Abstract

This article examines tourism nature photography as a creative and sensual activity. Based on a collection of photographs gathered from tourists in the Strandir region in northwest Iceland, I demonstrate how photographing nature is a more-than-human practice in which nature has full agency. Much has been written about tourist photography since John Urry theorised about the tourist gaze in the early 1990s; this view has been criticised, especially in the light of the performance turn in tourism studies.It has, for example, been noted that tourist photography is not just about the gazing tourist, but also about social relations that the surrounding landscape partly directs and stages. It has also been argued that, as photographing tourists, we become ‘concerned with the artistic production of ourselves’. Photography is thus a practise that is relational and sensual and that cannot be reduced to the seeing eye. However, whilst emphasising the tourist as a creative being, the surrounding landscape has been left out as a stage and its active agency ignored. I address the complex, more-than-human relations that emerge in the photographs collected in Strandir. I argue that the act of photographing, as a performative practice, is improvisational and co-creative, and the material surroundings have a direct and active agency. As has been demonstrated, photography communicates ‘not through the realist paradigm but through lyrical expressiveness’ and, thus, it may be argued that tourist photography is a poetic practice of making, as it weaves together the sensing self and the vital surroundings in the moving moment that the photograph captures.

1. Introduction

- The Realistic Painter

- ‘To all of nature true!’—How does he plan?

- Would nature fit an image made by man?

- The smallest piece of world is infinite!—

- He ends up painting that which he sees fit.

- And what does he see fit? Paint what he can!

(Friedrich Nietzsche, emph. author)

Where does nature begin and end if even the smallest piece of world is infinite? How is it to be framed—or perhaps we should ask how it rejects being framed, and what makes nature’s infinity? What kind of nature is it that fits the frame of the painting? Is it just what the painter sees? How does he see, though, and could it be that he sees what he feels? In this article, I ask these questions in relation to the touristic snapshot. Similar to Nietzsche doubting the sincerity of the realistic painter who claimed he captured nature in his art, many scholars doubt the integrity of tourists’ photographs. Influenced by Sontag (1973), who stated that the act of photographing was a channel through which things were appropriated in an attempt to possess them, tourism scholars have been concerned with the camera as a rather common, even simple technology for documenting, on occasions invasive. Not only was it invented and developed to capture and possess images which evolved to promote and shape the appearance of tourist attractions, but also, the technology was directly associated with the consumption-driven, passively gazing tourist (Urry 1990; see also Garlick 2002; Bærenholdt et al. 2004; Larsen 2005). In particular, Urry’s (1990) ground-breaking publication ‘The Tourist Gaze’ was the most influential in this field. However, whilst the realistic painter might have claimed to be true to nature, the authenticity of the photographic image has been of less concern amongst tourism scholars. Rather, in its attempt to possess and frame, it is often seen as superficial and limited to how the gaze is directed. Around the turn of the century, much critique was directed at Urry’s writing about the tourist gaze, emphasising the performing and multisensory tourist body. In fact, Urry himself, co-writing with Larsen (Urry and Larsen 2011), re-evaluated his stance towards the gazing tourist and provided space for multi-sensuous, bodily experiences and performances. Still, Urry and Larsen also correctly emphasise that tourism marketing is driven by visual images, and this highly influences how tourists are directed towards destinations and experiences. As a result, one can claim that gazing and photographing are still at the forefront of studies and, thus, the visual continues to be the ‘dominant organising sense’ (Edensor 2018, p. 913). The surroundings remain passive, setting the stage of performance on which the photographic subject takes and an image. However, if every piece of the world is infinite, as Nietzsche claimed, is it not evident that the photographic image must somehow reveal that infinity? Edwards (2012) has claimed that photographs are ever-moving and vital things that spark emotions, feelings and bodily reactions that can never be apprehended merely through their visual content. As such, it can be claimed that photographs, as things, are animate beings that affect (Bennett 2010) and even provoke. Accordingly, I consider photographs to be vital and vibrant; they allow the onlooker to delve into the heterogenous narratives they contain, sometimes to be swept away into different directions and as such are infinite. This article reflects on tourist nature photography with an emphasis on nature as affective, sometimes unruly, even wild. In the vein of landscape phenomenology, I consider tourist photography as a creative and affective process (Garlick 2002; Scarles 2009) in terms of how the photographing tourist body relates to the surroundings. However, given the emphasis on nature’s infinity, non-human bodies and actors must also be considered as creative actants. This requires that we not only think of the tourist body as merely sensual—in the case of this article, as a seeing body—but as relational, entangled, sentient and earthly beings—in Merleau-Ponty’s (1968) terms, as being ‘of the flesh of the world’ (Sigurðardóttir 2020, p. 129). Simultaneously, the surroundings must be met as vital and dynamic; thus, the encounters cannot be reduced to what is seen and how it is captured. Rather, I argue that photographing nature is a dynamic process that must be examined from both phenomenological and post-human perspectives with an emphasis on encounters as more-than-human entanglements.

