Abstract

Graffiti’s dual existence as both public art and illicit practice has generated sustained legal, cultural, and aesthetic debates. This article examines the role of anonymity in shaping how graffiti is recognized, regulated, and interpreted within both legal frameworks and artworld aesthetics. Focusing on the legal battle over 5Pointz, a prominent New York graffiti site that was whitewashed in 2013 and demolished in 2014, I analyze how the Cohen v. G&M Realty L.P. case reveals a structural tension between graffiti’s collective ethos and the legal system’s emphasis on identifiable authorship. Drawing upon legal studies, urban cultural theory, and aesthetics, this article explores how the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA) mediated the legal recognition of graffiti, often privileging curated, institutionally sanctioned works while rendering anonymous street art legally vulnerable. I further synthesize scholarly perspectives on 5Pointz to highlight how legal discourse constructs and delimits the status of graffiti within public spaces. Ultimately, I argue that anonymity functions not simply as an absence of authorship but as an aesthetic and political mode of experiencing the object, one that challenges traditional frameworks of artistic attribution and cultural legitimacy. By interrogating the legal and ideological forces that shape graffiti’s recognition, this article situates anonymity as a central, yet often overlooked, feature of graffiti’s critical and aesthetic power.

1. Introduction

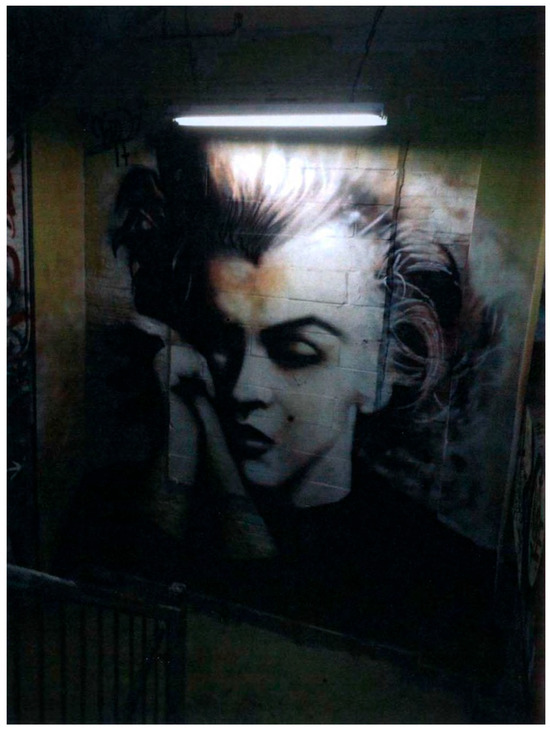

Relatively few people had the opportunity to stand in front of this portrait of Marilyn Monroe, spray-painted onto an uneven basement wall in a derelict button factory in Queens, New York (Figure 1). The cluster of defunct factories and warehouses, known internationally as 5Pointz, was slated for demolition in 2013 when its property owner, Gerald Wolkoff, whitewashed nearly the entire site in a single night. In the photograph I am now viewing, reproduced in Judge Block’s 2018 decision in favor of the artists whose work was mutilated by the whitewashing, Marilyn appears in the familiar, moody pose first captured by Ben Ross in a 1953 photo session (Cohen 2018). She gazes down and away; her mouth and eyes, partially open in Ross’s photograph, are better described here as half closed. The painting’s high-contrast color palette weds her plaintive mood with the black-and-white medium that conveyed her image for the 65 intervening years. The rectangular grid and rough surface of the cement blocks just below the thin layer of spray paint emerge under the astringent glare of an industrial fixture turned museum display light. While the fluorescent light heightens the white paint nearest her forehead and hair, the dark shading around her face draws our attention to the shadows near her clasped hands. Enhanced by the basement wall’s unevenness, Marilyn’s face and secret are brought forward as the sides of her face follow the contours of the concrete blocks. In the upper-left corner of this reproduction, admitted as official evidence in a court of law, the artist’s name is not fully discernible. If it were, the name would not read as a signature but as a tag: not “Carlos Game”, the artist’s name as attributed in the 5Pointz legal case, but the pseudonym “See-TF”.

Figure 1.

Marilyn by See-TF (Cohen 2018, p. A-11).

The painting’s notable verisimilitude with Ross’s famous photograph places it within a longstanding discussion of reproducibility and aura, drawing it into direct dialogue with Warhol’s 1962 Marilyn Diptych. Walter Benjamin famously defines aura as “the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be”, a formulation that locates aesthetic singularity in the simultaneous experience of presence and withdrawal (Benjamin 2006, p. 255). The artwork’s auratic presence is rooted in the “here and now” of the original’s unique existence, its irreducible presence in a particular place and moment (Benjamin 2006, p. 253). At the same time, the experience of distance registers the object’s historical embeddedness in ritual, sustaining its inaccessibility to immediate appropriation. By manifesting singular presence as a perceptual experience of distance, aura conditions authenticity and appears to secure an identity that can never be fully present. Paradoxically, it is precisely the “desire of the present-day masses to “get closer” to things spatially and humanly”, realized through reproductions that dissolve uniqueness, that Benjamin identifies as “the social basis of the aura’s present decay” (Benjamin 2006, p. 255).

In his essay “Andy Warhol’s One-Dimensional Art”, art historian Benjamin Buchloh argues that Warhol’s early work systematically dismantles the aesthetic premises of modernist painting by internalizing the visual logic of mass production and collapsing the boundary between high art and commodity culture. He concludes with a striking recognition: Warhol’s procedures, far from merely capitulating to the culture industry’s logics of commodification and visibility, “mimetically internalize and repeat the violence of these changing conditions” (Buchloh 2000, p. 513). In a passage that might be read as a revision of Benjamin’s own ambivalence toward aura’s decay through reproduction, Buchloh contends that the practices which “celebrated the destruction of the author and the aura, of aesthetic substance and artistic skill” also “uncovered the historical opportunity to redefine (aesthetic) experience” (Buchloh 2000, p. 513). The key here is that Buchloh identifies a space opened by the loss of traditional aura, one in which the terms of aesthetic experience might be reconfigured under conditions of reproducibility.

If Warhol’s silkscreen procedures make this reconfiguration thinkable, Marilyn makes it perceptible. Whereas Warhol’s silkscreen techniques, with their progressive obliteration of Marilyn’s publicity photo, enact the structural condition of loss through which aesthetic experience must now operate, the direct application of spray paint to a basement wall manages both to participate in the circulation of images and to generate an experience of aura. Marilyn’s double move, at once part of endless reproduction and yet uniquely anchored in physical space, highlights the painting’s tension between the replicable and the singular. As the subject veers between “Marilyn” and “a photograph of Marilyn”, the image becomes infinitely reproducible yet curiously one-of-a-kind, locked away in this basement.

In this contemplative depiction, Marilyn’s half-closed eyes and introspective pose signal an unavailability to the public gaze. Her elusive quality draws attention to how the painting’s title, Marilyn, attempts to pin down a presence that remains just out of reach. The result is an infelicity in naming: “Marilyn” designates a subject but simultaneously reveals her distance from that presence and from the name itself. In other words, insofar as the name “misses its mark”, the subject who eludes it gazes on herself. Here, “missing the mark” functions like a “minor” hamartia, one that does not propel viewers toward the tragic recognition (anagnorisis) of a fixed identity but rather opens the possibility of an anonymous performance. Instead of culminating in a re-alignment of name and subject, this unnamed “Marilyn” displaces the logic of recognition, ultimately rendering her a kind of spectator of her own objectified image. No longer merely herself, the anonymous figure whispers in the ear of her fellow spectators, narrating her own objectification rather than personifying it. The image becomes one that both is and is not Marilyn, unsettling expectations of what “Marilyn” means. What emerges here is a revision of “aura:” no longer anchored in the presence of a nameable subject, it becomes available through a perceptual opacity that refuses recognition. The painting’s half-withdrawn figure and the title’s self-awareness further indicate that reproductions inevitably leave something out: by transforming her most recognizable signifiers, i.e., eyes, mouth, and expression, this graffiti rendition of Warhol and Ross resists the mass circulation that cements her identity, opening up an aura now in the service of anonymity.

