Abstract

This interdisciplinary paper presents an autoethnography of an author who self-publishes her own fanfiction via print-on-demand (POD) services. It reflects upon the subject of fan writer as self-publisher, touching upon shifting notions of authorship, the format of the book, and literary practice, with implications for both fan studies and Library and Information Science (LIS). While its findings cannot be generalised to the wider fan community, the paper posits five reasons for this practice: (1) the desire to publish a work that is technically, if not necessarily creatively, unpublishable (due to copyright laws); (2) the physical presence of the book bestows ‘thingness’, physical legitimacy, and the power of traditional notions of authorship to one’s work; (3) the materiality of the book and the pleasure afforded by its physical, tactile, and haptic qualities; (4) books can be collectible (fan) items; (5) self-published books can act as signifiers both of the self-as-author and one’s creative journey. The paper recommends further study be conducted on a wider scale, engaging other self-publishing fanfiction authors in their own practice to test the conclusions presented here.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, fanfiction has become virtually synonymous with the digital and ephemeral. Nevertheless, fan studies has only recently begun to acknowledge contemporary fanfiction in physical print formats, quite apart from the traditional fanzines popular before the mainstreaming of the internet. This has most strikingly taken the form of fanbinding, a previously niche fannish practice that has recently been gaining ground. While fanbinding is a significant harbinger of what I would term the renaissance of print fanfiction, current research (while still in its nascent stages) tends to focus on the reader, in their role as fan binder and de facto publisher of fanfiction in book form. We have not yet seen research into fanfiction that is printed via print-on-demand (POD) technologies; moreover, there has not yet been any examination of the author as the (self-)publisher of their own fanfiction.

This autoethnography has been approached from the lens of two disciplines: that of Library and Information Science (LIS)—which is concerned with questions of the book, copyright, and the publishing industry—and that of fan studies—which is concerned with fannish practice such as writing fanfiction1. While I am primarily an LIS scholar, the focus of my research is on the liminal spaces between these two disciplines, and this paper centres on two important aspects of my life—that of the fan writer and that of the bibliophile. While this is an autoethnography of a fan who publishes their own fanfiction, it is also an autoethnography of someone who loves and works with the book.

It is also, therefore, important to recognise that this work is foregrounded in the disciplines of both LIS and fan studies. I use the format of autoethnography, a research method that, while not employed often, is well-established in both LIS and fan studies. In writing this autoethnography, I have applied Kuhlthau’s (1991) six-step Information Search Process (ISP) model as a framework, as recommended by Lawal and Bitso (2020), an approach that has its basis in LIS. But I have also relied heavily on autoethnographical practice as laid out within fan studies, finding especial resonance with the work of Jeannette Monaco, Ross Garner, and Matt Hills. In particular, I follow Monaco’s concept of autoethnography as ‘memory work’, on “the use of memory as a way of reflecting on personal and collective lived experience” (2010, p. 109). I also make use of Garner’s longitudinal perspective, tracing the “affective fluctuations which form a normative part of long-term fan attachments” [original italics] (2018, p. 94). Similar works, such as that of Driessen and Jones (2016), track the (aca)fan’s attachment to the fan object through an extended period, wherein affective fluctuations, from passion to ambivalence, even to hatred, are noted and reflected upon. Here, I chronicle not merely the affective fluctuations of my life as a fan from early childhood; I also chronicle the affective fluctuations of my relationship with the book. I reflect upon not only the fan object as extension of self, but the book as extension of self.

It is important to note the tension within fan studies regarding ethnography in general. There is the oft-laid charge that fan scholars are too close to the subject of their research to examine it objectively. To take a step back, we can look to Marcus and Fischer’s (1999) seminal text, Anthropology as Cultural Critique, and what they term the “crisis of representation” within anthropology, a crisis that “arises from uncertainty about adequate means of describing social reality” (p. 8). This crisis has been born from the move of secure, totalising paradigms of thought to ones that cast doubt on whether social reality can be adequately represented through description, let alone adequately explained (p. 12). The researcher may be an outsider to a community/subject but cannot claim objectivity in representing it. This is a problem not merely of fan studies, of course, but of cultural studies as a whole.

The mythos of objectivity is especially contentious in fan studies because “the researcher and the fan are often the same thing” [original italics] (Evans and Stasi 2014, p. 14). Matt Hills (2002) extensively discusses this problem and how, in the face of the impossibility of ‘true’ objectivity, fan scholars (or aca-fans) strive for a critical, almost self-effacing, ‘good’ subjectivity of “self-suspension and radical hesitation” (p. xxii). “We are confronted by a moment,” Hills notes, “where the subject cannot discursively and ‘rationally’ account for its own fan experience… The ‘good’ subjectivity imagined within fandom is…not a resolutely rational subjectivity. Rather, it is radically ‘open’; ‘bad’ or denigrated subjectivity, in this case, is a passionless, hyper-rational, intellectualising subjectivity” (2002, p. xxii). This is problematic because it does not adequately represent the lived experience (subjectivities) of fans; it others fans and others the academy to fans.

Hills (2002), and later Evans and Stasi (2014), proposes a method of mitigating the effects of this hyper-rational, impoverished subjectivity within fan studies, and that method is self-reflexive autoethnography. Of course, autoethnography is not without its detractors, having faced a long list of criticisms over the decades, summarised by Ellis et al. (2011) as “being insufficiently rigorous, theoretical, and analytical, and too aesthetic, emotional, and therapeutic” (p. 283). There are also accusations of narcissism and self-indulgence, even “public masturbation” (Sparkes 2002, p. 212). Such criticisms, however, fail to see the purpose of autoethnography, erroneously positioning “art and science at odds with each other, a condition that autoethnography seeks to correct. Autoethnography, as method, attempts to disrupt the binary of science and art” (Ellis et al. 2011, p. 283) by challenging the crisis of representation and accommodating “subjectivity, emotionality, and the researcher’s influence on research, rather than hiding from these matters or assuming they don’t exist” (p. 274).

Hills, with regard to autoethnography, is careful to note that “this kind of self-reporting cannot be assumed to be infallible or ‘correct’” (2002, p. 52), but he also reminds us that it “asks the person undertaking it to question their self-account constantly, opening the ‘subjective’ and the intimately personal up to the cultural contexts in which it is formed and experienced” and “can open up the possibility of inscribing other explanations of the self; it can promote an acceptance of the fragility and inadequacy of our claims to be able to ‘explain’ and ‘justify’ our own most intensely private or personal moments of fandom and media consumption” [original italics] (2002, p. 43).

In light of this, I employ the recommendations of both Hills (2002, pp. 51–52) and Evans and Stasi (2014, pp. 14–16), using self-reflexive methods as far as I am able. This includes continuous self-reflexive questioning; acknowledgement of my own academic power in writing this work; attempting not to disguise my personal attachments through theory; and treating myself as equal to others.

I am also aware of Booth’s criticism of autoethnography as potentially static and limiting, “constrained by a particular time and space, the temporal and spatial coordinates in which the researcher has undertaken the research” (Booth 2015, p. 107). In response to this, I have chosen not to focus my work on my present experiences as a fan and a bibliophile, but to harness Garner’s (2018) longitudinal perspective by engaging in Monaco’s (2010) ‘memory work’. Far from limiting myself to a ‘moment in time’, my account begins in early childhood and works towards the present day. Thus, I am able to contextualise this work by recounting “former periods of…cultural situatedness within the constraints of social class, race, ethnic and gendered identities, thus enabling [me] to make sense of [my] present selves” (Monaco 2010, p. 110). Both Monaco and Garner are careful in their work to position themselves according to these myriad identities, ones accrued over their lifetimes and thus informative of their current positionality. Throughout this paper, I strive to document the same.

