Social Changes in America: The Silent Cinema Frontier and Women Pioneers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

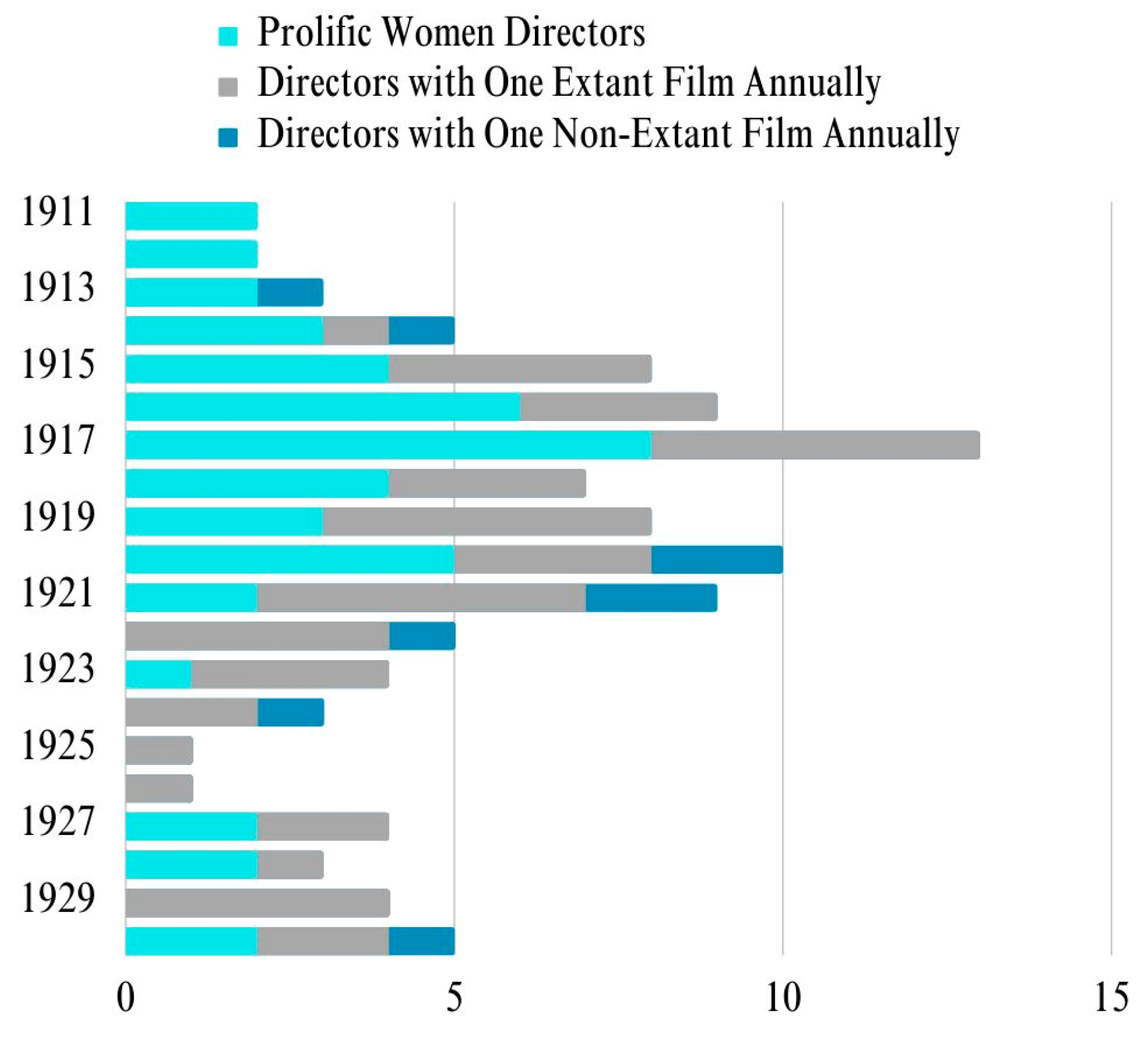

2.1. Women Pioneers

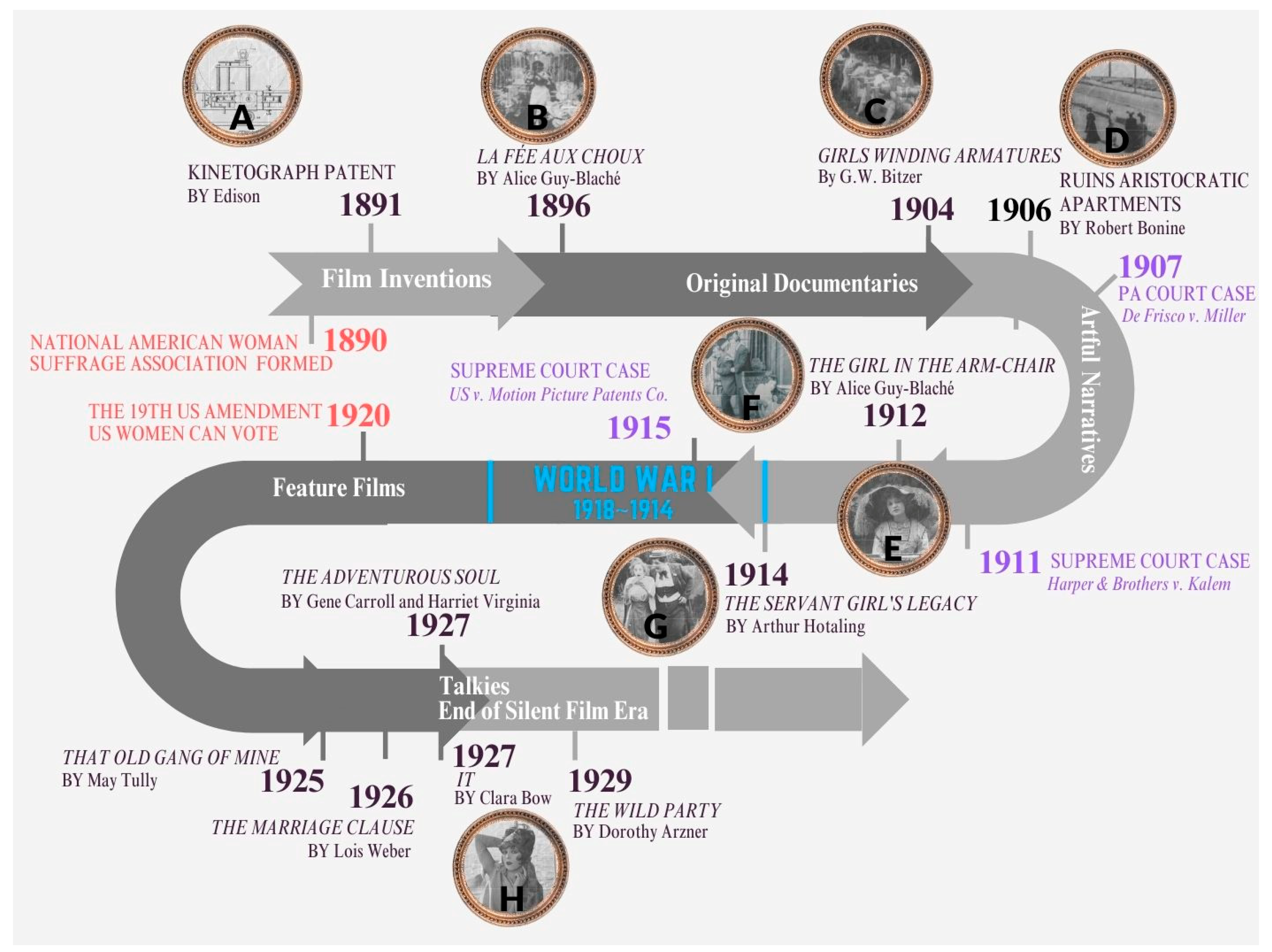

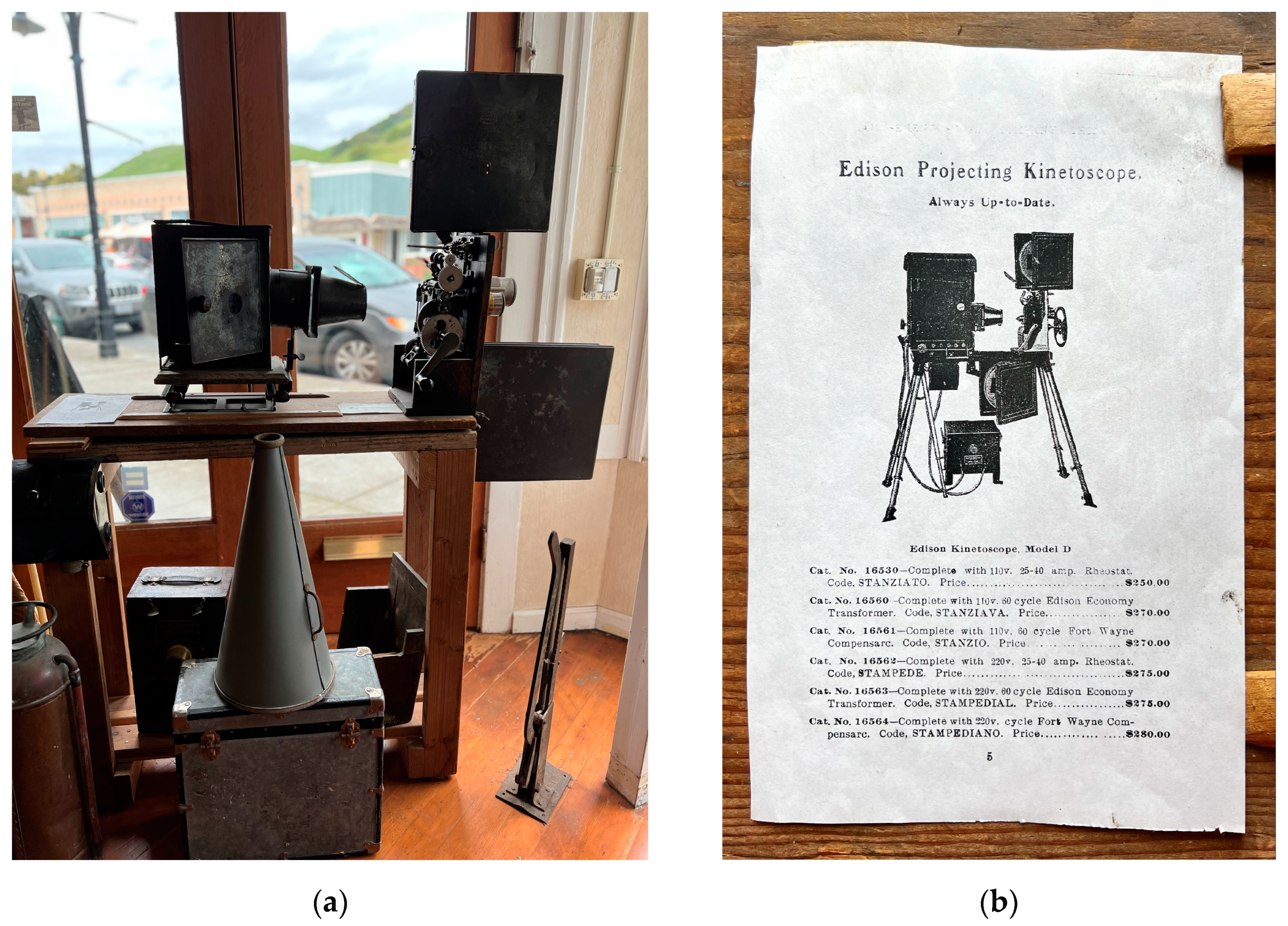

2.1.1. Women and Technological Innovation

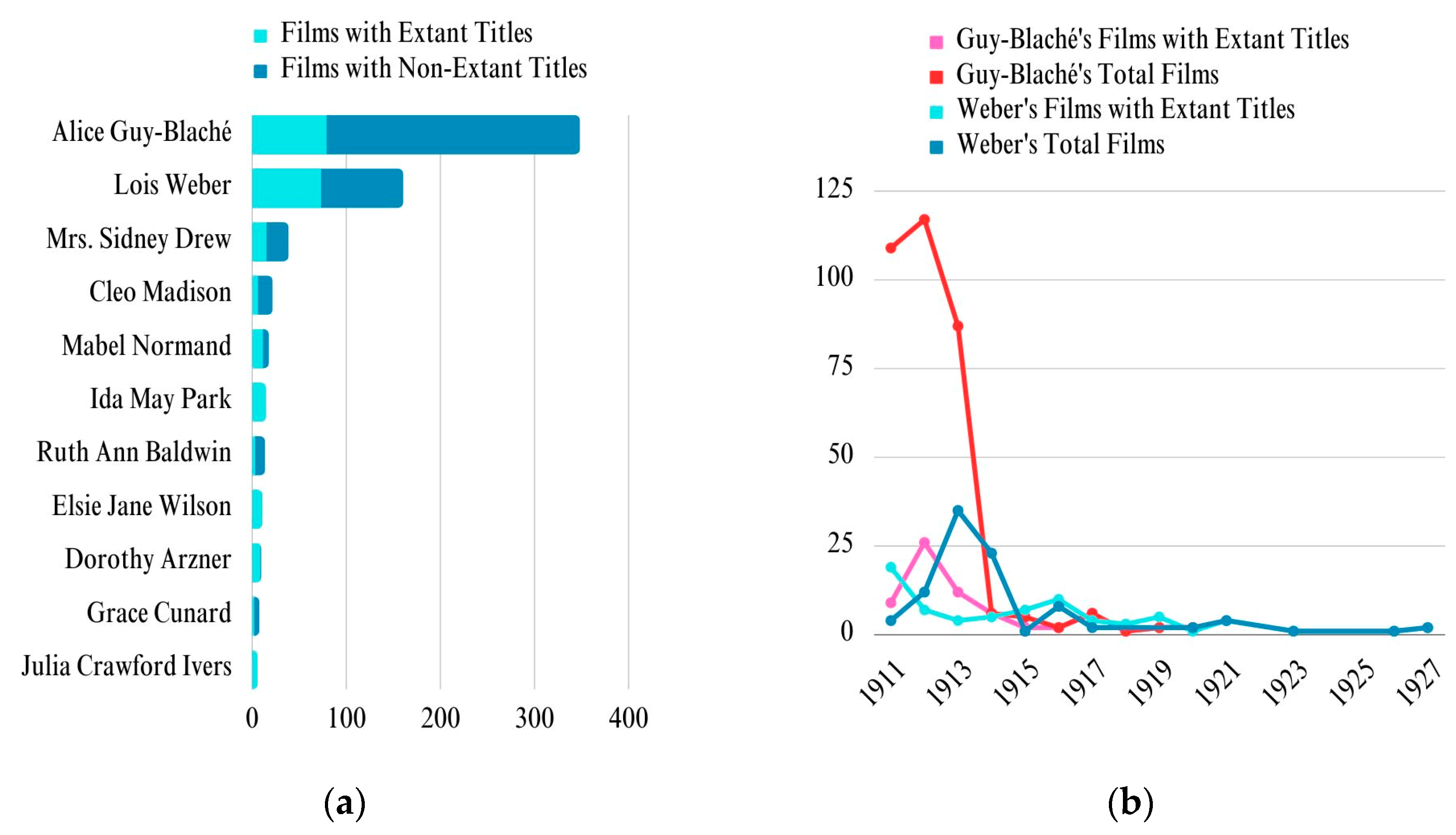

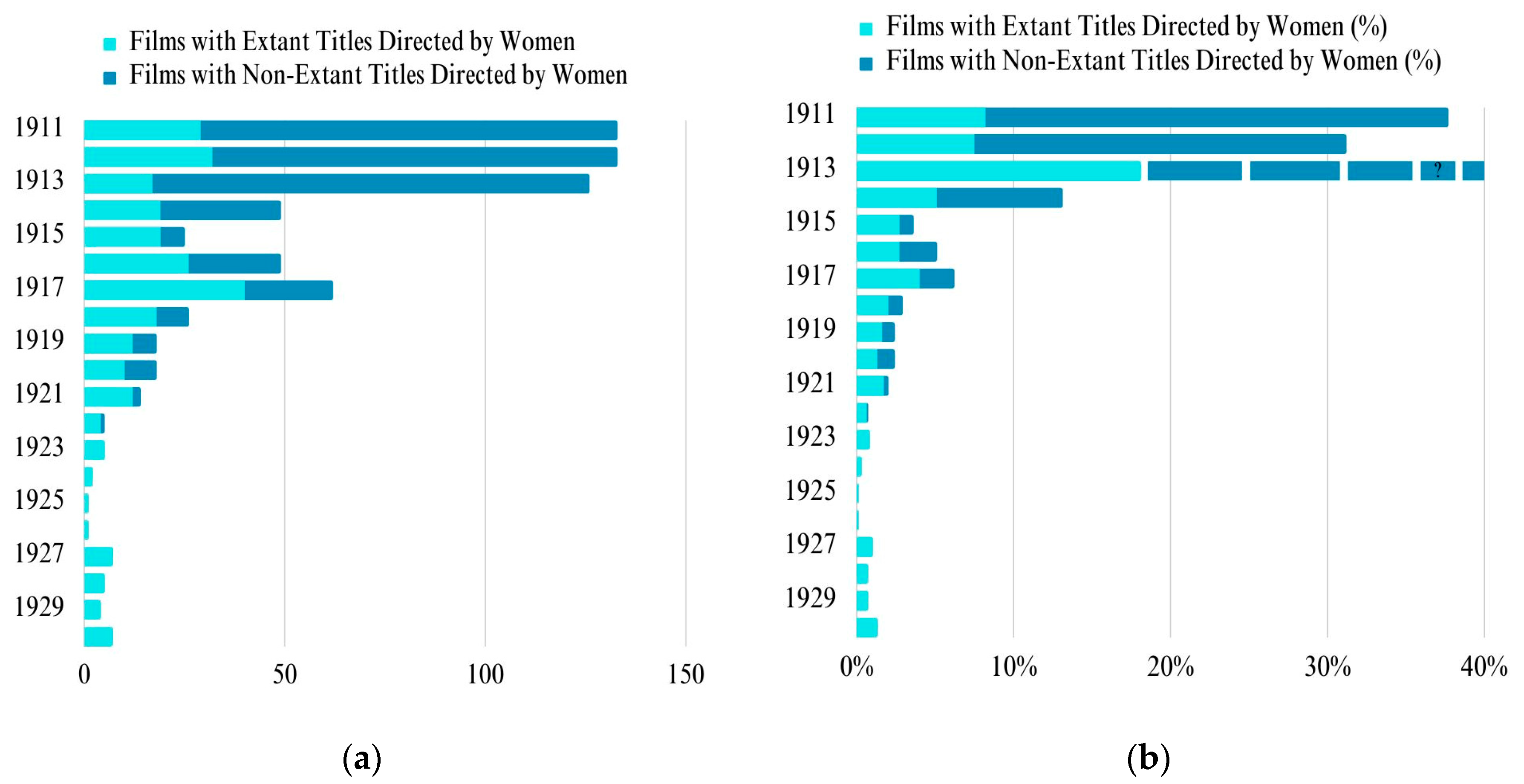

2.1.2. Women Directors

2.1.3. Women Screenwriters and Producers

2.1.4. Women Musicians and Artists

2.1.5. Actresses

2.1.6. Female Audience

2.2. What Happened to Women Directors and Screenwriters?

2.2.1. No Women Directors in 1925?

2.2.2. Alice Guy–Blaché’s Films (1911–1913)

2.2.3. Over by 1925?

2.2.4. Films Written by Women

2.3. Women’s Portrayal in Silent Films

2.3.1. Women in Documentary-Style Silent Films

2.3.2. Women in Artful Narratives

2.3.3. Women in Feature Films

3. Discussion

3.1. Women Filmmakers and Silent Film History

3.2. Traditional Gender Roles vs. the “New Women”

3.3. Marginalized Communities

3.3.1. Deaf Community

3.3.2. Racial Discrimination

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Lost Films

