Abstract

The purpose of this participatory research project is to examine the lived experiences (counter-life stories) of current and former Dunbar residents and congregants of Dunbar churches to demonstrate how local stories counter the dominant perspective about the experiences of American Americans in the Dunbar community. Once a thriving community at the center of civil rights activities in Hays County, Texas, the neighborhood has evolved in many ways in the past several decades, contrary to popular belief. This case study employs counter-life story methodology to uncover the hidden truths about Dunbar residents and congregants’ experiences to generate new knowledge about the experiences of African Americans in San Marcos, Texas, and Hays County. Thematic analysis of unfiltered commentary from Dunbar community members revealed three emergent themes: history of racism and slavery, impact of environmental and social racism, and rebuilding and restoring the community. Individual and shared strengths make the community unique and resilient. In-migration of new community members has been outpaced by outmigration. Finally, issues of taxation, representation, and the ongoing deterioration of neighborhood infrastructure are forefront in community members’ minds. In sum, the bedrock of personal and community values and hard work has not changed, but external forces continue to affect the community and compel it to pivot and make plans for change. Personal and communal strengths make the community unique and resilient. Future work will enlist geographic data and methods to help further investigate changes over time.

1. Introduction

Counter-life stories are narratives about peoples’ lives that run contrary to widespread knowledge or general understanding of events. Counter-life storytelling can serve as a form of resistance to standard or majority stories and understanding (Hubain et al. 2016). In critical race theory, counter-stories have been useful in creating theories, using methods, and implementing pedagogies that challenge racism, sexism, and classism and work toward social justice (Solórzano and Yosso 2002). In this study, a team of interdisciplinary researchers at Texas State University conducted a life history study in the historic Dunbar neighborhood of San Marcos, Texas, to illuminate lived encounters that challenge and add depth to the prevailing, majority perspective of African Americans. This participatory research project aims to examine the lived experiences (counter-life stories) of current and former Dunbar residents and Dunbar churches’ congregants to inform current and future actions in the Dunbar community.

Historical research into African Americans’ lives across the country has been marred by considerable challenges, namely the lack of existing documentary evidence to construct a cohesive narrative. This type of scholarship focuses heavily on the oral tradition of culture as it relates to African Americans. The use of oral histories as a tool for creating African American historical scholarship is critical as it allows researchers to unearth the lived and subaltern narratives that underpin the lives of African Americans. Scholars underscore the importance of utilizing oral histories in African American historical research and scholarship due to the historic underrepresentation of African Americans and their stories within mainstream historical literature and scholarly discourse (Alexander and Austin 2010). Little has been written about African Americans’ lived experiences in the Dunbar community, which is not surprising given the historical underrepresentation of the neighborhood within the municipality and the legacy of slavery. The #ReclaimDunbar project is the first attempt to date to expose these obscured histories (Ashford-Hanserd 2018). The #ReclaimDunbar project aims to examine the counter-life stories that contradict existing mainstream narratives about historically marginalized peoples. By uncovering these hidden truths, researchers hope to understand the factors that drive Dunbar’s in- and outmigration and help protect its remaining cultural assets.

Using an equity and participatory design-based research approach (Creswell 2014), we collaborated with faith and community leaders in the historic African American Dunbar community. We conducted counter-life story interviews (Ashford 2016; Ashford-Hanserd 2020) with current and former Dunbar neighborhood residents and Dunbar churches’ congregants. We provided participants with a Dunbar community map that reflected the historical boundaries to spur their recollection of stories and places during the interviews. The interviews’ results were analyzed following a thematic methodological approach (Braun and Clarke 2006) to describe the hidden truths about former residents’ experiences in the Dunbar community. A counter-historical account was used to interpret our findings. The results of the counter-life story interviews show that personal and communal values and events are intertwined. These findings will inform the development of a follow-up survey.

The following research question flows from the historical literature and frames this study. What are the counter-life stories (lived experiences) of current or former residents, and current or former congregants, in the historically African American Dunbar neighborhood after the Civil War that counter the master narrative about African Americans’ experiences in Dunbar? Our findings establish, through counter-life stories offered by Dunbar residents, the following dimensions hidden by the historical record: (1) racism and slavery inform community history, (2) environmental and social racism impact community identity and resources, and (3) rebuilding and restoring the community is a priority. Our findings will show the community perspective of how racism and environmental damage impacted community building.

2. Literature Review

In this literature review, we share foundational knowledge about the oral tradition within African American communities. We also recount the recorded history of the Dunbar neighborhood to reveal its gaps and limitations.

2.1. Oral Tradition and Historical Research within African American Communities

How cultural information is spread through oral tradition is a significant theme underpinning African American studies. Alexander and Austin (2010) dive into the oral tradition’s significance within African and African American studies. African and African American history during the period of slavery was overwhelmingly preliterate. The transmission of culture, values, myth, and history happened through the medium of oral tradition. Alexander and Austin (2010) contend that oral history is:

Scholars have recognized that utilizing oral tradition and oral history is critical to attempting African American historical research and scholarship (Alexander and Austin 2010). This notion has primarily been due to the lack of representation of the African American community within historical literature and scholarly discourse until recent decades. The political, economic, and social repression of the African American community has also historically played a role in how oral traditions are the primary medium of how history is transmitted within the African American community.fundamental to understanding the African American experience’s essence. Indeed, we maintain that no exploration of African American life or political consciousness is complete without analyzing and discussing oral culture and history of giving voice to the people themselves.(p. 171)

The authors also make a strong point that African oral tradition traces its lineage back to pre-colonial West African civilizations. African peoples transmitted cultural information solely through the oral and, in extension, visual means. The oral traditions and oral histories are the cornerstones to unlocking the African American experience. Alexander and Austin argue that “Oral history is a valuable resource for civil rights and social movement scholars” (Alexander and Austin 2010, p. 175). In many ways, oral histories are a form of counter-history or counter-narratives against the African community’s stereotypes and assumptions. Alexander and Austin explain that these histories are “often the domain of those who choose to give voice to people who would be mere footnotes in many types of traditional historical documents” (Alexander and Austin 2010, p. 175). Moreover, the authors are quick to note that oral traditions and oral histories are “especially salient” as they help to make sense of the African American Civil rights movement, as well as the memories and experiences of those who lived through it (Alexander and Austin 2010, p. 175).

2.2. The Dominant Perspective of the History of the Dunbar Neighborhood

The established recorded history of Texas and the Dunbar neighborhood was not derived from local stories. Instead, it was derived from academic research of particular sources. We define the official historical record as documents produced by governmental agencies and widely disseminated accounts such as newspapers. This section summarizes those accounts.

Some historic resource surveys (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996), documentation by historical societies (Van Oudekerke 2011; Texas Historical Commission 1988, 1990), and class projects (Renick et al. 2006; San Marcos Main Street Program n.d.) have also documented essential people and places in Dunbar history. However, these details were acquired by scholars disconnected from the lived experiences of African Americans in Dunbar. Once a thriving community at the center of civil rights activities in Central Texas, the Dunbar neighborhood has evolved in many ways—some for the worse. Counter-life stories help expose the microcosmic causes and effects of the drastic changes that the neighborhood underwent, which counter the prevailing, majority perspective about Dunbar’s African Americans’ experiences. The history of African American settlement in San Marcos is sparsely documented since the end of the Civil War (i.e., 9 April 1865), as the overwhelming majority of San Marcos’ African American history consists of oral histories. As a result, textual documentation can only paint an incomplete picture of the reality on the ground.

