The Use of Facility Dogs to Bridge the Justice Gap for Survivors of Sexual Offending

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Survivor Journey

1.2. The Video-Recorded Interview

1.3. What about the Perceived Justice?

1.4. Facility Dogs as a Form of Quiet Companionship and Support

1.5. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Survivors

2.2.2. Interviewing Officers

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Data

3.2.1. A Change in Focus for The Survivor

3.2.2. A Difference in the Survivors’ Engagement

Changes in Demeanour

Consenting to the Police Interview

Enhanced Communication

3.2.3. The Dog as a Comforter to Calm the Survivor

3.2.4. Positive Environment

3.2.5. Summary

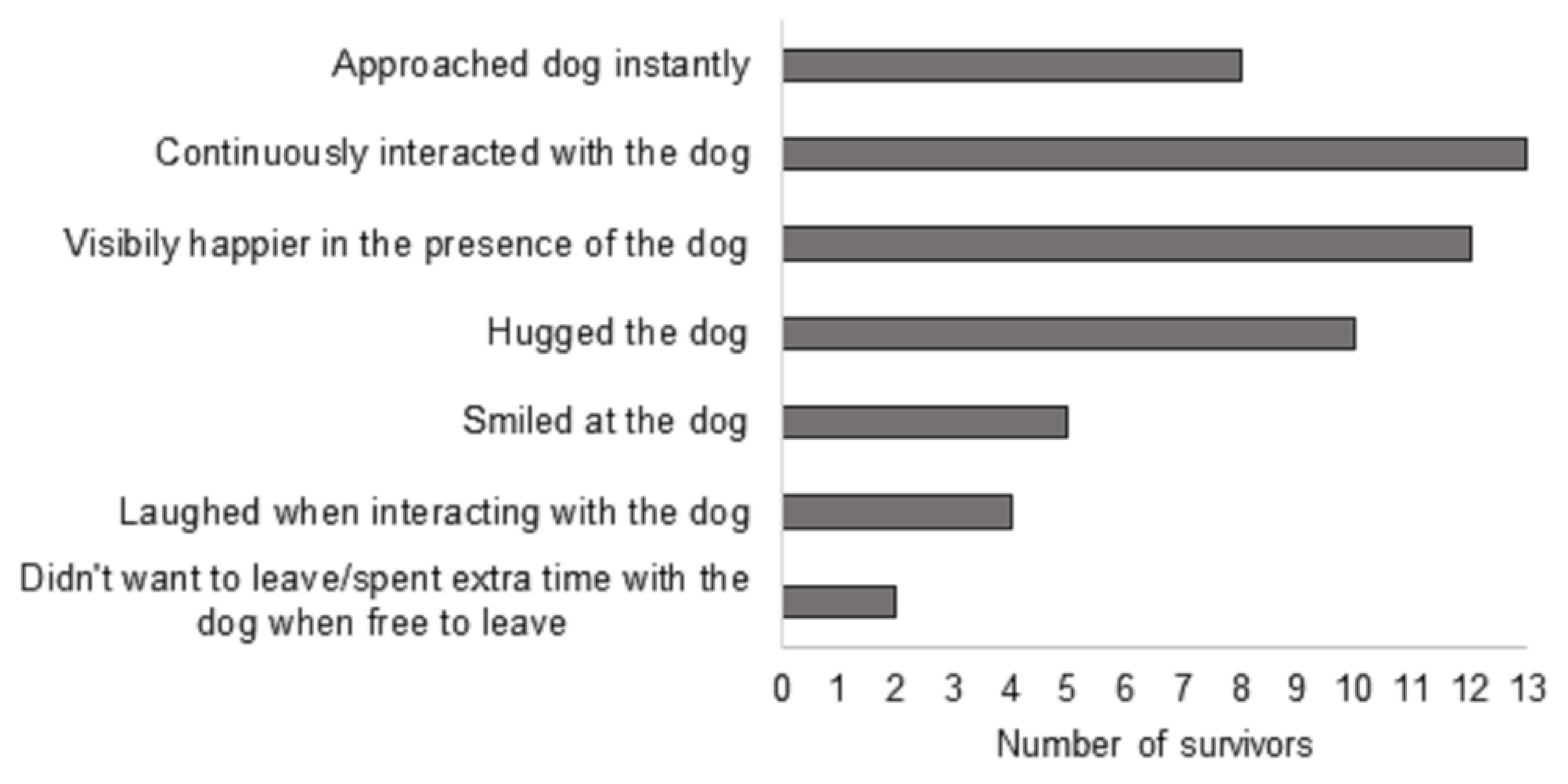

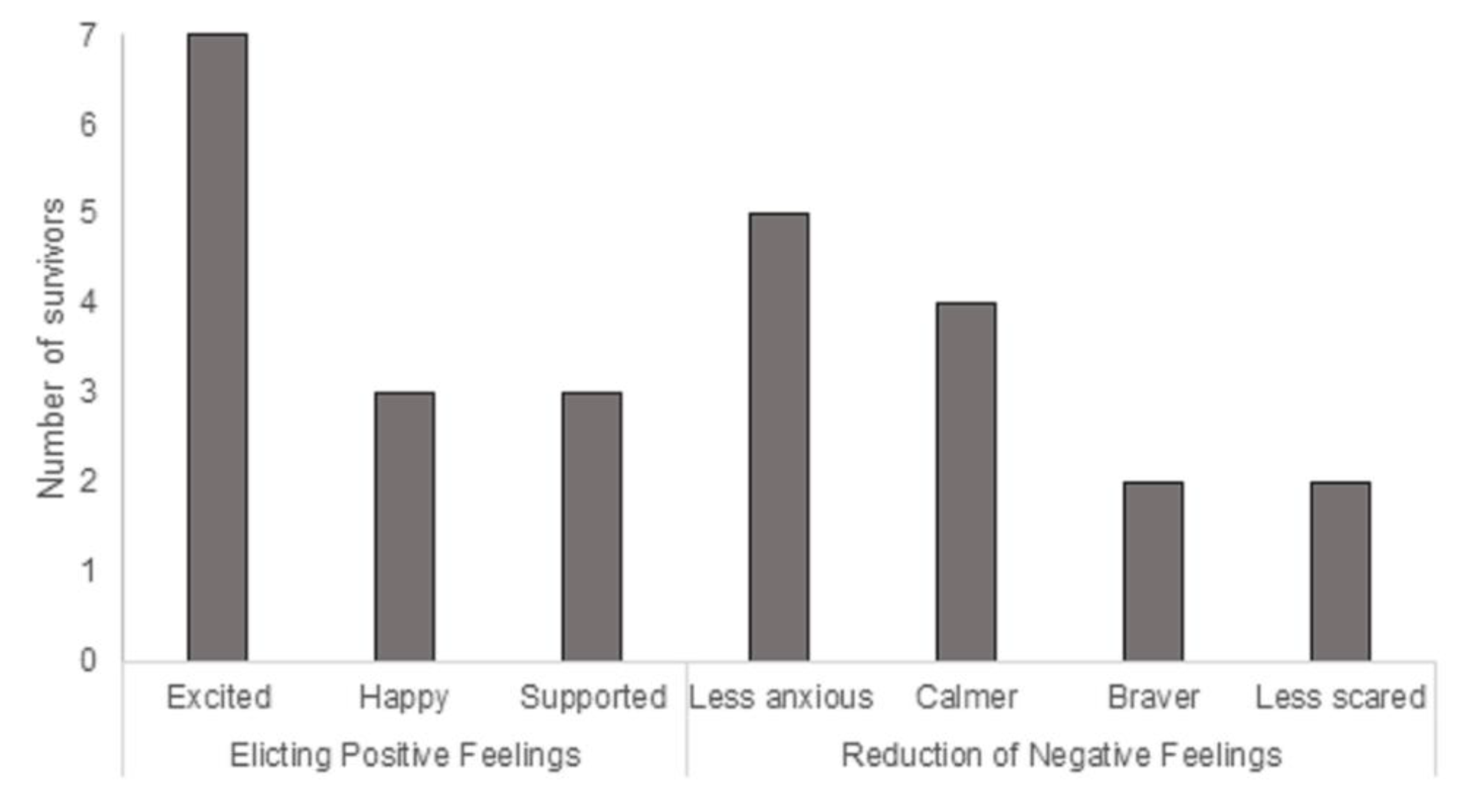

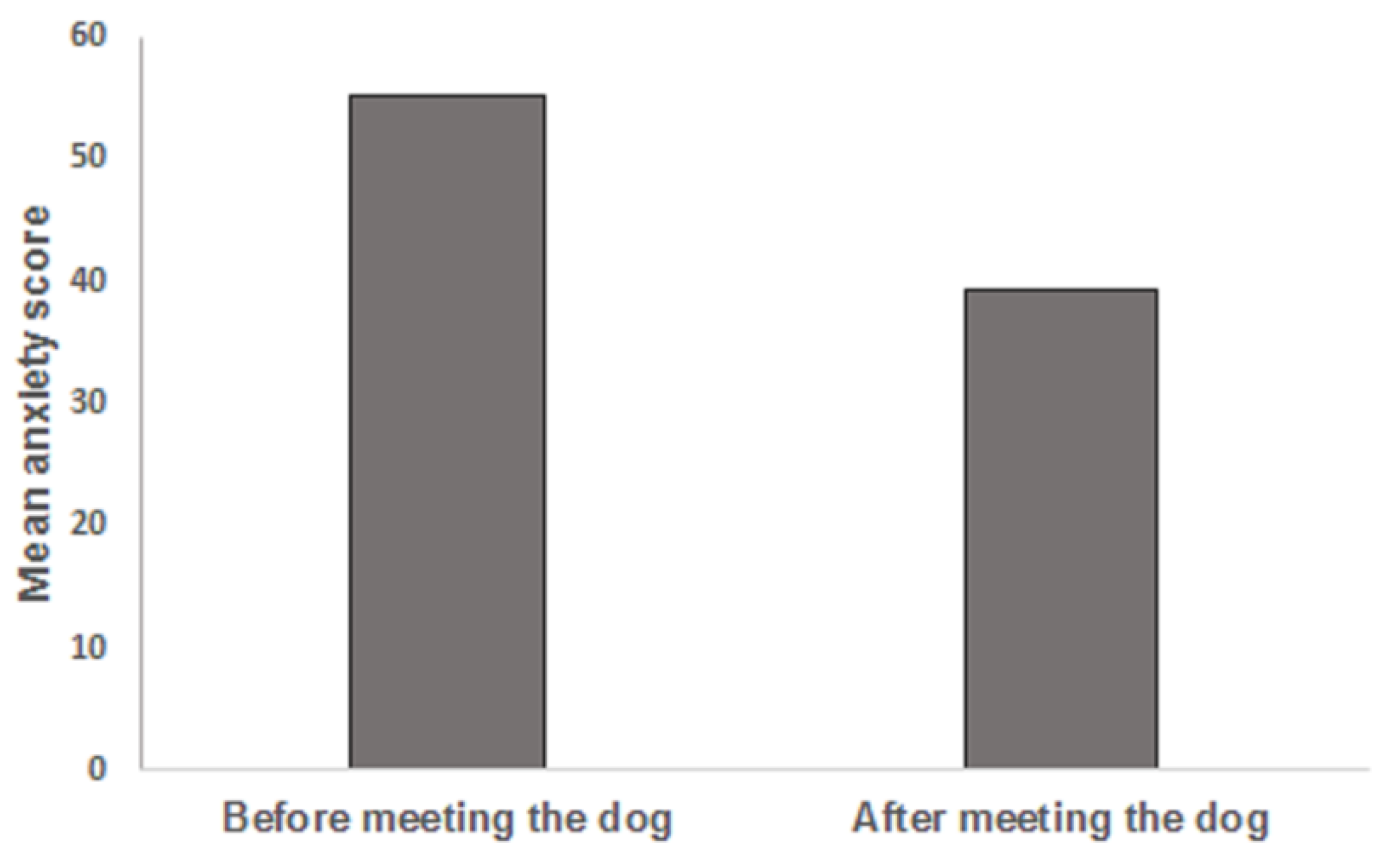

3.3. Survey Data

