Abstract

Black children have never been exempt from the violence and abuse that have beset Black adults. Any comprehensive attention to and understanding of systemic racism, anti-Blackness, and intergenerational Black trauma must consider the historical violence literally, representationally, and fictionally against Black children and youth. For each news story headline about violence against Black children, there is a comparable Black adult story, underscoring the interchangeability of Black adult and Black children subjected to racial violence. This essay is not a history of violence against Black children in literature but, rather, an effort to understand and demonstrate that Black children’s lives have not always mattered and that to address true racial justice in this country, systemic assaults on Black children and, by extension, on Black children’s families and communities, must be included in any justice conversation and work. This essay looks at representative children’s literature that normalizes violence against Black children.

Pretty eyes. Pretty blue eyes. Big blue pretty eyes.

Run, Jip, run. Jip runs, Alice runs. Alice has blue eyes.

Jerry has blue eyes. Jerry runs. Alice runs. They run

with their blue eyes. Four blue eyes. Four pretty

blue eyes. Blue-sky eyes. Blue-like Mrs. Forrest’s

blue blouse eyes. Morning-glory-blue-eyes.

Alice-and-Jerry-blue-storybook-eyes.

Each night, without fail, she prayed for the blue eyes. Fervently, for a year she had prayed. Although somewhat discouraged, she was not without hope. To have something as wonderful as that would take a long, long time.

Thrown, in this way, into the binding conviction that only a miracle could relieve her, she would never know her beauty. She would see only what there was to see: the eyes of other people.—Morrison (1970) The Bluest Eye (p. 40).

1. Introduction: Abusing as Schooling

In the September 1918 issue of The Crisis, Walter F. White, Assistant Secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Brooks and Lowndes Counties, Georgia, describes the lynching of Mary Turner, who had spoken out against the lynching of her husband the day before:

In February 2013, as a Delta Airlines flight descended to land, a sixty-year-old white man, agitated by the child crying next to him, turned to the little boy’s white mother, called the toddler the Nword, and slapped him:At the time she was lynched, Mary Turner was in her eighth month of pregnancy. The delicate state of her health, one month or less previous to delivery, may be imagined, but this fact had no effect on the tender feelings of the mob. Her ankles were tied together, and she was hung to the tree, head downward. Gasoline and oil from the automobiles were thrown on her clothing and while she writhed in agony and the mob howled in glee, a match was applied and her clothes burned from her person. When this had been done and while she was yet alive, a knife, evidently one such as is used in splitting hogs, was taken and the woman’s abdomen was cut open, the unborn babe falling from her womb to the ground. The infant, prematurely born, gave two feeble cries and then its head was crushed by a member of the mob with his heel. Hundreds of bullets were then fired into the body of the woman, now mercifully dead, and the work was over.(White 1918, p. 222; see also The Mary Turner Project 2021).

The white man was charged with simple assault and later fired from his executive job (Thornton 2013). In August 2020, a white woman slapped an eleven-year-old Black child and called him the Nword because his go-kart accidentally hit hers: “At Boomers, an entertainment center in Boca Raton, last weekend, Haley Zager, 30, took umbrage when a young Black boy bumped her car at a go-kart track. Angry that the little boy didn’t apologize, Zager slapped him in the face while calling him a n*****” (Thornton 2020). In February 2021, a nine-year-old Black girl was handcuffed and pepper sprayed by police because of their upset at her distress witnessing her father’s unpleasant encounter with them:As the plane began its descent into Atlanta, the boy began to cry because of the altitude change and his mother tried to soothe him. Then Hundley, who was seated next to the mother and son, allegedly told her to “shut that (N-word) baby up.” Hundley then turned around and slapped the child in the face with an open hand, which caused him to scream even louder, an FBI affidavit said. The boy suffered a scratch below his right eye. Other passengers on the plane assisted Bennett [the mother], and one of them heard the slur and witnessed the alleged assault, the affidavit said.(Ward and Martinez 2013)

These incidents and so many others underscore the reality that Black children have never been exempt from the violence and abuse that have beset Black adults. Any comprehensive attention to and understanding of systemic racism, anti-Blackness, and intergenerational Black trauma, then, must consider this historical and contemporary violence literally, representationally, and fictionally against Black children and youth. This essay is not a history of violence against Black children; it is, rather, an effort to understand and demonstrate that Black children’s lives have not always mattered and that to address true racial justice in this country, systemic assaults on Black children—including representational assaults in literature—and, by extension, on Black children’s families and communities, must be included in any justice conversation and work.The 9-year-old Black girl sat handcuffed in the backseat of a police car, distraught and crying for her father as the white officers grew increasingly impatient while they tried to wrangle her fully into the vehicle. “This is your last chance,” one officer warned. “Otherwise pepper spray is going in your eyeballs.” Less than 90 seconds later, the girl had been sprayed and was screaming, “Please, wipe my eyes! Wipe my eyes, please!” What started with a report of “family trouble” in Rochester, New York, and ended with police treating a fourth-grader like a crime suspect, has spurred outrage as the latest example of law enforcement mistreatment of Black people.(Hajela and Whitehurst 2021)

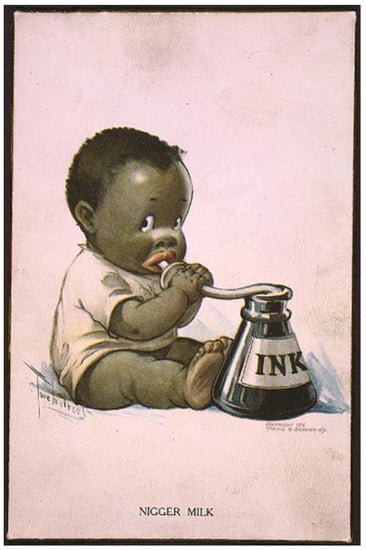

Representations of violence against Black children in children’s books further underscore the interchangeability of Black adults and children subjected to racial violence. The violence depicted is not just physical but is also represented through caricature, such as in Charles Twelvetrees’s (1916) “N***** MILK” calendar illustration that mocks Black children’s alleged minstrelsy-colored skin hue (Figure 1) (Getty Images 2021). This “n***** milk” joke became a popular gag in 1920s cartoons.

Figure 1.

Charles Twelvetrees, “N***** MILK,” c. 1916 (Getty Images 2021).

2. Education and Learning What?

That schools and classrooms are safe spaces for every child is a myth. Indeed, the very texts that have taught youngsters to read and write have also misrepresented and assaulted the sensibilities of Black children, their Black families, and their Black communities. In endless ditties, rhymes, and picture books that saturated and helped to shape US and other societies’ cultural norms, Black children were a staple in the complex tapestry of adult racial politics, whether through outright American Blackface minstrelsy stereotyping or through depiction of dehumanizing physical threats to Black children and/or the Black adults in Black children’s lives. The following sampling of children’s picture books speaks to the devaluing of Black children’s lives and bodies.

Because of its immense and long-term popularity, Helen Bannerman’s (Bannerman 1899) The Story of Little Black Sambo tops any list about anti-Black violence and Black children’s trauma. In addition to the story’s myriad authorized and unauthorized editions, its popularity and ubiquity are attributed as well to the various formats in which it went on to appear, such as puzzles, games, and sound recordings.1 Despite the seemingly romanticized nostalgia for this little Black child who allegedly outwits three ferocious and threatening tigers to save himself, this story is really about a Black child’s fear, panic, physical violation (in the form of literally stripping him of his new clothes), desperation, and luck:

And poor Little Black Sambo went away crying, because the cruel Tigers had taken all his fine clothes.

