Abstract

In this article, I explore performances of letter writing within the archives of the London-based theatre company Clean Break, who work with justice-experienced women and women at risk. Clean Break’s archive at the Bishopsgate Institute in London contains an extensive collection of production ephemera and letters. Charting the company’s development across forty years of theatre productions, public advocacy, and work in prisons and community settings, these materials of the archive—strategic documents, annotated playscripts and rehearsal notes, production photography and correspondence—reveal the acute importance of the letter to people living on the immediate borderlands of the prison. Despite these generative resonances, however, the epistolary form is very rarely used in Clean Break’s theatre: as the archive reveals, since the company was founded by two women in HM Prison Askham Grange in 1979, stagings of letters have occurred in only a handful of instances. In this archival exploration of the epistolary in three works by Clean Break—a film broadcast by the BBC, a play staged at the Royal Court, and a circular chain-play written by women in three prisons—I investigate what lifeworlds beyond prison epistolary forms in performance propose.

1. Introduction

Letter writing within the prison context has long been an important literary form on several levels—a form of survival as connection, as reflection and revolution, as legal instruction and emotional practice, as interpretation of exterior and interior within the space of the prison.1 It is also a form critically intervened upon by state agents. For what prison correspondence will ever go unread?

Through three works by Clean Break, Women of Durham Jail (BBC 1984), Yard Gal (Prichard 1998), and North Circular (Anonymous 2009), I explore the staging of letters as offering critical sensory dimension to researching and understanding the extent of carceral systems as dynamic forms. If the conditions of the prison foreclose on the possibility of ‘private’ correspondence, what does performance practice make of this? Further, how do the sensory politics of epistolary performance function within activist archives? This research into sensory modes of the epistolary builds on the work of carceral and abolitionist geographers Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2022), Dominique Moran (2015), and Turner and Peters (2015) who remove the ‘prison’ from the realm of the static, positioning it as a series of relationships manifesting across law, education, social exclusion, public policy, and affective registers of trauma in the wake of centuries of racialised and gendered violence. The places of prisons, as these geographers articulate, are seeded within the perception of delineated boundaries between public and private/privatised life. We require decarceral and abolitionist research methodologies that are similarly embodied, dialogic, and porous: epistolary forms, particularly those performed, and whose ‘performance remains’ (Schneider 2001) aggregate in archives, offer breakdowns of the sensory rubrics of public/privatised life. (De)carcerally enfleshed in the archive, these fragments of experience are vital to countering the material virulence of carceral logics.

Epistolary performance strategies within Clean Break’s theatre, though rare, offer an enactment of what performance studies scholars Dwight Conquergood and D Soyini Madison term ‘co-performative witnessing’ as a radical commitment, ‘body-to-body … [involving] a shared temporality, bodies on the line, soundscapes of power, dialogic interanimation, political action, and matters of the heart’ (Madison 2007, pp. 826, 827). Madison builds on Conquergood’s construct of co-performative witnessing to describe it as a shared experience of ‘polyvocal/polylocal stories as they traverse and ‘cut across’ fixed locations to resist, survive, and to (re)make culture and belonging’ (ibid, p. 827). Letters are crucial to this performance matrix, I propose, because they are hypermediations of distance and presence, fixity and dynamism, and are inherently polyvocal and polylocal in ways that articulate the conditions of carceral society. In multivalent, sensory understanding of these conditions, we can begin the work of prison abolition.

This article explores letters as central to this type of witnessing. The aesthetic, political, and ontological concerns of letters and letter writing have occupied a wide range of scholars, activists, philosophers, artists, and prisoners, leading to the generation of rich discourse around the form (e.g., Barton and Hall 2000; Bray 2003; Cline 2019; Crawley 2020; Derrida 1987; Harlow 1992; Luk 2018; Lacan [1958] 2007; Stanley 2004; Yahav 2018). In The Life of Paper: Letters and a Poetics of Living Beyond Captivity, Sharon Luk notes:

For Luk, these indeterminacies place the epistolary within a ‘category of ephemera’ (ibid, p. 22). It is precisely within this ephemerality that letters can explore the ways in which agency becomes constructed, renewed, and intervenes on carceral structures and imaginaries—letters ‘bring elements of social reproduction such as affect, performance, and corporeality to bear on public cultures and political life’ (ibid, p. 22). The paradigm explored here is thus one that proposes the innate ephemerality of the letter in correspondence with the ephemerality of performance; further, this doubled ephemeral is geared toward identifying prison as itself an ephemeral operative. The notion of an ephemeral operative is here meant to mobilise an abolitionist understanding of prison as operating ‘ephemerally’ in the sense that it is one of many performance modes of carceral conditioning, which regulates frameworks for national consciousness, temporalities, and identities not only through identifying deviance, but in large part through what we perceive as ‘positive’ elements in society (for example, ‘education’, ‘family’ (Lewis 2022)). Since the global effects and structures of the prison industrial complex are deeply entrenched in how societies function, the extreme reach of carceral conditioning can appear difficult to grasp and document when considered outside of the spaces of prison.2 I use the term ‘operative’ to illustrate carceral society as functional due to immense physical, affective and psychic labour, and benefitting from power networks that manifest both cryptically and overtly.[T]he ontological indeterminacies that the letter represents, its deconstruction of transparency and thereby of the entire epistemological fabric that presumes it, animate the letter as microcosm for the problem of a most primal human alienation from the essence of knowing or of being known. [… The letter] unravels pretenses of authenticity or coherence of subjectivity, gender, voice, authorship, textuality, genre, consciousness, place, and space-time.(Luk 2018, pp. 7–8)

