The Academic Mobility of Students from Kazakhstan to Japan: Problems and Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Data Sources

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Internationalization of Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan

3.2. Kazakhstan‒Japan Political Relations

3.3. Cooperation in the Field of Higher Education between Kazakhstan and Japan

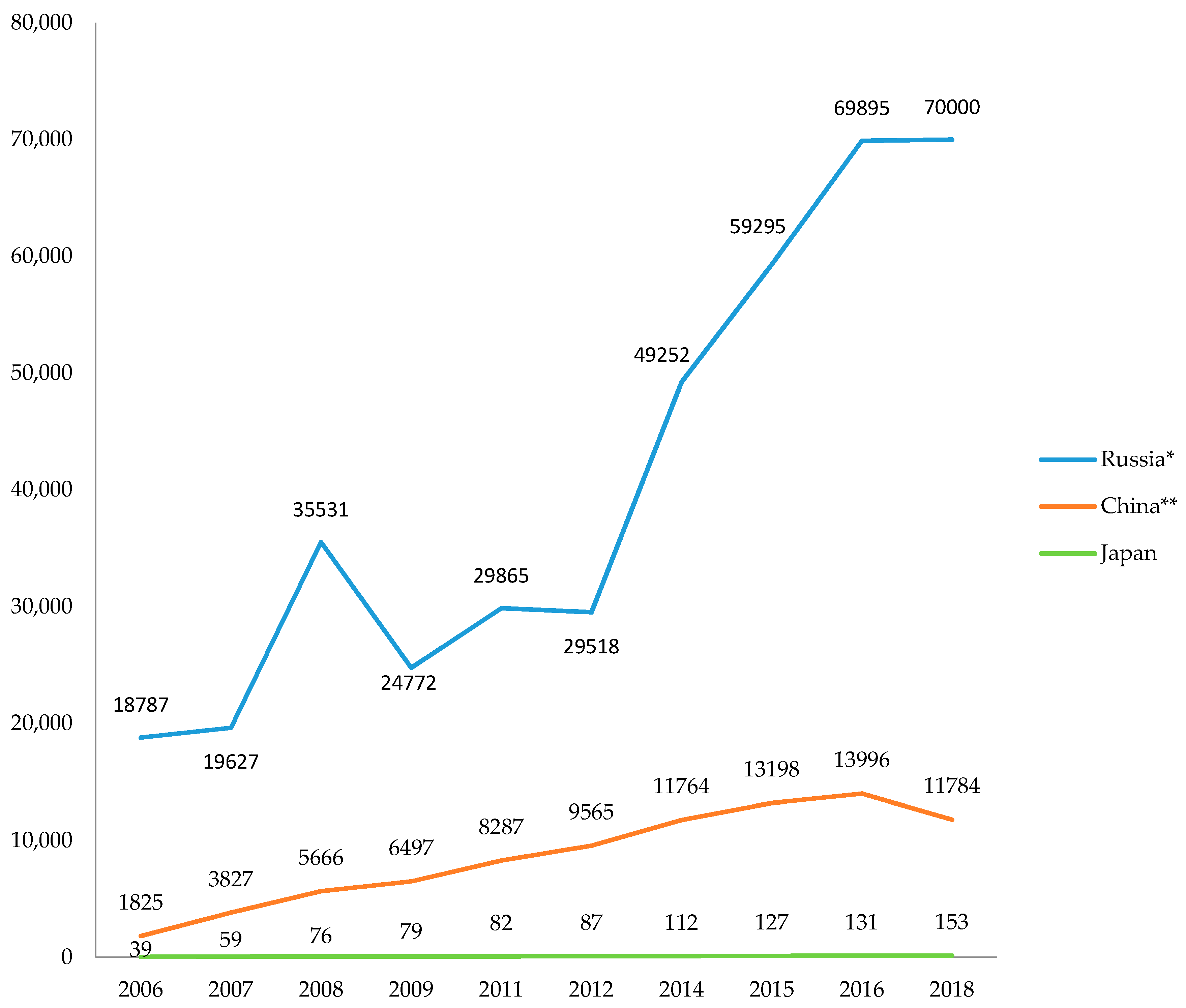

3.4. Student Mobility in the Field of Higher Education between Kazakhstan and Japan

3.5. Factors that Influence the Study Destination Choice of Students

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altbach, Philip G. 2007. Globalization and the University: Realities in an Unequal World. In International Handbook of Higher Education. Edited by James J. F. Forest and Philip G. Altbach. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 121–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, Philip G., Liz Reisberg, and Laura E. Rumbley. 2009. Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution: A Report Pprepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. Paris: UNESC. Available online: https://www.cep.edu.rs/public/Altbach,_Reisberg,_Rumbley_Tracking_an_Academic_Revolution,_UNESCO_2009.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Birmanov, Sultan. 2018. Kazakhstan Is on the Rise, Kazakhstanis Are in Recession. IA Inbusiness.Kz—This Is Financial, Economic, Political News, Analytics, Ratings, Conclusions and Forecasts, Exchange Rates and Markets for Securities, Precious Metals, Raw Materials and Non-Raw Materials, News From Banks, Exchanges, Companies, Also Do Not Go Unnoticed by Social Problems of the Regions. inbusiness.kz. Available online: https://inbusiness.kz/ru/news/kazahstan-na-podeme-kazahstancy-v-recessii (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Bodycott, Peter. 2009. Choosing a Higher Education Study Abroad Destination: What Mainland Chinese Parents and Students Rate as Important. Journal of Research in International Education 8: 349–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, Kleinsy, Sergio Salles-Filho, and Adriana Bin. 2018. Building Science, Technology, and Research Capacity in Developing Countries: Evidence from Student Mobility and International Cooperation between Korea and Guatemala. STI Policy Review 9: 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotherhood, Thomas, Christopher D. Hammond, and Yangson Kim. 2020. Towards an Actor-Centered Typology of Internationalization: A Study of Junior International Faculty in Japanese Universities. Higher Education 79: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, Chris, Ian Gibson, Jay Klaphake, and Mark Selzer. 2010. The ‘Global 30’ Project and Japanese Higher Education Reform: An Example of a ‘Closing in’ or an ‘Opening Up’? Globalisation, Societies and Education 8: 461–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Intelligence Agency. 2017. The World Factbook. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2119rank.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Chen, Liang-Hsuan. 2007. Choosing Canadian Graduate Schools from Afar: East Asian Students’ Perspectives. Higher Education 54: 759–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Education Online. 2014. Investigation Report on Studying in China in 2014. Chinese education online service content and fields cover all kinds of information services from pre-school to elementary and middle school, and university level. www.eol.cn. Available online: http://www.eol.cn/html/lhlx/content.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Collins, Neil, and Kristina Bekenova. 2017. Fuelling the New Great Game: Kazakhstan, Energy Policy and the EU. Asia Europe Journal 15: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubillo, Jose, Joaquín Sánchez, and Julio Cerviño. 2006. International Students’ Decision-Making Process. International Journal of Educational Management 20: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadabayev, Timur. 2016a. Japan’s ODA Assistance Scheme and Central Asian Engagement: Determinants, Trends, and Expectations. Japan in Central Asia, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadabayev, Timur. 2016b. Japan’s ODA Assistance Scheme and Central Asian Engagement: Determinants, Trends, Expectations. Journal of Eurasian Studies 7: 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadabayev, Timur. 2019. Central Asia: Japan’s New ‘Old’ Frontier. Asia Pacific Issues 136: 1–12. Available online: https://www.eastwestcenter.org/publications/central-asia-japans-new-old-frontier (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Dadabayev, Timur. 