Abstract

This study leverages emotional arc modeling along with close reading to examine the Chinese Ye Xian, Perrault’s Cendrillon, and two Grimm versions. While computational modeling suggests that Cinderella tales share similar “recognition scaffolds,” their emotional architectures reflect distinct moral universes. Story peaks and valleys vary according to individual narrative resolutions to a universal problem of virtue unrecognized. Ye Xian descends to maximum negative sentiment when sacred bonds rupture, aligning with Buddhist-Daoist ethics in which divine-human reciprocity supersedes other bonds. Perrault’s arc offers surprising asymmetry: linguistic violence (Culcendron) defines every valley, while material transformation marks every peak. The 1812 Grimm tale oscillates between degradation and elevation with peaks and valleys suggestive of a syncretism between folk magic and Protestant theology. The 1857 version flattens into a rough semblance of Perrault’s emotional architecture, but peaks and valleys reflect Protestant, rather than aristocratic, values. These many shapes of Cinderella suggest fairy tales may serve as a flexible emotional technology. Themes of good and evil are key features of these emotional architectures, but how they are expressed vary from tale to tale.

1. Moral Categories and the Recognition Problem

The Cinderella fairy tale presents a fundamental paradox: while the story’s basic shape—virtue unrecognized, then revealed—appears universal, the emotional and moral architectures of individual variants differ dramatically. This study examines how computational modeling of emotional arc surfaces these culturally specific moral worlds embedded in the language of four well-known Cinderella tales. While folklore studies have long examined how tales are transmitted and transformed across cultures (Dundes 1982), our computational approach focuses on the emotional and moral architectures embedded in the language of written variants.

This paradox becomes particularly evident when examining how scholars have approached morality in the genre. Maria Tatar observes that fairy tales “seem to resist wholesale assimilation of a moral outlook,” offering “mixed signals” such that “it is rarely possible to find a story that does not encode competing moral claims” (Tatar 1992). Zipes (1979, 2012) argues that fairy tales can challenge rather than reinforce bourgeois moral categories, while Bacchilega demonstrates how contemporary retellings deliberately amplify moral ambiguities present in traditional versions. Scholarly consensus, in other words, suggests that moral complexity may be a hallmark of the genre.

At the same time, however, Cinderella variants have long been assessed as part of a larger classificatory approach that finds underlying commonalities. The ATU (Aarne-Thompson-Uther) index identifies core structural elements—persecuted stepdaughter, magical aid, recognition at an event, happy ending—that unite variants across cultures. Recent work moves in the opposite direction, emphasizing how fundamentally different these variants are in their cultural values, narrative details, and ideological functions. None of these approaches, whether they pertain to the moral ambiguity, structural similarity, or cultural difference, fully explains the tale’s remarkable persistence across such diverse contexts and time periods. The ATU’s structural skeleton tells us what elements recur but not why they resonate; cultural analysis surfaces local significance but not what makes the story recognizable across borders.

Recent computational approaches have addressed this paradox in new ways. da Silva and Tehrani’s (2016) phylogenetic analysis traces how Cinderella tales spread geographically, mapping their evolutionary relationships. Their work demonstrates that tale variants share identifiable “genetic” lineages. Certain plot elements cluster in ways that suggest historical transmission patterns, thereby illuminating how tales travel and mutate across cultures. Still, phylogenetic modeling, which focuses on the presence or absence of narrative elements, cannot capture why certain tales persist so powerfully. A tale’s “DNA” tells us what travels, but not what resonates emotionally.

More useful for understanding fairy tales’ continued resonance may be Kurt Vonnegut’s concept of “story shapes”—the emotional trajectories that mark tales like Cinderella as among the most elemental narrative patterns. Vonnegut’s theory has been computationally validated by Reagan et al. (2016), though they too assume universal patterns. Vonnegut mapped Cinderella as a series of dramatic movements: rising with magical aid, peaking at the ball, crashing at midnight, and ascending to happily-ever-after. When Vonnegut was writing, computers could not yet graph these shapes. But now they can, allowing us to ask: Do different Cinderella versions all evince the same story shape? And if they do not share the same shape, what do they share?

While we have become accustomed to thinking that character traits differ across versions—and they certainly do—characters also share certain stable functions beyond their narrative labels. In our test case variants, the Cinderella figure is marked as fundamentally good—but what this goodness means varies dramatically: Ye Xian’s virtue centers on reciprocal kindness (情, qíng), Perrault’s Cendrillon embodies aristocratic douceur (sweetness with refinement), and the German Aschenputtel demonstrates fromm und gut (pious and good) in a Protestant theological sense. These culturally specific virtues reflect distinct social anxieties and moral frameworks (Bottigheimer 1987; Tatar 1987; Warner 1994; Greenhill and Matrix 2010).

It would be easy to read the culturally specific aspects of “goodness” as cultural constructs rather than universals (Warner 1994). Different versions reflect distinct social anxieties and moral frameworks (Bottigheimer 1987), Venetian versions from the 1550s reflect urban merchant values, Perrault’s 1690s French version promotes specific court behaviors, and the Grimms’ versions reinforce bourgeois morals. Greenhill and Matrix demonstrate that these varying definitions of virtue persist even in contemporary adaptations (Greenhill and Matrix 2010). This work detailing how different the value systems are in each variant has been invaluable, since the tendency might otherwise be to gloss over variants in favor of a universal Cinderella story.

Culturally specific virtues are also quite gendered. Bottigheimer (1987) demonstrates how the Grimms systematically revised their tales across seven editions to increase female passivity and reinforce bourgeois gender norms, with Cinderella becoming progressively more silent and obedient. Carter (1979) and Bacchilega (1997) uncover how contemporary retellings challenge these representations. Yet even these critiques recognize a stable problem—that female virtue must perform itself through suffering even as it manifests differently across cultures. In all our variants the treatment of the stepdaughter is likely so emotionally compelling not just because she is a stepdaughter (and therefore without a protector) but because her virtuousness is so evident and yet so overlooked, a scenario that is highly plausible due to her status as stepchild.

This pattern of stable predicament with variable solutions supports da Silva’s (2002) contention about deeper symbolic patterns manifesting differently across cultures. The stability is not in the character per se but in the problem she embodies which, pertaining as it does to value systems, is both symbolic and concrete: virtue unrecognized and kindness exploited. While Bacchilega (1997) and Haase (2004) rightly emphasize these tales exist in “webs of cultural meaning” that may be mutually exclusive, an emphasis on infinite malleability may obscure the structural continuities that Propp (1968), systems like ATU, and Bettelheim (1976) identified. They weren’t wrong to see stable patterns, but they lacked tools to reconcile stability with variation.

The element that travels across time and space is not a complete character but character function not as Propp conceives it—that is, in ways that move the plot along through certain actions like helper or villain—but as an emotional function, and one that is most likely to resonate with the listener or reader. Building on Zipes’s (1979, 2012) analysis of fairy tales’ social and ideological functions, we might identify a “meaningful social problem” at the core of Cinderella variants: the inversion of values when true virtue goes unrecognized. Dundes (2007) demonstrates how folklore provides frameworks for addressing culturally-specific moral predicaments, and perhaps what makes these tales persist is their shared presentation of a problem—moral disorder—that demands resolution even as each culture imagines different solutions. Tatar (1992) explains that fairy tales serve as moral magnets with “competing moral claims,” but perhaps what magnetizes them is this core problem of moral disorder requiring resolution.

For the sake of space, we limit ourselves here to a set of variants that follows established scholarly practice (Dundes 1982; Tatar 2017; Bacchilega 1997) of comparing the earliest known written version with influential literary adaptations. We include Ye Xian, recorded by (Duan Chengshi c. 850 CE) during China’s Tang Dynasty (the earliest surviving written Cinderella variant, per Dundes and da Silva and Tehrani (2016), though oral precursors like Greek Rhodopis ~450 BCE share loose motifs), Charles Perrault’s (1697) Cendrillon, and two German versions by the Brothers Grimm—their 1812 Aschenputtel, which is closer to oral folk tradition, and the 1857 version, revised after seven editions for bourgeois family reading. While hardly comprehensive of the myriad Cinderella stories, these variants represent distinct historical moments, class contexts, religious frameworks, and relationships to orality and literacy. In these diverse contexts, how our moral problem gets resolved reflects each culture’s fundamental assumptions about justice itself. Unrecognized virtue creates a narrative pressure so powerful that every culture must imagine its own resolution, even when those solutions are in direct contradiction.

