The Treatment of Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Spanish Curriculum of the Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO): An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Teaching

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Educational Legislation

1.2. Origins and Present Time of the Socioeconomic Inequalities: The Acquisition of Significant Learning

1.3. The Need to Teach Inequalities from an Interdisciplinary Perspective

2. Research Design

2.1. Problems and Objectives

- Specific problem 1: how do state and autonomous community curricula differ with regard to socio-economic imbalances?

- Specific problem 2: what subjects and curricular elements incorporate aspects of socio-economic inequality?

- Specific problem 3: what links are established between past and current socio-economic problems and crises?

- Specific problem 4: what kind of multi-causality and interdisciplinarity on inequality does the curriculum include?

- Specific problem 5: what solutions does the Spanish national curriculum propose to solve or reduce the inequalities of our society and the rest of the world?

- Objective 1: to find out the differential treatment of socioeconomic inequality in the Spanish and regional curricula.

- Objective 2: to ascertain the socioeconomic problems included in the seven subjects analyzed and the six curricular elements.

- Objective 3: to search the regulations under analysis for possible links between the past and the present world in order to better face the problem of socioeconomic dissymmetries.

- Objective 4: to determine in the analyzed legislation multi-causal and interdisciplinary aspects that work on the consequences of socio-economic inequalities.

- Objective 5: to find in the curricula keywords and contents to raise awareness and reduce disparities in Spain and in the rest of the world.

