Abstract

Canadian author L.M. Montgomery did not set out to write stories about romance. As she indicated in her journals, she wrote character-driven stories of young girls navigating their way through girlhood. However, she understood that the public, and her publishers, expected these girls to experience romance that culminated in marriage, following the societal traditions of the time. Montgomery managed this dichotomy by having many characters experience a suspended romance, delaying the romantic aspect of the relationship for as long as possible. Arts-based practice is a mode of analysis and offers the opportunity to find a new way of understanding and communicating Montgomery’s type of suspended romance. Music is, in many ways, considered romantic, so it is an appropriate medium to communicate Montgomery’s romantic narrative structures. This paper investigates Montgomery’s use of suspended romance in her novels and how this delay provided her characters with time to develop other areas of their lives. An arts-based methodology was used to identify and analyse recurring themes in Montgomery’s work, as the question is not can Montgomery’s theme of romance be musically represented but how. The result of this creative experimentation is a new musical composition that articulates these suspended romances using six different musical devices. This creative work exemplifies the intertextual link that exists between Montgomery’s work and new musical compositions.

1. Introduction

The degree to which music can contain essential meaning is contested within academic discourse. Nonetheless, to examine, investigate, and employ music’s many functions within society, it has ascribed to it differing contextual meanings and consequently, meaning in music is always constructed. Klein (2021, p. 60) states that “as soon as conventions, topics, trends, and compositional techniques” are employed, music becomes symbolic and hence has meaning. This article is part of a larger project that involves constructing such meaning. Using creative practice, the literary works of author L.M. Montgomery and the themes found within her work have been musically represented in new compositions, using compositional techniques to demonstrate the intertextual potential of the music. Romance is the theme chosen for this article. Musical representation, which is not a direct imitation of objects or properties, is one way in which music may be ascribed meaning. This project enacts a musical depiction of these non-auditory items that links them together through a process of creative intertextuality.

L.M. Montgomery is a Canadian author who wrote twenty novels, 530 short stories, and over 500 poems, including her best-known and most beloved work, Anne of Green Gables. Her work has been translated into over thirty-six languages and has been frequently adapted into a variety of media, including movies, stage plays, anime, musicals, animated series, and television series. Anne alone has spawned over two dozen adaptations, from a silent film in 1919 to the more recent Netflix series, Anne with an E (2017). Other novels, such as the Emily of New Moon trilogy, The Story Girl, and Jane of Lantern Hill have also been adapted into television series and telemovies, while one of Montgomery’s lesser-known and controversial works, The Blue Castle, was adapted into a stage musical in Poland. However, amongst these adaptations there does not appear to be an exclusively instrumental representation of or response to Montgomery’s worlds; the music associated with these adaptations only exists to support the visual medium or the lyrics. The connections are quite direct, such as using a leitmotif for the recurring appearance of a certain character or relationship, or music that uses tropes to directly reflect the action on the screen.

Interest in Montgomery’s work was re-activated in the mid-1980s with the publication of her life writings, or personal journals; the journals afforded the opportunity for analysis of how her life and work intertwined. As it became clear that these journals were written and revised with the intention of being published at some point in the future, the journals are considered not only life writing but also another area of Montgomery’s literature. Montgomery’s novels and her journals have been studied as intertextual documents from a number of perspectives, including gender, nature, motherhood, and education for women. This creative project continues the growing academic work around Montgomery and broadens the field to include non-traditional research in music.

Montgomery lived and wrote at the end of the Victorian era, heading into modernism at a time known as the fin de siècle. This era also saw the advent of the New Woman as part of the first wave of feminism in the 1890s. Although she claimed to be uninterested in suffrage and many other symbols of the New Woman, Gerson (2018, pp. 199–200) posits Montgomery was indeed aware of these issues but expressed them in her novels instead of her journals. Gerson (2018, p. 200) cites Montgomery’s “implicit criticisms of the Victorian institution of marriage” and her more explicit desire to attain further education, financial self-sufficiency, and respect as an author as examples of her views on the overbearing patriarchy of the time. These views are reflected in the novels in the manner in which Montgomery treats romance and the musical composition, “after all the years of separation”, which was written to represent this treatment.

The theme of romance in Montgomery’s novels is not strictly what might be expected when considering the word. She wrote what she deemed to be humorous stories for a general audience, yet her novels were confined to this genre due to market expectations (Epperly 2014, p. 8). Although her novels where the protagonist matures are considered romances because ultimately the couple unites, they are not typical romances; the romance may very broadly frame the narrative but does not lead it. The development of the character is commonly the focus, which is impacted by many factors other than romance. As the majority of her protagonists are introduced as children, they romanticise chivalry and nature with “idealized, late-Romantic, occasionally transcendentalist nature descriptions” (Epperly 2014, p. 9). As they mature, romance in nature remains, but love relationships are added as they read poems and stories that shape their romantic ideals (Epperly 2014, p. 11), while focussing on other areas of their lives.

2. Romance, Montgomery Style

Montgomery, known as Maud, did not feel her strength lay in writing adult characters. As early as 1913, when under pressure from her publisher for a third Anne book, she stressed young girls were less interesting and not suitable to the same level of humour (Montgomery 2016, p. 130):

“Only childhood and elderly people can be treated humorously in books. Young women in the bloom of youth and romance should be sacred from humour. It is the time of sentiment and I am not good at depicting sentiment—I can’t do it well. Yet there must be sentiment in this book. I must at least engage Anne for I’ll never be given any rest until I do”.

While Montgomery (2018, p. 197) understood the public’s need for a romantic resolution, she also felt the restrictions of the era and genre conflicted with her understanding of the characters she created:

“…the public and publishers won’t allow me to write of a young girl as she really is. One can write of children as they are; so my books of children are always good; but when you come to write of the ‘miss’ you have to depict a sweet, insipid young thing—really a child grown older—to whom the basic realities of life and reactions to them are quite unknown. Love must scarcely be hinted at—yet young girls in their early teens often have some very vivid love affairs. A girl of ‘Emily’s’ type certainly would… I can’t afford to damn the public. I must cater to them for awhile yet”.

Consequently, romantic relationships in these novels are not the focus of the narrative. An example is Rilla of Ingleside, which is primarily about Rilla’s coming of age in a time of war, the experiences of women on the home front, and the gender roles and restrictions of various characters. Rilla’s relationship with Kenneth Ford is a very minor detail, and her character would still have developed considerably without it or even despite it. Yet, as Kazuko Sakuma (2021, p. 20) attests, the relationship nevertheless frames the overall narrative, giving Rilla the happy ending the public expected. Marigold Lesley (Magic for Marigold) is only eleven or twelve when her novel ends, so a heterosexual romance has not led the narrative; however, Montgomery still introduces a young boy in the last chapter and finishes the novel with Marigold deciding she will always be there for him to come back to, again appeasing the public’s desire for at least a hint of romance by the novel’s end (Montgomery 1925, p. 308).

The Emily series is widely acknowledged as the most autobiographical of Montgomery’s works, and this, coupled with the fact that Montgomery was now older and had met successful and fulfilled career women in Toronto, meant “Maud had no interest in the inevitable—consigning Emily to marriage” (Rubio 2008, p. 638). But the public was not willing to accept Emily choosing her career instead of marriage and inundated Montgomery with letters regarding which potential suitor Emily should choose. None of the three options were particularly suitable in relation to Emily’s literary aspirations—neither of the two main suitors had much interest in her writing, and one even used it against her—but Montgomery had little choice (Rubio 2008, pp. 654–55). Such was her distaste for marrying Emily that she delayed finishing the book and turned to writing The Blue Castle instead, the only time she worked on two books concurrently.

Romance appears in Montgomery’s work in forms other than a heterosexual love relationship. As Epperly (2014, p. 9) notes, “the main characters grapple consciously or unconsciously with their conception of the romantic,” struggling to define what romance is, what their sense of self is, and how those things align with cultural expectations. The romance of strong female friendships is a prevailing theme in Montgomery’s work, and these friendships, along with poetry, literature, and nature, provide a lot of the romance in the young girls’ lives. Robinson (2012, p. 170) notes that young girls in the fin de siècle described their friendships with “adolescent hyperbole”; such language is not used in relation to heterosexual romantic relationships. Anne Shirley (Anne of Green Gables) loves her bosom friend, Diana Barry, “with all the love of her passionate little heart” (Montgomery 1908, p. 103) and is inconsolable at the thought that one day Diana will marry and leave her, proclaiming, “I hate her husband—I hate him furiously” (Montgomery 1908, p. 103). Similarly, Pat Gardiner (Pat of Silver Bush) speaks effusively of her love for her friend, Bets Wilcox. She also considers a future with her friend marrying unbearable, bemoaning, “Bets, when I think of it I couldn’t suffer any more if I was dying. Bets, I just couldn’t bear it” (Montgomery 1933, p. 209). After Bets dies, it takes Pat until she is in adulthood to find another friend.

In writing of Anne Shirley, Thompson (2022, p. 215) recognises that her “sense of the sensual and the romantic is tied to nature and friendships with other girls”. The connection to nature is a characteristic Montgomery shared with many of her protagonists. She was very attuned to a place in Cavendish she named Lover’s Lane, declaring, “I love it idolatrously. I am never anything but happy there” (Montgomery 1987, p. 73). Each time she revisited the Island in her adulthood, it was a place she longed to see, and she bestowed an Avonlea version of Lover’s Lane on her first character, Anne. Once married, Anne moved to a home near the sea, feeling “a certain tang of romance” in its nearness as it “entered intimately into her life” (Montgomery 1917, p. 45). How she feels about being married to Gilbert is not mentioned, speaking more of “wind, weather, folks, house of dreams” (Montgomery 1917, p. 44), making their honeymoon special rather than each other. Valancy Stirling (The Blue Castle), a twenty-nine-year-old spinster who has given up on conventional romance, finds her idea of it in her imagined Blue Castle but also in the nature books written by John Foster that bring her “some faint, elusive echo of lovely, forgotten things” (Montgomery 1926, p. 12). She instigates a marriage with a man she loves but who she believes does not love her and finds all the romance of her Blue Castle on his small island in the middle of Lake Mistawis. The only setting of all Montgomery’s novels that is not Prince Edward Island, it is described in language such as “diaphanous lilac mist” and a “rose-hued” sky (Montgomery 1926, p. 194), and Valancy recognises she is living “amid all the romance of Mistawis” (Montgomery 1926, p. 219).

