Traditional Male Role Norms and Sexual Prejudice in Sport Organizations: A Focus on Italian Sport Directors and Coaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Traditional Gender Role Expectations in Sport Contexts

1.2. Sexual Prejudice in Sport

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sexual Prejudice in Sport

2.2.2. Male Role Norms

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Mean Scores Differences in Sexual Prejudice Dimensions

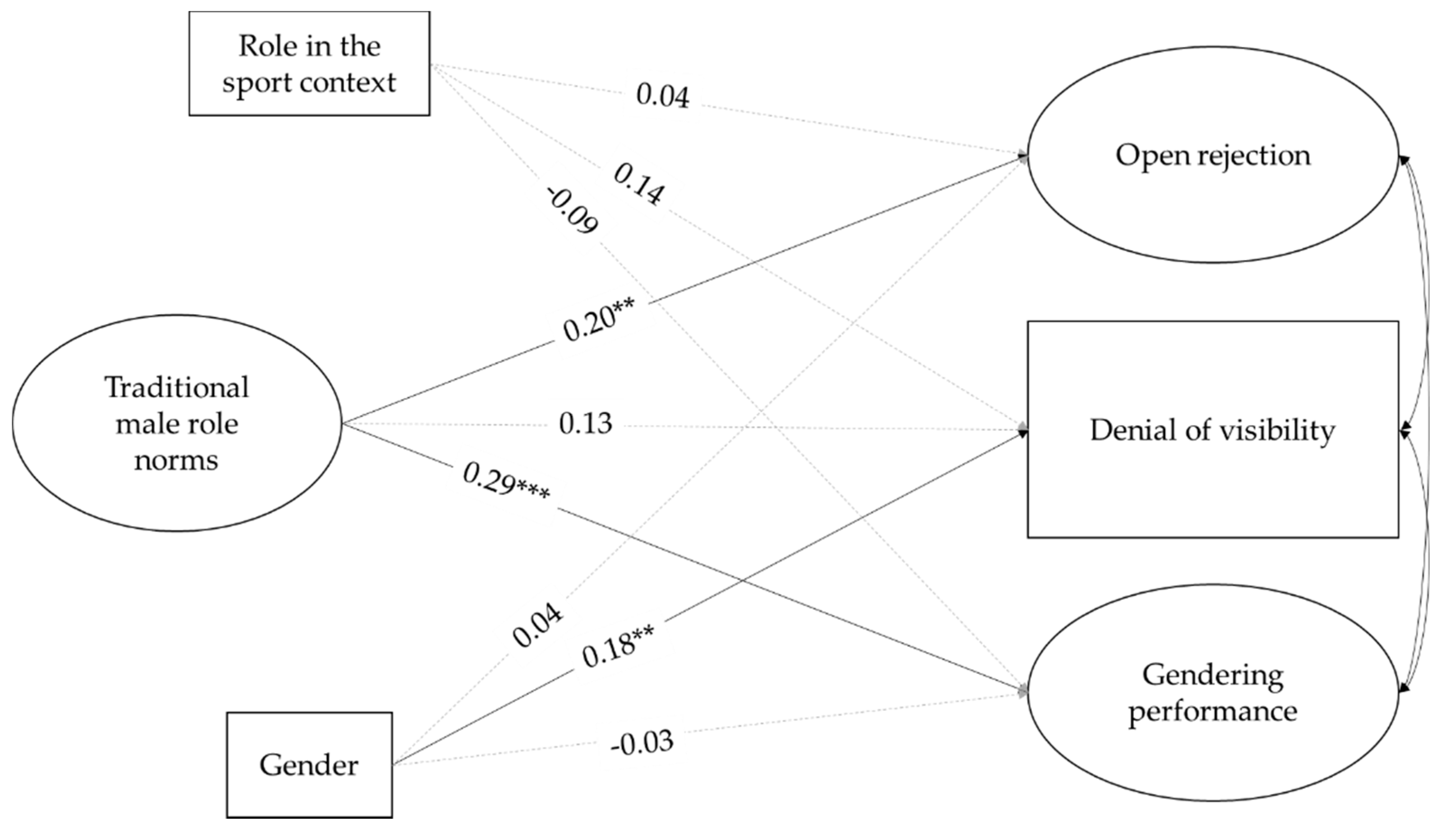

3.3. Gender Role Attitudes as Predictors of Sexual Prejudice in Sport

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Adi, Eric Anderson, and Mark McCormack. 2010. Establishing and Challenging Masculinity: The Influence of Gendered Discourses in Organized Sport. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 29: 278–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodeo, Anna Lisa, Concetta Esposito, and Dario Bacchini. 2020. Heterosexist microaggressions, student academic experience and perception of campus climate: Findings from an Italian higher education context. PLoS ONE 15: e0231580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Eric. 2011. Inclusive masculinities of university soccer players in the American Midwest. Gender and Education 23: 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Eric. 2014. 21st Century Jocks: Sporting Men and Contemporary Heterosexuality. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Eric, Rory Magrath, and Rachael Bullingham. 2016. Out in Sport: The Experiences of Openly Gay and Lesbian Athletes in Competitive Sport. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchini, Dario, Concetta Esposito, Gaetana Affuso, and Anna Lisa Amodeo. 2020. The Impact of Personal Values, Gender Stereotypes, and School Climate on Homophobic Bullying: A Multilevel Analysis. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, Roberto, Jessica Pistella, Marco Salvati, Salvatore Ioverno, and Fabio Lucidi. 2018. Sports as a risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a sample of gay and heterosexual men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 22: 385–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiocco, Roberto, Jessica Pistella, Marco Salvati, Salvatore Ioverno, and Fabio Lucidi. 2020. Sexual Prejudice in Sport Scale: A New Measure. Journal of Homosexuality 67: 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackenridge, Celia, Pam Alldred, Ali Jarvis, Katie Maddocks, and Ian Rivers. 2008. A Review of Sexual Orientation in Sport. Edinburgh: Sportscotland. