Recently, John D. Niles has advanced a codicological reading of the

Exeter Book (

1936), the most extensive and varied extant collection of Old English verse (

Niles 2019). Whereas traditionally its poems have been taken piecemeal, or by genre (for example, the 95-odd riddles), Niles argues for a broad unity to the compilation, governed by a “monastic poetics” capable of bending even deeply traditional poetic tropes towards orthodoxy for a powerful didactic and contemplative effect. Such a collection, Niles explains, reflects the context of the tenth-century Benedictine reform, and he locates it specifically with St. Dunstan and Glastonbury, circa 970 (pp. 40–61).

1 The present essay will consider another compilation of Old English verse that has also been attributed to Dunstan, the so-called

Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn.

2 Not only are the dialogues rich fodder for a codicological approach, they also, unusually for vernacular verse, afford an opportunity for intercodicological comparison (as they exist in more than one manuscript). The varied contexts for

Solomon and Saturn span the period from before the Benedictine Reform to the aftermath of the Norman Conquest, and thus, rather than appearing as a snapshot in time, synchronically, as the Exeter Anthology (See also

Muir 2000) (as Niles terms it) does, the dialogues of

Solomon and Saturn invite a historical perspective. Specifically, they allow us to think about the uses for esoteric learning in the “wisdom tradition”, and perhaps the role of poetry in the same, over time.

Codicological readings are indeed an area of promise in recent research, from Andy

Orchard’s (

1995) study of the

Beowulf manuscript to Arthur

Bahr’s (

2013)

Fragments and Assemblages (the latter a study of compilations from the later Middle Ages). Again and again, scholars returning to the context of a manuscript discover not the chaos or ineptitude that they were taught governed—sadly—many a medieval collection, but instead a rich, profoundly local, often idiosyncratic logic. Discerning such logic demands the work not of the traditional disciplines alone, such as source studies, exegesis, or codicology, but a multivalent approach to both reading and history.

3 Bahr, for example, adopts Walter Benjamin as his methodological lodestar for an expanded reading praxis of later medieval compilations, considering the compilation from the past, those responsible for its making, and those eyes under which it has passed on its way to the present as constituting an ever-shifting “constellation” (pp. 12–15). Early-medieval manuscripts have generally been approached from a more historicist (and less theoretical) perspective, but that may be slowly changing. Orchard’s approach to the

Beowulf manuscript is ultimately literary-critical, whereas more recently,

Mittman and Kim (

2013) have considered that manuscript’s version of

The Wonders of the East from a much more theoretical perspective (one which nonetheless rather isolates the text from its manuscript fellows). Niles’ treatment of the Exeter Book is exegetical at core, whereas that of Brian O’Camb combines cultural studies, manuscript studies, literary criticism, and historiography. My comparative approach to CCCC 41, CCCC 422, and BL Cotton Vitellius A.xv, the manuscript witnesses to

Solomon and Saturn, will emphasize semiotics in reading both text and compilation (echoing Bahr’s approach to constellated form).

The claims for Dunstan’s compiler-authorship of both the Exeter Book and the Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn could present a testable hypothesis. Do the monastic poetics of the Exeter Book also characterize, for example, the poetics of the fullest collection of Solomon and Saturn texts, in CCCC 422? Do they appear similar enough to justify shared authorship or compilership? I am not certain I wish to approach the question with such positivism. A single author can, after all, have distinctive phases, for one thing, and different authors can form a school characterized by a single style. I am more interested in ways to read and understand compilations themselves. Niles’ treatment of the Exeter Book as a coherent “work”, one that harnesses pre-Christian form and themes for Benedictine contemplative purposes suggests a coherent “strong reading” of that codex—the first such attempt. My own “strong reading” suggests that the Solomon and Saturn dialogues display in their earliest compilations a poetics distinct in some respects from the orthodox emphasis on transcendence that characterizes Niles’ reading of the Exeter collection. The Solomon and Saturn dialogues evince a poetics more bound up with liturgical language and its sacrality, and with esoteric learning in the Irish tradition. Since there are three manuscript witnesses to Solomon and Saturn in some form, I try to read the differences among them in a context of historical difference, though ultimately my remarks on literary history will remain speculative and limited to the manuscripts I have considered.

Only in the last few decades has much interest been shown in the

Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn.

4 Their exuberant Irish “symptoms”, lack of commitment to either orthodoxy or verisimilitude, and failure to be either heroic or lyric poetry (or even to pick either verse or prose) long relegated them to the outer darkness, where exegetical and historicist criticism disdain to tread.

5 At the same time, the earliest of the dialogues, in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 422 (Part I, mid-tenth century (

Anlezark 2009, pp. 1–4;

Budny 1997, p. 645;

Ker 1957, p. 119)), is also noteworthy as the earliest extant text in the fascinating and expansive European Solomonic dialogue tradition. Against the gleeful obscenity of this tradition’s later reflexes, the Old English dialogues, however unruly, read like edicts of the Pope—or the

sententiae of his very pious grandmother.

6 This is to say that the Old English dialogues are relatively tame, their nonconformity (to modern expectations) and heterogeneity coming in the form of formal experimentation and wide-ranging allusiveness rather than in the form of inversion. Nevertheless they should be seen in the diachronic context of probing and questing that gave rise in some times and places to riddles, in others to poetic contests, in others still to satirical challenges to state and ecclesiastic power.

