Heavens of Knowledge: The Order of Sciences in Dante’s Convivio

Abstract

| Felices animae, quibus haec cognoscere primis |

| Inque domus superas scandere cura fuit! |

| (Ovid)1 |

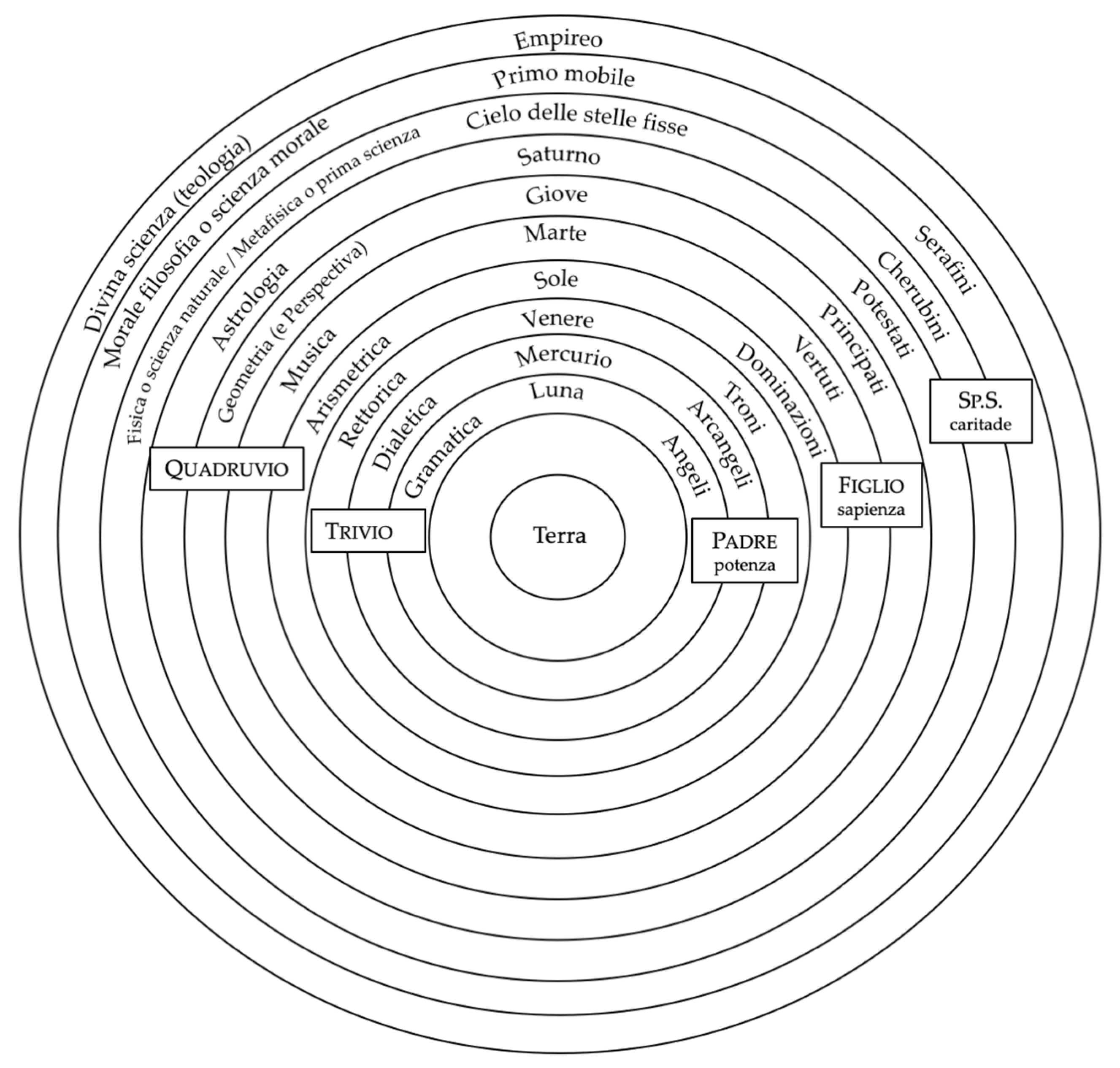

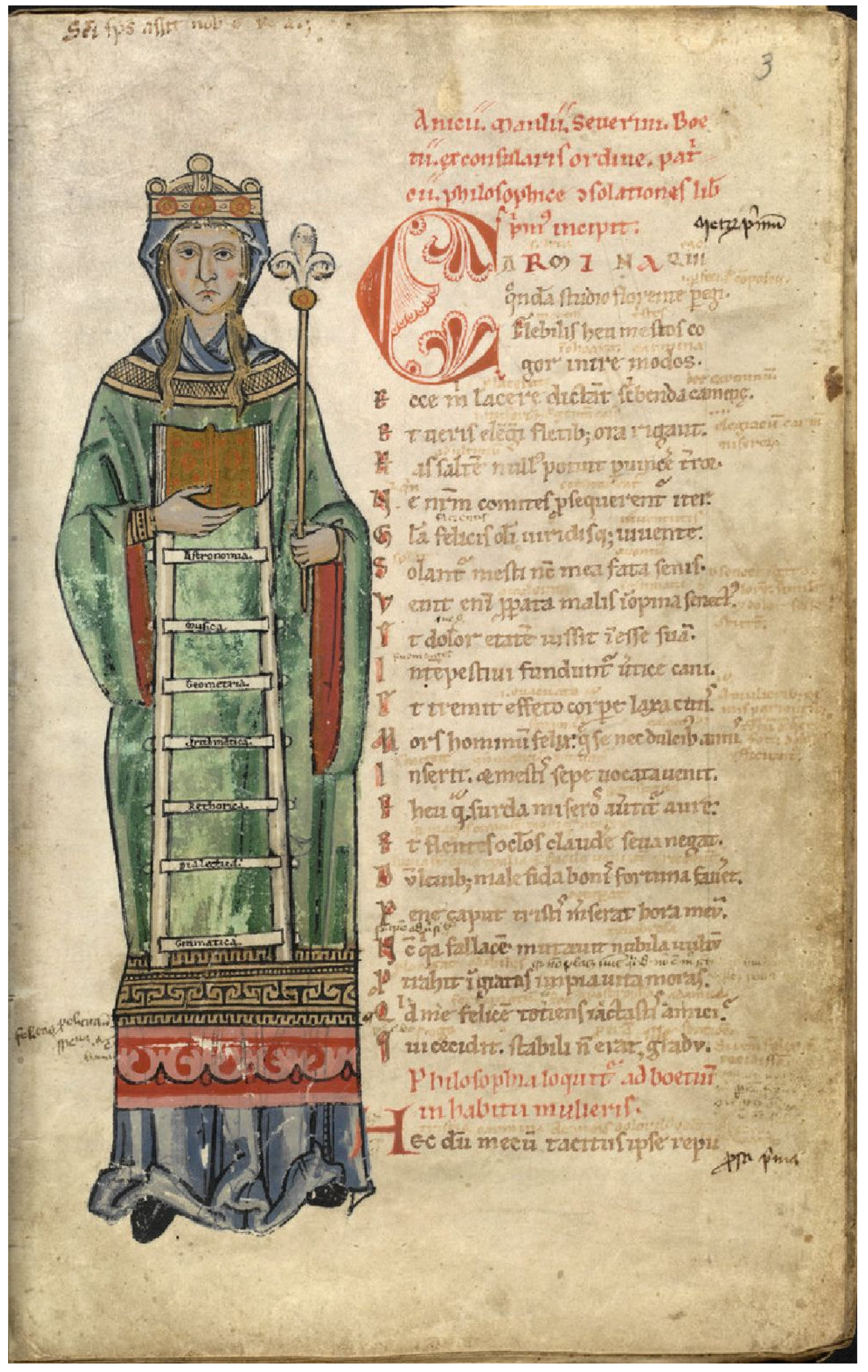

1. A Visual Hypothesis

[…] intelligere non est sine fantasmate. Accidit enim eadem passio intellectui que quidem et in describendo: ibi enim nulla utentes quantitate trigoni determinata, tamen finitam secundum quantitatem describimus; et intelligens similiter, etsi non intelligat quantum, ponitur ante oculos quantum, intelligit autem non secundum quod quantum est.(De mem. et rem. I, 449b–450a)6

“… se ’l vuoi poter pensare,dentro raccolto, imagina Siòncon questo monte in su la terra staresì che … vedrai come etc.se l’intelletto tuo ben chiaro vada”.“Certo, maestro mio”, diss’io, “unquanconon vid’i’ chiaro sì com’or discerno”.(Purg. 4, 67–77; my emphasis)