4.2. Women Director Dataset (1911–1930)

4.3. “Films Written by a Women” Dataset (1924–1928)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abadie, Alfred C., dir. 1903. The Great Fire Ruins, Coney Island. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 2:58, posted by King Rose Archives. 24 September 2013. Available online: https://youtu.be/kTo6caZOO1Q?si=ZMhfGojvQ8WrJxrB (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Acker, Ally. 1991. Real women directors. In Real Women: Pioneers of the Cinema 1896 to the Present. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, pp. 7–20. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282270093779200 (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- American Film Institute. 2023. Available online: https://aficatalog.afi.com/ (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Anderson, Mark Lynn. 2013. Dorothy Davenport Reid. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, Frederick, dir. 1899. Her First Cigarette. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 0:34, posted by Films by the Year, 8 June 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/2lTlbRgnTAU?si=uhPYp398Y90glaSo (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Asselin, Kristine Carlson. 2015. Women in World War I. Minneapolis: An Imprint of Abdo Publishing, p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Azlant, Edward. 1997. Screenwriting for the early silent film: Forgotten pioneers, 1897–1911. Film History 9: 228–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, Gregg P. 1995. The Last of the Silent Generation: Oral Histories of Silent Movie Patrons. Ph.D. dissertation, The Union Institute, Cincinnati, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, Elizabeth. 2010. More Than Your Nickel’s Worth: The Nickelodeon. University Park: Pennsylvania Center for Books. Available online: https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/feature-articles/more-your-nickels-worth-nickelodeon (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Bean, Jennifer M. 2013. Grace Cunard. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, Cari. 1997. Without Lying Down: Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 475. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, Harry, dir. 1923. The Gold Diggers. Burbank: Warner Bros, Studio. Video, 57:14, posted by JC Projections. 3 June 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/yg54vN--mLA?si=s3oQLC_s5-XJWSBv (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Beaumont, Harry, dir. 1928. Our Dancing Daughters. Performances by Joan Crawford. 2010. Burbank: Warner Bros, DVD. [Google Scholar]

- Berri, Maud Lillian, dir. 1917. Glory; American Film Institute Catalog. Available online: https://catalog.afi.com/Film/14573-GLORY?sid=bce7ef6b-8585-437f-ae81-5a725f1bd443&sr=5.0299187&cp=1&pos=0 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Bitzer, Gottfried Wilhelm, dir. 1904a. Girls Taking Time Checks. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 2:26, posted by Films by the Year. 27 March 2023. Available online: https://youtu.be/vN9RqE9Sn3E?si=30SpoNaYtwmSZ3D (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Bitzer, Gottfried Wilhelm, dir. 1904b. Girls Winding Armatures. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 1:35, posted by Films by the Year. 30 December 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/as8tsnke4uc?si=1zImkmqkjqpaWlVo (accessed on 7 July 2023).