In all the Old English

Solomon and Saturn dialogues, the biblical King Solomon, renowned for his wisdom, engages in questions and answers with a learned foil from the pagan world whose name,

Saturnus, alliterates with his own. Many have read this “Other” as not only Solomon’s adversary but also a kind of villain, erring in his approach to wisdom (wanting to gobble books, for example) and thus demonstrating for a monastic reader how not to engage in learning.

7 On the other hand, others, including myself, have argued that

Solomon and Saturn’s ostensible contest (they “flytan”, or contend, according to

Solomon and Saturn II, and Saturn joyfully admits defeat in a short fragment in the same manuscript) is more cooperative and complementary than adversarial.

8 This is indeed an ethos inherited, as I argue, from the Irish poetic contests investigated by Charles D.

Wright (

2013) and John

Carey (

1996). Nancy Mason Bradbury has argued for a similar complementarity in the subversive and class-conscious late-medieval/Renaissance

Solomon and Marcolf as well. In the latter, much later Latin dialogue, Solomon offers authoritative gnomic statements, and Marcolf inverts each one, answering high sententia with, as Jan Ziolkowski puts it, the language of the barnyard (

Ziolkowski 2008, p. 3). The grotesque peasant Marcolf displays a wily street sense, which Solomon’s authority overcomes only by the assertion of power. Thus, according to Bradbury, it is clear to a reader that the two contestants each possess legitimate knowledge of a sort. The “low” is able to reveal vulnerabilities in the “high”, even if ultimately the status quo is restored. And Marcolf articulates the earthy truths of our shared physical existence that transcendentalizing traditions since Plato have sought to avoid.

9 In his insistence on the sublunary real and on speaking its truths to power, Marcolf stands with one leg in the late-medieval fabliaux and one on the Elizabethan stage. In some ways, then, the vulgar peasant Marcolf is an avatar for the earlier Saturnus, particularly in Bradbury’s approach to complementary “rival wisdoms”.

In Solomon and Saturn, the two contestants’ complementarity is pronounced, and they are much less starkly opposed. Both are sages, learned in books, though Solomon may possess a key that Saturn knows he lacks. For example, Saturn seeks the liturgical knowledge enshrined in the Pater Noster and probes the philosophical insights of Christian learning. As I mentioned above, Saturn is unfazed in being bested by Solomon—he was after enlightenment, not supremacy—and by the twelfth century and the Prose Solomon and Saturn (in Cotton Vitellius A.xv) if one may take a long view, any pretense of drama between the two interlocutors gives way to the encoding of catechetical-encyclopedic knowledge for its own sake. Solomon and Saturn’s questions and answers have baffled (and delighted) readers for decades, as they range from displays of highly literate grammatica to explorations of metaphysical paradox that often seem to dip into reservoirs of mythic or folkloric tradition. These dialogues are fascinating in their own right; they represent a truly long and significant tradition in early-medieval European literature; and their manuscript witnesses include the Beowulf manuscript itself (BL MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv). Appended early to the liturgy (speaking of canonicity), and appearing thus in two extant manuscripts, as I will discuss below, the dialogues end up, on the other side of the Norman Conquest, in a pre-scholastic compendium of Christian philosophy (the Southwick Codex of Cotton Vitellius A.xv), which in turn is appended, in the Renaissance, to the Beowulf compilation’s monstrous wonders. Having begun their literary history as poetic explorations of a mystery, as I will argue, by the time of the Reformation, they are drained of their Logomystik and have become curiosities in the cabinet of the Cotton library.

CCCC 422, also known as the Red Book of Darley, is, as I mentioned above, the codex with not only the oldest but the fullest collection of

Solomon and Saturn material, comprising the four texts edited by Daniel Anlezark as

The Old English Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn. This manuscript comprises two parts, which were bound together at least by the twelfth century, which is also when the Southwick Codex of the

Beowulf manuscript, containing the latest

Solomon and Saturn dialogue, was copied.

10 The bulkiest by far is Part II, a very idiosyncratic eleventh-century breviary, as Mildred Budny and Christopher Hohler have observed, containing mass texts, sometimes with music, but also prognostics, formulae for ordeals, and calendrical/computistical materials.

11 Budny notes that it was apparently made in an episcopal center, but was most likely meant for, and certainly ended up in, a more provincial locale (p. 646). The book is very small and portable, particularly when compared to the much larger and grander CCCC 41 (which contains only a fragmentary

Solomon and Saturn I (ll. 1–93), in its margins on pp. 196–98):

| CCCC 422 | CCCC 41 |

| 194 × 129 mm (Budny 645) | 352 × 216 mm (Budny 501) |

| 7.6 × 5.1 in. | 13.9 × 8.5 in. |

![Humanities 11 00052 i001]()

The book would thus have been useful to a parish priest in performing his duties, which seem to have spanned both the strictly orthodox and what used to be called “popular” practice.

Part I of the manuscript, the mid-tenth-century

Solomon and Saturn material, has been dismissed as “flyleaves”—26 pages of flyleaves, which Budny notes with a skepticism I share (pp. 647–48). The two quires appear to have been excised from a prior compilation (given their acephalous and atelous nature) and bound, between 1060 and 1200, with Part II.