However, if the material immediacy of spray paint and concrete brings a sense of intimacy and authenticity to this highly publicized image, it also prompts us to consider how the visibility and publicity of street art are reconfigured in this basement setting. The clash of publicity and privacy embodied by the image of a celebrity intersects with graffiti as a spatially public art form, which here is denied the visibility that otherwise seems to be its raison d’être. In other words, Marilyn distills graffiti’s pull on the public eye and tempts us to imagine this basement wall as a portal not to individual contemplation but to an alternative form of sociality. Perhaps, for some, it becomes the hallway to a hidden club, engendering the gathering of publics in a repurposed space. Perhaps for others, it is the markings on the wall of a transitory space, like Moten and Harney’s stairwells and alleys that allow for the possibility of what they call fugitive activity. Through its half-lit, partially withheld presence, Marilyn offers not only a mode of aesthetic withdrawal but a political one: it gives form to a “we” that has been banned from congregating in sanctioned spaces, a “we” that may already or soon face censorship, capture, or criminalization. It is a collective subject not yet fully knowable because we do not yet know what powers will attempt to name, discipline, or erase us. Anonymity does not merely obscure identity; it protects the conditions under which a shared “we” might begin to emerge and gives us the aesthetic techniques to do so.

On one hand, by taking this famous photograph of Marilyn Monroe as a subject, along with the art historical commentary Marilyn might spark in a spectator and the imitation of a display light, the piece conjures a museum. On the other hand, the use of spray paint and the style of lettering in the artist’s pseudonym suggest a genre of street art. This tension between “museum” and “street art” reveals the generic interstice in which Marilyn, and potentially graffiti in general, now sits. Nor are these categories innocent: their fault lines carry deep aesthetic, political, and legal implications. Indeed, to prove that the forty-five destroyed works at 5Pointz were worthy of legal protection, the seventeen plaintiffs, including Carlos Game, describe 5Pointz as a curated “museum” (Cohen 2017). Beyond the telling use of scare quotes around an early instance of this term in their 2017 posttrial brief, the artists consistently refer to their work as “graffiti”, a label bearing a specific cultural and legal history. Echoing this ambivalence, Judge Block never described the work in question as “graffiti” in his final 2018 decision. While the plaintiffs launched the language and ideology of a “museum” to protect their art, Judge Block distanced the work from “graffiti”, deploying that term as both an indictment of illegal painting and a dismissal of its status as art.

Like Arthur Danto strolling with bemused yet earnest disappointment between works by CRASH and DAZE at the Janis Gallery in 1985, Judge Block sought to efface the term “graffiti” from descriptions of “art”. Danto was doubly frustrated, first, by the exhibition’s use of “graffiti”, which he saw as a “sociological excuse” for art that should speak for itself, and second, by what he perceived as graffiti’s inadequacies when measured against studio art. Yet, Danto himself wrestled with this contradiction. On one hand, he likened the subway to a “cathedral” of “majestic masterpieces”, recognizing that “there have been few developments in the history of art quite so remarkable” as graffiti in New York City; on the other hand, graffiti’s majesty appears inseparable from its “natural habitat” (Danto 1985). Despite Danto’s insistence elsewhere that art is socially contingent and that the artworld is a sociohistorical, interpretive space, he reduces “graffiti” to the sociological, implying that studio art lies beyond such concerns.1 In doing so, he positions the “majestic masterpieces” of the trainyards not just as an institutional outside, but an aesthetic outside. Caught in this nature/civilization opposition, graffiti becomes art’s other—an art that thrives only beyond the artworld. Ultimately, he encouraged graffiti artists to reap “the benefits of a good art school” that would “liberate” them, suggesting both artistic freedom and legitimation from within institutional norms (Danto 1985). By scrapping the term “graffiti”, Judge Block, like Danto, also discards an entire aesthetic regime, and the critical power of these works is ignored.

Instead of sending these artists back for formal training, as Danto would have it, I propose reclaiming what has been discarded. This paper takes up the anonymous aura of graffiti as an alternative critical and aesthetic regime. To say that the hegemonic aesthetics of the museum play a role in determining what is art, and therefore culturally valuable, does not need restating. My point is really to theorize what was lost in the process of assimilating these works of street art into the museum; what power do these works have when we view them in their generic precarity, spraypainted onto the museum’s exterior wall, so to speak, engaging two equally powerful yet distinct forms of intelligibility?

I take my cue here from Jessica Nydia Pabón-Colón, whose 2018 work Graffiti Grrlz powerfully reclaims female graffiti writers as subjects of both aesthetic and political inquiry, positioning a politics of presence, especially for women, as inseparable from graffiti’s own politics of absence. On one hand, the book brings female graffiti writers into view as an overlooked subculture, thereby engaging the politics of presence. On the other hand, it insists that graffiti is “an artistic practice predominantly dependent on circulation without signifying an identified body or ‘fully’ located subject” (Pabón-Colón 2018, p. 188), underscoring how anonymity and alterity are vital to graffiti’s aesthetic and political force. However, while Pabón-Colón complicates a simplistic equation of identification with political power, she ultimately places emphasis on how “representing oneself through a graffiti tag name situates the writer while performing alterity, anonymity, and difference” (Pabón-Colón 2018, p. 188). I agree that graffiti mobilizes tags and pseudonyms to “perform” anonymity, yet I find Pabón-Colón’s notion that these markers “situate” the writer leans too far toward a familiar politics of presence. She begins by recognizing that graffiti writers are not “fully located,” but eventually reverts to an identity-focused paradigm: for her, the performance of anonymity becomes aesthetically and politically meaningful precisely because it makes an identity, however partial, present. I suspect this logic leads back to the “traditional modes of representation under liberal democracy” that Pabón-Colón seeks to move beyond. Without dismissing the powerful stakes of presence in our violently exclusionary social and political landscape, I propose to build on Graffiti Grrlz by foregrounding the unidentified body: the name that covers rather than reveals identity. This is not to displace the politics of presence, which continues to counter histories of exclusion, including the erasure of women graffiti writers, whose participation, as Pabón-Colón shows, has often required navigating both visibility and alterity simultaneously. Rather, alongside that project of political, legal, and aesthetic recognition, I want to attend to what may be lost when we pivot too quickly to presence: graffiti’s sustained investment in anonymity as a mode of expression, a strategy of resistance, and therefore as a site of legal ambiguity.

This article explores anonymity as an “aura” that both makes certain paintings recognizable as graffiti and works to exclude them from museum or artworld aesthetics. I begin by examining graffiti’s tortuous history in New York City between vandalism and art, highlighting how both poles have been overlaid with ideological meaning. I then turn to the legal history of 5Pointz, tracing the primary arguments and language used throughout the litigation and contextualizing the legal and rhetorical moves that culminated in Judge Block’s decision. These debates expose a fundamental tension: while graffiti’s cultural power often derives from its aesthetic anonymity, legal systems and art institutions rely on stable authorship and formal attribution. I find that the legal criteria that underwrite protection under contemporary moral rights law also marshal a particular form of visibility and identification. Like the plaintiffs’ reliance on the “museum” framework to secure legal rights, the norms of moral law imply aesthetic judgments that ultimately privilege curated and institutionally endorsed forms of street art over more transient and anonymous practices. By examining shifts in legal arguments, judicial decisions, and cultural discourse, I show how graffiti’s aesthetic and legal standing has been alternately embraced, marginalized, and repurposed, raising critical questions about visibility, authorship, and the negotiation of public space. Finally, I return to the question of anonymity, arguing that even alongside the names of particular artists, anonymity persists as a critical and aesthetic force that challenges dominant models of recognition and complicates the legal and cultural value that graffiti inherits. I seek to reclaim graffiti’s historically illicit and unstable authorship from reductive institutional and ideological narratives and to theorize how anonymity continues to trouble prevailing frameworks of recognition, ultimately revealing new critical and aesthetic possibilities.

