John Brown, Black History, and Black Childhood: Contextualizing Lorenz Graham’s John Brown Books

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. John Brown, Black History, and Black Children

John Brown, the liberator of Kansas, the projector and commander of the Harper’s Ferry expedition, saw in the most degraded slave a man and a brother, whose appeal for his God-ordained rights no one should disregard; in the toddling slave child, a captive whose release is as imperative, and whose prerogative is as weighty, as the most famous in the land.11

I will not have to shrive my soul a priest in Slavery’s payBut let some poor slave-mother whom I have striven to free,With her children, from the gallows-stair put up a prayer for me.18

3. Brown in Early African American Children’s Literature

I have never liked history because I always felt that it wasn’t much good. Just a lot of dates and things that some men did, men whom I didn’t know and nobody else whom I knew, knew anything about. Just something to take up one hour of the three hours left after school.But since I read the stories of Paul Cuffee, Blanche K. Bruce and Katy Ferguson, real colored people, whom I feel that I do know because they were brown people like me, I believe I do like history, and I think it is something more than dates.25

Now that’s just the kind of history I like. Won’t you ask THE BROWNIES’ BOOK to tell some more stories like that? I would like so much to know the story of John Brown. I have heard so many people talk about him and we used to sing a song about him, but nobody seems to know what he really did,—I don’t.27

4. Graham’s Twentieth-Century John Brown Moment

Some people still believe that members of their own race are inherently superior to members of other races. In America some white people want to keep black people in a separate and unequal status. Those who struggle for full equality in education and employment meet resistance not only in words but also in the form of violence. After reading about John Brown and the conditions in his day, we will better understand some of the problems with which we still have to deal.42

5. Reading Graham’s John Brown

It was in Springfield that Brown first became well acquainted with blacks. He met with them as individuals, and he hired some in his business. He visited in their homes and got to know them as families. He went to their churches, and he often sat quietly in their meetings while they talked about their problems and their hopes and their fears. With them he considered himself an equal. They sat at his table, and he sat at theirs.51

John BrownWho took his gun,Took twenty-one companions,White and black,Went to shoot your way to freedom…55

Blow ye the trumpet, blowSweet is Thy work, my God, my King.I’ll praise my Maker with my breath.O, happy is the man who hears.Why should we start and fear to dieWith songs and honors sounding loudAh, lovely appearance of death.57

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A connection worth noting is that W. E. B. Du Bois’ second wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, was Lorenz Graham’s sister. |

| 2 | See Fielder (2021), “Black Madness, White Violence, and John Brown’s Legacy,” Abolition’s Afterlives Forum, American Literary History 33.1: e40–50. Accessed 15 April 2022. https://academic.oup.com/alh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/alh/ajab006/6208115?searchresult=1#233672486. |

| 3 | See Quarles ([1972] 2001), Allies for Freedom: Blacks on John Brown, pp. 15–36. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Du Bois ([1909] 2001). David Roediger, p. xxv. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Quarles ([1972] 2001), p. 15. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

