1. Introduction

The critical conversation around hybridity in American poetry in the 2010s largely centered on responses to the publication of

American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry, edited by Cole Swensen and David St. John (

Swensen and St. John 2009). In her introduction, Swensen describes hybrid poetry as “rich writings that cannot be categorized and that hybridize core attributes of previous ‘camps’ in diverse and unprecedented ways” (xvii). These camps have been variously described as “the cooked” and “the raw” by Robert Lowell in the 1950s; Official Verse Culture and Language poetry by Charles Bernstein in the 1980s (

Bernstein 1986, p. 247); and the School of Quietude and post-avant poetry by Ron Silliman in the early 21st century (

Biddinger and Gallaher 2011, p. 117). The

American Hybrid contributors combine these approaches, according to Swensen: “today’s writers often take aspects from two or more [traditions] to create poetry that is truly postmodern in that it’s an unpredictable and unprecedented mix” (xxi).

Criticism of Swensen and St. John’s framing of hybrid poetry has been well documented.

1 A few strands of these critiques are important to this essay: first, that the hybrid poetry in

American Hybrid is “ornamental and fundamentally apolitical,” more invested in contesting the idea of competing poetic schools than in opposing “any immediately graspable power structure or social injustice” (

Robbins 2014, p. 5); second, that the editors ignore longstanding theories and bodies of literature of hybridity by non-white scholars and poets (

Santos Perez 2011;

Chan 2018); and third, that they overlook decades-long traditions of mixed-genre and formally innovative writing by women (Robbins). In

American Hybrid Poetics: Gender, Mass Culture, and Form,

Amy Moorman Robbins (

2014) addresses the third oversight by offering an in-depth reframing of hybridity around the work of 20th- and 21st-century women poets. In the essay “Whitewashing American Hybrid Aesthetics,”

Craig Santos Perez (

2011) skewers

American Hybrid—which, he argues, would have been more accurately titled “White American Hybrid”—and catalogs many Native, Asian American, and Latinx scholars and writers whose work has theorized and engaged with hybridity for decades.

2 The problem with

American Hybrid’s framing of hybridity, then, is not that it mischaracterizes the trend of mixing traditional and experimental approaches; the problem is that, in naming this poetics “hybrid,” the editors disregard multiple rich traditions of socially engaged hybridity in American poetry and instead enshrine in a Norton anthology a version of hybridity by mostly white writers who mix aesthetics for largely apolitical reasons. In other words, the anthology defangs hybridity.

This essay recenters political traditions of poetic hybridity theorized and practiced by women and writers of color as it examines two texts that participate in and document a significant moment of feminist activism in U.S. and global poetry communities from 2014 to 2017. The first text is the collaboratively, anonymously authored “No Manifesto for Poetry Readings and Listservs and Magazines and ‘Open Versatile Spaces Where Cultural Production Flourishes,’” published in a 2015

Chicago Review forum on sexism and sexual assault in literary communities (

No Manifesto 2015). The second is

YOU DA ONE by Jennif(f)er Tamayo, a book of poetry and visual art first released in 2014 by Coconut Books and then republished in a drastically altered edition by Noemi Press in 2017 (

Tamayo 2014,

2017). I pair

YOU DA ONE and “No Manifesto” first because they are intertexts: Tamayo was one of the coauthors of the manifesto, as the introductory note to the second edition of

YOU DA ONE indicates; this edition also reprints excerpts from “No Manifesto” and borrows its form to create new poems. Beyond shared language and authorship, “No Manifesto” and

YOU DA ONE also share tactics: they embrace collectivity, incongruity, and nonresolution as hybrid poetic modes of resistance while rejecting the conventions of liberal discourse—individuality, cohesion, and closure—as the proper ways to create poetry or do feminism. Precursors to the #MeToo movement, these texts expose the effects of sexism and sexual violence reverberating through poetry communities without attempting to speak from a unified standpoint or to reconcile the damage that has been done.

“No Manifesto” and

YOU DA ONE can be read as instances of the turn toward “a new era, the poetry of social engagement” described by

Cathy Park Hong (

2015) in an article in

The New Republic and by the editors of two anthologies published soon after. Hong describes a literary landscape where “[p]oetry is becoming progressively fluid, merging protest and performance into its practice.” These poetic texts flow into contexts beyond the page: protests, political organizing meetings, or social media, for example. In

The News from Poems: Essays on the 21st-Century American Poetry of Engagement, Jeffrey Gray and Ann Keniston (

Gray and Keniston 2016) describe a “public poetry” that embraces long-derided didacticism and embodies the idea that “writing about the world is no longer different from writing about the self” (3). Michael Dowdy, in his introduction to

American Poets in the 21st Century: Poetics of Social Engagement (2018), examines poetry that is “not narrowly but rather capaciously political” (

Dowdy and Rankine 2018, p. 4) by writers “whose poetic practices engage with and seek to transform social reality” (2). Socially engaged poetry is not only experienced on the page but also does work in the social and material worlds.

