Procedural Environmental Injustice in ‘Europe’s Greenest City’: A Case Study into the Felling of Sheffield’s Street Trees

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Woodman, spare that tree!

- Touch not a single bough!

- In youth it sheltered me,

- And I’ll protect it now.

- ‘T was my forefather’s hand

- That placed it near his cot,

- There woodman let it stand,

- Thy axe shall harm it not!

2. Procedural Environmental Justice

3. The Case in Focus: Sheffield and Its Street Trees

We are improving and maintaining 1180 miles of road, 2050 miles of pavement, 68,000 street lights, 36,000 highway trees, 28,000 street signs, 72,000 drainage gullies, 480 traffic signals, 18,000 items of street furniture, 2.9 million sqm of grass verges and over 600 bridges and highway structures’.

4. Methods

5. The Highway Tree Advisory Forums

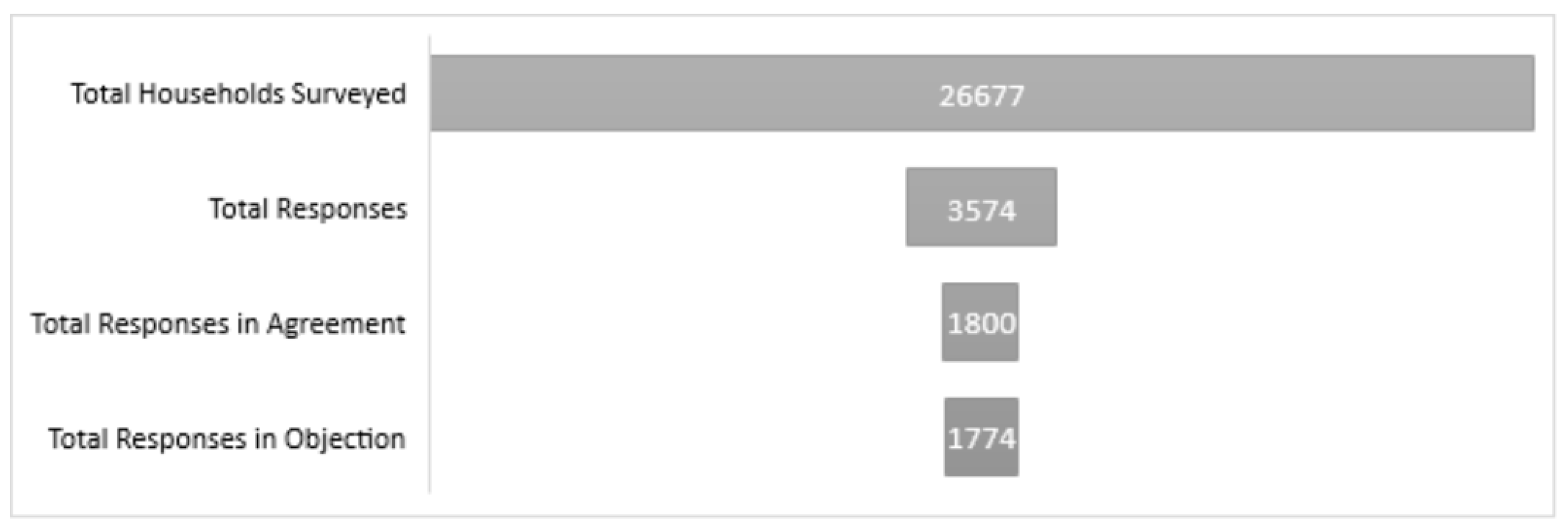

6. Independent Tree Panels and Household Surveys

…a sustainable replacement and management programme is required to prevent a catastrophic decline in street tree numbers in coming years…without the investment we are now delivering through Streets Ahead, we could be facing decades of under-investment, removal without replacement and a lack of proactive maintenance.

The tree…is a Huntingdon Elm (and not an English Elm), a notable and rare species, which we advise there is a strong arboricultural case to retain. The tree is causing some disruption to the pavement, and to the carriageway…We nevertheless believe that a combination of engineering solutions could be used to retain this tree…We recognise that this may incur additional costs. We therefore advise the Council to reconsider its plan for this tree with a view to retaining it.

