“The Whole Ensemble”: Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Interartistic Exchange in Black American Modernism

Abstract

:1. Introduction

I want to see lithe Negro girls,

Etched against the sky

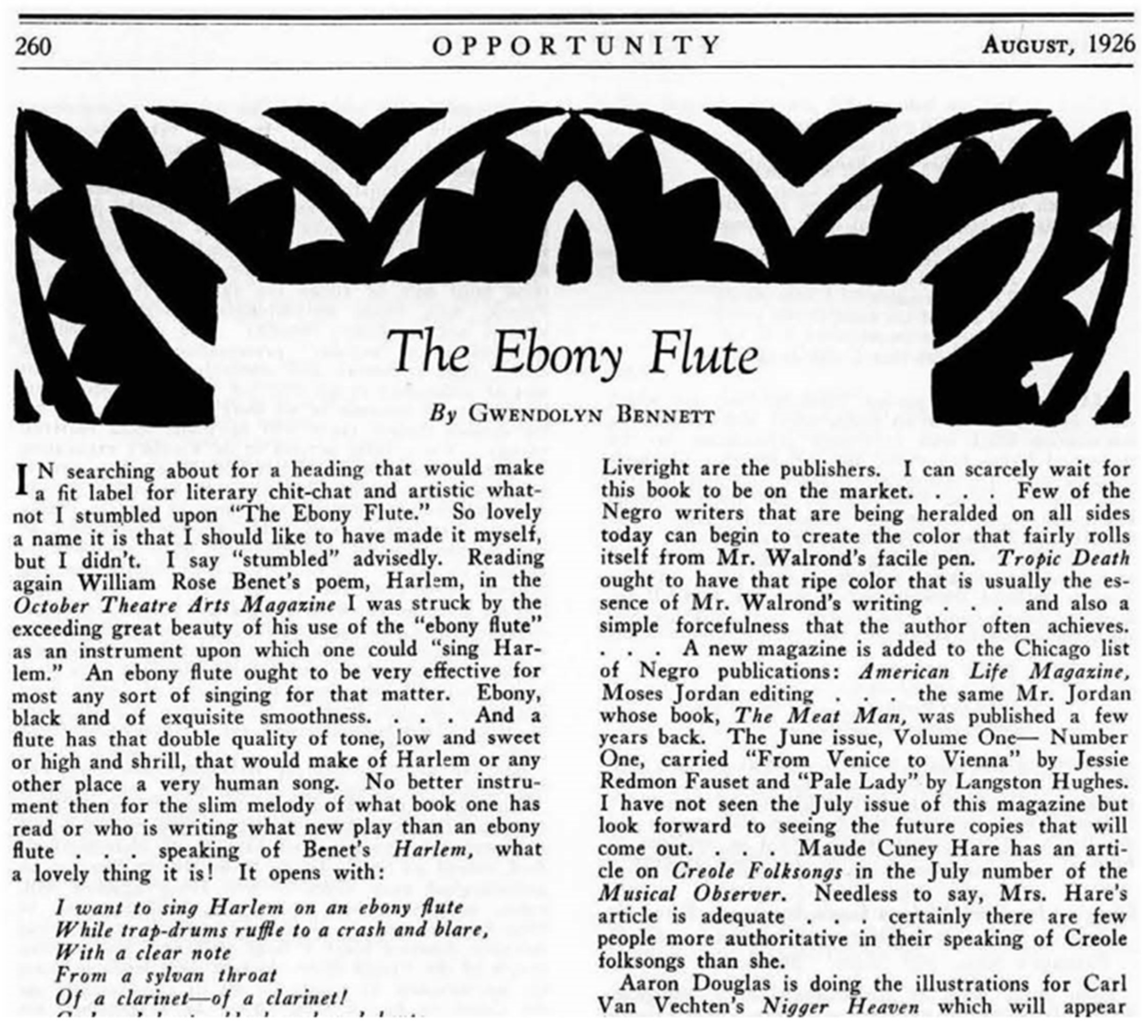

As art historian Carolyn Goeser points out, this poetic image prefigures Bennett’s July 1926 Opportunity cover illustration (Goeser 2007, p. 191). The illustration, which I examine in Part 3 in connection with Josephine Baker and Black Deco, incorporates a chorus of semi-nude dancers shimmying in front of a stylized Africanist backdrop. Like the illustration, the poem emphasizes the visual artifice of the “etched” scene, representing Africa as an imagined space that stimulates the modern imagination, rather than an authentic, primitive place.While sunset lingers.

I want to feel the surging

Of my sad people’s soul

The ironic revelation of the last line exposes how Primitivist performances may be misconstrued by white audiences who see the “minstrel-smile” but fail to detect more complex expressions of pain, desire, and aspiration. The poem strikes a balance between the desire to extricate “my sad people’s soul” from the legacies of slavery and white supremacy, and the urge to connect “lithe Negro girls” to an African heritage in order to affirm their beauty.Hidden by a minstrel-smile.

Sing a little faster,

Sing a little faster,

Both the anaphoric repetition and the emphatic exclamation echo Langston Hughes’s poem “Danse Africaine” (Hughes 1922): “The low beating of the tom-toms,/The slow beating of the tom-toms…/Dance!” Although Bennett’s poetry has occasionally been belittled as imitative, it is better understood as responsive and synergistic, reflective of her sensitivity to the artistic currents of her time. She operated like an antenna, picking and recombining emerging signals from across the arts in her own transmedia work. Just as her poems sample sounds and images from the poetry of Hughes, Cullen, and others, her responses to Baker echo the performer’s style, rhythm, and tempo.Sing!

