1. Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is one of the most frequent types of domestic violence. IPV is characterized by various forms of abusive (physical, psychological, sexual), dominance and control behaviors perpetrated by one partner over the other in the context of an intimate relationship (

Burgess et al. 2010). IPV exists in all socioeconomic, religious, and cultural contexts/groups, regardless of sexual orientation, age, or sex, although an unequal gender distribution is recognized (

Burgess 2017); gender assumptions are culturally legitimated and influence individual and social discourses on risk as well as informing the policies and practices of risk assessment (

Walklate 2018).

Research on IPV has developed a recognition of the factors and processes that contribute to the key decision by victims of abusive relationships of whether to stay or leave their partner (

Anderson and Saunders 2003;

Barrios et al. 2020). This issue is particularly important in models and intervention strategies aimed at the recovery of the victim of violence (

Peterson 2020) and also contributes to the general health and well-being of individuals after experiencing violence (

Hamby et al. 2017).

The decision to leave an abusive relationship is very difficult for victims to make, because they must consider their own safety as well as the safety of their children (

Jones and Vetere 2017;

Peterson 2020;

Stephens 1999). The leaving process is complex and contingent upon numerous contexts, such as individual factors (e.g., clinical condition of the victim), interpersonal factors (e.g., support of their family, the needs and safety of their children, the severity of IPV), and community or sociocultural factors (e.g., the existence of victim support services, cultural beliefs about gender roles, coercive control, religious tradition) (

Barrios et al. 2020;

Domenech del Rio and Garcia del Valle 2019;

Estrellado and Loh 2019;

Jones et al. 2017;

Sears 2018;

Wilhelm and Tonet 2007). The process of leaving the abusive relationship is influenced by a series of micro and macro variables that affect each individual. The process is more abrupt for some victims than for others. The decision may arise in different stages depending on the weighting that different aspects contribute to the decision to leave (

Enander and Holmberg 2008;

Khaw and Hardesty 2013). Some victims face great psychological difficulties during the decision-making process to leave and/or after leaving the abusive relationship, and their condition may worsen over time (

Anderson and Saunders 2003). Therefore, it is important to know the factors that can affect the decision to leave, as well as the predictors of victim well-being, so that when there is a request for help, the planning for an intervention can consider various factors that can help the victim face adversity, particularly their resources and strengths. We note that some studies in this area recognize the importance of such factors, but do not present them within a model or go on to discuss how they can inform interventions with victims of IPV. This work intends to fill that gap.

This article presents an empirical qualitative, descriptive, and cross-sectional study, which observed the experience of victims of IPV who are mothers. Based on the narratives of victims, the research identifies the main factors underlying victims’ decisions to leave abusive relationships. We find that these factors are also fundamental for consideration in the victim support process. After a brief literature review on the issue of leaving an abusive relationship, we focus on the elements of The Resilience Portfolio Model (

Grych et al. 2015) to reflect on the process of psychosocial support to victims of IPV. Based on victims’ experiences, and through the use of a qualitative and participatory (grounded) research approach, we move toward theory. Although not an exhaustive consideration, we attempt to underline the importance of psychosocial intervention in this area.

2. Reasons for Leaving the Abusive Intimate Relationship

For

Gelles (

1976) three important factors must be observed: (i) the severity of violence (the less severe, the greater the tendency to stay in the relationship); (ii) history of childhood abuse (such a victim is more likely to remain in the relationship); (iii) material resources of the victim (the fewer resources, the more likely they are to stay).

Rhodes and McKenzie (

1998), reviewing three decades of studies, concluded that although some of these factors may be important in the decision to leave, the results are contradictory or unclear and that other variables can be considered, for example, individual factors (e.g., personality characteristics, self-esteem, psychological effects of the abuse). However, many of the studies reviewed by these authors were mainly concerned with recognizing what was wrong with the victims, rather than focusing on the behaviors and attitudes that can favor the leaving process. We corroborate the opinion of

Rhodes and McKenzie (

1998) when they conclude that there was a tendency to look for a theory that fits all victims and not to try to understand their inner worlds and patterns of behavior in their relationships. Likewise, we support the position that interventions should be tailored to fit each case, attending to the individual experience of each victim of IPV, as advocated by other studies (

Khaw and Hardesty 2013).

