Abstract

In response to the increasing politicization and polarization of discourses around gender, sexuality, and the body, feminist theorists like Judith Butler call for feminism to strive toward flexibility and responsivity. This essay lays out some of the theoretical considerations that inform studies of graphic embodiment—or studies of embodiment in graphic narratives—both generally and within feminist studies, then examines several graphic texts by Tillie Walden and Élodie Durand that exemplify feminist theories of embodiment, with particular attention to the creative co-construction of embodied narratives.

1. Introduction

Embodiment, particularly the material and psycho-emotional experiences of diverse women, girls, femmes, and LGBTQAI+ persons living in heteropatriarchal social contexts, has long been a central concern of feminist analyses and activism. According to Jodi Cressman and DeTora (2021), graphic embodiment, the study of embodiment in graphic narratives—like comics, graphic novels, and graphic memoirs—engages cross-disciplinary and multiple methodological approaches to open doors to understanding and exchange via central questions about the interplay of comics studies and health humanities, with a nod to feminist and other theoretical approaches to embodiment. Cressman’s solo approach to graphic embodiment and witnessing (2021) notably leverages Eszter Szep’s claim that reading comics is an embodied act that encourages empathy. This essay applies these aspects of graphic embodiment to three twenty-first century queer graphic narratives in order to identify nimble, responsive, and flexible feminist responses to dominant social scripts that naturalize specific patriarchal systems, as advocated by Chela Sandoval (2000) and Judith Butler (2024a). These narratives’ responsive deployment of feminist representational strategies suggests similar possibilities in graphic narrative contexts more broadly.

As scholars working at the intersections of health and medical humanities, graphic textual analysis, and feminist theories, we open by situating feminism in relationship to the theme of graphic embodiment before presenting reflections on specific works: Transitions: A Mother’s Journey (Durand [2021] 2023) by Élodie Durand; and On a Sunbeam (Walden 2018) and Are You Listening (Walden 2019) by Tillie Walden. When considered together, these works provide thoughtful examples of graphic embodiment in relationship to feminism and amplify feminism in connection with graphic embodiment. While all three engage with these connections, each focuses on a specific pairing of feminist concept with embodied situation: Transitions employs graphic artistry of character development to engage with feminist evolution; Are You Listening turns to environmental considerations in order to better to understand and heal from trauma; and On a Sunbeam playfully engages with genre-bending and world-building in service of reimagining love. A graphic embodiment analysis of these relationships, drawing on an expansive definition of feminism that foregrounds and honors its interrelationship with gender theories more broadly, resituates Szep’s groundbreaking work on embodiment in nonfiction comics in relationship to comics that represent verisimilitude, thereby enacting the notion of graphic embodiment as always under consideration and as opening possibilities rather than staking claims.

2. Thinking About Feminism and Graphic Embodiment

2.1. Graphic Embodiment

Graphic embodiment was initially grounded through the health humanities, Graphic Medicine, comics studies, and gender studies as intertwined categories of theoretical inquiry, as Elisabeth El Refaie (2019) has modeled. Graphic embodiment can be read via what Squier calls engaged scholarship within a context of Graphic Medicine’s focus on enhancing access to and empowerment within healthcare systems. Squier, though, addresses a reader who carries an understanding of feminism into the text (in Czerwiec et al. 2015). Squier’s analysis of Graphic Medicine, then, engages with activists working to liberate medical care from its existing hierarchical models as well as with feminist creators and academics like El Refaie, Squier, and those Szep analyzes as highlighting the vulnerability of authors and readers.

Graphic embodiment also uses theoretical approaches that interrogate cultural assumptions, beginning with cultural studies of science via figures like Butler (1993, 2024a, 2024b) and Anne Fausto-Sterling (1992), who explain how empirical frameworks have been shaped by implicit cultural assumptions about the embodied aspects of sex and gender. Editors Cressman and DeTora (2021) explore the idea of making sense of embodiment, using the word “sense” (p. 17) to invoke both intellectual meaning and sensory experience. “Making sense of” (p. 16) embodiment acknowledges that conceptual, private, and personal experiences, as Szep suggests, are embodied as are socially embedded power structures.

Jeannie Ludlow (2021), in “Full Bleed: The Graphic Period at the End of the Menstrual Narrative,” presents a sustained discussion of feminism per se in connection with graphic embodiment. Ludlow explores the potential for graphic narratives to simultaneously present mainstream assumptions about sex and gender alongside feminist resistance to those assumptions. Michael Klein (2021) also describes feminist rhetoric in a broader discussion of undergraduate pedagogy; however, for the most part, authors wrestling with the idea of graphic embodiment, much like Squier, tend to treat feminism as a given, a way that women, men, and others may be seen to exist as members of the same species, as collaborators of lived experience.

A major question, then, is whether feminism writ large remains a specialized field of endeavor, or whether feminist approaches might be understood as a necessary underpinning to any form of intellectual endeavor, or as a subtext to certain forms of inquiry but not others. Of course, the term “feminism” can be used as a sort of shorthand for making sense of a broad variety of human experience rather than simply normalizing the first set of voices that founded Western modes of intellectual inquiry, drawing on the work of scholars like Donna Haraway (1991) to consider the interplay of humanity, the human-built world, and the natural world. Another way of understanding feminism is in a resistance to taking one firm position or making a single linear point, in keeping with observations of those like Helene Cixous (1976), who saw in women’s writing new modes of expression and knowing.

2.2. Speaking of Feminism

As media scholar Misha Kavka (2001) explains, “Feminism is ... a term under which people have in different times and places invested in a more general struggle for social justice and in so doing have participated in and produced multiple histories” (2001, xii). Contemporary feminism rests on theories of self-transformation (Hooks 2015) and intersectionality (Crenshaw 1989), aspiring toward relationality and inclusivity by reckoning with our movement’s shortfalls. Twenty-first century feminism encompasses diverse theoretical positions and methodologies developed via a recognition that patriarchal social structures intersect in multiple ways to shape the lives and experiences of all people, including those who belong to dominant groups. Just as recent feminist thought applies to all, the study of graphic embodiment presumes that scholars have a responsibility to consider the full range of human experience, which opens a space for the kinds of posthuman inquiry inspired by Haraway’s cyborg manifesto (1991). This work, which is viewed as a basis for feminist studies in science fiction, troubled many forms and boundaries of embodied experience, from race and gender to divisions between human, animal, and machine. Such approaches, while accepted now, began as radical: historian of science Jim Endersby (2021) has noted that pre-Enlightenment thinking, indeed, excluded from the category of ‘humanity’ women, children, many men, and other subaltern groups.

Feminism emerges from multiple histories and contexts that allow for advocacy, critique and self-reflection to uncover and address the myriad hierarchies and inequalities that can become naturalized in patriarchal social systems. Indeed, perspectives emerging from communities of color and other marginalized groups have critiqued feminisms that focus on some women (generally, white, straight, able-bodied, and affluent) at the expense of other groups. Contemporary feminisms, then, must respond to patriarchal political and social structures while remaining attentive to the ways those same structures limit their own understanding. One tactic for negotiating these sometimes-contested demands is, ironically enough, to eschew tactics in favor of responses. An example can be found in the now-canonical work of bell hooks, who argues for feminist approaches that require self-transformation concurrent with attempts to remake broader social and political realities. This transformation hinges on an ability to think critically about one’s own consciousness and beliefs, which creates, in turn, space for what hooks calls an “ethic of love,” a resistance to domination that promotes liberation for others in addition to transformation of the self.