2. Crime or Art?

Before its demolition in 2014, 5Pointz emerged to passengers riding the 7 train from Queens into Manhattan like a mirage of an earlier time. From street level to the roof line with hardly a concession for windows, the sprawling complex teemed with aerosol paintings. Even as the artwork shifted, continually repainted, refreshed, and updated, 5Pointz preserved an urban aesthetic now rarely seen in New York. By 2025, one might wonder where all the graffiti has gone. Once ubiquitous throughout the 1970s and 1980s, tags and throw-ups now appear so infrequently that any surviving specimen evokes a bygone era. But how, and when, did it all vanish? Put bluntly, there was a war on graffiti2—waged not only by the city and the MTA against its perpetration, but also against any notion that it might qualify as “art.”3

Graffiti emerged as a widespread social phenomenon in New York in the early 1970s. By some accounts, the first major writer was “Taki 183,” a teenager who scrawled his name across the city (‘Taki 183’ 1971). The practice proliferated rapidly, triggering strong reactions from both the public and law enforcement. In addition to magic markers, graffiti writers soon adopted aerosol paint cans to mark walls and trains. Before 1972, “public writing” was not explicitly criminal; judges simply reprimanded offenders or ordered them to clean the property they had defaced. That changed when Mayor John Lindsay signed the first anti-graffiti bill, making it unlawful to carry spray paint in any public facility (Stewart 1989). Violators faced a $100 fine or six months in jail, and in 1972 alone, 1562 people were arrested for defacing public spaces (Perlmutter 1972; 1562 Youths Seized 1973).

During this period, the outlaw status of graffiti writers coincided with a nascent process of recognition and legitimation. As early as 1973, Mayor Lindsay condemned the “demoralizing visual impact of graffiti”, while his Chief of Staff insisted that “the most important notion to be discredited publicly is that graffiti vandalism and defacement of property can be cloaked with the justification or excuse that it is an acceptable form of pop art” (Schumach 1973). In other words, acknowledging graffiti as “art” risked seeming to endorse criminal activity. Yet that same year, the New York Times published an article titled “Graffiti Goes Legit”, which illustrated graffiti’s multifaceted presence in the city (Schjeldahl 1973). On one hand, the report linked it to poverty and social ills, claiming “it made the whole city look as if it were slated for demolition”. On the other, it recognized the stylistic innovations tied to specific neighborhoods and noted emerging spaces for authorized graffiti.

Despite the increased legal action and enforcement, graffiti continued to proliferate. One report suggested that in the early 1980s more than 95% of the subway cars bore graffiti (Miles 1989). Mayor Ed Koch, who would stay in office through the 1980s, approved $22.4 million to be spent on erecting barbed-wire fences around the train yards to prevent vandals from sneaking in and painting and trains. When this did not have its desired effect, guard dogs, which Koch referred to as “wolves,” were brought in (Goldman 1981). In addition, major subway-car cleaning campaigns ensued. Older trains were replaced with newer ones, featuring easy-to-clean surfaces (Castleman 2004, p. 27). The perception of graffiti as an indicator and symbol of urban blight gained substantial traction during this period. As the MTA President said in 1985, “A clean car is a symbol of an authority in control of its environment... It is a direct communication to passengers that the system is orderly” (Mincer 1985). If a clean car is a symbol of authority, graffiti was the symbol of lawlessness or anarchy. Judge Block echoed this association when he recounted the history of 5Pointz prior to Cohen’s arrival. “The warehouses were largely dilapidated and the neighborhood was crime infested. There was no control over the artists who painted on the walls of the buildings or the quality of their work, which was largely viewed by the public as nothing more than graffiti. This started to change in 2002 when Wolkoff put Cohen in charge.” (Cohen 2018, p. 16). By bundling crime, public perception, and unregulated painting into the same breath, Block implied that the mere presence of unchecked graffiti reflects a larger state of disorder. It is also rhetorically unclear what “started to change” once Cohen took the reins, suggesting that, under Cohen’s management, improvements might have included a stricter curation of who painted on the walls, new respect for the art, and, carried to an extreme, the mitigation of crime in the neighborhood.

This deep entanglement of graffiti with disorder and crime formed the foundation of official narratives justifying its suppression. Yet, even as the city deployed an increasingly militarized response, others viewed graffiti as something more than vandalism. Norman Mailer’s 1974 piece of gonzo journalism, The Faith of Graffiti, challenged this growing consensus, reframing graffiti not as lawlessness but as an artistic and existential response to the rigid, desensitizing forces of modern urban life. Mailer alludes to a deeper “anaesthetic” threat, to use Susan Buck-Morss’s term, where the “static of the oncoming universal machine” threatens to numb the senses entirely (Mailer 2009, p. 31). In this context, graffiti emerges for Mailer as an idealistic, perhaps romantic, reassertion of sensual, visual experience—a gesture that disrupts the monotony of urban alienation and revitalizes our capacity for wonder.

But Mailer’s intervention extended beyond aesthetic appreciation—he embedded graffiti within a lineage of avant-garde artistic production, positioning it alongside some of the most radical artistic movements of the 20th century. In the margins of The Faith of Graffiti, Mailer juxtaposed Jon Naar’s photographs of New York subway graffiti with images of paintings from Surrealism, Expressionism, and Cubism, implicitly inviting readers to see these modernist traditions as graffiti’s artistic antecedents. He likens the movement of the graffiti writer’s hand to Jackson Pollock’s Action Painting, drawing a parallel between the spontaneous, physical energy of the tag and Pollock’s gestural drips of paint. Graffiti’s flat, graphic aesthetic and repetition of commercial symbols, he suggested, recall Andy Warhol’s Pop Art, in which mass production and iconography displaced traditional notions of artistic originality. The suggestion, as Monroe C. Beardsley noted in his early review of the book, is that “what moves the graffiti-writers is what moves the artistic avant-garde” (Beardsley 1975). In this way, Mailer implied that graffiti is not merely knocking at the door of the artworld but is already inside it, shaping a new aesthetic vocabulary that the establishment refuses to acknowledge.

Mailer is also one of the few writers to explicitly theorize anonymity, arguing that while tagging begins as a means of self-assertion, the collective practice of graffiti ultimately surpasses the individual name itself, veering into a mythical realm. He turns the language of the city’s war on graffiti on its head, likening graffiti writers not to criminals but to an anonymous army reclaiming public space with an insurgent aesthetic. Mailer’s idealistic description of graffiti’s sweeping, collective force provides a compelling counterpoint to Danto’s rejection of graffiti as a sociological excuse for art; although both Mailer and Danto desired an “aesthetic artifact” that is not a “sociological artifact,” Mailer reversed the operation: he located graffiti at the heart of aestheticism whereas Rauschenberg famously erasing a De Kooning revealed mere “knowledge of society” (Mailer 2009, p. 28). Where Danto saw an aesthetic outside of art’s institutional logic, Mailer saw a new, insurgent aesthetic emerging precisely within the structures of the museum and the city, which he laced together.

