Old English Enigmatic Poems and Their Reception in Early Scholarship and Supernatural Fiction

Abstract

1. Early Scholarship: Obscurities Made Intelligible

Brooke’s Cynewulf is a forerunner of the Romantics and the Exeter Riddles are the exuberant nature poetry he wrote in his youth (composed at the age of about twenty-five, before some unknown downturn in fortune darkened his subject matter and genre preferences43). In reference to what he takes as the badger of Riddle 15, for instance, Brooke notes:… imagine a wandering singer coming through the untilled woodland to one of the villages, to sing his songs, and to pass on to another. […] Then, our wandering singer (whom I will now call Cynewulf, because all the illustrations of village life which I shall quote are from his riddles), listening, heard the rushing of the water past the wattled weirs built out from its sides for the fishing, and saw the bridge of wood that crossed it, and perhaps mills by its side that ground the corn of the settlement, and thinking of the millstone made it the subject of his fifth riddle.

Brooke goes further than most to extract from the Exeter Riddles not only a name but a local habitation (“he was well acquainted with a storm-lashed coast”45) and indeed a full personality and turbulent biography. Not all accounts were quite so fanciful, but the Cynewulfian theory of riddle authorship enjoyed widespread acceptance in the scholarly world, retaining adherents decades after its premises were dismantled.46It is in these short poems—in this sympathetic treatment of the beasts of the wood, as afterwards of the birds; in this transference to them of human passions and of the interest awakened by their suffering and pleasure—that the English poetry of animals begins. […] His sympathy is even more than that of Shakspere in his outside description of the horse or the hare. The note is rather the note of Burns and Coleridge […].

A century and a decade earlier, Mary Bentinck Smith (1864–1921)—at the time, Director of Studies and Lecturer in Modern Languages at Girton College—would also highlight riddling encounters with the nonhuman, which she links to paganism and a more sinister sense of English landscape:The argument that I draw from these areas of focus is that,although things are endowed with voices in Anglo-Saxon literatureand material culture, they also have an agency apart fromhumans. This agency is linked to: one, their enigmatic resistance,their refusal to submit to human ways of knowing and categorisingthe world; and, two, their ability to gather, to draw together,other kinds of things, to create assemblages in which human andnonhuman forces combine. Anglo-Saxon things speak yet they canbe stubbornly silent. They can communicate with humans but, likeriddles, they also elude, defy, withdraw, from us.

“in [the Old English riddlers’] hands inanimate objects become endowed with life and personality; the powers of nature become objects of worship such as they were in olden times; they describe the scenery of their own country, the fen, the river, and the sea, the horror of the untrodden forest […]”

2. M.R. James and the Voice of the Whistle

- O Whistle, and I’ll come to you, my lad;

- O whistle, and I’ll come to you, my lad:

- Tho’ father, and mither and a’ should gae mad,

- O whistle, and I’ll come to you, my lad.

|

| M.R. James, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (London: Edward Arnold, 1904), p. 199. |

| Photo by the author, from a copy of the first edition, Eton College Archives, Lq.4.06. |

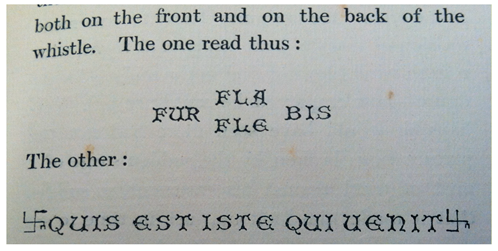

A curious detail here is Parkins’s assumption that a medieval word for whistle might be relevant to construing the inscription. This suggests an awareness (whether we want to attribute that awareness primarily to Parkins or to James) of the penchant for medieval inscribed objects to name themselves, as does, for example, the Brussels Cross (“Rod is min nama”, “Cross is my name”) and a comb-case discovered in 1867 (“kamb: koþan: kiari: þorfastr”, “Thorfast made a good comb”).74 Often such inscriptions take on the voice of the object itself, as in the case of the ninth-century Alfred Jewel (“ÆLFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN”, “Alfred ordered me made”75), or the Sutton Brooch (eleventh century) which, like James’s whistle, offers a warning to thieves:“I ought to be able to make it out”, he thought; “but I suppose I am a little rusty in my Latin. When I come to think of it, I don’t believe I even know the word for a whistle. The long one does seem simple enough. It ought to mean, ‘Who is this who is coming?’ Well, the best way to find out is evidently to whistle for him”.

It is this similarity of speaking objects that has led many scholars to link such inscriptions to the Old English riddling genre, which makes such effective use of prosopopoeia in first-person texts challenging solvers to “saga hwæt ic hatte”, or “say what I am called”.77 Of course, the inscription on James’s whistle does not speak in the first person, but only enigmatically inquires, “quis est iste qui uenit”, “Who is this who is coming?” Yet, the disembodied voice of the object does manage to speak for itself in the title of the tale, detached and floating ominously on the epigraphical edges: “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You …”78AEDǷEN ME AGE HYO DRIHTENDRIHTEN HINE AǷERIE ÐE ME HIRE ÆTFERIEBUTON HYO ME SELLE HIRE AGENES ǷILLES(Aedwen owns me, may the Lord own her. May the Lord curse him who takes me from her, unless she gives me of her own free will”.)

