Global Citizenship and Analysis of Social Facts: Results of a Study with Pre-Service Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

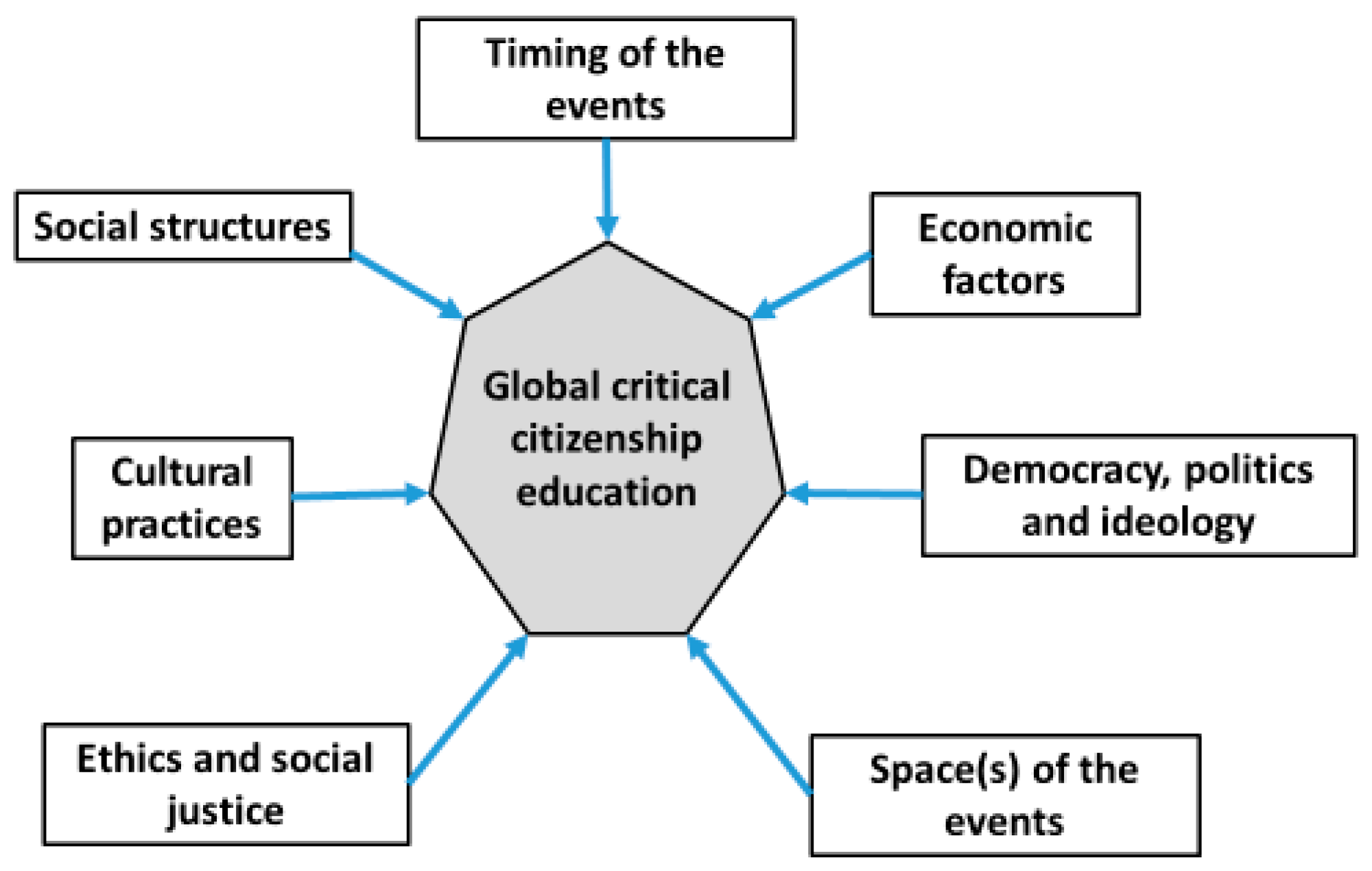

2. Global Citizenship Education

3. Teaching the Social Sciences and Global Citizenship Education

- −

- History enables students to learn about events in time with attributes like the simultaneity or contemporaneity of events.

