Abstract

This essay examines Georgia Douglas Johnson’s poetic depictions of Black motherhood and childhood in the annual “Children’s Numbers” of The Crisis that appeared from 1912 to 1934. Visually and discursively, the run of “Children’s Numbers” stages the modern crucible of educating Black children on the realities of racism and contends with racialized notions of childhood innocence. This essay considers how Johnson’s poems respond to such ideas of education and innocence in W.E.B. Du Bois’ editorials on childhood and the photographs of Black children that appeared in these issues. Focusing primarily on Johnson’s motherhood poems that appeared in the “Children’s Numbers” and the striking photographs of children that accompanied these poems, this essay asserts that Johnson’s poems disrupt racialized notions of childhood innocence, intervene in discourses on Black education, and challenge the representational politics of the “Children’s Numbers” by centering the epistemological perspective of Black motherhood. Furthermore, this essay argues for the benefits of reading Johnson’s motherhood poems in relation to her erotic poetry, demonstrating that Johnson’s poetry of Black motherhood addresses the sexual politics of the Black bourgeoisie at the turn of the century and creates a space for the expression of Black female sexuality.

1. Introduction

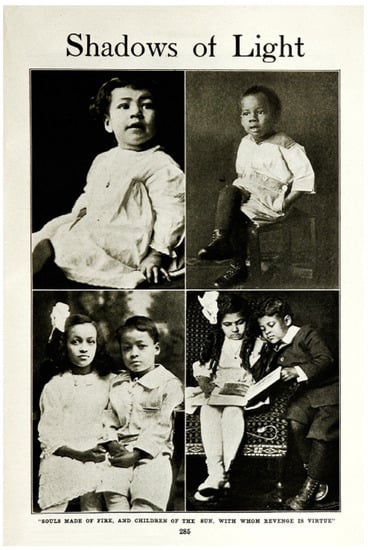

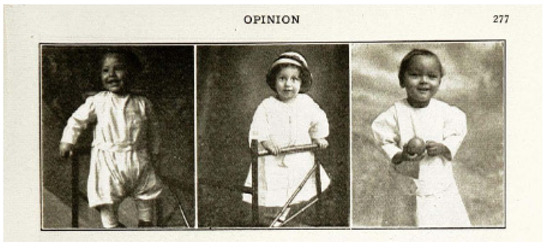

Between 1912 and 1934, the October issues of The Crisis were dubbed the “Children’s Numbers,” what editor W.E.B. Du Bois lyrically described as “a sort of annual festival decorated with [children’s] flowering faces and their wonder-filled eyes and the mighty softness of their hands”1 (Du Bois 1916, pp. 267–68). A decidedly visual celebration and, according to Du Bois, “easily the [magazine’s] most popular number of the year” (Du Bois 1919, p. 285), these issues feature hundreds of photographs of Black children submitted to the magazine by parents and relatives, and they make a show of highlighting the tremendous volume of photographs they contain; the 1915 Children’s Number, for example, boasts “Selected Pictures of Seventy-Nine of Our Baby Friends” and many more drawn, painted, and photographed images (The Crisis 1915). Of course, this calculus of (pictorial) representation recalls the numerological basis of Du Bois’ formulation of the “Talented Tenth,” a representational strategy focused on highlighting the group that lifts up, carries, signifies, and legitimizes the other ninety percent. And, indeed, the photographs and pictures of children presented by the Children’s Numbers reinforce the many political ideals of racial uplift ideology at the turn of the twentieth century. Julie Taylor (2020) argues that the photographs of children in these issues “conform to middle-class images of idealized childhood” and “provide a visual representation of the important ideological and symbolic work performed by the child” in the discourses of the New Negro and Harlem Renaissances; in particular, the magazine features “formal studio portraits” of well-dressed “babies and small children” with few candid shots, outdoor settings, or older children and teenagers appearing (Figure 1). Echoing critical attitudes regarding the poetry published in The Crisis in its first decades as a magazine, Taylor also asserts that these portraits of children recreate and rely upon conventions “established during the nineteenth century” (pp. 737–38).

Figure 1.

Sample pages from the 1916 Children’s Number’s “Shadows of Light” column, a recurring section that features numerous such grids of photographs of children. (The Crisis 1916, 12.6, pp. 285–86), The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/, (accessed on 4 December 2018).

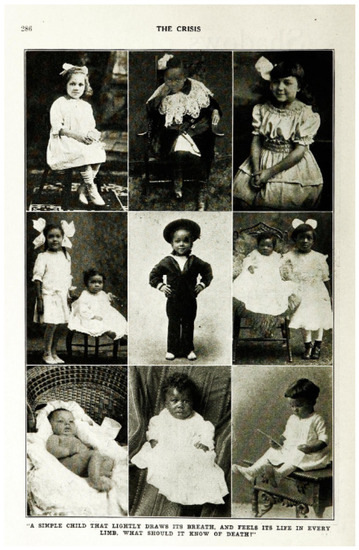

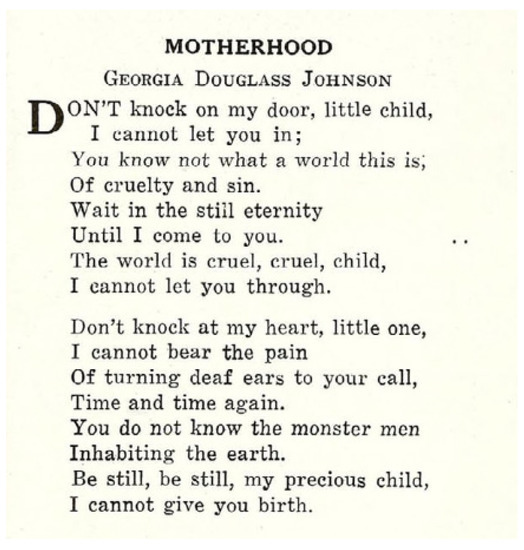

Such criticism has certainly been lodged against Georgia Douglas Johnson,2 whose poetry of Black motherhood and childhood features prominently in multiple editions of the Children’s Numbers and, in many ways, epitomizes the project set forth by the Children’s Numbers. Confirming Du Bois and the editorial team’s choice of Johnson as the representative poet of Black motherhood, the 1917 Children’s Number spotlights six of Johnson’s poems, the first time the magazine offered such a featured showcase to a woman poet (Figure 2). In addition to speaking directly with the many editorials that Du Bois penned for these issues of the magazine about the challenges and prospects of raising Black children in America, Johnson’s Crisis poetry dramatizes the crucible of racial education for Black children and mothers in order to respond to the Jim Crow imagery that depicted Black children as incapable of education or civilization and denied them the status of innocence. At the same time, Johnson’s poems of Black motherhood maintain a complex relationship with the photographs of children that appeared in the Children’s Numbers. While, like these photographs, Johnson reverently upholds the Black child as a potent symbol of possibility and potential for social mobility, she leverages the narrative and lyric dimensions of poetry to articulate a distinctly Black feminine sexuality and agency while navigating the strictures of middle-class gender politics.

Figure 2.

Georgia Douglas Johnson’s six poems featured in the 1917 edition of The Crisis’s Children’s Numbers. (The Crisis 1917, 14.6, p. 293), The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510854/, (accessed on 17 January 2022).

