Abstract

New Negro magazines such as The Messenger, Opportunity, and The Crisis regularly featured photographs and short descriptions of Black women designed to highlight their role as both moral centers and aspirational figures. These images tended to imply that the ideal New Negro woman would challenge racist stereotypes of Black women not only through her behavior but also through her looks. For instance, a feature in the January 1924 issue of The Messenger called “Exalting Negro Womanhood” seeks to counter the overrepresentation of “[t]he buffoon, the clown, the criminal Negro” in white media with portraits of Black “achievement, culture, refinement, beauty, genius, and talent”. But of the twenty women featured in the centerfold of photographs, all are light skinned. Importantly, however, Black women poets of the era, including Gwendolyn B. Bennett, Gladys May Casely-Hayford, Anita Scott Coleman, Jessie Fauset, Angelina Weld Grimké, Helene Johnson, Anne Spencer, and Octavia B. Wynbush, provide a counter to this coding of light skin as desirable through poems that emphasize the beauty of dark-skinned bodies. This essay places their poetry alongside the visuals of the New Negro movement and the larger white supremacist culture of the 1920s. In poems such as Bennett’s “To a Dark Girl”, Grimké’s “The Black Hand”, Johnson’s “Poem”, and Spencer’s “Lady, Lady”, an emphasis on beautiful and powerful Blackness provides a steady counterpoint to the prevailing color standards surrounding Black female beauty and respectability.

1. “To Show, in Pictures as Well as Writing”: Introduction

In January 1924, The Messenger announced a new feature, “Exalting Negro Womanhood”, designed “to show, in pictures as well as writing, Negro women who are unique, accomplished, beautiful, intelligent, industrious, talented, successful” (p. 7). Envisioned as a state-by-state catalog1 of such women, the purpose of the feature, the editors explained, was to provide a counterpoint to the kinds of images of Black women and men that commonly appeared in daily (white) newspapers of the time: “[t]he buffoon, the clown, the criminal” (p. 7).2 The January issue featured “A Bouquet of New York Beauties” and “Empire State Emeralds” in a two-page spread of twenty photographs (pp. 22–23) of attractive, middle-class women, most of whom were identified as married women (e.g., “Mrs. Stella D. Nathan”), and all of whom appear to be light skinned. Subsequent issues featured “Cultured Washington Society” (April 1924, pp. 114–15), “Society Leaders of Richmond, VA” (May 1924, pp. 152–53) and pages dedicated to women from Baltimore (June 1924, p. 170), California (July 1924, pp. 216–17), Delaware, and Chicago (August 1924, pp. 243, 248). The design of the photo spreads varies: some feature full-body poses, and others focus on the women’s faces; some are round while others are rectangles; some pages have ornately designed backgrounds while others are more simply formatted; some captions provide professional or family backgrounds for the women, others simply give their names (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

“Exalting Negro Womanhood”. The Messenger, January 1924, p. 22. Accessible online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/inu.32000004071702 (accessed on 16 August 2022).

This feature, which continued to appear off and on through 1928, speaks to the New Negro periodicals’ approach to the visual representation of Black women. As the historian Paula C. Austin demonstrated, “[t]he visual was an important register for argumentation” in New Negro periodicals, a way for the magazines to “engage in an aspirational politics” and to challenge racist attitudes (Austin 2018, p. 313). As I will discuss, these images and others that appeared on the covers and in the pages of The Messenger, The Crisis, and Opportunity, as illustrations for editorial content and advertisements, present African American women as young, accomplished, and restrained, and frequently center light-skinned women as beautiful and desirable. These images were designed to “refut[e] commonplace notions of black inferiority … position[ing] black subjects instead as evidence of cultural production, political sophistication, respectability, and virtue” (Austin 2018, p. 319). At the same time, however, these magazines feature poetry by African American women that serves as a sort of counter discourse about Black womanhood. Overtly in some cases and implicitly in others, African American women’s poems in these periodicals find beauty in “unskilled” labor and in aged or physically worn bodies, they affirm physical strength and desire as attractive and valuable in their own right, and they shift readers’ attention away from the visual as the dominant arbiter of value. While there have been excellent studies of the visual dimensions of the Harlem Renaissance, including Miriam Thaggert’s (2010) Images of Black Modernism and Charlene Sherrard-Johnson’s (2007) Portraits of the New Negro Woman, those studies have tended to focus mostly on fiction’s intersection with visual culture. Yet poetry, particularly poems by women writers of the movement, forms a significant counter discourse to the colorism and classism of the visuals. Both in terms of how African American readers see themselves represented and how white readers picture African Americans, the poets and editors are united in their efforts to shift representations of Blackness; however, their diverging methods to change perceptions of Black women reflect conflicting concepts of beauty and sexuality, labor, and maternity within the New Negro movement and push for an alternative to the visual economy of race and gender.

2. “Seeing Is Believing”: New Negro Visuals

The Crisis, Opportunity, and The Messenger sought to reach similar audiences—Black, middle-class readers invested in racial uplift—and worked to “depict Negro life as it is with no exaggerations”, as Eugene Kinkle Jones, the Urban League’s chief executive officer, wrote in the inaugural issue of Opportunity in 1923 (qtd. in Wilson 1999, p. xviii).3 In The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White, George Hutchinson explains that these magazines were “broadly interdisciplinary—concerned with new developments in anthropology, social theory, literary criticism, and political commentary” and that “the general social and cultural orientation of the magazines shaped the production and the reading of all that appeared in each issue as well as largely determining the likely audience” (Hutchinson 1995, p. 127). In addition to these journalistic elements, these magazines regularly featured creative writing as a demonstration of the aesthetic prowess of Black authors. Considering the visual culture of these publications, including both editorial and advertising content, is critical to understanding how the poetry that appeared in their pages was presented and received. Leafing through an issue of any of these magazines would have meant encountering text, photographs and drawings, and advertisements, with no clear hierarchy among the elements.4 Donal Harris’s argument about The Crisis is broadly applicable to all these magazines: “The target audience is explicitly raced, and its cover art and editorial context repeatedly drew attention to the implicit whiteness of popular print culture” (Harris 2016, pp. 68–69). Bartholomew Brinkman further notes that any poems appearing in the magazines must be read in the context of “their participation in the larger racial discourse of the magazine[s]” (Brinkman 2020, p. 74). Suzanne W. Churchill points out that these magazines “fostered a sense of community among African American writers” and passed that sense of belonging on to readers as well (Churchill 2016, p. 179).