For me, Little Black Sambo is no trickster, as too many nostalgic readers—especially non-Black readers—contend (Lester 2012). Bannerman has not written him as surviving because of his own mental and reasoning faculties, but rather on the fickleness of luck: the tigers are distracted by greed, chasing each other around a tree so frantically and frenziedly that they miraculously turn to butter. That three tigers threaten him on three different occasions during this encounter is nothing less than trauma. This Black child’s and his parents’ disparaging names—Sambo, Mumbo, and Jumbo—served to delight Bannerman’s young Scottish children as they traveled by train in India to visit their dad during Bannerman’s writing of this tortuous tale. Coupled with the problematic names and the narrative action itself are the Black minstrelsy features of the characters—the physical weight of parents Mumbo and Jumbo is either too fat or too thin (depending on the story version), and they wear mismatched bright-colored, clown-ish clothing. These characters’ dark black skin and exaggerated red smiling lips and Mumbo’s mammy attire, complete with bandanna and checkered dress, further mock and Other the Black characters. Little Black Sambo becomes more animal-like as he becomes more naked and scared, hiding behind a tree in the distance, while the tigers become more human, greedily fighting for each other’s clothing. While this book could have been a critique of colonialism and “civilization,” it is not. Instead, for many Black and white adults, it remains childhood nostalgia, with little to no acknowledgement of its imperialist objectification of people of color. The book jacket for what is hailed as “the only authorized American edition of The Story of Little Black Sambo written and illustrated by Helen Bannerman”2 furthers this glossing over of representation and misrepresentation:Presently he heard a horrible noise that sounded like “Gr-r-r-r-rrrrrrr,” and it got louder and louder. “Oh! dear!” said Little Black Sambo, “there are all the Tigers coming back to eat me up! What shall I do?”(Bannerman 1899, pp. 34–36)

This blurb is as problematic as the book, on many levels. First, Little Black Sambo does not “lose” his clothing as a result of his own childhood negligence, as the wording of “lost” might suggest. Clearly, this circumstance is different from Little Bo Peep who lost her sheep or the Three Little Kittens who lost their mittens. Furthering this Black child and Black family misrepresentation is the projecting of childhood excess and the gluttony of eating 169 pancakes, perhaps also suggesting an underlying hunger of massive proportion. The notion of a “common language,” in my reading, is the violence and threat of violence against Black children whose Black parents are neglectful, unaware, and ultimately unable to protect their Black child from wandering through a dangerous jungle. In Bannerman’s stories, and in US culture more widely, the violence associated with children being eaten alive by animals echoes the popular notion that the babies of enslaved persons were eaten by alligators, an image that appears on licorice candy, and of adults being chased up palm trees by alligators. Typically, animals eat other animals, so this representation equates Black bodies with animals (and not in the anti-speciesism way), leaving white people as humans whom animals would never consider eating. Bannerman (Bannerman 1899) wrote Little Black Sambo expressly to “amuse” her two little girls (“Preface”) at the expense of Black children.3The jolly and exciting tale of the little boy who lost his red coat and his blue trousers and his purple shoes but who was saved from the tigers to eat 169 pancakes for his supper, has been universally loved by generations of children…. Little Black Sambo is a book that speaks a common language of all nations, and has added more to the joy of little children than perhaps any other story. They love to hear it again and again; to read it to themselves; to act it out in their play.(Bannerman [1900] 1923, front cover jacket)

In direct contrast to the demeaning characterizations and deadly, dehumanizing situations in Little Black Sambo and many other stories with caricatured Black figures, Bannerman’s (1966) The Story of Little White Squibba, “completed and released by … Bannerman’s daughter, Day, twenty years after her mother’s death,” is about a little white girl—one of Bannerman’s few white characters4—who encounters and befriends a tiger, an alligator, an elephant, a mongoose, frogs, and a snake (The Story of Little White Squibba n.d.).5 While two of the animals threaten to eat her, the other animals join her on her adventures because “One day she had a birthday and all of her friends sent her books about little black children who had wonderful adventures in the Jungle” (Bannerman 1966, p. 8). The animals who take Little White Squibba’s jacket and scarf give these clothing items back to her, for various reasons, and by the story’s end, are now friends with Squibba: “And then presently [the animals] all reached Little Squibba’s home, and she said to her mother, ‘these are all friends of mine, and they’re never going to hurt children again. So, can we have tea now?’” (n.p.) A Black child is in mortal danger in Bannerman’s first book, while a white child assumes the role of a fairytale heroine in her last. The differences in treatment and representation of a white child and a Black child are miles apart in granting humanity to one but not to the Other.

Like the genocidal nursery rhyme “Ten Little Indians” (Winner 1868), “Ten Little N******” (Green 1869) teaches subtraction through violence against little Black boys (Opie and Opie [1951] 1997, pp. 387–88; see also Jennings 2018).6 As the counting backwards from ten to one commences to a gleeful sing-songiness, the boys disappear one by one: one boy chokes to death, one chops himself in half, one is stung to death by a bumble bee, another is swallowed by a fish, one is presumably hugged to death by a bear while at the zoo, and one just “frizzled up” in the sun. Furthermore, if they do not disappear because of violence, they disappear because they are lazy—one oversleeps and another is irresponsible (he stays late rather than leaving on time)—and the final boy marries, suggesting marriage is undesirable for Black folks. Appearing in publications from at least the mid-1800s through the 2010s, the verses are accompanied by Blackface images of the little boys. The “pickaninny” character, minstrelsy Blackface, and even the corresponding violent counting rhymes were also present in film from its beginnings. Consider Edison’s (1894) early kinetoscope (movie-like series of images) demo, The Pickaninnies, with young dance performers Walter Wilkins, Denny Tolliver, and Joe Rastus (British Film Institute (BFI) 2021). Edison (1908) also has a later counting-game-based short film Ten Pickaninnies [or The Pickaninnies]. In many more films, he and other early filmmakers capitalized on racist stereotypes and violence as humor:

Filmmakers continued this tradition in white action movies, with the “token” adult Black or other minoritized villain or hero eventually the character whom film audiences are trained to expect will die.African American children were subjected to violence in such films as The Gator and the Pickaninny.... Here a black child is swallowed by an alligator. While the father eventually saves his child, the image is truly frightening…. “Black children were often considered ‘disposable’”…. These films include such violence as children who “are knocked out, kidnapped, bee stung to death, shot, drowned, and eaten by an alligator.” The violence is “sadistic”….(Waterman 2021, p. 796)

Based on this early nursery rhyme, Nora Case’s (1907) Ten Little N***** Boys is a version that teaches addition.7 Ten Little N***** Boys—or Ten Little N***** Boys and Ten Little N***** Girls–went on to have numerous editions by publishers on both sides of the Atlantic, starting with Chatto & Windus 1907, as one of the Dumpy Books for Children (Bannerman’s (1899) The Story of Little Black Sambo is also a Dumpy Book), through 1962. In these addition scenarios, a boy helps another put on shoes, two boys save another from drowning, the children frolic in a watering hole, they save another from an aggressive lion, one is saved from being strangled by a snake, they show each other how to ice skate, they play jokes on each other, they chase chickens in a yard, and they are chastised for reasons unknown by their red-bandanna-adorned mom—figured as Mammy with heft, apron, bug eyes, and minstrel black skin. It is not clear how their playfulness makes them “naughty little n***** boys” (Case 1907, p. 28) at the section’s end. In this animal connection, even Nature perpetrates harm upon Black children.

The second half of Case’s (1907) Ten Little N***** Boys is about “Ten Little N***** Girls.” The Black girls section of this dual text teaches subtraction. Their Black girls’ numbers diminish when one goes to Paris, one disappears from doing a summersault on a gate, one chooses to leave the group on a trip to Devon, one is burned up while making toffee sticks, one is presumably stung to death by a honey bee, one abandons a task of floor cleaning for no specified reason, a giant bird steals one away, a polar bear at a zoo snatches and hugs another, and a fish eats one. The same trope of animals acting violently toward Black children resurfaces. While there are inconsistencies in both sections regarding the nature and degree of anti-Black violence, what is consistent are the children’s minstrel Blackface representations. The narratives paint pictures of Black boys and Black girls as careless, lazy, irresponsible, and generally insignificant; they have been created to amuse and entertain others at the cost of the Black children’s humanity and human dignity. Of further importance about these books with their problematic representations is that they are also physically small, meant to fit a little child’s hands—4.5 inches by 6 inches.

Also child-sized, Ten Little Pickaninnies (Brown 1900) is a 12-page paper booklet, volume 21 of The Faultless Starch Library that served as both advertisement for the popular starch and entertainment for children.8 Bushnell (2021) describes how, “In the mid-1890’s, Faultless embarked on an aggressive marketing campaign that involved the publishing of small books that came free with every box of Faultless starch. The Faultless Starch Library published 36 titles between 1896 and the mid-1930’s…. The booklets were a huge hit in Texas and the Indian Territories as they were used as primary readers and supplements to school texts. Many in rural areas learned to read using the Faultless booklets.” Children in urban and rural areas also “collected and traded the booklets…” (Davis 2005, p. 18). In the anti-Blackness style and content of Ten Little N***** Girls, Faultless’s Ten Little Pickaninnies depicts minstrelsy-style young Black girls with bicycle-spokes-sticking-from-their-heads plaits who engage in the following activities to teach subtraction to children:

The literal and metaphorical washing-the-black-off racist commercial advertising (a common trope in US visual history) further perpetuates the notion that Black girls, like their adult Black moms and aunts, are solely meant to serve as cleaners and domestics for white people. The poem/song mirrors the nonsensical minstrel songs in that there is no logic explaining the disappearance of the girls, one by one. Here, the violence takes the form of “pinning her nose fast,” “eating a cake of soap,” and quarreling and crying, with the culminating act of the last little Black girl disappearing altogether by turning “all over white.”Ten pickaninnies hanging washing on a line,One pinned her nose fast, and then there were nine.Nine pickaninnies scrubbing early and late.One ate a cake of soap, and then there were eight.Eight pickaninnies, quarrelling like eleven,One of them began to cry and then there were seven.Seven pickaninnies, tired of naughty tricks,One of them is pouting, so there are six.Six pickaninnies thought they’d take a drive.One got left behind, and then there were five.Five pickaninnies went to a grocery store,One ate a green apple—then there were four.Four pickaninnies buying Faultless Starch with glee,One got another sort, and then there were three.Three pickaninnies very weary grew,One threw her box away, and then there were two.Two pickaninnies, to use Faultless Starch began,One went away to rest, and then there was one.One pickaninny, when with Faultless Starch she’s done,Finds she’s turned all over white, so there were none.(Brown 1900, n.p.)