2008. Models of Cooperation in Central Asia and Japan’s Central Asian Engagements: Factors, Determinants and Trends. In Japan’s Silk Road Diplomacy: Paving the Road Ahead. Washington and Stockholm: CACI & SRSP, pp. 121–40. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268686263_2008_Models_of_Cooperation_in_Central_Asia_and_Japan’s_Central_Asian_Engagements_Factors_Determinants_and_Trends_in_Christopher_Len_Uyama_Tomohiko_Hirose_Tetsuya_eds_Japan’s_Silk_Road_Diplomacy_Paving (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Dawson, Marcelle C. 2020. Rehumanising the University for an Alternative Future: Decolonisation, Alternative Epistemologies and Cognitive Justice. Identities 27: 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, Aleksandr. 2015. 80% of Bolashak Graduates Work in Government Agencies, not in Business. forbes.kz. Available online: https://forbes.kz//stats/chemu_uchatsya_biznes-lideryi_1/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- De Wit, Hans. 2010. Internationalisation of Higher Education in Europe and Its Assessment, Trends and Issues|Observatory on Internationalization and Networks in Tertiary Education for Latin America and The Caribbean, 28. Nederlands-Vlaamse Accreditatieorganisatie. Available online: https://www.eurashe.eu/library/modernising-phe/mobility/internationalisation/WG4%20R%20Hans%20de%20Wit%20Internationalisation_of_Higher_Education_in_Europe_DEF_december_2010.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Dissyukov, Almas. 2019. ‘Central Asia Plus Japan’ Dialogue: From Idea to Implementation. Journal of International and Advanced Japanese Studies 11: 1–12. Available online: http://japan.tsukuba.ac.jp/research/JIAJS_PRINTED01_Dissyukov.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Döring, Nicola, Kamel Lahmar, M. Madani Bouabdallah, Mohamed Bouafia, Djamel Bouzid, G. Gobsch, and Erich Runge. 2010. German-Algerian University Exchange from the Perspective of Students and Teachers: Results of an Intercultural Survey. Journal of Studies in International Education 14: 240–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Preez, Petro. 2018. On Decolonisation and Internationalisation of University Curricula: What Can We Learn from Rosi Braidotti? Journal of Education 74: 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, Judith, Wayne W. Smith, and Robert E. Pitts. 2010. Exploring Factors Influencing Student Study Abroad Destination Choice. Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism 10: 232–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan in Japan. 2017. Economic Cooperation. Available online: https://www.gov.kz/memleket/entities/mfa-tokyo/activities/1993?lang=en (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- e-Stat Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan. 2019. Statistics of Foreign Residents (Formerly Statistics of Registered Foreign Residents) Statistics of Foreign Residents Monthly June 2019 | File. General Contact Point for Government Statistics. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00250012&tstat=000001018034&cycle=1&year=20190&month=12040606&tclass1=000001060399 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. 2018. The European Higher Education Area in 2018. Bologna Process Implementation Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinkina, Svetlana, Madina Turaeva, and Artem Yakovlev. 2016. Chinese post-Soviet Space Development Strategy and the Fate of the Eurasian Union. Moscow: Institute of Economics, RAS. Available online: http://www.inecon.org/docs/Glinkina_Turaeva_Yakovlev_paper_2016.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Griffin, Keith. 1999. Social Policy in Kazakstan during the Economic Transition. International Journal of Social Economics 26: 134–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guruz, Kemal. 2011. Higher Education and International Student Mobility in the Global Knowledge Economy. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, Kayoko. 2013. ‘English-Only’, but Not a Medium-of-Instruction Policy: The Japanese Way of Internationalising Education for Both Domestic and Overseas Students. Current Issues in Language Planning: Language Planning and Medium of Instruction in Asia 14: 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudzik, John K. 2011. Comprehensive Internationalization: From Concept to Action. Washington, DC: NAFSA. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b65a/cfa7193e15fedffa1fad671247cee4c6ead0.pdf?_ga=2.56583907.912882431.1594789264-59234853.1593067229 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Ilyassova-Schoenfeld, Aray Kozyevna. 2019. Development of the Credit System in Kazakhstan. International Higher Education 9: 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Steven, Gary Madden, and Michael Simpson. 