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Anthony, Eric Anderson, and Sam Carr. 2012. The Declining Existence of Men’s Homophobia in British Sport. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education 6: 107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capranica, Laura, and Fabrizio Aversa. 2002. Italian Television Sport Coverage during the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 37: 337–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Raewyn W. 1990. An iron man: The body and some contradictions of hegemonic masculinity. In Sport, Men and the Gender Order. Edited by Michael A. Messner and Donald F. Sabo. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic Masculinity. Gender & Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, George B. 2011. Creative Work Environments in Sport Organizations: The Influence of Sexual Orientation Diversity and Commitment to Diversity. Journal of Homosexuality 58: 1041–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, George B., and E. Nicole Melton. 2012. Prejudice against Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Coaches: The Influence of Race, Religious Fundamentalism, Modern Sexism, and Contact with Sexual Minorities. Sociology of Sport Journal 29: 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, George B., and E. Nicole Melton. 2013. The Moderating Effects of Contact with Lesbian and Gay Friends on the Relationships among Religious Fundamentalism, Sexism, and Sexual Prejudice. Journal of Sex Research 50: 401–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, George B., and Melanie L. Sartore. 2010. Championing Diversity: The Influence of Personal and Organizational Antecedents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 40: 788–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, Steven, Tanya Forneris, Ken Hodge, and Ihirangi Heke. 2004. Enhancing Youth Development through Sport. World Leisure Journal 46: 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashper, Kate, and Thomas Fletcher. 2013. Introduction: Diversity, equity and inclusion in sport and leisure. Sport in Society 16: 1227–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis-Delano, Laurel R. 2014. Sport as Context for the Development of Women’s Same-Sex Relationships. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 38: 263–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, Kevin G., and Blye W. Frank. 2007. Sexualities, genders, and bodies in sport: Changing practices of inequity. In Sport and gender in Canada. Toronto: Oxford University Press Canada, pp. 178–93. [Google Scholar]

