1. Introduction

Palestinians have shown firm resistance to the Israeli occupation since 1948 and have been unified in their legitimate struggle for liberation. However, after 2006 Palestinians have suffered from divisive internal geopolitical rifts involving the two leading political parties—Fatah and Hamas. This has exacerbated tensions for Palestinians already living under occupation and suffering the impacts of the Israeli Separation Wall that has divided Palestine since 2002. The division within the internal Palestinian politics can be traced back to the general election following the death of Yasser Arafat, the previous Chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), and President of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) from 1994 to 2004. In 2006, Palestinians in West Bank and Gaza Strip headed to the polling stations to vote for the Palestinian Legislation Assembly and to choose a successor president for Arafat. The elections resulted in victory for Hamas representatives who won the election with 44% of the votes, ending an era of Fatah dominance (

Zanotti 2010, p. 44).

Hamas’s victory led to armed clashes between the two factions after a failed attempt to create a unity government. Since 2007, the Palestinian leadership has been divided, with Hamas governing the Gaza Strip and the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority governing the West Bank. This political rift has persisted for the next fifteen years, causing more problems for Palestinians seeking liberation from the Israeli occupation. The two parties have continuous “costly and stifling disputes, while the Palestinians and Palestine continue to bleed under the Israeli occupation” (

Matar and Harb 2013, p. 127).

1A nostalgia has been felt among Palestinians yearning for the days of Arafat’s leadership, who maintained less divisive policies than the current President Mahmoud Abbas. The yearning for a unified resistant Palestine that can continue its liberation project has been reflected in national poetry, traditional dance, songs, and dramas. Dramatic works like Eyad Abu Shareea’s

Al-Habl Al-Sori (

The Umbilical Cord) in 2010, Ali Abu Yassin’s

Al-Qafas (

The Cage) in 2015, and Ashraf Al-Afifi’s

Sabe’a Ard (

Seven Grounds Under) in 2017 appeared after 2007 to preach unity and sumud (steadfastness) against occupation (See

Abusultan 2021). The Palestinian theatre always plays “an active part in the border project of Palestinian national liberation by contesting Zionist discourse” (

Varghese 2020, p. 2) and often “remains politically contextualized within a framework of resistance, resilience, and self-development” (

Jawad 2013, p. 156). It portrays “the hardships of occupation, to remind us of the lost homeland, and to champion a political solution and the creation of an independent state” (

Nassar 2006, p. 16). Keeping that in mind, the Palestinian dramas produced after 2006 in the West Bank and Gaza Strip also focused on the political split between Fatah and Hamas as on addressing the Israeli occupation. Dramas like

Al-Habl Al-Sori, premiered at Rashad Shawa Cultural Center on 7 March 2010, was “an escape valve for what people say in secret, their frustration about the division and their anger over the foreign aid that interferes with [political] decisions” (Cited in

Abusultan 2021, pp. 39–40).

Seven Grounds Under is another biting comedy produced by the Culture and Free Thought Association in Gaza Strip in 2017, which reflects the concerns of youth in the Gaza Strip living under the Israeli and Egyptian blockades, and criticises the empty promises of Palestinian leaders (

Abusultan 2021, p. 47). These dramas and many others preached solidarity in post-Arafat Palestine and called for an end to the internal conflict that distracted Palestinians from their main struggle.

Kamel El-Basha’s

Following the Footsteps of Hamlet represents the same concerns for unification through an adaptation of Shakespeare’s

Hamlet. What distinguishes El-Basha’s performance is the employment of the chorus playing Hamlet and Ophelia instead of the traditional individual characters. The chorus dress similarly, walk and talk collectively to dramatise and materialise solidarity among Palestinians. Another distinctive theatrical device is the ghost that uniquely maintains a permanent presence on the stage. The presence of the ghost with its huge size, (see the description below), targets the memory of the audience and compels them to remember the days of Arafat.

2The Arabic-language production premiered at the Al-Hakawati National Theatre in Jerusalem, and last for one hour and a half. It is based on Jabra’s Arabic translation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and maintains the same plot as the original play with few theatrical modifications. The staging is minimal, with few sets or props used on the stage. A black curtain is used as a backdrop to the playing area, and black was also evident in the characters’ dress which consisted of long black robes with red scarfs, or kufiya, draped around the actors’ shoulders.

