1. Introduction

Cultural productions—here, in particular, we look at graffiti—are inserted into what might be called ‘circuits of valorization.’ A valorization circuit can be understood as an assemblage of cultural, legal, economic, and geographic dynamics surrounding the production, circulation, and consumption of given artefacts that confer or imbue them with recognizable value (

Stark 2009;

Brighenti 2018). From a pragmatist perspective, value is to be reconstructed as the outcome of situated activities of valuation, including, for instance, indexing, measuring, comparing, and so on. Under this lens, urban graffiti represents a controversial artefact, not only due to its blatantly stubborn and even chaotic appearance in the urban landscape, but particularly because it challenges and/or eludes clear-cut categories of economic, legal, moral, and aesthetic value. In the space of cultural practices, graffiti has been said to occupy an interstitial location spanning across different social fields—including, for instance, art, design, decoration, youth culture, and so on (

Brighenti 2010). Such an interstitial position makes graffiti inherently resistant to all attempts to seize it in any univocal way as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’, either ‘valuable’ or ‘worthless’, ether ‘beautiful’ or ‘ugly’, either ‘clean’ or ‘dirty’. Graffiti, in other words, remains available to be ingrained in potentially divergent, even incompatible, circuits of valorization.

The literature on graffiti writing—or, as it is sometimes also called, the ‘style-writing’ game (Phase2, quoted in

Ferri 2016)—has emphasized the peculiar normative system that contradistinguishes this creative practice, including its background in street cultures and youth cultures, its logic of recognition through visibility and distinction, its orientation towards achieving respect through claims of originality, and so on. Not only is graffiti imbued with its own social normativity, but it can also be said to be an integral part of what the legal philosopher Andreas

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos (

2015, pp. 66–67) has called

the lawscape. The lawscape refers simultaneously to different processes such as the infusion of law in physical and social space, the spatial effects of juridification, and the practical complexities of concerting legal pluralism in social life. In particular, as we are going to consider more in detail below, the theory of radical legal pluralism advances an approach to the lawscape that evinces the legal aspect of social life beyond the domain of positive law (

Macdonald 1998,

2007). In this vein, the many controversies, conflicts, and misunderstandings surrounding graffiti can be explained as instances of a situation of expanded urban legal pluralism, resulting from the peculiar topology of the lawscape, contributing, in turn, to shape it.

To entertain this hypothesis, the discussion is organized as follows. In the first part of the piece, we proceed to outline a very short history of graffiti policies, highlighting three chapters in this history, in terms of the urban policies that have been deployed to regulate graffiti. These, of course, are not tightly bound, nor even exclusive, but indicate broad tendencies in the contemporary dynamics of valorization. In the second part of the piece, we move on to examine how graffiti itself actively participates, not simply in populating, but in the actual making of the lawscape, especially once the lens of radical legal pluralism is adopted. In the conclusion, we recapitulate the discussion by highlighting the chief predicaments inherent in the current circuits of valorization in place.

2. A Short History of Graffiti Policies

Let us consider, to begin with, the legal frameworks that have been deployed to frame graffiti. Three major historical steps in graffiti policies can be singled out, which we may call, respectively, repression, negotiation, and capture. While these stages are historically successive, they have in many places also coexisted, so that any linear narrative is revealed as untenable, and the overall situation may as well be defined as one of

divergent synthesis (

Brighenti 2015b). Graffiti repression is historically the first policy to have appeared and, in several places around the world, is still the dominant one. The repressive approach represents a type of extermination aesthetic; typically, policies informed by this vision generously mobilize the war lexicon—war on graffiti, war on incivility, war on disorder, war on degradation, etc. There are interesting parallels with urban health policies concerning parasites, such as rat infestation and similar phenomena (

Biehler 2013;

Adams and Ramsden 2024). Vegetal invasion (weeds) also feeds analogous images (

Parisi 2019). At this stage, graffiti is regarded as an untamable force to be destroyed with frontal assault and without further ado.

Ultimately, the extermination framework proved to be a failure insofar as it never managed to deliver its promise of completely eradicating graffiti from cities (

Iveson 2009). Moreover, it also, paradoxically, created a self-perpetuating vicious circle epitomized by an anti-graffiti industry with vested interests in the continuation of an endless war (

Shobe and Banis 2014). This may contribute to explaining the progressive rise of a second framework, namely negotiation. Negotiation policies seek to come to terms with graffiti by applying a naturalistic gaze to it: graffiti is now regarded as a peculiar manifestation of

natura urbana (

Gandy 2022), more specifically as an instance of irruption that cannot be defeated in the absolute sense, but only reined in within acceptable thresholds. Moving away from straightforward punitive retribution, the emphasis of this second set of policies turns towards preventative or preemptive measures directly implemented in the urban environment (

Lombard 2013). In this more realistic take, the pivotal point shifts from elimination to containment or, as

Young (

2010) described it, to the orchestration of ‘negotiated consent’. Negotiation activates a different valorization circuit, to the extent that it also paves the path towards the recognition that, in graffiti, there may be artistic merit, too. Negotiated consent has led to policies whereby a number of legal walls have been assigned to writers and supportive cultural groups in an attempt to implement a policy of

attraction (understood as the obverse of concentration). The effort, in other words, goes towards trying to keep writers within allotted places (

McAuliffe 2013;

Kramer 2016).

