1. Dilemmas of Representing Refugees

“Representation is a complex business,” observed the British–Jamaican cultural theorist Stuart Hall, especially when dealing with “people and places which are significantly different from us” (

Hall 1997a, pp. 225–26). This is so because “difference” is a contested area of representation that constitutes a key site of the ongoing negotiation between the competing social and political forces through which power is defended, contested, and shifted. In addition, representations of difference, especially visual representations, engage emotions and attitudes. They may trigger the viewer’s anxieties and desire, as well as mobilizing cultural stereotypes that reinforce already existing prejudice and conventions. Representations are important, therefore, not only because of what they

are, but also because of what they

do, i.e., for their discursive and cultural functions and effects.

Drawing on Foucault’s discursive approach, Hall stresses that the subject is produced within discourse and can thus become “the bearer of the kind of knowledge which discourse produces […and] the object through which power is relayed” (

Hall 1997b, p. 55). In discourse, a subject has two sides, or “sites.” As a representational practice, discourse produces

subjects as identifiable figures—the national citizen, the foreigner, the refugee, etc. In doing so, discourse also constructs

subject-positions for the reader or viewer from which to make sense of its particular knowledge and representations (

Hall 1997b, p. 56). Hall’s point about the dual role of the subject in practices of representation is fundamental to any engagement with representational practices pivoting on “difference,” especially when they have a stake in the construction of a binary opposition between “us” and “them,” self and other, as is the case with the representation of refugees.

To begin with, it should be stressed that the focal point of this article is not the uprooting and flight from home, nor the forced displacement of refugees. As Emma Cox has noted, “an emphasis on

transiting bodies risks distilling refugee subjectivity to beleaguered mobility” (

Cox 2017, p. 495). This study shifts the perspective to the open-ended processes of “regrounding” (

Ahmed et al. 2003) and “worldmaking” (

Meskimmon 2017,

2011) which refugees undergo in the receiving country, and it links the representation of such processes to the broader debate about belonging and citizenship in Europe. Despite their mundane character and embeddedness in inconspicuous everyday life, the processes of settlement and belonging are inseparable from political discourses and the tightened policies on asylum and integration that have been implemented in connection with the resurgence of nationalism and the fortification of national borders in many Western countries. “Refugees and representation” is thus a profoundly politicized topic that brings societal conflicts to the fore, as also when experiences of refugeedom and questions of asylum are addressed within the spheres of art and literature, which are still widely believed to possess some degree of freedom and distance from society, despite the fact that the rich tradition of political art developing since the 1960s and 1970s has effectively refuted the modernist idea of radical autonomy and separateness.

Given the politicized nature of the topic, a study of artistic and curatorial modes of representing refugees should include a consideration of the entanglement of aesthetics with politics and ethics. Instead of choosing the traditional route and turning to Jacques Rancière’s theorization of the relationship between aesthetics and politics, thereby following in the footsteps of the numerous scholars and other professionals in the art field who have embraced Rancière’s theory in recent decades, I would like to pursue new avenues.

1 The ethical dilemmas and conflicting aims and perceptions involved in representing refugees are many, as suggested by the opening sentence of Hannah Arendt’s 1943 essay “We, Refugees”: “In the first place, we don’t like to be called ‘refugees’” (

Arendt 2007, p. 264). The question of how to “represent” refugees (and other marginalized or vulnerable groups) leads to two kinds of ethical consideration. Firstly, there is the risk of conforming to pre-existing tropes and thereby unintentionally exacerbating stereotypes of suffering and victimization, or their compensatory antidote which over-emphasizes assimilation and “notions that refugees should be ‘just like us’” (

Blomfield and Lenette 2018, p. 325). Secondly, there is the issue of agency and empowerment: Should refugees be represented, or represent themselves in the receiving country?; Should they “have” agency, voice and visibility, or should they be “given” agency, voice and visibility by spokespersons and other mediators in order to increase their chance of being “heard” and “understood” by the authorities and citizens of the receiving country?; Should they be given full control over the means of representation and platforms of communication?; Or should “speaking” and “making visible” in public spheres be based on a collaboration between refugees and native citizens? If so, what can participatory practices accomplish, and what dilemmas and conflicts of domination and suppression do they involve?

This article will explore the problem of representing refugees by way of a case study of the art project 100% FOREIGN? (100% FREMMED?), initiated in 2016 by photographer and curator Maja Nydal Eriksen and Metropolis/Copenhagen International Theatre. The project 100% FOREIGN? is Denmark’s first major documentary collection of individual accounts of former refugees. It consists of 250 life stories and photographic portraits of individuals who were granted asylum in Denmark between 1956 and 2019. Thus, it can be said to form a collective portrait and multivocal narrative that inserts citizens of refugee backgrounds into the narrative of the nation, thereby expanding the idea of national identity and culture, or more specifically, “Danishness.” Additionally, at the time of its completion in 2019, it was distinguished as the most encompassing civic participation project undertaken in Denmark. 100% FOREIGN? was an extraordinary ramified, expansive and viral project that engaged inhabitants, cultural institutions, cultural producers and municipal officers in cities across most of the country.

As an interdisciplinary project, 100% FOREIGN? aimed to “give voice to” refugees, and it spanned several genres—interview-based narrative, photographic portrait, art in public space, and more. Thus, it allows us to think of participatory art as a privileged locus for the exploration of intersubjective relations and the question of how to “represent” citizens with refugee experience as well as the history and practice of asylum—the building of a future life in a foreign country.

In a study of arts-based methods in refugee research, Isobel Blomfield and Caroline Lenette have proposed that, through collaboration with people from refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds, artists can create representations that are more empowering. One way of achieving this is to produce “counter-narratives that provide a more holistic construction of refugees’ individual historical, gender, political and cultural circumstances” (

Blomfield and Lenette 2018, p. 325). However, there are many dilemmas and ambiguities involved in such an endeavour:

100% FOREIGN? will serve here as the analytical reference point for a discussion of some of these issues. The article’s basic methodological premise is that both the politics and ethics of representation must be addressed when engaging with representations of refugees; furthermore, such representations must be situated in their immediate contexts of production and reception for their politicized character and meaning to become comprehensible. Only by considering the socio-historical circumstances and political climate is it possible to understand what

100% FOREIGN? set out to do, and why and how the project sought to engender a new civic ethics from the perspective of the refugee.

To situate the project in its historical and regional European context, I will briefly consider recent Danish immigration and asylum policies, and argue that, similarly to its neighbouring countries, Denmark can be described as a “postmigrant society” (

Foroutan 2019a). My consideration of the

ethical aspects of

100% FOREIGN? draws on Arendt’s essay and what Andreea Deciu Ritivoi has described as Arendt’s attempt to articulate an “ethics of alterity” from the perspective of the refugee (

Ritivoi 2019), as well as the Vietnamese–American filmmaker and theorist Trinh T. Minh-ha’s concept of speaking nearby. When considering the

political aspects of the project, I turn to the feminist concept of transversal politics (

Yuval-Davis 1999;

Meskimmon 2020), which has a strong intersubjective and ethical component. The case study illuminates some of the difficulties involved in representing refugees in a participatory art project, especially the challenge of ensuring that there is scope for the participants’ agency to unfold, as well as the question of how to create narratives (

Blomfield and Lenette 2018, p. 235) that counter stereotypification and articulate claims for the democratic right to be treated as an equal—or, in other words, a civic ethics of a plural community, springing from the perspective of the refugee. It is hoped that by threading the theoretical discussion through an example, this article can contribute to a deeper understanding of how participatory art forms and their interpretive and collaborative practices can intervene in the field of representation, and what they can bring to the ethical politics of representing the refugee experience.

2. Politics, Ethics and Aesthetics

For the purposes of this case study, I define ethics broadly but with a special emphasis on what ethics are understood to be within the domains of artistic practices and aesthetics, understood here in the broad sense of “sensory embodied experience” and not as a branch of philosophy and art theory. I adopt Geoffrey Galt Harpham’s understanding of ethics as “the arena in which the claims of otherness—the moral law, the human other, cultural norms, the Good-in-itself, etc.—are articulated and negotiated” (

Harpham 1995, p. 394). As Harpham explains, ethics has two functions: to formulate an ethical critique of the norms that are constituted within a given ethical system, and to articulate and defend different norms. I would like to suggest that

100% FOREIGN? sought to fulfil both purposes. Another way of describing the project’s dual function is to see it as pursuing both political and ethical ends. This rephrasing indicates why it is relevant to turn to Hannah Arendt. As Ritivoi observes, Arendt’s “ethics of alterity” was connected to her ideal of a political community as an arena in which individuals are not seen as born with a fixed and unchanging identity, but defined by their actions, opinions, and shifting positionalities; a plural community in which figures of alterity are not pushed to assimilate into sameness, but where difference is embraced (

Ritivoi 2019, p. 105).

