The GOLEM Ontology for Narrative and Fiction

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Narrative Theory and Computational Literary Studies

- The first obstacle concerns the complexity of literary studies as a knowledge domain, which stems from varying interpretations of concepts across different scholarly traditions and theories. This shows the necessity of new approaches that allow us to represent the plurality of different perspectives and narrative models while at the same time making them comparable.

- The second obstacle concerns fundamental gaps that remain in how digital systems represent and process narratives. Digital libraries, especially those focused on cultural heritage, have developed rich models to describe the metadata of literary works and their cataloging, but they fail to offer services specifically addressing the content of such works (Meghini et al. 2021). This limitation creates a significant barrier to comparative narrative analysis across various texts and media forms.

1.2. Semantic Web Technology for Literary Studies

2. Related Works

2.1. Domain-Independent Narrative Ontologies

2.2. Domain-Specific Narrative Ontologies

2.3. State of the Art of Narrative Ontologies

3. Methodology

3.1. Implementation Steps

- Step 1: Defining the domain and selecting cultural objects.We began by defining our domain of interest—narrative and fiction—and selecting a representative set of cultural objects. These included literary works and fanfiction, with a particular focus on Archive of Our Own (AO3) fanfiction as an initial dataset. The complexity of fanfiction, which involves intertextuality, character reinterpretation, and variations in setting and plot, provided a challenging yet valuable testbed for our ontology.

- Step 2: Conceptual modeling.We developed multiple models to capture the structure and features of narrative texts. First, we created a conceptual map based on real data, identifying recurring elements in existing metadata and annotations. Next, we constructed a theoretical model informed by literary theory and fan wikis, incorporating key concepts from narratology to ensure that the ontology aligns with established scholarly frameworks. Given the importance of scholarly debate and perspectivism in humanistic research, we focused on concepts that are broad enough and sufficiently expressive to serve theories based on different epistemological assumptions and definitions of key concepts (Passalacqua and Pianzola 2016).

- Step 3: Metadata retrieval and gap analysis.To populate the ontology with meaningful data, we retrieved metadata for the selected cultural objects. This process involved addressing gaps in traditional library cataloging systems, fan archives, and fan wikis. By examining these diverse sources, we ensured that our ontology supports both formal cataloging standards and community-driven categorizations.

- Step 4: Schema alignment and data standardization.To enhance data interoperability and reusability, we aligned the Archive of Our Own (AO3) metadata schema with international standards. Specifically, we referred to the Work, Expression, Manifestation, Item (WEMI) structure from the Library Reference Model (LRM) to manage different aspects of narratives, fictional entities, and their relations with media franchises. Furthermore, we reused ontology design patterns from foundational ontologies such as DOLCE and domain-specific standards like CIDOC-CRM, ensuring compatibility with established semantic frameworks.

- Step 5: Ontology construction and evaluation.The final step involved creating an integrated conceptual model that merges real-world metadata with our theoretical framework. Our ontology balances generality and specificity by selecting only classes broad enough to cover multiple domains while expressing the core components of narrative and fiction. Instead of introducing numerous highly specific classes (e.g., for literary genres or character taxonomies), we adopted the CIDOC-CRM E55_Type pattern. This approach allows us to handle theory-specific concepts, such as Propp’s character functions, through controlled vocabularies, providing flexibility for comparative analysis. The ontology was implemented as an RDF graph, and we formulated a set of competency questions (Presutti et al. 2009) to test its representational adequacy and ensure the correctness of the data. For reasons of space, this evaluation is described in (Yang 2025). In addition, we performed a structural evaluation of the ontology using OntoMetrics1, which provided a quantitative assessment of the model’s complexity and design (see Appendix A for a selection of key metrics). We also evaluated the ontology’s compliance with the FAIR principles using FOOPS!2, obtaining an overall score of 0.89.