Anderson and Saunders (

2003) mention two broad categories of predictors for leaving an abusive relationship: material resources (e.g., employment and income) and social–psychological factors (e.g., history of childhood abuse).

Khaw and Hardesty (

2013) theorize that sociocultural factors intersect and interact with individual factors (e.g., informal social support), and the interplay of these elements creates unique circumstances affecting the victim’s access to formal support resources (e.g., the police) and the strategies they choose to engage in leaving. We prefer to refer to the existence of intrinsic and extrinsic factors to the victim if we consider the conceptual classification of locus of control (internal vs. external) (

Rotter 1966) that can determine decision-making.

Baly (

2010) underlines the importance of analyzing the victim’s narratives. Through a qualitative study with women who had abandoned abusive relationships, she concluded that meaning-making about the abusive situation was influenced by social and cultural discourses in different ways: some constructions reduced the victim’s ability to deal with the situation, while other discourses encouraged a self-construction of personal strength to leave the abusive situation.

We need to highlight that the decision to leave is the result of a process that may include several phases, during which the victim learns how to face the adverse situation of IPV. The process is multidimensional and variable: some victims first prepare a cognitive and emotional leaving (with primary recognition, resistance, and risk management) before the physical leaving (already aware of their own needs) (

Anderson and Saunders 2003), while others may experience a faster cut of the abusive relationship. Preparation is more than just a step within the larger process of leaving that must be actively planned (

Bermea et al. 2020). Closer to the decision to leave, some factors can be decisive (e.g., the existence of family or friends support) and even after leaving the relationship, other factors continue to contribute (e.g., education of children), which may reinforce the decision to leave or may compromise it, resulting in a reversal of the decision. For example, motherhood can be a source of empowerment, which helps victims care for their children and survive abusive relationships, or a source of pressure to leave abusive situations (

Jones and Vetere 2017;

Sani et al. 2020;

Zink et al. 2003). The dissonance between wanting the best for their children and fearing the involvement of child protection services hinders decision-making by victims of IPV (

Sani and Carvalho 2018;

Zink et al. 2003) and thus should be considered in planning for supportive interventions.

After leaving an abusive relationship the victim needs practical assistance (

Anderson and Saunders 2003). For example, how will the victim ensure their psychological well-being in the post-separation period? This is a question that professionals who are in the line of support to the victim necessarily ask, even before the abusive intimate relationship ends. This reinforces the idea that leaving an abusive relationship is a process that begins before a decision is made and does not end after the decision to leave. Therefore, various intrinsic (e.g., meaning-making, self-regulatory) or extrinsic forces (e.g., social support, material resources) on the victim need to be identified and worked on to protect against negative psychological outcomes. Sometimes the same factors that are identified as predictors of leaving are variables that require additional work to enhance an effective support intervention for victims of IPV (e.g., the existence of young children, recognition of informal social support).

Finally, based on the results of our study and considering the implications of these for the intervention process to support victims of violence, we will defend the adoption of a positive approach centered on the search for the individual’s strengths, which can also be found in a model that we will present below.

3. Intervention with IPV Victims: Three Components for Resilience

Research on victims has enabled important developments to be achieved on interventions to violence and crime (

Hamby et al. 2017;

Sani and Caridade 2016,

2018). In this context, a paradigm shift has been advocated that allows a better understanding of violence, adopts an integrated approach to the phenomenon, takes into account the risk factors (static and dynamic), and also considers the mechanisms that underlie violence and victimization (

Ahmadabadi et al. 2018). Accordingly, intervention processes must focus on the identification and promotion of the strengths or skills evidenced by individual victims (

Hamby et al. 2017).