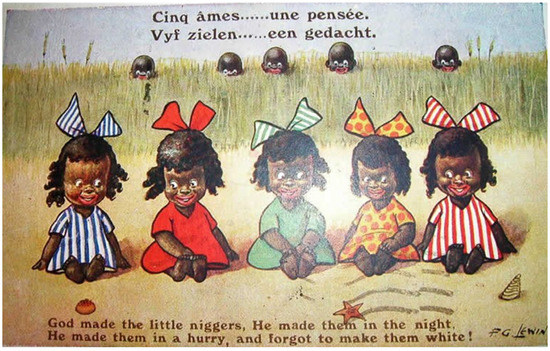

This notion of whiteness as an ideal and Blackness its antithesis is precisely the premise of Toni Morrison’s (1970) first novel, The Bluest Eye, the source of this essay’s epigraph, in which the “ugly” Black Pecola prays for blue eyes as a symbol of whiteness and its alleged goodness and perfection. The famous Mamie and Kenneth Clarke 1950s “Doll Test” provided data to show Black children’s positive bias toward white dolls over Black dolls that looked more like them with their brown skin (Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF) 2021).9 While this test has been updated from the 1950s, with more factors included, such as colorism, and with both white and Brown children asked the Doll Test questions, the results of all tests through the years is that white is right, better, and best, even with dolls. The starch ad, Morrison’s (1970) theme in The Bluest Eye, and the various iterations of the Doll Test all speak to another form of violence against Black children: the violence of absence, of nullified identity, and of self-contempt as foregrounded in this childhood verse: “God made the little n******, He made them in the night, /He made them in a hurry, and forgot to make them white!” (Figure 2) (Pinterest n.d.). The bilingualism (French [top line] and Dutch [bottom line] translation: “Five souls……one thought”), the Black minstrelsy back row, and the mischievous Black boys seemingly ready to pounce on the Black girls perpetuate the global anti-Black sentiments that prevail in Christianity and beyond English-speaking societies. Black children—like Black adults—are connected with criminality and mischief in this image as well.

Figure 2.

Caricature and familiar childhood verse (Lewin n.d.).

Lynda Graham’s (1939) Pinky Marie: The Story of Her Adventure with the Seven Bluebirds mocks a Black girl child because of her hair and non-white skin color. Violence and child trauma in this children’s book take the form of birds attacking and stealing the child’s ribbons while she sleeps. As in other stories, the Black child is linked with animals meant to do her harm, this time by violating her body in its most vulnerable state, during sleep. Pinky Marie has two Black parents whose names are meant to be funny and mocking, and even nonsensical for children, because their names are too many “white names” strung together, seemingly for importance. Additionally, Pinky Marie and her parents are not just Black; they are very Black:

By comparing Pinky Marie’s color to candy, the white author depicts Black children as edible treats, a trope that has also appeared much more recently. In a 1980s Conguitos (Spanish candy) commercial, a white child emulating Tarzan swings from a jungle tree and jokes with little personified marching African minstrelsy candies. The roughly translated voiceover says that “The candies taste good, and they make you big and strong” (Tokyvideo 2020).10 In another Conguitos ad entitled “Anuncio Conguitos Tribu Color,” the stereotypical animated candies are literally plucked from the jungle by white hands and eaten by white people (Chocolateclass 2015).Mr. Washington Jefferson Jackson was black. As black—as black—as black as INK. Mrs. Washington Jefferson Jackson was black, too. As black—as black—as NIGHT. And Mr. and Mrs. Washington Jefferson Jackson had a little girl. Her name was Pinky Marie Washington Jefferson Jackson. Oh! Oh! Oh! What a big, big name for such as a round roly-poly little girl. But she wasn’t black. Oh no! She was brown. As brown—as brown—as brown as a chocolate candy bar. And she looked good enough to eat.(Graham 1939, n.p.)

While the child in Pinky Marie is not minstrel Black, her parents are, and Pinky and her dad have “kinky black hair.” Her mom is adorned in the mammy trope bandanna: “And Mrs. Washington Jefferson Jackson had—well, you couldn’t tell what kind of hair she had. Maybe no hair at all, for she always wore a big red-and-white hanky tied around her head” (Graham 1939, n.p.). On the day of the story, Pinky Marie goes to town with her father. For this special outing, she wears a beautiful dress that is, like the jacket of her literary cousin Little Black Sambo, “just the color of the part of the watermelon that you eat” (n.p.), and her hair is in multiple “pickaninny pigtails” adorned with “beautiful, beautiful colored strings—pink and green and yellow and red and orange and blue and purple” (n.p.). These visual depictions of Black girl children are common and prevalent in similar textual representations, especially the multiple plaits poking from the child’s head as though they are bicycle wheel spokes. Punctuated with references to Pinky Marie’s parents as “Pappy” and “Mammy,” the story takes a violent turn during the journey to town when Pinky Marie falls asleep and a flock of “father” birds steals her beautiful hair strings to add a touch of color for their nests. Described thusly, the birds look down from their tree to see their target, the sleeping Pinky Marie:

The author’s sympathies lie with the birds in need of decorating their nests, not with this Black child whose physical and psychological trauma derive from this violent assault on her physical person:Then all the other birds looked down where the first father bird was looking and their bright, bright eyes sparkled too. “Yes, yes!” they twittered. “Yes, SOMETHING COLORED TO BRIGHTEN UP OUR NESTS!” For there, far below, slept Pinky Marie Washington Jefferson Jackson in her beautiful, beautiful dress and the beautiful, beautiful strings tying her kinky black hair.”(n.p.)

The assault—a metaphorical rape—reveals a few details that constitute specifically racialized trauma: this child is objectified as “SOMETHING COLORED,” a phrase not just referencing Pinky Marie’s string ribbons but her whole person; the pulling and tugging on her hair by multiple “father” birds with “sharp yellow bills” suggests violation by a group of (white) men who themselves have daughters but view Black women and girls as prey; and the little girl’s sleeping, as she awaits her father’s return back to their travel wagon, demonstrates her total vulnerability. Pinky Marie, like Little Black Sambo, is ambushed and left helpless and afraid:And without waiting a minute, the seven father birds swooped down, down, down, and each took the end of a beautiful string in his sharp yellow bill…. PULL! PULL! PULL! PULL! PULL! PULL! PULL! Away went the seven father birds with Pinky Marie’s beautiful strings in their bills. One father bird had a pink string; one had a green string; one had a yellow string; one had a red string; one had an orange string; one had a blue string; and one had a purple string.(n.p.)

Even in this moment of vulnerability, Graham, having created Pinky Marie as a living, hollow, chocolate candy sheep-girl, does not miss an opportunity to mock the little girl’s physical body—her size, shape, hair, and “big name,” a not-so-subtle nickname or rhythmic shorthand for “pickaninny,” all meant to mock and amuse. The narrative’s solution to this trauma is to give Pinky Marie a bandanna to wear, making her a younger embodiment of her Mammy mother: her Pappy “pulled out his big red-and-blue-and-green hanky and tied it around Pinky Marie’s scrumbled-scrambled, kinky, wooly head just like Mrs. Washington Jefferson Jackson tied hers. And then he said, ‘There you is, honey. You looks fine again’” (n.p.). The adult “father” birds’ violently forcing this young girl into womanhood is similar to the many narratives of the sexual and other types of “adultification” of Black girls in contemporary times (Campaign for Youth Justice 2020). What is clear is that this book—like The Story of Little Black Sambo (Bannerman 1899) and Ten Little N***** Boys and Ten Little N***** Girls (Case 1907)—does not acknowledge a Black child’s pain, fear, and suffering, thereby underscoring research data that shows white people generally, and medical professionals specifically, believe that Black people allegedly do not feel pain as do white people (National Public Radio (NPR) 2013; Swetlitz 2016). Hence, their pain and suffering can be easily denied, minimized, or ignored altogether.And down in in the wagon Pinky Marie Washington Jefferson Jackson woke up. And her head hurt just for a very little bit, so she put up her fat chocolate-colored hands to rub it and then, oh, my! Her big brown eyes grew bigger and bigger, for her pigtails were gone—her beautiful pink and green and yellow and red and orange and blue and purple Sunday School and going-to-town day strings were gone! And her kinky-curly black hair was blowing this way and that way in the soft gentle breeze. She didn’t look like a birthday cake, oh no! She looked just like—just like old Baa Black Sheep with his thick wool all scrumbled-scrambled up. Then Pinky Marie Washington Jefferson Jackson began to cry…. Pinky Marie was crying so she couldn’t say a word. She could only shake her kinky, wooly, chocolate head.(n.p.)