3.2. Principles Guiding the Conceptual Modeling

3.3. Information Requirements

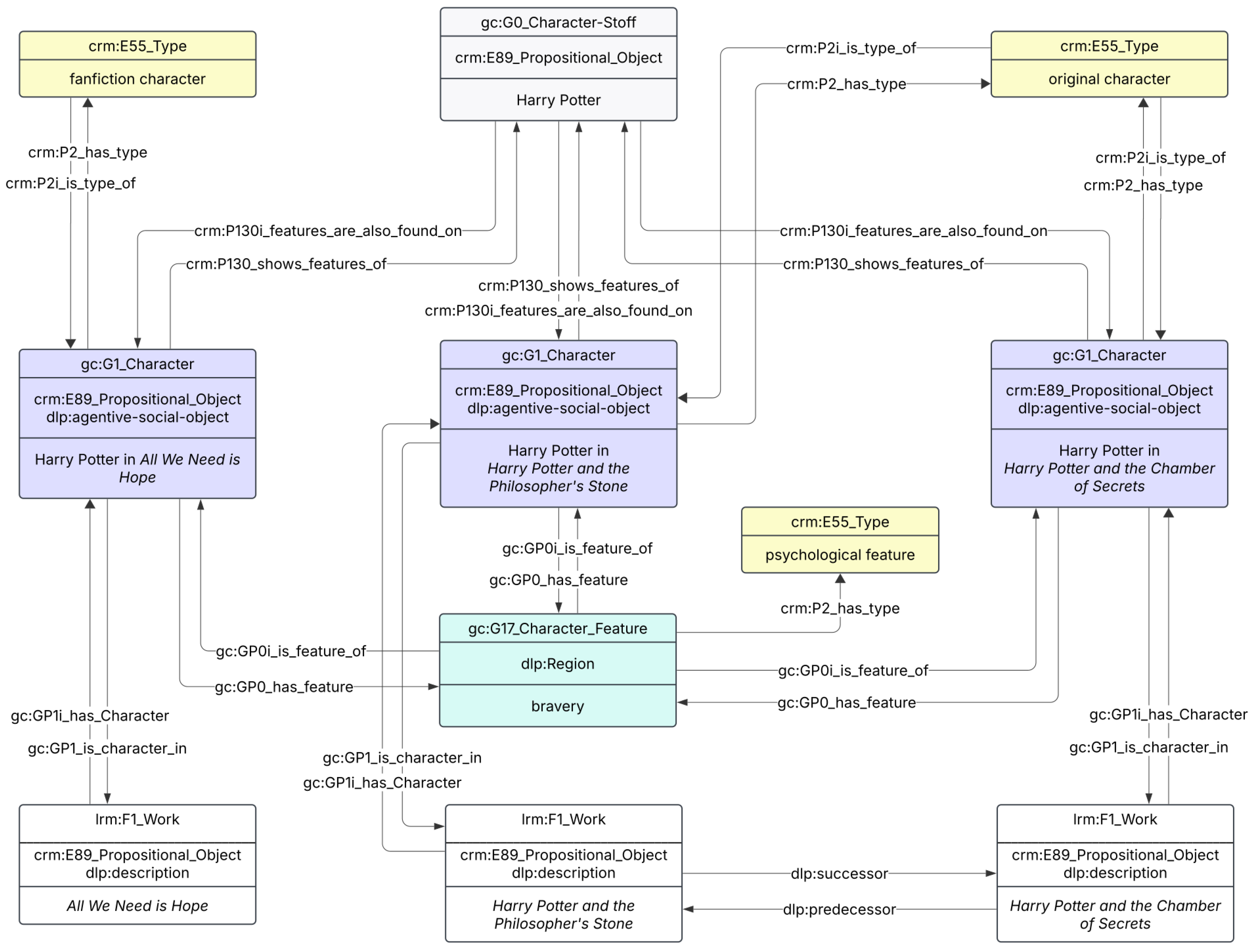

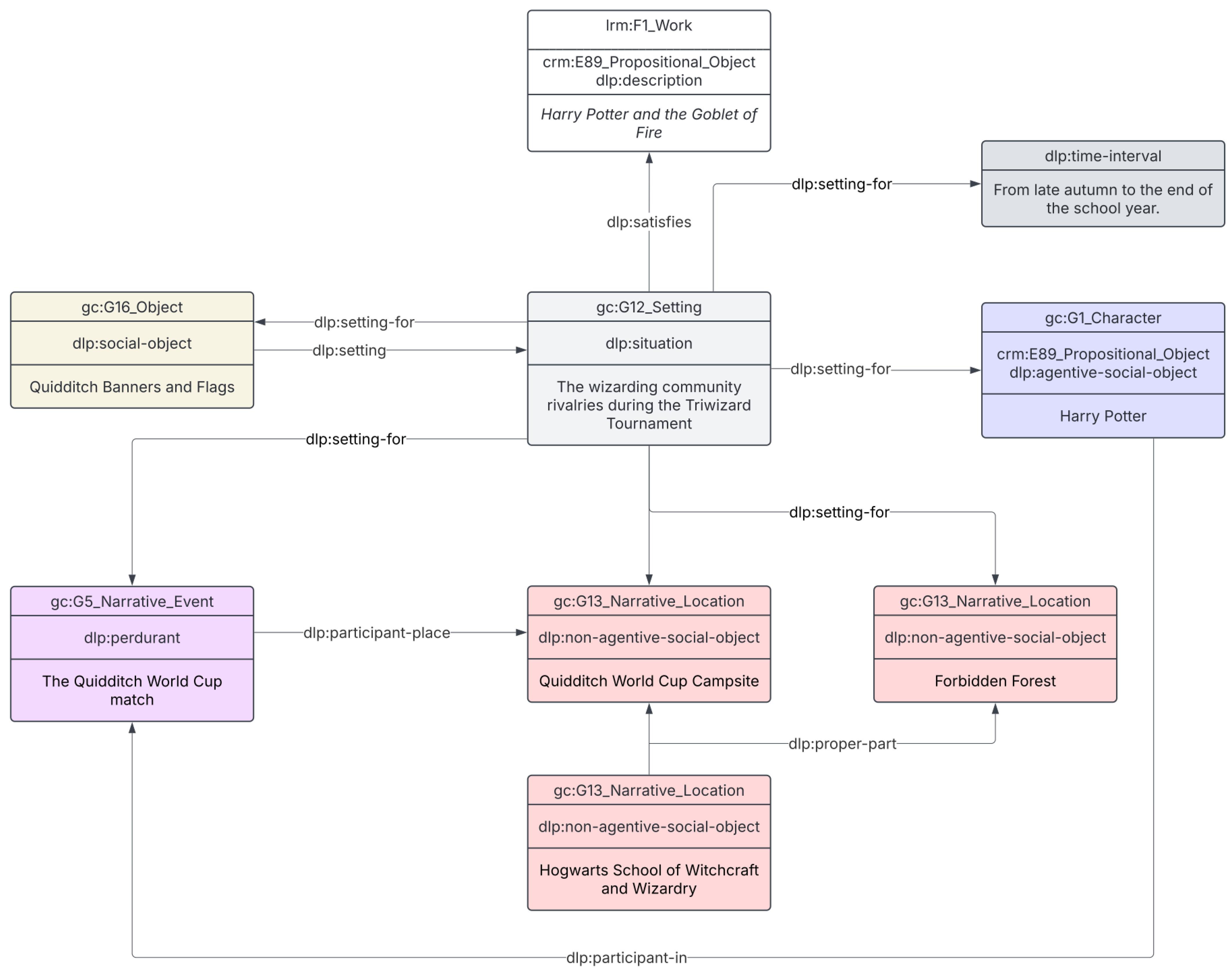

- Fictional entities, particularly characters, often appear across different narrative representations, such as novels, film adaptations, and user-generated content like fan wikis. The ontology must support cross-media linkage, enabling the identification of entities across multiple sources while distinguishing variations in their depiction.

