Remapping Black Childhood in The Brownies’ Book

Abstract

:1. Introduction: New Cartographies

2. The Racialism of U.S. American Geography

LESSON I.

INTRODUCTION.

[For Recitation.]

1. What is the size and rank of Africa?

Africa ranks next to Asia in size, but it is the least important of the Grand Divisions, because it is the seat of no great civilized nations.

3. The Brownies Push Back

To Children, who with eager look

Scanned vainly library shelf and nook,

For History or Song or Story

That told of Colored Peoples’ glory,—

We dedicate THE BROWNIES’ BOOK.(“Dedication”, Fauset 1920b, p. 32)

Hie! hie! rise and hie

Away to the banks of the Yang-tze-ki!

There the giant mountains of Oshkosh stand,

And the icebergs gleam through the falling sand;

While the elephant sits on the palm-tree high,

And the cannibals feast on bad-boy pie.

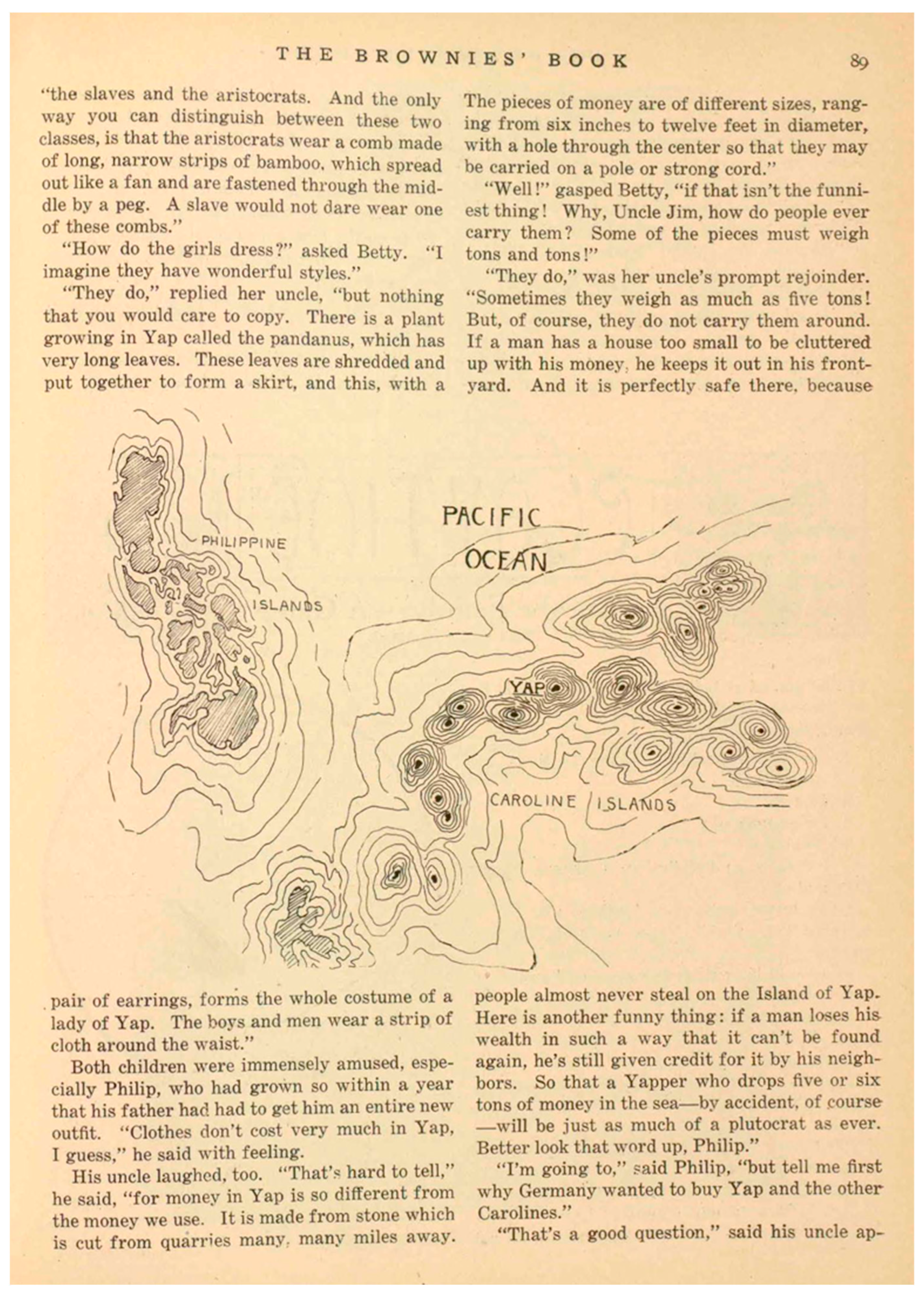

“Well,” said Uncle Jim, “let me see if I can make you see them plainly without the map. Do you know where China is?”