12 The contents of Part I are:

Solomon and Saturn I without its beginning and the

Solomon and Saturn Pater Noster Prose without its end (due to a missing leaf), both of which center upon the power of that prayer; then the poetic fragment that may or may not be the proper ending to

Solomon and Saturn II followed by

Solomon and Saturn II, with two missing leaves and one page that has been erased and overwritten with an excommunication formula in Latin.

13A modest amount has been written over the past three decades attempting to address the meaning of these texts and individual cruces as separate entities, while recently, Heide Estes has argued that they form one prosimetric whole.

14 I have recently argued, and reiterate in a forthcoming book, that the

Solomon and Saturn dialogues are unified by a concern with the enigma of the Logos, participating in an early “Incarnational poetics”, a term I take from Cristina Maria

Cervone (

2012). This is important because an Incarnational poetics relates the two parts of the manuscript to one another, the

Solomon and Saturn texts to the liturgy. However, the Logocentrism of the CCCC material, to borrow and reframe a term from Jacques Derrida, is, by design, obscure (we are in a tradition of deliberate, learned-devotional obscurantism not unlike that which Niles detects in the Exeter Book riddles). The first two texts treat the wonderful qualities of the Pater Noster, which is not merely an example of magical or incantatory speech, but the actual words of the Word, with a special relationship to the Incarnation. Solomon instructs, for example, that “the palm-twigged Pater Noster unlocks heaven, delights the holy, mollifies the lord, fells murder, quenches the devil’s fire, kindles the lord’s” (“Ðæt gepalmtwigede, Pater Noster / heofonas ontyneð, halige geblissað, / Metod gemiltsað, morðor gefylleð / adwæsceð deofles fyr, dryhtnes onæleð”) (

Solomon and Saturn I, ll. 39–42,

Anlezark 2009, p. 66).

15 Such power could, perhaps, be an attribute of an “ordinary” incantation, if that is not an oxymoron. Yet the Pater Noster is “palmtwigged”, a lexical clue that associates it specifically with the person of Christ.

16 More importantly, the Pater Noster is the prayer that Christ offers in the course of the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew, as an example of how to pray (Matt 6: 9–13). Later codified as liturgy, its words are the uttered words of Christ, who is the Word that was made flesh in the Incarnation, according to the Gospel of John (John 1: 1–14). Given Christ’s status as Word, there is a special relationship between words Christ spoke—red-letter words in later print practice—and the mystery of the Incarnation, a relationship important to both early and late-medieval Incarnational poetics. In

Solomon and Saturn I, for example, the very letters of the Pater Noster come alive and do battle against the devil and thus participate in the power of Christ himself, a sacramental status made clear in the

Pater Noster Prose, where the Pater Noster stands in for the Son.

17 The last stage of a shapeshifting contest in which the prayer is pitted against the devil, for example, ends with the devil in the form of death, matched, or rather trumped, by the Pater Noster in the form of the lord (“on Dryhtnes onlicnesse”), whose salvific feat, after all, was to rise from the dead (

Anlezark 2009, p. 72). The Pater Noster, further, has unmistakably divine properties, with a golden head and silver hair, and a heart twelve thousand times brighter than the heavens (

Anlezark 2009, p. 74). The Pater Noster dialogues in CCCC 422 convey that the Pater Noster is a sacramental form of words, with a particular, participatory relationship to the Word.

Solomon and Saturn II has similarly Incarnational underpinnings, treating all manner of ontological questions only to arrive at the nature of the Eucharist:

Swilc bið seo an snaed aeghwylcum men

selre micle, gif heo gesegnod bið,

to ðycgganne, gif he hit geðencan cann,

[Thus is that one morsel, if it be blessed, much better for any man to ingest, if he can conceive it, than a seven days’ feast.]

Again, it is not overtly obvious that the poem has turned to the Eucharist with this passage, but rather implicit in context as well as in form. As I have elucidated elsewhere, the passage is part of a broader, tripartite exploration of substances that are at once physical/quotidian and spiritual in nature. First water (interrupted by a missing leaf), then bread, and finally light are given parallel phrasing that sustains the duality and ambiguity of these substances and does not resolve them into one valence or the other. Water is both the water that runs upon the earth and the water of baptism. Bread is just crumbs dropped on the floor, but it also, mysteriously, nourishes the soul. Light has “Christes gecyndo” (Christ’s nature) and both the form and the efficacy of the holy spirit, but it can also burn up your barn in the form of fire. The irreducible duality of these substances is related, as the poem makes explicit (“Christes gecyndo”), to the dual nature of Christ. Christ is both God and human, ineffable and effable, a profound paradox Augustine explored most fully in

De Trinitate (

Augustine 1991). As Vivien

Law (

1995) and Michael

Herren (

2011), in particular, have explained, early Insular esoteric writers such as Virgilius Maro Grammaticus and “Jerome” the cosmographer (technically, he is recorder of one Aethicus Ister, just as Adomnán recorded the otherwise unknown Arculf) seem to have made paradox their discursive foundation, drawing on both Irish poetic tradition and Christian exegesis.