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allnock, Debra. 2015. What Do We Know about Child Sexual Abuse and Policing in England and Wales? Evidence Briefing for the National Policing Lead for Child Protection and Abuse Investigation. Luton: University of Bedfordshire, International Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Antaki, Charles, Emma Richardson, Elizabeth Stokoe, and Sara Willott. 2015. Police interviews with vulnerable people alleging sexual assault: Probing inconsistency and questioning conduct. Journal of Sociolinguistics 3: 328–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, Sandra B., Randolph T. Barker, Nancy L. McCain, and Christine M. Schubert. 2016. A randomized crossover exploratory study of the effect of visiting therapy dogs on college student stress before final exams. Anthrozoos 29: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baverstock, John. 2017. Process Evaluation of Pre-Recorded Cross Examination Pilot. London: Home Office. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, Helen, and Camille Warrington. 2015. Making Justice Work. Bedford: University of Bedfordshire. [Google Scholar]

- Boccaccini, Marcus T., and Stanley L. Brodsky. 2002. Believability of expert and lay witnesses: Implications for trial consultation. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 33: 384–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoms, Anthony, and Julian V. Roberts. 2010. Hearing the Victim: Adversarial Justice, Crime Victims, and the State. Cullompton: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, Sarah V. 2013. The use of therapy dogs in Indiana courtrooms: Why a dog might not be a defendant’s best friend. Indiana Law Review 46: 1289–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Oona, and Michele Burman. 2017. Reporting rape: Victim perspectives on advocacy support in the criminal justice process. Criminology and Criminal Justice 3: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Jennifer. 2011. We mind and we care but have things changed? Assessment of progress in reporting, investigating and prosecution of rape. Journal of Sexual Aggression 17: 263–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, Michele. 2009. Evidencing sexual assault: Women in the witness box. Probation Journal 56: 379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Rebecca, and Sharon M. Wasco. 2005. Understanding rape and sexual assault: 20 years of progress and future directions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 20: 127–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Cynthia K. 2012. Animal Assisted Therapy in Counseling. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Commissioner. 2015. Protecting Children from Harm: A Critical Assessment of Child Sexual Abuse in the Family Network in England and Priorities for Action. London: Children’s Commissioner for England. [Google Scholar]

- Coppinger, Roy, and Lorna Coppinger. 2001. Dogs: A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York: Scribne. [Google Scholar]

