Abstract

This article expands on a poem written by one of the central figures in modern Hebrew literature, Nathan Alterman (1910–1970), entitled “About a Senegalese Soldier” (1945). Providing the first English translation of this poem and its first (academic) discussion in any language, the article analyzes the poem against contemporary geopolitical, historical, and literary backgrounds. The article’s transdisciplinary approach brings together imperial and colonial studies, African studies, and (Hebrew) literature studies. This unexpected combination adds originality to mainstream postcolonial perspectives through which the agency of the Senegalese riflemen [Tirailleurs sénégalais] has been often discussed in scholarly research. By using a rich variety of primary and secondary sources, the article also contributes to a more elaborated interpretation of Alterman’s poetry. This is achieved through embedding the poem on the tirailleur in a tripartite geopolitical context: local (British Mandate Palestine/Eretz-Israel), regional (the Middle East), and international (France-West Africa). The cultural histories and literary traditions in question are not normally cross-referenced in the relevant research literature and are less obvious to the anglophone reader.

1. Introduction

Scholars in the field of modern Jewish literature agree that considering the multiplicity of geographies, languages, cultures, and socio-political experiences involved, there is no such distinctive body of literature or even a universally accepted definition for this literature (Jelen et al. 2011; Wisse 2003; Levy and Schachter 2015). “What unites the subjects of these studies is not a common ethnic, religious, or cultural history”, argue specialists in the field, “but rather a shared endeavor to use literary production and writing in general as the laboratory in which to explore and represent Jewish experience in the modern world” (Jelen et al. 2011, p. 2). While within this multiplicity, modern Hebrew literature constitutes a sub-category, which is naturally more limited in extent in terms of writers and readership because of its language choice (Alter 1975), this sub-category is not less diversified in every respect. Modern Hebrew literature (as developed over the last 200 years in Eastern and Western Europe and in pre-state Israel) is mostly a secular tradition based on a constant dynamic of continuity and innovation and also features considerable fragmentation. Some of its overlapping themes, nonetheless, include the relationship between the modern Hebrew language and biblical Hebrew, reflections on the politics of identity, places and events, reflections on Zionism between romanticization and de-romanticization, and modern urban existence (Anidjar 2007; Bar-Yosef 1996; Govrin 2019). This new or secular Hebrew literature, as Dan Miron has pointed out, “always regarded itself as the true and legitimate custodian of national literary creativity”, appointing itself as “a watchman unto the House of Israel” [tsofe leveyt Israel], that is, “an institution responsible for the moral and cultural well-being of the nation” (Miron 1984, p. 58). In addition, following pogroms in Eastern Europe, the migration of Jewish communities and the Holocaust, Ottoman and British Mandate Palestine, and independent Israel by the 1950s became the main center of Hebrew language creativity.

Considering these thematic concerns and the geographic backdrop of modern Hebrew literature, it is safe to say that sub-Saharan Africa, together with the Far East and most of southern America, were not normally included within its cultural spheres of activity and linguistic consciousness. The familiarity of Hebrew-speaking communities with modern European colonialism was also limited beyond the direct experience in British Mandate Palestine/Eretz-Israel, especially regarding tropical Africa and its bilateral relations with the dominant European powers. This political and socio-cultural situation naturally affected the meagre representation of southern geographies in modern Hebrew literature, especially by the 1940s—and therein lies the contribution of this article.

At the heart of this article stands a poem of one of the key figures in modern Hebrew literature and poetry, Nathan Alterman (1910–1970), entitled “About a Senegalese Soldier” (written in 1945). Providing the first English translation of this poem and its first (critical) discussion in any language, the article scrutinizes the poem in light of contemporary geopolitical, historical, and literary trajectories. By embracing a transdisciplinary approach that combines (Hebrew) literature studies, African studies, and imperial and colonial studies, the article adds to mainstream postcolonial perspectives in an original way through which the agency of the Senegalese riflemen [Tirailleurs sénégalais] has been often discussed in scholarly research. It also provides an unconventional interpretation of Alterman’s poetry through the intertwining of this poem with local (Palestine/Eretz-Israel), regional (the Middle East), and international (France-West Africa) histories. The involved geopolitical histories, cultural backgrounds, and literary traditions are not normally brought together, and their cross-referencing is less obvious to an English readership.