The notion of prison as an ephemeral operative is compounded when considered alongside performance and its documentation. Within performance studies, the concept of ephemerality has been central to debates around ontologies of performance in relationship to representation and the ‘real’. In a now canonical theorisation of this dynamic, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (Phelan 1993), Peggy Phelan suggests that performance is a becoming through ‘disappearance’: ‘Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does, it becomes something other than performance’ (Phelan 1993, p. 146). This inability to reproduce—a quality which, for Phelan, defines the ephemerality of performance—disturbs codifications of representation as reality. Considered in these terms, performance proposes and enacts identity states, subjectivities and sensory activisms that revolt against the surveillance cultures of carceral society.

This positioning proposes a complex set of questions around archives of performance and/as archiving disappearance,3 which takes on particular relevance when considered in relation to the social and physical disappearance that occurs to those who are serving prison sentences, or who are threatened with imprisonment. As Minou Arjomand notes, ‘The tensions between archives, law, and performance have been a central focus for the field of Performance Studies since its inception[…] [S]tates use the archive to write history over and against the lived experience of marginalized people’ (Arjomand 2018, p. 171). Positioning Phelan’s concept of ephemerality of performance in direct relation to this power matrix of the archive/state, performance studies scholar Rebecca Schneider (2001) examines western constructs of the archive via its Greek root archon, meaning the house of the Head of State. In determining what is housable, the archive determines what histories and identities are valid and in what ways, and how these may be accessed, and by whom. Due to its core quality of ephemerality and disappearance, performance practice resists the archive; yet because the archive operates via processes of exclusion, it requires the disappearance of what is not allowed to be held within it, in order to exist. Therefore, Schneider suggests, the archive becomes itself through a materialisation of disappearance: she terms this ‘performance remains’ (Schneider 2001). Recognising and accessing performance remains can illuminate how we construct memories of the past; even further, performance ‘remains differently’ in such a way that it generates knowledge against fetishised materialities of the archive. In a similar vein, Philip Auslander (2006) defines documentation as performing ‘an indexical access point to a past event’ (p. 9); documentations of performance within the archive become co-constitutive of the performance, in that we accept the document as part of the ephemeral event of the performance—part of the space and time in which the performance occurred.

Researching within Clean Break’s archive, housed in the Bishopsgate Institute, pressurises this now-quantum ephemerality of the performing-performed-prison-letter. Founded in 1895, the Bishopsgate Institute is explicitly committed to the archives of protest, community campaigning, labour and feminist movements; its particular richness as a space for queer archives positions it as an institute that resists conventional forms of representation and documentation. As an institute that protects and opens up public cultures of working against institutionalised, static forms of identity making, Bishopsgate becomes ‘magical’, as Ann Cvetkovich defines it: ‘Ephemeral evidence, spaces that are maintained by volunteer labors of love rather than state funding, challenges to cataloging, archives that represent lost histories—gay and lesbian archives are often “magical” collections of documents that represent far more than the literal value of the objects themselves’ (Cvetkovich 2003). As a researcher, I see this house for Clean Break as allowing its materials an interlocution—a kind of alchemical solidarity—together with other collections that seek to activate personal testimony, the power of trauma and witnessing, and collective agitation against expressions of state power. This is all highly relevant to an archive such as Clean Break’s, which seeks not only to introduce performance into the archive, but to introduce performance against carceral cultures into the institution of the archive.

Where the complex ephemeralities of Clean Break’s archive point to a way of performing prison as a distributed field, the liveness of letters as ‘performance remains’ (Schneider 2001) and ‘indexical access points’ (Auslander 2006) dematerialise prison in a way that records, differently, the material devastation of prison. In choosing to enter the archive, Clean Break both recognises and intervenes on the archive as custodial practice, by proposing an embodied, as well as textual, history of women who were never supposed to be in this archive—only in that other, vast archive of prison records. In showing who was here, how can Clean Break’s archives also perform who is not here, who is not yet, or never-to-be represented, and who would not want to be represented? How might epistolary forms within Clean Break’s performance repertoire suggest a new material practice of being part of a collective organising for justice? Even further, what might live stagings of letters articulate about how epistolarity within carceral contexts can become an abolitionist strategy—an abolitionist form of performance?

In the sections that follow, I investigate in detail the tactics proposed by performing the prison letter as a way to keep the full reach of the carceral system unrelentingly in view. Before addressing the first case study, Women of Durham Jail (1984), we take a brief swerve to the 1850s, where a theatrical device used in Punch and Judy shows provides some scenographic focus.

2. Letter Cloth

Amongst the great swirl of interviews with the rag gatherers, Punch and Judy performers, rat killers, toasting-fork makers, mothers and thieves collected by the journalist and sociologist Henry Mayhew in London of the 1850s, I come across an unusual term. A Punch and Judy Professor describes the cost of ‘a good show at the present time’ as three pounds: ‘that’s including baize, the frontispiece, the back scene, the cottage, and the letter cloth, or what is called the drop-scene at the theatres. In the old ancient style, the back scene used to pull up and change into a gaol scene, but that’s all altered now’ (Mayhew [1851] 1985, p. 298, my emphasis). A drop scene is a canvas or curtain that, when lowered, provides both new background for a scene playing out upstage, and covers for the change-over of the rest of the set downstage.