1998. Emerging Australian Education Markets: A Discrete Choice Model of Taiwanese and Indonesian Student Intended Study Destination. Education Economics 6: 159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerimkulova, Sulushash, and Aliya Kuzhabekova. 2017. Quality Assurance in Higher Education of Kazakhstan: A Review of the System and Issues. The Rise of Quality Assurance in Asian Higher Education, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Younkyoo, and Fabio Indeo. 2013. The New Great Game in Central Asia Post 2014: The US ‘New Silk Road’ Strategy and Sino-Russian Rivalry. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 46: 275–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Jane. 2004. Internationalization Remodeled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales-. Journal of Studies in International Education 8: 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Jane. 2007. Cross-Border Higher Education: Issues and Implications for Quality Assurance and Accreditation. In Higher Education in the World 2007: Accreditation for Quality Assurance: What Is at Stake? Social Commitment of Universities. London: Palgrave Macmillian, pp. 134–46. Available online: https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2099/8109 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Koch, Natalie. 2014. The Shifting Geopolitics of Higher Education: Inter/Nationalizing Elite Universities in Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia, and Beyond. Geoforum 56: 46–54. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/11433667/The_shifting_geopolitics_of_higher_education_Inter_nationalizing_elite_universities_in_Kazakhstan_Saudi_Arabia_and_beyond (accessed on 28 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Kazuo, Takako Yuki, and Kyuwon Kang. 2010. Cross-Border Higher Education for Regional Integration:Analysis of the JICA-RI Survey on Leading Universities in East Asia. Working Paper. No. 26. JICA Research Institute. Online Submission. ERIC. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED519557 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Kuroda, Kazuo, Miki Sugimura, Yuto Kitamura, and Sarah Asada. 2018. Internationalization of Higher Education And Student Mobility in Japan and Asia. (Paper commissioned for the 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report, Migration, displacement and education: Building bridges, not walls). Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Available online: https://www.jica.go.jp/jica-ri/publication/other/l75nbg000010mg5u-att/Background_Kuroda.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Kursiv. 2019. Why do Kazakh Youth Go Abroad to Study. kursiv.kz. Available online: https://kursiv.kz/news/obrazovanie/2019-11/pochemu-kazakhstanskaya-molodezh-edet-uchitsya-za-rubezh (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Lassegard, James P. 2016. Educational Diversification Strategies: Japanese Universities’ Efforts to Attract International Students. In Reforming Learning and Teaching in Asia-Pacific Universities: Influences of Globalised Processes in Japan, Hong Kong and Australia. Edited by Chi-hung Clarence Ng, Robert Fox and Michiko Nakano. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects. Singapore: Springer, pp. 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jack T., and Aliya Kuzhabekova. 2018. Reverse Flow in Academic Mobility from Core to Periphery: Motivations of International Faculty Working in Kazakhstan. Higher Education 76: 369–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Christine S., David J. Therriaut, and Tracy Linderholm. 2012. On the Cognitive Benefits of Cultural Experience: Exploring the Relationship between Studying Abroad and Creative Thinking-Lee-2012—Applied Cognitive Psychology—Wiley Online Library. Applied Cognitive Psychology 26: 768–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Len, Christopher, Tomohiko Uyama, and Tetsuya Hirose, eds. 2008. Japan’s Silk Road Diplomacy. Paving the Road Ahead. Washington, DC and Stockholm: Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program. Available online: https://www.silkroadstudies.org/resources/pdf/Monographs/2008_12_BOOK_Len-Tomohiko-Tetsuya_Japan-Silk-Road-Diplomacy.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Le Ha, Phan. 2013. Issues Surrounding English, the Internationalisation of Higher Education and National Cultural Identity in Asia: A Focus on Japan. Critical Studies in Education 54: 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mei, and Mark Bray. 2007. Cross-Border Flows of Students for Higher Education: Push–Pull Factors and Motivations of Mainland Chinese Students in Hong Kong and Macau. Higher Education 53: 791–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarol, Tim, and Geoffrey Soutar. 