1. Introduction

In her introduction to

American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry,

Cole Swensen (

2009) notes a shifting gender balance in the remapping of contemporary poetry (xxv). She points, too, to an increased internationalism and multiculturalism that has “broadened the aesthetic field,” outlining that the poets in

American Hybrid “…come from China, England, Lebanon, Germany, Jamaica, Canada, Korea, and elsewhere” (xxv). Such “elsewhere” does not include Ireland, which perhaps is notable given Ireland’s global reputation for poetry and multiple Nobel Literature Prizes (three of the four awardees wrote poetry). Nonetheless, when

American Hybrid was published in 2009, it would have been difficult to find Irish poetry that substantially contributed to the field of hybrid or mixed-genre poetics. This article gives preference to the latter term to describe aesthetic approaches that challenge a singular narrative/lyric voice and feature fragmentation, broken sequence, secondary material, and/or documentary modes, in line with Swensen’s description (xxi). Such preference for “mixed-genre” foregrounds a compositional and/or literary framework, rather than a post-colonial one concerned with cultural identity and difference (

Bhabha 2004, pp. 1–27). In the Irish context, the main pre-2009 example of mixed-genre poetry is John Montague’s

The Rough Field, (

Montague 1972), which would hardly fall under the volume’s description of “new poetry.”

1Since 2009, however, there has been a remarkable emergence of hybrid book-length poetry in the Irish context, particularly authored by women. Such book-length poetries include, but are not limited to, Kimberly Campanello’s

MOTHERBABYHOME (

Campanello 2019), Gail McConnell’s

The Sun is Open (

McConnell 2021), Susannah Dickey’s

ISDAL (

Dickey 2024), and my own ongoing project,

Certain Individual Women.

2 Primarily through a practice-based and compositional framework, this article will examine the resonances between the above mixed-genre or hybrid Irish poetries and earlier North American examples by women, including M. NourbeSe Philip, Claudia Rankine, and Maggie Nelson, all of whom provide strong models for Irish women writing in the mixed-genre form. These works by North American and Irish poets are socially oriented in that they “…incorporate, chronicle, or allude to public events” and share a strong concern with social and political issues, including gender-based oppression and violence, slavery, racism, and colonialism (

Keniston and Gray 2012). Such social engagement is significant in the book-length poetry form, as noted by Lynn Keller in

Forms of Expansion: Recent Long Poems by Women (

Keller 1997). Keller outlines the relationship between the long form and social movements, specifically noting that the victories of second wave feminism in the United States appear to have empowered women to “…no longer feel intimidated by the associations of grand poetic scale with the heroic, public realm, with intellectual depth and scope, or with great artistic ambition” (14). She points to the “burst of production” since the early 1960s of long-form poetry by women in North America and its importance in bringing attention to women’s experiences and subjectivities and to the construction of gender in and through language (14). Such a “burst” of production of book-length poetries is evident in Ireland over the past decade. Whereas long-form and certainly book-length poems by women in Ireland were rare prior to 2009,

3 such poetries have emerged strongly in the last decade, coinciding with historic social changes and significant overhauls to Irish law, particularly in relation to marriage equality and abortion rights. Thus, the Irish context aligns with Keller’s theory that the prevalence of certain poetic forms and the willingness of marginalised poets to engage with those forms may indeed be contingent upon increased levels of empowerment.

When making connections between women writers in the Irish context and the North American context, it is important to note the vastly differing histories of women’s rights. Keller’s

Forms of Expansion was published in 1997, at which time abortion had already been generally accessible for almost a decade in Canada and since 1973 in the U.S.

4 Until 2018, the Irish Constitution mandated the equal right to life of a woman and a fetus, meaning that abortion was unconstitutional, illegal, criminalised, and completely inaccessible on the island of Ireland. Abortion care (up to twelve weeks) has been accessible in Ireland and Northern Ireland only since 2019, following a historic public vote to change the law.

5 Though reproductive care has been drastically limited in the United States since 2022, until that point, the U.S. and Canada had very different trajectories from Ireland in terms of women’s rights.

6 Perhaps it is no surprise that while North American poets such as Bernadette Mayer, Lyn Hejinian, C.D. Wright, M. NourbeSe Philip, Claudia Rankine, and many more women forged ahead with experimental book-length poetries throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, such poetic forms remained out of reach for Irish women poets. As one of Ireland’s foremost poets Eavan Boland wrote in 1995, “In the old situation which existed in the Dublin I first knew, it was possible to be a poet, permissible to be a woman and difficult to be both without flouting the damaged and incomplete permissions on which Irish poetry had been constructed” (

Boland 1995, p. xii). This article demonstrates the enabling influence of mixed-genre poetries by North American women on those “incomplete permissions” for Irish women poets. In doing so, I will offer an overview of the interruptive strategies in a number of recent publications. Beginning with

