Abstract

Hundreds of thousands of hectares of bushland and accompanying biodiversity were lost over a few short weeks during the Black Summer fires of 2019–2020 along the east coast of Australia. On the night of 19 December 2019, fire swept up the escarpment from the coast, slowed down with the thick understory of temperate rainforest and burnt through the lower dry sclerophyll forest on Plumwood Mountain. The aftermath of the bare, burnt landscape meant a significant change in the structure and diversity of vegetation, while the consequences of the fire also brought about fundamental changes to Plumwood as a conservation and heritage organisation. Plumwood Mountain as a place, the individual plumwood tree as an agentive being, Val Plumwood as a person and Plumwood as an organisation are all an entangled form of natureculture and indicative of a practice-based conservation humanities approach. Conservation as part of the environmental humanities can offer an alternative to mainstream models of conservation with the potential to instigate active participation on the ground, engaging in a different form of stewardship.

1. Introduction

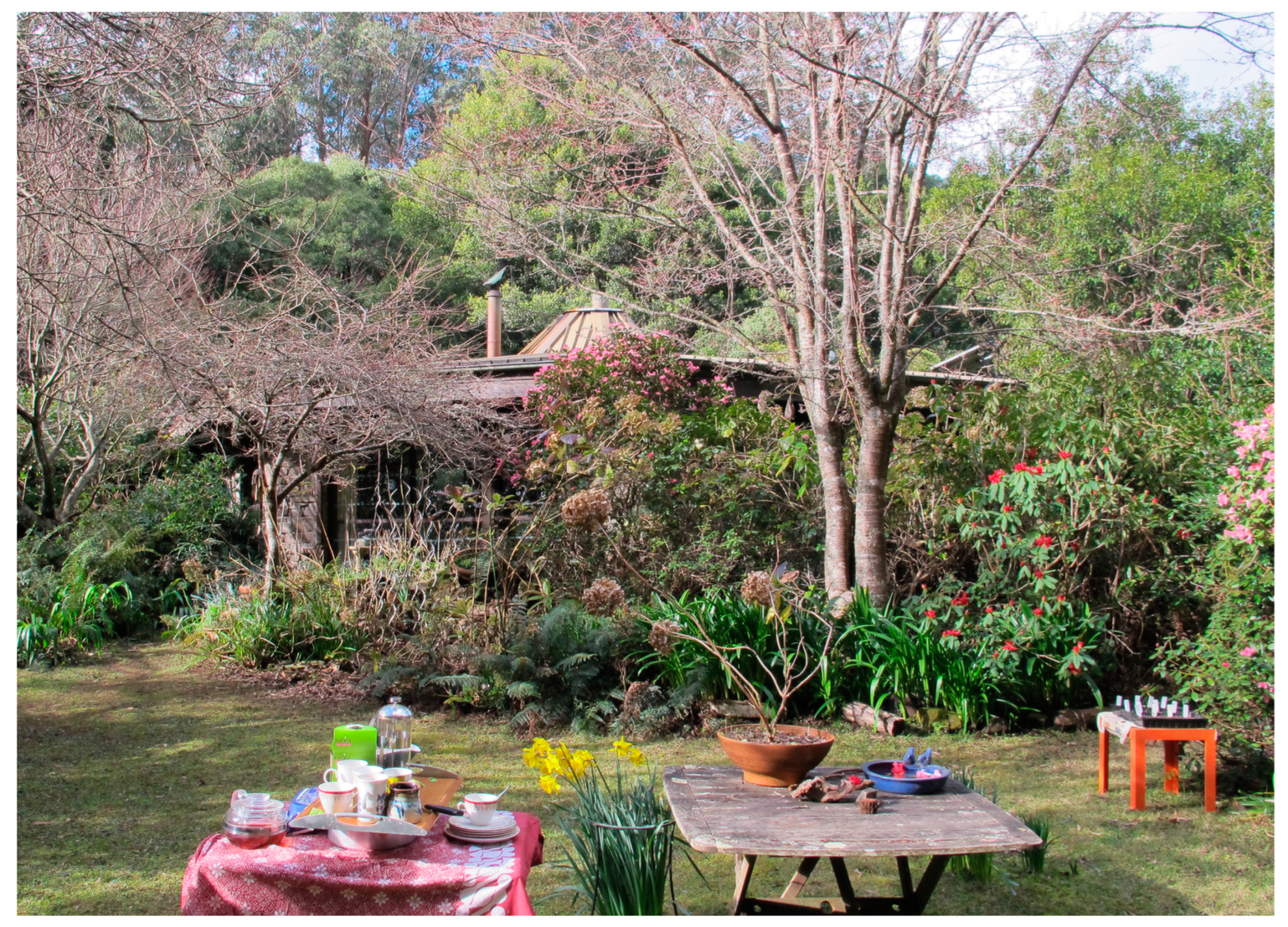

Plumwood Mountain is a unique place in New South Wales, situated on a coastal escarpment with a canopy of different species of eucalypts, a forest grove containing rare Plumwood trees (Eucryphia moorei) amidst abundant tree ferns (Antarctica dicksonia) with threatened marsupials, such as a refuge population of greater gliders (Petauroides sp.) nesting within old canopy trees. A distinctive hexagonal stone cottage and garden is situated in the dense forest, home for over three decades to environmental philosopher Val Plumwood. She would sit and write, surrounded by the sounds of the forest, actively living her theory of breaking down dichotomies, striving instead for an entanglement between mind and body, nature and culture, theory and practice, rather than a hyper-separation between the two (Plumwood 2002).

The conservation humanities can be a means of not only theoretical and conceptual critique, but as I will illustrate below, has the potential to instigate active participation in conservation on the ground, as a means of caring for the land and as a form of environmental education. Engagement with heritage is important too, in terms of protecting indivisible cultural and natural inheritance with accompanying knowledge practices. Plumwood as an organisation includes a committee, largely made up of like-minded people working with the environment, conservation, humanities and the arts in relation to Plumwood Mountain as a place. Rather than a scientific-oriented species-specific approach to conservation, our perspective is based on environmental philosophy, while actively engaging in a different kind of ethics focusing on the care and nurturing of a more-than-human community. My intention is to use Plumwood as an exemplar for a practice-based conservation humanities approach with an emphasis on the importance of stewardship, instead of a dominating, capitalist perspective of ownership and control of distinct parcels of land. The aim is to re-orient peoples’ thinking in the recognition that we are all part of an interconnected ecosystem, while finding different ways to negotiate living with other species through a deep connection to place.

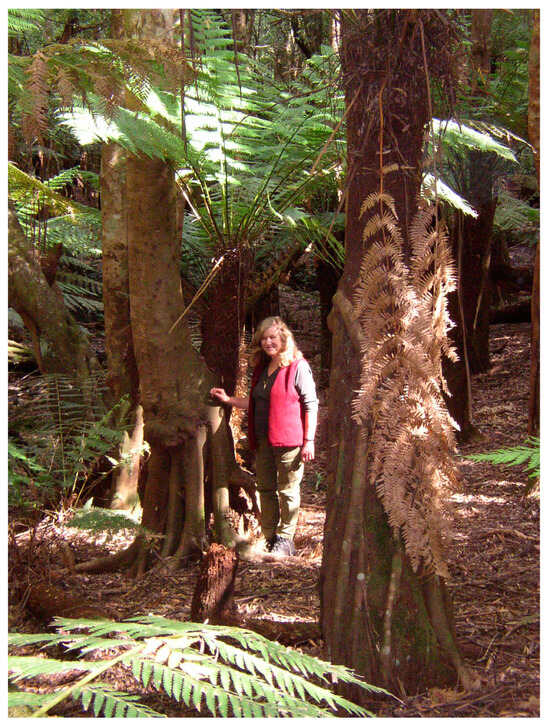

The following is a subjective narrative based on my experience participating and observing as a founding member of Plumwood Inc. Others involved with Plumwood would no doubt convey events differently based on their own subjective experiences. I have been an active member of the Plumwood executive for many years, including president of the organisation from 2019 to 2021, which has been separate from my usual anthropological research engaging with multispecies, visual and sensory ethnography in the Khangai of Mongolia and Arnhem Land in Australia. Here I describe the different entangled forms of Plumwood: Plumwood Mountain as a place, the plumwood tree as an agentive being entangled with a specific kind of tree fern, Val Plumwood as a person and Plumwood Inc. as a conservation and heritage organisation. Throughout this article, I refer to Val Plumwood as “Val” to avoid confusion between the other forms of Plumwood (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Val Plumwood next to a plumwood tree, entangled with a healthy tree fern, in the Plumwood Gully, 2 December 2004. Photo: Judith Adjani, digital copy passed on to the author.