Different cultures imagine fundamentally different justice mechanisms. Zeitlin (1993) argues that Chinese variants highlight karmic justice over Western concepts of divine providence. Zipes (1991) suggests Perrault promoted aristocratic social harmony over retribution, while Tatar (1987) shows how the Grimms shifted from cautionary to punitive models across editions. Dundes (2007) was the first to identify these different justice mechanisms as culturally specific rather than universal.

The psychological tradition, dominated by Bruno Bettelheim’s influential The Uses of Enchantment, treats fairy tales as therapeutic tools that help children work through unconscious anxieties. Yet as we’ll see, our sentiment analysis complicates this claim. Only certain cultural versions provide the clear resolution Bettelheim describes. Structural approaches, pioneered by Vladimir Propp’s morphological analysis, identified thirty-one discrete narrative functions. Our sentiment analysis will suggest, however, that while these functions may appear across cultures, the emotional language surrounding these functions varies dramatically. Where Propp saw structural universals, our analysis suggests emotional diversity. Anthropological approaches, championed by scholars like Linda Dégh and Richard Dorson, insist that fairy tales must be understood within their particular social, economic, and historical circumstances. This approach accounts for cultural variation but fails to explain why variants of the same tale appear across such diverse cultural contexts. Computational analysis suggests a new synthesis of these approaches. These tales persist not because they provide universal meanings (contra Bettelheim) or serve consistent ideological functions (contra Zipes) but because they offer complete emotional architectures. Unlike more everyday narratives, fairy tale architectures make use of the full affective range from abject suffering to transcendent joy. Each culture fills this framework with different content, creating what appear to be different stories but are actually different emotional technologies built from the same affective scaffold. What travels across cultures is not an emotional arc or complete moral system, but an affective framework that each culture rebuilds slightly differently.

What if the very language of these tales—not just their plots or symbols—creates distinct moral worlds? While computational approaches like da Silva and Tehrani’s (2016) phylogenetic analysis track how tales spread and change, they miss their emotional and moral content. This emotional-moral architecture, found in the tale’s ability to access and organize extreme states of feeling, may explain their psychological power better than any moral or therapeutic framework.

2. The Shapes of a Fairy Tale: Moral-Emotional Architectures Made Visible

Kurt Vonnegut drew Cinderella as a series of dramatic movements, rising with the fairy godmother’s appearance, peaking at the ball, crashing at midnight, and ascending upward with the happily-ever-after ending. But do actual Cinderella variants follow this pattern? Our approach employs a well-researched method for surfacing these shapes using sentiment analysis, a way of tracking the emotional temperature of language itself. Rather than surface particular plot events directly, it tracks the valence of words over time, in our case ranging from maximum negative (−5) to maximum positive (+5). When applied clause by clause to our tales in their original languages, patterns emerge that complicate Vonnegut’s sketch. Ye Xian’s 112 clauses create asymmetrical double valleys. Perrault’s 257 build to a smooth aristocratic ascent. The Grimm variants generate different kinds of oscillation, with the 1812 variant showing constant reversals and the 1857 version demonstrating ascending plateaus.

Graphing a story using this method offers a variety of distances from which to analyze. Up close, with line by line reading, we have a process that is most like our traditional methods of close reading, albeit with a focus on affect. Every cruel word or joy-filled moment appears alongside many more neutral moments. Step back slightly and larger patterns emerge, like Ye Xian’s two unequal valleys of loss or Perrault’s smooth rise punctuated by linguistic violence. Pull back further still and stories begin to approximate Vonnegut’s simpler shape, even as the distance erases the granular detail. The Chinese ending where bones stop responding to the greedy king transforms from a dramatic drop to a softened decline with further distance. Perrault’s fundamental asymmetry between verbal harm and material remedy disappears. The Grimms’ Protestant conviction that recognition must be repeatedly earned smooths into simple ascent. (See Appendix A for technical methodology).

While Vonnegut imagined shapes that followed the good fortune and bad fortune of the protagonist, the computational method that has emerged to track these shapes is actually different, although the results often comport with Vonnegut’s intuition. Instead, sentiment analysis tracks the rise and fall of the language of sentiment (the valence of language, irrespective of emotional categories) over the course of the narrative without recourse to plot events, fortune, or character. This approach directly confronts what Nan Z. Da (2019) identifies as computational literary studies’ central dilemma: “What is robust is obvious… and what is not obvious is not robust.” When our analysis shows linguistic violence generates all valleys in Perrault while material transformation creates all peaks, the pattern is robust (mathematically consistent) but its significance—that evil operates through language while good remains mute in aristocratic culture—emerges only through careful interpretation. Validation that much of what is found aligns with previous scholarly interpretation is necessary, and in the pages that follow we will try wherever possible to note these confirmations. These are not obvious insights (if they were, scholars would not have written books and articles detailing them). Rather, when findings dovetail with established readings, it confirms that our computational modeling is capturing signal and not noise. Still, confirmation of existing theories is not all we seek. As demonstrated in The Shapes of Stories (Elkins 2022), sentiment analysis has the potential to uncover patterns that are difficult to notice using traditional close reading methods.

Our methodology employs clause-by-clause sentiment analysis of the original language texts —Chinese, French, and German—using large language models (LLMs) that, unlike earlier tools, can take into account context, historical language, and cultural nuance with varying degrees of precision. James Dobson (2019) rightly warns against scientism in digital humanities, but here we avoid hypothesis testing and opt instead for exploratory data analysis. The distinction is important, because interpretation happens at every step. Models serve only as interpretive tools, not as arbiters of truth. No conclusion should ever be taken as definitive but rather assessed based on a careful understanding of both the limitations and strengths of our model.

One benefit of an approach we term computational philology is that it allows us to understand ways in which language matters in ways that transcend translation (Elkins 2024). Sentiment analysis of original-language texts reveals how cultures create distinct emotional worlds through linguistic choices. The fish murder in Ye Xian generates deeper valleys than familial death, and this reflects the culture’s unique emotional value system. The Grimms’ broken folk pattern (two tasks instead of three) gains new significance when visualized as a rupture in an expected emotional architecture. These different emotional worlds prepare readers for different realities of good and evil, one where sacred bonds matter more than blood, another where breaking a folk pattern engenders serious consequences. Although traditional sentiment analysis was not as adept at handling much of this culturally-specific nuance, modern LLMs are increasingly able to handle these cultural and historical contexts when training data is sufficient. Our approach would be less useful for under-resourced contexts.

After analyzing each story individually, normalizing their different lengths allows direct comparison of Cinderella tales. This process stretches Ye Xian’s compact 112 clauses and Grimm and Grimm (1857)’s elaborate 315 to the same scale, making visible surprising consistencies and variations. Transformation scenes cluster between 40–55% of narrative progression across all versions, suggesting a shared sense of dramatic timing. All versions generate maximum positive sentiment at recognition moments, but the recognition itself varies. The fish choosing to trust Ye Xian enough to pillow its head represents reciprocal acknowledgment between human and the divine. Perrault’s prince gazing without speaking enacts aristocratic elevation through placement and visual confirmation. Grimm and Grimm (1812)’s correct procedures—saying the right words, completing the tasks—yields procedural verification. The 1857 revision accumulates grace through sustained faith, each recognition building on the last.

Our approach here serves to offer new evidence for adjudicating certain tensions in traditional scholarship. Bettelheim treats fairy tales as therapy for childhood anxieties. Propp counts thirty-one universal functions in traditional (Russian) folktales. Dégh and Dorson insist on cultural specificity. Each method captures something important, yet none can systematically compare emotional patterns across languages and centuries. Our sentiment analysis complicates Bettelheim’s therapeutic claims, since only some versions provide clear resolution. It challenges Propp’s universals, because the same functions generate different emotional intensities across cultures. And it extends anthropological work by showing how narrative forms travel while emotional-moral content transforms

When Noble (2018) demonstrates how algorithms encode oppression, she rightly calls out the dangers of flattening cultural difference into universal patterns. We try to avoid this pitfall as much as possible by retaining a human scholar at the center. George Box famously observed that all models are “wrong,” but some are “useful.” Our models are wrong in that they cannot capture every nuance of literary meaning. They are useful in surfacing patterns that are often invisible to traditional close reading. Recent work (Simons et al. 2025) confirms the use of LLMs to enhance, rather than replace, human interpretation. We present these patterns not as definitive truths but as starting points for further interpretation and reflection. In our four Cinderella stories, this includes the recognition scaffold structuring all versions, the different depths of loss each culture allows, and the varying cultural resolutions our emotional/moral “problem” seeks. It also includes the way these stories traverse the full emotional spectrum from −5 despair to +5 joy with a range that exceeds typical narrative bounds. These patterns suggest that what makes these tales travel may be both their emotional similarity in intensity—highlighting a familiar and universal ethical/emotional failure of recognition—but also their emotional adaptability, the way the “same” story can entail radically different cultural solutions while remaining recognizable.

