Abstract

This practice-based paper explores the methods of answering the question: what is our collective body? This article offers a case study of collaborative research and seeks to enact a collective body as a means of transgressing and occupying individuated neoliberal spaces of higher education. Understanding the processes through which knowledge is collectively built highlights the in-becoming nature of practice-based research and the enabling forces of this inquiry. The methods enacted access a particular rendering of how we understand ourselves as a collective; we answer the question through doing together. The ways we encounter the collective enable understanding around the shifting boundaries of the individual–collective connection, made palpable by a string. Through playful forms of dissent, such as embodied, remembered, and writing encounters, enable connections with others and inspire a refocusing of our individual practices.

1. Introduction

Through the process of collective writing, the intention of this paper is to explore the act of collaboration as an embodied process. We explore this as a Deleuzian (Deleuze and Guattari 2013) becoming through practice-based research, a stringing-(em)bodying process. Having experienced the potential of creative collaboration, we aim to unpick what this is and what it feels and looks like. Framing the multiple participants involved in this process as one ‘collective body’, we ask how a collective body arrives, moves, and learns.

We also question if it is even possible to ‘articulate’, in an academic format, the embodied flow of the creative process and what occurs between bodies that build the ‘affect’ of connection we are discussing in this paper. The challenge in all creative fields when reaching out into more traditional academic formats is to justify a process that is often ambiguous, messy, and emergent. This paper, therefore, is not a traditional account or summary of findings. Instead, this paper is enacting the practice of our collaboration, intending to share how we create, nourish, and hold each other’s practices within a space that exists in both physical and virtual worlds. This act of collaboration is vital in terms of sustaining and maintaining our separate interests through the need to entangle with and learn through other practices. Working with materials opens up new possibilities to extend our research in ways we may not have initially imagined. It is this process of the “not known” or “that-which-is-not-yet” that (Dennis Atkinson 2018, p. 2) beautifully articulates that aligns with our need to be and collaborate with each other. A desire for ‘adventure’ that Atkinson discusses orients this collaborative practice to the future, pushing us to imagine the ‘more-than’ of our own individual remits.

We draw from feminist new materialist (Barad 2003) and posthumanist (Haraway 1988; Braidotti 1994, 2014) understandings of the body as an emergent, embedded, and entangled assemblage. Body is relational and affective, situated in relation to more-than-human others, and has the potential to form and inform new becomings. In our investigation, we search for a common body in the collective activation of the field. In other words, what we are interested in is less in what the corporeality of our individual physical bodies do and more in the affective field that emerges in collective formation as a body itself. We are interested in mapping how to be-with, think-move, and learn with/in this body in the context of higher education spaces, which are typically individualised. The neo-materialist approach enables us to stay ‘grounded through embodied and embedded perspectives’ (Braidotti 2019) while resisting the reductive recourse to data and quantitative methodologies that would fall flat in capturing the embodied subject as complex assemblages, the common body. The Baradian idea of not being separate from the world but being immersed within it is integral to this methodology, as is the intent to work with materiality, to learn from and evolve through embodied encounters with the more-than-textual and multi-sensory world. For Barad, “agency” is not an attribute of something or someone; rather, it is the process of cause and effect in “enactment” (p. 214): “Agency is ‘doing’ or ‘being’ in its intra-activity. It is the enactment of iterative changes to particular practices—“iterative reconfigurings of topological manifolds of spacetimematter relations —through the dynamics of intra-activity” (p. 178). These concepts and frameworks emerged during the practice session as concepts that allowed us to communicate our understanding of the activation of the collective body without limiting or defining each other’s experience. In the space of this paper, they fulfil a similar role towards the reader.

In recognising that in our collective formation, we are together in our practice, yet we are not one and the same, we recognise, in Braidotti’s words, that we are “embodied and embedded, sexualised, racialised and naturalised in dichotomous systems and hierarchies, but not reducible to those systems alone” (Braidotti 2022, p. 237). In this sense, we have found Braidotti’s concept of affirmative ethics as “a political praxis that enfolds the positivity of difference” (p. 236) and as a way to ethically engage in our investigation from a position of trust “in our collective ability to constitute alternative human subjects and community” (p. 236). Ultimately, this is an ethics that is grounded on solidarity, generosity, and interconnection to imagine otherwise, therefore constituting a potentia “ignited and sustained collectively” (p. 237). In practice, this manifests in socio-material dialogues that actively attend to difference.

We are a group of doctoral and post-doctoral practice-based researchers in art, design, and pedagogy interested in spaces of collective learning. This group comprises people who have differing levels of familiarity with each other but who want to share parts of themselves and their thinking. In our convening, we create space for encounter, for “sustainable and flourishing relations” (Puig de La Bellacasa 2017), and for learning. We gathered for the first time at the end of 2022 on this premise and followed with intermittent convening: critique-based discussion, activation-based practice, and community-building intention. We have developed communal spaces for practice both online and in person. We use a WhatsApp group called Seeders to coordinate our meetings and have met across Goldsmiths College and the University of the Arts London (Camberwell College of Art and London College of Communication). We are interested in cross-pollinating the multiple institutions we are situated within, occupying transience and micro-disruptions. We initiated our meetings to collectively explore learning spaces, and we are interested in translating and testing tools to bring into our own teaching and learning practices.

There are fifteen people that are part of the collective, each feeding into the group, or what we term the ’collective body’, in different registers. Some bear witness to the group in more silent ways, perhaps leaning into conversations on the WhatsApp group but unable to be physically present because of work and life commitments. Others actively engage in conversation on the app, and others regularly meet to physically explore ideas together. Others engage in a hybrid of all of these things. This makes the group dynamic always in process and perhaps best described as a pulsating practice—one that breathes.

It is important to note, therefore, that in this paper, we purposefully identify as a ‘group’ rather than exploring individual identities. This exercise can, therefore, be seen as a case study of this practice. Although the individual experience is integral to the evolving becoming as a group, we are more interested in understanding the potential for opportunities that can be activated in the spaces between and how collective and material agency is garnered when working in this way. The concept of a collective body, therefore, was used as a provocation to think about the dynamics between not only the individual and the group but also the physical and virtual environments we work in. In this sense, the affective field emergent in the materiality and the intensities we entangled with also became, in itself, a body within the collective body, configuring the way we went about making, thinking, and writing. Although, as Seeders, we have worked on various projects, this paper focuses on one event that unfolded over a few in-person and online sessions—the coming together to formulate this paper through praxis.

