Marketing in the Public Sector—Benefits and Barriers: A Bibliometric Study from 1931 to 2020

Abstract

1. Introduction

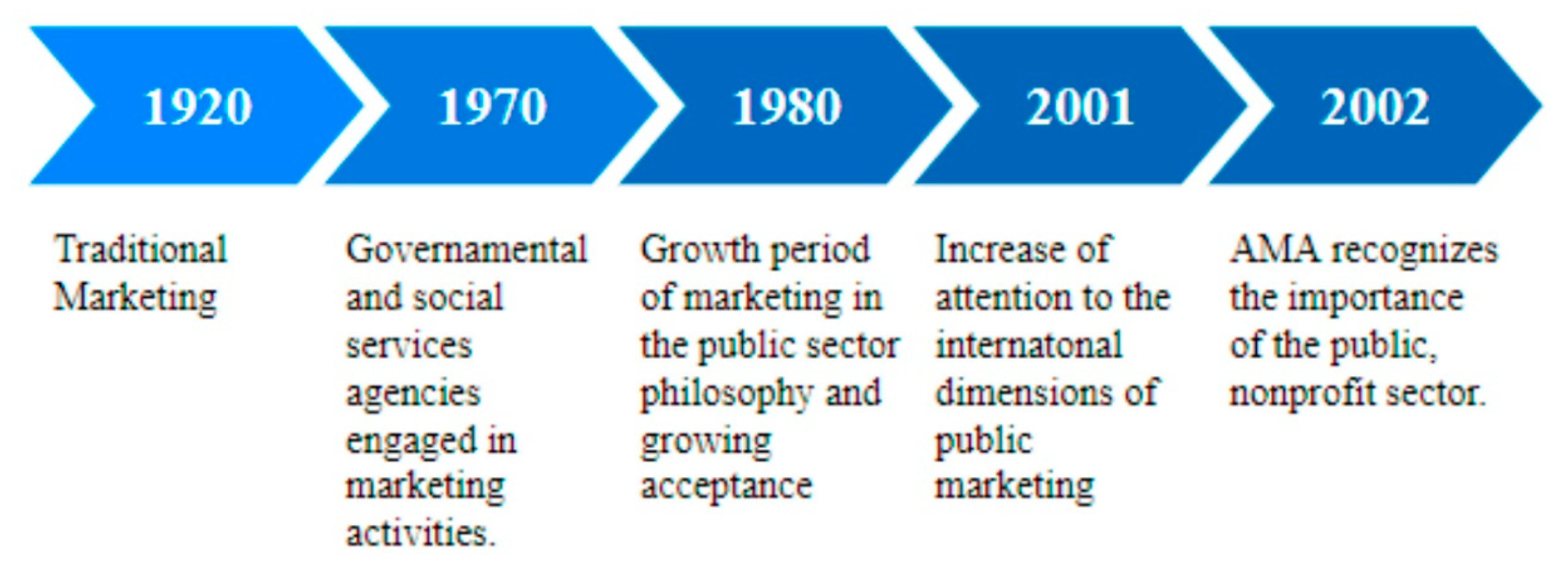

2. Theoretical Background

3. Methodology

3.1. Method and Bibliometric Variables

3.2. Data Source and Sample Analyzed

3.3. Main Stages of the Process

3.4. Period and Variables Analyzed

- -

- Number of articles per year;