2. The Poem’s Background

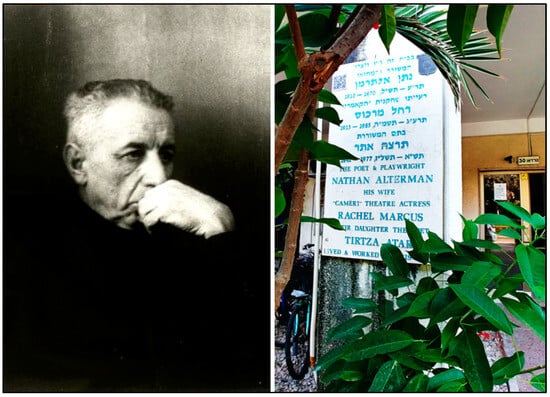

Nathan Alterman, one of Israel’s most renowned poets, was also a playwright, translator, and journalist who reflected on contemporary political events. Although he spent most of his life in Tel Aviv while never holding any elected office, he boasted a transnational background that included a childhood in Warsaw (then Russian Empire) and studying Life Sciences at Sorbonne and Agronomy in Nancy (Laor 2013) (Figure 1). Alterman was extremely active and influential in the local cultural and political arena both during the British Mandate in Palestine and after the establishment of the modern State of Israel in 1948. Following the end of the Second World War, in June 1945, he wrote the poem “About a Senegalese Soldier” [tirailleur sénégalais], which is the focus of this article. The term “Tirailleurs sénégalais” refers to the colonial infantry recruited in sub-Saharan Africa (initially from Senegal and subsequently from other sub-Saharan regions of the French colonial empire) from 1857 to the early 1960s to take part in the colonial campaigns led by France. During the two World Wars, the tirailleurs played an active role in the defense and reconquest of French national territories, with close to 400,000 recruits (Echenberg 1990).

Figure 1.

Left: Nathan Alterman sitting in Café Kasit where he used to meet friends and work on a daily basis (courtesy of Meitar Collection, The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection, The National Library of Israel). Right: The marble plaque at the front of Alterman’s home in Nordau Boulevard, Tel Aviv (photo by L. Bigon and E. Langenthal, September 2023).

Alterman’s poem on the tirailleur constituted part of his long-running (24 years) publication of a weekly column in the daily newspaper Davar. This column appeared regularly on Fridays from 1943 to 1967 on the second page of this popular daily, was entitled “The Seventh Column” [Hatour Hashevi’i], and was eagerly read by the contemporary Hebrew-speaking audience. According to a historian–biographer, every Friday at dawn, there was already a queue of thirsty readers waiting at the door of the printing house in Tel Aviv to be the first to obtain his column (Naor 2006). This series of Alterman’s poignant poems were deeply engaged with events that had an influence on the destiny of Jews both globally and nationally, such as diaspora pogroms, the Holocaust, the Jewish community in America, British colonial policy and diplomacy, and the Arab–Israeli War of 1948/War of Independence. The “Seventh Column” series is also characterized by an abstract, sensual quality, often intertwined with creative word plays, puns, and biblical linguistic forms and imagery—to provide essentially humanistic, secular messages.

As artfully featured by Gideon Nevo, a researcher in modern Hebrew literature, this series “[d]ealing with all things public, large or small, written with brilliantly lucid poetic diction, deftly combining wit and pathos, seriousness and jest, empathy and humor, it earned Alterman unprecedented popularity and prestige among the Jewish population in pre-state Israel (the Yishuv) and in the early decades of the Israeli state” (Nevo 2011, p. 237). Through Alterman’s translations of classical works (from German, Russian, Polish, English, and French) and through his critical interpretation of global news, he was the one who made the world accessible to the contemporary educated audience. The “Seventh Column” series constituted the “eyes and ear” of the Yishuv on the world. These qualities brought, and still bring about, a thriving discourse in Alterman’s work and extensive coverage in a variety of Israeli popular and scholarly platforms.

However, as Alterman’s poems are widely celebrated, to the authors’ surprise and to the best of their knowledge (L. Bigon and E. Langenthal), the poem, “About a Senegalese Soldier”, has never been discussed so far on any platform. The authors can only assume that the reason for this historiographic void is that the subject of the poem is focused on a phenomenon (specific riflemen), politics (world level), and linguistic spheres (francophone) beyond an immediate relevance, general knowledge, and daily acquaintance by the average pre-state/Israeli reader (then and now). In Israel, the associated histories (and daily media coverage) of sub-Saharan Africa in general or French-speaking West Africa, in particular, are normally unknown unless someone makes a conscious, special effort to explore them. Moreover, at the time of the writing of the poem on the tirailleur, the dramatic consequences of the Second World War in terms of the systematic genocide of Jews in Europe were garnering attention in pre-state Israel, which overlapped with the British colonialist combat against “illegal” Jewish refugees who fled to Palestine, as well as growing Israeli–Arab nationalist tensions (Halamish 2016). Therefore, this poem has bypassed the local radar and never obtained the attention it deserves. For this reason, and also because so little of Alterman’s literary output ever appeared in any language other than Hebrew, the authors are enthusiastic to revive the poem through the current translation for the anglophone reader (Figure 2).