I had not seen the term letter cloth used for the drop scene before. It appears to be a Punch-specific term, and even then, not one in frequent usage. Going back further to the ‘old ancient style’, the retractable, mutable first layer of the letter cloth also mediated the change in the seemingly final back scene, which in fact would itself be pulled to reveal the very deepest of settings, the jail. ‘But that’s all altered now’: the Professor does not go on to say how the practice has been altered (or at least, Mayhew did not include any further commentary); yet this instantiation of the jail at the backend of the backend, scaffolding all that is played out before you, provides a stunning illustration of the ubiquity and suffusion of carceral structures throughout daily life. And though Punch shows were frequent enough to be constitutive of daily life in London in the 1850s, their relative rarity now does not render them any less fundamental to our contemporary period: a core storyline in which Punch attacks his family, is collared by the police, escapes and goes on a spree through town, in fact, makes Punch a quotidian presence through its particular themes and theatricalities, which formally instruct many of our narratives around crime and domestic violence today. Not quite all altered now.

In this exploration of Clean Break’s archive, I am dropping the letter cloth—even more, I am taking the letter cloth to the letter as theatrical device, in which letters ‘drop’ to mediate and perform the back-back scene of the prison.

2.1. Letter Cloth 1: Women of Durham Jail (1984)

When Clean Break’s founders Jenny Hicks and Jacqueline Holborough met in Durham Prison in the mid-1970s, the very first production they discussed collaborating on was The Trojan Women of Euripides, to be performed in the courtyard of the specialised Category A unit for women offenders, the infamous ‘H-Wing’.4 Years later, following their formal founding of Clean Break in HMP Askham Grange in 1979, Hicks and Holborough’s experiences in the H-Wing shaped the storyline and approach for a television docudrama with the BBC, Women of Durham Jail.

Women of Durham Jail was produced by the BBC’s Community Programme Unit in 1984. An initiative of the ‘Close the H Wing Campaign’, it incorporated staged monologues as letters from four women in Durham prison, splicing these with commentary from Close the H-Wing activists Rita Duncan and Jenny Hicks, as well as from academics Dr Sarah Boyle, Dr Lena Dominelli, and Professor Laurie Taylor. The docudrama begins with a description of the inhumane conditions of the H-Wing. ‘So what kind of women need to be isolated in a prison-within-a-prison?’ the narrator asks. ‘In this programme, four women speak for themselves through their writings and their letters.’ (BBC 1984)

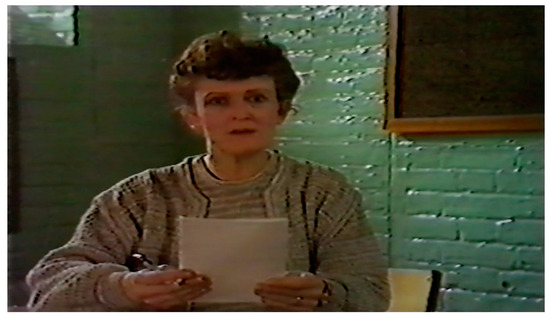

The four women are Judy, Jane, Debbie and Lanky, portrayed by professional actors. Each performs a series of letters written by the ‘real’ Judy, Jane, Debbie, and Lanky. In the final 6 min of the 30 min programme, we see a set of letters from Lanky, Jane (Figure 1), and Judy, followed by appeals from Dr Boyle, Rita Duncan, and Jenny Hicks.