2002. Push-Pull’ Factors Influencing International Student Destination Choice. International Journal of Educational Management 16: 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milian, Madeline, Matthew Birnbaum, Betty Cardona, and Bonnie Nicholson. 2015. Personal and Professional Challenges and Benefits of Studying Abroad. Journal of International Education and Leadership 5: 1–12. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1135354 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2012. The Strategy for Academic Mobility in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2012–2020. Available online: http://new1.tarsu.kz/images/dokumenty/STRATEGY_OF_ACADEMIC_MOBILITY.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. 2019. Statistics of studying in China in 2018. Government portal of the Ministry of Education. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/gzdt_gzdt/s5987/201904/t20190412_377692.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2004. MOFA: PRESS RELEASE: Visit by Minister for Foreign Affairs Ms. Yoriko Kawaguchi to Kazakhstan. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/kazakhstan/press0408.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2003. Decree of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated 25 April 2003 No. 405 On signing the Agreement between the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China on cooperation in the field of education. Information and legal system of regulatory acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan “Adilet.” adilet.zan.kz. Available online: http://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P030000405_ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2004. On the State Program for the Development of Education in the Republic of Kazakhstan for 2005–2010. Information and legal system of regulatory acts of the Republic of Kazakhstan “Adilet.” adilet.zan.kz. Available online: http://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/T040001459_ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Murakami, Yusuke. 2019. National and Local Educational Administration: A Comprehensive Analysis of Education Reforms and Practices. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafari, Javid, Alireza Arab, and Sina Ghaffari. 2017. Through the Looking Glass: Analysis of Factors Influencing Iranian Student’s Study Abroad Motivations and Destination Choice. SAGE Open, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bank of Kazakhstan. 2020. Direct Investments Statistic According to the Directional Principle. Nationalbank.Kz. Available online: https://nationalbank.kz/?docid=469&switch=english (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Nazarbayev University. 2013. Nazarbayev University Strategy 2013–2020. Available online: https://nu.edu.kz/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/NU_strategy_-final-1.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- OECD. 2017. Higher Education in Kazakhstan 2017. OECD ILibrary. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/higher-education-in-kazakhstan-2017_9789264268531-en (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Perna, Laura W., Kata Orosz, Zakir Jumakulov, Marina Kishkentayeva, and Adil Ashirbekov. 2015. Understanding the Programmatic and Contextual Forces That Influence Participation in a Government-Sponsored International Student-Mobility Program. Higher Education 69: 173–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prilipko, Arina. 2017. Managing Implementation of English Medium of Instruction in Higher Education in Kazakhstan: Practices and Challenges. Master’s thesis, Nazarbayev University, Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan. Available online: https://nur.nu.edu.kz/handle/123456789/2575 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet. 2006. Prime Minister Visits Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (Kazakhstan). Available online: https://japan.kantei.go.jp/koizumiphoto/2006/08/28kazakhstan_e.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Rakisheva, Botagoz Islyamovna, and Dmirtrii Vyacheslavovich Poletaev. 2011. Academic Migration from Kazakhstan to Russia as One of the Aspects of Strategic Cooperation in the Framework of the Development of the Customs Union. Eurasian Economic Integration 3: 84–101. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/uchebnaya-migratsiya-iz-kazahstana-v-rossiyu-kak-odin-iz-aspektov-strategicheskogo-sotrudnichestva-v-ramkah-razvitiya-tamozhennogo (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Rose, Heath, and Jim McKinley. 