2. The Chorus and Unification

One of the theatrical devices used by EL-Basha in his performance is the employment of two choruses who played the roles of Hamlet and Ophelia instead of individual actors. Hamlet’s chorus consists of eight actors who in most of the time speak Hamlet’s dialogue and monologue collectively (See

Figure 1). Six actors shape the other chorus playing Ophelia; while, individual actors play the main characters of the King and Queen (See

Figure 2). Polonius and Laertes are acted by individuals from Hamlet’s chorus.

The two choruses sometimes merge and shape a band of fourteen actors dressed in black, sing, dance, move, and speak identically. The performance starts with the two choruses entering the stage as one band walking in a military march accompanied by martial music. They walk the width of the stage back and forth in synchronous steps for a few minutes (

El-Basha 2013, 1:00–3:00). After that, the band splits into groups of threes and twos. They sing in a collective voice a well-known religious song, called “Yarasoul Allah” (Oh prophet of God). The song is followed by the recitation of verses from the Holy Quran by an individual actor to arrange for King Hamlet’s funeral. The chorus then shifts to celebrate the marriage of Claudius and Gertrude through performing random dabke movements acted respectively by individual male actors.

3 The dance is accompanied by Zagareed, an ululation usually performed by Palestinian women, which is a high pitched vocal sound made with the quick movement of the tongue up and down in the mouth (

Sturman 2019, p. 120).

Claudius then addresses Hamlet’s chorus directly asking them, “How is it that the clouds still hang on you?” and the chorus replies collectively: “Not so, my lord. I am too much i’ the sun” (

El-Basha 2013, 11:12).

4 Gertrude also demands that Hamlet stop wearing the black clothes and behave in a friendly manner, “Good Hamlet, cast thy nighted colour off, And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark,” and the chorus sarcastically answers, “I shall in all my best obey you, madam” (