3. Granular Shapes, Four Emotional Architectures

We turn now to the more granular shapes to investigate the particulars of each story shape starting with our earliest Chinese variant and ending with the final Grimm and Grimm (1857) version.

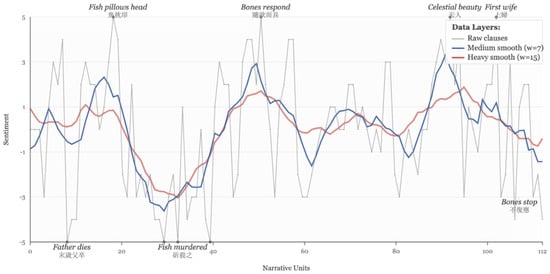

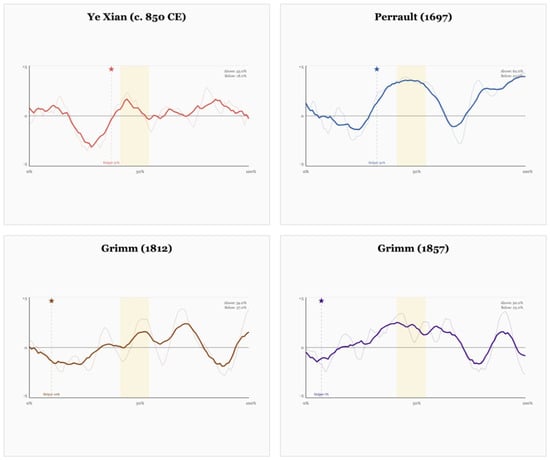

The story of Ye Xian, preserved in Duan Chengshi’s 9th-century Youyang Zazu (酉陽雜俎), creates what Elkins (2022) terms “storyteller curves,” a W-shape found in popular stories worldwide (Figure 1). Yet sentiment mapping of its 112 narrative clauses shows something more specific, namely an asymmetrical architecture where the first valley plunges far deeper than the second. The first valley system (units 1–40) contains −5 abysses of severed sacred bonds, while the second (units 50–100) never descends below −3 despite social violence and political torture.

Figure 1.

Ye Xian, c. BCE 800: Recognition Through Sacred Reciprocity. Ye Xian’s emotional architecture forms two unequal valleys with the first plunging deeper (−5) when sacred bonds break (father’s death, fish’s murder) than the second (−3) during social persecution. Peak moments (+5) mark recognition: the fish trusts Ye Xian enough to pillow its head on the bank, the bones grant wishes, she appears celestially beautiful at the festival, and she marries. Unlike Western happily-ever-after variants, Ye Xian ends in gradual decline when the bones stop responding. Raw data captures moment-to-moment volatility, moderate smoothing shows the double-valley structure, and heavy smoothing most approximates Vonnegut’s arc but misses the steep plunge of the depletion ending.

Our model also suggests an unexpected hierarchy of loss. The fish’s murder sustains a −5 valley for seven narrative units, while the father’s death creates only a brief spike. This disparity illuminates Tang dynasty values around reciprocal bonds (情 qíng). The father’s death uses 末 (mò), suggesting natural decline, but the fish’s death employs 斫 (zhuó), a violent hacking typically reserved for executions. The stepmother’s deliberate deception (wearing Ye Xian’s clothes) and subsequent desecration (hiding bones in dung) transform this from mere death into violated trust. Ye Xian’s daily acts of care, sharing her meager rice while the fish pillows its head trustingly on the bank, form a reciprocal sacred bond. Its destruction registers as more traumatic than natural human loss, forming a sustained valley.

The verb 枕 (“to pillow”) demonstrates voluntary vulnerability and often appears in Tang poetry in intimate contexts, for example in when 枕臂 (pillowing on a lover’s arm). The language of morality highlights that “此乃神魚” (this was a divine fish) who singles out Ye Xian, for “他人至不復出” (when others came, it wouldn’t emerge). The uniqueness of the relationship is captured in the term 情 (qíng), which suggests emotional reciprocity and connection between realms.

Wearing Ye Xian’s clothes to make the fish appear weaponizes this special relationship, thereby destroying the human-divine unity so valued in Daoist context. Concealing the bones in dung only deepens the desecration. Our story shape makes clear that this destruction registers more powerfully than later social violence. The king “禁錮而栲掠之” (imprisons and tortures) an innocent person later in the tale, but this event, while a valley, is not nearly as deep or sustained. Unlike in other variants, however, peaks remain equally high across different realms, whether for the appearance of the divine figure who reveals the bones’ power, for Ye Xian’s celestial appearance at the festival (the term 天人 refers to Buddhist devas whose beauty reflects spiritual merit), or for her marriage as first wife. This harmony across peaks is contrasted with the asymmetry of the valleys. This emotional architecture taps into a karmic-recognition ethics, a synthesis of Buddhist karmic connection (緣), Daoist natural response (應), and Confucian reciprocity (報). Moments of recognition, whether divine or regal, create a harmonious ethical balance. Destruction of a deep connection between the human and divine worlds, however, creates a deeper valley than severance of bonds between humans.

Units 103–112 show gradual decline rather than sustained elevation or dramatic plunge. While the king initially prays to the bones and is rewarded, his greed leads to eventual depletion: “逾年,不復應” (after a year, no longer responded). The final image, “一夕,為海潮所淪” (one night, lost to the sea tide), uses passive construction to emphasize powerlessness. The bones return to water, the element from which they came. This Tang dynasty Cinderella offers transformation through a deep interconnection with the sacredness of a natural being from a different realm, a recognition that transcends the more superficial trials and triumphs of the purely human social world. The tragedy of the decline may be that bonds like that between parent and child or self and the sacred natural world once severed can never fully be restored. Some losses are irreversible and even magical gifts return to their source. The ending reflects Buddhist belief that attachment—whether to family or enchanted fish—creates suffering. The stronger the bond, the greater the suffering upon inevitable loss. It also hints at a Daoist philosophy that believes extraction violates natural reciprocity. But also, perhaps, a more fateful view of the world in which all gifts, even divine, eventually disappear.

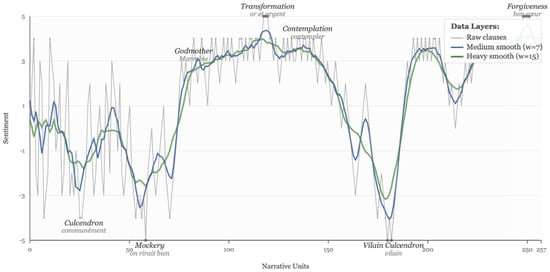

The sentiment graph of Perrault’s Cendrillon (Figure 2) demonstrates initial high levels of oscillation followed by curves on a hill (Elkins 2022). Peaks and valleys surface a thematic asymmetry between the registers of harm and remedy unremarked in current scholarship. Every valley in the narrative emerges from linguistic violence, while every peak marks a moment of material transformation or visual recognition. This pattern suggests a moral universe in which evil operates through language and good cannot answer in kind.

Figure 2.

Perrault’s (1697) Cendrillon: Linguistic Violence and Material Escape. Perrault’s Cendrillon reveals a disturbing asymmetry in which every valley stems from verbal cruelty (the vulgar nickname Culcendron, imagined mockery), while every peak comes from material transformation (golden dresses, glass slippers). Words wound but cannot heal, and even Cendrillon’s forgiveness at the story’s highest peak goes unanswered. The smooth ascent visible in heavy smoothing masks this fundamental imbalance between linguistic harm and material remedy.

The opening ten units oscillate between +4 and −4, establishing moral categories through language. The stepfamily is “hautaine et fière” generating valleys, while Cendrillon possesses “douceur et bonté sans exemple” creating peaks. Unlike Ye Xian’s −5 plunge when the father dies, Perrault eliminates death from the emotional architecture. The mother, “la meilleure personne du monde,” is already dead, though she persists through her transmission of virtue, which Cendrillon inherits from her (she “tenait cela de sa Mère”).