Anne also creates many ideals of romance from what she reads, and it is only after trying to recreate Tennyson’s The Lady of Shallot with comic and near-disastrous results (Anne of Green Gables) that she realises the reality of Avonlea is far from the romance of Camelot (Thompson 2022, p. 218). As Anne grows, her reading leads her to develop the ideal of a romantic suitor, and she continually snubs Gilbert Blythe because he does not match the “very tall and distinguished looking, with melancholy, inscrutable eyes, and a melting, sympathetic voice” (Montgomery 1909, p. 154) romantic profile of her imagination. The rejection continues for quite some time, even though it is likely the readers’ expectations are similar to those of Mrs Rachel Lynde, who proclaims, “That’ll be a match some day” (Montgomery 1915, p. 18), or Miss Lavendar, who declares, “Because you were made and meant for each other, Anne” (Montgomery 1915, p. 144).

3. Romance and Music

There is a long association between romance and music. As Gioia (2015, p. 109) observes, music related to love and romance began to flourish when the stranglehold of Christianity’s influence gave way to the growth of the troubadours in the High Middle Ages. During this time, the focus of marriage shifted from a transaction arranged by parents to a relationship consented to by the bride and groom—the concept of romantic courtship (Gioia 2015, p. 110). Gioia further claims that regardless of the economic status, education, or societal standing of the audience, people were increasingly drawn to music that relates “to matters of the heart,” music that over the following four centuries would expand to include madrigals, ballads, and opera as prominent and popular musical forms (Gioia 2015, p. 109). Program music, in which music no longer supported lyrics but had meaning of its own, gained popularity in the nineteenth century and was often inspired by love and romance. Some examples are Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique (1830), about a failed love affair; Schumann’s Fantasie in C major Op. 17 (1936), which began as an articulation of the composer being parted from his love; and Janáček’s Intimate Letters (1928), which was an expression of his love for a younger woman.

Modern popular music is heavily populated by romance-related songs with themes ranging from yearning and the excitement of new love through to laments of lost love and heartbreak. Many movie soundtracks will contain within their non-diegetic underscoring a ‘Love Theme’ as a leitmotif for the protagonists (The Godfather, Cinema Paradiso, and Blade Runner, among many) as well as trope-driven music to reflect the romantic action on screen. In the movie The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996, pos. 22:40), the female protagonist even says, “When we fall in love, we hear Puccini in our heads” and at the end of the movie, when the protagonists reunite, the non-diegetic music swells and morphs into Puccini’s Nessun Dorma.

The formal features of music, as well as its emotional expressivity, are valuable core elements, according to Kania (2013, p. 641). It should be noted at this point that the term emotion is a construct encompassing all types, durations, and intensities of affective reactions (Rosenwein 2006, p. 4). One of the reasons music is consumed is because of how it resonates emotionally with the listener, who may even select a certain genre or particular piece with the expectation that listening will enhance or even change their mood (Rosenwein 2006, p. 4). A study by Jorgensen-Wells et al. (2022, p. 805) of music consumption by adolescents who are discovering romance showed that as the adolescents are forming their romantic identities, they listen to music more frequently, even learning about romance from the music they consume. What they are absorbing is a mixture of lyrics and music. Lyrics aside, there may be certain features of the music that tell the listener it is representing romance; these features are a mixture of conventions and concepts that have over time become accepted as representing particular emotions. A simple example of this in the Western canon is that major and minor modes have a widely recognised correlation with broad positive and negative emotions.

4. Methodology

As an original composition is a core element of the research process, this project employs an arts-based research methodology. Dooley (2022, p. 5) attests that in the study of music and literature there is “room for many critical and theoretical approaches” and I have chosen to guide my methodology with conceptual frameworks of hermeneutics and intertextuality. The result is a non-traditional research output (NTRO); NTROs were recognised by the Australian Research Council as “valid expressions of research” in 2009 (Barwick and Toltz 2017 p. 67). Barwick and Toltz (2017, p. 67) further note that artistic research, such as the composition of music, was defined in 2012 by Henk Borgdorff as “creative works of research”. For this reason, I believe my compositions, along with their contextualization, are considered research output in the same way as a text research paper.

This project utilises all twenty of Montgomery’s novels along with her personal journals; Montgomery kept journals from her teenage years until the end of her life and they provide a wealth of information about her experiences and attitudes. They also show how her life affected her work, and considerable academic discourse exists related to the intertextual links between her novels and journals. Furthering the conceptual framework of intertextuality beyond novels and journals, this project investigates the intertextual links between music and the written word, specifically L.M. Montgomery’s written word. Both deductive and inductive coding were used to identify recurrent themes in the novels and journals, and musical compositions were then created to intertextually represent each of the themes. Romance is one of the most prevalent themes ascertained.

Arts-based research involves the creation of an artefact and its contextualisation and, as Bell (2018, p. 47) describes it, “acknowledge(ing) art activity as a fusion of creative and critical elements”. Various terms are used to describe this style of research, but imperative to defining it is the notion that the research occurs through practice, with Gray (1996, p. 3) asserting the needs of the practitioner and their practice lead to the recognition and development of questions and challenges. The research is an expansion of practice methods, not a contrast to them, creating an environment that is both reflective and generative (Gray 1996, p. 10). Reciprocity underpins the nature of theory and practice, with Gray stating, “Critical practice should generate theory and theory should inform practice” (1996, p. 15). As a relatively recent methodology, arts-based research still encounters some scepticism. Kerrigan and McIntyre (2019, p. 213) purport the best way to defend it is to ensure the methodology is “grounded in traditional understandings of the philosophical aspects of research”. Smith and Dean (2009, p. 1) assert creative practice contributes to research in “many rich and innovative ways”, including providing research insights and developing unique processes for research but also that research can lead to practice in an “iterative cyclic web” (Smith and Dean 2009, p. 2). Additionally, Brabazon (2020, pp. 44–45) emphasises practice-led methods should only be chosen when the questions cannot be answered with conventional research; the choice must be directly related to the research questions and be the best way to answer them (Brabazon 2020, pp. 44–45). The artefact moves beyond existing knowledge and the exegesis connects the knowledge with the new artefact. In this article the role of the exegesis is taken by the section that analyses the composition, providing contextualization for the choices made. Arts-based research is the prime methodology for this project, as the question is not can Montgomery’s theme of romance be musically represented but how. Rather than simply discussing possibilities, creative experimentation resulting in a musical composition allows this question to be addressed more directly.

During the process, insights also came from other areas; in contrast to traditional research models that involve a sole researcher, arts-based research involves a community. This community is formed as the creative work is analysed and interpreted for performance and recording, as well as by those who are interpreting through active listening. Bell (2018, p. 64) asserts that recognising these contributions will “encourage the critical dialogue and reflective practice” that are vital to research. As interlocutors in the process, the performers of the compositions contributed to the outcome, both through feedback about the feasibility of the compositions and by providing recordings for analysis. The conceptual frameworks of hermeneutics and intertextuality are addressed more fully below.

4.1. Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics may be defined as the art of interpretation as a pathway to understanding. The first step in composing the music was to read and analyse the novels and journals, and a hermeneutic interpretation was practised when reading the texts and was later applied to the creative practice. Ideographic disciplines require understanding rather than reason and an acknowledgement that this understanding stems from the human perspective. For this reason, hermeneutics suits the reading of Montgomery’s novels and journals, as both the content and the interpreter are connected to the human condition and not scientific method or reason.

There are three main lenses of textual analysis that ask where meaning rests and if discerning meaning is possible: the author’s intention, the text itself, and the reader (Xian 2020, pp. 105–23). Each of these lenses has been regarded as having the most importance in various historical periods. As Xian (2020, p. 108) states, “Meaning is produced through use” and is not pre-existing. Successful interpretation of a text requires a combination of the author, what is in the text, what is added to the text by the reader, and context. If meaning is derived from multiple interactions, then hermeneutics and intertextuality are suitable frameworks for textual analysis. There are similarities here with the field of semiotics, although, as Kramer (2020, p. 57) claims, hermeneutics is more “free-form” than semiotics. The triad system of Charles Sanders Peirce’s semiotic theory that includes an interpretant is more similar to hermeneutics than Ferdinand de Saussure’s dyad system of only signified and signifier, as the interpretant figure is vital. The reader/listener is bringing their own history to the experience, so the interpretant is what comes to their mind when they encounter a sign, and it is likely each person will bring to the sign something different.

Tradition and prejudice are two major influences that need to be considered when using hermeneutics as a form of interpretation. Hans-Georg Gadamer, whose book Truth and Method is considered by many to contain the foundation of postmodern hermeneutic philosophy, foregoes the interpretation methodology of historicism—the belief that preconceptions can be set aside and subjectivity erased—for what he terms the fusing of horizons. The past and present merge to create “effective history” (YaleCourses 2009, loc. 26.48) across historical, social, cultural, and interpersonal horizons. I brought to this interpretation the knowledge I already had of Montgomery’s time period, and while it affected how I interpreted the works, and particularly the novels, I also learnt a great deal more about the era by reading the journals, which in turn affected how I interpreted the novels. Following a pattern known as the hermeneutic circle, the interpretant constantly moves between the text and the context, and in doing so, reaches deeper levels of analysis and improved interpretations. Hermeneutics and intertextuality are closely linked; as relating two texts to each other requires an understanding of the texts, intertextuality is a conduit of hermeneutic power.