The wider goal of this paper is both to pose and to begin to answer the question: Why do fans self-publish their fanfiction, specifically in book format? As an interdisciplinary work, it also explores and challenges several key factors relevant to the fields of Library and Information Science (LIS) and fan studies, respectively. For LIS, these key factors are: (a) publishing–what alternative methods of publishing do fans employ outside of traditional structures, and what are their attitudes towards it; (b) copyright—what tensions exist between the self-publishing fan writer and copyright; (c) the book—what is the continued importance of its materiality in the (post-)digital age? For fan studies, the factors explored are: (a) the ‘renaissance’ of print fanfiction—how is fan writing moving back towards material productivity; (b) the monetisation of fanfiction—what relationship does self-published POD fanfiction have with neoliberal capitalist ideologies and the traditional gift economy of fanworks; (c) new trends in fanfiction—what insight can be gained into the fannish practice of self-publishing fanfiction, a practice that has not yet been discussed?

I do not claim to answer any of these questions completely here; as an autoethnography, it goes without saying that one lived experience cannot necessarily be generalised to a wider population. What I intend, however, is to pose these questions throughout and begin to answer them through my own memory work. It is also my hope that this work will be the prologue to a multilived autoethnography, where “one person’s autoethnographic analysis can resonate with others’ fan experiences” (Hills 2021, p. 152). By presenting and reflecting on my own practice, I hope to prompt other fans to explore their own similar practice and work towards fully answering the questions laid out above.

Lastly—as this is an autoethnography–let me introduce myself. I am at this time in my early forties, female, asexual, and mixed race white-Chinese. I was born into a working-class family, just south of Greater London, England (where I still live), in the early 1980s, although, like Jeannette Monaco, my family “’became’ middle-class” (2010, p. 111), largely through the efforts of my father, who, when I was in my teens, pursued higher education in his early forties (he was the first in his family to do so). My experiences, therefore, reflect not only the liminal spaces I inhabit within academia, but also those I have been embedded in throughout my life—my mixed cultural and ethnic background, the social mobility and changed socio-economic status of my family over the years, and my sexuality (which I did not fully accept until my thirties). My father looms large in this work, if not tangibly then certainly spiritually—it was he who first encouraged my love of the book, and of storytelling, from a very young age. Without his influence, I would not have had cause to ever live through the experiences I write of here.

2. Childhood Fanfiction and the Codex

I gave myself a repetitive strain injury handwriting a 500-plus page novelisation of Final Fantasy VII.

I was about seventeen or eighteen at the time; it was an exam year, and I remember vividly the pain of writing my A-level exams later that summer, a pain that still flairs up now and then. This was the year I opened my first email account and built my first website (a fan site dedicated to Cantopop singer Cass Phang 彭羚). Yet, despite the imminent mainstreaming of the internet and my household finally obtaining a dial-up connection, this was still an era before fanfiction became so inherently, almost exclusively, synonymous with the digital.

I am handwriting this now, on a train, and trying to remember when I stopped handwriting fic before committing it to type. Even until well into the 2000s, I was handwriting my fics before typing them up and posting them to Fanfiction.net. And even now, I keep a notebook and pen by my bed at night so I can write scenes and dialogue as they come to me (my creative impulses are more active at night). I prize the pile of notebooks that are the fruits of these labours. They are treasure troves of metatextual narrative–commentary, notes to self, timelines, and plot strategies, frustrated meltdowns, and ballpoint pen sketches of my favourite characters. Unique and messy and un-mass-producible. The journey, the gestation, of so many stories, both finished and unfinished. Stories of characters that do not belong to me, but are of worlds that are indubitably mine, intimate and personal—and invisible to all but myself.

A voracious reader as a child, the format of the book was as familiar as it was comforting and also infinitely collectible. Despite money always being tight in my younger years, one thing my father always made sure my siblings and I had was books. My father was liberal in this regard, and looking back on it, this must have been a privilege that many others of my age and circumstances may not have had. Having all my Ms. Wiz books up on my shelf, one by one, with their magnificently colourful covers, was a source of great satisfaction to me. I knew every part of the book, without knowing what they were called–the blurb, the frontispiece, the colophon, the contents page, the illustrations. Books were magic; their format was the way stories were naturally and irreducibly configured. Later, I would unthinkingly reproduce the configuration of the codex in my own narrative works. During the eighties and early nineties, my fanfiction was wedded to it.

I began writing fiction at an early age. If my father instilled a love of books into me, he also instilled a love of storytelling. My siblings and I were treated each night to our teddy bears coming to life, where they would tell their own stories in their own words. My father would give each one a voice, and as I grew a little older, I would write down these stories for my siblings. From this ‘original fiction’, I would graduate to fanfiction, where I enjoyed ‘scribbling in the margins’ of my favourite franchises.

Here, the configuration of the book would become noticeable. I would repurpose notepads and barely used school exercise books to write my own spin-offs of Enid Blyton’s Malory Towers series and The Baby-Sitters Club books, a new Sailor Moon tale, or real person fiction (RPF) of the 1960s band, the Mamas & the Papas. This was before I knew fandom was a ‘thing’. I remember feeling embarrassed if a friend, visiting or staying over for the night, expressed an interest in reading them. Even then, the obsession, the passion, of this nameless thing I now know to be called ‘fandom’ was a source of inherent shame. It was ‘sad’ to like something too much, even more so something so terminally ‘uncool’. Fandom as pathology (Jenson 1992) was the default perception in those days. I could not even trust my closest friends not to judge me for it. I could not trust them not to scoff at the fact that I prized fandom enough to dress my ‘throw-away’ writings as the ‘real thing’, as a book.

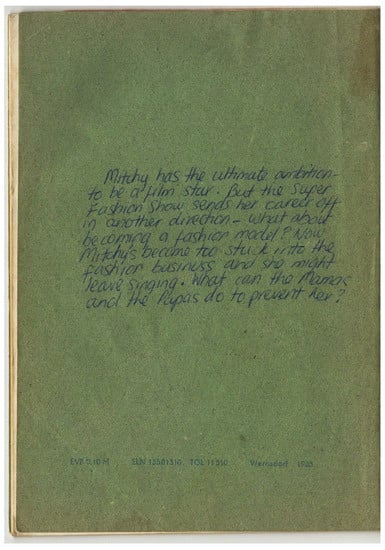

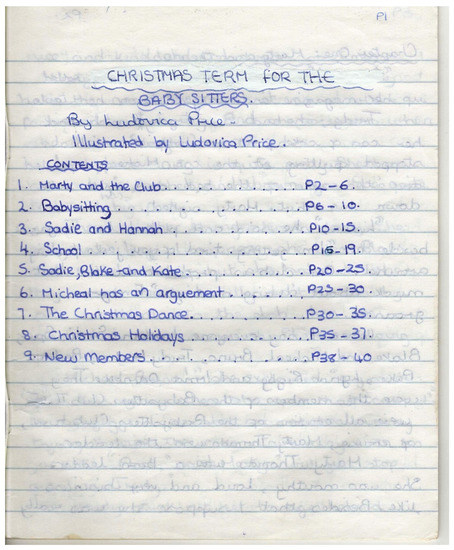

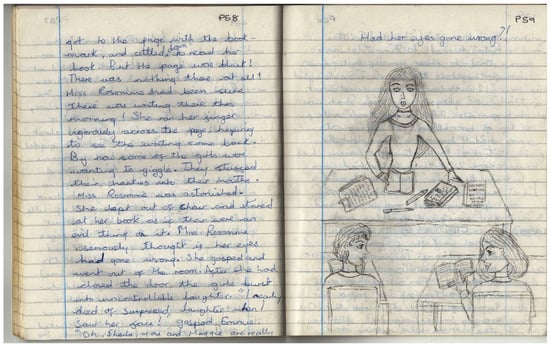

Yesterday, I went through my horde of old creative works, a stash I had not touched in twenty-odd years. I found those old exercise books. I had remembered them vaguely, peripherally, as formative of the adult writer I would become. What I had not remembered was the ‘bookness’ of them. I wrote blurbs and pull-quotes on the back (Figure 1). I wrote a contents table, and I numbered the pages (Figure 2). I drew illustrations, and sometimes, I captioned them (Figure 3). I presented my fanfic as books; I mimicked the textual conventions of the source material. I mirrored what I had read; I replicated the format of the story, the written narrative, as I conceived and experienced it. I wondered at this long-forgotten facet of my past. I marvelled at how I would unwittingly come back to ‘bookness’, to the ‘book as thing’ (see Pressman 2020, chp. 3, for more on the book as thing) much, much later.