Similar familial caricatures are present in Blanche Seale Hunt’s (1945) Little Brown Koko Has Fun, which opens with mocking both the mother’s and the little boy’s physical persons: “Little Brown Koko’s nice, big, ole, good, fat, black Mammy went to town one afternoon and left him at home to keep the chickens scared out of the flower-beds. But before she left she took one of her big, fat, black fingers under Little Brown Koko’s little, flat, brown nose and said, ‘An’ mind, Little Brown Koko! Don’t you-all skeer up no mischief while I’s gone’” (p. 5). The scene is set for little Black child who has to be disciplined and subtly threatened. Whatever violence that might come this child’s way is therefore reasonable, expected, and ultimately justified. Indeed, whether Brown or Black, these children are cut from the same cloth as their adult parents.

Kate Gambold Dyer’s (1942) Turky Trott and the Black Santa, with illustrations by Janet Robson, seeks to be a more Black-affirming story but is undermined by the pedestrian, minstrelsy-black illustrations and the red bandanna-wearing Mammy character. Racially problematic illustrations also appear in Eva Knox Evans’s (1936) Jerome Anthony and in James Holding’s (1962) The Lazy Little Zulu, which depicts a Black African child as “lazy” because he enjoys experiencing Nature. Equally problematic because of the minstrel “Uncle Tom-ish” caricatures of Black adults and children is Bonte and Bonte’s ([1900] 1908) ABC in Dixie: A Plantation Alphabet. (Amazon (n.d.a) warns that this book’s “content may be considered offensive or racist,” describing it as an “early pictorial children’s reader, about learning to read, building proficiency, and enjoying good old fashion slapstick humor, featuring strictly people of color, Afrocentric. Black Americana.” Even when the narrative itself is not racialized, as in Maben’s (1943) Pickaninny, the naming of a little Black child as “Pickaninny” carries this generic disparagement that denies humanity and individual identity. Amazon (n.d.b) describes this book with absolutely no mention or acknowledgment of its problematic name itself: “A beautifully illustrated children’s book about little Pickaninny and his adventures with the handsome Mrs. Turtle.” This minstrelsy Black child image is most pronounced in Jean Robertson’s (1950) More Adventures of Little Black Nickum, with its exaggerated minstrelsy, mocking dialect, and Mammy and Poppa naming— modeled on Bannerman’s (1899) Little Black Sambo and Case’s (1907) Ten Little N***** Boys.

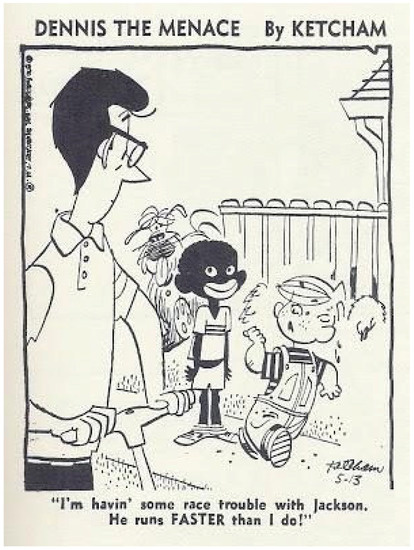

Decades later, the minstrelsy image of “Jackson” in the 13 May 1970, Dennis the Menace cartoon (Figure 3) that appeared in newspapers nationally, reveals Black children as a source of visual difference and racial humor, inhabiting the same political space as Black adults. Some editors rejected the cartoon, and some newspapers that ran it printed apologies for doing so after readers angrily protested. In his autobiography, Ketcham (1990) explains:

Shocked at the negative reactions, Ketcham apparently never came to understand why his Sambo-like initial representation of Jackson had been offensive, no matter his intentions (see also Mikkelson 2015).Back in the late 1960s when minorities were getting their dander up … I was determined to join the parade led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and introduce a black playmate to the Mitchell neighborhood. I named him Jackson and designed him in the tradition of Little Black Sambo…. He was cute as a button, and … would.… inject some humor into the extremely tense political climate…. The rumble [reader protests against the image] started in Detroit....The cancer quickly spread to other large cities.... I gave them a miniature Stepin Fetchit when they wanted a half-pint Harry Belafonte.(pp. 191–92)

Figure 3.

Hank Ketcham (1970) Dennis the Menace. Copyright permission obtained from Fantagraphics.

Not coincidentally, the pain and suffering of Black adults and Black children is reflected in the actual games white people played at the expense of Black folks. In these games, both Black children and Black adults were targets of objects tossed and thrown aggressively at them in order to score points. According to the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia’s (2014) short film Blacks as Targets,

Violence normalized in games and literature as education and entertainment is a direct reflection of a history of violence consistently directed at Black bodies in real life—all in the interest of maintaining white supremacy.Carnival games in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries highlighted and exploited white people’s hostility toward blacks. Presenting African Americans as willing victims of white aggression made the violence seem normal and legitimate. Games like The African Dodger, also known as Hit the N***** Baby or Hit the Coon, which used actual human targets, were commonplace in local fairs, carnivals, and circuses. Sometimes a picture or model of an African American was used instead, but the message was clear—unprovoked violent aggression toward blacks was the social norm.

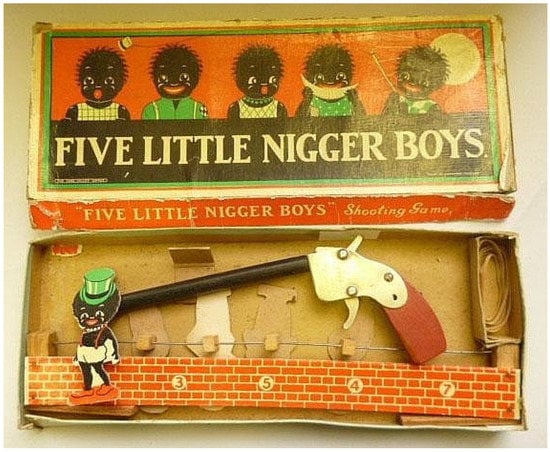

At least two 1950s board games by Chad Valley Company, Ltd. have as their objective to shoot Black children: Five Little N***** Boys (Chad Valley Company Ltd. 1950a) and Four Little N***** Boys (Chad Valley Company Ltd. 1950b) (see Figure 4). Both come with small stand-up figures to be shot down with toy rifles. On the box of the Four Little N***** Boys game are these words: “Five Little N***** Boys/Looking very sore/One of them was shot off/And then there were four.” Five Little N***** Boys is billed on the box as a “Shooting Game” (Windel 2016). In a recent realistic version of this shooting game, Miami Police reported in 2015 using the mug shot images of Black teens for target practice (Jordan 2016; Savransky and Rabin 2015). More than a century earlier, white soldiers in Tampa, Florida, resisting the 1898 temporary encampment of a company of Buffalo Soldiers en route to support Cubans under seizure by Spanish armies, used a Black child for target practice:

“It’s one of these ugly moments we cannot forget is part of our story,” said Fred Hearns, a historian of Tampa’s African American history. “Shooting at a black kid for target practice. Think about it. People supported that once”.… A white soldier from Ohio grabbed an African American toddler wearing a loose-fitting pajama gown. Holding the little boy upside down, the soldier announced a contest: Anyone who could shoot a hole through the child’s sleeve would be considered the top marksman. The target was hit; the child was unharmed.(Guzzo 2018)

Figure 4.

Chad Valley Company Ltd. (1950a) shooting game with Black children as targets.