2. A “Cool” or “Hot” Burn?

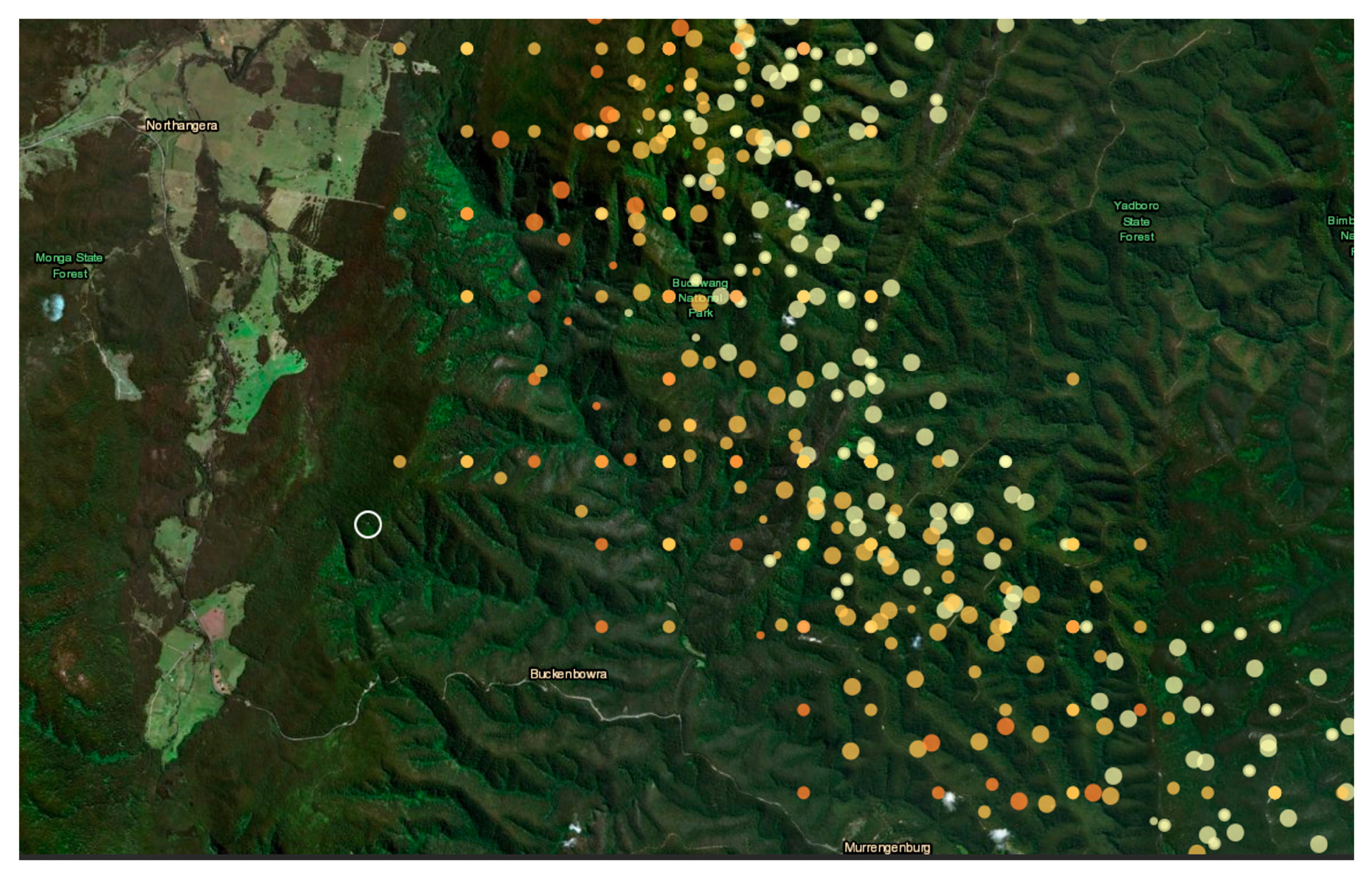

In late December 2019, I had been repeatedly checking Digital Earth Australia (DEA) and the Rural Fire Service’s “Fires Near Me” application, as for the past few weeks, fires had burnt through Tallaganda, Budawang and Monga National Parks, devouring any bushland that surrounded the historic township of Braidwood where I live (an hour’s drive from the Australian capital of Canberra). Orange dots were gradually filling in any area on the DEA map that had not yet burnt, as if filling in gaps on a jigsaw puzzle. Plumwood Mountain was one of the few areas of bushland that had not yet been filled in with orange dots indicating that it was on fire (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Screenshot from Digital Earth Australia with different coloured dots indicating the heat of the fire front (the clearing at Plumwood Mountain is indicated by a white circle added by the author), 6 December 2019.

Within email correspondence between committee members in early December, we expressed growing concerns about what may happen to Plumwood Mountain with fire approaching. I had already evacuated from my Braidwood home, after the historic township had narrowly missed burning down one evening. The town was only saved by the large number of fire trucks that arrived from surrounding areas to put out the numerous grass fires that kept sparking up from floating embers. I wrote to the committee with deep concern for the fate of Plumwood Mountain:

Plumwood is in very real danger within the next few days, until there’s some rain. From the DEA map it looks like there are some spot fires, separate from the main fire front, very close to the Plumwood clearing. It’s hard to tell how accurate these ‘hot spots’ are, but it doesn’t look good. RFS [Royal Fire Service] have been notified that no one is currently up at Plumwood and they have the coordinates for the house and clearing … The road is closed down the Clyde, as the RFS are back-burning, presumably to stop the fire from crossing over the Kings Highway.Email correspondence with the Plumwood committee, 6 December 2019.

The Black Range bushfire to the west and the Currowan bushfire to the east kept growing by the hectare over a period of seven weeks from late November 2019 until mid-January 2020, resulting in significant devastation to properties in the region.1 The wind had been blowing like a hot furnace, fuelling a fire that had been left to increase in size within the Currowan State Forest for weeks to become a behemoth mega-fire, consuming more than a hundred thousand hectares.2

By the evening of 19 December 2019, National Parks staff conveyed via text that the fire was on the escarpment, only 500 m from the stone cottage up at Plumwood Mountain. We knew from our flurry of emails that fire was inevitable at this stage and all we could hope for was a “cool” rather than “hot” burn. I worried that the Gondwanan-era Plumwood Grove may have been decimated, even more so than the potential loss of the house and gardens in the clearing, as the ancient forest could never be replaced.

The fire built up momentum as it ripped up the steep 1000-m escarpment from the South Coast, splitting in three to be renamed the Clyde Mountain fire.3 During the night, fire swept through much of the thick understory of temperate rainforest and through dry sclerophyll forest in lower areas. The burnt landscape I encountered afterwards was a dramatic change to the senses, in comparison to the dense and tangled forest I had encountered previously. The fire also brought about fundamental changes to the Plumwood committee that I had already been a part of for seven years prior to the fire. The catastrophic effects of climate change had been felt keenly along the east coast of Australia that summer, both bodily and psychologically, as hundreds of high-intensity fires burnt out of control, covering 24.3 million hectares.