In the following, we briefly present The Resilience Portfolio Model (

Grych et al. 2015), a conceptual approach that aims to identify the poly-strengths or protective factors of the person that can contribute to their health and well-being after exposure to stressful situations. According to the model, there are three major strengths associated with well-being: self-regulation (ability to sustain motivation and overcome obstacles while striving toward a goal); interpersonal forces (social support); and meaning-making (capacity to find meaning in difficulty). The gathering of forces from these three functional domains can promote the necessary resilience for the prevention of violence and the development of well-being, as demonstrated in some studies (e.g.,

Banyard et al. 2016;

Taylor et al. 2016).

In this model (

Grych et al. 2015), sometimes the factors that promote a person’s resilience are simply the reverse of the risk factors (e.g., the non-existence vs. existence of a recognized support system); however, an effort is needed to search for the multi-forces that may be more implicit. Additionally, a more positive view of the goal of the intervention process is that it would be defined not by the absence of pathology, but by reaching levels of well-being and health. In the domain of intervention with victims of violence and specifically the decision of staying in or leaving abusive relationships, this model has particular importance when assuming decision-making as a process in which the identification and mobilization of protective factors contribute to the victim’s well-being (subjective evaluations of satisfaction).

Following the tradition of research supported by qualitative approaches that underline the importance of understanding individuals’ experiential reality, this study aims to contribute to the knowledge of factors associated with leaving an abusive relationship, and on this basis we reflect on interventions in support of the victim of IPV.

4. Methods

4.1. Participants

The sample was constituted through intentional sampling, respecting ethical and deontological principles, and utilizing the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: (i) being a user in a follow-up session at the support entity collaborating in this study; (ii) being female; (iii) being a mother; (iv) being over the age of 18; (v) having direct experience of domestic violence by an intimate partner in a heterosexual relationship; (vi) having mental functional autonomy (vii) not being at risk of violence and/or being physically or emotionally fragile; (viii) not showing cognitive limitations that make it impossible to understand the study; (ix) not revealing any dissonance, embarrassment, displeasure, or any kind of pressure that interferes with free and informed consent.

The sample size was defined through a theoretical saturation criterion (

Fontanella et al. 2008), which led to the voluntary participation of 15 Portuguese mothers (cf.

Table 1) that were victims of IPV in a heterosexual relationship and who decided to leave—on their own initiative—the abusive relationship and who also requested/received support from the Victim Support Office (VSO).

The women were aged between 29 and 71 years old (M = 47.9; SD = 12.0) and almost half (46.7%) had a basic level of education. The sample is heterogeneous, covering several educational levels and types of marital status (five married, five divorced, and four single women and one widowed woman).

4.2. Measures

For data collection we used (i) a sociodemographic questionnaire to collect personal data and (ii) a semi-structured interview script, constructed after a literature review and professional consultation in the area. The script used in data collection had nine questions and is part of a broader research effort that is guided by two general objectives: (i) to understand how women victims of domestic violence conceive their role as mothers and their parenting skills (e.g., how might violence have affected parental function?) and (ii) to understand why these mothers decided to leave or stay in the abusive relationship (e.g., what led you to leave (or not) the relationship?). In this article, we focus on this second objective and explain the reasons why these mothers and victims left the abusive relationship and sought help from a non-governmental organization that supports victims of domestic violence.

4.3. Procedures

To begin, we requested formal authorization from the VSO to contact users of the institution who expressed interest in participating in the research. In parallel, the research project was submitted to the University’s Ethics Committee for advice and recommendations.

After collecting all authorizations, we began the study following the recommended ethical and deontological principles. All data and information collected during the investigation were stored on a computer within the VSO, accessible only by a code provided to the researchers. The interviews were conducted in the presence of a VSO psychologist during their planned appointments, with data collection limited to the selected instruments. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, its procedures and also relevant issues of anonymity and data confidentiality; following this, they signed the informed consent. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min and were audio-recorded.