Imaginando adunque, per meglio vedere, [che] in questo luogo ch’io dissi sia una cittade e abbia nome Maria; dico ancora che se dall’altro polo, cioè meridionale, cadesse una pietra, ch’ella caderebbe in su quel dosso del mare Occeano ch’è a punto in questa palla opposito a Maria. … E qui[vi] imaginiamo un’altra cittade, che abbia nome Lucia. … Imaginisi anco uno cerchio in su questa palla … Segnati questi tre luoghi sopra questa palla, leggiermente si può vedere come lo sole la gira etc.(Conv. III, v, 10–13; my emphasis)

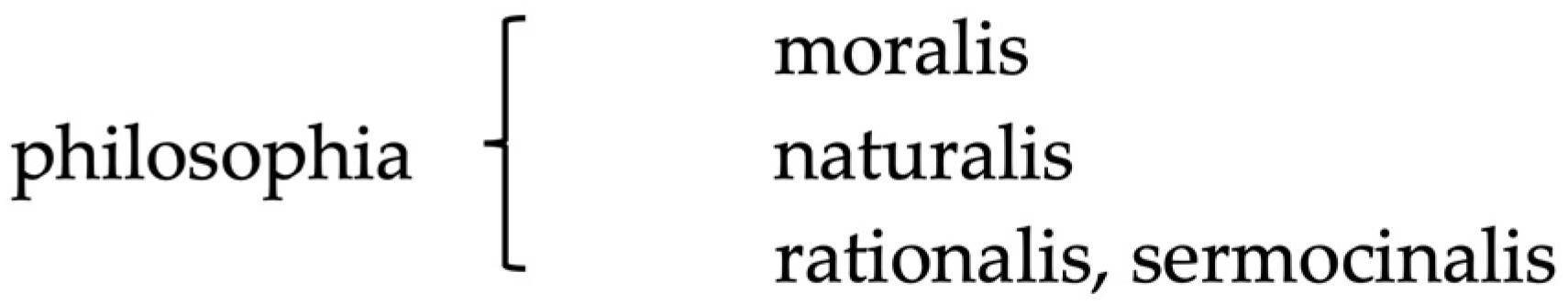

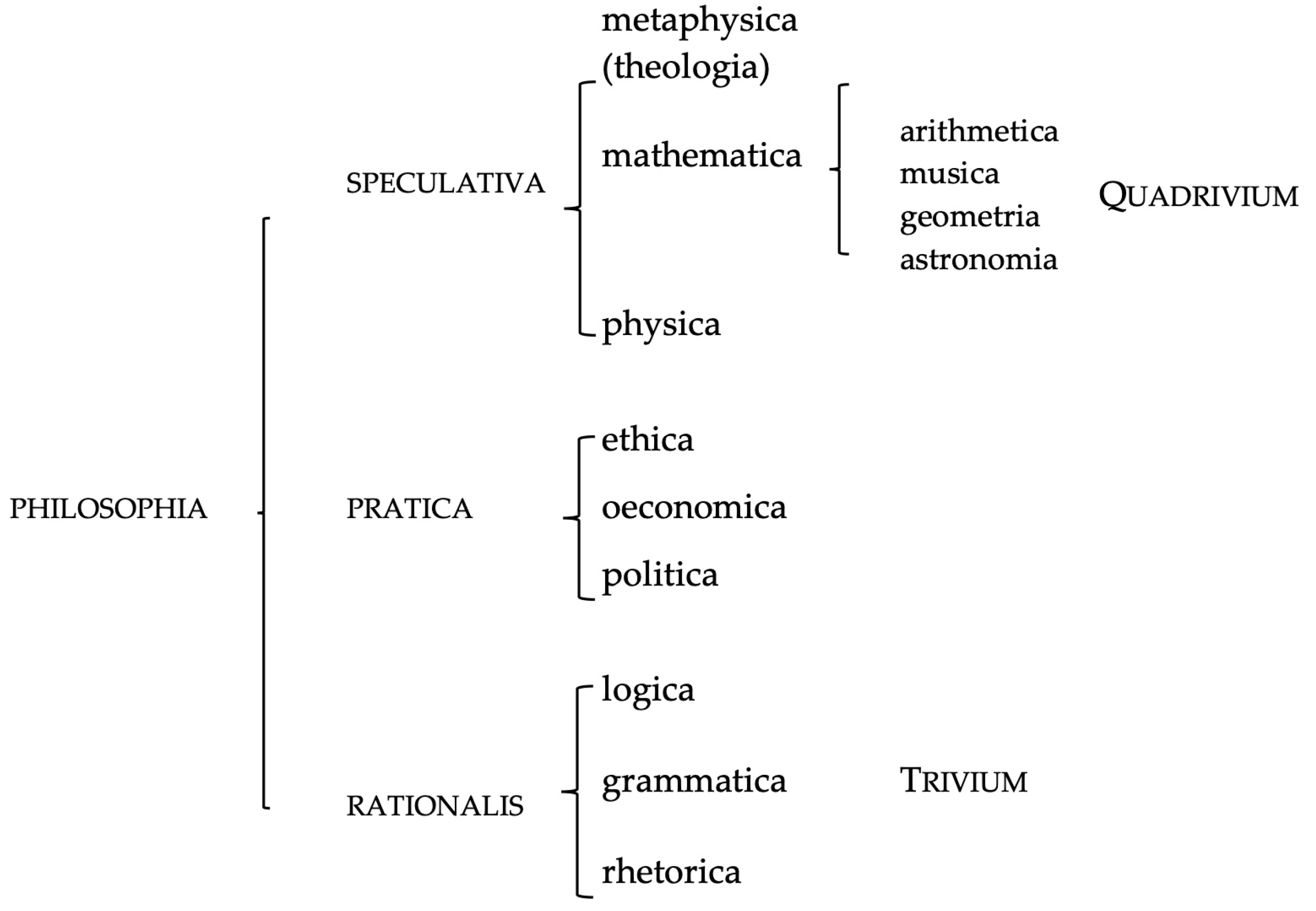

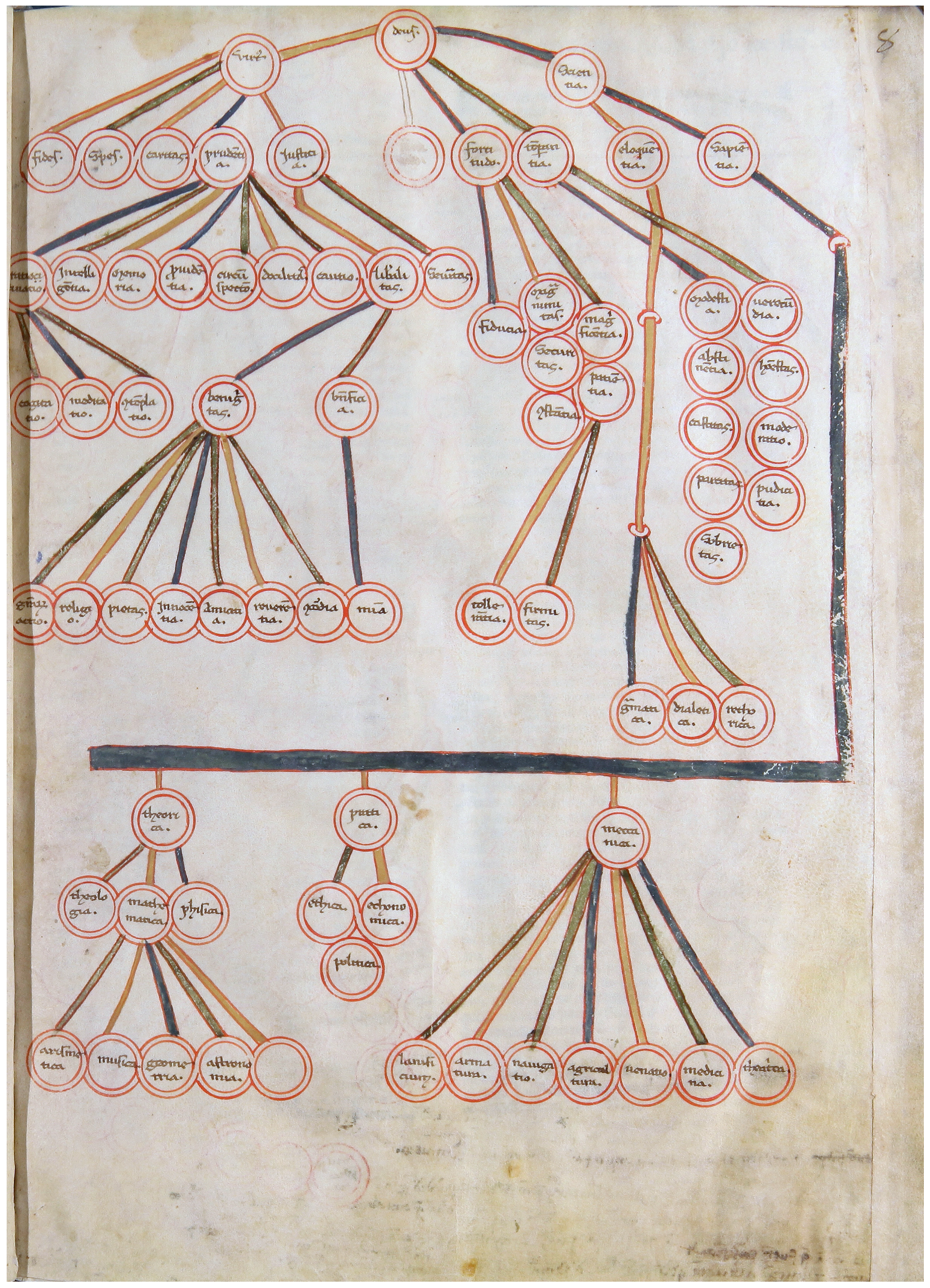

2. The Medieval Tradition of the divisio scientiae

3. The divisiones scientiae in Dante’s Florence

3.1. Santa Maria Novella

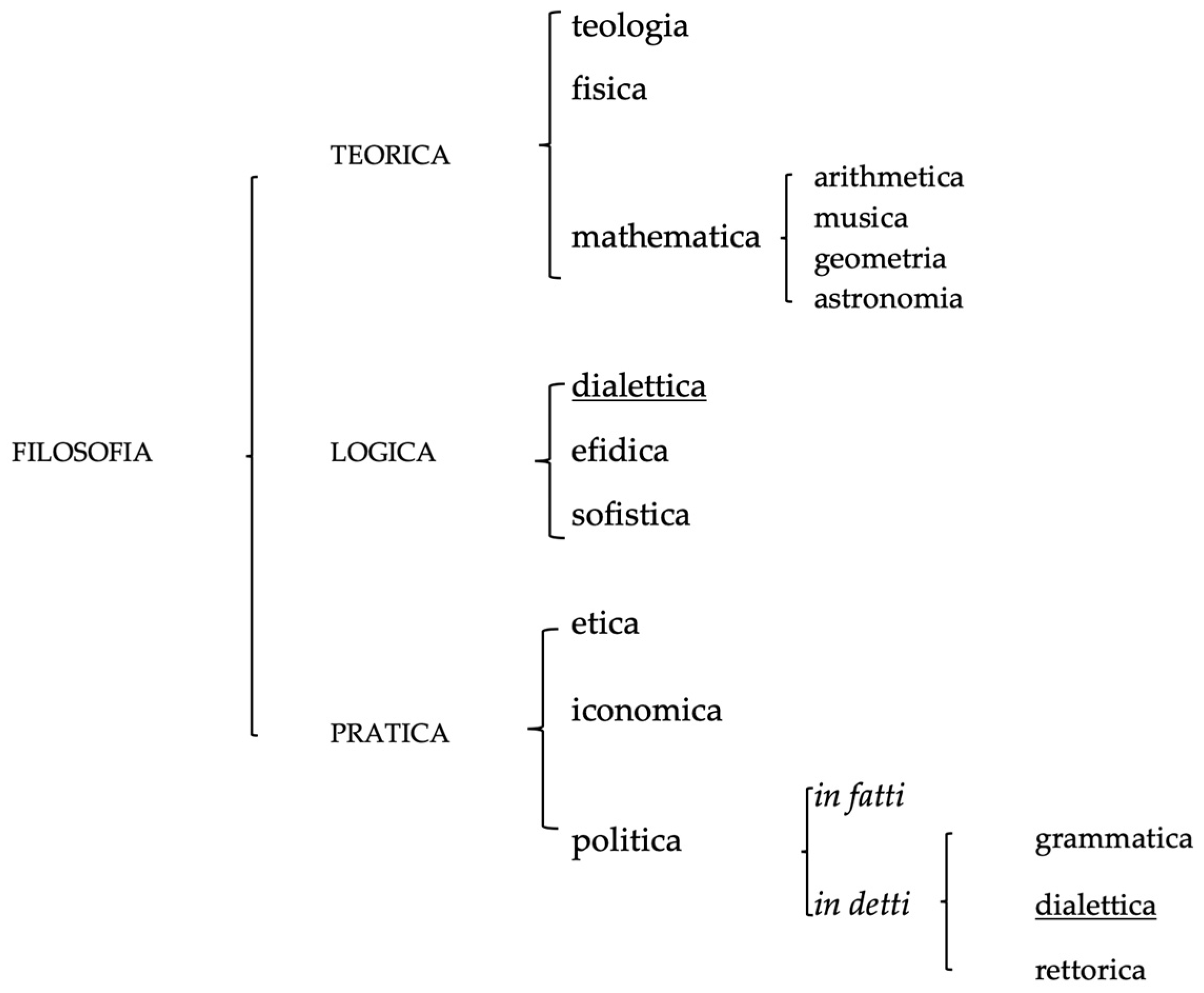

3.2. Brunetto Latini (and Santa Croce)

pensando che lla scienza delle cittadi è parte d’un altro generale che muove di filosofia, sì vuole elli dire un poco che è filosofia, per provare la nobilitade e l’altezza della scienza di covernare le cittadi. Et provedendo ciò ssi pruova l’altezza di rettorica.(Rett. V, 17, 5, in Latini [1912] 1968, p. 29)

4. The Liberal Arts and the Heavens

Artes scripture sunt 7 causa planetarum 7 que sic eis attribuuntur: gramatica lune, dialetica mercurio, rhetorica veneri, arismetica soli, musica marti, astronomia jovi, et geometria saturno. Qui vero subtiliter discusserit naturam et speculationem tam artium quam planetarum, et gentium qui ipsas adiscunt […] omnino inveniet dictas artes planetis rationabiliter attributas.(München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Clm 10268, f. 29v)41

E anco saranno sette arti liberali e non più, sì che ciascheduno planeto avarà la sua: la più vile, come la gramatica, sarà de rascione del più vile planeto, com’è la luna, e la dialetica sarà de Mercurio, e Venere avarà la musica, e così ciascheduno avrà la sua.(La composizione del mondo, II.viii, 6, Restoro d’Arezzo 1976)

5. Cosmic Knowledge: Dante and the System of Sciences