- −

- Geography enables students to learn about space, territory and people’s interdependence with them.

- −

- Political science enables students to grasp the notions of power, governing systems and political organisation (both national and international).

- −

- Sociology enables students to learn about how societies are organised and work.

- −

- Anthropology enables students to study processes of cultural construction and identity in diverse contexts.

- −

- Economics enables students to gain basic knowledge of resources and wealth and their local and global distribution.

- −

- Ethical factors shape the frameworks that enable students to distinguish between what is just or unjust.

4. Research Methodology

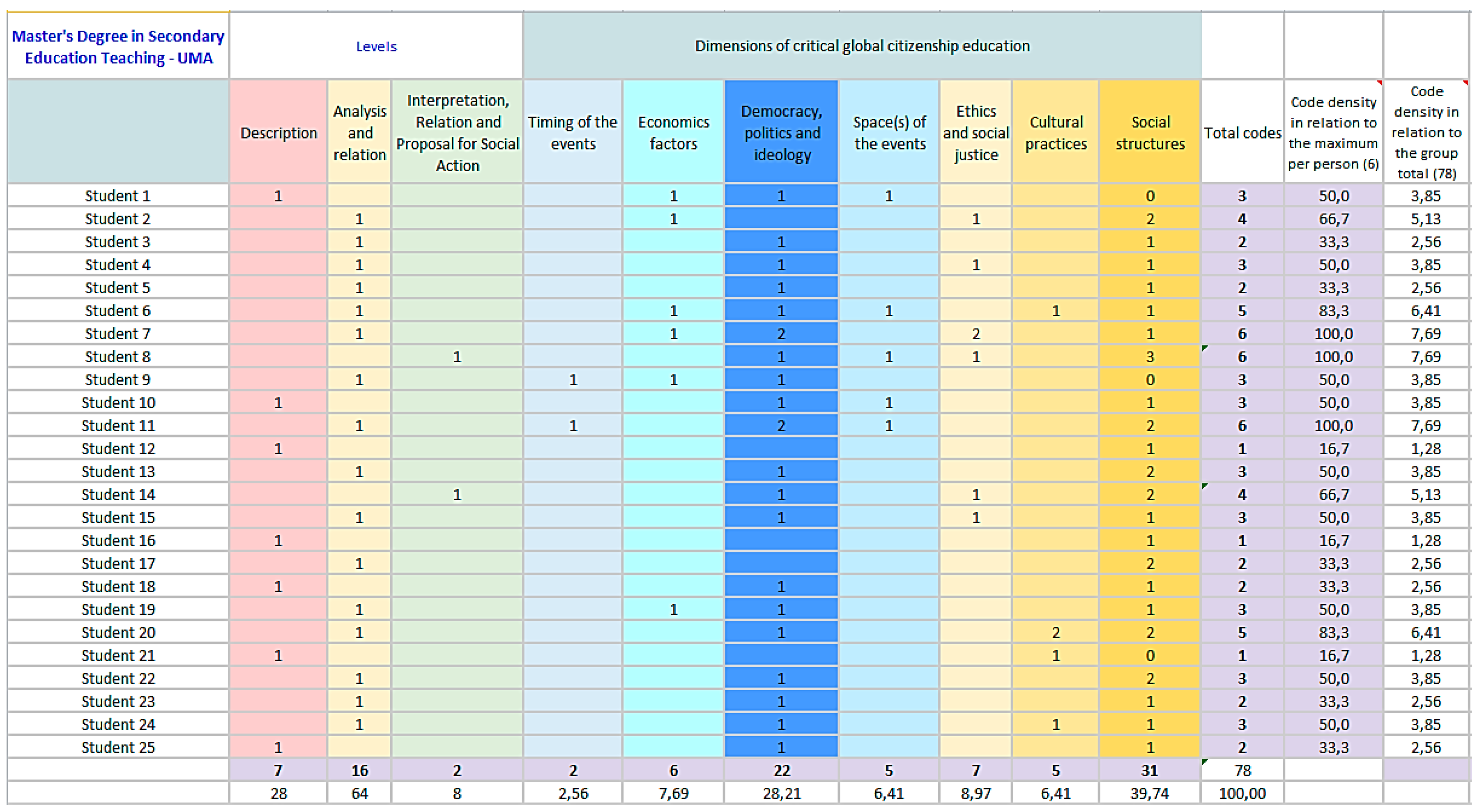

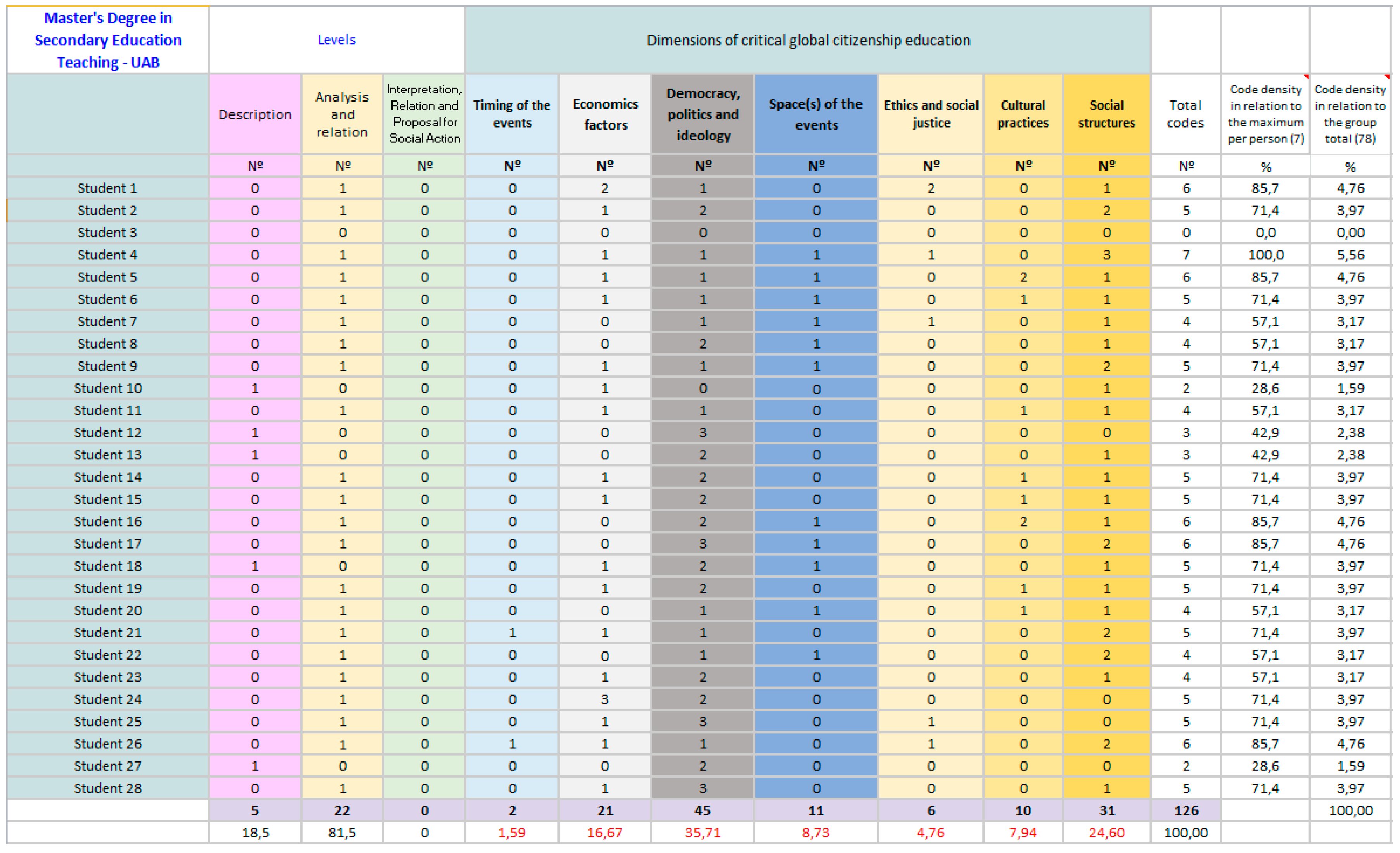

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andreotti, Vanessa. 2006. Soft versus critical global citizenship education. Policy & Practice—A Development 3: 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera, Carles, Neus González-Monfort, Ana María Hernández, Sandra Muzzi, Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, Joan Pagès, and Antoni Santiesteban. 2018. Invisibles y ciudadanía global en la formación inicial. In Buscando Formas de Enseñar: Investigar Para Innovar en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Edited by Esther López, Carmen García and María Sánchez. Valladolid: Universidadad de Valladolid—Asociación Universitaria de Profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, pp. 403–12. [Google Scholar]

- Argibay, Juan C. 2009. Muestra en investigación cuantitativa. Subjetividad y Procesos Cognitivos 13: 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, James, Ian Davies, and Caroles Hahn, eds. 2008. Sage Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Democracy. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, Benjamin R. 1984. Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, Lawrence. 2002. El Análisis de Contenido. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Broomley, Patricia. 