The data treatment and analysis procedure was predominantly qualitative. Data from the interviews were fully transcribed and then subject to qualitative analysis, giving rise to the categories and subcategories of analysis. To this end, we used an interpretive and inductive method of data treatment, based on the strategies of grounded theory (

Charmaz and Henwood 2017), according to which the categories emerge from the subjects’ narratives, their experiences, and the meanings constructed. Thus, taking a “sentence” as a unit of analysis, we proceeded to categorize it according to the semantic records. To ensure the reliability of the results, steps were taken: (i) saturated coding of all the data collected through the analysis was carried out independently by two researchers (the field researcher and an experienced supervisor); (ii) joint dual analysis was performed, based on designations emerging from the participants’ narratives, via a continuous debate to scrutinize categories; (iii) inclusion of a third researcher to establish an agreement between the two coders in respect of the final designation of emerging categories and subcategories.

Table 2 shows the categories and subcategories that resulted from the qualitative analysis, expressing the reasons why mothers who were victims of violence remained in the relationship and the reasons that make them leave the relationship and ask for help.

5. Results

5.1. Category A. Reasons for Staying in an Abusive Relationship

A1. Shame. Shame appears as one of the reasons that these mothers/victims present for having remained in the abusive marital relationship. They say that revealing to their family or society that they were victims of violence was something that embarrassed them; they chose not to report, or request help in ending, the violent relationship, eventually accepting the consequences of it—“But at the time it was a shame to be a single mother, so I had to get married” (P1); “I didn’t go to the hospital and I should have gone because my nose was uneven and I didn’t go because it meant showing my face, so my parents would find out” (P4).

A2. Marital commitment. The idea that marriage should be something that lasts forever has led some of these women to postpone the termination of the abusive relationship for a long time. Divorce was seen as negative and therefore completely rejected, anticipating that, once separated, they would not be able to rebuild their life—“I myself thought, years ago, that whoever is at home is forever” (P1); “I never got divorced … I don’t know … we had been married for many years, we had a good life” (P5).

A3. Fear for her children. The psychological pressure to stay in the relationship may arise out of fear that something negative might happen to the children or because of fear of being accused of distancing them from the father, harming them even more—“I no longer wanted to be with him and I would have ended it all, but he said such bad things, and about our son, and I felt so bad that I went back to him” (P9); “I was married to him for 12 years and I let a lot go because of my daughter. I was afraid that my daughter would miss her father” (P14).

A4. Belief in partner’s behavior change. Despite the suffering they went through, some of the victims remained in the abusive marital relationship because they liked their partner and hoped that he would change his aggressive behavior, and, in this way, their relationship would have a new beginning—“I asked for retirement, with the intention that things would improve. I thought that when I was at home it wouldn’t happen that much … but no, it continued” (P1); “I was separated from this person for 3 years, but I came to believe, accept and forgive, and before I met a new person, I thought I would give him another chance” (P4); “In my thirst for ‘this time everything will be fine’, I let things happen” (P13); “This started badly, but I liked him so much that I tried to make the relationship work” (P15).

A5. Economic dependence. For some victims, lack of economic capacity is an obstacle to ending the marital relationship. Factors such as low wages/pensions and lack of employment were identified as important to not being able to support a home with their children on their own without the financial support of their aggressors, thus subjugating themselves to their abusive relationship—“I had nowhere to go, I have 300 euros of retirement, it was worthless” (P5); “I endured the relationship for a long time because of her, for my daughter, I had no work and nowhere to go” (P6); “I was afraid to separate from him, I was afraid to face everything alone, expenses, to support a daughter alone” (P7); “So when I get divorced, I have to leave. Now with 200 or so euros, how can I get out of there? I cannot! On top of that, I don’t work, I can’t get a job when I’m 51” (P10); “I don’t have the money to leave the house with my daughter and go to a new house” (P12).