5.1. Divine and Human Science

5.2. Heavens of Knowledge

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Ovid, Fasti I 297–8. This quotation features in the Preface to the Latin translation of the Almagest made in twelfth–century Sicily (Haskins 1960, p. 192). |

| 2 | As Theodore Cachey puts it, ‘he really only needed to explicate the heaven of Venus’s relation to rhetoric and to the angelic hierarchy and of thrones for his immediate rhetorical and interpretive purposes’ (Cachey 2018, p. 73). The Convivio is always quoted from (Alighieri 2014). |

| 3 | Thomas Ricklin provides a recapitulatory summary including heavens, sciences, and authorities, and excluding the angelic hierarchies and the Trinity. According to him, a comprehensive reading of chapters from the twelfth onwards suggests that the authorities corresponding to rhetoric are Boethius and Cicero, who influenced Dante towards philosophy (Ricklin 2002, pp. 132–33; see also Brunetti 2022). |

| 4 | The definition of diagrams has been a subject of ongoing discussion. In recent times, Jean–Claude Schmitt has effectively elucidated three fundamental characteristics of diagrams: the capacity to establish analogical relationships between different elements; the constitutive interaction between graphic elements and verbal text; pragmatic and demonstrative efficacy (Schmitt 2018, 2019, pp. 28–29). |

| 5 | This representation is influenced by the illustrative and exegetical tradition of Boethius Consolation of Philosophy (Courcelle 1967, pp. 79–80). |

| 6 | Aristotle is quoted from the Aristoteles Latinus Database. |

| 7 | William of Conches well defines the role of geographic diagrams (figurae) as a summarizing visual tool, in comparison with more detailed maps: ‘si vero qualiter ascendat et descendat scire desideras, et que nomina ex quibus regionibus contrahat, mappam mundi considera, sed quia facilius animo colliguntur quae oculis subiiciuntur, ideo id quod diximus in visibili figura depingamus’ (Dial. de subst. phys., in Guilelmus de Conchis (1567, pp. 197–98)). |