“Yes,” said Philip, “it’s in Asia, right on the Pacific Ocean.”

“Good,” said his uncle; “now the Philippine Islands are a large group of islands lying in the Pacific Ocean, south and east of China, directly east of French Indo-China, and north and west of Borneo. The China Sea is on the west of these islands, between China and the Philippines, and to the north and south and east lies the wonderful Pacific Ocean. Do you get the picture, Betty?”

The children then ask him why one of the girls was described as the daughter of a “bandit” (Over the Ocean Wave 1920, p. 10). Jim explains that she is actually the daughter of “a great Filipino leader” who, resenting U.S. rule in the Philippines after 1898, “waged warfare for a long time against the Americans. He was finally captured and banished by the new-comers in authority,” Jim explains (p. 10). He pauses, then continues: “‘Of course, according to them he was a bandit, or outlaw, —a person who breaks the laws. But in the eyes of his own countrymen he was probably regarded as a patriot. It all depends,’ said Uncle Jim, ‘on how you look at it’” (p. 10). Jim’s impromptu lesson turns out to be a “Geography Story” about questioning the dominant culture’s geography stories.“Yes,” said Betty, “I do.”

And Billy Hughes is just like me,

He stays back just as regularly!

He’s always hunting out strange places

Upon the globe, and then he traces

A map with towns and states and mountains,

And public parks with trees and fountains!

And this is what’s so queer to me—

Bill just can’t get geography

In school-time, and I’m awful dumb,

I cannot do one single sum.

But just let that old teacher go—

It is not simply that learning flourishes when figures of authority leave the room, it is that their absence provides an opportunity for someone like Billy—who does poorly in geography at school (he “can’t get” it)—to resist what he has likely been taught and to search out the knowledge that the teacher will not give him. That seems clearly to be the significance of the accompanying illustration (Figure 5), which shows Billy not just peering at the globe, but turning it specifically to Africa, sizing up the continent that his geography—and his teacher—have probably told him “is the least important of the Grand Divisions,” filled with “barbarous” people (Swinton 1875, p. 121). Billy is going to see for himself. The student standing to Billy’s right, who is not mentioned in the poem but who looks on in fascination as Billy turns the globe, suggests that this kind of radical re-learning is contagious. The stick-figure aesthetic of the illustrations by Laura Wheeler, who would go on to become one of the most prolific contributors to The Brownies’ Book and an important shaper of the “visual vocabulary” (Kirschke 2014, p. 85) of the magazine, moreover, recalls the kinds of drawings young children themselves might make, perhaps to imply that it is one of the students who has memorialized this counter-lesson in pen and ink. That the children’s heads are drawn like miniature globes seems deliberate as well, reinforcing the new connection between geography and identity that Billy discovers once he begins to teach himself.12There’s nothing Bill and me don’t know!

4. Ongoing Reverberations

This is as clear a statement of the impact of the routine and repetitive visual denigration of Blackness in U.S. geography textbooks as one could imagine. Although no response is offered in “The Jury,” which typically did not comment on the letters it printed, it may be no accident that Burrell’s “Geography Story” (1920) about the Sea Islands’ West African-influenced Gullah culture appeared so soon after Martin’s letter. And there was more to come. Indeed, “what better reply could there have been” to Martin’s frustration, Sinnette (1965) suggests, “than the short article by Kathleen Easmon written for the June 2021 issue entitled, ‘A Little Talk About West Africa’ [that] included a full-page photograph of West African students posing proudly outside their school much in the same way as high school students in Philadelphia” (p. 140). Once again, The Brownies’ Book helps picture—literally—an alternative geography that takes Black subjects seriously.In the geography lesson, when we read about the different people who live in the world, all the pictures are pretty, nice-looking men and women, except the Africans. They always look so ugly. I don’t mean to make fun of them, for I am not pretty myself; but I know not all colored people look like me. I see lots of ugly white people, too; but not all white people look like them, and they are not the ones they put in the geography. Last week the girl across the aisle from me in school looked at the picture and laughed and whispered something about it to her friend. And they both looked at me. It made me so angry. Mother said for me to write you about it.