In 2011, a team of researchers in a project that I co-led1 collected photographs from both tourists, domestic and foreign, and locals in the region of Strandir in northwest Iceland. Just over 130 photos were collected from around 30 participants who were randomly approached on our travels in the region as we conducted fieldwork. All tourists we approached were travelling independently, as couples, families or as small groups of friends and had different national backgrounds, some Icelandic, whilst the foreign visitors came mostly from northern Europe. What all had in common was that they were spending time travelling in the region, some camping, and others staying in locally offered accommodations. Whilst the photos we collected have been mentioned and briefly examined in variety of publications that resulted from the project, we never wrote a paper dedicated to their content, even though we intended to. However, I have discussed them in several presentations, and they have always remained in the back of my mind, a reminder that they require publication. Their existence therefore urged me to return to them when I was invited to write for this special edition. Although time has passed and technology changed since they were collected, I consider them relevant to the content of this article, as I am not examining motives or techniques behind tourism photography, but rather, the human/nature relations the photos themselves contain. The reason behind the urge to return to the photographs is their multivocality (Bender 2002), which is reflected in the narrative complexities with which I felt entangled when looking at them. When we asked the tourists we met to send us photos, we asked them to select three to five that they felt mirrored the atmospheres they experienced when travelling through the region; we also asked them to write short captions to reflect upon the photo’s content.2 What all the images share is that they reveal aspects of nature; nevertheless, it is not nature in its purest form, one that has been framed to ‘fit an image made by man’, but rather one that is unruly and that resists ‘containment, naming and enclosure’ (Behrisch 2021, p. 491)—and thus, this nature is indeed infinite. The ways in which this infinite nature happens in photographic images, that is, how it emerges through the encounters that generate it, is the subject of this article. I start this paper by introducing the Strandir region as a tourist destination and how nature features in promoting it as such. I then examine further the performing tourist as an explorer who must make sense of the complexities with which she or he is entangled when journeying through nature and trying to grasp the meaning of it with the aid of the camera. I then discuss several selected images from tourists who visited Strandir during summer 2011. Finally, I discuss what the images reveal, with an emphasis on how nature appears as mobile through the stillness that they frame and that reveals their infinity.