3. The Plumwood Driveway: Between Hope and Despair

After the fires had abated, a local friend, who had been on the Plumwood committee previously, had been setting up feed and watering stations in Monga National Park. Once it seemed safe to head up the Plumwood driveway, he filled up a water tank on a trailer, and we added food for wildlife donated by the local supermarket, including sweet potatoes, corn, carrots, and fruit, as well as hay and birdseed. The local community had rallied together, and many in the Braidwood and even Canberra region coordinated together through word of mouth and social media to head out regularly to burnt locations to supply wildlife with food and water.

Even the gate posts were partially burnt as we entered the bush, which now consisted of a barren understory, transformed to a smooth, grey-brown crust of ash. We established feed stations with blue paddling pools to provide some water along the rough 2.4-km dirt track that leads from the gate on the main highway, through Budawang National Park, to Plumwood Mountain. I was relieved to see that the canopy of the trees on either side of the driveway was largely still alive. Precarious-looking burnt branches protruded out onto the road though, while whole burnt trees looked ready to topple in the next wind. After treading across the ash-covered surface, mindful to occasionally look up to avoid any potential falling limbs, I could see that all was not lost. When I dug not far beneath the crusty upper layer, the soil beneath contained matted roots. Even the occasional ant could be seen moving about, foraging. I was hopeful witnessing these few signs of life. In contrast, when I had gone to assist with the feeding of wildlife in Tallaganda State Forest, it had felt like another planet with no signs of life immediately above or below the surface, apart from one lone wallaby that was camping out at a food station with nothing else left to feed on. The eucalypts had begun to push out lime-coloured epicormic shoots through blackened bark. Those that later formed leaves on these shoots displayed beautiful hues of green, crimson, and blue (Figure 3). The eucalypts themselves were not happy though, as epicormic growth from the trunk is a sign of stress.

Figure 3.

Eucalypts with epicormic shoots on the trunks, 14 February 2020. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

The part of the driveway which consists of dry sclerophyll forest on the lower, southern section was logged in the past, including evidence of old mine shafts, resulting in few large canopy trees. Val described such places that were used as extractive resources for logging, mining, hunting, or as general dumping grounds by humans as “shadow places”, both metaphorically and literally the southern, darker side of slopes in comparison to more valued lighter, northern slopes (Plumwood 2008a). This southern part of the forest on either side of the driveway is now legally protected as a continuation of Budawang National Park, through earlier work as a committee through negotiations with the Roads and Maritime Service.4 The higher and wetter temperate rainforest within the Plumwood Mountain section happened to escape being logged due to the steep escarpment and gullies, which means that the forest on the property remains more intact having retained large canopy trees, such as the dominant tall brown barrel (Eucalyptus fastigata).

I was shocked when we reached what we refer to as the “water meadow”, a part of the driveway that requires driving across a water crossing. Even during the previous couple of years of drought with the water no longer flowing as a stream, thick grasses grew on the edges, but they had become charred stumps. Upon returning a couple of months later, I was amazed to find murnong (or yam daisy, Microseris spp.), triggered to sprout after the fire and now thriving without the competition of the larger native grasses. I enquired about the growth of the murnong with a Walbunja elder, as yams were an important staple food source for Aboriginal communities. He agreed that the location of the water meadow would be ideal for the cultivation of yams, sheltered by surrounding embankments and situated near the escarpment.5 I could envisage Aboriginal families walking along the ridge of the escarpment with a view down to the South Coast, pausing to till, plant and harvest the murnong at the sheltered water meadow (before the land was demarcated by surveyors into separate private lots).

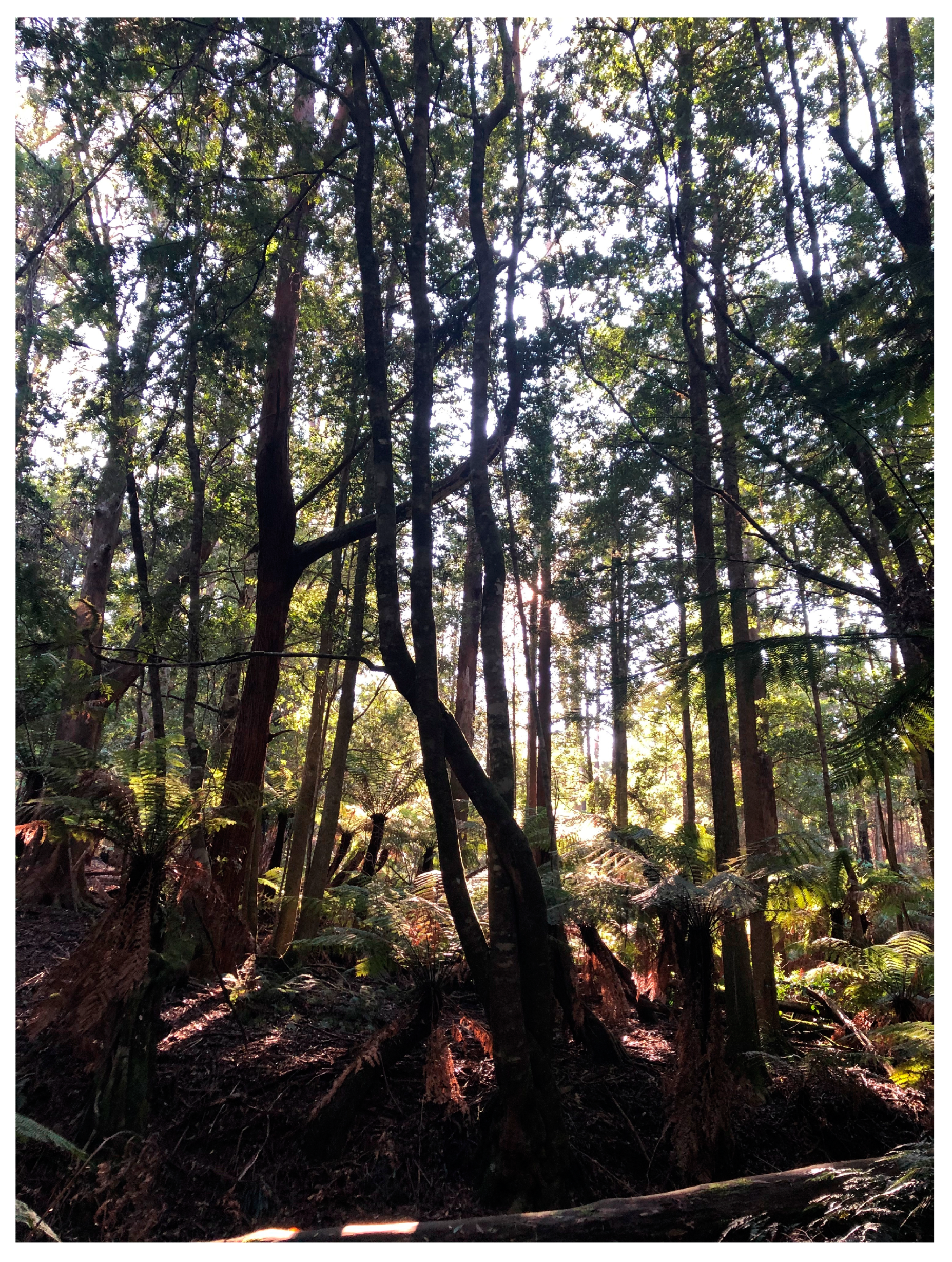

There is a point in the driveway that begins to markedly gain in elevation, where the soil lies on basalt rather than granite rock and the overlying vegetation changes to lush temperate rainforest. In the past, it was at this point that the track was often crowded in by protruding tree ferns. Evolutionarily, tree ferns are much older than flowering plants, such as eucalypts, as they date back to the Carboniferous era (300–360 million years ago) (Blair et al. 2017). Individual tree ferns may be older than the towering eucalypts above them, given that they too can live for more than 500 years. Previously I had misread tree ferns as fragile plants, relying on the moist temperate rainforest slopes through precipitation from the coast, yet they had survived and were responding vigorously after the fire. Vivid green shoots were unfurling from their amputated stumps (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fern unfurling from a burnt-out stump, 5 February 2020. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

In the midst of tall canopy trees, the driveway crosses a small gully, which becomes a flowing stream only in heavy rain, and with this dampness allows for a scattering of plumwood trees and tree ferns. The uniqueness of the plumwood trees is why the place is named Plumwood Mountain and why Val changed her surname to Plumwood. Val derived her philosophy from a place-based perspective that was intrinsically connected with Plumwood Mountain and the more-than-human beings she lived amongst, including individual plumwood trees.