- -

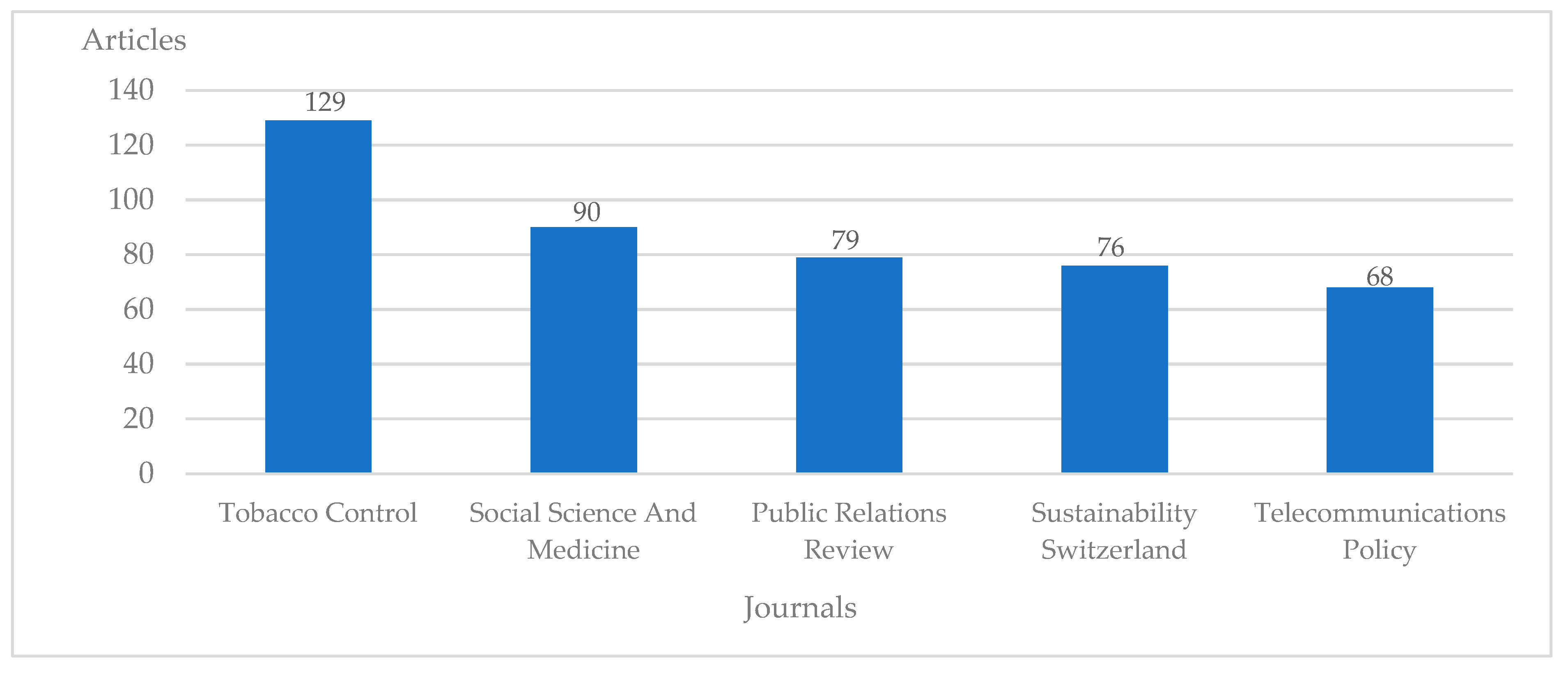

- Journals with most publications;

- -

- Documents by author;

- -

- Co-authorship network;

- -

- Articles by affiliation;

- -

- Articles by country;

- -

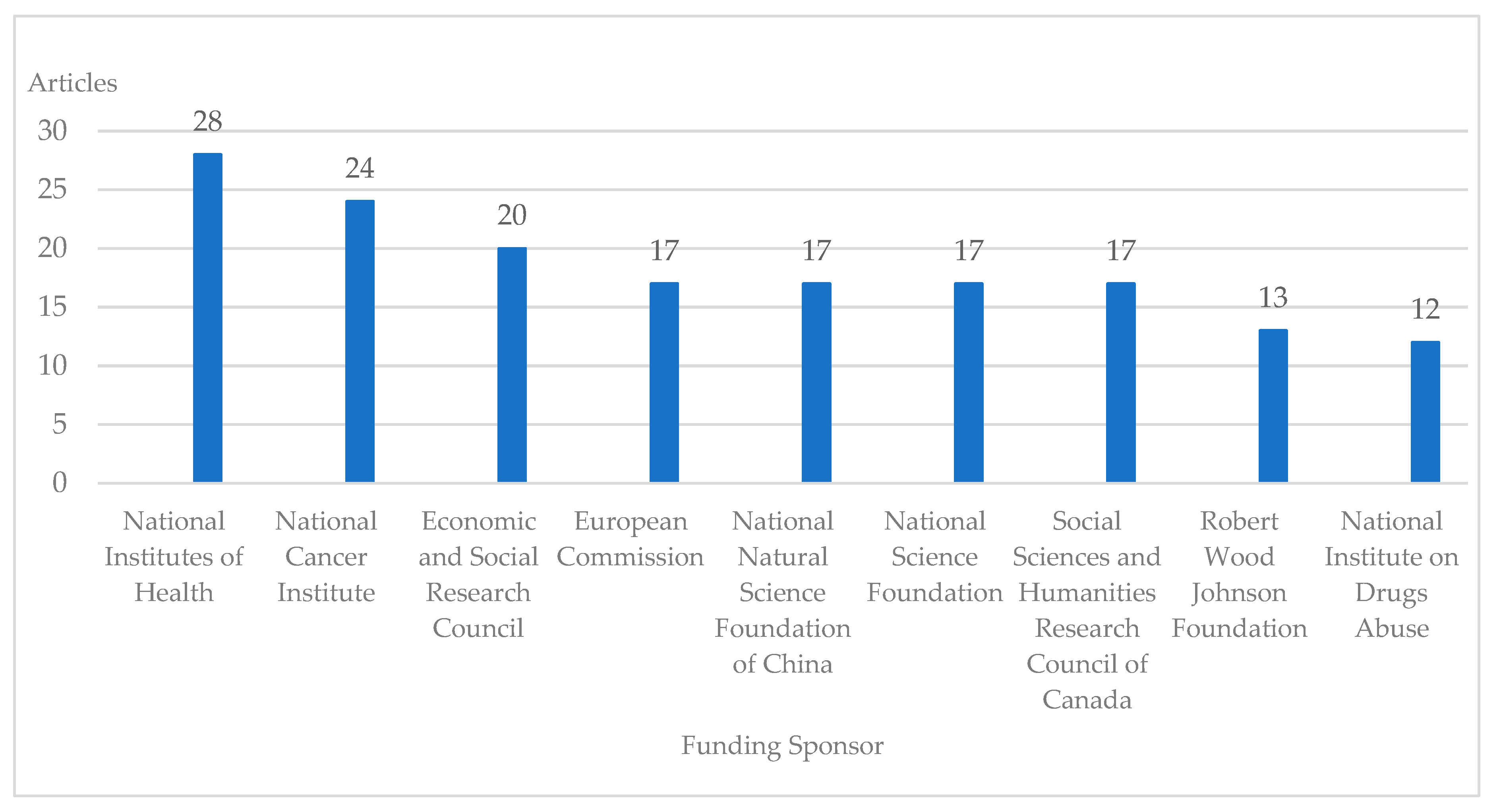

- Articles by funding sponsor;

- -

- Identifying main Clusters and topics in MPS.