A third framework emerges from the moment when graffiti (and increasingly, not only the artefacts, but also the places where they exist) starts being regarded as compatible with creative capitalism (

Schacter 2008). At this point, graffiti—inconsistently yet increasingly rebranded as street art, although the two terms are hardly equivalent—comes to stand for one of the very symbols of a new creative class inhabiting vibrant and colorful neighborhoods populated by artists, designers, photographers, filmmakers—and then also advertisement consultants, entrepreneurs, lawyers, as well as other happy innovative professionals heralded by the vision known as ‘the creative city’ (

Landry 2000;

Florida 2002).

Let’s now go back to the first framework and see how it unfolded historically. In New York City, the criminalization of graffiti began in the mid-1970s, under the John Lindsay administration (1966–1973). As Tim Cresswell summarizes:

Throughout the early and mid-1970s, when New York was facing bankruptcy, Mayor Lindsay made the fight against graffiti a priority issue on his political agenda and millions were spent in vain attempts to deal with the ‘epidemic’. Guard dogs were placed in station yards, new types of graffiti-resistant paint were tried out, laws were passed forbidding the possession of spray paint in public places, special anti-graffiti forces were created, a monthly anti-graffiti day was instituted in which boy and girl scouts cleaned up defaced subway trains and public buildings. Ten million dollars were spent in 1972 on attempts to clear up graffiti (NYT 28 March 1973, page 51). In 1973, 1562 people were arrested on graffiti charges (NYT 14 January 1973, page 14).

In the early 1980s, New York City started implementing Broken Windows Theory (

Kelling and Wilson 1982), which subsequently resulted in the turn towards the so-called Zero Tolerance urban policy under the Giuliani administration (1994–2001) (

De Giorgi 2000). But, as reported by Cresswell, a similar trend had already been under way since the previous municipal administrations, such as Lindsay’s (1966–1973), Koch’s (1978–1989), and Dinkins’s (1990–1993). The 1992 New York Penal Law, for instance, classed the possession of graffiti tools as a ‘type-B misdemeanor’. More specifically, it stated:

A person is guilty of possession of graffiti instruments when he possesses any tool, instrument, article, substance, solution or other compound designed or commonly used to etch, paint, cover, draw upon or otherwise place a mark upon a piece of property which that person has no permission or authority to etch, paint, cover, draw upon or otherwise mark, under circumstances evincing an intent to use same in order to damage such property.

1

This reveals a trend in legislation towards becoming increasingly specific in seizing the practicalities of graffiti production as ways for early apprehension and identification of writers. But at the same time, the narrative became broader. A couple of years later, in 1994, the Police Strategy No. 5 report, signed by the then-newly-installed Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his Police Commissioner William Bratton, declared that crimes such as graffiti impinge on the citizens’ capacity to ‘enjoy public space’.

2 Following the Broken Windows Theory approach, a plethora of apparently minor unsanctioned behaviors were then regarded as expanding urban disorder and igniting a downward spiral of civilizational decay.

During the 1980s and 1990s, municipal authorities started focusing their attention on so-called ‘petty criminality’. Graffiti was then easily fitted into that category: not only was it framed as a social problem, but it was also critically seen as an expression of a broader spectrum of behaviors under the wide umbrella of ‘urban violence’ (

Pavoni and Tulumello 2023). During the 1990s, the repressive approach dominant in the US reverberated across many cities around the world (see

Figure 1).

For instance, beginning in the late 1990s, several cities across the Scandinavian peninsula adopted a series of zero-tolerance policies. Emma

Arnold (

2019) has reconstructed, in particular, the case of Oslo.

3 Between 2013 and 2017, she conducted a study on the implementation of neoliberal urban policies in cities with a traditionally strong welfare state. She was surprised to find a particularly harsh legal machinery in place:

Measures include practices of censorship, media campaigns, education and outreach targeting youth, regulation of spray paint and other materials, refusal of permits for legal walls and murals, outright banning of legal walls, in addition to aggressive buffing, policing, and punishment.