YOU DA ONE and “No Manifesto” are poetic texts that incite social change in literary communities and activist circles by directly confronting sexual violence, by reimagining how poetry can speak out against injustice, and by documenting allegations and activist efforts. They certainly reflect the above definitions of socially engaged poetics. I choose to hold on to the term “hybrid” as well because I understand the hybridity of these texts in terms of their political engagements. As both works of poetry and forms of protest, their language and methods draw not only from poetic traditions but from types of writing that are meant to make things happen in the real world—most notably, social media posts and the manifesto. It is through their hybridity that they intervene into the social world in powerful ways. Further, I foreground hybridity out of the sense that scholarship has not yet fully brought to light overlooked frameworks of hybridity by women and writers of color, and that much 21st-century poetry of social engagement can be better understood in light of these traditions.

3 This essay defines hybridity as a literary representation of cultural positions forcefully imposed upon subjects. This framework synthesizes the work of several poets and theorists, including Gloria Anzaldúa, Alfred Arteaga, and Lisa Lowe. For Tamayo and the “No Manifesto” authors, hybridity is not a purely aesthetic mixing—not the “the ‘free’ oscillation between or among chosen identities” (82) or poetic camps—but rather an effect “produced by the histories of uneven and unsynthetic power relations,” as

Lisa Lowe (

1996) puts it in her oft-cited book on Asian American immigrants’ cultural politics (67). In the first few pages of

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza,

Anzaldúa (

1987) makes the pain of her hybridized cultural position clear when she describes a “1950 mile-long open wound/dividing a pueblo, a culture, /running down the length of my body/staking fence rods in my flesh” (24). Hybridity is what results from the wound of the borderlands, which crosses and divides the land, body, and culture. In

Chicano Poetics,

Alfred Arteaga (

1997) observes that Anzaldúa’s hybrid mestiza consciousness “is forged amid political struggle” and “always implicated in choice, in the tyranny of history, and in the arbitrariness of the hegemony” (

Arteaga 1997, p. 153). In an essay on Latino identity in poetry,

Maria Damon (

1998) describes poesis “as the making of a resistant (and simultaneously permeable) hybridity, the making of a border sensibility” (4). Hybridity marks the wound that remakes the subject, forging a new consciousness that understands the workings of power and develops strategies for resistance.

In “No Manifesto” and

YOU DA ONE, hybridity is born out of the domination of sexism, sexual violence, and state violence. By using hybrid tactics to confront the workings of power, the authors continue a lineage of hybridity in American poetry that has always been political, incongruous, and unruly.

4 Like Anzaldúa, the authors of “No Manifesto” and Tamayo “write in an age of the dismantling of heterosexist patriarchies; they write to break apart trenchant rule, order, modes of being” (

Arteaga 1997, p. 152–53). Their hybridity simultaneously marks the violence of imperialist capitalist white supremacist cis-hetero-patriarchy and directly performs feminist resistance. Unlike their forebears, however, “No Manifesto” and the second edition of

YOU DA ONE draw on the power of collectivity at the heart of activism and collaboratively authored texts.

Mark Wallace (

2011), in his essay in a “Hybrid Aesthetics and Its Discontents” forum, understands poetic hybridity, even in single-authored texts, as an aesthetic mode that sparks “the fear that democracy might actually be a form of chaos” (123). Tamayo and the authors of the manifesto embrace this so-called “chaos” in form and content, saying “no” to the status quo and instead speaking from an unruly, and sometimes anonymous, collectivity. If hybridity “marks the history of survival within relationships of unequal power and domination” (

Lowe 1996, p. 67), then working and writing together in a collective becomes a survival tactic in this time of heightened activism when “a momentary ‘we’ screamed NO” (

Tamayo 2017, p. 7).

5Part literary criticism, part social history, my critical approach in this essay is hybrid as well. I move between literary analysis and social narratives, including my own memory of certain events, in order to illustrate the way incidents in poetry communities shaped these texts, and the work the authors and texts did in the real world, in turn. I begin with an overview of feminist activism in poetry communities in 2014–2016, some of which is documented in “No Manifesto” and other contributions to the Chicago Review forum. I then go on to read “No Manifesto” as a text of dissonant collective refusal. These discussions provide context for my examination of Tamayo’s YOU DA ONE in the following section, making clear the matrix of sexual violence and activism out of which the book performs its acts of resistance. In their refusal to play by the rules of poetic or social discourse and their insistence on alternative ways of being, writing, and entering the public sphere, these socially engaged, hybrid poetic texts disrupted the status quo in material ways.