18 Texts in this branch of the Insular “wisdom tradition” are often playful, reflecting their exclusive audience, but their playfulness has tended to obscure from modern readers their profound philosophical premises. As Law avers, behind the elaborate and polyglot verbal surfaces lay always the Word (pp. 25, 57). The relationship between that ultimate, divine Logos and uttered words manifest in the world was the object of endless fascination. Bringing together not only the Irish and patristic traditions but also the manifest ambiguities of English poetry, texts such as the Old English

Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn may be seen alongside the Old English and Anglo-Latin riddles in exploring paradox in a forum of dialogic challenge. Whether in the voice of an object demanding to be named or in the voices of two figures debating the nature of fate and free will, these texts ask the hardest questions of their time in a form that, as I have said elsewhere, resists resolution, allowing two to remain two, even though Saturn, for example, is evidently happy in his defeat.

19In this light, against this background, in which the

Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn are playful but serious products of a tradition whose fundamental object of inquiry is the Logos, it becomes possible to consider how the dialogues were seen as fitting to conjoin to a portable breviary. Part II of CCCC 422 contained all manner of materials useful to a parish priest, including the liturgical language central to the performance of the mass. The Benedictine reform seems to have produced not only renewed monastic rigor and the commitment to orthodoxy that would find such vigorous expression in the person of Ælfric of Eynsham. It also gave rise, according to Niles and O’Camb, to a vernacular monastic poetics that we see evident in the compilation of the Exeter Book. The

Solomon and Saturn dialogues represent a slightly earlier iteration of such a poetics—perhaps best seen as a prototype or progenitor—drawing on earlier traditions of Insular learning (Anlezark, again, dates them around 930). They are mixed in terms of genre, and it would behoove us to recall that a dialogue in mixed verse and prose is of course rather the standard form for an important philosophical text in the early Middle Ages. This is the form of

Boethius’ (

1962)

Consolatio philosophiae and it is also the form of Martianus

Capella’s (

1983)

De nuptiis. In CCCC 422, Part I, we might see a prosimetric exploration of the Pater Noster and the sacramental Word behind it, a fitting preface to the breviary that follows as a way of exploring the nature of its liturgical language. The joining of the two parts of the manuscript took place likely in the wake of the Conquest, again, between about 1060 and 1200. The dialogues, as I have suggested, represent a venerable Insular tradition of learning, and they were perhaps valued as such, in a way similar to the reverence Elaine Treharne has traced in the copying of older hands in the Southwick Codex of Cotton Vitellius A.xv. The book certainly carried cultural cachet, as someone in the sixteenth century noted along with its special name the fact that it was long “held in reverence” in its Derbyshire community, with the power to cause madness in the swearer of a false oath.

20 I do not think that Part I of CCCC 422 constituted flyleaves, but rather a way for an English priest to think philosophically about the nature of the liturgy he performed and its relation to the Word it embodied. Even if he did not himself possess learning enough to plumb the depths of the texts themselves, they may, again, have stood for something for him, a tradition of learning that was fading.

This spatial relationship to a heftier bind-fellow is shared by my second manuscript (I am not moving chronologically), the “Southwick Codex” of the

Beowulf manuscript, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, adjoined to the more illustrious “Nowell Codex” after the medieval period. This step-sibling to

Beowulf’s book of monsters, as Andy Orchard has put it, is rarely discussed, though Elaine

Treharne’s (

2016) recent essay will no doubt prompt renewed attention. Southwick’s

Solomon and Saturn dialogue is later than the others and was edited, by virtue of extensive shared material, with the Old English

Adrian and Ritheus by J. E. Cross and Thomas D. Hill. It is tucked into the middle of the Southwick compilation, in a structure you see repeatedly in early English manuscripts as well as early English texts: more conventional material on the outside, and what I have called, somewhat irreverently, “party in the middle”—more eclectic or less orthodox material in the center. In Southwick, we see the Old English translation of Augustine’s

Soliloquies, followed by the

Gospel of Nicodemus, then the prose

Solomon and Saturn, and finally the first nine lines of a homily on St. Quentin. One way of looking at this ordering is to recognize that the more Roman- or continental-aligned material, Augustine and St. Quentin, is at the edges, and the more Irish-related, apocryphal material is tucked into the center—”party in the middle”. The peripheries may be seen in this light as “protective”, forming a cover for the more heterodox matter within. As I say, this is a structure attested elsewhere in the corpus; it characterizes the accreted language of the

Æcerbot charm (the text itself, not its placement in the codex) in BL Cotton Caligula A.vii, for example, and also the final manuscript I will discuss, CCCC 41.

21However, this is not the only way to imagine the Southwick compilation, and maybe not the best one, either. For this appendage to the Beowulf compilation’s liber monstrorum may perhaps be considered generically, as a liber dialogorum, in which Solomon and Saturn joins other dialogues in probing the outer limits of a philosophy rooted in doctrine. For all three long texts in the compilation, the Soliloquies, the Gospel of Nicodemus, and the Solomon and Saturn, feature that ancient form of learned display, the dialogue. I will give a short description of each and then consider why a twelfth-century compiler might have brought them together. Augustine’s text, as adapted by the Old English translator, is a discourse between the soul and reason, in which the soul cannot quite come to a satisfactory understanding regarding its own immortality and in particular, the continuity of consciousness from one life to whatever is next. It considers fundamental questions about the human mind and human existence within a Christian ontology. The Gospel of Nicodemus embeds multiple dialogues, first between Pilate and various “players” in the Passion story, and then between Satan and Hell as they anticipate the arrival of the harrowing Christ. That is, the only part of the Passion excluded from this account is the crucifixion. Nicodemus’ multiple dialogues, then, consider the circumstances that led to the Lord’s death and that followed from it. Given that dialogue is an ancient way of interrogating the facts of the world, it seems fitting for a learned Christian dialogue to consider the pivotal event in salvation history in this way, exploring conditions before and after, ramifying outward from the crux, the central event fixed by doctrine.