| 8 | A fundamental component of Platonic epistemology is the idea of a correspondence between degrees of being and levels of abstraction: ‘the more abstract the knowledge, the more immaterial and perfect the being’ (Weisheipl 1978, p. 464). Such a tenet determined the pre-eminence of mathematical sciences. |

| 9 | ‘Philosophiae tres partes esse dixerunt et maximi et plurimi auctores: moralem, naturalem, rationalem. Prima componit animum; secunda rerum naturam scrutatur; tertia proprietates verborum exigit et structuram et argumentationes, ne pro vero falsa subrepant’ (Ep. ad Luc. 89, 9). |

| 10 | In Latin it is possible to find also the terms ‘inspectiva’ and ‘actualis’, for instance in Isidorus, Etym. II 24, 9, or Papias Elementarium doctrinae rudimentum. |

| 11 | ‘[…] tres erunt philosophie theorice: mathematica, physica, theologia […] et honorabilissimam scientiam oportet circa honorabilissimum genus esse. […] si est aliqua substantia immobilis, hec prior et philosophia prima, et universalis sic quia prima; et de ente in quantum ens huius utique erit speculari, et que est et que insunt in quantum ens’ (Metaph. VI, 1, 1026a). |

| 12 | Bernardus reads the latus Euboicae rupis in Aen. VI, 42 as the cliff of philosophical disciplines, which divide into theory and practice. Also, the golden bough in Aen. VI is seen as philosophy, divided into practica and theorica. Subdivisions are peculiar: practice divides into solitaria, privata, and communis; theory into theology, mathematics, and physics (Bernardo Silvestre 2008, pp. 112–15, 144–47; the first passage is quoted also in Barański 2020b, pp. 157–58). |

| 13 | The circulation of the Consolatio in Tuscany has been mapped by Black and Pomaro (2000); see also Brunetti (2002, 2005). For the influence of William’s commentary on Dante see (Giunta 2010; Giunta in Alighieri 2014, pp. 384–409; Bianchi 2013, pp. 335–55; Lombardo 2013, pp. 136; 2018). A relevant contribution has been provided by (Nasti 2016). In commenting Cons. Ph. I. m. 2, Nicholas Trevet elaborates his divisio according to the Aristotelian bipartite model: practical philosophy is preparatory to contemplation, which leads to felicitas (Trevet n.d.). |

| 14 | In other cases the steps can symbolize the virtues or the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit (Courcelle 1967, pp. 77–79). |

| 15 | Notably, the term ‘quadrivium’ is first employed by Boethius. |

| 16 | Did. II, 1 in Hugo de Sancto Victore (1939): ‘Philosophia dividitur in theoricam, practicam, mechanicam et logicam. hae quattuor omnem continent scientiam. theorica interpretatur speculativa; practica, activa, quam alio nomine ethicam, id est, moralem dicunt, eo quod mores in bona actione consistant; mechanica, adulterina, quia circa humana opera versatur; logica, sermocinalis, quia de vocibus tractat. theorica dividitur in theologiam, mathematicam et physicam’. A similar divisio is articulated by the Franciscan friar John Gil of Zamora at the beginning of his grammatical treatise Prosodion, a copy of which arrived very early in Santa Croce, at the end of the thirteenth century: ‘De divisione scientiarum sermocinalis rationalis et doctrinalis necnon et magyce artis et mechanice’ (MS Laur. Plut. 25 sin. 4, f. 44r; see Pegoretti 2017, pp. 31–32; 2022, pp. 25–40). |

| 17 | ‘licet enim aliqui sufficienter videantur ipsam divisisse, fortassis tamen in aliquo defecerunt nec multum habilem ad recitandum ipsam divisionem fecerunt propter multorum insertionem’ (Div. sc. 1, in Panella 1981). Already Adelard of Bath’s Tractatus de philosophia develops four different divisions, as well as the anonymous Tractatus in the manuscript Paris, Bibliothèque national de France, lat. 6750, ff. 57v–59v (Dahan 1982). |

| 18 | A German translation with a commentary and an apparatus of further textual variants has been published in 2007 (Gundissalinus 2007), based on Ludwig Baur’s 1903 critical edition. About Gundissalinus, al–Fārābi, Hugh of Saint Victor, and their definitions of philosophy see (Imbach 2003, pp. 29–48). |

| 19 | For the rationale of this classification, possibly based on Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics see (Bottin in al–Fārābi 2013, pp. 33–38). |

| 20 | According to Ruedi Imbach, Gundissalinus’ divisio laid the groundwork to a curriculum of studies that unfolded only around 1250 (Imbach 2003, pp. 34–36). |

| 21 | Less useful Maierù (1995, pp.160–63). |

| 22 | ‘Communiter dividitur philosophia in septem artes liberales […] his primum erudiebantur, qui philosophiam discere volebant, et ideo distinguuntur in trivium et quadrivium. […] Et hoc etiam consonat verbis Philosophi qui dicit in II Metaphysicae quod modus scientiae debet quaeri ante scientias; […] post logicam consequenter debet mathematica addisci, ad quam pertinet quadrivium; et ita his quasi quibusdam viis praeparatur animus ad alias philosophicas disciplinas’ (Super Boetium De Trinitate, q. 5, a. 1; quotation from http://www.corpusthomisticum.org (accessed on 21 January 2024)). |

| 23 | ‘Ad eloquentiam enim pertinent omnes, quae recte vel ornate loqui docent, ut grammatica, poetica, rhetorica et leges humanae’ (Gundissalinus 1903, p. 5). Gundissalinus also discusses at length the status of logic, which he considers both a preliminary instrument and a science, to be learned after the scientia litteralis (grammar) e the scientiae civiles (poetics, with historia, and rhetoric). |

| 24 | ‘me quidem diu cogitantem ratio ipsa in hanc potissimum sententiam ducit, ut existimem sapientiam sine eloquentia parum prodesse civitatibus, eloquentiam vero sine sapientia nimium obesse plerumque, prodesse numquam’ (Cicerone, De inventione I, 1). |

| 25 | ‘Scientiae sunt duae species: sapientia et eloquentia. Et est sapientia vera cognitio rerum. Eloquentia est scientia proferendi cognita ornatu verborum et sententiarum. Et dicuntur species scientiae, quia in istis duobus est scientia omnis: in cognoscendo res et ornate proferendo cognita. Eloquentiae tres sunt partes: grammatica, dialectica, rethorica. Sapientia et philosophia idem sunt. Unde potest dici quod eloquentia nec aliqua pars eius de philosophia est. Quod auctoritate Tullii potest probari qui in prologo Rethoricorum dicit: “Sapientia sine eloquentia prodest, sed parum; eloquentia sine sapientia non tantum non prodest, sed etiam nocet. Eloquentia cum sapientia prodest”’ (Glosae super Boetium, ad Cons. ph. I pr. 1, p. 35; Guilelmus de Conchis 1999). |

| 26 | ‘Honesta autem sciencia alia est divina, alia humana. Divina sciencia dicitur, que deo auctore hominibus tradita esse cognoscitur, ut vetus testamentum et novum. Unde in veteri testamento ubique legitur: “locutus est Dominus” et in novo: ”dixit Ihesus discipulis suis”. Humana vero sciencia appellatur, que humanis racionibus adinventa esse probatur ut omnes artes que liberales dicuntur. Quarum alie ad eloquenciam, alie ad sapienciam pertinere noscuntur’ (Gundissalinus 1903, p. 5). |

| 27 | Remigio himself provides a problematic terminus ante quem when he alludes to the fact that Aristotle’s Economics had not yet been translated: ‘dicitur ychonomica grece, latine vero dispensativa, de qua determinat Aristotiles in libro Ychonomicorum, qui nondum habetur in patulo apud Latinos translatus’ (Div. sc. 14). The history of the translation of the Economics is quite troubling (Panella 1981, pp. 59–61). |