These periodicals built “ongoing narrative through [their] monthly issues, exposing the brutality of early-twentieth-century American racism while extolling the economic, political, and intellectual achievements of a wide range of Black citizens” (Young 2022, p. 298). They were inherently political, “focused simultaneously on documenting racial injustice … and on racial uplift” (Young 2022, p. 295). Features such as The Messenger’s “Exalting Negro Womanhood” foregrounded Black excellence as a counterpoint to the reports of racialized violence and discrimination documented in the magazines’ pages. Yet, these images rely on a fairly narrow set of visual conventions to signal that excellence. Emphasizing what Nina Miller describes as “beautiful, genteel femininity” (Miller 1999, p. 152), the photographs generally show African American women in modern, fashionable clothing and hairstyles, usually from the shoulders up, and they often look demurely away from the viewer. In many cases, the images appear with little to no text about the women themselves: the visual information is, for all intents and purposes, presented as sufficient. For instance, women might be identified by their achievements, as was the graduate on the cover of the July 1924 issue of The Crisis, identified only as “A Master of Arts, University of California”. She wears her cap and gown and looks over her left shoulder, her gaze just past the viewer’s right side; her hair is straightened and cut in a bob, and she holds a rolled diploma in her lap. In other cases, a subject’s name might be provided, as with the photograph on the cover of the September 1924 issue of The Messenger, “Miss L. Jones, Chicago IL”. Miss Jones looks directly at the viewer, smiling enough to reveal straight, white teeth; her hair is also straight and either short or pulled back, and she wears a dark blouse. African American readers are encouraged to imagine themselves (or their daughters or sisters) as “A Master of Arts” or to aspire to the trappings of genteel femininity the women demonstrate. Features such as Opportunity’s “Bulletin Board” regularly ran photographs of accomplished Black women and men alongside short descriptions of their achievements. For instance, the November 1924 “Bulletin Board” features a photograph of Georgia Caldwell, who looks directly at the viewer. She wears a white dress and is seated alongside a trophy. The accompanying paragraph notes that she is “the youngest student ever to enroll at Kansas University” and the recipient of “the Alumni Silver Loving Cup, given for highest scholarship” (p. 351). Caroline Goeser theorizes that the lack of substantive biographical detail about the women in these images ensures these women’s status as both “representative types” and as “proof … that real African American women had successfully entered the fray of American education, commerce, and beauty culture” (Goeser 2007, pp. 64–65). The suppression of individualizing information also suggests an unquestioning faith in the photographs to eclipse the caricatured images pervading the Jim Crow United States. Given that these photos, along with those from The Messenger and The Crisis described above, share space in the magazines with advertisements for various colleges and training institutions, it is clear that part of their work is to promote a visual narrative of Black educational excellence and the so-called “talented tenth”.

But even as these visuals regularly featured Black women’s accomplishments, the magazines also bear signs that Black women’s access to the world of bourgeois comfort was likely to be mediated in various ways. As Jessie Redmon Fauset wrote in a brief article that appeared in The World Tomorrow in March 1922, African American women were subject to a white gaze that always found them lacking. “Either we are aesthetic or we are picturesque and always the inference is implied that we live with one eye on the attitude of the white world as though it were the audience and we the players whose hope and design is to please” (Fauset 1922, p. 76). While the New Negro magazines were, in part, an effort to escape from and challenge that white gaze, there is ample evidence in their pages that white aesthetic judgment remained a powerful force. Advertisements for women’s beauty products were steady reminders to African American women that “light brown skin and ‘silken hair’ amounted to ‘alluring perfection’” (Goeser 2007, p. 97). Black beauty entrepreneur Madame C. J. Walker and her products are a prime example of these attitudes. Advertisements for her products in the pages of The Messenger promise, “If ugly, they will make you pretty. If pretty, they will make you more so” (October 1924, pp. 308–9). The illustrations make clear what “pretty” means. Fashionable young women, wearing slips and bathing costumes, are pictured on either side of the text in the two-page spread, while the accompanying text reminds consumers that “your chief relations [with other people] are those of sight” and “Seeing is believing”. The women at the beach are depicted beneath a large umbrella, suggesting that their light skin (presumably thanks to Walker’s creams) requires special protection from the sun (Figure 2). Essentially, Walker’s advertisements served as reminders to African American women of the premium placed on looks, especially those considered “aesthetic”, in Fauset’s formulation.5 As Irene Tucker notes in her discussion of racial signifiers, “[t]he curious signifying trio of hair, skin, and bone” become “the material forms racial signs take” (Tucker 2012, p. 6), so it is unsurprising that products promising to alter these signifiers, and thus to shift the terms of the encounter between onlookers and subjects, would appeal to some consumers.

Figure 2.

“From Boudoir to Beach”, The Messenger, October 1924, pp. 308–9.

Other advertisements in these magazines underscored this visual pressure, suggesting that African American success—whether in education and career or marriage and family—was yoked to compliance with white beauty standards. Paula C. Austin tells us that “‘Beauty’ was central to New Negro femininity, emphasized as an integral demonstration of black womanhood” (Austin 2018, p. 327).6 Whether for life insurance, banking services, or foot cream, advertisements in these magazines featured drawings of attractive and seemingly leisured light-skinned Black women. As with the articles and illustrations, the advertisements position African American women as “model[s] of service, propriety, and moral character” and feature women who are, “more often than not, light-skinned” (Sherrard-Johnson 2007, p. 25). These women—“teachers, socialites, and madonnas”, in Cherene Sherrard-Johnson’s summation (Sherrard-Johnson 2007, p. 123)—signal their middle-class status through their clothing and pastimes. The advertisements frequently link these women to beauty and carefree existence via their slogans: “Sitting Pretty” for Underwriters; “Perfect Comfort” for Perkins Foot Cream; “Rose Buds Themselves” and “Beauty’s Synonym” for Walker’s products, each featuring fashionably dressed and coiffed women whose postures suggest lives of relative ease. A reader paging through one of these magazines could easily imagine aspirational timelines wherein promising young women go from colleges to careers to families of their own, always lovely and always working toward self and community improvement. Austin notes that “[w]ith only slight variations on a theme, [these publications] presented respectable black women as upholders of morality within the black family, whether that family was represented by middle-class trappings … or through their participation in [racial uplift programs]” (Austin 2018, p. 313). As such, the images establish a new set of aspirational stereotypes, in which participation in these programs and beauty standards are the only, or at least the best, routes to socioeconomic success.

Some illustrators’ work challenges, implicitly or explicitly, these conventions. Of particular note are Gwendolyn Bennett’s magazine covers. Bennett, whose poetry is discussed below, contributed covers to The Crisis and Opportunity starting in 1923. As Belinda Wheeler argues, Bennett’s illustrations, particularly several Christmas-themed covers which appeared between 1923 and 1930, “promot[e] community between diverse groups … supporting unity between races, genders, and ages” (Wheeler 2015, p. 209). Her best-known image was created for the cover of Opportunity in July 1926. It features a young woman with recognizably Black features and short curly hair wearing a fashionable evening dress who appears to be dancing (Figure 3). Behind her, we see a horizontal frieze in the Art Deco style depicting the silhouettes of three dancing women, stylized palm trees, and a setting sun. The dancers’ hairstyles echo that of the woman in the foreground, but their setting and clothing (or lack thereof) invoke Africa.7 Goeser points out that this image, along with several other visuals created by African American artists, presents the modern Black woman not as beholden to white aesthetics but rather as embracing Black ones in “a dramatic departure from stereotypical assumptions that youth, beauty, and modernity remained the exclusive rights of white women” that Black women could only attempt to copy (Goeser 2007, p. 194). Bennett’s images and poetry argue for “the beauty in diversity … by honoring dark-skinned and light-skinned individuals” (Wheeler 2015, p. 211). Yet, they do so in a larger context of periodicals whose visuals emphasize respectability politics as the route to liberation.8

Figure 3.