Jane: A Murder (

Nelson 2005) and

ISDAL by Derry poet Susannah Dickey, I will conduct a close reading of the specific compositional techniques in their respective poetic examinations of gender-based violence. I will then turn to consider the use of other devices in both the North American and Irish contexts: firstly, the use of archival sources and news reporting in Claudia Rankine’s

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (

Rankine 2004) and Belfast poet Gail McConnell’s

The Sun is Open. I will continue with a brief examination of the aesthetic resonances between

M. NourbeSe Philip’s (

2008)

Zong! As told to the author by Setaey Adamu Boateng, Kimberly Campanello’s

MOTHERBABYHOME, and my poem-artwork

Positions Gendered Male in Bunreacht na hÉireann/1937 Constitution of Ireland. As part of that analysis, I will also consider mixed-genre poetry off the page. Throughout, my analysis will pay particular attention to what I deem “a poetics of material interruption” on both sides of the Atlantic, brought to bear through marginalising forces of gender and colonisation, themes prevalent in both the Irish and North American contexts (Morrissy “Huddle” 189–200). I will posit that the material strategies of these mixed-genre poetries interact with the material conditions to which they respond, thus creating a “poetics of material interruption.” While this article draws out commonalities in the compositional approaches of the above writers, it is important to note, as Nelson does in a separate context, that such “commonalities” are not intended as “equivalences” in relation to the specific histories, cultural contexts and themes of the works discussed (

Nelson 2024).

7 Thus, the commonalities discussed herein also include several areas of difference.

2. Interruptive Strategies in Jane: A Murder and ISDAL

Published in 2005, Nelson’s

Jane: A Murder foregrounds its mixed-genre form and reliance on secondary materials from its preface: “Some of the writing that appears here is Jane’s own, either from her childhood diary dated 1960–61…or a loose sheaf of journal pages…although this is a ‘true story,’ I make no claim for the factual accuracy of its representation of events or individuals” (original emphasis n.p.). The format and investigative nature of the contents page is reminiscent of a legal Book of Pleadings: “THE LIGHT OF THE MIND (Four Dreams); FIGMENT; HOW THE JOURNEY WAS; ORDER OF EVENTS; SOME QUESTIONS; TWO ECLIPSES; A SIMPLY STATED STORY; and EPILOGUE” (

Figure 1). A typical common law Book of Pleadings would include items such as the Notice of Trial, Pleadings, Orders, and Notices/Replies, usually capitalised and indexed in a similar fashion to the contents page of

Jane (

courts.ie 2018). Dickey’s

ISDAL, too, begins with a preface outlining the facts of the unsolved death of a woman.

In November 1970, a woman’s body was found at Isdalen in Bergen, Norway. She was severely burnt on the front of her body (including her face and hair) but not the back. The autopsy concluded that she had died of a combination of carbon monoxide poisoning (she was not dead at the time of burning) and a barbiturate overdose. She has come to be known as the Isdal Woman (n.p.).

ISDAL’s preface is, too, followed by a stark contents page of three parts: “I—PODCAST,” “II—NARRATIVE,” and “III—COMPOSITE.” Although more concise than the contents page of Jane, the ISDAL contents are also capitalised and ordered in a bare evidentiary manner, not dissimilar to a legal document. Dickey’s preface details the chronology and circumstances of the Isdal Woman’s death, which resonates with Nelson’s careful description of the dates and sources for her book, again signalled before the contents page and set apart from the beginning of the book proper, as in ISDAL. Thus, both books begin with juristic prefaces, both contents pages share a similar objective investigative outline, and both explore the untimely and mysterious death of a woman. The opening sections both also heavily feature asterisks, either as the entire title in the first part of Jane (17–20), or as part of the title in ISDAL, for example, “* A gloomy introduction,” “* More importantly!” and “* Outtake #1” (3–4). As a symbol, the asterisk denotes omitted material, and, indeed, ISDAL and Jane embark on investigative quests into the gaps between the known and the unknown of the criminal investigations of the two women’s deaths.

Although relatively minor formal elements, the purposeful construction of the preface, contents, and punctuation in both books signal the poets’ intent from the outset. Furthermore, the similarity of such details between both books is striking given their overarching thematic and aesthetic alignments: both explore gender-based violence using mixed-genre book-length forms, divided into distinct parts, and relying on a blend of free verse poems, prose poetry, and secondary materials. In Jane, the prominent secondary materials include diary entries, letters, books, and news reporting. ISDAL features a high degree of intertextuality in its referencing of other poetry books, essays, and texts, in addition to the secondary material of the True Crime podcast represented in the first section. Indeed, ISDAL makes overt reference to Jane: A Murder: in “II—Narrative,” Dickey explores Nelson’s use of the term “figment” (81). The formal influence of Nelson’s Jane on Dickey’s ISDAL is therefore made explicit, and thus attention is warranted to the various minor and major parallels between the books, published almost two decades apart.