4.2. Intertextuality

As this project involves the intertextual link between music and literature, it is crucial to understand how music may be intertextual. Although intertextuality was initially related to literature, it has now been expanded to include all forms of visual and aural art. Originally named by Julia Kristeva in 1966–67, the concept was influenced by Mikhail Bakhtin’s assertion that all utterances exist only when put into context with other utterances. Each text is not static or finished, according to Nikolenko (2023, p. 108), but “a dynamic entity that emphasizes relational processes and practices within the text”. As the Bakhtinian theory was partially inspired by the concept of musical polyphony, Kostka et al. (2021, p. 4) assert that including music in intertextuality makes perfect sense. They continue to support music’s inclusion in this theory by explaining that music is multi-voiced, as is intertextuality, and also includes the listener as “an intertextual partner in dialogue, or as an endless web of echoes and resonances reaching one’s ear from different points in space and time” (Kostka et al. 2021, p. 4). Writing about quotation as a specific form of intertextuality, Prevost (2022, p. 23) claims composers use “intertextual relations” to “engage with works of the past”. She further explains that these connections are more successful when the listener “recognises the cited work and engages with the two works” (Prevost 2022, p. 23). In this way, I hope those listeners familiar with the works of Montgomery will have that material brought to mind when hearing the music. Indeed, at a concert of my music involving a different theme in Montgomery’s literature, an audience member stated that the music was “a reminder of how beautiful language can be”. As Kramer (2021, p. 17) emphasises, there is no such thing as musical intertextuality, but “Music simply participates in intertextuality like everything else”.

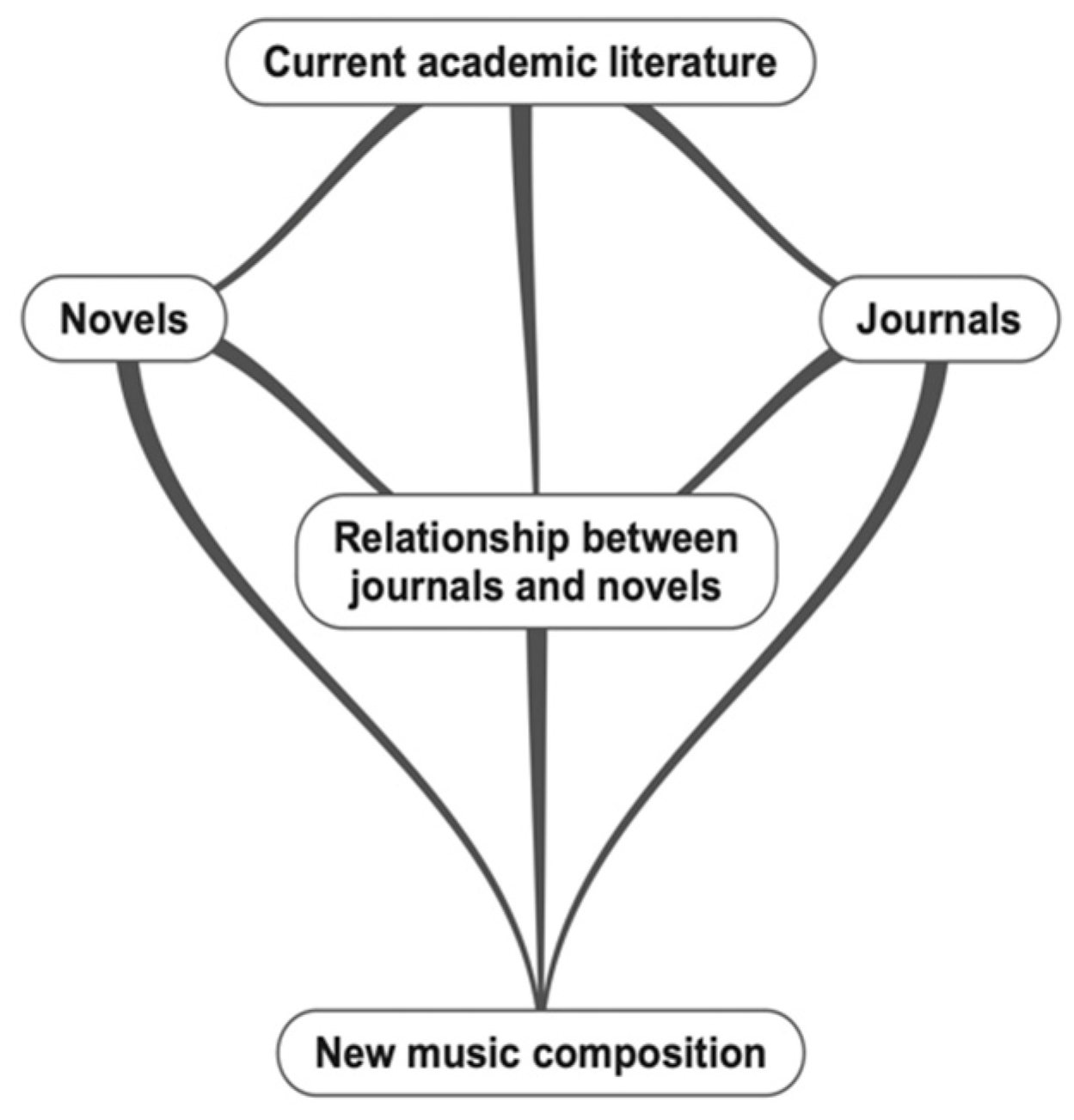

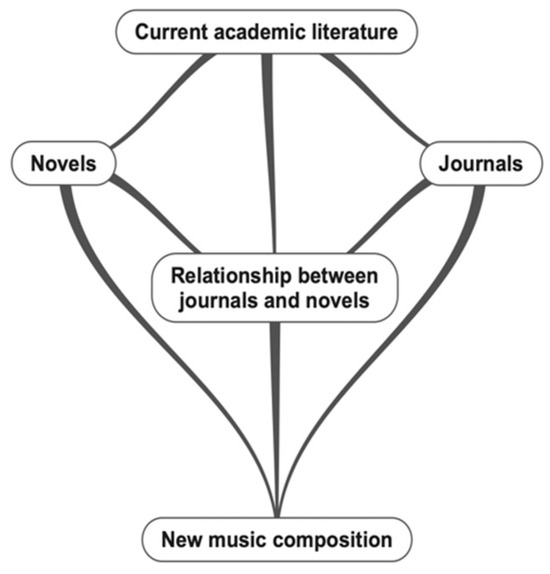

Consequently, intertextuality is not only a suitable framework for examining the connections between Montgomery’s novels and personal journals, but it is also an applicable framework for a number of dynamics in the project. The first intertextual layer is the relationship between Montgomery’s works and current academic literature, which exists in a few forms. While there is literature related to her novels, there is also considerable discourse around her journals; however, another layer exists with the literature discussing the intertextual link between her journals and novels and how her work was influenced by her life. Finally, a new layer was generated with a non-traditional research output—the creation of the musical composition—which intertextually represents not just the novels and journals but also the existing connection between the two. Figure 1 presents these relationships.

Figure 1.

Intertextual relationships.

However, it is important to note that intertextuality is not limited to a simple comparison of the texts, and this is due to temporality. Plett (1991, p. 25) argues intertextuality is synchronic, which means all texts exist at the same time and are therefore interrelated, while Birrell (2007, p. 12) discusses an “epistemological time warp”. Although Montgomery’s novels and journals were written many decades ago, they still exist at the same time as the new musical composition. Montgomery’s works, having remained popular for more than a century, may fall into the category Plett calls “commonplaces” (Plett 1999, p. 316). These are works in the Western canon that are not only firmly established but are also based on familiar structures due to imitation and are, in turn, potential models for texts yet to be created. Replicated in full, in part, or in collections, they become dependent on each other within the canon and develop into virtual intertexts, ready for further reactivation, which is necessary for maintaining their meaning (Plett 1999, p. 325). As Nikolenko (2023, p. 108) attests, no literary work stands alone but is a product of how it relates to both other texts and “the structures of language itself”. Additionally, Plett (1999, pp. 323–24) affirms intertext between art forms can be either syntagmatic, where works are combined into one new form, or paradigmatic, which is substituting one form for another. In this research project, the creation of the musical composition is an example of paradigmatic intertextuality, as the “commonplaces” are being represented musically.

4.3. Representation

There are different philosophies regarding whether, and to what degree, music can represent something else, and the term requires careful definition. As Bicknell (2009a, p. 12) explains, if representation means making a likeness of something, then we would be limited to representing sounds; however, “not all representations look like the things they are supposed to represent”. If it is accepted that music can represent non-auditory properties, then the representation capabilities are endless (Bicknell 2009a, p. 13). Conversely, Graham (2005, p. 92) claims music can represent things, but only in a very limited way. Although he makes this statement, he is arguing the notion that music cannot be used to communicate and is using representation as part of communication. Taken on its own merits, he believes representation is certainly possible but “dependent upon conventional associations”, which are culture-based and often not understood between different cultures (Graham 2005, p. 101), or what Kim (2023, p. 3) calls “encultured listening”. Bicknell concurs, adding these widely accepted cultural conventions are what allow the representations to be understood (Bicknell 2009a, p. 12). DeNora terms this an “intertextual relation” and avers music’s power arises from its intertextual connection with subjectivity and the listener’s preferences (Iurascu 2010, p. 201).