Taken together with the photographs of children presented in The Crisis’ Children’s Numbers, Johnson’s poetry of Black childhood and motherhood also grapples with the changing representational regime of modern visual culture at the turn of the twentieth century and, in particular, the tension between “the ethnographic or documentary” mode and a more conventional and artificial one, namely “the studio portrait style” so popular in nineteenth-century photography (Taylor 2020, p. 760).3 This tension between documentation and narrative finds its analogue in Johnson’s poetry of Black motherhood, wherein she depicts mothers “confounded in [their] role to raise a ‘mantled’ child”, marked by the sign of Blackness in a white supremacist world (Pinkard 2015, p. 218). As Shawn Michelle Smith (2004) documents in her study of Du Bois’ photographic exhibition at the 1900 Paris Exhibition, one way in which racist imagery sought to call the moral character of African Americans into question was by specifically marking Black Americans as sexually dysfunctional and thus unfit for civilized life: in such minstrel imagery, “sexuality is constructed as the inassimilable mark of blackness” and a clear indicator of Black Americans’ lack of fitness for “middle-class” life (pp. 82–83). Du Bois’ response to such imagery was to promulgate images of “African American patriarchy, a black middle class” distinguished by “the performance of gendered respectability and sexual control” (ibid., p. 79). Hand in hand with this imagery, Du Bois denounced “sexual looseness”, aiming his critique “at African Americans themselves, and especially at African American women” (ibid., p. 87). Even as he castigated the overly sexualized nature he presumed in Black women, Du Bois also promoted visual and literary representations “confining the African American woman to her role as mother”, seeing in the Black mother “the epitome of virtue—as long as she keeps her adoring gaze focused on an idealized African American masculinity” (ibid., p. 40). The photographic archive that Du Bois cultivates in the Children’s Numbers of The Crisis seeks to legitimize Black sexuality by training the reader’s attention on its most sanctioned purpose: childbearing and, in particular, the rearing of respectable and well-mannered children capable of growing into responsible and upstanding citizens. Johnson’s poetry of motherhood and childhood rejects and subtly critiques Du Bois’ impulse to sanitize the erotic dimensions of childbearing through the omission of sensuality and pleasure. Although Johnson’s poetry might reinforce and even reproduce Du Bois’ cherished image of the Black mother staring lovingly at her male child, Johnson challenges Du Bois’ erasure of the sexuality of the Black mother by engaging the narrative mode to place the child’s life in the context of his relationship with his mother, centering the mother’s affective and psychic life in the process.

2. Johnson, Maternity, and Eroticism

Johnson’s earliest poetry—much of which appeared in The Crisis and her first volume of poems, The Heart of a Woman—centers Black femininity by examining two concerns in depth and, occasionally, in juxtaposition: Black motherhood and the erotic inner lives of Black women. Literary histories that consider Johnson’s career cast her 1922 book of poems Bronze as a development of her racial consciousness spurred on by criticisms that her earlier poetry was not political or race-conscious enough. However, Johnson began writing poems that overtly addressed racial politics very early in her career, even before she published her first book The Heart of a Woman in 1918. “My Little One”, one of the first poems Johnson published in The Crisis, serves as one pointed example of the overt politics of Johnson’s earliest periodical poetry. The publication history of this poem—its initial placement in the 1916 “Children’s Issue” of The Crisis and Johnson’s strategic choice to revise and republish it in her 1922 volume Bronze with an altered title—provides a number of insights into the politics of Black motherhood that suffuse Johnson’s earliest poetry. In particular, reading Johnson’s poems about Black motherhood and childhood with their publication history in mind allows us to place these poems in conversation with Johnson’s erotic poetry, illuminating how Johnson’s poetry of Black motherhood addresses the sexual politics of the Black bourgeoisie at the turn of the century and the gendered and racial dimensions of modern(ist) pleasure. In her poems about children and parenting that appeared in the Children’s Numbers of The Crisis, Johnson’s eroticism offers a site wherein she can explore sexuality, pleasure, danger, and the intersection of racial and gendered politics while “defin[ing] and preserv[ing] her subjectivity” as “a middle-aged black woman,” in Claudia Tate’s words (Tate 1997, p. xviii). As Johnson’s poems reveal, this subjectivity maintains a complex relationship with motherhood and sexuality, one in which Johnson “eroticized [her] despair” while writing “from the vantage point of the lyrical wife and mother” (Tate 1997, pp. xlv–xlvi). In reading Johnson’s poems about Black motherhood and childhood in juxtaposition with her erotic poems, I contend that Johnson sees the fate of the Black child and the Black mother intertwined in an act of mourning that also enables a particularly sensual and sexual expression of Black motherhood, a complex site where pleasure, danger, confinement, self-representation, and political subversion intersect.

Johnson’s erotic poems confront the sexual lacuna of modernity, Blackness, and femininity—namely the presumed licentiousness of Black women—and attempt to represent Black women’s sexuality while retaining the dignity that middle-class standards demand. Tate (1997) writes that Johnson encoded sexual desire and sensual pleasure-taking “behind the demeanor of ‘the lady poet’” (p. xviii). Motherhood offers a particularly potent but also dangerous site in this stratagem, as “proper” motherhood could certainly obtain for Johnson the dignity of “ladyhood,” while any errant eroticism or deviation from the heteronormative standard of childbearing would be fastidiously redressed. And yet, it is in her depiction of motherhood that Johnson is most willing to provoke. Perhaps the clearest example of the connection between Black women’s sexuality and Black motherhood in Johnson’s poetry is “Black Woman,” a poem in which a speaker addresses her unborn child, begging the child not to be born. Using the metaphor of the mother’s body as a door, the poem depicts a would-be Black mother who fears giving birth lest she expose her child to the racist world:

- Don’t knock at my door, little child,

- I cannot let you in,

- You know not what a world this is

- Of cruelty and sin.

- Wait in the still eternity

- Until I come to you,

- The world is cruel, cruel, child,

- I cannot let you in!

- Don’t knock at my heart, little one,

- I cannot bear the pain

- Of turning deaf-ear to your call

- Time and time again!

- You do not know the monster men

- Inhabiting the earth,

- Be still, be still, my precious child,

- I must not give you birth!

(Johnson 1922a, p. 43)

In its provocative title, this poem suggests that the speaker’s condition emblematizes the psychic life of Black womanhood in America. Returning to the kind of domestic imagery she explores in depth in her first book of lyrics, The Heart of a Woman, Johnson depicts the potential mother’s body as a dwelling place, the door of which connects an inner and an outer world. The door metaphor also recalls the title poem of Heart, in which a bird caged at night stands in for the heart of womankind, connecting sexual pleasure and desire with the inevitable fate of domestic imprisonment. Indeed, the “knocking” that the Black woman endures “time and time again” recalls the slang of “knocked up,” the coinage of which the Oxford English Dictionary Online (2022) records as distinctly American and of the slavery period: according to the OED, to knock up as in “[t]o make (a woman) pregnant” originates from 1813. The OED also records an early usage of this phrase in the fictionalized journal of Davy Crockett published in 1836, Exploits & Adventures in Texas, in which the American folk hero recounts learning that enslaved Black women “are knocked down by the auctioneer, and knocked up by the purchaser.” Perhaps this particular usage of “knock” stems from the earlier idiom “to knock a child (or an apple) out (of)” someone. I mention these etymological origins not to suggest that Johnson appropriates them, but specifically to consider how she inverts and subverts them: whereas the phrases “to knock up” and “to knock a child out of” make the woman’s body syntactically and semantically into an object for childbearing, “knocking” in Johnson’s poem is the action of the child, rather than the male lover, and the poem creates a space in which the mother has recourse to anticipate and respond to this experience. Indeed, the occasion of the poem is the sexual act, which incites the speaker’s repeated appeal to the child to “[w]ait in the still eternity” of heaven (Johnson 1922a, p. 43). The poem, as such, devises a contemplative, lyrical, post-coital moment in which the Black feminine subjectivity can ruminate on the sexual experience and its relationship to the social order. Johnson positions sin decidedly outside of this space and time, not in the moment of sexual encounter but in the cruel world that undermines the Black woman’s pleasure in sex by turning the moment into one of anxiety and fear for the future.