Indeed, hooks’s call for feminists to remain open to transformation and revision echoes into the current moment. Sandoval advocates what she calls a “hermeneutics of love” (p. 69) as the foundation for analyses that transcend binaries like feminist/antifeminist or oppressed/privileged (p. 69). This analytical frame requires adaptation, making strategic and principled responses to the varied tactics and technologies of power and control. Sandoval’s approach is responsive, nimble enough to shift positions quickly, flexible enough to deploy seemingly divergent tactics simultaneously, and mobile enough to “weav[e] ... between and among ... ideological positionings” as needed (pp. 62, 58). Butler calls on twenty-first century feminists to honor the diverse perspectives and histories that have shaped contemporary feminism into “a highly contested field, with many paradigms that are always clashing or blending in some interesting and creative ways” (“What happened” 2024, p. 59). In Who’s Afraid of Gender? (2024), Butler calls for feminists to embrace this kaleidoscopic mode of feminist analysis, to engage the unsettled and enigmatic qualities of feminism that make it nimble, responsive, and humanistic (pp. 17, 21, 154).

This essay explores the possibilities for resistance to domination revealed in the application of a variegated and variable feminist analysis to three graphic texts, focusing on their different approaches to self-reflection, transformation, and liberation. While all three primary texts engage with transformation as feminist possibility, each addresses a specific aspect or instance of transformation, thereby illustrating multiple feminist potentialities within graphic embodiment and bridging genres like memoir, science fiction, and more verisimilitudinous fiction. Following Szep, we begin with a nonfiction example.

3. Positioning Élodie Durand

Élodie Durand’s, Transitions: A Mother’s Journey, invokes a variety of embodied metaphors to represent protagonist Anne’s attempts to reconcile her scientific training, feminist politics, and parental anxieties with her child’s gender transition from assigned female at birth to male. Transitions wades into contemporary struggles with how to make feminist claims about heteropatriarchal sexism without reinforcing either the biological imperative critiqued by second wave feminists or the gender binary critiqued by contemporary activists. How, we might wonder, can we critique gendered experiences in ways that promote ideological flexibility, enact the openness and cycles of reinterpretation that Butler calls for, and reflect the theoretical agility that Sandoval advocates? The answer, Transitions implies, may well emerge from embodied experiences. According to the comic’s paratextual notes, the narrative is a fictionalized graphic “diary” of the experiences of a family—a mom, (step)dad, and three children. The author’s note explains that the family’s names have been changed but implies that the narrative is otherwise true, at least in spirit, to the family’s experiences: “Between fiction and reality,” she writes, “the line is blurred” (p. 4). For example, one long, heart-felt email to the mother about transitioning is attributed to the real son whose relationship with his mom is represented in the narrative. As expressed in the comic’s title, this narrative is much less about the teenaged son’s gender transition than about the mother’s transition from skeptical and afraid to accepting and celebratory. The mom, called “Anne” in the graphic narrative, is a feminist and a university researcher in animal biology (p. 29). Anne’s difficulties with Alex’s transition do not inhere in religious belief or politically conservative ideology. And although some of Anne’s statements and missteps are consonant with what Butler (Who’s 2024) calls a “gender-critical feminist” (or, in popular parlance, a “TERF”) position at the beginning of the story, Durand challenges that label through a series of humanizing events that emphasize Anne’s self-blame, fears, and deep love for Alex. In fact, about one-third through the narrative, in a dramatic three-page sequence of Anne, her husband Mat, a high school science teacher, and their two younger children in a mountainous area, the adults admit their own discomfort to one another. At the bottom of a chaotic page of small, borderless panels, Anne drops her face into her hands and asks (misgendering Alex), “What’ll her life be like?” and then “Do you think we’re transphobes?” Mat tries to reassure her, and Anne replies, “Look, I thought I was open-minded… “ (p. 49). Her unfinished sentence directs the reader to the next page, a text-free representation of the four family members, each in a separate portrait-like panel. The boys are in bike helmets, but the image of family fun and safety is contradicted by the firm borders and gutters that isolate them from one another. The following page is a full-bleed wide image of mountains and the bike path, all four family members together again. In a small speech bubble dwarfed by the mountains and sky, Mat replies. “Me too. I thought I was open-minded” (p. 51). Scenes like this provide readers with a way to accept Anne’s and Mat’s challenges without excusing their resistance or Anne’s misgendering of Alex.

3.1. Defamiliarization as Embodiment

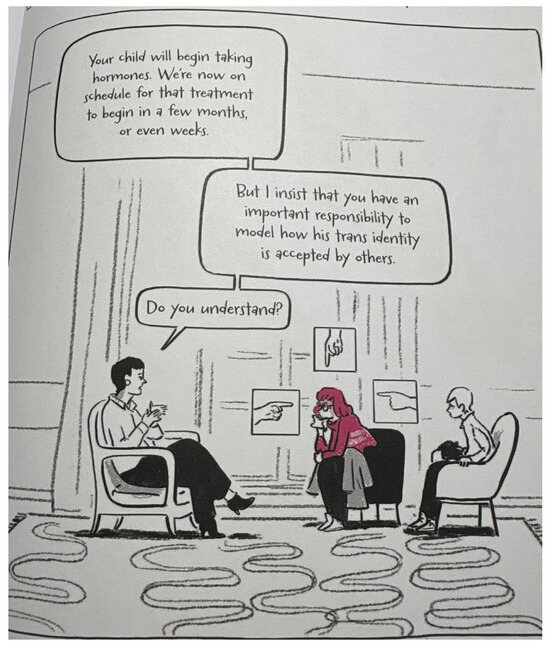

As readers, we are taken on Anne’s journey through the intertwined and sometimes conflicted relationship of text to image, to which Chute ascribes the “power of defamiliarization” (2015, pp. 198–99). Comics artists, Chute explains, create narratives “through a constant, active, uneasy back-and-forth” (199) between words and images and across time. Textually, Anne’s story oscillates among three time periods: a “present”; an extended analepsis beginning “more than two years ago” (p. 8), which is explicitly linked to Anne’s journals; and Anne’s memories of Alex’s baby- and childhood, represented as pages in a photo album. Visually and artistically, Durand direct readers’ understanding of these overlapping stories. Page structures and color choices convey both temporal and emotional shifts; storytelling happens on a standard two-column, four- or six-panel grid that is frequently interrupted by full-page panels or unbordered and de-gridded panels. The analeptic narrative is drawn primarily in black, white, and shades of gray, with occasional use of muted blue, to represent shadows or time, and pink. Anne’s vivid pink hair is often the only splash of color on a gridded page, suggesting the manga tradition of assigning central characters red hair to represent strong emotions (Poe 2022). Durand typically draws her characters’ clothing in black, white, and gray, although Anne is frequently nude, implying that she feels exposed in her difficulties; in one particularly emotional scene, Anne is confronted by Alex’s psychologist while wearing a pink sweater that matches her hair (pp. 74–84; Figure 1). When full-bleed or ungridded pages interrupt the narrative, they frequently use color very differently, to represent different aspects of Anne’s emotional or intellectual transitions. On “[t]he night of the announcement,” when her teenager “told me she was a boy,” Anne’s anxiety keeps her from sleeping. Three unbordered panels drawn primarily in red and pink express her emotions; the visual vocabulary of these panels emphasizes that Anne’s emotions are embodied. In the top panel, Anne’s face, a black silhouette with stark, round, white eyes, appears to float in a chaotic stream of red and pink. In the second panel, Anne’s anxiety becomes vivid red intestines with a snake’s face on one end, hanging outside of and curling around her abdomen. In the third panel, the snakes multiply, morphing into three red snakes twining her entire body, enclosing her in a hanging basket of snake bodies. Around Anne’s pink body and the red snakes, the declaration “It’s my fault I had her too young” floats in large, red, hand-lettered words (p. 16).