7. The Arrests and Injunctions

This is a serious application. The council seeks to commit Sheffield citizens to prison for contempt...I would just like to be reassured that this application is brought on the instructions of democratically elected councillors. Do you have instructions from the leader of the council to make this application?(Males, quoted in Pidd 2018a)

I was near to three people who were being removed. ‘Forcibly removing’ doesn’t capture the reality of what they did: prise fingers off railings, bending thumbs back (one resident shouted that it felt as if they were breaking his fingers); grabbing and bending the arms of the two women who had linked arms; pushing and squashing a man who yelled he was being crushed; dragging an elderly resident by the arms. There were at least 10 security mobbing a group of 3 protesters, two of whom I think were pensioners. It was awful to see people being treated this way, and the police looking on, impassive to the pleas of the protesters that they intervene…(Holroyd, quoted in Saul 2018)

8. Discussion

9. Conclusions

- Would you hew me

- to the heartwood, cutter?

- Would you leave me open-hearted?

- …

- Do you hear these words I utter? I ask this of you –

- Have you heartwood, cutter?

- Have those who sent you?

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Advisory Panel on Policing Protests. 2018. Policing Sheffield’s Tree Protests. Available online: http://www.southyorkshire-pcc.gov.uk/Document-Library/Advisory-Panel-on-Policing-Protests/Policing-Sheffield-Trees-Protests.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Amey. 2018. Sheffield Streets Ahead—Highways Maintenance and Management. Available online: https://www.amey.co.uk/about-us/amey-in-your-area/north-east/sheffield-streets-ahead/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Arnstein, Sherry. 1969. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35: 216–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barkham, Patrick. 2016. A Dawn Raid, Protestors Silenced: Is This a War on Trees?’. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/21/dawn-raid-war-on-trees-sheffield (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Barkham, Patrick. 2017. Put a Price on Urban Trees—And Halt This Chainsaw Massacre. The Guardian. September 11. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/sep/11/price-urban-trees-chainsaw-chestnuts-london-elm-sheffield (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- BBC News. 2016. Dawn Tree Felling in Sheffield Sparks Outrage. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-38012189 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- BBC News. 2017. Sheffield Tree Protesters ‘Will Not Face Arrest’, Says PCC. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-39279897 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- BBC News. 2018a. Butterfly Temporarily Saves Threatened Sheffield Tree. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-42950230 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- BBC News. 2018b. UK’s Most Polluted Towns and Cities Revealed. BBC News. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-43964341 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Beatty, Christina, and Steve Fothergill. 2016. Jobs, Welfare and Austerity: How the Destruction of Industrial Britain Casts a Shadow over Present-Day Public Finances. Available online: https://www4.shu.ac.uk/research/cresr/sites/shu.ac.uk/files/cresr30th-jobs-welfare-austerity.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Berrone, Pascual, Andrea Fosfuri, and Liliana Gelabert. 2017. Does greenwashing pay off? Understanding the relationship between environmental actions and environmental legitimacy. Journal of Business Ethics 144: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, Kirsten, Andrea Kaltenbach, Aniko Szabo, Sandra Bogar, F. Javier Nieto, and Kristen Malecki. 2014. Exposure to Neighborhood Green Space and Mental Health: Evidence from the Survey of the Health of Wisconsin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11: 3453–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, Robert. 2013. Anti-Fracking Activists Arrested at West Sussex Drilling Site. The Guardian. July 26. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/jul/26/anti-fracking-activists-arrested-sussex (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Bostrom, Magnus. 2012. A Missing Pillar? Challenges in Theorizing and Practicing Social Sustainability: Introduction to the Special Issue. Sustainability 8: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, Andy. 2017. Sheffield Fears Tree-Felling PFI Fight will Cost Millions. Financial Times. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/e3641c8a-835e-11e7-a4ce-15b2513cb3ff (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Brack, Cris L. 2002. Pollution Mitigation and Carbon Sequestration by an Urban Forest. Environmental Pollution 116: S195–S200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisman, Avi. 2008. Crime-Environment Relationships and Environmental Justice. Seattle Journal for Social Justice 6: 727–817. [Google Scholar]