Figure 1.

Blurb on the back of Michelle and the Super Fashion Show, a Mamas & Papas fanfiction written by the author, circa 1995.

Figure 2.

Contents page for Christmas Term for the Baby Sitters, a Baby-Sitters Club fanfiction written by the author, circa 1993.

Figure 3.

Captioned illustration from Rita at St. Hilary’s, a Malory Towers spin-off fanfiction written by the author, circa 1992.

As a child, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, my answer would always be “I want to write books”. In a household without a computer, yet filled with books, I understood this to mean an author of published fiction. The creative urge of a child is not governed by racialised or sexualised identities, but by simple truths—I wanted to be a writer simply for the joy of writing. I did not write because I was biracial or asexual—in fact, I had no conception of these constituent parts of my identity when I first innocently set my heart on being a published author. It was only as I grew older that writing became intertwined with my growing sense of being ‘other’, becoming not only an act of pleasure, but also a form of escape. I did not fit in either in or out of school and suffered othering due to my ethnicity, introverted personality, and my inability to conform to the sexual norms of my peers. Writing gave me the voice to express what I could not speak aloud, the page effectively becoming a canvas on which to safely explore who I was without fear of judgement or censure. Thus, writing developed from a mode of self-expression to also being a method of managing emotional distress and promoting self-worth. During my teenage years, dreams of publication promised a symbolic as well as actual means of surmounting the loneliness and inner turmoil I often felt growing up. Indeed, I would turn to writing often during mental health crises in later years. This is not unprecedented—from a psycho-social standpoint, the therapeutic benefits of creative and literary writing have long been known (see Pennebaker and Seagal 1999). Even writing for publication has been noted as a tool in the therapeutic process, with Gillam (2018, p. 113) citing several published authors whose publications have documented and made sense of their experiences, sharing them with others. This is a concept I will touch upon later.

Writing is one thing; self-publishing is another. While my writing was affected by my intersectional identity, I cannot say that self-publishing my work has been driven by any explicit therapeutic benefits, except perhaps to tangibly prove my own creative self-worth to myself. Not coincidentally, my urge to write has diminished since I started to become comfortable with my identity—in the past two and a half years I have barely written at all. My urge to self-publish books (mainly artbooks) has continued.

3. Going Digital

The first fanfic I remember typing up was that massive novelisation of Final Fantasy VII. I cannot remember exactly why I did so at the time, although I imagine it was because it seemed more polished, more finished. Typeface did not have the messiness inherent in handwriting; it did not have the strikethroughs and the added phrases and the scribbling in the margins. Soon, I would type up my manuscripts for other, more practical, reasons.

Fandom, as I now know it to be, was something I discovered around 1998. I discovered it accidentally, through fandom webrings and personal fan sites. I cannot remember exactly when I found Fanfiction.net, but it was a revelation to me. I had found my people, after thinking myself a species of one for the longest time. I made an account and started to post. I even used my own name as my penname. Back then, ‘Ludi’ was unusual enough to be considered a penname rather than a personal name. And privacy was a lot easier to maintain in a Google-less, Facebook-less world.

Suddenly, and rather unceremoniously, I had achieved my goal. I was now published. I had a readership. For the first time in my life, my voice was being heard. Like-minded fans appreciated my work, and thus, I gained recognition, reassurance, confidence, and a measure of self-worth. I had not even needed to go through the rigmarole of going through the publishing industry at all.

No wonder that at this time fanfiction became primarily a digital phenomenon, moving en masse from the physicality of the zine to the formless ether of the internet. Yet, despite the physical handicap of my RSI, I continued to write my fanfic by hand before typing up. I had already jettisoned the bookish format of my youth, mostly scribbling in notepads or on loose leaves, which better suited my needs. The computer in our house was a shared device, so I could not write on a computer freely. We had a laptop—a work laptop that had been given to my father when he was promoted after completing his Master’s degree. Sometimes, he allowed us to use it, but not often. Writing by hand was in better tune with the ebb and flow of my creative impulses anyway—when the urge hit, I would simply pick up a pen and a sheet of paper and write. When the family computer was free, I would prop up my manuscript on the desk beside me and transcribe it, bit by bit. I suspect that was the case for many fan writers at the time, who had minimal or restricted access to computers and the World Wide Web. But I was lucky that I had any sort of access; at that time, to publish one’s words online to the world was a privilege. In many ways, it still is, depending on where in the world you live and what socio-economic demographic you inhabit. It was only later, in the early to mid-2000s, when I saved up to buy my own laptop (another privilege), that I slowly became more accustomed to writing fanfic digitally from scratch.

I must confess, however, that fanfiction still retained vestiges of the codex for me. Even if my manuscripts were now too chaotic, messy, and unpolished, I still kept them. If they were not already bound in notebooks, I would put them into folders or ring-binders. For a long time, while I still had space, I shelved them as I would normal books. They were—are—important to me. Like my personal diaries and journals, they instantiate a particular journey in my life–a creative one. To have that journey physically present was and is a counterpoint to the ephemeral nature of the digital sphere that encapsulates my publicly fannish life and outputs. In a moment, everything I have ever published on the internet could be deleted, made to disappear, without my consent or knowledge. But the physicality of the book, of the written word, the material markers of my fannish journey—they will remain.

4. All Is Vanity?

When I was in secondary school, a girl in my younger sister’s class had her book, a fantasy novel, self-published. Even amongst us teenagers, there was the assumption that it probably was not very good, tainted by “the assumption that anyone who was good enough to get a publisher, would” (Bradley et al. 2009, n.p.). Subsidy publishers, more popularly known as vanity presses, were common throughout the twentieth century as a way to publish your book without going through the traditional publishing process—if the author was willing to offset the not-insubstantial costs of production. It is worth noting that self-publishing is not synonymous with the vanity press, the difference being that with self-publishing the writer does “all the work of writing, designing, and distributing a book, usually after contracting a printer to print it” (Laquintano 2018, p. 35), rather than the press itself. Self-publication has a long and venerable history (see Dworkin et al. 2012, for example); however, Laquintano also notes that “self-publishing was conflated with vanity publishing enough that… it is fair to conclude that in many cases self-publishing became tinged with the stigma that vanity presses helped produce” (2018, p. 35). It is because of this popular conflation that I choose not to treat the two modes of publication differently here. I had never been schooled in the concept of self-publication, but the prejudice inherent in having to pay to have your work published had already, somehow, been ingrained in me.

It is, of course, ingrained in all of us. Our culture is deeply wedded to the published author as a “venerated social identity” (Laquintano 2018, p. 39), to the sacralisation of first the manuscript and then the codex. The cultural axiom that the book is sacred and that the published author is consequently to be celebrated has been bolstered by the approbation of the publishing industry, an industry that wields an enormous amount of power and prestige, effectively censuring and therefore restricting amateur writing practice. The ‘vanity stigma’ has an indelible hold on the public consciousness—this stigma tells us that self-publishing writers are bad writers; they are the hapless victims of predatory publishers; they do not do their research into the publishing industry and how things should be done; they put out bad quality products. As Thurston (2020, p. 139) says: “[s]elf-publishing is conventionally assumed to be a last resort. Maybe the work is not good enough to interest somebody else in publishing it […] such reasons are considered to signify a failure on the author’s part, a failure to get properly published [my italics].” Promulgating this stigma has served the publishing industry well, perpetuating the myth that authors are not worth their salt unless they subject themselves to socially approved pathways to publication (and thus willingly join the capitalistic machine that the industry represents). Ideologically, economically, this prejudice aids corporate publishers in effectively gatekeeping who gets to publish, what gets published, and, of course, what will turn the most profit (Laquintano 2018, p. 40).