2.2. Methodology, Sample, and Data Collection

2.3. Instruments and Data Analysis

2.3.1. Keywords

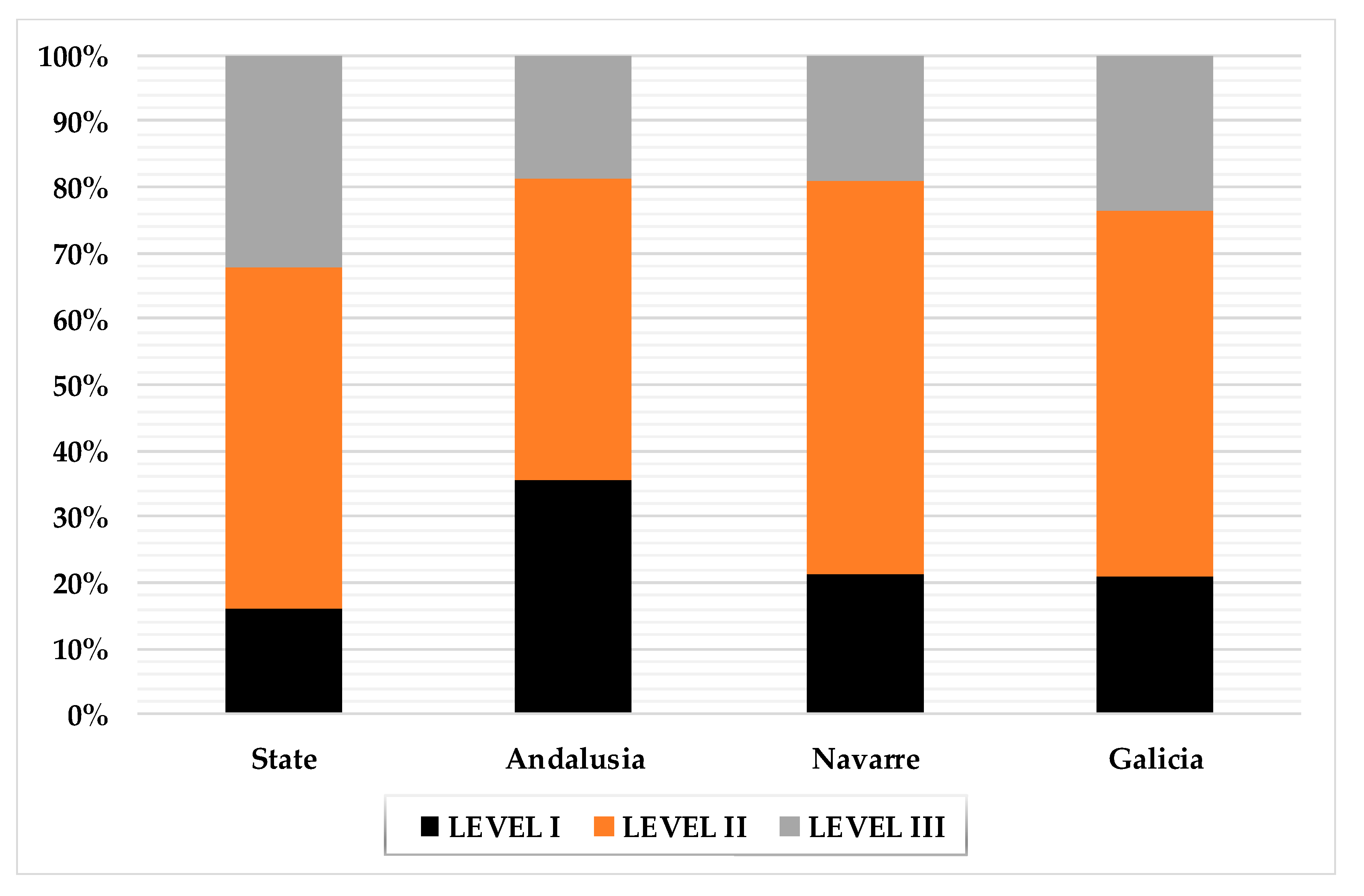

2.3.2. Category System by Levels of Progression

3. Results

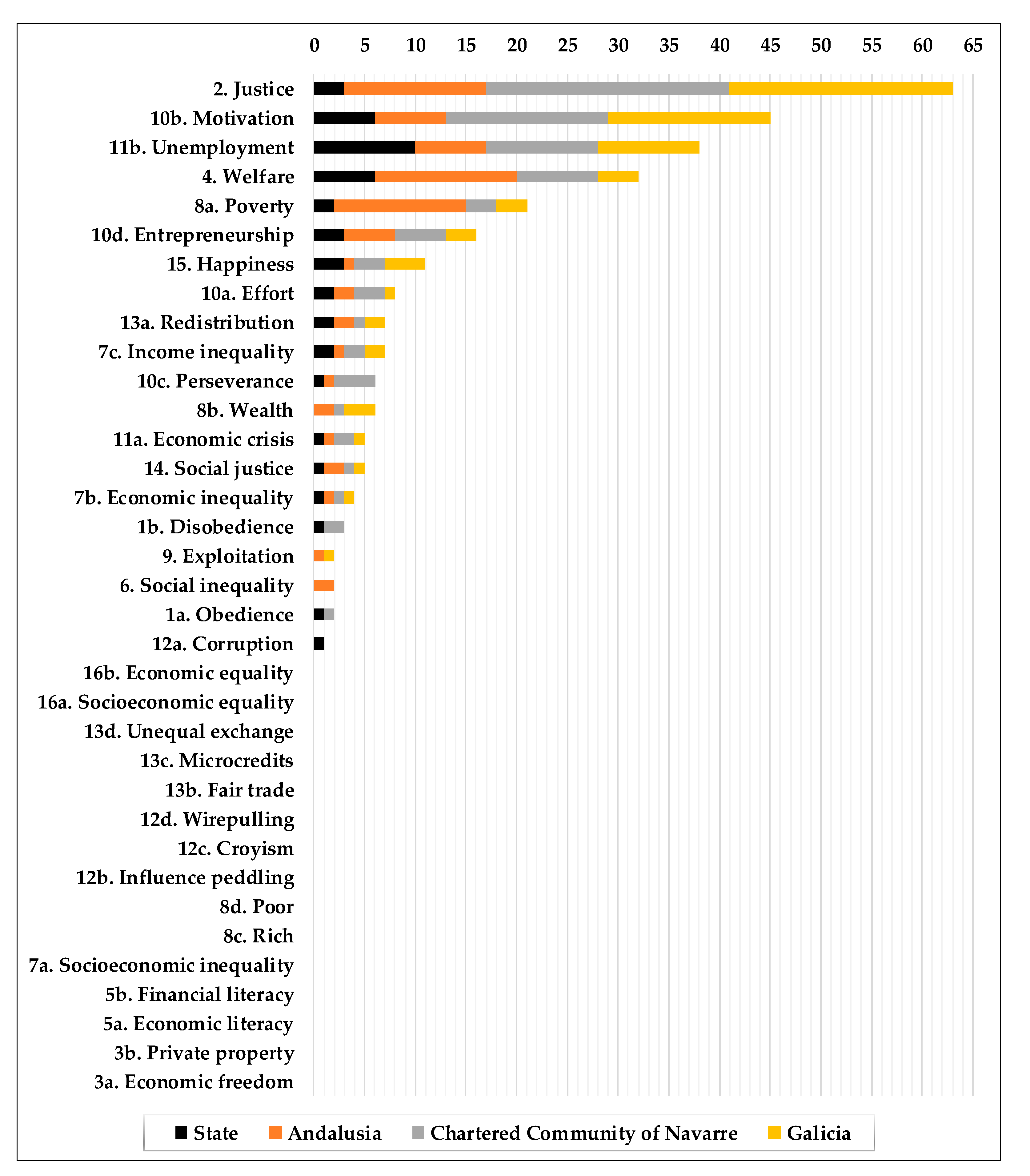

3.1. Adminstrative Bodies

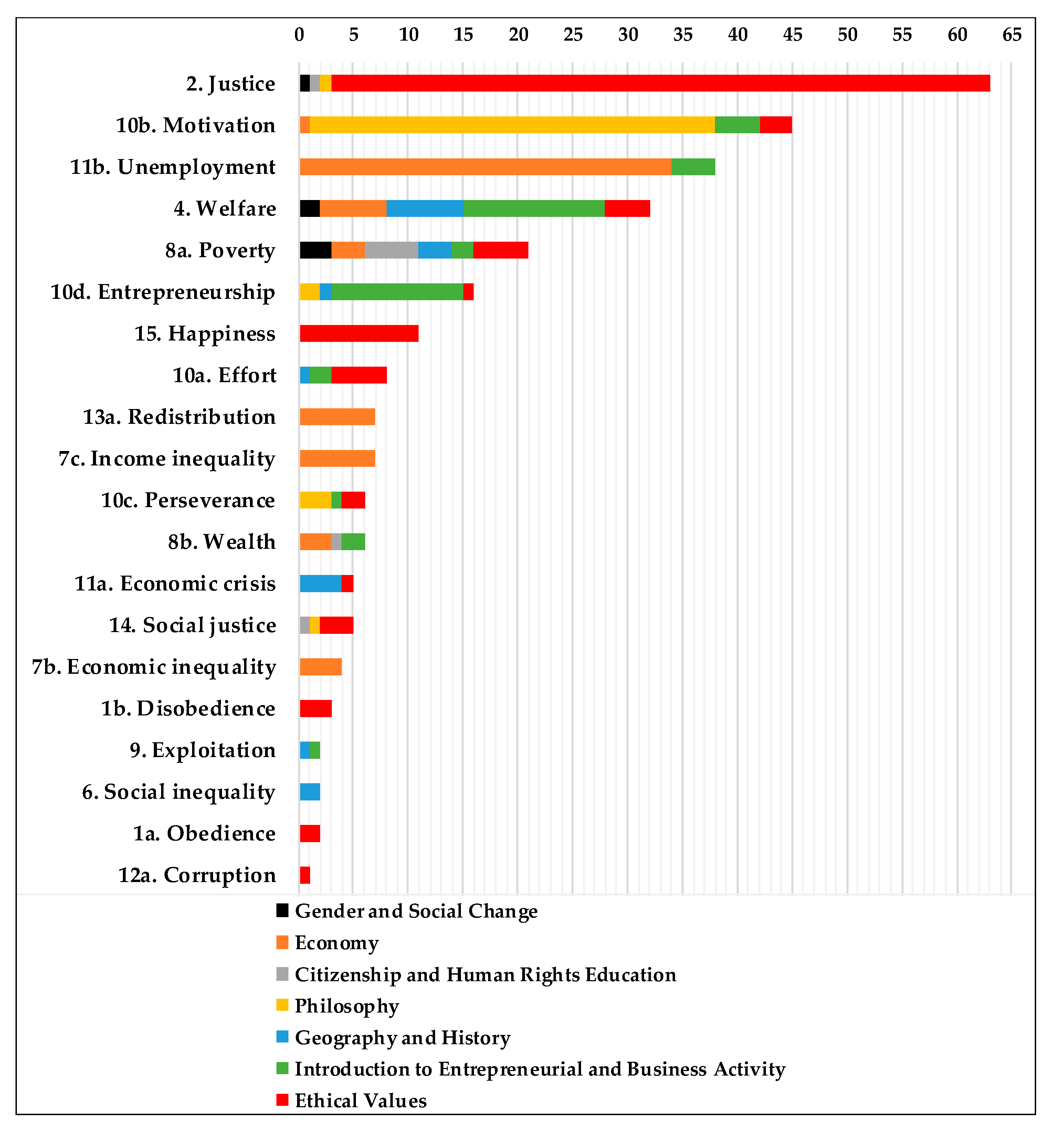

3.2. Subjects

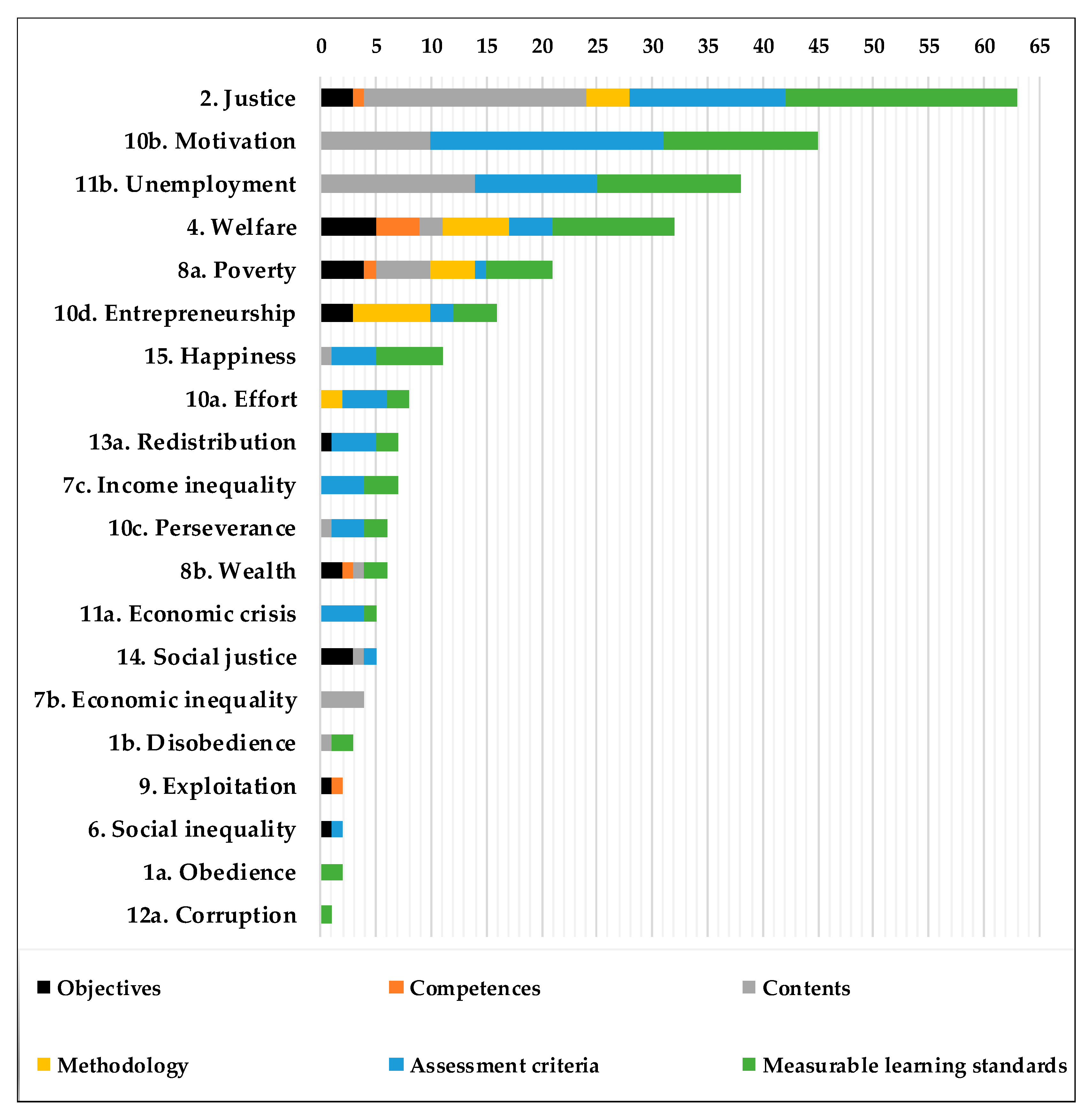

3.3. Curricular Elements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Subjects | Keywords | Categories | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender and Social Change 2. Economy 3. Citizenship and Human Rights Education 4. Philosophy 5. Geography and History 6. Introduction to Entrepreneurial and Business Activity 7. Ethical Values | 1a. Obedience 1b. Disobedience 2. Justice 3a. Economic freedom 3b. Private property 4. Welfare 5a. Economic literacy 5b. Financial literacy 6. Social inequality 7a. Socioeconomic inequality 7b. Economic inequality 7c. Income inequality 8a. Poverty 8b. Wealth 8c. Rich 8d. Poor 9. Exploitation 10a. Effort 10b. Motivation 10c. Perseverance 10d. Entrepreneurship 11a. Economic crisis 11b. Unemployment 12a. Corruption 12b. Influence peddling 12c. Cronyism 12d. Wirepulling 13a. Redistribution 13b. Fair trade 13c. Microcredits 13d. Unequal exchange 14. Social justice 15. Happiness 16a. Socioeconomic equality 16b. Economic equality | 1. Objectives 2. Competences 3. Contents 4. Methodology 5a. Assessment criteria 5b. Measurable learning standards | Number of times the keyword is repeated in the corresponding category. |

Appendix B

| Subjects | Keywords | Categories | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7b | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5b | 1 |

| 2 | 11b | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | 11b | 5a | 3 |

| 2 | 11b | 5b | 4 |

| 2 | 13a | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 13a | 5b | 1 |

| 4 | 10b | 5a | 3 |

| 4 | 10b | 5b | 1 |

| 4 | 10c | 5a | 1 |

| 4 | 10d | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 8a | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 11a | 5a | 1 |

| 6 | 4 | 5b | 4 |

| 6 | 10a | 5b | 1 |

| 6 | 10b | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | 10d | 5a | 1 |

| 6 | 10d | 5b | 1 |

| 6 | 11b | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 1a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 1b | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 5b | 3 |

| 7 | 8a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 10a | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 10b | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 12a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5b | 2 |

| Subjects | Keywords | Categories | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 1 | 8a | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 8a | 3 | 1 |

| 1 | 8a | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7b | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 8a | 4 | 1 |

| 2 | 10b | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 11b | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 11b | 5a | 3 |

| 2 | 13a | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 13a | 5a | 1 |

| 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 3 | 8a | 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 8a | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | 8b | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 14 | 5a | 1 |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 4 | 10b | 5a | 6 |