In sharp contrast to Black children and youth as targets of white violence is the existence of Junior Shooters, an online and print journal representing an organization dedicated to training (apparently only white) children and youth in gun use and safety. According to the organization’s “About Us” page,

On the site’s “Get Involved” page, the organization states,Junior Shooters strives to be the first of its kind to promote juniors involved in all shooting disciplines online and in print. We care about kids and their parents and want you to have a place to go to find what is needed to get started in many different shooting venues. Questions are answered about safety, guns and gear, protective gear, events, organizations and more. Junior Shooters is dedicated to juniors of all ages and their parents….(Junior Shooters 2021)

That this site has no children of color pictured with guns underscores the parallel position of whites represented in these children’s books. In other words, just as the Black children become targets like Black adults, white children become the perpetrators of anti-Black violence like white adults.Junior Shooters strives to be the first of its kind to promote juniors involved in shooting and the many disciplines they are shooting, all in one publication. Junior shooters and their parents now have a publication they can go to and find what is needed to Get Started…. The premier issue of Junior Shooters, Volume 1, was published in August 2007 and is receiving an outstanding response! Junior Shooters is dedicated to juniors of all ages, but primarily from the age of eight to 21, depending upon the shooting sport. It will be published quarterly starting in 2008.(Junior Shooters 2021)

Denis Mercier (n.d.), in “From Hostility to Reverence: 100 Years of African-American Imagery in Games,” offers further commentary on violence against Black adults and children in game formatting:

Of all the American popular genres using African-American imagery, children’s games have been among the most uniformly negative….

These games were commonly paired with minstrelsy illustrations and representations, further denying Black people any semblance of basic humanity.Games of the late 19th and early 20th centuries reflected racial attitudes ranging from the benign to the aggressively violent. Although some of the games … stereotyped African Americans as comical entertainers, many revealed an intense white hostility towards Blacks. This hostility was legitimized, even celebrated, by making it appear as if Blacks depicted enjoyed the victimization to which the games subjected them. Many target games … portrayed the Black targets as smiling broadly. The unspoken message was that Blacks, unlike other [white] people, felt no pain, so players could indulge in and enjoy aggressive assault because no real pain was inflicted.

In Sara Cone Bryant’s (1907) Epaminondas and His Auntie, minstrel-like images of the Black child protagonist and his Mammy-trope “Auntie” and his mother are inhumane and grotesque, augmented by maternal verbal abuse and physical pain. While the story is about a Black child’s (in)ability to follow parental instructions, the narrative essentially becomes a journey into the humiliation of a Black child who does not understand adult instruction. This young child’s misunderstandings afford no empathy or compassion from the adults in the story and serve to amuse and entertain at a Black child’s expense. For instance, as Epaminondas is tasked by his “Auntie” with bringing cake to his mother, he smashes the cake in his hands in his efforts to carry it as instructed. When he arrives with the crumpled and crumbled cake, his mother responds with disdain and insult: “Epaminondas, you ain’t got the sense you was born with! That’s no way to carry cake. The way to carry cake is to wrap it all up nice in some leaves and put it in your hat, and put your hat on your head, and come along home” (Bryant 1907, p. 6). Rather than adults giving a task to him, then confirming that he fully understands the task as instructed, this Black child is the source of racist mythologies about Black folks’ innate intellectual inferiority, both Black children and Black adults. Notice that the explanation and task clarification come from the adult after the verbal assault and humiliation—all for a reader’s entertainment at this child’s expense. No responsibility is given to the adults engaging this young child in these tasks. When this child learns from each of the previous failures, he seeks to apply that learning to his next familial assignment—delivering butter to his mother, taking a new puppy home, and delivering a loaf of bread to his mother. With each task, however, comes the refrain that attacks his child illogic and unthinking, when he is actually interpreting his instructions quite literally. Such literal interpretations are lower-level skills that apparently, according to Bryant, warrant adult belittling and verbal chastising. This book further offers commentary and examples that disparage Black parenting and Black adulting.

Here, Bryant’s (1907) final refrain summarizes each of the missed communications: “O, Epaminondas, Epaminondas, you ain’t the sense you was born with; you never did have the sense you was born with; you never will have the sense you was born with!” (p. 14). Not only is this Black child scolded for ruining the piece of cake, messing up the butter, drowning the puppy, and dragging the cake on a leash, but the final source of laughter for the reader comes at the story’s end when the Black child steps into hot mince pie because he misunderstands his mother’s instruction: “‘But I’ll just tell you one thing, Epaminondas! You see these here six mince pies I done make? You see how I done set ’em on the doorstep to cool? Well, now, you hear me, Epaminondas, you be careful how you step on those pies!’” (Bryant 1907, p. 15). Predictably, the last scene of this book is the Black child stepping into the presumably still-hot pies: “And then,—and then,—Epaminondas was careful how he stepped on those pies! He stepped—right—in—the—middle—of—every—one” (p. 16). No empathy, compassion, or human dignity is extended to this Black child who suffers insult and injury on multiple fronts. His mistakes and mishaps are meant to draw uproarious laughter and glee from young and old readers alike.11

Offering more trauma-inducing adventures into the animal world, Bernice G. Anderson’s (1930) Topsy Turvy’s Pigtails is the story of the Blackface stocking doll with her characteristic multicolored bows on multiple wheel spoke-like plaits.12 Topsy had earlier appeared in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s (1852) Uncle Tom’s Cabin as the consummate Black girl “pickaninny,” remaining so in an abridged version for young readers, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Young Folks’ Edition (Stowe 1905).

“I’ve made a purchase for your department,—see here,” said St. Clare; and, with the word, he pulled along a little negro girl, about eight or nine years of age.

She was one of the blackest of her race; and her round shining eyes, glittering as glass beads, moved with quick and restless glances over everything in the room. Her mouth, half open with astonishment at the wonders of the new Mas’r’s parlor, displayed a white and brilliant set of teeth. Her woolly hair was braided in sundry little tails, which stuck out in every direction. The expression of her face was an odd mixture of shrewdness and cunning, over which was oddly drawn, like a kind of veil, an expression of the most doleful gravity and solemnity. She was dressed in a single filthy, ragged garment, made of bagging; and stood with her hands demurely folded before her. Altogether, there was something odd and goblin-like about her appearance,—something, as Miss Ophelia afterwards said, “so heathenish,” as to inspire that good lady with utter dismay; and turning to St. Clare, she said,

“Augustine, what in the world have you brought that thing here for?”

“For you to educate … and train in the way she should go. I thought she was rather a funny specimen in the Jim Crow line. Here, Topsy,” he added, giving a whistle, as a man would to call the attention of a dog, “give us a song, now, and show us some of your dancing.”

The black, glassy eyes glittered with a kind of wicked drollery, and the thing struck up, in a clear shrill voice, an odd negro melody, to which she kept time with her hands and feet, spinning round, clapping her hands, knocking her knees together, in a wild, fantastic sort of time, and producing in her throat all those odd guttural sounds which distinguish the native music of her race….(Stowe 1852, pp. 351–52)

Topsy is the antithesis of the white girl Eva, their opposites represented in a doll popular before Stowe wrote her novel: “Topsy-Turvy dolls were popular toys for young children on plantations in the antebellum South. One end … resembled either an angelic white child wearing her best dress or a beautiful white mistress. When turned upside down, the doll revealed the face and costume of a young black female slave or a Mammy figure. These dolls remained popular into the mid-twentieth century, when patterns for the toy were mass produced by companies including McCalls, Vogart, Redline, and Butterick. In the 1940s Redline and Vogart began selling patterns for the dolls under a new name: Topsy and Eva….” (Buckner 2011, pp. 55–56; see also Jarboe 2015 and Vogart 1940). In Stowe’s novel, when Topsy disrupts her new white household, Miss Ophelia questions why Topsy “‘[mis]behave[s] so badly.’” Topsy responds in exaggerated minstrelsy dialect, essentially inviting violence upon her small Black person because she deserves it: “‘Dunno, missis—I ’spects cause I’s so wicked’.... ‘Laws, missis, you must whip me. My old missis always did. I ain’t used to workin’ unless I gets whipped’.… ‘I’s so awful wicked, there can’t nobody do nothin’ with me. I ‘spects I’s the wickedest crittur in the world’” (Stowe 1905, pp. 42–43). That Topsy is rambunctious, misrepresents herself, and insists that she needs to be whipped to keep her in line speaks to the narrative of white supremacy and anti-Blackness that beset this misrepresentation of Black children and therefore justifies violence against them. Judy Garland portrays this humorous, dehumanized Blackface, pigtailed Topsy character in Everybody Sing (Marin 1938). Two white sisters, the Duncan Sisters, even created a comic act (performed 1923–1959) as the characters Eva and Topsy from Stowe’s novel. They refocused “the story of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the relationship between the impish, young, black, female slave Topsy, and her beautiful, young, white, female mistress Eva…” (Buckner 2011, pp. 58–59). The show embodies these racialized stereotypes: Topsy is “impish and wild” and Eva the “sweet” girl needed to “tame this poor child” (59). Eva is “an angel” and “Topsy, a pest.” Topsy is “ragged and black” and “the ‘wickedest gal’” (59).