5.2. Category B. Reasons to Leave the Abusive Relationship

B1. Family support/approval. Some women reported that the approval and family support they received were the factors that led them to decide to leave the abusive marital relationship—“The fact that my parents were here at the time, helped a lot, because I had no family support and, when they knew what was going on, they always helped me” (P8); “One day I spoke to my daughter, I explained the situation to her and she agreed with me. She said ‘mom, it’s better’. I was waiting for her approval to put an end to it” (P14).

B2. Intolerance/weariness of situation. Other factors that contributed to a victim leaving their abusive marital relationship were a growing intolerance to abuse and a consequent weariness resulting from their continuous experience of aggression by their partner—“I tried, fought, but one day I woke up and thought I can’t be like this. I couldn’t be a victim all my life” (P1); “Today I get a slap, tomorrow I have a knife stuck in my chest. I don’t want to be a victim anymore. My mother was also a victim; I didn’t want to have the same life as her” (P3); “I got to a point where I couldn’t take it anymore (…) until I couldn’t stand it” (P6); “But I couldn’t take it anymore and I ended up leaving. Things were no longer working out between us and the relationship was not healthy. I preferred to leave” (P9); “It was just possible to see the person he was with different eyes (…) when I discovered the things he did, my love started to turn into anger and disgust” (P13).

B3. Protection of children. Some mothers report having abandoned the abusive relationship to protect their children, because they felt that they were being harmed by domestic violence and did not want children to grow up in the violent environment—“It was no longer possible for my children to live in that situation, it was no longer possible” (P2); “Because I didn’t want my daughter to live in the midst of violence (…)” (P7).

B4. Children’s request. One participant revealed that the abandonment of the abusive relationship with her partner was due to a request from her son—“When I was assaulted again, my son asked to leave, and I said yes (…)” (P4).

6. Discussion

This study aimed to understand the reasons for staying in/leaving an abusive relationship. The results from the qualitative analysis were organized into two major domains (A. reasons for staying in an abusive relationship vs. B. reasons to leave the abusive relationship) that complement each other, being an integral part of the decision-making process of a victim of violence. We found that extrinsic factors (e.g., related to children, the aggressor, the society) reveal the existence of myths that can make it difficult to interrupt the cycle of violence, and thus it is important that they are considered in an integrated intervention when supporting the victim.

We verified how the fear of social exposure (to the family or society) of their situation was one of the factors that constrained victims from complaining and requesting help, and as a consequence, it contributes to the continuity of the abusive intimate relationships. The language used by participants revealed that fear of exposure to others was reinforced by socio-cultural factors. Society imposes meanings and representations on the women victims (

Jones et al. 2017). This is particularly true in the context of gender domination, which Portuguese women also experience through the process of socialization. We witness the individual internalization of cultural discourses that result in external effects, for the victim and for society, by sustaining violence as something normative (

Jones et al. 2017). This influences the social acceptance of the problem and affects the way victims talk about the aggressions they experience (

Machado and Dias 2010;

Sears 2018). Marriage for life and issues such as fidelity and modesty are conceived as eternal values to be respected, contributing to the maintenance of the abusive relationship (

Wilhelm and Tonet 2007). Divorce or separation are viewed negatively and as to be avoided, associated with a fear of social discrimination and a belief that it is potentially more difficult to rebuild normative family life in these circumstances, due to the lack of approval and support of family and friends (

Okada 2007).

Another myth that often ties victims of violence to the maintenance of the intimate abusive relationship is related to the belief that children are better off having a father than having no father (

Sani et al. 2020). Perhaps because of this, even though they experience a violent relationship and are not fully aware of the risks to their children, some victims experience the dissonance in considering whether or not to leave the abusive relationship, believing their children love both parents and thus that loss of a parent may cause them emotional damage (

Stephens 1999;

Zink et al. 2003). Consequently, the victim is often in a dilemma such that, in any of the scenarios, she will not feel able to keep her children safe by herself or even be able to provide them the necessary emotional support. Hence, the fear of destroying a family may appear as one of the factors that contribute to victims staying in the abusive relationship (

Narvaz and Koller 2006). This kind of thinking reveals the need for interventions to work on developing the self-regulation skills that promote victims’ ability to control impulses, manage emotions, and persevere in the face of difficulties (

Grych et al. 2015;

Hamby et al. 2017).