2. Strandir as Destination

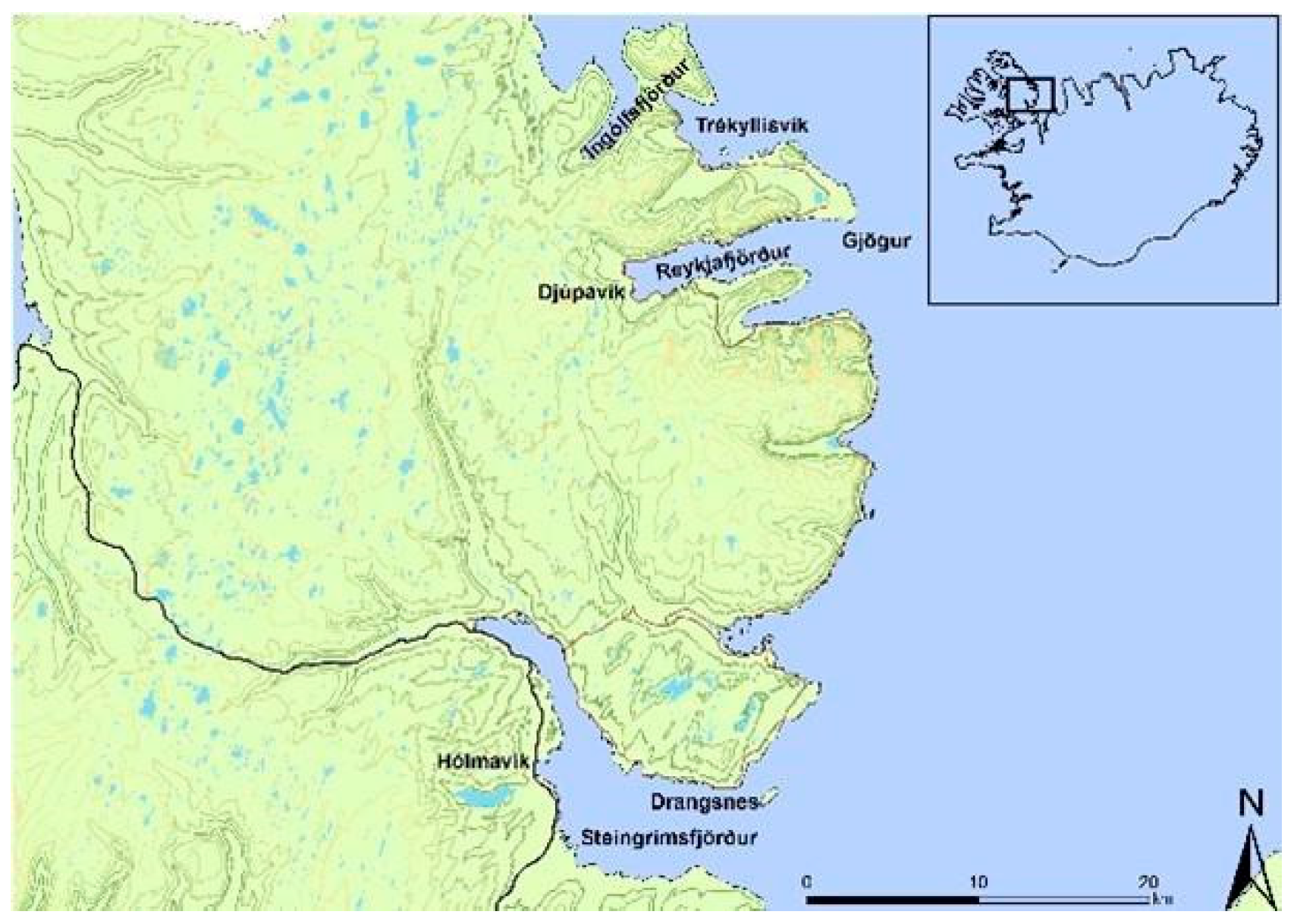

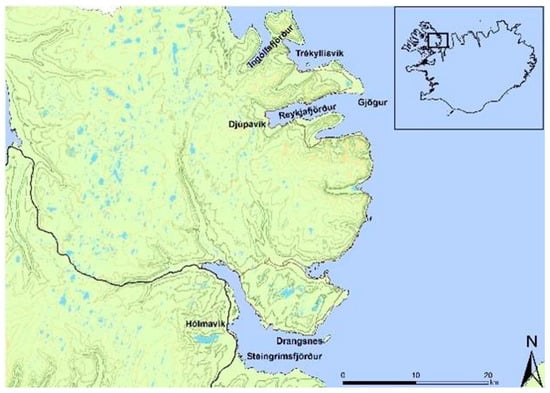

The Strandir region is located on the south-eastern side of the Vestfjords Peninsula in Iceland (Figure 1). Although it is only about a three-hour drive there from the capital, Reykjavík, it is generally considered a remote area. This might be explained partly by the fact that, to travel there from Reykjavík, one must leave the highway around Iceland after 144 km of driving and continue for about 121 km on a connecting road to reach its main settlement, Hólmavík, a village of around 400 inhabitants.

Figure 1.

Map of Strandir.

The Strandir region is a sparsely populated area with about 600 inhabitants. When travelling through it, the barren landscape and harsh environment cannot be easily escaped, and these conditions underline its marginal aura. The road, long stretches of which is paved only with gravel, winds up and down mountain passes from fjord to fjord and around hillsides, some of which seem to be waiting to slide into the sea. Although this part of the country has always thrived on sheep farming, lowland is limited. However, access to rich fishing grounds is plentiful, and farming and fishing have always been considered the main pillars of the region’s economy. Especially in the northern parts of the region, driftwood and eiderdown used to be sources of further income. However, wealth and prosperity have never been a significant aspect of life in the region; rather, it is a place where people depended upon and lived in close co-habitation with the forces of often-unpredictable, fierce and unruly nature. As farms grew larger in the 20th century, with less demand for labour, fisheries remained the backbone of the economy for those who continued to live in the region. In the 1980s, the fishing industry in Iceland underwent drastic changes with the implementation of the transferrable quota, which was meant to increase the efficiency and management of fishing stocks. This had major negative impacts for some smaller coastal communities in Iceland. The fishing industry in the Strandir region was no exception, as access was subsequently based on corporate capital (Karlsdóttir 2008). Consequently, the Icelandic government starte encouraging declining communities, by means of funding and aid, to consider other sources of income, such as tourism and strengthening their cultural wealth. In the 1990s, a group of young men in the Strandir region took up this challenge and applied for funding to develop cultural tourism in Strandir (Gunnarsdóttir and Jóhannesson 2014; Lund and Jóhannesson 2016; Lund 2015). The concept they decided to promote concerned witchcraft and sorcery, and they relied on 17th-century historical accounts from the peak of the witch-hunting and -burning era in Iceland. For many Icelanders, especially those of older generations, this murky period is strongly associated with Strandir. Although many inhabitants of Strandir were slightly disturbed by the act of stirring up this past to attract tourists, ultimately there was a general agreement with the outcome. The young entrepreneurs were conscious of the feelings this history could conjure and implemented it with care (Lund and Jóhannesson 2016). Now, the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft in Hólmavík is a popular place to visit, and the region has become an established destination and is growing accordingly. However, its peripheral position means that tourism en masse has not materialised in any way, which means that the sense of remoteness is still strongly associated with the region, as this quote from the travel promoter Iceland Travel indicates:

When visitors wish to leave the modern society behind, Strandir is the place to go. No wifi, no cell phones, just being lost in nature. Strandir is a popular hiking attraction and many Icelanders visit this area every year. For a good reason, this area is almost magical, both pure and unspoiled.(Iceland Travel n.d.)

According to this view, the aura of magic seems to permeate the region outside as well as inside the museum; this is in fact the case, as its narration resides in the surrounding landscape. In addition to emphasising magic and the act of witchcraft, the Museum also strongly highlights the social environment it thrived in and displays Strandir as a farming society in which the life of poor peasants strongly relied upon what nature provided and who, consequently, had to deal with its unpredictability. In this environment, magical spells and acts were means to respond to and act upon circumstances. Thus, through its display, the Museum brings forth nature/culture relationality and in doing so underlines the more-than-human aspects of the Strandir region as a destination which brings forth a magical aura. Therefore, this attempt to attract tourists to the region on the basis of its cultural history also extends the display to the surrounding landscape and strengthens ‘the image of Strandir as a magical region’ (Lund and Jóhannesson 2016, p. 658; see also Lund 2015) where more-than-human elements enmesh and emerge as a chaotic wilderness. As Cronon (1996) has noted, wilderness has always implied blurred boundaries between nature and culture because wild nature contains ‘earth’s mystery’ (Behrisch 2021, p. 491), which can appear to observers as magical. Therefore, the more-than-human nature of Strandir is not what Behrisch (2021, p. 492) refers to as the ‘colonial ideal of wilderness untouched by humans’; rather, it is wild, unruly, unpredictable and multivocal, full of human and more-than-human figures and features. It is not only a scene that the tourist enters and should not be framed merely as an image or as wilderness in its purest form. Instead, given its heterogeneous, multivocal existence, it is infinite. The question this evokes is how wild or magical nature is performed as such by tourists and how that performance is narrated in photographic images that portray its infinity.