Figure 1.

Durand uses the color pink to signify Anne’s emotionality. Transitions p. 81. Copyright © Élodie Durand. Used by permission of the author.

Throughout the narrative, Anne’s emotional and intellectual shifts are graphically embodied in a way that invites readers to witness her transition. Although Anne’s teenager, Alex, is the person who is transitioning in the analeptic narrative, Alex’s appearance in the present and the analepsis never changes; he is consistently represented as a thin boy, taller than his mom, with a mop of blond hair and bright blue eyes. In fact, his appearance remains consistent even though throughout the narrative, Anne shares some of the changes he goes through: “Alex’s voice got deeper. His beard started growing, too” (p. 144). After a particularly difficult night when one of Alex’s friends has to be hospitalized, Anne narrates (misnaming Alex), “while putting away laundry, I discovered a prescription in Lucie’s room, on her desk” (p. 99). This text is accompanied by a blue-and-white panel showing the pharmacy bag. The next panel shows a syringe in a sterile wrap, outside the bag. Anne’s struggles to grapple with reality are reflected in the text, “Alex had started his hormone treatment” (p. 99). These two blue-and-white panels reveal a good bit about Anne’s process of transition. We can infer, for instance, that Anne removed the items from the pharmacy bag, suggesting both her surprise and a lack of respect for Alex’s privacy (he is eighteen). At the same time, the shift from “Lucie” to “Alex” in these two panels suggests, as does the use of blue instead of black ink, that Anne is moving from a strictly binarized, or black-and-white, perspective to a more fluid way of thinking about Alex’s identity.

3.2. Genre-Inclusive Iterability

In addition to the three arms of Alex’s and Anne’s story, Transitions includes one- and two-page summaries of resources Anne is reading throughout her journey (most of which Alex provides to her). These summaries are indicated by a bright, sunshine yellow banner at the beginning of each. For instance, immediately following Anne’s and Mat’s interrogation of their own open-mindedness, described above, is a representation of the German language film Fri um jeden Preis: Albaniens Schwurjungfrauen (produced by Filmkantine 2019, and cited pp. 52–3 in Transitions). The narrative is also punctuated with full-page silhouettes of vogue dancers. These are vividly colored and unlike most of the rest of the art. Durand also uses colors to mark Anne’s and Mat’s interactions with science, almost as if to suggest that science is simultaneously more complex and representable than emotion. As Anne begins to grapple with Alex’s transition, she turns first to her primary area of expertise: animal biology (p. 42). On a strongly gridded and brightly colored page, Anne outlines some of the many ways animals, birds, and bacteria challenge the human-centric notion of sex binarization. Immediately following is a two-page sequence in which she critiques the popular cartoon “Finding Nemo” for its scientific inaccuracy regarding gender. This concludes with a single borderless panel in which Anne says to Mat, “Our classical scientific conception of male and female isn’t relevant at all” (p. 44). Durand has kept vague the visual markers between the present and the analeptic narrative; it is likely that this sequence is set in “the present,” given Anne’s insistent tone regarding what science has gotten wrong. Still, there are no clear indications of this in the text, and there are multiple moments in the analeptic narrative sections when Anne’s comfort and open-mindedness fluctuate widely. By guiding readers to read through temporal shifts and uncertainties, Durand asks readers to embody along with Anne and Alex the iterability of transition processes.

3.3. Scrawls, Scribbles, and Squiggles as Embodiment

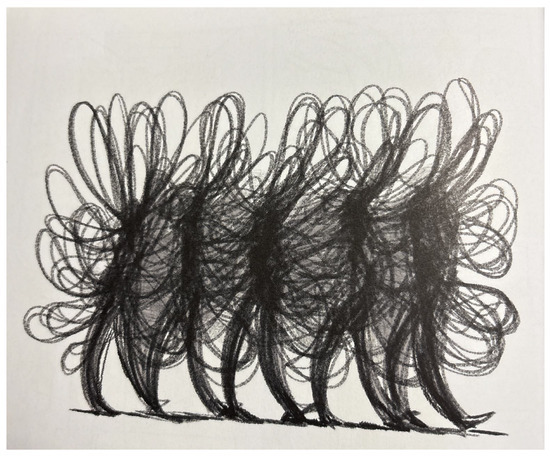

By imbricating the characters’ embodiment with the readers’ in a narrative about gender and political transitions, Durand’s text is both esthetically and methodologically feminist. Chute reminds us that a text is feminist when it involves “claim[ing] a space for openly sexual female bodies—especially queer bodies” and “explor[ing] subject constitution in mutually inflected private and public spheres” (2010, p. 177). In Transitions, Alex’s representational consistency mark his gender identity as steadfast. Anne’s body, in contrast, is visually erratic, signifying her own transitions from fearful skeptic to accepting mom and then to trans ally and advocate. Durand represents Anne’s mutability through a diverse series of artistic effects. Beginning early in the narrative, Anne’s figure is occasionally obscured by soft, rounded overlapping graphite ovals that remind one of a child’s energetic scribbling (Figure 2). At times, the scribbling moves above many penciled human-shaped feet, positioned to represent walking (pp. 7, 76, 134), and sometimes it morphs out of or into Anne’s hair as her face and figure emerge from or disappear into the scrawls (pp. 22, 89–90, 110). These scribbles that sometimes overshadow and sometimes symbolize Anne’s body—or, more specifically, Anne’s embodied discomfort—are powerful examples of the material relationships evoked by non-pictorial graphic imagery, as explained by Szép in Comics and the Body (Szép 2020). Szép describes the ways scribbling can be used to “visualize the subjective experience of how [a represented] body feels”; at the same time, scribbling can also invoke “an environment of thought” for the character (p. 167). Readers of Transitions can almost experience Anne’s resistance to Alex’s coming out and her anxiety about her child’s identity, as they follow the intensity of the scribbling through the text. At the same time, Szép argues, scribbling can reify a relationship between reader and graphic artist by “connect[ing] the embodied work of the drawer and the embodied work of the reader” (2020, p. 173). The embodied relationships incited by these scribbled figures are enabled by what McCloud called “amplification through simplification” (1993, p. 30). As McCloud explains, the more realistically and consistently a character is drawn (like Alex), the more readers are encouraged to identify that character as an individual; in contrast, the more iconically (that is, less realistically) a character is drawn, the more the readers are able to “inhabit” the figure on the page, thereby “becom[ing]” the character (1993, p. 36).

Figure 2.

Scribbles signify Anne’s anxiety while inviting readers’ embodied empathy. Transitions 76. Copyright © Élodie Durand. Used by permission of the author.

When readers are challenged to witness Alex’s heartbreak through his representational consistency while identifying with Anne’s struggles to accept and support her son, as represented by her iconicity, we find ourselves in a narrative space that enacts both parts of Chute’s definition of a feminist text. Transitions simultaneously provides a space for Alex’s queer body and masculine subject constitution, while exploring Anne’s transitions through both the private sphere of the self and the public sphere of the comics’ reading experience. Chute describes this complex reading process as inherently feminist, as a challenge to the primacy of the patriarchal gaze. She explains that when reading graphic narratives (particularly graphic testimony, memoir, or life writing), “the reader ... is not trapped, is not passive” in relationship to the story. Comics, Chute argues, “allo[w] a reader to be in control of when she looks at what and how long she spends on each frame.” In this way, the reader of comics is “a necessarily generative ’guest’” in the narrative world (Chute 2010, p. 9). When those comics are handmade, they are, she suggests, particularly collaborative and intimate, esthetically and methodologically feminist.