- Brisman, Avi. 2013. The Violence of Silence: Some Reflections on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making, and Access to Justice in Matters Concerning the Environment. Crime, Law and Social Change 59: 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisman, Avi. 2018. Representing the “Invisible Crime” of Climate Change in an age of Post-Truth. Theoretical Criminology 22: 468–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, Andy. 2016. Independent Tree Panel for Sheffield. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/managingtrees/Chelsea%20Road.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Burn, Chris. 2018a. Sheffield Council Forced to Reveal Target to Remove 17,500 Street Trees under PFI Deal. Yorkshire Post. March 10. Available online: https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/our-region/south-yorkshire/sheffield/sheffield-council-forced-to-reveal-target-to-remove-17-500-street-trees-under-pfi-deal-1-9056942 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Burn, Chris. 2018b. Sheffield Council Spends £400,000 on Legal Battles with Tree Campaigners. Yorkshire Post. September 3. Available online: https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/sheffield-council-spends-400-000-on-legal-battles-with-tree-campaigners-1-9332757 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Burn, Chris. 2018c. Sheffield Sheds ‘Pothole City’ Tag as Complaints Drop 60 Percent. Yorkshire Post. Available online: https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/transport/sheffield-sheds-pothole-city-tag-as-complaints-drop-60-per-cent-1-9510925 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Burn, Chris. 2018d. Police to Pay Thousands in Compensation to Sheffield Tree Campaigners over ‘Groundless’ Arrests. Yorkshire Post. December 29. Available online: https://www.yorkshirepost.co.uk/news/police-to-pay-thousands-in-compensation-to-sheffield-tree-campaigners-over-groundless-arrests-1-9502368 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Butterfly Conservation. 2015. The State of The UK’s Butterflies 2015. Available online: https://butterfly- conservation.org/files/soukb-2015.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Carrabine, Eamonn. 2018. Geographies of Landscape: Representation, Power and Meaning. Theoretical Criminology 22: 445–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, Severin. 2018. Scottish GPs to Begin Prescribing Rambling and Birdwatching. The Guardian. October 4. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/oct/05/scottish-gps-nhs-begin-prescribing-rambling-birdwatching (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Clarke, Lauren. 2015. Sheffield Trees: New Highway Tree Strategy Promised at Packed Meeting of Sheffield Forum. Sheffield Star. Available online: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/sheffield-trees-new-highway-tree-strategy-promised-at-packed-meeting-of-sheffield-forum-1-7375285 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Dalton, Ian. 2017. Sheffield Street Trees: A Report by Ian Dalton. Available online: http://sheffieldgreenparty.org.uk/issues/streets-ahead-the-battle-for-our-street-trees/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2019. Consultation on Protecting and Enhancing England’s Trees and Woodlands. Available online: https://consult.defra.gov.uk/forestry/protecting-trees-and-woodlands/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Donovan, Geoffrey, and David T. Butry. 2010. Trees in the City: Valuing Street Trees in Portland, Oregon. Landscape and Urban Planning 94: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, Ed, and John Beatty. 2018. Kinder Scout: The People’s Mountain. Sheffield: Vertebrate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Pamela, and Jean Shaoul. 2003. Controlling the PFI Process in Schools: A Case Study of the Pimlico Project. Policy and Politics 31: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott Consultancy. 2007. Sheffield City Highways Tree Survey 2006–2007. Available online: http://elliottconsultancy.com/sheffield-city-highways-tree-survey (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- English, Linda, and James Guthrie. 2003. Driving Privately Financed Projects in Australia: What Makes Them Tick? Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 16: 493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, Francisco, John E. Wagner, David J. Nowak, Carmen Luz De la Maza, Manuel Rodriguez, and Daniel E. Crane. 2008. Analyzing the Cost Effectiveness of Santiago, Chile’s Policy of Using Urban Forests to Improve Air Quality. Journal of Environmental Management 86: 148–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Yingling, Kirti Das, and Qian Chen. 2011. Neighborhood Green, Social Support, Physical Activity, and Stress: Assessing the Cumulative Impact. Health & Place 17: 1202–11. [Google Scholar]