Here, Lanky (the first letter) and Judy (the third letter) focus on Rule 43, or voluntary solitary confinement, and this is ideal for epistolary investigation. The spatiotemporal conditions that these letters propose, performed from (staged) solitary confinement to a BBC broadcast audience, afford a trenchant observation on the way that prison is both mediated by society, and is social mediation: a letter from a person who has experienced solitary confinement becomes part of a text performed in ‘solitary confinement’ on a BBC set to an audience who instantly conflate the depicted setting with actual setting, in large part because it is the setting of the words of the letter—a Durham cell reconstructed in exact detail. This kind of distancing and conflation creates what theatre scholar Lauren Cline calls an ‘extended collective’ offered by epistolary presencing. In an article on descriptions of theatre productions in letter correspondence, Cline writes: ‘In epistolary narratives, audience reception is both discursively immediate—with the narrative “I” depending in unique ways on the “you” being addressed—and spatially distant—with physical separation a necessary precondition of address by letter’ (Cline 2019, p. 241). Lanky, Judy, and Jane’s letters are addressed to a unique recipient; Lanky’s interlocutor, for example, will be with her on Saturday for a 30 min visit. The ‘you’ of Lanky’s letter is first abstracted to the prison population, with intimate knowledge of particular rooms and practices in the prison: ‘when you’re sick, they put curtains up to the windows’, she says. The second instance of ‘you’ is extrapolated into a macro you, via social knowledge: ‘As you know, when you break a prison rule, you get punished.’ The final ‘you’—‘I’ll see you Saturday’—hails the unique visitor, travelling across time and space to join Lanky. The ‘discursive immediacy’ of the letter from solitary confinement breaks through because it is addressed to someone who is both watching a 30 min programme and who will visit for 30 min on Saturday, and who may come to know what it is like to get sick in the prison, honing in on one of the most obdurate definitions of the individual as one who can become incarcerated, through solitary action of wrong-doing. The condition of epistolarity, however, undoes this: the ‘dialogical characteristics of letters and correspondences’, writes sociologist Liz Stanley, ‘involve a performance of self by the writer, but one tempered by recognizing that the addressee is not just a mute audience for this, but also a “(writing) self in waiting”’ (Stanley 2004, p. 212). As viewers receiving a UK-wide broadcast, we are addressed amongst these waiting selves as the unknown visitor, exploding the letter into an extended collective. This epistolarity offers a ‘vexed investment in presence’, as Cline argues, ‘oriented toward a precarious future and an insecure collective’ (Cline 2019, p. 239). Through the production’s weave of letters with Close the H-Wing activist commentary, Women of Durham Jail brings an awareness of women exposed to crisis in isolation through the laying of a sentence on an individual as an individual, where the law’s ‘vexed investment in presence’ should be reoriented toward the collective production of the conditions for incarceration. Not a travelling towards, or a time-limited visitation, but an inhabited field in which we are already agents.LANKY: I’m writing to tell you that the visit on Saturday will only be for thirty minutes. I’m on loss of privileges and in a punishment cell. The punishment cell is also the hospital cell, but when you’re sick, they put curtains up to the windows. I’ve reached my limits. I can’t carry on the way I was, so I booked Rule 43. That’s a form of solitary confinement, except I’d be allowed to stay in my own cell with normal privileges, but kept apart from other prisoners. However, they refused. It was not thought to be in my interests. Not good for me. So I refused to leave my cell. As you know, when you break a prison rule, you get punished. So now I’m on punishment in solitary confinement, the thing I wanted. Except this is much worse than Rule 43 would have been. And twice as much trouble for everyone concerned. And all because they don’t think solitary confinement is good for me. The situation is perverse and ridiculous. [pushes away plate of food]… I’ll see you Saturday. 30 min is better than nothing.(BBC 1984)

Figure 1.

Paola Dionisotti performs Jane’s letters in Women of Durham Jail.

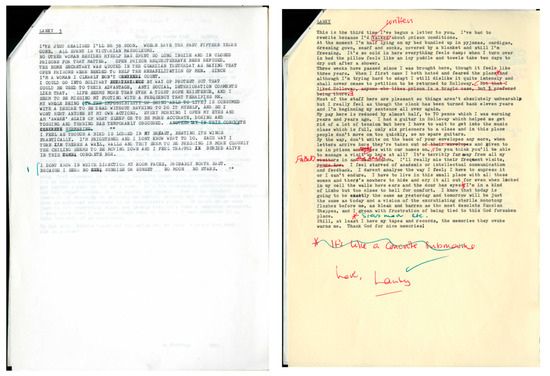

The Clean Break archive holds the original drafts of the ‘Lanky Letters’ (Figure 2), and these are particularly interesting as we can observe the cuts made for Women of Durham Jail. In Lanky’s case, a great deal of text was lost; the original letters hold multiple reflections on the act of letter writing, and these form a substantial part of what was removed for the final cut. The form of the letters reveals one aspect of the epistolary as a chameleonic, porous host of many kinds of writing and technologies of writing: note how Lanky 3 above, with its all capitals, carries the urgency of a telegram. The unnumbered Lanky to the right carries a strong styling as a ‘letter’ in the way that its editor signs off ‘Love, Lanky’ in her own handwriting. There is a live correspondence between the two versions, at least two rounds or two editors (or both), in red and green ink, checking over the text and largely focused on recalibrating metaphors and images. The ‘concrete submarine’ moves from Lanky 3 to Lanky, and is then ultimately rejected—(it does finally dock in the BBC programme). Meanwhile, the cell as ‘Russian Steppes’ in Lanky attracts the text from Lanky 3: ‘I don’t know in which direction my room faces, probably North East. Because I see no sunrise or sunset No moon No stars’. These images both indicate troubled navigation—deep sea submersion, moving coordinates, no coordinates due to the lack of stars—and give a sense of the vast address-less expanse from which letters are sent. Any envelopes that will give the address, as Lanky notes in paragraph six, are removed. A beautifully performative edit—‘By the way, don’t write on the back of your envelopes any more, when letters arrive here they’re taken out of their envelopes’—is also mysterious. How does Lanky know that her interlocutor ever wrote on the envelopes, if she never receives them? This suggests an extended collective of prison staff or others, perhaps, sharing this information with Lanky. It is also an instruction to those watching the BBC programme then and now: language that bleeds out of the container will not be received on the terms intended by the sender.

Figure 2.

Drafts of ‘Lanky Letters’.