In recent decades, the discourses on ethics and literary practice have increasingly focused on questions about otherness and witnessing related to the practices and responsibilities of both authors and readers (

Newton 2019, p. ix). In the field of contemporary visual arts, however, the discourse on ethics has taken a different course.

Since the 1960s, an expansive definition has extended the significance of art beyond the singular, discrete object, which is the work of art, to encompass the human relationships engendered by its production and its reception, as well as its institutional and social framework. As a result, artistic production has become increasingly reflexive about its complex relation to society, and shifted towards a strengthening of the connections between the work of art and its social context, site(s) of reception, and its audiences. To strengthen the interaction of audiences with works of art, a host of participatory practices—ranging from “relational aesthetics,”

2 to “relational antagonism,”

3 to “artivism”

4—have been introduced by artists who more often than not engage with politicized social issues, such as inequality, marginalization, gender, racism, stigmatization, climate crisis, and more. The discourses on the so-called “social turn” and “participatory turn” in art are thus inseparable from questions about “aesthetics and politics”.

5 It is from within these dominant and entangled discourses that a contemporary discourse on “the ethics of aesthetics” has emerged and has sought to define the special qualities of the social field and the intersubjective relations that an artwork engenders, and of which it is also a part (

Beshty 2015, p. 18). In other words, the discourse on art and ethics is a discourse

within the discourses on art’s relationship to politics, participation, and social engagement, from which it is rarely singled out for separate theorization. A rare example is the artist and writer Walead Beshty’s attempt to define an “aesthetics of ethics” in his introduction to the anthology

Ethics, with its source texts from the 1970s to the early 2010s. Beshty characterizes art that turns to ethics as “an art that operates directly upon the world it is situated in” (

Beshty 2015, p. 19) and whose ethical dimension is “manifest in the aesthetic appearance of the work itself” and in the “conditions of reception” it creates for its audience in order to propose “a modification to the social contract, with the artwork acting as the signification of this modification” (

Beshty 2015, p. 20). Applied to the practices of representing refugees, this understanding would shift the attention from the work of art as a discrete object to the ethical relationship between the way in which an artwork depicts subjects as

identifiable figures and how it co-constructs

subject-positions (Hall) to make its figures and message readable for the recipient—or, to borrow a more accurate term from literary parlance, for the implied reader.

3. Denmark’s Immigration and Asylum Polities

To fully understand the implications of

100% FOREIGN? as an artistic, ethical, and political intervention into current public debates, it is necessary to draw the contours of Denmark’s asylum policies and the popular feeling with regard to immigration and the growing demographic diversity of the population. Immigration has not only divided public opinion, but has also turned demographic change into an existential question about the perception of self and other. What does it mean to be Danish? Additionally, what does it mean to be foreign?

6 What does it take to become “a member of society” socially, and what does it take to be recognized as a citizen in the legal sense of the word?

Since the considerably increased influx of refugees and migrants from the Middle East and Africa into Europe in 2015, the narrativization of arrival has placed refugees within “a condemnatory frame” which is legitimized by concerns about refugees being a threat to national safety rather than people in need of aid and shelter, and which is backed by “combative modes of political leadership” (

Cox 2017, p. 485). An important change in European asylum policy and law is the introduction of further restraints on the possibility of gaining the security of permanent residency and access to citizenship. In recent years, Danish governments have introduced some of the toughest requirements for naturalization in the world. The restrictions on citizenship also affect well-established groups in society, such as immigrants who have lived and worked in the country for most of their lives, as well as the descendants of immigrants. In 2021, a report from the Danish Institute for Human Rights criticized the fact that only 65% of the descendants of immigrants born and raised in the country had obtained Danish citizenship. The fact that the number of people granted citizenship has declined to its lowest point in 40 years has also raised concerns about the democratic problem that a growing section of the population does not have the right to vote (

Denmark 2021;

Andersen et al. 2021, pp. 48, 58–59, 32–35).

Furthermore, in 2019, a study from the three Nordic countries, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, showed that young adults in Denmark believed that the acquisition of citizenship had become too difficult, indicating that there is a widening gap between parliament and the views of its population, especially young people (

Erdal et al. 2019, pp. 29–31, 60, 228–29). Although most researchers have argued that there is no genuine political multiculturalism in Denmark, recent surveys suggest that Danish “monoculturalism” is waning (

Larsen 2016a;

Holtug 2013). In addition, both the philosopher Nils Holtug and the sociologist Christian Albreckt Larsen have suggested that Danes increasingly base their notion of national community on the idea of Denmark as a political entity rather than a cultural community (

Holtug 2016;

Larsen 2016b). Larsen has convincingly argued that the growing significance of diversity in Danish national self-perception results primarily from

generational effects, and can therefore be considered irreversible. Based on a comparison of two large surveys conducted in 2003 and 2013, Larsen concludes that the national self-perception of the population seems to be “moving slowly but surely towards multiculture” (

Larsen 2016a, p. 135. See also:

Petersen et al. 2019, p. 40).

Regarding asylum policies, in 2015, Denmark saw the introduction of a new tertiary protection status of “temporary protection” for those fleeing general violence and armed conflict. The year after, access to family reunification for those granted “temporary protection status” was removed during the first three years of residence unless special considerations applied. Following the surge in the number of primarily Syrian asylum seekers in the summer of 2015, Denmark also ran an anti-refugee advertising campaign in Arabic-language newspapers, warning refugees about the plight that asylum seekers and refugees will have to endure in Denmark. Professor of Migration and Refugee Law, Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen, has described these restrictive asylum policies as a consciously deployed form of “negative nation-branding”, intended to deter refugees from applying for asylum in Denmark (

Gammeltoft-Hansen 2017, pp. 99–124, 109; see also pp. 99, 105–6). In short, Denmark, which has historically prided itself as being a liberal advocate of the protection of refugees, has become increasingly reluctant to integrate even a comparatively small numbers of foreigners. Anxious to stem the tide of right-wing nationalistic backlash and win back voters from the anti-immigration populist party, the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti), both the conservative and the centre-left blocs in parliament have more or less appropriated the anti-immigration policy of the Danish People’s Party and supported the seemingly endless series of restrictions on asylum, immigration and citizenship (

Denmark 2021), thus testifying to how an “invasion complex” has permeated national politics (

Papastergiadis 2017, p. 13; see also

Papastergiadis 2012, pp. 36–40).

In 2019, the year that the project

100% FOREIGN? was completed, the flagrant dehumanization of refugees by Danish asylum policies became obvious when the social democratic government declared that some asylum seekers from Syria could be sent back to Damascus province, although no other country in the world had yet declared this region safe enough for people to return. This repatriation plan has been fiercely contested by left-wing politicians, humanitarian organisations, ordinary citizens, and, importantly, young Syrian refugees who see their whole existence destroyed, as well as by some members of the social democratic party. Even so, Danish politicians still find voter and parliamentary support for continuing their aggressive anti-asylum seeker policies (

Abend 2019). Thus, in February 2021, the social democratic government presented a legislative proposal to externalize asylum processing and refugee responsibilities away from Danish territory by establishing an extra-territorial detention centre for asylum seekers on the African continent—a model reminiscent of Australia’s offshore detention camps in Nauru and Papua New Guinea (

Lemberg-Pedersen et al. 2021, pp. 10, 46–48). As Lemberg-Petersen observed, “[t]he proposal aims at shutting down Danish authorities’ processing of asylum claims, and granting of stay for refugees, on Danish territory” (

Lemberg-Pedersen 2021, p. 7).

7 Although the proposal encountered predictable and severe criticism from numerous scholars, journalists, citizens, and organisations concerned about the protection of refugees and the violation of their human rights, a bill enabling the externalization of asylum was passed in the Danish parliament in June of 2021. This led the newspaper

Politiken to conclude in their editorial that Denmark had ended up as a “scare story” and “a caricature of the rich” (

Politiken 2021; see also:

Thobo-Carlsen 2021).