The first sustained valley (−4) occurs at unit 27 through naming (“ce qui faisait qu’on l’appelait communément dans le logis Culcendron”) and this naming which becomes “communal.” Difficult to translate, the name combines “cul” (ass) with “cendron” (cinder), creating what Philip Lewis (1996) calls “social death through naming.” The text presents naming before behavior. In other words, linguistic degradation creates the reality it describes. After the naming we learn that she “s’allait mettre au coin de la cheminée, et s’asseoir dans les cendres.” Does she sit in ashes because they call her Culcendron, or do they call her Culcendron because she sits in ashes? The naming comes first in the narrative sequence, suggesting linguistic violence shapes reality rather than describing it. In salon culture where reputation determined existence, this vulgar nickname performs social erasure, a −4 valley equal to physical harm in other variants.

The following valleys (−5) occur with speculative humiliation. At unit 60: “on rirait bien, si on voyait un Culcendron aller au bal.” The impersonal “on” universalizes the mockery. Unlike the social obstacles and real events of Ye Xian, here the story concerns the power of words and the conjuring of collective mockery. When Cendrillon responds “ce n’est pas là ce qu’il me faut,” she accepts the social judgment. The second −5 valley at unit 182 intensifies linguistic cruelty when a stepsister jokes she could never loan her dress, “Prêter mon habit à un vilain Culcendron comme cela!” “Vilain,” originally from the term for peasant, would have indicated low social class as well as physical and moral ugliness. The “comme cela” conjures a gesture that would have further accentuated the judgment—language performing degradation as speech act.

Unlike the verbal degradation of the valleys, every single peak aligns with material transformation or visual recognition. The fairy godmother appears “la voyant tout en pleurs.” Cendrillon’s own transformation occurs through “habits d’or et d’argent tout chamarrés de pierreries,” luxury objects rather than innate character or linguistic naming. In the story, the prince never speaks to Cendrillon. He “la mit à la place la plus honorable” (placed her), “ne lui donna que de ses mains” (gave with his hands) and her recognition happens through visual confirmation, represented in the verb “contempler,” often used for religious or artistic contemplation such that she is seen as a beautiful object rather than a subject.

Even the glass slipper sequence requires few words. When it fits “comme de cire” (like wax), this generates another peak defined by material visual confirmation rather than verbal exchange. The highest peak occurs not during recognition or marriage but when Cendrillon forgives (units 248–251): “Qu’elle leur pardonnait de bon cœur, et qu’elle les priait de l’aimer bien toujours.” Her speech meets silence—we never see the sisters apologize. Cendrillon alone attempts linguistic repair, quickly followed by material elevation since she “fit loger ses deux sœurs au palais.”

Marina Warner (1994) notes the importance of naming in salon culture, and the stepsisters understand that controlling someone’s name controls their social existence. To call someone “Culcendron” in a culture where language constructs identity erases her goodness. Good, conversely, cannot operate through language at all. Cendrillon’s douceur—combining sweetness, gentleness, and aristocratic refinement—does not help her. The fairy godmother offers material elevation; the prince offers placement and visual recognition, not speech. Even forgiveness goes unanswered.

The smooth hill shape visualizes an ascent through material elevation rather than recognition of interiority. Material peaks elevate Cendrillon not by renaming but by rendering her “inconnue”—nameless and therefore aligned with her outward reality. Perrault’s morals confirm that “bonne grâce” matters more than beauty, suggesting social performance exceeds natural qualities. The second confirms what the story teaches: without “parrains ou marraines,” virtue is useless. Both morals operate where materiality matters.

In Perrault’s court world, linguistic harm could be especially powerful. Gossip and naming could destroy position and reputation. Failed recognition links to an evil that constructs reality through linguistic performance, turning good to bad, beauty into villain. Good maintains virtue until material elevation and social performance allow escape. While seemingly the gentlest emotional arc without Ye Xian’s deep loss, this smooth surface belies a story where innate virtue alone cannot counter evil. Some degradation—even if only linguistic—can only be escaped, never answered, even in a world of happily-ever-after.

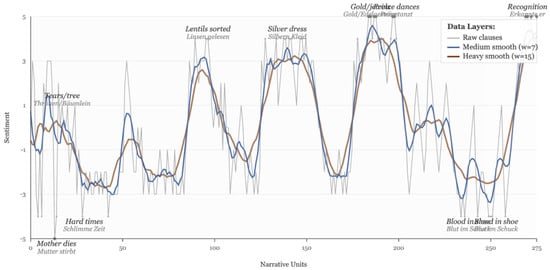

Our sentiment arc for Grimm and Grimm’s (1812) Aschenputtel (Figure 3) surfaces the repetitive structure that scholars have noted, a remnant of oral storytelling in which events happen in patterns. There are two lentil-sorting tasks, three invocations of the tree, and three trips to balls of increasing opulence. What this W-pattern makes clearer, however, are the constant variations in a story that, rather than evidence of the simplicity of Vonnegut’s curves, keeps an audience guessing with continual swings in a roller coaster of sentiment. Every elevation is followed by a return to degradation. Underlying this constant switchback is a gradual rise, however, a rags to riches over the course of reversals. A gradually ascending series of peaks (+3, then +4, then +4.5, then +5) is interrupted by a continual return to negative baselines (−2 to −3).

Figure 3.

Grimm and Grimm’s (1812) Aschenputtel: Triadic Ascension Through Productive Suffering. The 1812 Grimm version creates a distinctive W-pattern of constant reversals. Each triumph (completing impossible tasks, magical dresses) is followed by a return to degradation, yet peaks gradually ascend from +3 to +5. The break in folk pattern—only two tasks instead of the expected three—signals the stepmother’s violation of a cosmic order. Smoothing reveals how this roller-coaster serves both folk narrative (suffering earns magic) and Protestant theology (the elect must repeatedly return to dust).

Opening oscillations are not as extreme as in our earlier two examinations, in which we saw a stark confrontation between good and evil in a massive oscillation between positive and negative. Here, the opening valley in which the mother dies is immediately softened by the instructions she provides that prevent a sustained emotional nadir: “pflanz ein Bäumlein auf mein Grab, und wenn du etwas wünschest, schüttele daran, so sollst du es haben” (plant a little tree on my grave, and when you wish for something, shake it, so you shall have it). The German construction is fairly mechanical; “so sollst du es haben,” as though what softens the blow is not a continued spiritual connection, whether with a substitute enchanted fish or fairy “marraine,” but a series of rituals passed down by the mother that operate with folk reliability. Aschenputtel’s tears provide enough water for the tree, establishing what might be read as either folk reciprocity—tears for water, wishes for care—or what Jack Zipes (1988) calls Protestant economy.

The emotional architecture of curves maps to both these moral frameworks simultaneously. Two sorting tasks create identical valleys rising to +4 peaks through successful completion. At unit 71: “da hast du eine Schüssel voll Linsen, wann wir wieder kommen muß sie gelesen seyn” (there you have a bowl full of lentils, when we return they must be sorted). The second task doubles difficulty with two bowls within the same timeframe. Both tasks require separating good from bad, a task the stepfamily clearly cannot perform in recognizing Aschenputtel’s goodness. She must “lesen,” which means both reading and sorting, invoking both mechanical folktale action and Protestant theology. Peaks occur after task completion: “die schlechten ins Kröpfchen,/die guten ins Töpfchen” (the bad ones into the crop,/the good ones into the pot). The rhyming couplet, identified by Linda Dégh (1969) as work song mnemonic, has both ritual/incantatory folk element and mechanical suggestion. No one acknowledges Aschenputtel’s success either time.

Here the pattern breaks; there is no third task. Folk logic typically demands threes, but after two tasks the stepmother simply refuses: “du hast keine Kleider” (you have no clothes). This structural rupture is significant. In folk narratives, breaking the pattern of three signals the antagonist has violated cosmic order. The stepmother’s outright refusal marks her transgression against the rule of three. By refusing a third task, she breaks the contract in a world where even villains must play by rules. In breaking the pattern, the stepmother frees Aschenputtel from the obligation to prove herself through human trials. This works from a Protestant perspective too. When the stepmother abandons any pretense of fairness, this marks the limits of works-based salvation.

Aschenputtel’s connection to divine or natural beings operates through both folk incantation and Protestant process. She calls “Ihr zahmen Täubchen, ihr Turteltäubchen, alle Vöglein unter dem Himmel” (you tame doves, you turtle doves, all birds under heaven) invoking the threes once again. The birds respond to what might be read as either proper ritual summoning—Achenputtel knows the right words to call for assistance—or as a cosmic recognition of the elect. Either way, input and output, like the waves on our graph, seem predictable.