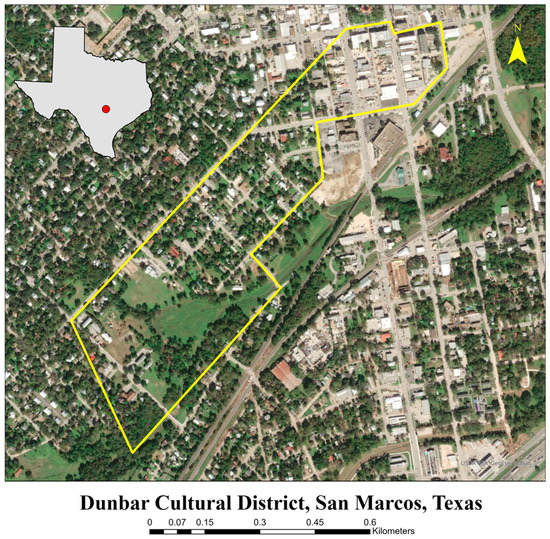

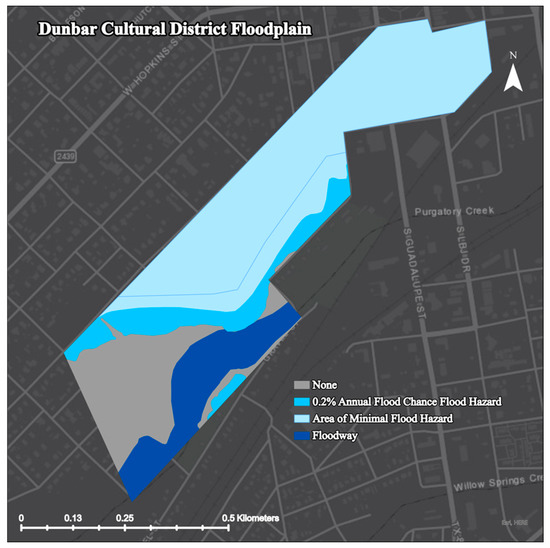

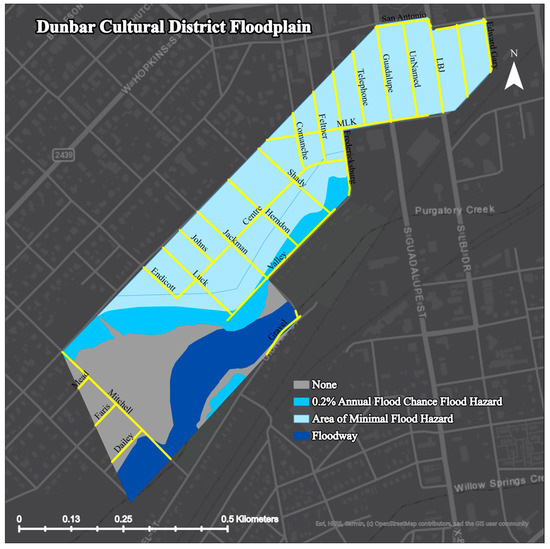

A local governmental survey became an important source of official history. In 1996, a historic resource survey submitted by the City of San Marcos surveyed both the Dunbar (i.e., historically African American), located in the Purgatory Creek watershed, and Guadalupe (i.e., historically Mexican-American) neighborhoods. It reported that these two neighborhoods were “hampered by the lack of documentary evidence, thus resulting in a reliance on interviews with local historians and oral history” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996, p. 12; Stovall et al. 1986). Other historical accounts support or expand the 1996 historic resource survey findings, although they are not solely focused on the community.

The city’s local history regarding the Dunbar neighborhood and African American people in general, both as slaves and as freedmen, is sparse. The survey went as far as to report that much of the area’s historical city directories, libraries, and archives do not date any further than 1950 (Texas Historical Commission 1990). According to Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. (1996), Dunbar was first settled by Anglo farmers, and the Dunbar neighborhood itself was populated by African American freedmen directly following the Civil War who lived in small enclaves. These individuals worked on the local farms, in affluent white neighborhoods as domestic servants, and at local businesses like gins, lumber companies, and warehouses.

The Freedmen’s Bureau played a part in Dunbar’s history. As early as 1868, the Freedmen’s Bureau, in acknowledgment of Dunbar’s population, helped found the Freedmen’s school, which operated out of a church. Much of the neighborhood’s social activities and schooling were fostered in the community’s churches. “Churches played a critical role for the neighborhood both as a religious and social center” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996). Evidence is present that the Dunbar neighborhood was well established as a segregated community within a decade following Emancipation. Numerous African American businesses operated along Martin Luther King Street, known as “The Beat” and, “…these commercial establishments served the needs of the African American residents who were often denied services in Anglo businesses during the period of segregation” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996).

The history of white San Marcos residents also reveals details about Dunbar’s African American history and race relations. The Heritage Association of San Marcos, Inc. commissioned Robert Van Oudekerke (2011) to produce the book “Historic San Marcos: An Illustrated History”, which provided illustrations of the Anglo-American settlers in San Marcos and their contributions with few examples of contributions by African Americans. Van Oudekerke (2011) states that “San Marcos has been inhabited for almost 12,000 years” (p. 9). His historical account begins in June of 1861 when “Spanish Governor Domingo Teran de Los Rios arrived at the San Marcos river’s headwaters to find thousands of Indians from at least six different tribes.” He further described the historical events that led to the “first white settler of the modern-day San Marcos” (p. 10). W. W. Moon. Moon purchased “a Negro man named Harry, a blacksmith by trade, about twenty-eight years of age” (p. 10) to be a blacksmith in his shop. The Hays County of Texas record warranted Harry as “sound and healthy in every respect and a slave for life.” He also mentioned white female schoolteachers (i.e., Mrs. Melissa Charlot and Mary Sublet) who taught the “children of slaves” (p. 47). He believed “only a few families in Hays county actually owned slaves” (p. 23).

Despite the adverse effects of the Depression after WWII and segregation, then current structures illustrated wealth in the community. The majority of buildings were detached dwellings, many of which had garages, which illustrated the owners could afford an additional freestanding structure. While the writer of “The Economic Impact of the Dunbar Neighborhood on San Marcos” report (n.d.) is unknown, it comprises three historical accounts: Dunbar Neighborhood, 1930’s by Shannon Williams, The Dunbar Neighborhood in the 1950s by Jonathan M. Palmer, and Dunbar Heritage and Museums District by Dr. Gene Bourgeois, the former Chair of the Department of History at Texas State University and current Provost. In Shannon Williams’ historical article, she attributed the growth and prosperity of the Dunbar community to the activities of the historic First Baptist Church and prominent individuals such as Ulysses Cephas. She indicated that the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1932, which were recorded by traveling surveyors illustrate the economic worth of the area. Finally, she indicated the occurrence of fires in Dunbar and San Marcos were quite frequent. For example, Dunbar lost several buildings due to fires in 1932. Jonathan M. Palmer authored a historical fiction article recounting historical sites in Dunbar, which included descriptions of locations and social centers in the neighborhood. In Dr. Gene Bourgeois’s account, he shared a plan for a multi-acre heritage, cultural tourism, and economic development initiative primarily located in the Dunbar Historic District (i.e., established in 2003). This integrated development project reflected several goals identified in the “1996 San Marcos Horizons Master Plan.” It included involvement from the following departments at Texas State University: Geography, Family and Consumer Sciences, and the Department of History’s Center for Texas Music History. This initiative birthed the annual Eddie Durham Jazz Festival/Celebration hosted by the university’s School of Music.

Prominent individuals lived in the Dunbar neighborhood of San Marcos, TX, and their stories also link the neighborhood to histories of segregation and slavery. One of the most famous persons to have originated from San Marcos was Ulysses Cephas, a local blacksmith and community leader. Cephas was born in San Marcos on 13 June 1884 to Elizabeth Allen Cephas and her husband Joseph Cephas, former slaves (Texas Historical Commission 1988; Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996). The Texas Historical Commission (1988) acknowledged that Joseph Cephas was a slave in San Marcos during its early history dating back to 1850, a period that is still shrouded in obscurity. Joseph Cephas arrived in San Marcos when he was purchased by William Thompson in 1850 at a slave market in New Orleans, Louisiana, on behalf of Sarah Burleson, the widow of General Burleson, founders of Hays Country in 1848. Thompson was the owner of both Thompson Island and the slave plantation. When Joseph Cephas was finally free from bondage, he built a home for his wife and son in San Marcos, where we would teach his son his trade of being a blacksmith. When Ulysses came of age, he would open up a blacksmithing business of his own where he became extremely talented at his trade and operated for forty years. Paul Rutledge, one of several essayists who contributed to the 1988 Texas historical marker application, lamented that “Cephas was the last public blacksmith and horseshoe marker in the central Texas locale and many of his talents are legends today” (Texas Historical Commission 1988, p. 27).