According to Oslo City Council, a graffiti writer could be fined for each single tag, with an exponential accumulation of fines, paired with ‘harsh punishments, unconditional prison sentences and large compensation orders’ (

Høigard 2011, p. 313). Such a repressive approach extended well into the 2000s. For instance, in 2006, the city of Melbourne passed its first Graffiti Management Plan, also largely informed by Zero Tolerance (

Young 2010). The second version of the plan (dated 2009) even toughened penalties for writers, giving public authorities the right to directly remove graffiti from private property if the property owner did not object. As remarked by

Young (

2010, p. 112), ‘it is hard to take seriously the idea that a property owner’s wish to retain a tag or stencil will trump the underlying assumptions that graffiti is a social problem’.

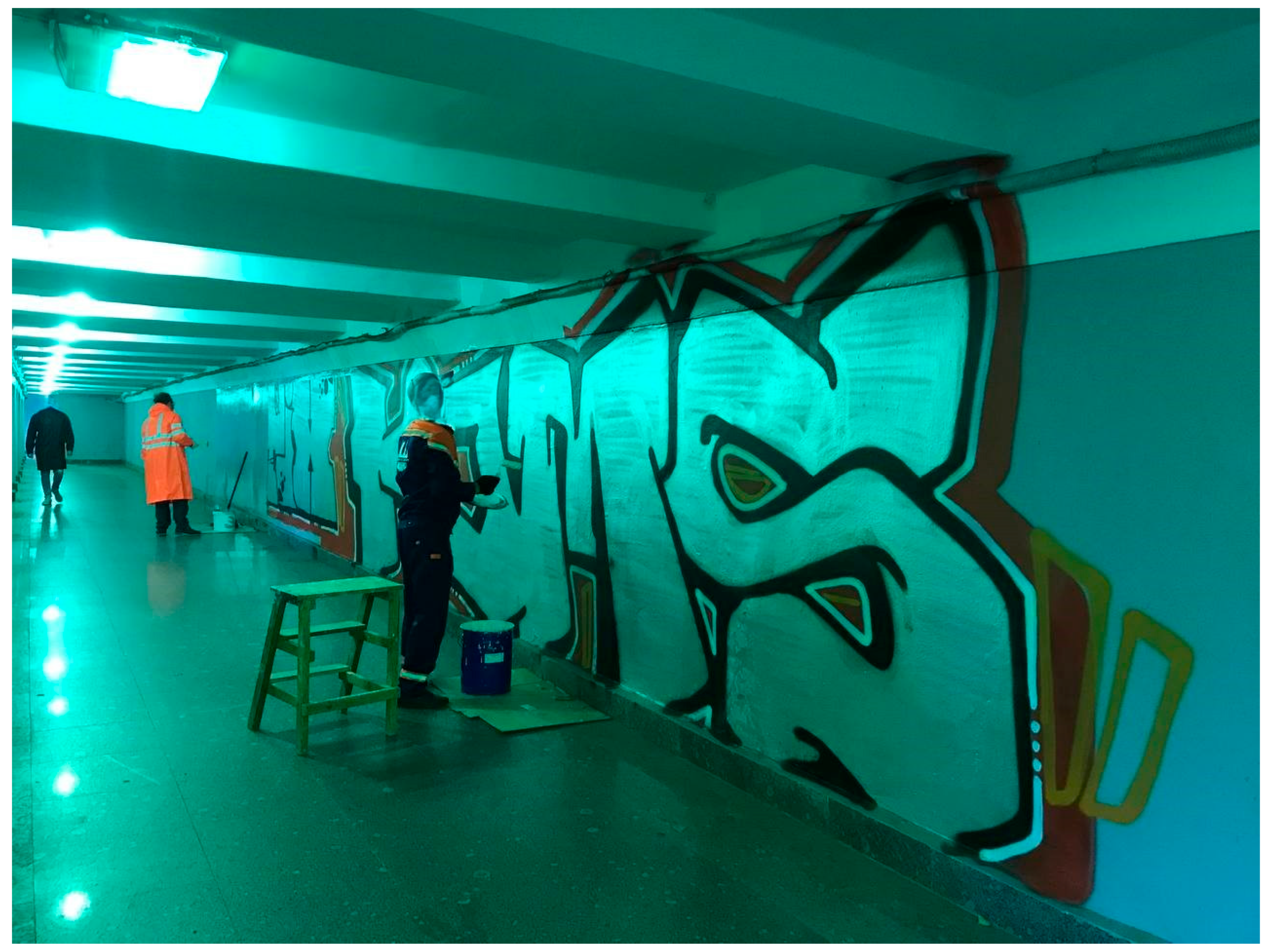

By the early 2000s, a different approach had made its appearance. The second chapter in graffiti policies was, as hinted above, marked by various forms of negotiated consent, partial acceptance, and containment-confinement strategies (see