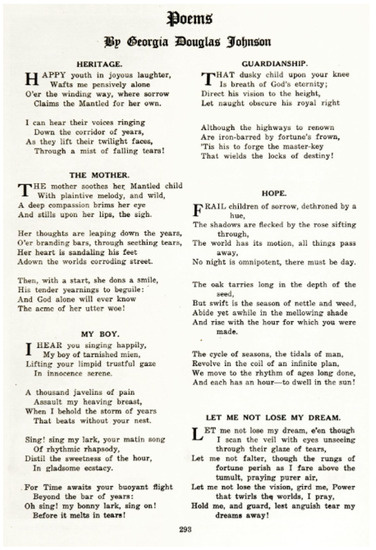

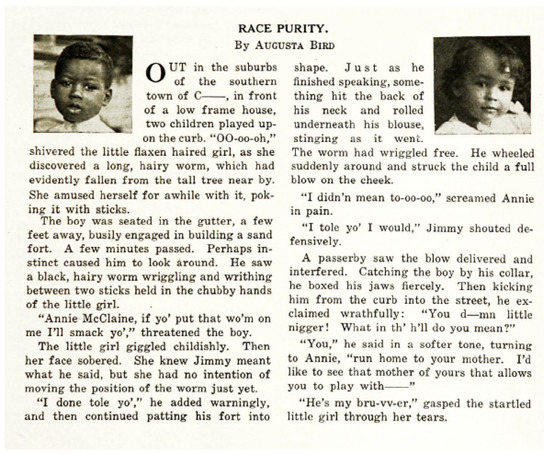

“Black Woman” first appeared (with an altered title) in the 1922 Children’s Number of The Crisis just one month prior to its inclusion in Johnson’s book of poems Bronze, published in November 1922. Given the proximity of the publication dates of these versions of the poem, I conclude that the editorial team of The Crisis chose to publish the poem under a different title, simply “Motherhood,” in an attempt to sanitize the poem’s politically charged conflation of Black female sexuality and undesired motherhood (Figure 3). Du Bois authored a lukewarm foreword for Bronze, wherein he clearly indicates the value that he does find in Johnson’s poems of Black motherhood and childhood:

Figure 3.

First published in the 1922 Children’s Number bearing the title “Motherhood,” Johnson would revise the title of this poem for publication in her second book of poems, Bronze, in which it appears as “Black Woman.” The Crisis October 1922, 24.6, p. 265, The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr521702/, (accessed on 30 May 2022).

Those who know what it means to be a colored woman in 1922—and know it not so much in fact as in feeling, apprehension, unrest and delicate yet stern thought—must read Georgia Douglas Johnson’s Bronze. Much of it will not touch this reader and that, and some of it will mystify and puzzle them as a sort of reiteration and over-emphasis. But none can fail to be caught here and there by a word—a phrase—a period that tells a life history or even paints the history of a generation.(Du Bois 1922, p. 7)

In particular, Du Bois singles out a line from Johnson’s “The Mother”, in which a Black woman’s heart “sandl[es]” the feet of “her mantled child” (Johnson 1922a, p. 41), as well as her depiction of Black adolescence in the image of a child “[s]eeking the breast of an unknown face” (ibid., p. 95). In highlighting these specific poetic lines, Du Bois centralizes the Black mother’s role as caregiver, sentimental educator, and, perhaps most importantly, as vessel for “the child as citizen in the making” (Taylor 2020, p. 769). Despite Du Bois’ claim that the ideal reader of Bronze is one who shares the “feeling[s]” and “apprehension[s]” of the Black woman in 1922 (Du Bois 1922, p. 7), his selections of exemplary images in Johnson’s poems excludes and erases the subjectivity of the Black mother. Save the altered title, Johnson made two small but significant changes to the version of “Black Woman” that appeared in The Crisis, revisions that further galvanize the central affective force of this poem as the psychic experience of Black womanhood. In the version that appears in Bronze, Johnson changes the concluding line of the first stanza, “I cannot let you through” in the Crisis version, to echo the second line, “I cannot let you in” (Johnson 1922b, p. 265; 1922a, p. 43; my italics). In revising the preposition “through” and replacing it with “in,” Johnson figures the mother’s body not as the gateway to the outer world, but as the door to her interior world. Further emphasizing the importance of this change, Johnson’s removal of “through” in favor of “in” disrupts the rhyme scheme of the poem. Johnson also altered the final line of the poem, which in the version that appeared in The Crisis reads “I cannot give you birth” (Johnson 1922b, p. 265). Johnson instead favored “I must not give you birth” in the latter version of the poem published in Bronze (Johnson 1922a, p. 43), placing greater emphasis on the decision-making faculty of the mother as well as the social pressure of the situation: the Black mother is caught between doing her feminine duty as bearer of the future upwardly mobile Black citizen—a fate that she fears will lead to the inevitable violence against the child by the white world of “monster men”—and forestalling her relationship with her child until the afterlife. Indeed, we may even read this poem as a rumination on the ethics of abortion for Black mothers, something of a spiritual precursor to Gwendolyn Brooks’ famous reflection on abortion, “The Mother”. Barbara Johnson (2009) writes that Brooks’ poem leverages apostrophe to animate the inanimate: “[a]s long as [the speaker-mother] addresses the children, she can keep them alive, can keep from finishing the act of killing them” (p. 212). “Black Woman” reclaims, if only for the moment of the short lyric, this agency to speak the Black woman’s psyche under the pressures of reproduction and sexuality into existence.

3. Photography and the Politics of Black Childhood

Du Bois composed multiple editorials for the Children’s Numbers, which clarify Du Bois’ representational politics in editing and publishing these issues, speak to the function of photography in these issues, and position Black mothers in particular roles within the discourse of Black childhood. Du Bois’ description of the Children’s Numbers as “a sort of annual festival decorated with [children’s] flowering faces and their wonder-filled eyes and the mighty softness of their hands” elucidates the project upon which these issues are founded—a celebration of the image and potential of the Black child—and identifies two dimensions of joy and pleasure in these images of children: these images evoke the pleasures enjoyed by children in order to conjure the joys of parenthood (Du Bois 1916, pp. 267–68). In “decorating” the Children’s Numbers with children’s “flowering faces and their wonder-filled eyes,” the magazine pays tribute to the delicate glee children should be afforded in infanthood and early adolescence.4 This pleasure is, of course, disrupted by the inevitable taint of racism, which will surely roughen “the mighty softness of their hands” (Figure 4). Each of the Children’s Numbers featured hundreds of photographs of African American children, most of which were sent in by readers. Du Bois, in an editorial that appeared in the 1916 Children’s Number, apologizes that the magazine could not use all of the photographs submitted for the issue. Du Bois writes: “They who look at you from these pages are but a little and imperfect selection of those who might. We have chosen them out of hundreds of their fellows and we are full of apologies to the mothers of those not chosen; after all, these are not individual children; they belong to no persons and no families; they belong to a great people and in their hands is that people’s future” (ibid., p. 268). This paragraph frames these photographs as artifacts of collective rather than individual significance; perhaps this explains the practice, common to the Children’s Numbers, of including large numbers of photographs rather than selecting a handful of exemplary children. Du Bois’ politics, we might say, were often representational over and against being individualist; perhaps his most famous formulation, the “talented tenth” ideology of racial uplift, relies on the power of representation, of the “top” ten percent to represent and therefore lift up the entire race. Thus, this apology, in its strange syntax, becomes not an apology but a justification, implying that the reader to whom Du Bois addresses this editorial is not one of the mothers for whom he feels he owes a strictly rhetorical apology; rather, it becomes an explanation for the necessity of the Children’s Numbers and of the representational politics that these issues of the magazine embrace. Once again, the image of a child’s hands comes to represent potential; taken together with the image of the “mighty softness” of a child’s hands, Du Bois’ depiction of Black children places firm emphasis on their ability to soften the future world, to make the world more equitable and empathetic to the cause of Black freedom. Though Du Bois seems to want to remove the mother from the photographic images of children—not only in this editorial, but also in the practice of recontextualizing the photos by placing them in large groups, effectively anonymizing the children and posing the photos as social rather than familial documents—this editorial curiously reinforces the Black woman’s role as mother, first and foremost. As it is the mothers of the children whose photographs were not chosen specifically to whom Du Bois feels he must apologize, he presumes that the role of the mother is self-evidently to be the tireless, energetic, and selfless promoter of her children, to “[play] a supporting role in the … child’s drama of racial identity” (Smith 2004, p. 40).

