Abstract

Research on religion and its influence on work values is not frequent in Europe, where researchers do not usually consider this relation because of historical reasons. Nonetheless, the number of publications concerning religion’s contribution to organization management is systematically increasing. This study sheds light on the way Christian religions (Orthodox and Catholic) can shape value preferences of their believers as well as those who do not practice any religion but their families do. The study used a self-constructed value scale, which is a modification of M. Rokeach’s questionnaire survey. It differs from Rokeach’s Value Scale in respect to the quantity and quality of the proposed values and the assumption regarding the value hierarchy. A statistical analysis was carried out, enabling the indication of differences between the preference rates of 20 terminal and 20 instrumental values, depending on the denomination of the respondent and their family. Results of the study suggest that both religions influence the values preferences of their believers as well as non-believers coming from Catholic or Orthodox families. This impact was confirmed in the study both in relation to believers (through family) and non-believers (through family or social environment). Religion, therefore, proves to be an influential source of values preferences, which can be impactful also in the corporate surrounding.

1. Introduction

This research assumed that religion is one of the most important factors influencing the organization (Arruñada and Krapf 2019; Allchin 2015). Abundant evidence affirms that religious beliefs affect a wide range of behavioral outcomes and that religious activity can affect economic performance (Arruñada 2004; Sulkowski 2017; Ananthram and Christopher 2016). Past research has provided strong evidence of a link between religion and various work attitudes, especially with motivation, job satisfaction, and even organizational commitment (Parboteeah et al. 2010). It has also proved that religion has no negative effect on economic development (Noland 2003) and that both religious motivation and attitude toward nepotism affect the choice of conflict management styles, while demographic variables, such as age and gender, do not seem to have an effect (Caputo 2018). The results of past studies revealed that the application of Christian values as the base for operational financing decision mechanisms would create an operational financing form that not only managed honestly and independently, but also reflected the faith and the concern of others (Herdina et al. 2018). The influence of religion is noticed not only in organizational behavior but also in theoretical systems regarding management methods (Ignatowski et al. 2020). A major driving force of Drucker’s entire work is seen as the secularization of his religious beliefs. His practical suggestions for modern corporations are deeply influenced by the Christian faith (Meynhardt 2010).

Higher education students, especially management students, are to become the future members of the corporate top management. Exploring the relationship between religion and organizational culture would, therefore, be highly beneficial, since it determines the behavior of organization members. It is important to note that 72% of the world’s population, 4.6 billion people out of a total world population of 6.4 billion in 2004, were members and practitioners of the belief and value systems of the Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Hindu or Buddhist religions. As per Kriger and Seng (2005), with regards to the 2004 Encyclopedia Britannica Book of the Year, there were 4.353 billion members of differing religions in the world in mid-2003. There was also a total of 149 million atheists and 784 million non-religious people resulting in 82% of the world’s population believing in or following a religious or spiritual tradition. It can be assumed that a similar ratio of religious believers to non-believers exists for employees in organizations (Mazur 2015). Religion, as a set of beliefs and norms, has significant impact on the social culture. Hence, it also influences one’s values.

Rokeach (1973) thought that the total number of values respected by the unit is relatively small and amounts to several dozen. All people cherish the same values, though not to an equal degree. According to the author, there are two basic groups of values: terminal and instrumental, known also as intrinsic. To value is to have a positive attitude toward it and to prefer its existence. Value could be treated as an end which means it is terminal or intrinsic as, for example, human life or religion. Value could be also perceived as a means to achieve a more important end as money for many people. Instrumental and terminal values play a pivotal role in social, moral and economical motivations of human behavior (Lutz 1985). While constructing the scale of terminal values, he reviewed the literature on the subject, listing the names of the values encountered. He added the values given by thirty psychology students to his list, as well as his own. He also interviewed a representative sample of 100 adults from the city of Lansing, USA. Then, using certain criteria, he reduced the large set of value names obtained in this way (Brzozowski 1986). In constructing the scale of instrumental values, M. Rokeach used the list of 555 adjectives composed of personality traits assessed positively or negatively by N. H. Anderson (as per Brzozowski 1986). He then reduced the set using the same criteria as for the terminal values. In addition, he left features (values) that: (1) were rated only positively, (2) seemed to be the most important values of the American society, (3) were characteristic of representatives of various age groups, religious, political, men and women, people of different social status, (4) were important values in many cultures, (5) could be accepted without being accused of immodesty, vanity or boastfulness.

M. Rokeach’s method is relatively well known in Poland. Several studies have been conducted using this scale. Unfortunately, the method scale was translated for short-term use, shortened or extended, or used without definitions (Kość and Burek 1978).