- Characters are defined by recognizable attributes, such as appearance, abilities, and personality traits. These features may be explicitly stated in the text or inferred from narrative descriptions and reader interpretations. The ontology must accommodate both explicit and inferred attributes while allowing for different levels of detail.

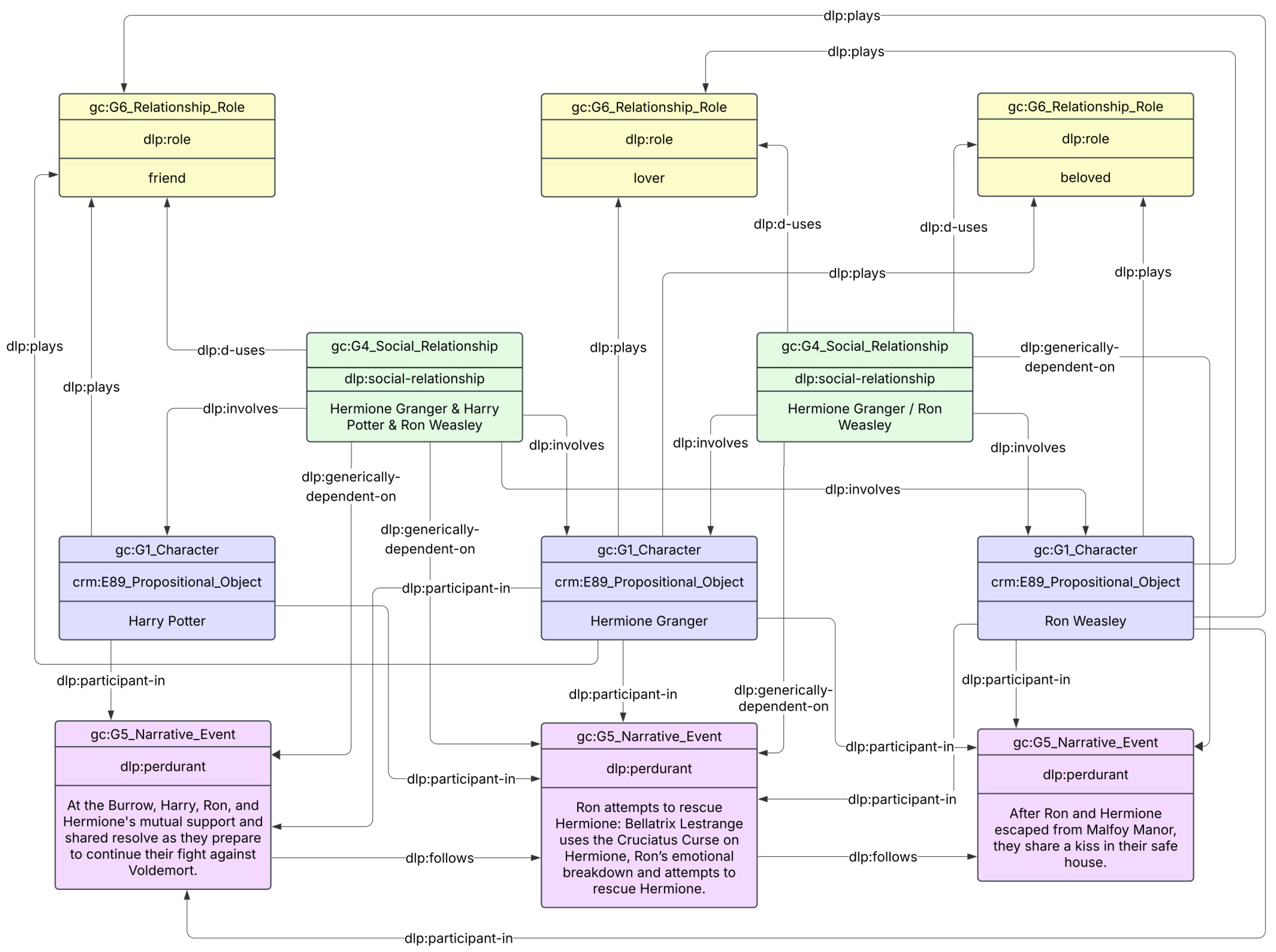

- Narratives frequently revolve around character interactions, such as friendships, rivalries, and familial ties. The ontology must model social relationships dynamically, capturing their evolution throughout a story while enabling comparative analysis across narratives.

- Characters are central to the progression of a story, engaging in key events such as battles, dialogues, or discoveries. The ontology must express character involvement in events, specifying their roles and actions within the narrative framework.