In addition to the typographical and material elements outlined above, there are clear resemblances in the exploratory impulses of both ISDAL and Jane and their emphasis on the subjectivities of the women centred therein. These connections can be seen in “Law Quadrangle, Section C, Second Floor” from Nelson’s Jane and “* Inventory” from Dickey’s ISDAL. Both poems foreground objects in highlighting the subjectivities of Jane and the Isdal Woman. An investigative and legal impulse persists in both poems, reinforcing my earlier observations about the legalistic style from the outset of the books. Nelson’s “Law Quadrangle,” a one-page poem of six stanzas, focusses on material objects in a law school: “A mallard-green glass lamp stands dark over a square of red felt./On Wednesday night, there had been the sound of a typewriter…/On Thursday night, there was no sound from the room at all, just the ringing of an unanswered phone” (93). The poem treats the law school and its contents as a crime scene to be poured over. From the colours to the materials, no detail is insignificant. The poem also documents shifts in time as important, just as a legal case would, which is then reinforced by the section’s title “ORDER OF EVENTS” (93–112). The attention to sound in the poem (of the unanswered phone) also plays with presence versus absence in the context of Jane’s disappearance. The poem ends by shifting the focus away from the objects and onto Jane exercising her agency: “She had her reasons;/she wanted to go home alone” (93). These lines juxtapose object and subject, with the material objects foregrounded for the majority of the poem, and Jane, as the subject, appearing unnamed and only in the last lines.

Dickey’s “* Inventory” also begins with objects: “two suitcases” found by the Bergen police (13). However, the poem quickly turns the investigation onto the Isdal Woman herself, rather than to the circumstances of her death: “What does a woman trying to change her looks look like, in items?” (13, my emphasis). There is a suspicion towards both the Isdal Woman and the woman in “Law Quadrangle” owing to their exercising of agency and choice. In the latter, the line “She had her reasons” suggests a defensiveness or an action that should perhaps be explained (Nelson 93). Dickey’s “* Inventory” attempts to piece together the Isdal Woman both through the objects in the suitcase and through her desire to change her looks. The emphasis is on the apparent disguises of the Isdal Woman (sunglasses, “saucy” underwear, wigs), which mark her out as “feigning any sort of normal life” (13). Like “Law Quadrangle,” the poem ends with the woman and her choices, though filtered through the voice of a policeman: “…She’s left these fripperies for us to find! he says. Just look at this dead woman’s proclivities!” (13). The Isdal Woman is equated to the objects she left behind, literally becoming objectified.

In considering how these poetries gesture towards a “poetics of material interruption,” we might think about such interactions between subject and object that exist from the outset of both books: in the descriptions of diaries and “loose sheaf pages” in

Jane and the gruesome description of the Isdal Woman’s burnt body. Both women’s lives were interrupted by violent deaths, and the story of each woman is depicted using formal interruptions. Citing Victoria Bazin, in

News of War,

Rachel Galvin (

2018) suggests that citationality and quotation can signal “[a] poem’s links to ‘the material reality to which it responds and out of which it comes’” (261). The poetics of material interruption builds on Galvin’s and Bazin’s observations, examining the ways in which interruptions to the speaker, the subject, and indeed to the reader of a poem are materially enacted through the aesthetic of the mixed-genre form. The diary poems in

Jane, titled according to the corresponding year, are interrupted by more forensic poems such as “Law Quadrangle,” or poems that include the language of newspaper reporting and journalism (“COLLINS’S STATEMENT” 146; “JOHN COLLINS” 147; “A SIMPLY STATED STORY” 210; “CONVERSATION” 151). Nelson’s typographical and title choices reinforce these interruptions, allowing the reader to follow when we are in Jane’s voice/perspective, by titling those poems according to their corresponding date, i.e., “(1966)” (66). The voice in Jane’s diary is then consistently interrupted by poems that engage with the outside forces that react to or act upon Jane’s story.

The interruption in ISDAL arises from the complete change of form between its three sections, in addition to the internal spacing within some of the poems. The first section foregrounds the context of a True Crime podcast. Although the poems are a mix of free verse, narrative, and lyric, they take recognisable poetic forms, often using couplets and tercets, and each bears a distinct title. These poems are interrupted by the second section “II—NARRATIVE,” which is exactly that: a series of narrative prose reflections on the Isdal Woman and the True Crime genre, with only the symbol “[…]” repeated as the title throughout. The third section of ISDAL returns to poetic forms, including sonnet variations and couplets, and focusses on the young sisters who found the Isdal Woman’s body, one of whom who saw the body and one who did not:

Anyway. A girl has to get three items across a lake in a boat.