Technology has done much to break down this stigma and make a dent in the corporate publishing industry’s stranglehold on literary dissemination. For my sister’s classmate, cheap, digital-based, print self-publishing options had been less than a decade or so away, had she waited. During the 2000s, the self-publishing boom began when it allied with print-on-demand (POD) technologies that dramatically brought down the cost of book production. First, self-publishing houses such as AuthorHouse or Xlibris offered a route for frustrated authors, facing mainstream rejection, to publish, and for a much-diminished fee compared to earlier subsidy publishers (Dilevko and Dali 2006). Later, platforms such as Amazon and Lulu allowed anyone with the basic technical savvy to create a PDF of their manuscripts and print their work in book format. Ingram, which has served the self-publishing industry for several decades, now works with online POD services to distribute the work of independent publishers and writers on a global scale (Cutler 2015).

By this time, I had been self-publishing for quite a while—albeit online. There is a perception that online publication is still not truly publication in the strict sense, and I would argue that this is more so for literature on the periphery of the mainstream, such as erotic stories, queer literature, and, of course, fanfiction (which often encompasses both queer and erotic elements). Many of us fan authors are still conditioned to say “I posted my new fic today”, or “I posted a new chapter”, instead of “I published a new fic”, or “I published a new chapter”. Yet, what we are doing is publishing. We are self-publishing (in more ways than one, but I will come to that later). What is it about publishing writing online that makes it lesser than? This is still a question I grapple with, despite chafing against the prejudice of fanfic in general as lesser than. Why is publishing fanfiction considered lesser than?

Cutler (2015) frames traditional self-publication in terms of authors seeking to fulfil a dream “of seeing their books in the hands of readers and on the shelves of their local booksellers and libraries” (p. 84). This, no doubt, is still the case with many self-publishing authors today—authors who, like fanfic writers, take advantage of modern digital affordances which allow them to build readerships without ever having to publish through traditional systems, who have no need to dream of their stories finding distribution and an audience. In the early 1990s, Susan Stewart conceived of an author’s community of readers as “a largely imaginary construction, an abstraction unavailable to any given author or reader at any given moment” (Stewart 1992, p. 21), but the internet has done much to demolish that construction, to contract the space between author and reader. Wattpad and Amazon are cases in point, where writers can build their own fanbase (Laquintano 2018, pp. 113, 128), sometimes numbering in the hundreds of thousands, the platforms themselves serving as a proving ground for a writer’s work to potential publishers (Laquintano 2018, p. 105). However, fan writers have no hope of ever having their work traditionally published. Fanfiction, by its very nature, cannot be traditionally published. In appropriating already-existing intellectual properties, it is illegal to do so.

So, when I first learned of the online print-on-demand (POD) service Lulu and felt the urge to self-publish my fanfiction, it was a dangerous urge, precisely because of this illegality. At the time, in the mid-2000s, I was only peripherally aware of this. Now, I am acutely aware. I know I am risking potentially negative consequences in admitting that I am self-publishing print fanfiction. It does not matter that I receive no profit from doing so—on the one hand, Lulu most certainly is making a profit, and on the other, in publishing works that use existing intellectual properties, I am breaking Lulu’s terms of service. I struggle with this not merely as an otherwise law-abiding and law-respecting citizen, but also because I work closely with books and copyright law (I am a librarian), and the publication of my fic in print is fundamentally antithetical to my identity as an information professional. My professional identity puts me in a position of responsibility and privilege in relation to the patrons that I serve, and thus, on a moral level, I am put in the quandary of not being able to ‘practice what I preach’. I am also aware that many fans may frown upon this practice—monetising or commodifying fanfiction is still deeply taboo within the fan community (Jones 2014; Coker 2017), and publishing and selling one’s own fic, even if not for profit, can be seen as problematic.

These are confronting aspects of myself that I relate here with the aim of challenging what Monaco (2010) calls “defensive strategies” (p. 125) and the desire to conceal. While it is difficult for me to reconcile these parts of my professional and fannish practice and while I am discomfited by the fragility of this position, I am choosing to take the risk of negative consequences by speaking about this because I believe this practice has important insight to impart about the changing nature of authorship, the materiality of the book, and literary practice, particularly within fandom. In this, I also realise that I am potentially bringing unwanted attention to similar practices of other fans who may not wish to be scrutinised. I do not take this lightly, and again, as a scholar I am put in a tremendous position of power over other fans who engage in those similar practices, yet who may not wish for me to speak for them. Therefore, I choose not to reference the work or practice of other fans, but only my own.

5. Why (Did I) Self-Publish?

It was in 2008 that I first discovered Lulu. I had recently completed the first book in a trilogy called House of Cards, an alternate universe (AU) X-Men fanfiction. It was well-received by the small fan community I was in, and I was proud of it. For the first time in my life as a creative writer, I felt I had said what I had wanted to say with a piece of fiction. I had poured my heart and soul into it, and readers had responded well to this thing that I had made. It was fanfiction. To the outside world, it was any combination of low-brow, unoriginal, a waste of time, evidence of a pathology, deviant, erotic, trash. But, nevertheless, I wanted to (self-)publish it. Hence, I went through the motions of making my book appear like any other shelf-ready paperback—I formatted and typeset House of Cards; I added illustrations, created my own cover, uploaded the PDF file, and let the manufacturer take care of the rest. It is important to note that I did not put the book up for general sale. My only intention was to have a copy for myself, not for potential readers. I set the publication to private and the profits to USD 0. I bought a copy of my own fanfiction-as-book.

Why, if I already had a peripheral awareness that what I was doing was potentially illegal, did I still want to self-publish my fic?

Academia has little to nothing to say about why the fanfic author wants to self-publish in print. It is silent on why they desire their work to be instantiated in physical format. I have recently read the excellent works of Buchsbaum (2022) and Kennedy (2022), and while they give detailed and fascinating insight into why readers want to print and bind fanfiction, they do not give many clues as to why or how authors print and bind their own fanfiction.

Did I do it because I lacked a voice, because I wanted my voice to be heard? Was it because of my intersectional identity; did I feel a pressure, a responsibility for people like myself to be understood? Was it, as Gillam (2018, p. 113) advances, to use publication as a way to highlight trauma, to commiserate with others? Was it to find my book in the hands of readers, on the shelves of the bookstore and library? No. I had already found a readership; I had already had my voice heard. I was able to discuss my stories, my process, my inspiration freely with like-minded readers. I had even made close, meaningful, lasting friendships with some of them. By the time I decided to self-publish my fic, I had had all that for many years already. The traditional dream of the self-publishing author—to be seen, to be heard, to have their work disseminated—had already been accomplished for me. When I did publish, it was first for myself—for my book collection, for my own satisfaction. It was first the aesthetic choice of a bibliophile, of someone who loved the book, who loved collecting them. I was less concerned with the concept of the book as art/craft, than with the culturally ingrained concept of the book as ‘authentic’ in its ‘bookness’—that is, the book as a commodity that is published through traditional means and bought in a bookstore. My belief in the pre-eminence of the codex as the receptacle of the story outweighed the apparent shame and risk of self-publication, as well as the potential disapprobation of my fannish peers. Lulu gave me an opportunity I thought I would never get–a chance to properly self-publish, to publish something that looked, acted, and felt like a traditionally published book. If it was illegal, then I was banking on being a needle in a haystack that would never get caught.

However, within the fan community, I am far from being the only one who has the drive to collect print fanfiction. In the past, I had printed out fics from my favourite authors and bound them in folders—I was astonished when, much later, I saw the beautiful printouts and bindings other readers had created of their own favourite fics on Tumblr (Tumblr n.d.). They, too, had loved fic enough to turn it into something physical that they could collect. Just as with my old Ms. Wiz books, the satisfaction of having the complete collection and reading something physical was still very much a part of my life, even if a whole swathe of my favourite literature—fanfiction—was, for all intents and purposes, classed as ‘digital only’. In printing them out, in adding them to my collection, I made them ‘real’, I made them ‘mine’. Collecting is an act “grounded in personal means and memories, whereby the process allows and enriches one’s personal sense of identity in the world” (Dillon 2019, p. 270), and it is intrinsic to the fan experience. Lincoln Geraghty (2014) signs off his book, Cult Collectors, with the earnest assertion that “to be a collector is to be a fan, and to be a fan is to build a collection of objects and memories that shows just what it means to be you” (p. 185). Fans print out, bind, and collect their favourite fics because those stories not only give them pleasure, but also evoke memories of a time and place in their fannish life. For the fan writer, for myself, this has a particular significance because formalising the words I wrote in physical form is an act of memorialising exactly “what it means to be me”. It is a memento of my own artistic achievement, of my creative journey. In the act of self-publishing my work, I am essentially collecting myself.