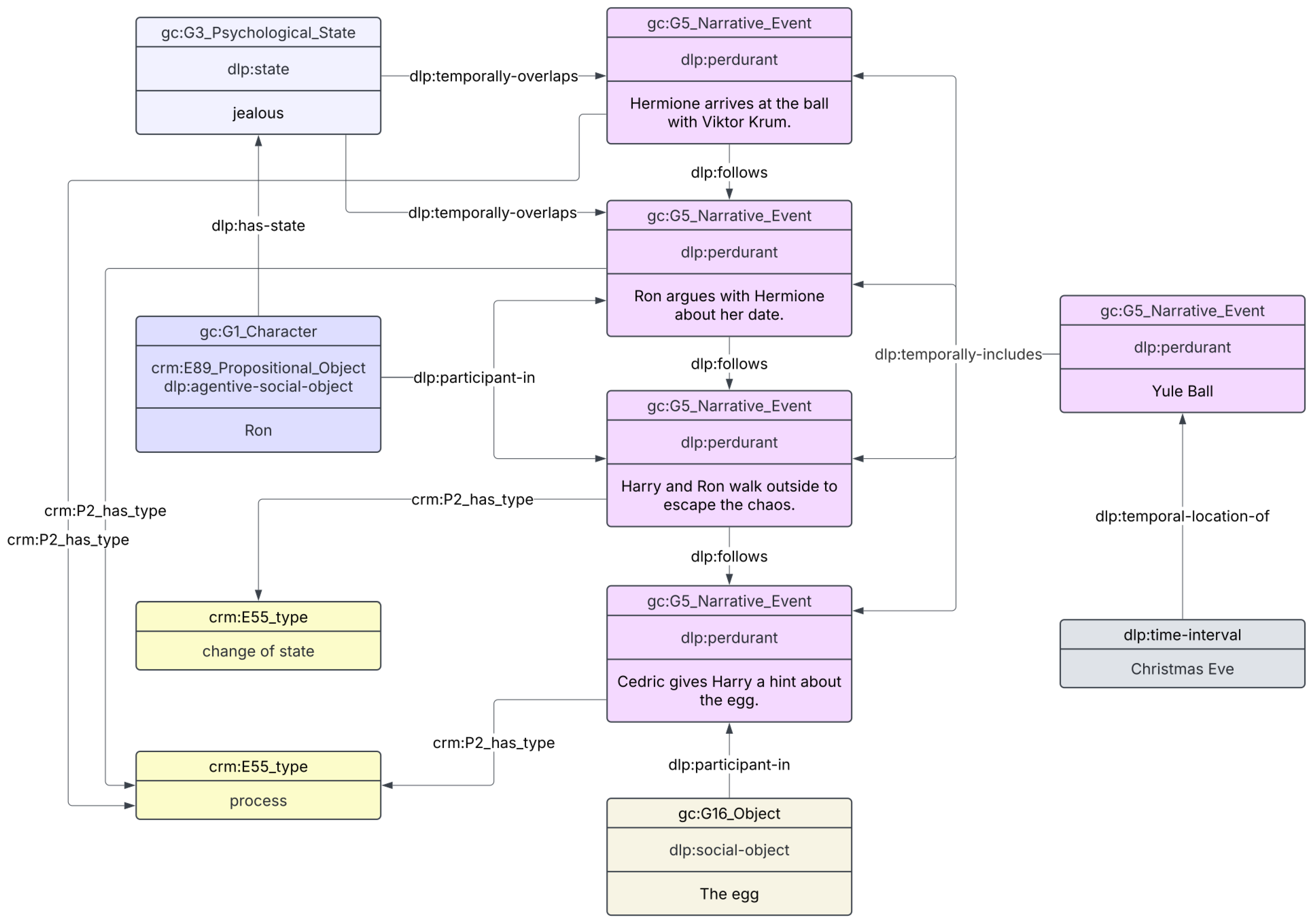

- Narrative information is typically presented in a sequence but can be reorganized according to different principles, such as chronological order. The ontology must support multiple ways of structuring events, accommodating various analytical and interpretive approaches.

- Characters and events serve specific functions within the story, such as protagonists, antagonists, or mentors. The ontology must encode these roles, drawing from established literary theories while remaining flexible enough to incorporate alternative categorizations.

- Narrative meaning is constructed through both explicit statements (e.g., “The knight is brave”) and inferred details (e.g., “The knight charges into battle despite overwhelming odds”). The ontology must distinguish between direct assertions made within the text and interpretations derived from context, reader assumptions, or external analysis.

- Given the interpretive nature of narrative analysis, it is essential to document the provenance of each statement within the ontology. This includes indicating whether a claim originates from the original fiction, a secondary source (e.g., literary criticism), or user-generated content. Ensuring clear attribution enhances data reliability and facilitates comparative research across different sources and interpretations.