Capitalizing on the popularity of the Topsy character, Anderson’s (1930) Topsy Turvy’s Pigtails picture book features Topsy as the opposite of her “very prim, trim…, with every pin in place” black-stocking parents: “But Topsy Turvy!—oh, dear me! What a topsy-turvy black-stocking doll she was! She was anything but a prim, trim body, and wherever Topsy Turvy went things seemed to have a way of becoming upside down, inside out and helterskelter all about!!!” (Anderson 1930, n.p.). Already, this child is unattractive because of her physical person—her skin color, her hair, and her body. Not only does havoc follow her, but she is also “so untidy.” The conflict here is that a white child, the presumably white-owned Comical Doll House’s “little mistress,” wants to cut off Topsy’s pigtails, essentially because she can. This white girl child’s skin color and social status give her that authority and privilege, such that Topsy runs away to save herself and her pigtails.

The threat and action of cutting off children’s locks is a reality today, resulting from school policies and individual actions that have attacked Black children. In 2018, the white referee of a New Jersey high school wrestling match “who may have a history of racist behavior” forced Black high school student Andrew Johnson to choose between having his dreadlocks cut or forfeit his match (Hohman 2018). Though his “coaches argued with the referee … about his call,” Johnson chose to comply, and won the match, but “appeared visibly upset” (Hohman 2018). In a 2009 instance, a white teacher, annoyed that a Black seven-year-old was fiddling with her braids in class, punished the student by cutting off one of her braids:

This Black child’s violation and trauma come on many levels—being treated punitively for something about which she was potentially unaware, the premeditated physical assault by the authority figure in a classroom space that should be safe for every child’s learning, the teacher’s making the child the source of class spectacle and peer entertainment, and the fact that the child’s hair was cut and tossed in the trashcan. Neither this child nor the parent may ever know what this teacher’s particular discipline choice aimed to achieve, especially when there was no evidence that the child’s hair ritual was disrupting the class.13Sometimes, when she sits in class, seven-year-old Lamya Cammon twirls the colorful beads that adorn her braids. Her mother … says that she does it “maybe out of nervousness or distraction.” On 28 November, the girl’s first grade teacher at the Congress Elementary School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, became “frustrated” when Cammon kept playing with her hair and told the girl to walk to the front of class. The obedient child complied, and, to her surprise, her teacher reached for a pair of scissors and cut one of Lamya’s braids off. An outburst of laughter filled the room and little Cammon went back to her seat, put her head down on her desk, and cried.(Watts 2009)

The violence against the Black girl child in Anderson’s book once again asserts the trope of a child at the mercy of animals. Specifically, as Topsy runs away from home, she encounters obstacles along the way that threaten to take her pigtails. A goat, for example, blocks her journey: “You shall not pass me until you have given me your beautiful pigtail tied with the scarlet ribbon” (Anderson 1930, n.p.). The goat does not allow her to pass, even though she cries and tries to run away. The goat ultimately takes what it wants, thus violating Topsy’s physical person, further traumatizing her: “‘You must give it to me,’ said the goat, ‘for I need it to tie to my tail so I will look fine at the Animals’ Tail Show tonight.’ AND WITH ONE BIG NIP HE NIPPED THE PIGTAIL OFF! Poor little Topsy Turvy ran on” (n.p.). As Topsy’s journey continues, a cow makes the same threat for her green ribbon, blocking her path and eventually nipping off a second pigtail. A white pig wants, and gets by force, Topsy’s pigtail with the blue ribbon. Another pig nips another pigtail, a donkey wants and nips another pigtail—all leaving Topsy crying and running back home. Through the little white mistress’s negotiations, Topsy is allowed to go back to each of the animals to request her pigtails. Each animal requires that Topsy make their individual animal noises and sounds in order to get her pigtails back. Only with the help of a moon-elf, who gives Topsy a magical whistle that mimics animal sounds, is Topsy able to summon the animals holding her pigtails hostage. While the story allegedly ends happily, with Topsy getting her pigtails back, she cannot pretend away the trauma done to her physical doll person. Topsy cannot save herself and is at the whim and mercy of her white child owner, the animals, and the moon-elf. Readers again witness threats and violence against Black child bodies.

In illustrator Edward Windsor Kemble’s popular Coon series, which includes Comical Coons (Kemble 1898b), Black children and Black adults, presented as one and the same, are, like Topsy—unkempt, unattractive, minstrel Black, clumsy, and prone to accidents and harm as the source of grotesque humor and comedy. Amazon (n.d.a) describes Kemble’s (1898a) A Coon Alphabet as “The classic 1898 African American Alphabet book with wit and humor illustrations in black and white drawing.” Kemble’s Coons: A Collection of Southern Sketches (Kemble 1896) presents similar images of Black characters exaggerated and mocked in the form of a coffee table book. About Kemble’s “Negro drawings,” Railton (2012) writes:

That Black children are physically ugly, lazy, criminal, undesirable, and incompetent beings makes it easier to imagine and accept violations of Black children’s, youths’, and adults’ bodies. These picture books illustrate Black children as grotesque and non-human, clumsy, unkempt, and in need of being rescued and tamed by white saviors—sometimes in a book’s narrative and sometimes in the author’s call to action.I’ve found hundreds of Kemble illustrations of African Americans in periodicals and books from 1885 to 1910. He was used by magazines like The Century to illustrate short stories in the popular, nostalgic genre of the “plantation tale,” and also, for example, did the illustrations for several of Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus books and an 1892 edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. His work was obviously very popular. In a comment on an article he illustrated in The Southern Magazine, The American Monthly Review of Reviews referred to him this way: “the only artist who has yet seemed to have any success in picturing the Southern negro—E.W. Kemble” (April 1894)…. Though mainly an illustrator of other people’s works, Kemble produced two books of his own drawings: Kemble’s Coons (1897) and Comical Coons (1898)…. Over the decades between 1885 and the early 20th century, his “comical” cartoons were also regularly featured in magazines.…[A]ll of them feature caricatures of African Americans.

These racially problematic images transcend US domestic borders and underscore the prevalence of global anti-Blackness in representations of and for children. In the UK, for example, and in addition to Bannerman’s (1899) hugely popular Little Black Sambo, Violet Harford’s (1954) Sunshine Corner Picture and Story Book, features a UK version of the US Blackface pickaninny, the “golliwog,” and includes references to and images from minstrelsy Blackface, such as “the Ten Little N***** Boys” and their “jolly-looking Black Mammy.” Earlier, American Florence Kate Upton’s illustrations in the immensely popular The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a “Golliwogg” (Upton and Upton 1895) inspired the “golliwogg” rag doll. Because she had not patented the figure, more books, dolls, and images followed. Its “fame was so wide that it spread to advertising and other selling items like children’s china and other toys, ladies’ perfume, and jewelry. James Robertson & Sons, British jam factory, used Gollywog as a mascot from 1910 until 2001. ‘Blackjack’—aniseed candy made in United Kingdom used gollywog’s face from 1920s until 1980s” (History of Dolls 2021). Originally published serially by a conservative Belgian magazine in 1930–1931 and then in book form, Hergé’s (1931) Tintin au Congo (translated into English as Tintin in the Congo: US 1991 and 2004 and UK 2005), from his Adventures of Tintin series, was intended to “show Belgium how the Congolese natives were introduced to civilization” (Jühne et al. 2014). The Congolese are represented as childlike, with minstrelsy black facial features, skin color, and hair, and they bow to and call the white teenaged Tintin “mastah.” Ironically, while infamous for its racism, the story is also a source of “national pride” in the Democratic Republic of Congo: “Tintinologist Michael Farr has claimed it is the hardest book to buy in Francophone Africa because it’s always sold out…. Across the country, selling Tintin trinkets to tourists is a lifeline for many families” (M.Admin n.d.). One shop owner said that “‘in the comic strip, you never see … [Tintin] trying to kill the Congolese.’ That, at least, is a much better attitude than that of Tintin’s real-life Belgian contemporaries” (M.Admin n.d.).