This paper is written by and intended for those who seek to work collectively or who feel there might be a collective methodology that would help better understand how to work with and against the individuated, metered spaces of capitalist production and patriarchal hegemony. Predominantly, we speak to spaces in higher education but suggest that this research is relevant to a broader range of researchers and practitioners who feel similar limitations apply to their field. This is a collaboration that consists of a group of people that move in and out of connection with each other, is non-hierarchical and equitable, and pivots on the new materialist notion of decentring the human by acknowledging the agency of the material process through which this group is duly entangled.

In recognising the importance of this collective space as a productive resistance to our more traditionally individualised research projects, we wanted to explore the ways in which we can map out these knowledges as collective. What we write about here is determined through the lived experience of attempting to work out what the collective body is, what it does, and what it can do in practice. This paper rehearses the collective, not as a traditional data-gathering and analysis exercise, but instead seeks to use the very processes of talking, writing, doing, and reflecting together on this question as our methods. We are therefore oriented toward giving a critical, embodied, and sensorial account of a collective, affective, and material praxis that is alive in the encounter. This is a praxis that also emerges from the process of collective writing and editing, as well as in the reader, through the process of reading the text. Our intention is to use this text as a rehearsal for practice-based research writing that is grounded in the aliveness of collective praxis—evidence of an assemblage of the sensory and the embodied. This paper, therefore, becomes the practice and evidences ‘doing’ as knowledgeable.

Both these physical and written practices are organised into three parts: arrival, doing, and reflection. This structure was loosely inspired by the structure of a yoga session as a way to acknowledge/summon an embodied presence. We started with the body: we discussed how we arrived in our spaces of practice as a collective body. Then, we worked experientially from this arrival, moving together largely in an unplanned, experimental, and improvised way, generating experiences, feelings, mark-making, and movement. In one of these moving sessions, which we will focus on during this paper, we utilised string as a material to enable a literal entanglement of our bodies. We reflected both in immediate conversation and through writing on a shared sheet of paper. This was then followed by many meetings of writing individually and collectively to unpack the sessions using approaches such as automatic, poetic, corporeal, and affective writing, where we attuned to the echoes and resonances of our practice.

This paper came out of these entangled explorations and therefore follows a similar structure: before we arrive into our collective body, we will ‘roll’ out the mat to contextualise these practice methods. We then move into our arrival, our doing, and lastly, a discussion on this process. Our reflections, which are woven together and throughout in italicised text, form a collective voice. We convened to write this paper, which not only combines and derives from the previous two stages but also aims to be a critical piece that generates a form of thinking we regard as foundational for further development as a collective. As such, this text flows between our multiple voices, which includes the ebb and flow between the theoretical structures of the text, and which hold and care for this praxis. Through this process, the discovery of questioning is activated as a methodology, exercising practice-based research as an embodied process.

2. Rolling Out the Mat

We met transversely in the spaces of the WhatsApp group chat, as well as at 288 New Cross Road at Goldsmiths, the Well Gallery at LCC, Padlet, and in a Google Doc. Initiating our meetings by asking the question “What and where is our collective body?” as both a focus of our inquiry and catalyst for our activities, we situated the very coming together as a group through intention, playful moving-making, and questioning as a premise for a collective dynamic.

Situating such a dynamic in an academic writing context is becoming far more needed and relevant in postcolonial institutional structures, and practitioners often seek support from Deleuzian (Wyatt et al. 2010; Löytönen et al. 2014), posthuman, and new materialist methodologies (Gale et al. 2013) to “think through rhizomatic and zigzagging movements” of more creative approaches to academic research (Löytönen et al. 2014, p. 237). Inspired by the written practices of Löytönen et al. (2014) who “consider the indeterminate and continually shifting, nomadic process of not-knowing in the midst of sometimes striated academic (writing and presenting) practices”, we have also ventured into a ‘fumbling’ practice that seeks to explore “something not-yet-known” (ibid. p. 237). However, where we diverge is through our written practice as a means to generate thinking on the embodied nature of our physical practice rather than as the tool of our practice, as described above. Our body-based approach to practice, therefore, stands in relation to and echoes experimental, experiential, collective, participatory, and performative practices such as those seen and felt in works such as Huddle (Forti 1961) by the American artist, dancer, choreographer, and writer Simone Forti, and the Estruturas Vivas (Live Structures) propositions, namely Rede de Elásticos (Elastic Net; 1973), by the Brazilian artist Lygia Clark.

In Forti’s words, Huddle is a “Dance Construction” (Breitwieser et al. 2014, p. 96), “an object that doesn’t exist in the solid sense and yet it can be reconstituted at any time” (p. 96). It involves an instruction for “six to nine people to bond together in a tight mass while remaining standing and to take turns climbing over the top of the mass” (p. 96). Huddle is a work that, on the one hand, makes those who participate in it feel the physicality of their own bodies, their weight, and gravity as they climb and descend and support each other’s bodies. On the other hand, to an audience, it reveals a sense of care, as observed by Jori Finkel in the New York Times, “It seemed an example of, or metaphor for, a kind, supportive community” (Finkel 2023). This work was first performed in 1961, and it has since lived both in the art world—performed in art galleries and museums for an audience—and in the dance world, where it developed in the studio space and was taught at dance workshops as a physical experience. According to Forti, whoever learns it is free to teach it and do it in an informal context. Clark’s Rede de Elásticos (Elastic net) was a proposition for a group of participants to, together, make a net by attaching elastic bands to each other. The group of participants was then invited to play with the net they made. This process of play, pushing, and pulling of the net also consisted of the intertwined bodies of the participants connected to form, what Clark called a Corpo Colectivo (Collective Body). This proposition and others were carried out in seminars led by Clark. The aim of the propositions was not to be artworks or performances but, in Clark’s own words, “a living culture (…) a living form of production” (Clark, L. quoted in Lepecki 2014, p. 281) where materials, such as elastic bands, have a relational function by acting as connectors in a “rhizomatic corporeality” (p. 281).

Both Huddle and Rede de elásticos are examples that catalysed our practice of the collective body in how both works—paradoxically artworks and living structures at the same time—set out conditions for assembling bodies to touch, support, move, and intertwine with other bodies and materials. In doing so, both works enact playful and immanent processes where bodies are, at once, making and being made in the collective activation of the field. As mentioned previously, this is a field that is affective and emergent in the collective formation, as a body itself.

3. Arrival

My sense of embarrassment was keen. Having been absent, without trace, for a considerable amount of the course of the group relationship, I felt awkward turning-up, unannounced although invited. I was distracted, tired, and anxious. My breathing was fast, my heart pulsating, my body heavy, my mind wandering, I was struggling to arrive in my body, in the space, in the collective body which at that point felt dis-membered. Bodies hiding the nervousness of being in-between wanting and not wanting to be there; some also distracted, tired, anxious. Some with pains and aches.