If some explanation along these lines is accepted, the poem is an unusually complex example of the “phenomenon of ‘voices within voices,’” notable as a curious feature of the Exeter Anthology.82 Of course, it is possible that such voices would not have been quite so bewildering to a medieval audience.83 Yet as “eavesdroppers” into this cryptically intimate communication—via a split voice at once carved into solid wood and yet mysteriously disembodied—many modern readers have found The Husband’s Message to be exceptionally obscure, even by the standards of this manuscript.84 And this quality may be what inspired James to create his own parallel object, complete with its own alien and disembodied voice that beckons menacingly from beyond.… the five runes [are] the actual message supposed to have been carved into the wood and sent to the wife. They may represent a secret cypher previously agreed upon by husband and wife; in any case, it is clear that we cannot be expected to regard the whole seventy lines of the poem as having been inscribed on a runakefli. If this assumption is correct the poem may properly be deemed an explanation of the terse runic message in greatly expanded form. This expansion allows the inclusion of the wood’s own history as well as the more detailed exposition of the actual situation of husband and wife and the message sent by the former.

Pipe and hwistle were also the names of instruments of the flute order, for tibicen is glossed as pipere oððe hwistlere, and auledus as reodpipere. The reed-pipe is the subject of the sixty-first riddle.

The central conceit here is the riddling motif of “mouthless” speech, and many have found in this text a clear reference to writing, whether in the form of runes inscribed on a slip of wood, or as penmanship accomplished with a sharpened reed. The paradoxes of written and spoken language are a well-studied theme of Exeter riddling, where the whispering quality of all writing often overlaps with playful games of runic concealment.95 Riddle 60 seems in tune with that theme, yet the clue of speaking among mead-drinkers is a point in favor of a musical instrument. An elegant way around this impasse, as Niles has established, comes when we “answer the riddles in their own tongue”, so that the single Old English word hreod can encapsulate the protean identity of the reed—a cylindrical creature that can “speak” both as pen and as whistle.96Ic wæs be sonde, sæwealle neah,æt merefaroþe minum gewunadefrumstaþole fæst; fea ænig wæsmonna cynnes þæt minne þæron anæde eard beheolde,ac mec uhtna gehwam yð sio brunelagufæðme beleolc. lyt ic wendeþæt ic ær oþþe sið æfre sceoldeofer meodu[drincende] muðleas sprecan,wordum wrixlan. þæt is wundres dæl,on sefan searolic þa þe swylc ne conn,hu mec seaxes ord 7 seo swiþre hond,eorles ingeþonc 7 ord somod,þingum geþydan, þæt ic wiþ þe sceoldefor unc anum twam ærendspræceabeodan bealdlice, swa hit beorna mauncre wordcwidas widdor ne mænden.[My home was on the beach near the sea-shore;/Beside the ocean’s brim I dwelt, fast fixed/In my first abode. Few of mankind there were/That there beheld my home in the solitude,/But every morn the brown wave encircled me /With its watery embrace./Little weened I then that I should ever, earlier or later,/Though mouthless, speak among the mead-drinkers/And utter words. A great marvel it is,/Strange in the mind that knoweth it not,/How the point of the knife and the right hand,/The thought of a man, and his blade therewith,/Shaped me with skill, that boldly I might/So deliver a message to thee/In the presence of us two alone/that to other men our talk/May not make it more widely known.]

The secret notes of the reed-flute, of course, easily mingle with the beckoning message of The Husband’s Message, once these texts are merged by Blackburn. In James’s hands, at any rate, the scene turns to horror, and countless critics have emphasized the atmospheric brilliance of the tale, set in the seaside resort town of Burnstow, a lightly disguised version of Felixstowe on the Suffolk coast.98 James’s word-painting in the tale is indeed lovely:It tells of a desert place near the shore, traversed by a channel up which the tide flowed, and where the reeds grew which were made into the Reed-Flute, which is the answer to the riddle. I translate the whole. The picture, at the end, of the lover talking in music to his sweetheart, music that none understood but she, is full of human feeling, but the point on which I dwell is the scenery. It is that of a settlement where only a few scattered huts stood amid the desolate marsh.

Such “local colour” noted by Benson at the tale’s first reading has subsequently been analyzed time and again in terms of its “agoraphobic sea horizons;” “the cumulative forces of the eerie that animate the East Anglian landscape;” the way it evokes “the windswept mystery of the barren unknown”.99 Such characterizations are in no way to be dismissed; James’s fiction is certainly rooted in an English landscape he personally experienced and found deeply evocative, but it is also informed by his engagements with medieval studies, and here the sense of the enigmatic looms large. Even the “shape of a rather indistinct personage”, the “bobbing black object” conjured on the shoreline by the whistle, behaves quite like an unresolved riddle creature, declaring its own incongruous form for the solver’s contemplation: “a little flicker of something light-coloured moving to and fro with great swiftness and irregularity. Rapidly growing larger, it, too, declared itself as a figure in pale, fluttering draperies, ill-defined”.100Bleak and solemn was the view on which he took a last look before starting homeward. A faint yellow light in the west showed the links, on which a few figures moving towards the club-house were still visible, the squat martello tower, the lights of Aldsey village, the pale ribbon of sands intersected at intervals by black wooden groynes, the dim and murmuring sea.