Some might characterise the desire to own a book of one’s own fan writing as fetishising that work. This is problematic because it presupposes that to want a physical instantiation of one’s own work, outside of the traditional and socially approved structures of publication, is a fetishistic one. Is my desire to see my original fiction in print fetishistic? Does an established author fetishise their own work when they desire to own a published copy of it? Does the same hold for any creator? If we concede that it is natural that any creator should desire their work to be formalised and fixed in some physical, finished, and tangible form, then why is it any different for fan writers? If there is any fetishisation here, it is perhaps of the book itself–its materiality, its ‘thereness’, its presence, its irrevocability as the culturally designated final form of the writing process. As the dress is to the (hobbyist) fashion designer, as the Blu-Ray is to the (independent) film maker, so the book is to the (fan) writer.

6. The Problem with POD

“Autoethnography,” Hills says, “seems to strike at the heart of contemporary neoliberal academic research” (2021, p. 144), and autoethnography within fan studies can challenge the idea of fandom as being enslaved and “reduced to corporate, neoliberal ‘media time’” (Hills 2021, p. 149) by highlighting the rich, lived experiences of fans. Despite this, and despite all I have related here of my own experience, my fannish self is still inured to this corporate, neoliberal world. Self-publishing via POD is a particular site where my fannish self and neoliberalism clash, and which I address here.

Self-publishing fic via POD is an odd beast—where fanfiction has so often been viewed through the lens of art as resistance and dissent, POD fanfiction stands rather awkwardly. It is an irony not lost on me that while the practice of creating fanzines (and now fanbinding) is deeply intertwined with the free DIY culture espoused by Lawrence Lessig (2004), POD fanfiction is inured in what might be considered its opposite—the neoliberal culture of modern late-stage capitalism. It is only through the service-oriented structures of mass production that POD has become available at all, part of the New Economy driven by the digital technologies that got my dad his first laptop and myself the means to drop the pen that gave me RSI and type up my manuscripts. The ability to self-publish with such ease turns the act of writing into an act of customer service: “The author acts as servant, server, and service provider,” says McGurl (2016, p. 453), “and the reader as consumer, yes, but more precisely as customer” [original italics]. Though McGurl here is talking specifically of Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing arm, Lulu is also part of this post-industrial, neoliberal service economy, one of the many (self-)publishing outlets that implement the Ingram distribution platform, a service that is used even by large publishing houses to disseminate back catalogue publications (Cutler 2015). It is with unease that I recognise that I and other self-publishing fic writers who use POD are both servants (to our ‘customers’ or readers) and customers ourselves (of the publisher’s services). I am in the position—potentially—of both exploiting and being exploited by the New Economy. McGurl insists that I, as writer and self-publisher, am fettered by the rules and whims of the service provider (pp. 455–56), yet also by the whims of my “reader as customer, a quasi deity around whose needs […my] creative labor must revolve” (p. 457).

While naturally I am discomfited by the notion of being a cog in the proverbial machine, I would posit that this is a rather simplistic view with regard to writers of transformative works such as fanfiction or other works that are unlikely to ever see publication in their original form. Upon first self-publishing House of Cards, I did not do so with a wider readership than myself in mind, since I already had that readership. The physical book itself was equal parts work of art, memento, trophy, and simply something to hold. The service Lulu provided was a uniquely personal one, a service I could not, at the time, find elsewhere. In this scenario, I ponder who is the exploiter and the exploited, when I was merely serving myself.

Of course, I cannot escape being a part of the neoliberal machine that the POD service industry entails, especially now that I am serving a customer base (who, however, have read my fic already, and simply want a print copy to add to their collections). I have the double discomfort of being a part of the commodification equation, whilst simultaneously breaking licensing laws; while I subvert the system by making no profit, Lulu happily takes its cut, and the machine continues grinding, irrespective of whether I subvert it in futile ways or not. I am still part of the system.

There are ways to look at self-publishing platforms such as Kindle Direct Publishing and Lulu that assuage my discomfort. Their modes of publication stand in stark contrast to the corporate mega-publishers who shut out opportunities for small market or outsider literature. Di Leo (2014) lauds both small presses and digital publishing services in the same breath, claiming them as sites of “aesthetic resistance” and “editorial heterogeneity”, where they can “provide unprecedented support and visibility to publications that might have otherwise gone unseen” (p. 233). Indeed, paradoxically, POD is a potential means of effectively dismantling the large corporate publishers by cutting off the source of their supply chain–the authors themselves. “So where can we look now for a reprieve from the machinations of the global corporate publishing machine?” asks Di Leo (2016, n.p.). “Oddly enough, it may be the very technologies that have opened up book production to the masses, namely ebook and POD technologies,” which give authors “the ability to have absolute control over the products of and profits from their artistry.”

Perhaps, this is a rather utopic vision. Millions of fringe authors such as myself, not publishing for profit or a wide readership, will not make much of a dent in the corporate publishing market. There would need to be a wide take-up of self-publishing platforms by well-established authors to affect that kind of change. But while this may be the case, sites such as Lulu have been taken up by authors and artists who exploit the cheap efficiency of POD in projects that are not driven by the desire for economic benefit or mass readership. Zines (Kopecká 2020), experimental literature (Bajohr 2020), experimental art (Cetto 2021, pp. 31–32), and crowd-sourced charity fanzines (from the author’s own collection) all use corporate-harnessed POD technologies to create works that resist, subvert, and sometimes outright criticise neoliberal capitalist ideologies. Yet, this does not happen in a vacuum of neutrality. Referring to zines, but also encompassing POD literature, Šima and Michela opine that while they “give space to marginalized voices, they are embedded in the dominant middle class milieu, because their creators benefit from privileged access to information and technologies, usually have relatively high social and cultural capital, and have high cultural and social competences and entrepreneurship” (Šima and Michela 2020, p. 18) —a point that finds particular resonance with me and my own experience as an individual with both professional and academic power. The dual roles I hold within the system as both exploiter and exploited is an uneasy conundrum, and POD-publishing fic can only hold up a crooked mirror to my inability to step outside of either role. As Bajohr notes, “Instead of simply avoiding new technologies and their entanglement with capitalism, experimental POD literature hyper-reflexively exploits even its own disappointment in the inability to be unaffected by this technology/art/capital nexus” (2020, p. 84). I agree. Situated midway between McGurl’s pessimism and Di Leo’s utopianism, I feel that POD literature sits in an uncomfortable relationship with the neoliberal logic that has made the affordable mass production of self-published literature so achievable—it cannot exist without it; yet, it often stands in opposition to that neoliberal logic, engaging in a quiet revolution where profit does not matter, where a customer is not sought, where art is produced for art’s sake.

7. The Print Fanfiction Renaissance

I am reading Chelsea J. Murdock’s paper on her experiences of fanfiction as self-publication.

I am struck by the similarity of our positions. We are both academics, we are both writers of fanfiction. We both experience tension between those roles. Murdock grapples with self-publication as the antithesis of academic publishing, as inherently insignificant, ephemeral, and online, as an important part of her life as a writer that she cannot reconcile with her scholarly self. She frames fanfic as “an integral part of the meaning-making process for members of fan communities” (2017, p. 53), whereas, for the purposes of this autoethnography and reflection at least, I am framing it as an integral part of the meaning-making process for (and of) self.