These conventions that support representation are termed “ineliminable” by Kim (2023, p. 2), who argues they contribute to the structure of the music and therefore cannot be discounted. She further compares the representational capacities of music and language and stresses that although they communicate content in different ways, both still do so. While words have their own essential meaning, there can be multiple definitions that rely on context and definition; similarly, the context of music that brings meaning is in how it is composed, performed, and received (Kim 2023, pp. 3–4). Additionally, Bicknell (2009b, p. 37) avers if a representation works effectively, its meaning continues, and connections can then be made between the representation and other things.

What is also agreed on is how representation works. Graham (2005, p. 86) is adamant that representation should not be confused with replication or imitation, such as birdsong or bells. The aim of representation is not to imitate a sound but to put the idea of that object or event in the mind of the listener (Graham 2005, p. 86). Bicknell explains this as furnishing aesthetic ideas; the aesthetic attributes of a creative work do not simply offer a given concept but “engage and enliven the mind by alerting it to the possibility of an unlimited range of related representations” (Bicknell 2009b, p. 37). As Kramer stated in an interview (The Public Voice Salon 2017, pos. 35:30):

“This is not the old idea of you expressing musically what the poem expresses in words—that’s exactly what you don’t do. What you do is create aesthetic intellectual and emotional provocation. So how do you think about this? How do we feel about this? And if people come away with a thought that hasn’t occurred to them before … you’re doing your work”.

5. Suspended Romance and “After All the Years of Separation”

A tactic Montgomery uses to allow her protagonists to develop outside of their romantic interests is suspended romance, and I wrote the piece “after all the years of separation” to represent this. It contains a number of devices designed to represent the suspension and uncertainty of these romances, with each device being revealed in a different motif. In semiotic theory, each of the six devices is a signifier/representamen, while the facets of the suspended romance are the signified/objects. However, as Kramer (2020, p. 66) stresses, these signifiers are not the total source of meaning in the music but “a particular subdivision of meaning”. The third part of the triad, the interpretant, is what appears in the listeners’ minds when they hear the music and contains “a network of dispositions, orientations, attitudes, affects, and models of action” (Kramer 2020, p. 66); this also contributes to meaning. As a composer, I cannot determine what a listener will think or feel but enter the process with a desire to present them with opportunities to make an intellectual and emotional connection with a certain theme.

The overall premise of this work is that phrases do not resolve as may be expected; the perfect or imperfect cadences of traditional harmony that guide the sense of direction do not exist. Small bursts of unexpected behaviour can be as simple as adding an accidental on the last note so the cadence does not resolve. The main signifiers in the form of musical devices used are as follows:

- Melodies that do not resolve in a traditional manner. This lack of resolution was chosen to denote romances not travelling the expected path; as the melodies take an unexpected turn, so do the relationships.

- Passages of sustained notes. These phrases are more drawn out than the majority of the composition and were included to signify the dragging out of the relationships.

- Each instrument has a short solo. As the characters often spent protracted time apart while waiting for the romance to resolve, I chose to signify this by providing each instrument with a solo passage.

- Extending time signatures. This device was selected to symbolise the relationships being drawn out longer than expected; the consistent beat of the music is unexpectedly stretched out, as are the suspended romances.

- Staccato passages. This signifier is included to metaphorically tiptoe around the relationship.

- Short, quick, demisemiquaver runs. These were chosen to characterise how quickly Montgomery has the characters come together in the end; this representation is the only time demisemiquavers are utilised in the piece.

A recording of the piece may be located at https://on.soundcloud.com/YyMrECBQjUo71Ehj8 (uploaded 21 April 2024), and time stamps are provided in the following discussion. The instrumentation of a woodwind trio was chosen for the cohesion of the similar tones. While it may take a while to resolve, there are usually narrative clues that the relationship is heading in that direction, guiding the readers’ expectations. Emily Starr and Teddy Kent (Emily of New Moon), still children, plan their future together in the Disappointed House, although Emily believes “maybe we could find a way to manage without going to all that bother” of marriage (Montgomery 1923, p. 258). Anne initially hates Gilbert with a passion Montgomery equals to Anne’s aforementioned love for Diana, which is strong because of their bond. When he first proposes and Anne refuses, she acknowledges that her “world has tumbled into pieces” without Gilbert in it (Montgomery 1915, p. 133). As soon as a lost Pat Gardiner sees Hilary ‘Jingle’ Gordon, “suddenly she felt safe… protected” and after a quick introduction, “They were just like old, old friends” (Montgomery 1933, pp. 67–68). The connections between these future couples are made evident from the beginning, and using instruments from the same family in the composition represents this togetherness.

The theme of suspended romance has been discussed by a number of authors, including Marah Gubar and Benjamin Lefebvre, who concur that Montgomery utilises the suspension to provide her protagonists with time to develop their personal growth, female friendships, education, and careers—what Gubar (2001, p. 51) calls “exploring avenues unconnected to the traditional marriage plot”. Nickel (2009, p. 106) disagrees with the opinion that the suspensions occur for this purpose, stating that all romantic fiction will “postpone romantic reconciliation until the end”. However, I believe that while Nickel’s argument applies when the postponement is serving to heighten romantic tension, Montgomery uses postponement to allow her heroines to flourish and achieve other things in life. Lefebvre (2002, p. 151) asserts Montgomery concentrates on the “emotional and artistic development of her female characters”, which is why the romantic endings can sometimes appear “tacked-on” and consequently “underdeveloped and contrived”. The previously mentioned Rilla and Marigold romances fit this category, as does Pat’s eventual reunion with Hilary (Mistress Pat). Rilla did not even know Kenneth was home from the war until she saw a list of returned soldiers in a two-week-old newspaper. He turns up at her home unexpectedly in the last few paragraphs of the book, so changed since the time she last saw him that she at first does not recognise him, but once he speaks her name, their future is suddenly sealed. After years away, Hilary returns to Pat in the last five pages of the book. Similar to Rilla and Ken, their relationship has had no chance to develop with them as adults, yet the quick romantic conclusion completes the story.

As her journals are part of the intertextual relationship and show that her life impacted her writing, it is relevant to note that Montgomery herself experienced a suspended romance. She stayed on Prince Edward Island in Cavendish to care for her ailing grandmother while her minister fiancé left to study and then accepted a call to a congregation in Leaskdale, Ontario. Only once her grandmother passed was there “no longer any reason for delaying my already long-deferred marriage” (Montgomery 1987, p. 396). In her novels, romances are suspended for a number of reasons, including study, work, indecision, interfering parents, lack of finances, or one of the pair taking time to recognise the love, although the seeds were there. Anne and Gilbert of the Anne series experience a range of reasons. Initially, Anne is angry with Gilbert for a schoolroom taunt, and they become academic rivals. Even after they reconcile, they remain friends for many years before romance takes over. Gilbert always loves Anne, but he realises early that he needs to keep his intentions quiet until she is ready: “But Gilbert did not attempt to put his thoughts into words, for he had already too good reason to know that Anne would mercilessly and frostily nip all attempts at sentiment in the bud” (Montgomery 1909, p. 155). While in college, he proposes for the first time, causing another rift in their relationship until Anne finally understands she loves him when his life is endangered. Even then, they are separated for three more years while Gilbert studies medicine; during this time Anne is the principal of a private girls’ school.

In Anne’s world, she is not alone in experiencing a suspended romance; there are also several secondary characters and stories related to people facing a similar fate. Anne thoroughly enjoys being a matchmaker, and often these matches involve reconciling couples who have been apart for a long time—Theodora Dix and Ludovic Speed,1 Nora Nelson and Jim Wilcox (Anne of Windy Willows), and Janet Sweet and John Douglas (Anne of the Island), among others. The story of Leslie Moore, which is the narrative heart of Anne’s House of Dreams, also involves a romance that is unable to flourish because of circumstance. Leslie and her boarder, Owen Ford, fall for each other but cannot pursue a relationship as Leslie is tied to her disabled, childlike husband, Dick, and Owen leaves. It is only sometime later, when Dick is revealed to have a different identity, that Anne is able to orchestrate a reunion between Leslie and Owen, and their romance can begin.