Gwendolyn Bennett, cover illustration, Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life, July 1926. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, New York Public Library. Accessible online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/99911ba0-39dc-0131-202e-58d385a7b928 (accessed on 5 August 2022).

The dominant images of bourgeois African American women in the pages of The Messenger, The Crisis, and Opportunity seek entry into this visual economy by showcasing figures who are recognizable as participating “correctly” in American life—earning degrees, participating in community events, dressing fashionably. But this approach is ultimately complicit in the very structures of oppression in its reliance on the visual as the arbiter of value, on a certain kind of visibility as the goal. This faith that the photographs and other visuals would serve as successful representations to both Black and white readers hinges on the belief that seeing is believing and that photographs such as that of “Miss L. Jones” could eclipse the ubiquitous caricatures of Black women. The visual dimensions of this argument are critical since, as Robyn Wiegman argued, “every subject in U.S. culture [is situated] within the panoptic vision of racial meanings”, in which the visual is “both an economic system and a representational economy” (Wiegman 1995, pp. 4, 40). Where racist caricatures and negative news reports sought to dehumanize African Americans for white readers’ and consumers’ satisfaction, images in New Negro periodicals were intended to “define a visual group identity” that ran counter to white supremacist narratives. They were also intended to help “construct and visualize a black middle class”, as Deborah Willis explains in “Picturing the New Negro Woman” (Willis 2008, p. 228). Of course, the demand to offer proof comes from the regime of white supremacy, despite the fact that white supremacists are likely to ignore the facts.9 As the editors of The Messenger point out, images of African Americans as “[t]he buffoon, the clown, the criminal” circulated in white-owned and operated media alongside advertising images such as that of Aunt Jemima, “mass-produced images that reinforced widely held stereotypes that sought to diminish the humanity of African Americans” (Willis 2008, p. 228). Harlem Renaissance magazines sought to provide a counterpoint to those images, shaping viewers’ experiences of Black women away from those circulating stereotypes. Both the racist and “exalted” visuals provide what Hannah Walser, in her discussion of advertisements for fugitive slaves, characterizes as “active interventions into the already complex socio-cognitive situation of face-to-face contact between white and black Americans” (Walser 2020, p. 62).

3. “A Most Beautiful Thing”: New Negro Women’s Poetry

Poetry functioned as both supplement and corrective to the visual propaganda on the pages. Poets such as Angelina Weld Grimké, Jessie Fauset, Anita Scott Coleman, Gladys May Casely-Hayford, Anne Spencer, Octavia B. Wynbush, Helene Johnson, and Gwendolyn B. Bennett, all of whom contributed regularly to New Negro magazines and anthologies, demonstrate awareness of these visual conventions while also pointing toward alternative ways of seeing and valuing Blackness outside of white aesthetics. In their poems, they regularly acknowledge the pressure to conform to white standards—of aesthetics, family, and sexuality—while simultaneously offering alternative visions of what Black beauty, maternity, and desire can be. Their preference for traditional poetic forms “reflects in part a determination not to conform even in the slightest manner to hateful stereotypes” (Wall 1995, p. 14); the use of “sophisticated, refined forms such as the sonnet also enabled black women to dissociate themselves from the … stereotype of the simple-minded happy ‘Mammy’” (Churchill 2016, p. 180). But even as they leveraged poetic forms that demonstrate awareness of bourgeois aesthetics, these poets are critical of bourgeois notions of femininity, and their poems suggest other ways of being in the world as African American women and men. These poems find strength in labor, rather than coarseness; they position desire as creative rather than threatening; and they look outside the visual for a sense of value.

Angelina Weld Grimké’s “The Black Finger” first appeared in Opportunity in November 1923 and was republished in Alain Locke’s The New Negro anthology in 1925.10 This brief poem describes “a most beautiful thing”: the image of “A straight, black cypress” silhouetted “Against a gold, gold sky” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 172). Grimké describes the tree as “Sensitive/Exquisite”, metaphorically linking the tree with its sturdy roots and spreading branches to her vision of African American people. Maureen Honey suggests that, because it is “stationary”, the tree can be understood as “partly symbolic of women’s immobility”, but she also points out that trees “stand for quiet endurance, pride, dignity, and aspiration, as well as hardy survival of harsh conditions” (Honey 2008, p. 84). To Honey’s assertions, I would add that Grimké’s poem also envisions the Black female body as capable of acting in the world, even if its impacts are not yet realized. The finger is “Pointing upwards”, and its presence leads to the questions that close the poem: “Why, beautiful, still finger, are you black?/And why are you pointing upwards?” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 172). While these lines leave the questions unanswered, another of Grimké’s poems, “Tenebris”, suggests at least one possibility. In this later poem, published in Countée Cullen’s Caroling Dusk anthology in 1927, another tree appears as “A hand huge and black” silhouetted “Against the white man’s house”. This time, rather than suggesting elegant stillness and control, the tree’s “black hand plucks and plucks/At the bricks” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 174). The house itself is made of “bricks [that] are the color of blood and very small”, and it is dwarfed by the “huge and black” hand “With fingers long and dark”. Grimké’s vision of racial uplift reflects the gradualist rhetoric promoted in the pages of New Negro periodicals—the hand’s work is slow and difficult—while associating that rhetoric explicitly with dark-skinned African Americans by emphasizing that the “Exquisite/… finger” and the “huge” hand are black. Reading these two poems together highlights the ways in which Grimké envisions both physicality and agency for Black women—strongly rooted and capable of enacting change, particularly in response to the bloody violence associated with white supremacy, while maintaining an uplifting vision, “pointing upwards”.

Grimké’s vision offers a subtle corrective to a narrative suggesting that African American progress requires performances of idealized white, bourgeois femininity. African American women, especially mothers, came under special pressure to work for racial uplift and to do so in ways that conformed to white bourgeois expectations. The generation of authors preceding these Harlem Renaissance writers—women such as Pauline Hopkins, Anna Cooper, and Frances E.W. Harper—highlighted Black mothers as carriers of “both the biological and cultural responsibilities of maternity” (Berg 1996, p 138). Cooper, for instance, argued in A Voice from the South (1892) that African American women held the “fundamental agency under God in the regeneration, the retraining of the race as well as the groundwork and starting point of its progress upward” (qtd. in Berg 1996, p. 138). While the race mother is held up as a model of “proper” reproduction, her position as the site at which race and sex converge mean that her sexuality must be policed to maintain her status as “subservient procreator” (Doyle 1994, p. 21). Because white supremacist propaganda regularly relied on the idea of African American men and women as promiscuous, some Black intellectuals—especially men—were uneasy with frank depictions of African American women as sexual beings. Harlem Renaissance publications echo this logic in features such as “Exalting Negro Womanhood” and The Crisis’s various spreads of photographs of babies and children such as those in the annual “Children’s Number”. In both features, specific individuals are presented as ideal “specimens” of achievement: attractive, modern, healthy.