Personal Characteristics of Participants as a Source of the Organizational Culture Value

An organization’s functioning is based on the activities of people who create it and enter into mutual relations. Throughout life, a human individual participates in a series of interactions. Human personality is created as a result of the interaction of such factors as human nature, biology and culture. As per Makin et al. (2000), “There may not be any formal rules to impose certain behaviors but people in the organization learn to comply with unwritten rules so quickly that certain behavior patterns become common in the organization and, moreover, serve as a sign that distinguishes them from other organizations, giving a clear identity and a specific aura”. However, new members of the organization also leave their mark on it by bringing their own life and professional experiences, views, needs and values. The impact of the religious culture on the characteristics of the organization’s participants can be seen through the values they bring. In psychological literature, the word “value” occurs in at least three basic meanings. Psychologists most often talk about subject value, object value and subjective value (Brzozowski 1986).

Subjective value, or utility, is a situational, variable feature of objects, states and events. Its intensity is subject to large fluctuations in short periods of time because it depends on one’s goals and current needs. The object value is a trait attributed to the subject by some attitude. Attitudes relate to things that have a positive or negative value for the individual. This type of value is not subject to rapid fluctuations because it does not depend directly on the current needs and goals of the individual. In addition, the subject of attitude has its relatively constant representation in human cognitive structures, which also stabilizes a value. The subject value is more a feature of the person rather than the world around them. It concerns the most important goals in human life or the most general ways to achieve these goals. M. Rokeach’s value test is used to measure values which, according to the accepted distinction, are called subject values. According to Rokeach (1973), value is an “enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end state of existence”. Additionally, the author further explains that values form a hierarchical system which is as ‘‘an enduring organization of beliefs concerning preferable modes of conduct or end-states of existence along a continuum of relative importance”. The location of beliefs in the system, their centrality, determines the degree of susceptibility to change. The more central the belief, the harder it is to change it. However, if it is changed, it entails significant repercussions in the entire cognitive system. It follows that values are difficult to reorganize; their change echoes in human attitudes and behavior, as evidenced by numerous data from experiments (Rokeach 1979).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Tools

The study used a self-constructed Value Scale of Czerniawska and Czerniawski (1996), which is a modification of M. Rokeach’s questionnaire survey. The Value Scale created by Czerniawska differs from Rokeach’s Value Scale in respect to the quantity and quality of the proposed values and the assumption regarding the value hierarchy. This means that respondents are not forced to rank values separately. Values perceived by them as equally important can be placed on one level. This reduces the likelihood of creating a fictitious value system. Moreover, it also allows to set the number of hierarchy levels that indicate the actual shapes of the value systems in respondents’ minds (the surveyed do not have to distribute a certain number of elements within a closed structure, which means that a high preference for one value does not entail a low preference for another value). Then a statistical analysis was carried out, enabling the indication of differences between the preference rates of 20 terminal and 20 instrumental values, depending on the denomination of the respondent and his family.

2.2. Variables, Indicators

In the study, a religious denomination stood for the independent variable, whereas the dependent one corresponded to terminal and instrumental value preferences. The indicator was the rank assigned to a given value by the examined person. The highest-valued value was ranked 1, the lowest-valued value was ranked 20. A possibility of scaling homogeneity was presumed, assuming that the highest level of homogeneity is when the respondent represents the same denomination as his family, whereas a lower level occurs when the respondent declaring his own denomination comes from a mixed family in which one of the parents followed a different religion form that declared, and the smallest level takes place when the respondent does not declare any religion and comes from a mixed family. The measure of similarity in the value preferences of the studied groups is a number of significant differences determined statistically.

2.3. Process of the Test and Test Sample Characteristics

The study involved 856 students of two Podlasie universities: Białystok University of Technology (Faculty of Management) and the University of Finance and Management in Białystok (Faculty of Management and Marketing and the Department of Spatial Management). In both universities, extramural and full-time students studying in recent years were examined. Among the respondents, there were significantly more women than men (587 women, 262 men, 7 people did not answer the question regarding their gender). In the group of respondents declaring themselves as Catholics, there were 475 women (71.1%) and 197 men (28.9%). Among the followers of the Orthodox religion, there were 129 people, of whom 90 were women (69.8%) and 39 were men (30.2%). The research sample structure is similar due to the gender. In turn, due to the variable age, the studied groups are different—Orthodox respondents are older than Catholics. The age range of the studied sample is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structure of respondents by age.