3. Performing Nature, Exploring Earth

As noted above, critical responses to Urry’s gazing tourist brought attention to the moving, sensual and performing body in tourism. In contrast to an abstracted, distant, and gazing figure, the tourist gained a moving and sensual body that entered a stage as a performing agent (Edensor 2000, 2001). Defining destinations as stages offered the tourist the possibility of participating in the game as a performer or actor in a place designed, to varying degrees, as a scene (Larsen 2005). Moreover, despite this already existing design, the tourist became not just an actor, but also one who had the power to enact and shape the destination. Thus, it is necessary to examine how the tourism industry uses promotional materials and marketing to entice visitors to enter certain atmospheric stages (Böhme 2013; Bille et al. 2015). Such materials offer the tourist the possibility of engaging with the scene almost physically through imagination, although without the sensual body and earthly touch (Lund 2021). Barry and Keane (2019, p. 112) have noted that Icelandic landscapes have been promoted as wilderness, ‘pristine “natural” landscapes that reinforce the anthropocentric ideals of tourism’. This recalls with the quote from Iceland Travel above, which emphasises the pure, unspoilt natural environment. Eventually, the tourist physically steps into these ideals, as Larsen (2005, p. 422) argues, noting that tourists are

actors in shows directed by themselves and/or the tourist industry. In addition to looking at places, tourists enact them corporeally. They step into a landscape picture and engage bodily, sensuously and expressively with their materiality.

Therefore, as Edensor (2018) argues in his critique of the performance turn in tourism studies, bodily sensation is only presented as additional to visual perception, and the tourist remains primarily a visually consuming being. Although tourists are provided space as directing performers in the scene, they are spatially restricted by it and its design and how they see, or the multi-sensual touch (Lund 2005) is missing. I argue that, if we investigate further and examine how the tourist sees rather than merely what he sees, it is important to consider how the stage or the given scene transforms and even dissolves as the tourist enters it and develops a bodily feel for it. Building on Deleuze and Guattari (1987), the space that the tourist enters is a tactile one in which ‘visibility is limited’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 421). The tactile sensation constitutes the relation to the earth rather than a scene or a stage, and earthly touch does not locate the tourist in nature or on a stage; rather, she or he is entangled with the surroundings, which are infinite. I posit that the idea of a mere scene or stage on which the tourist performs limits our scope to how the tourist senses, sees, hears, smells and feels precisely because it excludes how the texture of nature touches and affects. This is in accordance with Ingold’s (2011) claim that earth has no surface; instead, it is a composition of ‘messy more-than-human entanglements which we live, sense, feel and experience through more-than-human bodily movements and encounters’ (Lund 2021, p. 130). Thus, it can be assumed that when tourists enter the tourist stage bodily, a space is opened that is without limits; it is earthly, messy and infinite, and the tourist needs to order and capture it to fit, like the realistic painter Nietzsche describes above. The question is how the eye can order and capture infinity through these encounters in light of the claim that sight is a multi-sensual phenomenon that calls forth the request to consider how the tourist body performs, in the case of this study by examining tourist photography in Strandir. As stated above, performance theory has emphasised the tourist as a social, moving and active being. The tourist has the freedom to react and play with the scene in a chosen manner but is still restricted to the spoken and unspoken rules of the scene design. However, the elements of the body that touch and feel remain absent. My argument is that what is missing is how the tourist experiences or the actual encounters with the scene. Further, if the scene in question, as I argue, is a combination of messy, more-than-human entanglements, the encounters must demand a degree of exploration by the tourist, not least since the tourist becomes directly entangled. I thus want to stress that tourists are not only active performers, but also vigorous explorers. With the term ‘explorer’, I do not refer to those who travelled to discover new lands in the Victorian era nor those whom Cohen (1996) has labelled as such for travelling off the beaten path. Rather, I refer to tourists who become involved with the surroundings and allow themselves to be moved by those surroundings at the same time that they move with them (Lund 2023).

Nature is also unpredictable and constantly on the move and plays upon the visitor, and this aspect demands constant attention. Merleau-Ponty states that ‘vision is a palpation with the look’ (Merleau-Ponty 1968, p. 134) emphasising the touching eye that is entangled with what it sees. In his words: ‘Since the same body sees and touches, visible and tangible belong to the same world’ (ibid.). Thus, seeing can be said to be a complex process of ordering, of simultaneously touching and being touched. Additionally, an important element during the process of exploration is that nature is not innocent; it acts upon, with and even against, the seeing body who is moved by it. Exploration is a creative, dynamic process of sensual communications or, as Lund and Benediktsson (2010) have illustrated, more-than-human conversations (see also Abram 1996). These conversations are actualised in the narratives that the photographic images entail.

4. Nature Narratives–Co-Creation

In her work, Sigurðardóttir uses the term ‘poetic storytelling’ to describe how the observing photographer approaches the ‘flow of reality’ (Sigurðardóttir 2020, p. 129) that surrounds one as one moves through it. She focuses on the role of the photographer who, in order to capture images, temporally interrupts this flow when a pause is made not to freeze it, but rather to capture it. It is a moment of conscious encounters that open up for a momentary dialogue. This could apply to the exploring tourist who is entangled not only with the flow of reality, but also in a spatio/temporal flux of the more-than-human surroundings that call for attention. Garlick (2002) has stated that, as exploring tourists, we become ‘concerned with the artistic production of ourselves’ (ibid., p. 298), and photography is a tool to narrate both what touches the eye and the travelling self. It is a process of co-creation through which the photographer is ‘both aware of and reflective about her or his perspective as an embodied being and how her or his embodiment is part of the work created’ (Sigurðardóttir 2020, p. 129). Edwards (1997, p. 58) has stated the following:

Photography can communicate about culture, people’s lives, experiences and beliefs, not at the level of surface description but as a visual metaphor which bridges that space between the visible and invisible, which communicates not through the realist paradigm but through lyrical expressiveness.