Cephas played a prominent role as a community leader in the Dunbar neighborhood, mainly in the community’s church and religious activities. He attended the First Baptist Church in Dunbar. In 1924, he became a church trustee, where he helped with various church activities such as dinners, baptisms, recreation, and other activities (Texas Historical Commission 1988). Cephas was also a talented musician who sang in his church choir. He was part of a community marching band containing forty-five members marched in parades in San Marcos, New Braunfels, Waelder, and Austin. The band was particularly active every year during the annual June 19th Texas Emancipation Day celebration. In the 1920s, Cephas built a home for him and his wife on 217 Comal St. which still exists today. In 2003, the City of San Marcos bought the home to refurbish it and preserve it as a local landmark for $43,799 using federal funds after many Dunbar residents lobbied the city to take action (O’Rourke 2013; Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996). The Cephas House is an essential landmark of the Dunbar neighborhood. It is located just feet from the historic First Baptist Church and the Cephas House on 231 Martin Luther King Dr. The House was constructed by Cephas himself and his family during the 1920s. The home’s architecture is reminiscent of those in the surrounding area, utilizing the “shotgun” style in common in African American communities in New Orleans and Mississippi (Peterson 2013; Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996). The House is still in use today as a community event center.

The Calaboose African American History Museum keeps the legacy of the Dunbar neighborhood. It also further substantiates Dunbar’s history of segregation and racial disparity, because it was once a segregated jail for African Americans. Located at 200 W. Martin Luther King Drive, the Calaboose (Spanish for jail) was first built in 1873 consisting of a half-brink and wood construction and served as Hays county’s first official jailhouse and was later used as a segregated jailhouse for African American inmates (Texas Historical Commission 1990). In 1885, the building would be repurposed as a community recreation center in what is now considered the Dunbar neighborhood. During World War II, African American service members stationed at the new Gary Army Air Force Base used the Calaboose as the primary location to host their U.S.O. Meetings (Texas Historical Commission 1990). In 1954, the Calaboose would again be converted into a community center for the Dunbar neighborhood. In 1990, after years of disrepair and neglect, the Calaboose underwent a considerable overhaul led by Johnnie Armstead, and by 1997 she founded the Calaboose African American History museum (Brantley 2018; Herod 2018). The Calaboose museum contains a wide assortment of memorabilia in its collection from the civil rights era, the Tuskegee Airmen, slave relics, newspaper clippings, local memorabilia, and an authentic Ku Klux Klan hooded robe donated to the museum by a San Marcos resident, yet another indication of a past of racial tensions in the community (Brantley 2018).

Additional historical structures—a church and a school—also demonstrate the legacy of Dunbar’s racial tension. The original historic First Baptist Church was built in 1866 by Reverend Moses John, who founded the Church on Guadalupe Street (Texas Historical Commission 1988). However, in 1873, the Ku Klux Klan set the Church on fire and caused significant damage. The Church was later rebuilt in 1908 on 219 Martin Luther King Dr., where it still stands today. In 1986, the Church would later be vacated once a third structure was built to replace it (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996; O’Rourke 2013). The Church is characterized by its two large bell towers, gabled porch, and double-door entrance. The Church is also conveniently located next to the historic Cephas house and across the street from the historic Calaboose African American history museum. Finally, the Dunbar School/Community Center is a fixture in the neighborhood. The Dunbar school or Colored school was segregated. It was initially constructed in the 1880s for Anglo children but was later moved to the Dunbar neighborhood and designated a segregated school (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996). Van Oudekerke (2011) documented that a school board of examiners was formed in 1858 to organize the “Negro School” (p. 47) in San Marcos, but the Negro School was not organized until 13 January 1877. In 1961, the school was renamed to Dunbar by the school board in honor of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, an acclaimed African American poet.

Other historical accounts have documented the oral histories or stories of some Dunbar residents and congregants of Dunbar churches as influencers. In the first edition of The Ties That Bind book by Renick et al. (2006), students conducted an oral history project with 21 senior residents of San Marcos to “address some of the issues of bias and prejudice that occurred or were occurring in the San Marcos community” (p. xii). While this study did not focus solely on the Dunbar community, nine of the 21 participants were African Americans that either lived in Dunbar or lived in San Marcos but attended an African American Dunbar church: Harvey Miller, Marguerite Cheatham Hill, Ollie Giles, Rose Lee Brooks, Reverend Herman Foster, Lucille Cheatham, Reverend Alfonso Washington, Forest Manjang, and Charlie Williams. Each story provided information about the participants’ origins and accomplishments, summarized into no more than four pages to provide a general overview of their experiences. This account offered a glimpse of African Americans’ lived experiences in the brief narratives of these participants.

Some of the accounts offered include the following: Ms. Giles recommended that former slaves’ names be placed in “visible and prominent places around the town of San Marcos” (p. 40). Ms. Rose Brooks recalled her experience in the 1980s when she “spoke out” (p. 49) at a school board hearing concerning a school superintendent who attempted to impose policies that were racist in nature. Ms. Lucille Cheatham (“Mama Red”) recalled when a “young man drowned and how much that hurt her” (p. 62). Mr. Charlie Williams described his experience as a young boy in San Marcos balancing school, social activities, and working a part-time job picking cotton. He graduated from Dunbar Colored High School and went on to become the commissioner for urban renewal. Mr. Malcolm Fleming (Anglo man) pushed for the integration of schools in San Marcos when he discovered its unsafe conditions. He said “While I was on the School Board I made a trip down to what they called Dunbar; it was supposed to be a Colored school. I walked in there and almost broke my leg by stepping through the floor. They had an open-gas heater in there with asbestos. Half of the schoolbooks did not have any backs on them. It was a horrible situation. They could not have that. So, I went back to the School Board and made an effort to integrate San Marcos.” While this resource provides valuable insight into the lives of notable African American figures in San Marcos and the Dunbar community and jewels of information concerning African Americans’ racialized experiences, this account’s purpose was not to illuminate the experiences resulting from racial bias and prejudice or racism. This omission seems to downplay the impact of racism and prejudice in the community.

2.3. Counter-History Account

While many elements of this dominant history are accurate and useful, other documents such as the census and historical markers kept by the Texas Historical Commission, and artifacts, newspaper clippings, church histories (e.g., First Baptist Church N.B.C. n.d.), and slave relics held by African American-led organizations, such as the Calaboose African American History Museum and the Dunbar Heritage Association in San Marcos, help reveal the cracks and gaps in the traditional historical accounts. While this historical account is not exhaustive, it fills some of the cracks and gaps in the traditional historical accounts.

Even though the official historical account reports incidents of Ku Klux Klan activity (i.e., burning old first Baptist Church, authentic Ku Klux Klan hooded robe donated to Calaboose), it lacks connection to lived experiences or encounters with slavery or racism. When the Texas legislature designated San Marcos as the county seat for Hays County, the 1850 census indicated 378 residents, 128 of whom were slaves (Butler 2016, p. 9; Crouch and Madaras 2007). Moreover, in the 1860 schedule-2 slave census for Hays County, it was reported that some 94 persons had owned slaves, which equated to approximately 797 slaves in the entire county. For example, according to the Heritage Association of San Marcos, the Thompson family moved to San Marcos to escape a yellow fever epidemic that ravished Alabama and Mississippi and brought several slaves with them (Kimmel 2006, p. 86; Crouch 1999). The Thompson family used slave labor to construct a series of ditches for irrigation to power their sawmill and gin on the family’s plantation (Stovall et al. 1986, p. 172; Butler 2016). In a recent guest column in the San Marcos Daily Record by Jordan Buckley (2019) entitled Let’s Acknowledge the Role of Slave Labor, he addresses this same issue. He states, “Violent white supremacy is an unshakable reality of San Marcos history. However, white supremacy continues to thrive when we erase the contributions of those whose forced labor yielded local landmarks that today we cherish—and instead amend history to solely admire the enslavers.”