In a similar spirit, then, we can see the

Prose Solomon and Saturn considering the fundamentals of scripture, the ontologies behind all sorts of biblical facts—they have been called “trivia”, but for a believing Christian they are far from trivial. For while this late, highly schematic

Solomon and Saturn dialogue has none of the drama of the poetic texts in CCCC 41 and 422, it evinces an Isidorean, Irish-inflected encyclopedism that grounds all of life in the authority of scripture. Like Aldhelm’s riddles,

Solomon and Saturn’s dialogue broadly concerns the theme of creation and its relation to scriptural authority, and its arc overall is from the creative act of the Logos to the bread of life that sustains us in the world. The first five questions concern God’s creation of the world. Where did God sit when he made the heavens and the earth? What was the first word that came from God’s mouth? What is God? Why is heaven called heaven? The question about God’s first word is particularly fascinating, as the answer is not simply “fiat lux”, but rather, “fiat lux, et facta est lux” (

Cross and Hill 1982, p. 25). His words at Creation, but also his words in the form of the scriptural account of Creation. God spoke the Scriptures themselves, hinting at the recursive action of Christ as manifestation of the Godhead in the world.

The last two questions in the text recapitulate the whole and its grounding of life in the letter of the Word, for Saturn asks who invented writing, and then how many kinds of books there are:

Tell me the kinds of books and how many there are.

I tell you, the books of the canon are 172 in all; just as the number of peoples and just as the number of disciples excepting the 12 apostles. A man’s bones are 218 in total number. A man’s veins are 365 in all. A man’s teeth are, in all his life, 32. In 12 months there are 52 weeks and 365 days; in 12 months there are 8700 h. In 12 months you must give your serving man 720 loaves besides breakfast and lunch.

[Saga me hwæt bockinna, and hu fela syndon.

Ic þe secge, kanones bec syndon ealra twa and hundseofontig; eall swa fela ðeoda syndon on gerime and eall swa fela leornyngcnihta buton þam xii apostolum. Mannes bana syndon on gerime ealra cc and xviii. Mannes adder þa beoð ealra ccc and v and lx. Mannes toða beoð on eallum hys lyfe ii and xxx. On xii monðum beoð ii and l wucena and ccc dagena and v and lx daga; on xii monðum beoð þu sealt syllan þinon ðeowan men vii hund hlafa and xx hlafa buton morgemetten and nonmettum.].

The answer to this last moves from the authoritative books of the canon to the peoples of the earth to the bones in the human body to the teeth in one’s mouth and the weeks, days, and hours in a year, finally to arrive at a year’s provision of bread. Surely this last answer may be seen and has been seen to fly off the handle into banal, trivial enumeration. And yet here a question about the written word has led to the literal, physical bread of life. Is it trivial and superficial, or is it esoteric and profound? What is the relationship between the bread that sustains us physically and the bread of Christ’s body? This was—forgive me—a consuming question for centuries of Christian thought. More broadly, Augustine had asserted that scriptural meaning was full of difficult puzzles, and later writers extended this sense to the enigma of the very world. It is striking that the place in Solomon and Saturn II in CCCC 422 where the eucharistic “morsel” is compared to a feast (discussed above) abuts questions of similar polyvalence concerning these same substances of water and then light/fire, specifically associated with the gecyndo of Christ. Here in Southwick, the question about books and bread similarly follows questions about light and water. I think there is a meditation here about the sacramental substance, the nexus of writing, divine light, the water of baptism, the bread of life.

At the least, within Cotton Vitellius A.xv, if the Nowell Codex depicts matters of lands far away and long ago, Southwick’s contents display a complementary curiosity, reaching outward into the limits of the known, to the borders of doctrine and received truth. The composite Vitellius manuscript itself crosses an important disciplinary boundary, the great divide of 1066, with 11th-century Nowell representing the before time, and the 12-century Southwick the after. Belying the self-obsessed Insularity that modernity has sought to inscribe in the “Anglo-Saxon”, both parts of Cotton Vitellius A.xv join one another across the Conquest in gesturing outward, in both time and space. Southwick’s collection of a prosaic Solomon and Saturn with not liturgy (holy language itself) but learned dialogues connecting scriptural authority to the wider world demonstrates Solomon and Saturn’s continued relevance as a tradition, as well as perhaps the fading or dying back, at that time, of poetic vernacular language vis a vis sacramental-liturgical power.

I move now to the third and final

Solomon and Saturn manuscript, having saved the most complex for last. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 41, an eleventh-century compilation, takes only a fragment of the

Solomon and Saturn I poem, and deploys it in a marginal position, not at the front, as in CCCC 422, but in the actual margins of the main text, where it joins an exceedingly varied collection. The interaction in these margins between liturgical language and the poetic

Solomon and Saturn I fragment is rich and fascinating, as I have argued elsewhere and will discuss below.