3.4. The Grammar of Graphic Feminism

Chute locates graphic texts’ methodological feminism in the interplay of feminist theory and “the grammar of comics,” as this dynamic applies to texts that explore “positionality, location, and embodiment” (2015, p. 200). Transitions employs various aspects of the grammar of comics to mark Anne’s feminism and its evolution within the narrative. One particularly compelling example is a two-page layout of small square panels floating ungridded next to captions that represent Anne’s voice. Some of the panels are completely blacked in while others are blank white; these checkerboard-like panels, randomly arranged on an expanse of white space, echo both the binarized thinking that Anne is struggling with and the disorganized quality of her thoughts. Three white squares contain parts of Anne’s body: first, her profile from the mouth up; then a disembodied hand with one finger pointing accusingly; and finally her profile with her pointing finger facing away from her face. These fragmented embodiments enact Anne’s fragmented thinking. On each page, a rectangular white panel contains narration. On the left, Anne’s retrospective narrative voice says, “Every discussion only adds to the misunderstanding and worsens our dialogue bit by bit. Lucie is more and more closed off” (p. 64). On the right, it continues, “Attacking ... victimization ... paranoia ... have all been creeping into my speech for weeks” (p. 65, ellipses in original). These narrational lines are in serifed typeface, invoking both electronic reproduction and critical distance from the highly emotional incidents presented on these pages. The captions for the small square panels, by contrast, float alongside them and are hand-lettered; some captions repeat things Anne has apparently said to Alex, such as “One opinion isn’t enough!” “How can you be sure that your therapist is giving good advice?” and “Your little friends are behind it all!” Others represent Anne’s overtly feminist, albeit clumsy, attempts to assign responsibility for Alex’s gender transition: “It’s society’s fault”; “Endocrine disruptors, from those anti-gay morons”; and “It’s the patriarchy’s fault, all this machismo.” On these pages, Durand uses the grammar of comics to draw out readers’ empathy for both Alex and Anne while demonstrating Anne’s investment in feminist analyses of the gender and sexual norms (“patriarchy” “anti-gay morons”) that she is simultaneously imposing on Alex (pp. 64–65).

The hand-lettered captions also serve to remind readers that this story is about real people’s experiences, even as they encourage our identification with or empathy for the characters on the page, enacting the embodied textuality described by Chute and cited previously. The overall effect of this two-page spread is that the temporally more distant words, expressed in Anne’s direct address of Alex, become more immediate to the reader than the temporally current narration. The contrast of the typed narration with the hand-lettered captions encourages readers to be aware of many bodies, simultaneously: Anne’s, invoked in the three fragmented images of her; Alex’s, as an absent presence on these pages; Durand’s, as the hand behind the lettering; and our own, as our usual reading strategies are interrupted and destabilized. This latter awareness is explained in Eszter Szép’s Comics and the Body. Szép notes that a comics’ grammar of narrative and formal “strangeness” (p. 164) can serve to make readers differently aware of our own embodiment and its relationship to reading (pp. 163–65). Thus, through the randomized placement of text and image in strategic tension with bichromatic black-and-white blankness, Durand directs readers to pay attention to Chute’s three primary aspects of feminist thought: “positionality, location, and embodiment” (2015, p. 200).

In Transitions, Anne’s feminism is a source for both her initial skepticism toward Alex’s gender transition and her eventual political transition from skeptic to ally to advocate. Because the graphic narrative is organized around three distinct, but not always clearly differentiated, time periods (the diegetic present, the analeptic time of Alex’s initial coming-out and Anne’s transition, and the photographic memories of Alex’s childhood), the relationship between Anne’s feminism and her intellectual and emotional shifts is both iterative and ambiguous. Early in the narrative, a woman friend says about Alex’s transition, “Apparently, there’s some message about femininity that didn’t get through” (p. 45). As they process this later, Anne cites a canonical 20th century quote from feminist theorist and historian Joan W. Scott, “Gender is a primary way of signifying relationships of power” (p. 47). Anne elaborates on the cultural message about femininity: “Don’t make waves, know your place, be smart ...” (p. 48, ellipses in original), emphasizing its messages about power. In these early pages of the narrative, Anne’s wrangling with her own inability to accept Alex’s transition even though she understands gender as a social construction is represented visually as wrestling. As Anne quotes feminist definitions of gender as a social construct (p. 36), the words caption a panel in which two white, featureless figures grapple awkwardly and painfully, holding one another by the face and neck as each tries to gain prominence. A few pages later, after a particularly charged exchange with Alex, the figures reappear in a four-panel, textless sequence and with one important difference: one figure grows increasingly red in each of the panels. By the fourth panel, one figure is fully red and the other is white (p. 41). After Anne’s friend makes her comment about femininity, the wrestlers reappear, illustrating the Scott quote about power. On this three-panel page, the red figure is joined by two others, and the three red figures subdue the white figure, forcing it to the ground (p. 47); this is the last time we see the wrestlers.

As the narrative progresses, Anne’s wrestling evolves into a dance with feminism, science, and love. After finally talking with her own parents about Alex’s transition, Anne is depicted iconically, dancing awkwardly atop a series of nearly-straight vertical lines on a three-panel page. In the top panel, she narrates, “I kept trudging forward ... I am getting informed ... I am learning ... I fluctuate” (p. 132, ellipses in original). In the bottom two panels, the lines below her feet morph into scribbles. Anne goes on, “I would like to go quicker, to be an ally, to detonate all the gender stereotypes that shape me ... “ (p. 132). Two pages later, her narration continues, situating her transition from an earlier phase of feminist thought to a more contemporary one: “I learned the word sisterhood. Alex talks to me about “empowerment” (p. 134). As Anne dances awkwardly across this four-panel page, morphing into different embodiments, she connects her learning about transgender to her identity as a woman (“I become more fully aware of the social, cultural, and political role of my own gender”) and to her feminism (“The battles against transphobia, sexism, racism, homophobia, and classism are communal ... power struggles”) (p. 134, ellipses added). Finally, she weaves her motherhood into this dance: “I think about Alex ... his fight, his strength, his courage. Our society could just leave our bodies alone ...” (p. 134, ellipses in original). This is a turning point in the narrative; although Anne continues to struggle and make occasional mistakes, her commitment to Alex is now fully integrated into her feminism and her identity as a mother. On the first panel of the very next page, Anne dances atop a rainbow, symbol of the LGBTQIA+ movement and a few pages later, she appears wrapped in a rainbow flag, declaring her intention to “go to war” if Alex has to confront discrimination (pp. 135–9).