2018. Japan’s English-Medium Instruction Initiatives and the Globalization of Higher Education. Higher Education 75: 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryymin, Essi. 2015. Educational Innovation in Kazakhstan: The Case of Bolashak Finland. Finland: Häme University of Applied Sciences. Available online: http://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/97081 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Sagintayeva, Aida, and Zakir Jumakulov. 2015. Kazakhstan’s Bolashak Scholarship Program. International Higher Education 79: 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Yoshifumi. 2019. English Language Teaching and Learning in Japan: History and Prospect. In Education in Japan: A Comprehensive Analysis of Education Reforms and Practices. Edited by Yuto Kitamura, Toshiyuki Omomo and Masaaki Katsuno. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects. Singapore: Springer, pp. 211–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidahmetov, Marat, Dana Kulanova, Gulzhanar Abdikerimova, Ainur Myrkhalykova, and Gulzhan Abishova. 2014. Problem Aspects of Academic Mobility Are in Republic of Kazakhstan. Paper presented at 3rd Cyprus International Conference on Educational Research, CY-ICER 2014, Lefkosa, North Cyprus, January 30–February 1, vol. 143, pp. 482–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serikkaliyeva, Azhar E., Gulnar E. Nadirova, and Nurzhan B. Saparbayeva. 2019. Educational Migration from Kazakhstan to China: Reality and Prospects. Интеграция Образoвания 23: 504–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smirnova, Vera Aleksandrovna. 2005. International cooperation in the field of higher education as a factor in providing the Republic of Kazakhstan with qualified staff in the first half of the 1990s. Bulletin of Volgograd State University 9: 12–18. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/mezhdunarodnoe-sotrudnichestvo-v-sfere-vysshego-obrazovaniya-kak-faktor-obespecheniya-respubliki-kazahstan-kvalifitsirovannymi/viewer (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Sparks, Jason, Adil Ashirbekov, Aisi Li, Lynne Parmenter, Zakir Jumakulov, and Aida Sagintayeva. 2015. Becoming Bologna Capable: Strategic Cooperation and Capacity Building in International Offices in Kazakhstani HEIs. The European Higher Education Area, 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sputnik Kazakhstan. 2018. The Minister of Education of Russia Invited Kazakhstanis to Study at Universities for Free. News Network Agency. Available online: https://ru.sputniknews.kz/society/20180305/4815854/russia-kazakhstan-obrazovaniye-olga-vasilyeva.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Sputnik Kazakhstan. 2019. Students from Kazakhstan Counted in the FSB of Russia. News Network Agency. sputniknews.kz. Available online: https://ru.sputniknews.kz/Russia/20190819/11302524/studenty-kazakhstan-statistika-fsb-rossii.html (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Srikatanyoo, Natthawut, and Jürgen Gnoth. 2002. Country Image and International Tertiary Education. The Journal of Brand Management 10: 139–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Committee Ministry of National Economy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 2019. Statistics of foreign and mutual trade of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/official/industry/31/statistic/6 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Stigger, Elizabeth. 2018. Introduction: Internationalization in Higher Education. In Internationalization within Higher Education. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, Ulrich. 2015. Academic Mobility and Migration: What We Know and What We Do Not Know. European Review 23: S6–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, Ulrich. 2017. Internationalisation Trends in Higher Education and the Changing Role of International Student Mobility. Journal of International Mobility 5: 177–216. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/revue-journal-of-international-mobility-2017-1-page-177.htm (accessed on 28 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Tengrinews. 2019. How Much Does Kazakhstan Spend on Bolashakers and Are They Really Valuable Workers. tengrinews.kz. Available online: https://tengrinews.kz/article/skolko-kazahstan-tratit-bolashakerov-deystvitelno-oni-1110/ (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- The Bologna Process Center. 2020. Kazakhstan. The Bologna Process. The Key Indicators. 2010–2020.Pdf. Google Docs. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GqxB0pamlTdEeqVkJ5Mo526XwGVB464h/view?usp=sharing&usp=embed_facebook (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. 