In other words, capturing an image is a means of narrating the surrounding entanglements and locating the self in the narratives. It is a process of co-creation that combines, organises and makes sense of more-than-human fluidity in order to tell stories. In the case of the Strandir region, the photographs we collected from tourists all told stories of being with nature, sensing its movements and/or being moved by it. Those are stories that, in one way or another, emphasise the peripheral, romantic and nostalgic aspects of Strandir as it is promoted as a destination. Nevertheless, the images reveal how nature touches participants in different manners given the nature of the encounters. It opens up a multiplicity of spatio/temporal journeys given its infinite quality and simultaneously opens up a space for tourists to narrate their personal version. An image of an arctic tern that flies out of the picture frame literally captures a mobile nature that touches the photographer (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Arctic tern.

The accompanying caption says:

“I love those birds… Impressive, they fly from the Antarctic seas to Iceland and back during one year!”

The tern flies out of the frame as the photographer attempts to capture it, as if to tease the photographer or even convey that he is not in control. Nevertheless, the photographer selected the image to reflect on the tern’s vast, regular, seasonal movements that bring it to the other end of the globe and back again. The photographer is impressed by the scale of its capacity for mobility. For many, it is difficult to imagine that this relatively small bird has the strength to travel this distance, and the freedom that this mobility implies seems to fascinate the photographer. The caption hints at how the photographer tries to identify with the tern whilst trying to comprehend its capacity to travel. Migrant birds appear to provide a sense of being a part of a nature that is vital and that shows how mobile forces and vitalities combine and make a place.

Another feature in the nature of Strandir that is often photographed with amazement is the driftwood on the shore. Like the migrant birds, it has travelled a long way, for example, from the rivers of northern Russia. It is easier to capture in a photo than the birds, as it sits still—or so it seems—on the seashores, although waves and winds may slightly jostle it back and forth. It is precisely the stillness of it that captures tourists’ attention, and they wonder about so much wood appearing in a place with no trees, as in the following example: ‘We were always astonished about the enormous amount of wood at the seashore’. The driftwood implies mystery, and it allows the onlooker to journey with it in space and time, as its still presence indicates the mobile powers of the wind and ocean. It somehow disturbs the flow on the shore, where land and waters meet, and by creating flux, it calls for narration. However, Icelandic tourists who are informed about the history and geography of Iceland are returned to a past that resembles their own experiences as indicated in a caption we were sent (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Driftwood.

… shows nature in Strandir and the driftwood that was so important for survival in these harsh environments.

Here, the driftwood is referred to as an important and naturally imported source of income in a country almost entirely lacking wood with which to build. This observation takes the photographing tourist into the past to reflect upon how life was lived with nature, and the driftwood narrates this story. In fact, it is often the stillness of nature that seems to narrate movement, as in an image named ‘The sky, the sea and the slope’; as the photographer explains, it ‘shows how the sea and the sky can fall together’ (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The sky, the sea and the slope.

The photographer is caught up with the more-than-human movement of nature, and a short pause is made to capture it. Nature plays upon the photographer in a deceiving manner and blurs boundaries. These are playful encounters that bring forth mystery, a sense of stillness full of infinite motions.

It is exactly the stillness that the photographic image captures, the pause in the otherwise ongoing flow or flux that exaggerates the often-heterogeneous mobilities that its narratives bring forth. This becomes evident when relics of the past are the subject (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