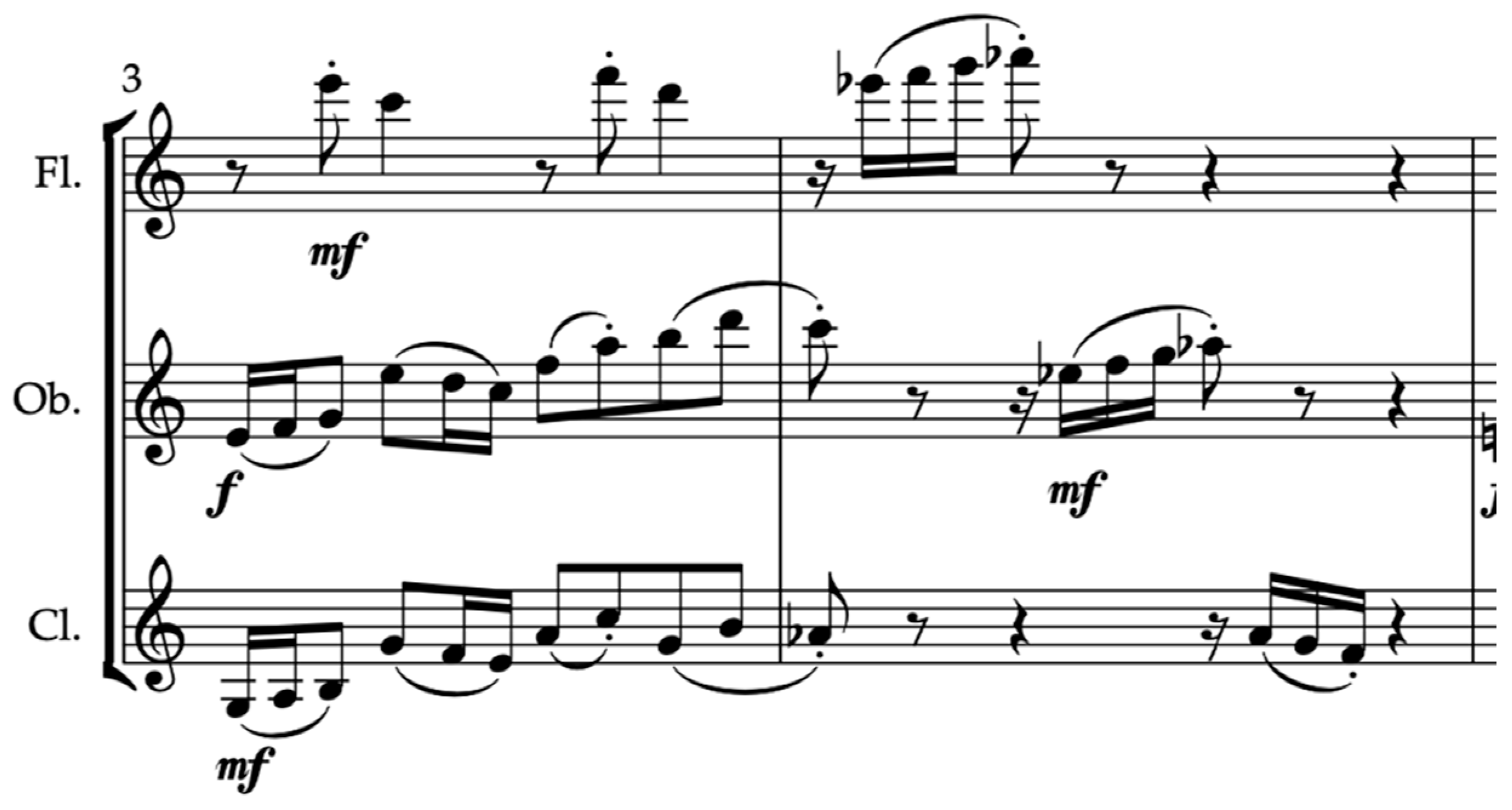

In the composition written to represent these suspended romances, the first section, up to bar 31, establishes the motifs and utilises three devices from the list above. The first of these is the lack of resolution, which I have applied to most phrases in this section. The first example occurs in bar 4, timestamp 0:10 (Figure 2); as the composition is in C major, traditional harmony would suggest the phrase is heading to the tonic chord, but instead the C is harmonised with an A flat rather than the expected G.

Figure 2.

Lack of traditional harmonic resolution example 1.

In bar 8, timestamp 0:24, again the expectation would be to resolve the phrase on the tonic chord, but instead it moves to an Am7 (Figure 3), which is one of the four chords used in various places throughout the rest of the piece.

Figure 3.

Lack of traditional harmonic resolution example 2.

I have introduced these chords with their unhindered versions in bars 9–14, timestamp 0:24–0:42, where they introduce the suspension device of sustained notes. These chords are held for the duration of the bar (apart from allowing for breaths), representing the long stretches of time waiting for the suspended romances to resolve (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sustained notes symbolising extended relationships.

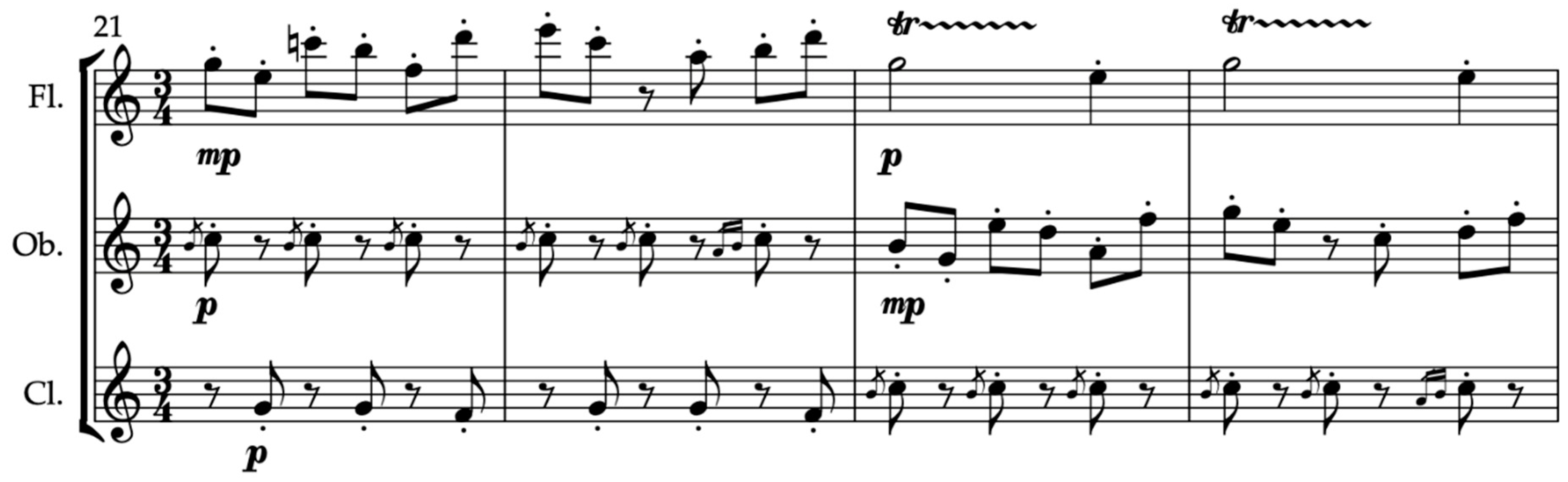

In bar 21, timestamp 1:01, a staccato motif based on the flute’s accompaniment pattern in bars 5 and 6 begins, which signifies the caution and tiptoeing around the relationship, particularly those in which one person is initially more invested than the other (Figure 5). In the Anne series, Gilbert falls in love with Anne at their first meeting, but they do not become engaged until the end of the third book. In the meantime, he has to constantly gauge how far he is able to move their friendship to something else, often needing to retreat after his efforts.

Figure 5.

Staccato motif representing tiptoeing around the relationship.

Emily (the Emily series) has two suspended romances, very different in nature, with men present through all three novels. Although she ends up with her childhood friend, Teddy Kent, the two of them and their friends, Ilse Burnley and Perry Miller, spend years tangled in the confusion of who really loves who in the group. There is even a point in the third book (Emily’s Quest) where Teddy and Ilse nearly marry, until they hear Perry has been injured, and Ilse consequently jilts Teddy at the altar. By this point, Teddy has given up on winning Emily’s love, but she has finally recognised that she loves him. Their relationship is not resolved until the end of the book, and the union occurs quickly; as aforementioned, this was not the fate for Emily that Montgomery would have chosen, so it was pushed to the end.

In the first novel, Emily meets Dean Priest, a man twenty-three years her senior, when he saves her life. Instantly intrigued by the twelve-year-old, Dean states, “I think I will wait for you” (Montgomery 1923, p. 240), which he proceeds to do until, at nineteen, Emily finally agrees to marry him. Although a great source of friendship and intellectual inspiration, Dean cajoles and manipulates Emily throughout their relationship, always with this end goal in mind. She acknowledges she is not in love with him, and he accepts that “he’s quite satisfied with what I can give him—real affection and comradeship” (Montgomery 1927, p. 76)—but after a psychic connection with Teddy in which she saves his life from the other side of the world, she recognises her connection with Teddy and breaks the engagement with Dean.