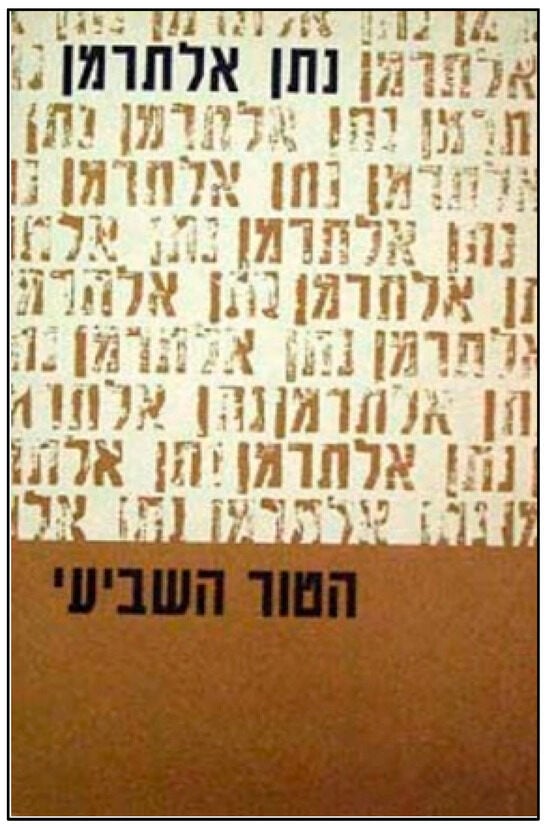

Figure 2.

The book cover of The Seventh Column [Hatour Hashevi’i]; Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House Ltd.: Tel Aviv, 1977 (Alterman 1977) (courtesy of Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House).

The authors’ (L. Bigon and E. Langenthal) English translation of the poem is based on the Hebrew original published in Nathan Alterman, The Seventh Column [Hatour Hashevi’i]; Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House: Tel Aviv, 1977 (pp. 171–74). This book volume (A) brought together all of Alterman’s columns that appeared in the Davar newspaper between 1943 and 1948. Its first edition was published by the same press in 1948 as a gesture to Israel’s independence. The Press promised its audience a free copy of the book in return for an annual subscription to Davar, which immediately doubled the number of subscribers for that year. The authors warmly thank the Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House and Alterman’s grandchildren, Nathan Slor and Yael Slor Marzuk, for their authorization to translate and publish the poem. The authors are also indebted to Alan Clayman for his revision of our English translation and good advice. The Hebrew original is printed in parallel to the English translation.

3. The Poem on the Tirailleur: Original and Translated Versions

| “על חיל סנגלי” לנתן אלתרמן (תרגום המחברות) | “About a Senegalese Soldier” by Nathan Alterman (translation by L. Bigon and E. Langenthal) |

| שגיס למלחמת העולם ואחרי הנצחון שלחוהו למערבולת המהומות והתנגשות האינטרסים הבריטיים-צרפתיים בלבנט. | Who was recruited for the World War and after the victory he was sent into the maelstrom of riots and the clash of British–French interests in the Levant. |

| א | A |

| בקצוי סנגל, בקצוי סנגל, | In deepest Senegal, in deepest Senegal, |

| סנגלי קטן | A little Senegalese |

| גדל, גדל. | Grew up, grew up. |

| עלי תמר טפס ורחץ בגל. | He climbed a palm tree and bathed in a wave. |

| צוננים הגלים בקצוי סנגל. | Cold are the waves of deepest Senegal. |

| אחר כך בא פקיד, בא פקיד קולונילי, | Then came an officer, a colonial officer came, |

| וקשר עליו חבל עבה סנגלי. | And tied a thick Senegalese rope on him. |

| אחר כך הוא עבד במטעי אננס, | Then in pineapple plantations, he worked, |

| ותבות-על-תבות על גבו עמס, | And boxes upon boxes on his back he loaded, |

| וככלות כחותיו | And when his strength expired |

| מן הפרך נס. | From forced labor, he escaped. |

| אחר כך הוא בשוט עלי ארץ גלגל. | Then with a whip, he rolled on the earth. |

| ארכים השוטים בקצוי סנגל. | Long are the whips in deepest Senegal. |

| אחר כך, בהזעק העמים את חילם, | Then, when the nations called their armies forth, |

| הוא גיס להציל את תרבות העולם. | He was called up to save the civilization of the world. |

| ב | B |

| הוא חתר בעשן, הוא כרע ברעמים, | He strove in smoke, he knelt beneath the thunder, |

| ושפתיו השחורות נתכסו דמים. | His black lips were covered with blood. |

| אך בכובע סובטרופי, בכובע סובטרופי, | But in a subtropical hat, in a subtropical hat, |

| הוא צעד בתוך חיל השחרור האירופי, | Within Europe’s Liberation Army, he marched, |

| והסבר לו היטב, כל העת, כל העת, | And it had been explained to him well, at all times, at all times, |

| כי בשביל התרבות | That for civilization |

| הוא לוחם והוא מת. | He fights and he dies. |

| ועת פתע הקטל נפסק ונדם, | And when suddenly the slaughter stopped and fell silent, |

| הוא הבין כי נצלה כבר תרבות האדם. | He understood that human civilization had already been saved. |

| ג | C |

| אז אמר אל נפשו: “למנוחה לא הסכנת. | Then he said to his soul: “You are not used to rest. |

| נוחי קצת”...והיה זה בליל | Rest a little bit”… it was at night |

| בלבנט. | In the Levant. |

| והיה זה בליל סכינים ופגיון, | And it was a night of knives and daggers, |

| ליל קונצסיות, ליל נפט, | Night of concessions, night of oil, |

| ליל אכספרטים והון. | Night of experts and fortunes. |

| לילה בריטי-ערבי-צרפתי בלבנון. | A British–Arab–French night in Lebanon. |

| כן, | Yes, |

| אחד מלילות המזרח התיכון. | One of the Middle Eastern nights. |

| ד | D |

| …עת גררוהו אל בית החולים עלי גב, | …When on his back they dragged him to the hospital, |