2. The Article

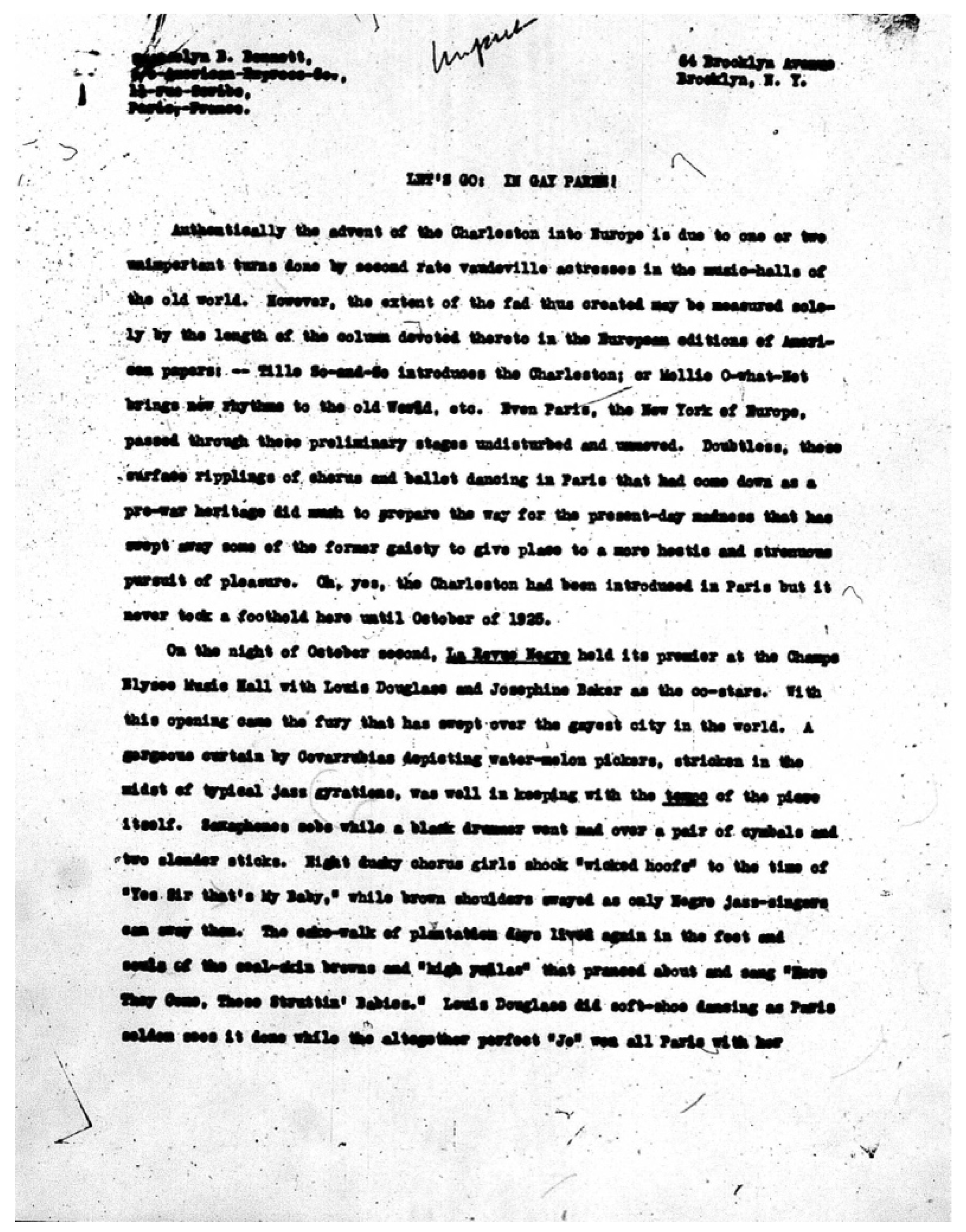

2.1. Call and Response at the Folies Bergère

Bennett engages in her own fast-paced verbal dance, mimicking the Primitivist discourse that posits Black performance as a spontaneous, atavistic expression of a primal past, whether African-born, Southern plantation-based, or some phantasmic merging of both. Yet as she mimes this well-worn vocabulary, she ironically distances herself from its underlying Primitivist assumptions, putting animalistic terms such as “wicked hoofs” in scare quotes that highlight the artifice, and calling attention to Baker’s “adorable mimicry” of minstrel show motifs. La Revue Nègre’s pounding rhythm is a work of artistry rather than the natural expression of a primitive race, and their color is a source of “wealth”. Bennett’s language both describes and adopts the Revue’s strategy of exploiting and subverting Primitivist stereotypes by recalibrating them in a distinctly modern, ironic, energetic style.On the night of October second, La Revue Negrè held its premier at the Champs-Élysées Music Hall with Louis Douglass and Josephine Baker as the co-stars. With this opening came the fury that has swept over the gayest city in the world. A gorgeous curtain by Covarrubias depicting water-melon pickers, stricken in the midst of jazz gyrations was well in keeping with the tempo of the piece itself. Saxophone sobs while a black drummer went mad over a pair of cymbals and two slender sticks. Eight dusky chorus girls shook “wicked hoofs” to the time of “Yes Sir that’s My Baby”, while brown shoulders swayed as only Negro jazz-singers can sway them. The cake-walk of plantation days lived again in the feet and souls of the seal-skin browns and “high yallas” that pranced about and sang “Here They Come, Those Struttin’ Babies”. Louis Douglass did soft-shoe dancing as Paris seldom sees it done while the altogether perfect “Jo” won all Paris with her adorable mimicry. And through all its wealth of color there pounded the mad rhythm of “Hey, Hey! Bump-ty-Bum! Hey, Hey!”