Three times Aschenputtel invokes the tree: “Bäumlein rüttel dich und schüttel dich,/wirf schöne Kleider herab für mich!” (Little tree shake yourself and quake yourself,/throw beautiful clothes down for me!). The reciprocal qíng of Ye Xian is replaced by a universe where beings are self-operating (“rüttel dich,” “schüttel dich”) through proper command with minimal reciprocity (tears for watering reciprocated by wishes granted). This represents either folk magic working through proper formulation—rhyming couplets creating power—or Protestant universe where divine provision operates mechanically upon human activation. Each invocation corresponds to one wedding night with ascending peaks, first silver (“silbern,” +4), then “noch viel prächtigern” (even more magnificent, +4.5), finally “ganz golden” (entirely golden, +5). Yet after each night, she must return to degradation.

The W-pattern persists with valleys indicating either folk narrative logic where magic provides aid but cannot prevent misfortune, or Protestant architecture where greater grace does not eliminate the need for humility. Peaks read differently through each lens, indicating either accumulating magical power through ritual repetition or ascending external proofs of grace. The gradual ascension—silver to magnificent to gold—suggests growing magical potency or progressive sanctification, but return to ashes remains mandatory.

One valley occurs when stepsisters self-mutilate to fit the shoe. The doves’ call raises alarm: “Blut im Schuck” (blood in the shoe), material evidence of fraud in attempting recognition at expense of bodily integrity. The prince’s recognition is procedural verification working in both folk and Protestant logic. The final +5 peak when the slipper fits Aschenputtel is distinct from Perrault’s glass slipper. The shoe is “angegossen” (cast on) as through metallurgy. Maximum sentiment occurs with double verification, confirming the perfect fit when the prince looks at her face. The “wieder” (again) of recognition suggests he had already known but required external proof. In this moral universe, internal recognition always requires external validation.

This variant of our Cinderella tale layers two systems of meaning. The broken pattern of tasks (two not three) versus fulfilled pattern of wedding nights (three as expected) reveals that when human authority violates folk law by abandoning the rule of three, it loses power. The magical/divine realm maintains patterns perfectly, by contrast. Good is located simultaneously in the ability to follow folk procedures and in a Protestant demonstration of election through works while maintaining faith. Evil assigns impossible tasks, refuses promised rewards, breaks cosmic order, and attempts to pass as elected through literal lack of self-integrity.

What likely makes this version so compelling is how it layers these two systems of meaning. The broken pattern of tasks (two not three) in contrast to the fulfilled pattern of the wedding nights (three as expected) suggests that when human authority violates folk law by abandoning the rule of three, it loses its power over the hero. The magical/divine realm, however, maintains its patterns perfectly. This asymmetry shows our asymmetric relationship with the universe, which is quite different from the Daoist harmony in the Ye Xian variant. In the Grimm and Grimm (1812) variant, legitimate cosmic order resides not in human tests but in magical/divine response. Good is simultaneously the ability to follow folk procedures exactly—plant trees with tears, speak formulae correctly, and complete impossible tasks through proper invocations—and the Protestant demonstration of election through works while maintaining faith through tests of humility. Evil lies in assigning impossible tasks, refusing promised rewards, breaking the “rules” of the cosmic order, and attempting to pass oneself off as elected through a quite literal lack of (self) integrity. A mandatory return to humiliation serves both this folk narrative necessity and Protestant theology. Aschenputtel must return to ashes—Aschenputtel means “little ash girl”—between each elevation. The story’s emotional architecture creates a narrative that satisfies both folk expectation of ritual efficacy and Protestant insistence that the elect must repeatedly return to dust, earning again and again what was already given.

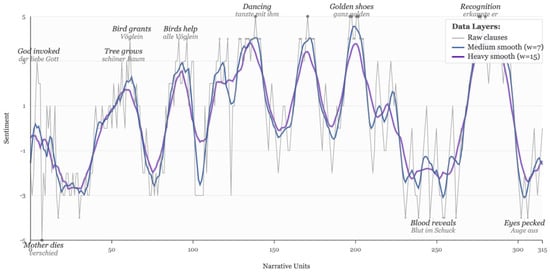

At first glance the 1857 revision seems minor (Figure 4). But key trends emerge, most notably gradually rising valleys and an emotional arc spending more time above neutral. Many valleys hover around neutral or dip slightly below—overall more positive valence. Where 1812 showed sharp peaks followed by immediate plunges, 1857 shows plateaus extending fifteen to twenty units at progressively higher elevations. Tatar (1987) documents smoothing of rough edges across seven editions, but this emotional architecture shows more. Instead of a steady peak-valley W shape, curves on a hill emerge like Perrault. An overall hill-plateau broken by storyteller curves keeps audience interest through valleys that gradually lessen, hovering closer to −1 midway through the narrative. Superimposed on lingering providential grace architecture, peaks and valleys ascend in lockstep suggesting traditional rags-to-riches triumph more than the earlier version.

Figure 4.

Grimm and Grimm’s (1812) Aschenputtel: Christianization and Divine Retribution. The 1857 revision shows gradually rising valleys and extended plateaus of elevation. Where 1812’s sharp peaks (+4) immediately plunged to degradation (−2 to −3), 1857 maintains elevation for 15–20 narrative units at progressively higher levels. The overall hill shape masks a sandwich structure: dark opening (mother’s death), bright middle (sustained grace), dark ending (stepsisters’ blinding). Heavy smoothing makes this look like Perrault’s aristocratic ascent, but the mechanisms differ: material transformation versus accumulated Protestant grace.

While the mother’s death forms the first and deepest valley, it’s softened before and after with the promise that “der liebe Gott wird dir schon helfen” (the dear God will surely help you). This creates an immediate +3 peak before the mother’s death. The mother still dies but language is softened (“verschied”) and situated in an emotional architecture of divine assurance. Suffering hasn’t decreased—the valley is equally deep—but even before entering this more forgiving emotional arc, indications suggest a gentler moral universe.

The hazel branch episode (units 40–62), newly introduced, offers something distinct. When the father asks “was soll ich dir mitbringen?” (what shall I bring you?), sentiment rises from neutral to +1. The stepsisters request “schöne Kleider” and “Perlen und Edelsteine” (beautiful clothes, pearls and precious stones), but Aschenputtel asks only for “das erste Reis, das Euch auf Eurem Heimweg an den Hut stößt” (the first branch that knocks against your hat on your way home). The branch that “chooses” the father demonstrates folk belief in meaningful accidents, with the natural world participating in destiny. Aschenputtel knows to ask for what will find him, not what he will find. She asks for something humble and seemingly worthless, exhibiting proper humility.

The sustained positive plateau (units 50–62) stems not from the branch itself but what happens: “welches sie auf das Grab ihrer Mutter pflanzte, und weinte so sehr, daß die Tränen darauf niederfielen und es begossen” (which she planted on her mother’s grave, and wept so much that the tears fell down upon it and watered it). The 1812 mechanical “genug” (enough) becomes “so sehr” (so much); these are tears of genuine grief rather than sufficient irrigation. Gone are mechanical processes, replaced by human grief, organic growth as the branch “ward ein schöner Baum” (became a beautiful tree).

Bottigheimer (1987) reads Aschenputtel’s prayer three times daily as increasing female passivity, but the description engages in traditional folk processes (note the three times) and sustained practice of devotion rewarded in ways invoking a folk-Protestant syncretism. These events and her active participation lead to ascending elevation. In answer to prayer “kam ein weißes Vöglein auf den Baum” (a white bird came to the tree), operating as both folk psychopomp connecting daughter to dead mother and possibly Holy Spirit mediating divine grace.

The sorting tasks remain but generate different sentiment patterns. Where 1812 showed −3 valleys rising to +4 peaks through completion, 1857 shows shallower valleys (−2) rising to higher peaks (+4 to +5). Completion is more miraculous with “alle Vöglein unter dem Himmel” (all birds under heaven). Where 1812’s Aschenputtel returned to ashes between balls, falling to −2, 1857 maintains elevation. She withdraws but does not degrade. Valleys between balls barely descend below neutral marking retreat rather than a true return to suffering.

This shift becomes clear when comparing language between versions. In 1812, after the first night, stepsisters come to the kitchen to torment: “waren sie böse, denn sie wollten es gern schelten” (they were angry, for they wanted to scold her). They taunt with details of dancing with the prince. When Aschenputtel reveals she watched from dovecote, “trieb sie der Neid und sie befahl, daß der Taubenstall gleich sollte niedergerissen werden” (envy drove her and she commanded that the dovecote should be torn down immediately). This linguistic cruelty and psychological games recall Perrault’s salon tradition.