3.5. Graphic Representation of the Data

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Main Contributors

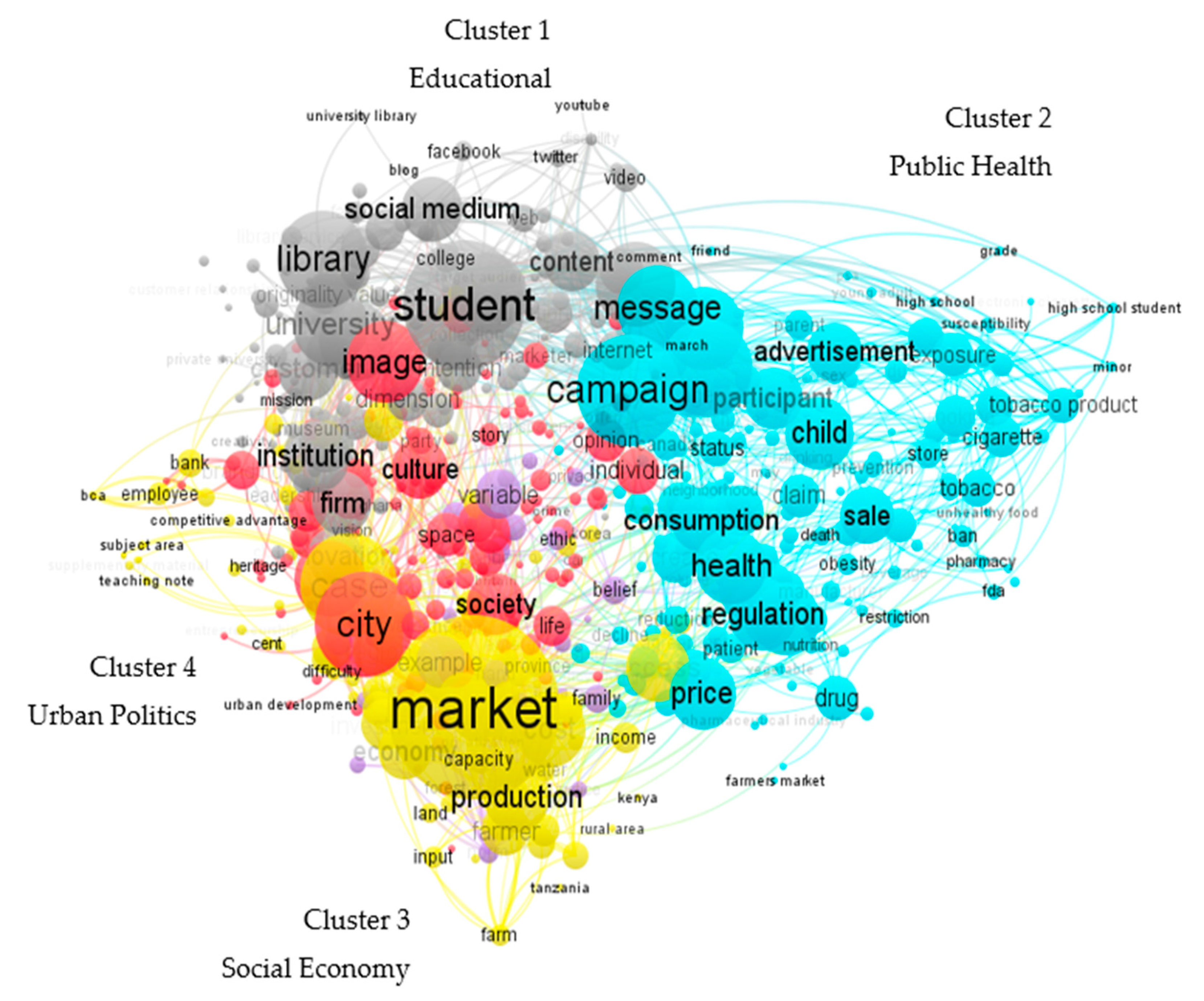

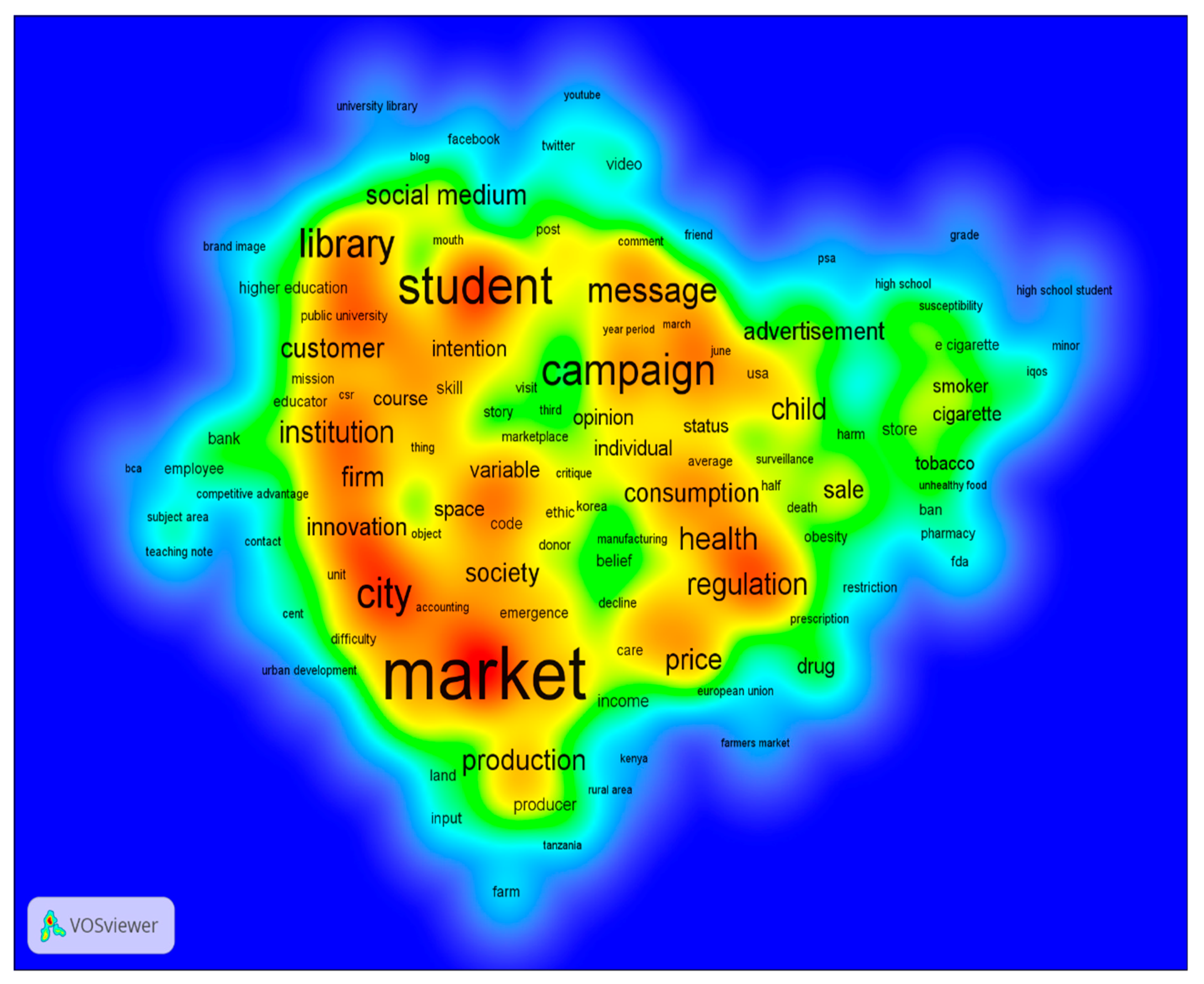

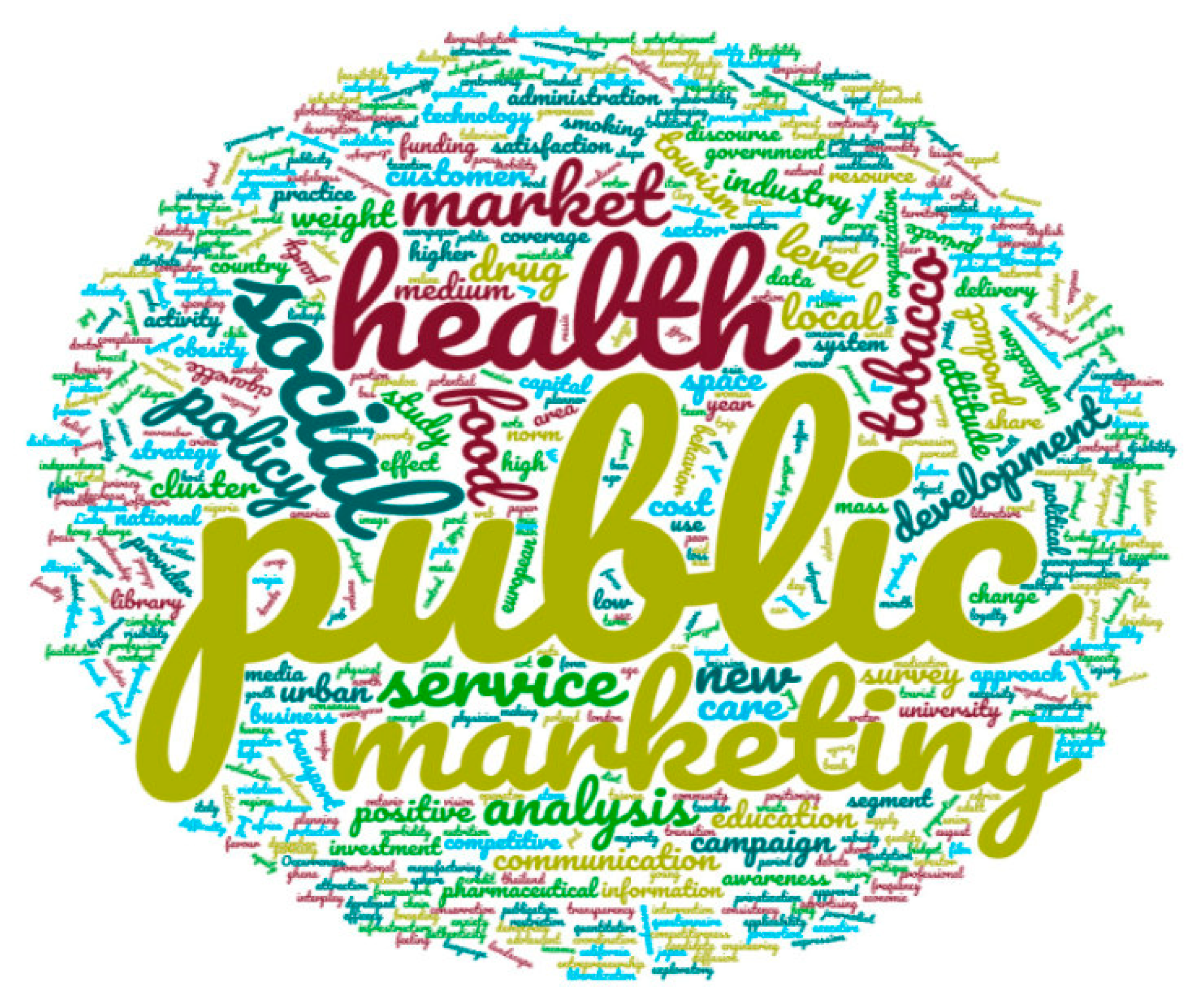

4.2. Identifying Main Clusters and Topics in MPS

4.2.1. Cluster 1—Educational

4.2.2. Cluster 2—Public Health

4.2.3. Cluster 3—Social Economy

4.2.4. Cluster 4—Urban Politics

4.3. Benefits and Barriers in MPS

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Future Avenues for Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al Dahdah, Marine. 2019. Between Philanthropy and Big Business: The Rise of mHealth in the Global Health Market. Development and Change. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemanno, Alberto. 2011. The Legality, Rationale and Science of Tobacco Display Bans after the Philip Morris Judgment. European Journal of Risk Regulation 2: 591–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Marketing Association. 2020. What Is Marketing? The Definition of Marketing. Available online: https://www.ama.org/the-definition-of-marketing-what-is-marketing/ (accessed on 17 July 2020).

- Andersson, Tommy D., and Donald Getz. 2009. Tourism as a Mixed Industry: Differences between Private, Public and Not-For-Profit Festivals. Tourism Management 30: 847–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, Sebastian, and Malte Brettel. 2010. Understanding the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Identity, Image, and Firm Performance. Management Decision 48: 1469–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaud, Fanny. 2016. Memorial Policies and Restoration of Croatian Tourism Two Decades after the War in Former Yugoslavia. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 14: 270–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, Gregory John, and Henk Voogd. 1990. Selling the City: Marketing Approaches in Public Sector Urban Planning. London: Belhaven. [Google Scholar]