- Courthouse Dogs Foundation. 2019. Facility Dogs: Where Are They Working? Available online: https://courthousedogs.org/dogs/facility-dogs/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Crenshaw, David A. 2011. The play therapist as advocate for children in the court system. Play Therapy 6: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Beth, and L. L. Morton. 2006. An investigation of human-animal interactions and empathy as related to pet preference, ownership, attachment, and attitudes in children. Anthrozoos 19: 113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, Joanne, and Rita May. 1986. The effects of pet facilitative therapy on patients and staff in an adult day care centre. Activities, Adaptation and Aging 8: 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbacher, Kenneth A., Brian H. Bornstein, Steven D. Penrod, and E. Kiernan McGorty. 2004. A meta-analytic review of the effects of high stress on eyewitness memory. Law and Human Behaviour 28: 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellinger, Marianne. 2009. Using dogs for emotional support of testifying victims of crime. Animal Law 15: 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Irina, Stuart Thomas, and James Ogloff. 2013. Procedural justice in victim-police interactions and victims’ recovery from victimisation experiences. Policing and Society 24: 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. 2012. Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the council establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime. Official Journal of the European Union 315: 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Graham R. 2002. Qualitative Data Analysis: Explorations with NVivo. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grace, Sharon, Charles Lloyd, and Lorna J. F. Smith. 1992. Rape: From Recording to Conviction. London: Home Office Research Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Sheila, and Diane Hogan. 2005. Researching Children’s Experience: Approaches and Methods. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Jeanne, and Sue Lees. 1999. Policing Sexual Assault. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, Yomayra F., Natalie C. Tronson, Vladimir Jovasevic, Keisuke Sato, Anita L. Guedea, Hiroaki Mizukami, Katsuhiko Nishimori, and Jelena Radulovic. 2013. Fear-enhancing effects of septal oxytocin. Nature Neuroscience 16: 1185–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halligan, Sarah L., Tanja Michael, David M. Clark, and Anke Ehlers. 2003. Posttraumatic stress disorder following assault: The role of cognitive processing, trauma memory, and appraisals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71: 419–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamlyn, Becky, Andrew Phelps, and Ghazala Sattar. 2004a. Key Findings from the Surveys of Vulnerable and Intimidated Witnesses 2000/01 and 2003; Home Office Research Findings 240; London: Home Office.

- Hamlyn, Becky, Andrew Phelps, and Ghazala Sattar. 2004b. Are Special Measures Working? Evidence from Surveys of Vulnerable and Intimidated Witnesses; Home Office Research Study 283; London: Home Office.

- Hanway, Pamela, and Lucy Akehurst. 2018. Voices from the front line: Police officers’ perceptions of real-world interviewing with vulnerable witnesses. Investigative Interviewing: Research and Practice 9: 14–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hester, Marianne. 2013. From Report to Court: Rape Cases and the Criminal Justice System in the North East. Bristol: University of Bristol in association with the Northern Rock Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Emily S., and Graham M. Davies. 2012. Has the quality of investigative interviews with children improved with changes in guidance? An exploratory study. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 7: 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Government. 2018. Victims Strategy. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/victims-strategy (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- HMIC/HMCPSI. 2012. Forging the Links: Rape Investigation and Prosecution. A Joint Review by HMIC and HMCPSI. London: TSO. [Google Scholar]

- Hohl, Katrin, and Elisabeth A. Stanko. 2015. Complaints of rape and the criminal justice system: Fresh evidence on the attrition problem in England and Wales. European Journal of Criminology 12: 324–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home Office. 2004. Are Special Measures Working? Evidence from Surveys of Vulnerable and Intimidated Witnesses. London: Home Office Research Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. 2006. An Evaluation of the Use of Special Measures for Vulnerable and Intimidated Witnesses. London: Home Office Research Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, Noriah Mohd, and Abu Bakar. 2013. Developing sampling frame for case study: Challenges and conditions. World Journal of Education 4: 29. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Jan. 2011. Here we go round the review-go-round: Rape investigation and prosecution– are things getting worse not better? Journal of Sexual Aggression 17: 234–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Liz, Jo Lovett, and Linda Regan. 2005. A Gap or Chasm? Attrition in Reported Rape Cases. London: Home Office Research Study, vol. 293. [Google Scholar]

- Konradi, Amanda. 1999. “I don’t have to be afraid of you”: Rape survivors’ emotion management in court. Symbolic Interaction 22: 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, Cheryl A., Michele Thames, Colleen M. Ray, and John Kolassa. 2018. Examining the effects of a service-trained facility dog on stress in children undergoing forensic interview for allegations of child sexual abuse. Journal of Child. Sexual Abuse 27: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, Susan J., Ursula Lanvers, and Steve Shaw. 2003. Attrition in rape cases: Developing a profile and identifying relevant factors. British Journal of Criminology 43: 583–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, Paul D., and Jeanne E. Ormrod. 2001. Practical Research: Planning and Design, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Merrill Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Mike, Rod Morgan, and Robert Reiner. 2007. The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, Shana L. 2008. “I have heard horrible stories…”: Rape victim advocates’ perceptions of the re-victimization of rape victims by the police and medical system. Violence Against Women 14: 786–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majić, Tomislav, Hans Gutzmann, Andreas Heinz, Undine E. Lang, and Michael A. Rapp. 2013. Animal-assisted therapy and agitation and depression in nursing home residents with dementia: A matched case-control trial. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 21: 1052–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Nicola, Emma McKay, Clara Pelly, and Simon Cereda. 2019. Public Knowledge of and Confidence in the Criminal Justice System and Sentencing. London: Sentencing Council. [Google Scholar]