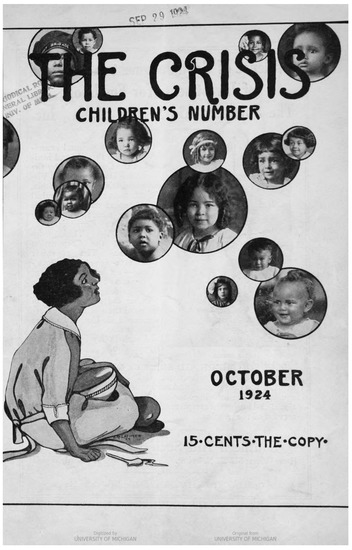

The October 1924 “Children’s Number” of The Crisis promises “Pictures of 100 Colored Babies” in its table of contents and delivers them via photo collages throughout the issue as well as on the cover. Louise Latimer’s cover illustration, “Blowing Bubbles”, features a drawing of a seated light-skinned African American girl with bobbed curls, above whom hovers 17 bubbles, each of which holds a photograph of a Black baby or child (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The Crisis, October 1924.

Other photos of “glowingly healthy, impeccably groomed children” appear throughout the issue, as they do in nearly every October issue of The Crisis during DuBois’s editorship (English 2000, p. 300). The children are well dressed, often in white clothing, and some of the older children are shown with the accouterments of leisure: Ora Anderson of Buffalo sits atop a pony, while Alfred Walker of Baltimore holds a tennis racket (p. 271). While the children’s parents are not included in these photographs, the images imply their presence, particularly mothers, as those responsible for their children’s well-being. “We want all the good clear pictures of healthy human babies that we can get”, DuBois wrote in his editorial soliciting photos for the “Children’s Number” in the September 1924 issue (DuBois 1924, p. 199); those photographs are meant as evidence not only of the future prospects of African Americans but also of the present-day value of the mothers who raise them. These images undergird what Nina Miller characterizes as the endless performance of the bourgeois African American mother, who must repeatedly prove herself to a white supremacist culture that steadfastly denied her very existence (Miller 1999, p. 182).

Three poems—Jessie Fauset’s “Oriflamme”, Anita Scott Coleman’s “Black Baby”, and Gladys May Casely-Hayford’s “Lullaby”—grapple with the impossible position of the Black mother in a culture that routinely denies her status as a “proper” mother. Fauset’s poem, published in The Crisis in January 1920, opens with an epigraph from Sojourner Truth. Truth recalls her “old mammy” looking at the stars and moaning as she thinks of the children taken from her in an era when Black maternity was conscripted to serve white enslavers. Truth recalls her saying, “‘I am groaning to think of my poor children; they do not know where I be and I don’t know where they be. I look up at the stars and they look up at the stars!’” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 234). In her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, Truth famously demanded recognition for Black women as women, to “‘see’ her body according to her own narrative framing” (Brooks 2001, p. 50), a rhetorical strategy these poets also employed to reframe perceptions of Black women. The poem’s title speaks to the idea of a shared vision in that an oriflamme is “an object, principle, or ideal that serves as a rallying point in a struggle” (OED, def. 2). Here, Fauset positions Truth herself as the ideal: “Stricken and seared with slavery’s mortal scars/Reft of her children, lonely, anguished, yet/Still looking at the stars!” (p. 234). The rhyme of “scars” and “stars”, which will be echoed in the poem’s second stanza as “bars” and “stars”, emphasizes the embodied shift Fauset envisions. Truth’s body is a record of slavery’s predations, scarred both physically and emotionally, yet the poem’s speaker looks to her (the poem begins, “I think I see her sitting, bowed and black”) as a source of inspiration and beauty. The second stanza positions Truth as “Symbolic mother” and the poet and readers as her “myriad sons”, “fight[ing] with faces set/Still visioning the stars!” (p. 234). Truth’s Blackness and her motherhood—both symbolic and literal—are her strengths, even as they are also sources of grief in a white supremacist culture that denies that maternity—again, both symbolically and literally.

Anita Scott Coleman’s “Black Baby”, published in Opportunity in February 1929, is a love poem from a mother to her child. Each of its two stanzas opens with a simple declarative sentence: “The baby I hold in my arms is a black baby” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 316). The poem’s speaker goes on to associate the child with two sources of power: soil and coal. “Lo … the rich loam is black like his hands”, Coleman writes, linking the child to fertility and future. While the speaker frets that “I toil, and I cannot always cuddle him”, the infant is resilient, playing happily at her feet, suggesting that a woman can combine work and motherhood successfully. In the second stanza, the speaker highlights coal’s financial and human price (“Costly fuel … /Men must sweat and toil to dig it from the ground” [p. 316]). But the final lines of the poem shift from coal’s challenges to its potential: “If it is buried deep enough and lies hidden long enough/‘Twill no longer be coal but diamonds” (p. 316), once again linking Blackness to value. Blackness in the poem becomes a source of light: “Sunbeams danced on [the baby’s] head” in the first stanza and “His eyes are like coals,/They shine like diamonds” in the poem’s final lines (p. 316). For Coleman, who had four children and also established a children’s boarding home (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 314), both mother and child are creators, capable of recognizing and celebrating beauty in Blackness and linking it to the future in a way that simultaneously resonates with “race mother” rhetoric and challenges its limitations.