One is her having seen something, another is her sense

of responsibility for her sister’s not seeing. The third is what

she’s seen: an image that will recur in her mind for the weeks

to come. (89)

The discovery of the body creates an interruption into the lives of the two girls. Throughout Jane, the reader is, too, aware of the interruption caused by the murder of a young relative and particularly to Nelson, who is at pains to piece together the story of her aunt’s life and death using the sources available to her. Jane’s penultimate poem “DENTON CEMETERY” is set in the graveyard in which her aunt’s body was found, left on a grave “closest to the entrance” (217). The poem ends, “So there’s/no plot. Here is just where/he dumped her, on a night of cold rain/and where my mother and I stand today,/listening to the birds” (217). Both Nelson and Dickey leave the unresolved questions about the women’s violent deaths in the hands of two female figures, the two girls in ISDAL and Nelson and her mother in Jane, all of whom are removed somewhat in time or relation from the victim, but still deeply affected.

3. Archive and News-Reporting in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and The Sun Is Open

Although

ISDAL and

Jane engage with journalism, the genre of news reporting is more explicitly depicted in the aesthetic form of Rankine’s

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and

Citizen (

Rankine 2014a) and McConnell’s

The Sun is Open. Rankine explores contemporary instances of structural and systemic racism as it routinely manifests in daily life, often, but not exclusively, in the U.S. context. In both her above books, she creates an aesthetic of interruption through the interaction of image and text, but more specifically in

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely by mimicking a newspaper format (

Figure 2). My article “Speaking to the Masses: Hybrid Poetics and Marshall McLuhan’s ‘Newspaper Landscape’” outlines the ways in which the formal techniques of

Citizen and

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely link to news reporting (Morrissy “Speaking” 12–14). However, I will now return to that discussion to make new connections between the newspaper format in

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and McConnell’s

The Sun is Open. As noted in the above article, the physical characteristics of

Don’t Let Me Lonely as a book include a long, narrow shape and black and white images ranging from graphic reproductions of television sets, media photographs of crime scenes, and images of medical labels, warnings, and diagrams (Morrissy “Speaking” 13). Rankine explores a variety of interruptions to American life, including health issues, racial violence, state violence, and terrorism, using a poetic form that builds those serious and often fatal interruptions into the text using images and secondary sources.

The Sun is Open also deals with a fatal interruption: McConnell takes as her subject the murder of her father by Irish republican paramilitaries when she was a young child. Similar to Dickey’s direct referencing of Nelson, the connection between

The Sun is Open,

Jane, and the theme of familial murder is made explicit by the front cover endorsement of McConnell’s book from Nelson herself. However, McConnell’s engagement with news reporting more closely aligns with mixed-genre poetry by Rankine and other poets, including C.D. Wright, who uses the newspaper format in her 2010 book-length poem

One With Others (

Wright 2010), which features, among other elements, a recurring “Dear Abby” newspaper column (61, 106). In

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, the narrow format of the page, blocks of prose-like text, and greyscale images foreground the context of newspaper reporting.

The Sun is Open begins with an excerpt from a newspaper article reporting the murder of William McConnell “…assistant governor of the Maze Prison [who] was outside his home, checking underneath his car for explosive devices, when he was shot dead in front of his wife and three-year-old daughter” (n.p.). This opening passage is presented in a recognisable newspaper form: the first three words are capitalised, and the text is justified and appears with black lines running down the margins on each side (

Figure 3). This form is repeated for the majority of the book. Most of the poems appear as blocks of justified text, formatted in the centre of the page. The “Notes” section directs the reader to a variety of sources, including newspaper articles, witness statements, literary references, and the diary of the late William McConnell (119–21). These sources are similar to Nelson’s

Jane, but the manner in which McConnell consciously takes on the

form of the newspaper is more akin to

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, the text of which is arranged as justified, centre-aligned blocks with wide gutters on either side (

Figure 2). Although McConnell’s collection does not feature images, the range of sources listed in the Notes section points not only to the factual circumstances of how William McConnell’s life was interrupted and ended but also the ways in which the murder of her father continues to interrupt and disjoint the speaker’s own life:

not an archive not a fever not a

feeling all these things and none

it’s what dislodges in my body

when I hear balloons pop pop the

birthday party I spent in the

corridor outside the room (112)

Both Don’t Let Me Be Lonely and The Sun is Open address fatal interruptions caused by forms of authority (whether legitimately held or not). The newspaper format of both books further suggests that the impacts of the interruptions are not limited to the tragic events themselves but are perpetuated by the manner in which those events are reported, narrativised, and often sensationalised and depersonalised by the media. McConnell and Rankine’s aesthetic forms delve into personal impact, building interruption into the reading experience, as is the case for Nelson and Dickey, and pointing to the ways in which the treatment of the incidents by surrounding structures (media and law specifically) creates further interjections to our processing of human tragedies. The poetics of material interruption emerge in the above poets’ representations of these interruptions on the page, incorporating the very materials that reinscribe the interruptions (i.e., news reporting, police investigations, True Crime podcasts, legal proceedings, etc.) into the mixed-genre form.