As noted by Holtug, immigration policies are closely linked to the policies that govern civil society at large. This is reflected in the scramble for votes and the fact that “there is a growing part of the political spectrum that sees a welfare state and a multicultural society as directly incompatible, or at least difficult to have side by side.” The broad political and voter support for such restrictive policies thus indicates that “Danes are quite polarized over immigration,” as Holtug puts it (Holtug, quoted in:

Abend 2019, n.p., see also:

Holtug 2013). The polarization over immigration is aggravated even further by the ways in which anti-racism and feminist identity politics are often framed in the media and public debates by hostile narratives on “political correctness” and “the culture of hurt”, and wrongly interpreted as attempts to introduce prohibitions and suppress freedom—especially the white majority’s freedom of speech—rather than as struggles for social justice and expressions of a changing demography (

Marker and Hendricks 2019, pp. 120–21, 148). As philosophers Silas L. Marker and Vincent F. Hendricks observe in their book on the Danish public debates, both narratives “are used by one side of the debate to frame the public as an

us, who are the sensible and rational ones who do not get offended or hurt by trivial matters, and a

them, who can be hurt by anything, has no sense of humor and cannot take a joke” (

Marker and Hendricks 2019, p. 163).

With immigrants and their descendants making up 14% of the population, a figure expected to rise to 20% by 2060, it could be stated that Denmark is already well on its way to becoming a multi-ethnic society (

Statistics Denmark 2020, p. 22). Using a term from the German debates on the role played by immigration in the development of plural democratic societies, Denmark can thus be characterized as a “postmigrant society,” which is detailed further below.

8 At this juncture, the point I wish to stress is that the ways in which Danish governments have dealt with the challenge of refugees and their protection have not only affected the people directly concerned. In the longer term, the historical move away from humanitarian commitments that were defined in the twentieth century will also change Danes’ perceptions of society and national identity—these have, in fact, already changed. In the words of Søren Jessen-Petersen, former Assistant UN High Commissioner for Refugees:

Today, the joy and pleasure I felt by being Danish in an international organization, has been replaced by shame and embarrassment when former colleagues and friends contact me after yet another critical article in a major international medium about constraints, restrictions and inhuman treatment of asylum seekers and refugees in Denmark.

9

4. 100% FOREIGN?—An Overview of the Project

The art project

100% FOREIGN? emerged from and grapples with the socio-political circumstances outlined above. At the same time, it also engaged with the world history of refugeedom since the end of World War II and the adoption of the United Nations’ Refugee Convention in 1951. It constituted a targeted attempt to expand the understanding of citizenship by inserting a wide range of personal stories and portraits of citizens with refugee backgrounds in the official narrative about Denmark, thereby adding a new chapter to Danish history (

Padovan-Özdemir 2020, p. 3).

It is important to emphasize that the aim was not to tell the stories of the wars and persecutions that forced people to flee, or about internment in detention camps and the other troubles refugees had to go through before being granted asylum in Denmark:

100% FOREIGN? aimed to involve citizens with a refugee background in a multi-voiced rethinking of national identity as a heterogeneous rather than an ethnically homogeneous category. Here, the refugee and migration perspective became a tool for bringing the country’s actual diversity to light. In other words, the project was not about the escape, the journey, and the arrival, but about the lifelong, open-ended identity formation that the process of building a life in a foreign country entails. As explained to the digital visitor on the project’s website, the aim was “to update the national romantic portrayal of Denmark and place the participants in the official image of Denmark.”

10 In addition, the project made an ambitious attempt to unite art, history, identity, inclusion, learning, and democratic participation in one project.

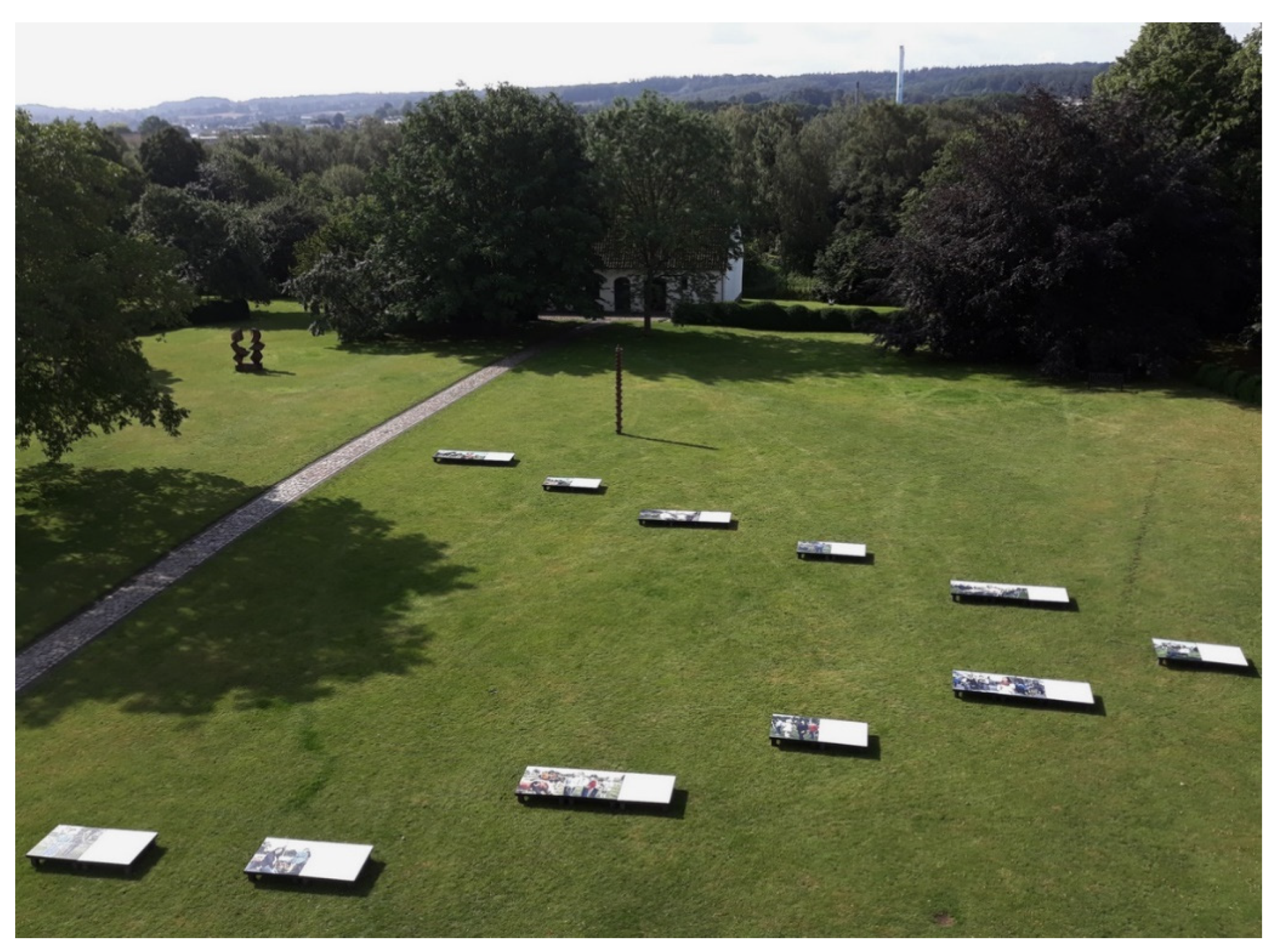

Maja Nydal Eriksen and Metropolis initiated the project in 2016. The first phase of the project resulted in a series of 100 portraits of and stories by former refugees living in Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. It was first shown at an exhibition in Copenhagen City Hall in the spring of 2017, and also included the performative event

Live stories (

Levende fortællinger), during which the audience could engage with some of the participants in a one-on-one conversation. This was followed later that same year by an open-air exhibition at a centrally located quayside in Copenhagen. In the next phase (2018–2019), the project was transformed into a travelling exhibition, which expanded the project’s geographical reach to include participants from cities across the country; the project was shown in public spaces and included newly added portraits of local residents (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

11 With each city, ten new portraits of local inhabitants were added. The exhibition was also accompanied by other events, such as theatre productions (with some of the participants as performers), community dinners, events at local libraries, and, importantly, educational activities for school classes. The latter, as a spinoff from the documentary project, was developed by Eriksen and the project group into an ambitious educational package launched in 2021, consisting of a website about dual cultural identity based on material and nine key themes from the exhibition, as well as classroom material and classes taught by former refugees.