By 1857, this French-influenced psychological cruelty vanishes. The text simply states: “lag Aschenputtel in seinen schmutzigen Kleidern in der Asche, und ein trübes Öllämpchen brannte im Schornstein” (Aschenputtel lay in her dirty clothes in the ashes, and a dim oil lamp burned in the chimney). After the second night: “lag Aschenputtel da in der Asche, wie sonst auch” (Aschenputtel lay there in the ashes, as usual). The phrase “wie sonst auch” is particularly telling; this is routine, not degradation. No taunting, no threats. The emotional language of the earlier version—”böse” (angry), “Neid” (envy), “betrübt” (sorrowful)—has been replaced with neutral descriptors of position and habit.

The tree invocations remain unchanged—”Bäumlein rüttel dich und schüttel dich”—but their context has transformed. In 1812, these are desperate appeals from degradation; in 1857, they’re strategic summonings from a position of hidden dignity. The white bird that appears in 1857 as intermediary between prayer and provision suggests divine response to supplication rather than folk magical incantation. Each dress escalates not just in beauty but in divine signification: “Gold und Silber” (gold and silver), then “noch viel stolzer” (even more splendid), finally “ganz golden” (entirely golden) with “Pantoffeln ganz von Gold” (slippers entirely of gold), invoking the gold in Christian iconography which signifies divine glory.

This evolution from 1812 to 1857 reveals the Grimms’ movement away from French literary influence and oral tradition’s emotional volatility toward Protestant emotional architecture. The 1812’s verbal cruelty and psychological games maintain peaks and valleys keeping audiences guessing—true to oral storytelling’s dramatic variation. The 1857’s ascending peaks and hill shape suggest once grace is received, it does not fully depart. Aschenputtel withdraws to avoid detection but retains essential dignity, hiding her election rather than losing it. No longer the folk economy of suffering-for-reward, this change reflects Protestant theology where the elect maintain their spiritual elevation even while outwardly returning to their humble station.

Blood revelation maintains −4 valleys, but the response changes. The 1812’s practical doves become explicitly moral agents: “Rucke di guck, rucke di guck!/Blut ist im Schuck:/Der Schuck ist zu klein,/die rechte Braut sitzt noch daheim” (Look back, look back!/Blood is in the shoe:/The shoe is too small,/the right bride still sits at home). Stepsisters aren’t just fraudulent but “falsche Braut” (false bride), in other words morally and physically false. Recognition transforms from mechanical verification to moral vindication. When the shoe fits, the prince “erkannte das schöne Mädchen, das mit ihm getanzt hatte” (recognized the beautiful girl who had danced with him), and the word “recognition” here indicates a deeper awareness than in the earlier version.

Sustained plateaus visualize what Protestant theology calls the perseverance of saints: once true grace begins, it accumulates rather than requiring constant re-earning. The stepsisters’ punishment complicates what in other variants is a more positive conclusion. Indeed, this version brings us closer to the kind of karmic punishment seen in the Ye Xian version. It is not enough to end with the recognition and marriage of Aschenputtel. Visible punishment of those who are not elected is also necessary.

Good in 1857 transforms into patient faith, while stepsisters become “falsch” in essence, deserving blindness that literalizes their refusal to recognize Aschenputtel’s goodness. The mountain range and last valley surface a different emotional-moral universe than 1812, one with confidence in election and punishment for those not elected. Revised for bourgeois family reading, patient suffering under providence leads inevitably upward while falsehood leads to divinely ordained darkness.

4. The Many Shapes of a Fairy Tale, and the Paradox of Moral Recognition

Do any of our Cinderella tales share Vonnegut’s Cinderella shape? Can we find something beyond the ATU core “DNA” that persists? And might that something explain why these stories have travelled so widely across time and space?

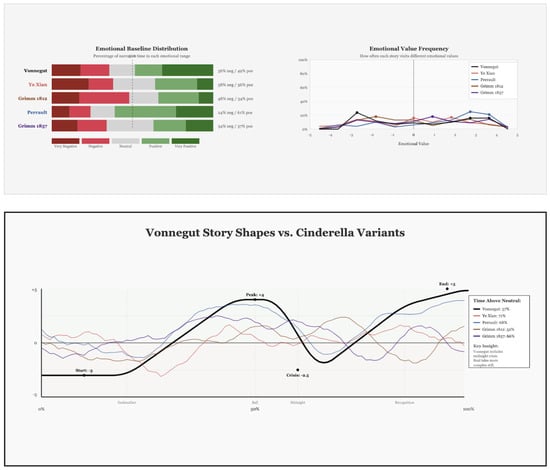

Having considered each story for its unique shape and moral-emotional architecture, we can now compare all four variants from a slightly more distant vantage point against Vonnegut’s backdrop (Figure 5). When normalized to equal lengths, all four Cinderella versions place transformation in the same general region. This element confirms some legitimacy for what Propp identified as a consistent narrative function. And yet, shared coordinates vary somewhat in their emotional content. For example, the “punishment of the villain” creates a deeper valley in Ye Xian than in the Grimm and Grimm (1857) variant, and the mother’s death forms a deeper valley in the Grimm variants than in Perrault. Linguistic cruelty is more crushing in Perrault than in Grimm. Identical functions, therefore, generate differing emotional architectures.

Figure 5.

Structural Convergence and Cultural Divergence: Four Cinderella Variants with Vonnegut Archtypes. Normalized sentiment analysis reveals structural convergence alongside culturally-specific emotional patterns. Transformation zones (gold bands, 41–54%) show remarkable consistency while helper appearances (★) vary dramatically:1 Grimm versions introduce magic early (7–10%), Ye Xian (37%) and Perrault (32%) delay supernatural aid. The emotional baseline reveals three distinct worldviews. Perrault maintains stable positivity (69% positive), Grimm and Grimm (1857) follows a dark-bright-dark sandwich pattern (negative opening, positive middle, negative ending, yet still 52% positive overall), while Ye Xian and Grimm and Grimm (1812) oscillate continuously (46–48% positive). Vonnegut’s curve (48% above neutral) smooths the granularity of individual tales into a rise-fall-rise arc. While narrative structure (especially transformation timing) appears universal from distance, the emotional experience points to distinct moral-emotional worlds ranging from fundamentally positive (Perrault), punctuated by violence (Grimm and Grimm 1857), or continuously unstable (Ye Xian/Grimm and Grimm (1812)).

The emotional baseline gives us further ways of distinguishing this emotional architecture. This baseline quantifies what proportion of language is positive versus negative in valence. This synchronic view complicates both Bettelheim’s therapeutic universalism and Zipes’s culturally-informed readings. Ye Xian and Grimm and Grimm (1812) spend roughly half their narrative time in negative emotional territory (48% and 54% respectively). Both oscillate continually between joy and suffering as almost equally likely states. By contrast, Perrault and Grimm and Grimm (1857) maintain positive baselines with only about a third of their time in the negative linguistic realm (35% and 38% respectively).

These values give an overall sense of how dark the tale is, but more granular examination surfaces further distinctions. While Perrault’s negativity arrives as brief shallow dips below neutral, Grimm and Grimm (1857) exhibits what we might call a sandwich structure where darkest elements confine themselves to the opening and ending. For Perrault, suffering may be a temporary deviation from norm, with relatively minor disruptions to an essentially comfortable existence. While Perrault smooths over suffering, the Grimm variant segregates it. Intense negativity frames the narrative, with bourgeois comfort offering respite between.

The 1857 Grimm revision achieves its comfortable form by removing linguistic cruelty that marked the 1812 version. Where 1812’s stepsisters came to taunt—”der Prinz, der allerschönste auf der Welt hat uns dazu geführt”—and destroyed the dovecote out of envy, 1857 simply states “lag Aschenputtel da in der Asche, wie sonst auch” (as usual). Not degradation but routine. By removing Perrault-influenced verbal torment, the Grimms ironically created something more like Perrault structurally: both versions ultimately prefer material/visual confirmation over verbal exchange. The shoe “angegossen” (cast on) provides the same kind of material proof as Perrault’s slipper fitting “comme de cire”—mechanical verification requiring no linguistic recognition. In stripping out what they saw as French contamination evident in verbal wit and salon cruelty, they accidentally created something structurally more like Perrault’s emotional architecture. Where 1812’s dramatic valleys and peaks maintained oral tradition’s emotional volatility, 1857’s shallower valleys create hill structure remarkably similar to Cendrillon’s maintained elevation.