| הוא נסה להבין מה קרה, אך לשוא... | He tried to understand what happened, but in vain… |

| בראשו הזב-דם נתערבו בגלגל | In his bleeding head were mixed in a circle |

| יריות, הפגנות ותימרות סנגל. | Shootings, riots and billows of Senegal. |

| סנגל וצרפת! סנגל ואנגלים! | Senegal and France! Senegal and Englishmen! |

| סנגל של קטנים, בינונים וגדולים! | Senegal of adults, youths and children! |

| סנגל של אתמול, סנגל של עתיד, | Senegal of yesterday, Senegal of the future, |

| סנגל של נצחון בעלי הברית! | Senegal of victory for the allies! |

| “אבא, שמח,—הוא דמדם—אבא, שמח נא וצהל. | “Father, be happy,—he was hallucinating—father, be happy and rejoice. |

| העולם סנגל! השלום סנגל! | The world is Senegal! The peace is Senegal! |

| ואימפריות שלמות—הה, שמחה וגילה לי! – | And whole empires—ha, to my joy and gladness! – |

| מדברות ומבינות אך ורק סנגלית! | Speak and understand only the language of Senegal! |

| ועולם נאבק וגבר ונגאל, | And the world has struggled and won and been redeemed, |

| בשבילך, סנגל! בשבילך, סנגל!” | For you, Senegal! For you, Senegal!” |

| ה | E |

| כך דמדם, עד נדם במסוה-כלורופורם, | That’s how he hallucinated, until he died under a mask of chloroform, |

| ושאלת הלבנט | And the Levant Question |

| אז עלתה אל הפורום. | Was then raised to the forum. |

| והתחילו בזו השאלה מדינים | And in this question Senegalese representatives |

| נציגים סנגליים, | Had started to discuss, |

| אך | But only |

| לבנים. | Whites. |

4. Poem’s Analysis

In its topic and subject, Alterman’s poem provides an unexpected, exciting Archimedean point regarding three geographic and cultural spheres: the local (the Jewish population in Mandatory Palestine/Eretz-Israel), the imperial–colonial (France and its overseas territories in sub-Saharan Africa), and the regional (Middle-East). Concerning the local sphere, founded at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Hebrew Israeli literature of the late 1940s and 1950s was essentially modernized and creative, but at the same time, in a confused state. As portrayed by Dan Miron, the thriving centers of this literary production in Eastern Europe came to an end due to the repression of Hebrew and Zionism by the Soviet Union and the Nazi invasion of Poland. Following the destruction of European Jewry in the Second World War and the establishment of independent Israel literary thinkers were in turmoil (Miron 1984, pp. 57–58). As a result, these thinkers were preoccupied with substantive questions about the nature of this body of literature, its identity and future prospects, and its affiliation to previous literary traditions, history, Eretz-Israel, and the Diaspora. These Hebrew writers, thus, “[were] lacking in the resonance provided by European and wider Jewish cultural resources”, says Miron, and “[t]heir writing was assumed to be limited to their immediate experience, which did not reach even to the various aspects of the Yishuv” (Miron 1984, p. 58). This local background highlights not only the innovative aspect of Alterman’s choice of the tirailleur but also partly explains the relative silence of the poem in terms of winning public attention.

As for the imperial–colonial sphere, Alterman’s viewpoint on the tirailleur is important as an external commentator to the phenomenon, which was highly sensitive since the Senegalese regiments were large, ethnically diverse, and experienced contradictory situations in the French colonial army (Echenberg 1990; Mabon 2002). The artistic repertoire of the almost essentially bilateral conversation during the 1940s between France and its French West Africa territory (AOF) concerning the tirailleurs was somewhat unbalanced. On the one hand, in retrospectively, it took the form of a bulk of visual and literary representations in the exoticist–infantile manner. Examples of these are, inter alia, the “petit-nègre” (Ruolt 2017; Amedegnato and Sramski 2003), “Y’a bon Banania” (Donadey 2000; Dufour and Laurent 2008), and “Tintin au Congo” (Abomo 1993). As a cultural icon in France, the original advertising of the “Y’a-bon-Banania” logo used by the food company in 1915 was reproduced in the decades to follow, and, to this day, the original black and white publication of Hergé for Tintin au Congo (1931) (Hergé 1931) has been revived in color since 1946. On the other hand, the contemporary artistic repertoire took the form of subaltern, small though vociferous voices, such as Senghor’s call to his brothers-in-arms (in Poème luminaire, 1948) to stand tall in front of French humiliation, while angrily “tearing the Banania’s laughter from all the walls of France” (Senghor 1964). By the 1990s, the latter voices had been crystalized to create an intellectual movement of ethnic literary studies (including other African, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American writers). Celebrating difference while asserting their cultural heritages in opposition to the mainstream literary canon and assimilation, these writers were “boldly claiming their place in the academy, demanding critical attention and respect for neglected literatures that they jealously claimed as their own” (Kramer 2011, p. 303).