This section, Arrival, describes an account of our first meeting, where we imagined what this collaborative body looks and feels like and what it means to arrive at this body. Here, we situate the reader into how this question came to be. Drawing on Spinozan thought, Deleuze (1988) suggests this is a process where all matter has the “capacity for affecting and to be affected” (ibid. p. 123) both positively and negatively.

The precondition for the collective is the individuals’ intent to collaborate. What is brought forth is what the collective understands or desires. In the first session, we questioned the prompt of the current issue through conversation. We marked the moments of continuity through fluid notetaking on large, shared sheets of paper draped over tables, stuck on the wall, and placed on the floor. Pens, crayons, and pencils offered up an opportunity to make marks, respond to words, and make visual our conversations around the call out. The things we noted in this space highlight the future-orientated (Deleuze 1997) nature of collective contexts. Our lack of past continuities means our binding seeks what unfolds and what the unfolding can lead to. Through this mapping, we attuned to the spaces of resonance, which resembled intuitive acts of care: meditation, writing, and reading together. These moments were acts of testing methods for coming together by attuning to each other’s needs without having to state them. For example, there are possibilities that we may feel awkward or disconnected or that we might need time to ground ourselves into an encounter. The thread of connection is in the act of turning up, being open to unfolding, the act of pulling on the thread to question how far the line is. The sound of recognition creates progression. We are building ourselves through experimentation: our learning is not expanding but a redistributed constellation of a re-search/re-iterate/re-mind praxis (Ingold 2018).

This process of mapping our learning together emerges into a structure on which to hang this exploration: the desire to make this collective body move both in the physical sense and in our writing. In a way similar to Wyatt et al.’s (2010) decision to ‘felt’ their exploration in line with the flow of a play by structuring their paper through a series of acts (p. 730), here, we elicit an embodied connection through the movement of yoga. Employing the structure of the yoga class supports an attunement to the body: An arrival into our body, the movement of the body, and the time for reflection before entering into the world at large once more. This felt supportive of the needs of our body/ies. It felt based on care.

The/our need to arrive into the collaborative body is an important part of this praxis. It is an acknowledgment that various lives are coming together with intent, and within this assemblage, a multiplicity of feelings, emotions, needs, and desires are present. Arrival supports a moment of pause to re-orient, to merge the individual body, and to arrive in the collective body. The following reflections explore this arrival into the collective body and how it may flow and move.

I might write about the excruciating feelings around the first moments of engagement with these others, at the top of the stairs, vaguely styling-out my awkwardness but aware that the desire to run away was strong. If I’d told myself this would be reasonably anonymous, that I might be an audience member of another’s performance, I now recognised that this event was actually emergent, and that I would need to bring myself into it.

The arriving in the space was fractionated, scattered. I feared that I was giving myself away, that in my lack of contribution I was showing myself to be the imposter that I saw myself as in this situation; anxiety which my silence compounded. We eventually made our way downstairs, into a space called the Well Gallery. A water well, a hole in the ground excavated or dug up in order to access groundwater in underground layers of permeable rock, rock fractures, or unconsolidated materials such as gravel, sand or silt. The space didn’t tell us how we were supposed to sit or behave, it was left free for interpretation.

Some shy. The awkwardness and self-awareness of six bodies, some of us sitting on a soft blanket on the hard floor, in a space where people do not usually sit on the floor. Some sitting on a bench to be kind to a bad knee. What should we do? How do we start moving as a body? We sat in a circle, quietly, with eyes closed for three minutes. These three minutes gave me a chance to converse with the parts of myself that contained the stiffness of insecurity and to trust myself in order to trust others, because a small leap was needed for a successful collective creation.

We briefly discussed what we should focus our meeting on, and quickly a big roll of paper was laid out, cut, and taped on the floor at the centre of our circle. It formed the ground for our encounter. We started writing on it, for a few minutes, beginning to reflect on our bodies, our ways of being individuals in a collective context, in a collective body. We found ourselves reflecting on how this body should feel like, how this collective body should move.

I remember having the desire to feel this sense of fluidity…A body where my body was a-part of, not the whole, not the centre.

the circle thatwe formed onthe soft blanketon the floorbrought softness into the space and the group

tension and releasenoticing the sounds and finding a sense of calm spaceforgetting as a way of re-membering

Processes of arrival are attuned to affective disposition and are webbed into the embodied environment. The environment, in this instance, is accessed as part of the individual in processes of orientation (Ahmed 2006), where bodies take on the shapes of space as a way of understanding where they stand. The context of the location becomes integral to the processes through which the individual attunes to their being-in-space. It is also the first instance through which collaboration takes place: The negotiations of not just where the collective will convene but the qualities of an environment emerge as “enabling constraints” that foreground the interactions (Manning and Massumi 2014). The materiality of mark-making tools acts as neutralising forces and can be understood in a similar way. It is through these material environments/objects that we are able to ground in a mutual place from which play can arise.

4. Doing

The session in the Well Gallery (London College of Communications, UAL) shifted our contemplation of what this collective ‘body’ is and how it feels, moves, and supports the emergence of collaboration. The overarching intention of the session was to explore potential: How could this body flow? We re-joined together with a re-calibration of new bodies and continuities; however, the focus was re-oriented around the agency of materials. It was this that activated the collective body and made visual the ‘magic’ experienced through collaborative practice.

Henry Thoreau writes in his journal “Be not preoccupied with looking. Go not to the object; let it come to you.” A ball of cotton twine on a small table by the wall wants to join us. I sense it, it came to me and I am holding it in my hand. What if…. I hold onto one end of the string and pass the ball to the person on my left, who wraps it around their waist and passes it onto another person who wraps it around their fingers and wrists and they pass it onto somebody else who … we continue stringing ourselves into a body. How long is a piece of string? Where does this body begin and where does it end?

I recall the moment in which the string appeared. This wasn’t to be a nice, safe, solo reflective writing exercise in which we ‘arrived’, but would entail some interactive play, with others who I didn’t know. I felt a degree of trust in them all since they, like me, had come into this space, and I understand the potential in these engagements… yet that doesn’t remove the anxiety of engagement. Arriving here, together, encouraged an attunement to the space; but the crucial activity of becoming a collective body in the space started in the moment that the string appeared and I realised that I could not escape, now. It meant that I was going to actively become part of something. Moreover, this was to be emergent, since no-one really had any particular plan. There was a ball of string; string would be passed from person to person. And then …

… something happened. We stood in a semblance of a circle, around the paper sheet upon which we had been writing reflections, in our separate corners. Initially we stood politely on the periphery of the paper, but the string-passing necessitated us moving onto it, so shoes got kicked off. Now minus those pairs of outside grounding devices, thus more physically present in this unknown, creative space, we started to move differently. Someone talked about a cat’s cradle as the web of interconnection started to formulate, and these intersecting patterns seemed to invite the interjection of my socked foot. I realised I was wearing Halloween socks festooned with bats and gnarly trees and a haunted house, and suddenly now also minus the embarrassment that I might usually have felt in such realisation, I wanted my own body to echo the shape of the drawn trees, finding my fingers assuming the shape of crooked bony branches, becoming enveloped in the string web. There was little speech, since we were relying on visual cues to understand what we might do next, individually within the collective. When I stood on one leg and raised foot, the web bent towards it.