5. A Postmigrant Society

Although the idea for

100% FOREIGN? arose from the debates about the European “refugee crisis” that dominated the media in 2015, the project’s focus on the Danish context must be understood from its origins in Maja Nydal Eriksen and Metropolis’s previous collaboration with the Berlin director and author group Rimini Protokoll on the staging of a Copenhagen version of their successful 100% City concept at the Royal Danish Theatre in 2013. This was a performance with 100 individuals selected based on statistical criteria, with each individual representing 1% of a city’s inhabitants, and the group collectively drawing a sociological portrait of the city. In this way, the 100% City concept created an interesting tension between individual and type, and between individual and society. Since the premiere of

100% Berlin: A Statistical Chain Reaction in 2008, which “showcased Berlin’s diverse population in an inclusive and cheerful atmosphere” (

Garde and Mumford 2016, p. 105), it has been developed into many productions, including

100% Melbourne (2012),

100% Gwangju (2014), and

100% São Paulo (2016). In the performance

100% Copenhagen (

100% København), the 100 citizens on stage were thus selected based on statistical criteria, as prescribed by Rimini Protokoll’s 100% City concept (

Eacho 2018, p. 185). Similar criteria were used to select the first 100 participants in

100% FOREIGN?12 The project aimed to include equal numbers of male and female participants, and in the photographs, Nydal Eriksen also played with the depiction of women in typical “masculine” postures, and vice versa. In the photographs, there are, for instance, more men shown lying down and more women playing an “active” or “leading” part. Moreover, many of the individual stories address questions of feminism and equality through narratives of social control, both positive and negative, and by seeking to unsettle gender stereotypes.

13 As a unique feature of the Copenhagen edition, the performance

100% Copenhagen was followed, in 2015, by an exhibition of staged portraits of the people behind the statistics, accompanied by their own suggestions on what sets them apart from the crowd. Here, Maja Nydal Eriksen assumed the dual role of artist and curator. This exhibition thus provided the model for

100% FOREIGN?,

14 with the portraits in both cases emphasizing the actual cultural and ethnic diversity of the capital.

It could be argued, however, that the meaning of the figure “100%” changed, because

100% FOREIGN? does not seek to map the demography of a whole city but, rather, suggests that alienation and belonging can be measured qualitatively on a scale from foreign to Danish. However, the question mark indicates that the proposition is deliberately provocative and should not be taken at face value. If anything, it implies that the binary opposition between “Danish” and “foreign” should be questioned. This is, in fact, what many of the participants did. Some refused to be measured according to this binary system. For instance, Sri Lankan-born Santha Selvam declared herself to be her very own “Santha mixture.”

15 Others used the percentage scale to criticize anti-immigration sentiment and policies, or to express their feeling of alienation and stigmatization, or conversely, their sense of belonging and inclusion. Overall, the percentage scale was used by the participants to communicate, in a succinct way, their personal experience of, and their position on, social inclusion and exclusion. Moreover, most of their stories implied knowledge of the fact that being Danish and foreign are co-existing parts of the participants’ identity and feelings of dual belonging. As such, the project is a multi-voiced articulation of a “postmigrant” sense of belonging.

This emphasis on complexity brings me to the idea of postmigration. In recent years, the term “postmigrant” (from the German

postmigrantisch) has been used about societies undergoing change as a result of immigration. It offers a framework of understanding within which one can examine art’s contributions to societies in the process of recognizing that they are moving towards increasing cultural and demographic diversity. This collective process of cognition and transformation is full of conflicts and entails a number of battles for recognition and equality alongside struggles over identity and culture. The postmigrant condition is thus characterized by political disagreement and clashes between, on the one hand, various forms of cultural pluralism, and on the other, various forms of nationalism, including anti-immigration and racist right-wing populism—clashes that have also brought

100% FOREIGN? into the firing line. When the exhibition’s portraits of mainly brown and black citizens were shown outdoors at Islands Brygge in Copenhagen over the summer of 2017, unknown perpetrators scrawled graffiti over all the exhibited portraits and threw half of the exhibition into the harbour—vandalism that not only embodied a gloomy reminder of the boatloads of refugees drowning at Europe’s borders, but also raised some concerns in the municipalities with which the project team subsequently collaborated. Would the exhibition be vandalized again? In that case, the show might risk producing bad publicity that would shift the focus to racism and hostility in the local area.

16 Several German researchers have used the idea of the “postmigrant society” strategically and politically to relaunch migration and socio-cultural diversity as a normal state of affairs, and thus as circumstances that affect all citizens regardless of origin, simply because they are embedded in everyday life—for example, when an ethnic Dane marries a foreigner, when classmates form friendships based on similarities and sympathies that cross ethnic boundaries, or when one has colleagues with dual citizenship. At the same time, postmigrant thinking remains critically attentive to the pervasiveness of anti-immigrant sentiment in European societies and political discourses. In her perceptive analysis of postmigrant democratic societies as societies in transformation that harbour a significant potential for social conflict, the German political scientist Naika Foroutan has convincingly argued that “migration” operates as “a twofold trigger” and “a symbolic battlefield for social self-description.” On the one hand, migration functions as “a metanarrative loaded with accusations of social conflict and insecurity, against which social antagonisms are constructed;” on the other, it serves as a vehicle for “identity formation that trades in the normality of diversity, hybridity and plurality as new markers of alliances and changing post-migrant peer group identities” (

Foroutan 2019b, p. 153).

It is in this light that one must understand Foroutan’s idea that Germany has become a postmigrant society, and that the acknowledgement of this change must lead to a renegotiation of established institutions, structures, and values (

Foroutan 2018, p. 185; see also

Foroutan 2019a,

2019b). The concept of a postmigrant society thus also harbours a normative, or perhaps even utopian, dimension: it is nurtured by the dream of change towards a more pluralistic and inclusive democratic society (

Schramm et al. 2019)—a postmigrant imaginary that also sustains

100% FOREIGN? Importantly, with regard to the participatory method underpinning the project, Foroutan has argued that connections through family, friends, school, political engagement, or the workplace have produced “new kinds of knowledge, empathy and attitudes” that construct “post-migrant alliances” of “heterogeneous peer groups” whose participants share moral and democratic ideals:

Immigrants and their descendants are not alone in their struggle for representation and participation. They have supporters for their cause who do not necessarily have a migration background, but share views on democracy and equality. […] Post-migrant alliances are a powerful tool to challenge structures of discrimination: they enable a shared fight against racist attitudes and the isolating othering of migrants, transcending socially constructed divisions and concepts.

From a postmigrant analytical perspective,

100% FOREIGN? can be seen as a response to the migration-related changes and debates of the twenty-first century, and as an attempt to put the postmigrant negotiations, ambivalence, and contradictions that surround national identity into perspective by raising questions about the refugee experience of belonging and alienation. Importantly, the exhibition catalogue with the 100 chronologically arranged portraits from Copenhagen reflects the contemporary political situation because it makes clear that the feeling of being a stranger and not belonging is most pronounced among the participants who have been granted asylum in recent years, not just because they have only had a few years to build a connection to Denmark, but also, as explained above, because asylum seekers have been surrounded by growing suspicion in the political and legal system and it has become more difficult to obtain a permanent residence permit and citizenship (

Petersen 2020, pp. 21–23;

Jensen et al. 2018).

6. Individual and Type

Thus endowed with a postmigrant perspective, we can take a closer look at some of the individual portraits and stories in 100% FOREIGN? The photographs suggest that Nydal Eriksen deliberately used the tension between individual and type in the original 100% City concept to challenge the viewer’s expectations. Overall, the portraits communicate that the project is not an advocacy of assimilation into a predefined, monocultural Danishness, but an attempt to put something else in place of the national romantic myth that unity presupposes sameness by demonstrating the actual diversity of the population. In the photographs, Nydal Eriksen has also consistently followed a contrapuntal principle that a slightly humorous, experimental, and often colourful visual staging of those portrayed should provide a contrast to their stories, which often give glimpses of adversity, alienation, ambivalence, and criticism. The text and the image thus form a tensional whole, where the image sometimes tells one thing about the person and the text something else. That tension is deliberately constructed through the curation of the participants’ voices and appearances, and it helps to nurture the audience’s questioning interest about the individual’s character, precisely because one cannot make image and text validate one another in any straightforward way.

Let us take two examples from the first part of the project, where all the participants were photographed in Tivoli, one of the oldest amusement parks in the world, and which is located directly opposite Copenhagen City Hall. Tivoli is popular among Copenhageners and tourists because its environment combines contemporary forms of entertainment with a nostalgic mix of exotic historical styles appropriated from other cultures, something that has been the visual hallmark of the park since its inauguration in 1843.

At the photographer’s request, the participants chose the clothes in which they would like to be depicted, and brought an object or person(s) with whom they wanted to be photographed. A cross-sectional gaze quickly identifies variations in how participants and photographer use attire and props to express identifications and affiliations. In some cases, a “type” or stereotypical figure is implied, in the sense that the portrait of the individual rubs up against common notions of particular ethnicities and nationalities. For example, if anyone might have expected to encounter a primitivist stereotype in the portrait of Congolese-born Julien Kalimira Mzee Murhul, they will be surprised to meet a highly educated man who signals, with his tie and attaché briefcase, an affiliation with the business sphere (

Figure 3). However, there is something else in the picture that provides resistance to stereotypification and puts the viewer to work: Murhul’s right arm is clad in armour, the meaning of which is open. It could be interpreted as a sign that Murhul is a man who has something to fight for—or against—but other interpretations are also possible. Behind him is a white mansion-like architectural model, which could carry thoughts in the direction of the White House in Washington, or Marienborg, the official residence of the Danish Prime Minister, and thus towards the centre of political power and parliamentary influence from which the surrounding fence seems to exclude Murhul. Tivoli’s Concert Hall can be glimpsed in the distant background. Unlike the amusement park’s original concert hall, which was built in a flamboyant Moorish style and crowned by onion domes, the current building from the 1950s is a piece of de-exoticized modern modular architecture that discreetly supports Murhul’s photographer-assisted self-representation.