Figure 4.

In many images of children in The Crisis, their hands serve as a focal point. Children often grasp objects or hold their hands out in front of them, as in these images from the 1913 Children’s Number. (The Crisis 1913, 6.6, pp. 277–78), The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr517569/, (accessed on 8 December 2019).

Furthermore, Du Bois aligns the imagery of the child with the moral project of pre-Harlem Renaissance Black poetry that appeared in The Crisis by poets such as Johnson, William Stanley Braithwaite, and James D. Corrothers. Elizabeth Renker (2018) has coined the term “romantic idealism” to define the philosophical underpinning of this type of poetry, which seeks “a form of transcendent truth that derived its meaning from beyond the world of material circumstance” (p. 5). While not strictly the philosophy of Black poetry in America, there are clear affinities between romantic idealism and the project of racial uplift art, namely the belief in the power of art to enrich and better both the individual and social life, as well as a faith in the soul’s ability to endure the body’s experiences. The philosophy of romantic idealism was most vociferously upheld by Black middle-class artists and thinkers, who funneled this belief in the power of art to change the world into a political project aimed at obtaining Black freedom. Du Bois ([1926] 2006) famously defended this belief in the polarizing essay “Criteria of Negro Art”, wherein he asserted that “all art is propaganda” and that the end of Black art should be to attain “the right of black folk to love and enjoy” (p. 49). Georgia Douglas Johnson herself intervened in the debate about Black representation and its aims, siding firmly with Du Bois against those such as Alain Locke and Langston Hughes, who saw self-expression as the highest goal of art; Johnson ([1926] 2007) wrote that “the work of the artist” is to uphold “[t]he few who do break thru the hell-crust of prevalent conditions to high ground” and to “let the submerged man and the world see those who have proven stronger than the iron grip of circumstance” (p. 199).5 Critical to this belief in art as the ideal realm of the soul is an emphasis on the dreamworld that art creates outside of (or, more accurately, above) the material world. As such, the strain of Black Romanticism in early twentieth-century poetry, much like the English Romanticism of the nineteenth century, often upholds the child’s imagination as an ideal plane to which art should return the adult reader. In turn, the photographs of children in The Crisis appropriate “the Romantic and sentimental ideals of childhood,” in which “a form of ornate, lovingly curated decoration” constructs the Black child as “emotionally priceless” and “precious”, as well as “a figure for unlimited potentiality” (Taylor 2020, pp. 762, 773).

In his editorials that appeared in the Children’s Numbers, Du Bois offered up the experience of educating children as a particularly painful example of double consciousness. In the 1912 issue that inaugurated the annual Children’s Numbers, Du Bois asks how “honest colored men and women battling for [the] great principle” of raising children should approach teaching those children about racial inequality. Du Bois shows just how delicate is this issue: “Our first impulse is to shield our children absolutely. Look at these happy little innocent faces: for most of them there is as yet no shadow, no thought of a color line” (Du Bois 1912, p. 287). Quick to emphasize the innocence that will be shattered, Du Bois nevertheless warns against “introduc[ing] the child to race consciousness prematurely” and the “[danger of] let[ting] that consciousness grow spontaneously without intelligent guidance” (ibid., p. 288). In other words, Du Bois suggests that the parents of Black children must carefully navigate the vicissitudes of innocence. Innocence is also a central preoccupation of Johnson’s motherhood poems and an idea that has a distinctly racialized history.

The crucible of education for Black Americans is the double bind of conducting racial education and of timing that education—a particular example of the “double consciousness” of Black America. In the 1912 issue, this problem remains for Du Bois an issue for individual parents to agonize over. However, by 1919, Du Bois came to see the hand that The Crisis played in the racial education of African American children. In the 1919 Children’s Number, he writes: “To the consternation of the editors of The Crisis we have had to record some horror in nearly every Children’s Number,” then gives the examples of lynchings and race riots (Du Bois 1919, p. 285). “This was inevitable in our role as newspaper,” he writes, “but what effect must it have on our children? To educate them in human hatred is more disastrous to them than to the hated; to seek to raise them in ignorance of their racial identity and peculiar situation is inadvisable—impossible” (ibid.).6 Throughout these editorials, Du Bois weighs the slight and often ambiguous differences between ignorance and innocence. The double bind stems from two difficult positions: to either keep the Black child in ignorance of racial hatred and oppression or to destroy their innocence by teaching them about the evils of racism.

The issue of an audience of children dramatizes what for Du Bois was a larger project of The Crisis, to present, in the words of Jenny Woodley (2014), “images that showed a side to black life that challenged racial stereotypes” (p. 63). Woodley’s words suggest that this “side”, perhaps like the dark side of the moon, remained occluded from white vision. What role did the photography of children play in this goal of showing images “that challenged racial stereotypes”? Two qualities of the Children’s Number photos that immediately strike the eye are the use of very dark backgrounds and the tendency for the children in them to be dressed in white clothing (Figure 5). Perhaps, in making this choice, Du Bois and the editors are signifying on the tradition of chiaroscuro, the use of emphasized contrasts of light and darkness to give dimension and depth to paintings. The photographs clearly attest to the need for a more dimensional and human visual culture of Black childhood. In one editorial from 1918 titled “About Pictures,” Du Bois also calls for submissions of “beautiful baby pictures” in the form of “shiny black and white photograph[s], clear and sharp in outline and not too small in size” in order to avoid “indistinct browns and grays” (Du Bois 1918, p. 268). In such photos, there is little room for ambiguity: the magazine favors images in which children are bright spots surrounded by darkness, by the “shadow” that is the color line, in Du Bois’ words. Michelle H. Phillips (2013) points to juxtapositions of children’s photographs in The Crisis with articles regarding violent acts of racism, arguing that such juxtapositions “create enormous interpretive gaps … by contrasting entire pages of smiling faces, white bows, and white dresses with reminders of suffering and death” (p. 595). In doing so, the magazine dramatizes the experience of double consciousness, “the history” of which, according to Phillips, “for black Americans lies in childhood” (ibid., p. 592).

Figure 5.