- Bitzer, Gottfried Wilhelm, dir. 1906. Married for Millions. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 1:35, posted by Films by the Year. 8 June 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/L-wa05bTGz8?si=Aw8YIZnUuwWzByFi (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Blaché, Simone. 2022. Epilogue. In The Memoirs of Alice Guy Blaché. Edited by Anthony Slide. Translated by Roberta Blaché, and Simone Blaché. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., p. 104. First published 1986. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The+Memoirs+of+Alice+Guy+Blaché&author=Slide,+Anthony&publication_year=2022 (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Bonine, Robert K., dir. 1906a. Earthquake Ruins, New Majestic Theatre and City Hall. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 0:34, posted by Films by the Year. 17 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/Q4hArPO9p7w?si=7zY5bI2QkhyYz_72 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Bonine, Robert K., dir. 1906b. Panorama, City Hall, Van Ness Avenue and College of St. Ignatius. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 0:52, posted by Films by the Year. 19 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/wMopjyh1gPM?si=B7KQL9QxMrggdK1H (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Bonine, Robert K., dir. 1906c. Panorama, Nob Hill and Ruins of Millionaire Residences. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 0:44, posted by Films by the Year. 21 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/IIN3Wzk8lzA?si=twzOO9BLuuyxjbDt (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Bonine, Robert K., dir. 1906d. Panorama, Notorious ‘Barbary Coast’. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 0:48, posted by Films by the Year. 22 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/cXBYqwoZSK4?si=JF9ih--i0poqF8qq (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Bonine, Robert K., dir. 1906e. Panorama, Ruins Aristocratic Apartments. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 1:04, posted by Films by the Year. 23 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/fnsOx6x2X0I?si=pMUDBUIdD9UpSjpa (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Bonine, Robert K., dir. 1906f. Ruins of Chinatown. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 1:02, posted by Films by the Year. 24 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/Pnr8MojTTGs?si=TXWL-kSbDAQwZgff (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Bradley, Dorothy. 2023. In-person interview by the author. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlow, Kevin. 2005. Annus mirabilis: The film in 1927. Film History 17: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, Jack, dir. 1921. A Daughter of the Law; American Film Institute Catalog. Available online: https://catalog.afi.com/Film/3640-A-DAUGHTEROFTHELAW?sid=0bcdb8bd-bb2d-4dcb-8235-2eae1cf967aa&sr=9.422932&cp=1&pos=0 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Crosland, Alan, dir. 1927. The Jazz Singer; Amazon Prime Video. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Jazz-Singer-Al-Jolson/dp/B00KVWH04G (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Dickson, Antonia. 1895. Wonders of the Kinetoscope. Leslie’s Monthly, 245–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, William K. L., and Antonia Dickson. 2000. History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kineto-Phonograph. New York: Museum of Modern Art, USA. First published 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Dreben, Rich E., Murdoc Knight, and Marty A. Sindhian. 2011. Stuck Up! 100 Objects Inserted and Ingested in Places They Shouldn’t Be. New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group, p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Drew, Sidney, dir. 1917. Nothing to Wear. Santa Clarita: UCLA Film & Television Archive. Available online: https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/ (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze. 1894. Director unknown. Performance by Fred Ott. Edison Manufacturing Company. Library of Congress. Video. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/00694192 (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Edison, Thomas A. 1893. Apparatus for Exhibiting Photographs of Moving Objects. U.S. Patent US493426A; filed in 1891, [Google Scholar]

- Enstad, Nan. 1995. Dressed for adventure: Working women and silent movie serials in the 1910s. Feminist Studies 21: 67–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enstad, Nan. 2023. E-mail communication with the author. [Google Scholar]

- Films by the Year. 2023. Available online: https://filmsbytheyear.com/ (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Gaines, Jane. 2016. What was “women’s work” in the silent film era? In The Routledge Companion to Cinema & Gender, 1st ed. Edited by Kristin Hole, Dijana Jelaca, E. Ann Kaplan and Patrice Petro. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines, Jane, and Radha Vatsal. 2011. How women worked in the US silent film industry. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, Jane M. 2004. Film history and the two presents of feminist film theory. Cinema Journal 44: 113–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, Jane M. 2018. Pink-Slipped: What Happened to Women in the Silent Film Industries. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Gaines, Jane M. 2023. Antonia Dickson: The kineto-phonograph and the telephony of the future. Early Popular Visual Culture 21: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasnier, Louis J., dir. 1924. Wine. Performances by Clara Bow, Forrest Stanley, and Huntley Gordon. Universal City: Universal Pictures. Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0015499/ (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Gates, Harvey H. 1986. Alice Blaché: A dominant figure in pictures. The New York Dramatic Mirror. In The Memoirs of Alice Guy Blaché. Edited by Anthony Slide. Translated by Roberta Blaché, and Simone Blaché. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., vol. LXVII, 1768, Appendix F. p. 133. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Gene, Carroll, and Virginia Harriet, dirs. 1927. The Adventurous Soul; American Film Institute Catalog. Available online: https://catalog.afi.com/Film/2505-THE-ADVENTUROUSSOUL?sid=a6bf8fa8-ee26-41be-a6e5-34b6e52228a1&sr=3.8296528&cp=1&pos=1 (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Glick, Josh. 2011. Mixed messages: D.W. Griffith and the black press, 1916–1931. Film History 23: 174–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gove, Otis M., dir. 1906a. Scenes in San Francisco, No. 1. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 2:28, posted by Films by the Year. 20 June 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/2oIZdW5xoDE?si=EnbIA_PDJbi83_Qh (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Gove, Otis M., dir. 1906b. Scenes in San Francisco, No. 2. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 5:15, posted by Films by the Year. 13 July 2021. Available online: https://youtu.be/IX04C6rkVJM?si=ZO2CjOax7Nmk_zaj (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Griffith, David Wark, dir. 1915. The Birth of a Nation. Performances by Lillian Gish. Los Angeles: 20th Century Fox, vol. 2017, DVD. [Google Scholar]