22 The marginalia appear to be a compendium devoted to the textual mystery of the Word, revealed variously through the varied genres assembled. That such a compilation “shadows” a copy of the Old English Bede—the manuscript’s main text—further suggests a moment in late pre-Conquest Britain in which the revelation of sacred history in a local context has absorbed and syncretized multiple textual traditions. The Latin

Historia has been Englished, and, as I will discuss, edited for a tighter English focus. This English history is then surrounded by pieces and groupings—fragments and assemblages, to quote Bahr—that point inward from the outer edges toward a peculiar Incarnational formulation. Thus, many streams of learning and cultural influence, from Irish liturgy to folk medicine to apocrypha, join with such authoritative textualities as Bede’s.

Solomon and Saturn I is, in this arrangement, but one part, fragment

qua fragment, of a heterogeneous whole.

CCCC 41 contains the most eccentric recension of the Old English Bede, a version Sharon Rowley considers to have originated in the southwest of England in the first half of the eleventh century (private communication related to work in progress). Mildred Budny notes that this version excises extensively, cutting out what does not pertain centrally to England, making it a nativist adaptation—the Brexit Bede. The manuscript, as I have said, is huge compared to CCCC 422 and Cotton Vitellius A.xv. Not that portable at all, at 14x8.5 inches with almost 250 leaves. It was designed with big ambitions, but left unfinished, as Budny and others note well. Perhaps it is in part because of the massive size and unfinished state that someone began to write in the margins. A further feature, however, is the unique metrical colophon at the end of Bede’s text, which calls attention to the book and to further, future writing in a way that certainly gestures toward and may have invited what I have called the “shadow manuscript” in the ample margins:

Bidde ic eac æhwylcne mann

bregorices weard þe þas boc ræde

and þa bredu befo, fira aldor,

þæt gefyrðrige þone writre wynsum cræfte

þe ðas boc awrat bam handum twam

þæt he mote manega gyt mundum synum

[I also ask every man, ruler of a realm, who may read this book and take up its (cover)boards, lord of men, that he prosper the writer with delightful skill who wrote this book with his two hands, that he may finish many yet with his hands…]

As I say, though Fred

Robinson (

1981) saw the “I” as in the voice of Bede, scribal hands do seem to bear the focus here, and may have set the marginal hand in motion. In any event, the marginal writing that wraps, sometimes all the way around, the main Bedan text, is readable as some kind of whole, a contemplative, unorthodox, readerly journey, from liturgical outer edges inward toward a sacramental core. I have called it a shadow manuscript, and a shadow, I think, is an instructive image. The shadow is marginal or peripheral, dependent upon the opacity of a body. But it can also loom and conceal, recalling the shadow or cloud that was a favored image for the concealed presence of the divine, from Classical tradition through early Christian exegesis. Such concealment-cum-revelation, specifically of the mystery of the Incarnate Word, is precisely what, as I argue, CCCC 41’s shadow manuscript performs. It is the covering that allows Christ to be visible in the world.

In these extensive marginalia, we have the same structure of authoritative outer edges surrounding a more surprising core, as mass texts similar to those in CCCC 422 populate the opening pages and those near the end, while the center contains the most interesting things, including the fragmentary beginning of Solomon and Saturn I, but also numerous apparent “mashups”, in Latin and Old English, from exorcisms to healing formulas to homilies. Karen Jolly has done much to bring these texts into view as Christian, not “pagan survivals”, as an earlier generation of scholarship would have done, and I further argue in forthcoming work that these marginalia together form a compilation devoted to the contemplation of the enigmatic Word. The textual “mashups”, echoing the “mashup” that joined Christ’s two natures, offer clues along a path of Incarnational revelation, with the name of the Lord, the nomen sacrum, in a mashup at the physical and spiritual center, embedded in a cluster of four apocryphal or “unreformed” vernacular homilies. Here is the mashup at the center:

Dextera dni fecit virtutem dextera dni exaltavit me non moriar sed vivam &

narrabo opera dni [Psalm 117/118: 16–17]

Dextera glorificata est in virtute dextera man’ tua confringit inimicos & per/pro multitudine_magestatis tue contrevisti adversarios meos misisti iram tuam & commedit eos [Ex 15: 6–7]

Sic per verbo veritatis amedatio sic eris in mundissime spiritus fletus oculorum. tibi gehenna ignis

Cedite. a capite. a capillis. a labiis. a lingua. a collo. a pectoribus ab universis. conpaginibus membrorum eius ut non habeant potestatem diabulus ab homine isto. N. de capite de capillis. nec nocendi. nec tangendi. nec dormiendi. nec tangendi. nec insurgendi. nec in meridiano. nec in visu. nec in risu. nec in fulgendo [illegible digraph—Ac?] effuie.

Sed in nomine domini nri ihu xpi qui cum patre & spiritu sancto vivis & r_ ds_ in unitate spiritu sancti per omnia secula secula seculorum (CCCC 41, p. 272)

[The right hand of the lord has created strength. The right hand of the lord has exalted me. I shall not die but live and tell the works of the lord.

The right hand is glorified in strength. Your right hand destroys enemies and through the greatness of your majesty you have confounded adversaries; you have sent your anger and consumed them.