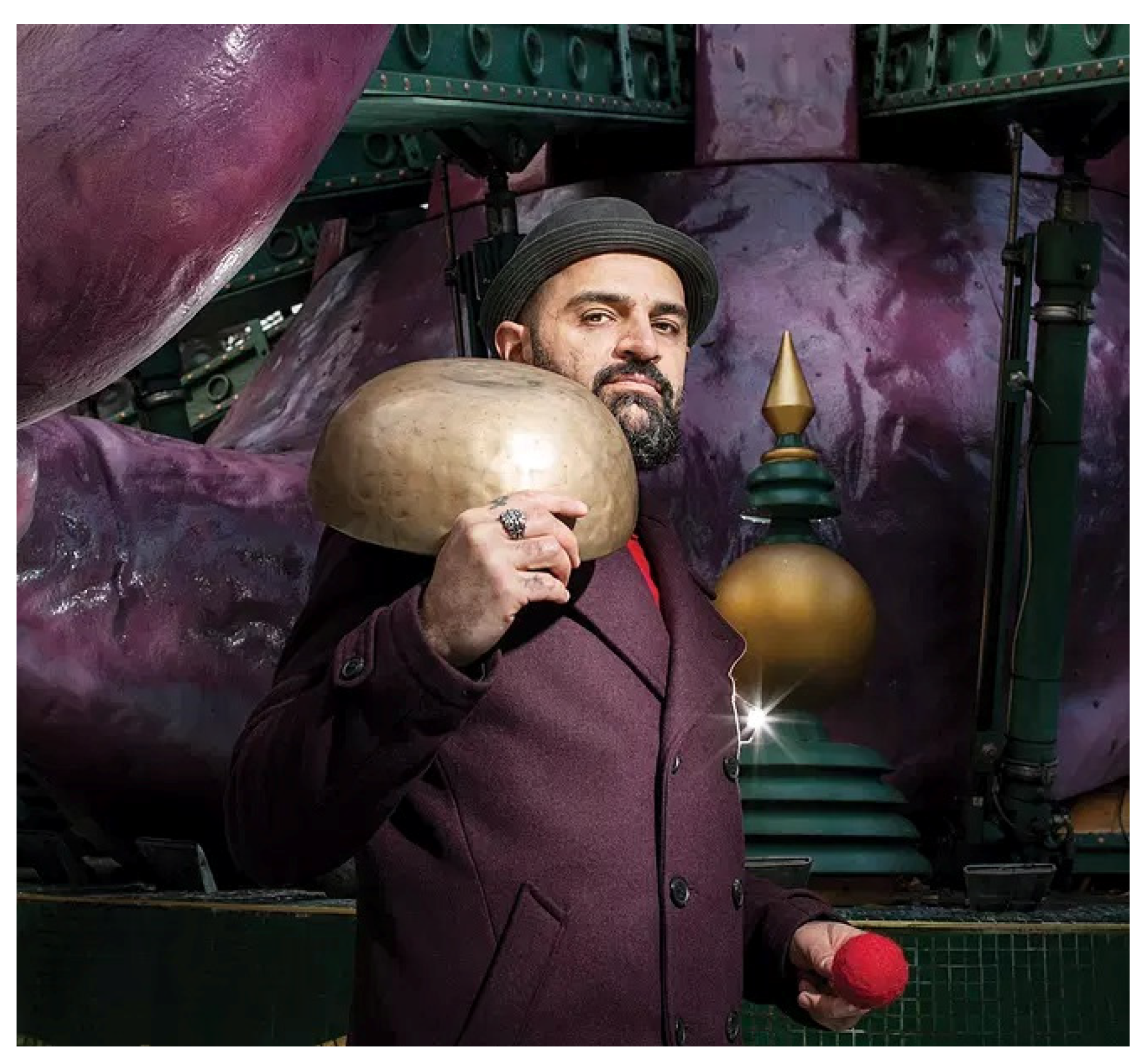

Conversely, the portrait of Iraqi-born Nawras Al-Hashimi overtly plays with the exotic (

Figure 4). His aubergine-coloured winter coat almost blends into the deep burgundy semi-darkness of the background, from which an enigmatic construction in green and gold emerges, as if from Aladdin’s cave, conjuring up fantasies of oriental palaces and mystics. However, the figure of Al-Hashimi pulls the flying carpet of imagination from under the feet of any spectators who might think that they can recognize an “oriental type” in his portrait. Not only does Al-Hashimi look back at the viewer with a piercing gaze, but when reading his story, viewers will discover that he is a childhood educator and lives in “a spiritual collective, where, through meditation and therapy, we heal and support one another to help us find and accept ourselves as we are, freed from culturally based layers of identity such as gender and ethnicity” (Al-Hashimi in:

Jensen et al. 2018, n.p.). Thus, confronted with their own stereotypical expectations, the viewers’ migrantizing perception of Al-Hashimi as an “outsider inside” (

Ahmed 2000, p. 3) is nudged towards the realization that the source of mysticism in the picture should not be sought in the Middle East, but in the Western spirituality movements that have long since become an ingrained part of Danish culture.

7. A Human Exhibition?

Several portraits play with the notion of the exotic; therefore, some people are likely to read

100% FOREIGN? as an exoticizing project. For example, Marta Padovan-Özdemir, who researches integration, discrimination, and pedagogy, has argued that it is a “migrantological human exhibition” because the portraits from Tivoli recall a problematic aspect of Tivoli’s history. Between 1878 and 1909, there were fifty “human” exhibitions in Denmark that displayed “exotic” human beings from distant cultures. These exhibitions travelled to major European cities. When reaching Copenhagen, they were often hosted by Tivoli, or alternatively, Copenhagen Zoo, where huge crowds of curious Danes visited exhibitions such as “China in Tivoli” (1902) and “South India in Tivoli” (1903). These displays of ethnographic stereotypes stimulated both scholarly anthropological interest and a popular desire for entertainment and the spectacularly exotic (

Bak 2020, n.p.). In addition, these exhibitions did not just passively reflect the fact that racial hierarchies and prejudice permeated European mentality of that time; they actively contributed to disseminating the theories of race and European civilizational superiority that were used to legitimize colonial exploitation abroad. Considering Tivoli’s past, Padovan-Özdemir’s comparison of

100% FOREIGN? to the historical human exhibitions is thus not surprising, but it does come across as somewhat superficial, because it is based solely on the observation that persons of foreign descent have been portrayed in Tivoli, and the fact that racial prejudice and fantasies of white supremacy still persist. Such a reading brackets all the historical differences, and the “postmigrant” message they communicate that is key to this project.

To begin with, a straightforward comparison with the earlier human exhibitions neglects the fact that in the early twenty-first century, the audience for exhibitions in public urban spaces is inherently diverse. Padovan-Özdemir, for example, assumes that the audience of

100% FOREIGN? is similar to the crowds of white Danes who visited the human exhibitions around 1900. This leads her to conclude that the reception of these representations of “refugees” is “pedagogically dependent on the imagination and the aesthetic and discursive register of the majoritized viewer” (

Padovan-Özdemir 2020, p. 55). Secondly, there were sexual and ethnographic aspects to the human exhibitions, because exotic peoples such as “Laplanders” (i.e., Sami), Nubians, Bedouins, Indians (India), and Japanese were displayed with sexual connotations. According to Rikke Andreassen, the leading Danish expert on the subject, “the women were often half naked and performed sexually provocative dances” (

Andreassen 2003, pp. 22, 25). Moreover, there was a connection between the exhibitions and the scientific disciplines of anthropology and ethnography, which explains why great attention was paid to the “authentic” ethnographic details of the exhibits and the way in which exotic people were displayed, not as individuals but as representatives of racialized groups according to the scientific paradigm of evolution that dominated the decades around 1900 (

Andreassen 2003, pp. 22, 26–28).