Gladys May Casely-Hayford’s “Lullaby” also speaks to Black maternity, this time directly through a Black mother’s voice, and offers a radical renunciation of white maternity as a model (Hayford frequently published under the penname Aquah Laluah). The poem, published in The Crisis in March 1929, is in the form of a song sung to a child. The mother begins by encouraging the child to “[c]lose your sleepy eyes”, but the line’s tenor shifts quickly to the threat that “the pale moonlight will steal you” or, in the next line, that “the moon will turn you white” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 565). Like other poems that have presented whiteness or the desire for it as unnatural, the white moonlight here threatens to undermine the bond between mother and child. Rather than loving “your Mammy”, the child, dazzled by the moon’s whiteness, will “only love the shadows, and the foam upon the billows”, and later, “[t]he hooting of the night owl, and the howling of the jackal/The sighing of evil winds”—ephemeral, unreal, ravenous, dangerous things. Twice the mother suggests that the child will be enamored of “the call of mystery”, presumably the vague promises of the white world: “Wherever moonlight stretches her arms across the heavens,/You will follow, always follow, till you become instead,/A shade in human draperies”. Whiteness is thus associated with ghostliness, a kind of death in which the child wanders endlessly without a mother or a home. By contrast, the poem’s speaker offers a rich and sustaining relationship between the child and his Black mother, “whose skin is dark as night”. This mother, who refers to herself as “Mammy” in the poem, is connected to Africa, as her reference to the child as “bibini”, the Fanti word for baby boy, indicates. Where Fauset’s invocation of Sojourner Truth positions her as the foremother to “myriad sons”, Hayford’s mother speaks to just one child, presumably one among the many “healthy human babies” DuBois wished to feature in the pages of The Crisis. Importantly, Hayford’s mother has skin as “dark as night”, a counter to the depleting whiteness of the moon, a contrast also suggested by the rhymes “white” and “night” that end the second and fourth lines of the poem. Her Africanness does not associate her with savagery but rather with a sustaining, nurturing Blackness. These poems thus find beauty and strength not in fealty to white standards of respectable maternity, but in a Black motherhood grounded in the past and looking toward the future.

While the race mother is held up by the editors of the periodicals as a model of “proper” reproduction, her position as the site at which race and sex converge mean that her sexuality must be policed to maintain her status as a proper procreator. As vehicles for uplift rhetorics, African American women were expected to be paragons of virtue, “icons of race pride” (Peiss 2011, p. 213). Yet these same women, particularly those with light skin, were also subject to “sensationalist and sexualized desire, the very embodiment of miscegenation as well as other transgressive sexualities” (Sherrard-Johnson 2007, p. xvi). As an effort to counter these pressures, New Negro visuals tended to emphasize African American women’s propriety and conformity to both visual and moral expectations. As Caroline Goeser demonstrates, the “modern female type” that held sway in most Harlem Renaissance periodicals was “the well-groomed, young middle-class woman” demonstrating correct engagement with modernity and beauty culture (Goeser 2007, p. 190). While these images also served as counterpoints to the derogatory images of “[t]he buffoon, the clown, the criminal”, they were nevertheless restrictive. These “portraits of fair-skinned teachers, socialites, and madonnas” were a way to counter those stereotypes, but they were also a way to restrain women’s sexual expression (Sherrard-Johnson 2007, p. 123)11.

Two other poems by Angelina Weld Grimké, “El Beso” (originally published in Negro Poets and Their Poems in 1923) and “Mona Lisa” (first published in Caroling Dusk) provide an important counterpoint to the desexualization of Black women by racial uplift discourse. Both the poems are love lyrics, addressed to a dark-skinned beloved and figure African American women as both desirable and desiring. In “El Beso”, this figure is associated with “Twilight”—the 16-line poem opens and closes with the line “Twilight—and you”—and the figure’s hair with “gloom”, though the context of the poem positions that “gloom” as equally alluring as the figure’s “provocative laughter” and the “Lure” of “eye and lip” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 171). Though she guarded her private life carefully and never publicly identified as a lesbian, Grimké had “multiple attachments to women” (Honey 2016, p. 31). Gloria Hull points out that “[b]eing a black lesbian poet in America at the beginning of the twentieth century meant that one wrote (or half wrote)—in isolation—a lot that she did not show and could not publish” (Hull 1987, p. 145). While the beloved in “El Beso” is not gendered—the figure’s “teeth”, “hair”, “eye and lip”, and “mouth” could belong to a man or woman, as could the “provocative laughter” and “sobbing”—the figure in “A Mona Lisa” is marked by the poem’s title as female. Grimké draws on the conventions of the love lyric in her descriptions of the beloved’s features, “the long brown grasses/That are your lashes” and “the leaf-brown pools/That are your shadowed eyes” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 173). Here, Grimké is, as Melissa Girard writes, “transform[ing] the iconic object of Western art into a desiring female body” (Girard 2001), one receptive to the speaker’s desire to “cleave”, a word meaning both to cut into (“to cleave/Without sound,/Their glimmering waters”) and to join with (“to sink down/And down/And down …”). While the brown “lashes” and “eyes” could describe the figure in Leonardo’s painting, in the dialogic context of Caroling Dusk, they position this Mona Lisa as an African American woman, as beautiful and enigmatic as Leonardo’s subject. Both these poems assert the beauty and desirability of African American features, and while both appeared in anthologies, rather than periodicals, their authors and audiences were undoubtedly shaped by those magazines. Angelina Weld Grimké’s work engaged with many of these ideas, particularly in offering a vision of what she considers beautiful. In her poems, blackness is a strength, not something to be downplayed.

Grimké, born in 1880, was among the older poets publishing in New Negro periodicals, as was Anne Spencer, born in 1882. Her “Lady, Lady” was published in Survey Graphic’s 1925 special issue, “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro”, edited by Alain Locke (Grimké’s “The Black Finger” was reprinted in this issue, appearing immediately after “Lady, Lady”). The issue features a number of photographs and illustrations, many of the latter drawn by the German American artist Winold Reiss. A section titled “Harlem Types” includes black-and-white drawings of four African American women and a girl, captioned as “Mother and Child”, “Young America: native-born”, “A woman lawyer”, and “Girl in the white blouse” (pp. 652–53); the accompanying text for the section praises Reiss’s ability “to portray the soul and spirit of a people”, suggesting that he was unfettered by “narrowly arbitrary conventions” that have historically stood “in the way of artistic portrayal of Negro folk” (pp. 651–52). The unnamed subjects of these portraits, almost all of whom are wearing white dresses or blouses, look directly at the viewer in most cases (“Girl in the white blouse” gazes off to the viewer’s right). Later in the issue, Reiss’s “Four Portraits of Negro Women” includes three drawings of unnamed women (identified as “A Woman from the Virgin Islands”, “The Librarian”, and “Two Public School Teachers”) and one of Elise Johnson McDougald, whose essay “The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation” follows her portrait (685–88).12 The first edition of The New Negro, an expanded version of this special issue, included a color-plate version of McDougald’s portrait along with color portraits of Mary McLeod Bethune, a mother and child (titled “The Brown Madonna”), and seven African American writers and artists, including Alain Locke, Paul Robeson, and Jean Toomer.13 These color plates were omitted from later editions of The New Negro. McDougald’s portrait—especially as a color plate—takes on “an almost celestial quality” as her “golden-brown skin contrasts with her white clothing, which blends into a white background” (Sherrard-Johnson 2007, p. 25), but her gaze, along with those of the teachers, is trained on the viewer. The other women in “Four Portraits” are darker skinned, with broad noses and lips, and wear the kind of middle-class clothing and hairstyles appropriate to their jobs as teachers and librarians. The girls and women in “Harlem Types” exhibit a similar range of darker skin tones and middle-class hairstyles, and though their socioeconomic class is not indicated by the captions, they nevertheless convey a similar sense of confidence in their status.