As through the word of truth from a lie, so will you, unclean spirit of weeping of the eyes (?), be through yourself in(to) the pit of fire.

Depart from the hair, from the lips, from the tongue, from the neck, from the chest, from all the joints of his limbs, so that the devil may not have power over this man, N, of the hair of the head not of harming, nor touching nor rising at noon, nor in seeing nor in laughing nor in flashing, and flee,

But in the name of our lord Jesus Christ who with the father and Holy Spirit lives and reigns god in the unity of the Holy Spirit in every age forever] (tr. mine)

This mashup is made up of multiple parts, from scriptural excerpts to exorcism formulas. Christ as the “right hand” is invoked four times, which is to say, as the sensible instrument of the godhead in the created world. Verbum is then connected to the parts of the human body, evoking the Incarnation, and finally the name itself appears. This mashup, it seems clear to me, is an embodiment of the central Christian mystery, the Word that was made flesh. As I say, it is at the heart of the compilation.

How does

Solomon and Saturn participate in this scheme? This manuscript, CCCC 41, is the only witness to the beginning of

Solomon and Saturn I, as CCCC 422 only bears the end, and the two agree remarkably in their overlap, despite a century between them.

23 The work that the

Solomon and Saturn I fragment is doing in this compilation, I argue, is to introduce the metonymic quality of the Pater Noster and its words (and letters) as they relate to the Logos, the Incarnational goal or prize that we just saw at the center of the compilation. These words of the Word form a signpost on a journey toward the Word, breaking off at the cruciform. T. in the letter-battle sequence, gesturing towards the finding of the cross, which is what eventually follows in the compilation (in the form of an Office for the Invention of the Cross, on pp. 224–25), after a series of formulas for finding what has been lost, on pp. 206–8.

24 Thus, after

Solomon and Saturn I, there are cattle theft mashups with teasing tags

qui quaerit invenit, which lead in to the finding of the cross. After the revelation of the holy name in that central mashup, subsequent texts meditate on the signs of the continued presence of the Word in the world after the Ascension, including a mashup with the famous SATOR formula (p. 329) which joins Christ’s natures as creative force, word, and ultimately human flesh—a shared nature with ongoing redemptive power. One can thus see in CCCC 41’s mashup textuality an extension or even apotheosis of the prosimetric variety of CCCC 422’s dialogues. In CCCC 41, words participate in the mixed or conjoined and enigmatic nature of Christ, revealing him just as his body did when he came into the world.