- Elling, Agnes, and Annelies Knoppers. 2005. Sport, Gender and Ethnicity: Practises of Symbolic Inclusion/Exclusion. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 34: 257–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernulf, Kurt E., and Sune M. Innala. 1987. The relationship between affective and cognitive components of homophobic reaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior 16: 501–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fynes, Jamie M., and Leslee A. Fisher. 2016. Is Authenticity and Integrity Possible for Sexual Minority Athletes? Lesbian Student-Athlete Experiences of U.S. NCAA Division I Sport. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal 24: 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Diane L., Ronald G. Morrow, Karen E. Collins, Allison B. Lucey, and Allison M. Schultz. 2006. Attitudes and Sexual Prejudice in Sport and Physical Activity. Journal of Sport Management 20: 554–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Griffin, Pat. 1992. Changing the Game: Homophobia, Sexism, and Lesbians in Sport. Quest 44: 251–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Pat. 1998. Strong Women, Deep Closets: Lesbians and Homophobia in Sport. Champaign: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, Pat. 2014. Overcoming sexism and homophobia in women’s sports: Two steps forward and one step back. In Routledge Handbook of Sport, Gender and Sexuality. Edited by Jennifer Hargreaves and Eric Anderson. London: Routledge, pp. 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, Gregory M. 2000. The Psychology of Sexual Prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science 9: 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, Gregory M., and John P. Capitanio. 1996. “Some of My Best Friends” Intergroup Contact, Concealable Stigma, and Heterosexuals’ Attitudes toward Gay Men and Lesbians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22: 412–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, Gregory M., and Linda D. Garnets. 2007. Sexual Orientation and Mental Health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 3: 353–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoura, Anna, and Marja Kokkonen. 2020. What do we know about the sporting experiences of gender and sexual minority athletes and coaches? A scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, Bruce. 2008. A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport in Society 11: 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolnes, Liv-Jorunn. 1995. Heterosexuality as an Organizing Principle in Women’s Sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 30: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosciw, Joseph G., Emily A. Greytak, Adrian D. Zongrone, Caitlin M. Clark, and Nhan L. Truong. 2018. The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN). Available online: https://www.glsen.org/research/2017-national-school-climate-survey-0 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Krane, Vikki. 2018. Sex, Gender, and Sexuality in Sport: Queer Inquiries. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawley, Scott. 2018. LGBT+ Participation in Sports: ‘Invisible’ Participants, ‘Hidden’ Spaces of Exclusion. In Hidden Inequalities in the Workplace. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lease, Suzanne H., Ashley B. Hampton, Kristie M. Fleming, Linda R. Baggett, Sarah H. Montes, and R. John Sawyer. 2010. Masculinity and interpersonal competencies: Contrasting White and African American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 11: 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sae-Mi, Juan M. Lombera, and Leslie K. Larsen. 2019. Helping athletes cope with minority stress in sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action 10: 174–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Woojun, and George B. Cunningham. 2016. Gender, Sexism, Sexual Prejudice, and Identification with U.S. Football and Men’s Figure Skating. Sex Roles 74: 464–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Woojun, and George B. Cunningham. 2019. Group diversity’s influence on sport teams and organizations: A meta-analytic examination and identification of key moderators. European Sport Management Quarterly 19: 139–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingiardi, Vittorio, Simona Falanga, and Anthony R. D’Augelli. 2005. The Evaluation of Homophobia in an Italian Sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior 34: 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingiardi, Vittorio, Nicola Nardelli, Salvatore Ioverno, Simona Falanga, Carlo Di Chiacchio, Annalisa Tanzilli, and Roberto Baiocco. 2016. Homonegativity in Italy: Cultural Issues, Personality Characteristics, and Demographic Correlates with Negative Attitudes toward Lesbians and Gay Men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 13: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Mingli, Lang Wu, and Qingsen Ming. 2015. How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10: e0134804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macgillivray, Ian K. 2000. Educational Equity for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgendered, and Queer/Questioning Students. Education and Urban Society 32: 303–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Ilan H. 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin 129: 674–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, Robert C., and Gerald Walton. 2014. Catchalls and Conundrums: Theorizing “Sexual Minority” in Social, Cultural, and Political Contexts. Philosophical Inquiry in Education 22: 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, Linda K., and Bengt O. Muthén. 2017. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Kerry S., Heather Shovelton, and Janet D. Latner. 2013. Homophobia in physical education and sport: The role of physical/sporting identity and attributes, authoritarian aggression, and social dominance orientation. International Journal of Psychology 48: 891–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronger, Brian. 2012. Homosexuality and Sport: Who’s Winning? In Masculinities, Gender Relations, and Sport. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc., pp. 222–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore-Baldwin, Melanie L., ed. 2013. Gender, Sexuality, and Prejudice in Sport. In Sexual Minorities in Sports: Prejudice at Play. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sartore, Melanie L., and George B. Cunningham. 2009a. Gender, Sexual Prejudice and Sport Participation: Implications for Sexual Minorities. Sex Roles 60: 100–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartore, Melanie L., and George B. Cunningham. 2009b. The Lesbian Stigma in the Sport Context: Implications for Women of Every Sexual Orientation. Quest 61: 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, Cristiano, Ornella Braucci, Vincenzo Bochicchio, Paolo Valerio, and Anna Lisa Amodeo. 2019. “Soccer is a matter of real men?” Sexist and homophobic attitudes in three Italian soccer teams differentiated by sexual orientation and gender identity. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 17: 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulenkorf, Nico, and Deborah Edwards. 2012. Maximizing Positive Social Impacts: Strategies for Sustaining and Leveraging the Benefits of Intercommunity Sport Events in Divided Societies. Journal of Sport Management 26: 379–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symons, Caroline, and Matthew Klugman. 2014. The Silence after the Storm: The Akermanis Affair, Sexuality, Masculinity and Australian Rules Football. In Acts of Love and Lust: Sexuality in Australia from 1945–2010. Edited by Lisa Featherstone, Rebecca Jennings and Robert Reynolds. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 151–73. [Google Scholar]