As letters of appeal and advocacy, Women of Durham Jail orients the researcher away from approaching archives of letters as repositories of evidence. With no allegiance to evidential legitimacy, these letters refuse any fixed notion of sender and recipient gleaned via methods of historical or documentary positivism. Instead, Women of Durham Jail incorporates theatre-making processes into the practice of research, suggesting what scholar of applied theatre Jenny Hughes calls ‘a methodology that is intimately embedded in creative practice and that, rather than posing answers to clearly defined questions, develops articulations of experience that may not be accounted for by habitual and institutionally bound framings of those experiences’ (Hughes et al. 2011, p. 194). Hughes’s framing of applied or socially engaged theatre as working with ‘practised’ research methods incorporates processes of decomposition as central to working within projects that shift and change in response to how participants are feeling about stories that carry risk in relating. The next section explores a play which decomposes into letters, offering a protection and distance from the difficulty of intimacy within a carceral setting, as well as a call to dive in deeper.

2.2. Letter Cloth 2: Yard Gal (1998)

From the moment that Rebecca Prichard’s Yard Gal starts—‘Ain’t you gonna start it? I ain’t starting it start what? Fuck you man, the play’ (Prichard 1998, p. 5)—Marie and Boo plunge into a kinetic correspondence, dashing and cruising and jumping around the stage as they tell of their days in the ‘endz’ (slang for neighbourhood/local area or streets where you live). Each line’s language hooks off the last in voracious, contagious scramble as the two women bring their tale closer and closer to the audience, and to each other.

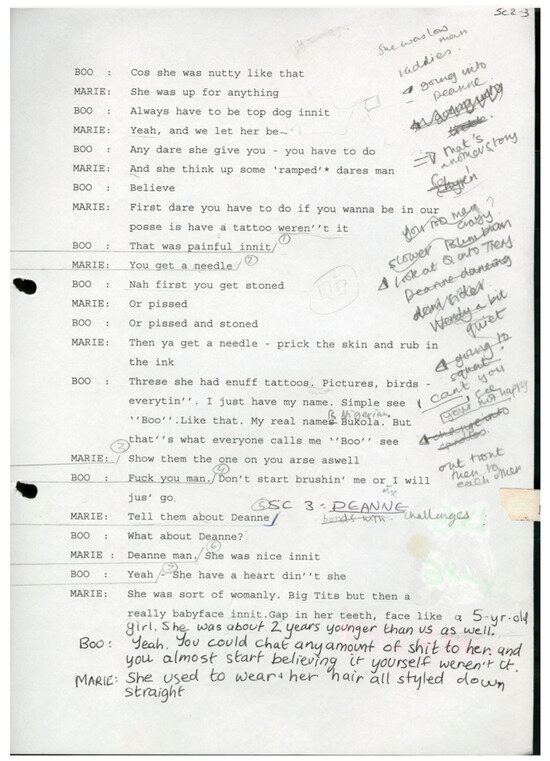

Links of language create a sensory intimacy of ‘facts’ as they become established through repetition as much as Marie and Boo’s recollection. As Marie and Boo cascade through descriptions of their friends, this includes a concession that ‘Yeah. You could chat any amount of shit to her and you almost start believing it yourself weren’t it’ (Figure 3): this sidewinding declaration works to establish the narrative space as just one more in a string of Marie and Boo stories, where the ‘truth’ of the story is its telling in that moment, the entwined kinetics of Boo and Marie, and the audience is there to help the women almost believe it.

Figure 3.

Yard Gal rehearsal notes and rewrites.

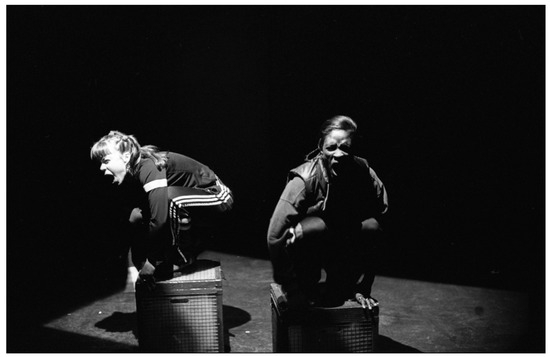

The audience know that Marie and Boo are there to tell a story, but we are not told why and there isn’t any conversation between Boo and Marie that establishes a present moment, only that they can abandon the present (and past) if the conditions are not right. This creates a guarded, protective atmosphere, which suffuses and structures rushes of language and movement. Es Devlin’s laconic set offers a couple of boxes covered in wire grid (Figure 4): the sparse, protected quality of these boxes is immediately archive-like. What does the mesh protect? The durability of these containers becomes tested again and again as Marie and Boo jump around on them. Yet, similar to flight boxes or audiences, they survive, and seem to collect the action of Boo and Marie with each new fold of the story.

Figure 4.

Amelia Lowdell as Marie and Sharon Duncan-Brewster as Boo in Yard Gal (Royal Court). Photography: Sarah Ainslie.

A major fold occurs at the end of Act One, when Marie and Boo tell how at a party their friend Deanne accidentally falls off a high-rise balcony and dies. Marie and Boo are both traumatised, and Marie retreats into silence at the end of the act. Boo picks up the story, but from this point, Act Two becomes a trading of monologues, rather than entangled speech. We begin to see a separation forming between Marie and Boo as their tale becomes an account, told by two parties: Marie killed a woman in a club, Boo took the rap and went to prison. As the audience enters the phase of the story where Marie glasses Wendy, Prichard’s frenetic language slashes with forensic detail. ‘I put the glass in her neck. I turned it and see her flesh go white. I heard her scream but then I realise the scream had come from her mate. Blood was coming from her neck like a waterfall’ (Prichard 1998, p. 47).