| 4 | 10c | 5a | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 6 | 5a | 1 |

| 5 | 10a | 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 11a | 5a | 1 |

| 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 8a | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 8b | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | 10d | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 11b | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 7 | 2 | 5a | 4 |

| 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 7 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| 7 | 8a | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 8a | 4 | 1 |

| 7 | 10a | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 14 | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5a | 1 |

| Subjects | Keywords | Categories | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7b | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5b | 1 |

| 2 | 8a | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 8b | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 11b | 3 | 2 |

| 2 | 11b | 5a | 3 |

| 2 | 11b | 5b | 5 |

| 2 | 13a | 5a | 1 |

| 4 | 10b | 3 | 2 |

| 4 | 10b | 5a | 6 |

| 4 | 10b | 5b | 5 |

| 4 | 10c | 5a | 1 |

| 4 | 10d | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 8a | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 11a | 5a | 1 |

| 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 4 | 5b | 3 |

| 6 | 10a | 5b | 1 |

| 6 | 10b | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 10c | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | 10d | 4 | 2 |

| 6 | 10d | 5a | 1 |

| 6 | 10d | 5b | 1 |

| 6 | 11b | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 1a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 1b | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 1b | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| 7 | 2 | 5a | 5 |

| 7 | 2 | 5b | 8 |

| 7 | 8a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 10a | 4 | 1 |

| 7 | 10a | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 10b | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 10c | 5b | 2 |

| 7 | 11a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5b | 2 |

| Subjects | Keywords | Categories | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7b | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 7c | 5b | 1 |

| 2 | 8a | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 8b | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 8b | 5b | 1 |

| 2 | 11b | 3 | 3 |

| 2 | 11b | 5a | 2 |

| 2 | 11b | 5b | 4 |

| 2 | 13a | 5a | 1 |

| 2 | 13a | 5b | 1 |

| 4 | 10b | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 10b | 5a | 5 |

| 4 | 10b | 5b | 5 |

| 4 | 14 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 4 | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 8a | 5b | 1 |

| 5 | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 10d | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 11a | 5a | 1 |

| 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 6 | 4 | 5b | 1 |

| 6 | 8b | 5b | 1 |

| 6 | 10b | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | 10d | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 11b | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| 7 | 2 | 5a | 5 |

| 7 | 2 | 5b | 10 |

| 7 | 8a | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 10a | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 10b | 5b | 1 |

| 7 | 10d | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 3 | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5a | 1 |

| 7 | 15 | 5b | 2 |

References

- Abril, Daniel. 2012. Contextos Arqueológicos de la Actividad Metalúrgica en el Suroeste de la Península Ibérica (III Milenio A.N.E.). La Aplicación de Análisis Zooarqueológicos Multivariables, Espaciales y Cuantitativos para la Explicación de las Relaciones Sociales. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva, pp. 1–411. Available online: http://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/handle/10272/6025 (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Abril, Daniel, and José María Cuenca. 2016. Prehistoria y Arqueología en 1º de ESO: Análisis documental y propuesta didáctica para la explicación de la organización social pasada y actual. Clío. History and History Teaching 42: 1–33. Available online: http://clio.rediris.es/ (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Acevedo, José Antonio. 2004. Reflexiones sobre las finalidades de la enseñanza de las ciencias: Educación científica para la ciudadanía. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 1: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, Eileen. 2011. Macroeconomic policy, labour market institutions and employment outcomes. Work, Employment and Society 25: 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramendi Jauregui, Pello, Rosa María Arburua Goienetxe, and Karmele Buján Vidales. 2018. El aprendizaje basado en la indagación en la enseñanza secundaria. Revista de Investigación Educativa 36: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquín, Javier. 2003. Desigualdad y educación: Cambio social y reto educativo. In Conocimiento, ética y esperanza: Homenaje del Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar de la Universidad de Málaga al profesor Antonio Fortes Ramírez. Edited by Remedios Beltrán and Miguel Ángel Santos. Málaga: Universidad de Málaga, pp. 383–402. [Google Scholar]

- Barrue, Catherine, and Virginie Albe. 2013. Citizenship Education and Socioscientific Issues: Implicit Concept of Citizenship in the Curriculum, Views of French Middle School Teachers. Science & Educaction 22: 1089–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavot, Aaron, and Cecilia Braslavsky, eds. 2006. School Knowledge in Comparative and Historical Perspective: Changing Curricula in Primary and Secondary Education. Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong Press, Amsterdam: Springer, pp. 1–306. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, R. Aexander, Penny Bickle, Linda Fibiger, Geoff M. Nowell, Christopher W. Dale, Robert E. M. Hedges, Julie Hamilton, Joachim Wahl, Michael Francken, Gisela Grupe, and et al. 2012. Community differentiation and kinship among Europe’s first farmers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 109: 9326–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal-Verdugo, Lorenzo E., Davide Furceri, and Dominique Guillaume. 2013. Banking crises, labor reforms, and unemployment. Journal of Comparative Economics 41: 1202–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieler, Andreas, and Adam David Morton. 2014. Uneven and Combined Development and Unequal Exchange: The Second Wind of Neoliberal `Free Trade’? Globalizations 11: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Paul, and Dylan Wiliam. 2005. Lessons from around the world: How policies, politics and cultures constrain and afford assessment practices. The Curriculum Journal 16: 249–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix, Carles. 2010. Origins and Persistence of Economic Inequality. Annual Review of Political Science 13: 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Gordon. 2009. The ontological turn in education. Journal of Critical Realism 8: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, Linda. 2005. The making of South Africa’s National Curriculum Statement. Journal of Curriculum Studies 37: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, César, ed. 1999. Psicología de la instrucción: La enseñanza y el aprendizaje en la Educación y Secundaria. Barcelona: Horsori, pp. 1–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Maeve. 2016. Civil obedience and disobedience. Philosophy and Social Criticism 42: 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W, and Cheryl N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches, 4th ed. London: Sage, pp. 1–488. [Google Scholar]

- Cuban, Larry. 1992. Curriculum stability and change. In Handbook of Research on Curriculum: A Project of the American Educational Research Association. Edited by Philip W. Jackson. New York: Macmillan, pp. 216–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, José María. 2002. El Patrimonio en la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Análisis de Concepciones, Dificultades y Obstáculos para su Integración en la Enseñanza Obligatoria. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva, pp. 1–537. Available online: http://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/handle/10272/2648 (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Cuenca, José María, Jesús Estepa, and Myriam José Martín. 2017. Heritage, education, identity and citizenship. Teachers and textbook in compulsory education. Revista de Educación 375: 131–52. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:f2149c2a-599a-49cd-b2d2-a5d280cda3aa/06cuenca-pdf.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2019).