Plumwoods can reproduce through seedlings, as well as in vegetative form. Seedlings may just sprout up from the ground but often germinate upon landing on the matted central area of a soft tree fern (Dicksonia antarctica) and then send a root down to the ground. With the plumwood’s roots exposed, entwined around the trunk of a tree fern, each grows to support the other. One plumwood may produce many trunks living on even after the initial mother tree has rotted back into the soil, allowing the genes of the same tree to keep growing for thousands of years. Val would take visitors to sit beneath one specific plumwood tree that she estimated had lived for over 3000 years.6 She identified with different individual plumwood trees and particular tree ferns, as they grow with distinctive forms and shapes, “quite different even from trees in close proximity which face similar life conditions. This one twines curvaceous, animal-like limbs around a tree fern, while its neighbour has a wrinkled, knobbly animal face like a possum” (Plumwood 2005a, p. 68) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Two individual tree ferns lying side by side, looking like a pair of pants. Even though the ferns had fallen over in the past, the leafy fronds are still growing, 29 July 2012. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

The fire had hungrily shot up the flammable bark of the large brown barrels, but it was a relief to see that the flames had only rarely reached the top of the canopy. Due to the smooth, mottled bark of the scattered plumwood trees, the fire had skipped over them, rather than lingering and devouring the trees. The lower tree ferns did not fare as well here, however, with one left as charred remains drooping over the still-living branch of a plumwood.

Charismatic superb lyrebirds (Menura novaehollandiae) live in this part of the forest. Plumwood Inc. has a small red four-wheel drive for carting tools and equipment up and down the driveway (removed from the property just before the fire swept through). As the vehicle would slowly bump along, a male lyrebird would often run across in front of the vehicle at a specific point in the driveway. I was looking out for him as we passed that point, but this time there was no familiar whistle or mimicking call produced by him.7 All was silent.

Once we reached the last section of the driveway, where the land only a few metres beyond drops precipitously down the escarpment towards the New South Wales coast, sentinel trees were standing as a mass of dead wood. In the two months of serious drought before the Black Summer fire season, the trees on the escarpment had already been struggling for water and would have easily caught alight with little moisture remaining in their limbs. The tree ferns had looked under stress from the drought too. Their usual glossy, bright green fronds had curled up and turned a russet brown—it must have been like a tinderbox waiting to happen before the fire swept through.

As we arrived at the clearing, I looked for what should have been the corrugated iron roof of the shed, but instead of the usual structure, there was now a tangle of warped metal. We walked around to investigate what had burnt and what was left. A 3500-L plastic water tank had burst from the heat of the fire on the eastern side, morphing into a mess of melted plastic with more emerging from the ground here and there like tangled spaghetti, what were once water pipes leading to the hexagonal stone cottage. Even the hard ironbark timber beneath the roof was still remarkably intact. We later surmised that the burst water tank may have saved the wooden surrounds of the house from catching alight. I felt exhausted from the rollercoaster of emotions, fluctuating constantly between hope and then despair.

4. Val’s Fire-Resistant Garden

In 1974, Val and her husband Richard Routley (who changed his surname to Sylvan, meaning “of the forest”) began to dwell in a simple shed and philosophise together in a clearing in the Australian bush. Australian author Jackie French became firm friends with Val when she moved into the district around the same time as a young adult. Jackie helped Val and Richard build a hexagonal cottage out of stone. Both Val and Jackie were part of the “back to the land” movement of the early 1970s; as feminists, they wanted to engage with their physical bodies and minds.8 Jackie described how Val would labour up the steep escarpment with stones in a backpack, while the practical artisanship of the stonemasonry for the walls was combined with lively discussion, written up by lamplight and sent off to form scholarly philosophical works (also see Mathews 2008, p. 318). In a short bio, Val described the topics of her writing as being about “animals, predation, gardens, ecology, forests and food ‘from the inside’, as a member of the food chain in a rich rainforest community of plants and animals near Braidwood” (Plumwood 2005a, p. 64) on Plumwood Mountain.

Val planted many different species of the native waratah (Telopea spp.) in her bush garden, a genus that produces huge flowers of brilliant red, yellow and white, including local Monga and Braidwood varieties (Figure 6). She tried to avoid invasive plants that would propagate in the surrounding bush and chose species that would be unpalatable to voracious wallabies, such as daffodils, while also selecting evergreen bushes that could act as a buffer against fire.

Figure 6.

Example of one of the huge waratah flowers that were a feature of the garden in the clearing. Image taken during a working bee two months before the fire, 11 October 2019. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

Val wrote of her “de-colonised interspecies garden” (Plumwood 2005b, p. 8):

I have a mixed garden of local, native and exotic plants that mediate the space around my dwelling, a stone house I built myself from local stone with fire survival in mind. Gardens provide much more than appearance, visual beauty, vegetables and flowers. Appropriate deciduous trees mediate climate—providing summer shade, winter sun, and above all, in this context, some fire protection for the house… My objectives are to live in a mutually beneficial relationship with my surroundings, a mixed human-nonhuman community, an interspecies project.

5. The Plumwood Committee

The conservation of Plumwood Mountain as a place stemmed from an active group of environmental and ecological humanities scholars. Between 2004 and 2008, as a PhD student at the Australian National University, I was part of an Ecological Humanities Group coordinated by Deborah Bird Rose and Libby Robin. A mentor for us all and an integral participant within the group was Val Plumwood, who unexpectedly passed away in February 2008.

By 2011, I had been missing the collegiality of the former ecological humanities group. George Main and I decided to organise an Ecological Humanities Gathering up at Plumwood Mountain. Anne Edwards had been informally mentored in environmental philosophy by Val. She began to live up at Plumwood Mountain after Val’s death, as Val indicated a wish for her to do so if anything happened to her. Anne, George and I subsequently became founding members of Plumwood, formed as an association in 2012 in order for a committee to function as stewards for the land on Plumwood Mountain (Figure 7). All initial members of the committee were engaged with the environmental (or ecological) humanities and Val’s philosophical writing, but also felt a connection with Val as a person. 9

Figure 7.

One of the early working bees held during winter up at Plumwood Mountain, 29 July 2012. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

What appealed to me about becoming involved with the Plumwood committee from the outset was that there would be no one individual “owner” of the land and efforts would be towards saving an ecosystem, where combined naturecultures could be nurtured. As a committee, we were all participating as stewards for Plumwood Mountain and the continuation of Val’s philosophical legacy (see, for example, Plumwood 1993, 2002, 2008a, 2008b, 2009).10 What is different about an approach towards conservation from a humanities-based perspective is that the focus is not only on a single species, or at a population level, but can be about the recognition of the agency of individual beings, whether a single impressive, ancient plumwood tree; an individual skink responding to a human playing music; or an individual human that has a deep connection with place, such as Val.

We knew of another property in nearby forested Mongarlowe, where Australian poet Judith Wright (a friend of Val’s) had set up cabins for visitors to write in a peaceful setting. She had gifted the bush property to a university in her will, but the university did not want the responsibility of managing it, so the property was sold off. We were concerned about the possibility of Plumwood Mountain being sold off privately too when it had been Val’s expressed wish to eventually turn the house and gardens into an educational space. Through the work of the committee, Plumwood Inc. took up the land title of the property in March 2014.

In 1996, Val was one of the first members of the public to sign a Voluntary Conservation Agreement (VCA) in New South Wales (the agreement for Plumwood Mountain was revised in 2002).11 As Val stated soon after she had formed the VCA (Prest 1997, p. 17),

I think the liberal Lockean concept of private property is pretty iniquitous—it always struck me when I came here—that the kind of power I was given over the place was inexcusable. I could raze the whole thing. But you can’t pick up an inch of soil here without it being occupied. You can see things squirming and jumping everywhere. The whole place is just packed and crammed with living things, and an incredible history of the earth. To think that I had the power to destroy it remains deeply shocking to me.