A page from the 1919 Children’s Number demonstrating the sharp contrast of light and dark tones that characterizes many photos in these issues. (The Crisis 1919, 18.6, p. 292), The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr512545/, (accessed on 17 January 2022).

Robin Bernstein (2011) demonstrates that the color line was as pronounced for children as for adults, although with slightly different effects. Bernstein’s work provides an insightful history of the racialization of childhood, a history that can be traced through a genealogy of the idea of childhood innocence, an ideological formulation refused to African American children. Bernstein writes that “[t]he connection between childhood and innocence is not essential but instead historically located” (p. 4) Innocence as the essentialized quality of childhood stems from “late eighteenth and early nineteenth century” racial ideologies that cohere in and through “sentimental culture” (ibid.) Most emblematic of this sentimental vision of childhood innocence is Little Eva of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, who epitomizes the construction of innocent children as “sinless, absent of sexual feelings, and oblivious to worldly concerns” (ibid.). “This innocence,” Bernstein asserts, “was raced white” (ibid.). Indeed, the Children’s Numbers of The Crisis document the multiple ways in which Black children’s innocence is, from birth, threatened by the inevitable imposition of “worldly concerns,” namely the realities of systemic racial inequity, economic stratification, and racist violence. Phillips (2013) points to several examples from the Children’s Numbers in which “the juxtaposition of the romantic child image to the textual violence of the Crisis’s reports” conjures the racist dangers that will inevitably confront these children, “insist[ing] that childhood is not exempt from race prejudice and should not be excluded from race consciousness” (p. 594).

According to Bernstein (2011), following the Civil War, “pain functioned as a wedge that split childhood innocence, as a cultural formation, into distinct black and white trajectories. White children became constructed as tender angels while black children were libeled as unfeeling, noninnocent nonchildren” (p. 33). Pain, therefore, becomes a kind of hermeneutic for reading and a signifier of innocence, and its lack is a lack of innocence. Popular imagery of Black children in the Jim Crow era depicted these children “outdoors” (and thus outside of domestic spaces) “merrily accepting (even inviting) violence” (ibid., p. 34). Most often, this threat of violence came from animals, equating Black children with other beings incapable of innocence and culture. Although, Bernstein writes, the Black children in these images “might quake in exaggerated fear” at the dangers to which they are exposed, “they never experience or express pain or sustain wounds in any remotely realistic way” (ibid.).

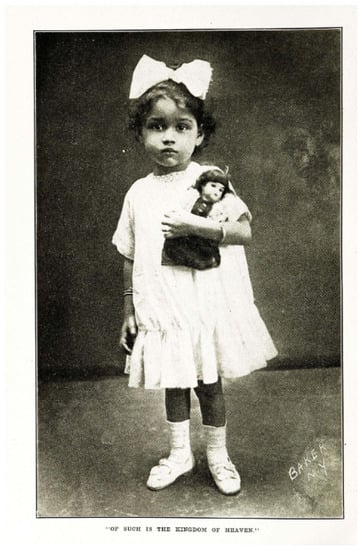

The Children’s Numbers most explicitly confront this racist visual vocabulary by drawing on the inherent collage aesthetic of the magazine form, placing images of posed Black children beside reports of lynchings, a rampantly racist criminal justice system, and other forms of racial prejudice and violence. Augusta Bird’s ironically titled story, “Race Purity,” which appeared in the 1918 Children’s Number, directly addresses the violence of the color line in particular. Framed by two photographs of children—a visibly Black boy and an ambiguously raced girl—the narrative unfolds in a hybrid style of newspaper reporting and short fiction worldbuilding, beginning “Out in the suburbs of the southern town of C—, in front of a low frame house, two children played upon the curb” (Bird 1918, p. 275) (Figure 6). The girl, Annie, threatens the boy, Jimmy, with a worm she has discovered on the ground. The story confronts both the racial grammar of images and the literary convention of Black dialect by depicting Annie as a “little flaxen haired girl” and racializing Jimmy through his speech—“if yo’ put that wo’m on me I’ll smack yo’,” he says (ibid.). The girl throws the worm at the boy, who follows through with his threat: “[h]e wheeled suddenly around and struck the child a full blow on the cheek” (ibid.). A white man “interfere[s],” hitting Jimmy “fiercely” and berating him with a racial slur before redressing Annie “in a softer tone” for playing with a Black child (ibid.). The story concludes with “the startled little girl” telling the man “through her tears” that the boy is indeed her brother (ibid.). This story draws upon “the innocent, vulnerable, sentimental child, a counter to the racist image of the pickaninny” even before the white man appears, as the children, in distinctively infantile ways, cause each other pain (Taylor 2020, p. 739). However, this version of childhood pain—portrayed as the innocent and ultimately harmless pain that accompanies socialization—stands in stark contrast to the pain that the white man imposes by wielding the color line as a socially divisive tool, one that divides him from them but one that also categorizes and separates the two children from each other based on their phenotypic appearances. The images that accompany this story also address the quandary of racial categorization by subverting “the truth and legibility of the photographic image” in demonstrating “racial difference” (Taylor 2020, p. 746). The photographs that frame “Race Purity” feature two children staring blankly into the camera; the feminine child has an ambiguous grin, and the male child looks straight ahead with mouth slightly open and head tilted to one side. The photos are cropped to show only the heads and shoulders of the children, centralizing their facial expressions as they gaze with unclear attitudes into the camera. The affect of these children is, in Taylor’s words, “malleable,” suggesting “the potentiality of the child’s body as a means of imagining a performative racial identity in which binary categorizations are destabilized” (Taylor 2020, p. 770). Further troubling the indexicality of these photos are the proportions of the children’s heads relative to each other and to the frames of the images: the girl appears to have been photographed at a closer angle, and consequently, her head appears larger than the boy’s, mirroring the story’s moral that appearances can be deceiving. That the story never flinches from describing the pain that the children endure and that so few of the images in The Crisis do visibly depict such pain attests to the differing dimensions of the magazine’s visual and discursive rhetorics and the ends that the editors of the magazine felt these different forms could achieve.

Figure 6.

The Crisis 16.6, p. 275, The Modernist Journals Project. https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr511495/, (accessed on 17 January 2022).

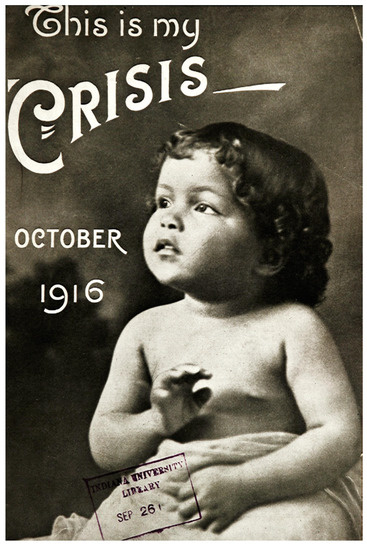

In turning our attention to the images of children in The Crisis, we may, as twenty-first-century viewers, find these images of children to look curiously serious. Perhaps here we come up against our own construction of childhood, in which we expect children to be happy and carefree. To show Black children in such a state of joy and oblivion would run the risk of reinforcing a racist imaginary of Black simplicity. The editors’ choice to instead include images of Black children posed and looking clean, well dressed, composed, and often serious demonstrates that these images of children did the work that, as Amy Helene Kirschke (2014) writes, much art in The Crisis intended to do, to show Black life “from a black perspective,” a perspective that is “dignified and respectful and exude[s] race pride” (p. 86). These images also show that Black children are both capable of and open to pain. For example, on the cover of the 1916 Children’s Number, a child of ambiguous gender stares pensively out of the left-hand side of the frame, not out at the viewer; this pose plays up the child’s dignity and consciousness (Figure 7). In many ways, this image recalls two of Caravaggio’s paintings of Christ (Figure 8 and Figure 9). In these images, Christ’s flowing hair points the eye down towards his hand, which is turned up in a gesture that is gentle, guiding, teacherly. In the Crisis cover image, the child’s hand gesture has a similar quality of gentleness and, in Du Bois’ words, “mighty softness” (Du Bois 1916, p. 268). Caravaggio’s Christ evokes qualities both feminine and masculine: a moral teacher whose human vulnerability allows him to act as a nurturer, leader, and eventually a martyr. That the child on the cover of The Crisis is partially nude also suggests such vulnerability.