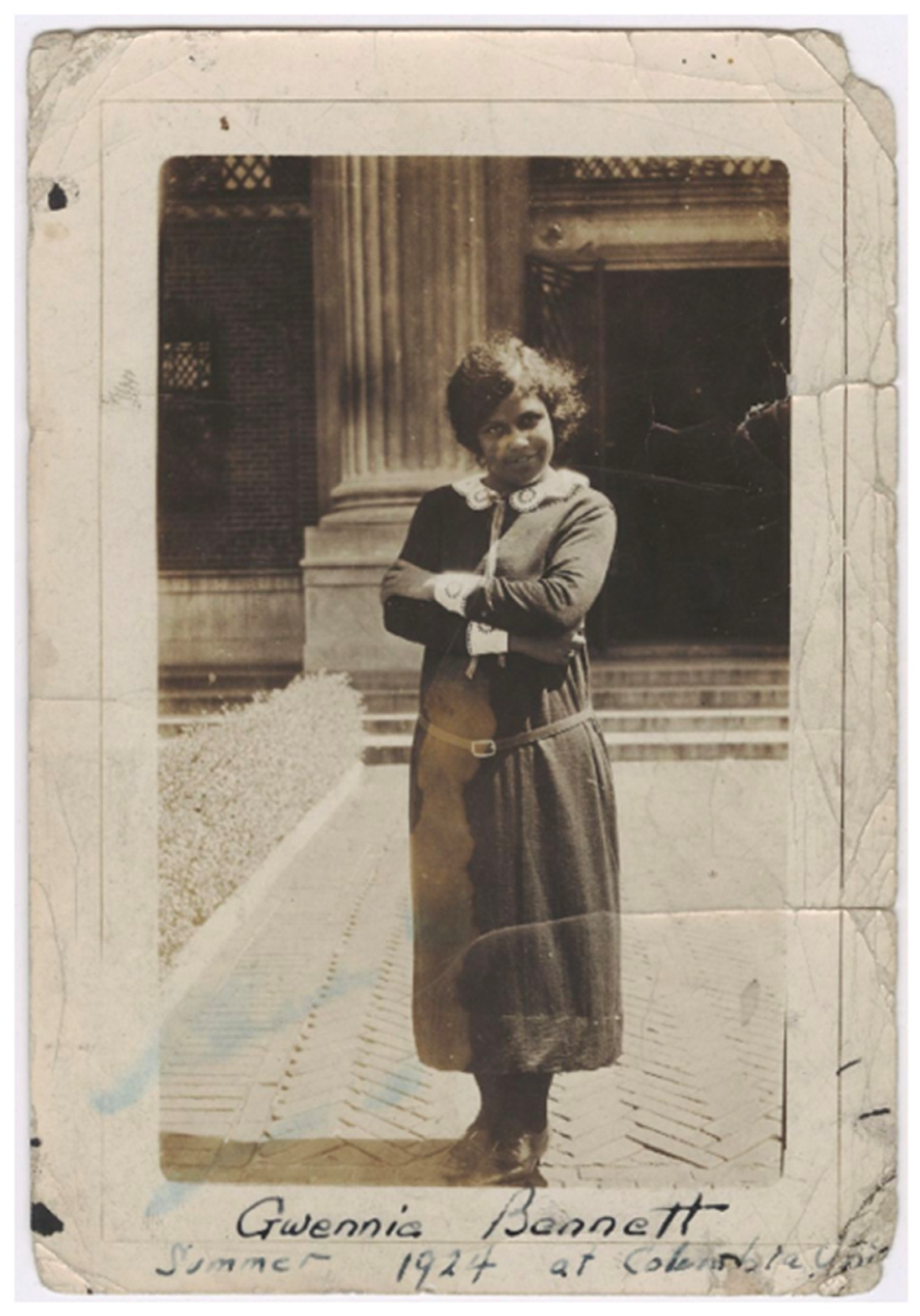

2.2. Biographical Interlude: Finding Community in Paris

The French were not colorblind; they were simply not color averse. Throw in a dash of French exoticism and paternalism and Paris had the makings of a utopia for African Americans accustomed to slipshod and occasionally murderous treatment in their home country. There’s no place like home. And Paris was definitely unlike home—in a good way.

For two days now it has rained—the people tell me that this is typical Paris weather. A cold rain that eats into the very marrow of the bone… and I am alone and more homesick than I ever believed it possible to be. […] at the Foyer [International des Étudiantes] they discourage my plans for studying art anywhere except at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art—which I think is silly! They talked to me as though I were a kid who had come here just to sort of dabble in art. And it rains… and I am cold and heartsick… and nearly starved… no umbrella, no coat except for my suit-coat—no one… Paris!!!(26 June 1925, Bennett 2018, p. 179)

She told Langston Hughes that she knew of no place so “joyous, yet so miserable” as Paris and admitted that she felt as if she had “no right to be here” (28 August 1925, qtd by Barton 2021). Three months into her stay, Bennett was so unhappy that she considered “buying immediate passage home” (Govan 1980, p. 75).Money is scarce and I am dreadfully lonely for home and friends… I am about as convinced as I can be that I can’t write. I feel so close to real discouragement.(14 January 1926, Bennett 2018, pp. 200–1)

The sense of shared culture and intimacy among “we colored folk” lifted her spirits, quickening her appreciation for the City of Light:Then at 4:15 a.m. to dear old Bricktop’s. The Grand Duc extremely crowded with our folk. Lottie Gee there on her first night in town and sings for “Brick” her hit from “Shuffle Along”—“I’m Just Wild About Harry”. Her voice is not what it might have been and she had too much champagne but still there was something very personal and dear about her singing and we colored folk just applauded like mad.(8 August 1925, Bennett 2018, p. 181)

I shall never quite forget the shock of beauty that I get when the door was opened at “Brick’s” and as we stepped out into the early morning streets… looking up Rue Pigalle there stood Sacred-Heart… beautiful, pearly Sacre-Coeur as though its silent loveliness were pointing a white finger at our night’s debauchery. I wished then that so worthy an emotion as I felt might have been caught forever in a poem but somehow the muse refuses to work these days.(8 August 1925, Bennett 2018, p. 182)