“And I,” said the Judge, “would say Africa.”

They all stared at him.

“Are you joking?” asked Billy.

“No.”

The children insist that he cannot really mean it.

“I suppose,” pouted Wilhemina [one of the older children], “that you’re just saying Africa because we are all of African descent. Of course—”

“Do I usually lie?” asked the Judge.

“No-o oh no!—but how on earth can you say that Africa is the greatest continent? It is stuck way in the back of the Atlas and the geography which Billy uses, devotes only a paragraph to it.”

The Judge then provides seven detailed reasons for this opinion, each full of information that the children have clearly never encountered in any geography they have ever been assigned. Given how radically this information is intended to revise the common understanding of Africa circulating in U.S. classrooms, how central this lesson is to the larger project of geographic counter-pedagogy in The Brownies’ Book that we have been tracing, and how emphatically the Judge presents this information, all seven reasons are worth recounting in full:“I say it because I believe it is so. Not because I want to believe it is true—not because I think it ought to be true, but because in my humble opinion it is true.”

“First: Africa was the only continent with a climate mild and salubrious enough to foster the beginnings of human culture.

“Second: Africa excels all other continents in the variety and luxuriance of its natural products.

“Third: In Africa originated probably the first, certainly the longest, most vigorous, human civilization.

“Fourth: Africa made the first great step in human culture by discovery the use of iron.

“Fifth: Art in form and rhythm, drawing and music found its earliest and most promising beginnings in Africa.

“Sixth: Trade in Africa was the beginning of modern world commerce.

It is a tour de force presentation, to be sure. The younger children are mostly nonplussed (“‘Don’t understand,’ wailed Billikins” (p. 168)), but the older children quickly see the implications of what the Judge has told them. Wilhelmina then poses the question that The Brownies’ Book has been priming readers to ask from the very first issue:“Seventh: Out of enslavement and degradation on a scale such as humanity nowhere else has suffered, Africa still stands today, with her gift of world labor that has raised the great crops of Sugar, Rice, Tobacco and Cotton and which lie at the foundation of modern industrial democracy.”.

“I was just wondering,” mused Wilhelmina, “who the guys are that write our histories and geographies.”

“Well you can bet they’re not colored,” said William.

“No—not yet,” said the Judge.

5. Conclusion: No Apologies

This is the last Brownies’ Book. For twenty-four months we have brought Joy and Knowledge to four thousand Brownies stretched from Oregon to Florida. But there are two million Brownies in the United States, and unless we got at least one in every hundred to read our pages and help pay printing, we knew we must at last cease to be. And now the month has come to say goodbye. We are sorry—much sorrier than any of you, for it has all been such fun. After all—who knows—perhaps we shall meet again.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | See Wilson (2013) for more on the disproportionate precarity that made Black magazine publishing “such a tenuous venture in the nineteenth century” (p. 19) compared to more established white periodicals, including a smaller pool of readers from which to draw a subscriber base, fewer opportunities for capitalization by major publishing houses, and less access to printers and binders supportive of African American print culture. Even the Crisis, one of the most successful Black periodicals of the early twentieth century, was not financially self-supporting until 1916, six years after publishing its first issue. See Du Bois (1920b, p. 3). |

| 3 | As Fielder (2019) notes, “the children’s sections of early African American newspapers such as the Colored American and the Christian Recorder recognized the need to address Black children in the larger context of nineteenth-century African American print culture” (p. 160), demonstrating that Black children “were already acknowledged and taken seriously” (p. 160) even in the early days of Black periodical publishing. In the late 1880s, Amelia Etta Hall Johnson, “one of the first known African American writers to devote a considerable part of her creative efforts to producing imaginative literature for Black children” (Bishop 2007, p. 16), also published two magazines for children, The Joy and The Ivy, that have not yet been recovered. |

| 4 | See Smith (n.d.b) for a detailed discussion of the decision to expand the annual Children’s Number of the Crisis into The Brownies’ Book. Du Bois’s well-known engagement with Ethiopianism, as well as his ongoing support for the Pan-Africanist movement, not only helps account for the increasing presence of images of Africa in the Crisis, as Kirschke (2004) has shown, but also likely helped shape the general Pan-African ethos, visual and otherwise, of The Brownies’ Book, starting with the images of Abyssinia that appear in the first issue of the magazine. |