- de Alba, Nicolás. 2004a. La desigualdad social como contenido escolar. Un análisis desde la perspectiva del conocimiento profesional en Educación Secundaria. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla, pp. 1–826. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/15009/K_D_Tesis_116.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- de Alba, Nicolás. 2004b. Modelos de profesores y organización del currículo en torno a problemas. Una hipótesis de progresión para el contenido de la desigualdad. Íber. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 39: 103–9. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 2013. Strategies of Qualitative Inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 1–480. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Moreno, Naira, and María Rut Jiménez-Liso. 2012. Las controversias sociocientíficas: Temáticas e importancia para la educación científica. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias 9: 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doncel, David. 2014. Organización curricular de las identidades colectivas en España. Revista de Educación 366: 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estepa, Jesús, Rosa María Ávila, and Mario Ferreras. 2008. Primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions about heritage education: A comparative analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education 24: 2095–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2019. Country Report Spain 2019. Brussels: Commission staff Working Document, pp. 1–114. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c42f62c8-3b6b-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Eurostat. 2019. Early Leavers from Education and Training. Luxembourg: Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title = Early_leavers_from_education_and_training (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Eurostat. 2020. Unemployment by Sex and Age—Monthly Average. Luxembourg: Statistics Explained. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=une_rt_m&lang=en (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Fernández, Eva, Alejandro Pérez-Pérez, Cristina Gamba, Eva Prats, Pedro Cuesta, Josep Anfruns, Miquel Molist, Eduardo Arroyo-Pardo, and Daniel Turbón. 2014. Ancient DNA Analysis of 8000 B.C. Near Eastern Farmers Supports an Early Neolithic Pioneer Maritime Colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands. PLoS Genetics 10: 1–16. Available online: http://journals.plos.org/plosgenetics/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401&type=printable (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Fleurbaey, Marc. 2014. The facet of exploitation. Journal of Theoretical Politics 26: 653–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, James K., and Maureen Berner, eds. 2004. Desigualdad y Cambio Industrial: Una Perspectiva Global. Madrid: Akal, pp. 1–328. [Google Scholar]

- García, J. Eduardo. 1999. Una hipótesis de progresión sobre los modelos de Desarrollo en Educación Ambiental. Investigación en la Escuela 37: 15–32. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/60073/Una%20hip%c3%b3tesis%20de%20progresi%c3%b3n%20sobre%20los%20modelos%20de%20desarrollo%20en%20Educaci%c3%b3n%20Ambiental.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- García Ruiz, Carmen Rosa. 2008. El currículo de Ciencias Sociales en Educación Primaria. In Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Currículo Escolar y Formación del Profesorado: La Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales en los Nuevos Planes de Estudio. Edited by Rosa María Ávila, Alcázar Cruz and María Consuelo Díez. Jaén: Asociación Universitaria del Profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, pp. 313–30. Available online: http://www.didactica-ciencias-sociales.org/publicaciones_archivos/2008-jaen-libro.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2019).

- Goerlich, Francisco José, and Antonio Villar. 2009. Inequality and welfare in Spain and its autonomous communities (1973–2003). Revista de Economía Aplicada 17: 119–52. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19487/1/MPRA_paper_19487.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2019).

- Gómez, Cosme Jesús, and Raimundo A. Rodríguez. 2014. Aprender a enseñar ciencias sociales con métodos de indagación. Los estudios de casos en la formación del profesorado. REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria 12: 307–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoon, Deborah. 2017. An Economy for the 99%. Oxford: Oxfam GB, pp. 1–48. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/oxfam-us/www/static/media/files/bp-economy-for-99-percent-160117-en.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Hernàndez, F. Xavier. 2002. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia. Barcelona: Graó, pp. 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Heyes, Jason. 2011. Flexicurity, employment protection and the jobs crisis. Work, Employment and Society 25: 642–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, Etta R. 2011. Teacher Preparation for Quality Teaching. Journal of Teacher Education 62: 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. 2019a. Encuesta de Condiciones de vida (ECV). Año 2018. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/ecv_2018.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- INE. 2019b. Contabilidad Regional de España. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, pp. 1–17. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/cre_2018_2.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- INE. 2019c. Abandono Educativo Temprano de la Población de 18 a 24 años por CCAA y periodo. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t00/ICV/dim4/l0/&file=41401.px (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Jencks, Christopher. 2002. Does inequality matter? Daedalus 131: 49–64. Available online: https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/daedalus/downloads/02_winter_daedalus_articles.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Jiménez, Roque, José María Cuenca López, and Mario Ferreras. 2010. Heritage education: Exploring the conceptions of teachers and administrators from the perspective of experimental and social science teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 1319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, David Lee. 2016. Teacher Education and Social Justice in the 21st Century: Two Contested Concepts. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social 5: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lavrenteva, Evgenia, and Lily Orland-Barak. 2015. The treatment of culture in the foreign language curriculum: An analysis of national curriculum documents. Journal of Curriculum Studies 47: 653–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías, Íñigo, and Susana Ruiz. 2017. Una Economía para el 99%. Barcelona: Oxfam Intermón, pp. 1–32. Available online: http://www.oxfamintermon.org/sites/default/files/documentos/files/Informe-Una-economia-para-99-espana-oxfam-intermon.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2020).