- Guy–Blaché, Alice, dir. 1896. La Fée aux Choux; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0223341/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Guy–Blaché, Alice, dir. 1912a. The Girl in the Arm-Chair. New York: Solax Film Company, Video, 7:43, posted by Films by the Year. 6 August 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/DAVeSIRocdo?si=l8LVo3sl__6BsUeM (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Guy–Blaché, Alice, dir. 1912b. Making an American Citizen. New York: Solax Film Company, Video, 10:48, posted by Films by the Year. 4 August 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/RGoezMD74zw?si=PNlvw_ic_xExtxKi (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Guy–Blaché, Alice, dir. 1912c. Mignon; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0223733/?ref_=ttpl_ov (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Guy–Blaché, Alice, dir. 1913. Dick Whittington and His Cat; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0207409/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Guy–Blaché, Alice, dir. 1914. Lure; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0004275/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Güzel Köşker, Nisa H. 2020. The female body and female spectatorship in the American silent movie Love ‘Em and Leave ‘Em. Journal of American Studies of Turkey 53: 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, Hilary. 2013. Go West, Young Women! The Rise of Early Hollywood. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, p. 326. [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, Molly. 1974. From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Hennefeld, Maggie. 2014. Slapstick comediennes in transitional cinema: Between body and medium. Camera Obscura Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 29: 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennefeld, Maggie. 2016. Women’s hats and silent film spectatorship: Between ostrich plume and moving image. Film History 28: 24–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennefeld, Maggie. 2023. E-mail communication with the author. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, Graham Russell Gao. 2012. Anna May Wong: From Laundryman’s Daughter to Hollywood Legend. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, Wendy. 1995. Hollywood’s Modern Women—Screenwriting, Work Culture, and Feminism, 1910–1940. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, Jennifer. 2013. Alla Nazimova. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotaling, Arthur, dir. 1913. The Wrong Hand Bag. Philadelphia: Lubin Manufacturing Company, Video, 9:03, posted by JC Projections. 29 November 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/Q4UqpJJTtIo?si=clBlmEYaZs2sYJGN (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Hotaling, Arthur, dir. 1914. The Servant Girl’s Legacy. Philadelphia: Lubin Manufacturing Company, Video, 10:34, posted by Laurel & Hardy. 18 March 2015. Available online: https://youtu.be/QXEJJW6mlGI?si=FkjMgPCoSdojdSIL (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Internet Archive. 2023. Available online: https://archive.org/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Internet Movie Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/ (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Ionita, Casiana. 2013. Mrs. Sidney Drew. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Lewis. 1975. The Rise of America Film. New York: Columbia University Press. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Janis, Elsie, dir. 1915. Twas Ever Thus; Performances by Elsie Janis and Hobart Bosworth. American Film Institute Catalog. Available online: https://catalog.afi.com/Film/13883-TWAS-EVERTHUS?sid=b4cccd39-7fa7-4f76-ac2d-75ea0466867e&sr=5.2460146&cp=1&pos=0 (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Johnston, Claire. 1973. Women’s Cinema as Counter Cinema. In Movies and Methods, II. Edited by Bill Nichols. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jowett, Garth. 1976. Film, The Democratic Art. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, Internet Archive. Available online: https://archive.org/details/filmdemocraticar0000jowe (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Kalem Co. v. Harper Brothers. 1911. vol. 222 U.S. 55. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/222/55/ (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Lacassin, Francis. 1971. Out of Oblivion: Alice Guy Blaché. Sight and Sound 40: 154. [Google Scholar]

- Lacassin, Francis. 2022. The French films of Alice Guy: A filmography, compiled by Francis Lacassin. Appendix I. In The Memoirs of Alice Guy Blaché. Edited by Anthony Slide. Translated by Roberta Blaché, and Simone Blaché. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., p. 143. First published 1986. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=The+Memoirs+of+Alice+Guy+Blaché&author=Slide,+Anthony&publication_year=2022 (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Lang, Walter, dir. 1926. The Red Kimona; American Film Institute Catalog. Available online: https://catalog.afi.com/Film/11601-THE-REDKIMONA?sid=10fc3fd5-81c7-44f7-bc4a-0548208ad67c&sr=2.0691679&cp=1&pos=0 (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Lant, Antonia, ed. 2006. The Red Velvet Seat: Women’s Writings on the First Fifty Years of Cinema. London and New York: Verso, pp. 547–675. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Kendra Preston. 2018. Alice Smythe Jay. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumière, Louis, dir. 1895. La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/LaSortieDeLUsineLumireLyon (accessed on 28 June 2022).

- Lyons, MaryAnne. 2013. Beatriz Michelena. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowska, Ania. 2020. Waves of Feminism. The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media and Communication. Portland: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, Francis J., dir. 1907. Trial Marriages. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/silent-trial-marriages (accessed on 25 June 2023).

- Marvin, Arthur, dir. 1901. Deaf Mute Girl Reciting “Star Spangled Banner”. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 0:46, posted by Films by the Year. 23 November 2019. Available online: https://youtu.be/T_59fB_gJ0Y (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Mathis, June. 2006. The Feminine Mind in Picture Making. Film Daily (New York) 7:115. In The Red Velvet Seat: Women’s Writings on the First Fifty Years of Cinema. Edited by Antonia Lant. London and New York: Verso, p. 663. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon, Wallace, dir. 1905. Airy Fairy Lillian Tries on her New Corsets. Piscataway: American Mutoscope & Biograph, Video, 0:53, posted by Films by the Year. 1 January 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/ZASScW_0C1E?si=ytIHYDBrKhrHX6cC (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- McGowan, J. P., dir. 1914. Hazards of Helen. vol. 13, The Escape on the Fast Freight. Video, 12:41, posted by Silent Hall of Fame. 7 December 2013. Available online: https://youtu.be/vZsIdQs74Dw?si=QMQY0oVl1bE6yDP8 (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- McMahan, Alison. 2002. Alice Guy Blaché: Lost Visionary of the Cinema. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc., p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, Alison. 2013. Alice Guy Blaché. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. Available online: https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-5a4c-yq24 (accessed on 14 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Miles Brothers, dir. 1906. A Trip Down Market Street before the Fire; San Francisco Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/MarketStreet19064KScan20181016 (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Morgan, Kyna. 2013. Tressie Souders. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Kyna, and Aimee Dixon. 2013. African-American Women in the silent film industry. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, Laura. 1975. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen 16: 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Film Preservation Foundation. 2000. Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films. Directed by Various Directors. San Francisco: National Film Preservation Foundation, DVD. Available online: https://www.filmpreservation.org/dvds-and-books/treasures-from-american-film-archives (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- National Film Preservation Foundation. 2004. More Treasures from American Film Archives, 1894–1931. Directed by Various Directors. San Francisco: National Film Preservation Foundation, DVD. Available online: https://www.filmpreservation.org/dvds-and-books/more-treasures-from-american-film-archives (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- National Film Preservation Foundation. 2007. Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film, 1900–1934. Directed by Various Directors. San Francisco: National Film Preservation Foundation, DVD. Available online: https://www.filmpreservation.org/dvds-and-books/treasures-iii-social-issues-in-american-film (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- National Film Preservation Foundation. 2010. Treasures 5. West, 1898–1938. Directed by Various Directors. San Francisco: National Film Preservation Foundation, DVD. [Google Scholar]