- Marteau, Theresa M., and Hilary Bekker. 1992. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychology 31: 301–06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2012. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 41. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, Jenny. 1990. In the box or on the box? The Pigot Report and child witnesses. Criminal Law Review, 363–70. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, Jenny. 2005. Proving consent in sexual cases: Legislative change and cultural evolution. International Journal of Evidence and Proof 9: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, Clare, and Nicole Westmarland. 2018. Kaleidoscopic Justice: Sexual violence and victim-survivors’ perceptions of justice. Social and Legal Studies 28: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, Clare, Julia Downes, and Nicole Westmarland. 2016. Seeking justice for survivors of sexual violence: Recognition, voice, and consequences. In Sexual Violence and Restorative Justice: Legal, Social and Therapeutic Dimensions. Edited by Estelle Zinsstag and Marie Keenan. London: Routledge, pp. 179–91. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, Lesley. 2014. The role of the specially trained officer in rape and sexual offence cases. Policing and Society 4: 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicholas, June, and Glyn M. Collis. 2006. Animals as social supports: Insights for understanding animal-assisted therapy. In Handbook on Animal Assisted Therapy. Edited by Aubrey H. Fine. San Diego: Elsevier, pp. 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice. 2012. Getting It Right for Victims and Witnesses. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/getting-it-right-for-victims-and-witnesses (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Ministry of Justice, Home Office, and The Office for National Statistics. 2013. An Overview of Sexual Offending in England and Wales. London: Official Statistics Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, Linda. 2010. Legal Architecture: Justice, Due Process and the Place of Law. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- National Police Chiefs’ Council. 2016. Policing Vision 2025. Available online: https://www.npcc.police.uk/documents/Policing%20Vision.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- O’Haire, Marguerite E. 2013. Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 43: 1606–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, Brendan M., Jane Creaton, Kevin Smith, and Rebecca Milne. 2016. Developing a professional identity in a new work environment: The views of defendant intermediaries working in the criminal courts. Journal of Forensic Practice 18: 155–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, Johannes S. J., and Roy Alec Meintjes. 2003. Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs. The Veterinary Journal 165: 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. 2013. An Overview of Sexual Offending in England and Wales. London: Office for National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. 2018. Sexual Offending: Victimisation and the Path through the Criminal Justice System. London: Office for National Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. 2019. Crime in England and Wales: Year Ending June 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/bulletins/crimeinenglandandwales/yearendingjune2019 (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Oliver-Hoyo, Maria, and DeeDee Allen. 2006. The use of triangulation methods in qualitative educational research. Journal of College Science Teaching 1: 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Jim, and Tiffany Bergin. 2010. The impact of criminal justice involvement on victims’ mental health. Journal of Traumatic Stress 23: 182–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Q. 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Sara. 2009. Redefining Justice: Addressing the Individual Needs of Victims and Witnesses. London: Ministry of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, Mia E., Agaia J. Trottier, Johan Bélteky, Lina S. V. Roth, and Per Jensen. 2017. Intranasal oxytocin and a polymorphism in the oxytocin receptor gene are associated with human-directed social behavior in golden retriever dogs. Hormones and Behavior 95: 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quas, Jodi A., and Gail S. Goodman. 2012. Consequences of criminal court involvement for child victims. Psychology Public Policy, and Law 18: 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rape Crisis Network. 2018. Hearing Every Voice—Towards a New Strategy on Vulnerable Witnesses in Legal Proceedings. Ireland: Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, Clinton R. 2003. Actions speak louder than words: Close relationships between humans and nonhuman animals. Symbolic Interaction 26: 405–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, Gabriela N. 2010. Court Facility Dogs—Easing the apprehensive witness. Colorado Lawyer 39: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck, Sabrina E. B., Natasha A. Emmerson, Aubrey H. Fine, and Kimberley D. Lakes. 