2. “No Manifesto” and Activism in Poetry Communities in the #MeToo Moment

“No Manifesto,” YOU DA ONE, and the feminist activism discussed in this essay were early manifestations of the global resistance to sexual violence that came to be known as the #MeToo movement. Begun by activist Tarana Burke in 2006 and popularized by actress Alyssa Milano on Twitter eleven years later, #MeToo erupted most forcefully in the fall of 2017, when millions of people took to social media to share their stories as survivors of sexual assault, sexual harassment, and misogyny, eventually prompting institutions in Hollywood, government, the media, and beyond to remove some abusers from positions of power. The history of poetry communities’ contributions to the waves of resistance that swelled into #MeToo remains largely unwritten except in the documents I discuss here.

Tamayo, besides being the author of YOU DA ONE and cowriting the “No Manifesto,” also incited and organized much of the activism in poetry communities in this time period—especially in New York City, where she lived, and also through coordination with poets in Chicago, the Bay Area, and elsewhere. As her former editor (the small press I cofounded, Switchback Books, published her first book) and later her friend, I read, witnessed, and sometimes worked alongside Tamayo’s poetry, performance, visual art, and activist work in these years, which has given me a more intimate understanding of the social history surrounding these texts.

On 30 September 2014, Tamayo put out a call to action on Facebook that inaugurated a year of activist efforts by poets in New York. The post is reprinted in the second edition of YOU DA ONE:

I remember seeing the post in my feed that day and experiencing it as an event in itself: a shrill whistle calling off business as usual. The phrase “Enough Is Enough” would go on to lend itself to the name of a group of poet-activists who organized feminist interventions in New York and over the internet.

6 In the fall of 2014, dozens of women poets and allies gathered: first in each other’s homes; then at Berl’s Brooklyn Poetry Shop for the semi-closed meeting on 26 October that Tamayo announced above, where around 35 women confidentially shared experiences of sexism and sexual violence; and soon after at a public town hall at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church on November 6, where Enough is Enough distributed a “Call to Action” handout that included “preliminary suggestions for making our spaces safer, more equitable, and more liberatory” (

Call to Action 2015, p. 202).

At these consciousness-raising meetings, strategy sessions, and town halls, poet-activists shared information, identified problems and perpetrators, and discussed ways to address an overwhelming number of issues. We were learning from each other that women were getting drugged at poetry readings, that a male poet had shoved a younger woman poet “as a joke,” that a well-respected poetry organization was assigning an older man with a known history of harassment as a mentor to young women, that booksellers and librarians were harassing women through private messages on social media platforms, and more. The meetings added up to a collective recognition that misogyny and sexual violence were so deeply embedded in our literary spaces as to define them, and that rape culture was alive and well in our professedly progressive poetry communities. In other words, poets in New York in the fall of 2014 were beginning to see what the culture at large began to apprehend in the fall of 2017, when anyone who spent time on social media witnessed—and sometimes realized for the first time—that almost every woman they knew, and many people of all genders, had been impacted by sexual violence.

Amidst this sobering acknowledgment, there was a sense of clarity, too: our individual experiences puzzled together into a larger picture. As we reckoned with the underbellies of the literary circles we moved in, some felt that their personal realities had been validated—that they hadn’t been crazy or paranoid to have felt that their communities had ignored or played down past incidents of sexism and sexual violence. At the same time, we felt destabilized and overwhelmed, even defeated. It seemed as if every literary relationship we held—with small press or literary magazine editors, reading series curators, or fellowship committee members—was somehow complicit. How could we stand up to all of it? How could we pick our battles when there were so many fronts to attend to, from the interpersonal to the institutional?

While the Enough is Enough collective was organizing meetings and actions in New York, parallel interventions were taking place in other literary communities, most visibly in the Bay Area and in Chicago. Some of these activities are discussed in the forum “Sexism and Sexual Assault in Literary Communities” in the Autumn 2014–Winter 2015 issue of

Chicago Review.

7 Although the forum’s original intention was to collect responses to “instances of sexist and misogynistic writing from prominent male figures and […] allegations of sexual assault from women writers” in the Alt-Lit communities in New York and the Bay Area, the editors eventually expanded the forum to include writing on sexism and sexual violence in literary communities beyond Alt-Lit, while still staying focused on “the bicoastal epicenters of American innovative writing” (

Peart and Wilding 2015, p. 191).