The concept of religion as a research category has been operationalized and ordered according to the declared religion. The religious structure of the studied population is shown in Table 2. The category of denomination was referred to the family and individual, which allowed to separate nine subcategories depending on the declared denomination and the denomination of the family. A detailed distribution of the denomination declared by respondents in relation to the denomination of the family is presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Religious structure of the studied population.

Table 3.

Religious structure of the studied population by family denomination.

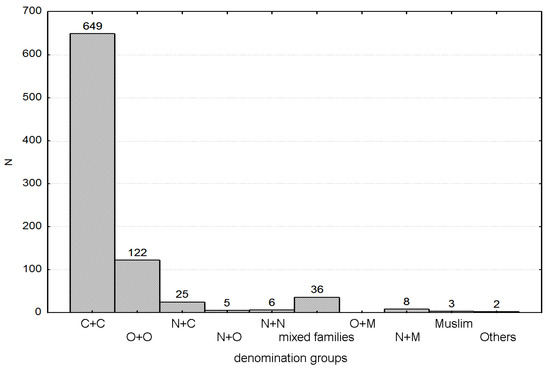

The largest group were those who described themselves as Roman Catholics from Catholic families (C + C)—there were 649 people in the study. The second largest group, comprising 122 respondents, were Orthodox Christians from Orthodox families (O + O). The third largest group were Catholic respondents from mixed families (C + M)—there were 29 of them. The fourth group were people who did not declare any denomination and came from Catholic families—there were 25 people (N + C). Other groups were represented in a small number: those who did not declare their religion and they came from Orthodox families, there were 5 respondents (N + O); those who did not declare their own religion or their family’s religion (N + N)—there were 6 people. There were 7 people of Orthodox denomination coming from mixed families (O + M). There were 8 people who did not declare their religion and came from mixed families (N + M). The study involved 3 followers of Islam from families representing the same denomination and two people representing a different denomination. The research sample based on the respondents’ denomination and the denomination of their families is depicted later in the text.

The factor differentiating the studied population is also the believers’ attitude to religion. Using this criterion, the following groups can be distinguished:

- (1)

- irregularly-practicing believers—46.1% of Catholics, 64.3% of Orthodox.

- (2)

- systematically-practicing believers—Catholics 32.9%, Orthodox Christians 13.2%.

- (3)

- non-practicing believers—Catholics 7.5%, Orthodox 12.4%.

An analysis of the ratio of respondents to believers to religion shows that there are more Orthodox believers in the group of irregular believers, and they also outweigh the Catholics in the group of non-practicing believers. In turn, those of the respondents who did not indicate any denomination more often came from families with Catholic parents. Table 4 presents the denomination of the family of such people.

Table 4.

People undeclaring their denomination vs. family.

A review of the information contained in the survey regarding the place of residence shows that the majority of respondents of both denominations live in Białystok. Respondents declaring themselves as Catholics reside in smaller cities of the Podlasie Voivodeship or in the countryside in the Podlasie Voivodeship. Every fifth of the surveyed followers of the Catholic religion lives outside the Podlasie Voivodeship. The surveyed Orthodox believers, apart from Białystok, most often live in towns or cities but also in the villages of Podlasie. A very small group lives in cities outside the Podlasie Voivodeship and no one lives in the countryside outside the Voivodeship. A detailed distribution of the residence of the studied group is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Place of residence of the surveyed students.

Almost half of the Catholics analyzed in the sample do not work, while the majority of Orthodox believers work full-time. A detailed distribution of the respondents in relation to their professional work is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Work performance by surveyed students.

A higher professional activity of the Orthodox respondents on the labor market may result from the age difference in this group compared to the Catholic respondents.

3. Results

3.1. Research Problem, Thesis and Hypotheses

The research was reviewed by the University independent ethics committee. The students who were the subject of the study were not evaluated or examined by the authors of the publication.

This research deals with cultural conditioning of value preferences. The thesis that religion is one of the cultural factors differentiating value preferences was verified by examining respondents further categorized: respondents of the Catholic and Orthodox denominations—coming from Catholic and Orthodox as well as mixed families; people who did not declare their own denomination, but indicated their parents’ denomination as Orthodox or Catholic; and respondents not following any religion—from unbelieving families. Respondents from other denominations were excluded from the study due to the low representation in the research group. The following hypotheses were formulated:

- (1)

- Value preferences of Orthodox respondents from Orthodox families and Catholic respondents from Catholic families expressed by significant differences are greater in relation to instrumental values rather than to terminal ones.

- (2)

- Value preferences of Orthodox respondents from mixed Orthodox-Catholic families and respondents of Catholic religion also from mixed families, expressed by statistical differences, do not reach a significant level either in relation to terminal or instrumental values.