3.5. Freeing Gender and Feminism

One of the most striking images Durand employs to think about the relationship between Anne’s feminism and her advocacy for Alex is a bird. Early in the text, Durand establishes Anne’s professional attention to birds and the ways gender in birds is different from gender in humans (p. 42). In a particularly beautiful segment, Mat and his sons, Pierre and Malo (Alex’s younger half-brothers), find a redstart. They capture it gently, band it, and record it, and then let it go. The redstart is a dark bird with a brightly colored breast (similar to an American Robin), but Durand draws this one with all the colors of the rainbow. In a full-bleed image of the bird’s head and torso, both its dark head and orange breast are shaded with vivid colors. As the boys and Mat handle the bird with care, their conversation takes on subtle meaning. As they bring the bird into the house, Pierre asks, “Can I set him free after? Huh, Dad?” As he talks the boys through the banding process, Mat explains, “I’m writing down the band number, his general appearance, and his sex. You see, birds don’t have external genitalia. But this is a male. I can tell that from his plumage” (p. 114). With this reminder that a body need not have external masculine genitalia to be “male,” Mat gently readies his sons to hear about Alex’s transition. He shows the boys how to hold the bird with care and how to let it go: “He’s fragile, but this way he’ll be safe” and “take him like this, delicately” (p. 114–5). After Pierre releases the bird, Mat explains Alex’s transition to him. He says, “In our society, the words ’sex’ and ’gender’ are all mixed up. It isn’t like that everywhere in the world” (p. 116). Later, he tells Pierre, “Alex is transitioning so his body aligns better with who he is, to live his life as best as possible. Do you understand?” Pierre replies awkwardly, “I dunno. Yes. I think” (p. 116). At the same time, Anne is explaining to the younger Malo, “... if you sister changes physically right now ... it’s because she feels like a boy” (p. 117). While this explanation, on its own, could be read as transphobic, Anne’s next words signal her intention to make transitioning legible to a young child. Hormones, she explains, will “hel[p] her match how she feels.” She gently moves Malo from one reality to another with deliberately chosen language: “Lucie’s shape and voice are going to change bit by bit. She could even start growing a beard.” Finally, she presents to Malo what is expected of him, saying “she picked a new name for herself: Alex. If you want, you can call her that now and say ’he’ when you talk about him.” Malo responds with typical little kid embarrassment, “Alex is a gross name!” But rather than respond to that, Anne simply asks him if he understands. “Yeah!” he replies. “Lucie is a boy” (p. 117). The contrast between these two conversations demonstrate both the parents’ awareness of the two boys’ difference in age and ability to understand the complexity of transition and the difference (at this point of the story) in the parents’ comfort with Alex’s transition. Durand sets her readers down into this complex reality with openness and simplicity, with Malo’s declaration, “Lucie is a boy” (p. 117).

Soon after the narrative segment about the bird, Anne begins showing her own new plumage; although her skin remains white and her hair bright pink, she begins to wear more colorful clothing, which she obtains from Alex’s closet, “I wear the clothes that fit me and that he doesn’t want to keep anymore” (p. 139). Soon, the artwork is echoing Anne’s transition. Storylines that were previously black, white, gray, and pink are now punctuated with yellow, teal, orange, purple, and blue. One full-bleed panel suggests Anne’s rising out of a dark puddle, but her face is almost impossible to discern, as it is created with brightly colored dots suggesting pixels or the work of Roy Lichtenstein. As Anne begins to take her new-found transpositivity to work and share it with her students and coworkers, the pixelated representation of her coheres into a figure walking across a white field. The figure has the feet and legs of a person and the head of a bird. Its body is wearing a rainbow striped sweater. We first see the entire figure in a wide shot (p. 159) and then a close-up (p. 160). The bird ushers the readers through a six-page email from Alex to Anne that explains the challenges of his transition, the role she and the family played in those challenges, and how he understands his transition as “one of the best things to ever happen to me” (p. 161). This email, which is attributed in the author’s note to the real person on whom the character of Alex is based, holds Anne and the family accountable in no uncertain terms, “When you expose yourself to misunderstanding and rejection by your relatives, by society, by future employers and lovers ... you have to be determined” (p. 164). Alex also responds to the stereotypes and accusations Anne leveled at him early in the narrative. “Today,” he writes, “we can clearly establish that, no matter what anyone says, it wasn’t some whim. It wasn’t some social mimicry ... or a confusion around my femininity” (p. 164). After writing clearly and defiantly about the negative effects of the accusations and stereotypes and about the positive effects of transitioning (“I have faith in who I have become” and “I am not worried about my future” [p. 165–6]), Alex ends his email with love, “I have a cause to fight for. I have you, and then I have myself ... Everything will be fine. See you soon. I love all four of you so much” (p. 166).

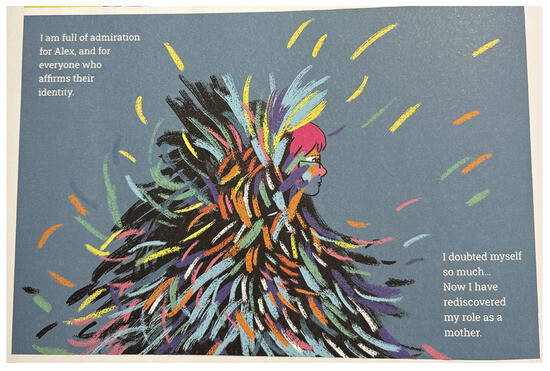

In a short epilogic segment after Alex’s email, Anne narrates her own transition success. On a two-panel page representing Anne as the bird, she writes, “Today, I don’t mess up anymore. Saying ’Alex’ and ’he’ has become second nature.” The Anne/bird in the top panel is mostly black, echoing and transforming the “scribble” person of the early pages of the narrative. The scribbled lines coalesce into representation, suggesting feathers, and Anne’s human face peeks out from them. In the second panel (Figure 3), the feathers are multicolored and rainbow-like, and Anne’s face and pink hair appear to emerge from their energy. Her narration continues, “I am full of admiration for Alex, and for everyone who affirms their identity. I doubted myself so much ... Now I have rediscovered my role as a mother” (p. 170, ellipses in original).

Figure 3.

Anne’s successful transition is represented by a colorful bird–human hybrid. Transitions 170. Copyright © Élodie Durand. Used by permission of the author.

4. Situating Tillie Walden

It is perhaps unsurprising that Durand’s graphic biographical work lends itself to a feminist analysis consistent with Sandoval and Butler’s calls for flexible feminism and an understanding of embodied vulnerability via Szep. But what might also be offered in fictional works? This section considers Tillie Walden’s On a Sunbeam (2018; https://www.onasunbeam.com) and Are You Listening (2019), as enacting a witnessing function of comics suggested by Chute (2016), which dovetails with the kinds of blurred identities Haraway describes and Szep’s model of vulnerability, which explores “the unique potential of comics as a medium to invite engagement” (p. 17). Walden’s graphic novels also enact multiple histories and thus must simultaneously grapple with myriad questions, including social justice, transformation, self-reflection, and flexibility, in parallel, in much the same way as individuals must negotiate various nuances of human experience. Indeed, Walden illustrates the fluidity by which humanity, animals, and the environment become embodied and undergo transformation, also playing with narrative expectations—including the grammar of comics that Chute (2015) refers to—in part by mashing up literary genres. The idea of witness here connects with Cressman’s (2021) treatment of embodiment in graphic pathography, which considers the concept of reading-as-witnessing by inspiring empathy and boundary crossing, consistent with Szep’s analysis of nonfiction comics as promoting empathy between a “vulnerable drawer and a vulnerable reader” (p. 8).

The analysis presented next derives in part from prior conference papers (DeTora 2023; DeTora 2024) and forms a contrast with Jessica Baldanzi’s excellent reading of On a Sunbeam as articulating lightness and weight among embodied characters who experience gender bending (Baldanzi 2023, p. 124) and rebirth into a normative nuclear family (p. 131) unit within defined physical spaces. Although Baldanzi links this rebirth with “a more viable, more flexible, and thus more sustainable community in the face of ‘exile,’” (p. 131), following Haraway, much of this analysis trusts the material universe to behave as a setting. The current analysis centers the embodiment of the text and the reader as co-constitutive and mutually transformative, extending the kinds of interactions Szep analyzes into the nature of textual/comics production itself. While Szep’s notion of reading and creating as embodied activities (p. 8) is relevant, Walden pushes these embodied boundaries in a novel way, treating geographies, universes, and genres as subject to the same forces as other bodies.