But when I still couldn’t reach it, I was more embarrassed that I expressed this verbally than by my flexibility failure, since speaking was almost like breaking the spell. As the embarrassment passed, my mind and soul and body also relaxed and I became more fluid. Our physical embarrassment seemed also to have passed, for as we became more interconnected and entwined, we realised that we were not only touching each other, but that we could also feel one another through the lines of string. The web had been formed, so now we were interacting with the web and thereby one another, moving within it; with it morphing around us. Now we could begin to explore the properties of the web, connecting us as a body: would it support us if we leant back into it? Could we make it move in a different direction?

These insights prompted a pondering of the Spinoza’s ([1677] 1996) question of ‘what can a body do’. As one of our bodies moved and entangled with the string, all others were affected. The movement was playful but also had the potential to cause pain. This distinctively exemplifies the ways in which all matter has the ‘capacity for affecting and to be affected’ (Deleuze 1988, p. 123), positively and negatively. The ebb and flow of movement within the string were bound by the tender–tension of the string wrapped around each body. Sudden movement pulling on the string had the potential to squeeze, trip, and tighten, and in the movements toward such feeling, the collective awareness enacted an easing off, releasing tension and morphing into a softer body. This materially-entangled process became such a merging, a Baradian (Barad 2003) ‘intra-action’. Barad’s (2003) argument draws attention to how we cannot operate separately from the world, rather that we morph and change ‘with’ and ‘through’ both human and non-human objects, just as they morph and change with and through us. Barad (2003) says that ‘Phenomena do not merely mark the epistemological inseparability of “observer” and “observed”; rather, phenomena are the ontological inseparability of agentially intra-acting “components”’(p. 815).

They go on to explain that this idea of everything, both being and becoming, as phenomena offers interesting insights into the making process, both textually and materially.

“Phenomena are not the mere result of laboratory exercises engineered by human subjects. Nor can the apparatuses that produce phenomena be understood as observational devices or mere laboratory instruments … Apparatuses are not inscription devices, scientific instruments set in place before the action starts… Importantly, apparatuses are themselves phenomena” (Barad 2003, p. 816).

Barad (2003) argues further that “apparatuses are constituted through practices that are perpetually open to rearrangements, rearticulations, and other reworkings” (p. 817). When we intra-act with the various matter of making, we materialise through the intra-actions, and alternative possibilities can present themselves. One such materialisation that occurred in our exercising of the collective body was a moment when all our weights shifted, and the string became a self-supporting structure for the group. The string became a cradle. Donna Haraway (1994) discusses the game of ‘cat’s cradle’ in which string entwined between the fingers is passed between players. As Haraway (1994) states, “Cat’s cradle invites a sense of collective work, of one person not being able to make all the patterns alone. One does not “win” at cat’s cradle; the goal is more interesting and more open-ended than that” (p. 69).