- National Film Preservation Foundation. 2023. Available online: https://www.filmpreservation.org (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Noseworthy, William. 2023. Zoom meeting communication with the author. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, Frank, dir. 1925. Free to Love. Performances by Clara Bow and Donald Keith. Video, 59:45, posted by The Clara Bow Channel. 5 May 2022. Available online: https://youtu.be/63WuoFwmp7M?feature=shared (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Osborne, Florence M. 1925. Why are there No Women Directors? In The Red Velvet Seat: Women’s Writings on the First Fifty Years of Cinema. Edited by Antonia Lant. London and New York: Verso, p. 665. [Google Scholar]

- Peregini, Frank, dir. 1929. The Scar of Shame. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/the-scar-of-shame_1927 (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Pierce, David. 2013. The Survival of American Silent Feature Films. Washington, DC: Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress, pp. 1912–29. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Edwin S., dir. 1901a. Kansas Saloon Smashers. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/silent-kansas-saloon-smashers (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Porter, Edwin S., dir. 1901b. Why Mr. Nation Wants a Divorce. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/silent-why-mr-nation-wants-a-divorce (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Porter, Edwin S., dir. 1903. The Great Train Robbery. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/TheGreatTrainRobbery_555 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Porter, Edwin S., dir. 1907. Laughing Gas. New York: Edison Manufacturing Company, Video, 8:25, posted by Films by the Year. 15 August 2020. Available online: https://youtu.be/0YCqkam_MX4?si=LIn-MQzb_TYlPe9A (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Porter, Laraine. 2013. Women musicians in British silent cinema prior to 1930. Journal of British Cinema and Television 10: 563–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinovitz, Lauren. 2005. Past imperfect: Feminism and social histories of silent film. Cinémas 16: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rabinovitz, Lauren. 2023. Zoom interview with the author. [Google Scholar]

- Regester, Charlene. 2010. African American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility, 1900–1960. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. 406. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Marjorie. 1973. Popcorn Venus: Women, Movies, and the American Dream. New York: Coward McCann & Geoghegan. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Sara. 2013. Tsuru Aoki. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossell, Deac. 1995. Part I: Chronology. Film History 7: 119–78. [Google Scholar]

- Schuchman, John S. 1984. Silent movies and the deaf community. Journal of Popular Culture 17: 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, Mack, dir. 1914. A Busy Day. Performance by Charlie Chaplin. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/ABusyDay1914CHARLIECHAPLINMackSennett (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Sharp, Dennis. 1969. The Picture Palace and Other Buildings for Movies. London: Hugh Evelyn. [Google Scholar]

- Simmon, Scott. 2007. Introduction. In Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film, 1900–1934. Edited by National Film Preservation Foundation. p. ix. Available online: https://www.filmpreservation.org/dvds-and-books/treasures-iii-social-issues-in-american-film (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Slide, Anthony. 1977. Early Women Directors. South Brunswick: A. S. Barnes and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Slide, Anthony. 2012. Early women filmmakers: The real numbers. Film History 24: 114–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slide, Anthony, ed. 2022. The Memoirs of Alice Guy Blaché. Roberta Blaché, and Simone Blaché, trans. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., p. 180. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, Kay. 1981. Sexual warfare in the silent cinema: Comedies and melodramas of woman suffragism. American Quarterly 33: 412–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smith, Sharon. 1973. Women who make movies. Women and Film 1: 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Souders, Tressie, dir. 1922. A Woman’s Error; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0224408/ (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Stamp, Shelley. 2011. These Amazing Shadows: The Movies that Make America, Documentary Interviews. Distributed by PBS Video.

- Stamp, Shelley. 2013. Lois Weber. In Women Film Pioneers Project. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. New York: Columbia University Libraries. Available online: https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-zsv8-nf69 (accessed on 14 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Stamp, Shelley. 2015. Lois Weber in Early Hollywood. Oakland: University of California Press, p. 374. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Josef, and Clarence Badger, dirs. 1927. It. Performances by Clara Bow and Antonio Moreno. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/it-comedy-1927 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Szalat, Alex, dir. 2004. Clara Lemlich: A Strike Leader’s Diary. Brooklyn: Icarus Films. Available online: https://docuseek2.com/if-clar (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- The Atlanta Constitution. 1915. Birth of a Nation at Atlanta all week; every Forsyth act a headline feature. Author unknown. (1881–1945), 12. First published 8 December 1915. [Google Scholar]

- The Strong Arm Squad of the Future. 1912. Director unknown. Video, 1:01, posted by Eve Davis. 9 April 2012. Available online: https://youtu.be/CJM5Pe2ocfc?feature=shared (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- The United States v. Motion Picture Patents Company. 1915. 225f: 800. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1123236/download (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Theater Commercial—Warner’s Corsets. 1905. Director unknown. Video, 3:39, posted by HistoricFever. 16 June 2010. Available online: https://youtu.be/-BSNW4R_poM?si=57ojvvid_S3YdGhy (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Tomadjoglou, Kim. 2009. Introduction: Early colour. Film History 21: 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, Tony. 2016. Outside the system: Gene Gauntier and the consolidation of early American cinema. Film History 28: 71–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, May, dir. 1921. The Old Oaken Bucket; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0012519/ (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Tully, May, dir. 1925. That Old Gang of Mine; Performances by Maclyn Arbuckle, Brooke Johns and Tommy Brown. Released on December 18. American Film Institute Catalog. Available online: https://catalog.afi.com/Film/12611-THAT-OLDGANGOFMINE?sid=0192cc4d-2480-4b98-ab64-e2b38a928aed&sr=14.956618&cp=1&pos=0 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Tuttle, Frank, dir. 1926. Love ‘em and Leave ‘em. Performance by Clara Bow. Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/LoveEmAndLeaveEm1929ClaraBowJamesHallEdnaMayOliverJeanArthur (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- UCLA Film & Television Archive. 2023. Available online: https://www.cinema.ucla.edu/ (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Veditz, George, dir. 1901. Preservation of the Sign Language; Library of Congress. Video. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/mbrs01815816/ (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Weber, Lois, and Phillips Smalley, dirs. 1916. Where Are My Children? Internet Archive. Video. Available online: https://archive.org/details/silent-where-are-my-children (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Weinstein, Anna. 2021. Forgotten women comediennes in silent film: An interview with Kristen Anderson Wagner. Film International 19: 104–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, Alma. 1924. A Dangerous Little Devil is Clara, Impish, Appealing, But Oh! How she can Act. Los Angeles Times, September 7. [Google Scholar]