“As I designed the pages and edited my chapters,” Murdock asks us, referring to her fanfic, “as I planned the release dates and prepared paratexts, was I “posting” and not “publishing”? Is this distinction only present because my works are hosted on online archives? Would this be different if my works were bound and could sit on your shelf?” (Murdock 2017, pp. 54–55).

This is exactly the question I have been posing to myself. Is there something inherently different between works that are digital and works that are physically bound? Is fanfic, is its context and its nature, bound to its format?

I want to push past this perception of fanfiction as fundamentally digital and online. I want to think outside the proverbial box of digital being the default format of fic. Murdock opines that if she wrote a fanzine, the perception of her fanfiction would be different, because it would be physical and tangible. But she fails to acknowledge the fact that for the great majority of the existence of fanfiction (as we conceptualise it today), fanzines were its default format. In fact, print fanfiction has a long and storied history, at least since the Sherlock Holmes parodies and pastiches that proliferated in the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, as so superbly summarised by Jamison (2013, pp. 43–45). These were largely privately printed and circulated, reproduced in periodicals such as the Baker Street Journal (which, interestingly, was early on threatened with copyright infringement by the Doyle estate—see Boström 2018, p. 258), or subjected to the venerable practice of ‘filing the serial numbers off’ for publication. Fanzines grew from this tradition, and Jacqueline Lichtenberg (2013) gives a wonderful retelling of the ‘collating parties’ she experienced in the 1970s, where groups of fans would raucously work side-by-side to put hundreds of zines together for distribution. Reading her chapter, the images of excited chatter punctuated by the shuffling of papers being proofread, of staplers thumping and boxes of printouts being dumped on the tables and floors, proliferate. Then, as now, much of fan endeavour was communal, collaborative, participatory. The fanzine, in many ways, was and is craftwork—collaborative craftwork—a hands-on DIY experience with the “rich semiotic potential of paper and binding” (Poletti 2020, p. 94). In Lichtenberg’s case, physical collaboration afforded quick and cheap mass production. In other cases, fanzines were lovingly crafted, had high production value, and were expensive collector items.

What is different between this type of publication and the POD fanfiction I produce? It is not so much the loneliness of POD fanfiction production and the lack of collaboration and camaraderie that went into (and still goes into) the making of the fanzine. It is also the way in which I am physically divorced from the production of my own work. Fanzine creation is intimate and visceral. It is in many ways, as I have posited, a craft. It is tangible creation. It is a communion with the “unrepentantly analog contraptions of paper, ink, cardboard, and glue”, with “books that have mass and odor, that fall into your hands when you ease them out of a bookcase and that make a thump when you put them down” (Houston 2016, p. XVI). Book creation via POD takes place behind the (computer) screen, behind the veil of an industrial manufacturing process you cannot see. This rupture between myself and the means of production gives the illusion of being a ‘real’ author, not the kind of author who writes a blog post, submits to a magazine, journal, or anthology or collaborates on a fanzine, but an author who sends her manuscript to a publisher with the lofty expectation that the unseen mechanics of production will transform her, chrysalis-like, into something special. Soon, she will be a published author, Laquintano’s “venerated social identity”, the vaunted figure who has the distinction of having her own book published in its own volume, in a format that looks like a traditionally published book should. POD makes the illusion real. I received my first print in the mail as I imagined any professional, well-established author would—with excitement, with pride that my story had been published at last.

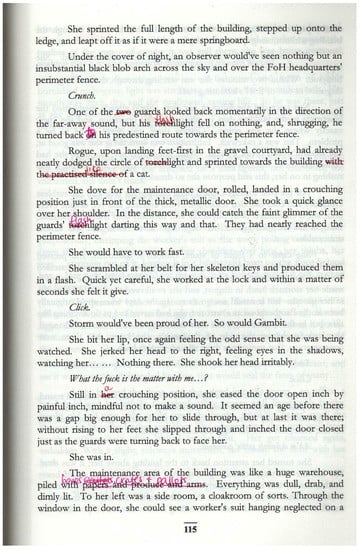

As time passed, I discovered that my readership wanted to have their own copies of House of Cards. Since I had first published it in 2008, my now-battered print copy had become a work-in-progress, as dynamic and protean as digital fanfic is, a new draft wherein I had corrected typos, crossed out chunks of superfluous text, or made copious edits (Figure 4). So, I created a whole new edition of the now ‘final version’ of the manuscript, created PDFs of parts two and three of the now-complete trilogy, and sent copies out as gifts to friends. If any readers wanted physical copies, I finally braved making them public on Lulu, so that they could be purchased. I received no profit from them–the fannish gift economy (Jones 2014) demanded it. Buyers would only pay for shipping and cost of production.

Figure 4.

Handwritten edits on the ‘first edition’ of House of Cards.

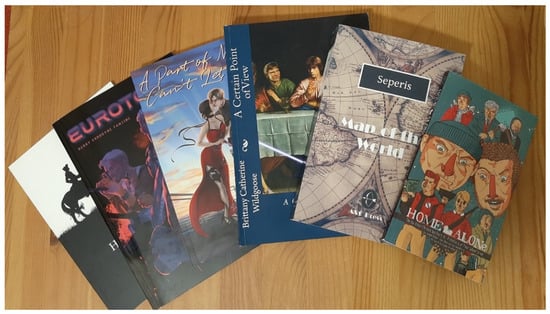

About the same time, in 2015, I found out that other fanfic authors were doing the same thing as me. If you know where to look, print fanfiction can readily be found for purchase. Where I had thought perhaps only a handful of authors would be doing as I had done back in the late 2000s, there was actually a plethora of them. I decided to start collecting them (Figure 5). They were of varying quality. Some were poorly written and formatted; some were wonderful pieces of art in their own right. Some had ISBNs and were being sold for profit; some were clearly personal or collaborative projects that were meant to be shared only among a certain fanbase. For the most part, they are POD books and not hand-bound custom volumes. They are made to be produced cheaply and quickly to order. Bajohr (2020) notes the “material poverty” of the POD book, something that “emphasises the anonymousness of its concepts, and its problematization of authorship” (p.85). Bajohr focuses on POD as a tool for reproducing experimental literature, literature that is rooted in the digital and plays on the borders of art and the literary, that destabilises the traditional notion of the author. While Bajohr does not speak of fanfiction in his piece, his words are nevertheless apt descriptors for it. The author of fanfiction holds a problematic status, a shameful one, as someone who appropriates the work of others to write ‘low-brow, deviant trash’. As transformative works, as something that is ‘made’ rather than simply ‘written’ (as Murdock frames it), fanfiction is both literary and artistic, both experimental and ludic. Fans, as always, are using technology to play with fandom in creative ways. Fanfic authors are using POD to bring their stories to physical, tangible life. Interestingly, fanzines—once xeroxed, collated, and mailed out to fellow fans and/or sold on the convention circuit—are now being collaboratively put together and printed using POD. They do not look the way we remember fanzines—they have evolved into something slick and polished and perfectly typeset. While they do not immediately evoke the hands-on, DIY crafted volumes that Lichtenberg’s ‘collating parties’ communally put together, their authors identify them as fanzines nonetheless.

Figure 5.

A selection of volumes from the author’s collection of POD-published fiction and fanzines.

Despite the ‘material poverty’ of POD (the thin film adhered to the cover of the original print of House of Cards has long been peeling off), it is fuelling a renaissance of fanfiction as an analogue format. It is giving fanfiction authors a chance to feel and touch and hold their own work, to bear the physical fruits of their labour. It gives them a chance to also possess a memento of self, of their own artistic achievements.

8. The (Fanfic) Author as Self-Publisher

The central question of this thesis is a simple one: why do fans self-publish their fanfiction in book format?

Through the perspective of self and the memory work undertaken in this autoethnography, I propose five potential answers to this question.