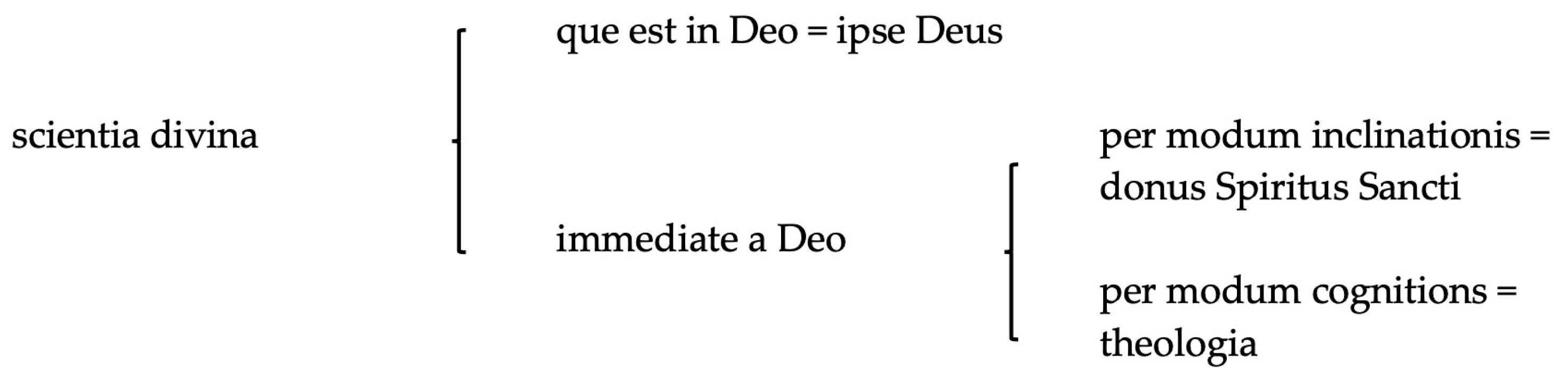

| 28 | Div. sc. 2: ‘Dicendum est igitur quod scientia, prima sui divisione, dividitur in scientiam divinam et in scientiam humanam. Scientia quidem divina dicitur quam Deus invenit […]. Scientia vero humana dicitur quam homo invenit, iuxta illud II Elenchorum: ‘Omne quod quis novit discens vel inveniens novit’. Circa primam scientiam, idest divinam, considerandum est quod dupliciter accipi potest. Uno modo dicitur scientia divina scientia que est in Deo, que quidem est idem quod ipse Deus […]. Secundo modo dicitur scientia divina scientia illa que est immediate a Deo. Dixi autem ‘immediate’ quia, mediate accipiendo, etiam omnis scientia humana est a Deo […]’. |

| 29 | Div. sc. 2: ‘Hec igitur scientia que est immediate a Deo duplicitur dicitur, quia dupliciter potest certitudinem habere. Uno modo per modum inclinationis, ad modum virtutis moralis, que quidem ‘est certior et melior omni arte quemadmodum et natura’, ut dicit Philosophus in II Ethycorum. Et hec scientia divina est unum de septem donis Spiritus sancti […]. Secundo modo potest habere certitudinem, per modum cognitionis, quemadmodum Philosophus loquitur de scientia in libro II Posteriorum diffiniens eam et dicens quod est habitus conclusionum, et in I Posteriorum dicens quod ‘demonstratio est sillogismus faciens scire’, idest aggenerans scientiam. Et sic in comuni usu loquimur de scientiis. Et hec scientia divina talem certitudinem habens et procul dubio ens super omnes alias scientias, est sacra scriptura que theologia vocatur’. On the equivalence of theology, the Bible, and its exegesis see (Dahan 2008, pp. 93–94). |

| 30 | This table partially replicates the comprehensive one devised by Emilio Panella, very useful to understand Remigio’s extremely complex divisio (Panella 1981, Table 1). |

| 31 | The menorah represents the three orders of the faithfuls (coniugatorum, continentium, prelatorum). |

| 32 | On this manuscript, see also https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc69719k (accessed on 9 July 2024). |

| 33 | The same concept is reiterated in Peter Lombard’s Sentences (III, d. 33, 1.2: ‘iustitia est in subveniendo miseris’). |

| 34 | In the two texts, Brunetto gives two different canonical definitions of philosophy. Rett. 6 (p. 41): ‘Filosofia è quella sovrana cosa la quale comprende sotto sé tutte le scienze’. Tresor I, 2, 1: ‘Philosophie est veraiz encerchement des choses naturels et des divines et [des] humanes, tant come a home est possible de entendre’. |

| 35 | Also in the Ars rethorice the trivium features under the civilis scientia, but not within a global theory of science (Alessio 1979, 148–49; Beltrami 1993, p. 119). |

| 36 | Even though the term ‘epidictica’ is relatively rare in Latin texts, Uguccione of Pisa devotes an entry explaining it as ‘demonstrativa scientia philosophorum’ (Dahan 1985, pp. 149–50). |

| 37 | With the exception of the absence of trivium and of the division of politics into words and deeds, also the Liber de philosophia Salomonis articulates a divisio scientiae analogous to the one offered by Brunetto. Here, Greek terms are paired by their Latin counterparts: disputatoria, demonstrativa, fraudolenta or ficta (Dahan 1985, pp. 148, 152, 162). That dialectics is the science bene disputandi is an Augustinian concept supported by many, including John of Salisbury, Metalogicon II, 4. |

| 38 | On the relationship between ethics, theology and metaphysics in Paris see (Lines 2002, 65 ff.). |

| 39 | ‘Sicut igitur mundum illuminant septem planetae, sic omnem scientiam ornant et muniunt artes ingenua [i.e., liberales]. Luna terris est citima, cui comparatur grammatica, primos vendicans limites. Sol, secundum quorundam assignationem, secundum locum tenet, cui consimilem in multis studiosus lector reperiet dialecticam. Mercurio tertium locum tenenti confertur rhetorica. Venus gratiosa est aspectu, cui arismetica [sic], ob multam hujus disciplinae venustatem, comparatur. Hujus utilitatem novit theologia, mysterium numerorum diligenter investigans. Martem respicit musica, non humana, non mundana, sed instrumentalis. Lituorum namque et tubarum clangentium concentus varius invitat armatos ad conflictum. Jovi se obnoxiam esse fatetur geometria, quae circa immobilem magnitudinem versatur. Saturno, astris vicinior planetis caeteris, militat astronomia, quae circa mobilem magnitudinem versatur’ (De nat. rerum, II, cliii [De septem artibus], in Neckam ([1863] 1967, pp. 283–84)). |

| 40 | In the same passage, Francesco offers a pairing between planets and the tasks that King ‘Asser’ distributes among his seven children in order to share the administration of his kingdom. The resulting list is peculiar, beginning with agriculture and consultations with subjects, and moving forward with eloquence, tasks involving music, geometry and the reading of celestial signs. |

| 41 | Not 129v, as indicated in (Brunetti 2022, p. 643). |

| 42 | On Boncompagno see now (Tomazzoli 2023, pp. 100–6). |

| 43 | Puzzled reactions in (Foster 1978), and (Gilson [1939] 2016, pp. 108–15). For the reference to faith and Revelation see the commentary by Fioravanti (in Alighieri 2014), ad Conv. II, xiv, 19–20, and (Barański 2020a). |

| 44 | Here the complete quotation: ‘lo Cielo empireo per la sua pace simiglia la divina scienza, che piena è di tutta pace: la quale non soffera lite alcuna d’oppinioni o di sofistici argomenti, per la eccellentissima certezza del suo subietto, lo quale è Dio. E di questa dice esso alli suoi discepoli: ‘La pace mia do a voi, la pace mia lascio a voi’ [Io 14,27], dando e lasciando a loro la sua dottrina, che è questa scienza di cu’ io parlo.’ (Conv. II, xiv, 19). The quotation of the Gospel of John refers to the Last Supper and to Jesus’s announcement of the coming of the Holy Spirit, who will clarify his teachings. |

| 45 | This interpretation, which is commonly shared as regards the Commedia, has been recently extended to the Convivio (Fioravanti 2011; Pegoretti 2018). |

| 46 | Well before his divisio, Dante had already reminded us that ‘li numeri, li ordini, le gerarzie narrano li cieli mobili, che sono nove, e lo decimo annunzia essa unitade e stabilitade di Dio. E però dice lo Salmista: “Li cieli narrano la gloria di Dio, e l’opere delle sue mani annunzia lo firmamento”’ (Conv. II, v, 13). Interestingly enough, in commenting the Psalms 88 Augustine compares the heavens to the apostles (Enarr. in Ps. 88, sermo 1, 3). This analogy evolved over the centuries to include saints, viri spirituales, and preachers, and crystallized in Peter Lombard’s commentary on the same Ps. 18 quoted by Dante: ‘Coeli enarrant, [Aug.] id est apostoli’. This interpretation looks like particularly relevant in light of the translatio of the prophetic charisma from the prophets to apostles, preachers, and ultimately to Dante, as elucidated by Nicolò Maldina (Maldina 2017). |