8The forum includes the twelve-page “No Manifesto for Poetry Readings and Listservs and Magazines and ‘Open Versatile Spaces Where Cultural Production Flourishes’”

9 (

No Manifesto 2015), written collaboratively by an anonymous “crowd of feminists” based in the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Australia—who, as they note in their signature, are “lacking consensus and okay with that” (233). The manifesto opens by saying “no” to sexism, sexual violence, and gender discrimination:

No to rape

No to denying rape

No to gaslighting

No to drugging people at readings

No to sexual violence

No to relentlessly sexualizing

No to relentlessly gendering

No to misgendering

No to gender (221)

Braiding together the simultaneous activism that was taking place in poetry communities around the world, “No Manifesto” catalogs far-reaching grievances, from systemic inequities to specific events in particular communities, explicitly saying “no” to these incidents, to inadequate or harmful attempts to respond to them, and to the larger cultural norms that allowed them to take place.

The challenges of banding together around a shared agenda when undertaking collaborative writing and activist work become visible as the manifesto twists and turns on itself like a Möbius strip, saying “no” to one concept only to quickly follow up with a rejection of its opposite:

No to decorum

No to forums

No to allies

No to enemies

No to individuals aren’t the institution

No to individuals are the institution

No to gossip shaming

No to not speaking up

No to not naming names

No to blaming those who speak and those who name

No to not realizing that when naming names things might go wrong

No to neglecting racial politics as you name names

No to neglecting sexual and/or gender politics as you name names

No to using identity politics to shut down the naming of names

No to social norms and justice systems that don’t keep people safe so that naming

names is a necessary resource (221–22)

“No Manifesto” performs the crowd of feminists’ dissensus regarding which issues are most urgent, which responses are most appropriate, and which tactics are most effective. The poem-manifesto refuses to cohere into a single voice or point of view and instead incorporates disagreement, as we can see in the question of whether individuals can be separated from the institutions to which they belong. As the authors bring to light implicit social norms around acceptable responses to sexism and sexual violence—for example, the assumption that one shouldn’t name the names of alleged perpetrators—they also fold in the possibility that “things might go wrong” when stepping outside these norms (221).

Structurally, “No Manifesto” makes room for this dissonance through its use of anaphora: In the litany of “No”s stacked along the left margin, no single claim rises in importance above another. It is a repetition that is also a leveling. The form of “No Manifesto” makes clear that what unites these voices, despite manifold and sometimes competing agendas, is their “No”—their oppositional stance to current cultural conditions.

10 Over the course of twelve pages, the crowd of feminists opposes a vast range of institutions, frameworks, behaviors, and incidents. Their response to the question we faced in our early organizing as Enough Is Enough—How could we pick our battles when there were so many fronts to attend to, from the interpersonal to the institutional?—seems to be: Put it all in. Ultimately, the litany of “No”s widens into a rejection of the conditions of the poetry world as a microcosm of a larger misogynist culture:

No to sending Elizabeth Ellen’s “Open Letter to the Internet” to the UK Poetry List

and calling it an “intervention”

No to cross-examining a woman on her account of rape, to replicating the discourse

and modes of the legal system that regularly fails women

No to a culture that discounts women’s statements about their experience (224)

Far from the freely or arbitrarily chosen hybridity of mixing different poetic approaches, the hybridity of “No Manifesto” emerges from what Anzaldúa calls an “open wound”—the wounds of widespread sexual violence and misogyny—and produces what Lowe calls a “cultural object” in the form of a poem-manifesto that documents and protests “the histories of uneven and unsynthetic power relations” (67). The work of “No Manifesto” is not to present a coherent politics but to catalog wounds and call out asymmetries of power in poetry communities as comprehensively as possible. The manifesto’s hybridity—its incongruities, contradictions, and moments of nonresolution—marks the way the cultural positions of the crowd of feminists, including their dissensus around these positions, have been violently imposed upon them. Their multifarious subjectivities do not harmonize into a chorus but instead shout in a cacophony of speech acts and ethical positions.

When putting together the

Chicago Review forum that ultimately included “No Manifesto,” editors Andrew Peart and Chalcey Wilding (

Peart and Wilding 2015) had, by their own account, “reached out initially only to individuals, which read as an affront to the activism around sexism and sexual assault undertaken by feminist collectives in the Bay Area, New York, and abroad,” and soon the forum “became controversial” (194, 193). The editors go on to acknowledge the biases embedded in their initial call:

We were asking for contributions to a forum, which seemed wrong given the questions we were asking: as if a discursive space modeled on the ideals of a liberal public sphere—rationality, objectivity, deliberative consensus-building—could do anything but a disservice to problems experienced viscerally by real bodies. (194)

“No Manifesto” names and rejects this original call for rational, objective statements written by individuals:

No to Chicago Review’s only inviting individuals to participate in this forum

No to Chicago Review’s not inviting NYC’s Enough is Enough

No to Chicago Review’s not inviting the collective of women who shut down the UK poetry listserv

No to Chicago Review’s not inviting the UK feminist poets group proto-form (230)

As they worked to rectify these oversights, Peart and Wilding widened the call: they “accepted statements on behalf of activist organizations, public documents previously circulated among feminist cadres and those in solidarity with them, and an anonymous multi-authored manifesto” (194). These are documents that “adopt modes other than the brief discursive statements” originally solicited; that decline to engage in “cool and dispassionate discussions of those problems”; and that, in aggregate, “[point] to different, better discussions than the one [the editors] had set up” (193). Peart and Wilding ended up with a forum “loosely mediated enough to allow plenty of room for dissensus to emerge and not resolve itself” (194). In other words, the forum itself eventually adopted an editing philosophy that mirrored the hybrid, multi-authored dissonance of the “No Manifesto.”