First, on an entirely practical level, as a fanfiction writer, I know my writing will never be ‘properly’ published. As mentioned above, because of fanfiction’s nature–using copyrighted characters and worlds—publication is out of the question, unless I ‘file the serial numbers off’, in the vein of Fifty Shades of Gray or the Mortal Instruments series. But the nature of my trilogy was so intertwined with the fantastical world of the X-Men that this was not a possibility without rewriting the story completely into something unrecognisable. The story was so personal to me that I could not envision it without its ‘serial numbers’. If I wanted to physically hold my story, I could do it without changing the story into something it was not, without having to go through the mainstream publication route, without having to face the certainty it would be rejected. I could just make it myself.

Secondly, I harken back to the old fanfictions I wrote in those exercise books—newly found, I see now how influenced I was by the pre-eminence of the codex as the format which bestows ‘thingness’ upon the story. When I excitedly received my physical copy of House of Cards, it was suddenly, somehow, real. No longer simply an ephemeral collection of 1’s and 0’s on the fickle and fluid internet, my story was tangible and touchable, and its ‘thingness’ inaugurated it into the physical realm of ‘the novel’. It only existed as a copy of one; it had no ISBN; it had no catalogue entry; it was not available in bookstores; it would never be seen by anyone but me. But it had been born into the physical world and it was on my shelf. It stood amongst other traditionally published books and looked just like them. It replicated the book as I had known and experienced it to this point. I had been privileged enough in my childhood to be able to afford books and to be inculcated into the systems of power and prestige they inhabit and represent. I cannot deny the influence that that power holds over me; indeed, that it holds over our culture at large. Despite Laquintano’s contention that we are moving towards a writer-orientated society, as opposed to a reader-oriented society, we still live in a world where “authorship holds more power” than the reader (Laquintano 2018, p. 39); it is in the corporate presses’ interests to keep it so. Having one’s book published, even if it is only a single, lonely volume, gives one power. It inaugurates the author into well-established systems of prestige. It also conveys a sense of immortality. In being published, my work was now fixed in time and space, and thus immortal, as long as I took care to take care of it. I knew how to take care of my books—I could not trust the internet to take care of my digital fiction for me. After all, who knows “how, in 500 years, surviving digital books will be accessed and made available” (Archer and Day 2017, p. 6). Material permanence is still valourised in a world belabouredly coming to grips with the dynamic, fluid, and impermanent internet.

Thirdly, the materiality of the book is still a powerful signifier of the self as reader/writer. The presence of the book itself codifies who we are as individuals (so many of the people I have Zoom calls or meetings with during the current COVID-19 pandemic sit in front of their bookshelves or choose virtual backgrounds with bookshelves. “The book’s thingness—or thereness,” says Jessica Pressman (2020, p. 63), “has become more desirable in the age of digitization, e-readers, and cloud-based storage libraries. Over the last millennium, the book’s thereness allowed us to build bookish identities around our nearness to it.” The fetishisation of the book is perhaps more noticeable in the digital age, but it is also tied to the sensual pleasures that the codex affords—the haptic feedback the body receives when touching the pages, leafing through them, or holding the weight of the book in one’s hands. “In its three-dimensionality, the materiality of the book conveys supplementary sensual experiences that cannot be conveyed by digital files alone” (Thurmann-Jajes 2021, p. 411). The book is not merely signified by the format of its contents, but by its three-dimensional structure. A book is a collection of sheets of paper bound together between covers. This is an ontological fact. The ‘thereness’ of my book, on its shelf, signifies its ‘thingness’, its transmutation from an indefinable collection of words and sentences in some abstract ether, to a solid denizen of our material world.

Fourthly—and also relatedly—books are, or can be, collectible items. Much of fan practice is built upon the collection of fan objects—toys, figurines, comics, memorabilia, autographs, posters, and so on. All these are physical; but fanfiction, mostly born digital these days, is no exception. After all, I collected fanfic too, as do many other fans. I printed out my favourite ones and kept them together on my shelf. My own fanfiction was part of this ecosystem of fandom collectibles, and I wanted to add it to my physical collection of other fannish paraphernalia.

But—and this is my final point—collecting the accoutrements of fandom is also an act of collecting self. “[T]he memories inscribed onto each object in the collection are defined by certain experiences in the collector’s life,” says Lincoln Geraghty (2014, p. 181). This is perhaps especially so for the author of fanfiction. I cannot, of course, speak for all authors, but for myself my self-published fanfictions are objects which are defined by the memories and experiences within my own life. Despite the identity of the professional, published literary author becoming more diffuse in the digital age, where everyone can be a writer, the power of that status still has an indelible hold upon me. My childhood, my father bequeathing unto me the love of the book, of storytelling—they taught me to both revere and strive for that elusive status. In a childhood where I was often powerless, where I was often othered by my peers, the voice of the author was the only one I had. Writing became inextricably intertwined with my identity, with who I was and am.

In self-publishing my fanfiction, I am both author and collector of self.

9. Conclusions

Susan Stewart speaks of the “deliberate and artificial split” between the “book as meaning versus book as object; book as idea versus book as material” (Stewart 1992, p. 33). In a digital era where the book as material object has been so divorced from its content, particularly for outsider literature such as fanfiction, it would seem that this split has been made complete. Yet my own experience, related here, implies that the book as both meaning and as object is still a powerful concept. I am still drawn to instantiate my immaterial, digital writing (‘meaning’) in physical form (‘object’). I still believe that fanfiction deserves to be held and so do the many fan binders and printers who also instantiate and collect fic in book format.

While I can only speak to my own motivations for engaging in this practice–one admittedly “constructed”, “drawn from memory” (Garner 2018, p. 104), and therefore necessarily fallible—what I nevertheless posit here may give some intimation as to why other authors of fanfiction might want to self-publish their own work. In terms of LIS, the fan writer as self-publisher challenges presuppositions about how people publish in the digital information society. Within the field, there is the wide assumption, not necessarily unreasonable, that fanfiction is inherently digital in form, too numerous, ephemeral, and low-quality to be worth collecting or preserving (Price and Robinson 2017); yet, fans are beginning to move their publishing practice from the strictly digital to the physical once more, some turning to POD services to achieve this and often flouting copyright laws in doing so. This points to the continued importance of the book even in communities whose practice is entrenched in digital spaces. It also reifies the notion that books as physical and collectible objects afford sensual pleasures that cannot be experienced through digital devices and screens. It might hearten the librarian to know that even in the heart of digital online communities, the book is not dead, although it is worth further investigating what this means for copyright law and its continued relevance in the future.

In terms of fan studies, along with fanbinding, fan self-publishing is also evidence of a significant move of fanfiction back into print formats—a renaissance of print fanfiction. This brings up questions around the contentious topic of the commodification and monetisation of fanworks, particularly fanfiction (see also Kennedy and Buchsbaum 2022 on this special issue). POD-published fic stands in a particularly awkward partnership with the neoliberal service economy, exemplified by sites such as Amazon and Lulu, in order to see publication realised. How this relationship will play out and how fan communities will respond to it in the future remains to be seen and studied. It is my hope that other authors and scholars explore this practice more in the future, engaging with other self-publishing fan writers, and investigating whether the phenomenon I describe here, based upon my own experience, is one that others share.

Overall, the self-publication of fanfiction by fan writers is a niche practice, but with the increasing accessibility of POD services, presumably it will continue to grow. This phenomenon has the potential to tell us more about the fan as author, as collector, and their relationship to their artistic self.

Lastly—this autoethnography should not be taken as complete. All autoethnographies, to some extent, are incomplete. Even as I write, my relationship with fandom changes as new writers take over the X-Men comics and my favourite characters evolve in ways that I am ambivalent to. So too does my relationship with the book, a format whose complexities I have learned to appreciate more as my professional responsibilities as a librarian have developed and matured. Memory work never really ‘ends’, and autoethnography should always “seek to keep its narrative open and invite further questions” (Monaco 2010, p. 134). What I write here can and should be interrogated; any defensive strategies I have subconsciously left unchallenged—strategies of concealment or reluctance to engage in introspection—should continue to be questioned, both by myself and the reader. What I hope is that this work helps to open up a dialogue, a doorway unto further ‘multilived’ autoethnographies (Hills 2021), where others can add their experiences, their selves, to the wider cultural narrative of the fan writer, the self-publisher, the bibliophile.