- (3)

- There are more significant differences in terminal and instrumental values between Catholic believers from Catholic families and non-believers responding from Catholic families than between Orthodox believers from Orthodox families and non-believers from Orthodox families.

- (4)

- Social environment shapes terminal value preferences to a greater extent than instrumental value preferences in relation to respondents declaring themselves as non-believers, coming from a non-believer’s family.

3.2. Course of the Study and Characteristics of the Test Sample

Preference rates for 20 terminal and 20 instrumental values obtained by the means of the rank method were determined for each of the examined. Taking into account the hypotheses formulated in the study, a statistical analysis consisted of demonstrating the differences between the above-mentioned indicators depending on the independent variable, which was the denomination indicated in the homogeneity scale. Comparing the average rank values between individual groups in terms of their preferences, a post-hoc (multiple comparisons) NIR test (the least significant difference) was used.

As a result, Hypothesis 1 was adopted on the basis of the assumption that the Orthodox and Catholic religions in the first millennium of their existence belonged to the same Christian church, i.e., they were based on the same theological assumptions. This premise was the basis for the supposition that the followers of Orthodoxy and Catholicism—belonging to the common church for centuries—should be characterized by similar preferences of terminal values resulting from the basic assumptions of faith. On the other hand, the history of Orthodoxy indicates a closer relationship with the secular authority than that of the Catholic religion, which shapes specific procedures, hereby affecting the system of instrumental value preferences.