- Symons, Caroline, Grant A. O’Sullivan, and Remco Polman. 2017. The impacts of discriminatory experiences on lesbian, gay and bisexual people in sport. Annals of Leisure Research 20: 467–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Edward H., and Joseph H. Pleck. 1986. The Structure of Male Role Norms. American Behavioral Scientist 29: 531–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veri, Maria J. 1999. Homophobic Discourse Surrounding the Female Athlete. Quest 51: 355–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, Bernard E. 2001. Gender-role variables and attitudes toward homosexuality. Sex Roles 45: 691–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2010. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241599979 (accessed on 26 November 2020).

- Zamani Sani, Seyed H., Zahra Fathirezaie, Serge Brand, Uwe Pühse, Edith Holsboer-Trachsler, Markus Gerber, and Siavash Talepasand. 2016. Physical activity and self-esteem: Testing direct and indirect relationships associated with psychological and physical mechanisms. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 12: 2617–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean (Range 1–7) | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall sample | ||||||

| 1. Traditional Male Role Norms | 1 | 2.80 | 1.40 | |||

| 2. Open rejection | 0.20 *** | 1 | 1.24 | 0.65 | ||

| 3. Denial of visibility | 0.14 | 0.41 *** | 1 | 2.34 | 1.02 | |

| 4. Gendering performance | 0.24 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | 1.62 | 0.87 |

| Women only | ||||||

| 1. Traditional Male Role Norms | 1 | 2.40 | 1.30 | |||

| 2. Open rejection | 0.23 * | 1 | 1.17 | 0.51 | ||

| 3. Denial of visibility | 0.22 | 0.42 *** | 1 | 2.16 | 0.97 | |

| 4. Gendering performance | 0.30 * | 0.53 *** | 0.42 *** | 1 | 1.52 | 0.79 |

| Men only | ||||||

| 1. Traditional Male Role Norms | 1 | 3.06 | 1.41 | |||

| 2. Open rejection | 0.16 * | 1 | 1.26 | 0.63 | ||

| 3. Denial of visibility | 0.05 | 0.36 *** | 1 | 2.43 | 1.02 | |

| 4. Gendering performance | 0.19 * | 0.59 *** | 0.37 *** | 1 | 1.66 | 0.87 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amodeo, A.L.; Antuoni, S.; Claysset, M.; Esposito, C. Traditional Male Role Norms and Sexual Prejudice in Sport Organizations: A Focus on Italian Sport Directors and Coaches. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120218

Amodeo AL, Antuoni S, Claysset M, Esposito C. Traditional Male Role Norms and Sexual Prejudice in Sport Organizations: A Focus on Italian Sport Directors and Coaches. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(12):218. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120218

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmodeo, Anna Lisa, Sabrina Antuoni, Manuela Claysset, and Concetta Esposito. 2020. "Traditional Male Role Norms and Sexual Prejudice in Sport Organizations: A Focus on Italian Sport Directors and Coaches" Social Sciences 9, no. 12: 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120218

APA StyleAmodeo, A. L., Antuoni, S., Claysset, M., & Esposito, C. (2020). Traditional Male Role Norms and Sexual Prejudice in Sport Organizations: A Focus on Italian Sport Directors and Coaches. Social Sciences, 9(12), 218. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9120218