4. Interruption in Zong!, MOTHERBABYHOME, and “Certain Individual Women”

Another prominent way in which interruption is represented in such poetries is by challenging the very logic of our reading practices, as seen in M. NourbeSe Philip’s

Zong!, a 2008 book-length poem about the drowning of African slaves aboard the Zong ship in 1783. In the “Notanda,” Philip explains that in writing the poem, she “locked [her]self” into the text of the legal judgment, which was a contract law case centering on an insurance claim about the slaves as cargo, rather than a criminal case about mass murder (191). Philip writes, “In

Zong!, the African, transformed into a thing by the law, is re-transformed, miraculously, back into human. Through oath and through moan, thorough mutter, chant and babble, through babble and curse, through chortle and ululation to not-tell the story…” (196). She continues, “I replicate the censorial activity of the law, which determines which facts should or should not become evidence;

what is allowed into the record and what not” (199, my emphasis). In a strikingly similar manner, though an entirely different context, Kimberly Campanello’s 2019 collection

MOTHERBABYHOME, too, “locks” itself into the language of an official report into an unmarked burial site at the St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co. Galway, where 796 babies and children died between 1925 and 1961. The institution did not maintain official burial records for children who died in its care, and the final resting places of the children are undocumented. Extensive research undertaken by local historian Catherine Corless revealed that the remains of the children were deposited in an underground disused septic tank, wherein their bones were “mingled together” in a mass grave (Corless qtd. in

Carroll 2023). Following Corless’s findings, a government report was initiated in 2015 through the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes (“Final Report”) (

gov.ie 2021). Campanello’s

MOTHERBABYHOME incorporates the facts of that report and Corless’s investigation into a poetic form of a 796-page poem, one page for each child identified in the death records (Campanello “MOTHERBABYHOME”), creating an alternative record and connecting with Philip’s above questioning of what the official record chooses to reflect. Initially produced as a “poetry-object…printed on transparent vellum and held in a handmade oak box,”

MOTHERBABYHOME was also published as a standard reader’s edition by zimZalla in 2019 (

Campanello n.d.a).

There are two major resonances between

Zong! and Campanello’s interruptive strategies in

MOTHERBABYHOME: firstly, both books enact an interruptive reading experience owing to the ways in which language is represented on the page, and both interrupt the flow of the book by featuring the names of the victims. Dealing with the latter first, in “Os,” the first part of

Zong!, each page features a footnote section containing the names of African slaves on board the ship (1–45). These names were not officially recorded, as the slaves were legally objectified as cargo. Instead, they are imagined and gathered by Philip through retellings of the drowning. In her article “Venus in Two Acts,”

Saidiya Hartman (

2008) outlines a desire in her own writing to “…do more than recount the violence that deposited these traces in the archive” (3). She continues, “…it would not be far-fetched to consider stories as a form of compensation or even as reparations, perhaps the only kind we will ever receive” (4). At the same time, Hartman, like Philip, acknowledges that these stories are ultimately unrecoverable and unknowable (Hartman 12). Nonetheless, in

Zong!, Philip’s placement of the names enacts the ritual of burial, returning a form of dignity and presence to those who were captured as slaves and then killed when the ship got into difficulty. She refers to the book as “…a work of haunting, a wake of sorts, where the spectres of the undead make themselves present…literally in the margins of the text, a sort of negative space, a space not so much of non-meaning as anti-meaning” (201). By naming the victims, Philip acknowledges their lives and personhood, while the form of the footnote underneath the main text itself simultaneously enacts a burial, creating a pause or interruption for the reader.

MOTHERBABYHOME, too, includes the names, dates of birth, and ages of children who died, also in the form of marginalia. While Corless’s research and the government report reinstate the names of children who died at the Home, specific identification of the victims has been impossible due to the lack of proper burial and the state of the remains recovered from the septic tank. In MOTHERBABYHOME, the names of the children sometimes appear at the top left of the page, for example, “Cunningham Joseph 13/04/1947 2 mts” printed above a block of justified text, which itself is again reminiscent of newspaper reporting (n.p.). In this particular passage, the text directly refers to journalism:

the Taoiseach

8 thanked him for

bringing him to the power of

personal testimony far from

tabloid journos, it’s not salacious (n.p.)

Here, Campanello engages with the impact of media representation in a manner reminiscent of Rankine and McConnell. Elsewhere in MOTHERBABYHOME, the victim’s name appears in smaller font than the main body of the poem, tacked on to the end of a line: “disappearances refuses to/disclose their fate or/whereabouts Reilly William 20/03/1947 8 ½ mts” (n.p.). Both Philip and Campanello confront themes of presence and absence by including the names of victims, whether recorded or imagined, while distinguishing them typographically and placing them marginally in relation to the main text. A tension exists in both texts between the act of naming the victims and their marginalisation in society and the legal system.