2005. Country Assistance Evaluation of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan Summary. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Available online: https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/evaluation/FY2004/text-pdf/uzbekistan.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- The World Bank. 2018. GDP Per Capita (Current US$)|Data. The World Bank IBRD/IDA. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Tlebaldiyeva, Meruert, Tilegen Sadikov, Gulmira Kamiyeva, and Moldahmetova Zulkiya. 2017. The Outcomes of Cooperation of Kazakhstan and Turkey in the Field of Education. International Journal OfEconomics and Business Administration 5: 96–103. Available online: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/43488 (accessed on 28 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2020. UIS Statistics. Available online: http://data.uis.unesco.org/# (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Uyama, Tomohiko. 2003. ‘Japanese Policies in Relation to Kazakhstan: Is There a “Strategy”?,’ In Thinking Strategically. In The Major Powers, Kazakhstan, and the Central Asian Nexus. Edited by Robert Legvold. London and Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 165–86. Available online: http://mitp-content-server.mit.edu:18180/books/content/sectbyfn?collid=books_pres_0&id=6802&fn=9780262621748_sch_0005.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Uyama, Tomohiko. 2008. Japan’s Diplomacy towards Central Asia in the Context of Japan’s Asian Diplomacy and Japan-U.S. Relations. In Japan’s Silk Road Diplomacy: Paving the Road Ahead. Edited by Christopher Len, Tomohiko Uyama and Tetsuya Hirose. Washington, DC and Stockholm: Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program, pp. 121–40. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/3090584/Japan_s_Diplomacy_towards_Central_Asia_in_the_Context_of_Japan_s_Asian_Diplomacy_and_Japan-U.S._Relations (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Valeev, Rafael Мirgasimovich, and Luiza Ravilevna Kadyrova. 2015. Humanitarian cooperation of the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Kazakhstan in the field of education (1990–2000s). Bulletin of Kazan State University of Culture and Arts 1: 1–6. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/gumanitarnoe-sotrudnichestvo-kitayskoy-narodnoy-respubliki-i-respubliki-kazahstan-v-sfere-obrazovaniya-1990-2000-e-gg (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Wadhwa, Rashim. 2015. Students on Move: Understanding Decision-Making Process and Destination Choice of Indian Students. Higher Education for the Future 31: 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waibel, Stine, Knut Petzold, and Heiko Rüger. 2018. Occupational Status Benefits of Studying Abroad and the Role of Occupational Specificity—A Propensity Score Matching Approach. Social Science Research 74: 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkins, Stephen, and Jeroen Huisman. 2011. International Student Destination Choice: The Influence of Home Campus Experience on the Decision to Consider Branch Campuses. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 21: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, Stephen, Farshid Shams, and Jeroen Huisman. 2012. The Decision-Making and Changing Behavioural Dynamics of Potential Higher Education Students: The Impacts of Increasing Tuition Fees in England. Educational Studies—EDUC STUD 39: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Molly. 2007. What Attracts Mainland Chinese Students to Australian Higher Education. Studies in Learning, Evaluation, Innovation and Developme Nt 4: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yonezawa, Akiyoshi, and Yukiko Shimmi. 2015. Transformation of University Governance through Internationalization: Challenges for Top Universities and Government Policies in Japan. Higher Education 70: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolution of the Government of the Repulic of Kazakhstan. 2007. Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Mutual Recognition of Documents on Education and Academic Degrees (Beijing, 20 December 2006). PARAGRAPH Information System. Available online: http://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=30082441 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Zenkova, Tatyana, and Gulmira Khamitova. 2018. English Medium-Instruction as a Way to Internationalization of Higher Education in Kazakhstan: An Opinion Survey in the Innovative University of Eurasia. E-TEALS 8: 126–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year of Graduation | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government (MEXT, JASSO) | 9 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 37 |