2.3. Emulating Baker’s Image, Sound, and Movement in Words

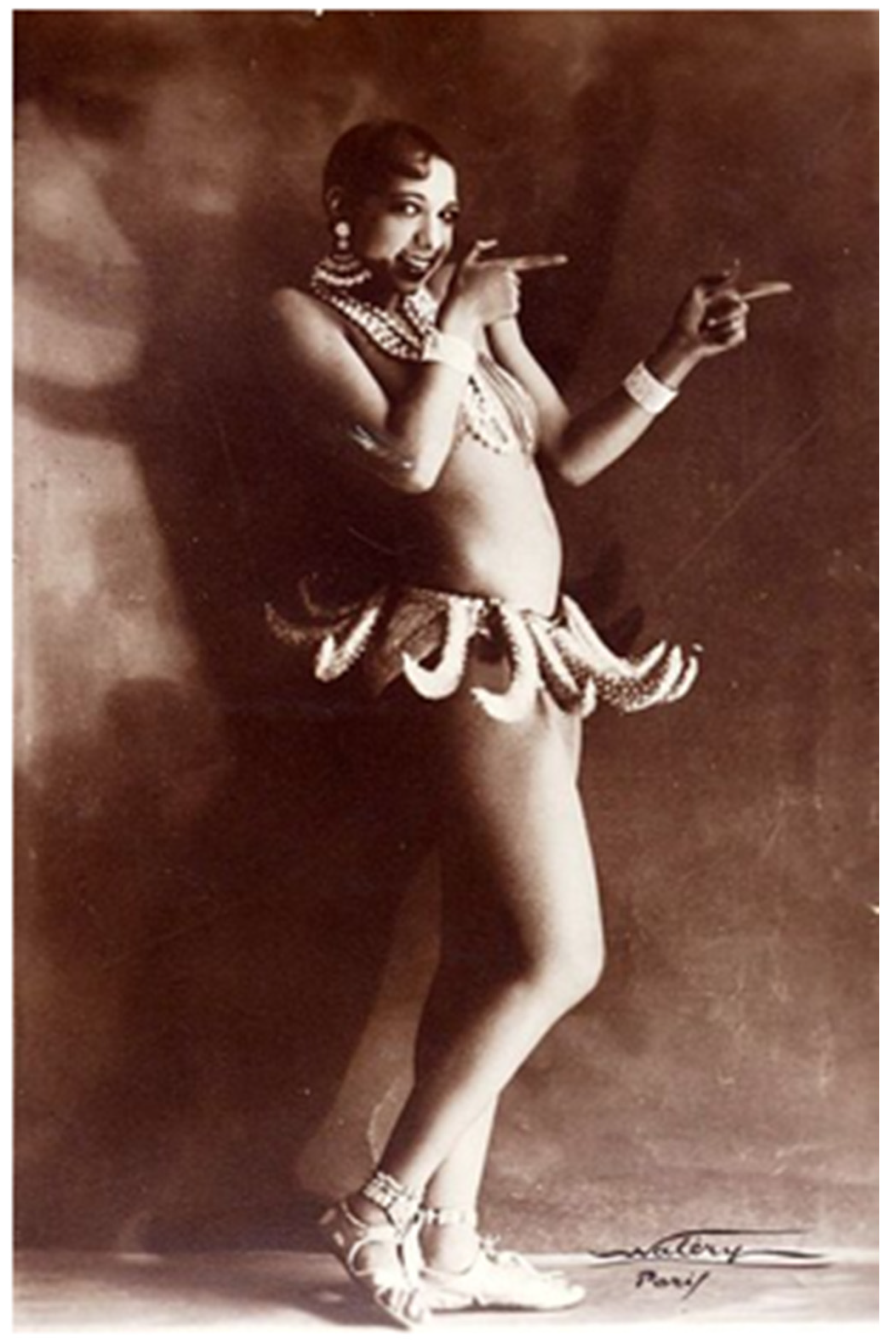

Baker’s self-possession is remarkable, as she navigates a “maze” of white bodies without getting lost. She stands out as a “dusky star” against a backdrop of whiteness, reversing the order of the Western universe with a Negro artist reigning over Europeans. Bennett represents Baker as a sophisticated, world-class Black performer who exploits and subverts Primitivist stereotypes. At first mention, “Jo” is surrounded by wide-eyed winks that call attention to her “adorable mimicry” of the Pickaninny motif.Josephine Baker, the dusky star opened at the Folies Bergère as the premier of the program. Her sleek brown body sways through the maze of white ones as night after night makes her more and more certain in her position as the idol of Paris.

Bennett extricates Baker from racial classifications by asserting that she is better than any dancer “black or white”. Although she spells out the racist epithet used to describe Baker’s legs, she denaturalizes the term by putting it in scare quotes. In Bennett’s interpretation, Baker’s facial distortions mimic and exaggerate the racialized performance vocabulary of minstrelsy, working “within and against familiar versions of racialized femininity” in an effort to liberate Black bodies from typecasts (Brown 2008, p. 190), and using dance, mime, and song to “wage resistance against the images that confined and demeaned her” (Wall 1995, p. 109). The heightened artifice produces a beauty of its own, Bennett suggests, even as Baker’s hyperbolic gestures expose the artificiality of the racist stereotypes. In describing Baker’s “ludicrous masks” and “adorable mimicry”, Bennett anticipates Joan Riviere’s 1929 exploration of “womanliness as a masquerade” and Jayna Brown’s 2008 reframing of racial mimicry to account for the agency of Black women performers. Bennett recognizes in Baker the inherently performative nature of womanliness, particularly as it intersects with Blackness: the social imperative to perform within a pre-set gendered, racialized vocabulary, and the power that can be wielded from distortions and exaggerations of those cultural scripts.The inimitable “Jo” does a Charleston like no one else in the world, white or black. Her long shapely “n----- legs” fly this way and that with a rhythm and beauty that is maddening. Her sleek black head turns this way and that as she twists her face into all sorts of ludicrous masks. With warmth and beauty she carries the rhythm of her race through a review that is world famous… Let’s go, Jo! Hey, Hey! Bumpty-bump!!