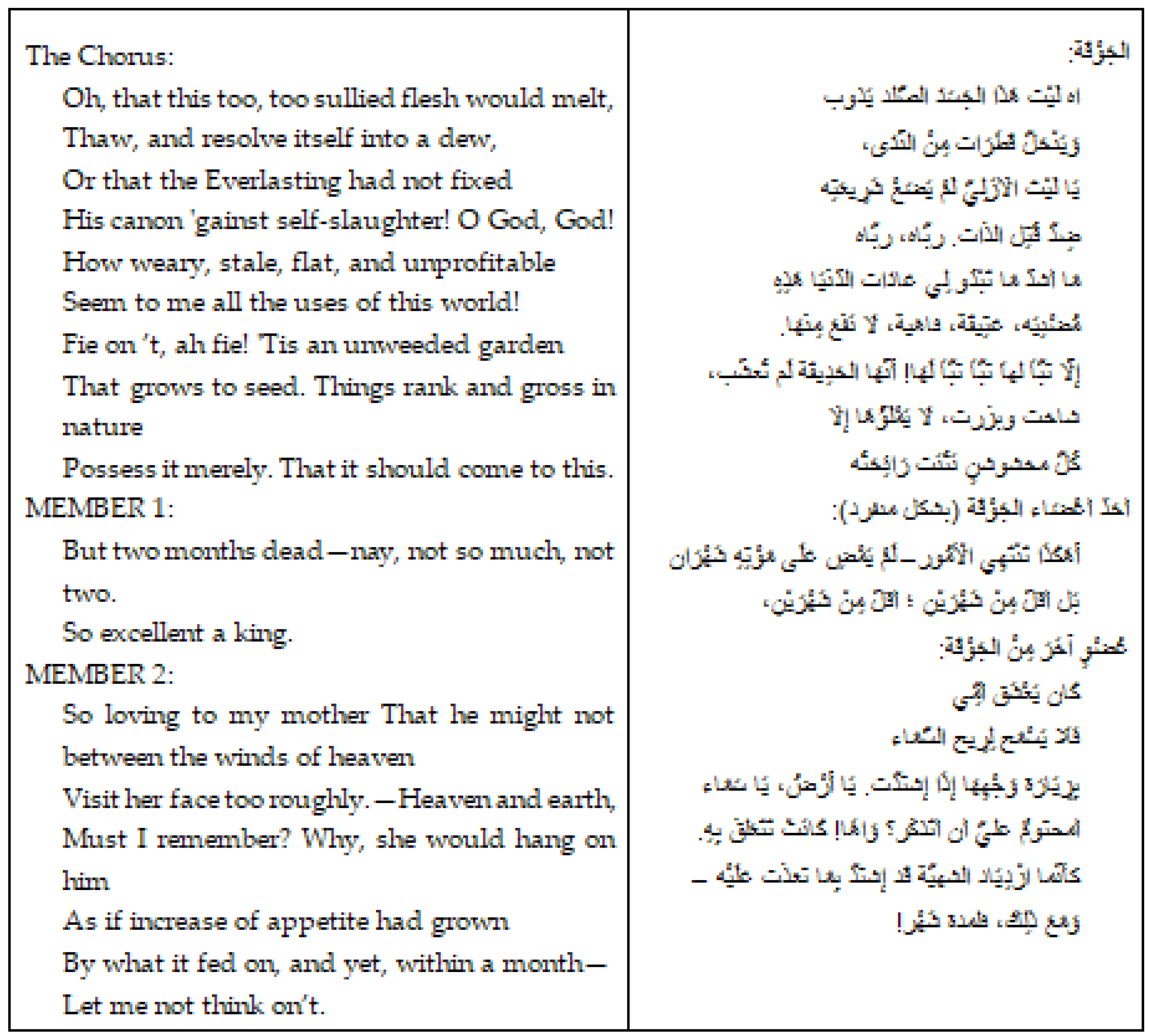

El-Basha 2013, 11:17). Claudius and Gertrude then leave, and the two choruses of Hamlet and Ophelia start roaming the stage impatiently as one group. They sit and begin beating the ground with their hands. They make a circle after that and repeat Hamlet’s famous monologue “this too, too sullied flesh would melt,” as they are mourning the death of King Hamlet and lament the hasty marriage of the Queen (See

Figure 3).

Hamlet’s chorus meets the ghost in the next scene, which informs them about the murder. The chorus then performs a short Mousetrap to verify Claudius’s murder. Hamlet’s chorus then enters the stage trying to take revenge by killing Claudius, but they find Claudius praying. They storm into Gertrude’s chamber immediately to confront her. They surround her, trying to remind her how she has offended his dead father by marrying Claudius. Polonius, who hides behind the arras, shouts and calls out for help leading the chorus to stab him to death.

Laertes, acted by one of Hamlet’s chorus, appears and discovers his father’s death, and Claudius convinces Laertes of taking revenge. Meanwhile, Ophelia’s chorus appears singing a sad song as if she has suffered madness due to her father’s death. The six female actors acted a collective death on the stage, and Gertrude laments Ophelia’s death by singing a sad traditional song, sang usually for Palestinian martyrs who died in their fighting for the occupation.

5 After that, Hamlet’s chorus splits into two groups: four members represent Laertes fighting the other four which represent Hamlet, and Kufiyas are used in the combat instead of swords.

6 Gertrude drinks the poisoned goblet of wine toasting Hamlet and she eventually dies. The stage becomes covered with fifteen bodies: several Hamlets, Laertes, Ophelias and a Gertrude. The performance ends with the bodies rising from death to follow the ghost which leads them slowly outside the stage. They collectively sing another familiar Arabic Muwashshah song on their way out, leaving Claudius alone and alive on the stage.

7EL-Basha’s employment of the chorus is perplexing for the spectators at the beginning, especially those who are not familiar with the aspects of choric theatre. The confusion appears early when it becomes difficult for them to identify individual actors for Hamlet and Ophelia and to understand why Ophelia’s chorus accompanies Hamlet in his speech sometimes. Jamal Al-Qwasmy accentuates this perplexity in his review for the play saying, “The young men were all representing Hamlet, and the young women representing Ophelia, but I did not understand why some young women would cast Hamlet especially when he confronts his mother and accuses her of adultery and tells her not to go to his uncle’s bed” (

Al-Qwasmy 2010). Another difficulty is caused by the excessive and quick movements of the chorus on the stage, which potentially distracts spectators from focusing on the speeches. Despite that, the spectators are quickly engaged in the show and the majority respond positively to the character’s dance and singing (See

El-Basha 2013, 4:32 &13:42). The chorus’s collective movements also help tune the spectator’s bodies as the latter follow the movements with their eyes from one point to the other on the stage. One can sense a mutual energy circulating in the space between the actors and the spectators alike: the actors act, and the spectators immediately react. This harmony felt in the space would not have happened without the employment of the chorus.