Marie’s action in the nightclub ‘Trenz’ comes in the final moments of Act Two; as Act Three begins, ‘Boo drags her chair slightly apart from Marie’ (Prichard 1998, p. 49). And it is here that the letter cloth drops: the majority of the scene becomes de/composed of letters written by Boo to Marie, and Marie to Boo. Where in Act Two, Boo and Marie’s monologues were like dead letters in a sense, never two-way, the epistolary form in Act Three creates a distance that allows them to restitute their conversation. Where flesh ruled the action to this point, we are now presented with bone: ‘In the archive, flesh is given to be that which slips away. Flesh can house no memory of bone. Only bone speaks memory of flesh. Flesh is blindspot. Disappearing’, writes Rebecca Schneider in ‘Performance Remains’ (Schneider 2001, p. 102). By the end of the play, we realise that Boo and Marie never saw each other again. In some ways, their relationship ended half a play ago, and it has been granted this grace to continue via an enfleshed archive of enboned letters.

As the only space where they can now know each other, they suddenly have a chance to understand each other—and this comes through the letter writing. The letters reveal remains of lonely yearning for each other; more than remains, these letters work as commands to remain. In his epistolary treatise on blackqueer lifeworlds, The Lonely Letters, Ashon Crawley undertakes ‘a questing for noncoercive communion, a questing for consent to be otherwise than a single being, a questing to move from unity to multiplicity’ (Crawley 2020, p. 4, emphasis in original). For Crawley, letter writing ‘stage[s] the complexity of thinking and performing the limit and the possibility… [of] experiences of severance, abandonment, of being left behind… these experiences limit, but also occasion, each enclosure and opening and unfolding to what could be imagined to be possible’ (Crawley 2020, pp. 7–8, emphasis in original). In Yard Gal, the inadequacy of the letter is what throws Marie and Boo, and us, into the beginning of the play. Yet, the letters are needed to express the loss, hurt, and love both Marie and Boo feel for each other. Where are you? Where were you? are refrains of the play that can come out through the letters alone. The sensory openings of these letters become a reflexive space—the ultimate effect of this kind of epistolary engagement is, Crawley proposes, ‘a way to practice justice and care with one another’ (ibid, p. 9).

Letters in Yard Gal remind us of the count of time, too, where we have previously been drawn into blitzes of action. Marie and Boo’s sensory-led language complicates quantitative ways of experiencing time: as their world bangs into a wall, feeling the pain and alienation through epistolary form stands in stark contrast to the intoxication of the narrative. These letters as letter cloths are intensely spatialising—Marie and Boo’s environment has become dissonant where it was consonant. In his work on narrative duration, Feeling Time, Amit Yahav writes of epistolary novels as ‘restor[ing] us to an inabstractable duration—you must twine your duration with them, for a summary would just miss the point … restoring to actions their durations, [makes] any moment tied more strongly to the full process of which it partakes’ (Yahav 2018, pp. 25–26). In Yard Gal, the summary action imparted through monologuing in Act Two sets up the letter to once again twine the audience into ‘inabstractable duration’ of carceral spatiotemporalities.

Marie and Boo’s letters navigate what is both instantaneous, and never ending, of the duration between now and then of prison time; as theatre studies scholar Alice Rayner writes of the space between ‘now’ and ‘then’, ‘It is a launching point for the next thing, but it is also a stopping point, a rest, a time to breathe’ (Rayner 2014, p. 33). As a stopping point, the letter gives the longing of both Marie and Boo an action, and a duration to that action—and it does this in noncoercive form. It draws our attention to the moment as processual, not final, not an end point, but a point which can be constantly left (‘Can we go?’—Figure 5) and returned to (‘From time’—Figure 5). Boo and Marie’s letter cloths complicate our often unexamined adherences to historical time; unsuturing the historicising link between then and now is required if we are to confront and destabilise carceral logics.

Figure 5.

Boo and Marie’s letters.

2.3. Letter Cloth 3: North Circular (2009)

The histories of authorship of Yard Gal and Women of Durham Jail each reveal distinct models of creative practice that have informed Clean Break’s practice over the years: in Women of Durham Jail, the letters were written and edited collectively, with final edits coming as part of the exercise of condensing to a 30 min BBC broadcast. Yard Gal was solely authored by Rebecca Prichard following a series of residencies in HM Prison Bullwood Hall, articulating a longstanding element of Clean Break’s advocacy work that involves writers, directors, performers, and theatre artists without lived experience of the criminal justice system in creative dialogue with justice-experienced writers, performers, directors, and theatre artists (for more on this approach, see Perman 2018). In this final section, I explore how the formal concerns of the prison letter informed a Clean Break project from 2009, North Circular, in which twenty-two women at HM Prison Bronzefield, HM Prison Morton Hall, and HM Prison Holloway co-wrote a circular chain-play, in association with Clean Break’s resident playwright Lucy Kirkwood (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

‘Changing Your Story’ at HMP Bronzefield, 2009.