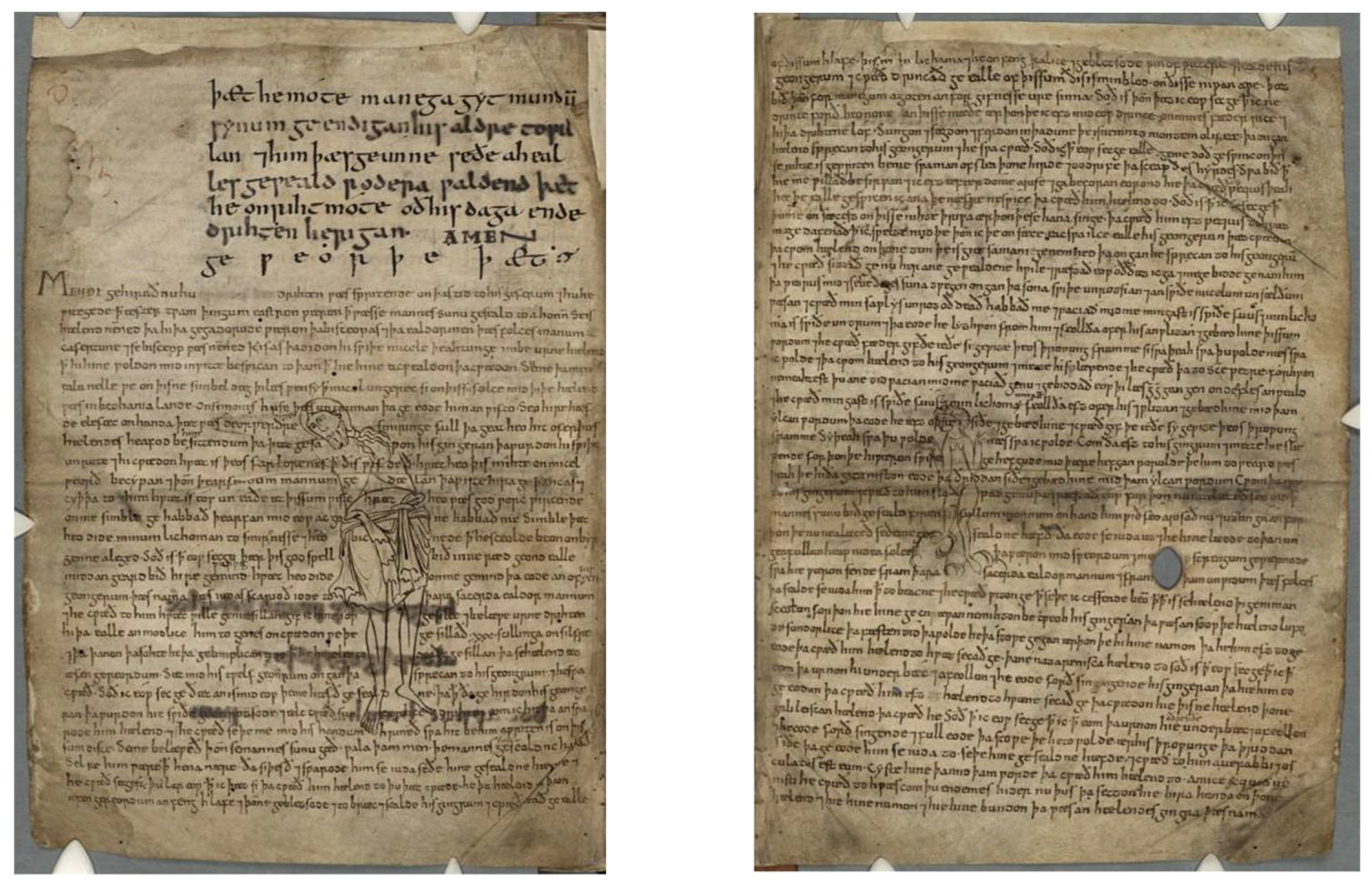

At the end of both the main text and the marginal, Incarnational shadow that I have adumbrated here, CCCC 41 discloses a final manifestation of the Word. Here, after the hapax metrical colophon, taking over the space of the main text, is an Old English homily on the Passion and Ascension, and here, carefully imbricated in that text, are two images. (see

Figure 1).

Most commentators have dismissed these images as having no part in the writing and thus no real role in a semiotics of the spread. But I argue that they are both Christ, first crucified, then glorified and ascending. If we recall that Christ is the Word made flesh, the incompleteness of the images becomes legible in the sense that the images function as “part” of the passion homily’s text, blending into that text in a mutually constitutive tableau. The partially visual, partially textual spread bodies forth in yet another way the central tenet of Christian theology. We see the Word that was made flesh as both word and flesh—that is, word and image—on the literal flesh of the page. In CCCC 41, Solomon and Saturn participates in an extremely heterotextual Incarnational poetics, beyond the prosimetrum of CCCC 422 and fundamentally different from the semiotic and compilational principles of the Southwick Codex of Cotton Vitellius A.xv.

What all three manuscript witnesses of Solomon and Saturn share, it seems to me, is that these dialogues represent ways “in” to deeper knowledge of authoritative writing or doctrine. Just as Saturn’s questing figure seeks dialogue with the iconic and authoritative Solomon, the dialogues seek to know the special power of the liturgy, the weird metaphysics of the sacrament, the equally weird historical “reality” of scripture and textuality of history, the enigmatic duality of a god who became a man, whose nature could be further revealed by the enigmatic properties of words. Their modes of knowing are hybrid and their assertions heterodox, but Ælfric’s acerbic disapproval of such things should not so readily win our acquiescence. First composed perhaps in the first third of the tenth century, the dialogues of Solomon and Saturn were adjoined to the liturgy by the eleventh century and reiterated in a more rarefied, encyclopedic form in the twelfth. We may see in this trajectory a familiar process in historical linguistics and perhaps in history itself, by which what begins as a potent form is gradually drained of its force. In the case of the Dialogues of Solomon and Saturn, this power was related to the divine itself, to the mysteries of a Word that had spoken creation and had even infused that creation through its incarnation. The joining of Solomon and Saturn’s potent poetics to the liturgy in both CCCC 422 and CCCC 41 speaks to the eleventh century’s continued recognition of the dialogues’ special nature—an aura that persisted even into the Renaissance in the case of CCCC 422. By the twelfth century, the dialogues are rewritten and recontenxtualized. No longer themselves performative of certain esoteric truths related to the Word, the utterances of the Prose Solomon and Saturn of the Southwick Codex instead refer. Still, they explore the nature of the sacramental substance, in ways remarkably similar to the poetic Solomon and Saturn.

The poetics of enigma or poetics of the Incarnation that scholars of later medieval English writing have recently emphasized as a peculiar feature of the period should perhaps be reconsidered as having a longer history. What the three manuscripts of Solomon and Saturn suggest is that poetic experiments related to the Word were part of the literary landscape of the earliest phases of Christianity in Britain, and that subsequent stages of reform and upheaval may have cast these experiments in different lights and made necessary first new contexts and eventually entirely new forms. I would suggest as an avenue for future research some comparative work regarding the “monastic poetics” that Niles and O’Camb identify in the later-tenth-century Exeter Book and the Incarnational poetics I have described in CCCC 422 (Part I, early tenth c.) and CCCC 41 (eleventh c.). Do these compilations represent mostly chronological development, or do they suggest geographic and/or socio-cultural distinctions? Seen together, do they arbitrate in any way the disagreement between Niles and O’Camb regarding the probable origin and compiler-authorship of the Exeter Book? The CCCC 422 Solomon and Saturn compilation certainly strikes a less “reformist” pose, suited perhaps to its earlier date but perhaps also to some aspect of its geographic origins, though I do not have a fully formed opinion of what those may be. Does the Incarnationalism and strict “localism” of CCCC 41 reflect a recalcitrance or resistance to reformist sensibilities? An admiring response to monastic poetics? Regardless, an impulse to encounter the divine in the form of poetic words should perhaps be recognized as a basic one that asserts itself again and again in the English tradition, despite frequent disapproval from authority.