- Forestry Commission. 2018. Dutch Elm Disease (Ophiostoma Novo-Ulmi). Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.uk/dutchelmdisease (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Fraser, Nancy. 1999. Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation. In Culture and Economy after the Cultural Turn. Edited by Larry Ray and Andrew Sayer. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Nancy. 2000. Rethinking Recognition: Overcoming Displacement and Reification in Cultural Politics. New Left Review 3: 107–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, Lee Ann. 2014. Five Stories of Accidental Ethnography: Turning Unplanned Moments in the Field into Data. Qualitative Research 15: 525–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellers, Joshua, and Chris Jeffords. 2018. Toward Environmental Democracy? Procedural Environmental Rights and Environmental Justice. Global Environmental Politics 18: 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Colleen, and Maureen Reed. 2017. Revealing Inadvertent Elitism in Stakeholder Models of Environmental Governance: Assessing Procedural Justice in Sustainability Organisations. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 60: 158–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyes, David Rodriguez, and Nigel South. 2017. The Injustices of Policing, Law and Multinational Monopolization in the Privatization of Natural Diversity: Cases from Colombia and Latin America. In Environmental Crime in Latin America. Edited by David Rodriguez Goyes, Hanneke Mol, Avi Brisman and Nigel South. London: Palgrave, pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, David. 2017. Doing Research in the Real World, 4th ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Maxine, Larissa Davies, Themis Kokolakakis, and David Barrett. 2014. Everything Grows Outside—Including Jobs and the Economy; Sheffield Sport Industry Research Centre, Sheffield Hallam University. Available online: http://www.welcometosheffield.co.uk/content/images/fromassets/100_7204_310816121610.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Halliday, Josh. 2017. Michael Gove Seeking Way to End ‘Bonkers’ Felling of Sheffield Trees. The Guardian. September 28. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/sep/28/michael-gove-seeking-way-to-end-bonkers-felling-of-sheffield-trees (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Heydon, James. 2018. Sensitising Green Criminology to Procedural Environmental Justice. International Journal of Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydon, James, and Matthew Hall. 2018. Written Evidence Submitted by Dr James Heydon and Professor Matthew Hall, University of Lincoln Centre for Environmental Law and Justice. Available online: http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/environmental-audit-committee/25-year-environment-plan/written/78900.html (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts. 2018. Private Finance Initiatives. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmpubacc/894/894.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Hunold, Christian, and Iris Marion Young. 1998. Justice, Democracy and Hazardous Siting. Political Studies 46: 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Peter, Rachel Banay, Jaime Hart, and Francine Laden. 2015. A Review of the Health Benefits of Greenness. Current Epidemiology Reports 2: 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joint Nature Conservation Committee. 2010. UK Priority Species Pages—Version 2. Available online: http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/_speciespages/2586.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Kirby, Dean. 2017. The Battle to Save Trees in Sheffield, Britain’s Greenest City. iNews. March 30. Available online: https://inews.co.uk/essentials/news/environment/battle-save-trees-sheffield-britains-greenest-city/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Kondo, Michelle, Jamie Fluehr, Thomas McKeon, and Charles Branas. 2018. Urban Green Space and its Impact on Human Health. Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurian, Lucie. 2004. Public Participation in Environmental Decision Making: Findings from Communities Facing Toxic Waste Cleanup. Journal of the American Planning Association 70: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Andrew, and Ravi Maheswaran. 2011. The Health Benefits of Urban Green Spaces: A Review of the Evidence. Journal of Public Health 33: 212–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Changfu, and Xiaoma Li. 2012. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Urban Forests in Shenyang, China. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11: 121–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Michael, Paul Stretesky, and Michael Long. 2015. Environmental Justice: A Criminological Perspective. Environmental Research Letters 10: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, Jolanda, Robert Verheij, Sjerp de Vries, Peter Spreeuwenberg, Francois Schellevis, and Peter Groenewegen. 2009. Morbidity is Related to a Green Living Environment. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 63: 967–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mangione, Thomas W. 1995. Mail Surveys: Improving the Quality. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- McClanahan, Bill, and Nigel South. 2020. ‘All Knowledge Begins with the Senses’: Towards a Sensory Criminology’. British Journal of Criminology 60: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, Gavin. 