2009. Cosmopolitanism in civic education: Exploring cross-national trends, 1970–2008. Current Issues in Comparative Education 12: 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Judy, Chris North, and Jessica FitzPatrick. 2019. Preservice teachers’ views of global citizenship and implications for global citizenship education. Globalisation, Societies and Education 17: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2005. La era de la Información Economía, Sociedad y Cultura. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Castellví, Jordi, Mariona Massip, and Joan Pagès. 2019. Emociones y pensamiento crítico en la era digital: un estudio con alumnado de formación inicial. Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales 5: 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Çolak, Kerem, Yücel Kabapınar, and Cemil Öztürk. 2019. Social Studies Courses Teachers’ Views on Global Citizenship and Global Citizenship Education. Ted Eğitim Ve Bilim 44: 335–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, Adela. 2003. Ciudadanos del mundo: Hacia una Teoría de la Ciudadanía. Madrid: Alianza. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Lynn. 2006. Global citizenship: abstraction or framework for action? Educational Review 58: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Ian, Mark Evans, and Alan Reid. 2005. Globalising citizenship education? A critique of ‘global education’ and ‘citizenship education.’. British Journal of Educational Studies 53: 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dei, George. 2008. Anti-racism education for global citizenship. In Global Citizenship Education: Philosophy, Theory and Pedagogy. Edited by Michael A. Peters, Alan Britton and Harry Blee. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, pp. 477–90. [Google Scholar]