A belief that a partner’s abusive behavior is only temporary and that a restoration of family peace is possible can keep the victim in the abusive intimate relationship. In this context, the victim tends to hide her desires and delude herself in the expectation that her partner will change (

Wilhelm and Tonet 2007). This hope dissipates after various disappointments regarding his behavior (

Fonseca et al. 2012). The construction of new meanings (

Grych et al. 2015) about the permanence of the partner’s abusive behavior contributes to the victim leaving their abusive relationship and thereby regaining their self-worth and self-respect (

Estrellado and Loh 2019).

Economic dependence was mentioned by a third of the participants as a factor in their decision-making. The scarcity of material resources, combined with low job opportunities and the absence of financial autonomy, makes some victims afraid they cannot guarantee to economically support themselves and their children if they choose to break the relationship (

Wilhelm and Tonet 2007). Consistent with the literature (

Anderson and Saunders 2003;

Estrellado and Loh 2019;

Jones et al. 2017) some victims stayed with their abusive partners out of economic necessity, especially if they are unemployed. Shelters are not always a possible and desirable solution (

Sani et al. 2019) and in the absence of a safe alternative, staying in an abusive relationship turns out to be the option taken. However, if victims can use their interpersonal resources, alongside other intrinsic strengths such as meaning-making (

Baly 2010) and the capacity for self-regulation (

Grych et al. 2015), they can sustain their decision and prepare themselves to leave (

Bermea et al. 2020), for example, by getting a job (

Estrellado and Loh 2019).

Family support was found to influence the victims’ motivation for leaving the abusive relationship. According to the resilience portfolio model (

Grych et al. 2015), interpersonal forces are a determining factor in the victim’s decision to end a violent relationship (

Okada 2007). Such support is important for a victim of violence to be able to overcome the undesirable effects resulting from the abusive experience (

Levendosky and Graham-Bermann 2001) and to be able to develop other resources for their recovery. It is essential for the victim’s self-regulation and promotes their ability to deal with adverse situations (

Hamby et al. 2017).

Awareness of continued aggression and, therefore, the prospect that violence will persist over time, even across generations, creates a weariness and intolerance for the abusive intimate relationship in victims, especially where they fear for their own physical wellbeing or that of close family members such as their children (

Faro and Sani 2014;

Jones and Vetere 2017). The results of this study reinforce the idea that victims choose to leave the abusive relationship based on the best interests and protection of their children (

Edleson et al. 2003;

Sani and Carvalho 2018;

Sani and Lopes 2018;

Zink et al. 2003).

7. Implications for Intervention

Domestic violence by an intimate partner is a complex problem. The decision to leave is not simple and is better characterized by a process that is influenced by a complex interplay of factors, such as psychological, physical, economic, familial, social, and cultural factors (

Jones et al. 2017) operating at different ecological levels. Professionals can play an extremely important role in supporting the victims of violence in their decision-making, if the support provided meets the needs of the victim.

For this to happen, it is important from the outset to assume a non-pathological stance to safeguard the dignity of the victim and to increase the opportunities to identify the problem and possible solutions. The traditional deficit-centered paradigm must be challenged by an approach that recognizes the resources and strengths of each person (

Hamby 2014), that promotes action instead of passivity, and that does not just problematize but becomes part of the solution.

Thinking about resilience does not exclude thinking about risks but rather thinking about risks to convert them into points of intervention. This is sometimes done by inverting them (e.g., lack of support vs. existence of support; passivity vs. assertiveness) and by focusing on ways to promote a subject’s resources. This possibility only exists if we access the victim’s narratives so that we can understand their anguish, fears, and expectations. Rather than guiding our interventions by a prototype of a defenseless, passive, or dependent victim—that no theoretical model, exclusively, has managed to prove—we need to understand that the complex and multidimensional problem of IPV requires asking questions and outlining answers and that these can only be effective if constructed from the meanings of each individual subject. Only in this way can an individual intervention plan be effective, validating the multiple criteria that weigh on a victim’s decision to leave or stay in the abusive relationship.