2016. Sheffield Labour Party Attacks Council’s “Sinister” Tree Felling Operation. Horticulture Weekly. Available online: https://www.hortweek.com/sheffield-labour-party-attacks-councils-sinister-tree-felling-operation/arboriculture/article/1417156 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Mirowski, Philip. 2013. Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A. 2017. Support for Sheffield Tree Felling as Council Releases Survey Data. The Star. March 23. Available online: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/support-for-sheffield-tree-felling-as-council-releases-survey-data-1-8455933 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Natali, Lorenzo. 2015. A Visual Approach for Green Criminology. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- National Audit Office. 2018a. Financial Sustainability of Local Authorities 2018. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Financial-sustainabilty-of-local-authorites-2018.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- National Audit Office. 2018b. PFI and PF2. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PFI-and-PF2.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Newberry, Susan, and June Pallot. 2003. Fiscal (Ir)responsibility: Privileging PPPs in New Zealand. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 16: 467–92. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, David J., and Daniel E. Crane. 2002. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Urban Trees in the USA. Environmental Pollution 116: 381–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, David J., Eric Greenfield, Robert Hoehn, and Elizabeth Lapoint. 2013. Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Trees in Urban and Community Areas of the United States. Environmental Pollution 178: 229–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Outdoor City. 2019. The Outdoor City, Sheffield. Available online: https://www.theoutdoorcity.co.uk/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Peace, L. 2017. Sheffield tree protesters will ‘no longer face arrest’. Sheffield Star. March 15. Available online: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/sheffield-tree-protesters-will-no-longer-face-arrest-1-8439143 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Phillips, Carl, and Ken Sexton. 1999. Science and Policy Implications of Defining Environmental Justice. Journal of Exposure Analysis and Environmental Epidemiology 9: 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pidd, Helen. 2018a. Sheffield Council Leader Backs Case against Tree Protestors, Court Told. The Guardian. June 5. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/jun/05/sheffield-council-leader-backs-case-against-tree-protesters-court-told (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Pidd, Helen. 2018b. Sheffield Tree Activists Held on False Grounds, Police Watchdog Says. The Guardian. August 31. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/aug/31/sheffield-tree-activists-held-arrested-false-grounds-police-watchdog-iopc (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Powell, John. 2017. When a Tree Is Not just a Tree…Who Speaks for Urban Trees? Countryside and Community Research Institute. Available online: http://www.ccri.ac.uk/urbantrees/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Pretty, Jules, Carly Wood, Rachel Bragg, and Jo Barton. 2013. Nature for rehabilitating offenders and facilitating therapeutic outcomes for youth at risk. In Routledge Handbook of Green Criminology. Edited by Nigel South and Avi Brisman. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh, Thomas, Robert MacKenzie, Duncan Whyatt, and Nicholas Hewitt. 2012. Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure for Improvement of Air Quality in Urban Street Canyons. Environmental Science and Technology 46: 7692–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandford, N. 2015. Sheffield Street Tree Massacre. Woodland Trust. Available online: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/blog/2015/09/sheffield-street-tree-massacre/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Saul, Jennifer. 2018. Lies, Violence and Spurious Arrests in Sheffield. Medium. January 21. Available online: https://medium.com/@jennifersaul/lies-violence-and-spurious-arrests-in-sheffield-4b8c47c0bb19 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Saxena, Gunjan. 2005. Relationships, Networks and the Learning Regions: Case Evidence from the Peak District National Park. Tourism Management 26: 277–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, David. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schrader-Frachette, Kristin. 2002. Environmental Justice: Creating Equality, Reclaiming Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scriven, Paul. 2018. 6th March 2018. Available online: https://twitter.com/paulscriven/status/971040472788553728?lang=en (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2012. Streets Ahead: Five Year Tree Management Strategy 2012–2017. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/streetsahead/Streets%20Ahead%205%20Year%20Tree%20Management%20Strategy.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2015. Meeting of Council, Wednesday 7 October 2015, 2.00 pm (Item 18.). Available online: http://democracy.sheffield.gov.uk/mgAi.aspx?ID=11455 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2016a. Independent Tree Panel for Sheffield Terms of Reference. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/managingtrees/Managing%20Trees%20Doc2%20Independent%20Tree%20Panel%20Terms%20of%20Reference.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2016b. ITP Advice 16.11.16. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/managingtrees/Managing%20Trees%20Doc35%20ITP%2021%20Rustlings%20Road%20220716.