McDougald’s essay makes the images’ argument—that these African American women are ideals—explicit. In “The Double Task”, McDougald explicitly acknowledges the “colorful pageant of individual” African American women, “the skin of one … brilliant against the star-lit darkness of a racial sister” and asserts that “the ideals of beauty, built up in the fine arts, exclude her almost entirely” (McDougald 1925, p. 689). Echoing The Messenger’s introduction of their feature “Exalting Negro Womanhood”, McDougald calls out the ways that images of African American women “are most often used to provoke the mirthless laugh of ridicule; or to portray feminine viciousness or vulgarity not particular to Negroes” (p. 689). McDougald suggests one remedy to this parade of “grotesque Aunt Jemimas of the street-car advertisements [that] proclaim only an ability to serve, without grace or loveliness”, where it would be “[b]etter to visualize the Negro woman at her job”, going on to describe categories of African American women, from “the wives and daughters” of wealthy men, to “the women in business and the professions”, “the women in the trades and industry”, and those “in domestic service” (p. 689). As Sherrard-Johnson observes, the essay “draws on sentimental representations of African American women as teachers, homemakers, or nurses engaged in supporting uplift endeavors of New Negro men—the race leaders” (Sherrard-Johnson 2007, p. 25), emphasizing middle-class employment and maternal roles as both appropriate and critical. McDougald touches briefly on the experiences of laboring women, but she does so primarily to assert that domestic laborers ultimately function to free up other women to “find leisure time for progress” (McDougald 1925, p. 691), further engraining the emphasis on middle-class status as the most desirable position.

Yet, despite McDougald’s emphasis on a certain kind of working woman—one who is middle class or aspires to it—as the future of African American uplift, poets such as Spencer center the experiences of laboring women and the costs of whitening. In so doing, the poets denounce the promotion of Black womanhood as a perfect imitation of modern white womanhood. Spencer’s “Lady, Lady” addresses an African American laundress, whose face is “[d]ark as night” but whose hands are “[b]leached poor white” as a result of her work, rather than as a result of using cosmetic creams (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 229). Here, her Blackness and her labor are both central to her beauty and her strength, while whiteness is associated with unnatural “bleaching”, and the “crumpl[ing]” of her hands which have become “[w]rinkled and drawn from [her] rub-a-dub”. The echo of a nursery rhyme in these lines (“Rub a dub dub, three men in a tub”) further underscores the degree to which white supremacy has distorted Black beauty since the laundress’s “rub-a-dub” is not a route to playful transgression as it is in the nursery rhyme (see The Reason Behind the Rhyme: Rub-a-Dub-Dub (2005) for a discussion of the rhyme’s history). Instead, her work whitens clothing and disfigures her hands, leaving them “twisted, awry, like crumpled roots”. Spencer’s invocation of nature through “crumpled roots” connects whiteness to unnaturalness and failure, since crumpled roots cannot properly nourish life.14 At the same time, however, Spencer’s poem links the laboring Black woman herself to nobility—addressing her as “Lady”—and divinity—envisioning her heart as “altared there in its darksome place” lit by “the tongues of flames the ancients knew/Where the good God sits to spangle through” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 229).15 By ending the poem with this invocation of divinity, Spencer “depicts black phenotypes and black ways of being as beautiful”, as Evie Shockley explains (Shockley 2011, p. 122), and insists on the centrality of laboring Black women in the future.

Octavia B. Wynbush’s “Beauty” also evokes laboring hands, celebrating them as a metonym for the work of physical and emotional care for one’s community. In the poem, which appeared in Opportunity in August 1930, she writes, “beauty lurks for me in black, knotted hands,/Hands consecrated in toil that those who come/Behind them may have tender, shapely hands” (Honey 2006, p. 293). Wynbush’s vision may resonate with McDougald’s hope that today’s laborers create the conditions of leisure for future generations. Yet her choice of “lurks”, which implies both hiddenness and ambush, points to what Margo Natalie Crawford describes as “the subtle aesthetic warfare that shapes Harlem Renaissance women’s poetry” (Crawford 2007, p. 138). Beauty inheres in the “black, knotted hands” “consecrated” through labor, as well as in the “tender, shapely hands” that are protected from such toil. Similarly, Wynbush describes “shoulders with bearing heavy burdens stooped” as “beautiful” as those “younger shoulders [that] grow straight and proud” (Honey 2006, p. 293). Like Spencer, Wynbush links the laboring Black body to divinity in a challenge both to white supremacist ideologies that position African Americans as subhuman and to racial uplift ideologies that value genteel work (teaching, homemaking, nursing) above other employment.

Wynbush’s poem was published ten years after Jessie Redmon Fauset’s “Oriflamme” appeared in the January 1920 issue of The Crisis, but the two poems evoke similar visions of laboring African American women as beautiful forebears. Fauset’s attribution of beauty to Truth’s “bowed and black” body marked with “slavery’s mortal scars” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 234) is an implicit rebuke to those—Black or white—who cannot see beauty in her perseverance. Wynbush, too, reproaches viewers who seek beauty only in conventional places: “the sun kissing the sleeping hills awake” or “the moon trailing paths to fairy-land across the slow-moving water” (Honey 2006, p. 293). In Wynbush’s poem, it is men who look, and men who see beauty in light(ness); the language itself is also erotically charged, tying beauty specifically to sexuality and male desire (p. 293). The poem’s speaker, however, does not see light as the mark of beauty, deeming the men’s values “wondrous strange” in both the opening and closing lines of the poem. Instead, the speaker declares “black knotted hands” and “dark, sad faces, too, are beautiful” and links their beauty to their labor and sacrifice, and to care for community.

Love of one’s community is an animating force for the poets, artists, and editors. Helene Johnson’s “Poem”, which appeared in the Caroling Dusk anthology, is addressed to a “Little brown boy,/Slim, dark, big-eyed,/Crooning love songs to your banjo/Down at the Lafayette” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 604). Making use of the conventions of love poetry, the speaker goes on to comment admiringly on the boy’s eyes, hair, and body, praising him as “a prince, a jazz prince” (p. 604). “Gee, brown boy, I loves you all over”, the speaker declares. She then turns her admiration for the boy into self-affirmation: “I’m glad I’m a jig. I’m glad I can/Understand your dancin’ and your/Singin’, and feel all the happiness/And joy and don’t care in you” (p. 604). While Johnson begins the poem in a visual register, exalting the boy’s looks, its subject does not fit the conventions of respectability with his banjo and his “shoulders jerking the jig-wa” (p. 604). The speaker finds self-affirmation in identifying with the “brown boy”, even reclaiming the epithet “jig” for herself. It is his “don’t care” attitude that appeals to the speaker, suggesting an alternative to the eagerness to please some authority more regularly signaled in the pages of New Negro magazines. Johnson’s “Sonnet to a Negro in Harlem”, published in Opportunity the same year, praises another figure for being “incompetent/To imitate those whom you so despise” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 605). Against the mimicry of white beauty and political standards implicitly and explicitly encouraged by so many of the visuals in these magazines, this figure refuses to imitate whiteness, aware that “Scorn will efface each footprint that you make” (p. 605). Instead of seeking acceptance or his “meed of gold”, the figure laughs, “arrogant and bold”, and struts away (p. 605). Like the “brown boy”, the addressee in “Sonnet” is an artist, “head thrown back in rich, barbaric song” (p. 605), though the young man in “Poem”’s joyful disregard of those who would judge his performance has become disdain in “Sonnet”. Once again, however, the poem’s speaker is galvanized by the subject’s self-confidence: “I love your laughter, arrogant and bold,/You are too splendid for this city street!” (p. 605). In turning toward her fellow creators for inspiration, Johnson finds a strategy of exaltation that acknowledges but does not stop with the visual.