3. The Illustration

3.1. Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Black Deco

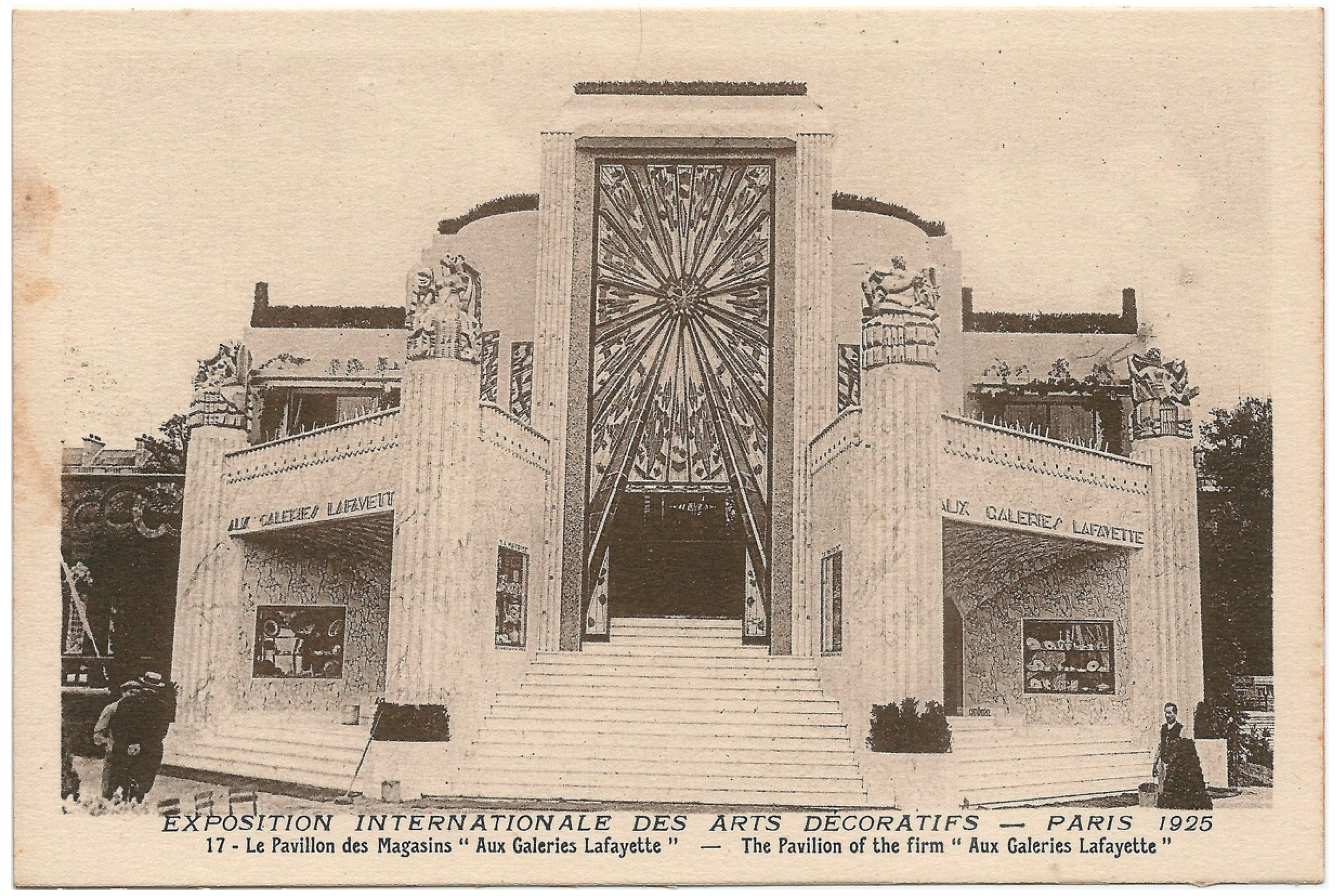

Once Black Deco became fashionable, its artistic stock value plummeted. John Warne Monroe explains its devaluation, arguing that when the avant garde’s embrace of Art Negrè was marketed and mass-produced as Black Deco in the 1920s, it lost its cultural caché: “What began as an avant-garde provocation made its way ever more deeply into the mainstream, and as such, came to look far more like a fashion trend than like a timeless example of high art” (Monroe 2019, p. 107).The first flush of African art’s influence on the Parisian avant-garde in the prewar years developed after the war into a commercialised version of “all things African”, a sort of blackened version of Art Deco that debuted at the Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris in 1925. This “black deco” cousin was soon applied decoratively to many areas of Parisian lifestyle: furniture was embellished with animal skins and African designs; clothing stressed natural textiles and jungle pelts; jewellery boasted precious metals, gems and enamelling with jazzy contemporary designs. Black deco gradually settled into a style ripe for marketing, and black juxtaposed with white became the vogue.

3.2. Biographical Interlude: Discovering the Decorative Arts

Bennett embraced the decorative arts as the vehicle through which she could make a mark as an artist, viewing her batiks as more “modern” than her paintings. Touring the Expo offered an especially significant “revelation” of “modern work”, as it illuminated a synergy between poetry, art, furniture, and design. It led her to the realization that various art forms were engaged in similar processes of transforming abstract concepts (love, bulk, slimness) into sensory and physical forms (wind, desk, clock). As an artist and writer, she was energized by such synesthetic processes. Such thoughts likely informed the synergy of music, dance, fashion, and visual art in her July 1926 cover illustration for Opportunity.“… I too like the moderns although I don’t feel that I myself am one… at any rate not in painting. My batiks are more so. This year in Paris has been a revelation to me so far as modern work is concerned. Our American modernists are about a thousand years behind the Europeans. Why even interior decoration here has a decidedly modern twist to it. That was plainly visible through the exhibits at the Exposition des Arts Decoratifs this summer. I never saw such furniture. It was rather like the modern poet who says this sound of soft wind is love and its turnings are my darlings lips … it was rather impressionism. They said here is bulk and we will call it desk or here is slimness and we will call it clock….”(to Jackman [“Rosebud”], 23 February 1926, Bennett 2018, p. 202)

3.3. Drawing Josephine Baker into the Chorus

4. The Column

4.1. The Ebony Flute: “Literary Chit-Chat and Artistic What-Not”

Ah, little road, brown as my race is brown,

Your trodden beauty like our trodden pride,

Frost’s contribution indicates not only that he read Opportunity magazine—and her column—with great interest, but also that the conversation Bennett staged built an artistic and literary network that transcended racial and geographical divides.Dust of the dust, they must not bruise you down.