Figure 2). For instance, the city-state of Singapore is known for its draconian policies when it comes to public order. Its Vandalism Act is broad enough to define any form of illicit aesthetic work as vandalism (Chapter 341, Section 2, in force since 1966, revised in 2014). Since 2012, however, the traditional ‘graffiti-averse and litter-free’ approach has been toned down to a degree. A few selected instances of originally illegal graffiti works have even been sanctioned and protected as elements of ‘heritage’, and in 2010, the first legal walls for graffiti were established. The word ‘street art’ appeared for the first time in official documents in 2013 with the ‘PubliCity’ program, which reserved two walls along an abandoned railway for urban creations (Seah 2016, quoted in

Chang 2019). Such space is managed by a local arts collective. The same year, the local graffiti artist Zul Othman, aka ZERO, was awarded Singapore’s National Arts Council Young Artist Award, becoming the first graffiti-inspired artist to receive the distinction. The key to this approach seems to be zoning, with strict legislative guidelines on ‘how and where such works may be allowed to flourish’ (

Chang 2019, p. 1051)—outside of which, graffiti is repressed as hard as possible.

In Saint Petersburg, Russia, graffiti legislation has been implemented since the mid 2010s, mostly within the framework of vandalism:

As noted by the representative of the Committee, the placement of graffiti can only be considered as an act of vandalism that violates the architectural appearance of the city and negatively affects the condition of building facades.

(Saint Petersburg’s Urban Planning and Architecture Committee, 6 November 2020).

At the same time, a City Council committee has also laid out a series of guidelines to regulate graffiti placement on the city surfaces

4. According to these guidelines, urban artists can intervene on urban surfaces when their interventions conform to the stylistic qualities of the surrounding environment and are previously allowed by the owner of the building (either public or private), and then also by the Urban Planning and Architecture Committee.

Through the stage of negotiated consent and containment, a third historical moment has emerged. Since the mid-to-late 1990s, and more prominently since the early 2000s, the cultural industries have ingested a good deal of subcultural production, contents, and styles in the fields of music, design, visual communication, and the visual arts. With the institutionalization of street art inside galleries and museums around the world (

Bengtsen 2014), graffiti is subject to a progressive ‘artification’ (

Shapiro and Heinich 2012), i.e., a process of transformation of non-artistic materials and products into artistic ones, fully inserted in the official arts venues. Although artists employing the language of graffiti have been around since the times of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, with the expansion and valorization of urban creative practices, the link between graffiti and the art world has strengthened significantly. Also, new figures of cultural entrepreneurs, event organizers, curators, art dealers, and new audiences have materialized to amplify graffiti valorization. In the field of urban governance, the shift from industrial to postindustrial economic models (with the latter more focused on consumption and lifestyles), and from bureaucratic to entrepreneurial urban management, has led to the implementation of cultural policies where graffiti—particularly when their aesthetics and style conform to a conventional understanding of hip and cool and can be more easily conducive to artification—have been ingrained in a number of regeneration projects and urban branding strategies.

Traditionally, graffiti was an artefact scattered across the cityscape as a nomadic commentary on the peculiarities of urban sites and spots—often abandoned industrial lots, or transport infrastructures designed only for functionality and often associated with anomy and lack of safety. By contrast, the new urban geography of graffiti has tended to concentrate graffiti in key sites at neighborhood or even street level, to the point that some of these locations have turned into veritable mecca destinations for artists, aficionados, and subsequently also tourists. Graffiti tourism towards global iconic places such as Hosier Lane, Melbourne, Australia, the East Side Gallery along Mühlenstraße, Berlin, or Rue Denoyez in Belleville, Paris, attest to this phenomenon (see

Figure 3). Increasingly, official ‘street art districts’, such as 798 in Beijing, have been launched, along with promotional ‘temporary urbanism’ projects, like ‘La Tour Paris 13’, which in 2013 turned a soon-to-be-demolished decrepit housing estate into a temporary exhibition space for writers and international artists. In the third moment, graffiti intersects processes of gentrification and neighborhood upscaling, with street art increasingly serving as the bohème milieu apt to prepare the advent of the next wave of real-estate capital investment.