4. Module Overview

4.1. Character Module

4.2. Relationship Module

4.3. Event Module

4.4. Setting Module

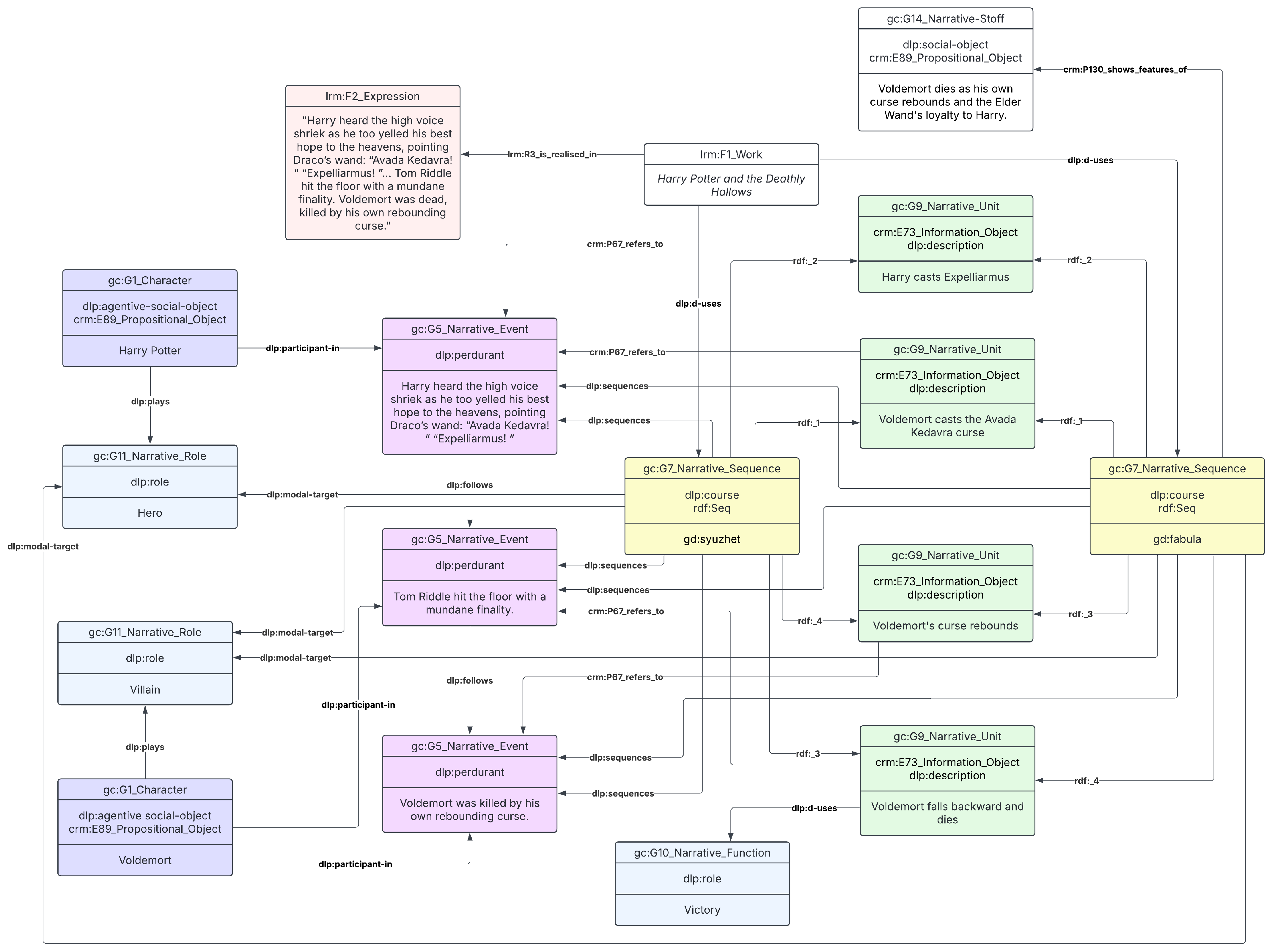

4.5. Narrative Module

4.6. Inference Module

4.7. Categorization

- Character features (G17_Character_Feature): Instances in this class can be further specified into “personality traits” (e.g., bravery), “physical attributes” (e.g., height), etc.

- Social relationships (G6_Social_Relationship): Relationships between characters can be categorized into types such as “friendship”, “romantic love”, “rivalry”, and so on.

- Roles (G6_Relationship_Role, G11_Narrative_Role): Relationship roles can be classified as “friend”, “lover”, “beloved”, etc. Narrative roles could be categorized as “archetypes”, including “Proppian dramatis personae” (e.g., hero, villain) or “commedia dell’arte characters” (Lea 1962).

- Narrative events (G5_Narrative_Event): Narrative events can be categorized into “change of state”, “process”, or “state”.

- Narrative sequences (G7_Narrative_Sequences): Sequences may be classified into a “hyleme sequence”, which can be further specified (has a narrower term) into “fabula”, and “syuzhet”.

- Narrative functions (G10_Narrative_Function): Types of narrative functions could be “Proppian functions”, “motifs” (e.g., Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (1955–1958), etc.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Ontometrics Evaluation

Appendix A.1. Base Metrics

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Axioms | 974 |

| Logical Axioms | 452 |

| Declared Classes | 49 |

| Total Classes | 49 |

| Declared Object Properties | 69 |

| Total Object Properties | 69 |

| Declared Data Properties | 1 |

| Total Data Properties | 1 |

| Total Properties (Object + Data) | 70 |

| Declared Individuals | 0 |

| Total Individuals | 0 |

| DL Expressivity | SHIN(D) |

Appendix A.2. Schema Metrics

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Attribute Richness | 0.020 |

| Inheritance Richness | 2.612 |

| Relationship Richness | 0.618 |

| Attribute-to-Class Ratio | 0.000 |

| Equivalence Ratio | 0.020 |

| Axiom-to-Class Ratio | 19.878 |

| Inverse Relations Ratio | 0.478 |

| Class-to-Relation Ratio | 0.146 |

Appendix A.3. Graph Metrics

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Absolute Root Cardinality | 22 |

| Absolute Leaf Cardinality | 28 |

| Absolute Sibling Cardinality | 45 |

| Absolute Depth | 88 |

| Average Depth | 1.630 |

| Maximum Depth | 3 |

| Absolute Breadth | 54 |

| Average Breadth | 3.000 |

| Maximum Breadth | 22 |

| Leaf Fan-Out Ratio | 0.571 |

| Sibling Fan-Out Ratio | 0.918 |

| Tangledness Ratio | 0.388 |

| Total Number of Paths | 54 |

| Average Number of Paths | 18 |

| 1 | See https://ontometrics.informatik.uni-rostock.de/ontologymetrics/ (accessed on 21 September 2025). |

| 2 | See https://github.com/oeg-upm/fair_ontologies (accessed on 21 September 2025). |

| 3 | See https://github.com/GOLEM-lab/golem-ontology/wiki (accessed on 21 September 2025). |

| 4 | See https://ontology.golemlab.eu/ (accessed on 21 September 2025). |

| 5 | GOLEM’s classes and properties are prefixed by the letter G and a progressive number, following CIDOC CRM and its extensions. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | The types of relationships are reported following AO3’s conventions: “&” is used for family and friends, while “/” is used for romantic and erotic relationships. |

References

- Abbott, H. Porter. 2008. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, H. Porter. 2019. Narrativity. In The Living Handbook of Narratology. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini, Alessio, Mari Carmen Suárez-Figueroa, Alessandro Adamou, Francesca Benatti, François Vignale, Guillaume Gravier, and Lucia Lupi. 2021. Understanding the phenomenology of reading through modelling. Semantic Web 12: 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, Kristin J., and Karen S. Rook. 2013. Social relationships. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Cham: Springer, pp. 1838–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke. 1997. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartalesi, Valentina, Carlo Meghini, and Daniele Metilli. 2016. Steps towards a formal ontology of narratives based on narratology. In 7th Workshop on Computational Models of Narrative (CMN 2016). Wadern: Schloss Dagstuhl–Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik, pp. 4:1–4:10. [Google Scholar]