Comics are an ideal form for such a stance. Chute (2016, 2017) emphasizes the hybridity of the medium as deriving from its grammar—an interplay of image, text, space and gutters—and focuses on the notion that feminism is relational. Representations of embodied experience in graphic narratives can shed light on deeper questions in human experience, and, for Chute (2017), the “immediacy” (p. 241) of comics is complemented by “its diagrammatic ability to display otherwise hard-to-express realities and emotions” (p. 241). The grammar of comics allows the reader to fill in the missing elements, to build their own interpretation as they witness the work. Thus, the reader’s engagement helps embody the comic’s characters, settings, and plot, functions Szep links with vulnerability, empathy, and embodied reading (p. 9). Walden, however, also plays with the idea of diagrammatic display by calling into question differences between settings and characters and thereby complicating the functions of witness, vulnerability, and empathy.

4.1. Worldbuilding as Embodiment

Walden is acutely aware of the interplay between the embodied experience of reading and the worlds she creates. In a Medium interview with Nicolaia Rips, Walden comments that she tends “…to think not of your world as a background, but as another character. It’s this really special element that cartoonists get to have.” Rips’s description of Walden’s comics as “genre-defying” foregrounds Walden’s idea that the world is not just a “backdrop.” As Walden notes, in comics, “it’s even more important to make the space somewhere that the reader wants to see more of and wants to be sort of invited into.” Walden then adds, “I always think about obstructing the reader’s view. Like partially open doors or stairways to make the reader want to go further into a room.” This ironic mechanism allows the reader to co-construct diegetic meaning and reframes the idea of character as fluidly connecting human, animal, machine, and environment with the reader, inviting the type of embodied co-creation Szep comments on (pp. 8–9). Walden also anticipates the reader’s response while assuming the reader can go further into diegetic spaces, blurring the lines between lived space and fictional space, thus extending and complicating a possible function of witness that would normally assume a more stable distance between a fictional world, its characters, and the reader. Walden plays with this separation and hence the distance between self and other by presenting worlds as embodied characters and therefore also vulnerable to change by and through reading.

Important for a feminist reading of Walden’s work in this context, then, is a kind of porousness to normally assumed categories that Haraway considers for cyborgs: animal, machine, human, robot, environment, gender, race. The instability of physical environments in On a Sunbeam and Are You Listening signals an opportunity for growth, change, and the co/re/de-construction of human, animal, technology, and environment. In this view, embodiment is relational and co-constitutive, which contrasts somewhat with Baldanzi’s treatment of nonbinary embodiments for human characters who occupy concrete material spaces. While Baldanzi comments on many interrelationships, certain realities of physicality—like gravity (p. 118)—seem assumed, but are shown to be vulnerable to outside forces as well. These relationships extend beyond the reader–creator vulnerability Szep comments on, in part because Walden is playing with the idea of partiality and incompleteness and in part because she also presents diverse plots engaged in different sorts of action. In fact, Walden invites empathy for worlds as characters as much as for human characters.

4.2. Texas-Bending in Are You Listening?

Are You Listening is set in a verisimilitudinous present that flirts with science fiction. We follow Bea and Lou, two women who prefer the love of women and come out to each other (p. 109) while guarding a cat from the men of the Office of Road Inquiry (p. 123) in a fictionalized version of west Texas. Bea and Lou are running away from home in the aftermath of trauma: Lou lost her mother (pp. 267–268), and Bea was sexually assaulted by a family member (pp. 199–201). The novel could be interpreted as magical realism because the Road Inquiry characters, the cat, the highway, and even the main characters all seem to morph suddenly and unrealistically as embodied entities (pp. 213–223). Pursued by the shadowy figures of the Office of Road Inquiry, Lou and Bea find roads suddenly elongating (p. 220), communities appearing out of nowhere (p. 246), and time and space seemingly transforming (p. 269). In this Texas, all embodiments are unpredictable: even lakes pop up suddenly (p. 117). Trees, which might seem to represent stability in a shifting landscape masked by snow and darkness, might suddenly burst into leafiness (p. 160).

Bea and Lou assume that Texas is ordinary, so it seems that the cat, Diamond, must be magical, a sentiment echoed by the Office of Road Inquiry (p. 219). Lou and Bea return Diamond to West, a Texas town not on any map, but known to every person they meet. Their first attempt (pp. 160–164) fails, but Bea later reaches West to learn that Diamond is only an ordinary cat, and Texas itself is special, “the perfect blend of giant and tiny” (p. 253). Cats simply see the potential for magic in the land around them. The real problems come from the Office of Road Inquiry and other characters (like Lou and Bea) trying to impose order on the land rather than accepting changes in terrain, time, and weather. Time and space are mildly unpredictable, or at least seem so because of the effects of wind, rain, snow, and personal perception. Indeed, the main tension in Are You Listening is revealed to be that Lou and Bea imagined a science fictional fantastic because they were not listening to the land (p. 253), themselves, or each other (p. 204). Walden illustrates these problems by playing with gutters that slant and wiggle (pp. 250–258) as well as obscured images and partial text (pp. 199–201) during traumatic events. Tellingly, once Bea learns to listen to Texas (p. 254) and forgive herself (p. 205), she learns to drive (p. 302), and the characters can proceed into an unknown future.

An astute reader will identify the apparent magic in Are You Listening as stemming from trauma, the core issue for Chute’s Disaster Drawn (2016). Walden presents a masterclass in illustrating the effects of trauma on perception and memory, a function Chute (2017) associates with the unique ability of comics to “display” (p. 241) complex experience. In fact, though, Walden’s comic hints that trauma and loss may only appear to influence the environment around human characters. Are You Listening, in providing the reader with a specific answer to the question of whether a cat is magical, opens up a much broader possibility for inquiry, self-exploration, and curiosity in a world subject to change without notice. If a cat can embody and channel the inherent magic that exists in the perfect blending of very small and very large, in a place where “the land, the sky, it’s got its own mind” (p. 253), then the possibilities for human experience are boundless. The comic teaches the reader that any belief that physical reality must follow certain rules is a human problem, and the world is entitled to a mind of its own. The text, then presents an inherently feminist vision by troubling divisions between people, places, animals, and things, by showing how self-reflection can change the world, and by inviting empathy and love for the land as well as the people in it. This positionality invites the type of self-reflection and empathy hooks and Sandoval describe through love.

4.3. Genre-Bending and World-Building in on a Sunbeam

Walden’s science fiction opus On a Sunbeam goes beyond destabilizing relationships between human, animal, and world by playing with genre in ways that trouble the grammar of graphic narratives that Chute (2015) describes. Fictional genres here function conceptually in the same way that a partially open doorway can operate visually, inviting further exploration. The reader can then build the sense of spaces and/as characters in part by constructing and interpreting narrative conventions, which also become vulnerable to change during unfolding events. This interplay of reader and comic might be seen to enact a feminist vision of transformation and self-reflection paralleled by diegetic events. On a Sunbeam requires responsive and flexible reading to negotiate these terrains, an ability to navigate multiple worlds, histories, and genres to make sense of embodiments from the individual to the geographic to the interstellar. At all levels, the comic invites empathy for human characters, creatures, and worlds.