Figure 7.

Addison N. Scurlock (1916), cover photograph, Crisis, October 1916. The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/, (accessed on 4 December 2018).

Figure 8.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus of (Caravaggio 1601). The National Gallery, London online, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/michelangelo-merisi-da-caravaggio-the-supper-at-emmaus, (accessed on 31 May 2022).

Figure 9.

Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus of (Caravaggio 1606). The Pinacoteca di Brera online, https://pinacotecabrera.org/en/collezione-online/opere/supper-at-emmaus/, (accessed on 31 May 2022).

4. Narrativizing Black Childhood, Centering Black Motherhood: Johnson’s Maternal Ballads

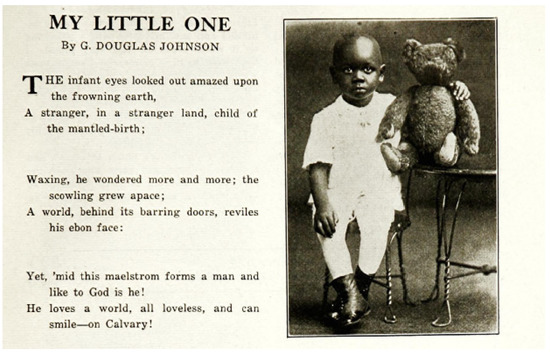

As Bernstein’s history of racialized notions of childhood points out, Black images of childhood that sought to undermine racist depictions of Black children had to carefully navigate affective constraints. Johnson’s “My Little One,” which first appeared in the 1916 Children’s Number, moves across a number of affective registers and notably ends in a spirit of ironic optimism. In Johnson’s short ballad, the poem’s speaker observes an African American child’s gaze and constructs a narrative of the future racial oppression that the child will and must endure. Despite the cruelty of the world, the child morally overcomes the hatred that he faces and ascends to a Christlike position of peace and love for the “loveless” world (Johnson 1916, p. 273). In the October 1916 issue of The Crisis, Johnson’s poem is juxtaposed with another image of Black childhood, this time with a piece of distinctly American iconography, the teddy bear (Figure 10). The subject of the photo stares straight out of the frame and at the audience. It is an eerie image: the child’s hand on the bear’s shoulder suggests a tenuous connection to this symbol of childhood comfort and fantasy.7 Johnson’s poem precisely hones its vision on this fraught relationship between Black childhood and the American cultural imaginary of youth:

- The infant eyes looked out amazed upon the frowning earth,

- A stranger, in a stranger land, child of the mantled-birth;

- Waxing, he wondered more and more; the scowling grew apace;

- A world, behind its barring doors, reviles his ebon face;

- Yet, ‘mid this maelstrom forms a man and like to God is he!

- He loves a world, all loveless, and can smile—on Calvary!

(Johnson 1916, p. 273)

Figure 10.

Johnson’s “My Little One” from the 1916 Children’s Number beside a photograph of a child with a teddy bear, a photo most likely submitted by the child’s mother. The Crisis 12.6, p. 273, The Modernist Journals Project, https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/, (accessed on 4 December 2018).

Further reinforcing the parallelism of the cover image with depictions of Christ, this poem imagines the future of an African American child who learns to love the “loveless” world (ibid.). Johnson’s infant subject appears Christlike in many ways: his ability to “turn the other cheek” and meet hatred and violence with love and understanding; his suffering as a martyr; and the “mantle” of his birth (ibid.). The mantle was a resonant symbol of Blackness for Johnson; this mantle is equal parts veil that separates one from the world and an inherited responsibility to one’s people. The mantle, then, resembles the most potent symbol of Christ’s ontological in-betweenness, the cross, which both connects Christ to his own bodily and human qualities and propels him to his destiny at the Godhead. Like many works of Harlem Renaissance art and literature, Johnson’s poem connects the struggles of African Americans to achieve the emancipation of the Biblical narrative of the Israelites, with one slight but important change: the child of “My Little One” is “a stranger in a stranger land” (Johnson 1916, p. 273, my italics). The earth itself in this poem is transformed into a “frowning” landscape that is as alienated from white society as is the Black child (ibid.). “Earth” and “world” are at odds: the infant’s story begins with a visual connection with the “Earth,” but his vision is barred to the “scowling” “world,” the white world that “reviles” the child’s “ebon face” (ibid.).

The action of this poem is generated from the inevitably that, unlike white children who can remain in Bernstein’s words “oblivious to worldly concerns” (Bernstein 2011, p. 4), the circumstances of racial prejudice are waiting to spoil the innocence and childlike amazement of the poem’s subject. In many ways, Johnson’s poem mobilizes the representational politics espoused by Du Bois: the child that is the poem’s subject is more an archetype than an individual. However, two qualities of the poem complicate the racial uplift politics of representation. First, the title “My Little One” individualizes the child by connecting him, against Du Bois’ desires in his editorial of 1916, to his mother. One way we might read this poem is a lyrical moment of speculation by Johnson about her child’s future as she observes his curious gaze. Johnson also offers a narrative of childhood education that differs in slight but important ways from that put forth by Du Bois. Johnson culls from the ballad tradition and crafts a poem with a narrative that progresses in each stanza: the first stanza offers something like inciting action, the infant’s “mantled-birth” foretelling a life vexed by racist hatred (Johnson 1916, p. 273). Still, the phrase that describes the child retains the kind of dignity and intellectual curiosity that mark the photos of the children in this issue: that he “looks out” suggests a domestic setting and the infant, like the child on the cover photo, gazes pensively to the world outside (Johnson 1916, p. 273). The second stanza conflates the child’s bodily and intellectual growth: “Waxing, he wondered more and more” (ibid.). Although the child seems to remain literally sheltered in this stanza, the final stanza depicts the child’s growth into adulthood “’mid this maelstrom” (ibid.). Whereas Du Bois fears openly that children may learn the realities of race prejudice too soon, Johnson’s infant is molded into a man with the loving and forgiving capabilities of Christ through the painful experience of living with racial oppression. For Du Bois, the innocence of Black infants lies in their ignorance of “the shadow [and] thought of a color line” (Du Bois 1912, p. 287), but Johnson’s poem powerfully, through an image of segregation, challenges the construction of innocence as ignorance. For Johnson, the infant’s curious gaze has already opened him onto the world of “the frowning earth” and its “barring doors” (Johnson 1916, p. 273).