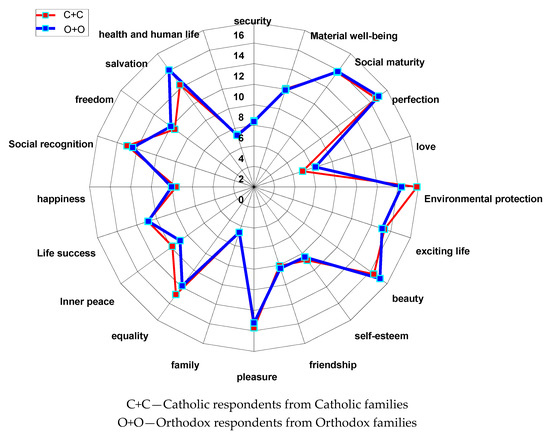

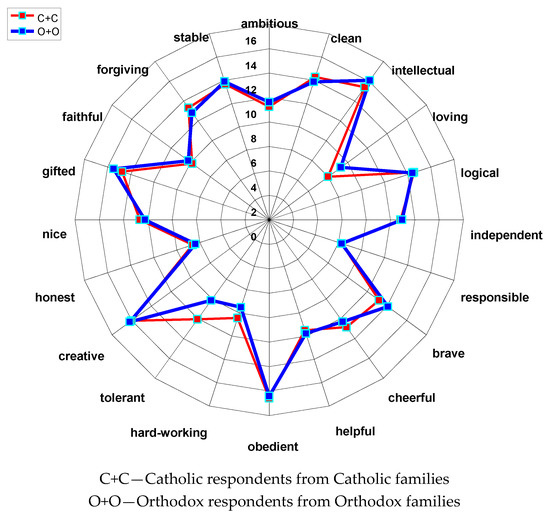

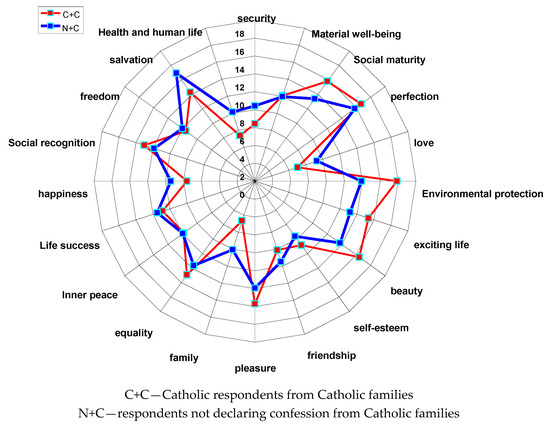

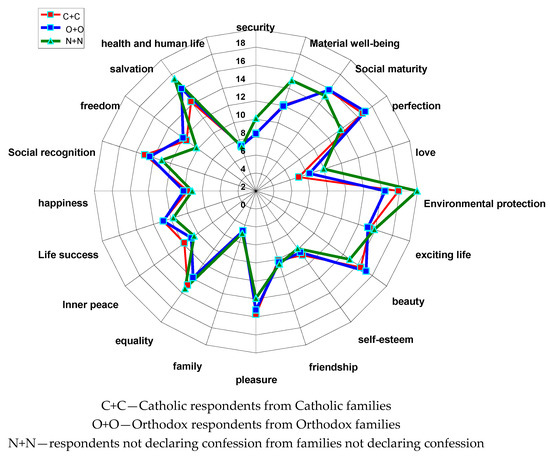

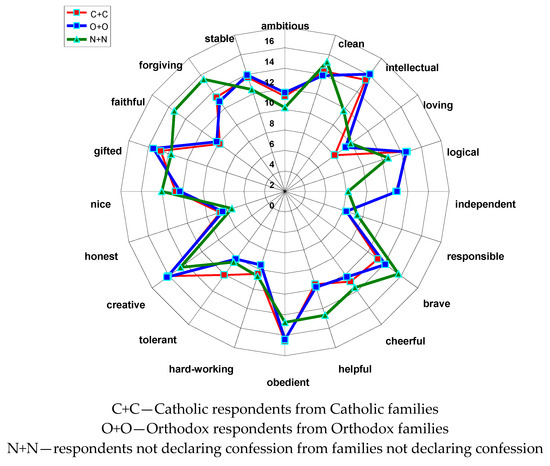

In terms of terminal values, the respondents of the two most-represented denominations—Catholics from Catholic families and Orthodox Christians from Orthodox families differ significantly in relation to the five terminal values: love, environmental protection, equality, internal peace and salvation. Love, equality and environmental protection belong to the group of interpersonal values, focusing on society, while inner peace and salvation are within the group of intrapersonal values, focusing on the individual. Therefore, the studied groups differ more in the preferences of interpersonal values that are socially oriented. In terms of instrumental values, significant differences concern values “loving” and “tolerant”, i.e., values from the moral group (“loving”) and concerning interpersonal relations (“tolerant”). Differences in terminal value preferences between the two denominational groups under analysis are shown in Figure 1 while the differences between these groups related to instrumental values are presented in Figure 2. The first hypothesis is rejected.

Figure 1.

A list of preferences of the final values of Catholic and Orthodox respondents representing the same denomination as their family. Source: own study based on research results.

Figure 2.

A list of preferences of instrumental values of Catholic and Orthodox respondents representing the same denomination as their family. Source: own study based on research results.

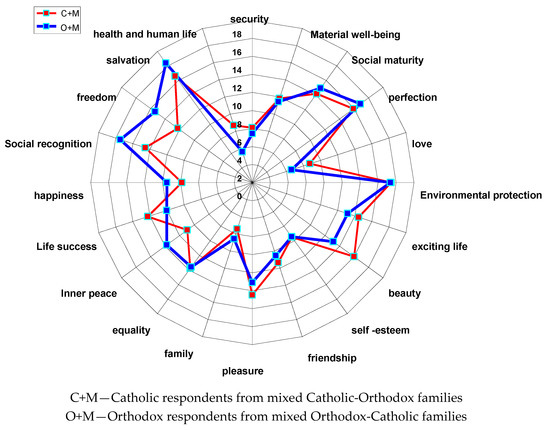

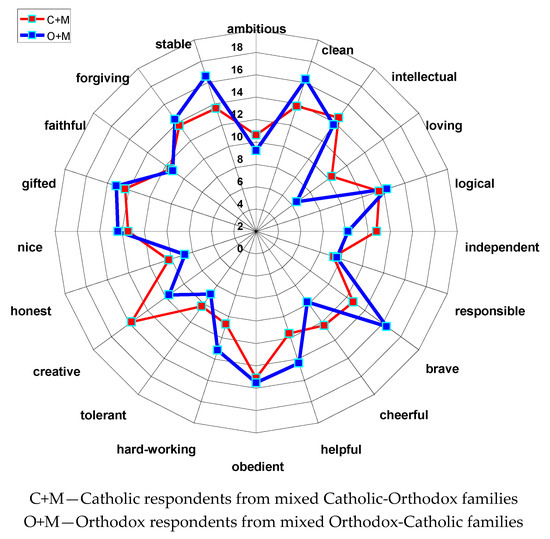

Hypothesis 2 was adopted on the basis of the assumption that the pursuit of conflict-free coexistence of two different religions is accompanied by mutual adjustment of value systems. Children from mixed families are equipped with a value system that is a compromise between the Catholic and Orthodox values, which allows for the conclusion that regardless of the final declaration of religious affiliation, their value systems will be similar.