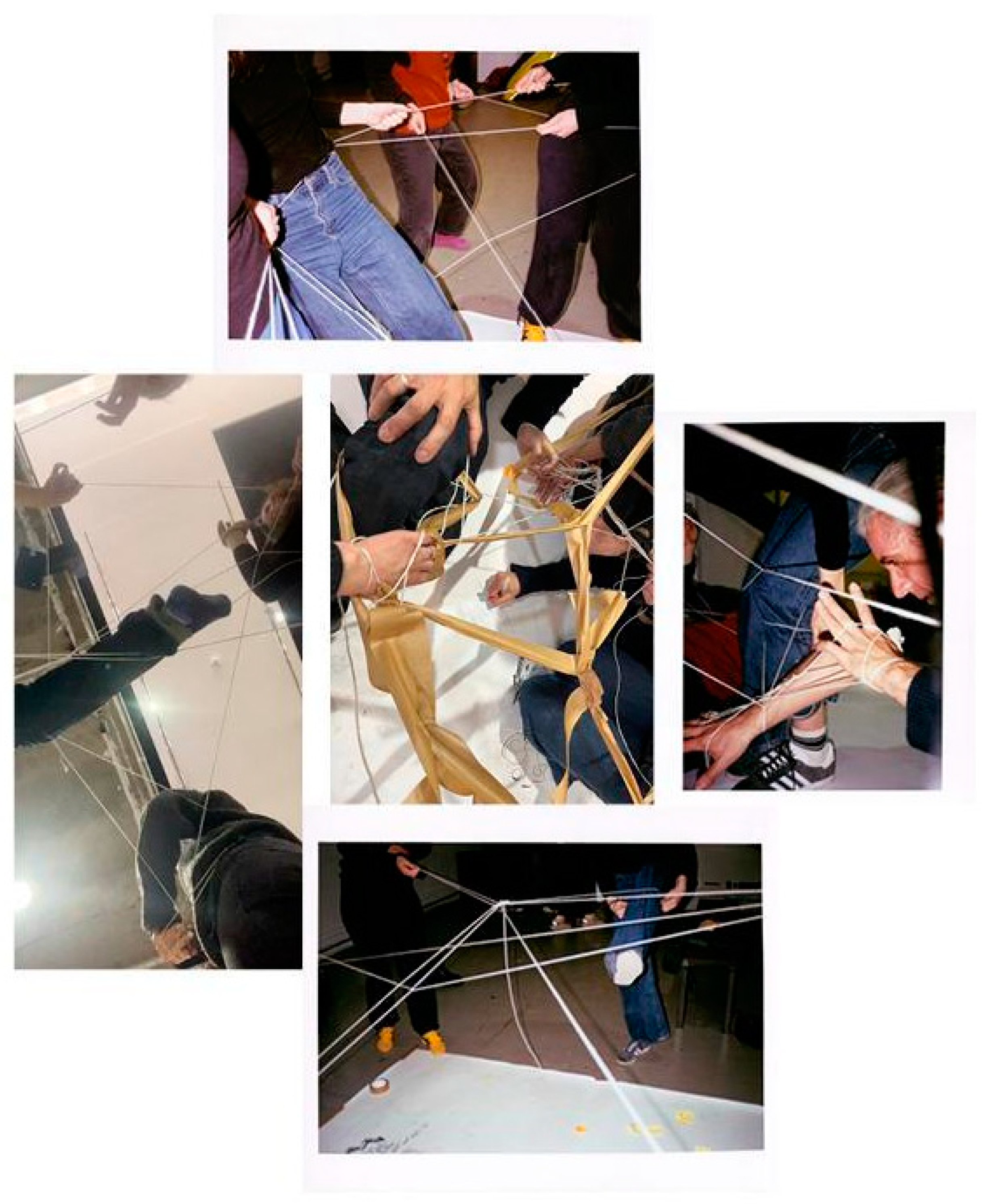

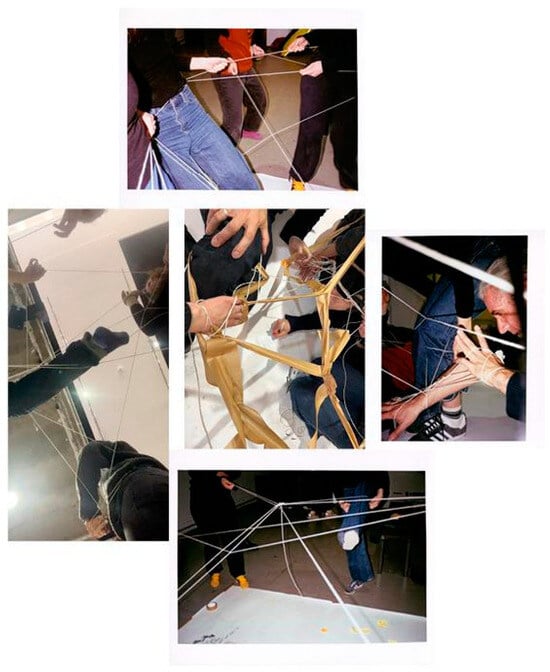

As in Lygia Clark’s Estruturas Vivas propositions, where the materials (elastic bands) have a relational function, here, the string enabled us to access the dynamic of the collective body. It was more than a metaphor for something that already existed; it also became a tool to access the entangled ways of being in relation together. Other tools that would/do facilitate our working together, such as writing, discussions, or presentations, for example, bring with them a different weight of institutional framing. The string, in this instance, binds us as an entity and cuts through the hegemonic conditions of more traditional academic practices (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stringing-(em)bodying.

The string, therefore, acts as an instigator; rather than passing the binding between individuals, we used the string as a way of questioning what it is to be within and bound in that connection. Taken in the literal sense of the cat’s cradle, we are questioning what it is like to be the ‘fingers’ (or the constituent components of the entanglement) that hold the material assemblage together and, in turn, what that facilitates and makes evident within the dynamic of collective interaction. It was this ‘sense of collective work’ that triggered this connection, the innate understanding that this practice would be impossible alone. If we had engaged in the same movement activity without the string, the connection between individual physical boundaries would not have been so palpable, made so literally felt by the way the string reconfigured the field of proximity. In doing so, an intensity was introduced that directed our bodies to move closer to, under, and over with each other. In our moving together with the string, we created a ‘space of the body’, expressed by philosopher José Gil and Lepecki (2006) as being “(…) the skin extending itself into space; it is skin becoming space—thus, the extreme proximity between things and the body” (p. 22). Gil says this means that the body extends itself into space and, therefore forms a new ‘virtual’ body yet also ready to allow gestures to become actual. The space of the body “is the moment there is an affective investment by the body” (ibid.). Gil further explains that “In a general manner, any tool and its precise manipulation presupposes the space of the body” (ibid.). Through Gil’s concept, the large sheet of paper, the pens, Post-It notes, and string that we used are tools that entail the ‘space of the body’, both individually and as a collective. Of course, we could have made connections through the movement of our bodies alone, but that would have required a preformed confidence within ourselves to play in this way. The string enabled a confidence that shifted the focus from the human body to the space around and in-between, and when the human is decentred, then other possibilities arise.

The ebb comes from over-thought. The flow comes from a non-attached suggestion. The enaction of the body uses thread to test the embodied language of the collective. Binding the bodies in a space engages with negotiations of touch, care, play, and fluidity. The alignment with unfolding together remains the same but without reference. This collective body has a response-ability that probes and diffuses the individual connection. Boundaries are stretched but coordinated. Our reflections are bound in string and tape. The evolution is not a trajectory but a continuation within constellation-like structure.

I take off my shoes, pink socks.

I need to feel the floor

hands fingers pull let go pull again rub and twist pass through arm stretched string stretched foot lift thread above underneath bend knees tight fall on the floor bone hold lie on the floor disarming smile touch alive sense breathe pulsate rhythm connect absorb release flow sweat

are we a muscleare we an organare we boneare we fleshare we skin

A web of string around our bodies makes our connection palpable. Jane Bennett tells us about the ‘force of things’ (2010) as an alternative to the idea that objects are stable entities, proposing instead that objects are independent and alive. Bennet calls this a ‘Thing-Power’, the “ability of inanimate things to animate, to act, to produce effects dramatic and subtle” (ibid. 2010, p. 6). We affect, and we are affected.

The string becoming a body, we are becoming string, string and us becoming a body and the floor and the paper and sounds and… The string embodies our body. How do we know how to move? String and fingers know as thinking is initiated in the experience. We respond to what is happening as it is happening. The boundaries of our own physical bodies broken, we touch and are touched, we sound without speaking, we care and trust. The centre shifts.

It is a performance of relations, speed, and slowness (Deleuze and Guattari 2013). Ascending and descending, an eventful crack in the well, flowing us into fluidity. Zigzags are made of round shapes. Softening us into ‘a widening field’ into a journey in our body and imagination (Tufnell and Crickmay 2008). We stayed.

RememberingStringingBodying

That’s when we started connecting ourselves with strings. And communicate without words but with movement. And to communicate like that you need to listen in a different way. Eyes are useful for this listening, not ears. Reading others’ intentions and needs and supports in their movements. And in yours. Are you participating to the movement/conversation? Where is this body/conversation going? How are you supporting or changing, or affecting that? What are your needs and how do you express them?

Pulling stringsUntie knotsComplicate thingsMake a messTidy it upMove far from everyoneBe aloneObserveThen closeFeel everyone closeHelp herThat string might be hurting her skinSupport themBack to backHand to handFeet to feetHow does the floor feel like?Can you let go?Can you listen?

Although I still found the concept of flowing too unfamiliar and large to flow into, the thread used as a giant cat’s cradle felt like a hand was extended toward me that accompanied my participation. This comfort fully materialised once everyone had entwined themselves by the thread, and the movement that oscillated between timid and expansive started to settle into a dialogue with itself. Awareness of myself became awareness of the tensions around my body and their relationship with the movement of others and the tensions created by motion. Not much was being said, and the parameters of conduct and duration of the exercise had not been stated or were forgotten, but it created a kind alertness, a hesitation, as well as a desire to test, and each test was responsive and encouraging to a response from others in the group.