A slightly modified version of this poem appears in Johnson’s 1922 book of poems, Bronze, which opens with an “Author’s Note” that sees her poetry through the lens of Black childhood and contains notable parallels to “My Little One”: “This book is the child of a bitter earth-wound,” Johnson writes, which reflects the “frowning earth” of “My Little One” (Johnson 1922a, p. 3). Like “My Little One,” this author’s note is future-looking, anticipating a coming day in which the wounds of racial oppression are healed: “I know that God’s sun shall one day shine upon a perfected and unhampered people” (ibid.). Still, both texts remain marked by the precarity of the positions of both child and mother. When she published the poem in Bronze, Johnson changed the title and in doing so altered the position of motherhood in this poem: the poem’s new title, “’One of the Least of These, My Little One,’” is an allusion to the New Testament parable known as “The Sheep and the Goats” (Johnson 1922a, p. 44). Christ, in this parable, says that God will invite “the sheep,” those who are righteous, to sit at his right hand because what they did “unto one of the least of these my brethren,” they “have done it unto me” (Matthew 25:40 (King James Version)). Then, God casts those on his left side into Hell for precisely the same reason. This Biblical reference makes a number of interpretations possible. We could read the child of the poem as even more clearly representational, as a metonym for African Americans more generally, the least fortunate of God’s children on Earth. The poem, in this sense, warns white people of the consequences of their actions in the afterlife. However, it is worthy of note that this poem appears in a section of Johnson’s book titled “Motherhood.” If we read the child as both “One of the Least of These” and “My Little One,” the poem becomes a celebration of Black motherhood, if an emotionally complex one.

Johnson’s poems also speak back to the portrait style so common amongst the photographs of children in The Crisis; whereas these photographs and their configuration in large clusters erase the mother from these images, much as Du Bois enacts in his editorial of 1916, Johnson’s poems of Black motherhood draw explicit attention to the mother’s perspective as seer and speaker. Rather than simply “portraits” of the Black male child, these poems offer a narrative of childhood development that centers the mother’s emotional experience of her child’s life, making space for memory, projection, and even sensual and sexual pleasure. Johnson’s “The Mother,” published first in the 1917 Children’s Number and again, in altered form, in the “Motherhood” section of Bronze, offers a more interior vision of the mother’s experience as she gazes upon her infant child and imagines his future. “The Mother” also features one of the most interesting revisions that Johnson undertook for her poems. In similar fashion to “My Little One,” Johnson structures the poem in three stanzas that, though they take place in the time of a singular, lyrical moment of reflection, progress narratively from the look of a mother as “she soothes her Mantled child” to the movement of her thoughts as they “[leap] down the years” (Johnson 1917, p. 293). However, whereas “My Little One” ended on a note of compromised optimism, “The Mother” concludes on a note of prospective mourning: “God alone will ever know/The acme of her utter woe!” (ibid.). The source of this anxiety and despair is, as in “My Little One,” the treacherous world outside the home: “Her heart is sandling his feet/Adown the worlds [sic] corroding street” (ibid.). While Johnson typically made slight adjustments to her poems between publication in magazines and in her books, these changes are typically more superficial than substantive, dealing with punctation primarily. However, Johnson made a relatively radical revision to “The Mother” before publishing it in Bronze: whereas in the Crisis version of the poem, the first two lines read “The mother soothes her Mantled child/With plaintive melody, and wild” (ibid.), in the version that appeared in Bronze Johnson transforms the mother’s “plaintive melody” to an “incantation sad and wild” (Johnson 1922a, p. 41). In changing the mother’s song into a prayer, or perhaps even a magic spell, Johnson shifts the tone of the poem from the strictly domestic to the romantic and mystical, more akin to the tone of her earlier lyrics in The Heart of a Woman, and further associates the act of mothering with the work of making poetry.

Johnson returns to a mystical and incantatory version of motherly love in “Shall I Say, ‘My Son, You’re Branded’?” This poem confronts the very concern that Du Bois voices in his editorials regarding how and when to educate children in the racial prejudice that will inevitably plague them in life. Johnson’s poem imagines, through an act of foresight similar to that displayed by the speakers of “My Little One” and “The Mother,” the future of her child, embracing the role of seer: “Or shall I, with love prophetic, bid you dauntlessly arise, /Spurn the handicap that clogs you, taking what the world denies, /Bid you storm the sullen fortress wrought by prejudice and wrong / With a faith that shall not falter, in your heart and on your tongue!” (Johnson 1922a, p. 45). Rhetorically imagined as the vessel of the mother, the child becomes a romantic hero figure in this image, and yet, one who “is not born but made” (Taylor 2020, p. 754). In these prophetic poems, Johnson depicts the mother’s role as maker in many senses of the word: as artist, storyteller, educator, eulogist, and historiographer.

These poems also evoke a domestic space of many competing affective values; as the space in which the mother makes her art, it provokes creativity, strong feelings of safety and sensual pleasure, and contemplation. At the same time, as a social sphere, it confines—as in Johnson’s most famous poem “The Heart of a Woman,” in which the woman’s heart “breaks on the sheltering bars” of its cage (Johnson 1918, p. 1)—even as it shelters like a nest. Johnson’s “My Boy,” published in both The Crisis and Bronze, serves as a companion to “Heart”. In this poem, the speaker–mother listens to her son “singing happily,” another event that incites the mother’s prophetic imagination: “A thousand javelins of pain/Assault my heaving breast/When I behold the storm of years/That beat without your nest” (Johnson 1922a, p. 46). The imagery of these lines certainly recalls that of “Heart” and of the larger project of Johnson’s first book of poems, wherein “Johnson associates a woman’s heart with the traditional image of the poetic imagination” (Tate 1997, p. 1). In addition to affirming her son’s purity, “innocence serene,” and joy, the speaker of “My Boy” aligns his song “[o]f joyous rhapsody” with the work of poetry. In bidding him to sing his “matin song … [b]efore it melts in tears,” and in associating her child with a songbird, the poem portrays the male child as holding a dangerous kind of freedom denied the speaker–mother. Whereas the burden of the woman is to live constrained by the cage of domesticity, the world outside the nest is a different kind of prison for her son. However, childhood for the Black mother and her son represents a precious time of song and poetry, a shared experience in which they can revel together in the pleasure of the lyric arts. The poem further connects this aesthetic pleasure-taking with “love … as a metaphysical eroticism” that serves as a “means for transcending one’s human limitations and experiencing the sublime” (Tate 1997, p. lvii): the speaker pleads for her son to sing in order to “[d]istil [sic] the sweetness of the hours / In gladsome ecstasy” (Johnson 1922a, p. 46).

In her 2015 essay “The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning,” Claudia Rankine (2015) writes that she “asked [a] friend what it’s like being the mother of a black son. ‘The condition of black life is one of mourning,’ she said bluntly. For her, mourning lived in real time inside her and her son’s reality…. Though the white liberal imagination likes to feel temporarily bad about black suffering, there really is no mode of empathy that can replicate the daily strain of knowing that as a black person you can be killed for simply being black.” In light of Rankine’s words, Johnson’s poems of motherhood articulate complex acts of mourning. The final image of “My Little One,” Calvary, the site of Christ’s crucifixion and (human) death, evokes reverence and grief in a singular image. More specifically, the final image of the poem shows the child “smiling on Calvary,” perhaps from above it in Heaven. This evocation of the site of Christ’s torture reaffirms, finally, the anguish, pain, and sorrow that Black children and mothers must endure, a pain made worse by the fact that this pain is denied by the white world. For a moment of lyrical time and space, Johnson’s motherhood poems proactively brave the task of this mourning, rewriting the painful experiences of Black motherhood and childhood into acts of profound love and heroism.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Linda Kinnahan and Kathy Glass for their generous guidance, sage mentorship, and warm encouragement while working on this essay and over the years (nearly a decade and counting). Many thanks, also, to the brilliant students from Kinnahan’s Fall 2021 “Modernist American Poetry & Visual Culture” course at Duquesne, with whom I had the pleasure of sharing many invigorating discussions about Harlem Renaissance poetry and visual art that sparked more than a few ideas represented here. Finally, special thanks to Marla Anzalone, Kelly Svoboda, Josie Rush, Rochel Gasson, and Caitlyn Hunter, all of whom contributed a wealth of ideas, insights, and kind words while reading various versions of this essay (not to mention while loitering outside the doors of College Hall). All images reproduced herein are in the public domain.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In 1920 and 1921, Du Bois and the editorial staff of The Crisis elected, in lieu of publishing Children’s Numbers of The Crisis, to instead dedicate a new magazine to children and adolescents, the Brownies’ Book, a decision I will discuss at greater length below. |