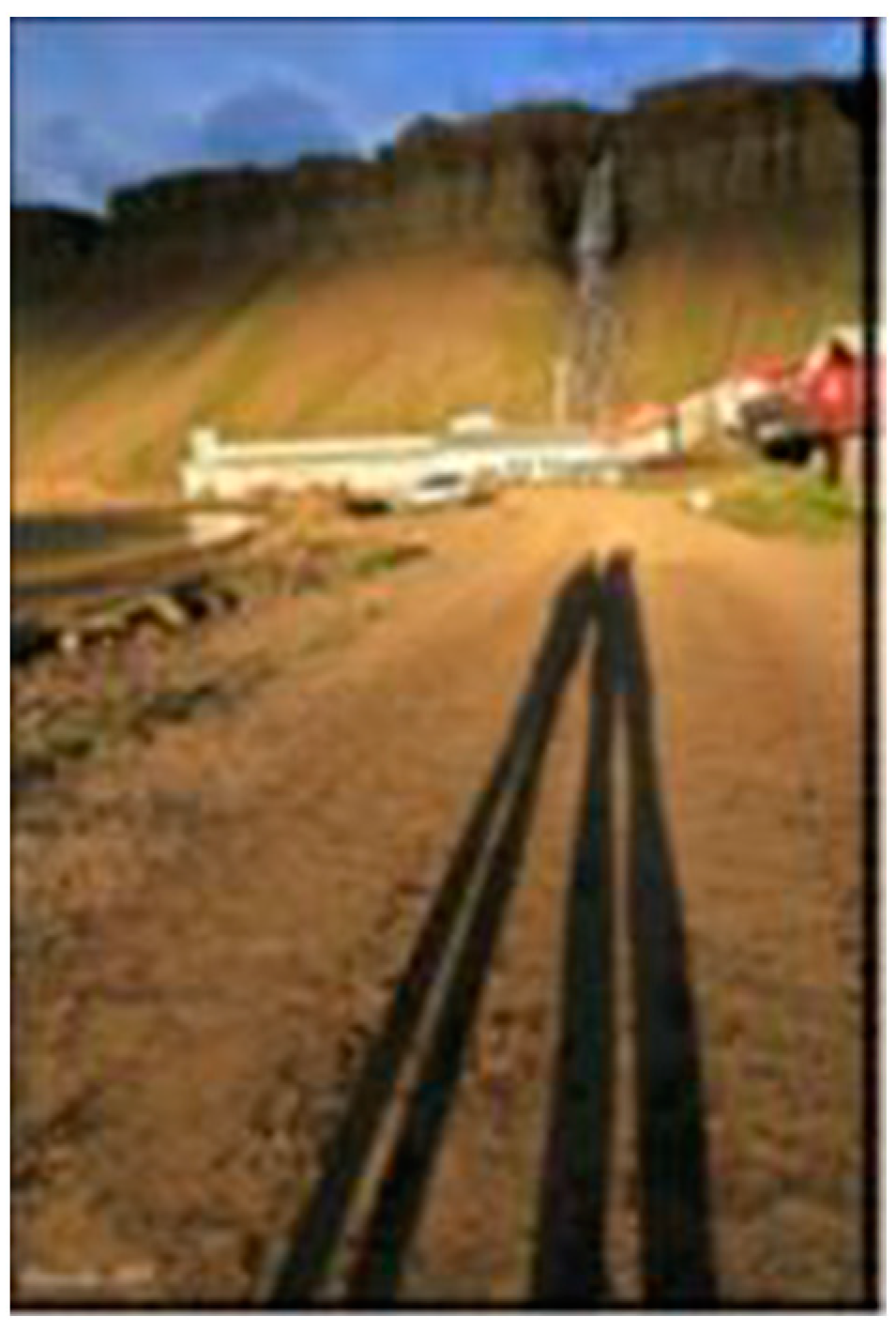

The factory.

This image features two tourists, members of the same family located near one of the best-known attractions in rural Strandir, a modern ruin of an oil tank that formed a part of an old herring factory that operated from 1934 to 1958.

The history of herring in Strandir is well documented, and although the buildings were left to decay in total dereliction, contemporary tourism has not allowed that to continue. In 1975, a couple from Reykjavík, the capital, arrived in the area to settle in one of the buildings that accompanied the factory as housing for the female workforce and turned it into a hotel. Grounds for small-scale tourism were immediately seeded, and soon, the factory ruins became a centre of attraction (Lund and Jóhannesson 2014). Whilst the photograph can tell us about a family’s journey, as its members are in the foreground (e.g., Larsen 2005), the accompanying caption indicates how it speaks to the photographer who brings attention to the remains of the industrial ruins:

Abandoned constructions that bear witness about ambitions and optimism, but although king wants to sail God provides the wind.

The text indicates how the factory was built to conquer and prosper from herring that, in the 1930s, appeared in what seemed to be limitless numbers in the waters around Iceland, but disappeared almost as fast as they had arrived, about twenty years later. The factory remains encompass these grand hopes for future prosperity that were defeated by the unpredictable movements of nature. Now, nature has taken over, and the ruins remain, decaying and requiring constant maintenance to prevent them from becoming dangerous. However, these structures, which somehow seem to be at odds with nature because they are modern, man-made features in an area that otherwise demonstrates humans living humbly with nature, carry with them an aura of the sublime; both Edensor (2005) and Pálsson (2013) have noted that modern ruins can provoke such a response (Lund and Jóhannesson 2014). They entail a complex sense of in-betweenness, simultaneously unruly and wild, in and out of place and time; they are an interstitial wilderness, a battlefield of more-than-human elements: wind, rain, insects and flora. They are a history that has not been shaped into a single storyline; rather, the ruins ooze out narratives in which the exploring tourist is enmeshed as she or he moves around them. One can also explore selected parts of their interior, in which one may find an operating gallery and, sometimes, pop-up exhibitions, an attempt by the owners to intervene in the process of ruination. In fact, remains of the past appear in many photos. These include ruins of old farms and abandoned machinery that remain in the surroundings and that, as with the case of the driftwood, disrupt the flow of the surroundings and bring forth narratives (Figure 6). According to Behrisch (2021), these remnants are wild elements, vibrant matters (Bennett 2010) that address the exploring tourist directly, prompting an urge to stop in an attempt to capture the stories they generate.

Figure 6.

Fishing boats.

These images often reflect on imagined encounters with people who used to live in the area, even with reference to present inhabitants, as in Figure 6, which shows three fishing boats on dry land with the following caption:

“Three generations”. Descriptive of Strandir, where the drive and efficiency of past and present inhabitants are clearly visible.

Conversations emerge that directly reference those who lived with nature, in this case, in a diligent, hardworking way. Like in the case of the modern industrial ruins, the image narrates a stillness in flux that brings forth different rhythms and temporalities at the same time. The industrial ruins, meanwhile, draw attention to themselves; they represent an almost-sudden happening that, for some, seems somewhat overwhelming, which gives them their sublime aura. Still, both cases represent encounters with wild elements through which stories come together, meet and make infinite places (Marr et al. 2022) through a process of more-than-human co-creation.