Though not written in epistolary form, North Circular is a play of correspondences. As part of the company’s Changing Your Story project, which developed playwriting talent in prisons and community settings, Clean Break conceived of a three-prison residency. The prompt for the residency was to write a chain-play: the first prison community was presented with a scene written by Clean Break’s writer in residence, Lucy Kirkwood. The writers’ group then wrote the second scene, passing these two scenes to the next prison, where the third scene would be written, and so forth. The resulting play, North Circular, travelled between writers’ groups at HM Prison Bronzefield, HM Prison Morton Hall, and HM Prison Holloway until a full seventeen scenes had been written, and the groups pronounced it finished.

North Circular took as its inspiration Arthur Schnitzler’s 1897 play La Ronde, which staged a sequence of two-hander scenes, each linked to the next by a character. Scene 1, ‘The Whore and the Soldier’, leads to Scene 2, ‘The Soldier and the Chambermaid’, to Scene 3, ‘The Chambermaid and the Young Gentleman’, etc., with the final scene returning to the Whore (together with the Count). As the scene titles suggest, the play exposed attitudes and ideologies around sexual promiscuity and class that animated Viennese society of the Belle Époque. North Circular departs from these themes but retains the A-B, B-C, C-D structure and inserts a magical object (the BAG), in transit from scene to scene.

I include North Circular here as a kind of ‘letter in flight’ that made several rounds, gathering traces of language, image, and characters from twenty-three women. To return to Conquergood and Madison’s work on co-performative witnessing, the act of writing in North Circular enacts registers that are both co-performative, and witnessing, in that the creation of the play resists the fixity of discrete institutional settings to respond to a momentum of voices carried from scene to scene, from prison to prison (Madison 2007). The movement from prison to prison also expresses a current of frequent ‘decanting’ or transporting prisoners from one prison to another, often with very little forewarning. Across the time span of the writing residencies in HMP Bronzefield, HMP Morton Hall, and HMP Holloway, of the twenty-two writers some will have been moved to a new prison (perhaps meeting the next phase of the play in a different writers’ group, though this is not recorded), and some will have been released. In this way, the circular chain-play performatively witnesses a temporality of what I explore elsewhere as the ‘chiasmus of prison transport narrative’ (McPhee 2018, p. 103). The play received a Koestler Bronze Award for Stage Plays and was performed at each of the prisons who participated in the project, as well as at the Southbank Centre by justice-experienced women from Clean Break, together with professional actors.

Very few characters in North Circular look in the BAG, but they are each profoundly invested in it—the BAG never sits in the corner, unnoticed. It is the material magic of this BAG, a thing so troubling, beautiful, and powerful in its thingness, that it magnetises each scene to the next:

Like it was a plant or a flower orsomethingNot literally like a flower but that it like, put a seed in your brain…and from the moment you saw it that seed started to grow, and it made roots go all through your head, into your mouth and your ears and your eyes, in your nerves even, in your fingers and then it sort ofchanged stuff. The world, it changed the world like everything around you suddenly seemed toshinelike the whole world shining like a penny and things felt smoother and tasted nicer and sounded soft and all of it covered in this likeshinenot like a penny actually but like everything was covered in this like gold silky web like a spider’s web but nicer but thinner but invisible but covering everything so you felt so safe and kind and good and happy.And it was always in you and the whole world likeshone[…]And you can’t understand how you even existed before it was there.(Anonymous 2009)

The pulsing thread of this writing—carrying from prison to prison, collective to collective—unfurls in non-linear ways ‘ma[king] roots go all through your head, into your mouth and your ears and your eyes, in your nerves even, in your fingers and then it sort of changed stuff’. Though each group no doubt had their own notion of what might be in the BAG, to me what is in the BAG is the play itself. Some characters want nothing to do with it at first, others get right in there, others are covetous, still others want to know what it is actually worth. When the play finishes, and the BAG stops its trajectory, the character Frankie holds onto it, ‘rocking it like a baby’, but she says ‘I’m without luck, without feeling, without anything’ (Anonymous 2009, p. 33). This final line of the play evokes a sensibility of what we lose when the collective dissipates; it calls to mind activist adrienne maree brown’s concept of ‘emergent strategy’ for social justice initiatives. ‘Emergence emphasizes critical connections over critical mass, building authentic relationships, listening with all the senses of the body and the mind’, she writes. ‘[E]mergence shows us that adaptation and evolution depend more upon critical, deep, and authentic connections, a thread that can be tugged for support and resilience. The quality of connection between the nodes in the patterns’ (brown 2017, pp. 3, 15). The encounter of the chain-play produces an impulse to emerge collectively via these sensory nodes, not just to protect against carceral cultures, but in order to create practices of abolition that resist these cultures. There is extraordinary value in seeing the chain-play in emergence as phases, as transitions, that circumvent ideologies of the atomised individual, and openly articulate prison narratives as crowd-sourced. The form teaches us how to pull the letter cloth down around us to explore the complex materialities of what abolition can propose.

In these ways, the epistolary form in North Circular, Yard Gal, and Women of Durham Jail uniquely evokes complexities of abandonment–connection, of collective–fracture, of reaching–feeling in situations of live or broadcast performance in which audiences are invested in strategies of world making that complicate and undercut the stability of the prison setting. Epistolarity in these works generates a copresence that, when activated in performance, emerges through a reinsertion of distance: when performed, these letters undo distances of time, space, and archive as custodial practices; the distance that appears instead is suddenly the only one that matters, in that it is actually an aching closeness. It is an ache about which something can be done. As such, these letters phrase and fang the ephemeral operative of carceral society, render it clearly, make it sensory, seeping out of the bag. This is critically important to developing an understanding of carcerality as a series of relational, spatiotemporal performatives, which can be intervened upon collectively. Out of their envelopes, ‘you can’t understand how you even existed before it was there’ (Anonymous 2009).