It is to their credit that Peart and Wilding revised their editorial process. But what is even more striking is how the crowd of feminists refused the terms of the initial call, pushing back against the discursive space offered (“No to decorum/No to forums”) and reshaping who gets to speak in a public literary forum, and how. By demanding to voice its grievances differently—anonymously, collectively, and in the form of a poem-manifesto—“No Manifesto” perhaps elicits “the anti-democratic fear that too many points of view equals a chaotic loss of defined value” prompted by certain types of hybrid writing (

Wallace 2011, p. 125). What it puts forth instead looks something like the dynamic unruliness of democracy—of a collective social body working toward a larger good, feminist justice, rather than getting mired in the details of smaller disagreements. Like other socially engaged poems, the manifesto expands the available “sites, forms, modes, vehicles, and inquiries for entering the public sphere, contesting injustices, and reimagining dominant norms, values, and exclusions” (

Dowdy and Rankine 2018, p. 6). By refusing the terms of the initial call, which asked individuals to present cohesive points of view, and instead inviting themselves to the conversation on their own terms, the crowd of feminists disrupted and transformed the forum’s discursive possibilities, turning it into an activist space that welcomed “feminist cadres”—including Enough is Enough—whose documents were eventually included in the forum.

3. The Restaging of Jennif(f)er Tamayo’s YOU DA ONE

The first edition of Jennif(f)er Tamayo’s

YOU DA ONE, published in 2014 by Coconut Books, is a multigenre, multimedia, and multilingual book of poetry that incorporates digital images and song lyrics, critical theory and spam, and English and Spanish. Its hybridity extends across all of these elements, and the experience of reading

YOU DA ONE emphasizes the simultaneity of registers, languages, references, text, image, music, and more. Further, the book has a life beyond the page in the realm of performance and video, as a

Publishers Weekly review highlights: “Tamayo notes a number of live performances of the text, which lends stability to the book on a whole, even as it mirrors the disjointed aesthetics of the internet and contemporary communications” (

YOU DA ONE 2014). The “disjointed aesthetics” or hybrid poetics of the 2014 edition of

YOU DA ONE perform not only the frenetic feeds of social media but also the ruptures caused by traumatic events related to family and migration. The book tells the story of a woman—referred to as “the daughter,” “Jennifer Tamayo,” and “JT”—going back to the country of her birth and early childhood, Colombia, after 25 years, to attempt to reconnect with her family, especially her biological father. Throughout, Tamayo foregrounds anxiety around familial and cultural bonds and separations, ranging from the uncanniness of seeing one’s face in the faces of relatives in a faraway country—“I saw my grandmother I saw my face/I saw my aunt I saw my stupid face” (74)—to taboo questions and longings: “WHAT IS IT TO HAVE A PENIS THAT MADE ME & I WILL WANT TO LOOK AT IT OKAY” (10).

YOU DA ONE, a book that had already grappled with emotionally fraught events and relationships, encountered another traumatic rupture in the spring of 2015. Allegations of sexual misconduct arose against the editor of Coconut Books, a small press founded in 2004 that mainly published books by younger women poets—an editorial agenda that had once seemed refreshingly feminist, but now became worrying. Stories were shared via word of mouth among poets, and the editor’s name was included, alongside others, on an anonymous flyer that was circulated at the Association of Writers & Writing Programs conference, but an account of an incident involving the editor was never shared publicly by a survivor. In the wake of these allegations, many women published by or slated to be published by Coconut decided to cancel their contracts or ask the press to stop selling their books. Some poets chose to republish their Coconut books with different presses, sometimes with new cover and interior designs.

11 Other Coconut authors did nothing, and the press continued to print and sell their books.

12 Tamayo chose to pull

YOU DA ONE from Coconut and to end her relationship with the press. Over the next two years, she worked with Carmen Giménez, Suzi F. Garcia, and Sarah Gzemski of Noemi Press to reimagine the book.

13 The second edition is a radically new object that incorporates a record of the events that altered it. In the notes page at the back of the Noemi edition, published three years after the first edition,

Tamayo (

2017) refers to these changes as a “restaging” (142). In a prefatory note to the reader, she describes her decision to withdraw the book:

The original publisher of this book played a role in people’s suffering and contributed to the ongoing silencing of survivors of sexual assault, none of which I could support. There are details and names that are neither mine to share, nor crucial to this moment of NO.