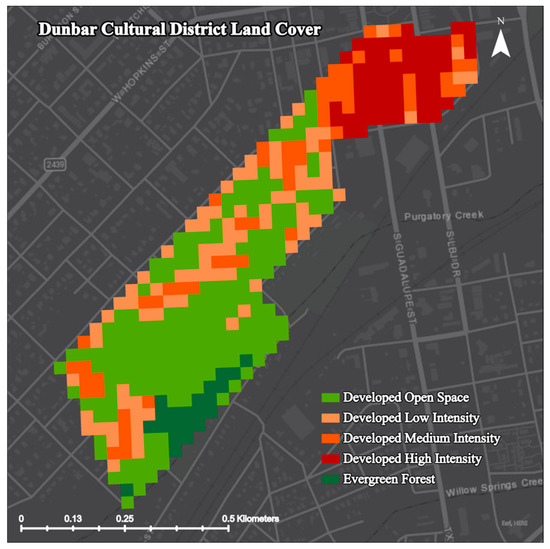

Furthermore, the official documents do not identify Dunbar as being situated in the Purgatory Creek flood plain or note other forms of geographic and environmental racism that has affected the neighborhood. Early African American families were allowed to live in San Marcos along the Purgatory Creek floodplain (i.e., the Dunbar community) as this land was not considered desirable for white settlers. As small enclaves grew in what is now known as the Dunbar area, “The Purgatory Creek watershed continually threatened the area with flooding” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996, p. 12). As time passed and the city did not provide for the African American population, the first African American men to own property in San Marcos were five individuals who purchased land for a cemetery in 1893 to dispose of the dead outside of the floodplain properly. In the early 1970s, one of the worst floods to hit the area occurred, and instead of rebuilding new structures, “… there is an indication that existing houses were simply moved into the area rather than new construction replacing homes washed away by the floods” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996, p. 12).

There is some debate amongst academic circles about the existence of a freedmen’s colony within San Marcos proper. Several freedmen’s colonies had been documented in the surrounding areas, and the Freedmen’s Bureau organized the initial Colored school in San Marcos. However, African Americans were indeed present in San Marcos as early as 1850, but not all freedmen. The Calaboose jailhouse’s presence in what is now the Dunbar neighborhood may dispel the notion that Dunbar could have been a freedmen’s colony. The Calaboose jailhouse, which is now the African American History Museum, was first constructed in 1873 and served as Hays county’s first official jailhouse and later used as a segregated jailhouse for African American inmates (Kimmel 2006). The date of its construction indicates that it was built post-emancipation within the geographic confines of the Dunbar neighborhood. An inference can be made that the presence of a segregated jailhouse in the Dunbar area would not be analogous to an autonomous African American community like those found in Antioch, Clarksville, and Cedar Creek. This inference could indicate that the Dunbar area did not house a freedmen’s colony even though the Freedmen’s Bureau provided educational assistance for the slaves regulated to remain within the boundaries of the Dunbar neighborhood.

The historic Dunbar neighborhood was once marked as a “thriving community” shattered by segregation, outmigration, business closures, demolished buildings, and the onslaught of gentrification (Dunbar Heritage Association n.d.). Historical accounts of the Dunbar neighborhood have not shed light on the damaging effects of slavery, tragedies, and contextual influences that have plagued the community. For over a century, Dunbar has faced numerous barriers to preserving its history, culture, and overall economic prosperity. Dr. Elvin Holt (Calaboose President) and Mr. Richard Gachot (Batura 2010) further described the diminishing footprint of African Americans in San Marcos: “Decades ago, African-Americans comprised about 40–50 percent of the San Marcos population… According to the federal government’s 2006–2008 American Community Survey (A.C.S.), 5.2 percent of San Marcos residents are African-American (para 8).” Dr. Holt said, “The African-American presence in this neighborhood is being slowly erased. And I don’t think it’s intentional, because there’s a lot of construction going on. And those people who have lived here know that property that was originally owned by Blacks has passed into other hands, and so new people who come into town don’t know that Black folk ever lived there.” (para 9).

Fire and flooding played a large role in damaging community resources like historical documents and buildings. As the Dunbar area is flooded at least once every twenty-five years, formal written documents are challenging to find. Fires have played a destructive role in the neighborhood as well. Dunbar School was destroyed by fire, forcing educational institutions to operate out of churches. In recent years, the neglected structure has suffered considerable wear, and members of the Dunbar community have struggled to preserve this piece of their history (Texas State University 1996). The original Old First Baptist Church in Dunbar was burned to the ground by Ku Klux Klan members in 1873. Though this structure still stands, it has fallen into the late stages of disrepair. Tragedies such as these have resulted in ongoing community efforts (e.g., Dora Lee Brady Community Center, Old First Baptist Church Restoration Project) to rebuild this structure and to preserve other historic structures and spaces in Dunbar (Batura 2010; Click and Olvera 2018; Johnson 2010). Building upon these efforts, in October of 2018, the San Marcos Main Street Program told the public that the Church would be receiving a $150,000 grant to help renovate the Church and other historically significant structures in the area (Herod 2018).

As original written records and newer records were lost, Dunbar residents and congregants maintain their history through oral stories, remaining buildings, and traditions. Interviews are the best method in which to uncover Dunbar’s past. Historical accounts do not credit Dunbar residents and African American-led organizations’ efforts, including Dunbar churches, to revitalize and preserve the culture, historic structures, and history of African Americans in San Marcos. African American-led organizations, such as the Calaboose African American History Museum and the Dunbar Heritage Association, have toiled to preserve the history and culture of the Dunbar neighborhood in San Marcos with minimal support. The Calaboose African American History Museum was formed in 1997 to preserve African Americans’ history in San Marcos and Hays County. Since 1978, the Dunbar Heritage Association has preserved African American history by promoting festivals, performing arts, parades, and pageantry.

Moreover, African American churches in the Dunbar neighborhood have historically served as “the cradle of the Negroes economic, cultural, and spiritual life” in San Marcos (Dunbar Heritage Association n.d.). Churches have always played an essential role in African American communities throughout the U.S. (Billingsley and Caldwell 1991), and the historic churches in Dunbar are no different. They served a social hub for political, religious, and recreational activities that brought members of the African community closer together, particularly in the Jim Crow era.

Much of Dunbar’s authentic history is intertwined in the histories of Dunbar’s churches. For instance, (First Baptist Church N.B.C. (n.d.) reports that “Reverend Moses Johns and a small group of believers organized the Colored Baptist Church Zion (CBCZ) in 1866 and erected a sanctuary on property located on Guadalupe Street where Tuttle Lumber Company” (p. 1) once stood. CBCZ predated Wesley Chapel African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church—“the oldest African American congregation in San Marcos” (HMdb.org 2020, para 1). However, “the local Ku Klux Klan burned the sanctuary on Guadalupe Street in ca1873 in an attempt to capture a Black man who was thought to have been hiding in the church” (para 1). While the old First Baptist Church is one of the prominent church structures in Dunbar, Dunbar is home to six predominately African American churches representing the remnant of African Americans in Dunbar and San Marcos: Wesley Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church (established 1875), Greater Bethel Baptist Church (established 1883), First Baptist Church N.B.C. (established 1908), Jackson Chapel United Methodist Church (established 1964), Pentecostal Temple Church of God in Christ (unknown), and Antioch Church of our Lord Jesus Christ (unknown) (First Baptist Church N.B.C. n.d.; Groundspeak 2017; HMdb.org 2020; Sonier 2019). Dr. Shetay Ashford-Hanserd, assistant professor at Texas State University, is also leading an effort to “ReclaimDunbar” by forming a local cultural district with the Texas Commission on the Arts (Albiges 2018).