Walden begins by introducing both the main character, Mia, and the reader to shipmates Jules, Elliot, Char, and Alma (pp. 4–5; https://www.onasunbeam.com/#/chapter-one/, accessed on 17 June 2025), who live together as a sort of nuclear family who work together in outer space. In learning that Elliot is nonverbal and nonbinary (p. 6), it seems, perhaps, that the narrative is LGBTQ+ science fiction, yet the reader soon learns that Mia is also reliving the day five years earlier when she met Grace at Cleary’s School for Girls (p. 17). The tropes of the boarding school series novel blend with the outer space adventure, a new narrative and set of characters set against Mia’s past. Ultimately, while On a Sunbeam mashes up various fictional genres, its surface resolution centers on a romantic reunion with Grace (p. 472; https://www.onasunbeam.com/#/page19/, accessed on 17 June 2025) that echoes the “love” that hooks and Sandoval associate with feminism. Baldanzi sees this reunion as reinscribing a nuclear family (p. 131); however, competing demands of various genres suggest other possibilities. If the ultimate resolution is lovers reunited, the reformation of the nuclear family is then a backdrop to this central event. On a Sunbeam, however, invites the reader to accept both readings simultaneously, to blend multiple histories and myriad possibilities, complicating and extending the type of embodied relationships Szep sees as mutual vulnerability between creator and reader (p. 9). By blurring the lines between character and setting and between the plot demands of various fictional genres, Walden creates a new form of hybridity that goes beyond the formal constraints of the comic’s pages or its grammar. In fact, while El Refaie (2019) considers the operation of metaphor in comics as ‘bidirectional,’ in Walden’s fictional space, directionality is also destabilized and multiplied, and therefore mutually constitutive both within the diegetic realities of the characters—some of whom operate metaphorically to each other as well as the reader—and between the reader and the text and the reader and Walden.

One mode of metaphor can be seen in a tension between Cleary’s and Mia’s present, specifically the first building she works on as a restoration project (p. 11). Cleary’s structure is stable and enduring (p. 42), while the present is fragile and incomplete, despite their formal similarity, foregrounding characters against the background of a tree in various reds and corals. When Mia wanders in the new space, she destroys a geography (64; https://www.onasunbeam.com/#/chapter-four/, accessed on 17 June 2025), beginning with a series of staircases. This scene illustrates an important distinction between Cleary’s as a materially solid, predictable setting, whose stairs remain stable (p. 61), and every other site in the novel where no embodied materiality is fixed or dependable. While Baldanzi sees these shifts as dependent on weight and gravity interacting with human bodies, these forces, too, also are subject to change without notice. Indeed, Mia’s quest to find her former lover wreaks destruction in part because her romance narrative, which is embedded in the past, collides with emerging stories that allow for fluid sites of embodied transformation while revealing past histories. Given the essential instability of present spaces and Cleary’s as flashback, its stability is potentially imagined, leaving Grace and Mia’s past love story as a central grounding point of the novel. The early collapse of a work site portends trauma to come and not just the separation of Char and Alma’s family as a direct result of the mishap. Mia has unknowingly wandered into a dangerous past history, into conflicts that extend far beyond her desire to ensure that a teen romance ends on at least a polite “no pressure” (p. 478) note.

Walden skillfully layers the elements of various fictional genres into the grammar of comics (Chute 2015), beginning with science fiction and the school story before layering in the heroic epic. On a Sunbeam thereby enacts a flexible approach to genre that parallels Sandoval and Butler’s call for different sorts of feminism. Its physical genres, too, are transcendent and transformative. The work even began as a digital comic (https://www.onasunbeam.com), bridging delivery media for the hybrid forms commented on by Chute (2016), El Refaie, and others. Only the reader’s outside vantage point can access these myriad nuances, providing an anchoring point for empathy with the artist as well as the individual characters and settings.

Of interest, what might appear to be the most dramatic embodied transformations occur on the Staircase, Grace and Elliot’s isolated home world, where personal narratives take on epic proportions. The Staircase occupies a semi-mythical space outside star charts, making it invisible to the normal universe, but “full of something special” (p. 314). The Hills, Grace’s family, own this world and refused “all the offers to join treaties” (p. 315) that would “trample” (p. 315) its rich natural resources, and now must hide from “assassins” (p. 316). The Staircase and the Hills therefore embody a site teetering between human built and naturally occurring worlds, under constant threat by a violent politics that can be mitigated only by separation (https://www.onasunbeam.com/#/chapter-fourteen/, accessed on 17 June 2025). Every event in On a Sunbeam hinges on this fact, on the Hills’ determination to “protect this environment” (p. 316), “besides, no one understands that land better than those who live there” (p. 317), a group that includes creatures—beings from “a world beyond our own” (p. 410) as well as humans. Thus, the physicality of the Staircase, as Baldanzi also notes, blends human, animal (or creature), and environment as mutually influential and co-constitutive. It therefore troubles the kinds of essential divisions between people, animals, spaces, and things that can be counted on in Mia’s past. Indeed, and unbeknownst to Mia (and perhaps even Grace), a profound violation of the precarious balance of human, animal, and world in the Staircase originally allowed them to meet in the first place. It is illegal to enter or leave the Staircase, but six years earlier, then-outlaws Alma and Char had been hired to rescue Elliot and were able to use this knowledge to transport Grace to Cleary’s and home again (pp. 326–329). Thus, Mia’s romantic predicament transcends adolescent angst because it is predicated on prior interplanetary and interspecies conflicts that threaten to destabilize the universe, tales that have little place in a romantic narrative even as they invite empathy for a specific world and the creatures in it.

Two epic narratives then become intertwined (pp. 413–68) outside Mia’s sight and experience, inviting the reader into the backdrop of her history. Elliot, initially presented as benignly silent, is a hated criminal who “killed an ancient being” (p. 409; https://www.onasunbeam.com/#/chapter-seventeen/, accessed on 17 June 2025), the greatest possible crime in the Staircase (pp. 440–46) This past crime carries a freight of memory never made fully clear to the reader, a hint at Walden’s stated tendency to obscure the view. Interestingly, Elliot emerges as both vengeful and remorseless—“I’d do it again. I’d do it a thousand times” (p. 407)—before a near-death experience at the hands of the Staircases’ citizens. Meanwhile, Jules, initially characterized as a comic sidekick preoccupied by board games, falls underground (p. 371), a parallel to Mia’s earlier misstep. Jules, however, follows a native creature to meet a “Tessian Fox” (p. 442) that lives in an atmosphere “toxic” (p. 442) to humans. The matriarch of Grace’s family, hints that this fox, “our oldest creature” (p. 442) is the ancient being Elliot attacked, still barely alive. The fox’s willingness to connect with Jules—“something no one here has been able to do” (p. 446)—mitigates the crime of trespass. As Grace’s grandmother explains, steps had to be taken to protect the fox and allow it and the Staircase to heal (pp. 445–46). This sequence illustrates the codependency of the Staircase and its creatures while hinting that Jules was the key missing piece in an epic struggle, but present only because of Mia’s yearning for the love of an old schoolmate, the kind of genre mashup Rips comments on. Yet, as Baldanzi notes (pp. 131–32), Jules and Elliot return to type as soon as they are reunited with the rest of their shipmates (p. 504). All epic struggles remain invisible to their shipmates, fleeting, and tangible only on the Staircase.

The spaceship Sunbeam then reintegrates Char’s original crew with the stable environment of Cleary’s as Grace and Mia renew their relationship and the crew returns to family life (pp. 472–81). Their love, and the reunited family, mitigate struggle, poison, sickness, and even the gravest crimes against nature. While all is well in the safe romantic space of the ship Sunbeam, the rest of the comic hints that this resolution, like every other space and event yet presented, is subject to change without notice. Furthermore, the reader is left with an equivocal view of Mia’s shipmates, each of whom has revealed hidden depths, powers, and even violence on the Staircase. While this might seem to be a fairly ordinary sort of irony in fictional works, it also signals to the reader that for all their empathy, each character, world, and creature, much like Walden, may be blocking their view, inviting them to investigate further.