As Val emphasised during her lifetime, we need to recognise that we are part of an ecology and that we are not omniscient; the land is not just a resource for human habitation and consumption. The “reasons” for wanting to conserve the property, and the key aspects Val intended to abide by, were outlined in an appendix to a Plan of Management within the VCA:

These statements would have been forward-thinking environmentally for the time, particularly in Australian terms. Most VCAs are drawn up as legal documents with the accompanying government-oriented jargon that such agreements ordinarily contain. As a committee, we decided to establish Val’s “reasons” and “purposes” as underpinning tenets for what we were trying to achieve as stewards for Plumwood Mountain.

As Val’s intention was for Plumwood Mountain to work as an educational space, that became our intention too. Members of the committee had attended philosophy events that Val had organised, which included engaging outside with an open fire, singing and playing musical instruments. An important aspect of these gatherings for Val was that there was no division between theory and practice—environmental philosophy is to ideally be discussed outside, as a being in the world. With similar intentions, we coordinated a series of Plumwood Gatherings, where we featured speakers, such as John Blay (2015) and Dominic Hyde (2014).12

As a committee, we initiated an open access humanities journal, Plumwood Mountain: an Australian and international journal of ecopoetry and ecopoetics.13 Committee member Anne Elvey was Executive Editor of the journal and a driving force for the first few years. Each of us similarly brought our own engagement with the place, depending on our interests; mine was documentation through video or photographs (Fijn 2014, 2016), while George Main’s was the collection of material objects that belonged to Val as part of the development of a permanent environmental history exhibit at the National Museum of Australia.14 We wanted scholars to be able to spend time writing on topics relating to the environment up at Plumwood Mountain, so we set up a network of places where writers could stay, known as the Bush Retreats for Environmental Writers (BREW) Network.15 Just as Val had written some of her work at a forest desk with an impressive outlook through trees and down to the coast, humanities-based environmental writers could spend time engaging with both body and mind away from the pressures of an urban existence.

We wanted to work on restoring Aboriginal connections with Plumwood Mountain. One of the key locations for plumwoods in the region is high up on the eastern side of Mount Gulaga (Mount Dromedary) on the South Coast, a sacred mountain for the Yuin Nation. Through the separate stands of plumwood trees at these two locations, I could see the potential to establish a cultural link between the two places. Aboriginal communities are known to connect with individual trees through a structured totemic kinship relationship in connection with clan land (Merlan 1982).16 I invited an elder from the South Coast to come up to Plumwood Mountain, as she and her sister had coordinated workshops in the Braidwood area and had been teaching Dhurga language at the local primary school. This initial visit was fruitful, as she found evidence of stone tools from her knowledge of cultural heritage, indicating that her ancestors may have travelled along the top of the escarpment, perhaps using the clearing as a lookout point, using smoke to signal to family on the coast. The building of connections with Aboriginal community is a gradual process, however, as elders are often highly sought after for their cultural knowledge and community engagement.

There was a need for a separate space for writing residents, or for the caretaker to live in, that was separate from the communal space of the stone cottage. We spent a few weekends in 2019 holding working bees to renovate the dilapidated timber slab hut that Val and friends had originally built to house visitors. We spent many hours mixing a specific recipe of hemp with sand and lime and then hand-rendering the slurry onto the inside walls of the hut. The intention was that the insulating hemp render would make the hut warmer, but also allow writing residents to work in peace without encroaching native rats, venomous funnel-web spiders or snakes entering in the night. We just needed to put the finishing touches to the paint on the ceiling of the hut before the Black Summer fire season commenced.

I had also been in the process of setting up a separate multimedia residency in collaboration with PhotoAccess, a media arts organisation with a focus on photography, based in Canberra. As an extension of this initiative, I was about to run the first PhotoAccess “Forest Stories” course, including a field day up at Plumwood Mountain. I was driving back to my home in Braidwood from the ANU in Canberra toward the end of November 2019 when I could see that the Black Range was on fire (Greenwood 2019). A helicopter landed right near my car on the main highway, noisily scooping up water from a dam to drop on the fire front. I regretfully rang up PhotoAccess to cancel the field trip, as it would have been unsafe to have a group of enthusiastic photographers wandering around the Plumwood bush during high fire-risk conditions.

6. Renewal

I returned to Plumwood Mountain a couple of weeks after my first post-fire visit (Section 3) with a local ecologist who worked for the Biodiversity Conservation Trust (BCT), an organisation that supports conservation on properties, advising landholders regarding Voluntary Conservation Agreements. She came up with me to see how BCT could potentially support our recovery after the fires. I was also anxious to see how the Plumwood Gully had fared, as I had run out of time to explore the gully on the first visit.

Introduced plants that Val had intentionally planted had done their job in protecting the house and had initially survived, but without rain, they had curled up their leaves and were dying from stress. The garden looked bare without the usual moss and lichen, which had previously even covered the wooden seating in the usually moist-laden rainforest habitat. I was pleased to find some evidence of lyrebirds scratching in the garden and the tell-tale targeted digging of the little claws of long-nosed bandicoots (Perimeles nasuta) in search of highly venomous funnel-web spiders (Hadronyche spp.) that lived in trapdoors to one side of the slab hut.

Even though the fire had licked at the wooden posts of the newly renovated slab hut and had burnt down large tree ferns that were standing immediately adjacent to the hut, remarkably, the timber building that we had been working so hard on renovating was still standing. The fire had skipped around it, possibly because we had recently dug around the perimeter to provide airflow, and this could have acted as a narrow firebreak (Figure 8). Val’s planting of fire-resistant vegetation, including rhododendrons, camellias, and hydrangeas, in combination with a pool and moist concrete bowl filled with rushes that was once a pond, must have had a positive effect, as the vegetation in the clearing was still faring better than the surrounding forest. Val is buried near the stone cottage with her epitaph clearly inscribed in sandstone stating, “Having never been one for timidity”. I saw that a large skink that lived in the mound of stones forming the grave had survived. Leaves on the branches of waratahs that surrounded the grave had died, yet some hardy individuals had begun to sprout soft new shoots from their woody bases.

Figure 8.

The newly renovated timber slab hut and green garden beyond with all surrounding forest burnt, 26 January 2020. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

Val would often walk along the escarpment and sit at a lookout to take in the view down to the South Coast. The view down to the South Coast was no longer obscured by dense vegetation, but the scene was devastating, with hectares upon hectares of burnt-out forest as far as the eye could see. It was hard to contemplate such vast stretches of dead forest with all the accompanying insect, reptile, bird and marsupial lives that had been lost. While looking out over the escarpment amidst the burnt trees, it was eerily quiet with no sounds of birds or insects. Even the usual different species of leeches seeking out any exposed skin between socks and pants were strangely absent.

Once the fire had hungrily leapt up the steep slopes of the escarpment and burnt all the trees at the top, it was evident that the fire had begun to slow down and lose impetus as it proceeded down gentler terrain. The landscape looked so different without the dense vegetation. We donned government-issued hard hats to protect against falling limbs from above and periodically plotted where we were via Global Positioning System (GPS). When we reached the steep incline of the “fern tree disco”, where tree ferns look as if they are dancing at different angles, the fire must have skipped over the gully and moved on to the drier sclerophyll forest on the other side. I could see why Yolngu up in Arnhem Land perceive fire as animate and living, as it moves at different speeds of its own volition, with great power, eating up vegetation as it goes or even just feeding on the air as the fire grows in scale (also see Celermajer 2021).