By the 1940s, however, the Franco–African political and socio-cultural negotiations regarding the tirailleurs—including the derivative artistic expressions of these bilateral negotiations—had already engaged much of the in-between gray tones, for instance, the Thiaroye massacre in 1944 and its critical postcolonial representations [10] [24]. Yet, the postcolonial critique of the contemporary atmosphere, including many voices in the intellectual movement of ethnic literary studies, had become rather predictable and repetitive, if not boring (e.g., Ruolt 2017; Amedegnato and Sramski 2003; Donadey 2000, among other publications). While “About a Senegalese Soldier” opens with a seemingly colonialist, romanticized, idealistic, and naive bias about the pre-colonial past in Senegal, this prelude has a purpose. Alterman designs this pre-colonial atmosphere to highlight the contrasting, subsequent human suffering, both physical and emotional, of colonized populations under European imperialism: suffering that accelerates for the indigenous infantry during the (Second World) War (Echenberg 1990; Scheck 2005; Diop 1981). With great empathy for the challenging destiny of the tirailleur, who in this case was positioned in the remote, disconnected environment of the Middle East, merely to serve European strategic and economic interests, Alterman mocks both the French mission civilisatrice (Conklin 1998) and, more generally, Western hypocrisy and racism.

This positioning of the tirailleur by Alterman takes the reader to the third geographic and cultural sphere to which Alterman’s perspective contributes, that is, the Middle Eastern context. Here, his perspective is not only literary but is also based on direct and indirect personal experiences in the face of regional events and politics. As for the presence of the tirailleurs in this region, as aforementioned, these troops served French military interests on many fronts. During the Second World War, they participated in the Battle of France in 1940 as well as in all the battles led by Free France, including actions in Gabon (1940), Bir-Hakeim (Italian Libya, 1942), and Provence (1944). In addition, the tirailleurs sénégalais constituted part of the Armée du Levant during the French Mandate (including of Vichy France) of Syria and Lebanon, especially between 1920 and 1941 (afterwards till 1945, locally recruited Arab and Circassian troops took the heavy share, to be merged in the armies of post-independent Syria and Lebanon) (Albord 2000; Mollo 1981). Upon the establishment of this Army, which constituted four divisions in all, an infantry division from southern Anatolia was mobilized in the Middle East and included the seventeenth regiment of the tirailleurs. Interestingly, this military episode is echoed in the semi-autobiographic short story “Sarzan” (a typo of “Sergeant”) of the celebrated Senegalese writer Birago Diop, which opens with the hero’s itinerary as a tirailleur: from Dougouba and Kati in French Sudan (Mali) to Dakar, Casablanca and then to Fréjus in southern France and, finally, to Damascus (Diop 1961, p. 174). In this story, inspired by the indigenous traditional literary genre of the “conte” (a short narrative with a moral lesson), this geography serves the hero to state his international experience gained through military service, from the “margins” of the French colonial empire to its “center”, as one who has seen the world.

However, Alterman’s sharp anti-European critique, while empathizing with the tirailleur, does not represent the high moral tone taken by a white intellectual who stands for the subaltern, such as in the case of Jean-Paul Sartre, for instance (e.g., Jules-Rosette 2007; Etherington 2016); it rather comes from the position of a colonized subject who had been directly frustrated by the British regime and the fatalistic outcome of the Second World War for his people, for example, against the fact that during the British Mandate and with its permission, in 1941, the Mufti of Jerusalem Amin al-Husseini visited Hitler in Germany (Kessler 2023; Aderet 2017), and eleven days after the death of Hitler in Berlin’s Führerbunker, Alterman published a poem in his “Seventh Column” in the daily newspaper Davar (May 1945) entitled “And if it will be required—[we will combat] Alone!”; the poem borrowed the British rhetoric of the anti-Nazi fight to inspire the Jewish fight against the British regime in Palestine/Eretz-Israel (Alterman 1945).

The 38-year-old Alterman was recruited during the battles of the Arab–Israeli War of 1948/War of Independence at the end of August 1948. Despite his age and status (the military leadership sought to keep him away from the actual fighting), he refused to serve on the home front as a “culture officer” and so was posted close to the Egyptian front near Kibbutz Gat in order to repel the Egyptian invasion. His memories from this experience were included in the poem “Parking Night”, published in 1957 in the collection entitled “The City of the Dove” [‘Ir Hayona] (Amior 2018). Alterman’s acquaintance with Moshe Dayan, a military leader and politician (1915–1981), on the eve of this War (Amior 2018) (Figure 3) brings us back to an almost unknown episode that is associated with the Armée du Levant and the tirailleurs’ part in it: while the eye patch became Dayan’s trademark, archival evidence that was released about seventy years after the events (in 2013) includes his injury and hospital reports (Hetzroni 2013). In the summer of 1941, Dayan was asked by the British Army to join a local unit that would operate together with British forces in Syria. The instruction was to seize strategic bridges in the area of the village of Iskenderun (today in Turkey) as part of the British invasion of Syria and Lebanon against the Armée du Levant under the Vichy regime. There, during a shootout, he lost his left eye.