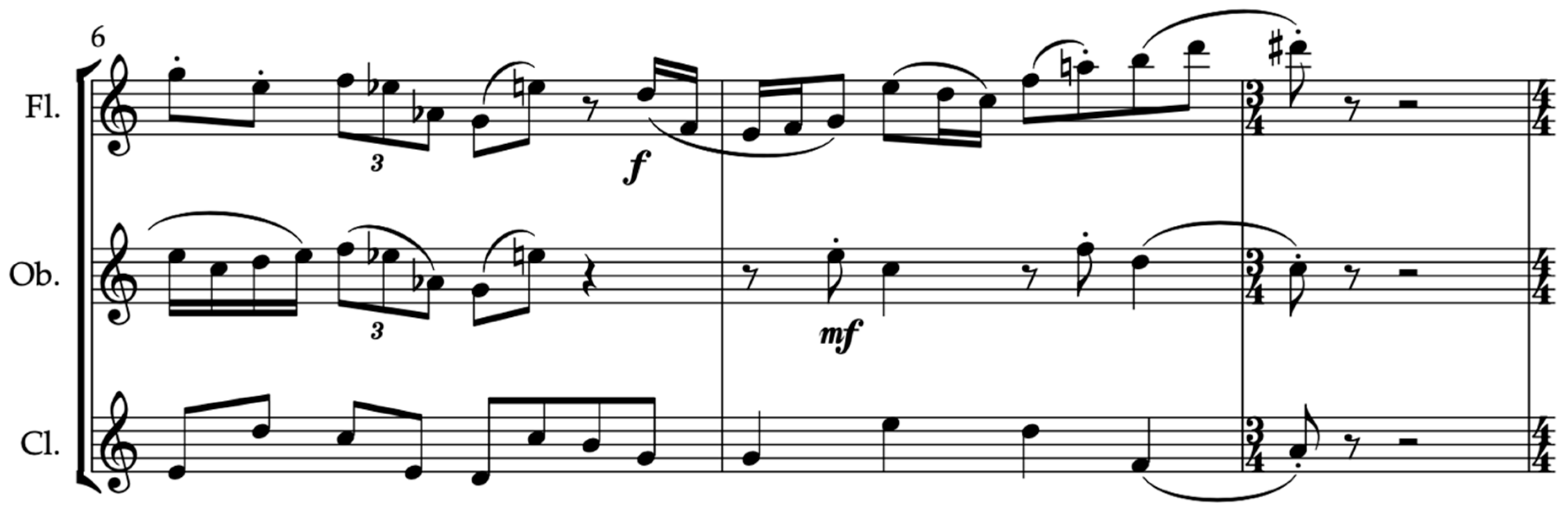

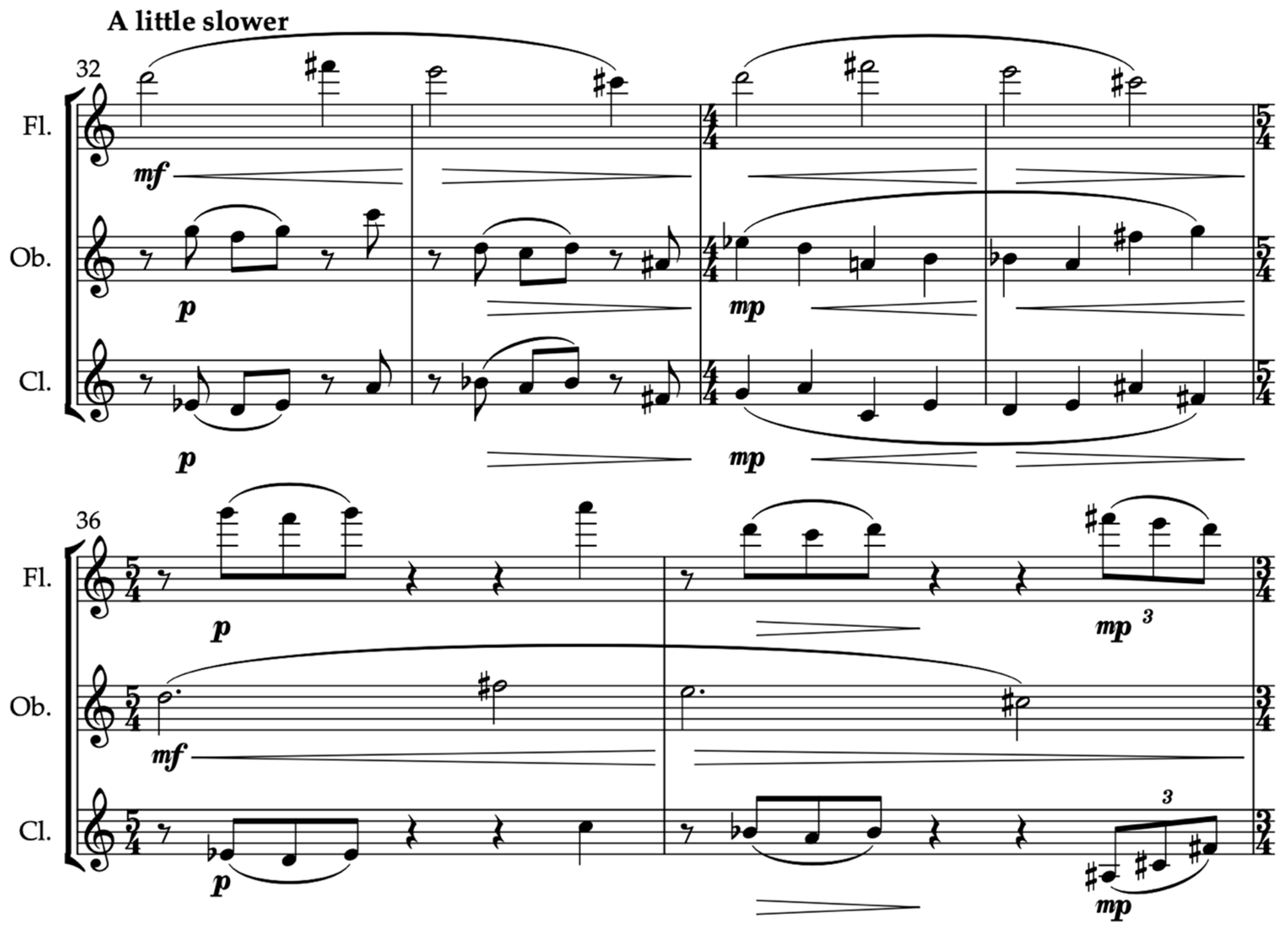

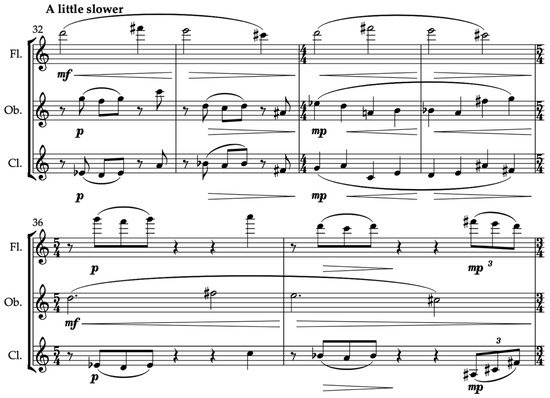

Continuing the representation of these romances, the second section of the composition, from bar 32 to 44, timestamp 1:25–2:07, begins with a gentler motif that is a variation of the notes of the four main chords motif. It continues the use of unresolved phrases and staccato tiptoeing, but I have also introduced extending time signatures and short, quick runs. Across bars 32 to 37 (timestamp 1:25–1:48), the time signatures expand from 34 to 44 and then to 54, with each one lasting for only two bars (Figure 6). This represents the occasions when the romance is extended further than expected. As aforementioned, even once engaged, Anne and Gilbert are separated for a further three years due to his study, while in Anne’s House of Dreams, Cornelia Bryant and Marshall Elliott’s relationship is suspended for twenty years after he makes a political vow of which Miss Cornelia does not approve.

Figure 6.

Expanding time signatures symbolising relationships stretched further than expected.

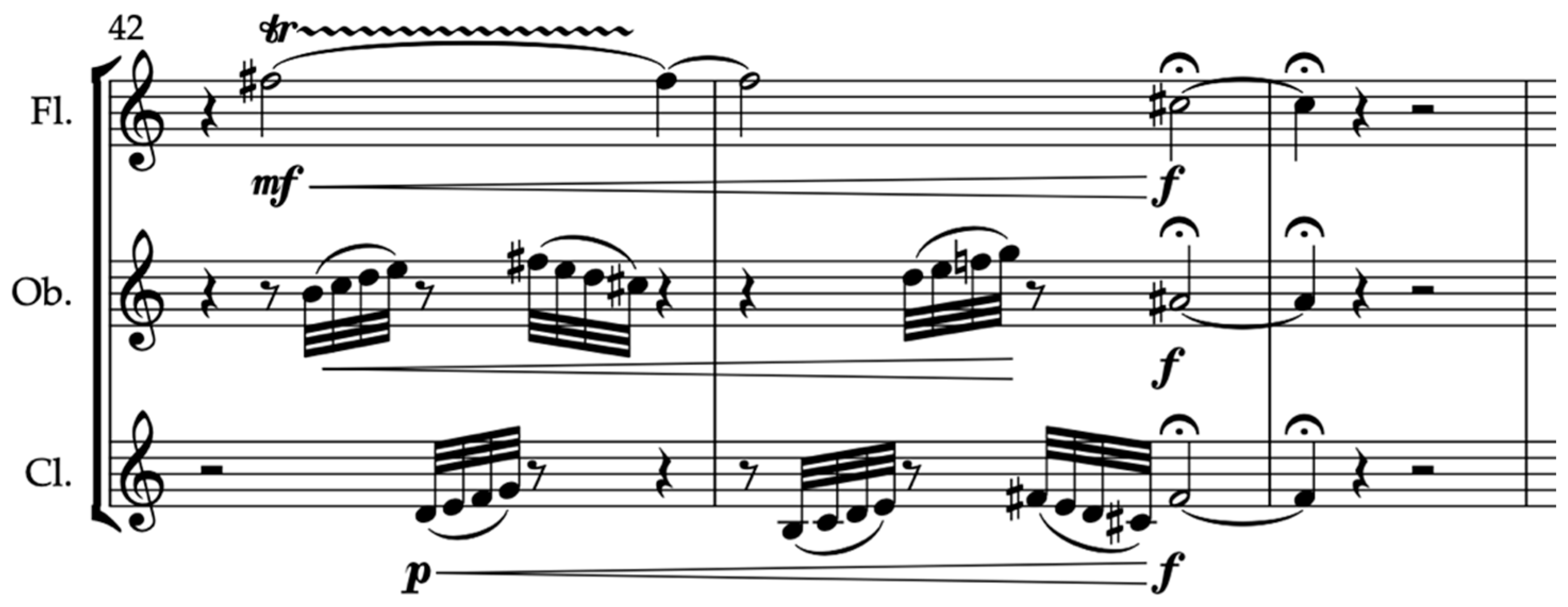

Quick, short runs of either semiquavers or demisemiquavers are introduced in bar 42, timestamp 2:00 (Figure 7) and used through the rest of the piece to suggest that these romances usually resolve extremely quickly once the impediment or misunderstanding is removed.

Figure 7.

Rapid, short runs representing quick relationship resolutions.

The Pat series has a heroine who is so connected to her home that marriage is unthinkable, as due to the patrilocal tradition of women moving to where their husbands reside, marriage would mean leaving Silver Bush, her home. Pat is extremely emotionally connected to Silver Bush. Her childhood friend and the boy who loves her, Hilary, has moved away to study, and Pat has a succession of unsuccessful suitors as her life becomes more lonely and unhappy. As Hilary hears of these relationships in an embellished form, he ceases communication with Pat. Now in her early thirties, Pat becomes engaged to a neighbour, David, because she is afraid of losing more friends—“Life with him would be a very pleasant pilgrimage” (Montgomery 1935, p. 243)—but after Hilary visits, David breaks the engagement, recognising Pat’s connection to him, even though she does not. It is only after Silver Bush burns down and Hilary returns that Pat realises she loves him, and the romance can truly begin. In Kilmeny of the Orchard, Kilmeny refuses to begin a relationship with Eric because she cannot speak, even though he tries to assure her that it does not matter to him. Once she regains her voice and their romance can begin, she delays their marriage so she can learn more about the world in general.