Gwendolyn Bennett, like the other women poets discussed here, also turns to explicitly Black figures as sources of inspiration and joy. She opens her poem “To a Dark Girl” with repeated praises in the first four lines for the titular figure’s Blackness: “I love you for your brownness/And the rounded darkness of your breast” along with the “shadows where your wayward eye-lids rest” (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 508). Published in Negro Poets and Their Poems in 1923, the poem highlights the girl’s physical features and praises her dark skin. Its speaker also extols the girl’s connections to an explicitly African past: “Something of old forgotten queens/Lurks in the lithe abandon of your walk/And something of the shackled slave/Sobs in the rhythm of your talk” (p. 508). Bennett’s speaker hopes that the dark girl will “Keep all that you have of queenliness” and “Forge[t] that you were once a slave”, choosing instead to “let your full lips laugh at Fate!” (p. 508). As Wheeler notes, Bennett exhibits “an exceptional cohesiveness across multiple genres” as an illustrator, poet, and fiction writer (Wheeler 2015, p. 211); she and other scholars, including Churchill (2022), note the resonances between “To a Dark Girl” and Bennett’s July 1926 Opportunity cover illustration discussed above.

Bennett challenges herself and her peers to “Write poems—/Brown poems/Of dark words” as she wrote in “Advice”, published in Caroling Dusk (Patton and Honey 2001, p. 509). She contrasts such creators to the “sophist,/Pale and quite remote” whose “pallor stifled my poesy” (p. 509). What the poet wishes to write is “a tapestry” made up of “the dusk softness/of my dream stuff” (p. 509). That tapestry may well include lessons from the sophist—“The keen precision of your words” is likened to “a silver thread” in the tapestry (p. 509)—but Bennett’s poet must resist the sophist’s cynical manipulation in favor of sincere engagement. While all the poets are clearly looking to diverse African American culture for inspiration, Bennett most explicitly invokes fellow Black creators in her poems. In “Song”, which appeared first in Alain Locke’s The New Negro anthology in 1925, Bennett describes “firm, brown limbs”, “moist, dark lips”, and “mothers hold[ing] brown babes/To dark, warm breasts” (Honey 2006, p. 6).These bodies are tied to lived creative experiences—bathing, singing, mothering—that the poet invokes to “weav[e] a song” in which “hymns keep company/With old forgotten banjo songs”. The poem’s second stanza shifts into vernacular English to invoke Black voices (“Singin’ in de moonlight,/Sobbin’ in de dark”), and the third and final stanza concludes with a vision in which “Clinking chains and minstrelsy/Are welded fast with melody” (p. 7). As with her cover illustration for Opportunity, the vibrant Black woman in the present expresses herself with her community. “Words are bright bugles”, Bennett declares, in an assertion of poetry’s promise of self-assertion and celebration. The poem ends with a call to that community and its shared voice: “Sing a little faster,/Sing a little faster,/Sing!” (p. 7).

For Bennett, as both poet and illustrator, and for the other women poets discussed here, connecting their peers to and finding strength and beauty in the full range of the African American experience is a critical task. But while the visual messages of the magazines suggest conformity to white beauty standards as the route to broader cultural acceptance, these poets repeatedly looked elsewhere, to their own lived experiences as mothers, sexual beings, and members of their communities, to offer diverse visions of love, beauty, and strength. Grimké, Fauset, Coleman, Hayford, Spencer, Wynbush, Johnson, and Bennett were challenging white supremacy through their poems, but they were also pushing back against New Negro ideologies that centered whiteness as measures of beauty, intellect, and proper behavior. Their work acknowledges the power of white aesthetics while also creating alternatives designed to lift up Black women and communities in all their diversity, truly exalting Negro womanhood.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Adam Beach, Patrick Collier, Linda Kinnahan, Elizabeth Savage, and the external reviewers for their insightful readings and suggestions. All images in the article are available in the public domain.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This project parallels another series in The Messenger, “These ‘Colored’ United States”, which ran from January 1923 through September 1926 and concerned itself with “national identity, racial geography, and political possibility”, according to Adam McKible (2001, p. 124). |

| 2 | W.E.B. DuBois would make a similar point years later when he reflected on his time editing The Crisis: “Pictures of colored people were an innovation; and at that time it was the rule of most white papers never to publish a picture of a colored person except as a criminal” (qtd. in Wilson 1999, p. xxix). |

| 3 | See Farebrother (2009) for an overview of The Crisis and Hutchinson (2009) for a discussion of Opportunity and The Messenger. See also McKible (2001) on The Messenger’s political phases. |

| 4 | Brinkman (2020) describes this experience as “dialogic cross-reading” (p. 73). |

| 5 | Watkins-Owens (1996) documents the fact that Walker’s advertisements were crucial to the launch of The Messenger (see pp. 98–99). |

| 6 | W.E.B. DuBois himself makes this point in “The Criteria of Negro Art”, writing, “Thus it is the bounden duty of black America to begin this great work of the creation of Beauty, of the preservation of Beauty, of the realization of Beauty, and we must use in this work all the methods that men have used before” (DuBois 1926, p. 296). |

| 7 | One of the silhouetted figures sports a skirt fashioned from what appear to be bananas, invoking Josephine Baker. For more on that resonance, see Miller (1999, p. 217), Wheeler (2015, p. 210), and Churchill’s essay in this issue. |

| 8 | Chafing at this pressure to conform, Bennett, along with a number of other, mostly younger, writers, collaborated in the creation of Fire!!, a short-lived magazine intended to challenge “a lot of the old, dead conventional Negro-white ideas” in Langston Hughes’s descrition (qtd. in Wheeler 2015, p. 211). |

| 9 | Joseph K. Hart makes this point ruefully in “What Shall We Do with the Facts?”, a brief editorial that opens the 1925 Survey Graphic issue devoted to “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro”: “it must be confessed that America is, on the whole, in little mood for facts just now. We prefer fancies more than facts; and we like our fancies to be tinged with fearsomeness” (Hart 1925, p. 625). |