Figure 3.

Nathan Alterman (right) and Moshe Dayan (left) in the Negev Desert in 1948, following the Egyptian invasion of the Negev a day after Israel’s Independence (Courtesy of Nadav Mann, BITMUNA. From the Shmuel Dayan collection. Collection source: Zohar Betzer. The Pritzker Family National Photography Collection, The National Library of Israel).

According to Dayan, when they reached a built-up area that they were supposed to occupy, the force first encountered a French officer and a Senegalese tirailleur together with gunfire from other French forces. “I pointed the French machine gun that I had in my possession at them and looked through the binoculars in order to determine their exact location, at which moment a bullet from theirs hit my eyes and hands and I lost the ability to act.” Following Dayan’s shooting, the French forces were repulsed. “I hereby submit to you a full report on my above-mentioned actions and express my wish to continue serving as best I could in the British military forces”, he wrote (Hetzroni 2013). What could be learnt from this meeting between Dayan and the West African rifleman under such conflicting circumstances? Apart from teaching us about ever-unexpected international and transnational connections, this “crossing history”/histoire croisée (Werner and Zimmermann 2006) mostly highlights the shared fate of these two types of tirailleurs. Standing on both sides of the barricade and risking their lives on the front lines of the battles, these colonial soldiers well served the European imperial interests in the Middle East—in a vortex of blood and greed as artfully phrased by Alterman in the poem above.

Another shared fate, as noted, for instance, by the political philosopher Frantz Fanon ([1952] 1986) and Professor Ali Mazrui (1980) in his early career, who compared transatlantic slavery and the Holocaust, was that there is an affiliated destiny between African and Jewish histories. In the second half of the 1940s, Alterman’s critique of the British government under the Labor Party became more strident. He often railed against the then Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, perceiving his positions as pro-Arab, anti-Zionist, and even antisemitic (Laor 2013). During these years, Alterman’s poetry focused on the situation of the Jews in postwar Europe. A prominent poem, for example, which also opened the Seventh Column, was inspired by an article published in a local newspaper (1946) following a journalist’s meeting with Jewish children who survived the Holocaust in Poland. It included a photograph of a boy nicknamed “Abramak” (in Polish, for Avram/Abraham) sitting on a staircase, where he slept on account of his fear of going to bed after seeing his family members murdered in their beds. The following week, Alterman published the poem “On the boy Abram (as notified by Laor 2013, pp. 311–12; based on Samet 1946; for the poem see Alterman 1977, pp. 15–18).

In light of the inclusion of (post-)colonial studies, cultural criticism, and subaltern studies within the mainstream of many disciplines in the humanities, including in general literature, it is interesting to examine the response of Hebrew literature and criticism to this fashionable trend. One of the prominent characteristics of the adaptation of postcolonial critique in the Israeli literary context is the impact of this critique on identity politics in Israel. While one might have expected the “projection” of key postcolonial works—such as Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (Fanon [1952] 1986)—on the Israeli–Palestinian relations or on Jewish–Arab relations within the Green Line, such literary expressions are actually rare (e.g., Monterescu and Monterescu 2011). Not only that Israeli scholars in the literature, like in most of the humanities, lack an adequate historical background in global European colonial and imperial studies and in world history (in contrast to Land of Israel studies and Middle East studies) but also African studies departments in most Israeli universities are non-existent or were recently closed. The more frequent result, however, of the projection of postcolonial literary critique on the politics of identity in Israel concerns the tension within Jewish society between those of Ashkenazi (European) origin, who take on the role of the elitist “whites”, and those of Mizrachi (Oriental, or Eastern) origin, who take on the role of the marginalized “blacks.” Mentions of “colonialism” in this context, or of Frants Fanon, for instance, are numerous and include Hebrew literature criticism (Peled 2010), Hebrew children’s literature (Keren-Yaar 2007), Mizrachi music (Oppenheimer 2011), and Mizrachi poetry (Snir 2011).

Even the most contemporary research on Alterman’s “The Seventh Column” from a postcolonial perspective, conducted by the Hebrew literature scholar Gideon Nevo, also projects this politics of identity on Alterman’s writing (Nevo 2021). This is against the background of the question of “Orientalism”, a concept that has been developed in view of modern European imperialism. Yet, in its projection on the Israeli social reality, the concept lost most of its original imperial context. At the same time, Nevo’s research is innovative precisely because he developed the concept of “Orientalism” in light of the intra-Israeli Ashkenazi–Mizrachi tension (Nevo 2021). This is after Edward Said, in his seminal book Orientalism (Said 1978), erased the history of Jewish communities from the history of the Middle East, along with erasing the history of other non-Arab minorities (Ibn-Warraq 2003, 2007). This is at the expense of creating binary opposition between Western Europe and the essentialized Arab Middle East (Ibn-Warraq 2007). Through the analysis of the poem on the tirailleur, this article, thus, contributes to bringing back the discussion of Alterman’s work in the context of world history, imperial–colonial studies, and area studies.