As entire urban areas have been converted from an economy of production to one of consumption (

Zukin 2009), graffiti has been brought more and more out of its original subcultural field, towards larger societal recognition (

Campos 2015;

Kramer 2010). Sabina

Andron (

2018) has called this trend ‘selling streetness’. While certainly this has not stopped controversies surrounding graffiti, it has paved the way towards a new set of urban policies and regulations. Within the ‘creative city’ framework, graffiti has been increasingly included in the range of accepted and even encouraged beautification strategies deployed by cities. In this context, graffiti has been reinterpreted as an added-value ingredient of the urban visualscape. Examples of the implementation of urban policies that include graffiti and street art to create added value abound in cities and towns worldwide, large and small—and even in rural areas. A curious instance of the latter is the village of Aielli, in central Italy. A yearly graffiti and design festival, Borgo Universo, has been convened there since 2017. Developed by the city council with the purpose of telling, through street art, ‘the history of the town and its unique contact with the cosmos’,

5 Borgo Universo attracts tourists from all over the world. Another case in point is Dlala Indima, South Africa, where the project ‘Two Thousand and Ten Reasons to Live in a Small Town’, by the Visual Arts Network South Africa (VANSA), was launched in 2010 in peripheral neighborhoods as an alternative to the official commissions of public art projects made on the occasion of the FIFA World Cup (

Sitas 2020).

Such a reorientation towards the progressive inclusion of graffiti appears to have been initiated not directly by the public institutions, but rather mostly by private actors, such as business companies, cultural entrepreneurs, local associations, etc. However, some cities have been quicker than others to seize the potentials of what

Strom and Kusenbach (

2020) have called the ‘bohemia growth machine’. And it is in this sense that we can speak of a third moment in urban policies, when graffiti gets ‘captured’ by urban governance. From this perspective, the case of Miami’s Wynwood neighborhood is outstanding. There,

street art has become such a powerful part of the area’s brand, even the growing stock of new buildings often features murals commissioned by building owners. In one case, according to our tour guide, a development company purposefully designed their building to include blank walls that would be suitable for a highly visible mural, giving up rentable living space to do so.

In Europe since the 2010s, cities like Berlin and Paris have extensively invested into capturing graffiti culture (

Vaslin 2021). Similarly, Lisbon has defined five main strategic goals that encompass a wide array of policies ranging from urban and cultural redevelopment to social and democratic inclusion to rebranding the city’s image (

Campos and Barbio 2021). Urban art has been largely mobilized towards all these aims, highlighting how broad its use in urban planning can be and, consequently, in its entailments. In particular, according to

Costa and Lopes (

2015), the Lisbon City Council has sought to pursue an approach to urban problems that focuses on disadvantaged local communities, seeking to contrast uneven urban development (

Costa and Lopes 2015). The policy has been so successful that, in less than a decade, it has led to a situation where paradoxically street art has become detrimental to local residents. Indeed, the top–bottom strategy has led to excessive touristification, creating serious economic and logistical problems for local dwellers. A good example of this outcome is discussed by

Raposo (

2023), who has focused on the social housing neighborhood of Quinta do Mocho in the Greater Lisbon area. There, street art regeneration projects have ultimately turned into an additional factor in the reproduction of marginalization, with the artworks being imposed upon the local inhabitants, whose opinions and attitudes were almost completely overlooked in the decisional process.

Similarly,

Usingarawe et al. (

2019) discuss the case of the cities of Harare and Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. Here, too, graffiti appears to be integrated into the strategic plans to make the city competitive in the international panorama, promoting a cultural tourism agenda. In Harare, graffiti writing was hardly ever criminalized and is considered a criminal offense (contravening the Electoral Act) only when a formal complaint is lodged to the Police by the owner of the property on which a piece of graffiti has been made, which is a rare occurrence. In Bulawayo, there is not even a legal provision concerning how to deal with graffiti. The presence of a similar graffiti-friendly environment leaves open the question of whether policies strategically embracing graffiti style and aesthetics for cultural tourism purposes may, in the long run, also lead to gentrification and displacement. In this vein, we have already evoked above the case of Dlala Indima. According to

Sitas (

2020), in South Africa, graffiti has been used as a catalyst for real estate property developments, in line with the instrumentalization of culture for economic gain (Miles 2005 in

Sitas 2020). However, Sitas also argues that more participative and communitarian strategies, such as challenging the normative process of regeneration and calling for more participatory practices, have been deployed in Dlala Indima in a way that should be able to resist expropriation as an outcome.

Yet, the problem of who expropriates whom is a lingering one. As we have also suggested elsewhere (

Brighenti and Brazioli, forthcoming), the legalization of graffiti implicitly also sanctions its submission to the law. New expert referees and evaluators, none belonging to graffiti subculture, such as galleries, museums, urban developers, and political actors, set in, claiming to be the legitimate subjects who are competent in giving graffiti its due. Unsurprisingly, graffiti artists themselves are far from unanimous in their reactions to the new situation and, in many cases, are even puzzled by the outcomes of legal recognition, for instance, in terms of copyright law (

Bonadio 2023). While graffiti has always been entangled with the law in one way or another, its artification amplifies the visibility of such a structural condition and invites some further considerations.