14 My decision to withdraw the book from its original home was not exclusively about one person, or one publisher or one instance. It was about patterns and layers of trauma so deeply imbedded in our literary communities that it will take many efforts, small and large, to begin to address and dismantle. (5)

The restaged edition of

YOU DA ONE is visually marked by the events that compelled its republication. The pages of the first edition remain present, appearing as black or full-color text and digital art on white backgrounds. New to the second edition are black pages with white text, art, and screenshots that are interspersed among the pages from the original book. These added pages contain records of collective activism and individual dissent, including screenshots of Tamayo’s Facebook posts from 2014 to 2015, many pages of excerpts from “No Manifesto,” Tamayo’s own poems that use the “No” litany of the manifesto, and the language of Enough is Enough’s “Call to Action” handout from the Poetry Project town hall—another document that Tamayo coauthored, and that was published in the

Chicago Review forum partly as a result of her lobbying (

Call to Action 2015, p. 202).

The juxtaposition of black and white pages in the second edition of

YOU DA ONE enacts the “patterns and layers of trauma” embedded in its publication history. As Tamayo puts it: “I hope this version of YOU DA ONE, complete with ‘interruptions’ of collaborative writings, Facebook posts, and community hand-outs I contributed to alongside colleagues between 2014 and 2016, will more fully express what this book has come to mean in my life; a scar” (7). Tamayo’s image of book-as-scar recalls Anzaldúa’s “1950 mile-long open wound” running through the land, the culture, and her body at once. In the second edition of

YOU DA ONE, black pages visually scar the book, their content rupturing its original forms and themes as they document a cultural moment of reckoning with and protesting sexual violence. The hybridity of the restaged book bears the marks of having been “forged amid political struggle” (

Arteaga 1997, p. 153) and “uneven and unsynthetic power relations” (

Lowe 1996, p. 67). Its “interruptions” are the wounds of struggle and domination, the literary representation of cultural positions imposed by force.

When reading the restaged

YOU DA ONE, the thematic relationship between the content of the first and second editions is not immediately clear. Traumas surrounding migration and family on the one hand, and sexual violence in poetry communities on the other, seem to be layered into a deliberately unresolvable palimpsest. By scarring the book, Tamayo insists on the interconnectedness of these events without drawing clear lines for the reader. Instead, she poses different sorts of questions: How can one person hold together all of these crossings, fractures, and remakings? How can a book represent such a “real body,” to echo both Peart and Wilding and

Poems are the Only Real Bodies, the title of Tamayo’s 2013 chapbook (

Tamayo 2013)?

15 How can language and artmaking arrive at something besides resolution in response to traumatic experiences? What happens when the “open wound” becomes a book?

Understanding the way the borderlands wounds of Tamayo’s migrant identity are connected to the events surrounding the republication of YOU DA ONE is key to grasping how the hybrid strands of the two editions speak to one another. Tamayo explicitly ties these strands together in a Facebook post included on a black page in the second edition:

The post combines raw, defiant language with a photograph that shows an impish expression on Tamayo’s face as she holds up her two middle fingers.

16 While the pose and language are brazen, the writing also invokes Tamayo’s precarious status as an immigrant, making plain the risk of speaking out: “Don’t forget me when I’m deported.” While Tamayo’s published poetry has never been decorous and has always freely incorporated taboo subject matter and explicit language, this moment in

YOU DA ONE goes a step further. The stakes of the restaging snap into focus: getting involved in a legal battle with her former editor could potentially threaten her ability to remain in the U.S. as a permanent resident. If this seemed like a far-fetched possibility in 2015, it no longer did by the time Donald Trump won the U.S. presidential election the following year. The risks of the restaged

YOU DA ONE are not merely aesthetic but also intersect with Tamayo’s vulnerable position in the legal–political matrix of the immigration system. By invoking the violence of the state through the threat of deportation, Tamayo connects the scars of the second edition of

YOU DA ONE to the first edition’s depiction of the ruptures of migration.

In her introduction to the second edition, Tamayo notes the impossibility of weaving a unified posttraumatic subjectivity in the wake of all these events: “I hear a screaming in some of these poems, a working to reconcile that I was too many traumas braided, traumas surfacing and seeing themselves in the shimmer of histories whose last refusal is irreconciliation” (6). The “I” who is “too many traumas braided” is an image of the subject whose hybridity has been forced upon her through the scars of sexual and state violences. Rather than try to mend these wounds, to smooth out the braid, she instead embraces irreconciliation, because she is

This drawing, initially posted on Tamayo’s social media accounts and later incorporated into the restaged YOU DA ONE, rejects the salve of personal healing as a mandated response to systemic social ills. As part of her refusal to reconcile the strands of the “I” who is “too many traumas braided,” she rejects the idea that she should find a personal way to heal the damage done to her by imperialist capitalist white supremacist cis-hetero-patriarchy. Like the crowd of feminists, Tamayo experiences incongruity and nonreconciliation within her own hybrid subjectivity, and demands the right to remain in this state.