The appearance of the chorus on the stage always signifies the nation’s desire for fusion, especially when political rifts dominate the scene and hinder resistance exactly like the political atmosphere in post-2006 Palestine. Edith Hall comments on the role of the chorus, arguing that they “represent the we. Their oneness was expressed theatrically: visually, through matching costumes and masks, and also with collective dance movements; and audibly, through the choral singing of odes” (Cited in

Evans 2019, p. 140). Hans-Thies Lehmann also asserts that “the chorus offers the possibility of manifesting a collective body that assumes a relationship to social phantasms and desires of fusion” (

Lehmann 2009, p. 130). On the applicable side, the significance of the Choric Theatre in preaching unity is manifested in the German Einar Schleef’s

The Mothers (1986). He created a catwalk stage on which three female choruses walk, run, deliver their speech, interlude, and surround the spectators from a different direction (See

Fischer-Lichte 2017, pp. 315–27). Schleef’s theatre is inspired by his dream of a unified Germany, and the chorus reflects how the theatre “strove for total incorporation of all its members and threatened those who insisted on their individuality with marginalization and alienation” (

Fischer-Lichte 2017, p. 317). Still, the first critic to pay attention to the importance of the chorus as a theatrical unification device was probably Nietzsche in his seminal book

The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Nietzsche imagined the role of the chorus away from its traditional role as ideal spectators who create aesthetic distance and prevent the spectator’s identification with the characters. Instead, the dithyrambic Chorus Satyrs, as Nietzsche believed, is essential in the Greek dramas, and it celebrates the God Dionysius and reminded the Athenians of their sociality in comparison to Apollo, the god of rationalism and individuality. Nietzsche says:

In truth, however, this hero is the suffering Dionysus of the mysteries, that god experiencing in himself the agonies of individuation, the god of whom marvellous myths speak, telling the story of how he as a boy was dismembered by the Titans and is now worshipped in that state as Zagreus:* which suggests that this dismemberment, the properly Dionysian suffering, is similar to a transformation into earth, wind, fire, and water,· and that we should regard the state of individuation as the source and original cause of suffering, as something objectionable in itself.

In the same way that social bonds are established between the spectators that Nietzsche identifies, the chorus in EL-Basha’s performance dress similarly and talk in a collective voice for most of the time. This works to help materialise a unity among Palestinian audiences coming from different cities inside and outside the Israeli Wall, holding different ideologies (Muslims, Christians, Jews, conservatives, or liberals), and having different political affiliations (Hamas, Fateh, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the Palestinian National Initiative, or other independent political association). This unity is seen also in engaging the audience in the show by addressing him/her directly sometimes, and by asking the individual spectator to engage in the singing. However, video recording of the performance shows that a few individuals liked to remain disengaged in the show, but this engagement/disengagement dichotomy does not prevent the show from achieving its unifying goal. El-Basha is aware of this dichotomy and allows individual performances from time to time in his show. This is seen when individual members of the chorus speak some lines individually and when they perform the dance movements individually too. Still, the general outcome is that a harmonious community is felt in the space and the barriers between the individuals are broken. This temporal community, sensed in the one-hour-and-half show and created by the harmonious movements of the chorus, is what matters most. The performance becomes like a social game and a festival played and celebrated by all for all.

The chorus does not only run and speak collectively to achieve this unity, but it also performs some traditional songs and dances significant to solidify that feeling. The American hip hop dance performed regularly by individual actors on the stage and witnessed by the other members of the chorus and the spectators alike manifest resistance and compel audiences to reflect on the danger that political conflict causes. The traditional songs and the hip hop dances are also mixed with dabke—a traditional folk-dance that has always been part of the Palestinian struggle for liberation. David A. McDonald describes the connection between Palestinian identity and performing dabke in historical Palestine and the diaspora, suggesting that to preserve the dabke is to preserve the nation:

In the face of Israeli encroachment and the erasure of Palestinian space, time, and presence, the preservation of indigenous practices such as the dabke forcefully resists dispossession. Folklore is resistance. Detached from its ‘precious soil’, Palestinian identity, history, and nation must be kept alive, carried, preserved, and performed fact.