| 5 | Du Bois (1940) would later note that he was subject to this same geographic pedagogy during his own childhood. “The history and development of the race concept in the world and particularly in America, was naturally reflected in the education offered me,” he writes in Dusk of Dawn. “In the elementary school it came only in the matter of geography when the races of the world were pictured: Indians, Negroes and Chinese, by their most uncivilized and bizarre representatives; the whites by some kindly and distinguished-looking philanthropist” (Du Bois 1940, p. 101). |

| 6 | See Sinnette (1965); Kory (2001) for excellent accounts of St. Nicholas’s “unself-conscious Eurocentrism” (Kory 2001, p. 93) and its “hostile environment” of “gross” racial “caricature” (Sinnette 1965, pp. 134–35). Kory (2001) notes that “throughout St. Nicholas, various distancing strategies—linguistic, geographic, temporal—insulate its readers from confrontations with contemporary African Americans, even fictional ones,” and that “the underlying racism of St. Nicholas became more, not less, pronounced as it entered the 1920s” (p. 94). |

| 7 | Neither Forman nor Teall was in any sense an internationalist like Du Bois. When Forman was selected to conduct “The Watch Tower,” he was the author of high school civics and American history textbooks (Forman 1915, p. 963). When Teall succeeded him in November 1917, he was a New York-based editor, author, and book reviewer (Edward Nelson Teall 1920, p. 2794). Teall remained in charge of “The Watch Tower” until 1927. |

| 8 | As Wright (2017); Fielder (2017); and Gardner (2017) have shown, Black periodical editors were usually not only familiar with other mainstream white publications, they also ”reprinted widely” (Wright 2017, p. 148) from them, especially in the nineteenth century. Given the cultural prominence of St. Nicholas—which was read in Black households as well as white—it is very reasonable to believe that Du Bois and Fauset were well-informed about, if not readers of, that magazine. Indeed, the very name of their enterprise—The Brownies’ Book—in part signifies on the work of one of the best-known contributors to St. Nicholas: Palmer Cox, whose stories and illustrations of elflike “brownies” had begun appearing in that magazine in the early 1880s. See (Kory 2001). |

| 9 | There is not space to provide a full accounting of these different approaches here, but a comparison of the tables of contents for the January 1920 issues of The Brownies’ Book and St. Nicholas will suggest just how little social scientific material the latter magazine tended to include, as well as how infrequently it was integrated into other materials. |

| 10 | Of the critical attention paid to the social scientific dimensions of The Brownies’ Book, no work has quite illuminated the crucial partnership between the social sciences, literature, and the arts that I argue for here. Curry (2015), for example, has helpfully considered the “sociological significance” (p. 1) of The Brownies’ Book, highlighting the ways it reflects Du Bois’s interests in history, sociology, and ethnology, but the main purpose of Curry’s article is to challenge critiques by contemporary scholars of Du Bois’s gender politics. Young’s (2009) valuable examination of the “culture-based instructional design” (p. 1) of The Brownies’ Book, which carefully charts the ideas, themes, and concepts present in each department of the magazine, comes closest to my interests, though Young’s principal aim is to consider the implications of her findings for contemporary instructional design. |

| 11 | It is tempting to see The Brownies’ Book’s “Geography Stories” as a deliberate response to the “Plantation Stories” that commonly appeared in St. Nicholas before 1920. As Kory (2001) notes, not only do these plantation tales foreground “an extreme regional specificity,” they also allow the editors to “elide the ‘Great Migration’ from the South to the North that took place after World War I” thereby “avoid[ing] any discussion” of contemporary race relations (pp. 94–95). |

| 12 | Kirschke (2014) uses the phrase “visual vocabulary” to refer to Du Bois’s use of “art, drawings, cartoons, and photography” (p. 85) in the Crisis, but it applies equally well to Wheeler’s contributions to The Brownies’ Book. Wheeler’s story deserves to be better known. Trained first in the U.S. and then in Europe, where she first met Jessie Fauset, Wheeler was already an established illustrator for the Crisis—and on her way to becoming the “most frequently featured woman artist” (Kirschke 2014, p. 91) in that journal—when Du Bois invited her to contribute to The Brownies’ Book. Across its two-year run, Wheeler would publish more than two dozen illustrations in The Brownies’s Book, including four covers; only Hilda Rue Wilkinson contributed more drawings to the magazine. Although it is not clear whether Wheeler helped conceptualize the geographic discourse of the periodical, her drawings, “with their delicate pen-and-ink lines and precise details” (Goeser 2007, p. 67), certainly helped establish the magazine’s visual aesthetic and often accompanied the “geography” stories published therein. She also illustrated many of the African and African American folk tales that appeared in The Brownies’ Book. Wheeler’s body of work also makes clear that the unrefined aesthetic of the illustrations in “After School” is the result of deliberate choice rather than lack of ability. |