Competing interpretations such as Mailer’s probably did little to shift public policy, but they highlight the extent to which graffiti became a battleground for ideological contestation. Perhaps more than any other aesthetic phenomenon, graffiti has been framed as a symbol of poverty and social unrest, frequently positioned as evidence of urban decline (Young 2012, p. 302). Its association with crime and gang culture has been well documented, though often exaggerated through “moral panic” and media narratives. The names scribbled, scratched, and painted around the city conjured the anonymous (or pseudonymous) masses who might circumvent authority, a fact that has long unsettled policymakers and law enforcement. Sociologists and criminologists continue to analyze graffiti in attempts to comprehend the psychology of alienated and restless youth. Throughout the 1980s, this association intertwined the struggle to control graffiti with political ideology. While champions of its artistic nature defended graffiti as comparatively innocuous, authorities cast it as a sign of delinquency and criminality, reinforcing its legal suppression (Young 2012). So-called Broken Windows Policies assumed that petty crimes like graffiti would actually stimulate others, and more serious ones (Wilson and Kelling 1982, p. 29). By the end of the decade, the authorities mostly prevailed. Despite many accounts saying the reports of success were exaggerated, in 1989, the New York City Transit Authority celebrated a graffiti-free subway system (Hays 1989). Mayor Giuliani, who took office in 1994, continued the logic of Broken Windows through his Quality-of-Life campaign. Eliminating graffiti was a primary aspect of this campaign. Once again, emphasizing graffiti as a crime that would breed other crimes, he and his administration actively spoke against misinterpreting graffiti as art or a “fashionable expression of the counter-culture”, asserting instead that it is “a metaphor for urban decay” (Hicks 1994). This ideology supported increasing police presence and heightening surveillance systems throughout the city.

The careers of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, who leveraged their experiences as illegal graffiti writers to gain authenticity and visibility in the fine art world, epitomize this tension between fashionable expression and urban blight. They did not merely transfer graffiti styles onto canvas; they positioned themselves as genuine graffiti writers who had painted illegally in public spaces. Their work exemplifies how authenticity often functions as a crucial form of cultural capital for street artists, since a perceived deficit of authenticity can prompt accusations of appropriation. Meanwhile, Hugo Martinez, founder of the United Graffiti Artists, was staging exhibitions in venues such as the Martinez Gallery in Chelsea and the Razor Gallery in Soho, as well as organizing a special show at City College in 1972. In early 1973, he collaborated with choreographer Twyla Tharp on Deuce Coupe, featuring on-stage spray-painting during the performance (Kramer 2016, p. 29). By the early 1980s, artists like Fab Five Freddy and Lady Pink, one of the plaintiffs in the 5Pointz litigation, were also gaining acclaim in galleries; both appeared in the cult docudrama Wild Style (1982), now considered foundational in hip-hop studies (Gruen 1991). Even today, brands seek out street artists to lend their products urban credibility, although not all view this commercial exposure similarly. Among 5Pointz-affiliated artists, Jonathan “Meres One” Cohen includes such commissioned work as part of his artistic resume (Cohen 2025), whereas Dasic Fernández explicitly rejects these commercial overtures (Fernández 2017, vol. 23, p. 45). Brands seek out street artists to lend their products urban credibility, while figures such as “Banksy” enjoy broad name recognition well beyond the traditional boundaries of graffiti and street art.

Some critics see a paradox in graffiti’s growing acceptance. In his recent article “Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Tradition of 5Pointz,” legal scholar Richard Chused contends that early graffiti “was an act of rebellion, a rejection of the fetishizing of ‘great’ art, and a celebration of the sometimes hasty, impermanent, but joyful act of Creation” (Chused 2018, p. 588). By operating outside institutions and private property norms, graffiti historically thrived on anonymity and impermanence. Yet, as Chused noted, the allure of “monetized instincts now governing major art galleries, auction houses, and museums” gradually crept into the scene, threatening the “risk-taking camaraderie” of earlier decades (Chused 2018, p. 589). He describes this shifting identity as an “anti-rebellion”, a process wherein rebellious acts become valued—and even protected—by the very systems they once defied. Chused pointed to 5Pointz as emblematic of graffiti’s uneasy assimilation into legal and cultural frameworks, remarking that artists who once reveled in the ephemeral rush of clandestine painting “were aware of the cultural shifts and conflicts” (Chused 2018, p. 589): they could now produce large, legal wall pieces, gain institutional recognition, and even enter remunerative art markets—yet in doing so, he argued, they distanced themselves from graffiti’s original subversive ethos.

The work of criminologist and legal scholar Alison Young, which underscores that anxieties over the “death” or assimilation of street art reflect its constant transformation rather than an outright loss, provides an alternative to Chused’s emphasis on the distance between rebellion and anti-rebellion, legal and illegal painting. In the final pages of Street Art, Public City, Young acknowledges fears that street art has succumbed to the mainstream yet maintains that such anxieties point to situational art’s adaptability, not its demise. She underscores the importance of graffiti in its own right as a “situational art” that unsettles everyday encounters with property, legality, and aesthetics (Young 2014). Caitlin Bruce further complicates this perspective by focusing on legal graffiti spaces, showing that even sanctioned graffiti remains a site of negotiation rather than stabilization. In Painting Publics, she examines how legal graffiti festivals challenge the legal/illegal binary by emphasizing its role in fostering public encounters. Drawing Chantal Mouffe’s account of constitutive antagonism and democratic plurality, Bruce frames these encounters as forms of “agonistic” engagement (Bruce 2019, p. 8). While Young critiques theorists like Nick Riggle, who proscribe graffiti from the outset,4 Bruce’s work suggests that even within spaces of partial recognition, graffiti continues to challenge aesthetic, social, and legal expectations. Rather than framing these interventions merely as vandalism or as formal “art”, both scholars argue for a more nuanced conversation that embraces graffiti’s paradoxes—whether in its adaptability across legal categories (Young) or its continued contestation within sanctioned spaces (Bruce). In a nod to David Harvey, Young thereby highlights how these uncommissioned pieces speak to deeper questions about who controls urban spaces and how they might be reimagined, ultimately urging us to inhabit a “public city” forged through open, if often contested, creative expression.

Building on the “situational” and “agonistic” relational modes of interacting with public art, I return to the question of how anonymity persists as an aura, even in legally painted graffiti. Rather than treating “legal” and “illegal” as strictly opposed categories, I propose that the cultural shift Chused described gave rise to an aesthetic genre still stamped by its life outside formal institutions. Chused observed that street art is “no longer just the rebellious demonstrations of the oppressed or disgruntled” (584), implying that more artistic, legal graffiti forfeits specific identities and political-economic realities. While “anonymity” may have originated in efforts to evade law enforcement, the difficulty of attributing a single authorship imbues graffiti with a shared, collective ethos, one that extends beyond any individual artist, even when the creator’s name is known. We might call this a return of “the oppressed or disgruntled” as an auratic collective identity performing within the appearance of graffiti. Whenever we recognize something as graffiti, I argue, it is because of the aura of anonymity that allows us to sense or imagine a collective author. This return of the oppressed underscores how graffiti’s evolution is not a simple matter of authenticity or legality but rather a continued enactment of aesthetic values that endure regardless of institutional boundaries.

3. 5Pointz and Anonymity

Internationally known as 5Pointz, the site encompassed over 200,000 square feet of warehouse space, with nearly all of its walls covered by about 350 works of legal graffiti. Although graffiti had existed there for decades, the site’s formal artistic legacy began around 1993, when Pat DiLillo struck a deal with owner Gerald Wolkoff. Wolkoff’s only prohibitions were no politics, no pornography, and no religion. DiLillo was a plumber who, in his spare time, formed the Graffiti Terminators, a group dedicated to cleaning up graffiti, and both buffed illegal pieces while designating legal walls for artists to create upon. He named the site the Phun Phactory, as it was known until June 2002, when Jonathan Cohen, an established graffiti writer himself, took over for DiLillo. Cohen extended and formalized DiLillo’s internal rules to maintain order among the artists and soon renamed the site 5Pointz, after the city’s five boroughs. He set protocols for where and when people could paint, which, in turn, affected how long any given work might remain: so-called “long-term walls” were allocated to the most highly esteemed artists.