Readers familiar with Riddle 30b will notice Blackburn has emended MS “ligbysig” (“flame-busy”, likely reflecting the capacity of wood to burn) with “licbysig”, “agile of body” (a reading in which Blackburn ultimately followed Thorpe, who translated the half-line as “I am a busybody”).103 James’s whistle ghost is also quite agile:ic eom licbysig, lace mid windew[unden mid wuldre we]dre gesomnad[I am agile of body, I sport with the wind. I am clothed with beauty, a comrade of the storm].

Such uncanny movements match the bewildering effects of Riddle 30b: “þon ic mec onhæbbe/hi onhnigað to me/modgum miltsum” (“when I rise up, before me bow/The proud with reverence”).105 Proud men also kiss the creature of Riddle 30b, a fate the arrogant Parkins nearly suffers before the amorphous, wind-sporting horror collapses into “a tumbled heap of bed-clothes”.106It would stop, raise arms, bow itself toward the sand, then run stooping across the beach to the water-edge and back again; and then, rising upright, once more continue its course forward at a speed that was startling and terrifying.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Most recently in (Niles 2015) and (Niles 2016), but in numerous other publications as well, including the co-edited collections (Niles 1997) and (Niles and Frantzen 1997). |

| 2 | See (Matthews 2006, pp. 9–22). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | (Crossley-Holland and Sail 1999), No. 44 (solved as “the past”). |

| 5 | For James’s reticent style, see for example (Briggs 1977; Sullivan 1978; Cavaliero 1995; Cavallaro 2005; Brewster 2012, esp. at 46); etc. James explicitly commented on this strategy: “The reading of many ghost stories has shown me that the greatest successes have been scored by the authors who can make us envisage a definite time and place, and give us plenty of clear-cut and matter-of-fact detail, but who, when the climax is reached, allow us to be just a little in the dark as to the working of their machinery”, (James 1929, p. 172). For my attempt to connect the scholarly and creative work of James, see (Murphy 2017). For more on the relationship between James’s academic career and his fiction, see (McCorristine 2007). |

| 6 | A good introduction to the range of Tolkien’s sources is provided in (Anderson 2002, pp. 120–31.) |

| 7 | Even the very best critical assessments of riddling in The Hobbit have not always taken such contexts into account. I am in agreement with John D. Rateliff that work here remains to be done: “Careful examination of Old English [riddle] sources, and the contemporary critical literature of the first third of this century debating their correct interpretation, would probably shed a good deal of light on Tolkien’s exact sources and his treatment of them”, (Rateliff 2007, p. 171). |

| 8 | A phrase taken from (Niles 2006). |

| 9 | (Conybeare 1826, p. 213). As Niles (Idea of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 199) notes, it is often difficult to separate the voice of John Josias from that of William Daniel, who edited his brother’s work posthumously. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | In Thomas Wright’s Biographia Britannica Literaria (London, 1842), we read: “From their intentional obscurity, and from the uncommon words with which they abound, many of these riddles are at present altogether unintelligible” (79). In The Anglo-Saxon Home: A History of the Domestic Institutions and Customs of England (London, 1862), John Thrupp provides yet another version of this pattern: “A very large number of their riddles have been preserved, but partly owing to their original obscurity, and partly from their having been copied and re-copied by persons evidently ignorant of the Anglo-Saxon language, and from our imperfect knowledge of it, the bulk of them are unintelligible to the best scholars” (Thrupp 1862, pp. 386–87). By (Wyatt 1912), some progress had been made, but the challenge remained: “I have cared greatly to try and evolve a more intelligible text in the many whole passages that were yet obscure” (v). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Niles, God’s Exiles, 6, p. 153. |

| 15 | Unless indicated elsewhere, I myself will here follow the numbering of (Krapp and Dobbie 1936). |

| 16 | See (Neville 2019); (Cavell and Neville 2020, esp. at xiv–xvvii and 5–6). My own reservations about accepting this proposal may be found in a review of the latter volume in the Journal of English and Germanic Philology (forthcoming). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | For the remarkable story of Hickes, his collaborators, and the Thesaurus, see (Niles 2015, pp. 147–58). See also (Harris 1992). |

| 19 | Hickes, Thesaurus, vol. 1, pp. 142–43; vol. 2, p. 186. |

| 20 | (Niles 2015, p. 152.) See also (Lerer 2001). |

| 21 | Hickes, Thesaurus, vol. 1, p. 221. See (O’Camb 2018). |

| 22 | For the backstory of these “runic additions”, see (Harris 1992, p. 61–63). |

| 23 | (Niles 2015), 179. James was to draw on similar runic overtones for his tale “Casting the Runes”, which itself is an apparent inspiration for the Japanese horror film Ringu, with its various remakes and sequels. See (Murphy 2017, pp. 58–74). |

| 24 | “quum literæ, tum voces verè runicæ, hoc est mysticæ et occultæ”: (Hickes 1703–1705), vol. 2, figures IV-VI (with accompanying commentary on pp. 4–5). That Hickes desires to highlight this enigmatic sense of a first-person “runic voice” is perhaps reflected in his decision to include here the cryptographic—though strictly speaking, non-runic—Riddle 36 (f. 109v in the Exeter Book), which is headed by a prominent capitalized “Ic”. By contrast, Hickes ultimately elected not to include here the nearby runes (f. 123v) of The Husband’s Message, which he had also marked in the Exeter Book with penciled notation. |