- Avraham, Eli. 2004. Media strategies for improving an unfavorable city image. Cities 21: 471–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraham, Eli. 2013. Crisis Communication, Image Restoration, and Battling Stereotypes of Terror and Wars: Media Strategies for Attracting Tourism to Middle Eastern Countries. American Behavioral Scientist 57: 1350–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, George, Ruth E. Stables, and Hugh C. Phillips. 1997. Market Orientation in the Top 200 British Charity Organizations and Its Impact on Their Performance. European Journal of Marketing 31: 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini, Pierre P., and Paul R. Gamble. 2011. Confronting EU Unpopularity: The Contribution of Political Marketing. Contemporary Politics 17: 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercea, Oana-Bianca, Laura Bacali, and Elena-Simina Lakatos. 2016. Public Marketing: A Strategic Tool for Social Economy. Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research 11: 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsten, Gordon S. 1985. On the Role of Social Norms in a Market Economy. Public Choice 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, Thomas, and Erika Meins. 2003. Technological revolution meets policy and the market: Explaining cross-national differences in agricultural biotechnology regulation. European Journal of Political Research 42: 643–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briner, Rob B., David Denyer, and Denise M. Rousseau. 2009. Evidence-based management: Concept cleanup time? Academy of Management Perspectives 23: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broström, Anders, and Staffan Karlsson. 2017. Mapping Research on R&D, Innovation and Productivity: A Study of an Academic Endeavour. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 26: 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, Tiffany, Nathaniel Wander, and Jeff Collin. 2010. Uneasy money: The Instituto Carlos Slim de la Salud, tobacco philanthropy and conflict of interest in global health. Tobacco Control 19: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burris, Scott. 2008. Stigma, Ethics and Policy: A Commentary on Bayer’s “Stigma and the Ethics of Public Health: Not Can We but Should We”. Social Science & Medicine 67: 473–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Patrick, and Neil Collins. 1995. Marketing Public Sector Services: Concepts and Characteristics. Journal of Marketing Management 11: 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Sónia, Teresa Carvalho, and Rui Santiago. 2011. From Students to Consumers: Reflections on the Marketisation of Portuguese Higher Education. European Journal of Education 46: 271–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Mei-Lin. 2009. An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychology Review 21: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernev, Alexander, and Sean Blair. 2015. Doing Well by Doing Good: The Benevolent Halo of Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Consumer Research 41: 1412–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, Brian, Kay Muir, and Malcolm Blackie. 1985. An Improved Maize Marketing System for African Countries. Food Policy 10: 365–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Yoo Jin, James Thrasher, Michael Cummings, Hua H. Yong, Sara C. Hitchman, Ann McNeill, Geoffrey T. Fong, David Hammond, James Hardin, Lin Li, and et al. 2020. Cross-country comparison of cigarette and vaping product marketing exposure and use: Findings from 2016 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Tobacco Control 29: 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Hojoon, and Jeffrey K. Springston. 2014. How to Use Health and Nutrition–Related Claims Correctly on Food Advertising: Comparison of Benefit-Seeking, Risk-Avoidance, and Taste Appeals on Different Food Categories. Journal of Health Communication 19: 1047–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, Tamgid Ahmed, and Shahneela Naheed. 2019. Multidimensional Political Marketing Mix Model for Developing Countries: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of Political Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chriss, James J. 2015. Nudging and Social Marketing. Society 52: 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, William E. 1991. Democracy and territoriality. Millennium: Journal of International Studies 20: 463–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, Paul. 2013. Public Health Policy and the Behavioural Turn: The Case of Social Marketing. Critical Social Policy 33: 616–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, Paul. 2014. Changing Behaviours, Improving Outcomes? Governing Healthy Lifestyles through Social Marketing. Sociology Compass 8: 1127–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dart, Raymond. 2004. The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Elsa. 2008. Marketing the Self: The Politics of Aspiration among Middle-Class Silicon Valley Youth. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40: 2814–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deMatos, Nelson, Miguel Ángel Sánchez Jiménez, Célia M. Q. Ramos, Nuno Baptista, and João J. de Matos Ferreira. 2020. Systematic Literature Review on Global Strategy: Mapping Trends and Gaps. In Dynamic Strategic Thinking for Improved Competitiveness and Performance. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 243–70. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkhuizen, Marjoleine Amma, Frank Tammo Wieringa, Damayanti Soekarjo, Khan Tran Van, and Arnaud Laillou. 2013. Legal Framework for Food Fortification: Examples from Vietnam and Indonesia. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 34: S112–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffett, Rodney. 2020. The YouTube Marketing Communication Effect on Cognitive, Affective and Behavioural Attitudes among Generation Z Consumers. Sustainability 12: 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Acevedo, Mónica, Luis J. Belmonte-Ureña, Francisco Joaquín Cortés-García, and Francisco Camacho-Ferre. 2020. Agricultural waste: Review of the evolution, approaches and perspectives on alternative uses. Global Ecology and Conservation 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, Ludvík, Dana Egerová, Lukasz Tomczyk, Miroslav Krystoň, and Csilla Czeglédi. 2020. Facebook for Public Relations in the higher education field: A study from four countries Czechia, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, Patrice, and Sandra L Huffman. 2010. Growing children’s bodies and minds: Maximizing child nutrition and development. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 31: S186–S197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evashwick, Connie, and Marcia Ory. 2003. Organizational Characteristics of Successful Innovative Health Care Programs Sustained Over Time. Family & Community Health 26: 177–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Karen F. A. 1988. Social Marketing of Oral Rehydration Therapy and Contraceptives in Egypt. Studies in Family Planning 19: 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Becky, Bridget Kelly, Stefanie Vandevijvere, and Louise Baur. 2016. Young Adults: Beloved by Food and Drink Marketers and Forgotten by Public Health? Health Promotion International 31: 954–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, Mason. 1997. What Price Water Marketing? American Journal of Economics and Sociology 56: 475–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, Arunesh. 2015. Green Marketing for Sustainable Development: An Industry Perspective. Sustainable Development 23: 301–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Bernie, Emilie Mallia, and Joseph Anthony. 