| 13 | When Yap reappeared in Du Bois’s “As the Crow Flies” columns the following year, after the Paris Peace Conference, which followed the First World War, “assigned” it to Japan over U.S. objections (Du Bois 1921, p. 114), readers of the magazine would likely have recalled learning about it first in “A Strange Country.” |

| 14 | Capshaw (2021) sees a similar ethos at work in Burrell’s contribution to the “Playtime” department the following month of “Four Games from St. Helena.” Instead of adopting the patronizing tone of contemporary white ethnographers of Gullah culture such as Elsie Clews Parsons, who collected Gullah folklore on a visit in 1919, Burrell “frames the games as an opportunity for a friendly meeting” rather than a cultural oddity and “avoids exoticizing or spectacularizing the Sea Islands” (Capshaw 2021, pp. 376–77). |

| 15 | In the typescript copy of “A Curious Geography Lesson” held in the W. E. B. Du Bois Papers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, “by Yolande Du Bois” appears in pencil beneath the title (Y. Du Bois 1920). There is no correspondence in the archive indicating whether the story was formally submitted to The Brownies’ Book. Yolande’s choice of Abyssinia as the focus of her story, and especially her emphasis on Menelik’s preservation of Ethiopian independence, suggests the enduring appeal that an independent Ethiopia held for many African Americans in 1920. After the first issue of The Brownies’ Book, however, Ethiopia rarely appears in the magazine. For more on both “A Curious Geography Lesson” and “The Land Behind the Sun,” the story Yolande published in The Brownies’ Book in 1921, see Green (2022). |

| 16 | As though recognizing that it may be some time before the children write their “new geography,” in the next two installments of “The Judge,” August 1921 and September 1921, Fauset offers readers suggestions for good books about Africa that they can read right now, making six consecutive columns focused on geography and pedagogy. |

References

- A Strange Country. 1920. The Brownies’ Book 1: 87–90.

- Bishop, Rudine Sims. 2007. Free Within Ourselves: The Development of African American Children’s Literature. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, Martin. 2006. The Geographic Revolution in Early America: Maps, Literacy, and National Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burrell, Julia Price. 1920. The quaintness of St. Helena. The Brownies’ Book 1: 245–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, Victoria E. M. 2015. Seeing the world: Media and vision in US geography classrooms, 1890–1930. Early Popular Visual Culture 13: 276–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capshaw, Katharine. 2021. “Come on in”: Play as community and liberation in The Brownies’ Book. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 14: 367–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, Tommy. 2015. It’s for the kids: The sociological significance of W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Brownies’ Book and their philosophical relevance for our understanding of gender in the ethnological age. Graduate Philosophy Faculty Journal 26: 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, Richard Elwood. 1906. Dodge’s Elementary Geography. Chicago: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1919. The true brownies. The Crisis 18: 285–86. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1920a. As the crow flies. The Brownies’ Book 1: 23–25, 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1920b. Report of the Director of Publications and Research of the N.A.A.C.P. and Editor of the Crisis. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1921. As the crow flies. The Brownies’ Book 2: 114–15. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 1940. Dusk of Dawn: An Essay toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B., and Jessie Fauset, eds. 1920. The Brownies’ Book 1. New York: DuBois and Dill. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B., and Jessie Fauset, eds. 1921. The Brownies’ Book 2. New York: DuBois and Dill. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, Yolande. 1920. A Curious Geography Lesson. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Edward Nelson Teall. 1920. Who’s Who in America. vol. XI (1920–1921), Edited by Albert Nelson Marquis. Chicago: A.N. Marquis and Company, p. 2794. [Google Scholar]

- Fauset, Jessie. 1920a. After School. The Brownies’ Book 1: 30. [Google Scholar]

- Fauset, Jessie. 1920b. Dedication. The Brownies’ Book 1: 32. [Google Scholar]