2013. Canine-assisted therapy for children with ADHD: Preliminary findings from the positive assertive cooperative kids study. Journal of Attention Disorders 19: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, David. 2013. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook, 4th ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Spruin, Elizabeth, and Katarina Mozova. 2018. Dogs in the criminal justice system: Consideration of facility and therapy dogs. Pet Behaviour Science 5: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruin, Elizabeth, Nicole Holt, Ana Ferdandez, and Anke Franz. 2016. The use of dogs in the courtroom. In Crime and Criminal Behaviour. Edited by Analise Klein. New York: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Spruin, Elizabeth, Katarina Mozova, Tammy Dempster, and Susanna Mitchell. 2019a. Exploring the impact of specially trained dogs on the court experiences of survivors of sexual offending in England and Wales: An exploratory case study. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruin, Elizabeth, Katarina Mozova, Anke Franz, Susanna Mitchell, Ana Fernandez, Tammy Dempster, and Nicole Holt. 2019b. The use of therapy dogs to support court users in the waiting room. International Criminal Justice Review 29: 284–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 1978. The case study method in social inquiry. Educational Researcher 7: 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, Robert E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research: Perspective in Practice. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton, Mary. 2016. Effectiveness of animal assisted therapy after brain injury: A bridge to improved outcomes in CRT. NeuroRehabilitation 39: 135–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svedin, Carl G., and Kristina Back. 2003. Why Don’t They Tell? About Being Exploited in Child Pornography. Stockholm: Rädda Barnen. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, Abbas M., and Charles B. Teddlie. 2003. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tellis, Winston M. 1997. Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Victims’ Commissioner. 2016. What Works in Supporting Victims of Crime. London: Office of the Victims Commissioner. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Paul G., Peter G. Mertin, Don F. Verlander, and Cris F. Pollard. 1995. The effects of a ‘‘pets as therapy’’ dog on persons with dementia in a psychiatric ward. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 42: 161–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weems, Noreal. 2013. Real or fake: Animals can make a difference in child abuse proceedings. Mid-Atlantic Journal on Law and Public Policy 117: 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Deborah L. 2009. The effects of animals on human health and well-being. Journal of Social Issues 65: 523–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemmers, Jo-Anne, Rien Van der Leeden, and Herman Steensma. 1995. What is procedural justice: Criteria used by Dutch victims to assess the fairness of criminal justice procedures. Social Justice Research 8: 329–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westmarland, Nicole, and Geetanjali Ganjoli. 2012. International Approaches to Rape. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatcroft, Jacqueline M., Graham F. Wagstaff, and Annmarie Moran. 2009. Revictimizing the victim? How rape victims experience the UK legal system. Victims and Offenders 4: 265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Richard. 1984. A note on attrition of rape cases. British Journal of Criminology 25: 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Hai-Peng, Liwei Wang, Liqun Han, and Stephani C. Wang. 2013. Nonsocial functions of hypothalamic oxytocin. ISRN Neuroscience 2013: 179272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 1st ed. Beverly Hills: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd ed. Beverly Hills: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act. 1999. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1999/23/contents (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Zimmer, Randi M. 2014. Partnering Shelter Dogs with Prison Inmates: An Alternative Strategy to Reduce Recidivism and Teach Social Therapy. Master’s thesis, American Public University, Charles Town, WV, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Survivor Details | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Type of Crime | Age | Gender | Additional Info | Additional Support Present | Officer Title | Officer Gender | Police Interview Length |