2019a. Public perceptions of Internet-based health scams, and factors that promote engagement with them. Health and Social Care in the Community 27: e672–e686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, Bernie, Sue Murphy, Shahin Jamal, Maura MacPhee, Jillian Reardon, Winson Cheung, Emilie Mallia, and Cathryn Jackson. 2019b. Internet health scams—Developing a taxonomy and risk-of-deception assessment tool. Health and Social Care in the Community 27: 226–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geissdoerfer, Martin, Paulo Savaget, Nancy M. P. Bocken, and Erik Jan Hultink. 2017. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production 143: 757–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, William A. 2016. Manipulating Citizens: How Political Campaigns’ Use of Behavioral Social Science Harms Democracy. New Political Science 38: 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Maia. 2000. Public Reform and the Privatisation of Poverty: Some Institutional Determinants of Health Seeking Behaviour in Southern Tanzania. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Jin Hong, and Mary Ann Ferguson. 2015. Perception Discrepancy of Public Relations Functions and Conflict among Disciplines: South Korean Public Relations Versus Marketing Professionals. Journal of Public Relations Research 27: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Cao Thi, Trinh Thi Phuong Thao, Nguyen Tien Trung, Le Thi Thu Huong, Ngo Van Dinh, and Tran Trung. 2020. A Bibliometric Review of Research on STEM Education in ASEAN: Science Mapping the Literature in Scopus Database, 2000 to 2019. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 16: em1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimanolis, Athanasios. 2010. Methods of Political Marketing in (Trans)Formation of Innovation Culture. Journal of Political Marketing 9: 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenschen, Katherine, and Jordan Wolf. 2019. Disclaiming responsibility: How platforms deadlocked the Federal Election Commission’s efforts to regulate digital political advertising. Telecommunications Policy 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Meiling, Martin de Jong, Zhuqing Cui, Limin Xu, Haiyan Lu, and Baiqing Sun. 2018. City branding in China’s Northeastern region: How do cities reposition themselves when facing industrial decline and ecological modernization? Sustainability 10: 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Solveig Lena, Larissa Pfaller, and Silke Schicktanz. 2020. Critical analysis of communication strategies in public health promotion: An empirical-ethical study on organ donation in Germany. Bioethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, E. Mark, and Walter Henry. 1992. Strategic Marketing for Educational Systems. School Organisation 12: 255–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Phil, and Conor McGrath. 2012. Political Marketing and Lobbying: A Neglected Perspective and Research Agenda. Journal of Political Marketing 11: 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss-White, Barbara. 1995. The Changing Public Role in Services to Food and Agriculture. Food Policy 20: 585–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, Jill E., and Ellen Goddard. 2015. Consumers and trust. Food Policy 52: 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Christopher. 1991. A public management for all seasons? Public Administration 69: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, Diane G., and Richard Schulz. 1995. Assessment of Marketing Strategies for Interdisciplinary Continuing Education Programs in Geriatrics. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education 15: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, Marjana, and Jerzy Kociatkiewicz. 2011. City festivals: Creativity and control in staged urban experiences. European Urban and Regional Studies 18: 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Yu-Min, and Bokyong Seo. 2018. Transformative city branding for policy change: The case of Seoul’s participatory branding. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 36: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Bonnie. 2016. How Should Health Data Be Used? Privacy, Secondary Use, and Big Data Sales Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 25: 312–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Andreas M., and Michael Haenlein. 2009. The Increasing Importance of Public Marketing: Explanations, Applications and Limits of Marketing within Public Administration. European Management Journal 27: 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzir, Shai, and Lotem Perry-Hazan. 2019. Legitimizing public schooling and innovative education policies in strict religious communities: The story of the new Haredi public education stream in Israel. Journal of Education Policy 34: 215–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Gillian Ann, Lynne Eagle, and Julia Verne. 2011. Mass media barriers to social marketing interventions: The example of sun protection in the UK. Health Promotion International 26: 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knai, C., M. Petticrew, M. A. Durand, E. Eastmure, L. James, A. Mehrotra, C. Scott, and N. Mays. 2015. Has a Public–Private Partnership Resulted in Action on Healthier Diets in England? An Analysis of the Public Health Responsibility Deal Food Pledges. Food Policy 54: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, Iva, Jasmina Starc, and Barbara Rodica. 2015. Development of Social Innovations and Their Marketing: A Slovenian Case Study. Informatologia 48: 154–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kostygina, Ganna, Hy Tran, Steven Binns, Glen Szczypka, Sherry Emery, Donna Vallone, and Elizabeth Hair. 2020. Boosting Health Campaign Reach and Engagement through Use of Social Media Influencers and Memes. Social Media and Society 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip, and Sidney J. Levy. 1969. Broadening the Concept of Marketing. Journal of Marketing 33: 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip, and Gerald Zaltman. 1971. Social Marketing: An Approach to Planned Social Change. Journal of Marketing 35: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, Angus, and Lorna McKee. 2001. Willing volunteers or unwilling conscripts? Professionals and marketing in service organisations. Journal of Marketing Management 17: 559–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, David A., and Thomas G. McGuire. 1990. Political and Economic Determinants of Insurance Regulation in Mental Health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 15: 169–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Larsåke. 2007. Public Trust in the PR Industry and Its Actors. Journal of Communication Management 11: 222–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2019. Skiing all the way to the polls: Exploring the popularity of personalized posts on political Instagram accounts. Convergence 25: 1096–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, Hwa Meei. 2016. Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising—In the Perspective of Competition Law. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 19: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Litvin, Stephen W., and Sharon Ng Sok Ling. 2001. The destination attribute management model: An empirical application to Bintan, Indonesia. Tourism Management 22: 481–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, Will, and Eileen Davenport. 2009. Organizational Leadership, Ethics and the Challenges of Marketing Fair and Ethical Trade. Journal of Business Ethics 86: 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, Natàlia, Jordi Prades, and Marta Montagut. 2015. Som la Pera: How to develop a social marketing and public relations campaign to prevent obesity among teenagers in Catalonia. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies 7: 251–59. [Google Scholar]