3. Lawscaping Graffiti, Graffitiing the Lawscape

As said above, the inclusion of graffiti into the mainstream cultural governance of cities worldwide has not prevented its continued criminalization but has rather resulted in a variegated scenario of simultaneous expulsion and capture. The present situation can be described as one of opposing, even contrasting, and yet concurrent, appreciations of the practice—a veritable ‘divergent synthesis’ (

Brighenti 2015b). So, while the visualscape of the street forms a kind of ‘visual dialogue’ constituted by the alternance and the overlaps of tags, advertisement, billboards, commissioned murals, legal walls of fame, previously buffed works—an actual ‘surface commons’ (

Andron 2024)—in the courts of law, a string of verdicts alternatively convicts and acquits graffiti writers according to highly contextual variables, such as the momentary sensitivity of a judge and one’s personal understanding of graffiti. For instance, Christian

Omodeo (

2013) has reported on two legal trials which took place in Northen Italy, in Milan and Treviso, respectively, to highlight how the legal outcomes (one defendant was convicted while the other was acquitted) were highly contingent on the judge’s personal interpretation of the perceived motivations of the writer. If the judge does not aesthetically appreciate graffiti, then the defendant is more likely to be convicted of the criminal offense of ‘damaging’ or ‘disfiguring and soiling’ property

6, whereas conversely, if the judge recognizes that graffiti can also be an art form, the defendant is more likely to be acquitted based on the constitutionally enshrined right of ‘freedom of expression’.

Urban policies, as we have seen, have struggled with applying to graffiti legal-moral distinctions between ‘legitimate’ (‘clean’, ‘beautiful’, ‘good’) graffiti, on the one hand, and ‘illegitimate’ (‘dirty’, ‘ugly’, ‘evil’) graffiti, on the other. The graffiti lawscape is complicated by judgments and decisions about which pieces should be considered as ‘appropriate’ and ‘in place’, and which ones ‘inappropriate’ and ‘out of place’ (

Cresswell 1992). Inevitably, this implies a difficult and precarious search for legitimate referees. Such imbrication of legal and aesthetic appreciations has also been remarked and discussed by

Baldini (

2017). The recalcitrant nature of graffiti, whereby graffiti writers appear consistent in reproducing an aesthetic of transgression that reclaims for itself space in the city ‘by all means necessary’, makes the search for such referees particularly tricky: it is the lack of consensus, in a sense, that preserves graffiti’s very nature.

Graffiti writers have been often depicted as individualistic and opportunistic actors, as ‘free riders’ uninterested in the common good and insensitive towards what they leave behind. But the relation between graffiti and the lawscape is more subtle. As we have seen, the legal philosopher Andreas

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos (

2015, pp. 66–67) has defined the lawscape as ‘the way the tautology between law and space unfolds as difference ’, meaning ‘the virtuality of the law that is potentially law at any point’. The lawscape, in other words, constantly evokes law as the type of virtuality that comes to occupy (perhaps conquer, master, or subvert) the available space. ‘Lawscaping’, continues

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos (

2015, p. 89), ‘is an act of repetition of the here/now and the way the past passes through it, that aims at capturing the future’. The lawscape thus asserts itself through repetition in the form of an ‘actual present’, which in fact cannot stop producing difference in the mode of virtuality.

If law is generated in exchanges of affects, as the lawscape perspective suggests, then graffiti is not to be seen as simply a subject of urban governance, but must be appreciated as something that, in turn, contributes to crafting the lawscape by injecting, to various extents, its own rationale into it. For instance, it is interesting to consider the sense of entitlement that derives from given conceptions of righteousness. One particularly telling case comes from downtown Los Angeles, California. After the construction of three 40-story luxury condos (a development known as Oceanwide Plaza) was in 2019 stopped due to the developer company running out of funding (or bankruptcy, not clear), massive graffiti started popping up on the towers, covering a good part of their visible surface (

N S 2024). One writer who signs Endem thus expressed his feelings:

So, if the actual owner is not there, if he’s not making his voice heard, if he’s not defending his property, then it’s fair game. He’s basically forfeiting it to the city, you know? So, we took it over. We just got the scraps of what was left over.