At times, laughter and giggles erupted, confirming that the constant wrapping and unwrapping, even though at times painful and uncertain, created a productive state of play that was to be encouraged. Many thoughts emerged during that state, and with them came the awareness that I was trying to retain all the impressions gathered at the time, but I was unsure if my memory could hold onto them. It was later described as a future-orientedness of the moment, which, upon reflecting, I would describe as trust in the potential of the encounter. The testing of limits or the support for others in doing so was sustained, and the responsibility that weaved that support felt generative instead of limiting. The open-endedness of this moment was allowed by the commitment to the labour/movement that was occurring; that commitment was enabled by the responsibility of each person over the other, which the malleable tension of the thread expressed at any given time. When I got stuck, becoming wrapped by my own movement, it was continuing the movement that produced the freeing. Each interruption became, in relation, a moment in the collective movement that we created.

5. Discussion

After this entanglement, we paused to ponder what had occurred, acknowledging how the ‘vibrancy’ (Bennet 2010) of the encounter enabled something more than the outcome of the event itself. Exploring the effects that play out in events (Deleuze 2017) notes that “all bodies are causes–causes in relation to each other and for each other” (p. 5). Having come into the space as individuals, within our separate bodies, there was a palpable sense that these bodily boundaries had become entangled, becoming blurred. Having not really known each other at the start, there was a clear sense of ease. The stiffness discussed in the reflections above when entering into academic spaces had softened. We had sunk into the soft tissue of the collective body, and we were playfully stretching our limbs.

What was pivotal in this transformation was the string. The matter and materiality of the string activated something other. The agency of the string ultimately required us to enter into a more-than-human collaboration. It became a Baradian (Barad 2003) intra-action between bodies, the string, and movement. It required a willingness and a desire to support and nurture but also, importantly, to care. Whitehead (1958) beautifully articulates, “Have a care, here is something that matters!” and in this instance, it emerges both in terms of our movements’ impact on other bodies that are entangled with the string and on the collaborative body as a whole. This acknowledgment of care is important, activated through the string that bound us, thoughts of tension and restriction blurring with a potential for pain. The body can feel pain, and it can be cared for through the touch of string and fingers, feet, and limbs, all emerging and entangling with and through each other. The string became agential, paradoxically, as an enabler and pain giver. The discomfort provided moments of pause to resist and realign the body in collaboration with the string. This shift in movement demonstrated a way of finding ways through the complex web of this practice-research assemblage.

It reminded me of the art work ‘Chasing Deleuze’ by Duchamp. A room tangled with string, and the body trying to make pathways through. The image can be viewed both as playful but also restrictive.

This led me to consider the disabled body in this entanglement. In this session I could not crouch down because of an injury I had recently sustained to my knee. Admittedly this isn’t a disability of note, but this small insight made me envious of the person who could entangle with the string whilst lying on the floor or creating strange body shapes with bent legs. However, as I became wrapped by the string I also felt held. I was included in the structure, my movements equally weighed on the person on the floor as theirs did on mine. The string created a sense of safety, I fear without the string my engagement would have felt more isolated.

The remnants of our intra-actions with the string now lay tangled on the floor, signifying the trace of our movements and of our collaborative experience. The pile of knotted string was imbued with the ‘magic’ (Bennet 2010) that had occurred, and that made us feel part of this collaborative body. To return to the Spinozan question of “What can a body do?”, this exercise highlighted the potential of connection that can occur when the focus is moved away from the human body and drawn into a between-space. It is when the focus becomes materially driven that other posthuman possibilities open up. Hickey-Moody and Page (2016) discuss how this process is not simply with/in bodies but also always with/in matter. Therefore, it is not simply a human endeavour “to make matter and meaning, it also makes us; we are entangled, co-implicated in the generation and formation of knowing and being” (p. 94).

The string not only supported these intra-actions in the physical sense but lives on in a more ephemeral entanglement. Although the string no longer holds the collective body, it activates a sense of collaboration that still draws connections across our individual bodies—an invisible trace of the string connecting us long after the event of the day, but also symbolic of all the encounters experienced by the group. The string is not, therefore, simply left on the floor; it has become part of the collective body. Matter, in this sense, is therefore not a passive lump that simply reacts to modes of human thought but materialises through embodied intra-actions, affecting as well as being affected. Stephanie Springgay et al. (2005) claim this process happens in the ‘between’, in the ‘unknowing’. She states that “too often works of art are considered to be the traces left from the processes of meaning production, rendering art as a static object. Yet, the visual as a bodied process of knowing and communicating focuses our attention and emphasises the in-between and the un/expected spaces of meaning making, where art becomes an active encounter” (p. 42).

In this session, the collective body was activated in ‘un/expected’ ways, emphasising that the collaborative body holds the potential to make connections and meaning beyond our individual bodies. What became interesting to consider in this space was how our individual aims as practice researchers could be replenished by these intra-actions. As we stretch our individual bodies to merge and collaborate with others, both human and non-human, we are offered alternative ways of thinking and being that both excite new practices but also support a refocusing back into our own research. The collaborative body provides what Haraway (1994) describes as a desire for a ‘knotted analytical practice’, where “[t]he tangles are necessary to effective critical practice” (p. 69). As our attention is shifted beyond our primary concerns and we collaborate on shared projects, we become replenished, and we leave rejuvenated.

This desire for encounter, for knotted, analytical, and critical practice, is related to pleasure. Like in yoga and movement practices, listening to our own bodies (our own and in relation to others—humans, strings, paper, floor, etc.) is initiated by the search for pleasure. We draw from adrienne maree brown’s idea of pleasure activism as “the work that we do to reclaim our whole, happy, and satisfiable selves from the impacts, delusions and limitations of oppression and/or supremacy” (brown 2019), which we see linked to the Braidottian idea of affirmative ethics—the pleasurable yes! The core questions that shape brown’s work are closely linked to our own questions around the collective body: “How do we learn to harness the power and wisdom of pleasure, rather than trying to erase the body, the erotic, the connective tissue from society? How would we organize and move our communities if we shifted to focus on what we long for and love rather than what we are negatively reacting to?” (brown 2019)

I feel the need to have developed a relationship with them wherein a degree of vulnerability has been achieved through body language, emotional expression, and hopefully, humour. Until that point, written words are a crack by which self-consciousness creeps in, enveloping everything in me in silence.