- Marco-Stiefel, Berta. 2004. Alfabetización científica: Un puente entre la ciencia escolar y las fronteras científicas. Cultura y Educación 16: 273–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez de la Plata, José Manuel. 2008. Concepciones de los alumnos de Magisterio de Educación Primaria sobre la pobreza: Una aplicación en un aula universitaria de los créditos ECTS. In Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Currículo Escolar y Formación del profesorado: La Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales en los Nuevos Planes de Estudio. Edited by Rosa María Ávila, Alcázar Cruz and María Consuelo Díez. Jaén: Asociación Universitaria del Profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, pp. 148–57. Available online: http://www.didactica-ciencias-sociales.org/publicaciones_archivos/2008-jaen-libro.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- Martin, Christopher. 2016. Education, justice, and discursive agency: Toward an educationally responsive discourse ethics. Educational Theory 66: 735–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, James H., and Sally Schumacher. 2014. Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry, 7th ed. Harlow: Pearson, pp. 1–545. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport. 2016. PISA 2015. Programa para la Evaluación Internacional de los Alumnos; Madrid: Secretaría General Técnica. Available online: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/inee/dam/jcr:e4224d22-f7ac-41ff-a0cf-876ee5d9114f/pisa2015preliminarok.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Ministry of the Presidency. 2006. Organic Law 2/2006, 3 May, of Education; Madrid: Boletín Oficial del Estado (núm. 106, de 4 de mayo de 2006), pp. 17158–207. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2006/05/04/pdfs/A17158-17207.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Ministry of the Presidency. 2013. Organic Law 8/2013, 9 December, for the Improvement of Educational Quality; Madrid: Boletín Oficial del Estado (núm. 295, de 10 de diciembre de 2013), pp. 97858–921. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2013/12/10/pdfs/BOE-A-2013-12886.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Ministry of the Presidency. 2015a. Royal Decree 1105/2014, 26 December, por el que se establece el currículo básico de la ESO y del Bachillerato; Madrid: Boletín Oficial del Estado (núm. 3, de 3 de enero de 2015), pp. 169–546. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2015/01/03/pdfs/BOE-A-2015-37.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Ministry of the Presidency. 2015b. Order ECD/65/2015, 21 January, por la que se describen las relaciones entre las competencias, los contenidos y los criterios de evaluación de la educación primaria, la educación secundaria obligatoria y el bachillerato; Madrid: Boletín Oficial del Estado (núm. 25, de 29 de enero de 2015), pp. 6986–7003. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2015/01/29/pdfs/BOE-A-2015-738.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- Molina, José Antonio, Óscar David Marcenaro, and Ana Martín. 2015. Financial literacy and educational systems in the OECD: A comparative analysis using PISA 2012 data. Revista de Educación 369: 80–103. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:97501459-3b5b-4fab-a223-f55332e7662c/04educacion-financiera-y-sistemas-educativos-en-la-ocde-un-analisis-comparativo-con-datos-pisa-2012-pdf.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Morin, Edgar. 1990. Introduction à la Pensée Complexe. Paris: ESF, pp. 1–158. [Google Scholar]

- Morón, María del Carmen. 2016. El paisaje en la Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria: Análisis de Libros de Texto y del Currículum Oficial, el Abordaje Patrimonial. Huelva: Universidad de Huelva. Available online: http://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/handle/10272/12708 (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Neckerman, Kathryn M., and Florence Torche. 2007. Inequality: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology 33: 335–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocete, Francisco, Reinaldo Sáez, Moisés Rodríguez Bayona, Ana Peramo, Nuno Inácio, and Daniel Abril. 2011. Direct chronometry (14C AMS) of the earliest copper metallurgy in the Guadalquivir Basin (Spain) during the Third millennium BC: First Regional Database. Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 3278–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2017. OECD Economic Surveys. Spain. March 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/Spain-2017-OECD-economic-survey-overview.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- OECD. 2018. OECD Economic Surveys. Spain. November 2018. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/economy/spain-economic-snapshot/ (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Oishi, Shigehiro, Selin Kesebir, and Ed Diener. 2011. Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science 22: 1095–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, José María, Pilar Azcárate, and Antonio Navarrete. 2007. Teaching Models in the Use of Analogies as a Resource in the Science Classroom. International Journal of Science Education 29: 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño, Jorge, Ana Isabel Ponce, and Francisca José Serrano. 2016. Causality in primary students’ historical explanations. Revista de Educación 371: 9–30. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:299cd086-3ac8-4ea3-be7a-d8b831b5d8fc/01ortunobilingue-pdf.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2019).

- Pathak, Saurav, and Etayankara Muralidharan. 2018. Economic Inequality and Social Entrepreneurship. Business & Society 57: 1150–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, Richard J. 1999. A Deafening Silence: History Textbooks and the Students Who Read Them. Review of Educational Research 69: 315–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, Margarita R. 2003. Etiología de la desigualdad de la mujer: Alternativas pedagógicas por el cambio social. Innovación Educativa 13: 179–94. Available online: https://minerva.usc.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10347/5051/pg_181-196_inneduc13.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 6 October 2019).

- Pinto, Helena, and Sebastián Molina. 2015. La educación patrimonial en los currículos de ciencias sociales en España y Portugal. Educatio Siglo XXI 33: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkewitz, Thomas S. 1998. Struggling for the Soul. The Politics of Schooling and the Construction of the Teacher. New York: Teachers College Press, pp. 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- Porlán, Rafael, Pilar Azcárate, Rosa Martín, José Martín, and Ana Rivero. 1996. Conocimiento profesional deseable y profesores innovadores: Fundamentos y principios formativos. Investigación en la Escuela 29: 23–38. Available online: https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/IE/article/view/8088/7147 (accessed on 5 December 2019).

- Postage, Nicholas. 1992. Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. London: Routledge Press, pp. 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, Joaquín, and Joan Santacana. 2011. Los contenidos en la enseñanza de la Historia. In Didáctica de la Geografía y la Historia. Edited by Joaquín Prats. Barcelona: Graó, pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Presidency Department. 2015a. Decree 86/2015, 25 June, por el que se Establece el Currículo de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y del Bachillerato en la Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia; Santiago de Compostela: Diario Oficial de Galicia (núm. 120, de 29 de junio de 2015), pp. 25434–7073. Available online: https://www.xunta.gal/dog/Publicados/2015/20150629/AnuncioG0164-260615-0002_es.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2019).

- Presidency Department. 2015b. Foral Decree 24/2015, 22 April, por el que se establece el currículo de las enseñanzas de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria en la Comunidad Foral de Navarra; Pamplona: Boletín Oficial de Navarra (núm. 127, de 2 de julio de 2015), pp. 1–149. Available online: http://www.navarra.es/appsext/DescargarFichero/default.aspx?CodigoCompleto=Portal@@@epub/BON/AEDUCACION/F1503360_Anexo.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2019).