- Bartalesi, Valentina, Carlo Meghini, and Daniele Metilli. 2017. A conceptualisation of narratives and its expression in the crm. International Journal of Metadata, Semantics and Ontologies 12: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalesi, Valentina, Gianpaolo Coro, Emanuele Lenzi, Pasquale Pagano, and Nicolò Pratelli. 2023. From unstructured texts to semantic story maps. International Journal of Digital Earth 16: 234–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekiari, Chryssoula, George Bruseker, Erin Canning, Martin Doerr, Philippe Michon, Christian-Emil Ore, Stephen Stead, and Athanasios Velios. 2024. Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/Version/version-7.3.1 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Beretta, Francesco. 2024. Semantic data for humanities and social sciences (sdhss): An ecosystem of cidoc crm extensions for research data production and reuse. arXiv arXiv:2402.07531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Peter. 2018. A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bottazzi, Emanuele, and Roberta Ferrario. 2009. Preliminaries to a dolce ontology of organisations. International Journal of Business Process Integration and Management 4: 225–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, Michael. 1987. Intention, Plans, and Practical Reason. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi, Mario, Rossana Damiano, Vincenzo Lombardo, Antonio Pizzo, and Dario Sergi. 2011. Integrating commonsense knowledge into the semantic annotation of narrative media objects. Paper presented at AI* IA 2011: Artificial Intelligence Around Man and Beyond: XIIth International Conference of the Italian Association for Artificial Intelligence, Palermo, Italy, September 15–17; Proceedings 12. pp. 312–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ceusters, Werner, and Barry Smith. 2015. Aboutness: Towards foundations for the information artifact ontology. Paper presented at Sixth International Conference on Biomedical Ontology (ICBO), Lisbon, Portugal, July 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi, Snigdha, Shashank Srivastava, Hal Daume, III, and Chris Dyer. 2016. Modeling evolving relationships between characters in literary novels. Paper presented at AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, February 12–17, vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Damiano, Rossana, and Antonio Lieto. 2013. Ontological representations of narratives: A case study on stories and actions. Open Access Series in Informatics 32: 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, Rossana, Vincenzo Lombardo, and Antonio Pizzo. 2019. The ontology of drama. Applied Ontology 14: 79–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, Martin. 2003. The cidoc conceptual reference module: An ontological approach to semantic interoperability of metadata. AI Magazine 24: 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Doerr, Martin, and Dolores Iorizzo. 2008. The dream of a global knowledge network—A new approach. Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 1: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, Paul. 2009. Ontology Modularization: Principles and Practice. Ph.D. thesis, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK. [Google Scholar]

- d’Aquin, Mathieu. 2011. Modularizing ontologies. In Ontology Engineering in a Networked World. Berlin: Springer, pp. 213–33. [Google Scholar]

- d’Aquin, Mathieu, Anne Schlicht, Heiner Stuckenschmidt, and Marta Sabou. 2009. Criteria and evaluation for ontology modularization techniques. In Modular Ontologies: Concepts, Theories and Techniques for Knowledge Modularization. Berlin: Springer, pp. 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, Jens, Fotis Jannidis, and Ralf Schneider. 2011. Characters in Fictional Worlds: Understanding Imaginary Beings in Literature, Film, and Other Media. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Gammelgaard, Lasse Raaby, Stefan Iversen, Louise Brix Jacobsen, James Phelan, Richard Walsh, Henrik Zetterberg-Nielsen, and Simona Zetterberg-Nielsen. 2022. Fictionality and Literature: Core Concepts Revisited. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi, Aldo, and Peter Mika. 2003. Understanding the semantic web through descriptions and situations. In OTM Confederated International Conferences “On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems". Berlin: Springer, pp. 689–706. [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi, Aldo, and Valentina Presutti. 2009. Ontology design patterns. In Handbook on Ontologies. Berlin: Springer, pp. 221–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gangemi, Aldo, Nicola Guarino, Claudio Masolo, Alessandro Oltramari, and Luc Schneider. 2002. Sweetening ontologies with dolce. In International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management. Berlin and Heidelberg, Springer: pp. 166–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gärdenfors, Peter. 2004. Conceptual spaces as a framework for knowledge representation. Mind and Matter 2: 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gius, Evelyn, and Michael Vauth. 2022. Towards an event based plot model. A computational narratology approach. Journal of Computational Literary Studies 1: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, Nicola, and Giancarlo Guizzardi. 2015. “we need to discuss the relationship”: Revisiting relationships as modeling constructs. Paper presented at Advanced Information Systems Engineering: 27th International Conference, CAiSE 2015, Stockholm, Sweden, June 8–12; Proceedings 27. pp. 279–94. [Google Scholar]