The second hypothesis was verified positively because there were no significant differences regarding terminal and instrumental values between Orthodox and Catholic respondents from mixed families. Differences in terminal value preferences between Catholic and Orthodox respondents from mixed families are presented in Figure 3, while differences between these groups regarding instrumental values are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

List of preferences of the terminal values of Catholic and Orthodox respondents from mixed Catholic-Orthodox families. Source: own study based on research results.

Figure 4.

List of instrumental value preferences of Catholic and Orthodox respondents from mixed Catholic-Orthodox families. Source: own study based on research results.

Hypothesis 3 was adopted on the basis of the assumption that Orthodox believers value constancy and invariability relatively higher than Catholics which, in consequence, may result in a lower tendency to negate the value of the denominational community they come from.

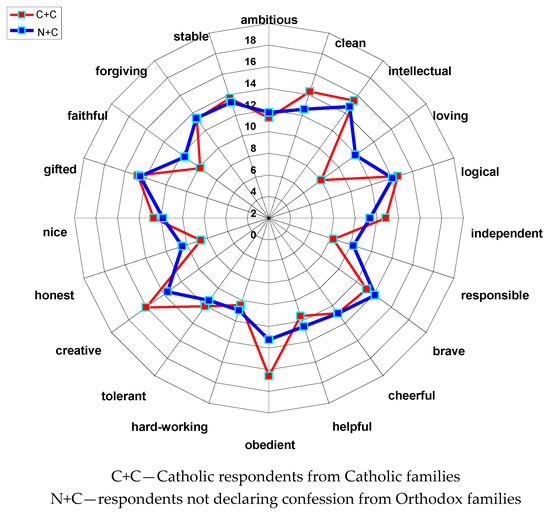

The third hypothesis has been positively verified. The significant differences in relation to the terminal values between non-believing respondents from Catholic families and Catholic respondents from Catholic families concerned the following values: security, social maturity, love, environmental protection, exciting life, beauty, family, happiness, salvation, health and human life. The differences in the group of interpersonal values that focus on social relations (security, social maturity, love, environmental protection) prevail, but there are also differences in the preferences of intrapersonal values (happiness and salvation). There are less significant differences in the sphere of instrumental values between non-believers from the Catholic families and Catholic respondents from the Catholic families than differences in the preferences of terminal values appropriate for these groups. Both groups rank significantly the following instrumental values: loving, responsible, obedient, creative. The first three represent a group of moral values, the fourth value includes a group of competence, cognitive and intellectual values, which are more individual than social, including such qualities as: ambitious, independent, brave or gifted. Differences in terminal value preferences between Catholic respondents and respondents not declaring a denomination from Catholic families are presented in Figure 5, while differences between these groups related to instrumental values are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Statement of the terminal value preferences of Catholic respondents and respondents not declaring religion from Catholic families. Source: own study based on research results.

Figure 6.

A list of preferences for instrumental values of Catholic respondents and respondents who do not declare denominations from Catholic families. Source: own study based on research results.

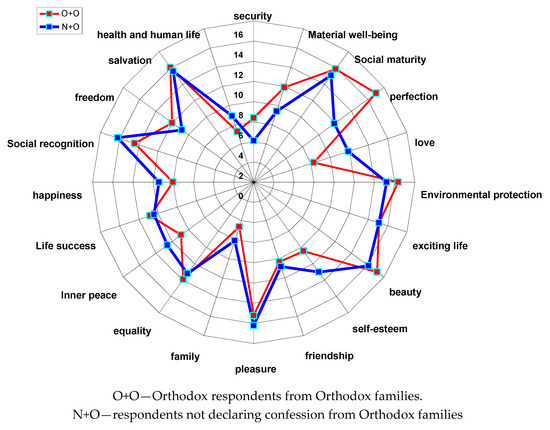

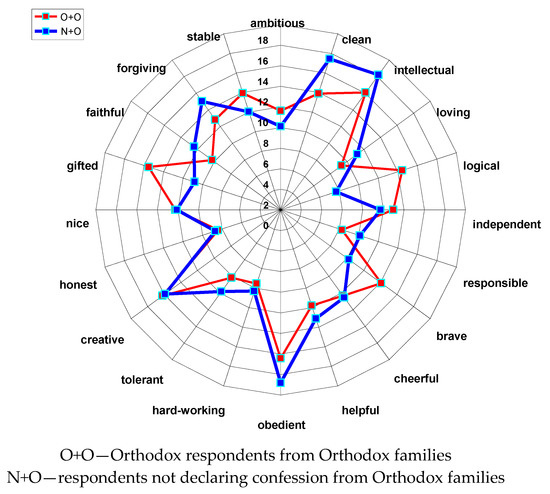

There are significantly fewer differences in relation to terminal values between non-believing respondents from Orthodox families and Orthodox respondents from Orthodox families than in the previously compared groups; there is only one significant difference regarding the value of perfection, which belongs to the group of intrapersonal values. Important differences in the sphere of instrumental values between non-believing respondents from Orthodox families and Orthodox respondents from Orthodox families were noted in the following values: logical and gifted. Both of these values belong to the group of individual competence values. Differences in the terminal values preferences between respondents of the Orthodox denomination and those not declaring denominations from Orthodox families are presented in Figure 7, while the differences between these groups related to instrumental values are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 7.