Thirdly, the peoples staged in the human exhibitions did not have any “voice,” either collectively or individually. Nor did they have any influence on how they were represented in the commercial and ethnographical images of the time—as opposed to the participants in

100% FOREIGN?, who were co-producers of both their portraits and their stories. Moreover, as an exhibition based on portraits of individuals,

100% FOREIGN? sought to create a kind of “contact zone” (

Pratt 1991) that could facilitate mediated face-to-face encounters between people living in Denmark. Conversely, the human exhibitions were mass spectacles of temporary “guests” performing their “authentic” daily life as allegedly unspoilt people of nature living with their animals in an exhibition environment designed to look untouched by Western civilization (

Andreassen 2003, pp. 23–27). In other words, the stereotyped tableaus of these exhibitions were designed to serve as mirror images of their “‘primitive’ villages,” thereby “preserving a European white world order” (

Andreassen 2003, p. 35):

The majority of Danes did not personally engage with the exhibited people; they remained distant observers. For them, as for Denmark as a whole, the exhibitions had a larger cultural function in creating a racial imagination of the nation.

In summary, an ahistorical comparison neglects how Nydal Eriksen’s artistic and curatorial approach differs from the human exhibitions, and how the subtle evocation of racial exhibition history is intended to highlight the differences: all the details of individualized backgrounds and the participatory strategy of portrayal testify to the fact that Danish society has become a plural postmigrant society. That only people of migrant backgrounds have been portrayed arguably makes the project migrantizing, although in a country that has not yet officially recognized that it has become a postmigrant society, such a systematic inclusion of “other” bodies, voices and stories—their coming into appearance in the public sphere—is a necessary first step that may help pave the way for a deeper understanding of what living under postmigrant conditions entails for all citizens.

Here, a note on how the word “foreign” is used in the title is in order. On the one hand, “foreign” designates someone who has arrived from an “outside” and is perceived as “an Other;” thus, it has an othering or a migrantizing effect. On the other hand, the question mark points to the inadequacy of the term and conveys that the dual aim of the project was to problematize the misconception that refugees do not transculturate and “belong,” and to acknowledge the persistent, albeit in many cases dwindling, feeling of alienation that refugees (and immigrants in general) must tackle, precisely because they are subjected to various forms of exclusion and migrantization. Arguably, representations of people that are already migrantized in the popular perception and public discourse will never be completely free of racial markers or hierarchies of power, but this should not overshadow that dignifying representations can work against marginalization and exclusion, and radically challenge the nationalist divide between “us” and “them.”

A comparison with another travelling exhibition can help us get a better grip of the ethical and political work

100% FOREIGN? aspired to do: Alfred Steichen’s 1955 exhibition

Family of Man, as interpreted by Ariella Azoulay, an expert on photography studies. Azoulay describes

Family of Man as “a landmark event in the history of photography and human rights” (

Azoulay 2013, p. 19). As with

100% FOREIGN?, its objects of display were photographs of people from across the world, and it was likewise historically related to the period after the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the United Nations in 1948. The purpose of Steichen’s exhibition was to demonstrate the universality of human actions in daily life and the human life cycle. Azoulay reads the images of the exhibition as an “archive containing the visual proxy of the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights” (

Azoulay 2013, p. 20). She notes that the exhibition cannot be ascribed to a single creator, i.e., the curator, but, similar to

100% FOREIGN?, bore “traces of an encounter of multiple participants” that included both subjects and viewers (

Azoulay 2013, p. 32). Importantly, Azoulay emphasizes the “multiplicity” of the photographic material that Steichen subsumed under categories such as “work” and “family,” and how its “heterogeneity” seemed to work against misconceptions of universality as an ideological regime of sameness and the eradication of difference. Its multiplicity suggested diversity in unity:

The identical format of black-and-white photographs showing humans in allegedly similar situations actually foregrounds to what extent the photographed persons differ from each other—their crafts vary, their gestures are multiple, and every expression or smile hints at a different experiential world that cannot be organized along generalizations of nation, gender, or race.

Paying close attention to the exhibition’s potential effects, i.e., what the exhibition

does, Azoulay proposes to read the photographs in

Family of Man not as “descriptive statements with universal claims”, but as “prescriptive statements claiming universal rights” (

Azoulay 2013, p. 20). Turning back to the portraits of the Danish project, I propose to read them not as documentary descriptions, but as prescriptive statements claiming democratic rights.

8. The Domestic Culture of Public Discourse

With its basis of co-creation and collaboration between citizens, interviewers, and artist/curator,

100% FOREIGN? can be linked to a broader current in contemporary art where artists, curators and other professional actors reach out to new user groups and audiences in participation-based projects.

17 More precisely,

100% FOREIGN? belongs to the growing number of such projects that have sought to find ways to “give voice to” minority groups and to improve their access to democratic participation in society. Although every single story in

100% FOREIGN? is based on a long interview, the conversations are systematically boiled down to short stories of a uniform length and with varying perspectives on the overall question of belonging and alienation that was posed to all the participants: “What percentage foreign do you feel?”

18 As Padovan-Özdemir has noted, the voice speaking can thus be described as a “curated voice” (

Padovan-Özdemir 2020, p. 50). She criticizes this artistic–curatorial approach for being a “pedagogically domesticating form of oppression” that “neglects structural suffering and offers the resolution of alienation” (

Padovan-Özdemir 2020, pp. 55–56), whereas I prefer to perceive the project as an ethical and political attempt to establish the kind of voice or enunciation that Trinh T. Minh-ha has called speaking nearby. Minh-ha defines speaking nearby as an alternative to the prevailing practice of speaking

about the Other, thereby making the Other an object that is “absent from the place spoken from.” She describes speaking nearby as an “indirect” way of speaking—for example, it could appropriately be added here, through the dialogic form of an interview. This mode of enunciation does not disempower those affected (deprives them of their voice and visibility), and it is predicated on the speaker’s/artist’s awareness of their own privileged position of utterance (

Chen 1992, p. 87). In

100% FOREIGN?, the privileged position is that of the white majority understood as a position of naturalized dominance and preference that eases access to airtime and to making oneself heard in a Danish public sphere, a positionality shared by this author.

As Nermin Duraković has explained, “the domestic culture of public discourse” is dominated by “a discourse in which ‘they’ (foreigners) are seen as objects rather than subjects” (

Duraković 2021, n.p.). Or, put differently, speaking nearby is something of a rarity. Duraković is in a better position than most to put his finger on the problem. As a child, Duraković came to Denmark from the then-civil-war-ravaged Yugoslavia. He has thus been part of “them,” the newcomers. At the same time, he is also a graduate of the Funen Art Academy, Denmark, and a recognized figure on the Danish art scene. He is thus undeniably part of “us.” Such ambiguous positions have tremendous difficulty in finding acceptance in Danish politics, public discourses, and mainstream national culture. People with a dual or multiple sense of belonging are rarely embraced, and it is into this ideologically and emotionally charged field that

100% FOREIGN? makes an intervention. As Duraković puts it, the public conversational culture treats “‘them’(strangers)” as:

anything but an included part of our common consciousness or as a common and equal voice that must be taken seriously and that can act and function with a critical potential. It tells us very directly that our society does not rest on equality, equal rights or equal access to critical expression, and that there is still a long way to go. The idea and the realization of equality require a more nuanced view of ourselves.

Although the delicate balance between listening and communication that the ideal of speaking nearby requires is hardly achieved in all 250 interviews, comments such as the following show that the participants in

100% FOREIGN? could articulate experiences with structural discrimination, suffering, and alienation. This not only must be presumed to separate them from the white Danish interviewers, but also leaves a question mark over the modern myth of Denmark as a country characterized by democratic equality and populated by friendly residents who welcome strangers as their equals with openness and tolerance: “I have found it very difficult to feel at home here because it’s been a constant struggle with the Danish Immigration Service,” says Samira Khalifa. Similarly, the aforementioned Julien Kalimira Mzee Murhul explains how changing governments have created a climate of inhospitality by using refugee policy for negative nation-branding to scare refugees from seeking asylum in Denmark as he voices his claim for democratic representation: “I feel foreign in Denmark, even more than 100%. When the government constantly tightens legislation on immigration instead of making legislation that will facilitate integration, it is hard to feel at home …. Us new Danes born south of the Sahara are not part of the Danish Parliament (Folketinget), and as a result we don’t feel like we are part of society either” (quoted from:

Jensen et al. 2018, n.p.). The experience that it is difficult to be recognized as a 100% citizen is shared by Cong Hung Nguyen, who describes the feeling of alienation in a way that is strikingly similar to the critical reader’s letters and posts that brown and black Danes increasingly publish in the daily press and on social media, especially since the Black Lives Matter protests against racism flared up in the early summer of 2020 after the police murder of the African–American George Floyd: “I have no ambition of returning to my home country like a lot of other foreigners talk about. I am 50% foreign, but only because everyone always asks me where I come from” (

Jensen et al. 2018, n.p.).