- Fauset, Jessie. 1921. The Judge. The Brownies’ Book 2: 108, 134, 168, 202, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Fielder, Brigitte. 2017. “No rights that any body is bound to respect”: Pets, race, and African American child readers. In Who Writes for Black Children? African American Children’s Literature before 1900. Edited by Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 164–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fielder, Brigitte. 2019. Before The Brownies’ Book. The Lion and the Unicorn 43: 159–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielder, Brigitte. 2021. “As the crow flies”: Black children, flying Africans, and fantastic futures in The Brownies’ Book. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 14: 413–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, S. E. 1915. The watch tower. St. Nicholas 42: 963–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, Eric. 2017. Children’s literature in the Christian Recorder: An initial comparative bibliography for May 1862 and April 1873. In Who Writes for Black Children? African American Children’s Literature before 1900. Edited by Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 225–45. [Google Scholar]

- Goeser, Caroline. 2007. Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Tara T. 2022. See Me Naked: Black Women Defining Pleasure in the Interwar Era. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschke, Amy. 2004. Du Bois, The Crisis, and images of Africa and the diaspora. In African Diasporas in the New and Old Worlds. Edited by Geneviève Fabre and Klaus Benesch. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, pp. 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschke, Amy Helene. 2014. Laura Wheeler Waring and the women illustrators of the Harlem Renaissance. In Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Edited by Amy Helene Kirschke. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kory, Fern. 2001. Once upon a time in Aframerica: The “peculiar” significance of fairies in the Brownies’ Book. Children’s Literature 29: 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, Alice. 1920. Letter to the editor. The Brownies’ Book 1: 178. [Google Scholar]

- Oeur, Freeden Blume. 2021. The children of the sun: Celebrating the one hundred-year anniversary of The Brownies’ Book. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 14: 329–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Over the Ocean Wave. 1920. The Brownies’ Book 1: 9–10.

- Phillips, Michelle H. 2013. The children of double consciousness: From The Souls of Black Folk to The Brownies’ Book. PMLA 128: 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, Norman. 1915. In the watch tower. St. Nicholas 42: 962. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Laura E. 1878. Tommy’s dream; or, the geography demon. St. Nicholas 5: 213–4. [Google Scholar]

- Shulten, Susan. 2001. The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880–1950. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnette, Elinor Desverney. 1965. The Brownies’ Book: A pioneer publication for children. Freedomways 5: 133–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Katharine Capshaw. n.d.a The Brownies’ Book. The Tar Baby and the Tomahawk: Race and Ethnic Images in American Children’s Literature 1880–1939. Available online: http://childlit.unl.edu/topics/edi.brownies.html (accessed on 29 April 2022).

- Smith, Katharine Capshaw. n.d.b The Brownies’ Book and the Roots of African American Children’s Literature. The Tar Baby and the Tomahawk: Race and Ethnic Images in American Children’s Literature, 1880–1939. Available online: http://childlit.unl.edu/topics/edi.harlem.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Swinton, William. 1875. Elementary Course in Geography. New York and Chicago: Ivison, Blakeman and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth. 2019. Notes toward a Black fantastic: Black Atlantic flights beyond Afrofuturism in young adult literature. The Lion and the Unicorn 43: 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Ebony Elizabeth. 2021. We have always dreamed of (Afro)futures: The Brownies’ Book and the Black fantastic storytelling tradition. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 14: 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, Evelyn. 1921. Letter to the editor. The Brownies’ Book 2: 298. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, Crystal Lynn. 2021. “Transfiguring the soul of childhood”: Du Bois’s private vision and public activism for Black children. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 14: 347–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Ivy G. 2013. The brief wondrous life of the Anglo-African Magazine; or, antebellum African American editorial practice and its afterlives. In Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850. Edited by George Hutchinson and John K. Young. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Nazera Sadiq. 2017. “Our hope is in the rising generation”: Locating African American children’s literature in the Children’s Department of the Colored American. In Who Writes for Black Children? African American Children’s Literature before 1900. Edited by Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane. Ann Arbor: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 147–63. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Patricia A. 2009. The Brownies’ Book (1920–1921): Exploring the past to elucidate the future of instructional design. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 8: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gleason, W. Remapping Black Childhood in The Brownies’ Book. Humanities 2022, 11, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11030072

Gleason W. Remapping Black Childhood in The Brownies’ Book. Humanities. 2022; 11(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleGleason, William. 2022. "Remapping Black Childhood in The Brownies’ Book" Humanities 11, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11030072

APA StyleGleason, W. (2022). Remapping Black Childhood in The Brownies’ Book. Humanities, 11(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11030072