This study helps to demonstrate the vital role that a qualitative, scientifically based approach can play in recognizing the best intervention strategies for victims of violence. Just as the decision to participate in this study was voluntary, so must the question of whether to leave (or stay in) the relationship be considered by the victim’s own decision-making process, supported (without pressure) by professionals. As we find that victims’ experiences are full of dissonances, we discuss the importance of adopting an intervention model that seeks to increase the victim’s resilience.

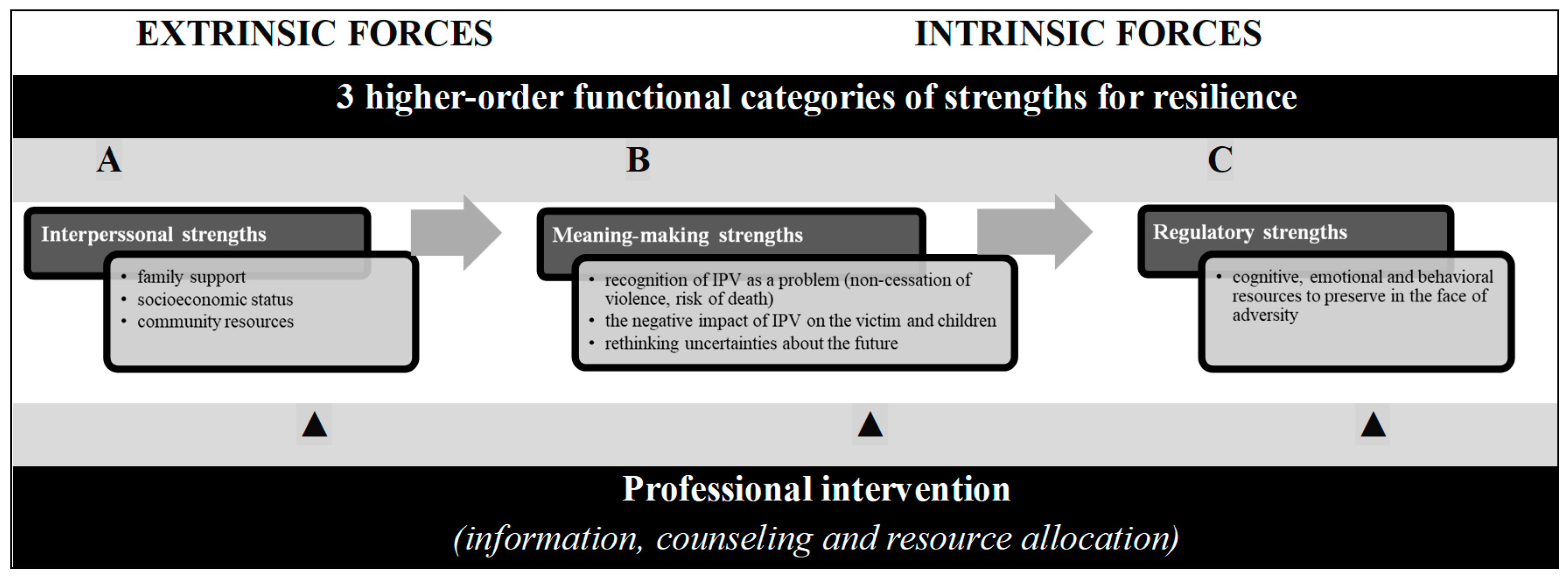

According to the Resilience Portfolio Model (

Grych et al. 2015), three major categories of forces are highlighted: interpersonal, meanings-making, and self-regulation. Thus, there are both extrinsic and intrinsic forces that can be worked with to enhance the victim’s resilience. As proposed by the authors of the model, the strengths and protective factors of the victim can shape how they deal (cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally) with IPV; identifying such factors offers mechanisms through which intrapersonal forces can be used to enhance the results of intervention, making it more effective.