A list of terminal value preferences of Orthodox respondents and respondents not declaring any religion from Orthodox families. Source: own study based on research results.

Figure 8.

Comparison of instrumental value preferences of Orthodox respondents and respondents not declaring their denomination from Orthodox families. Source: own study based on research results.

The nature of the values for which significant differences were noted between unbelieving respondents from Catholic families and non-believing respondents from Orthodox families allows to draw the conclusion that the former are inclined to make changes in the value preferences in the sphere of social relations, while the latter are expected to do that in the personal sphere.

The third hypothesis is positively verified, which allows us to conclude that Orthodox believers are characterized by a strong reluctance to change, treating traditions as an unchanging value. On the other hand, Catholics treat the category of change as a positive trait leading to development.

Hypothesis 4 was formed on the belief that non-believers, while creating their system of ultimate values, base themselves on the terminal value preferences characteristic for religious systems and their followers. At the same time, they show a desire to detach themselves from the believers’ behavior, which is manifested by their change of instrumental value preferences.

There were no significant differences in terms of terminal values between non-believing respondents from non-believing families and Catholic respondents coming from Catholic families and respondents of the Orthodox religion coming from Orthodox families. However, there were two significant differences in relation to instrumental values: independent and brave (both of a competence nature). The differences in the terminal value preferences between respondents of the Catholic and Orthodox denominations and not declaring denominations are shown in Figure 9, while the differences between these groups related to instrumental values are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

A list of terminal value preferences of Catholic and Orthodox respondents who do not declare any religion. Source: own study based on research results.

Figure 10.

A list of preferences for instrumental values of Catholic and Orthodox respondents who do not declare religion. Source: own study based on research results.

The fourth hypothesis is confirmed because in relation to terminal values no significant differences were found in the value preferences of the compared groups and, at the same time, the existence of two differences in the preferences of instrumental values was pointed out. This confirms the impact of the entire social environment, including, to a large extent, Catholics and Orthodox Christians, on the preference system of terminal values of the surveyed non-believers. In turn, the desire to deviate from certain social behaviors is associated with the negation of certain instrumental values underlying these patterns of behavior. This proves the tendency of non-believing respondents to depart from certain values in practical activities, and not in the sphere of universal axiology.

Presented below is the denomination of the research respondents and their families. As shown in Figure 11, vast majority of the respondents were of Catholic denomination and came from Catholic families. The second most numerous group consisted of respondents of Orthodox denomination coming from Orthodox families. Significantly less represented were the groups coming from mixed families or non-believers.

Figure 11.

Denomination of respondents and their families. Source: own study based on research results.

The verification of the hypotheses put forward in the study makes it possible to positively validate the thesis that religion is one of the important cultural factors differentiating the value preferences of people remaining in the circle of its influence. In the process of the departure from the religious homogeneity in relation to Catholicism and the Eastern Orthodox Church, one can notice a lack of statistically significant differences in the preferences of terminal and instrumental values. Noteworthy is also the fact that the value preferences of the people who do not declare a religion converge with the preferences of the value of believers, which may indicate the impact of the cultural and religious environment on the value system of people who are not declared religiously. A departure from religion entails relatively bigger changes in the preferences of terminal and instrumental values in the group of respondents coming from Catholic families rather than those of Orthodox origin.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The first hypothesis is rejected. On this basis, it can be concluded that Catholic respondents from Catholic families and Orthodox respondents from Orthodox families are characterized by smaller differences in the perception of instrumental values rather than terminal values. Smaller differences in the perception of instrumental values can be explained by centuries of living in the same area and resulting in the need for cooperation, which contributed to the likeness of the modes of action and the values behind them. A relatively larger number of differences significant in the preferences of terminal values may be associated with the invariability of the theological principles underlying the teaching of both churches.

Hypothesis 2 was adopted on the basis of the assumption that the pursuit of conflict-free coexistence of two different religions is accompanied by mutual adjustment of value systems. Children from mixed families are equipped with a value system that is a compromise between the Catholic and Orthodox values, which allows us to conclude that regardless of the final declaration of religious affiliation, their value systems will be similar.