The Dunbar neighborhood’s official documentation and accounts show us that key stakeholders and places were essential to the community. However, this study shows how counter-life stories collected through this study reveal these discrete details from official history and add context and depth to uncover what made these key details so important. While not exhaustive, our counter-story expands the overall, majority perspective by adding these previously hidden truths.

3. Methods

Since there is a deficit of empirical studies that examine lived experiences in San Marcos, Texas, from the African Americans’ perspective, the counter-life story method is warranted for this study. Since “oppressed groups have known stories are an essential tool for their own survival and liberation” (Delgado 1989, p. 2436), critical race theorists have proposed the methodological use of counter-stories (or counter-narratives) in education research (Solórzano and Yosso 2002) to highlight people of color’s experiences and to “belie meritocratic, color-blind, and liberal majoritarian stories” (Closson 2010, p. 267). Bagley and Castro-Salazar (2012) interchangeably used the terms “counter-histories” and “counter-narratives” in their studies.

Since we believe counter-life history and counter-narrative research methods are analogous to life history and narrative research methods, we view the counter-life history method (or counter life-herstory) as a type of counter-narrative. As such, the counter-life story method places participants’ unique lived experiences in a broader socio-political context, unlike counter-narratives (or counter-stories), which focus on “making meaning” of lived experiences (Cole and Knowles 2001). In this article, we report and contextualize large verbatims from the life stories of community members in order to defer to their knowledge, expertise, and wisdom; provide an unadulterated, unfiltered reflection of their stories; and include participants themselves as much as possible in the reporting and storytelling of their lives.

3.1. Counter-Life Story Interview Protocol

The counter-life story interview, which is also referred to as counter-life herstories or counter-life histories (Ashford 2016), is derived from the life history method. Life histories seek to “understand how the patterns of different life stories can be related to their wider historical, social, environmental, and political context” and counter-narratives (Adriansen 2012, p. 41). Because life history data are primarily collected through individual interviews (Cole and Knowles 2001), the research team engaged directly with participants to conduct a one-on-one, in-depth interview (60 min) to obtain rich descriptions unique experiences in the Dunbar neighborhood.

3.2. Maps of the Dunbar Neighborhood

We provided maps of the Dunbar neighborhood to participants to mark and identify lost or demolished cultural assets that no longer exist in the neighborhood (See Appendix B). A member of the research team followed up with participants to schedule the interviews, or participants responded by showing up to the planned community conversation. Upon obtaining consent, members of our research team conducted 90 min interviews with each participant. If permitted, interviews were audio recorded using digital voice recorders.

Data Analysis and Interpretation Methods. We analyzed the data using an inductive thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke 2006) to analyze our results. To identify, analyze, and summarize themes, two coders followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step thematic analysis process. The first coder followed the six-step approach by first familiarizing herself with the participants’ counter-life story interviews through listening to interview audio files, reading interview transcripts. Second, she manually entered into a Microsoft Word document a list of codes, which were derived from the interview protocol and research question (See Appendix C). Third, she followed an inductive process to code interviews by manually organizing participants’ quotes under each associated code in the Word document and performed Open Coding by adding new codes as needed while reading the interview transcripts (Saldaña 2012). Fourth, she reviewed and refined the list of codes. Fifth, she identified high-level themes and manually regrouped the codes and the associated quotes under these themes. Finally, she produced a final report of emergent themes with the associated participants’ quotes. The second coder streamlined the manual coding process by importing participants’ transcripts into the NVivo qualitative data analysis software. He reproduced the first coder’s work by entering the existing codes into the Code Book and highlighting the associated quotes verbatim. Upon completion, he proceeded to conduct a second iteration of the Braun and Clarke (2006) thematic analysis process to refine the code list and emergent themes that addressed our research question. Our analyses produced a total of 195 codes. We utilized the counter-history account as a framework to analyze our findings.

To ensure trustworthiness and ethical considerations, we used data triangulation, member checking, and reflexivity (Crouch and Madaras 2007). Pseudonyms were used to describe given names and places for confidentiality. Our inductive analysis derived a codebook for the research. The new subject headings and search words were derived from inductive analysis processes where we identified critical dimensions in each quote and classified them by theme. Overall, the critical theory did inform our analysis insofar as we conducted a reflective assessment of where in the quotations we found answers, continuations, and new themes that emerged to underscore the gaps and answer the lingering questions that we identified in the official historical narrative. The research received I.R.B. approval [Texas State University I.R.B. #5879]. We changed all participants’ names, and we added bold for emphasis in long quotations for readability.

4. Results

The lived experiences (counter-life stories) of African Americans from the historic Dunbar neighborhood were shared by the following eight individuals, as depicted in Table 1. The original names were replaced to protect their identities. Laura, Meredith, and Robert represent a sibling group. We provide a timeline of Dunbar events in Appendix A and maps of the historic Dunbar neighborhood in Appendix B to accompany these counter-life stories.

Table 1.

Participants.

4.1. History of Racism and Slavery

This theme represents participants’ recollection of slavery and encounters with racism in the Dunbar neighborhood. Specifically, we sought to understand whether our participants remembered any encounters with racism (such as run ins with the Ku Klux Klan) and their interpretation of geographic and environmental racism. Five of eight participants shared personal memories related to this theme. Life in the Dunbar community was a place where racial divides, the importance of family names, and the Colored school’s existence was in one place. Finally, the community protected and shared its own stories, which helped the community maintain a completeness sense. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Emergent Themes on History of Racism and Slavery.

Slavery

Some discussed the community’s historical connections to slavery. For example, Olivia stressed the self-sufficiency and freedom of generations of some neighborhood families. “True African-American history that I left because—Okay. We didn’t all come here as slaves. Some of us were slaveowners. Some of us were born free, I’m an independent woman. Ancestral chart tracer, Olivia’s research service. And I did research and had my own business. Started after college. Then, I had clients that send me orders in from all around. I would go to the courthouse and do a lot of research at the courthouse. And they let me go through old files and everything. And we all live together, races of people, poor races, because it was poor folks in all races.”.

Furthermore, Molly (white female) recalled how Juneteenth served to help teach the local history of slavery: “I know it was after Juneteenth at that point. (Interviewer: But did, did you know if there was any slavery within that neighborhood at one point?) No, I don’t think there was ever any slavery here. I found out quite a bit later that some of them worked for the white people, but they, you know, went back to their neighborhood. They didn’t try to do anything with people other than working with some of the people.”.

Segregation

Stories of segregation also emerged from the counter-life stories. The community recalled how segregation affected different aspects of their experience.

Olivia remembers that the neighborhood was known for being Black. “Dunbar used to be called Colored town.”.

Molly (white female) described learning about segregation and racial division through signage and social landmarks. “No Black people allowed. I don’t know, as a child when we’d be driving someplace, I would see a sign, and when we get into the town, I don’t remember what I called them. And anyway, it said no Black people allowed. And I asked my mother, why does it say that? And she just said, well, it’s just the way it is. She never explained. And well, you know, I like to know reasons for things and why things are like they are. And my mother, I don’t know if she thought about it or just didn’t think a child would understand or what, but she just said, it’s just the way it is. And so… then when we came here and we were like, wait, there’s Black people, there’s Brown people here, but they’re all living in different communities. No, I wasn’t just curious as I just… Well, I wanted to meet all of them, but I thought you can’t have a community with separate communities within it that don’t work together and do things together.”.

Molly also described the particular challenges of finding her place as a community member amidst segregation and racial division, even in this small community. “In 1966… when I moved here, I could see it looked like three communities all in, in the area that was supposed to be San Marcos. And I couldn’t imagine why the Black people would be into themselves. They had their own businesses, their own organizations, their own housing area and so on in that area. And then real close were Hispanic people and they had their own things. And the white people had their own neighborhood, you know, it’s just, they were all separate and I couldn’t imagine living in a town with three distinct groups of people that did nothing together. They didn’t know each other at all, you know. And so, I started going into those other neighborhoods. and that was in 1966, to see people and… When I could, I would talk to them and try to get acquainted. And so, after I’d made some friends in each area, I started trying to get them to go with me to things that I was going to. Well, at first they said they couldn’t go. And so, I thought they had something else scheduled. And finally, gosh, Lord, I realized they just didn’t feel like they’d be accepted because they never had been. They didn’t, didn’t try to get in anybody’s group.”.