Thus, support professionals should work to extract the strengths and protective factors of individual victims from their narratives. Over time, the recognized extrinsic forces (A, c.f.

Figure 1) may help the victim to deal with adversity, by strengthening the meaning-making (B) that enhances change and the capacity for intrinsic forces such as self-regulation (C) to overcome obstacles. To assist the victim in decision-making for a life without violence, professionals can, through their strategies and techniques, develop an approach to intervention that incorporates information (e.g., the dynamics of IPV, effects of IPV on children); counseling (e.g., for the well-being of victims and children); guidance resources (e.g., activating protection and prevention mechanisms such as shelters, the police); and strategies for promoting the stability of resilience forces. Given that the whole process is dynamic, the (in)stability of these forces can determine the failure or success of the intervention, which points to the importance of continuous and present support, which can be tailored as the victim’s self-sufficiency grows over time.

8. Conclusions

The results alert us to the need for professionals to think of support for the victim of IPV as a dynamic process, whose factors, at different times, may constitute an obstacle or a stimulus for the decision-making process concerned with leaving or staying in the abusive relationship. The professional is a crucial mediator who accepts the meaning-making of individuals who, through the process of sharing their narratives, can develop new understandings of their experience of victimization. An intervention that seeks to find the intrinsic or extrinsic forces of the individual (self-regulation, family support) can help victims deal with the situation in a more positive way. A person-centered approach and skills can help victims feel more supported and therefore better able to assess challenges, define strategies for coping with violence, and make a decision to leave the abusive intimate relationship. By paying attention to the victim’s narratives and their IPV experience, professionals can offer an intervention more focused on the victim’s needs.

The victim’s uncertainties about the future reinforce their belief about the need to maintain a violent relationship, with negative consequences for herself and her children. Given that our focus is exclusively on women (with children), we cannot fully consider the role and importance of children in the decision-making process, but it is clear that children are a central element in the victim’s decision to stay in or to leave the abusive relationship. However, the presence of other extrinsic factors such as interpersonal support (family, friends, neighbors, community), enhanced and maintained through personal qualities (e.g., gratitude, compassion, generosity, forgiveness), can lead to a better capacity for self-regulation to face adversity. Recognizing this, professionals can plan interventions that enhance the health and well-being of the individual at any stage of the process of leaving or staying in the abusive intimate relationship.

The individual construction of violence is highly influenced by the internalization that takes place in the context of social experience (e.g., gender discrimination, human rights). The identification of extrinsic factors (e.g., security, social support) among the victim’s concerns reinforces the need for the individual transformation process to be accompanied by a network in which professionals from various areas (e.g., police, courts, social action) work simultaneously with external factors that can, as we have seen, constrain motivations and decisions for change.

Given its nature, the results of this study cannot be generalized, but it is hoped that they provide an expression of the complexity of the experience of the victims and raise awareness that the intervention process should be flexible enough to attend to the individuality of the victims and the specific combination of factors involved. The resilience model is intended to meet these aims. The study makes a modest contribution to the understanding of the motivational process of leaving the abusive relationship and the development of more effective interventions focused on the victim and their experience of victimization.

To establish a broader understanding of these areas and add further weight to our conclusions, we suggest that future studies could address issues such as the type of sample (comparing victims with children and without children); the size of the sample (recruiting more participants); gender (creating contrasting groups or mixed samples); and evaluations at different times in the decision-making process to try to identify different phases and/or attempts to confront the problem. Other issues that could be explored in-depth include the aggressor’s role and considerations of justice, protection, and children’s rights.

There is a complex interplay of multiple factors that influence the victim’s decision of whether to leave or stay in an abusive relationship. Going further, adopting an ecological approach to the problem of domestic violence would make it possible to study factors at several levels, including the individual, family, community, and society. An important extension would be to develop studies with samples from different countries to look at the influence of culture.