| 47 | Gilson ineffectively distinguished between metaphysics in Book III as pertaining to the divine mind (i.e., the divine science as we defined it), and metaphysics ‘pour nous’ (in Book II), which is defective and subject to ethics (Gilson [1939] 2016, 106 ff.). Nardi rejected this interpretation (Nardi 1944, pp. 209–45). In Conv. III, iii, Dante recalls the distinction between divine and human philosophy, and declares that he will deal exclusively with the latter. According to Luca Bianchi, this is an ‘uncommon and unstudied distinction’, which ‘recalls but does not coincide with the standard distinction between scientia divina and scientia humana’ (Bianchi 2022, p. 353, fn 72) |

| 48 | Interesting considerations also in (Barański 2020a, p. 66). |

| 49 | Since Augustine, the quadrivium is found in various combinations. As for the trivium, while grammar consistently occupied the first place, dialectics and rhetoric were interchangeable. Bibliography on the tradition of the liberal arts is very extensive: see at least (I. Hadot 2005; Kimball 2010, sections II–III). In Dante scholarship, see (Di Scipio and Scaglione 1988). |

| 50 | See also Claudio Giunta in his commentary to Voi che ‘ntendendo: ‘l’originalità di Dante non risiede tanto nelle idee che professa quanto nella capacità che lui solo ha, tra gli scrittori del suo tempo, di mettere in rapporto questa cosmologia con gli avvenimenti più significativi della sua vita privata, e di leggere questi sullo sfondo di quella’ (in Alighieri 2014, p. 196). |

| 51 | More persuasively, Theodore Cachey enlists amongst the most intriguing inquiries the question ‘where there exists any connection between the elaborate analogy of the heavens and the sciences and the angelic hierarchy […] and the structure of the poem’ (Cachey 2018, p. 59; my emphasis). |

| 52 | See (I. Hadot 2005, pp. 137–55). Notably, Alexander Neckam wrote a commentary on the De nuptiis (O’Donnell 1969). |

| 53 | Alongside (Mazzotta 1993) see (Antonelli et al. 2003). |

References

- Albi, Veronica. 2021. Sotto il manto delle favole. La ricezione di Fulgenzio nelle opere di Dante e negli antichi commenti alla Commedia. Ravenna: Longo. [Google Scholar]

- Alessio, Gian Carlo. 1979. Brunetto Latini e Cicerone (e i dittatori). Italia Medioevale e Umanistica 22: 123–69. [Google Scholar]

- Alessio, Gian Carlo. 2001. Sul De ortu scientiarum di Robert Kilwardby. In La divisione della filosofia e le sue ragioni. Lettura di testi medievali (VI–XIII secolo). Atti del Settimo Convegno della S.I.S.P.M. (Assisi, 14–15 novembre 1997). Edited by Giulio d’Onofrio. Cava dei Tirreni: Avagliano Editore, pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- al-Fārābi, Abu-Nasr Muhammad Ibn-Muhammad. 2005. Gerardus Cremonensis. In Über die Wissenschaften: Nach der lateinischen Übersetzung Gerhards von Cremona. Lateinisch–deutsch = De scientiis. Edited by Franz Schupp. Philosophische Bibliothek, 568. Hamburg: Felix Meier. [Google Scholar]

- al-Fārābi, Abu-Nasr Muhammad Ibn-Muhammad. 2013. La Classificazione delle Scienze. Introduction by Francesco Bottin. Edited by Anna Pozzobon. Padova: Il Poligrafo. [Google Scholar]

- Alighieri, Dante. 1996. Das Gastmahl. Edited by Francis Cheneval, Ruedi Imbach and Thomas Ricklin. Philosophische Bibliothek, 466a–b–c–d. Hamburg: Meiner. [Google Scholar]

- Alighieri, Dante. 2014. Convivio. Commentary by Gianfranco Fioravanti, canzoni edited by Claudio Giunta. In Dante Alighieri. 2014. Opere, II. Convivio, Monarchia, Epistole, Egloghe. Director Marco Santagata. Milan: Mondadori, pp. 5–805. [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli, Roberto, Paolo Canettieri, and Arianna Punzi. 2003. L’”Enkyklios paideia” in Dante. In Studi sul canone letterario del Trecento. Per Michelangelo Picone. Edited by Johannes Bartuschat and Luciano Rossi. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Arcoleo, Santo. 1969. Filosofia ed arti nell’Anticlaudianus di Alano di Lilla. In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Âge. Montréal and Paris: Institut d’études médiévales-Vrin, pp. 569–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ascoli, Albert Russell. 2008. Dante and the Making of a Modern Author. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augustinus Hipponensis. 1955. De ciuitate Dei. Edited by Bernard Dombart and Alphonse Kalb. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, 47–48; Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Barański, Zygmunt G. 2020a. Dante and Doctrine (and Theology). In Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio: Literature, Doctrine, Reality. Cambridge: Legenda–Modern Humanities Research Association, pp. 45–81. [Google Scholar]

- Barański, Zygmunt G. 2020b. ‘Reflecting’ on the Divine and on the Human: Paradiso XXII. In Dante, Petrarch, Boccaccio: Literature, Doctrine, Reality. Cambridge: Legenda–Modern Humanities Research Association, pp. 135–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bartuschat, Johannes. 2015. La “filosofia” di Brunetto Latini e il Convivio. In Il Convivio di Dante. Atti del Convegno di Zurigo (21–22 maggio 2012). Edited by Johannes Bartuschat and Andrea A. Robiglio. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrami, Pietro G. 1993. Tre schede sul Tresor. Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere 23: 115–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo Silvestre. 2008. Commento all’‘Eneide’. Libri 1–6. Edited by Bruno Basile. Roma: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Luca, ed. 1997. La filosofia nelle università: Secoli XIII–XIV. Scandicci (Firenze): La Nuova Italia. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Luca. 2013. ‘Noli comedere panem philosophorum inutiliter’. Dante Alighieri and John of Jandun on Philosophical “Bread”. Tijdschrift voor Filosofie 75: 335–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Luca. 2022. Philosophy and the ‘Other Works’. In Dante’s “Other Works”: Assessments and Interpretations. Edited by Zygmunt G. Barański and Theodore J. Cachey, Jr. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 333–62. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Robert D., and Gabriella Pomaro. 2000. ‘La consolazione della filosofia nel Medioevo’ e nel Rinascimento italiano: Libri di scuola e glosse nei manoscritti fiorentini = Boethius’s ‘Consolation of Philosophy’ in Italian Medieval and Renaissance Education: Schoolbooks and their Glosses in Florentine Manuscripts. Biblioteche e archivi, 7. Florence: SISMEL–Edizioni del Galluzzo. [Google Scholar]

- Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. 2005. De Consolatione Philosophiae. Opuscula Theologica. Edited by Claudio Moreschini. München and Leipzig: De Gruyter–K.G. Saur. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, Giuseppina. 2002. Guinizzelli, il non più oscuro Maestro Giandino e il Boezio di Dante. In Intorno a Guido Guinizzelli. Atti della Giornata di studi (Universita di Zurigo, 16 giugno 2000). Edited by Luciano Rossi and Sara Alloatti Boller. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 155–91. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, Giuseppina. 2005. Preliminari all’edizione del volgarizzamento della Consolatio philosophiae di Boezio attribuito al maestro Giandino da Carmignano. In Studi sui Volgarizzamenti Italiani due–Trecenteschi. Edited by Paolo Rinoldi and Gabriella Ronchi. Rome: Viella, pp. 9–45. [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti, Giuseppina. 2022. Dante e la retorica. In La biblioteca di Dante (Roma, 7–9 ottobre 2021). Atti dei Convegni Lincei, 345. Rome: Bardi Edizioni, pp. 633–49. [Google Scholar]

- Cachey, Theodore J., Jr. 2018. ‘Alcuna cosa di tanto nodo disnodare’: Cosmological Questions between the Convivio and the Commedia. In Dante’s Convivio: Or How to Restar a Career in Exile. Edited by Franziska Meier. Oxford and Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cheneval, Francis. 1998. Dante Alighieri: Convivio. In Interpretationen. Hauptwerke der Philosophie. Mittelalter. Stuttgart: Reclam, pp. 353–80. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, Rita, and Ineke Sluiter. 2009. Medieval Grammar and Rhetoric: Language Arts and Literary Theory, AD 300–1475. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle, Pierre. 1967. La ‘Consolation de Philosophie’ dans la tradition littéraire. Antécédants et postérité de Boèce. Paris: Etudes Augustiniennes. [Google Scholar]