“We learn to see ourselves in books,” says Jessica Pressman (2020, p. 32), “and to understand ourselves through interactions with them. We are interpellated into becoming selves and subjects through books.” We are interpellated into becoming selves and subjects when we write them too, and when we print them, when we hold and look at them, it is into the mirror of self that we peer.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the reviewers of this paper for their inestimable help in completing this work. Their sensitive comments and excellent recommendations were immensely valuable and much appreciated. Many thanks also goes to Esther Lin for her support and reading of the original draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Throughout this paper, I will use the synonymous terms ‘fanfiction’, ‘fanfic’, and ‘fic’ interchangeably. The term itself refers to fiction written using characters and worlds from already existing fictional worlds or real-life people. |

References

- Archer, Caroline, and Matthew Day. 2017. From codex to computer. Book 2.0 7: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajohr, Hannes. 2020. Infrathin platforms: Print on demand as auto-factography. In Book Presence in a Digital Age, Paperback ed. Edited by Kiene B. Wurth, Kári Driscoll and Jessica Pressman. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, Paul. 2015. Playing Fans: Negotiating Fandom and Media in the Digital Age. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boström, Mattias. 2018. From Holmes to Sherlock: The Story of the Men and Women Who Created an Icon. New York: The Mysterious Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Jana, Bruce Fulton, and Mary Helm. 2009. Shifting Boundaries of Book Authorship, Publishing, Discovery, and Audience in an I-Society: Authors as their Own Publishers: An Empirical Study. Paper presented at the iConference 2009: iSociety: Research, Education, Engagement, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, February 8–11; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2142/15226 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Buchsbaum, Shira Bélen. 2022. Binding fan fiction and reexamining book production models. Transformative Works and Cultures 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetto, Sara. 2021. Post-Digital Printing: Exploring the Relation between Print and Digital Publishing. Master’s thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10451/51765 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Coker, Catherine. 2017. The margins of print? Fan fiction as book history. Transformative Works and Cultures 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Robin. 2015. Ingram and Independent Publishing. In Self-Publishing and Collection Development: Opportunities and Challenges for Libraries. Edited by Robert P. Holley. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leo, Jeffrey R. 2014. Neoliberalism in publishing: A prolegomenon. In Capital at the Brink: Overcoming the Destructive Legacies of Neoliberalism. Edited by Jeffrey R. Di Leo and Uppinder Mehan. Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, pp. 215–39. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leo, Jeffrey R. 2016. Who’s Afraid of Self-Publishing? Notre Dame Review 41 (Winter/Spring). Available online: https://ndreview.nd.edu/assets/187982/who_s_afraid_of_self_publishing_web_version.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Dilevko, Julis, and Keren Dali. 2006. The self-publishing phenomenon and libraries. Library & Information Science Research 28: 208–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, Andre. 2019. Collecting as Routine Human Behavior: Personal Identity and Control in the Material and Digital World. Information & Culture: A Journal of History 54: 255–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, Simone, and Bethan Jones. 2016. Love Me For A Reason: An Auto-ethnographic Account of Boyzone Fandom. IASPM Journal 11: 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dworkin, Craig, Simon Morris, and Nick Thurston. 2012. Do or DIY. York: Information as Material. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research 36: 273–290. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23032294 (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Evans, Adrienne, and Mafalda Stasi. 2014. Desperately seeking methodology: New directions in fan studies research. Participations 11: 4–23. Available online: https://www.participations.org/Volume%2011/Issue%202/2.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Garner, Ross. 2018. Not My Lifeblood: Autoethnography, Affective Fluctuations and Popular Music Antifandom. In A Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies. Edited by Paul Booth. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty, Lincoln. 2014. Cult Collectors: Nostalgia, Fandom and Collecting Popular Culture. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gillam, Tony. 2018. Creative Writing, Literature, Storytelling and Mental Health Practice. In Creativity, Wellbeing and Mental Health Practice. Palgrave Studies in Creativity and Culture. Edited by Tony Gillam. Cham: Palgrave Pivot, pp. 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, Matt. 2002. Fan Cultures. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, Matt. 2021. Fan Studies’ Autoethnography: A Method for Self-Learning and Limit-Testing in Neoliberal Times? In A Fan Studies Primer: Method, Research, Ethics. Edited by Paul Booth and Rebecca Williams. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, pp. 143–60. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, Keith. 2016. The Book: A Cover-to-Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of our Time. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Jamison, Anne. 2013. Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking over the World. Dallas: Smart Pop. [Google Scholar]

- Jenson, Joli. 1992. Fandom as Pathology: The Consequences of Characterization. In The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media. Edited by Lisa A. Lewis. London: Routledge, pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Bethan. 2014. Fifty shades of exploitation: Fan labor and Fifty Shades of Grey. Transformative Works and Cultures 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Kimberly. 2022. Fan binding as a method of fan work preservation. Transformative Works and Cultures 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Kimberly, and Shira Buchsbaum. 2022. Reframing Monetization: Compensatory Practices and Generating a Hybrid Economy in Fanbinding Commissions. Humanities 11: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecká, Mahulena. 2020. The anarcho-feminist zine “Bloody Mary” and the influence of the Internet: The problem with the hierarchy of the collective creative process. Forum Historiae 14: 126–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlthau, Carol C. 1991. Inside the search process: Information seeking from the user’s perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 45: 361–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laquintano, Timothy. 2018. Mass Authorship and the Rise of Self-Publishing. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawal, Vicki, and Connie Bitso. 2020. Autoethnography in Information Science research: A transformative generation and sharing of knowledge or a fallacy? In Handbook of Research on Connecting Research Methods for Information Science Research. Edited by Patrick Ngulube. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 114–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessig, Lawrence. 2004. Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg, Jacqueline. 2013. Recollections of a Collating Party. In Fic: Why Fanfiction is Taking Over the World. Dallas: Smart Pop, pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, George E., and Micheal M. J. Fischer. 1999. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences, 2nd ed. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- McGurl, Mark. 2016. Everything and Less: Fiction in the Age of Amazon. Modern Language Quarterly 77: 447–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, Jeannette. 2010. Memory work, autoethnography and the construction of a fan-ethnography. Participations 7: 102–42. Available online: https://www.participations.org/Volume%207/Issue%201/monaco.htm (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Murdock, Chelsea J. 2017. Making fanfic: The (academic) tensions of fan fiction as self-publication. Community Literacy Journal 12: 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, James W., and Janel D. Seagal. 1999. Forming a Story: The Health Benefits of Narrative. Journal of Clinical Psychology 55: 1243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, Anna. 2020. Genre and materiality: Autobiography and zines. In Book Presence in a Digital Age, Paperback ed. Edited by Kiene B. Wurth, Kári Driscoll and Jessica Pressman. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 90–108. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, Jessica. 2020. Bookishness: Loving Books in a Digital Age. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Ludi, and Lyn Robinson. 2017. Fan fiction in the library. Transformative Works and Cultures 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šima, Karel, and Miroslav Michela. 2020. Self-publishing and building glocal scenes: Between state socialism and neoliberal capitalism. Forum Historiae 14: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, Andrew C. 2002. Autoethnography: Self-Indulgence or Something More? In Ethnographically Speaking: Autoethnography, Literature, and Aesthetics. Edited by Arthur P. Bochner and Carolyn Ellis. New York: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Susan. 1992. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thurmann-Jajes, Anne. 2021. Jan van der Til: The hybrid artist’s book. In The Contemporary Small Press: Making Publishing Visible. Edited by Hildebrand-Schat Viola, Katarzyna Bazarnik and Christoph Benjamin Schulz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 411–21. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston, Nick. 2020. The Publishing Self: The Praxis of Self-Publishing in a Mediatised Era. In The Contemporary Small Press. Edited by Georgina Colby, Leigh Wilson and Kaja Marczewska. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 135–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tumblr. n.d. When the Author Deletes Your Favorite Fanfic. Available online: https://ihni.tumblr.com/post/172061304327/bugtongue-transformativeworks (accessed on 25 March 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).