To become a part of

Actually, we remained in the same spot from which we had started, although now restrained, considered politeness had morphed into a rather different unspoken understanding. The edges of the paper that we moved around had curled and ripped, our reflections smudged and blurred by the shuffling of feet and other movements of our body-bodies. For in that entwining interaction we had become a body, with an internal logic, albeit temporal and guided by our physicality. At some point someone introduced a roll of tape, which we wrapped around us, its tacky crackling introducing another, slightly unpleasant sensual aspect into the event. When the tape was torn, that event which our making had become was completed, and we broke the spell and rested on the floor, standing or crouching or sprawling on the paper mat, still physically connected, still restrained, by string and tape. We talked about what had just occurred, which had been revelatory, suggestive, engaging. Talking about what we had experienced superseded my own sense of what I had felt, before and after; but now I spoke–for now I had words I had not done prior to coming together in this way. We talked about the supportiveness and the mutuality, the common consensuses that counterbalanced the individual requirements or desires or sense of selves. We talked about our physical proximities and trusting. I did not mention my own emotional shift; but knew that I would share it.

Afterwards, I was able to speak, therefore be with others in multiple expressions of myself. That encounter had increased my ability to act in that context.

6. Between Body–Writing Practice

The flow of this paper is embedded in the flow of our collaboration. This multi-modal activation situated our research between methods of collective practice. Our practice recognises the embodiedness of the very sharing of space as our starting point for being collective. From this positioning, the assemblage of relation is already there to play within. Through stringing-bodying practice, we are in mutual enactment of being within this space as an investigation of potentialities; we enact collective assemblages like Clark’s Rede de elasticos (Clark 1973) and Forti’s Huddle (Forti 1961). This site, as our preface, has an immediacy to our connection—both intended and as a force for further methods.

We then extend this mode of collective practice in spaces of writing, with the body knowledge extending beyond the initial practice and into shared memory encounters. Sharing methodological space with Wyatt et al. (2010), Löytönen et al. (2014), and Gale et al. (2013), our writing becomes a threading of “the multiple, the interconnected and the indistinct” spaces we shared/continue to share (Gale et al. 2013) by including individual reflections, collective readings and responses, collaborative analyses and interventions. We called upon our shared theoretical knowledge and exchanged critical considerations to develop the form and tone of this article. These processes, alongside returning to this text for edits and revisions, further enable our stringing-embodying connection to repeat due to shared intentions and experience. As Lygia Clark notes, in relation to her propositions (i.e., Rede de elásticos Clark 1973), one of the characteristics of the collective body is “that it cannot take place just once (…). The meaning given to it is that there is a socialising in time and a joint elaboration in which each individual changes, expressing himself, connecting affectively or not to each element in the group, creating an exchange of impressions which goes beyond the propositions and affects the life of each member” (Clark 1998, p. 306). Through a series of entangled mediums, we explored this ‘socialising in time’ and ‘joint elaboration’ that occurred in the spaces where we assembled, how the conjoining of our bodies, both human and non-human, activated something more-than, a collective body.

There are a couple of distinctions that we would like to reflect on in terms of how we are situated within the writing practice examples; firstly, and as already stated in so many words, the body is primary in prompting this writing output. We are, therefore, situated in-between as a body–writing method. Secondly, our first-hand account of practice is a blended voice; unlike the aforementioned writing-as-collective examples, we want to situate the reader from the position of our collective rather than the constitutive parts of individuals webbing the collective. This marks an important development in the capabilities of this collective body, and it further brings the body closer to this written form.

It is because of these writers, thinkers, and doers that, as doctoral students, we are able to envision what it is to be a body together. In another striking metaphorical resemblance, one of our collective members has recently become a parent, and in describing the baby’s body moving limbs to work out where and how to stretch into their environment, so too are we stretching our collective body and working out the space and boundaries of these methods in an academic environment. We are pulling on these established experimental models because we are impressionable; through these rigorous, critical, art-full, poetic, playful research practices, the voice of our research body is developing. While in Wyatt et al. (2010) and Löytönen et al. (2014) the researchers identify themselves and interact with each other (and Deleuze!) as actors, characters, and performers, we are in the process of understanding what it means for us to ‘speak’ this collective body, to present it, to perform with it; knowing, however, that at the core of our practice, there is the intention to preserve our collective identity, our blended voice.

When collaborative practice excites something that moves beyond ‘us’ as individuals, and then merges into a space between, then there is the potential for creative activism that re-orients past, present, and future. These encounters were born from the desire to layer other ways of being, thinking, and learning onto the academic spaces we work and study in as a way to both work with and push against these institutions. Furthermore, we wanted to rehearse strategies to resist the postcolonial and patriarchal oppressive structures that we move within and impact upon our daily lives, which we brought with us into the meetings as burdens and weights that severed us or felt like a severance from each other. But along with the encumbrances, we likewise brought our collective hope. Gale et al. (2013) speak to similar modes of writing together as a resistance to developing as professionals; like these artist-researchers, we are resisting the isolated confinements of professional practice in the institution. In writing together, we are enacting the physical methods into an extended body of thought. Through a praxis of probing–diffusal, these boundaries are coordinated, and the weights and borders become blurred during the exercise. The affective field this praxis generates is a body-space opened up for elseness. The benefit is a stretching of the Cartesian dismembered limbs to re-member within a shared space, a common body.

This act of re-membering our dismembered bodies is an act of nomadism, a Braidottian (Braidotti 1994) encounter that desires a space from within which to resist, always anchored to the histories from which we emerged, positioned on axes of differentiation such as class, race, ethnicity, gender, age, and others that intersect and interact with each other in the constitution of subjectivity. The notion of nomad refers to the simultaneous occurrence of many of these at once (p. 4).

Using this notion of ‘simultaneous occurrence’, a nomadic becoming provides a tonic for the colonial and patriarchal structures that have come to form our contemporary understanding of the world, slicing up continents and binding communities, dismembering bodies (Ingold 2007).

Attuning to the matter and material agency of the string in the second encounter, we witnessed a Baradian (Barad 2003) ‘cut’, a slicing through the discomfort felt by members of the group when first coming together. The string enabled an embodied conversation to occur; it shifted the Cartesian desire to speak a minded response and enabled a space where embodied intra-actions could occur. This intra-action facilitated a rupturing of the individual body, the isolated body, and connected all bodies within this encounter in a moment where the agency of matter could work through and support new becomings (Deleuze and Guattari 2013). It does not matter that we did not know each other; the academic pressure to verbally introduce and state (or defend) knowledge was removed. The pressure on speech of formal academic language, which disembodied our experience of relatedness, dissolved and became embodied sounds, giggles, or stuttered questions and answers, which then trickled and flowed into the discussion of new meanings. The string cut through the weight of a perceived academic expectation, reshaping it and reminding us of our bodily states being in relation to existing power structures and rituals.