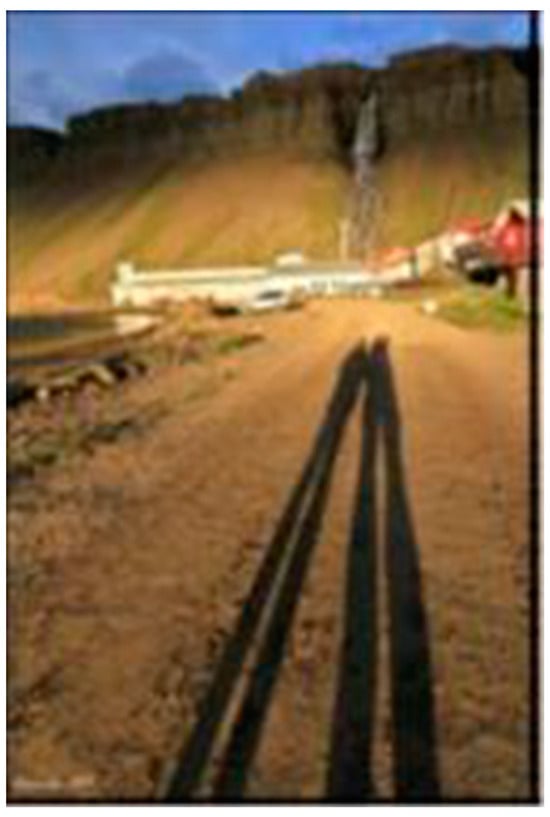

As noted above, Strandir is not only promoted as a destination where visitors meet time that remains still in opposition to the urban landscape of the capital, Reykjavík, but also as a magical place. The 17th-century history of witchcraft in Iceland is strongly associated with the place, not least through the establishment of the Museum of Icelandic Witchcraft and Sorcery, as well as through the ways in which the magical aura extends out to the surroundings. The images from Strandir represent this magical aura through a variety of encounters. Many captions refer to changing weather conditions and seasonal changes as bringing in magical aspects as the conditions somehow move or even shift, altering rhythms and atmospheres that affect the journey. In many cases, the exploring tourist needs to slow down or momentarily stop in the midst of the flux. As summer ends, the changing light of the evening sun can play tricks, as two tourists at Djúpavík (Figure 7) noted. One used the camera to capture the affect and later sent the resulting photo to us with the following caption:

Figure 7.

Shadows.

“This picture shows the magic light around Djúpavík in the evening, when the shadows are pretty long. You start to detect your surroundings again when the light changes.”

The light momentarily offers a magic touch that plays with the bodies of the photographer and companion as the rays of the autumn sun gently strike the road on which they walk but do not reach the top of the mountain in the background. It is a time when the evenings grow shorter, and one can sense slightly cooling temperatures as winter slowly sets in. The image contains the magical effects of moving seasonalities, a slowly moving, infinite in-betweenness and how nature constantly mediates its doings by providing us with different stories to tell depending on how it touches us and allows us to feel it and understand it. The magic can also filter through in encounters with features in the landscape and that bring together different worlds, such as when past and present run into each other, or where humans and figures of different dimensions meet. Pictures of rocks said to be the home of hidden people or rocks that, according to folklore, are fossilised trolls were quite common. Sometimes, though, these earthly features took on appearances that played with the explorer’s imagination, such as this mundane rock that addressed the photographer with its presence (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Magical cliff.

However mundane it may seem, the photographer writes:

… cliff that caught my eye, hence definitely magical.

The aura of the 17th century seeps through wild, earthly features, as in the case of this rock, but sometimes, the narratives are more direct, like in the case of a tourist passing a place called Kistuvogur, where three men were burnt to death in the year 1654 after being accused of witchcraft (Lund and Jóhannesson 2016; Figure 9). The caption states:

Figure 9.

Kistuvogur.

History becomes palpable in places like this.

It is in places like this that absent history becomes present through the intimacy of its murky and moving narratives. For example, in the case of the factory ruin, the place contains invisible but wild narratives that disturb the stillness; such narratives disrupt the flow of time, which indicates darkness but also fascinates and even absorbs the exploring tourist; the place is hence sublime and infinite because of how its presence becomes evdent in its physical absence (Bowman and Pezzullo 2009). In other words, rocks tell stories about what they have seen, and their narration extends itself far beyond our humble human lifespan and experiences; they allow us to travel with them into different temporalities.

5. Discussion

This article reflects on tourist nature photography with an emphasis on nature as affective, sometimes unruly and even wild, and thus infinite as it oozes narratives that emphasize its state of constant becoming. In the vein of landscape phenomenology, tourist photography is considered as a creative and affective process (Garlick 2002; Scarles 2009) in terms of how the photographing tourist’s body relates to the surroundings. Given nature’s infinity, however, I argue that non-human bodies and actors must also be considered creative actants in the process of photographing. Thus, my argument is that photographing nature is a co-creative and dynamic process that must be examined from both phenomenological and post-human perspectives, with an emphasis on encounters as more-than-human entanglements. Tourists’ nature photography in the Strandir region on the south-eastern side of the Vestfjords Peninsula in Iceland provides examples that demonstrate how the photographic image reflects a vibrant and vital nature and are thus the images are infinite in themselves.

My claim is that the tourist not only needs be seen as a performing agent, but also as an exploring one who, through her or his encounters, becomes entangled with the surroundings as she or he journeys. Although promotional materials may have framed the destination as a scene or a stage, it is the bodily touch through which the tourist’s body encounters nature, which blurs the tourists’ vision as the vital surroundings start to play with and upon the tourist who moves with them. The photographic image allows the researcher to follow the movements of the tourist and perceive the moments which ask for a momentary pause to capture an image that assists in narrating the journey. When following these movements, it is important to keep in mind that tourists do not merely move over and/or on a surface of earth; rather, they try to find their feet in messy, more-than-human entanglements where elements of nature and culture blur.

It is thus the photographic narratives that capture nature’s infinity. The vibrant stillness of the image oozes out narratives that engage one in conversations that meander into different spatio/temporal directions (Lund and Benediktsson 2010). Attempts to capture and freeze nature or moments of nature are not possible. Nature as lived is not to be disciplined (Bender 2002); it is chaotic and can be unpredictable. Therefore, it can be said that the more-than-human encounters that nature tourism entails demand an active and constant co-creation of nature which continues to shape a destination.