5. Conclusive Note

As authors (L. Bigon and E. Langenthal) who are immersed in the cultures in question and disciplines, both professionally and personally (an Israeli-based collaboration between a (post-)colonial studies and African studies scholar and a philosopher of European thought), we have been able to reframe the poem and put it in the foreground for the first time. This is in terms of the already rich literature concerning both Alterman (mainly in Hebrew) and the tirailleurs (mainly in French and English) and making the poem accessible to anglophone readership. Through an analysis of the poem using a rich variety of primary and secondary sources, the article has brought together unexpected geographies (British Palestine/Eretz-Israel, the Middle East, France, sub-Saharan Africa) while stretching historical, socio-political, and cultural trajectories around the poem. Against the present reality of a revival of antisemitism in Western Europe on the one hand (Alexander and Adams 2023; Cohen 2023) and, on the other hand, the metamorphosis of the “institution” of the tirailleurs under the umbrella of ECOWAS with a recruit of Senegalese diambers/soldiers to manage conflict in post-coup Niger (Rédaction Africanews and AFP 2023), we assume that the relevance of Alterman’s poetry will stay alive.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing, L.B. and E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abomo, Marie Rose Maurin. 1993. Tintin au Congo ou La nègrerie en clichés. Textyles 1: 151–62. [Google Scholar]

- Aderet, Ofer. 2017. Never-Before-Seen Photos of Palestinian Mufti with Hitler Ties Visiting Nazi Germany. Haaretz. June 15. Available online: https://www.haaretz.co.il/blogs/oferaderet/2017-06-13/ty-article/0000017f-f8aa-ddde-abff-fcef9bae0000 (accessed on 5 November 2023). (In Hebrew).

- Albord, Maurice. 2000. L’Armée française et les États du Levant: 1936–1946. Paris: CNRS Éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Jeffrey C., and Tracy Adams. 2023. The Return of Antisemitism? Waves of Societalization and What Conditions Them. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 11: 251–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alterman, Nathan. 1945. And if it will be required—[we will combat] Alone! Davar (The Senenth Column), May 11, p. 2. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Alterman, Nathan. 1977. The Seventh Column [Hatour Hashevi’i]. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Alter, Robert. 1975. Modern Hebrew Literature. West Orange: Behrman House. [Google Scholar]

- Amedegnato, Sénamin, and Sandra Sramski. 2003. Parlez-vous petit nègre?: Enquête sur une expression épilinguistique. Paris: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Amior, Hezi. 2018. “Parking Night”: Nathan Alterman Returns to His Days of Service in the War of Liberation. The Librarians [Ha-Safranim] Newsletter of the National Library, March 27. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Anidjar, Gil. 2007. Semites: Race, Religion, Literature. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yosef, Hamutal. 1996. De-Romanticized Zionism in Modern Hebrew Literature. Modern Judaism 16: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. Daniel. 2023. Wither Philosemitic Europe? Antisemitism after the “Golden Era”. In Antisemitism, Islamophobia and the Politics of Definition. Edited by David Feldman and Marc Volovici. Cham: Palgrave Critical Studies of Antisemitism and Racism, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 251–68. [Google Scholar]

- Conklin, Alice. 1998. A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa 1895–1930. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diop, Birago. 1961. Les contes d’Amadou Koumba. Paris: Présénce Africaine, (For the Conte “Sarzan” see pp. 173–87). [Google Scholar]

- Diop, Boris Boucabar. 1981. Le Temps de Tamango: Thiaroye, Terre Rouge. Paris: Éditions l’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Donadey, Anne. 2000. “Y’a bon Banania”: Ethics and Cultural Criticism in the Colonial Context. French Cultural Studies 11: 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, Francoise, and Bénédicte Laurent. 2008. “Y’a bon Banania!”: Quand le discours publicitaire subsume les représentations des sens linguistiques. Paper presented at Représentation du Sens Linguistique IV (Conference Proceedings), Helsinki, Finland, May 26–30; pp. 122–32. [Google Scholar]

- Echenberg, Myron J. 1990. Colonial Conscripts: The Tirailleurs Senegalais in French West Africa, 1857–1960. Portsmouth: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Etherington, Ben. 2016. An Answer to the Question: What is Decolonization? Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason. Modern Intellectual History 13: 151–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1986. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles Markman. London: Pluto Press. First published 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Govrin, Nurit. 2019. Reading of the Generations: Hebrew Literature in Its Circles. Jerusalem: Carmel. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Halamish, Aviva. 2016. The History and Historiography of the Jewish Settlement in Eretz-Israel under the [British] Mandate Period: Between Uniqueness and Universality. Israel: History, Culture, Society (Special Issue: ‘British, Jews and Arabs under the Mandate’) 24: 375–94. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hergé. 1931. Tintin au Congo. Tournai: Casterman. [Google Scholar]

- Hetzroni, Mathan. 2013. Revealing Moshe Dayan’s Report: This Is How I Lost My Eye in the Battle. N12 News (Mako). July 7 (Based on The Archives of the Israeli Defense Forces following Digitalization of the Archives in 2013). Available online: https://www.mako.co.il/news-military/security/Article-085e8108c68bf31004.htm (accessed on 5 November 2023). (In Hebrew).