Another colonial text for children, A Funny Book about the Ashantees, written and illustrated by Ernest Griset (1874, 1880) was expressly created as “Amusement and Instruction for the Young” (Griset 1880, back cover), its humor and nonsense shared through the judgmental “civilized” white gaze that is totally opposite the perspective of “these [Black] creatures.” The back cover blurb goes on to assert that “These Picture-Books, from Designs by the renowned Artist, Ernest Griset, will be immensely popular with the Young, while the grotesque and extremely amusing Pictures cannot fail to command the admiration of their Seniors” (Griset 1880). Like Hergé’s Congolese figures, Griset’s characters are minstrelsy black, bug-eyed, red-lipped, scantily clad, thin, and seemingly undernourished, and they carry spears and have painted faces. Their dancing is mocked, readers are to see their nose-to-nose greetings with each other as funny, they hunt lions by tricking them, they avoid being eaten alive by a hippopotamus, they talk and eat with their mouths full and with their hands, and they quarrel with one another. A Black child is part of the humor mix, threats of violence, and mockery. In fact, there is little difference between what the single child in this story experiences and what the accompanying adult experiences, underscoring this text again as a representation of the adultification of Black children, whose lives and bodies warrant the same literal and figurative assaults as on adult Black bodies. Black children have no kinship with the protected and safe worlds of white children’s bodies.

3. Conclusions: Blurred Lines

In regard to the many missing and murdered Black children in Atlanta, Georgia, between 1979 and 1981—often called the Atlanta Child Murders—poet and author ntozake shange (1983) beckons Black mothers to move beyond weeping, to screaming and hollering, to making loud noise about their missing Black children in “about atlanta”: “oh mary dont you weep & dont you moan/oh mary don’t you weep & don’t you moan/HOLLAR I say HOLLAR/cuz we black & poor & we just disappear” (p. 45). shange’s call to action emerges from the reality that the boys from mostly Black, poor, and single-mother households, all between the ages of eleven and eighteen, vanished and were found dead, and that there was little national outrage in this country. As though it were a manifestation of the disappearing Black boys in the innumerable folkloric, textual, and filmic renditions of “Ten Little N***** Boys,” this reality emphasizes the low value placed upon Black children’s lives intersectionally.

While this essay focuses on the lack of humanity extended to Black children and Black adults, this argument extends to the historical past and present violence against Latinx and Indigenous Americans, Asians, and Asian Americans—which includes the massacres of Chinese workers during the Gold Rush era, the WWII concentration camps for Japanese American families, and the current random horrific violence against Asian American elderly people and women—and, of course, the violence against Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Middle Eastern Americans, too. Recently, the US immigration policy that led to keeping migrant children in “cages” and separated from their parents at the US–Mexican border has been traumatic for those children and families. Angela Barraza, a trauma-informed care specialist at the El Paso Child Guidance Center, explains:

The traumatic separation of migrant children from their parents echoes the separation of enslaved African American families on US antebellum auction blocks or at the reading of a slaveowner’s will. In Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent, Isabel Wilkinson (2020) offers further historical context:Migrant children and their families experience a great number of stressors throughout their pre-migration, flight, and resettlement experiences that impact their psychological well-being …. [A] multitude of social, emotional, and cognitive complications … can occur from migrant children being separated from their parents. Migrant children may have symptoms including anxiety, recurring nightmares, insomnia, secondary enuresis, introversion, relationship problems, behavioral problems, academic difficulties, anorexia, somatic problems, as well as anxiety and depressive symptoms …. [They can feel] [s]ad, empty, hopeless, [experience] loss of interest, worry, fear, fatigue, irritability, restlessness….(Coulehan 2020)14

The United States has a centuries-old history of people in the upper caste [whites] controlling and overriding the rightful role of lower-caste parents and their children, the most extreme of which was selling off children from their parents, even infants who had yet to be weaned from their mothers, as with fillies or pups rather than human beings. “One of them,” remarked an enslaver, “was worth two hundred dollars … the moment it drew breath.” This routine facet of slavery prevailed in our country for a quarter millennium, children and parents denied the most elemental of human bonds.(p. 211)

And Native American children endured the trauma of boarding schools, where their language and culture were erased all in the name of cultural assimilation and hegemonic control. Violence clearly manifests itself in this opening piece of Navajo poet and author Laura Tohe’s (1999) No Parole Today. “Our Tongues Slapped into Silence” intermingles the popular Dick and Jane early readers of the 1930s–60s “that introduced us to the white man’s world” with Tohe’s memories of the abusive boarding school environment:

In first grade I was five years old, the youngest and smallest in my class, always the one in front at group picture time. The principal put me in first grade because I spoke both Diné and English….

All my classmates were Diné and most of them spoke only the language of our ancestors. During this time, the government’s policy meant to assimilate us into the white way of life. We had no choice in the matter; we had to comply. The taking of our language was a priority.

Dick and Jane Subdue the Diné

………

See Eugene speak Diné.

See Juanita answer him.

oh, oh, oh

See teacher frown.

uh oh, uh oh

In first grade our first introduction to Indian School was Miss Rolands, a black woman from Texas, who treated us the way her people had been treated by white people. Later I learned how difficult it was for black teachers to find jobs in their communities, so they took jobs with the Bureau of Indian Affairs in New Mexico and Arizona in the 1950s and 60s….

This cultural genocide—cultural violence as identity erasure—has persisted for centuries, never distinguishing between Native American children and Native American adults.Miss Rolands, an alien in our world, stood us in the corner of the classroom or outside in the hallway to feel shame for the crime of speaking Diné. Other times our hands were imprinted with red slaps from the ruler. In later classes we headed straight for the rear of classrooms, never asked questions, and never raised our hand. Utter one word of Diné and the government made sure our tongues were drowned in the murky waters of assimilation.(pp. 2–3)

As with Black children, violence has beset all adults and children of color. Across non-white communities, violence against children is not distinguished from the physical and cultural violence against adults. In the context of the killings of unarmed Black adults that have given rise to the Black Lives Matter movement, therapists contend that what children witness of adult trauma immediately or vicariously potentially constitutes their trauma as well: “[B]lack children are experiencing trauma as a result of the chaos they’re witnessing of people who look like them being killed by law enforcement…. ‘They (black children) may not be directly connected to George Floyd or Ahmaud Arbery, but seeing someone being gunned down or hearing about it … the children know’” (Jackson 2020). While all children are being affected by this current state of social unrest connected with violence, “[c]hildren of color deal with racial trauma and stressors that other children [white children] do not experience because of racism…” (Jackson 2020). That a twelve-year-old Latinx girl is body-slammed by a school district police officer (Quinlan 2016) is yet more evidence that violence against Black and Brown children and youth far exceeds that of authorial violence against white children and youth.

The everyday and seemingly mundane reality of Black children’s and Black adults’ bodies subjected to perpetual white violence is beyond alarming. This intergenerational trauma, whether through US history, police brutality, curriculum violence (and silences) in the classroom (see Jones 2020), or children’s books, continues to be perpetuated and absorbed unless the roots of white supremacy are extracted, examined, understood, and acknowledged—and a fundamental humanity extended to all people, young and old. When children’s books and games that purposefully mock Black children’s identities, deny their fundamental humanity, and even normalize their deaths are created, consumed, and nostalgically held dear for well over a century, it not so surprising, then, that, in 2019, Florida police would arrest, handcuff, fingerprint, and take a mugshot of a six-year-old Black girl after a classroom tantrum (Darby 2019), or that two years later a white teacher would humiliate a five-year-old Black kindergartener by forcing him to clean a clogged toilet with his bare hands (Torres 2021).

The dehumanization of Black children and families is likewise deeply entrenched in and through higher education. In an online Ivy League class, “Real Bones: Adventures in Forensic Anthropology,” the instructor, “without the permission of the deceased’s living parents,” uses the pelvis and femur of a teenaged girl gathered from the ashes of the 1985 bombing of the residential headquarters of the Black liberation and environmental activism group MOVE, discussing and holding the girl’s bones up to the camera (Pilkington 2021a).15 After suspension of the 5000-student course, Princeton University’s anthropology department issued a statement admitting to the fundamental dehumanization that has in part defined the field of physical anthropology:

“As anthropologists we acknowledge that American physical anthropology began as a racist science marked by support for, and participation in, eugenics. It defended slavery, played a role in supporting restrictive immigration laws, and was used to justify segregation, oppression and violence in the USA and beyond…. [P]hysical anthropology has used, abused and disrespected bodies, bones and lives of indigenous and racialized communities under the guise of research and scholarship. We have a long way to go toward ensuring anthropology bends towards justice.”(Pilkington 2021b)16