| Other Japanese funds | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Self-funding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 10 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 49 |

| Year of Registration | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students registered by Statistics of Japan * | 87 | 100 | 112 | 127 | 131 | 146 | 153 | 138 |

| Year of Graduation | * 2000 | 2007 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 15 | 1 | 1 | 17 | |||||||||

| Bachelor’s | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||||||||

| Master’s | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 26 | |

| PhD | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 54 |

| Area of Study | Technical Specialties | Humanities | Medicine & Biotechnology | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of students | 27 | 16 | 10 | 1 |

| Academic Year | Sending Japanese University | Program | Students | Mobility Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017 | The University of Tsukuba | Academic mobility | 2 | 8 months to 1 year |

| 2017–2018 | The University of Tsukuba | Academic mobility | 2 | 10 and 11 months |

| 2018–2019 | The University of Tsukuba | Winter school. Campus in Campus program | 13 | 3 weeks |

| Tokyo University of Foreign Studies | Winter school | 7 | 3 weeks | |

| The University of Tokyo | Spring school. Regional studies. Politics, Economics and Culture of Central Asia | 19 | 12 days | |

| Kochi University | 1 | 7 days | ||

| Kobe University | 1 | 7 days | ||

| 2019–2020 | The University of Tsukuba | Academic mobility by the program “Global educational program for training staff in the economic and scientific fields of the multi-linguistic system in Japan, the CIS countries and the Baltic countries” | 2 | From 8 months up to 1 year |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rustemova, A.; Meirmanov, S.; Okada, A.; Ashinova, Z.; Rustem, K. The Academic Mobility of Students from Kazakhstan to Japan: Problems and Prospects. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080143

Rustemova A, Meirmanov S, Okada A, Ashinova Z, Rustem K. The Academic Mobility of Students from Kazakhstan to Japan: Problems and Prospects. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(8):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080143

Chicago/Turabian StyleRustemova, Aktolkyn, Serik Meirmanov, Akito Okada, Zhanar Ashinova, and Kamshat Rustem. 2020. "The Academic Mobility of Students from Kazakhstan to Japan: Problems and Prospects" Social Sciences 9, no. 8: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080143

APA StyleRustemova, A., Meirmanov, S., Okada, A., Ashinova, Z., & Rustem, K. (2020). The Academic Mobility of Students from Kazakhstan to Japan: Problems and Prospects. Social Sciences, 9(8), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9080143