Throughout

MOTHERBABYHOME, which contains no page numbers, as a poetry-object nor as a book, Campanello interrupts standard reading practices by stacking and layering text over itself to the point that it becomes almost illegible (

Figure 4). As

Zong! progresses, the lines and words stray further from the left margin of the page. In the penultimate section “Ferrum,” the language is no longer arranged into a stanza form, and the words are spaced across every part of the page (125–173). The final section “Ebora” sees the font change from black to light grey (175–82). As in

MOTHERBABYHOME, the text becomes obscured with words printed atop each other. On the final page, these typographical interferences are such that the letters are indistinguishable and the words unreadable (182). Philip refers to the “fragmentation and mutilation of the text, forcing the eye to track across the page in an attempt to wrest the meaning from words gone astray” (198). She further explains the ways in which “…much of the language we work with is already preselected and limited, by fashion, by cultural norms—by systems that shape us such as gender and race…By order, logic, and rationality. This, indeed, is also the story that cannot be told, yet must be told” (198). The move away from ordered “rationality,” “logic,” narrative, and other standard reading and story-telling practices in both

MOTHERBABYHOME and

Zong! reinforce the flawed logics and worldviews that themselves led to the murders and deaths represented in each book (198). The lives of the victims were indeed interrupted, and that interruption is foregrounded by creating an interrupted reading experience through the use of footnotes and marginalia, which simultaneously stall and ground the reader in otherwise fragmented texts, and also through the scattered format and deliberate obscuring of language. In “ACCOUNTS UNPAID, ACCOUNTS UNTOLD: M. NourbeSe Philip’s

Zong! and the Catalogue,”

Erin M. Fehskens (

2012) recognises that interruptions and, indeed, “disruption” allow Philip to “…first [render] multiple terms equivalent and later [flood] her text with polyvocality and multiple word possibilities” (410). Further, and specifically in relation to

MOTHERBABYHOME and “

Positions Gendered Male in Bunreacht na hÉireann/1937 Constitution of Ireland” (discussed below),

Adam Hanna (

2019) notes that the adoption of a collagist style, the breaking of generic conventions, and the focus on the materiality of language represent “strategic and subversive acts” (“Contemporary Encounters with the Law” 14). As readers, our normative reading practices are certainly challenged by Philip and Campanello, which in turn encourages further scrutiny of our acceptance of legal and state structures that failed both to record these deaths and to follow legal protocol for burials, in the case of Tuam, or that failed to recognise the victims as human and, thus, the deaths as murder, in the case of Zong.

5. Mixed-Genre Forms off the Page

In considering hybridity and mixed-genre forms, it is important to note the ways in which the above poets sometimes take their poetic engagements off the page. For example, Rankine’s piece “Stop-and-Frisk”(

Rankine 2014b) from

Citizen also takes its form as a “situation video,” broadcast on

PBS News Hour and available on

YouTube (

Rankine 2014c). Performance and durational readings are a regular part of Philip’s dissemination of

Zong!: she has given over sixty readings and performances in nine countries, to include eight annual durational readings held on the anniversary of the Zong massacre (

Philip n.d.b). In 2020, Campanello gave a durational reading of

MOTHERBABYHOME in Dublin (

Campanello n.d.b). In my case, as a poet, the above re-imaginings of the book-length form off the page have been influential and, indeed, reinforce the connections between mixed-genre poetries in North America and Ireland. My poetic engagement off the page includes live performance, poetry film, and theatre. In order to further demonstrate the particular interruptive strategies in question, I will briefly examine the connections between the visual arts context in my project “

Certain Individual Women” and interruptive strategies in

Zong!My ongoing project “

Certain Individual Women” explores gender discrimination in Ireland since the founding of the State in 1922. The poem unfolds in three strands, following two speakers, Me Plus (based on my own life) and Fra (based on my maternal grandmother), and the figure of the law. Like Philip, a former lawyer, I am a law graduate. Thus, in the composition of my book-length mixed-genre poem, I looked to

Zong! as an example of legally based poetry. Philip’s repetition and scrutiny of legal language arises from her engagement with the Gregson v. Gilbert legal judgment as a “word store” for

Zong! (191), a strategy Campanello subsequently enlists in

MOTHERBABYHOME and I take up in “

Certain Individual Women” in which I reconstruct the language of Irish legislation and the Irish Constitution with regard to gender discrimination. As Keniston and Gray note, in socially engaged poetries “…[the] language is often not ‘poetic’ but rather found, processed, even official. Poets use this appropriated language…to critique it, alternate or juxtapose it with other language, or simply to present it whole, as a found object” (10). My poem-artwork