The unexpected pairings that arise once we consider both similarities and differences in emotional architecture complicate the kind of geographic and temporal categories scholars often rely on to group variants. Greater emotional volatility in Ye Xian and Grimm and Grimm (1812) accompanies tales foregrounding greater female agency. While likely culturally-inflected, these differences also suggest divergent narrative engines. Volatile emotional landscapes create opportunities for female action that smooth narratives foreclose. The more positively-framed narratives require sustained passivity to maintain comfortable trajectories. Perrault’s Cendrillon never speaks to her prince but accepts her status and endures the name Culcendron without protest. The 1857 Grimm revision reduces Aschenputtel’s direct speech and highlights patient waiting. From a narratological perspective, when the story plunges from peak to valley, action may be required to reverse trajectory. When it maintains steady elevation, action would only disrupt a comfortable arc. This may explain Disney’s global dominance—Perrault-based smoothness demands less of an audience. French aristocratic salon and German Protestant revision create “comfortable” narratives of overall ascent, while Tang dynasty tale and German folk variant create fraught worlds of perpetual oscillation.

Similar oscillations alongside different narrative functions illuminate distinct moral universes. In both Grimm and Grimm (1812) and Ye Xian tales with wide oscillations, helper appearance varies dramatically, from 7% (Grimm versions) to 37% (Ye Xian). Early magical intervention in Grimm correlates with an oscillating worldview in which help is always latent in nature, awaiting activation through proper procedure. Delayed supernatural aid in Ye Xian aligns with Buddhist-Daoist philosophy requiring loss before transformation—the fish must die to become powerful bones. Perrault’s godmother at 32% represents optimal aristocratic timing: suffering sufficiently has been demonstrated to deserve intervention, but not so prolonged as to damage essential nobility. These aren’t random variations but precise calibrations of when salvation becomes possible in each moral universe.

Different structures bear on what we might term the “recognition duration” problem. Does recognition, once achieved, persist or must it be renewed? The tales provides specific evidence for both models. Ye Xian’s fish provides momentary recognition through a remarkable pillow gesture—“魚必露首枕岸” where the character 必 (always/must) indicates this happens daily, requiring renewal through feeding and care. When the fish dies, that specific recognition can never be recovered; bones provide magical aid but lack the intimacy of a living encounter. Grimm and Grimm (1812)’s recognition must be re-earned at each event. Aschenputtel rises to +4, returns to ashes at −2, rises again, falls again, and our arc depicts the repetitive labor of maintaining recognition. But Perrault’s transformation, once achieved through the godmother’s “coup de sa baguette,” persists through the ball (though limited by midnight’s contractual deadline), and Grimm and Grimm (1857)’s plateaus, once reached, sustain for fifteen to twenty narrative units even while Aschenputtel physically returns to ashes. Smooth versions treat recognition as a state to be achieved; volatile versions treat it as practice requiring constant renewal. Perrault’s emotional arc yields further insight in a highest peak that is not recognition but moment of forgiveness—”Qu’elle leur pardonnait de bon cœur,” suggesting the greatest good for aristocratic culture is transcending need for recognition altogether.

Endings show the most dramatic departures from Vonnegut’s “happily-ever-after.” These story shapes surface philosophical differences in worldview about the nature of spiritual or magical resources. Ye Xian’s bones eventually “不復應” (stop responding) when king’s “貪求” (greedy seeking) destroys reciprocality (qíng) of original connection. The passive construction “一夕,為海潮所淪” emphasizes powerlessness as bones return to sea. This creates what we might call a depletion architecture, a gradual decline from +3 to +1 to 0 over the final ten units. Grimm versions operate as accumulation models even as the 1857 version ends negatively. The 1812’s W-pattern shows gradually ascending peaks (+4, then +4.5, then +5) even as valleys persist between them. While grace must be constantly re-earned, it accumulates toward final verification. The 1857’s mountain range makes accumulation visible as sustained plateaus of increasing height. What begins with a father’s minimal recognition (asking what gift she wants) builds through natural response (tree growing from tears) to divine assistance (white bird providing clothes) to moral vindication (recognition as “die rechte Braut”). Each level of recognition sustains rather than replaces the previous one. Depletion architectures prepare readers for a world where even magical gifts are impermanent, relationships require constant maintenance, and extraction exhausts the sacred. Accumulation shapes prepare readers for worlds where patient suffering builds toward triumph, proper procedures always yield results, and divine providence ensures good ultimately wins out.

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest fairy tales persist not through universal meanings (contra Bettelheim) or consistent ideological functions (contra Zipes) but as emotional technologies making us feel our way toward morality. Emotional amplitude and moral language of good and evil go hand in hand. This fairy tale’s strength lies in providing an architecture flexible enough to hold incompatible moral worlds while maintaining enough stability to remain recognizable. These stories offer us emotional occasions in which each culture builds its unique sense of justice from an emotional architecture paired with unique resolution to a well-known problem. These emotional occasions are narrative moments of maximum affective intensity where cultural values crystallize. In the valley when Ye Xian’s fish is murdered or when Cendrillon forgives, we see emotion and morality fuse, suggesting (though never teaching in the way that Perrault’s explicit morals teach) what generates the deepest grief and highest joy in these moral universes. They provide affective coordinates where provisional, culturally specific, yet somehow mutually recognizable moralities can emerge through the ups and downs of narrative tension.

Similar shapes can conceal different moralities, just as plateau/hill architecture serves both French aristocratic and German Protestant ideologies. Both moralities reflect emotional architectures suggesting the truly noble (Perrault) or the elect (Grimm and Grimm 1857) need not return to deep degradation. Despite different value systems, this shape itself becomes a bourgeois form reappearing in well-known tales like Dickens’s Great Expectations (Elkins 2022). Pip’s trajectory in Great Expectations follows similar sustained elevation through material transformation, only to confront moral reckoning in the final act. The bourgeois novel inherits and expands these fairy tale shapes into extended psychological exploration.

Unlike Perrault’s ending, however, the Grimm and Grimm (1857) version operates using a dual moral system that allows both grace for the elect and punishment rather than forgiveness for the wicked. Aschenputtel’s trajectory follows accumulated grace, each recognition building on the previous, creating sustained elevation even when she returns to ashes. She maintains spiritual dignity even in her “graues Kittelchen.” The stepsisters’ trajectory, however, which is visible in the graph’s final valleys, operates under entirely different rules. When the doves peck out their eyes for “Bosheit und Falschheit,” they’re experiencing what Protestant theology distinguishes as law versus grace. Under the law, transgression leads to punishment even as Aschenputtel’s divine favor accumulates. This moral framework would have been familiar to the Grimms’ Protestant audience.

Emotion and morality are inseparable in these tales, which is why we should understand them as emotional-moral technologies rather than simply narrative entertainments. These technologies teach through a language of sentiment, coupling emotion with acts of goodness and evil. Ye Xian operates through reciprocal ethics where extraction exhausts the sacred. Perrault tells of aristocratic salvation where powerful connections and material transformation counter linguistic degradation. Grimm and Grimm (1812) offers a dual system where folk incantation and Protestant procedure both yield results. The 1857 revision provides parallel moral physics where the elect rise through providence while the false fall under law with different rules for different characters.

These tales have emotional hold across wide audiences because many feel strongly about the possibility of virtue going unrecognized. What travels across cultures is the emotional experience of moral disarray with narrative finding a resolution—however impermanent—for moral restoration. Emotional-moral architectures give a glimpse of how a particular culture feels about justice and more broadly, how good and evil function as part of a larger worldview. Does misfortune occur with startling regularity, or is it a minor deviation from a predominantly happy life? Does goodness require acts to steer out of misfortune, or is its presence powerful enough to ward away evil? Is goodness and its recognition a gradual progression toward a happy ending or a momentary event in life bookended with sorrow? These tales persist as necessary emotional-moral technologies precisely because they’re incompatible, each preparing readers for different worlds where good and evil operate through different mechanisms. In each, justice follows different laws, and in each recognition works through different logic.