Integral to all aspects of American sociocultural education—particularly after the 2020 murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Brionna Taylor, and countless others, and the subsequent alleged global racial reckoning—is acknowledging and understanding that the profoundly inhumane objectification of and violence against Black children’s and Black adults’ bodies are not only historically and inextricably linked but continue in the present.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The following are those that I have in my personal children’s books collection, all with the characteristic Blackface minstrelsy imagery, some more grotesquely illustrated than others: The Story of Little Black Sambo (Bannerman 1931), illustrated by Lupprian, from the McLoughlin Brothers’ Junior Color Classics series; Platt & Munk’s connect-the-dots The Little Black Sambo Magic Drawing Book ([1928] 1946); Little Black Sambo: The Listen Look Picture Book (Bannerman 1941) (“READ the Story!/A 16-page picture book in full color/HEAR the Story!/A double-faced record with dramatic sound effects”); the Little Black Sambo Animated! Animated! (Bannerman 1943), a pop-up book illustrated by Wehr; recordings by RCA’s Little Black Sambo’s Jungle Band (Bannerman 1939) and Columbia Records’ Little Black Sambo (Bannerman 1946); a Little Black Sambo (1931) board game included in Kellogg’s Story Book of Games (Book Number One) appearing with Cinderella, The Three Little Pigs, and Hansel and Gretel, suggesting the level of Little Black Sambo’s popularity among European Americans; and a vintage Little Black Sambo ([1924] 1945) board game. Among the anthologies in which Little Black Sambo appears are Nursery Tales Children Love, edited by Piper (Bannerman 1925) and My Favorite Story Book III, edited by Hays (Bannerman 1942). |

| 2 | “Frederick A. Stokes of New York published the first US edition of Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo in 1900. After the story was reproduced in many pirated versions, Stokes moved to affix the line ‘The Only Authorized American Edition’ to its 1923 edition to maintain some kind of distinction in the marketplace” (Biblio 2021). |

| 3 | In addition to appearing in Bannerman’s initial 1899 story, Little Sambo appears in her later books and in many other authors’ stories (dozens of them pirated and with innumerable spinoffs to today). These include, for example, Ver Beck (1928a), Little Black Sambo and the Baby Elephant; Ver Beck (1928b), Little Black Sambo and the Monkey People; Bannerman (1935), The Little Black Sambo Story Book (which includes five additional stories: “Little Black Sambo and the Baby Elephant,” “Little Black Sambo and the Tiger Kitten,” “Little Black Sambo and the Tiger Kitten,” “Little Black Sambo and the Monkey People,” “Little Black Sambo in the Bears Den,” and “Little Black Sambo and the Crocodiles”); and Bannerman (1936), Sambo and the Twins: A New Adventure of Little Black Sambo. Although some scholars contend that babies were used as “alligator bait,” the consensus among many others is that this cannot be definitively proved or disproved. What is clear, however, is that this grotesque image exists to underscore a real anti-Black sentiment that included both Black adults and Black children interchangeably: “During slavery and the Jim Crow era in the United States, African Americans were brutalized and mistreated in almost every way imaginable. If there was a way to kill, maim, oppress, or use an African American for any reason, it more than likely happened. If the skin from an African American might be used for leather shoes or handbags, (see Human Leather), then pretty much all atrocities were possible and probable. African American babies being used as alligator bait really happened, and it happened to real people. It doesn’t seem to have been a widespread practice, but it did happen” (Hughes 2013). See also Emery (2017). |

| 4 | See also Bannerman (1904), Pat and the Spider, which she illustrated, presumably based on her own son Pat. The boy in the book definitely has the body, facial features, hair, and clothes of an actual boy. |

| 5 | See Joseph Lelyveld’s (1966) New York Times book review “Now Little White Squibba joins Sambo in facing jungle perils: NEW BOOK’S STAR IS WHITE SQUIBBA”: “None of [Bannerman’s Black] characters has fallen victim to liberal sensitivities on racial issues here [UK], as they have in the United States…. ‘I’ve never heard of anyone complaining about those stories,’ a librarian said. ‘They’re well-written, gripping stories. Children love them.’ A Chatto & Windus editor said: ‘These stories belong to an entirely different age. They’re classically innocent. Certainly there’s nothing malicious about them.’ Chatto & Windus also publishes ‘Ten Little N******,’ which first appeared in 1908” (p. 34). |

| 6 | Based on the earlier nursery rhyme, Septimus Winner (1868) wrote “Ten Little Indians” for a minstrel show, which apparently inspired Frank Green’s (1869) adaptation “Ten Little N******,” using nearly identical lyrics and which was sung by the original Christy Minstrels in addition to becoming a minstrel show standard (Opie and Opie [1951] 1997, pp. 387–88; see also “Ten Little Niggers. The Celebrated Serio Comic Song” 2016). |

| 7 | See also McLoughlin (2012), Simple Addition by a Little N*****, the abbreviated version of their original c. 1874 edition. |

| 8 | Davis (2005) claims that the Faultless storytelling–advertising booklets, printed by the Charles E. Brown Printing Company and citing no author, were written by D. Arthur Brown, a pastor (17-18). Brown “did not forget the ethnic groups” (p. 24). In addition to the Ten Little Pickaninnies, told “[i]n the tradition of one little, two little, three little Indians” (p. 24), Davis further attests to what she sees as Brown’s interest in diversity: “Hans and Gretel are Dutch [volume 32], and Arthur remembers The Indians [volume 33]. The Chinese are not forgotten [Chin-Chin and Chow, volume 8]. He spins a tale of love with its painful moments of competition, even suicide. Of course, there is a happy ending because of Faultless Starch. ‘Chin-chin married Chow, and they did live a long and happy life, upon the shelf behind the vase—Chin-chin and Chow, his wife’” (p. 24). |

| 9 | Also see DixonFuller2011 (2012), for an updated iteration of the test, and u/BulkyBirdy (2019), showing the same test given to Italian children with the same resulting preference for white dolls. |

| 10 | See Southey (2020) regarding the petition “for the ‘immediate removal’ of all products marketed under … Conguitos branding” because of its racist cultural history and racist representation of Black children’s bodies. |

| 11 | In contrast, this same humor through language literal and figurative is the basis of the beloved Amelia Bedelia series, originally by Peggy Parish (1963–1988) and continued by her nephew Herman Parish after her death about a white woman who misunderstands language cues and expressions and is the source not of mockery but of light amusement and glee. She is not humiliated or mocked as is Epaminondas. |

| 12 | Two other books in Anderson’s Topsy Turvy black-stocking character series are Topsy Turvy and the Tin Clown (Anderson 1932) and Topsy Turvy and the Easter Bunny (Anderson 1930, 1939), the latter originally published in Topsy Turvy’s Pigtails as “Topsy Turvy and the Easter Bunny’s Eggs” with three other tales: “Topsy Turvy’s Valentine Box,” “Topsy Turvy and the Christmas Tree,” and “Topsy Turvy and the Christmas Tree.” |

| 13 | This is certainly not the only instance of hair-related traumatization of Black children. See, for example, Gray (2021). Native American children have historically been assaulted: boarding school standards stripped Indigenous children of their own language, traditional clothing, and hair customs. Recently, a teacher cut a child’s hair as part of Halloween role playing: “Students say their English teacher, Mary Eastin, was dressed up as a Voodoo Queen of New Orleans, a 19th century figure who practiced occult and conjuring acts…. [T]he teacher confronted a Native American student who was wearing her hair in braids.… Eastin asked the student if she liked her braids. When the student said she did, the teacher picked up a pair of scissors and cut off about three inches of the student’s hair…. The president of the Navajo Nation, Russell Begaye, also responded to the incident in a statement, calling it a ‘cultural assault’” (Schuknecht 2018). |

| 14 | As the following recent attack on children shows, anti-Mexican and Islamic child hate also directly reflects sentiments against adult Mexicans and Muslims: “A Des Moines woman has pleaded guilty to federal hate crimes for intentionally driving her SUV into two children in 2019 because she said she thought one was Mexican and the other was a member of the Islamic State group…. Prosecutors said Franklin intentionally jumped a curb in Des Moines that afternoon and struck a Black 12-year-old boy, injuring one of his legs. During her hearing Wednesday, Poole said she thought the boy was of Middle Eastern descent and was a member of IS…. Minutes later, Franklin ran down a 14-year-old Latina girl on a sidewalk, leaving her with injuries for which she was hospitalized for two days. Police said Franklin told them she hit the girl because ‘she is Mexican.’ About an hour later, Franklin was arrested at a local gas station, where officers say she had thrown items at a clerk while yelling racial slurs at him and other customers” (Associated Press 2021). |

| 15 | In 1985, when police attempted to serve several warrants at MOVE’s residential headquarters, a gun battle with police ensued. Philadelphia police subsequently dropped aerial incendiary bombs on the building (reminiscent of the police-sanctioned aerial bombings by a dozen or more planes that destroyed the Black community of Tulsa in 1921, killing up to 300), ultimately razing sixty-one homes and killing five children and six adults (Pilkington 2021a). In 2020, the city of Philadelphia formally apologized for the bombing, which led to planning for an inaugural commemoration of the event in 2021. |