- Presidency Department. 2016a. Decree 111/2016, 14 June, por el que se establece la ordenación y el currículo de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria en la Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía; Sevilla: Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (núm. 122, de 28 de junio de 2016), pp. 27–45. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2016/122/BOJA16-122-00019-11633-01_00094130.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Presidency Department. 2016b. Order 14 July 2016, por la que se desarrolla el currículo correspondiente a la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria en la Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía, se regulan determinados aspectos de la atención a la diversidad y se establece la ordenación de la evaluación del proceso de aprendizaje del alumnado; Sevilla: Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía (núm. 144, de 28 de julio de 2016), pp. 108–396. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja/2016/144/BOJA16-144-00289-13500-01_00095875.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Publications Office of the European Union. 2006. Recommendation 2006/962/EC, of 18 December 2006, of the European Parliament and of the Council on Key Competences, for Lifelone Learning. Official Journal of the European Union L394: 10–18. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32006H0962&from=EN (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Redman, Charles L. 1978. The Rise of Civilization: From Early Farmers to Urban Society in the Ancient Near East. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, pp. 1–367. [Google Scholar]

- Remund, David L. 2010. Financial Literacy Explicated: The Case for a Clearer Definition in an Increasingly Complex Economy. The Journal of Consumer Affairs 44: 276–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridge, Tess. 2007. Children and poverty across Europe—The challenge of developing child centred policies. ZSE: Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation 27: 28–42. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d477/d42539b26e4f59224c3d433bbf1e9a07b938.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Ridgeway, Cecilia L. 2014. Why Status Matters for Inequality. American Sociological Review 79: 1–16. Available online: https://www.asanet.org/sites/default/files/savvy/journals/ASR/Feb14ASRFeature.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2019). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Antonio, and Juan Antonio Tomás, eds. 2014. Crisis y Política Económica en España. Un Análisis de la Política Económica Actual. Pamplona: Thomson Reuters-Aranzadi, pp. 1–354. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni. 2008. La educación para la ciudadanía económica: Comprender para actuar. Íber. Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia 58: 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Siarova, Hanna, Dalivor Sternadel, and Eszter Szőnyi. 2019. Research for CULT Committee—Science and Scientific Literacy as an Educational Challenge. Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivesind, Kirsten, and Ian Westbury. 2016. State-based curriculum-maked, Part I. Journal of Curriculum Studies 48: 744–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Alex. 2016. Configurations of corruption: A cross-national cuantitative analysis of levels of perceived corruption. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 57: 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travé, Gabriel. 2006. Investigando las actividades económicas. Proyecto Curricular Investigando Nuestro Mundo (6–12). Sevilla: Díada, pp. 1–172. [Google Scholar]

- Travé, Gabriel, and Juan Delval. 2009. Análisis de la práctica de aula. El caso de las concepciones histórico-económicas del alumnado. Investigación en la Escuela 69: 5–18. Available online: https://revistascientificas.us.es/index.php/IE/article/view/7096/6260 (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- VanSledright, Bruce. 2008. Narratives of Nation-State, Historical Knowledge, and School History Education. Review of Research in Education 32: 109–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitt, Lois A., Carol Anderson, Jamie Kent, Deanna A. Lyter, Jurg K. Siegenthaler, and Jeremy Ward. 2000. Personal Finance and the Rush to Competence: Financial Literacy Education in the U.S. Middleburg: Institute for Socio-Financial Studies, pp. 1–234. Available online: https://www.isfs.org/documents-pdfs/rep-finliteracy.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2020).

- Westbury, Ian, Jessica Aspfors, Anna-Verena Fries, Sven-Erik Hansén, Frank Ohlhaver, Moritz Rosenmund, and Kirsten Sivesind. 2016. Organizing curriculum change: An introduction. Journal of Curriculum Studies 48: 729–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Richard, and Kate Pickett. 2010. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York: Bloomsbury Press, pp. 1–409. Available online: http://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/wp-content/uploads/The-Spirit-Level-Why-Greater-Equality-Makes-Societies-Stronger-Kate-Pickett-400p_1608193411.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Williamson, Claudia R., and Rachel L. Mathers. 2011. Economic freedom, culture, and growth. Public Choice 148: 313–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Michael. 2008. From Constructivism to Realism in the Sociology of the Curriculum. Review of Research in Education 32: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Legislation | |

|---|---|

| State | LOE (Ministry of the Presidency 2006) LOMCE (Ministry of the Presidency 2013) Royal Decree 1105/2014, 26 December (Ministry of the Presidency 2015a) Order ECD/65/2015, 21 January (Ministry of the Presidency 2015b) |

| Andalusia | Decree 111/2016, 14 June (Presidency Department 2016a) Order 14 July 2016 (Presidency Department 2016b) |

| Galicia | Decree 86/2015, 25 June (Presidency Department 2015a) |

| Navarre | Foral Decree 24/2015, 22 April (Presidency Department 2015b) |

| Andalusia | Galicia | Navarre | State | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita income, 2016 | €17,659 | €21,482 | €29,375 | €23,979 |

| Average income, 2017 | €9258 | €11,239 | €13,585 | €11,412 |

| Household income, 2017 | €11,942 | €14,240 | €18,150 | €15,186 |

| AROPE rate, 2017 | 38.2% | 23.0% | 12.6% | 26.1% |

| Poverty rate, 2017 | 32.0% | 18.8% | 8.9% | 21.5% |

| School dropout rate (18–24 years), 2018 | 21.9% | 14.3% | 11.4% | 17.9% |

| PISA report, 2015 | 473 points | 512 points | 512 points | 493 points |

| Keywords | References |

|---|---|

1.

| Cooke (2016) |

| 2.Justice | Martin (2016) |

3.

| Williamson and Mathers (2011) |

| 4.Welfare | Goerlich and Villar (2009) |

5.

| Vitt et al. (2000) |

| 6.Social inequality | Ridgeway (2014) |

7.

| Neckerman and Torche (2007) |

8.

| Ridge (2007) |

| 9.Exploitation | Fleurbaey (2014) |

10.

| Pathak and Muralidharan (2018) |

11.

| Bernal-Verdugo et al. (2013) |

12.

| Stevens (2016) |

13.

| Bieler and Morton (2014) |

| 14.Social justice | Keiser (2016) |

| 15.Happiness | Oishi et al. (2011) |

16.

| Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) |

| Variables | Indicators | Level | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| I.1. Know | Historical-cultural | I | Linear history and social inequality understood as natural and inherited from the past. |

| Evolution | II | Succession of varied and meticulously referred to socio-economic facts that have led, for example, to the existence of rich and poor. | |

| Holistic | III | Integrated knowledge of different subjects to enable us to achieve a more egalitarian society. | |

| I.2. Know how to do | Anecdotal | I | Procedures provided and guided by the teacher aimed at knowing social and economic features spatially and temporally. |

| Treatment | II | Elaboration of procedures with human interrelations of cause and effect. | |

| Comparison | III | Interpretation of procedures with a social criticism background to achieve collective improvements. | |

| I.3. Know how to be | Obedience | I | Respect and subordination to the established powers: political, economic, media… |

| Democracy | II | Predominance in the defense of economic freedom, private property, solidarity and peace for the maintenance of social order. | |