The third hypothesis is positively verified, which allows us to conclude that Orthodox believers are characterized by a strong reluctance to change, treating traditions as an unchanging value. On the other hand, Catholics treat the category of change as a positive trait leading to development.

The fourth hypothesis is confirmed because in relation to terminal values no significant differences were found in the value preferences of the compared groups and, at the same time, the existence of two differences in the preferences of instrumental values was pointed out. This confirms the impact of the entire social environment, including, to a large extent, Catholics and Orthodox Christians, on the preference system of terminal values of the surveyed non-believers. In turn, the desire to deviate from certain social behaviors is associated with the negation of certain instrumental values underlying these patterns of behavior. This proves the tendency of non-believing respondents to depart from certain values in practical activities, and not in the sphere of universal axiology.

There are several limitations of the research. Sampling process is based on convenient sample which means that it is not fully representative. The results are also limited to a group of college students limiting the possibilities to draw more generalized conclusions from research. The perspective of the research should go into international comparative research based on representative samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing, primary draft preparation, B.M.; literature review, writing and editing, Ł.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Social Sciences in Łódź, Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allchin, Douglas. 2015. Evolution of Moral Systems. In Basics in Human Evolution. Edited by Michael Muehlenbein. London: Academic Press, pp. 505–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthram, Subramaniam, and Chan Christopher. 2016. Religiosity, spirituality and ethical decision-making: Perspectives from executives in Indian multinational enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 33: 843–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruñada, Benito. 2004. The Economic Effects of Christian Moralities. Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona. 2004. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/eea5/2c1f54ef6f48acf720ce05a2ce64ec008bc4.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Arruñada, Benito, and Matthias Krapf. 2019. Religion and the European Union. In Advances in the Economics of Religion. Edited by Sriya Iyer, Jared Rubin and Jean-Paul Carvalho. 158 vols. IEA Series; Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowski, Piotr. 1986. Polska wersja testu wartości Rokeacha i jej teoretyczne podstawy. Przegląd Psychologiczny XXIX: 527–40. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, Andrea. 2018. Religious motivation, nepotism and conflict management in Jordan. International Journal of Conflict Management 29: 146–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniawska, Mirosława, and Jan Czerniawski. 1996. Rola zawodowa a system wartości. Test 4: 133–39. [Google Scholar]

- Herdina, Ajeng M., Atim Djazuli, and Kusuma Ratnawati. 2018. Christian values in operational financing decisions. Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen 16: 664–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatowski, Grzegorz, Łukasz Sułkowski, and Bartłomiej Stopczyński. 2020. The Perception of Organisational Nepotism Depending on the Membership in Selected Christian Churches. Religions 11: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kość, Zbigniew, and Andrzej Burek. 1978. Badania nad związkiem między cenieniem wartości a przestępczością a oszukiwaniem. In the I Krajowa Konferencja Problemów Profilaktyki społecznej i Resocjalizacj. Warszawa: IPSIR. [Google Scholar]

- Kriger, Mark, and Yvonne Seng. 2005. Leadership with inner meaning: A contingency theory of leadership based on the worldviews of five religions. The Leadership Quarterly 16: 771–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, Mark A. 1985. Pragmatism, instrumental value theory and social economics. Review of Social Economy 43: 140–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, Peter, Cary Cooper, and Charles Cox. 2000. Organizacje a kontrakt psychologiczny. Zarządzanie ludźmi w pracy. Warszawa: PWN, pp. 233–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, Barbara. 2015. Basic Assumptions of Organizational Culture in Religiously Diverse Environments. International Journal of Contemporary Management 14: 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- Meynhardt, Timo. 2010. The practical wisdom of Peter Drucker: Roots in the Christian tradition. Journal of Management Development 29: 616–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, Marcus. 2003. Religion, Culture, and Economic Performance. Institute for International Economics Working Paper 03-8. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=472484 (accessed on 15 December 2019).

- Parboteeah, Praveen K., Youngsun Paik, and John Cullen. 2010. Religious Groups and Work Values: A Focus on Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, and Islam. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 9: 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1979. Value theory and communication research: Review and commentary. In Communication Yearbook III. Piscataway: Transaction Books, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski, Lukasz. 2017. Social capital, trust and intercultural interactions. Intercultural Interactions in the Multicultural Workplace. In Intercultural Interactions in the Multicultural Workplace. Contributions to Management Science. Edited by Rozkwitalska Małgorzata, Sułkowski Łukasz and Slawomir Magala. Cham: Springer, pp. 155–71. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).