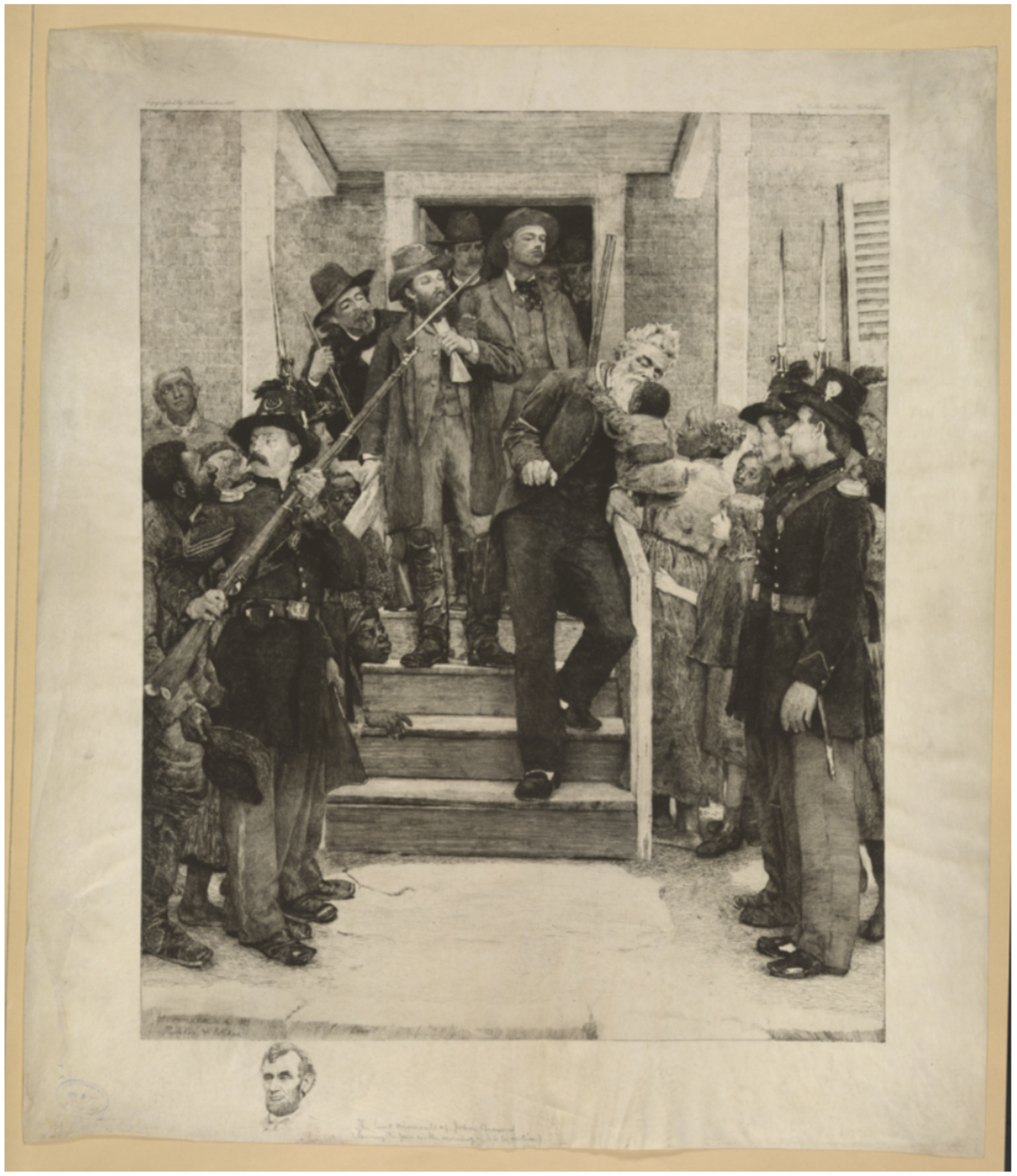

| 13 | On the mythology surrounding this moment, see Malin (1940), “The John Brown Legend in Pictures. Kissing the Negro Baby,” Kansas Historical Quarterlies 9.4, 339–341; and “The Legend of John Brown’s Last Kiss” Graphic Arts Collection, Special Collections, Firestone Library, Princeton University, 23 December 2020. Available online:. https://graphicarts.princeton.edu/2020/12/23/the-legend-of-john-browns-last-kiss/ (accessed on 1 April 2022). This incident was, however, contested as early as 1885. For example, one account insisted that no Black people were present at Brown’s execution, reporting that “The story that Brown kissed a negro baby at the foot of the gallows is an invention, for there were no colored people in the immediate vicinity of the place of execution.” See “Lee’s Capture of John Brown,” The Sun (9 August 1885), p. 5. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Edward H. House’s account of this story seems to be its original source. See “The Execution” New York Daily Tribune (5 December 1859): 8. The account that appears in the Anglo-African Magazine seems to be a pastiche of sorts rather than a verbatim reprinting, but the two paragraphs that tell this story are identical to those in the New York Daily Tribune. See “The Execution of John Brown,” The Anglo-African Magazine 1.12 (December 1859): 398. This was not the only reference to Brown in the Anglo-African Magazine. The above account of Brown’s execution appeared alongside an extended, serialized account of “The Outbreak in Virginia” and was followed the next month with an allegory of sorts suggesting that Brown’s violence would spark the revolutionary overturn of slavery, by Frances Ellen Watkins (Harper), and a poem by Joseph Murray Wells, “John Brown at Harper’s Ferry.” |

| 16 | The Execution of John Brown. |

| 17 | John Brown, letter to Mrs. George L. Stearns, Charlestown, Jefferson Co Va. 29 November 1859, in The Tribunal: Responses to John Brown and the Harper’s Ferry Raid, ed. Stauffer and Trodd (2012), p. 70. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | While age is not mentioned in Child’s preface, she is clear that the text is meant to be shared among families and communities—read aloud by those who can to those who cannot. Some poems included here, such as Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s poem “Thank God for Little Children” have been identified as early African American children’s literature. On this point, see Chandler (2017), “‘Ye Are Builders’: Child Readers in Frances Harper’s Vision of an Inclusive Black Poetry,” in Who Writes for Black Children? African American Children’s Literature before 1900, ed. Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane, pp. 41–57. |

| 21 | For a selection of leftist radical children’s literature, see, for example Mickenberg and Nel (2008), Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature. |