4.2. Biographical Interlude: Rebuilding Community

In a letter to Carl Van Vechten typed on Howard University letterhead, Bennett described her environs as a cultural waste land, echoing T. S. Eliot’s poem: “I am in a dry land where no water is … barren fields are as dry as dust here”.12 Not only was the social scene stuffy and superficial, but her low-paid but highly demanding teaching responsibilities at Howard commanded most of her waking hours.In New York she had been a participant in a stimulating, spontaneous arts movement still in its formative stage: the transition to faculty member at a historically black college where traditionally life for both students and faculty is more regimented, more inhibited, and yet conversely more taxing, was difficult and traumatic. The emphasis shifted from pursuit of the arts to an accent on social life. As Bennett and others recall, dress, drink and appearance were the apparent hallmarks of Washington’s closed Negro society. If one had financial resources one dispersed them on fraternity and sorority activities or fine clothing, parties and liquor and not on books or other dimensions of the arts.

4.3. Playing Baker’s Tune on an “Ebony Flute”

Bennett has a keen eye for trends and accomplishments among African American performers, and their recognition by European audiences is a signature achievement. Baker is the first performer Bennett names, but she is one in a growing list of Black female performers, part of a larger, diasporic New Negro movement. As in her essay on Baker, Bennett puts less emphasis on her exceptionalism than on her participation in a larger tradition. She gives Nora Ray Holt significantly more coverage in a column where most artists get only a sentence or two, perhaps highlighting her achievements because she was an educated music critic as well as a popular performer. Yet the accomplishments of this glamorous, famously blonde performer ultimately bring Bennett to a pithy and wry deconstruction of race as a distinguishing category:“With surprising surety American Negroes who go to the European capitals as entertainers in the fashionable night clubs and cafes become endeared to the French pleasure-seeker. The Chocolate Kiddies, La Revue Nègre, Josephine Baker, and Florence Mills… each caught and held the admiration of first Paris and then later other cities on the continent. At the opening of Les Nuits du Pardo, the most chic cabaret Paris has yet seen, Nora Holt Ray entertained in an inimitable way … she accompanies herself at the piano and her voice has a touching appeal in it…”(December 1926, p. 391)

Here, as in her article on Baker, Bennett implicitly contrasts white audience’s racial ambivalence—their fascination and bewilderment by Black women who defy categorization—with African Americans’ ability to recognize and live with the complexities and contradictions of racial constructions.“…the French are in happy consternation over the miracle of La Blonde Negress… strange, we live here side by side by many members of the black race whose skins are fairer than some of their white neighbors”.(December 1926, p. 391)

At one and the same time Paris continues to laud the terpsichorean arts of Josephine Baker, colored star of the Folies Bergère. The Magazine Section of the New York World, for January 9th, carries a full-page article on Miss Baker, entitled How an Up-to-date Josephine Won Paris, by Carl de Vidal Hunt. There is much tom-foolery the in article about her undying belief in the power of a rabbit’s foot and a good deal of misstatement about the company with which she first appeared in Paris, but even this rather uninformed writer arrives at this beautiful conclusion about a Negro girl, whose rise to envied stardom in the music halls of Europe, has been so phenomenal:… Her lithe, young body, looking like a Venetian bronze come to life, seemed to incarnate the spirit of unrestrained joy. It is a wild thing, yet graceful and harmonious—a demon unchained, yet delicate in its sleek, symmetrical beauty.

The first word that stands out in this Baker encomium is “terpsichorean”, meaning “of or relating to dance”. Terpsichore was one of the nine muses who presided over learning and the arts in Greek and Roman mythology. The patron of dance and choral song (and later lyric poetry), she is often depicted dancing and holding a lyre. Combining terpsis (“enjoyment”) and choros (“dance”), her name literally means “enjoying dance”. “Choros” is also the root of “chorus” (“choruses” in Athenian drama consisted of dancers as well as singers). It seems significant that Bennett would choose this unusual word, which asserts her own status as a highly educated, literate woman, even as it links Baker to the Classical muses, connecting the popular art of the dance halls with the most celebrated and lofty artistic traditions, including lyric poetry. The term also builds a bridge between Baker’s performative art and Bennett’s own poetry, situating them as sister artists in the same chorus.Miss Baker is barely over twenty years old and full of all the youthful enthusiasm that such an age usually carries with it. She loves clothes… it seems a divine twitch of fate that at present she wears only clothes designed by Paul Poiret, one of the world’s greatest designers for women… There is also another very famous Negro woman who is dancing for Europeans. Djemil Anik, one of France’s colonists, is at present one of that country’s most famous interpretive dancers…(March 1927, p. 90)

In reporting the latest developments in theater and performance, Bennett assumes that Black performers are household names. African American choreographer Louis Douglas’ status is signaled by his collaboration with Austrian-born director Max Reinhardt. This yoking of African American and European celebrities reaches its climax in the marvelous marriage of Josephine Baker to a European Count. His name is less important, however, than her triumph in ascending to the level of royalty. Her words “are gems” that devalue aristocratic stock with their indifference to status and propriety. Baker’s colloquial language renders “his great big family” and “coat of arms and everything” equal parts glamorous and absurd. The “and everything” tag-on suggests that the inherited wealth and prestige of European royalty can be acquired by anyone audacious enough to try, including Baker herself—a mixed-race granddaughter of enslaved people, who survived her childhood by dancing on street corners in St. Louis slums. In letting Baker speak for herself, Bennett showcases the performer’s “adorable mimicry”—a form of double talk that simultaneously feigns naive, starstruck admiration and ironically deflates aristocratic myths.Louis Douglas, who staged Josephine Baker in her colored show in Paris, is to do the same for Africana. Prior to directing in Paris Mr. Douglas was dance director at the Grosse Schauspielhaus for Max Reinhardt in Paris… speaking of Josephine Baker reminds me that the altogether remarkable ‘Jo’ has done the inimitable again… according to the New York Morning World for June 27th she has now become Countess of d’Albertini… in Europe she has been exposed to royalty and in the manner of the true stage darling has captured one of the nobility in matrimony… her words on the subject are gems: “He sure is a count—I looked him up in Rome. He’s got a great big family there with lots of coats of arms and everything”.(August 1927, p. 242)