| 25 | “etiam rem aliquam, sive personam tanquam monstrum describit, cuius nomen in runiis ænigmatice ponitur”: (Hickes 1703–1705, vol. 2, p. 5.) Although he does not attempt to answer Riddle 24, Hickes’s general assessment of it aligns with present-day consensus opinion (which takes the rearranged runes of this riddle to spell “OE higoræ”, or “magpie, jay”). |

| 26 | “Qui vero hæc omnia præsertim tot à se visa adeo mystice describit, dramatis persona est, quæ de se etiam multa ænigmatice dicit”: (Hickes 1703–1705, vol. 2, p. 5.) |

| 27 | |

| 28 | For the Conybeare brothers and the Illustrations, see (Niles 2015), 198–204; (Jones 2018), 1–3 and passim. |

| 29 | Conybeare, Illustrations, pp. 208–13. |

| 30 | Ibid, pp. lxxvii–lxxxv. |

| 31 | Ibid, p. 209. |

| 32 | See (Niles 2015, pp. 223–29). |

| 33 | Thorpe, Codex exoniensis, p. 527. |

| 34 | Ibid, pp. 527, 403. |

| 35 | Ibid, p. 527; (Niles 2015, p. 229). |

| 36 | Ludvig Müller had offered “scutum” (“shield”) for Riddle 5 and “liber” (“book”) for Riddle 26 in his (Müller 1835, p. 63). |

| 37 | |

| 38 | |

| 39 | In the same year, Jacob Grimm had announced the identical discovery, but it seems as though Grimm had unintentionally appropriated the idea from Kemble. See (Dilkey and Schneider 1941), at 468. |

| 40 | (Leo 1857). |

| 41 | |

| 42 | (Brooke 1892, p. 145). For more on Brooke, see (Niles 2016, pp. 10–12). |

| 43 | See Cynewulf’s reconstructed career in (Brooke 1892, pp. 374–77). |

| 44 | |

| 45 | (Ibid, p. 372). |

| 46 | For details, see (Williamson 1977, pp. 5–6). |

| 47 | |

| 48 | In addition, see (Karkov 2011, pp. 25, 152, 219, and in general chp. 4) “Object and Voice” (pp. 135–78); (Tilghman 2014). |

| 49 | Paz, Nonhuman Voices, 6. |

| 50 | |

| 51 | Bentinck Smith, “Christian Poetry”, 66; M.R. James, “Latin Writings in England to the Time of Alfred”, in (Bentinck 1907, pp. 72–96, at 85). In acknowledging Bentinck Smith as James’s colleague, I am not suggesting that she enjoyed the same privileges at Cambridge. On the contrary, for some details of the specific obstacles Bentinck Smith faced in her academic career, see (Dyhouse 1995), at 471. It should also be noted that James himself was an outspoken opponent of the equal rights of women at Cambridge: see (Jones and James 2011, pp. xiv–xv; Murphy 2017, pp. 145–57). |

| 52 | (James 1911), front matter. |

| 53 | Endpaper advertisement in (Glover 1904). |

| 54 | |

| 55 | James wrote of Humfrey Wanley, “His work is of so high a quality that it cannot be passed over. It has been for two centuries indispensable to the students of Anglo-Saxon”: quoted in (Pfaff 1980), p. 270. Pfaff notes that James “undoubtedly […] consulted the older master at each relevant MS”. Indeed it is just possible that Wanley’s given name receives a nod in the title character of James’s later story “,Mr. Humphreys and his Inheritance”, a tale that turns on prominent metaphors of library cataloguers in haunted labyrinths. For more on this story, see (Murphy 2017, pp. 140–45). |

| 56 | Cited in (Pfaff 1980, p. 128). |

| 57 | |

| 58 | (Pfaff 1980, p. 270, n. 24), notes that James’s work on manuscripts containing Old English “reveals in a most impressive way how much his eye—which was not that of a trained ‘Saxonist’—caught”. |

| 59 | |

| 60 | Cited in (Cox and James 2009, p. 312). I agree with Cox and with (Jones and James 2011, p. 435), that “‘Oh, Whistle,’” was “probably written 1903; first read Christmas 1903”. This date is based on the account of H.E. Luxmoore (James’s Eton tutor and lifelong friend) who records hearing James read the story “Fur flebis” during the 1903 Christmas season at King’s College (Letters of H.E. Luxmoore, 113). As noted above, Luxmoore seems to be corroborated by the diary entry of A.C. Benson for December 1903. Inserted into a copy of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (Eton College Archives Lq.4.07) are notes in the hand of James memoirist Shane Leslie stating that “‘Oh, Whistle’” was “read at Christmas 1902”. It seems unlikely, however, that James would have read the same story two Christmas seasons in a row, especially since many of the same men made up his audience each year. A partial record of James’s original audience is found written on the blank spaces of a copy of the Greek New Testament, which served for James as a “kind of diary”: Cambridge University Library MS Add 7517. At any rate, the question of whether the story was written and read in 1902 or 1903 makes no difference to the argument I am presenting here. |

| 61 | James, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, p. 200. |

| 62 | James, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, p. 183. |

| 63 | For example, the work on the Exeter Riddles in (Paz 2017) is indebted (see p. 4) to (Bogost 2012), which includes a chapter on “Ontography: Revealing the Rich Variety of Being” that opens with a discussion of James’s “Oh, Whistle”. Both Bogost and Paz (pp. 4, 16, 45) are influenced by the object-oriented philosophy of Graham Harman, who explicitly borrows the term “ontography” from James’s “Oh, Whistle” in (Harman 2011, p. 124). |