| P1 | Sexual assault | 16 | F | Father (P1b) | Police Constable (P1a) | M | 45 min | |

| P2 | Sexual offences | 12 | F | ADHD | Mother (P2b) | Detective Constable—Child Protection (P2a) | F | 60 min |

| P3 | Sexual offences | 16 | F | Mother (P3b) | Police Constable (P3a) | F | 45 min | |

| P4 | Sexual offences | 21 | F | Learning difficulties | No one | Detective Constable (P4a) | M | 70 min |

| P5 | Sexual offences | 7 | F | Mother (P5c); Intermediary (P5b) | Detective Constable—Vulnerable Investigation Team (P5a) | F | 65 min | |

| P6 | Sexual offences | 8 | M | ADHD | Mother (P6c); Intermediary (P6b) | Detective Constable (P6a) | F | 24 min |

| P7 | Sexual offences | 11 | M | Mother (P7b) | Detective Constable (P7a) | F | 56 min | |

| P8 | Sexual offences | 13 | F | Autism | Mother (P8b) | Detective Constable (P8a) | F | 75 min |

| P9 | Sexual offences | 20 | F | Anxiety | No one | Detective Constable (P9a) | F | 35 min |

| P10 | Sexual assault | 10 | F | Autism | Mother (P10c); Intermediary (P10b); | Detective Constable—Vulnerable Investigation Team (P10a) | F | 25 min |

| P11 | Rape | 27 | F | Learning difficulties | Mother (P11b) | Detective Constable (P11a) | F | 65 min |

| P12 | Rape of a child under 13 | 11 | F | Autism | Mother (P12b) | Detective Constable—Child Protection (P12a) | F | 60 min |

| P13 | Rape of a child under 13 | 13 | F | Autism | Mother (P13c); Intermediary (P13b) | Detective Constable (P13a) | F | 180 min |

| Theme | Number of Cases | Example Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Change of focus for the survivor | n = 13 | P7b: “He [the Facility Dog] really has changed the whole focus for [the witness]. Before it was a scary thing he couldn’t do, but now, it’s something he is excited for.” |

| A difference in the survivors’ engagement (Sub-themes: Change in demeanour; Consenting to the police interview; Enhanced communication) | n = 12 | P12a: “The interview went very well, she disclosed and talked more than she had ever in the past. I’ve been working as an interviewer for a few years and never have I seen such a change in response about attending an interview. When I met the individual in the past, she seemed quite withdrawn and timid, but with the dog she was so much more animated. Whereas before she was dreading the interview, she became almost excited about it now that [the Facility Dog] was around.” |

| The dog as a comforter to keep the survivor calm | n = 13 | P11: “[He] kept me completely calm. His whole presence that he was there, it was so comforting. I was holding his leash the whole time, I didn’t even need my own squishy toy. He was totally brilliant. I am so happy he was here.” |

| Positive environment | n = 10 | P5c: “This is not a child-friendly place, it’s not an inviting place for children. [The Facility Dog] makes it inviting, I think, he makes it feel as though you’re not about to go into an interview.” |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spruin, E.; Mozova, K.; Dempster, T.; Freeman, R. The Use of Facility Dogs to Bridge the Justice Gap for Survivors of Sexual Offending. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060096

Spruin E, Mozova K, Dempster T, Freeman R. The Use of Facility Dogs to Bridge the Justice Gap for Survivors of Sexual Offending. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(6):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060096

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpruin, Elizabeth, Katarina Mozova, Tammy Dempster, and Rachel Freeman. 2020. "The Use of Facility Dogs to Bridge the Justice Gap for Survivors of Sexual Offending" Social Sciences 9, no. 6: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060096

APA StyleSpruin, E., Mozova, K., Dempster, T., & Freeman, R. (2020). The Use of Facility Dogs to Bridge the Justice Gap for Survivors of Sexual Offending. Social Sciences, 9(6), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060096