- Delanty, Gerard. 1997. Models of Citizenship: Defining European Identity and Citizenship. Citizenship Studies 1: 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dill, Jeffrey. 2013. The Longings and Limits of Global Citizenship Education: the Moral Pedagogy of Schooling in a Cosmopolitan Age. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Faulks, Keith. 2000. Citizenship. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, Uwe. 2012. Introducción a la Investigación Cualitativa. Madrid: Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- González, Gustavo. 2013. La formación inicial del profesorado y la educación para la ciudadanía: representaciones sociales, diseño de clases y prácticas de enseñanza. Enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales 12: 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- González, Gustavo, and Antoni Santisteban. 2016. La formación ciudadana en la educación obligatoria en Colombia: entre la tradición y la transformación. Revista Educación & Educadores 19: 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Goren, Heela, and Miri Yemini. 2016. Global citizenship education in context: Teacher perceptions at an international school and a local Israeli school. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46: 832–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, Heela, and Miri Yemini. 2017a. The global citizenship education gap: Teacher perceptions of the relationship between global citizenship education and students’ socio-economic status. Teaching and Teacher Education 67: 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, Heela, and Miri Yemini. 2017b. Global citizenship education redefined—A systematic review of empirical studies on global citizenship education. International Journal of Educational Research 82: 170–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, Heela, Claire Maxwell, and Miri Yemini. 2019. Israeli teachers make sense of global citizenship education in a divided society-religion, marginalisation and economic globalisation. Comparative Education 55: 243–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Spain. 2015. Real Decreto 1105/2014, de 26 de Diciembre, por el que se Establece el Currículo Básico de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y del Bachillerato; Madrid: Boletín Oficial del Estado.