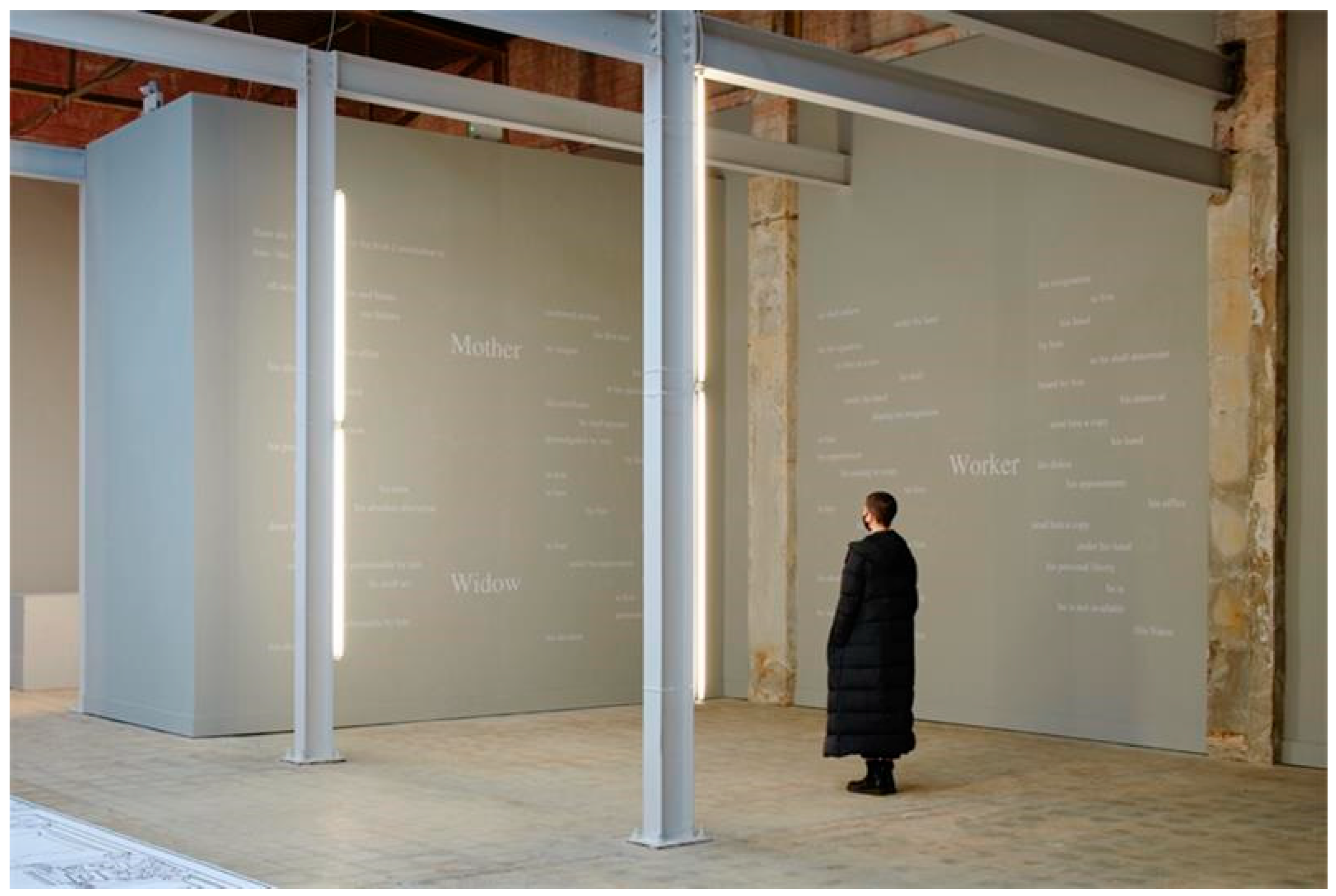

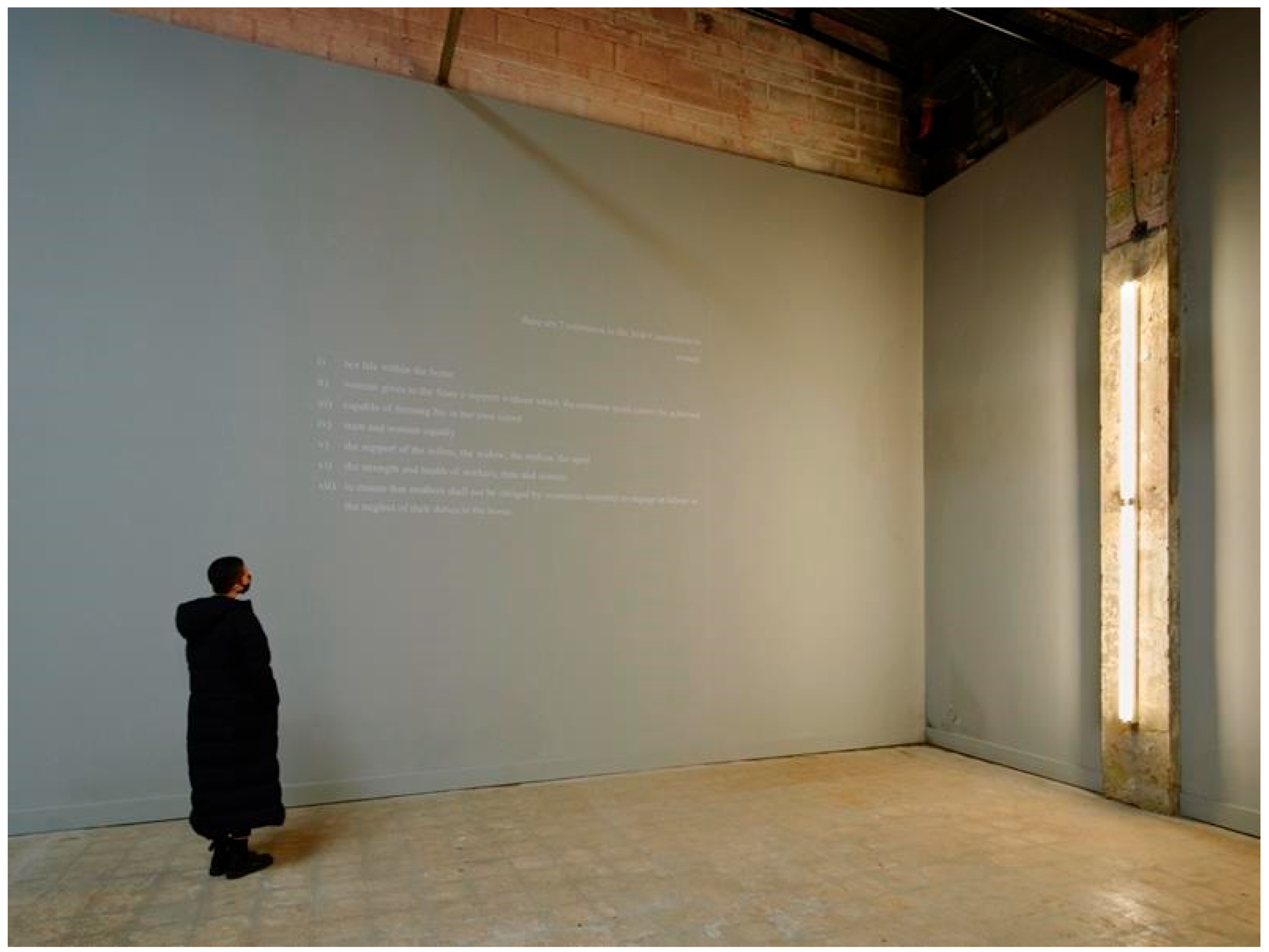

Positions Gendered Male in Bunreacht na hÉireann/1937 Constitution of Ireland is adapted from the eponymous poem in the manuscript version of “

Certain Individual Women.” On the page, the poem follows some of Philip’s experimentation in relation to spacing, repetition, and a focus on the materiality of language in order to create an interrupted reading experience. Both on the page and in its gallery iteration at the TULCA Festival of Visual Arts 2020, the poem repeats most of the 110 instances of male-gendered pronouns in the Irish Constitution. The poem-artwork was produced on vinyl lettering and installed over three walls of the An Post Gallery, in which movement is one-directional. The first part of the artwork, which delineates the male-gendered pronouns, was exhibited on perpendicular walls in the near-corner of the gallery (

Figure 5). The final part of the poem-artwork, which displays the mere seven references to women in the Irish Constitution, was installed in the opposite corner (

Figure 6). While the viewer may glimpse the far wall containing the female-gendered positions upon entrance to the gallery, the artwork is intentionally installed in an interrupted manner. The viewer first encounters the two walls of male-gendered pronouns before continuing through other artworks, until they reach the opposite corner showcasing the last part of the poem. This installation was informed by a “poetics of material interruption,” with the intention of posing questions about ruptures caused by the designation of gender in Irish legal texts. The visual arts context also allowed the incorporation of movement into the poem-artwork: the viewer experiences it in an interrupted fashion and through the movement of their own body in the gallery space, calling attention to issues of subject and object referred to throughout this article in relation to works by Nelson, Dickey, Philip, Rankine, and Campanello. In

Zong!, Philip describes how the “material and nonmaterial come together in unexpected ways” (191). The Gregson v. Gilbert legal case turned on a point of contract law that would designate the slaves on board the ship as objects or cargo (191). The slaves are also, of course, subjects of the slaveowners. Philip directly incorporates those tensions between subject and object into the materiality of her poem and indeed through the bodily experience of her durational readings, which last for several hours and are sometimes hosted over many days (

Philip n.d.a). The Irish Constitution treats women as subjects of the State while also objectifying us by legally mandating women’s roles and duties in society according to our capacities for childbearing. For example, Article 41 of the Bunreacht, which is current Irish law, specifically refers to a mother’s “duties in the home” (

Bunreacht 1937). In addition to informing how the language of the law can provide the basis for poetic engagement, the influence of Philip’s performances and imaginings of

Zong! off the page can be seen in the practices of Irish poets working with mixed-genre forms, including Campanello and me.