| 64 | (Morton and Klinger 2019, p. xiii). Such assessment of the influential importance of this story is a widespread critical commonplace and it seems unnecessary to multiply references here. In general, James’s fiction is credited with having “established the template that the other writers—consciously or not—would follow” in various sub-genres of horror fiction and film: (Fisher 2012, p. 21). The influence of James’s “Oh, Whistle” is often acknowledged by modern masters of supernatural fiction through frequent allusion and homage. For instance, Susan Hill’s contemporary classic The Woman in Black (1983, subsequently adapted for television, a major motion picture, and the second-longest running stage play in West End theatre history) has titled its climactic chapter, “Whistle and I’ll Come to You”, while Michael Chabon declares James’s tale to be “one of the finest short stories ever written”: (Chabon 2009), p. 121. Stephen King’s most recent horror novel, Later (London: Titan Books, 2021), adopts as its central feature the idea of whistling up a malevolent ghost: “‘I told it what you told me to say, Professor. That if I whistled, it had to come to me. That it was my turn to haunt it” (166). Even the newest Ghostbusters film (Ghostbusters: Afterlife, November 2021) features a ghost-sensitive whistle. |

| 65 | (Lane 2012, p. 105). Lane notes that “Oh, Whistle” is “by general consent, his finest and most anxiety-shrouded work” (108). It is impossible here to make a full case that this story was a turning point in James’s development of a more “reticent” approach, but many of his earlier stories do seem to involve more overt, lurid demonic horrors (“Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book”, 1893) or even diabolical surgery (“Lost Hearts”, 1893), while many stories that follow take a more “enigmatic” approach, echoing many elements of “Oh, Whistle”. For example, “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas” (1904) is organized quite explicitly around riddling effects (see Murphy 2017, pp. 31–40), while the next tale James is known to have written, “A School Story” (1906) echoes even more precisely the riddle of the whistle (see below). In “The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral”, (first published in The Contemporary Review in 1910) James seems to return to Old English prosopopoeia as a source of ghostly voicing. That tale concludes with a poem, which is reported to have been “drempt” and recorded on a scrap of paper found concealed within the carving. There can be little doubt James found inspiration in The Dream of the Rood (as well as the Exeter Riddles and object inscriptions, such as the Brussels reliquary) for the opening lines of this “dream”: “When I grew in the Wood/I was water’d wth Blood/Now in the Church I stand…”: (James 1911, p. 166). Though not in quite the same way, Beowulf also seems to have played a role in James’s post-war classic, “A Warning to the Curious” (1925): see (Edwards 2013; Murphy 2017, pp. 165–84). |

| 66 | James, “Some Remarks”, p. 171. |

| 67 | My own previous work on this story has focused on unriddling the famous crux of the whistle’s inscription (see below), but in that discussion I overlooked the connection to the Exeter Book and its scholarly reception explored here. The present discussion, then, may be considered a companion to (Murphy 2017, pp. 40–51). |

| 68 | (Smith 1879, p. 185). That James here links Old English poetry with the works of Burns of course raises specters of great ideological complexity, given that Scots was often regarded by 18th- and 19th-century authorities as “a dialect of the Saxon or Old English with some trifling variations” or even a “purer” form of Old English than had survived in modern standard English: see (Kidd 2002), quoted at 25. The use of local eye-dialect in “Oh, Whistle” (“‘Ow, I see it wive at me out of the winder’”) only underscores that link, the potential Unionist implications of which might well have had some appeal to the politically conversative James (see Pfaff, Montague Rhodes James, 99, 397). At any rate, the comparison of Burns to the Exeter Book was not without precedent: (Wright 1842, p. 79) solves Riddle 28 as “John Barleycorn”, which (Brooke 1892, p. 152), accepts, citing the full text of Burns’s famous version of the song. |

| 69 | |

| 70 | |

| 71 | See (Murphy 2017, pp. 45–51). Recent editions have begun to restore the original fylfots. For example, see (James 2017) and (Morton and Klinger 2019). |

| 72 | |

| 73 | |

| 74 | Cited and translated in (Page 1973, p. 194). |

| 75 | Cited and translated in (Karkov 2011, p. 161). |

| 76 | Cited and translated in (Karkov 2011, p. 158). For more on such inscriptions, see also (Bredehoft 1996). An echo of the formula of “N me fecit” shows up in James’s late tale, “The Malice of Inanimate Objects” (1932), where a man is menaced by a kite bearing the letters “I.C.U”.: see (Jones and James 2011, pp. 397–400, at 399 and 400). |

| 77 | This signature “I-You” riddling dynamic has recently been emphasized by (Frederick 2020, pp. 230–31). |

| 78 | This particular effect has been often imitated, as in the title of Sarah Perry’s deliciously vicious tale, (Perry 2017). |

| 79 | See (Niles 2006, pp. 225–34). |

| 80 | See for example (Leslie 1961, pp. 13–15; Williamson 1977, p. 315; Klinck 1992, p. 57), considers the question unanswerable. Cf. (Niles 2006), pp. 225–34. |

| 81 | (Elliott 1955, pp. 1–8, at 5). (Niles 2006, pp. 232–33), argues that the speaker is “the ship’s personified mast” and further explains “The voice that issues from the ship itself calls attention to the runes as material signs while at the same time, apparently, sounding out either their names or their phonetic values”. |