- Gun Chung, Bong, and Inyoung Park. 2016. A Review of the Differences between ESD and GCED in SDGs: Focusing on the Concepts of Global Citizenship Education. CICE Hiroshima University, Journal of International Cooperation in Education 18: 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, Roberto, Carlos Fernández, and Pilar Baptista. 2010. Metodología de la investigación. Mexico: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Edward R. 2013. Alternatives to a master’s degree as the new gold standard in teaching: A narrative inquiry of global citizenship teacher education in Japan and Canada. Journal of Education for Teaching 39: 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isin, Engin, and Bryan Turner, eds. 2002. Handbook of Citizenship Studies. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Janoski, Thomas, and Brian Gran. 2002. Political citizenship: Foundations of rights. In Handbook of Citizenship Studies. Edited by Engin Isin and Bryan Turner. New York: Sage, pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yeji. 2019. Global citizenship education in South Korea: ideologies, inequalities, and teacher voices. Globalisation, Societies and Education 17: 177–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopish, Michael. 2016. Preparing globally competent teacher candidates through cross-cultural experiential learning. Journal of Social Studies Education Research 7: 75–108. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 1990. Metodología de Análisis de Contenido. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Kymlicka, Will, and Wayne Norman. 1994. Return of the citizen: A survey of recent work on citizenship theory. Ethics 104: 352–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Marianne, and Michelle Searle. 2017. International service learning and critical global citizenship: A cross-case study of a Canadian teacher education alternative practicum. Teaching and Teacher Education 63: 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, Rhonda. 2013. Global Citizenship Instruction Through Active Participation: What Is Being Learned About Global Citizenship? The Educational Forum 77: 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Mattthew, A. Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Misco, Thomas. 2013. ‘We do not talk about these things’: The promises and challenges of reflective thinking and controversial issue discussions in a Chinese high school. Intercultural Education 24: 401–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, James, Tonya Huber, and Elizabeth Sanmiguel. 2018. The role of teacher educators in developing and disseminating global citizenship education strategies in and beyond US learning environments. Journal of Education for Teaching 44: 556–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín. 2017. Las mujeres en la enseñanza de la Historia y de las Ciencias Sociales: estudio de caso en formación inicial de maestros y maestras de Educación Primaria. Ph.D. dissertation, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/record/187752 (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín, and Alfredo Jiménez-Eguizábal. 2019. Project-Based Learning through Information and Communications Technology and the Curricular Inclusion of Social Problems Relevant to the Initial Training of Infant School Teachers. Sustainability 11: 6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín, and Rafael Olmos. 2018. Los problemas sociales relevantes o las cuestiones socialmente vivas en la enseñanza de las ciencias sociales. In Contribuciones de Joan Pagès al desarrollo de la didáctica de las ciencias sociales, la historia y la geografía en Iberoamérica. Edited by Miguel Ángel Jara and Antoni Santisteban. Cipolletti: Universidad de Comahue−UniversitatAutònoma de Barcelona, pp. 203–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín, and Joan Pagès. 2017. Literacidad crítica, invisibilidad social y género en la formación 651 del profesorado de Educación Primaria. REIDICS: Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de Las Ciencias Sociales 1: 102–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Sánchez, Delfín, and Joan Joan Pagès. 2020. The End-Purpose of Teaching History and the Curricular Inclusion of Social Problems from the Perspective of Primary Education Trainee Teachers. Social Sciences 9: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, Laura, and Paul Morris. 2013. Global Citizenship: A Typology for Distinguishing its Multiple Conceptions. British Journal of Educational Studies 61: 301–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagès, Joan, and Antoni Santisteban. 2014. Una mirada del pasado al futuro en la didáctica de las ciencias sociales. In Una Mirada al Pasado y un Proyecto de Futuro. Investigación e Innovación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Edited by Joan Pagès and Antoni Santisteban. Barcelona: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona—Asociación Universitaria de Profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, Soon. 2013. Global Citizenship Education. Goals and Challenges in the New Millennium. Seoul: UNESCO-APCEIU. [Google Scholar]