Reading-as-witnessing in On a Sunbeam and Are You Listening must manage blurring categorical lines of embodied experience between humans, animals, and worlds, informing and even deepening Szep’s notion of vulnerability by expanding empathy beyond creator and reader to worlds, animals, and environments. Walden’s novels also call into question the stability of natural environments, whether through perception and weather as in Are You Listening or poorly understood natural events in On a Sunbeam. Walden treats both characters and worlds as embodied entities which requires not only characters but the reader to constantly adjust and revise their understanding and themselves in the light of those readings, broadening their empathy. It is especially telling that the verisimilitudinous world of Are You Listening, while seemingly more easily explained, also leaves the reader with a much broader series of open possibilities than the much more complexly layered narratives of On a Sunbeam, where love conquers all.

5. Conclusions: Nimble Embodiments and Graphic Feminism

In On a Sunbeam and Are You Listening, readers must manage material shifts and changes within and around the characters, requiring a nimble, flexible mental response to the unpredictability of physical spaces and even textual genres. It turns out that embodiment includes the natural environment, the universe, and the animal world. Returning to early forms of feminism as a call for social justice and Endersby’s recognition that pre-Enlightenment thought excluded many people from humanity writ large, these graphic texts provide a platform for extending the idea of character, as Walden herself notes.

While the material setting of Transformations: A Mother’s Journey is more predictable, the representations of feminist and gender-inclusive embodiment in this graphic biography are similarly destabilizing and require readers to confront Anne’s—and our own—inflexibilities. Durand’s metaphorization of natural phenomena, such as the lake of confusion that Anne sinks into and then rises from in her dreams, infuse embodiment with a fluidity that highlights the tensions among feminism as politic, science as knowledge, and motherhood as experience. This fluidity, in Transitions, is ultimately represented by the animal world, which is symbolically positioned as engendering an adaptability to which we humans should aspire.

The stakes of the conversation opened by graphic embodiments are significant and grow increasingly so. In the context of increasing social polarization undergirded by global populism and neoliberalism, a more open and expansive understanding of feminism could be a legitimate vector for social justice work. In the twenty-first century, contemporary feminist discourse has not always responded persuasively to far right interventions against an array of feminist concerns, from reproductive justice to civil rights, from economic equity to educational freedoms, indeed, against the idea of personal autonomy writ large. While we certainly do not intend to claim revolutionary power for commercially published graphic texts, we do recognize that popular culture texts like graphic novels and memoirs can help shift perceptions by challenging expectations while simultaneously inviting empathy (see Chute 2015).

These three graphic texts present embodiment as unsettled and unsettling and, thus, consonant with the open and responsive feminisms endorsed by hooks, Sandoval, and Butler. They also mobilize love as they emerge from and resist the increasing politicization and polarization of neoliberal twenty-first century life. The power of these texts grows (sometimes unevenly) out of the critical dialogs they limn between graphic embodiment and what bell hooks has called “an ethic of love” (Hooks 2006, p. 243). As feminist scholars, we draw on that power as we continue to reach toward stronger and more inclusive feminist scholarship and comics studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and L.D.; writing—original draft preparation, L.D. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and L.D.; visualization, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. A small part of this paper came from part of a prior conference paper; however, the article is very substantively different and not based on a dataset.

References

- Baldanzi, Jennifer. 2023. Bodies and Boundaries in Graphic Fiction. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 2024a. What Happened to You in Brazil? WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 52: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 2024b. Who’s Afraid of Gender? New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Chute, Hillary. 2010. Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chute, Hillary. 2015. The Space of Graphic Narrative: Mapping Bodies, Feminism, and Form. In Narrative Theory Unbound: Queer and Feminist Interventions. Edited by Robyn Warhol and Susan S. Lanser. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, pp. 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chute, Hilary. 2016. Why Comics? From Underground to Everywhere. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Chute, Hilary. 2017. Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cixous, Hélène. 1976. The Laugh of the Medusa. Signs 1: 875–93. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173239 (accessed on 6 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 140: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cressman, Jodi, and Lisa DeTora. 2021. Introduction. In Graphic Embodiments: Perspectives on Health and Embodiment in Graphic Narratives. Edited by Jodi Cressman and Lisa De Tora. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressman, Jodi. 2021. The Embodied Witness of Graphic Pathology. In Graphic Embodiments: Perspectives on Health and Embodiment in Graphic Narratives. Edited by Jodi Cressman and Lisa De Tora. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwiec, MaryKay, Ian Williams, Susan Merrill Squier, Michael Jay Green, Kimberly Rena Myers, and Scott Thompson Smith. 2015. Graphic Medicine Manifesto. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeTora, Lisa. 2023. Rupturing the frame: Nonbinary Identification in Two Speculative Graphic Narratives. In Disrupting the Frame Part I. Disruptive Imaginations: Joint Annual Conference of the Science Fiction Research Association & Gesellschaft für Fantastikforschung. Dresden: TU Dresden. [Google Scholar]

- DeTora. 2024. Rupturing the Frame: Nonbinary Identification in Two Speculative Graphic Narratives. Framing the Unreal. Venice: Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. [Google Scholar]

- Durand, Élodie. 2023. Transitions: A Mother’s Journey. Translated by Evan McGorray. San Diego: Top Shelf Productions. First published in 2021. [Google Scholar]

- El Refaie, Elisabeth. 2019. Visual Metaphor and Embodiment in Graphic Illness Narratives. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Endersby, Jim. 2021. Women in Science Fiction. In How Not to be Human: Exploring Humanity Through Science Fiction. London: Gresham College. Available online: https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/scifi-women (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Fausto-Sterling, Anne. 1992. Myths of Gender: Biological Theories About Women and Men, 2nd ed. New York: BasicBooks. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, Donna. 1991. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, pp. 149–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 2006. Love as the Practice of Freedom. In Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New Edition. New York: Routledge, pp. 243–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 2015. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. New Edition. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Kavka, Misha. 2001. Introduction. In Feminist Consequences: Theory for the New Century. Edited by Elisabeth Bronfen and Misha Kavka. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. ix–xxvi. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Michael J. 2021. Body Talk: A Cross-Disciplinary Course on Embodiment and Graphic Memoir. In Graphic Embodiments: Perspectives on Health and Embodiment in Graphic Narratives. Edited by Lisa De Tora and Jodi Cressman. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludlow, Jeannie. 2021. Full Bleed: The Graphic Period at the End of the Menstrual Narrative. In Graphic Embodiments: Perspectives on Health and Embodiment in Graphic Narratives. Edited by Lisa De Tora and Jodi Cressman. Leuven: Leuven University Press, pp. 173–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, Arthur S. 2022. Manga and Anime Hair Color Meaning Explained. Fiction Horizon. 25 March 2022 (pop cult news e-zine). Available online: https://fictionhorizon.com/anime-and-manga-hair-color-meaning/ (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Sandoval, Chela. 2000. Methodology of the Oppressed. Book Series: Theory Out of Bounds; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Szép, Eszter. 2020. Comics and the Body: Drawing, Reading, and Vulnerability. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, Tillie. 2018. On a Sunbeam. New York: First Second. [Google Scholar]

- Walden, Tillie. 2019. Are You Listening? New York: First Second. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).