| 22 | For a selection of some of white-authored antebellum antislavery literature, see, for example, Deborah DeRosa (2003), Domestic Abolitionism and Juvenile Literature, 1830–1865. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | See Letter from Pocahontas Foster to W. E. B. Du Bois, 6 October 1919. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers. University of Massachusetts, Amherst. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b165-i137. |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | Although the Brownies Book generally featured Black authors, this piece’s author, Lillie Buffum Chace Wyman, was the niece of Rebecca Buffum Spring. (Wyman was the daughter of the white activist Elizabeth Buffum Chace; Chace’s younger sister was Rebecca Buffum Spring.) Spring published an essay on her encounter with Brown in prison, “A visit to John Brown in 1859.” See Virtuous Lives: Four Quaker Sisters Remember Family Life, Abolitionism, and Women’s Suffrage, ed. Salitan and Perera (1994), pp. 122–23. Another version of this account was published in the New York Tribune. See “A Visit to John Brown By A Lady,” New York Tribune, 2 December 1859, p. 6. |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | |

| 33 | |

| 34 | Dedication, The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer, n.p. |

| 35 | |

| 36 | The Graham’s collection of Bible stories told in West African traditions, How God Fix Jonah was first published in 1946. (A new edition was published in 2000.) Graham’s Town Series includes South Town (1958), North Town (1965), Whose Town (1969), and Return to South Town (1976). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | See Mickenberg (2005), Learning from the Left: Children’s Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States. |

| 39 | |

| 40 | |

| 41 | |

| 42 | |

| 43 | See Note 41. |

| 44 | |

| 45 | While African American children’s literature about Brown, more generally, deserves more attention, Graham’s books have been particularly neglected. For example, Tyler Hoffman prioritizes white-authored children’s books and omits Graham’s books entirely in “John Brown and Children’s Literature” in The Afterlife of John Brown, ed., Taylor and Herrington (2005), pp. 187–202. |

| 46 | On the significance of this last point see, for example, discussions of Ramin Ganeshram and illustrated by Vanessa Brantley-Newton’s 2016 picture book A Birthday Cake for George Washington, such as Thomas et al. (2016). Much Ado About A Fine Dessert: The Cultural Politics of Representing Slavery in Children’s Literature. Journal of Children’s Literature 42: 6–17. |

| 47 | |

| 48 | Lorenz Graham, John Brown (1980): A Cry for Freedom, p. 13. |

| 49 | |

| 50 | Graham, John Brown’s Raid (1972), p. 11. |

| 51 | |

| 52 | Thus de-exceptionalizing Brown, it is notable that Graham (like the majority of his Black biographical predecessors) resists characterizing Brown as insane in this biography, explicitly emphasizing accounts who upheld Brown’s sanity, See, for example, John Brown (1980): A Cry for Freedom, p. 153. |

| 53 | |

| 54 | Meyer (2019), “Five black men raided Harpers Ferry with John Brown. They’ve been forgotten.” The Washington Post. 13 October, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/10/13/five-black-men-raided-harpers-ferry-with-john-brown-theyve-been-forgotten/ accessed on 15 April 2022. Meyer is also the author of Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army (Meyer 2018). |

| 55 | Hughes (1992), “October 16: The Raid,” in The Panther & the Lash: Poems of Our Times. 28–29. It is notable also that Hughes was the grandson of Mary Sampson Paterson who (before her marriage to Charles Langston) was the wife of Lewis Sheridon Leary, one of Brown’s allies who was killed at Harper’s Ferry. |

| 56 | |

| 57 | |

| 58 | |

| 59 | See DeCaro (2016), “Lyman Eppes Jr.’s Christmas Memory of John Brown,” John Brown Today: A Biographer’s Blog, Sunday, 25 December 2016. https://abolitionist-john-brown.blogspot.com/2016/12/lyman-eppes-jrs-christmas-memory.html accessed 10 May 2022. |

| 60 | Jonda McNair, Letter to the Editor, Horn Book (November/December 2002), p. 131. |

| 61 | McNair, Letter to the Editor. |

References

- Anderson, Osborne Perry. 1861. A Voice from Harper’s Ferry; with Incidents Prior and Subsequent to Its Capture by Captain Brown and His Men. Boston: Printed for the Author, p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Capshaw, Katharine. 2014. Civil Rights Childhood: Picturing Liberation in African American Photobooks. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. xi. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, Karen. 2017. ‘Ye Are Builders’: Child Readers in Frances Harper’s Vision of an Inclusive Black Poetry. In Who Writes for Black Children? African American Children’s Literature before 1900. Edited by Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Child, Lydia Maria. 1869. John Brown and the Colored Child. In Freedmen’s Book. Boston: Fields, Osgood and Co., pp. 241–42. [Google Scholar]