| Diversity | III | Commitments promoting the eradication of social conflicts arising from inequalities (economic, racial, national, physical, cultural, sexual…) and from harmful practices (corruption, influence peddling, cronyism, wire-pulling…) |

| Variables | Indicators | Level | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| II.1. Variety | None/Some | I | Lack or scarcity of key competencies for students that act as an incentive in the search for socio-economic balance. |

| Most | II | Abundance of competences that support personal fulfillment from an individualistic point of view. | |

| All | III | An abundance of competences to improve adult life in society, considered as an interconnected entity. | |

| II.2. Depth | Superficial | I | Descriptive mention of key competences without delving into their importance for the well-being of the social majority. |

| Functional | II | Incorporation of competences that favor detailed socio-economic information. | |

| Critical | III | Key competences that are transformative and aimed at achieving a more equitable future. | |

| II.3. Disciplinarity | Single-disciplinary | I | Competences do not interrelate with all subjects related to socio-economic issues. |

| Multidisciplinary | II | Key competences worked with in several areas of knowledge (Social Sciences, Humanities…) for the learning of the concept of inequality. | |

| Interdisciplinary | III | Systemic work on competences that trains students in an optimal human development model where the search for fair trade prevails. |

| Variables | Indicators | Level | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| III.1. Conceptual | Typological | I | Characteristics of socio-economic evolution treated with no more explanation than their detailed description. |

| Multiple | II | Analysis of economic, political, social, artistic, and religious aspects for the achievement of social welfare. | |

| Social organization | III | Evolution of social complexity and socio-economic inequalities from a diverse, variable and improvable prism with awareness, educational progress, and future achievements in a world with finite resources. | |

| III.2. Procedural | Visual | I | Basic (axes, summaries), scarce and geared to knowing and memorizing an immutable social reality of obedience. |

| Skills | II | Tables and diagrams, maps, images and videos, plots, etc. that battle poverty. | |

| Research | III | Very diverse, creative, reflexive, and with socially significant conclusions: the case of questionnaires/interviews, webquests, experimentation… | |

| III.3. Attitudinal | Hierarchization | I | Defense of justice and traditional, religious, and comprehensive values from the current world. |

| Tolerance | II | Effort, motivation, perseverance, and entrepreneurship, but without including possible social interventions of a structural nature. | |

| Past-Present-Future | III | Responsibility, critical judgment, education in values and even disobedience for the sake of happiness, social justice and the transformation of today’s consumer society. |

| Variables | Indicators | Level | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| IV.1. Teaching and learning | Unidirectional | I | Students’ interests and ideas are not taken into account; they listen to, study, and reproduce the contents taught. The teachers explain the past and present socio-economic organization and maintain the hierarchical order. |

| Bidirectional | II | Students can be spontaneous discoverers who find errors to be solved regarding socioeconomic issues. The teacher presents, directs, or acts as a leader and expert on the meaning of inequality. | |

| Significant | III | The students’ previous knowledge and socioeconomic concerns are considered; they are active and reconstruct their knowledge. Teachers are coordinators and researchers, proposing projects and educational innovations for a more egalitarian future. | |

| IV.2. Activities | Irreflexive | I | Preponderance of the conceptual and memory fields without meditations focused on treating inequality in a reflexive way. |

| Reflexive | II | Presence of activities, including students’ interests/ideas and attention to diversity, for the teaching of economic literacy and financial literacy. | |

| Solutions | III | Teachers put into practice sequences of activities by levels of complexity: from ascertaining the students’ previous knowledge and their social context to the formulation of new socio-economic practices pursuing greater socioeconomic, economic, or income equality. | |

| IV.3. Resources | Simple | I | Mastery of textbooks and explanations by teachers about uncritical elementary socioeconomic content. |

| Varied | II | Printed, audiovisual, Information and Communications Technology (ICT), the environment, and human resources tailored to understanding the features of the economic crisis and unemployment. | |

| Experimentation | III | Complementary and extracurricular activities where the students are the protagonists and perceive reality in the first person. Learning and Knowledge Technologies (LKT) for educational uses that benefit the fight against corruption and wire-pulling. |

| Variables | Indicators | Level | Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|

| V.1. Criteria | Memorization | I | Accumulated rote-learning of content without social background. |

| Interrelation | II | Interconnection of criteria with competences in the educational curriculum, both focused on aspects of inequality. | |

| Comprehension | III | Holism, past, present, and lived inequalities, and future reflections on our societies in order to overcome unequal trade between countries and to achieve greater economic redistribution. | |

| V.2. Standards | Homogeneity | I | Acquisition of conceptual content about social inequality, both past and present. |

| Diversity | II | Interest focused on the acquisition of skills of great importance for understanding the consequences of poverty and wealth, and social and economic imbalances. | |

| Complexity | III | The learning of concepts, procedures, attitudes and skills are interrelated to facilitate an in-depth analysis of the complex problem of exploitation throughout history and in the world of today and the future. | |

| V.3. Transversality | Non-existent | I | No relevant issues or elements are taken into consideration with a view to overcoming the socio-economic deprivation of a significant percentage of humanity. |

| Existent | II | Transversal lessons for the improvement of socially relevant issues are evaluated, but in a superficial way and without mentioning their explicit importance for the resolution of social and economic inequalities in the immediate environment. | |

| Problematic | III | The insertion of certain transversal elements—education in values, morality and citizenship, the consumer, the environment, entrepreneurship, responsibility for leisure, for health, equality between men and women, inclusion, microcredits and labor training…—is optimal for overcoming serious current problems deriving from socioeconomic dissymmetries: privileged–disadvantaged, hunger, begging, intolerance and hatred, drug addictions, delinquency, suicides, homicides, etc. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abril-López, D.; Morón-Monge, M.d.C.; Morón-Monge, H.; Cuenca-López, J.M. The Treatment of Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Spanish Curriculum of the Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO): An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Teaching. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060094

Abril-López D, Morón-Monge MdC, Morón-Monge H, Cuenca-López JM. The Treatment of Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Spanish Curriculum of the Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO): An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Teaching. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(6):94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060094

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbril-López, Daniel, María del Carmen Morón-Monge, Hortensia Morón-Monge, and José María Cuenca-López. 2020. "The Treatment of Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Spanish Curriculum of the Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO): An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Teaching" Social Sciences 9, no. 6: 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060094

APA StyleAbril-López, D., Morón-Monge, M. d. C., Morón-Monge, H., & Cuenca-López, J. M. (2020). The Treatment of Socioeconomic Inequalities in the Spanish Curriculum of the Compulsory Secondary Education (ESO): An Opportunity for Interdisciplinary Teaching. Social Sciences, 9(6), 94. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060094