| 10 | While I list original publication sites and dates for all poems discussed, the citations themselves are to Venetria K. Patton and Maureen Honey’s 2001 Double-Take anthology or Maureen Honey’s 2006 Shadowed Dreams anthology. |

| 11 | The “Crisis Maid”, by contrast, gradually reflected “an increasingly emboldened sexuality” (Churchill et al. 2010, p. 83), but, as the term “maid” implies, associated that eroticism with maidenhood, not motherhood. |

| 12 | Aside from a couple of photographs of Harlem sites (a tea shop and a church) that incidentally include African American women, the only other images of a Black woman in the Survey Graphic issue appear in advertisements: an oval portrait of Jessie Redmon Fauset in a Boni & Liveright promotion for There Is Confusion (p. 707) and one of “Mrs. Ancrum Forster”, the director of The Ancrum School of Music, in an advertisement for the school (p. 719). |

| 13 | The New York Public Library has digitized these plates, which can be viewed online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-new-negro-an-interpretation#/?tab=about (accessed on 23 January 2022). |

| 14 | Spencer makes similar indictments of whiteness in poems such as “White Things”, first published in The Crisis in 1923. |

| 15 | Brittney Cooper usefully reminds us that white women have “long claimed ladyhood uniquely for themselves, refusing, to the great chagrin of Black women, to acknowledge that sisters of a darker hue were ladies, too” (Cooper 2018, p. 155). One only need visualize Jim Crow bathroom signs—Gentlemen, Ladies, Colored—to consider why addressing this Black laundress as “Lady” has particular resonance for Spencer and her readers. |

References

- Austin, Paula C. 2018. “Conscious Self-Realization and Self-Direction”: New Negro Ideologies and Visual Representations. Journal of African American History 103: 309–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Allison. 1996. Reconstructing Motherhood: Pauline Hopkins’. Contending Forces. Studies in American Fiction 24: 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, Bartholomew. 2020. “The Strong Matter of Unknown Names”: Modeling Topics and Cross-Reading Poems in The Crisis. Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 11: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Daphne A. 2001. “The Deeds Done in My Body”: Black Feminist Theory, Performance, and the Truth about Adah Isaacs Mencken. In Recovering the Black Female Body: Self-Representations by African American Women. Edited by Michael Bennett and Vanessa D. Dickerson. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Suzanne W. 2016. Little Magazines and the Gendered, Racialized Discourse of Women’s Poetry. In A History of Twentieth-Century American Women’s Poetry. Edited by Linda A. Kinnahan. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 170–85. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Suzanne W. 2022. “The Whole Ensemble”: Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Interartistic Exchange in Black American Modernism. Humanities 11: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Suzanne W., Drew Brookie, Hall Carey, Cameron Hardesty, Joel Hewett, Nakia Long, Amy Trainor, and Christian Williams. 2010. Youth Culture in The Crisis and Fire!! Journal of Modern Periodical Studies 1: 64–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Brittany. 2018. Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower. New York: St. Martin’s. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Margo Natalie. 2007. “Perhaps Buddha is a woman”: Women’s Poetry in the Harlem Renaissance. In The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance. Edited by George Hutchinson. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 126–40. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Laura. 1994. Bordering on the Body: The Racial Matrix of Modern Fiction and Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. 1924. Our Babies. The Crisis 28: 199. [Google Scholar]

- DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. 1926. The Criteria of Negro Art. The Crisis 32: 290–97. [Google Scholar]

- English, Daylanne. 2000. W.E.B. DuBois’s Family Crisis. American Literature 72: 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farebrother, Rachel. 2009. The Crisis (1910–1934). In The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, Volume 2: North American 1894–1960. Edited by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 103–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fauset, Jessie Redmon. 1922. Some Notes on Color. The World Tomorrow 5: 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, Melissa. 2001. On “A Mona Lisa”. In Modern American Poetry. Edited by Cary Nelson and Bartholomew Brinkman. 15 June 2020. Available online: https://www.modernamericanpoetry.org/criticism/melissa-girard-mona-lisa (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Goeser, Caroline. 2007. Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Donal. 2016. On Company Time: American Modernism in Big Magazines. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Joseph K. 1925. What Shall We Do with the Facts? Survey Graphic: Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro 6: 625. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, Maureen, ed. 2006. Shadowed Dreams: Women’s Poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, 2nd ed. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, Maureen. 2008. Teaching Women Poets of the Harlem Renaissance. In Teaching the Harlem Renaissance: Course Design and Classroom Strategies. Edited by Michael Soto. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, Maureen. 2016. Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, Gloria. 1987. Color, Sex, and Poetry: Three Harlem Renaissance Writers. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, George. 1995. The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, George. 2009. Organizational Voices: The Messenger (1917–1928) and Opportunity (1923–1949). In The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, Volume 2: North American 1894–1960. Edited by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 784–800. [Google Scholar]

- McDougald. 1925. The Double Task: The Struggle of Negro Women for Sex and Race Emancipation. Survey Graphic 53: 689–91. [Google Scholar]

- McKible, Adam. 2001. Our(?) Country: Mapping ‘These “Colored” United States’ in The Messenger. In The Black Press: New Literary and Historical Essays. Edited by Todd Vogel. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Nina. 1999. Making Love Modern: The Intimate Public Worlds of New York’s Literary Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Venetria K., and Maureen Honey, eds. 2001. Double Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peiss, Kathy. 2011. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard-Johnson, Charlene. 2007. Portraits of the New Negro Woman: Visual and Literary Culture in the Harlem Renaissance. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley, Evie. 2011. Renegade Poetics: Black Aesthetics and Formal Innovation in African American Poetry. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thaggert, Miriam. 2010. Images of Black Modernism: Verbal and Visual Strategies of the Harlem Renaissance. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Reason Behind the Rhyme: Rub-a-Dub-Dub. 2005. All Things Considered. Available online: https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5038237 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Tucker, Irene. 2012. The Moment of Racial Sight: A History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, Cheryl A. 1995. Women of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walser, Hannah. 2020. Under Description: The Fugitive Slave Advertisement as Genre. American Literature 92: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins-Owens, Irma. 1996. Blood Relations: Caribbean Immigrants and the Harlem Community, 1900–1930. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegman, Robyn. 1995. American Anatomies: Theorizing Race and Gender. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Belinda. 2015. Gwendolyn Bennett: A Leading Voice of the Harlem Renaissance. In A Companion to the Harlem Renaissance. Edited by Cherene Sherrard-Johnson. Malden: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 203–17. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Deborah. 2008. Picturing the New Negro Woman. In Black Womanhood: Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body. Edited by Barbara Thompson. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 227–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Sondra Kathryn. 1999. Introduction. In The Crisis Reader: Stories, Poetry, and Essays from the N.A.A.C.P.’s Crisis Magazine. New York: Modern Library. [Google Scholar]

- Young, John K. 2022. The Crisis. In The Routledge Companion to the British and North American Literary Magazine. Edited by Tim Lanzendörfer. New York: Routledge, pp. 295–304. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).