- DeCaro, Louis A., Jr. 2016. Lyman Eppes Jr.’s Christmas Memory of John Brown. John Brown Today: A Biographer’s Blog, December 25. Available online: https://abolitionist-john-brown.blogspot.com/2016/12/lyman-eppes-jrs-christmas-memory.html (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- DeRosa, Deborah. 2003. Domestic Abolitionism and Juvenile Literature, 1830–1865. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass, Frederick. 1848. The North Star, February 11, 1.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 2001. John Brown. Edited by David Roediger. New York: The Modern Library, p. xxv. First published 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Fielder, Brigitte. 2021. Black Madness, White Violence, and John Brown’s Legacy. Abolition’s Afterlives Forum. American Literary History 33: e40–e50. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/alh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/alh/ajab006/6208115?searchresult=1#233672486 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Floyd, Silas Xavier. 1905. Floyd’s Flowers; Or, Duty and Beauty for Colored Children, Being One Hundred Short Stories Gleaned from the Storehouse of Human Knowledge and Experience. New York: AMS Press, p. 185. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Pocahontas. 1920. The Jury. Brownies’ Book 1: 140. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, David B. 1920. Memorial Day in the South. In The Dunbar Speaker and Entertainer. Edited by Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson. New York: J. L. Nichols & Co., p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Lorenz. 1972. John Brown’s Raid: A Picture History of the Attack on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. New York: Firebird Books, Scholastic Book Services, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Lorenz. 1980. John Brown: A Cry for Freedom. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Langston. 1992. October 16: The Raid. In The Panther & the Lash: Poems of Our Times. New York: Vintage, pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Irby, Charles C. 1985. MELUS Interview: Lorenz Bell Graham ‘Living with Literary History’. MELUS 12: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Kellie Carter. 2019. Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- King, Wilma. 2011. Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century American. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, p. xix. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Mary. 1929. John Brown Rests Amid the Mountains. New York Times, October 20, SM4. [Google Scholar]

- Malin, James C. 1940. The John Brown Legend in Pictures. Kissing the Negro Baby. Kansas Historical Quarterlies 9: 339–41. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Michelle. 2004. Brown Gold: Milestones of African American Picture Books, 1845–2002. New York: Routledge, pp. xi–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Eugene L. 2018. Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Eugene L. 2019. Five Black Men Raided Harpers Ferry with John Brown. They’ve Been Forgotten. The Washington Post. October 13. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/10/13/five-black-men-raided-harpers-ferry-with-john-brown-theyve-been-forgotten/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Mickenberg, Julia. 2005. Learning from the Left: Children’s Literature, the Cold War, and Radical Politics in the United States. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mickenberg, Julia L., and Philip Nel. 2008. Tales for Little Rebels: A Collection of Radical Children’s Literature. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Robert C. 2010. Reading, ‘Riting, and Reconstruction: The Education of Freedmen in the South, 1861–1870. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 176–79. [Google Scholar]

- Quarles, Benjamin. 2001. Allies for Freedom: Blacks on John Brown. Cambridge: Da Capo, pp. 15–36. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, David S. 2005. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Salitan, Lucille, and Eve Lewis Perera. 1994. Virtuous Lives: Four Quaker Sisters Remember Family Life, Abolitionism, and Women’s Suffrage. New York: Continuum, pp. 122–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, Manisha. 2016. The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 454. [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, John, and Zoe Trodd. 2012. The Tribunal: Responses to John Brown and the Harper’s Ferry Raid. Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Andrew, and Eldrid Herrington. 2005. John Brown and Children’s Literature. In The Afterlife of John Brown. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth, Debbie Reese, and Kathleen T. Horning. 2016. Much Ado about a Fine Dessert: The Cultural Politics of Representing Slavery in Children’s Literature. Journal of Children’s Literature 42: 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Whittier, John Greenleaf. 1959. Brown of Osawatomie. New York Independent, December 22. [Google Scholar]

- Womack, Autumn. 2020. Reprinting the Past/Re-Ordering Black Social Life. American Literary History 32: 755–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Nazera. 2016. Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth Century. Urbana, Chicago and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman, Lillie Buffum Chace. 1921. Girls Together. Part II. Brownies’ Book 2: 141. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fielder, B. John Brown, Black History, and Black Childhood: Contextualizing Lorenz Graham’s John Brown Books. Humanities 2022, 11, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050124

Fielder B. John Brown, Black History, and Black Childhood: Contextualizing Lorenz Graham’s John Brown Books. Humanities. 2022; 11(5):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050124

Chicago/Turabian StyleFielder, Brigitte. 2022. "John Brown, Black History, and Black Childhood: Contextualizing Lorenz Graham’s John Brown Books" Humanities 11, no. 5: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050124

APA StyleFielder, B. (2022). John Brown, Black History, and Black Childhood: Contextualizing Lorenz Graham’s John Brown Books. Humanities, 11(5), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11050124