| 82 | |

| 83 | (Schaefer 1991, pp. 124–25), accounts for the prominence of the “poetic I” in Old English poetry in the context of early medieval vocality and the necessity of rendering texts in performance intelligible to contemporary audiences via a “vicarious voice”. |

| 84 | |

| 85 | The first and most sensible answer to the question of “why a whistle?” is surely “why not?” However, it is true that many other explanations for James’s whistle continue to proliferate, ranging from the folklore of Jutland to an accident involving a friend of James who is said to have died from a fall when his horse was spooked by a whistle-like sound. See (Simpson 1997, pp. 9–18), at 15; (Rigby 2020). Later writers of fiction indebted to James allude to the folkloric idea so often that it may indeed now be gaining currency: “They say that if you whistle, the souls of the dead will draw nearer”: (Paver 2010, p. 96). |

| 86 | |

| 87 | By 1903, James may well have already begun work on his discussion of Aldhelm’s enigmas for the Cambridge History published in 1907. |

| 88 | As (Lees and Overing 2019, at p. 59), remark: “What is at stake here, finally, is a message about an internalized conversation to which no-one else is privy”: |

| 89 | |

| 90 | For instance, (Orchard 2021, p. 439), notes that “it is not at all clear that [Riddle 60] is not part of The Husband’s Message”. For a recent wholesale reevaluation of textual divisions in this part of the Exeter Book, see (Ooi 2021). |

| 91 | |

| 92 | |

| 93 | (Padelford 1899, p. 51). Of course, by “sixty-first riddle”, Padelford means Riddle 60. |

| 94 | In keeping with my argument, it seems most appropriate to present the edited text and its translation as it appears in (Blackburn 1900, pp. 6–9). |

| 95 | |

| 96 | |

| 97 | |

| 98 | In his introduction, (James 1931), at p. viii. identifies Burnstow as Felixstowe. |

| 99 | (Armitt 2016, pp. 95–108, at 99; Macfarlane 2015), citing Mark Fisher in a 2013 audio essay; (Thompson 2021, p. 1). |

| 100 | James, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, 195, pp. 204–5. (Paz 2020, at p. 205) has compellingly argued that the Exeter collection’s opening storm riddles serve as a meta-riddlic reflection on the genre’s effects on the solver’s mind: “Just as we try to articulate a solution and close the game down, the riddle carries on, swept away by the storm”. |

| 101 | |

| 102 | Text and translation as presented in (Blackburn 1900, pp. 6–7), with Blackburn’s “breeze” altered to “wind”. |

| 103 | |

| 104 | |

| 105 | Text and translation as presented in (Blackburn 1900). |

| 106 | (James 1904, p. 223). See Riddle 30b, line 6: “þær mec weras ond wif wlonce gecyssað”, “where proud men and women kiss me”. |

| 107 | See (James 1904, p. 198): “he stopped for an instant to look at the sea and note a belated wanderer stationed on the shore”. |

| 108 | I cannot resist pointing out, however, one more curiosity. The whistle is discovered specifically when Parkins investigates a section of the ruin disturbed by activity that is never explained: “a patch of the turf was gone—removed by some boy or other creature ferae naturae”. Why has some unknown person been scratching at the turf? I will only note that the most obvious way to anagram the runes of The Husband’s Message yields “sweard”, or “turf”, a word that has made frustratingly little sense to scholars attempting to interpret the Old English poem, no matter how hard they scrape at its surface. |

| 109 | James wrote, “I count it no depreciation of an author to show that some old tale may have been at the back of his mind when he was devising his new one”: (James 1924, p. xii). |