The hidden gem that we were primarily focused on conserving, the Plumwood Gully, consists of sculptural trees formed from plumwoods entwined with tree ferns of all different shapes and forms that were miraculously still standing, just as they had done so for perhaps thousands of years. The Gondwanan haven had remained safe from the ravages of fire within the damp, steep gully, even though it had been so dry that the stream was no longer flowing, with only stagnant pools of water remaining (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The intact Plumwood Gully that escaped the fire, 14 June 2020. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

Val (Plumwood 2009, p. 21) had been very aware of the danger of fire and wrote of her relief when moisture and rain finally came after a period of drought:

The southern change really is Cool. Water trickles steadily into my rain tanks as cool moist cloud sweeps in from the ocean through the forest. I dig out a sweater; lyrebirds are singing again; grasses greening. All the fires around me now seem to be out. The dripping forest feels good now, but I know it’s not over yet until we get a lot more rain. It can all change back in a week or two of heat and drying winds into a fire powder keg. You have to be able to look at the bush you love and also imagine it as a smoking, blackened ruin, and somehow come to terms with that vision.

Although she did experience having to fight spot fires that occurred near the gate to the driveway, thankfully Val never had to live through the sight of her beloved forest as a blackened ruin. She had the foresight, however, to know that one day it would inevitably come.

7. From Fires to Flooding

Fire meant that there were big changes to the structure and composition of the forest up at Plumwood Mountain, but the event also resulted in fundamental cultural changes to the way Plumwood worked as a committee and as an organisation. We necessarily had to shift our mindset in relation to what we were trying to achieve. Our focus became less on keeping the place just as Val had lived her life up there and more on considering how Plumwood Mountain could be nurtured and sustained in the long term in the context of increasingly frequent extreme weather events.

By 2020, climate change was wreaking havoc. We had hardly recovered from the impact of the Black Summer fire when there were further extreme weather events, including hail and flooding in early 2020 (Lyons 2020). It felt apocalyptic. Amidst a transition to a La Niña weather system, which brought a release from the drought and fires, the weather transitioned to constant rain and flooding along the east coast of Australia. Thankfully, no one was residing in the stone cottage at the time fire swept through, but we now lacked amenities. I would mountain bike or walk up the driveway to check on the place. All the rain had rendered the driveway almost impassable to four-wheel-drive vehicles (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Hiking in with Amanda Stuart, another committee member, to check on the stone cottage during heavy rains in the region. The driveway turned into a stream or a muddy quagmire in places, 21 March 2021. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

Due to the surrounding understory being burnt with no remaining humus layer on the forest floor, the heavy rains formed temporary streams that ran down the escarpment, resulting in water spreading across the slate floor of the stone cottage, wetting the furniture and any books that were close to floor level. I dug an emergency ditch in the rain to re-direct water from flowing through the front door. With all the moisture in the air, the house was damp and became covered in a layer of mildew and spores.

The New South Wales government was assisting properties in recovery after the fire by bringing in contractors to clean up burnt debris. A truck with workers came up the driveway to remove the contents of the burnt-out shed, but the team became stuck in the mud and churned deep gouges into the fragile surface of the already eroded driveway. Although the unprecedented rain was difficult in relation to maintaining human infrastructure, it was a blessing for the regeneration of the forest after the fire. Watering stations for the animals were no longer necessary. Wallabies and wombats could find fresh new picks. Every time I proceeded up the eroded track, I would feel heartened by the remarkable recovery of the understory and how quickly the scorched forest floor became covered in green shoots.17

The devastating fire and flooding became compounded by the growing impact of the coronavirus pandemic, a product of what Val termed a “crisis of reason” in our relationship with “nature” (Plumwood 2002), in the form of industrialised agriculture, the trading of wildlife across international borders and human travel around the globe, with the complex anthropogenic impact being virulent new strains of viruses. Through our environmental humanities grapevine, Ruby Kammoora and Clancy Walker heard that we were seeking an individual or couple to live as caretakers up at Plumwood Mountain. They had been living in Melbourne in lockdown at the time, but in a reprieve of cases, they were visiting family in the area and came to have a look at the place. Despite the blackened stands of trees and a lack of running water due to the fire, the couple were keen to switch focus from larger-scale environmental projects to working with a grassroots organisation.

Before we could have caretakers living up at Plumwood Mountain, however, we needed to re-install a long-drop toilet, four water tanks and plumbing; replace the guttering on the roof to prevent water from entering the stone cottage; and install a larger solar unit on the roof, all of which was facilitated by the organisation of small working bees. After Ruby and Clancy took up the role as caretakers in mid-2020, they set to work re-establishing parts of the burnt-out garden, building a tool shed and a glasshouse that could also function as a bathroom. As we were concerned about the state of the books and materials in the cottage due to the moist air, members of the committee salvaged and documented Val’s extensive library of books on environmental philosophy, feminism, natural history and sustainable ways of living.

Plumwood Mountain, along with five other properties in the local area that are also under VCAs, obtained funding through the Biodiversity Conservation Trust to bring in ecological consultants to survey for the presence of keystone species, such as forest owls and greater gliders. We could then gain some baseline data regarding how these species had fared after the fire. The ecology team conducted night surveys and found that the five bush properties were providing important habitat for forest owls and gliders, despite the impacts of fire. Plumwood Mountain had retained some medium- to large-sized canopy trees, providing important habitat for a population of greater gliders (Petauroides volans) and the Southern boobook owl (Ninox boobook).18

As a committee, we wanted to promote new and original research across the humanities and sciences, so welcomed postgraduate students to conduct research up at Plumwood Mountain. Ecology honours and doctoral students that were part of Team Quoll from the University of Wollongong came up to Plumwood Mountain to stay in the renovated slab hut, while conducting night surveys on the property and within Monga National Park. One of the postgraduate students communicated to the committee that he had spotted 40 greater gliders along the driveway in one night, which was the highest abundance across any of the burnt areas he had surveyed (May-Stubbles 2021). He indicated that the unburnt Plumwood Gully may have been functioning as an important refuge for greater gliders that had migrated from more severely burnt areas (May-Stubbles pers. comm.).

It was heartening to discover through this ecological surveying that although the understory of the forest had largely been burnt, the bush was providing habitat for threatened species of marsupials. An article came out just after the catastrophic bushfire season (McGregor et al. 2020). Through genetic analysis, the authors found that the greater glider species in Australia consist of three separate species, rather than one species with different colour morphs. This means that greater gliders are under greater threat than previously thought, with an estimated 80% loss of the overall population after much of their habitat burnt down within a few short weeks (Knipler et al. 2023). Previously, my focus had been on the plumwoods and accompanying tree ferns as an important example of a remnant Gondwanan age population existing in New South Wales, but through the ecological surveys after the fire and the new science regarding the genetics differentiating species, it was evident that Plumwood Mountain is also an important habitat for endangered greater gliders.

After a lot of time and energy put in by members of the committee, Plumwood Mountain was listed on the State Heritage Register (New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment 2023), in recognition of its unique natural and cultural heritage. With the property legally demarcated as a Wilderness Area as part of the Voluntary Conservation Agreement established by Val, this additional layer of protection for the house and gardens as part of a heritage register legally ensures that humans cannot exploit Plumwood Mountain for its resources or for monetary gain in the future, requiring notoriously disruptive humans to tread lightly upon the land. Protection of place through legal forms of non-interference is an effective conservation humanities approach through an ethic of custodianship and stewardship.

8. Country and Cultural Burning

Mega-fires, such as the Currowan fire, are so powerful that they form their own weather system. In January 2020, I could see an ominous-looking cumulonimbus, an anvil-shaped smoke cloud, from 40 km away. The cloud formation meant that the northern side of Monga National Park was being destroyed by a “hot burn” and there were no human resources available to save it. In contrast, Aboriginal communities have been managing fire on the continent of Australia for thousands of years (Gammage 2012). Through long-held cultural knowledge, individuals with a connection to Country in the Northern Territory light fires to decrease the build-up of fuel on the ground. Unlike “hot burns”, these “cool burns” allow for the regeneration of the forest. If performed seasonally, cool burns also help to avoid huge fires that become intensely hot and out of control (Gammage and Pascoe 2021).