- d’Onofrio, Giulio. 2001. La philosophiae divisio di Severino Boezio, tra essere e conoscere. In La divisione della filosofia e le sue ragioni. Lettura di testi medievali (VI–XIII secolo). Atti del Settimo Convegno della S.I.S.P.M. (Assisi, 14–15 novembre 1997). Edited by Giulio d’Onofrio. Cava dei Tirreni: Avagliano editore, pp. 11–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Gilbert. 1982. Une introduction à la philosophie au XIIe siècle. Le Tractatus quidam de philosophia et partibus eius. Archives d’Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge 49: 155–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Gilbert. 1985. Origène et Jean Cassien dans un Liber de philosophia Salomonis. Archives d’Histoire Doctrinale et Littéraire du Moyen Âge 52: 135–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Gilbert. 1992. Elements philosophiques dans l’Elementarium de Papias. In From Athens to Chartres: Neoplatonism and Medieval Thought: Studies in Honour of Edouard Jeauneau. Edited by Haijo Jan Westra. Leiden: Brill, pp. 225–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Gilbert. 1994. La classificazione delle scienze e l’insegnamento universitario nel XIII secolo. In Le università dell’Europa: Le scuole e i maestri. Il Medioevo. Edited by Jacques Verger and Gian Paolo Brizzi. Milano: Silvana Editoriale, pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dahan, Gilbert. 2008. L’exégèse chrétienne de la Bible en Occident médiéval (XIIe–XIVe siècle). Paris: Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Delhaye, Philippe. 1969. La place des arts libéraux dans les programmes scolaires du XIIIe siècle. In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Âge. Montréal and Paris: Institut d’études médiévales-Vrin, pp. 161–73. [Google Scholar]

- Di Scipio, Giuseppe C., and Aldo D. Scaglione, eds. 1988. The ‘Divine Comedy’ and the Encyclopedia of Arts and Sciences: Acta of the International Dante Symposium, 13–16 November 1983, Hunter College, New York. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: J. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, Bruce S. 2007. Ordering the Heavens: Roman Astronomy and Cosmology in the Carolingian Renaissance. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Egidi, Francesco. 1902. Le miniature dei codici barberiniani dei Documenti d’Amore. L’Arte 5: 1–20+78–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fidora, Alexander. 2021. Gundissalinus, Arabic Philosophy, and the Division of the Sciences in the Thirteenth Century: The Prologues in Philosophical Commentary Literature. In Premodern Translation. Comparative Approaches to Cross–Cultural Transformations. Edited by Alexander Fidora and Sonja Brentjes. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 63–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti, Gianfranco. 2011. Aristotele e l’Empireo. In Christian Readings of Aristotle from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Edited by Luca Bianchi. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti, Gianfranco. 2014. Introduzione. In Dante Alighieri, Opere, II. Director Marco Santagata. Milano: Mondadori, pp. 5–79. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Kenelm. 1978. Teologia. In Enciclopedia dantesca, V. Rome: Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana, s.v. [Google Scholar]

- Francesco da Barberino. 1982. I documenti d’amore di Francesco da Barberino secondo i mss. originali. Edited by Francesco Egidi. Milan: Arche. First published 1905–1927. [Google Scholar]

- Gentili, Sonia. 2005. L’uomo aristotelico alle origini della letteratura italiana. Rome: Carocci–Università degli studi di Roma La Sapienza. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, Étienne. 2016. Dante e la filosofia. Milan: Jaca book. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, Claudio. 2010. Dante: L’amore come destino. In Dante the Lyric and Ethical Poet: Dante lirico ed etico. Edited by Zygmunt G. Barański and Martin McLaughlin. London and Leeds: Legenda, pp. 119–36. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Rosalie B., Michael Evans, Christine Bischoff, and Michael Curschmann. 1979. Hortus deliciarum. Herrad of Hohenbourg. Studies of the Warburg Institute, 36. London: Warburg Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Guilelmus de Conchis. 1567. Dialogus de substantiis physicis ante annos ducentos confectus, a Vuilhelmo Aneponymo philosopho. Item, libri tres incerti authoris, eiusdem aetatis. I. De calore vitali. II. De mari & aquis. III. De fluminum origine. Edited by Guglielmo Grataroli. Strassburg: Josias Rihel. [Google Scholar]

- Guilelmus de Conchis. 1999. Glosae super Boetium. Edited by Lodi Nauta. Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Maedievalis, 158. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Gundissalinus, Dominicus. 1903. De divisione philosophiae. Edited by Ludwig Baur. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Philosophie des Mittelalters, IV. Münster: Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Gundissalinus, Dominicus. 2007. Über die Einteilung der Philosophie. Lateinisch–Deutsch. Edited by Alexander Fidora and Dorothée Werner. Freiburg, Basel and Wien: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, Pierre. 1979. Les divisions et les parties de la philosophie dans l’Antiquite. Museum Helveticum 26: 201–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hadot, Ilsetraut. 2005. Arts libéraux et philosophie dans la pensée antique: Contribution à l’histoire de l’éducation et de la culture dans l’antiquité. 2ème édition revue et considérablement augmentée. Textes et traditions 11. Paris: Vrin. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2020. Mindmapping: The Diagram as Paradigm in Medieval Art–and Beyond. In The Visualization of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Marcia A. Kupfer, Adam S. Cohen and Jeffrey Howard Chajes. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 2022. Western Medieval Diagrams. In The Diagram as Paradigm: Cross–Cultural Approaches. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger, David J. Roxburgh and Linda Safran. Washington: Harvard University Press, pp. 53–90. [Google Scholar]

- Haskins, Charles H. 1960. Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Heitzmann, Christian, and Patrizia Carmassi. 2014. Der «Liber floridus» in Wolfenbüttel: Eine Prachthandschrift über Himmel und Erde. Darmstadt: WBG. [Google Scholar]

- Hugo de Sancto Victore. 1939. Didascalicon de studio legendi. Edited by Charles H. Buttimer. Washington, DC: The Catholic University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kibre, Pearl. 1969. The Quadrivium in the Thirteenth–Century Universities (with Special Reference to Paris). In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Âge. Montréal and Paris: Institut d’études médiévales-Vrin, pp. 175–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kimball, Bruce A. 2010. The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Documentary History. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer, Marcia A. 2020. Introduction. In The Visualization of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Marcia A., Jeffrey H. Chajes and Adam S. Cohen. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 10–32. [Google Scholar]

- Imbach, Ruedi. 2003. Dante, la filosofia e i laici. Edited by Pasquale Porro. Genova and Milan: Marietti 1820. [Google Scholar]

- Imbach, Ruedi, and Catherine Koenig-Pralong. 2016. La sfida laica. Per una nuova storia della filosofia medievale. Rome: Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Oliver M. 1930. Dante’s Comparison between the Seven Planets and the Seven liberal Arts. Romanic Review 21: 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lafleur, Claude. 1988. Quatre introductions à la philosophie au XIIIe siècle. Publications de l’Institut d’Études Médiévales–Montréal, 23. Montreal and Paris: Institut d’etudes medievales–Vrin. [Google Scholar]

- Latini, Brunetto. 1968. La rettorica. Edited by Francesco Maggini. Florence: Le Monnier. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Latini, Brunetto. 2007. Tresor. Edited by Pietro G. Beltrami, Paolo Squillacioti, Plinio Torri and Sergio Vatteroni. Turin: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Michel–Pierre. 1997. Le monde des sphères. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Lines, David. 2002. Aristotle’s Ethics in the Italian Renaissance (ca. 1300–1650): The Universities and the Problem of Moral Education. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, Luca. 2013. Boezio in Dante: La ‘Consolatio philosophiae’ nello scrittoio del poeta. Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, Luca. 2018. ‘Alcibiades quedam meretrix’. Dante lettore di Boezio e i commenti alla Consolatio Philosophiae. L’Alighieri 52: 5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Maierù, Alfonso. 1995. Sull’epistemologia di Dante. In Dante e la scienza. Edited by Patrick Boyde and Vittorio Russo. Ravenna: Longo, pp. 157–72. [Google Scholar]

- Maierù, Alfonso. 2004. Dante di fronte alla Fisica e alla Metafisica. In Le culture di Dante. Studi in onore di Robert Hollander. Atti del quarto Seminario Dantesco Internazionale, University of Notre Dame (Ind.), USA, 25–27 Settembre 2003. Edited by Michelangelo Picone, Theodore J. Cachey, Jr. and Margherita Mesirca. Florence: Cesati, pp. 127–49, also in L’Alighieri 23: 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Maierù, Alfonso. 2013. Robert Kilwardby on the Division of Sciences. In A Companion to the Philosophy of Robert Kilwardby. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 353–90. [Google Scholar]