The apparent contradiction in our findings of certain structural similarities alongside incompatible emotional-moral architectures suggests something fundamental about how stories travel across cultures. What persists is not Vonnegut’s universal shape except on the most abstracted of levels. Rather, it’s a narrative predicament so powerful that every culture must imagine its own emotional resolution. The shapes of Cinderella are plural, not singular, and their very incompatibility proves the stability of the underlying problem. Virtue unrecognized creates narrative pressure that demands resolution, even when those resolutions lead down many different forking paths, each leading to its own unique version of the tale.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available at: https://github.com/KatherineElkins/humanities-the-shapes-of-cinderella, accessed on 4 October 2025.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this study, the author used models to generate sentiment scores along with justifications (see Appendix A for more details). Each model was tasked with evaluating the other models’ outputs with critique. The author adjudicated in instances of disagreement. Claude 4 was used to create visualizations and for proofreading. I would also like to thank Jon Chun, who helped me develop many of the initial methodological frameworks that make this work possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Traditional humanists may be surprised to learn that surfacing emotional arc is still somewhat of an art form in spite of the quantitative methods. Leaving aside the range of methods for performing the sentiment scoring (of which one can find ample discussion elsewhere), relevant for our explanation here are the many choices involved at every stage of the process. Critical to our methodology is the careful selection of hyperparameters at each analytical step. Text segmentation length, window size for smoothing, sentiment scale granularity, and normalization choices all shape the patterns that emerge. Rather than eliding over these decisions, we foreground them as interpretive choices.

Window sizes were chosen in order to demonstrate details at a level of granularity as well compare overall shape. One method of validation is crux point extraction and analysis. The interpreter must ask how well the peaks and valleys capture key moments of the narrative. If well, then the choices are likely good ones. Still, the different smoothing levels (i.e., different distances from which to view the story shapes) offer different insights, which is why we chose multiple distances here and offer both individual shape analysis and comparative analysis, the latter performed using normalization to 100 units. None are “correct,” and each serves different analytical purposes. This multiplicity of approaches directly counters any slide toward scientism by acknowledging that even our technical choices are interpretive acts.

Clause-by-clause analysis was chosen because it allows for better context-informed scoring than single words. Sentences, moreover, cause problems when moving between languages. The English translation of the French breaks some of the lengthier sentences into many; in other words, different languages have a different “tolerance” for sentence length, and this variation would significantly affect outcomes were scores determined on the sentence level. Chinese characters also lack the same sentence structure as our other target languages. For these reasons, clause-by-clause segmentations seemed the best compromise for our particular task.

While others have opted for simple moving averages, we opted for a smoothing method that does a better job at eliminating noise while still capturing peaks and valleys. We also opted for a wide range of sentiment scores—from −5 to +5—which we believe allows us to capture more nuanced differentiation in emotional tenor both within stories over time and between variants. While traditional sentiment analysis was developed using lexicons or statistical machine learning classifiers, here we employed three large language models for sentiment scoring and compared results. We further validated scores line by line—a method not often used for computational methods but made relatively easy given how short our tales are. Grok 3, Claude 4, and Claude 4.1 Opus were prompted to provide clause-by-clause sentiment analysis on a scale from −5 (maximum negative) to +5 (maximum positive) with careful attention to the original language and a justification for scoring. When models disagreed—typically by no more than 1 point—human adjudication resolved discrepancies based on contextual and cultural understanding.

Savitzky-Golay polynomial smoothing at multiple window sizes surfaced different levels of narrative structure. Minimal smoothing preserves emotional volatility and moment-to-moment shifts; moderate smoothing shows narrative patterns while maintaining key peaks and valleys; heavy smoothing approaches Vonnegut’s generalized story shapes. To handle edge effects (where we lose precision due to less data), we experimented with reflection padding and polynomial extrapolation. We chose reflection as it best preserved the emotional boundaries of opening and closing sequences.

We hear a lot about LLM biases, especially when it comes to preserving historical and cultural accuracy. These are very real problems. However we found our LLM models performed fairly well with the French, German and Tang Dynasty Chinese. In fact, we were surprised at just how well they processed the resonance of words from different time periods, for example with “villain,” which has lost some of its negative valence in modern usage but which the models were careful to restore. Grok 3 performed better than Claude 4, but Claude 4.1 performed better than either of these models. Because it is difficult to ensure that on any given try the model will be the same (not all LLM updates are publicized so a single model name can refer to multiple variants) we did not quantify performance metrics. We offer our comparisons in case they are useful, but not because we believe them to offer statistical rigor.

Still, we acknowledge ongoing debates about LLM capabilities for historical and cultural analysis. Critics rightly point out risks of hallucination and training data biases. Our approach mitigates these concerns in several ways: (1) we work with high-resource languages (French, German, Classical Chinese) where training data is robust; (2) we validate model outputs through comparison across different LLMs; (3) we perform line-by-line human adjudication of all sentiment scores; and (4) we treat models as interpretive tools requiring expert oversight rather than autonomous arbiters. We found models performed surprisingly well with historical language variants (e.g., correctly contextualizing “vilain” in 17th-century French salon culture), though we cannot claim they achieve perfect cultural understanding. Our results should be understood as human-AI collaboration rather than purely algorithmic output.

Because the languages we are working with are “high resource” languages, we find that the specificity of the original is able to surface patterns that are likely lost in translation. We tested models against key words like Perrault’s douceur, which carries aristocratic connotations beyond simple “sweetness,” and the Grimm brothers’ use of fromm to indicate Protestant piety rather than modern religiosity. Classical Chinese presented unique challenges, but the models still successfully distinguished between different uses of “死” (death) based on context—the father’s death generating different sentiment than references to the stepfamily’s cosmic punishment. Whereas we typically think of sentiment analysis as not involving “interpretation”—remaining at the surface of language rather than ascribing context-dependent values—we need to be more careful when using LLMs. It appears that when working clause-by-clause, they do infer some of the cultural and historical valences that both make our readings more precise but also take us away from the more “objective” surface reading that many of us are familiar with. While no computational method can capture every nuance of literary meaning, we believe the combination of multiple models, human oversight, and attention to cultural context provides robust patterns for analysis. Still, we offer these results as preliminary and welcome other specialists to offer feedback and critique. While we do not anticipate major disagreements in sentiment scoring, scholars may well find slight disagreement.

Note

| 1 | In fact, the question of the introduction of “Helper” in Ye Xian is a bit more complicated than this simple asterisk indicates. While the helper could be seen as the divine figure who directs Ye Xian to the bones, one could equally consider the enchanted fish as helper—occurring much earlier in the narrative and in a much more similar narrative function role—even though it only takes on the helper role when in the form of wish-granting bones. |

References

- Bacchilega, Cristina. 1997. Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim, Bruno. 1976. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. New York: Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B. 1987. Grimms’ Bad Girls and Bold Boys: The Moral and Social Vision of the Tales. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Angela. 1979. The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories. London: Gollancz. [Google Scholar]

- Da, Nan Z. 2019. The Computational Case Against Computational Literary Studies. Critical Inquiry 45: 601–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, Francisco Vaz. 2002. Metamorphosis: The Dynamics of Symbolism in European Fairy Tales. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, Sara Graça, and Jamshid J. Tehrani. 2016. Comparative Phylogenetic Analyses Uncover the Ancient Roots of Indo-European Folktales. Royal Society Open Science 3: 150645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dégh, Linda. 1969. Folktales and Society: Story-Telling in a Hungarian Peasant Community. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, James E. 2019. Critical Digital Humanities: The Search for a Methodology. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duan Chengshi. c. 850 CE. Youyang Zazu [Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang]. Wikisource. Available online: https://zh.wikisource.org/wiki/酉阳杂俎/续集/卷一 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Dundes, Alan, ed. 1982. Cinderella: A Casebook. New York: Garland Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dundes, Alan. 2007. The Moral of the Story: Folklore’s Function in Society. In The Meaning of Folklore: The Analytical Essays of Alan Dundes. Edited by Simon J. Bronner. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, pp. 176–94. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, Katherine. 2022. The Shapes of Stories: Sentiment Analysis for Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, Katherine. 2024. In Search of a Translator: Using AI to Evaluate What’s Lost in Translation. Frontiers in Computer Science 6: 1444021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, Pauline, and Sidney Eve Matrix. 2010. Fairy Tale Films: Visions of Ambiguity. Logan: Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, Jacob, and Wilhelm Grimm. 1812. Kinder- und Hausmärchen, 1st ed. Berlin: Realschulbuchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, Jacob, and Wilhelm Grimm. 1857. Kinder- und Hausmärchen, 7th ed. Göttingen: Dieterich. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, Donald, ed. 2004. Fairy Tales and Feminism: New Approaches. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Philip E. 1996. Seeing Through the Mother Goose Tales: Visual Turns in the Writings of Charles Perrault. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perrault, Charles. 1697. Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passé. Paris: Claude Barbin. [Google Scholar]