Walbunja are a self-identified Aboriginal clan that are part of the larger Yuin Nation on the South Coast of New South Wales. Walbunja lands are concentrated around the Batemans Bay Area, including the escarpment that extends up to Plumwood Mountain. The local RFS and individual “mozzies”, equipped with a tank of water and a hose on a ute, spent weeks putting out spot fires at Mongarlowe near Braidwood. The Mongarlowe community wanted to try different techniques to mitigate against further devastating fires that they had experienced during the Black Summer fire season. With Upper Shoalhaven Landcare, they invited Walbunja elders and rangers to demonstrate cultural burning practices on the land (New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment 2022).

By 2022, Affrica Taylor had taken up the role as president of Plumwood Inc., after my stint as president managing one extreme climatic event after another. Affrica, having worked with Indigenous communities on the ground and in academia for over thirty years, wanted to promote further Indigenous engagement.19 Affrica invited the Walbunja rangers to connect with Plumwood Mountain. The lead Walbunja ranger identified significant cultural aspects, such as medicinal and edible plants up on Plumwood Mountain. The ranger team subsequently came up to Plumwood Mountain for conservation purposes, installing remote sensing cameras to monitor for the presence of different species, including feral animals, while training young rangers as part of a tertiary qualification. In terms of surveying wildlife, Walbunja took a minimum intervention approach, in keeping with the committee’s ethics towards the surveying of species on the property. Over a series of meetings, committee members discussed the ways we could engage further with Walbunja and how we could redress some of the harm done by previous generations of settler Australians in the denial of land rights to First Australians. Walbunja elders were subsequently invited up to Plumwood Mountain. From the outset, it was clear that there was strong potential for collaboration and that we were on the same page in terms of stewardship and conservation of the land.

9. Conclusions

Thousands of hectares of bushland and all the accompanying unique biodiversity were lost over only a few short weeks during the Black Summer fires of 2019–2020. The Australian public became viscerally aware of the impact and scale of a changing climate and its potential to wreak havoc. There is, however, a lack of monetary input by the Australian government into the conservation of biodiversity on government land, with very few rangers employed on the ground in national parks. This lack of funding became particularly evident during the catastrophic bushfires and the aftermath of the devastation for wildlife communities. Emergency feeding and watering of wildlife occurred only due to the on-the-ground efforts of dedicated volunteers. The government has outsourced the conservation of land, relying on organisations to apply for specific grants and funding. There is, therefore, a need for grassroots community groups, or landholders, to put time and energy into conserving tracts of land and to ensure that there is protection through legal frameworks. On an individual level, a person can come to know a place well and can work toward nurturing species as part of a whole ecosystem, as Aboriginal custodians have done over many generations on clan lands (Altman and Kerins 2012).

As Deborah Bird Rose wrote (Rose 2013, pp. 95–96), regarding Val’s philosophical form of animism that she was advocating toward the end of her life,

Val understood that Aboriginal Australians always live within a world that is buzzing with multitudes of sentient beings, only a very few of whom are human. She thought that a good way to start up a major cultural rethink would be to talk with people who are now living within the kinds of understandings we are seeking.

Working in a mode of inclusion, she explored the significance of Indigenous knowledge today and the kinds of adaptations we would all need to make to engage ethically with contemporary globalised earth systems, including climate change, mitigation and exchange.

We are initiating a “cultural rethink” through the Plumwood committee’s collaboration with Walbunja rangers. When I described Val’s philosophy towards Plumwood Mountain with Walbunja elders, of her ideas regarding the need to break down the divisions of nature and culture and the importance of not only theoretical but practical forms of learning, individual elders responded immediately to this non-dualistic philosophy, in keeping with their own cultural underpinnings and connection to Country.

Since Val’s death, the role of the stewardship of Plumwood Mountain as a place has not been held by just one person, or “owner”, but by a dedicated group of people, largely humanities-oriented, with similar environmental ethics. Conservation humanities as part of a broader environmental humanities can offer an alternative to mainstream models of conservation, engaging in a different form of stewardship that does not involve anthropocentric forms of private land ownership, or a dichotomy between reserves set aside for “nature”, quite separate from humans immersed in “culture” (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Regenerating ferns up at Plumwood Mountain less than a year after the fire, demonstrating the resilience and adaptiveness of the Australian bush, 15 November 2020. Photo: Natasha Fijn.

As a committee, Plumwood will continue to care for and manage the buildings within the clearing, including the heritage-listed stone cottage and regenerating garden, with Val Plumwood’s philosophical legacy in mind. Walbunja rangers intend to employ Indigenous land practices on the land, as a means of managing invasive species and conserving biodiversity, including cultural burning of the re-emerging sclerophyll understory through cool burns. The Plumwood committee intends to continue residencies, workshops and working bees. In the future, this will involve ongoing collaboration with Walbunja, enabling the use of established infrastructure as an education hub in the promotion of conservation, Indigenous knowledge practices and in caring for Country.

Funding

The research into this article received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the Walbunja and the broader Yuin Nation as traditional custodians of the land on which Plumwood Mountain stands and pay respect to elders past and present, as well as acknowledgement of their totemic connection with more-than-human kin. Thank you to Affrica Taylor for her particularly insightful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Anne Edwards, Ruby Kammoora and Clancy Walker have been particularly instrumental up at Plumwood Mountain, as live-in caretakers of the land. I would also like to acknowledge the people who have not been individually named within this article, who have invested time and energy into the nurturing of Plumwood Mountain as a place.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For a podcast recording of a six-part radio documentary, The Heart of the Storm, focusing on the effects of the bushfires in the Braidwood area, see (Young and Ricketson 2023). |

| 2 | For footage of the out-of-control mega-fire storm from the Currowan fire, see (Fire and Rescue NSW 2020). |

| 3 | The fire that engulfed Plumwood Mountain caused havoc for residents and summer holidaymakers along the South Coast of New South Wales; see https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6575661/the-currowan-fire-a-monster-on-the-loose/, uploaded 11 January 2020 (accessed on 2 November 2023). |

| 4 | See my photo essay in Landscape journal, which draws on Val’s concept of a “shadow place” (Fijn 2016). |

| 5 | I also asked naturalist John Blay about the sprouting of the murnong, as he has written of locating murnong cultivation sites along the old Aboriginal trail, The Bundian Way, which starts from the South Coast and goes all the way to the snowy mountain ranges (Blay 2015). There is also an ancient trail near Plumwood Mountain, known today as The Corn Trail, an old Yuin route up the escarpment. Before the Kings Highway was built, it was used by early settlers to transport goods from the gold mining town of Braidwood onto ships at Nerriga, a river port near the coast (see Coombe 2020). |

| 6 | Val wrote that botanists have estimated that plumwoods can live for 3000–5000 years (Plumwood 2005a, p. 66). |

| 7 | Eleven lyrebirds were seen gathering around a dam to escape an impending fire during the devastating Black Summer, posted January 30. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-01-30/lyrebirds-band-together-to-avoid-approaching-bushfire/11910666 (accessed on 3 November 2023). Lyrebirds must have a good mental map of their surrounding habitat, an adaptive strategy to avoid fires by seeking out water. |

| 8 | See a filmed conversation between Jackie French, George Main and me (behind the camera), recorded as material for the Val Plumwood Collection at the National Museum of Australia: “Jackie French, on Philosopher Val Plumwood” https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/182186312, uploaded 9 September 2016 (accessed on 3 November 2023). |

| 9 | The Plumwood committee initially comprised Anne Edwards, Deborah Bird Rose, Freya Mathews, Kate Rigby, Anne Elvey, George Main and me. Lara Stevens (currently a member of the committee) and colleagues edited a book, “Feminist Ecologies: changing environments in the Anthropocene”, which included influential Australian eco-feminist scholars as contributors, many of whom also made up the initial Plumwood Inc. committee, including Freya Mathews, Kate Rigby, Deborah Bird Rose and Anne Elvey, and a posthumous chapter on ecological denial written by Val (Stevens et al. 2017). |