19 In summary, the participants took part in a project based on informed consent that was very much about claiming democratic rights, specifically, the rights of refugees. To that end, the project sought to provide a framework for self-representation in public—even though it is evident, particularly in the photographs, that it was an assisted and mediated form of self-representation, where the artist remained the ultimate curator of the project’s individual representations and its overarching narrative. An additional point is that the majority of those who have seen one of the exhibitions or read the catalogue, and the pupils who have explored some of the individual stories in school, have probably not applied a top-down or “vertical” birds-eye view. The curatorial design deliberately hampered attempts to survey the exhibition in its totality. Instead, it constructed a “horizontal” experience for viewers/readers, in which they moved around the exhibition, or browsed the catalogue or the website, and let themselves be captured by the stories and portraits that aroused their curiosity. It was exactly this conscious curatorial organization of intersubjective face-to-face meetings, i.e., encounters with one individual after another (rather than an encounter with a group or a mass), which opened up the project’s narratives and portraits to different interpretations, identifications, and counter-identifications by recipients whose position in relation to the depicted individual depended on similarities and differences in gender, class, ethnicity, age, experience, political conviction, hometown, country of origin, etc.

9. Hannah Arendt’s Ethics of Alterity

As a participatory project foregrounding both actual and imaginary intersubjective relations,

100% FOREIGN? offers a productive site for examining the ethical potential and dilemmas of representing refugees by speculating on what conflicts of domination and suppression the project involved, and how it may contribute new answers to vital questions on democratic participation, integration, belonging and citizenship. According to Ritivoi, Hannah Arendt “grounded ethics in aesthetics because she viewed aesthetic representation as a way of understanding how the world appears to different human beings. To let the imagination ‘go visiting’ another’s world, as she put it, was all the more important when it could recover marginalized and repressed perspectives” (

Ritivoi 2019, p. 103).

As a Jewish refugee from the Nazi persecution and genocide of European Jews, Arendt emigrated from Germany to France in 1933 and travelled via Portugal to the United States in 1941. Her essay “We Refugees” was first published in 1943 in the Jewish–American periodical

Menorah Journal, but its rhetorical construction suggests that it was addressed to a larger American audience as well, “the audience of citizens, rather than immigrants” (

Ritivoi 2019, p. 110). It would be fair to say that

100% FOREIGN? is also addressed to a larger audience, and notably one that includes both citizens and immigrants. Despite this difference, Arendt’s essay serves as a reminder of the pressure to assimilate imposed on refugees—a pressure that

100% FOREIGN? sought to counter by stressing how the navigation between different cultures has fostered a unique, composite character in each participant that does not conform to traditional notions of being Danish, born and bred. At the same time, the project explored the effects of this pressure by measuring the participant’s mixed feelings of belonging and unbelonging against “the official image of Denmark.”

20 Even if the project challenged the dominant image and proffered an alternative founded in an ethics of alterity, the curatorial framing nevertheless had to walk on a razor’s edge in order to steer clear of the subsumptive approach that overemphasizes resemblances and thereby subsumes minoritarian differences under a majoritarian umbrella of cultural commonality. Arendt can help us better understand this probably unsolvable ethical (and political) conundrum of representation.

The “we” of Arendt’s essay fuses her own fate as a Jewish refugee during World War II with a general analysis of the predicament of refugees forced to settle temporarily or permanently in whatever country will receive them.

21 She critically analyses the dual assimilative pressure put on refugees by the expectations of the receiving country and the efforts of the refugees themselves to blend in, as part of their process of building a new life and gaining recognition as a fellow citizen. Arendt describes, and not without humour, how Jews fleeing Nazi persecution rushed headlong to assimilate and become ordinary citizens of the host country (

Meyer 2016, p. 45). According to Arendt’s analysis, refugees are driven partly by the desire to rid themselves of the label “refugee” and to erase all the traces of refugeedom and a different heritage that may result in self-disclosure, and partly by the inducements and pressure of the host community: “We were told to forget; and we forgot quicker than anybody ever imagined. In a friendly way we were reminded that the new country would become a new home; and after four weeks in France or six weeks in America, we pretended to be Frenchmen or Americans” (

Arendt 2007, p. 265).

In the wartime United States, German refugees were perceived not only as “prospective citizens” but also as “enemy aliens” (

Arendt 2007, p. 266); therefore, they were anxious to not convey their refugee status:

we are already so damnably careful in every moment of our daily lives to avoid any-body guessing who we are, what kind of passport we have …. We try the best we can to fit into a world where you have to be sort of politically minded when you buy your food.

As an antidote to this assimilationist erasure of the refugees’ difference and past, Arendt proposes a new political self-consciousness of refugees who insist on the right to disclose their character, deviate from the norm, and not subject themselves to “the narrowness of caste spirit” (

Arendt 2007, p. 274). However, the public appearance of such performances of alterity would require a change in attitude in the host community. Drawing on Arendt’s ethics, Ritivoi suggests that “[t]o recognize and respect alterity requires us to understand another’s standpoint and see how it came about, as well as what beliefs and values it makes possible.” (

Ritivoi 2019, p. 104).

Seen in the light of Arendt’s ethics of alterity, 100% FOREIGN? presents itself as an ambiguous endeavour because it contributes to both assimilative and politically self-conscious processes of identity formation. Not surprisingly, the 250 individual stories and portraits reveal that the participants responded differently, some stressing their (partial) integration into and identification with Danish society, others their critical stance, their (partial) difference, and their ties to their country of birth. Recapitulating Hall’s point about the dual role of the subject in representation, this participatory project could be said to construct a vantage point or subject position for recipients, from which it was possible to glimpse the diversity of standpoints taken by migrantized citizens as identifiable figures who have to continually negotiate their identity and subjectivity, and who do so in very different ways.

Interestingly, Arendt used the metaphor of the blueprint to explain how aesthetic representation can serve as exemplary. Writing on Franz Kafka, she likened his stories to the blueprint’s representation of a model or plan, i.e., a tool that enables us to imagine what a future construction will look like. The metaphor of the blueprint captures the emergent nature of aesthetic representation, and also suggests that the audience needs “to realize by their own imagination” the intentions of its maker and the future it envisions (

Arendt 1994, pp. 76–77). The metaphor thus suggests that it is indeed the indeterminate character of

100% FOREIGN? that enables us to see in it the contours of a future plural society. In Ritivoi’s accurate wording, the blueprint “captures configurations in which we can discern both a world now around us and the world as it is most likely to take shape” (

Ritivoi 2019, p. 107).

10. Transforming the Image of Denmark

The participants from other cities portrayed in the second phase of

100% FOREIGN? were photographed in local cultural landscapes and thus inserted “in the official image of Denmark” in a both concrete and symbolic way. These portraits raise the question of whether this approach represents an “apparently consensus-seeking” update of the image of Denmark (

Padovan-Özdemir 2020, p. 48), or, as I would suggest, an intervention, rather, that reveals some of its cracks and changes? As my examples show, Nydal Eriksen was not content to merely state that citizens with a refugee background are also included in the Danish cultural landscape (

Padovan-Özdemir 2020, p. 51). The portraits and stories did not leave the official image of Denmark unchanged.

Fatima Yassin was photographed together with some of the other participants from the town of Sønderborg at Dybbøl Mill (

Figure 5). The image shows that they have come on Segways as tourists on a guided tour to one of the most important memorial landscapes in Danish history, Dybbøl Banke, the site of the war against the Germans in 1864 and a traumatic national defeat that nurtured an enduring fear of strangers from the south. Behind Fatima Yassin stands an elderly gentleman wearing a uniform jacket similar to those worn by Danish soldiers during the battle. However, his bicycle helmet suggests a different time and role—that of a Segway-riding tourist guide. The introductory text for the exhibition in Sønderborg described Dybbøl Banke as “a memorial landscape of war and peace for two nations and a symbol of Danish identity and community.” It also explained that the visit reawakened the participants’ “own experiences of war and unrest, the delineation of frontiers, as well as minority and majority issues.”