7. Conclusions

As a form of playful dissent, the flowing and becoming we remember in the reflective space of this paper has the potential to act as new foundational narratives that affect the past we carried into the encounter. According to Braidotti (2014), “Remembering in the nomadic mode is the active reinvention of a self that is joyfully discontinuous, as opposed to being mournfully consistent, as programmed by phallocentric culture. It destabilises the sanctity of the past and the authority of experience. The tense that best expresses the power of the imagination is the future perfect: ‘I will have been free.’” Quoting Virginia Woolf, Deleuze also says: “This will be childhood, but it must not be my childhood” (ibid., p. 173).

Such embodied, remembered, and writing encounters both enable connections with others and inspire a refocusing on our individual practices. We see this work as part of a continued investigation of the potentialities/boundaries of our collective dynamic. In its current form, this paper makes a case for a critical engagement in collective practice but, importantly, marks only one point of this research trajectory. This presents certain limitations for this article; namely, though we intend to build upon the critical pedagogical and political implications of our collective research, we are unable to fully establish here what those might be. This marks an interesting limitation in the nature of collective work; though we recognise the significance of our work together, working together also takes time, which means our outputs are considered ongoing discoveries rather than reflective accounts. Though this is an important limitation to recognise, practice-based research creates space for the becoming, unfolding nature of knowledge, so we believe that for now, the work presented in this article evidences a critical account of where we are together and how we meet.

We see Seeders as a necessary resistance to our otherwise isolated research journeys and, with that, a resistance also to neoliberal frameworks that herald the individual over communal thought. The string, as a facilitator activator of the mutual trust in this site, grounds our study in posthumanist material frameworks as enabling for future-orientated practices. This research is ongoing and in flux as the group continues to meet, converse, write, and explore the parameters of the collective formation as body. What can this body do, and where and how can it occupy the space as it evolves? This presents a challenge for future research, for when the body shifts, the methods we employ (collective writing, workshops, and so on) will need to shift as well. Points of resolution (such as writing this paper) are helpful in providing space to re-evaluate and consolidate where the collective body is and how it arrived there (here). The collective body is also a discursive body: as we continue to meet together there is a checking back and forth between us; this awareness developed into a largely non-vocalised consent. This article can be seen as an offering for other collectives looking to acknowledge/apply their encounters in an effective way. What is vital within these collaborative practices is the potential for the collective encounter to spill out and leak into our individual practice. It agitates and creates ‘a margin of manoeuvrability’ (Massumi 2015). Coming together in this way is rejuvenating, providing a means through which individuals in bodies can replenish before venturing once more into the neoliberal spaces in which we intra-act.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.R., B.M., M.P., and C.S.; methodology, M.L.L., A.V.R., S.O., M.P., J.M., and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.L., A.V.R., S.O., M.P., J.M., B.M., and C.S.; writing—review and editing, A.V.R., S.O., and M.P.; visualization, M.L.L.; project administration, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge both Goldsmiths College and London College of Communications for the use of their spaces. We would also like to thank the editor and reviewers of this article, whose insightful comments and suggestions greatly improved the criticality of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Dennis. 2018. Art, Disobedience, and Ethics: The Adventure of Pedagogy, 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, Karen. 2003. Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Journal of Women and Culture in Society 28: 801–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 1994. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory: 2. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2014. Writing as a Nomadic Subject. Comparative Critical Studies 11: 163–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2019. A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities. Theory, Culture & Society 36: 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2022. Posthuman Feminism. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Breitwieser, Sabine, Simone Forti, and Museum der Moderne Salzburg, eds. 2014. Simone Forti—Thinking with the Body. München: Hirmer. [Google Scholar]

- brown, adrienne maree. 2019. Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good. Emergent Strategy Series; Chico: AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Lygia. 1973. Rede de elásticos. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Lygia. 1998. Lygia Clark: Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, 21 octobre-21 décembre 1997; MAC, galeries contemporaines des Musées de Marseille, 16 janvier-12 avril 1998; Fundação de Serralves, Porto, 30 avril-28 juin 1998; Société des Expositions du Palais des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles, 24 juillet-27 septembre 1998; Paço Imperial, Rio de Janeiro, 8 décembre 1998-28 février 1999. Barcelona: Fundació Antoni Tàpies. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1988. Spinoza: Practical Philosophy. San Francisco: City Lights Books. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1997. Essays Critical and Clinical. Translated by Daniel Smith, and Michael Greco. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 2017. Logic of Sense. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 2013. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, J. 2023. Simone Forti’s Experiments Transcribing Bodies in Motion. New York Times. February 8. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/08/arts/dance/simone-forti-moca-golden-lion.html (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Forti, Simone. 1961. Huddle. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, Ken, Becky Turner, and Liz McKenzie. 2013. Action research, becoming and the assemblage: A Deleuzian reconeptualisation of professional practice. Educational Action Research 21: 549–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, José, and André Lepecki. 2006. ‘Paradoxical Body’. The Drama Review 50: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14: 575–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, Donna. 1994. A game of cat’s cradle: Science studies, feminist theory, cultural studies. Configurations 2: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey-Moody, Anna, and Tara Page, eds. 2016. Arts, Pedagogy and Cultural Resistance: New Materialisms. London: Rowman & Littlefield International. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2018. Anthropology between Art and Science: An Essay on the Meaning or Research. FIELD (11). [Google Scholar]

- Lepecki, André. 2014. Affective geometry, immanent acts: Lygia Clark and performance. In Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948—1988. New York: Museum of Modern Art, pp. 278–293. [Google Scholar]

- Löytönen, Teija, Eeva Anttila, Hanna Guttom, and Anita Valkeemäki. 2014. Playing with Patterns: Fumbling Towards Collaborative and Embodied Writing. International Review of Qualitative Research 7: 236–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Erin, and Brian Massumi. 2014. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massumi, Brian. 2015. The Politics of Affect. Maldonado: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Puig de La Bellacasa, Maria. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spinoza. 1996. Ethics. Translated by Edwin Curley. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Books. First published in 1677. [Google Scholar]

- Springgay, Stephanie, Rita L. Irwin, and Sylvia Wilson Kind. 2005. A/r/Tography As Living Inquiry through Art and Text. Qualitative Inquiry 11: 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufnell, Miranda, and Chris Crickmay. 2008. A Widening Field: Journeys in Body and Imagination. London: Dance Books. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Alfred North. 1958. Modes of Thought. New York: Capricorn Books, G.P. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, Jonathan, Ken Gale, Susanne Gannon, and Bronwyn Davies. 2010. Deleuzian Thought and Collaborative Writing: A Play in Four Acts. Qualitative Inquiry 16: 730–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).