- Guizzardi, Giancarlo, Terry Halpin, Giancarlo Guizzardi, and Terry Halpin. 2008. Ontological foundations for conceptual modelling. Applied Ontology 3: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, Janna, and Stefan Schulz. 2019. Representing literary characters and their attributes in an ontology. Paper presented at Joint Ontology Workshops 2019, Episode V: The Styrian Autumn of Ontology, Graz, Austria, September 23–25; Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2518/paper-WODHSA4.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Huang, Zhaoyan, and Tao Xu. 2022. Research on knowledge management of intangible cultural heritage based on linked data. Mobile Information Systems 2022: 3384391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). 2023. Information and Documentation—A Reference Ontology for the Interchange of Cultural Heritage Information. ISO Standard No. 21127:2023. Geneva: ISO. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/85100.html (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Jacke, Janina. 2025. Operationalization and interpretation dependence in computational literary studies. Journal of Computational Literary Studies 4: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannidis, Fotis, Matías Martínez, John Pier, Wolf Schmid, Peter Hühn, John Pier, Wolf Schmid, and Jörg Schönert. 2009. Handbook of Narratology. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2012. Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell, Michael O., K. Faith Lawrence, Mischa M. Tuffield, Adam Prugel-Bennett, David E. Millard, Mark S. Nixon, and Nigel Shadbolt. 2005. Ontomedia: An ontology for the representation of heterogeneous media. Paper presented at Workshop on Multimedia Information Retrieval, ACM SIGIR, Salvador, Brazil, August 15–19; Available online: https://web-archive.southampton.ac.uk/eprints.aktors.org/426/01/ISWC05.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Kukkonen, Karin. 2019. Plot. In The Living Handbook of Narratology. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, Kathleen Marguerite. 1962. Italian Popular Comedy: A Study in the Commedia dell’Arte, 1560–1620 with Special Reference to the English Stage. Kent: Russell & Russell, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lotman, Ju M. 1977. The dynamic model of a semiotic system. Semiotica 21: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, William C., and Sandra A. Thompson. 1987. Rhetorical structure theory: Description and construction of text structures. In Natural Language Generation: New Results in Artificial Intelligence, Psychology and Linguistics. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Mascardi, Viviana, Valentina Cordì, and Paolo Rosso. 2007. A comparison of upper ontologies. In Woa. Genova: Università degli Studi di Genova, vol. 2007, pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Masolo, Claudio, Stefano Borgo, Aldo Gangemi, Nicola Guarino, and Alessandro Oltramari. 2002. Wonderweb Deliverable d17. Science Direct Working Paper No S1574-034X (04). Rochester: SSRN, pp. 70214–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meghini, Carlo, and Martin Doerr. 2018. A first-order logic expression of the cidoc conceptual reference model. International Journal of Metadata, Semantics and Ontologies 13: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghini, Carlo, Valentina Bartalesi, and Daniele Metilli. 2021. Representing narratives in digital libraries: The narrative ontology. Semantic Web 12: 241–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinong, Alexius. 1904. Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie. Lepzig: JA Barth. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, Peter, and Aldo Gangemi. 2016. Descriptions of social relations. Benefits 1: 14. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone, Arturo, and Mitsuru Ishizuka. 2006. Storytelling ontology model using rst. Paper presented at 2006 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Intelligent Agent Technology, Hong Kong, China, December 18–22; pp. 163–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pannach, Franziska. 2023. “orpheus came to his end by being struck by a thunderbolt”: Annotating events in mythological sequences. Paper presented at 17th Linguistic Annotation Workshop (LAW-XVII), Toronto, ON, Canada, July 23; pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pannach, Franziska, Caroline Sporleder, Wolfgang May, Aravind Krishnan, and Anusharani Sewchurran. 2021. Of lions and yakshis: Ontology-based narrative structure modelling for culturally diverse folktales. Semantic Web 12: 219–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passalacqua, Franco, and Federico Pianzola. 2016. Epistemological problems in narrative theory: Objectivist vs. constructivist paradigm. In Narrative Sequence in Contemporary Narratology. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, pp. 195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Peinado, Federico, Pablo Gervás, and Belén Díaz-Agudo. 2004. A description logic ontology for fairy tale generation. Paper presented at Workshop on Language Resources for Linguistic Creativity, LREC, Torino, Italy, May 29, vol. 4, pp. 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, Axel, and Nils Reiter. 2022. From Concepts to Texts and Back: Operationalization as a Core Activity of Digital Humanities. Journal of Cultural Analytics 7: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, Andrew, Richard Jean So, and David Bamman. 2021. Narrative theory for computational narrative understanding. Paper presented at 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, November 7–11; pp. 298–311. [Google Scholar]

- Presutti, Valentina, Enrico Daga, Aldo Gangemi, and Eva Blomqvist. 2009. eXtreme design with content ontology design patterns. Paper presented at 2009 International Conference on Ontology Patterns, Washington DC, USA, October 25–29; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Propp, Vladimir. 1968. Morphology of the Folktale. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, Pat, Patrick Le Bœuf, and Maja Žumer. 2017. IFLA Library Reference Model: A Conceptual Model for Bibliographic Information; Technical Report. Revised After Worldwide Review, Endorsed by the IFLA Professional Committee. The Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). Available online: https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/frbr-lrm/ifla-lrm-august-2017_rev201712.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Riva, Patrizia, and Maja Zumer. 2017. Frbroo, the Ifla Library Reference Model, and Now lrmoo: A Circle of Development. Technical Report. The Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). [Google Scholar]