References

- Alington, Cyril. 1934. Lionel Ford. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Douglas A. 2002. The Annotated Hobbit. Illustrated by John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Armitt, Lucie. 2014. Twentieth-Century Gothic. In Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination. Edited by Dale Townshend. London: The British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Armitt, Lucie. 2016. Ghost-al Erosion: Beaches and the Supernatural in Two Stories by M.R. James. In Popular Fiction and Spatiality: Reading Genre Settings. Edited by Lisa Fletcher. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bentinck, Smith M. 1907. Old English Christian Poetry. In The Cambridge History of English Literature. Volume 1: From the Beginnings to the Cycles of Romance. Edited by Adolphus William Ward and Alfred Rayney Waller. London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, pp. 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, Francis Adelbert. 1900. The Husband’s Message and the Accompanying Riddles of the Exeter Book. The Journal of Germanic Philology 3: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bogost, Ian. 2012. Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bredehoft, Thomas A. 1996. First-person Inscriptions and Literacy. Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology 9: 103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster, Scott. 2012. Casting an Eye: M. R. James at the Edge of the Frame. Gothic Studies 14: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, Julia. 1977. Night Visitors: The Rise and Fall of the English Ghost Story. London: Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, Stopford A. 1892. The History of Early English Literature. London: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Cavaliero, Glen. 1995. The Supernatural and English Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, Dani. 2005. The Gothic Vision. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Cavell, Megan, and Jennifer Neville, eds. 2020. Riddles at Work in the Early Medieval Tradition: Words, Ideas, Interactions. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chabon, Michael. 2009. Maps and Legends: Reading and Writing along the Borderlands. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Conybeare, John Josias. 1826. Illustrations of Anglo-Saxon Poetry. Edited by William Daniel Conybeare. London: Harding and Lepard. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Michael. 1983. M.R. James: An Informal Portrait. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Michael, and Montague Rhodes James, eds. 2009. Casting the Runes and Other Ghost Stories. Oxford: Oxford’s World Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley-Holland, Kevin, and Lawrence Sail, eds. 1999. The New Exeter Book of Riddles. London: Enitharmon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison, Lynda, ed. 2001. The Legacy of M.R. James: Papers from the 1995 Cambridge Symposium. Donington: Shaun Tyas. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Franz. 1859. Die Räthsel des Exeterbuchs: Würdigung, Lösung und Herstellung. Zeitschrift für deutches Altertum 11: 448–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Franz. 1865. Die Räthsel des Exeterbuchs: Verfasser; Weitere Lösungen. Zeitschrift für deutches Altertum 12: 232–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dilkey, Marvin C., and Heinrich Schneider. 1941. John Mitchell Kemble and the Brothers Grimm. Journal of English and Germanic Philology 40: 461–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dinshaw, Carolyn. 2012. How Soon Is Now? Medieval Texts, Amateur Readers, and the Queerness of Time. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dyhouse, Carol. 1995. The British Federation of University Women and the Status of Women in Universities, 1907–1939. Women’s History Review 4: 465–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Anthony Stockwell Garfield. 2013. ‘A Warning to the Curious,’ and Beowulf. Notes & Queries 60: 284. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Ralph W. V. 1955. The Runes in ‘The Husband’s Message. Journal of English and Germanic Philology 54: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Mark. 2012. What is Hauntology? Film Quarterly 66: 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, Jill. 2020. Performance and Audience in the Exeter Book Riddles. In The Wisdom of Exeter: Anglo-Saxon Studies in Honor of Patrick W. Edited by Edward J. Christie. Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 227–41. [Google Scholar]

- Glover, Terrot Reaveley. 1904. Studies in Virgil. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Gollancz, Israeland. 2011. The Exeter Book, An Anthology of Anglo-Saxon Poetry. Part I. London: Early English Text Society. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, Graham. 2011. The Quadruple Object. Winchester: Zero Books. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Richard L., ed. 1992. A Chorus of Grammars: The Correspondence of George Hickes and His Collaborators on the Thesaurus Linguarum Septentrionalium. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Mary. 2008. The Talking Dead: Resounding Voices in Old English Riddles. Exemplaria 20: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickes, George. 1703–1705. Linguarum Veterum Septentrionalium Thesaurus Grammatico-Criticus et Archaeologicus. 2 vols. Oxford: E Theatro Sheldoniano. [Google Scholar]

- Ibitson, David A. 2021. Golf and Masculinity in M. R. James. In The Palgrave Handbook of Steam Age Gothic. Edited by Clive Bloom. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 809–26. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes. 1904. Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes. 1911. More Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes. 1924. Introduction to Ghosts and Marvels. Edited by Vere H. Collins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. v–xiii. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes. 1929. Some Remarks on Ghost Stories. The Bookman, December. 169–72. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes. 1931. The Collected Ghost Stories of M.R. James. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes. 2017. Four Ghost Stories. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague Rhodes, and Allen Beville Ramsay, eds. 1929. The Letters of H.E. Luxmoore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Darryl, and M. R. James, eds. 2011. The Collected Ghost Stories. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Chris. 2018. Fossil Poetry: Anglo-Saxon and Linguistic Nativism in Nineteenth-Century Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karkov, Catherine E. 2011. The Art of Anglo-Saxon England. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, Colin. 2002. Race, Theology and Revival: Scots Philology and Its Contexts in the Age of Pinkerton and Jamieson. Scottish Studies Review 3: 20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Klinck, Anne L. 1992. The Old English Elegies. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krapp, George Philip, and Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie, eds. 1936. The Exeter Book, The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records: A Collective Edition. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, Anthony. 2012. Fright Nights: The Horror of M.R. James. The New Yorker 13: 105–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lees, Clare E., and Gillian R. Overing. 2019. The Contemporary Medieval in Practice. London: University College London Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leo, Heinrich. 1857. Quae de se ipso Cynevulfus, Sive Cenevulfus, Sive Coenevulfus Poeta Anglosaxonicus Tradiderit. Halle: F. Hendeliis. [Google Scholar]