Working on urban scraps and left-overs, the graffiti writer feels that graffiti cannot be such terrible damage after all, because ‘the building was already ugly’—or, as

N S (

2024) comments, it was ‘just another soulless copy-paste money-making glass cube’. The writer then can consider himself or herself as operating on parts of the city that have been abandoned by their previous owners and have accordingly become what the architectural philosopher Stavros

Stavrides (

2016) has called ‘common space’. Stavrides has argued that ‘space-commoning’ includes a set of expansive practices, whereby even acts of ‘defacement’ can create thresholds towards rediscovering previously overlooked commons:

Defacement creates sudden shocks in collective memory by bringing forth inherent contradictions hidden in the foundations of the common world … Defacement, thus, may evoke interpretative practices that give ground to new shared knowledges.

Defacement matters, in the first place, not for its immediate material consequences (which, however, are also to be factored in), but for its

gestus, its eye-opening potential. As part of a ‘natural history’ of the city (

Park 1925), graffiti contributes to that urban ecological trend whereby all that is private and abandoned, or deserted, is sooner or later bound to dissolve and revert to ‘the common’. Yet, graffiti does so through a disruptive gesture that, by accelerating and intensifying the

natura urbana state of commonality, also awakens and heightens consciousness. That is why graffiti intervention, through its conflicting, iconoclastic aesthetics, also molds the lawscape as an ongoing virtuality of transformation (i.e., what the philosopher calls ‘difference’). Located at the intersection of a process that is both natural (the decaying ruin, the growing weeds) and cultural (the inception of a new law), graffiti makes assertions that are not simply direct (the ‘in-your-face’ effect of the tag), but also

environmental. As one might also say, graffiti makes meta-assertions. This is also what Rafael

Schacter (

2024) has recently suggested in his interpretation of graffiti as monument. Graffiti, Schacter contends,

functions not solely through its immersive emplacement within the dense gravity of the city but through techniques of rejection and resistance to that same emplacement: Here we thus find a rejection of the material coherence of its medium, a resistance to the structural and functional rationale of its surface.

By operating ‘interruptively’ vis-à-vis the seamless continuity of the urban landscape, graffiti functions as a punctual reminder (sive, a monument-admonishment) of the inner plurality of the lawscape, of its divergent possibilities. Its perspective is, as Schacter suggests, irruptive, marginal, ephemeral, and dialogical. The approach of radical legal pluralism, particularly as elaborated by the Canadian constitutional lawyer and legal theorist Roderick Alexander Macdonald through the 1990s and early 2000s, seems particularly apt at capturing this fact. Radical legal pluralism can be said to inherit the philosophy of Peircian pragmatism, with its thick conception of agency being revealed in the various forms of—either explicit or implicit—principles for the orientation of conducts. The nexus of law is discussed by legal pluralism as inherently triadic, that is symbolic in nature. It is indeed through symbol that law can become effectively purposeful. As Peirce himself first put it:

A symbol is essentially a purpose, that is to say, is a representation that seeks to make itself definite, or seeks to produce an interpretant more definite than itself. For its whole signification consists in its determining an interpretant; so that it is from its interpretant that it derives the actuality of its signification.

The interpretant is the ‘effect’ of a sign, the ‘cognition’ or ‘idea’ the sign is able to engender. In Peirce, the category of thirdness concerns the ubiquitous living tendency in nature towards ‘habit-taking’. Such is, for instance, the tendency to ‘contract’ relations that evince new meaning in events, acts, and conducts. Along these lines, Macdonald clarified the import of legal pluralism as fully opening up the field of law to social actors, leading to an ‘alternative image of law and legal normativity’:

a legal pluralistic approach frees the legal imagination from structuralist thinking; it frees legal conceptions of normativity from the assumptions of Weberian formal-rationality; and it frees legal notions of relationships from their anchorage in official institutions of third-party dispute resolution.

The issue at stake in such a ‘liberation’ of the legal imagination concerns the origin, or emergence, of law, and consequently, its social geography. Here again, radical legal pluralism asserts that normativity is necessarily ‘secreted in patterns of deference and contestation to tacit (and occasionally, virtual) claims of authority’ (

Macdonald 1998, p. 77). In other words, there cannot be law that is not also simultaneously a discussion of purpose, commitment, and relationality (that is why, in legal theory, radical legal pluralism endorses the philosophy of Lon L. Fuller, who depicted the law as an inherently purposeful and motivational endeavor, in opposition to Herbert L.A. Hart’s positivist view of law as text). Particularly through the prism of everyday law, Macdonald emphasized that mundane experiences, such as everyday negotiations and recriminations among family members, are not structurally separate from law:

It’s not as if there is analogy of what goes on in the family as what goes on in law, because what goes on in the family is already law. An allegory is a story which is meaningful on its own but by which there is also something else to be learned. An allegory has a parabolic character.