Morgan described how segregation affected education in the small community. “The two and a half miles outside of San Marcos… I was raised on that. [I recall] life growing up in San Marcos and going to the Colored school in San Marcos. I think the one thing that comes to mind was the one time the K.K.K. burned down the old school building.”.

Meredith remembered integration through military experiences and unspoken rules of community behavior: “And, um, what happened is when the military—they integrated the military—then they didn’t have housing for the military personnel. [Right, right.] For those neighbors, there were Hispanic people who lived there, um, across the street and there were whites too. So, you have to understand that even though, uh, there was a mixture, everybody knew their boundaries. Each community—because you have the south side—they actually had their own school, which is the South Side School, which I think they still maintain. Dunbar was our school, and the boundaries were set by the parents. The kids wouldn’t set the boundaries because a kid is a kid. They’re—they’re not looking at, uh, color. That’s something that’s imposed upon them by their parents or by their environment.”.

Integration

The community also remembered how integration affected their education. Olivia remembered her experience during school integration: “I was the only little colored girl in the whole school. And that’s when they hugged me—and I realized the only difference was the pigmentation of the skin. We all the same.”.

Paula shared her own school integration stories and her short-lived experience in the segregated Dunbar High School: “One not two weeks. She went to school here [Dunbar High School] two weeks and then they integrated two schools and [Oh wow.] Two weeks. Yeah, that’s what she said. But I went to Dunbar for two weeks. Quite the reunion. Yeah. Huh… like the kids would always play together anyway. And so, when the schools were integrated it was like, Oh.”.

Laura remembered integration through her experiences at school. “So, I know I had a different experience than—than my sister. For one thing, that I know a lot of my friends. We had a mixture. We had more Blacks in my class than—than I know she did, and even when I went to college. Um, but like I said, when I was small, uh, I went to Dunbar, and I think I might’ve went to the second, no more than the third grade, before integration, year would have been at ’61, ’62.”.

Flooding as Environmental Racism

That the community was permitted to build and function on a flood plain meant they suffered natural disasters that affected their resources, construction, and development.

Molly reflected on the history of development in the community. Limited resources meant neighbors had to improvise home improvements when floods and fires ravaged the neighborhood. Local government officials offered partially improved housing conditions. Molly suggested that systemic racism played a part in ineffective rebuilding efforts (history of racism). “Well I’d to say, I would say it would be about maybe 1976, something like that. So, when I first arrived in that neighborhood, there were a number of older small structures that were just like shacks that were throughout the neighborhood. And let me tell you how bad they were. When I found out they were single wall construction, with no floor, but there was a dirt floor. You know, a shotgun house that sat down on the ground. And so, they were always looking for a board to replace something, and it rotted out or something like that. And they would glue newspapers and magazines articles to the inside wall to keep the streetlights out. That’s how bad the housing was. The housing was really bad. And so, when the city started bulldozing them down, they just, you know, took them…Cause I, I think in the 1970s there was a flood as well. [Wasn’t it due to the flooding that they bulldozed them down or…] No, he just wanted to get rid of them, you know, Mr. Hood. [And what was his position?] The city manager. And I guess he did several things. I don’t remember what else.”.

When the city manager was dismissive of the bad housing conditions, Molly intervened and volunteered to become a licensed contractor to help rebuild the community’s failing homes. She spearheaded an effort to raise support and acquire lumber and materials to provide replacement homes for residents in both the Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in San Marcos. “And so, I found out that the city manager was condemning a lot of the very substandard housing that was here. It was substandard. And when I went to help people with anything, I did not try to meet in their homes. I thought it just embarrassed them. And so, I would meet them somewhere else, but I could see just the outside of the House. It was really bad. And so, when I went up there to talk with the city manager about that or anything else. Well, I asked. Oh, he started bulldozing loose, very substandard houses down, leaving the people on the street with no place to live. And I told him it is your responsibility. You are the one taking housing out. You already removed them. And then, so now, he was not going to do anything. And so, I thought about it, you know, went home and thought about it for about two days. And I went back to talk to him again, and I told him I have an idea that can help us. So, he put his papers down to see what I’m going to say this time. And I said I think that volunteers could be brought to San Marcus to build houses for the people. And he sat there a little bit, and he said, who’s going to get new? Who’s going to get volunteers? And I said, well, I’ll get the volunteers, no problem. And since I was doing things all over the country, not just here in San Marcus. And so I said, I’ll get the volunteers, so he didn’t say anything… And so as the people came, I would talk with them, tell them what to do and how to do it. And I’ve checked on it all the time, and I’m like, sure. They were following the rules, and that’s how we changed the housing stock in San Marcos. After I did that five years, I decided I know so much about construction now just start my own construction company. So, I ran out about 20 years before I shut it down and quit doing that.”.

4.2. Impact of Environmental and Social Racism

Residents recounted how environmental and social racism impacted their lives and livelihoods then and now. They talk about how racism affected their education, sense of place, and community. Furthermore, they talk about how environmental devastation led to issues with taxation, urban renewal, and gentrification. A form of gentrification is evident in the community that was once called “Colored town.” In-migration and outmigration are related to external variables such as taxes, urban renewal, and home and property values. They also talked about how Black businesses served as a resource for the community when segregation deprived them otherwise. It is important to note these experiences as a true reflection of the Dunbar community by residents who once lived there. Schools were a significant site for personal experience of national integration trends. Further, in the following quotes, we added bold for emphasis. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Emergent Themes for Impact of Environmental and Social Racism.

Flood Relocation

The community faced challenges with flooding since “The Purgatory Creek watershed continually threatened the area with flooding” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996, p. 12). In the early 1970s, Dunbar experienced some of the worst floods to hit the area that destroyed many homes. In response, some homes “were simply moved into the area rather than new construction replacing homes washed away by the waters” (p. 12). Repetitive flooding led many to relocate from the community, sometimes coerced to do so by urban renewal efforts. It also led to relocation into the community as property values and taxes changed.

Fred described relocation in the neighborhood due to flooding. He describes how families moved in, but mostly out of the neighborhood, and how natural disasters and other dynamics accelerated the outmigration. The more problems, the more outmigration: “Urban Renewal came through and bought out a lot of places—And relocated [homes], and all that. I was one of the ones that didn’t relocate. But it wasn’t as bad. It wasn’t as bad. And… well—I’m gonna contradict myself. It was and it wasn’t. Because it was bad. It was bad enough where sometimes down the road it would back up. A while back, uh the flood took away, uh—uh I think it was two little—two little girls’ lives. In that flood, that was off of Mitchell Street. And uh—uh, it was uh, it was a family left over there. Uh, last name Smith. It was two twins. James Smith and George Smith. It was in uh—uh. It was the Masons. Uh-huh and uh, I think that it was their grandkids um because the water came all up and flooded them out. Right where the Black Church is over on Mitchell. Well, across from that, where there ain’t nothing but those apartments –The signage was next to it, where their House was and everything … and water came up out of that creek. It was all over Broad Street. And it was all up there, and they had to go out in boats and stuff. So it was—it was a—it was a couple—a couple of lives—lives lost during this time here—during that time. Well, uh I was in my teens when this happened. This is what I’m talking about, I hadn’t got to my teens yet, you know. ‘I was’ right at my teens, you know. I was about 10, 11, 12. [Right, right, right]. But it was—it would get up close but it never did get in—get in there. Never did get in. But it did a lot of ‘damage’. I guess all these other buildings and rearranging and doing this and that and doing street work and different things kind of changed things where water started coming up… around that. [Right it’s gotten worse.] During the time when Urban Renewal came in the Beat was—they was closing—they was shutting down. That’s right. That’s right and you know, they, you know, rat infested, and you know, got the roaches and stuff. They needed to be torn down. Well, um they should have and needed to. If you can’t afford to do something on your own and redo this sitting up there, okay. Well, somebody say okay. Well, look here. Just get out of it. Just demolish it and put you in a better place. [Right.] They didn’t just put ‘em out in the street.”.