Other traditional rituals acted on the stage are the funeral ritual performed at the beginning for king Hamlet, accompanied by Quranic verses that the individual player recites while the chorus and the spectators are listening. After the funeral, the female chorus of Ophelia performed some ceremonial practices like ululation to celebrate happy occasions like the wedding of Claudius and Gertrude in the play. What is typical between these sad or happy rituals is that they are similarly performed in different Palestinian cities inside and outside the Wall and they help in strengthening social affinity among Palestinians. It is not only in Palestine that performing rituals and ceremonies seek unity, but all the colonised and marginalised nations have their performative rituals as part of their struggle to achieve liberation. Barbara Ehrenreich asserts how Westerners used to perceive such performative rituals by the colonised nations in Africa as “ecstatic ritual, noisy, crude, impious, and, simply, dissolute” (

Ehrenreich 2007, p. 3). This does not deny the fact that some Europeans have known and practiced some performative rituals, but the general inclination, especially with nineteenth-century European idealism, was to celebrate individuation more than community. After the 1930s, Western anthropologists began to see these “bizarre seeming activities of native people as mechanisms for achieving cohesiveness, generating a sense of unity and became a way of renewing the bonds that held a community together” (

Ehrenreich 2007, p. 10). In his book

Theatre, Society and Nation: Staging American Identities (2008), S.E. Wilmer also gives an example of the Indigenous Lakota Tribe performing ‘Ghost Dances’ to accentuate their identity against the white cultural hegemony and the genocide and confiscation of their lands by the white Americans. For almost two weeks, they perform dances by which they aspire to connect themselves with the ghosts of their predecessors, revive their values, reconfigure their nation, resist assimilations and assert separate Indian identity (

Wilmer 2008, p. 8). All that appears in El-Basha’s theatre is utilised to show Palestinian identity and preaches solidarity. The chorus, the dance, and the wearing of the kufiya, all reflect this. For Palestinians, the kufiya is “an allegory for national unity” and “a badge of national identity and activism” (

O’Brien and Rosberry 1991, pp. 170–71). The sound of happy ululation produced by women reflects their joy significant to heal the wounds and reflect their unbroken determination in facing the occupation. Indeed, the ululations have a political connection as embedded in popular culture: “The manifestations of joy, songs, and ululations were always associated with the culture of the Palestinian Revolution” (

A Purse, A Song 2021).

3. The Ghost and Memory

Another theatrical device used by El-Basha for preaching unity and sumud in divided Palestine is the ghost. The ghost is permanently present on the stage, dominating the playing area with its nine feet tall size. Often the character occupies much of the space and sometimes blocks the way of other characters, forcing them to go around it. It is dressed in a dark robe that covers its body from the head to foot, and the face is covered with a white mask presenting an anguished face and reminiscent of the kind of masks used in Japanese Noh theatre (See

Figure 4). Inside the moving statue, the actor AbdulSalam Abduh performed and voiced the lines (

Following the Footsteps of Hamlet 2009). What additionally can be noticed is its constant movement that can be described as slow and monotonous. It keeps watching and observing the characters and listening to their speech all the time. Still, Hamlet’s chorus can see the ghost twice in the play: in Act I, where the chorus suddenly comes across the spirit that reveals to them the secret of Claudius’s murder, and in Gertrude’s room, where the ghost orders them not to harm her. The spectators, in contrast, can see the ghost all the time on the stage with its huge size and continuous movement.

The disruptive dramatisation of the ghost has a theatrical significance, and it targets the audience’s conscience and memory. Its scary shape discomforts the audience and compels them to remember the time when they were unified under Arafat’s governance and who unified Palestinians against occupation and always avoided any clashes with other parties. It is also important to mention that Arafat’s quick illness and mysterious death in his centre in Ramallah in 2004 were highly shocking for the Palestinians. Many suspicions have been raised about Arafat’s unnatural death and the quick burying of his body, and many assumed the assassination of Arafat by poison. The accusations were directed at the Israeli government and at some of the Palestinian fellows surrounding him (

Saleh et al. 2014, pp. 13–16). However, the Palestinians demanded an immediate international investigation to discover the identity of the real murderer, but there was intentional procrastination to the investigation. It was not until 2012 that some Swiss experts from the Swiss University of Lausanne confirmed in a conference that Arafat’s corpse contains enough amount of plutonium enough to kill a person, but this very late dissection of the corpse would not prove the crime or decide who the real murderer is (

Clarke 2018, p. 28).

The similarities between the death of King Hamlet and Arafat by poison are incited by EL-Basha to present the spirit in an innovative way. The first time that Hamlet’s chorus encounters the ghost is when it reveals the secret of the murder to them. The spirit clarifies that it is Old Hamlet’s ghost who has ascended from purgatory to tell his son about the murder Claudius committed (See

Figure 5).