The 5Pointz litigation began in June 2013, shortly after Wolkoff received approval from the City Planning Commission to demolish the cluster of defunct factories. Prominent both from the streets and the above-ground 7 train, 5Pointz was a rare, highly visible site for legal graffiti and had become well-known for its constantly changing, colorful walls. In addition to the thousands of people who saw the site each day from the streets and trains, hundreds of visitors attended local and out-of-town tours on a daily basis. When the housing market in that section of Queens picked up around 2010, Wolkoff looked to capitalize on his investment by developing new condominiums. Cohen filed an application with the City’s Landmark Preservation Commission to designate 5Pointz as a landmark. The request was denied “because the feature of interest—the artwork—had not been in existence for at least thirty years” (Cohen 2013, p. 24). Cohen, along with 16 other 5Pointz-affiliated artists (including Carlos Game), then sought a preliminary injunction to prevent the warehouses’ destruction under the Visual Artists Rights Act (VARA). Judge Block issued an oral order on 12 November 2013, denying their injunction, again citing the “ephemeral” nature of the work and the owner’s right to develop the property. He noted that a written opinion would soon follow.

Seven days later, just two days before Judge Block issued his promised written statement, Wolkoff ordered the whitewashing of all art on the property. Although Wolkoff claimed he wanted to spare the artists the agony of watching their work be destroyed (and to avoid agitation during demolition), the vivid colors and outlines still visible beneath the hastily applied white paint only magnified their distress. Judge Block’s statement, released two days later, reflects his awareness of the whitewashing. Even while expressing dismay, Block reasoned that the plaintiffs’ rights as artists “were at tension with conventional notions of property rights and the Court tried to balance these rights”. Invoking the need for “balance”, he denied the injunction: on one hand, the injunction would place a considerable financial strain on Wolkoff’s condominium project; on the other, because the works were deemed “temporary”, the artists did not demonstrate “irreparable harm”. Despite his call for balance, it appears that Block weighed Wolkoff’s potential loss more heavily than that of the artists. Paradoxically, Block’s denial of the injunction rested on the graffiti’s “ephemeral nature” even as he affirmed VARA’s protection of temporary works. He thus occupied a conflicted position, acknowledging VARA’s reach yet concluding that, because the harm incurred was not “irreparable”, the ephemeral nature of the artwork was insufficient to justify injunctive relief.

Toward the concluding pages of his 2013 decision, Judge Block offered a warning concerning the potential legal repercussions of the whitewashing: “Since VARA protects even temporary works from destruction, defendants are exposed to potentially significant monetary damages if it is ultimately determined after trial that the plaintiffs’ works were of ‘recognized stature’” (Cohen 2013, pp. 26–27). He anchored this caution in Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, calling it “the seminal case interpreting the phrase ‘recognized stature’—which is not defined in VARA—to require ‘a two-tiered showing: (1) that the visual art in question has “stature”, i.e., is viewed as meritorious, and (2) that this stature is “recognized” by art experts, other members of the artistic community, or by some cross-section of society’”. Whether the works in question could pass that test remained unclear until trial. When the matter proceeded in 2018, thirty-six of the forty-nine contested works met the Carter criteria, entitling the plaintiffs to compensation.

The legal and cultural significance of 5Pointz has been analyzed from multiple perspectives, each exposing different limitations in existing legal frameworks. Chris Godinez critiqued the way Judge Block interpreted VARA’s “recognized stature” requirement, noting that the court’s reliance on academic citations and expert recognition disregarded the broader cultural significance of 5Pointz as a public and community-driven artistic space (Godinez 2014). For Godinez, the court’s dismissal of public and community recognition in favor of institutional approval exemplifies the fundamental misalignment between street art’s cultural function and the mechanisms designed to protect it, leaving works like those at 5Pointz vulnerable to destruction despite widespread popular engagement. Timothy Marks also examined the limitations of VARA but focused on how its emphasis on individual works of art failed to account for graffiti’s relationship to place. 5Pointz, he argued, functioned not as a set of discrete pieces but as an integrated artistic environment, where meaning was derived from its collective form rather than the sum of its parts (Marks 2015). The legal approach requiring artists to prove individual merit, according to Marks, misrepresents how 5Pointz operated as a curated and relational space, exposing gaps in how legal frameworks conceptualize public art.

Mekhala Chaubal and Tatum Taylor brought further attention to these gaps by addressing 5Pointz as an evolving cultural landscape, emphasizing that neither preservation law nor copyright frameworks could adequately protect a space defined by its performative and spatial dimensions (Chaubal and Taylor 2015). They conceive of 5Pointz as a gesamtkunstwerk, a “synthesis of multiple forms of artistic expression into a singular work that unites spectators through their mutual experience of the work” (Chaubal and Taylor 2015, p. 85). Their study invoked UNESCO’s notion of intangible heritage to illustrate “parallel gaps in the realms of preservation and intellectual property laws,” calling attention to legislative deficiencies that cannot accommodate 5Pointz’s performative, ever-evolving nature (Chaubal and Taylor 2015, p. 86). Their analysis highlighted how 5Pointz was shaped by the ritualized social practices of curation, layering, and erasure, positioning it not merely as a repository of art but as a living site of artistic production. Together, these perspectives reveal how legal and institutional frameworks have struggled to accommodate graffiti’s fluidity, raising fundamental questions about how public art is valued, protected, and remembered. I agree with Marks’s insistence that 5Pointz operated as an integrated, site-specific environment, and with Chaubal and Taylor’s emphasis on its evolving cultural landscape. While neither author used the term “anonymity”, the concept seeps through the cracks they identify in the current legal frameworks.

While Chused ultimately agreed with Block’s 2018 decision, he faulted Block’s 2013 refusal to grant injunctive relief, arguing that the judge missed what mattered most. “In the portion of Judge Block’s preliminary injunction opinion about balancing of interests,” he observed, “he misunderstood the basic notion that the graffiti artists’ primary concern was about the inherent creative value of the work to the culture at large, not about the market value of the work to a potential purchaser” (Chused 2018, p. 622). Chused saw VARA’s moral-rights framework, which has existed only since 1990, as designed precisely to protect this non-economic core. As Carter (Pellicore 1995) elaborated, “The term “moral rights” has its origins in the civil law and is a translation of the French le droit moral, which is meant to capture those rights of a spiritual, non-economic and personal nature. The rights spring from a belief that an artist injects his spirit into the work and that the artist’s personality, as well as the integrity of the work, should therefore be protected and preserved” (Pellicore 1995). In attributing an intention-filled identity to the 5Pointz creators, both Chused and Block ascribe a fulsome presence of moral rights requiring a stable author whose “spirit” inhabits the work. Carter’s legal framework, although explicitly providing for anonymous or pseudonymous works, still presupposes an identifiable subject to assert those rights. In other words, an institutionally and legally legible creator must be the recognized spirit behind the artwork. Likewise, once Cohen had selected recognized “real” artists according to artworld protocols, Block treated graffiti at 5Pointz as fully legible and thus legally protectable. In both cases, this effectively preserved the stable figure of the author, such that any work deemed worth of protection could be assimilated into the imaginary museum.