Rather than offer the closure of healing, the heightened hybridity of the restaged book is meant to spark feelings of discomfort and nonresolution in the reader. Tamayo insists that “Our reading of YOU DA ONE must be like the story of its reprinting: interrupted, marred, uncomfortable and unfinished” (7). It is worth noting that Tamayo considers

YOU DA ONE, which has already gone through two editions and drastic changes, unfinished. The editions mark moments in a process of art- and self-making that, like the borderlands, “is in a constant state of transition” (

Anzaldúa 1987, p. 3). Rather than offering the fixity of a published book that has resolved the traumas that it addresses, “[t]he text, like identity, like mestizaje, ‘is a dynamic process, constantly changing, constantly evolving,’” as Jill Darling, citing Domino Rene Pérez, puts it in a study of Anzaldúa’s borderlands as process and possibility (

Darling 2021, p. 165;

Pérez 2019, p. 245). What takes the place of healing or resolution is the dynamism of continual evolution, in self and text: “The processes of construction become a journey through the past and present and envision potential, alternative futures narrated by hybrid voices” (

Darling 2021, p. 165). In an article on the queer migrant poemics of #Latinx Instagram,

Urayoán Noel (

2019) describes this continual evolution as central to Tamayo’s work more broadly: “images and phrases recur throughout not just the book but also in her performances and videos, radically recontextualized each time in a poetics of constant remediation” (551). To always be in process, in a single book or across a body of work, is to refuse arrival, completion, or resolution, and instead to continually open up new ways of being and artmaking.

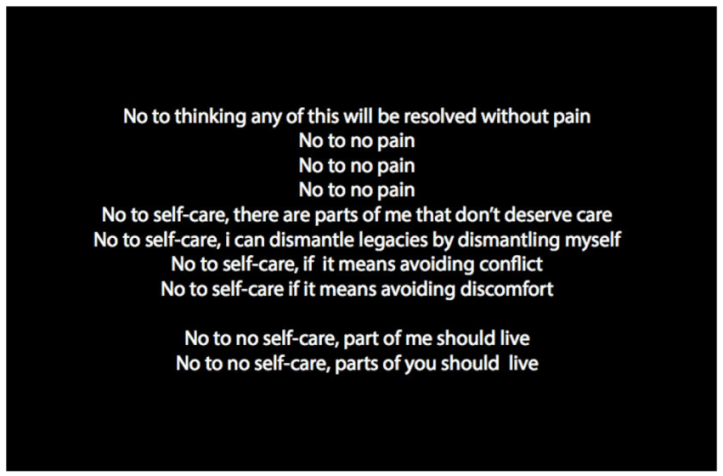

The final black page of

YOU DA ONE—the last of several instances in which Tamayo extends the litany form of the “No Manifesto” into the book—reads:

17Again, Tamayo explicitly rejects healing, reconciliation, and self-care as culturally mandated ways of responding to the effects of systemic harms. At the same time, in the spirit of the twisting, internally contradictory logic of “No Manifesto,” Tamayo’s “No to self-care” swiftly pivots to “No to no self-care.” While the political subject must be rigorous in her self-critique, she must also be oriented toward survival: “part of me should live”; “parts of you should live” (

Tamayo 2017, p. 140). If, for Anzaldúa, what emerges from “the open wound of cultural conflict” is “the new subjectivity” (

Arteaga 1997, p. 39), for Tamayo, new survival strategies for the self and the collective are born out of scars.

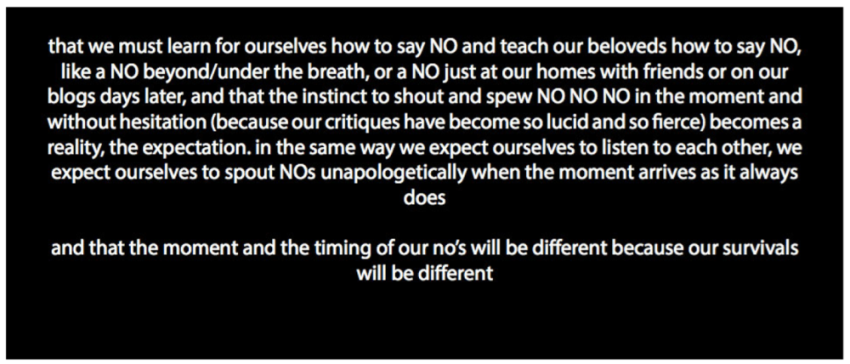

One of the newly inserted black pages offers a set of instructions for how saying “no” can become a survival tactic. This page appears on the lefthand page that faces page 39, the page reprinted above that features Tamayo’s Facebook post from 2 June 2015:

Tamayo offers a vision for how to extend the rhetorical “No” of “No Manifesto” into the social sphere. The act of saying “no” is a personal-is-political tactic: it begins with the self (“learn for ourselves”) and among friends (“teach our beloveds”) in ordinary domestic (“just at our homes”) and virtual (“or on our blogs”) spaces, becoming increasingly potent as more and more members of the group practice saying “no.” Because women and members of other subjugated groups are usually socialized to display agreeableness and docility, this oppositional stance must be actively taught, learned, and practiced until it becomes an “instinct to show and spew NO NO NO in the moment and without hesitation.” What must be rejected—from rape culture to demands for free labor—will be all-pervasive, and so saying “no” must become an “instinct”: repetition leads to reconditioning until the “no” becomes automatic, a habit that requires little energy. In Tamayo’s vision, this instantaneous refusal also requires the support of a community (the “beloveds” that make up the “we”) dedicated to political analysis (“our critiques have become so lucid and so fierce”). This accumulation of “no”s arises out of a shared struggle and ripples out to become quotidian collective activism.

The book’s shift toward a focus on collective resistance and survival can also be seen in elements of the restaged edition’s design. Tamayo’s face appears on the cover of the 2014 edition, reflecting that book’s interest in the narcissism and (over)identification embedded in family relationships and online life:

![Humanities 14 00153 i006]()

The restaged cover features a green-tinted photograph of a palm tree jutting out from a building, perhaps reflecting Tamayo’s move to northern California in the years when she was working on the new version of the book. The word “ONE” in the title has been replaced with the image of a hand cursor, suggesting a “one”ness that is both digital and embodied. The hand cursor can be read as a nod to the activism and writing that grew out of posting, organizing, and information-sharing over the internet. The book no longer tells only a personal story but also documents shared efforts: the “one” has become the online collectives of the crowd of feminists, Enough Is Enough, the writers who anonymously posted the “bay area concerns with mysogyny [sic] and gender/sexual violence” (

Bay Area Concerns 2014) statement, and other groups.

Even the author’s name is spelled differently in the new edition: “Jennif(f)er” reflects the (mis)spelling of Tamayo’s name on her permanent resident ID card as “Jeniffer.”

18 Tamayo’s decision to change her name is one of the most powerful indications of the extent to which she was transformed in these years. As she writes in her introductory note: “I/t was too many NOs. In the past few years, though, I have become even more things somehow” (6–7). It is as if a new person, radicalized by the events the book documents, has authored the second edition. In

Immigrant Acts, Lowe defines cultural hybridization “as the uneven process through which immigrant communities encounter the violences of the U.S. state […] and the process through which they survive those violences by living, inventing, and reproducing different cultural alternatives” (

Lowe 1996, p. 82).

YOU DA ONE confronts the threats of state and sexual violence even as it offers blueprints for survival based in the continual remaking of self, text, and community. The “different cultural alternatives” folded into the book include collective activism and organizing, making and remaking books, and learning to say “no” as individuals and communities.

In her introductory note to the restaged YOU DA ONE, Tamayo makes clear that her personal story is just one iteration of social and political concerns that need to be addressed broadly and systemically, in the poetry world and beyond: “The end of rape culture will not be comfortable because, like all struggles against violence and domination, it is deeply imbricated in the global anti-blackness and the ongoing settler colonial project that enmeshes so many lived realities and in which I am implicated” (5). Here, the “momentary ‘we’” that “screamed NO” in poetry communities from 2014 to 2017 expands into a larger collective fighting against, and implicated in, multiple interlocking forms of oppression. The activism that YOU DA ONE documents and performs, alongside its intertext “No Manifesto,” not only belongs to the #MeToo moment of feminist resistance, but also ripples out into ongoing efforts to dismantle racism and settler colonialism. This broadly intersectional view of the language, images, and events circulating around the book suggests that “writing about the world is no longer different from writing about the self” (Gray and Keniston 3) and that the tactics of “No Manifesto” and YOU DA ONE might serve as models for a poetics of liberation. By refusing to play by the rules of poetic or social discourse—the logics of domination that would have them be singular, cohesive, and compliant—Tamayo and the authors of “No Manifesto” insist on alternative ways of composing literature, performing political resistance, and entering the public sphere. These hybrid, activist poetic texts demonstrate the power of the collective to disrupt the social and literary status quo. This is poetry that tried make something happen, and succeeded.