5. Conclusions: Collective Culture Building through Interartistic Expression

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Following the practice of the New York Times, I capitalize “Black” to refer to people and cultures of African origin or descent because doing so conveys respect for a “shared history and identity”; I use lowercase “white” because “there is less of a sense that ‘white’ describes a shared culture and history. Moreover, hate groups and white supremacists have long favored the uppercase style, which in itself is reason to avoid it”. Uppercasing ‘Black’ (2020), https://www.nytco.com/press/uppercasing-black/ (accessed on 1 March 2021). |

| 2 | The most significant studies of Bennett to date are Sandra Y. Govan’s (1980) dissertation, Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist Lost, which restored Bennett from near oblivion, and Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola’s Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings (Bennett 2018), whose expert editing have made much of Bennett’s work available in a single volume for the first time. Nina Miller and Maureen Honey devote chapters to Bennett, and T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting details her Paris residency. See (Miller 1999; Honey 2016; Sharpley-Whiting 2015). |

| 3 | Word/image studies include: Martha Jane Nadell’s (2004); (Carroll 2005; Sherrard-Johnson 2007); Caroline Goeser, Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Modernity (University of Kansas Press, Goeser 2007); (Thaggert 2010; Hill 2014). |

| 4 | Studies of performing arts culture in the Harlem Renaissance include: (Krasner 2002; Elam and Jackson 2005; Vogel 2009; Brown 2008; Sharpley-Whiting 2015). |

| 5 | Much of Bennett’s artwork was destroyed in two fires, one in 1926 and the other after her death in the 1980s. See Wheeler and Parascandola’s Introduction to Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings (Bennett 2018, p. 12). |

| 6 | Bennett’s published poems, along with her surviving artwork and a good deal of her unpublished writings, letters, and diaries are reprinted in Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and Beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings (Bennett 2018). Since her unpublished writings never had the benefit of an editor or proofreader, I correct minor misspellings in order to avoid distracting [sic]s. |

| 7 | The typescript of this essay is held in The Gwendolyn Bennett Papers at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and reprinted in Bennett (2018, pp. 156–58). |

| 8 | Bennett, letter to Harold Jackman, 25 February 1926, Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. Box 1|Folder 19. 1925–26. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 (accessed on 1 March 2021). Portions of Bennett’s Paris diary and letters are reprinted in Bennett 2018, and when they are I cite the date and the page number from that collection. Others are in The Gwendolyn Bennett Papers at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (Bennett Papers, Beinecke n.d.) or in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture (Bennett Papers, Schomburg n.d.). Hereafter, I refer to the Gwendolyn Bennett Papers at the Beinecke as GBP-B and to the Bennett papers in the Schomburg Center as GBP-S. If the item is available in the Beinecke Library Digital Collection, I also provide the link. |

| 9 | The Bennett letters to Harold Jackman cited in this paragraph are accessible online: 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. Box 1|Folder 19. 1925–26. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 (accessed on 1 March 2021). |

| 10 | Maureen Honey says Bennett “attended the 2 October 1925, première of La Révue Nègre on the Champs Élysée, where Josephine Baker wowed French crowds with her exotic dancing” (99–100). But Bennett writes to Harold Jackman on 27 October 1925 that she has not yet seen the “Revue Negre” and “shall be going in a day or two” (Bennett, Gwendolyn B., 5 autograph letters and 1 typed letter, signed, to Harold Jackman. Box 1|Folder 19. 1925–26. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16867529 (accessed on 1 March 2021)). Her article gives the date of 24 April 1926 as Baker’s “final coronation”, so it is possible that she saw Baker perform in late October 1925 and again in April 1926. |

| 11 | The entire run of “The Ebony Flute”, from August 1926 to May 1928, is reprinted in Black Writers Interpret the Harlem Renaissance. Edited by Cary D. Wintz. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. (Wintz 1996, pp. 104–37). Hereafter I will refer parenthetically to the column date and page numbers from the original Opportunity magazine publication. |

| 12 | Bennett to Van Vechten, n.d. Though undated, this letter is preserved in a sequence written in October and November of 1926. Beinecke Rare Books & Manuscript Library, Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters, Box 2|Folder 56. 1926, undated. https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16820216 (accessed on 1 March 2021). |