- Maldina, Nicolò. 2017. In pro del mondo. Dante, la predicazione e i generi della letteratura religiosa medievale. Rome: Salerno editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Marrou, Henri Irénée. 1969. Les arts libéraux dans l’Antiquité classique. In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Âge. Montréal and Paris: Institut d’études médiévales–Vrin, pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotta, Giuseppe. 1993. Dante’s Vision and the Circle of Knowledge. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, Anna. 1999–2000. Il ruolo delle arti quadriviali nello Speculum doctrinale di Vincenzo di Beauvais. Medioevo. Rivista di Storia della Filosofia Medievale 25: 169–234. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Kathrin. 2008. Visuelle Weltaneignung. Astronomische und Kosmologische Diagramme in Handschriften des Mittelalters. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Nardi, Bruno. 1944. Nel mondo di Dante. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura. [Google Scholar]

- Nasti, Paola. 2016. Storia materiale di un classico dantesco: La Consolatio Philosophiae fra XII e XIV secolo tradizione manoscritta e rielaborazioni esegetiche. Dante Studies 134: 142–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neckam, Alexander. 1967. De Naturis rerum libri duo, with the Poem of the Same Author, De laudibus Divinae Sapientiae. Edited by Thomas Wright. Nendeln (Liechtenstein): Kraus reprint. First published 1863. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, J. Reginald. 1969. The Liberal Arts in the Twelfth Century with Special Reference to Alexander Nequam (1157–1217). In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Âge. Montréal and Paris: Institut d’études médiévales-Vrin, pp. 127–35. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, Barbara. 2004. La cosmologie médiévale: Textes et images, 1. Les fondements antiques. Tavarnuzze (Firenze): SISMEL–Edizioni del Galluzzo. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, Barbara. 2020. The Idea of a Spherical Universe and Its Visualization in the Earlier Middle Ages (Seventh to Twelfth Century). In The Visualization of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe. Edited by Marcia A., Jeffrey H. Chajes and Adam S. Cohen. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 229–58. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, Barbara. 2022. Corporeal and Spiritual Celestial Spheres and their Visual Figurations: From Adelard of Bath and Honorius to John of Sacrobosco and Michael Scot. In The Diagram as Paradigm: Cross–Cultural Approaches. Edited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger, David J. Roxburgh and Linda Safran. Washington: Harvard University Press, pp. 253–84. [Google Scholar]

- Panella, Emilio. 1981. Un’introduzione alla filosofia in uno “studium” dei frati predicatori. Memorie Domenicane 12: 27–126. Available online: https://www.e-theca.net/emiliopanella/remigio/8100.htm (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Pegoretti, Anna. 2017. ‘Nelle scuole delli religiosi’: Materiali per Santa Croce nell’età di Dante. L’Alighieri 50: 5–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pegoretti, Anna. 2018. L’Empireo in Dante e la ‘divina scienza’ del Convivio. In Theologus Dantes: Tematiche teologiche nelle opere e nei primi commenti. Atti del convegno (Venezia, 14–15 settembre 2017). Edited by Luca Lombardo, Diego Parisi and Anna Pegoretti. Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari, pp. 161–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pegoretti, Anna. 2020. Lo studium e la biblioteca di Santa Maria Novella nel Duecento e nei primi anni del Trecento (con una postilla sul Boezio di Trevet). In The Dominicans and the Making of Florentine Cultural Identity (13th–14th centuries)/I domenicani e la costruzione dell’identità culturale fiorentina (XIII–XIV secolo). Edited by Johannes Bartuschat, Elisa Brilli and Delphine Carron. Florence: Firenze University Press, pp. 105–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegoretti, Anna. 2022. Manoscritti e testi a Santa Croce nell’età di Dante. In Dante, Francesco e i frati minori. Atti del XLIX Convegno internazionale della Società Internazionale di Studi Francescani (Assisi, 14–16 ottobre 2021). Spoleto: CISAM, pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Restoro d’Arezzo. 1976. La composizione del mondo colle sue cascioni. Edited by Alberto Morino. Firenze: presso l’Accademia della Crusca. [Google Scholar]

- Ricklin, Thomas. 2002. Théologie et philosophie du Convivio de Dante Alighieri. In La servante et la consolatrice. Edited by Jean–Luc Solère and Zénon Kaluza. Paris: Vrin, pp. 129–50. [Google Scholar]

- Roos, Heinrich. 1969. Le trivium a l’université au XIIIe siècle. In Arts libéraux et philosophie au Moyen Âge. Montréal and Paris: Institut d’études médiévales–Vrin, pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. 2018. Formes, fonctions et usages des diagrammes. In Ordinare il mondo. Diagrammi e simboli nelle pergamene di Vercelli. Edited by Marco Rainini and Timoty Leonardi. Milan: Vita e Pensiero, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude. 2019. Penser par figure: Du compas divin aux diagrammes magiques. Paris: Arkhe. [Google Scholar]

- Speranzi, Davide, Daniele Conti, Michaelangiola Marchiaro, and Dario Panno-Pecoraro. 2021. La scrittura e le letture di frate Bonanno da Firenze. Note ad usum e tracce di studio nell’antica Biblioteca di Santa Croce. In Dante e il suo tempo nelle biblioteche fiorentine, II. Leggere e studiare nella Firenze di Dante: La biblioteca di Santa Croce. Edited by Gabriella Albanese, Sandro Bertelli, Sonia Gentili, Giorgio Inglese and Paolo Pontari. Florence: Mandragora, pp. 385–92. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Nani, Tiziana. 1994. Dante Alighieri ou la convergence des arts et de la science. In ‘Scientia’ und ‘ars’ im Hoch- und Spätmittelalter. Albert Zimmermann zum 65. Geburtstag. Edited by Ingrid Craemer-Ruegenberg and Andreas Speer. Miscellanea Mediaevalia, 22. Berlin: De Gruyter, vol. 1, pp. 126–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tomazzoli, Gaia. 2023. Metafore e linguaggio figurato nel Medioevo e nell’opera di Dante. Venice: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari. [Google Scholar]

- Trevet, Nicholas. n.d. Nicholas Trevet on Boethius. Expositio Fratris Nicolai Trevethii Anglici Ordinis Praedicatorum super Boecio “De Consolacione”. Typescript of Unfinished Edition by Edmund T. Silk. Available online: https://campuspress.yale.edu/trevet/ (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Weijers, Olga. 1986–1987. L’appellation des disciplines dans les classifications des sciences aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles. Archivum Latinitatis Medii Aevi 46–47: 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Weijers, Olga. 1996. Le maniement du savoir: Pratiques intellectuels à l’époque des premières universités (XIIIe–XIVe siècles). Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Weijers, Olga. 2005. Le travail intellectuel à la Faculté des arts de Paris: Textes et maîtres (ca. 1200–1500), VI. Répertoire des noms commençant par L–M–N–0. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Weijers, Olga, and Louis Holtz. 1997. L’ enseignement des disciplines à la Faculté des arts, Paris et Oxford, XIIIe–XVe siècles. Actes du colloque international. Studia Artistarum, 4. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Weisheipl, James Athanasius. 1978. The Nature, Scope, and Classification of the Sciences. In Science in the Middle Ages. Edited by David C. Lindberg. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 461–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wieruszowski, Helene. 1946. An Early Anticipation of Dante’s ‘Cieli e Scienze’. Modern Language Notes 61: 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonta, Mauro. 2001. La divisio scientiarum presso al–Fārābi: Dalla “introduzione alla filosofia” tardoantica all’enciclopedismo medievale. In La divisione della filosofia e le sue ragioni. Lettura di testi medievali (VI–XIII secolo). Atti del Settimo Convegno della S.I.S.P.M. (Assisi, 14–15 novembre 1997). Edited by Giulio d’Onofrio. Cava dei Tirreni: Avagliano editore, pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pegoretti, A. Heavens of Knowledge: The Order of Sciences in Dante’s Convivio. Humanities 2024, 13, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13040095

Pegoretti A. Heavens of Knowledge: The Order of Sciences in Dante’s Convivio. Humanities. 2024; 13(4):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13040095

Chicago/Turabian StylePegoretti, Anna. 2024. "Heavens of Knowledge: The Order of Sciences in Dante’s Convivio" Humanities 13, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13040095

APA StylePegoretti, A. (2024). Heavens of Knowledge: The Order of Sciences in Dante’s Convivio. Humanities, 13(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13040095