Although graffiti’s “ephemeral nature” appears to be the point in question, both Chused and Block easily show how ephemeral art can hold recognized stature, in Block’s case through a simple appeal to “common sense.” Chused, for one, compared 5Pointz graffiti with celebrated installations like Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Gates and Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, applying the nuances of those cases to the destruction of 5Pointz. Judge Block made a related point in his 2018 decision, asking rhetorically “Who would argue, for instance, that if Picasso had painted Guernica on the walls of 5Pointz with the building owner’s consent it would not be worthy of VARA protection?” (Cohen 2018, p. 27).5 Block’s point, like Chused’s, was that once we view 5Pointz as already legible within the artworld, either via comparisons with institutionally validated site-specific installations or through the hypothetical work of a quintessential artworld figure occurring at 5Pointz, the precedent for protecting these works was a foregone conclusion. All that would remain would be to use the appropriate metrics to show that these works are indeed recognizable as such.

Names like Picasso, De Kooning, Serra, and Christo epitomize the authorial presence necessary for immediate artworld recognition. Chused used those references to argue that ephemeral art of merit deserves prompt legal protection. Block draws on the same principle through Cohen’s curation, conceding that once graffiti appears in a structure akin to a museum, guided by a gatekeeper’s selection and endorsement, it belongs under VARA. Neither, however, questioned whether graffiti’s aesthetic power might hinge on anonymity and sometimes even a direct refusal to function as “art” in the canonical sense. In other words, anonymity is simply the condition of covering a name. This outlook does not take into account anonymity as an aesthetic feature which, as in the case of graffiti, can create institutional illegibility. In doing so, they risked folding graffiti into the artworld’s institutional framework, sidestepping the genre’s distinct aesthetic moves and critical modalities. This same logic informed Block’s reliance on Jonathan Cohen’s curatorial system. By “selecting the handful of works from the thousands at 5Pointz for permanence and prominence on long-standing walls”, Cohen effectively reproduced a museum-like apparatus within a neglected industrial site (Cohen 2018, p. 30). The selection of reputed artists, the allocation of prime visibility, and the extended lifespan of certain pieces, a process mirroring institutional acceptance, helped Block conclude that 5Pointz graffiti had achieved recognized stature. In other words, by importing the mechanism of admission and the ideology of a museum into 5Pointz, Block could treat it as an already-assimilated artic practice subject to conventional metrics of quality and authorship. Block effectively granted it legal standing while displacing the aspects of the works that were still palpably “graffiti”. While I do not deign to comment on the legal considerations of Chused or Block’s judgements, both clearly sidestepped the unspoken issue that flags these works as aesthetically bereft (by artworld standards) and legally vulnerable.

Building on Chused’s analysis of graffiti’s shifting status, I further explore how the instability of graffiti’s aesthetic presence conditions its legal vulnerability. If anonymity in graffiti functions as an aesthetic process rather than just a lack of authorship, then the legal inability to categorize such works under VARA reveals a deeper tension between graffiti’s open-ended reception and institutional demands for recognition. The emphasis on museum-like curation, familiar names, and recognized stature reveals how graffiti at 5Pointz gained legal standing by adopting attributes akin to what Chused called “ephemeral art” of sufficient merit—namely, an institutionally valid author. In museum logic, an author must be locatable, marketable, and accountable, reflecting Carter’s presumption that even anonymous works have some identifiable figure behind the scenes. By contrast, graffiti’s more disruptive potential remains unexplored. Young considered this perspective through the phenomenological experience of encountering graffiti as a sudden visual intervention rather than as a conventionally authored piece, a dynamic that can produce aesthetic or political effects.

Significantly, she concludes her book by asking whether we can love “both the experience of commissioned art and the enchanting, uncanny intervention that occupies a space belonging to another,” a question that pinpoints how graffiti can hinge on the delicate interplay between unbidden creation and the boundaries of ownership. Her choice of the word “another” not only underscores the illicit or unauthorized dimension of street-based practices but also resonates with the elusive identities of those who create them, implicitly invoking anonymity as a critical component of graffiti’s unsettling power. In occupying “a space belonging to another”, these situational artworks remain partially unclaimed, both by their artists and by conventional art institutions, thereby sustaining a sense of mystery that challenges viewers to contend with the ethical and aesthetic consequences of art that refuses to fully disclose its authorship. What Young attributes here to the experience of happening upon a work of graffiti in the street, I interpret as a formal property in graffiti itself. It is precisely this feature that makes graffiti recognizable as such and generates its aura of anonymity.

In Chused and Block’s accounts, legally produced graffiti appears automatically to qualify as “art,” covering the way anonymity as a continual aesthetic practice disrupts the presumed author–work relationship. Even legal perspectives that protect anonymous work recast it as a temporary hindrance. If a piece is protected, the expectation is that its creator will eventually step forward so that the work can obtain moral rights. Yet, once that intervention is brought under legal recognition, the capacity for graffiti to remain partially unassimilated is diminished. Philosophers like Arthur Danto, for example, interpret an artist’s shift from a “tag name” to a legal name as the definitive sign of artistic legitimacy. Danto’s assertion that DAZE “has made genuine progress toward becoming Chris Ellis” directly links the transition from subcultural anonymity to public recognition with art’s passage from raw sociology to institutionally validated aesthetics (27). In this framework, the pseudonym serves largely as a placeholder for sociological baggage—urban context, illegality, and subculture. By highlighting the pseudonym’s inadequacy within institutional settings, Danto exposes how it fosters a form of anonymity that makes the artist unrecognizable as such. The artist’s status as a fully legitimate creator becomes secured only when anonymity yields to a stable legal identity.

At the apex of this anonymity, we stop seeing graffiti as art and instead look at CRASH as “an exhibit himself—like that warrior who danced for the opening of the Maori art exhibit at the Met” (Danto 1985, p. 27). By comparing CRASH to a performer on display, Danto locates his value in an exoticized, sociological, or even anthropological context rather than in his artwork. Far from intentional bigotry, this move rests on the assumption that art transcends the circumstances of its creation; however, what Danto misses is that such transcendence only occurs so long as the artist is recognized within canonical, Eurocentric institutions. Thus, CRASH stands as an artist, but “not quite,” to borrow Homi Bhabha’s phrase, perpetually tethered to the social and racial markers that define him otherwise. The precarious situation faced by CRASH, where he is recognized as an artist yet still defined by sociological and racial markers, reveals that Danto’s so-called non-sociological aesthetic actually depends on a silent racialization of graffiti, positioning it outside the norms of pure high art while holding the artist responsible for gaining acceptance on the museum’s terms. In other words, the movement toward being named and identified as an artist deracinates the subject from its social context and origin; graffiti’s anonymity, meanwhile, continues to grip even the dually named subject who appears and exhibits work.

The anonymity of graffiti writers has consistently obscured the role of race, gender, and identity in scholarly discourse, precisely because it evades the usual markers of authorship on which such analyses often depend. Ivor Miller’s early ethnographic work on graffiti in NYC, Aerosol Kingdom, expresses this difficulty quite well. On one hand, Miller argues that graffiti emerges from African American and Afro-Caribbean cultural traditions, functioning as a creolized survival strategy deeply tied to Black aesthetics, naming practices and resistance to systemic oppression (Miller 1990). On the other hand, he contends that scholarship must account for the cultural intermixing that shapes the genre’s broader identity. Nevertheless, acknowledging graffiti’s multiethnic participation has not eased the criminalization of Black and Latino youth, even as mainstream culture commodifies its visual style. The stakes of Miller’s analysis lie in reclaiming graffiti as a historically and politically situated art form, challenging its dismissal as vandalism and positioning it within a lineage of diasporic cultural innovation and urban self-determination. Jessica Pabón-Colón likewise warns that when historical specificity is forfeited, anonymity can become an aestheticism that effaces the racial and socioeconomic realities at the heart of graffiti. In other words, allowing an idealized form of anonymity to dominate critical discussions risks stripping graffiti of its socioeconomic context and political force. At the same time, “museum aesthetics” that seek to de-anonymize graffiti—yet detach it from its original contexts—create a cover for racial and political coding, as seen in the work of Danto and Chused. Such coding suggests that terms like “rebellion” or “anti-rebellion”, “natural habitat”, “the oppressed and disgruntled”, are not neutral descriptors but racially and class-inflected discourses.