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2016c. Roadside Trees. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20170131122607/https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/in-your-area/report_request/trees.html (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2017a. Council Busts Further Myths on Its Street Tree Replacement Programme. Available online: https://sheffieldnewsroom.co.uk/news/treemythbusting2/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2017b. Council Decision on Tree Replacements—27.06.17. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/managingtrees/Council%20Decision%20on%20Tree%20Replacements%20-%20270617.xlsx (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2017c. Managing and Looking After Street Trees. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/home/roads-pavements/managing-street-trees.html (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2017d. Sheffield City Council 16 Point Plan for the Elm on Chelsea Road/Union Road and Report under S40 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities (NERC) Act (2006). Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/managingtrees/Elm%20Mitigation.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2017e. Streets Ahead Upgrade Work. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/streetsahead (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2018a. Household Survey Results. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/content/dam/sheffield/docs/roads-and-pavements/managingtrees/All%20Survey%20Results%20Final%20Copy.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2018b. Saving Lives: City Unites around Bold Action to Make Our Air Cleaner and Safer. Available online: https://sheffieldnewsroom.co.uk/news/saving-lives-city-unites-around-bold-action-to-make-our-air-cleaner-and-safer/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield City Council. 2018c. Sheffield’s Population. Available online: https://www.sheffield.gov.uk/home/your-city-council/population-in-sheffield.html (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield Star. 2015. Experts Slam Sheffield Council and Demand Pause on Felling. Sheffield Star. Available online: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/experts-slam-sheffield-council-and-demand-pause-on-tree-felling-1-7441179 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield Star. 2016. Secret Plan to Remove Rustlings Road Trees Made by Sheffield Council and Police One Month Before Raid. Sheffield Star. December 8. Available online: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/secret-plan-to-remove-rustlings-road-trees-made-by-sheffield-council-and-police-one-month-before-raid-1-8279010 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Sheffield Tree Action Groups. 2017. Independent Tree Panel Result Summary—Final. Available online: https://savesheffieldtrees.org.uk/2017/07/31/independent-tree-panel-result-summary-final/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Soares, Anna Luisa, Francisco Rego, Gregory McPherson, James Simpson, Paula Peper, and Qingfu Xiao. 2011. Benefits and Costs of Street Trees in Lisbon, Portugal. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 10: 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, Robert E. 2006. Multiple Case Study Analysis. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffberg, Gerrit, Margaretha Van Rooyen, Michael Van der Linde, and Hendrik Groeneveld. 2010. Carbon Sequestration Estimates of Indigenous Street Trees in the City of Tshwane, South Africa. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 9: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Streeck, Wolfgang. 2017. Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Stretesky, Paul, and Michael Hogan. 1998. Environmental Justice: An Analysis of Superfund Sites in Florida. Social Problems 45: 268–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohbach, Michael, and Dagmar Haase. 2012. Above-Ground Carbon Storage by Urban Trees in Leipzig, Germany: Analysis of Patterns in a European City. Landscape and Urban Planning 104: 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, Ruth. 2011. Top 10 Greenest UK Cities. Produced for: The Ecologist—Setting the Environmental Agenda Since 1970. Available online: http://www.theecologist.org/green_green_living/home/807176/top_10_greenest_uk_cities.html (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Tang, Yujia, Anping Chen, and Shuqing Zhao. 2016. Carbon Storage and Sequestration of Urban Street Trees in Beijing, China. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 4: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Mark, Benedict Wheeler, Mathew White, Theodoros Economou, and Nicholas Osborne. 2015. Research Note: Urban Street Tree Density and Antidepressant Prescription Rates—A Cross-Sectional Study in London, UK’. Landscape and Urban Planning 136: 174–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torr, G. 2017. Charges Dropped Against Sheffield Councillor and Eight Other Campaigners Arrested over City Tree-Felling’. Sheffield Star. March 2. Available online: https://www.thestar.co.uk/news/breaking-charges-dropped-against-sheffield-councillor-and-eight-other-campaigners-arrested-over-city-tree-felling-1-8418350 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Trade Union and Labour Relations Consolidation Act. 1992. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1992/52/section/241 (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Transportation Professional. 2012. Sheffield Streets Team Starts City’s Core Refurbishment. In Transportation Professional. Kent: Barrett Byrd. [Google Scholar]