| 2 | Claudia Tate (1997) writes that Johnson’s critics have seen her “as a traditionalist and an advocate of genteel culture who adhered to the Romantic conventions of the nineteenth-century Anglo-literary establishment” (p. xviii). |

| 3 | Taylor (2020) asserts that the Children’s Numbers preferred the studio portrait style because “the vulnerability and innocence of black children could be articulated more effectively through recourse to the visual language of (white, middle-class) sentimentalism than through more direct or documentary portrayals of black suffering,” particularly because minstrel imagery relied so often on the pain (or, more accurately, bodily harm) of Black children for humorous ends (pp. 760, 755). |

| 4 | Notably, these issues set clear boundaries on childhood at birth and pre-pubescent life, though Du Bois would identify the audience of The Brownies Book as children ages “Six [to] Sixteen” (The Crisis 1919, p. 286). Few images appear to show pre-teens, teenagers, or young adults. In setting childhood apart from adolescence, these issues skirt the problem of sex and sexuality. As such, childhood is defined, in the editorial team’s eyes, by the innocence that comes before sex. Black childhood is, therefore, also privileged ground for undermining the pictorial and discursive representation of blackness as a site of primitive sexual aggression that threatens civilized life. By the same token, however, the Children’s Numbers reinforce sex as an act that opens one up to sin, reflecting the conspicuous Christianity of many poems and images in The Crisis. |

| 5 | Johnson wrote these words in response to a questionnaire circulated by The Crisis in 1926, which the editors composed in order to gather the thoughts of multiple early twentieth-century writers and thinkers on the question of Black representation. The magazine then published these answers in a symposium entitled “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed.”. |

| 6 | It is in response to this double bind, Du Bois writes, that the editors will put together “an entirely separate publication, a little magazine for children,” The Brownie’s Book (Du Bois 1919, p. 286). Du Bois suggests that a difference of form (from a “record of the darker races” to a “little magazine for children,” from a candid to a guarded conversational style) is necessary for the education of African American children. |

| 7 | In the 1914 edition of the Children’s Numbers, The Crisis makes similar ironic use of the teddy bear while recounting the story of “a little boy of four and a half years held on the charge of burglary and larceny” for stealing a pair of shoes (The Crisis 1914, pp. 292–93). The article, which reports on the “contrasting conditions” of “colored and white Juvenile Courts” in America, concludes the story of the boy (“Gainer … a little waif, without father or mother”) “hugging a Teddy bear while he waited for his sentence” (ibid.). |

References

- Bernstein, Robin. 2011. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: New York UP. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, Augusta. 1918. Race Purity. The Crisis 16: 275. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr511495/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da. 1601. Supper at Emmaus. Oil on Canvas. London: The National Gallery, Available online: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/michelangelo-merisi-da-caravaggio-the-supper-at-emmaus (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Caravaggio, Michelangelo Merisi da. 1606. Supper at Emmaus. Oil on Canvas. Milan: Pinacoteca di Brera, Available online: https://pinacotecabrera.org/en/collezione-online/opere/supper-at-emmaus/ (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1912. Editorial. The Crisis 4: 287–91. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr520823/ (accessed on 15 March 2019).

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1916. The Immortal Children. The Crisis 12: 267–68. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/ (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1918. About Pictures. The Crisis 16: 268. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr511495/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1919. The True Brownies. The Crisis 18: 285–86. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr512545/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 1922. Foreword. In Bronze: A Book of Verse. Edited by Georgia Douglas Johnson. Boston: B.J. Brimmer Company, p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. 2006. Criteria of Negro Art. In Double-Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology. Edited by Venetria K. Patton and Maureen Honey. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, pp. 47–51. First published 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Barbara. 2009. Apostrophe, Animation, and Abortion. In Feminisms Redux: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism. Edited by Robyn Warhol-Down and Diane Price Herndl. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, pp. 206–19. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. 1916. My Little One. The Crisis 12: 273. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/ (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. 1917. Poems. The Crisis 14: 293. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510854/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. 1918. The Heart of a Woman and Other Poems. Boston: The Cornhill Company. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. 1922a. Bronze: A Book of Verse. Boston: B.J. Brimmer Company. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. 1922b. Motherhood. The Crisis 24: 265. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr521702/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Johnson, Georgia Douglas. 2007. The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed. In The New Negro: Readings on Race, Representation, and African American Culture, 1892–1938. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Gene Andrew Jarrett. Princeton: Princeton UP, p. 199. First published 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschke, Amy Helene. 2014. Laura Wheeler Waring and the Women Illustrators of the Harlem Renaissance. In Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Edited by Kirschke Jackson. Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford English Dictionary Online. 2022. Knock, v. OED Online, March. Available online: www.oed.com/view/Entry/104090 (accessed on 27 May 2022).

- Phillips, Michelle H. 2013. The Children of Double Consciousness: From The Souls of Black Folk to the Brownies’ Book. PMLA 128: 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkard, Michelle J. 2015. "Don’t Knock at My Door, Little Child": The Mantled Poetics of Georgia Douglas Johnson’s Motherhood Poetry. In The Harlem Renaissance. Edited by Christopher Allen Varlack. Ipswich: Salem Press, pp. 217–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rankine, Claudia. 2015. The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning. The New York Times Magazine, June 22. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/22/magazine/the-condition-of-black-life-is-one-of-mourning.html(accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Renker, Elizabeth. 2018. Realist Poetics in American Culture, 1866–1900. Oxford: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Scurlock, Addison N. 1916. Cover photograph. The Crisis 12. The Modernist Journals Project. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/ (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Smith, Shawn Michelle. 2004. Photography on the Color Line: W.E.B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, Claudia. 1997. Introduction. In The Selected Works of Georgia Douglas Johnson. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Jennifer Burton. New York: G.K. Hall & Co., pp. xvii–lxxx. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Julie. 2020. Mechanical Reproduction: The Photograph and the Child in The Crisis and the Brownies’ Book. Journal of American Studies 54: 737–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Crisis. 1913. 6.6 The Modernist Journals Project. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr517569/ (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- The Crisis. 1914. Juvenile Court. The Crisis 8: 292–93. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr519286/ (accessed on 8 December 2019).

- The Crisis. 1915. 10.6. The Modernist Journals Project. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr508260/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- The Crisis. 1916. 12.6. The Modernist Journals Project. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510140/ (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- The Crisis. 1917. 14.6. The Modernist Journals Project. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr510854/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- The Crisis. 1919. 18.6. The Modernist Journals Project. Available online: https://modjourn.org/issue/bdr512545/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Woodley, Jenny. 2014. Art for Equality: The NAACP’s Cultural Campaign for Civil Rights. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).