In negotiating the difficulties of addressing graffiti’s diasporic aesthetics while also allowing space for multiethnic participants, a struggle which parallels the idea of engaging a politics of absence without forsaking a politics of identity, Pabón-Colón identifies a “productive and difficult tension” between “performance” and “subjectivity and identity”. I think this approach aptly illustrates the complex relationship between graffiti writers and their artwork, but it also reveals two challenges: first, it can tie subjectivity too closely to identity, and second, it misses the opportunity to conceptualize “performance” as a production of subjectivity rather than merely an expression of a preexisting self. In other words, in a very real sense, the collective subject gleaned or imagined through graffiti’s anonymity does not preexist the encounter. Even as an author is named and identified, the collective hand formerly cast as the rebellious and the oppressed, but also as Mailer’s “tropical peoples” and Danto’s Maori warrior, continues casting its spell. More than graffiti’s ephemerality, I argue that this blurring of authorship that Danto articulated so clearly as a matter of naming (CRASH’s “progress towards becoming Chris Ellis”) is what immediately marks graffiti as unworthy of legal protection. Accepting the ways that graffiti’s aura of anonymity produces a collective subject also means grappling with the class, race, and gendered politics of that production.

Rather than functioning as an absence to be corrected, an obstacle to authorship, graffiti’s aura of anonymity generates a collective aesthetic subject, one that resists being reduced to either individual artistic genius or political subversion. It is this refusal to resolve into a stable identity that makes graffiti so disruptive: it collapses the categories through which legality, authorship, and visibility are adjudicated. Where Pabón-Colón’s framework still implies a movement toward self-representation, graffiti’s anonymity offers something else entirely—what I earlier called a “suspension of recognition” but could perhaps be imagined as a legal recognition that does not rely on identification.

Yet, what do we do with this collective subject? Graffiti’s anonymity is easily commodified, absorbed into the aesthetic economy of urban authenticity, its radical instability repackaged as a marketable edge. It also lends itself to a more insidious form of overdetermination—the faceless figure of graffiti’s vandal writer, rewritten by the violent interstice of racial profiling, class oppression, and policing in the so-called “ghetto”, to use Mailer’s term. If anonymity can be rewritten as both radical refusal and as racialized erasure, what would it mean to take this collective subject seriously—not as an object to be assimilated or discarded, but as a critical and aesthetic force capable of unsettling policies and enactments of power?

4. Conclusions

The building was already scheduled for demolition when a large, highly visible mural appeared on the wall facing the aboveground 7-train. Known as Dream of Oil, it was created after artists were apprised of Wolkoff’s demolition plans, potentially offering the artist, known as Dasic, a window of time to craft a more politically suggestive piece than previously permitted under Wolkoff’s rules (Figure 2). The painting depicts a figure lying in a viscous pool of black oil, her face wrapped in a desert-scarf. The oil, rendered with three-dimensional depth, seeps onto the flat roof just below the wall and spills toward the viewer. Although the body’s skin and clothing are painted in a lifeless grayscale palette, the figure seems to be sleeping rather than dead. Cold blacks and grays contrast with the fluorescent rainbow fingerless gloves and a keffiyeh painted as an open sky dotted with scattered clouds. Beyond the pool of oil, the sun has set in a fierce, glowing orange, while the upper sky shifts from turquoise to deep nighttime blue. The face-scarf and oil may hint at a Middle Eastern context—a reading reinforced by the mural’s date, 9/11/2013. Fingerless gloves, though they have appeared in high society, more often suggest practical labor or homelessness, adding an ironic note to their bright rainbow hues. Equally ironic is the scarf-as-sky: rather than cloaking the sleeper in darkness, it exposes her to a broad horizon of color.

Figure 2.

Dream of Oil by Dasic Fernández (Cohen 2018, p. A-18).

A closer look reveals droplets of bright color emanating from the sleeper’s body and dripping upwards, rather than into the black oil below. These droplets gravitate toward the vivid tags and Meres One’s iconic light bulbs above, as if collectively forming or joining a vibrant, airborne display. This ascending radiance creates a direct connection between the prone figure and the riot of graffiti overhead, implying that her dream might be generating or sustaining this shared visual vocabulary. The mural is not presented as a standalone painting; it actively converses with the surrounding inscriptions and imagery. In this suspended interplay, the black oil remains dense and murky, while the rising colors float freely through the air. The sleeping figure is thus intimately linked to the pseudonymous signatures overhead—perhaps dreaming them into existence or generating them in some uncanny collaboration.

The hooded figure is a recurring motif for Dasic, who first used it in Valparaíso, Chile, where yachts and cruise ships arrived “full of gringos”. In response, he painted a Muslim woman’s covered face to convey, “we see you, you’re never out of sight”, aligning her with street protesters who wear face-coverings for different struggles but share a unifying battle against systemic injustice. As Dasic puts it, “It’s not a specific person, it represents everyone” (Fernández 2017, min. 31:00). In those iterations, the hooded figure’s eyes peer out toward the spectator. At 5Pointz, the tension between the figure’s closed eyes and Dasic’s earlier injunction, “we see you”, delivered this time by someone seemingly unable to see, echoes Martin Carter’s famous suggestion of dreaming not to sleep but to change the world, implying that dreaming can be an act of engagement rather than withdrawal. By making the hooded woman, this “everyone”, simultaneously the one who sees and the one being observed, Dasic makes the viewer unsure of who truly “remains out of sight”. By simultaneously assuming and denying visibility, the sleeper, like Marilyn, suspends the logic of recognition. The figure’s sheer scale and public visibility, even as it withdraws behind closed eyes and a sky-scarf that forestalls any simple recognition, create a material dream-space that the viewer both contributes to and remains barred from. The rising droplets of radiant color amplify this uncertainty: as they ascend toward the graffiti tags above, they suggest that the sleeper’s dream, far from shutting out the world, actively reshapes it. The sight unseen, the viewer, is somehow listed in the host of graffiti above her, implicating onlookers in the same realm of performed anonymity.

Dreaming graffiti thus inverts the tag’s usual relationship to space: here, it is not the tag that interrupts the visual schema, overlaid on top of the world’s daily holdings, but the mural that crashes into a world of graffiti, integrating the impossible figure of the graffiti writer into our mind, normalizing graffiti onto the wall. Shutting us out of the dreamer’s interior space has paradoxically opened our own space anew. In this move, which puts the spectator into a world always already tagged, the viewer is conjured by the tag. In other words, this is not Norman Mailer’s anonymous army marching on the unseen ridge, and the words are not illegible characters of all the languages Mailer finds lodged in an inaccessible past only open to the other, but the unnamed part of the viewer, the potential protester or dreamer who might occupy, imagine, or paint this very scene.

Nor is it incidental that both of the central images examined here, Dasic’s dreaming figure and See-TF’s Marilyn, depict women. Graffiti has long been coded as a masculinized domain, associated with risk, aggression, and urban conquest, a framing echoed in Danto’s invocation of the Maori warrior. The gender of these figures, however, disrupts that logic from within. If Marilyn found us on that staircase and whispered in our ear, directing us toward that fugitive basement, Dasic’s sleeping figure reorients what we think graffiti can do and who we imagine doing it. If graffiti’s anti-rebellion insists on legal recognition through a politics of presence, Dasic routes its insurgency through the excluded female writer, expanding the collective subject we are summoned to inhabit.