- White, Patricia. 1998. Feminism and film. In Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 117–31. Available online: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/18 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Wierzbicki, James. 2008. Film Music: A History. New York and London: Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Women & The American Story. 2023. Life Story: Clara Lemlich Shavelson (1886–1982). New York: New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. Available online: https://wams.nyhistory.org/modernizing-america/fighting-for-social-reform/clara-lemlich/ (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Women Film Pioneer Project. 2023. Edited by Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal and Monica Dall’Asta. Available online: https://www.online.uni-marburg.de/women-film-pioneers-explorer/index.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Women They Talk About Project. 2023. Available online: https://aficatalog.afi.com/wtta-silent-era/ (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Wong, Marion E., dir. 1916. The Curse of the Quon Gwon; Internet Movie Database. Available online: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0929415/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1 (accessed on 8 July 2023).

| Film Title | Production Company | Director | Premiere |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airy Fairy Lillian Tries on her New Corsets | American Mutoscope & Biograph | McCutcheon, Wallace | 1905/10 |

| Deaf Mute Girl Reciting “Star Spangled Banner” | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Marvin, Arthur | 1901/04 |

| Earthquake Ruins, New Majestic Theatre and City Hall | Edison Manufacturing Company | Bonine, Robert | 1906/06 |

| Girls Taking Time Checks | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Bitzer, G.W. | 1904/05 |

| Girls Winding Armatures | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Bitzer, G.W. | 1904/05 |

| Glory | M. L. B. Film Co. | Berri, Maud Lillian | 1917/11 |

| Her First Cigarette | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Armitage, Frederick | 1899/06 |

| Married for Millions | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Bitzer, G.W. | 1906/12 |

| Panorama, City Hall, Van Ness Avenue and College of St. Ignatius | Edison Manufacturing Company | Bonine, Robert K. | 1906/06 |

| Panorama, Nob Hill and Ruins of Millionaire Residences | Edison Manufacturing Company | Bonine, Robert K. | 1906/06 |

| Panorama, Notorious “Barbary Coast” | Edison Manufacturing Company | Bonine, Robert K. | 1906/06 |

| Panorama, Ruins Aristocratic Apartments | Edison Manufacturing Company | Bonine, Robert K. | 1906/06 |

| Ruins of Chinatown | Edison Manufacturing Company | Bonine, Robert K. | 1906/06 |

| Scenes in San Francisco, [no. 1] | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Gove, Otis M. | 1906/05 |

| Scenes in San Francisco, [no. 2] | American Mutoscope & Biograph | Gove, Otis M. | 1906/05 |

| That Old Gang of Mine | Kerman Film Corp. | Tully, May | 1925/12 |

| The Adventurous Soul | H. P. Productions | Gene, Carroll, and Virginia Harriet | 1927/11 |

| The Servant Girl’s Legacy | Lubin Manufacturing Company | Hotaling, Arthur | 1914/11 |

| The Girl in the Arm-Chair | Solax Film Company | Guy–Blaché, Alice | 1912/12 |

| The Great Fire Ruins, Coney Island | Edison Manufacturing Company | Abadie, A.C. | 1903/11 |

| The Wrong Hand Bag | Lubin Manufacturing Company | Hotaling, Arthur | 1913/07 |

| Theater Commercial—Warner’s Corsets | Unknown | Unknown | 1905/03 |

| Twas Ever Thus | Bosworth Inc. | Janis, Elsie | 1915/09 |

| Year | Total Films * | Extant Films by Women Directors | Non-Extant Films by Women Directors | Total Surviving Films ** | Total Films from Films by the Year *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 352 | 29 | (104) | - | 65 |

| 1912 | 426 | 32 | (101) | (6) | 82 |

| 1913 | (94) | 17 | (109) | (9) | 58 |

| 1914 | 373 | 19 | 30 | 66 | 55 |

| 1915 | 703 | 19 | 6 | 141 | 30 |

| 1916 | 959 | 26 | 23 | 216 | 91 |

| 1917 | 994 | 40 | 22 | 255 | 56 |

| 1918 | 882 | 18 | 8 | 152 | 42 |

| 1919 | 771 | 12 | 6 | 179 | 55 |

| 1920 | 749 | 10 | 8 | 209 | 138 |

| 1921 | 697 | 12 | 2 | 189 | 114 |

| 1922 | 681 | 4 | 1 | 168 | 62 |

| 1923 | 605 | 5 | 0 | 179 | 66 |

| 1924 | 678 | 2 | 0 | 244 | 91 |

| 1925 | 758 | 1 | 0 | 319 | 97 |

| 1926 | 742 | 1 | 0 | 328 | 86 |

| 1927 | 724 | 7 | 0 | 282 | 84 |

| 1928 | 703 | 5 | 0 | 236 | 87 |

| 1929 | 563 | 4 | 0 | 128 | 81 |

| 1930 | 535 | 7 | 0 | - | 225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, A.I. Social Changes in America: The Silent Cinema Frontier and Women Pioneers. Humanities 2024, 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13010003

Peng AI. Social Changes in America: The Silent Cinema Frontier and Women Pioneers. Humanities. 2024; 13(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13010003

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Alicia Inge. 2024. "Social Changes in America: The Silent Cinema Frontier and Women Pioneers" Humanities 13, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13010003

APA StylePeng, A. I. (2024). Social Changes in America: The Silent Cinema Frontier and Women Pioneers. Humanities, 13(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/h13010003