Gentrification

These same conditions—flood plains that damaged homes and reduced property values—also primed the neighborhood for gentrification. Gentrification is evident as new development and increasing tax rates price locals out of their community and redirect attention and funding from restoration and preservation of local fixtures and landmarks.

Meredith described the current integration and gentrification of the community. “Yeah, because she would—she actually lived in this house—shotgun house—down here on the corner, and I—I think when I first came back and I drove by there and I seen a white person, I was like, ‘No, can’t be, because that’s Miss Sanso’s house—Miss Sanso’s house.’ So, [clears throat] that’s what we have noticed, is that these homes that were occupied by nothing but Black people are now Hispanics or whites are coming in. Very few Black people left. Very few Blacks who are living, uh, in the area. I know that some have moved out and gotten larger homes or, you know, and whatever. Uh, what was the up and coming neighborhood where the Blacks were—? Not that it was all Blacks. It’s just that they started building homes over there.”.

Laura described migration changes in the community and increases to the tax base. “Some of the old people have died. I’m sure, for whatever reason, they either lost their homes or kids sold it, so that’s why you see different people coming in. You don’t see—you see a hodgepodge. You don’t see—you know? Just like on my street. I know when some of the old people have died, the kids, you know, may have been that they lost their [home due to] taxes. They just don’t take advantage of the things they have or appreciate it. What is important to me, I know is not important to my children. I—in—and that’s okay. I might, but I know that when I’m gone, they could care less [to] not have these hodgepodges because when they do that, that’s when my taxes go up. And that’s what they do: they tax you out. This is my home, and it’s not for sale.”.

Paula described current issues with tax and property values that pressurize neighborhood economic stability and plague community members: [Taxes and the property values increasing. Has that happened to you or?] “Uh, yes, it happened, but, um, I tell my daughter all the time, I said each year it seemed like they’re going up, you know, and, and it’s high, but you gotta do what you gotta do. And I, I, like I say, I have property on, on John’s street and I have a lot with two houses there. But thank God that I have them rented out. And um, and then I had property on Centre street and Endicott street… So, by the grace of God, I’ll make it nice. [Are you able to hold onto it?] Um, so much taxes on my, on the property down here. And then you go right up on San Antonio Street and they are not as high as they are. And I had one lady that give me her tax, um, slip because her kid goes to school up in the Crockett area, and uh, she said this is so unfair that you are in a mobile home. And I you have a brick home up here by Crockett and you’re paying low taxes. And she said, I’m going to give you my tax statement because this, this is just bad, and I just wish we could do something about that. But I don’t know. I keep telling my brother, come go with me when it, when they had that, uh, what’d you call it? Uh, uh… it’s not a tax statement… Oh, you can protest your taxes. Yes… I said come Google it for me next year, then I want him to go with me.”.

Black-Owned Businesses

On the other hand, neighborhood flight and in-migration has also benefited some Black-owned businesses in the community.

Robert shared how Black-owned businesses were essential because, as a segregated community, Black neighbors had to do things for themselves and one another. They were an important fixture and landmark for the community. “Down the street at the end of M.L.K. Drive on the right where the telephone company is, from that point all the way back to that Black Baptist church was two-story and three-story buildings that was all Black businesses. It was pool halls, uh, barbershops, uh, domino shacks. And then across the street on the corner where that building sits, where it was once the Dairy Queen that’s sitting right there, was a Black service station owned by Blacks. And then right up there on Endicott on the corner right, up there was all Black hotels owned by Blacks. Then the stores up here, we had our own Black stores. We had everything. This neighborhood was all-Black only.”.

Paula shared about the importance of land ownership in sustaining families and the community. It also informed family and community activities and practices. “My daddy had a big enough acreage that he grew all of our own crops. He [grew] corn and watermelon. Uh, he grew—he even had cattle, so we did not have a need to go to the grocery store for many things because my mother made, uh, home butter. Uh, our milk came from the cows. She would pasteurize it by boiling it on the stove. Um, and even as kids growing up, and we had chores, which included on the weekend making butter, uh, helping out in the fields. I know my brothers did a little more because they had to get up earlier to milk the cows before they went to school.”.

Olivia described how a family business also contributed to the community’s economy and resources: “My grandmother lived down the street, and, uh, she had her own business. She—she did, uh, washing—and all of that, and she had her own washing machine, and she had people that come in… She would do their laundry. Dunbar was—was a thriving neighborhood. Uh-huh. And my uncle came back and taught at Dunbar Junior High then, and then Dunbar High School. There were many educated people and -business owners and successful people in Dunbar. They said they could move me to a better location. I don’t wanna be moved to a better location. I wanna stay right here. Dunbar is the place you wanna be.”.

Government and Aid Programs

Despite segregation policies, the area flourished until after World War II. This decline is mostly attributed to G.I. Bills and V.A. loans that allowed residents to move into the suburbs and other aid programs that changed the neighborhood’s dynamics.

On the one hand, government and aid programs inspired locals to leave. For example, Robert reported that Gary Job Corps brought trouble to the neighborhood. He described how local businesses and national social programs and organizations were resources and a part of community identity. The story illustrates how national and local resources supplemented and strengthened the neighborhood: “Gary Job Corps came in. When Gary Job Corps came in, it changed the whole dynamics of this town because a lot of people start getting employed but they had kids that was coming in that was in their 30s, gangsters. So, when Gary Job Corps first opened, they was walking these streets and messing with people and stealing and doing all kinds of stuff. So, they made it to where Gary Job Corps students couldn’t come to town for a while. Then they changed the age limit from 17 to 21 or 25, whatever it was, to where those hardcore people—see, they were bringing them from New York, Chicago, all the major cities where they was gonna go to jail but they sent them to the Job Corps. The Job Corps, the biggest one was this one. So, they sent them down here.”

On the other hand, other forms of aid provided resources for those who stayed. Meredith remembered financial security brought by federal programs such as the G.I. bill and her family’s strong work ethic that helped contribute to neighborhood resources: “And, um, my father was a carpenter by trade. He had been in the military. Um, a segregated, um, military. And a part of the G.I. bill is that when he came out, he went to school and came out a—a cabinet maker. So, that was the carpentry part.” Overall, the residents’ industriousness, the focus on community, and the influence of neighborhood educational institutions all point to Dunbar as an autonomous, self-directed African American neighborhood.

4.3. Rebuilding and Restoring the Community

This theme reflects neighbors’ desire for community beautification, restoration, rebuilding, and recognition of possibility and promise for the Dunbar community. Five out of eight participants would like to see the Dunbar community recognized in the future in terms of its history. The Church represents the haven it had for the community in Dunbar. The churches in the community represented a constant union for city members. The Church was a site of gathering, education, and resources. Churches reinforced a sense of place and faith for community members. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Emergent Themes for Faith and Sense of Place.

Faith

The churches in the community were essential to community faith and strength, a theme shared by this and many African American communities. Laura described the importance of Sundays in the community: “When I got into an organization in school, and maybe we had bus transportation and cheerleading. I was a cheerleader and was very active in high school because my parents were okay with that. Their things were, you have your friends at school. But our friends didn’t come home with us. You came home to—‘to work because I’m working, and there’s chores you need to do’. So, we didn’t have the luxury of hanging out. Sunday was our relaxation day, more so at home. And then, uh, I remember the holiday theater used to sit up on the square. And my dad, when we got—we didn’t have cell phones. We had in our House a par—uh, what they call a party line. I still attended Jackson Chapel United Methodist Church. I still came to Church, so I was still here, but I just didn’t live in the Dunbar area because I had my own place.”

Olivia described how faith provided strength: “We all have service at the Church. God is with us. He’s taking care of us.”.

Molly felt a sense of fulfillment by helping others. She wanted community members to feel more empowered to do things for themselves. She expressed her pleasure in helping others: “Well, you know, it brings a lot of pleasure. When I helped somebody else, I can see how it changes their life or how happy it makes them or whatever. And that makes me happy too.”