Through its dreamlike inversion of visibility and spectatorship, Dream of Oil stages anonymity as an active force that refuses capture. While the legal recognition and remuneration of graffiti artists at 5Pointz is undoubtedly significant, it remains incomplete if we forget the power of graffiti’s aura of anonymity: not only its capacity to slip past authorship and institutional containment, but also its ability to conjure a “we” that cannot yet be named: a collective subject banned from assembling in sanctioned spaces, one already or soon vulnerable to surveillance, censorship, or criminalization. Anonymity here is not merely a shield for the not-yet-knowable against premature identification, but an aesthetic force capable of producing emergent forms of solidarity. In that unresolved tension of spectatorial presence and non-presence, the female figure comes to personify the aura of anonymity.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | By artworld I am referring to “an atmosphere of artistic theory, a knowledge of the history of art: an artworld” (Danto 1964). Lydia Goehr similarly connects the ideology of “the museum” (in Goehr’s case of musical works) to Danto and Dickie’s separate but related uses of “artworld” (Goehr 1992). |

| 2 | For a comprehensive look at how the policing of graffiti relates to larger programs and structures of social control, see Kurt Iveson’s article on the rise of militarism in urban spaces. He considers how the ‘war on terror’ imbricates the ‘war on graffiti,’ both practically and ideologically (Iveson 2010). |

| 3 | Craig Castleman provides a clear picture of this war, illustrating the financial investment in eradicating and preventing graffiti, increasing penalties for violators, and the ideological battle fought by city administration to influence public perception (Castleman 2004). |

| 4 | Riggle distinguishes street art from both graffiti and sanctioned public art by insisting that its material use of “the street” is essential to its meaning (N. A. Riggle 2010). Andrea Baldini then challenged Riggle’s framework by emphasizing subversiveness, particularly how street art contests commercial dominance, thus seeking to reassert a political dimension that Riggle’s account sidelines (Baldini 2016). In turn, Riggle’s reply concedes that street art can be subversive but maintains that subversion is not a necessary feature, insisting instead on the artwork’s “antithetical” stance toward artworld conventions (N. Riggle 2016). Crucially, Riggle’s early exclusion of graffiti, particularly tagging, from the category of street art raises questions about anonymity as a key critical and aesthetic aura, something Baldini aims to restore through his focus on street art’s political subversiveness. Together, their debate centers on whether street art must challenge power structures as an essential feature or whether its defining trait lies simply in its integral, material engagement with urban space. |

| 5 | In fact, Block’s counterfactual has a coincidental, historical precedent: Picasso’s friend and fellow artist, Brassaï, once asked him if he had ever carved on a wall. He quotes Picasso responding “Yes, I have too. I left a large number of carvings on the walls of the Butte. One day in Paris, I was waiting in a bank. It was being renovated. So, between the scaffolding, on a section of condemned wall, I put up a graffito. By the time the construction work was completed, it had disappeared. A few years later, because of a modification of some sort, my graffito reappeared. People found it odd, and learned it was by Picasso. The bank director stopped the construction work, had my carving cut out as a fresco with all the wall surrounding it, and inlaid it in the wall of his apartment” (Brassaï 1999, p. 254). Apparently, Picasso did not need to paint Guernica at 5Pointz—anything that could be connected to his name would warrant preservation. |

References

- 1562 Youths Seized in ’72 For Their Graffiti Work. 1973, The New York Times, January 14, 14.

- Baldini, Andrea. 2016. Street Art: A Reply to Riggle. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 74: 187–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardsley, Monroe C. 1975. Review: The Faith of Graffiti. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 33: 373–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2006. Selected Writings: Volume 4, 1938–1940. Edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. 4 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Brassaï. 1999. Conversations With Picasso. Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Caitlin Frances. 2019. Painting Publics: Transnational Legal Graffiti Scenes as Spaces for Encounter. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchloh, Benjamin H. D. 2000. Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975. Cambridge: The MIT Press, An OCTOBER Book. [Google Scholar]

- Castleman, Craig. 2004. The Politics of Graffiti. In That’s the Join!: The Hip-Hop Studies Reader. Edited by Murray Forman and Mark Anthony Neal. New York: Routledge, pp. 21–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chaubal, Mekhala, and Tatum Taylor. 2015. Lessons from 5Pointz: Toward Legal Protection of Collaborative, Evolving Heritage. Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism 12: 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chused, Richard. 2018. Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz. The Columbia Journal of Law & The Arts 41: 583–639. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jonathan. 2025. Meres One. Available online: www.meresone.com/about (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Cohen v. G&M Realty, L.P., 988 F. Supp. 2d 212, 227 (E.D.N.Y. 2013).

- Cohen v. G&M Realty L.P., No. 13-CV-5612 (FB) (JMA), Plaintiffs’ Post-Trial Brief (E.D.N.Y. Dec. 18, 2017).

- Cohen v. G&M Realty, L.P., No. 13-CV-05612, 2018 WL 851374 (E.D.N.Y. Feb. 12, 2018).

- Danto, Arthur C. 1964. The Artworld. The Journal of Philosophy 61: 571–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danto, Arthur C. 1985. Post-Graffiti Art: CRASH, DAZE. The Nation 12: 24–7. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Dasic. 2017. 10 Chilenos Que Están Cambiando El Mundo. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FnOU9Gpx5DU (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Godinez, Chris. 2014. Painting over VARA’s Mess: Protecting Street Artists’ Moral Rights through Eminent Domain. Thomas Jefferson Law Review 37: 191–224. [Google Scholar]

- Goehr, Lydia. 1992. The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works: An Essay in the Philosophy of Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, Ari L. 1981. City To Use Pits of Barbed Wire in Graffiti War. The New York Times, December 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gruen, John. 1991. Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography. New York: Prentice Hall Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, Constance L. 1989. Transit Agency Says New York Subways Are Free of Graffiti. The New York Times, May 10. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, Jonathan P. 1994. Mayor Announces New Assault on Graffiti, Citing Its Toll on City. The New York Times, November 17. [Google Scholar]

- Iveson, Kurt. 2010. The wars on graffiti and the new military urbanism. City 14: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Ronald. 2016. The Rise of Legal Graffiti Writing in New York and Beyond. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Mailer, Norman. 2009. The Faith of Graffiti. New York: Icon !t. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Timothy. 2015. The Saga of 5Pointz: VARA’s Deficiency in Protecting Notable Collections of Street Art. Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review 35: 281–318. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Martha A. 1989. In The Subway, a Measure of Control Is Up. The New York Times, May 14. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Ivor Lynn. 1990. Aerosol Kingdom: The Indigenous Culture of New York Subway Painters. New Haven: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer, Jillian. 1985. Is The Transit Authority Winning the War on Crime? The New York Times, November 24. [Google Scholar]

- Pabón-Colón, Jessica Nydia. 2018. Graffiti Grrlz: Performing Feminism in the Hip Hop Diaspora. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pellicore, Deandra. 1995. Carter v. Helmsley-Spear, Inc., 71 F. 3d 77 (2d Cir. 1995). DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law 6: 317. [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter, Emanuel. 1972. Fines and Jail for Graffiti Will Be Asked by Lindsay. The New York Times, June 26. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle, Nicholas Alden. 2010. The Transfiguration of the Commonplaces. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68: 243–57. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle, Nick. 2016. Using the Street for Art: A Reply to Baldini. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 74: 191–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjeldahl, Peter. 1973. Graffiti Goes Legit. The New York Times, September 16. [Google Scholar]

- Schumach, Murray. 1973. At $10-Million, City Calls It a Losing Graffiti Fight. The New York Times, March 28. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Jack. 1989. Graffiti: An Aesthetic Study of Graffiti on the Subway System of New York City, 1970–1978. New York: New York University. [Google Scholar]

- ‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals. 1971, The New York Times, July 21.

- Wilson, J. W., and G. L. Kelling. 1982. Broken Windows. Atlantic Monthly, March. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Alison. 2012. Criminal images: The affective judgment of graffiti and street art. Crime Media Culture 8: 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Alison. 2014. Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).