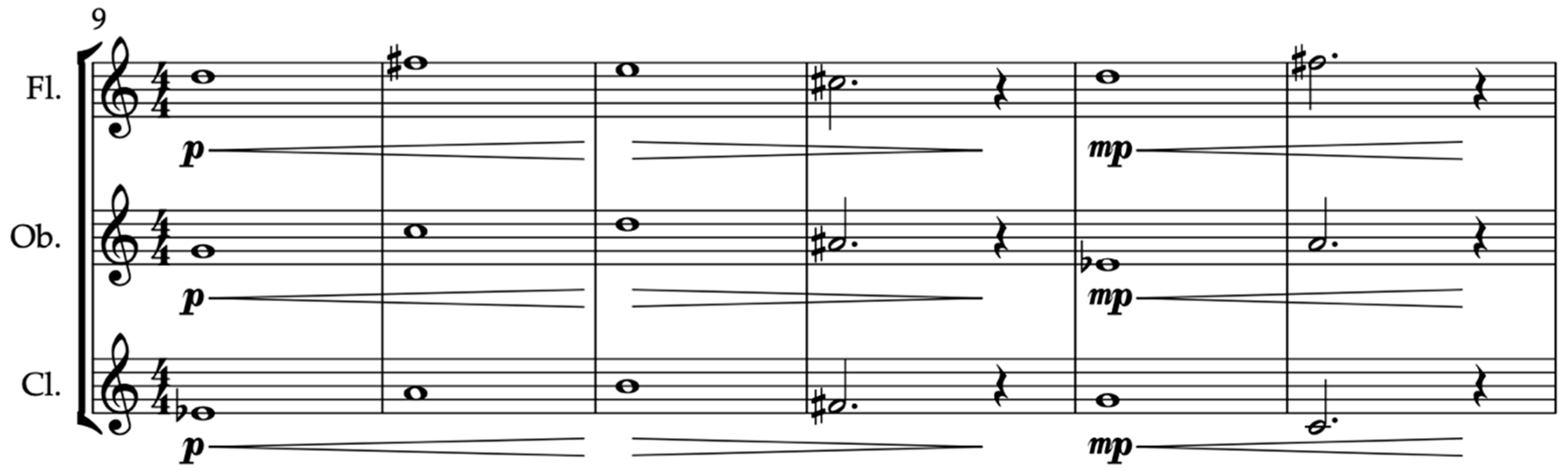

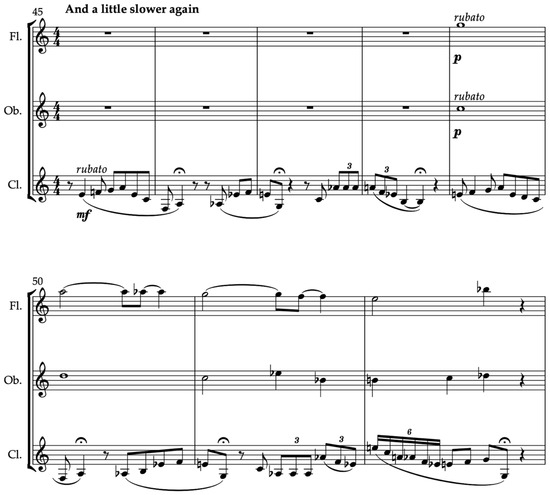

The next three sections of the composition all begin with one instrument introducing the theme with a short solo, which is the third suspension device. I chose this device to denote the time characters spend on their own without their significant partner, whether this be the aforementioned duty/study/work separations or total separation following an argument. As an example, the clarinet begins the third section with a solo at bar 45 (timestamp 2:09), and after starting gently, the accompaniment builds (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Instrumental solo beginning section denoting time character spends alone.

Staccato moments are again a feature of this section, and the device of quick runs is used extensively, culminating in bars 56 and 57 (timestamp 3:07–3:17) having a succession of demisemiquaver runs between all three instruments (Figure 9), again signifying the characters’ romances often being very quickly resolved.

Figure 9.

Demisemiquaver runs denoting rapid relationship resolution.

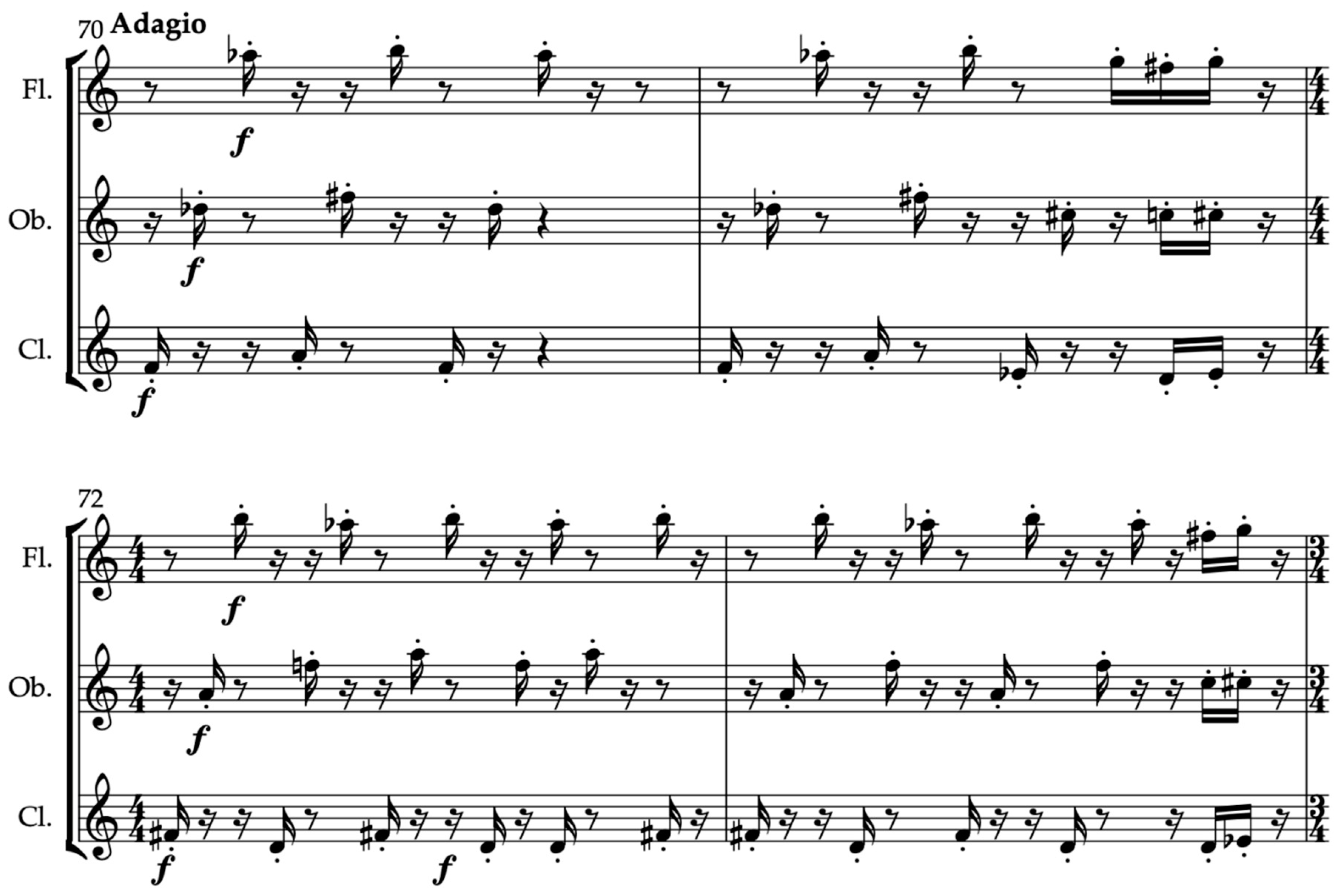

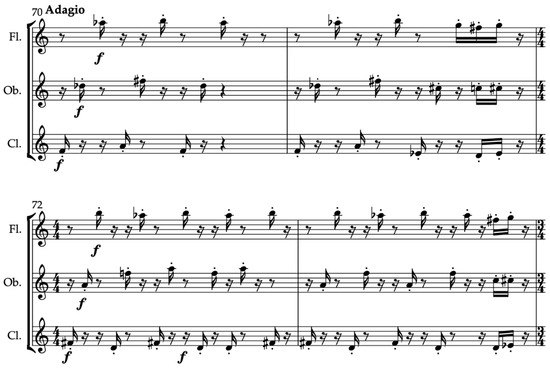

The fourth section begins at bar 59, timestamp 3:23, and modulates to Gm with a significantly reduced tempo from the original motif it mimics. The oboe solo in a minor key represents the romances that contain an unpleasant suspension, such as quarrels or family interference. The uncertainty created by the often dissonant staccato features prominently, with the expanding time signatures expanded further to include 64. The tempo increases at bar 70, timestamp 4:03, as the instruments play staccato notes one after the other (Figure 10), signifying the couples are not quite on the same path. The sense of urgency increases as the instruments come together, both with the staccato notes and quick, demisemiquaver runs.

Figure 10.

Staccato notes separate but follow each other, symbolising couples not on the same path.

Continuing the device of solo instruments beginning new sections, I began the next part (bars 79–95, timestamp 4:48–5:42) with a flute solo, which is brighter and more lyrical than the previous section and uses all of the devices. Although the devices are still in place and there is no harmonic resolution, it feels more cohesive and indicates the relationships are heading towards unity. The piece then culminates (from bar 96) in a brief revisiting of each of the previous sections, bringing everything together and finally concluding with an expected resolution (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Traditional harmony resolution denoting couple finally together.