- Pak, Soon-Yong, and Moosung Lee. 2013. ‘Hit the ground running’: Delineating the problems and potentials in State-led Global Citizenship Education (GCE) through teacher practices in South Korea. British Journal of Educational Studies 66: 515–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, Italy, Aliza Segal, Adam Lefstein, and Assaf Meshulam. 2017. Teaching controversial issues in a fragile democracy: defusing deliberation in Israeli primary classrooms. Journal of Curriculum Studies 50: 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, Anatoli. 2009. A Forgotten Concept: Global Citizenship Education and State Social Studies Standards. The Journal of Social Studies Research 33: 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rauner, Mary. 1999. UNESCO as an organizational carrier of civic education information. Journal of Educational Development 19: 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reysen, Stephen, and Iva Katzarska-Miller. 2013. A model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology 48: 858–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sant, Edda. 2018. We, the non-global citizens: Reflections on the possibilities and challenges of democratic global citizenship education in higher education contexts. Citizenship Teaching & Learning 13: 273–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sant, Edda, and Gustavo González-Valencia. 2018. Global Citizenship Education in Latin America. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Citizenship and Education. Edited by Ian Davies, Li-Ching Ho, Dina Kiwan, Carla L. Peck, Andrew Peterson, Edda Sant and Yusef Waghid. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni. 2015. La formación del profesorado para hacer visible lo invisible. In Una enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales para el futuro: Recursos para trabajar la invisibilidad de personas, lugares y temáticas. Edited by Ana María Hernández, Carmen R. García and Juan L. de la Montaña. Cáceres: University of Extremadura—Asociación Universitaria de Profesorado de Ciencias Sociales, pp. 383–93. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni. 2019. La enseñanza de las Ciencias Sociales a partir de problemas sociales o temas controvertidos: estado de la cuestión y resultados de una investigación. El Futuro del Pasado 10: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, Antoni, and Neus González-Monfort. 2018. La mirada holística en la enseñanza de las ciencias sociales. In Contribuciones de Joan Pagès al desarrollo de la didáctica de las ciencias sociales, la historia y la geografía en Iberoamérica. Edited by Miguel Ángel Jara and Antoni Santisteban. Cipolletti: Universidad de Comahue−UniversitatAutònoma de Barcelona, pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban, Antoni, and Gustavo González-Valencia. 2013. Sociedad de la información, democracia y formación del profesorado ¿qué lugar debe ocupar el pensamiento crítico? In Medios de Comunicación y Pensamiento Crítico: Nuevas Formas de Interacción Social. Edited by Juan J. Díaz, Antoni Santisteban and Aurea Cascajero. Alcalá de Henares: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares—Asociación Universitaria de Profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, pp. 689, 761–70. [Google Scholar]

- Scheunpflug, Annette, and Barbara Asbrand. 2006. Global education and education for sustainability. Environmental Education Research 12: 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, Margrit. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Edited by Uwe Flick. London: Sage, pp. 170–83. [Google Scholar]

- Scribano, O. 2007. El proceso de Investigación Social Cualitativo. Buenos Aires: Prometeo Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Shultz, Lynette. 2007. Educating for global citizenship: Conflicting agendas and understandings. Alberta Journal of Educational Research 53: 248–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sklair, Leslie. 1999. Competing conceptions of globalization. Journal of World-Systems Research 2: 143–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, Joel. 2004. How Educational Ideologies are Shaping Global Society. Mahwah: LEA. [Google Scholar]