- Tritter, Jonathan, and Alison McCallum. 2006. The Snakes and Ladders of User Involvement: Moving beyond Arnstein. Health Policy 76: 158–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vailshery, Lionel, Madhumitha Jaganmohan, and Harini Nagendra. 2013. Effect of Street Trees on Microclimate and Air Pollution in a Tropical City. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12: 408–15. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, Agnes, Jolanda E. Maas, Robert Verheij, and Peter Groenewegen. 2010. Green Space as a Buffer between Stressful Life Events and Health. Social Science & Medicine 70: 1203–10. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Gordon. 2012. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics. Oxon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Gregg, Susan Senecah, and Steven Daniels. 2006. From the Forest to the River: Citizens’ Views of Stakeholder Engagement. Human Ecology Review 13: 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Lawrence, James Aydelotte, and Jessica Miller. 2000. Putting More Public in Policy Analysis. Public Administration Review 60: 349–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Stephen. 2018. Chief Constable Responds to Lord Scriven Letter. Available online: https://www.southyorks.police.uk/find-out/news/2018/march-2018/chief-constable-responds-to-lord-scriven-letter/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Weinstock, Ana Mariel. 2017. A Decade of Social and Environmental Mobilization against Mega-Mining in Chubut, Argentinian Patagonia. In Environmental Crime in Latin America. Edited by David Rodriguez Goyes, Hanneke Mol, Avi Brisman and Nigel South. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- White, Rob. 2007. Green Criminology and the Pursuit of Social and Ecological Justice’. In Issues in Green Criminology: Confronting Harms against Environments, Humanity and Other Animals. Edited by Piers Beirne and Nigel South. Devon: Willan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- White, Matthew, Ian Alcock, Benedict Wheeler, and Michael Depledge. 2013. Would You be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data. Psychological Science 24: 920–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodland Trust. 2018. Elm, Huntingdon (Ulmus x Hollandica ‘Vegeta’). Available online: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/visiting-woods/trees-woods-and-wildlife/british-trees/common-non-native-trees/huntingdon-elm/ (accessed on 3 January 2019).

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heydon, J. Procedural Environmental Injustice in ‘Europe’s Greenest City’: A Case Study into the Felling of Sheffield’s Street Trees. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060100

Heydon J. Procedural Environmental Injustice in ‘Europe’s Greenest City’: A Case Study into the Felling of Sheffield’s Street Trees. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(6):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060100

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeydon, James. 2020. "Procedural Environmental Injustice in ‘Europe’s Greenest City’: A Case Study into the Felling of Sheffield’s Street Trees" Social Sciences 9, no. 6: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060100

APA StyleHeydon, J. (2020). Procedural Environmental Injustice in ‘Europe’s Greenest City’: A Case Study into the Felling of Sheffield’s Street Trees. Social Sciences, 9(6), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9060100