- Rowling, Joanne K. 2000. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Rowling, Joanne K. 2007. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Ruy, Fabiano B., Giancarlo Guizzardi, Ricardo A. Falbo, Cássio C. Reginato, and Victor A. Santos. 2017. From reference ontologies to ontology patterns and back. Data & Knowledge Engineering 109: 41–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Marie-Laure. 2019. Space. In The Living Handbook of Narratology. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., Béatrice Markhoff, and Perrine Pittet. 2020. Ontological analysis and modularization of cidoc-crm. In Formal Ontology in Information Systems. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 107–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfilippo, Emilio M., Claudio Masolo, Alessandro Mosca, and Gaia Tomazzoli. 2024. Operationalizing scholarly observations in owl. Paper presented at Semantic Web and Ontology Design for Cultural Heritage 2024, Proceedings of the Fourth Edition of the International Workshop on Semantic Web and Ontology Design for Cultural Heritage, Tours, France, October 30–31, vol. 3809, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Schöch, Christof, Maria Hinzmann, Julia Röttgermann, Katharina Dietz, and Anne Klee. 2022. Smart modelling for literary history. International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 16: 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, Luca, Federico Pianzola, and Franziska Pannach. 2025. Grounding the Development of an Ontology for Narrative and Fiction. Semantic Web—Interoperability, Usability, Applicability. Available online: https://www.semantic-web-journal.net/content/grounding-development-ontology-narrative-and-fiction (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Segers, Roxane, Tomasso Caselli, and Piek Vossen. 2018. The circumstantial event ontology (ceo) and ecb+/ceo: An ontology and corpus for implicit causal relations between events. Paper presented at Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Miyazaki, Japan, May 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shklovsky, Viktor. 1917. Art as technique. Literary Theory: An Anthology 3: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Swartjes, Ivo, and Mariët Theune. 2006. A fabula model for emergent narrative. In International Conference on Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment. Berlin and Heidelberg, Springer: pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, Francesca. 2018. Modellieren in den Digitalen Geisteswissenschaften: Konzeptuelle Datenmodelle und Wissensorganisation für das kulturelle Erbe. Historical Social Research Supplement 31: 170–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, Francesca. 2020. Digital humanities e organizzazione della conoscenza: Una pratica di insegnamento nel LODLAM. AIB Studi 60: 411–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffield, Mischa M., Dave E. Millard, and Nigel R. Shadbolt. 2006. Ontological approaches to modelling narrative. Paper presented at 2nd AKT DTA Symposium, Aberdeen, Scotland, January 1. [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan, Udaya, and Biswanath Dutta. 2021. Models for narrative information: A study. arXiv arXiv:2110.02084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser Solissa, Noa, Andreas van Cranenburgh, and Federico Pianzola. 2025. Event detection between literary studies and NLP. A survey, a narratological reflection, and a case study. Paper presented at 4th Annual Conference of Computational Literary Studies, Krakow, Poland, July 3–4, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Vossen, Piek, Tommaso Caselli, and Roxane Segers. 2021. A narratology-based framework for storyline extraction. In Computational Analysis of Storylines: Making Sense of Events. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 125, pp. 125–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Xiaoyam, and Federico Pianzola. 2025. Fans Reconstruct Heroes: Modeling Fictional Characters in Participatory Culture. Semantic Web—Interoperability, Usability, Applicability. Available online: https://www.semantic-web-journal.net/content/fans-reconstruct-heroes-modeling-fictional-characters-participatory-culture (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Zetterberg Gjerlevsen, Simona. 2016. Fictionality. In The Living Handbook of Narratology. Edited by Peter Hühn, Jan Christoph Meister, John Pier and Wolf Schmid. Hamburg: Hamburg University. [Google Scholar]

- Zgoll, Christian. 2020. Myths as polymorphous and polystratic erzählstoffe. In Mythische Sphärenwechsel: Methodisch neue Zugänge zu antiken Mythen in Orient und Okzident. Berlin: De Gruyter Brill, pp. 9–82. [Google Scholar]

| Ontology | Narrative Domain | Narrative Concepts | Design Language | Ontology Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storytelling Ontology Model (Nakasone and Ishizuka 2006) | General | Event, act, scene, agent, role, agent’s role | OWL | No |

| OntoMedia (Jewell et al. 2005) | General | Entity (e.g., characters, objects), entity traits, events | OWL | No |

| The Fabula Model (Swartjes and Theune 2006) | General | Character, character’s goal, action, character’s mental state, perception, event | OWL | No |

| Character Ontology (Hastings and Schulz 2019) | General | Character, character features | OWL | BFO |

| Narrative Ontology (NOnt) (Meghini et al. 2021) | General | Narrative, fabula events, narration, reference | OWL | CIDOC CRM, FRBRoo, OWL Time, DOLCE |

| Circumstantial Event Ontology (Segers et al. 2018), (Vossen et al. 2021) | General | Event, agent, situation | OWL | SUMO |

| Drammar ontology (Damiano et al. 2019) | Drama | Endurant (agent, object), perdurant (action, event), mental state | OWL | DOLCE |

| Archetype Ontology (Damiano et al. 2013) | Artworks | Archetypes, character, object, event, action, setting | OWL | FRBRoo |

| ProppOnto (Peinado et al. 2004) | Folktale | Character, setting, narrative function | OWL | No |

| ProppOntology (Pannach et al. 2021) | Folktale | Narrative function, character, character’s role | OWL | No |

| Prefix | Name | URI |

|---|---|---|

| rdf | RDF Syntax | http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns# |

| dlp | DOLCE + DnS Ultralite | http://www.ontologydesignpatterns.org/ont/dlp/ |

| owl | OWL | http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl# |

| skos | SKOS | http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core# |

| schema | Schema.org | https://schema.org/ |

| crm | CIDOC CRM | http://www.cidoc-crm.org/cidoc-crm/ |

| lrm | IFLA LRMoo | http://iflastandards.info/ns/lrm/lrmoo/ |

| gc | Golem | https://ontology.golemlab.eu/ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pianzola, F.; Cheng, L.; Pannach, F.; Yang, X.; Scotti, L. The GOLEM Ontology for Narrative and Fiction. Humanities 2025, 14, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14100193

Pianzola F, Cheng L, Pannach F, Yang X, Scotti L. The GOLEM Ontology for Narrative and Fiction. Humanities. 2025; 14(10):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14100193

Chicago/Turabian StylePianzola, Federico, Luotong Cheng, Franziska Pannach, Xiaoyan Yang, and Luca Scotti. 2025. "The GOLEM Ontology for Narrative and Fiction" Humanities 14, no. 10: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14100193

APA StylePianzola, F., Cheng, L., Pannach, F., Yang, X., & Scotti, L. (2025). The GOLEM Ontology for Narrative and Fiction. Humanities, 14(10), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/h14100193