The continuum of law, in other words, is kept together by the symbolic activity of people as they work jointly to make sense of each other’s conducts and aspirations, trying to figure out through a number of ‘allegories’ what could be

just for them. In the light of the radical legal pluralism outlined by Macdonald, graffiti can be revealed as itself

nomopoietic, i.e., institutive of new law, rather than simply an inert object of urban policies. By its own existence, graffiti inserts a distinctive dynamism into the lawscape, as specifically seen in its irruptive

gestus. Such a ‘defacement’ moment is not gratuitous; rather, it occurs as a prolongation of the specific commitment the graffiti practice engenders among its practitioners in the first place (

Ferri 2016). Certainly, graffiti is not unique in carrying out some type of irruptive, ‘monumental’ accomplishment in the public domain. And clearly, to the extent that graffiti becomes programmed or even expected, it is bound to fail at that crucial test.

Still, since the law would be incomplete and ultimately meaningless without an aspiration to justice, i.e., without ‘thirdness’, graffiti is a necessary part of it. For justice is a conversation. Following

Derrida (

1967),

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos (

2015) has framed spatial justice as a ‘geography of withdrawal’, whereby what is asked of us whenever facing justice is to take a step back and leave space so that the other can breathe. Now, at first sight, both graffiti and the law appear to work largely by occupation: they invade cities and more broadly infiltrate social life. Both want to grow, seeking to position themselves as always ‘between us’. Of the lawscape, it could also be said: one cannot do without. But what is thus potentially produced is also a tendency to suffocation. Only some fresh air can grant the event of justice, and that happens when occupation gets reversed. The moment of

desistance is no less essential than the moment of appropriation. That is why Derrida connects the act of withdrawing [

se retirer] with what he calls ‘unpower’ and embeds both at the secret sources of inspiration:

The generosity of inspiration, the positive irruption of a speech which comes from I know not where, or about which I know (if I am Antonin Artaud) that I do not know where it comes from or who speaks it, the fecundity of the other breath, is unpower [l’impouvoir]: not the absence, but the radical irresponsibility of speech, irresponsibility as the power and the origin of speech.

Just like speech for Derrida, graffiti is, first of all, ‘irresponsible’. The law seeks to hold it accountable; yet, by doing so, the inner tensions and contradictions of its claims of authority are also exposed. Value cannot be produced by law, but necessarily come to see the light of day along the way, during that quirky and clumsy conversation known as the public domain. Importantly, these conversations should not be expected to be symmetrical sequences—for each ‘statement’ made in their unfolding comes with its own different measure. If law is to evoke justice, then unpower must find its ground among these measures. Hence, the perspective of unpower haunting the lawscape is, we believe, extremely fruitful to address the circuits of valorization harbored within it.

It is not impossible that Derrida’s

unpower has something to do with humor.

The subconscious art of graffiti removal is an experimental video by Matt

McCormick (

2002) that compares graffiti removal to a type of urban art ‘with roots in abstract expressionism, minimalism and Russian constructivism’. In this playful mirror image of graffiti writing, the practice of removal (or cleansing, colloquially: ‘buffing’) is seen as itself a complete art form, although removers are said to be unaware of their own artistic merits (hence, a ‘subconscious’ art). The fact that graffiti removal art is enjoying increasing critical acclaim, the narrator goes, also explains the growing funding allocated to anti-graffiti campaigns. Although ‘removal art’ proceeds through a deliberate attempt to ‘repress communication’, its aim is never achieved and, in fact, removal cannot but engage in a sort of dance with the graffiti it buffs, either through ‘boxing’ it, ‘ghosting’ it, or through any other procedure.

When it comes to understanding the circuits of graffiti valorization, the perspective of graffiti removal as a specific genre in contemporary art forces us to swap some perceptive considerations. Indeed, the very notion of ‘unintentional’ art provokes us to think about urban environments as potentially sites of unrestrained artistic creation, in a sort of Situationist revolution of everyday life. At the same time, creation is, at least in part, always in the eye of the beholder. What McCormick says of graffiti removal—namely that is it both ‘accidental’ and ‘collaborative’—could similarly be said of graffiti itself. Even in the eventuality of a city coinciding with a global artful entity (as a near-dystopian completion of the third historical stage of graffiti policies discussed above), what remains established is, at bottom, the fundamental asymmetry of publicness as quirky conversation. Both graffiti and graffiti removal embody acts of ‘painting over’. Things (gestures, actions, criteria, value) cannot but constantly be added to the public domain. As the wall gets layered, as it gets thicker and thicker with communications, there is no simple ‘erase’ function, and the only way to proceed is by adding further stuff, in a way that may be (alternatively or simultaneously) either dialogic and collaborative or accidental and dumb—such is, precisely, the fundamental condition of the public domain. In a sense, more widely, all life proceeds this way.