Most of Hamlet’s dialogue is spoken collectively, and some lines are spoken individually by individual members. The Arabic translated dialogue is very consistent with Shakespeare’s text with few modifications, for example when the ghost repeats “Remember me!” three times in the production. The groups respond that they will never forget the ghost’s commands. In Gertrude’s room, the chorus thought that the ghost came to chide his commands again when they say: “Have you come to scold your tardy son for straying from his mission, letting your important command slip by? Tell me!” (

El-Basha 2013, 46:00). But the ghost tells the chorus to be kinder to Gertrude, who is convinced that her son suffers madness after his father’s death. The chorus asks Gertrude to look carefully and see the ghost, “Look, look how it’s sneaking away”, but she replies that she cannot see anything: “No, nothing but ourselves” (

El-Basha 2013, 46:24).

It is perhaps true that El-Basha’s dramatisation of the ghost perplexes the audience at the beginning and distracts them from following the actions. Still, the important thing is that it quickly achieves its goal by evoking their anxiety and making them eager to look at the past and connect the ghost to Palestinian national figures like Arafat. The ghost, in a different manner, asks the chorus to remember it three times. It is not only searching for revenge, but it also demands remembrance. This remembrance shapes the presence of the ghost haunting the stages all the time. Emily Pine traced how the appearance of the ghosts on Irish stages, for example, usually connects Irish people with their past time and national figures. According to Pine:

Ghosts are unwanted haunting presences, yet they also testify to a fascination—even obsession—with the past. Ghosts thus embody the tension between forgetting and remembering that runs through Irish remembrance culture.

In

Hamlet and Purgatory (2013), Stephen Greenblatt also emphasises that the ghost “not only cries out for vengeance but his parting injunction, the solemn command upon which young Hamlet dwells obsessively, is that he remembers” (p. 206).

Greenblatt (

1992) believes that the ghost’s appearance is accompanied by horror and intensity of feeling to make its memory dig deep in Hamlet’s mind and make him willing “to wipe away [all] saws of books, all forms, all pressures past” from his mind (

Hamlet, Act I, Scene v, Line 99–100). It is important for the ghost to be disruptive for his son’s mind to make him always remember his uncle’s sin. Similarly, El-Basha’s huge and fearful ghost becomes very disruptive for the audiences to compel them to remember the old days when they were unified under Arafat’s rule.

EL-Basha’s performance is commensurate with the fundamental function of the theatre as a memory machine. According to Peter Holland, “If the theatre were a verb, it would be to remember” (

Holland 2006, p. 207). Also, “Theatre is … a function of remembrance. Where memory is, theatre is” (Cited in

Carlson 2001, p. vii). Its powerful effect ensued when it “plays on the nostalgic, on a version of memory, idealising the past as a way of looking at the present” (

Kershaw and Nicholson 2013, p. 24). For this sake of remembrance, playwrights like EL-Basha, always implement images, stories, characters, verbatim, and ghosts relating to historical figures and past incidents that evoke the collective memory of a particular nation.

8 Moreover, if the chorus sees the play-within-the-play as a way to capture Claudius’s conscience and makes him confess his crime, El-Basha’s complete performance is targeting the spectators’ memory and making them think carefully about the danger of maintaining internal political rifts that kept them busy from fighting the occupation. If Claudius is responsible for running Denmark to whom the Mousetrap should be addressed, then El-Basha’s play is addressed to some of the Palestinians who participated in running Palestine when many of them supported the conflict between Fatah and Hamas and tolerated the division for fifteen years. This is the significance of the ghost with its enormous size and unusual presence on the stage. It intends to disrupt them, make them uncomfortable, and compel them to remember their unity.

After the collective death of Hamlet’s chorus due to the poison, preceded also by the death of the Ophelias after committing suicide, and which the audience can see on the stage this time, all the spirits of the characters including Gertrude follow the ghost outside the stage walking slowly and singing. Claudius is left alone regretting his destructive policies before he dies. In a direct speech to the audience, he confesses his remorse (See

Figure 6)

El-Basha ends his play tragically with the collective death of the characters to deliver a message to the audience. He wants to fuel their fear of the catastrophic future Palestinians will face if they sustain the division nourished by the Fatah/Hamas political struggle to rule Palestine.