References

- Ada “Bricktop” Smith, owner, and others at Bricktop’s club Rue Pagalle, Paris. 1932. The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Available online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/6a352fe2-7ff9-8a42-e040-e00a18067cb6 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Archer-Straw, Petrine. 2000. Negrophilia: A Double-Edged Infatuation. The Guardian. September 23. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2000/sep/23/features.weekend (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Barton, Melissa. 2021. Mondays at Beinecke: ‘All the News as Well as the Scandal’—Gwendolyn Bennett’s Letters from Paris with Melissa Barton. Public Zoom Lecture. December 6. Available online: https://library.yale.edu/event/mondays-beinecke-10 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Beinecke. n.d. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers. New Haven: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Bennett. 1926. Cover Design. Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, July. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. “Opportunity” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1926-07. Available online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/99911ba0-39dc-0131-202e-58d385a7b928 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Bennett, Columbia University. 1924. Gwendolyn Bennett, Columbia University, summer 1924. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Books Library, Yale University. Available online: https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2036373 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Bennett, Gwendolyn. 1996. The Ebony Flute. In Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life. Monthly column, August 1926–May 1928; Reprinted in Wintz 1996. New York: National Urban League, pp. 104–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Gwendolyn. 2018. Heroine of the Harlem Renaissance and beyond: Gwendolyn Bennett’s Selected Writings. Edited by Belinda Wheeler and Louis J. Parascandola. State College and London: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett with a group of friends. n.d. “Gwendolyn Bennett with a group of friends: Charley Boyd, Hoggie Payne, Jayfus Ward, ‘The Fat One’ Hoffman and ‘Bon Bon” Simmons’”, n.d. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Available online: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/e970b1c0-967a-0131-026b-58d385a7bbd0 (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Brown, Jayna. 2008. Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carby, Hazel V. 1999. The Sexual Politics of Women’s Blues. In Cultures of Babylon: Black Britain and African America. London: Verso, pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Anne Elizabeth. 2005. Word, Image, and the New Negro: Representation and Identity in the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Anne Anlin. 2010. Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colin, Paul. 1925. Posters for “La Revue Nègre” (1925) and Bal Nègre (1927) at the Champs Elysées Music Hall in Paris. Courtesy Estate of Paul Colin/Artists. Rights Society (ARS). New York: ADAGP. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Walter C., and Sandra Y. Govan. 1987. “Gwendolyn Bennett.” Afro-American Writers from the Harlem Renaissance to 1940. Edited by Trudier Harris, Thadious M. Davis and Thomson Gale. Detroit: Gale Cengage, 7Letras. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Elam, Harry J., and Kennell Jackson. 2005. Black Cultural Traffic: Crossroads in Global Performance and Popular Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Lucy. 2003. Designing Women: Cinema, Art Deco, & the Female Form. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goeser, Caroline. 2007. Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. [Google Scholar]

- Govan, Sandra Y. 1980. Gwendolyn Bennett: Portrait of an Artist List. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: Print. Ann Arbor. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Lena. 2014. Visualizing Blackness and the Creation of the African-American Literary Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honey, Maureen. 2016. Aphrodite’s Daughters: Three Modernist Poets of the Harlem Renaissance. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Langston. 1922. Danse Africaine. Academy of American Poets. Available online: https://poets.org/poem/danse-africaine (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Hull, Gloria T. 1987. Color, Sex, & Poetry: Three Women Writers of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krasner, David. 2002. A Beautiful Pageant: African American Theatre, Drama, and Performance in the Harlem Renaissance, 1910–1927. New York: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Rosalind E. 1985. No More Play. In The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 42–85. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, Jerry, and Sandra Govan. 2010. Gwendolyn Bennett: The Richest Colors on her Palette, Beauty and Truth. International Review of African American Art 23: 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pavillon des Magasins “Aux Galeries Lafayette”. 1925. Postcard. Pavillon des Magasins “Aux Galleries Lafayette”. Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Moderns. July 3. Public Domain. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paris-FR-75-Expo_1925_Arts_d%C3%A9coratifs-pavillon_des_Galeries_Lafayette.jpg (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Makaryk, Irena R. 2018. April in Paris: Theatricality, Modernism, and Politics at the 1925 Art Deco Expo. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- McHenry, Elizabeth. 2002. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Nina. 1999. Making Love Modern the Intimate Public Worlds of New York’s Literary Women. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William John Thomas. 1994. Picture Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, John Warne. 2019. From Art Negre to Art Primitif: Black Deco, Ethnology, and Surrealism in the Late 1920s. In Metropolitan Fetish: African Sculpture and the Imperial French Invention of Primitive Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 104–39. [Google Scholar]

- Murari, Tim. 2008. Josephine Baker, Radiant Temptress. The Guardian. August 25. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2008/aug/26/3 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Nadell, Martha Jane. 2004. Enter the New Negroes: Images of Race in American Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg. n.d. Gwendolyn Bennett Papers, 1916–1981. New York: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library.

- Sharpley-Whiting, T. Denean. 2015. Bricktop’s Paris African American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrard-Johnson, Cherene. 2007. Portraits of the New Negro Woman: Visual and Literary Culture in the Harlem Renaissance. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thaggert, Miriam. 2010. Images of Black Modernism: Verbal and Visual Strategies of the Harlem Renaissance. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uppercasing ‘Black’. 2020. The New York Times. June 30. Available online: https://www.nytco.com/press/uppercasing-black/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Vogel, Shane. 2009. The Scene of the Harlem Cabaret: Race, Performance, Sexuality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walery. 1927. Josephine Baker in a banana skirt from the Folies Bergère production “Un Vent de Folie”. Wikimedia Commons. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Baker_Banana.jpg&oldid=471910353 (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Wall, Cheryl A. 1995. Women of the Harlem Renaissance. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, Belinda. 2013. Gwendolyn Bennett’s ‘The Ebony Flute’. PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 128: 744–55, Modern Language Association of America. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintz, Cary D., ed. 1996. Black Writers Interpret the Harlem Renaissance. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zeck, Melanie. 2014. Josephine Baker, the Most Sensational Woman Anybody Ever Saw. New York: Oxford University Press, Available online: https://blog.oup.com/2014/06/josephine-baker-sensational-woman/ (accessed on 1 March 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Churchill, S.W. “The Whole Ensemble”: Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Interartistic Exchange in Black American Modernism. Humanities 2022, 11, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11040074

Churchill SW. “The Whole Ensemble”: Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Interartistic Exchange in Black American Modernism. Humanities. 2022; 11(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleChurchill, Suzanne W. 2022. "“The Whole Ensemble”: Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Interartistic Exchange in Black American Modernism" Humanities 11, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11040074

APA StyleChurchill, S. W. (2022). “The Whole Ensemble”: Gwendolyn Bennett, Josephine Baker, and Interartistic Exchange in Black American Modernism. Humanities, 11(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11040074