- Stromquist, Nelly. 2009. Theorizing Global Citizenship: Discourses, Challenges, and Implications for Education FlacsoAndes. Interamerican Journal of Education for Democracy 2: 6–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stromquist, Nelly, and Karen Monkman. 2014. Globalization and Education: Integration and Contestation Across Cultures. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Education. [Google Scholar]

- Szelényi, Katalin, and Robert Rhoads. 2007. Citizenship in a Global Context: The Perspectives of International Graduate Students in the United States. Comparative Education Review 51: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, Massimilliano, and Carla Inguaggiato. 2018. Teachers’ Education in GCE: Emerging Issues in a Comparative Perspective—UCL Discovery. Trento: Provincia Autonoma di Trento. [Google Scholar]

- Tarozzi, Massimiliano, and Benajmin Mallon. 2019. Educating teachers towards global citizenship: A comparative study in four European countries. London Review of Education 17: 112–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawil, Sobhi. 2013. Education for “global citizenship”: A framework for discussion. UNESCO Education Research and Foresight 7: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Carlos. 2009. Globalizations and Education: Collected Essays on Class, Race, Gender, and the State. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Carlos. 2015. Global Citizenship and Global Universities. The Age of Global Interdependence and Cosmopolitanism 50: 262–79. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Carlos. 2017. Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Critical Global Citizenship Education. New York: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tosar, Breogán, and Antoni Santisteban. 2016. Literacidad crítica para una ciudadanía global: una investigación Educación Primaria. In Deconstruir la Alteridad Desde la Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Educar para una Ciudadanía Global. Edited by Carmen García, Dolores Arroyo and Beatriz Andreu. Las Palmas: Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria—Asociación Universitaria de Profesorado de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, pp. 674–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tully, James. 2014. On Global Citizenship: James Tully in Dialogue. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2015. Global Citizenship Education: Topics and Learning Objectives. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2018. Preparing Teachers for Global Citizenship Education: A Template—UNESCO Digital Library. Bangkok: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, MiSeok, Jeong Kyounm Kim, and KiDuck Kim. 2017. A Study on Variables Related to Global Citizenship Teaching Efficacy of Secondary School Pre-service Teachers and In-service Teachers. Association of Global Studies Education 9: 77–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemini, Miri. 2017. Internationalization and Global Citizenship: Policy and Practice in Education. Tel Aviv: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Yemini, Miri, Felisa Tibbitts, and Heela Goren. 2019. Trends and caveats: Review of literature on global citizenship education in teacher training. Teaching and Teacher Education 77: 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| V. | ft | U1 | U2 | Total | U | W | z | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 28) | (n = 25) | (N = 53) | ||||||||||

| Literacy levels | V1 | 0 | 6 | 21.4% | 18 | 12% | 24 | 45.3% | 173.000 | 498.000 | −3.657 | 0.000 ** |

| 1 | 22 | 78.6% | 7 | 28% | 29 | 54.7% | ||||||

| V2 | 0 | 6 | 21.4% | 6 | 36% | 15 | 28.3% | 299.000 | 624.000 | −1.164 | 0.244 | |

| 1 | 22 | 78.6% | 16 | 64% | 38 | 71.1% | ||||||

| V3 | 0 | 28 | 100% | 23 | 92% | 51 | 96.2% | 322.000 | 728.000 | −1.511 | 0.131 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 8.0% | 2 | 3.8% | ||||||

| Dimensions of critical global citizenship education (CGCE) | V4 | 0 | 26 | 92.9% | 23 | 92% | 49 | 92.5% | 347.000 | 753.000 | −0.117 | 0.907 |

| 1 | 2 | 7.1% | 2 | 8.0% | 4 | 7.5% | ||||||

| V5 | 0 | 10 | 35.7% | 19 | 76% | 29 | 54.7% | 203.000 | 528.000 | −2.995 | 0.003 ** | |

| 1 | 16 | 57.1% | 6 | 24% | 22 | 41.5% | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.9% | ||||||