22The picture of Fatima Yassin and the others reveals nothing about how they each experienced their own history crossing tracks with Danish war history. It communicates a general message about the connection between past and future, anticipation and memory. The portrait plays on the contrast between the older man, a gatekeeper of Danish history, in the background, and the young woman in front who is eager to move on. Fatima Yassin stands still, like a statue, on her Segway, and even though the photograph freezes all movement, her figure nonetheless speaks of mobility and change. The bodies on wheels introduce today’s motorized mobility into the representation of a commemorative landscape, serving as a synecdoche for national history. At the same time, the female figure’s latent restlessness supports the interview’s narrative of a mother who came to Denmark from Syria in 2015 and who is now looking to a future where Danish culture has undergone some changes. As she observes: “My children must learn both cultures, but I think they will become 90% Danish” (

Eriksen et al. 2021, pp. 45–46). What the last 10% of the children’s cultural identity might include is suggested by Bosnian–Danish Amira Saric’s story: “I love the Nordic names, but since both my husband and I are of Bosnian origin, it would be too strange. I would feel as if I had stolen the child of someone else. My middle daughter is named Esma, and one of her girlfriends has got a rabbit that she calls Esma. That’s my secret plan. That it should not be abnormal to be named Esma in Denmark.”

23 This desire to make Denmark more culturally inclusive is akin in spirit to what I described above as a postmigrant mindset that will pave the way for an understanding of migration and socio-cultural diversity as a normal and integrated dynamic in society.

Turning to the portrait of Alia Ismail El-Aynein from Vejle (

Figure 6), it becomes clear that “the Danish cultural landscape” must be understood in an expanded sense, which also includes the digital landscape and the way politicians use social media, and specifically Facebook (

Eriksen et al. 2021, pp. 165–166). Most Danes will remember that, in 2017, a grinning Inger Støjberg posed with the crown jewel of the traditional Danish birthday celebration—the layer cake—to boast that she, as Minister of Immigration and Integration in Lars Lykke Rasmussen’s Liberal government at the time, had implemented fifty tightenings of the immigration laws. Danish media willingly helped spread the controversial image of the minister with the layer cake adorned with Danish flags over interconnected media platforms, so that the image and everything it said about Danish immigration policy became an indelible part of the memory of citizens across the country—a collective memory. Nydal Eriksen, together with Alia Ismail El-Aynein, has created a counter image to this piece of digital cultural heritage. El-Aynein, who runs a catering company in Viborg, presents a magnificent heart-shaped layer cake decorated with berries and flowers to the viewer. Behind her stands Amira Saric, who holds a plate of layer cake, and thus acts as an identification figure for the viewer, making it easy to imagine receiving a piece of the cake oneself. El-Aynein is photographed at the heritage site Kongernes Jelling (home of the Viking kings); more precisely, at the place where, in the Viking Age, two rows of stones formed the outline of the ship that, according to Norse mythology, sailed the dead to Valhalla. Today, the “ship” is marked by large slabs of concrete. As in Fatima Yassin’s portrait, there is thus a clear thematization of travel and mobility as being integral to the Danish cultural landscape. El-Aynein stands at the head of the “ship”, like a traveller ready to walk down the gangplank. Just as Dybbøl Banke is portrayed as a place where different war memories intersect, Jelling is interpreted as the place where religions meet, because in this image, the Old Norse faith crosses with Christianity and Islam.

Nydal Eriksen has photographed from an angle that causes the two rows of concrete tiles to encircle El-Aynein like a mandorla, i.e., the tapered oval halo that encloses the entire figure in medieval Christian images, as in images of the Virgin Mary. As an art historian raised on Western pictorial traditions, this is my first association. El-Aynein’s red scarf and red-edged cloak flutter in the wind; the folds in the cloth create a visual abstract and spiritual dynamic around the figure, as seen in Renaissance and Baroque religious paintings, such as Titian’s famous altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin in the Frari Church in Venice (1516–1518). However, my association is quickly followed by an observation: El-Aynein’s veil is a Muslim tradition. In the interview, she explains that the headscarf connects her with her roots in Lebanon, where she was born to Palestinian parents: “When I came to Denmark, I did not wear a headscarf, but I started to miss it. I do not quite know why: Maybe you are looking for your roots when you come to a new country?” (

Eriksen et al. 2021, p. 165). Drawing on the political and popular meaning of the cake, the history of the place, the religious symbols, and the visual composition, Nydal Eriksen, together with El-Aynein, has created a counter-image to Støjberg’s image, which exposes the inhospitality of Støjberg’s self-presentation and elevates El-Aynein to the true defender of the layer cake as a positive symbol of hospitality and heart-warming generosity. She is at once portrayed as the newcomer who comes ashore in an unknown country, and the hostess who invites us all inside for cake.

11. A Postmigrant Transversal Politics through Art: Concluding Remarks

In this article, I have threaded a theoretical discussion through a case study to provide an answer to the question of what participatory artistic practices of representation can bring to the ethical politics of representing refugees. To emphasize the challenges involved in representing alterity, the article opened with Stuart Hall’s observation that representation, especially the representation of “difference,” is a complex and contested matter that provokes strong emotions and conflicting sentiments. As a participatory project, 100% FOREIGN? took a collaborative approach to representation by “speaking nearby” (Minh-ha). It brought a transformation to the ethical politics of representing refugees: firstly, of the way in which subjects of refugee backgrounds are depicted as identifiable figures by ensuring that each participant was portrayed as a unique individual; and, secondly, of the way representations co-construct subject positions for the audience. The latter was achieved by way of a “horizontal” curatorial design that staged the visitor’s encounter with the portrayed as a one-on-one encounter.

With four selected portraits, I have tried to show how

100% FOREIGN? contributes to creating a richly differentiated and inclusive narrative about identity, belonging, and citizenship in Denmark. As I have argued above, this encompassing documentation of the experiences of those living in this country with a refugee background should not be read as mere documentary descriptions, but rather as prescriptive statements claiming democratic rights (

Foroutan 2019b, p. 158).

The ethics and politics that governed the collaboration on

100% FOREIGN?, as well as how the individual portraits and stories were curated to stimulate audience engagement, can be more accurately described through the feminist concept of transversal politics. A further reason for turning to feminist theory is the fact that Nydal Eriksen has consistently foregrounded a feminist notion of equality by including men and women in equal numbers, and, as previously explained, by consciously letting some women adopt a classical “masculine” pose, as seen, for instance, in the image of Fatima Yassin leading the Segway trip to Dybbøl Banke.

24To begin with, the term

transversal politics signals crucial links between political, ethical, and artistic agency. My use of the term is indebted to the feminist sociologist Nira Yuval-Davis’s understanding of transversal politics as a feminist intersectional and transnational theory and practice of democratic solidarity-building and conflict-resolution; and, especially, to art historian Marsha Meskimmon’s generative extension of Yuval-Davis’s concept to the sphere of art. Meskimmon has developed Yuval-Davis’s feminist intersectional approach to identity formation and solidarity-building into a theoretical sensibility, which not only facilitates an aggregated analysis of sameness and difference that complicates established assumptions about power and domination, but also examines how intersectionality can “create kin” and “affective coalitions” (

Meskimmon 2020, p. 8). The feminist conception of transversal politics can be traced back to the peacebuilding work of the feminist activist movement Women in Black in Bologna from the 1970s to the 1990s. They used the term “transversalism” about the method they used in their work with conflicting national groups—Serbs and Croats, Palestinian and Israeli Jewish women—to find a fair solution to the conflict. Crucially in the context of

100% FOREIGN?, the boundaries between the participants were not, as explained by Yuval-Davis, perceived simplistically as if they were merely representatives of their groupings. Their different positioning and background were “recognised and respected.” Using the key words of “rooting” and “shifting”, the Bologna feminists worked from the idea that each participant would bring with her “the rooting in her own membership and identity,” but would also try “to shift in order to put herself in a situation of exchange with women who have different membership and identity.” In other words, “[t]he transversal coming together should not be with the members of the other group ‘en bloc’ but with those who, in their different rooting, share compatible values and goals to one’s own” (

Yuval-Davis 1994, pp. 192–93; see also:

Yuval-Davis 1999). Thus defined, transversal politics can be seen as a practice of intersubjective exchange which is in agreement with Hannah Arendt’s idea of an ethics of alterity from the perspective of the refugee. Both are based on the conviction that to respect alterity, we need to recognize another’s standpoint and to understand how it came about, and what compatible values and beliefs it makes it possible to share.

The transversal politics of

100% FOREIGN? generated an affective coalition. The project brought together people of many different heritages and from all walks of life to collaborate on the production of portraits, stories, exhibitions, educational material, cultural events, and, importantly, solidarity, and what Foroutan has described as reshuffled peer groups or postmigrant alliances where people of different ethnic, national, and religious backgrounds come together because they share similar attitudes on equality and diversity as hallmarks of a plural democracy. Interestingly, with regard to the recipients’ engagement with the exhibition, Foroutan notes that postmigrant alliances are “also possible without contact or interaction” and that they can be forged on the basis of empathy and proximity, but also “be more than just empathetic; they can be political or strategic” (

Foroutan 2019b, p. 158).