- Ibn-Warraq (pen name). 2003. Debunking Edward Said. Available online: https://www.butterfliesandwheels.org/2003/debunking-edward-said/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Ibn-Warraq (pen name). 2007. Defending the West: A Critique of Edward Said’s Orientalism. Amherst: Prometheus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jelen, Sheila E., Michel P. Kramer, and L. Scott Lerner. 2011. Introduction: Intersections and Boundaries in Modern Jewish Literary Study. In Modern Jewish Literatures Intersections and Boundaries. Edited by Sheila E. Jelen, Michel P. Kramer and L. Scott Lerner. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Jules-Rosette, Bennetta. 2007. Jean-Paul Sartre and the Philosophy of Négritude: Race, Self, and Society. Theory and Society 36: 265–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren-Yaar, Dana. 2007. Authoresses Write for Children: Postcolonial and Feminist Readings in Hebrew Children’s Literature. Tel Aviv: Resling. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, Oren. 2023. He Failed to See the Mufti’s Readiness to Use Brutality. The Times of Israel. August 19. Available online: https://www.timesofisrael.com/uk-reveals-herbert-samuels-secret-1937-testimony-on-the-infamous-mufti-of-jerusalem/ (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Kramer, Michel P. 2011. The Art of Assimilation: Ironies, Ambiguities, Aesthetics. In Modern Jewish Literatures: Intersections and Boundaries. Edited by Sheila E. Jelen, Michel P. Kramer and L. Scott Lerner. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 303–26. [Google Scholar]

- Laor, Dan. 2013. Nathan Alterman: A Biography. Tel Aviv: Am Oved & Ofakim. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Lital, and Allison Schachter. 2015. Jewish Literature/World Literature: Between the Local and the Transnational. PMLA 130: 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabon, Armelle. 2002. La tragédie de Thiaroye, symbole du déni d’égalité. Hommes et Migrations 1235: 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazrui, Ali A. 1980. The African Condition: A Political Diagnosis. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miron, Dan. 1984. Modern Hebrew Literature: Zionist Perspectives and Israeli Realities. Prooftexts 4: 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mollo, Andrew. 1981. The Armed Forces of World War II. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Monterescu, Daniel, and Dan Monterescu. 2011. Identity Politics in Mixed Towns: The Case of Jaffa (1948–2007). Megamot 1: 484–517. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Naor, Mordechai. 2006. The Eighth Column [Hatour Hashemini]: A Historical Journey after Nathan Alterman’s Actuality Columns. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad and Tel Aviv University. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Nevo, Gideon. 2011. Eternal Jews and Dead Dogs: The Diasporic Other in Natan Alterman’s The Seventh Column. In Modern Jewish Literatures: Intersections and Boundaries. Edited by Sheila E. Jelen, Michel P. Kramer and L. Scott Lerner. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 237–62. [Google Scholar]

- Nevo, Gideon. 2021. Was Alterman an Orientalist? Prooftexts 39: 78–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, Yochai. 2011. The Melody Still Returns in Your Veins: Music and Judeo-Arabic Identity. Pe’amim: Studies in Oriental Jewry. Special Issue: Arab Jews? A Polemic about Identity 125: 377–407. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Peled, Shimrit. 2010. Appropriation, Opposition, and Consciousness in the Representation of Mizrahiut’ in Israeli Literature, book review of: On the threshold of Redemption, the Story of the Ma’abara: First and Second Generation by Batya Shimony. Jerusalem Studies in Hebrew Literature 23: 321–28. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Rédaction Africanews and AFP. 2023. Senegal Says Its Troops Will Join any ECOWAS Intervention in Niger. AfricaNews. August 3. Available online: https://www.africanews.com/2023/08/03/senegal-says-its-troops-will-join-any-ecowas-intervention-in-niger/ (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Ruolt, Anne. 2017. Le “Petit Nègre des Missions” de l’École du Dimanche, un artefact ludo-éducatif? Studies in Religion/Sciences Religieuses 46: 377–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Samet, Shimeon. 1946. Israel’s Sons in Poland Today. Haaretz, April 19. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Scheck, Raffael. 2005. “They Are Just Savages”: German Massacres of Black Soldiers from the French Army in 1940. The Journal of Modern History 77: 325–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senghor, Léopold Sédar. 1964. Poème liminaire, Hosties noires (1948). In Oeuvre Poétique. Edited by Léopold Sédar Senghor. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, pp. 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Snir, Reuven. 2011. Baghdad, Yesterday: On History, Identity and Poetry. Pe’amim: Studies in Oriental Jewry. Special Issue: Arab Jews? A Polemic about Identity 125: 97–155. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Michael, and Bénédicte Zimmermann. 2006. Beyond Comparison: Histoire Croisée and the Challenge of Reflexivity. History and Theory 45: 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisse, Ruth R. 2003. The Modern Jewish Canon: A Journey through Language and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).