| 3 | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.9% | ||||||

| V6 | 0 | 2 | 7.1% | 5 | 20% | 7 | 13.2% | 177.000 | 502.000 | −3.406 | 0.001 ** | |

| 1 | 11 | 39.3% | 18 | 72% | 29 | 54.7% | ||||||

| 2 | 11 | 39.3% | 2 | 8.0% | 13 | 24.5% | ||||||

| 3 | 4 | 14.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 7.5% | ||||||

| V7 | 0 | 17 | 60.7% | 20 | 80% | 37 | 69.8% | 282.500 | 607.500 | −1.512 | 0.130 | |

| 1 | 11 | 39.3% | 5 | 20% | 16 | 30.2% | ||||||

| V8 | 0 | 23 | 82.1% | 19 | 76% | 42 | 79.2% | 329.000 | 735.000 | −0.530 | 0.596 | |

| 1 | 4 | 14.3% | 5 | 20% | 9 | 17% | ||||||

| 2 | 1 | 3.6% | 1 | 4.0% | 2 | 3.8% | ||||||

| V9 | 0 | 20 | 71.4% | 21 | 84% | 41 | 77.4% | 306.000 | 631.000 | −1.075 | 0.283 | |

| 1 | 6 | 21.4% | 3 | 12% | 9 | 17% | ||||||

| 2 | 2 | 7.1% | 1 | 4.0% | 3 | 5.7% | ||||||

| V10 | 0 | 5 | 17.9% | 3 | 12% | 8 | 15.1% | 315.000 | 721.000 | −0.697 | 0.486 | |

| 1 | 16 | 57.1% | 14 | 56% | 30 | 56.6% | ||||||

| 2 | 6 | 21.4% | 7 | 28% | 13 | 24.5% | ||||||

| 3 | 1 | 3.6% | 1 | 4.0% | 2 | 3.8% | ||||||

| Textual density | V11 | n1 | 5 | 17.9% | 18 | 72% | 23 | 43.4% | 157.000 | 482.000 | −3.958 | 0.000 ** |

| n2 | 22 | 78.6% | 7 | 28% | 29 | 54.7% | ||||||

| n3 | 1 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 1.9% | ||||||

| V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | V9 | V10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | 1 | |||||||||

| V2 | 0.102 | 1 | ||||||||

| V3 | −0.218 | −0.315 * | 1 | |||||||

| V4 | −0.027 | 0.180 | −0.057 | 1 | ||||||

| V5 | 0.310 * | 0.324 * | −0.178 | 0.152 | 1 | |||||

| V6 | 0.157 | 0.219 | −0.072 | 0.005 | 0.199 | 1 | ||||

| V7 | 0.268 | 0.048 | 0.085 | −0.032 | −0.041 | 0.099 | 1 | |||

| V8 | −0.093 | 0.122 | 0.367 ** | 0.023 | 0.136 | −0.065 | −0.044 | 1 | ||

| V9 | 0.214 | 0.244 | −0.106 | −0.154 | 0.101 | 0.023 | 0.151 | −0.274 * | 1 | |

| V10 | −0.054 | 0.297* | 0.315 * | 0.164 | −0.095 | −0.139 | 0.207 | 0.207 | −0.114 | 1 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Valencia, G.; Ballbé, M.; Ortega-Sánchez, D. Global Citizenship and Analysis of Social Facts: Results of a Study with Pre-Service Teachers. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050065

González-Valencia G, Ballbé M, Ortega-Sánchez D. Global Citizenship and Analysis of Social Facts: Results of a Study with Pre-Service Teachers. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(5):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050065

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Valencia, Gustavo, María Ballbé, and Delfín Ortega-Sánchez. 2020. "Global Citizenship and Analysis of Social Facts: Results of a Study with Pre-Service Teachers" Social Sciences 9, no. 5: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050065

APA StyleGonzález-Valencia, G., Ballbé, M., & Ortega-Sánchez, D. (2020). Global Citizenship and Analysis of Social Facts: Results of a Study with Pre-Service Teachers. Social Sciences, 9(5), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9050065