. Humanities 2025, 14, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14090180

Bruno E, Sabatino L, Tomasi F. FiCT-O: Modelling Fictional Characters in Detective Fiction from the 19th to the 20th Century. Humanities. 2025; 14(9):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14090180

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruno, Enrica, Lorenzo Sabatino, and Francesca Tomasi. 2025. "FiCT-O: Modelling Fictional Characters in Detective Fiction from the 19th to the 20th Century" Humanities 14, no. 9: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14090180

APA StyleBruno, E., Sabatino, L., & Tomasi, F. (2025). FiCT-O: Modelling Fictional Characters in Detective Fiction from the 19th to the 20th Century. Humanities, 14(9), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14090180