Sense of Place

The Church not only fed neighbor’s souls and uplifted their spirits; it also provided a sense of place and home in the community. It was the site of resources and aid. Other landmark buildings also provided a sense of place and belonging in a neighborhood where flooding and fire threatened landmarks and livelihoods.

Olivia described how buildings helped anchor family and identity in the community and how the buildings’ proximity made community members close. She also described how the community perceived family structure: “I was born in Seguin. Right and when my family moved here I wasn’t even a year old. Yeah, I wasn’t even a year old. Uh I was raised up here. [I was born in] 1942. Sure, I can remember back when I was um, you know, six years old. Considering you know—no complaints. [My family lived] right here. There was already a structure here and uh then my grandmother had it rebuilt. I guess I was around, maybe 10 years old. Right, she raised me. As a matter of fact, you know, she raised me along with my mother. Okay, the [House] across the street which belonged to the Jacksons, they had a bigger house. And it was a bigger family. Uh, me and my friends used to go in the evening times at night while he was building it. And we used to hang out over there. Uh, because my friends were related to the Jacksons. I was raised up with them—around them. [We were] about the same [age]. Okay, uh, next to the crossroad here where the Perkins live now, well it was the Jackson family there. That Jackson family came out of the Jackson family across the street. Okay, it was—it was one of the sons, his name was—his name was Ed, Ed Harris.”.

Olivia describes how the aging community cannot circulate through their neighborhood as they did before. “And, we don’t visit anymore like we used to. I don’t know. I guess because a lot of us are getting older—and don’t go up and down the neighborhood like we used to.”.

Recommendations for Revitalization

Finally, the community members offered recommendations for overcoming the challenges of their past and present in the future. See Table 5.

Table 5.

Emergent Themes for Revitalization.

Fred recommended revitalization: “In terms of the neighborhood and the researchers, if we’re working with you all, what should we do with that history? Like what can it be used to do for the future? Is this something that belongs in the past or is it something that needs to be carried forward in some way? It should be recognized… a bunch of ways you can recognize it, you know, a bunch of ways you can state it. And, you know. Your choice. Your choice is my rejoice. Whichever way you wanna do it. Put it in a book if you wanna. That’s fine for me. You can’t reconstruct it, but now you can kind of, but you have to put some things here, just use some different things—well like they’re selling everything, have the building.”.

Laura recommended preservation. She recommends closer intergenerational ties in the community to help preserve history and educate newcomers about the neighborhood’s history, including visitors from event tourism for weddings and events. New construction is an essential factor:

“They don’t take the time—to, I guess, to kinda bond and get those type of—of relationships that we—that the older generation had back—back when I was growing up. I’d still like to see it be the Dunbar—be known or have things where people can read its history—of the Dunbar that would—that—that it originally came from, even if it’s not all of it can be preserved. I would like to see that it—that the neighborhood if it does change, changes in a way that whoever comes in, they would know about the history of where—what was in the past.And then maybe try to preserve—try to preserve as much as we—as much as we can. The restored community center where people in the neighborhood could either use for whatever events they wanted to have or have, um, have things there for that would be for the community. Where they could be updated on things going on in the community, where they could, um, they could have community events—weddings or whatever they needed to do. But for—things for the community that were—that would be centered around that community and this area. The Dunbar area. Sometimes you can’t—you can’t stop the change. Um, Dunbar’s—they got—I’d like to see the original place stay there in the end, but then again, I know that even they’re doing construction. It seems a block is building a new road. People are going to—it’s gonna be different, and I can’t stop that change unless someone just ha—halted. I mean, we came back to live. Say I came back to live over in that area, um, I could not see it, but I could—you know? But, uh, i—I mean, there’s nothing there that I could live in now. I would have to build something new if I came back here—to the neighborhood.”

Meredith recommended beautification: “We need to see the beautification of it. If there was something that we could—we—we’re really stressed for funds because we have to depend upon the Methodist church is really not going to extend us a very big hand—to do the renovation or rebuilding. They’ll send us through the changes.”.

Molly recommended community members helping each other more. She wants community members to feel more empowered to do things for themselves. She was interested in the skills and tools for the community to document its history:

“I think helping people, Black people you’re talking about, realize that they have potential, that they have skills, that they can do things and become authority like you are…and you know if you can help people gain confidence in themselves and learn how to do things if they didn’t know how before or though. So, they realize that they can do things and they, they can do great things.”

5. Conclusions

Our findings reveal that the counter-life stories (lived experiences) of residents and congregants in the historically African American Dunbar neighborhood after the Civil War counter the mainstream narrative about African Americans’ experiences in Dunbar in a few ways. First, while the official story downplays the role of slavery, the counter-life stories reveal that Dunbar residents and congregants are cognizant of slavery in their neighborhood’s history. They also carry memories of segregation and integration that persist in viewing current trends of gentrification and outmigration. Second, the historical records overlook the impact of environmental racism in permitting the Dunbar neighborhood on a flood plain where flooding persists as a challenge to development and property values. Third, the historical record portrays Dunbar as a cohesive part of the San Marcos community. However, the neighbors themselves are still hoping and waiting for restoration and development that the rest of San Marcos enjoys. Indeed, racism and slavery inform community history to the point where current issues such as property tax troubles are viewed through the lenses of the past by the community. Environmental and social racism impact community identity by contributing to in- and out-migration, which has impacted how the Dunbar community addresses its needs and finds resources. Finally, rebuilding and restoring are priorities for the community, but doing so in a way that respects and honors their legacy and heritage.

What began as environmental racism has grown into a systematic issue for the Dunbar neighborhood. Early African American families were allowed to live in San Marcos along the Purgatory Creek floodplain as this land was not considered desirable for white settlers. As small enclaves grew in what is now known as the Dunbar area, “The Purgatory Creek watershed continually threatened the area with flooding” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996, p. 12). As time passed and the city did not provide for the African American population, the first African American men to own property in San Marcos were five individuals who purchased land for a cemetery in 1893 to dispose of the dead outside of the floodplain properly. In the early 1970s, one of the worst floods to hit the area occurred, and instead of rebuilding new structures, “… there is an indication that existing houses were simply moved into the area rather than new construction replacing homes washed away by the floods” (Knight Newlan and Associates, Inc. 1996, p. 12). The result of this move is that these structures became increasingly unstable.

Additionally, many existing historical buildings were destroyed that were either deemed unsafe or condemned. Little was rebuilt to replace what was lost. Along with the effects of flooding, older buildings that fell into advanced deterioration were not repaired and torn down. Current residents continue to suffer from flooding and damaged residences. In order for the residents to overcome the past environmental racism, provisions need to be in place to help prevent further losses. Currently, the needs of the Dunbar neighborhood are neglected.

Current and former residents of the Dunbar neighborhood in San Marcos, TX, shared that even though racial divides and issues of family belonging and ownership influenced life in their community, their community was a safe place to thrive despite segregation. Stories about community origins and history were interwoven and told through the lens of individual experiences. It was personal and familial values and standards of hard work and a strong foundation of faith and church outreach that kept Dunbar flourishing. Despite changes and challenges to the community brought by gentrification and tax issues, the lifelong residents remain a fixture and have ambitions to beautify and restore their community.

The lived experiences and counter-life stories of current or former residents, and current or former congregants in the historically African American Dunbar neighborhood after the Civil War demonstrate that personal and communal strengths make the community unique and resilient. Past in-migration in the 20th century introduced a new generation of committed neighbors and community members. However, in-migration in the 21st century has brought new issues with which the community struggles, including taxation, representation in the San Marcos community, and aging and community infrastructure deterioration. Issues of gentrification have also made it challenging for the community to preserve cultural assets for the local community center and museum. Outmigration has been the option that some community members have taken; for others, the answer lies in beautifying and revitalizing the neighborhood. Over time, the bedrock of personal and community values and hard work did not change, but external forces continue to affect the community and compel it to pivot and make plans for change.