Funding

The project of this article is based on was funded by the Arctic Chair 2010–2012. It received funds from the Foreign Ministry of Norway and was hosted by the Arctic University of Norway.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The project Arctic Chair was funded by the Foreign Ministry of Norway and hosted by the Arctic University of Norway. |

| 2 | All those who participated in the research and sent us images formally agreed that the photos could be used for publications. |

References

- Abram, David. 1996. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bærenholdt, Jørgen Ole, Michael Haldrup, and John Urry. 2004. Performing Tourist Places. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Kaya, and Jondi Keane. 2019. Creative Measures of the Anthropocene: Art, Mobilities and Participatory Geographies. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Behrisch, Tanya J. 2021. Shapeless Listening to the More-Than-Human World: Coherence, Complexity, Mattering, Indifference. Cultural Studies–Critical Methodologies 21: 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, Barbara. 2002. Time and Landscape. Current Anthropology 43: S103–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bille, Mikkel, Peter Bjerregaard, and Tim Flohr Sørensen. 2015. Staging Atmospheres: Materiality, Culture, and the Texture of the In-between. Emotion, Space and Society 15: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, Michael S., and Phaedra C. Pezzullo. 2009. What’s So ‘Dark’ about ‘Dark Tourism’?: Death, Tours, and Performance. Tourist Studies 9: 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, Gernot. 2013. The Art of the Stage Set as a Paradigm for an Aesthetics of Atmospheres. Ambiances. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Eric. 1996. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. In The Sociology of Tourism: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. Edited by Yiorgos Apostolopoulos, Stella Leivadi and Andrew Yiannakis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cronon, William. 1996. The Trouble with Wilderness: Or Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. Environmental History 1: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, Tim. 2000. Staging Tourism: Tourists as Performers. Annals of Tourism Research 27: 322–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, Tim. 2001. Performing Tourism, Staging Tourism: (Re)producing Tourist Space and Practice. Tourist Studies 1: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, Tim. 2005. Waste Matter–The Debris of Industrial Ruins and the Disordering of the Material World. Journal of Material Culture 10: 311–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, Tim. 2018. The More-than-Visual Experiences of Tourism. Tourism Geographies 20: 913–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 1997. Beyond the Boundary: A Consideration of the Expressive in Photography and Anthropology. In Rethinking Visual Anthropology. Edited by Marcus Banks and Howard Morphy. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Elizabeth. 2012. Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 221–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlick, Steve. 2002. Revealing the Unseen: Tourism, Art and Photography. Cultural Studies 16: 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsdóttir, Guðrún Þóra, and Gunnar Thór Jóhannesson. 2014. Weaving with Witchcraft: Tourism and Entrepreneurship in Strandir, Iceland. In Destination Development in Tourism: Turns and Tactics. Edited by Arvid Viken and Brynhild Granås. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland Travel. n.d. Strandir Coast. Available online: https://www.icelandtravel.is/attractions/strandir-coast/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsdóttir, Anna. 2008. Not Sure about the Shore! Transformation Effects of Individual Transferable Quotas on Iceland’s Fishing Economy and Communities. American Fisheries Society Symposium 68: 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, Jonas. 2005. Families Seen Sightseeing: Performativity of Tourist Photography. Space and Culture 8: 416–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Katrín Anna. 2005. Seeing in Motion and the Touching Eye: Walking over Scotland’s Mountains. Ethnofoor 18: 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Katrín Anna. 2015. Just Like Magic: Activating Landscape of Witchcraft and Sorcery in Rural Tourism, Iceland. In Changing World Religion Map. Edited by Stanley Brunn. New York: Springer, pp. 767–82. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Katrín Anna. 2021. Creatures of The Night: Bodies, Rhythms and Aurora Borealis. In Rethinking Darkness: Cultures, Histories, Practices. Edited by Nick Dunn and Tim Edensor. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Katrín Anna. 2023. Poetics of Wilderness: Ordering Nothingness. In Mobilities on the Margins: Creative Processes of Place Making. Edited by Björn Thorsteinsson, Gunnar Thór Jóhannesson, Katrín Anna Lund and Guðbjörg R. Jóhannesdóttir. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Katrín Anna, and Gunnar Thór Jóhannesson. 2014. Moving Places: Multiple Temporalities of a Peripheral Tourism Destination. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 14: 441–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Katrín Anna, and Gunnar Thór Jóhannesson. 2016. Earthly Substances and Narrative Encounters: Poetics of Making a Tourism Destination. Cultural Geographies 23: 653–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, Katrín Anna, and Karl Benediktsson. 2010. Introduction: Starting a Conversation with Landscape. In Conversations with Landscape. Edited by Karl Benediktsson and Katrín Lund. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, Natalie, Mirjami Lantto, Maia Larsen, Kate Judith, Sage Brice, Jessica Phoenix, Catherine Oliver, Olivia Mason, and Sarah Thomas. 2022. Sharing the Field: Reflections of More-Than-Human Field/work Encounters. Geohumanities 8: 555–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pálsson, Gísli. 2013. Situating Nature: Ruins of Modernity as náttúruperlur. Tourist Studies 13: 172–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarles, Caroline. 2009. Becoming Tourist: Renegotiating the Visual in the Tourist Experience. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27: 465–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurðardóttir, Sigrún Alba. 2020. Poetic Storytelling in Contemporary Photography. Relation to Nature and the Poesis of Everyday Life in Works of Selected Artist in Iceland and Other Nordic Countries. Arts 9: 129. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1973. On Photography. New York: Rosetta Books. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).