| 10 | As an undergraduate in an ecology course, I went on a field trip to Hinewai Reserve on Banks Peninsula in New Zealand. I was inspired by Hugh Wilson’s explanation of his “minimum interference” approach to conservation, implemented through the establishment of a Trust (see Wilson 1994). There is a film about Hugh Wilson and his dedication to Hinewai Reserve (Osmond and Wilson 2019). I was inspired by Val’s writing on the avoidance of human exceptionalism, including her article “being prey” (Plumwood 1995), where she describes what went through her head while being attacked by a crocodile. Her work informed my multispecies research on Yolngu connections with significant totemic beings, particularly kinship with the saltwater crocodile in Arnhem Land, the Northern Territory (Fijn 2013). |

| 11 | “Land subject to variation of a Voluntary Conservation Agreement between the Minister for the Environment for the State of New South Wales and Valerie Plumwood for Plumwood Mountain”, dated 2002. |

| 12 | Dominic Hyde wrote a book on the philosophical lives of Richard Routley and Val after their deaths (Hyde 2014). |

| 13 | See https://plumwoodmountain.com/ for ongoing ecopoetry contributions (accessed on 3 November 2023). I contributed a photo essay in an early volume of the journal (Fijn 2014). |

| 14 | One of the significant pieces that was added to the collection at the National Museum of Australia was the canoe that Val had been paddling when she was attacked by a crocodile and survived in 1986; see https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/collection/highlights/val-plumwood-canoe (accessed on 3 November 2023). George Main collaborated with artist Vic McEwan, drawing on the concept of shadow places, exhibited at the Powerhouse Museum in 2016; see https://www.cadfactory.com.au/shadow-places-sydney (accessed on 3 November 2023). |

| 15 | See https://thebrewnetwork.org/properties/ (accessed on 3 November 2023). |

| 16 | Danielle Celermajer (2021) writes of how she named an ancient individual tree on her rainforest property after her grandfather, as both his memory and the tree remind her that it is important to consider future generations and how they will survive on the land. |

| 17 | I documented the regeneration of the forest after the fire, juxtaposing black-and-white images with my grandfather’s photographs from 75 years earlier. He documented recovery after the destruction of Maastricht at the end of World War II. See a digital record of the exhibition at https://www.gallery.photoaccess.org.au/between-hope-and-despair (accessed on 3 November 2023). |

| 18 | Umwelt Environmental and Social Consultants. Report, 2020. “Post-fire ecological survey: Plumwood, Monga NSW”, a survey funded by Biodiversity Conservation Trust, NSW. |

| 19 | Affrica Taylor and Leslie Instone (who was also a friend of Val’s) describe how they negotiated living with a multispecies community in this era of the Anthropocene on a different conservation reserve in the highlands of New South Wales (Instone and Taylor 2015). |

References

- Altman, Jon, and Seán Kerins. 2012. People on Country: Vital Landscapes Indigenous Futures. Annandale: Federation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, David P., Wade Blanchard, Sam C. Banks, and David B. Lindenmayer. 2017. Non-linear growth in tree ferns, Dicksonia antarctica and Cyathia australis. PLoS ONE 12: e0176908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blay, John. 2015. On Track: Searching out the Bundian Way. Sydney: NewSouth Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Celermajer, Danielle. 2021. Summertime: Reflections on a Vanishing Future. Brisbane: Penguin Random House Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Coombe, Zoë. 2020. Plumwood. In An A to Z of Shadow Places Concepts. Shadow Places Network. Available online: https://www.shadowplaces.net/concepts (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Fijn, Natasha. 2013. Living with crocodiles: Engagement with a powerful reptilian being. Animal Studies Journal 2: 1–27. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/asj/vol2/iss2/2 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Fijn, Natasha. 2014. Photo essay: Impact on the Kings Highway. Plumwood Mountain Journal. Available online: https://plumwoodmountain.com/multimedia-gallery/photo-essay-by-natasha-fijn/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Fijn, Natasha. 2016. A shadow place: Plumwood Mountain. Landscapes: The Journal of the International Centre for Landscape and Language. 7. Available online: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/landscapes/vol7/iss1/12/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Fire and Rescue NSW. 2020. Burnover: The Full Story. July 28. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCTthdcH1Co (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Gammage, Bill. 2012. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Gammage, Bill, and Bruce Pascoe. 2021. Country: Future Fire, Future Farming. Melbourne: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, Martin. 2019. North Black Range Fire—Braidwood. December 1. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KRI4wy5PtwA (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Hyde, Dominic. 2014. Eco-Logical Lives: The Philosophical Lives of Richard Routley/Sylvan and Val Routley/Plumwood. Cambridge: White Horse Press. [Google Scholar]

- Instone, Leslie, and Affrica Taylor. 2015. Thinking about inheritance through the figure of the Anthropocene, from the Antipodes and in the presence of others. Environmental Humanities 7: 133–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Knipler, Monica, Ana Gracanin, and Katarina M. Mikac. 2023. Conservation genomics of an endangered arboreal mammal following the 2019–2020 Australian mega-fire. Scientific Reports 13: 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, Kate. 2020. Bushfires, Ash Rain, Dust Storms and Flash Floods: Two Weeks in Apocalyptic Australia. January 24. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/jan/24/bushfires-ash-rain-dust-storms-flash-floods-two-weeks-in-apocalyptic-australia (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Mathews, Freya. 2008. Vale Val: In memory of Val Plumwood. Environmental Values 17: 317–21. Available online: http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/6040 (accessed on 3 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- May-Stubbles, Jarrah C. 2021. The Short-Term Effect of Fire Severity on Arboreal Mammals. Unpublished Honours Thesis, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Denise C., Amanda Padovan, Arthur Georges, Andrew Krockenburger, Hwan Jin-Yoon, and Kara N. Youngentob. 2020. Genetic evidence supports three previously described species of greater glider, Petauroides volans, P. minor, and P. armillatus. Scientific Reports 10: 19284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlan, Francesca. 1982. A Mangarrayi representational system: Environment and cultural symbolization in northern Australia. American Ethnologist 9: 145–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment. 2022. Healing Country and Community with Good Fire Practices. July 14. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aGevsle_J_o (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- New South Wales Department of Planning and Environment. 2023. Uploaded May 11. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/news/plumwood-mountain-added-to-nsw-state-heritage-register#:~:text=Plumwood%20Mountain%2C%20the%20remote%20120,the%20NSW%20State%20Heritage%20Register (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Osmond, Jordan, and Antoinette Wilson. 2019. Fools and Dreamers: Regenerating a Native Forest. July 28. Available online: https://happenfilms.com/fools-and-dreamers (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Plumwood, Val. 1993. Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, Val. 1995. Human vulnerability and the experience of being prey. Quadrant 39: 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, Val. 2002. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, Val. 2005a. Monga Magic: A trip to Gondwanaland. In Monga Intactica: A Celebration of the Monga Forest and Its Protection. Edited by Robyn Steller. Burwood: BPA Print Group. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, Val. 2005b. Decolonising Australian gardens: Gardening and the ethics of place. Australian Humanities Review 36: 1–9. Available online: https://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2005/07/01/decolonising-australian-gardens-gardening-and-the-ethics-of-place/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Plumwood, Val. 2008a. Shadow places and the politics of dwelling. Australian Humanities Review 44: 139–50. [Google Scholar]

- Plumwood, Val. 2008b. Tasteless: Towards a food-based approach to death. PAN: Philosophy, Activism, Nature 5: 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumwood, Val. 2009. Nature in the Active Voice. Australian Humanities Review 46: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prest, James. 1997. Plumwood Mountain. National Parks Journal 12: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Deborah Bird. 2013. Val Plumwood’s philosophical animism: Attentive inter-actions in the sentient world. Environmental Humanities 3: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Lara, Peta Tait, and Denise Varney. 2017. Feminist Ecologies: Changing Environments in the Anthropocene. New York: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Hugh. 1994. Regeneration of native forest on Hinewai Reserve, Banks Peninsula. New Zealand Journal of Botany 32: 373–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Claire, and Rose Ricketson. 2023. Heart of the Storm. Braidwood: Braidwood FM. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100087772132710 (accessed on 6 November 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).