Funding

This research was developed through the UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded research project ‘Clean Break: Women, Theatre, Organisation and the Criminal Justice System’ (AHRC/S011951).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The rich heritage of prison literature includes published letters from, e.g., Martin Luther King Jr., Antonio Gramsci, Oscar Wilde, Nelson Mandela, Angela Y. Davis, Assata Shakur, Jawaharlal Nehru, George Jackson; this article is concerned with letter writing as an embodied form of performance, as considered through the archives of the British theatre company Clean Break. |

| 2 | I discuss this phenomenon at length elsewhere through the concept of ‘carceral atmospherics’ (McPhee 2020). |

| 3 | While there are many responses to the archive-performance aporia, harnessing methodologies from a wide range of disciplines and practices, two important collections from artists and scholars working with performance include Performing Archives/Archives of Performance (Borggreen and Gade 2013) and Artists in the Archive: Creative and Curatorial Engagements with Documents of Art and Performance (Clarke et al. 2018). |

| 4 | For more on the history of the H-Wing, HMP Durham’s maximum-security wing for women, referred to in the tabloid press as “She-Wing”, see McAvinchey (2020), ‘In the Clean Break Archive—Killers (1980) by Jacqueline Holborough’. |

References

- Anonymous. 2009. in association with Lucy Kirkwood for Clean Break. North Circular. Unpublished play. Excerpt printed with permission from Clean Break Theatre Company. [Google Scholar]

- Arjomand, Minou. 2018. Staged: Show Trials, Political Theater, and the Aesthetics of Judgment. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Auslander, Philip. 2006. The performativity of performance documentation. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 28: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, David, and Nigel Hall, eds. 2000. Letter Writing as a Social Practice. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 1984. Women of Durham Jail. BBC Community Programme, February 15. [Google Scholar]

- Borggreen, Gundhild, and Rune Gade, eds. 2013. Performing Archives/Archives of Performance. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, Joe. 2003. The Epistolary Novel: Representations of Consciousness. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- brown, adrienne maree. 2017. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Paul, Simon Jones, Nick Kaye, and Johanna Linsley, eds. 2018. Artists in the Archive: Creative and Curatorial Engagements with Documents of Art and Performance. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cline, Lauren Eriks. 2019. Epistolary Liveness: Narrative Presence and the Victorian Actress in Letters. Theatre Survey 60: 237–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, Ashon T. 2020. The Lonely Letters. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovich, Ann. 2003. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1987. The Post Card: From Socrates to Freud and Beyond. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2022. Abolition Geography: Essays Toward Liberation. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Harlow, Barbara. 1992. Barred: Women, Writing, and Political Detention. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Jenny, Jenny Kidd, and Catherine McNamara. 2011. The Usefulness of Mess: Artistry, Improvisation and Decomposition in the Practice of Research in Applied Theatre. In Research Methods in Theatre and Performance. Edited by Baz Kershaw and Helen Nicholson. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 186–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 2007. The Youth of Gide, or the Letter and Desire. In Ecrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: Norton. First published 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Sophie. 2022. Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Luk, Sharon. 2018. The Life of Paper: Letters and a Poetics of Living Beyond Captivity. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madison, D. Soyini. 2007. Co-Performative Witnessing. Cultural Studies 21: 826–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, Henry. 1985. London Labour and the London Poor. London: Penguin Books. First published 1851. [Google Scholar]

- McAvinchey, Caoimhe. 2020. In the Clean Break Archive—Killers (1980) by Jacqueline Holborough. Women, Theatre, Justice: Perfoming, Organising, Working. Available online: https://www.womentheatrejustice.org/research/research-blog/in-the-clean-break-archive-no-i-the-plays-tell-a-story-decade-and-killers/ (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- McPhee, Molly. 2018. Miasmatic Performance: Women and resilience in carceral climates. Performance Research 23: 100–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, Molly. 2020. Miasmas in the theatre: Encountering carceral atmospherics in Pests (2014). Ambiances: Environnement Sensible, Architecture et Espace Urbain 6: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, Dominique. 2015. Carceral Geography: Spaces and Practices of Incarceration. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perman, Lucy. 2018. Four Decades of Capturing Hearts and Minds with Theatre. Criminal Justice Alliance Blog. Available online: https://www.criminaljusticealliance.org/blog/four-decades-of-capturing-hearts-and-minds-with-theatre/ (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- Phelan, Peggy. 1993. Unmarked: The Politics of Performace. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Prichard, Rebecca. 1998. Yard Gal. London: Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, Alice. 2014. Keeping Time. Performance Research 19: 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Rebecca. 2001. Archive: Performance Remains. Performance Research 6: 100–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Liz. 2004. The Epistolarium: On Theorizing Letters and Correspondences. Auto/Biography 12: 201–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Jennifer, and Peters Kimberley. 2015. Unlocking carceral atmospheres: Designing visual/material encounters at the prison museum. Visual Communication 14: 309–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahav, Amit S. 2018. Feeling Time: Duration, the Novel, and Eighteenth-Century Sensibility. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).