6. Conclusions

The main question of the research project was not whether Montgomery’s text could be musically represented, but how this would occur, and for this reason, a methodology of arts-based research was selected. Writing the composition allowed me to ascertain how the theme of suspended romance could be represented. In this way, the research occurred through the practice of composition rather than simply discussing compositional possibilities, with the result being a non-traditional research output (NTRO) and its contextualization. The music I have composed is unique in that it is an adaptation in which the music stands alone as a representation of Montgomery’s worlds; its role is not to reinforce a visual or lyrics, but to intertextually match the text. Also novel in the total project—of which this theme and composition are one part—is that it is the prominent themes within Montgomery’s work that are being represented, as well as the methodology used to create this work, which will be further explained below.

Hermeneutics had a significant impact on the outcomes of the project. A type of interpretation that leads to understanding, hermeneutics includes bringing one’s own preconceived ideas, culture, experience, beliefs, etcetera to something, and in the area of textual analysis, this results in the reader being more purposeful and engaged. In reading Montgomery’s novels and journals, bringing my own life experience and understanding to the reading made a marked difference to how I viewed the characters and noticed the themes compared to when I had previously read them as a teen. Additionally, reading hermeneutically also impacted how the composition was devised, as my response to the theme became the basis for the overall style of the composition.

Intertextuality is the relationship between two texts, and as both intertextuality and music are multi-voiced, it is an applicable framework for a music-centred research project. Already existing are intertextual links between Montgomery’s novels and journals, her novels and academic literature, and her journals and academic literature. This new composition adds another layer to that framework as it is intertextually linked to all three existing areas, with the information from all three being considered when determining musical devices to use. Learning more about Montgomery’s world brought a different understanding to the way she writes, such as understanding how and why she experienced her own suspended romance and how this was reflected in her characters. The existing intertextual links have now been broadened by the addition of the new composition. Rather than standing alone, music partakes in intertextuality like any other type of text; not only are the compositions participating in the intertextuality of the Montgomery texts, but it is these intertextual links that help to bring meaning to the music. As Klein (2021, p. 60) attests, “conventions, topics, trends, and compositional techniques” contribute to musical meaning, and in this project, these things have all been introduced as a musical response to Montgomery’s words, furthering the intertextual connection.

Defining representation is the cornerstone to understanding its position in this project and how the music is linked to the text. Representations do not need to be a direct replica of an item, which means music can represent non-auditory items and is commonly understood due to cultural conventions. My approach to representation is that it is about putting an idea into the listeners’ minds that may not necessarily have been there before, provoking them to consider new possibilities when hearing the music. Using creative practice, the research—and specifically the composition—adds to the existing canon of music representing literature while also providing a new adaptation of Montgomery’s worlds. Compositional techniques have been used to demonstrate the intertextual potential of music. Moreover, it confirms the idea that musical intertextuality is not a separate entity but that music can participate in intertextuality along with other media forms.

Funding

This research has been financially supported by the Australian Government’s Research Training Program Scholarship (Fee Offset) and the Bill and Michelle Stewart Postgraduate Scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | The Hurrying of Ludovic is a short story published in Chronicles of Avonlea (1912), which is not included in this research, but the relationship is referenced in both Anne of the Island and Anne of Ingleside. |

References

- Barwick, Linda, and Joseph Toltz. 2017. Quantifying the Ineffable? The University of Sydney’s 2014 Guidelines for Non-Traditional Research Outputs. In Perspectives on Artistic Research in Music. Edited by Robert Burke and Andrys Onsman. Oxford: Lexington Books, pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Desmond. 2018. The Primacy of Practice: Establishing the Terms of Reference of Creative Arts and Media Research. In Screen Production Research: Creative Practice as a Mode of Enquiry. Edited by Craig Batty and Susan Kerrigan. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell, Jeanette. 2009a. History: Music Gives Voice to the Ineffable. In Why Music Moves Us. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bicknell, Jeanette. 2009b. The Tears of Odysseus. In Why Music Moves Us. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell, Susan. 2007. Approaching Mt. Everest: On Intertextuality and the Past as Narrative. Journal of Sport History 34: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon, Tara. 2020. The Specificity of Creative-led Theses. In The Creative PhD. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 9–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, Gillian. 2022. Listening to Iris Murdoch: Music, Sounds and Silences. Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. 2014. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance, 3rd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerson, Carole. 2018. ‘Fitted to Earn Her Own Living’: Figures of the New Woman in the Writing of L.M. Montgomery. In The L.M. Montgomery Reader Volume Two: A Critical Heritage. Edited by Benjamin Lefebvre. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 198–211. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, Ted. 2015. Love Songs: The Hidden History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Gordon. 2005. Philosophy of the Arts: An Introduction to Aesthetics, 3rd ed. Oxon: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Carole. 1996. Inquiry through Practice: Developing Appropriate Research Strategies. In No Guru, No Method? Helsinki: UIAH, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gubar, Marah. 2001. ‘Where Is the Boy?’: The Pleasures of Postponement in the Anne of Green Gables Series. The Lion and the Unicorn 25: 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurascu, Viorica-Barbu. 2010. Musical Representation and Musical Emotion. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 2: 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen-Wells, McKell A., Sarah M. Coyne, and Janna M. Pickett. 2022. ‘Love Lies’: A Content Analysis of Romantic Attachment Style in Popular Music. Psychology of Music 5: 804–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, Andrew. 2013. Music. In The Routledge Companion to Aesthetics, 3rd ed. Edited by Berys Gaut and Dominic McIver Lopes. London: Routledge, pp. 639–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan, Susan, and Phillip McIntyre. 2019. Practitioner Centred Methodological Approaches to Creative Media Practice Research. Media Practice and Education 20: 211–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hannah H. 2023. Convention and Representation in Music. Philosopher’s Imprint 23: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Michael L. 2021. Intertextuality and a New Subjectivity. In Intertextuality in Music: Dialogic Composition. Edited by Violetta Kostka, Paulo F. de Castro and William A. Everett. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kostka, Violetta, Paulo F. de Castro, and William A. Everett. 2021. Introduction. In Intertextuality in Music: Dialogic Composition. Edited by Violetta Kostka, Paulo F. de Castro and William A. Everett. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Lawrence. 2020. The Musical Signifier. In The Routledge Handbook of Musical Siginification. Edited by Esti Sheinberh and William P. Dougherty. London: Routledge, pp. 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Lawrence. 2021. What Is (Is There?) Musical Intertextuality? In Intertextuality in Music: Dialogic Composition. Edited by Violetta Kostka, Paulo F. de Castro and William A. Everett. Oxon: Routledge, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Benjamin. 2002. Stand by Your Man: Adapting L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Essays on Canadian Writing 76: 149–69. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1908. Anne of Green Gables. 1985 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1909. Anne of Avonlea. 1985 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1915. Anne of the Island. 1985 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1917. Anne’s House of Dreams. 1985 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1923. Emily of New Moon. 1985 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1925. Magic for Marigold. 1981 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1926. The Blue Castle. 1980 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1927. Emily’s Quest. 1985 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1933. Pat of Silver Bush. 1981 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1935. Mistress Pat. 1982 print. North Ryde: Angus & Robertson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 1987. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901–1911, 2017th ed. Edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston. Ontario: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 2016. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1911–1917. Edited by Jen Rubio. Ontario: Rock’s Mills Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Lucy Maud. 2018. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1922–1925. Edited by Jen Rubio. Ontario: Rock’s Mills Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, Eleanor Hersey. 2009. ‘The World Hasn’t Changed Very Much’: Romantic Love in Film and Television Versions of Anne of Green Gables. In Anne with an ‘E’: The Centennial Study of Anne of Green Gables. Edited by Holly Blackford. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, pp. 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolenko, Olha. 2023. Forms of Intertext in ‘Anne of Green Gables’ by L.M. Montgomery. Scientific Journal of Polonia University 60: 107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plett, Heinrich F. 1991. Intertextualities. In Intertextuality. Edited by Henirich F. Plett. New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Plett, Heinrich F. 1999. Rhetoric and Intertextuality. Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric 17: 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, Roxane. 2022. Musical Quotation in Richardson/Morlock’s Perruqueries (2013): Humour as a vehicle for social commentary. British Journal of Canadian Studies 34: 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Laura M. 2012. ‘Sex matters’: L.M. Montgomery, Friendship, and Sexuality. Children’s Literature 40: 167–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenwein, Barbara H. 2006. Introduction. In Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages. London: Cornell University Press, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Mary Henley. 2008. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, Apple Books ed. Vaughan: Anchor Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma, Kazuko. 2021. The White Feather: Gender and War in L.M. Montgomery’s Rilla of Ingleside. In L.M. Montgomery and Gender, Kindle ed. Edited by E. Holly Pike and Laura M. Robinson. Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Hazel, and Roger T. Dean. 2009. Introduction: Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice—Towards the Iterative Cyclic Web. In Practice-Led Research, Research-Led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edited by Hazel Smith and Roger T. Dean. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- The Public Voice Salon. 2017. Prof Lawrence Kramer on Literature + Music. YouTube Video, April 22, 58 min 32 s. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, William V. 2022. Transformative Girlhood and Twenty-First-Century Girldom in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. In Children and Childhoods in L.M. Montgomery: Continuing Conversations. Edited by Rita Bode, Leslie D. Clement, E. Holly Pike and Margaret Steffler. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, pp. 201–20. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, Zhou. 2020. Textual Meaning in the Complex System of Literature. Philosophy and Literature 44: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YaleCourses. 2009. 3. Ways In and Out of the Hermeneutic Circle. YouTube Video, September 2, 46 min 44 s. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).