- Lerer, Seth. 2001. The Anglo-Saxon Pindar: Old English Scholarship and Augustan Criticism in Georges Hickes’s Thesaurus. Modern Philology 99: 26–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, Roy Francis. 1961. Three Old English Elegies. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, Robert. 2015. The Eeriness of the English Countryside. The Guardian, April 10. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, David. 2006. What Was Medievalism? Medieval Studies, Medievalism, and Cultural Studies. In Medieval Cultural Studies: Essays in Honour of Stephen Knight. Edited by Ruth Evans, Helen Fulton and David Matthews. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- McCorristine, Shane. 2007. Academia, Avocation, and Ludicity in the Supernatural Fiction of M.R. James. Limina: A Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies 13: 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, Henry. 1888. English Writers: An Attempt Towards a History of English Literature. Volume 2: From Cædmon to the Conquest. London: Cassell and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, Lisa, and Leslie S. Klinger, eds. 2019. Ghost Stories: Classic Tales of Horror and Suspense. New York: Pegasus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Ludvig. 1835. Collectanea Anglo-Saxonica Maximam Partem nunc Primum Edita et Vocabulario Illustrata. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Patrick J. 2017. Medieval Studies and the Ghost Stories of M.R. James. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Marie. 1978. The Paradox of Silent Speech in the Exeter Book Riddles. Neophilologus 62: 609–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, Jennifer. 2019. A Modest Proposal: Titles for the Exeter Book Riddles. Medium Ævum 88: 116–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, John D. 1997. A Beowulf Handbook. Edited by Niles and Robert E. Bjork. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, John D. 2006. Old English Enigmatic Poems and the Play of the Texts. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, John D. 2015. The Idea of Anglo-Saxon England 1066–1901: Remembering, Forgetting, Deciphering, and Renewing the Past. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, John D. 2016. Old English Literature: A Guide to Criticism with Selected Readings. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, John D. 2019. God’s Exiles and English Verse: On the Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, John D., and Allen J. Frantzen, eds. 1997. Anglo-Saxonism and the Construction of Social Identity. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- O’Camb, Brian. 2018. George Hickes and the Invention of the Old English Maxims Poems. English Literary History 85: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, Keith M. C. 2016. ‘You Know Where I Am If You Want Me’: Authorial Control and Ontological Ambiguity in the Ghost Stories of M. R. James. Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 15: 44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, S. Beth Newman. 2021. Crossed Lines: Reading a Riddle between Exeter Book Riddle 60 and ‘The Husband’s Message. Philological Quarterly 100: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Orchard, Andy. 2021. A Commentary on the Old English and Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Padelford, Frederick Morgan. 1899. Old English Musical Terms. Bonn: P. Hanstein. [Google Scholar]

- Page, Raymond Ian. 1973. An Introduction to English Runes. London: Methuen & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Paver, Michelle. 2010. Dark Matter: A Ghost Story. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, James. 2017. Nonhuman Voices in Anglo-Saxon Literature and Material Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, James. 2020. Mind, Mood, and Meteorology in Þrymful Þeow (R.1–3). In Riddles at Work in the Early Medieval Tradition: Words, Ideas, Interactions. Edited by Cavell Megan and Jennifer Neville. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Sarah. 2017. They Flee From Me That Sometime Did Me Seek. In Eight Ghosts: The English Heritage Book of New Ghost Stories. Edited by Rowan Routh. Tewkesbury: September Publishing, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff, Richard William. 1980. Montague Rhodes James. London: Scolar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pincombe, Mike. 2007. Homosexual Panic and the English Ghost Story: M.R. James and Others. In Warnings to the Curious: A Sheaf of Criticism on M R. James. Edited by Sunand Tryambak Joshi and Rosemary Pardoe. New York: Hippocampus Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey, Peter. 2013. Writing Speaks: Oral Poetics and Writing Technology in the Exeter Book Riddles. Philological Quarterly 92: 335–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rateliff, John D. 2007. The History of the Hobbit. Part I. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Nic. 2020. ‘Jack the Ripper’ link to famous ghost story revealed. BBC News, October 4. [Google Scholar]

- Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. 2015. Isidorean Perceptions of Order: The Exeter Book Riddles and Medieval Latin Enigmata. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, Ursula. 1991. Hearing from Books: The Rise of Fictionality in Old English Poetry. In Vox Intexta: Orality and Textuality in the Middle Ages. Edited by Alger N. Doane and Carol Braun Pasternack. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 117–36. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Jacqueline. 1997. “The Rules of Folklore” in the Ghost Stories of M. R. James. Folklore 108: 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Alexander, ed. 1879. The Complete Works of Robert Burns. London: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Soper, Harriet. 2017. Reading the Exeter Book Riddles as Life-Writing. Review of English Studies 68: 841–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sullivan, Jack. 1978. Elegant Nightmares: The English Ghost Story from LeFanu to Blackwood. Athens: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Terry W. 2021. ‘From the North’: M. R. James’s ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’. ANQ, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, Benjaminand, ed. and trans. 1842. Codex Exoniensis: A Collection of Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Published for the Society of Antiquaries of London by William Pickering. [Google Scholar]

- Thrupp, John. 1862. The Anglo-Saxon Home: A History of the Domestic Institutions and Customs of England. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany, Daniel. 2001. Lyric Substance: On Riddles, Materialism, and Poetic Obscurity. Critical Inquiry 28: 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilghman, Benjamin C. 2014. On the Enigmatic Nature of Things in Anglo-Saxon Art. Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 4: 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Craig. 1977. The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Workman, Leslie J. 1987. Editorial. Studies in Medievalism III: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Thomas. 1842. Biographia Britannica Literaria. London: John W. Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, Alfred John, ed. 1912. Old English Riddles. Boston: D.C. Heath. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murphy, P.J. Old English Enigmatic Poems and Their Reception in Early Scholarship and Supernatural Fiction. Humanities 2022, 11, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11020034

Murphy PJ. Old English Enigmatic Poems and Their Reception in Early Scholarship and Supernatural Fiction. Humanities. 2022; 11(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurphy, Patrick Joseph. 2022. "Old English Enigmatic Poems and Their Reception in Early Scholarship and Supernatural Fiction" Humanities 11, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11020034

APA StyleMurphy, P. J. (2022). Old English Enigmatic Poems and Their Reception in Early Scholarship and Supernatural Fiction. Humanities, 11(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/h11020034