- Madill, Judith J. 1998. Marketing in Government. Optimum: The Journal of Public Sector Management 28: 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Nazar, Abid Salih Kumait, Samir Othman, and Namir Al-Tawil. 2019. Assessment of certain aspects and health issues that encountered by street children and adolescents in Kirkuk city. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology 13: 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, Anas A., and Ibrahim Mosly. 2020. Factors Affecting Public Willingness to Adopt Renewable Energy Technologies: An Exploratory Analysis. Sustainability 12: 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, Alan. 1986. Public and Private Sector Interactions: An Economic Perspective. Social Science & Medicine 22: 1161–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArdle, Maeve, C. Cecily Kelleher, and James J. Ward. 1993. Consumer choice and Ireland’s tobacco regulations: Do restaurateurs meet their client’s needs? Health Promotion International 8: 275–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, David, and Prashanti Mayfield. 2015. City of the Spectacle: White Night Melbourne and the politics of public space. Australian Geographer 46: 507–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Morgan P., Martie-Louise Verreynne, Andrew McAuley, and Kevin Hammond. 2017. Exploring Public Universities as Social Enterprises. International Journal of Educational Management 31: 404–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, Wasif, and Jo Perret. 2017. A UAE Case Study: Experiential Learning through Effective Educational Partnerships. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education 9: 304–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, David, Jr., and Joseph D. Fridgen. 1994. Public policy and private promotion in tourism a new type of room tax. Tourism Recreation Research 19: 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naftali, Orna. 2014. Marketing War and the Military to Children and Youth in China: Little Red Soldiers in the Digital Age. China Information 28: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomani, M. Z. M., Alaa K. K. Alhalboosi, and Mohammad Rauf. 2020. Legal & Intellectual Property Dimension of Health & Access to Medicines in India. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 14: 118–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norén, Lars. 2010. The Private Interests of Consumers in the Healthcare Market. International Journal of Public Sector Management 23: 364–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson Beal, Heather K., and Brent D. Beal. 2016. Assessing the Impact of School-Based Marketing Efforts: A Case Study of a Foreign Language Immersion Program in a School-Choice Environment. Peabody Journal of Education 91: 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmatier, Robert W., Rajiv P. Dant, Dhruv Grewal, and Kenneth R. Evans. 2006. Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing 70: 136–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashootanizadeh, Mitra, and Zahra Rafie. 2020. Social Media Marketing: Determining and Comparing View of Public Library Directors and Users. Public Library Quarterly 39: 212–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penders, Bart, and Annemiek P. Nelis. 2011. Credibility Engineering in the Food Industry: Linking Science, Regulation, and Marketing in a Corporate Context. Science in Context 24: 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perianes-Rodriguez, António, Ludo Waltman, and Nees Jan van Eck. 2016. Constructing bibliometric networks: A comparison between full and fractional counting. Journal of Informetrics 10: 1178–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyne, John G. 1996. Balancing Social Equity and Environmental Integrity in Ireland’s Salmon Farming Industry. Society & Natural Resources 9: 281–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, Catherine, and Jason Byrne. 2014. The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development 33: 534–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkerton, Steven D., Carol L. Galletly, Timothy L. McAuliffe, Wayne DiFranceisco, H. Fisher Raymond, and Harrell W. Chesson. 2010. Aggregate Versus Individual-Level Sexual Behavior Assessment: How Much Detail Is Needed to Accurately Estimate HIV/STI Risk? Evaluation Review 34: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey-Maddox, Linn, Shelley McDonough Kimelberg, and Maia Cucchiara. 2014. Middle-Class Parents and Urban Public Schools: Current Research and Future Directions. Sociology Compass 8: 446–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potterton, Amanda U. 2020. Parental Accountability, School Choice, and the Invisible Hand of the Market. Educational Policy 34: 166–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Madeline, and Stephen P. Osborne. 2020. Social enterprises, marketing, and sustainable public service provision. International Review of Administrative Sciences 86: 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, Tony. 2007. Public Sector Marketing, 1st ed. Essex: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Pykett, Jessica, Rhys Jones, Marcus Welsh, and Mark Whitehead. 2014. The Art of Choosing and the Politics of Social Marketing. Policy Studies 35: 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbiosi, Chiara. 2015. Renewing a historical legacy: Tourism, leisure shopping and urban branding in Paris. Cities 42: 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M. Isabel Barreiro, António J. Gonçalves Fernandes, and Isabel Maria Lopes. 2020. Digital Marketing: A bibliometric Analysis based on the Scopus Database Scientific Publications. In Digital Marketing Strategies and Models for Competitive Business. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, James A., and Eli Jones. 2001. Money Attitudes, Credit Card Use, and Compulsive Buying among American College Students. Journal of Consumer Affairs 35: 213–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandercock, Leonie, and Kim Dovey. 2002. Pleasure, Politics, and the ‘Public Interest’: Melbourne’s Riverscape Revitalization. Journal of the American Planning Association 68: 151–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, José de Freitas, Laurentina Vareiro, Paula Remoaldo, and José Cadima Ribeiro. 2017. Cultural mega-events and the enhancement of a city’s image: Differences between engaged participants and attendees. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 9: 129–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura, Jose Ramon. 2020. Using Data Sciences in Digital Marketing: Framework, Methods, and Performance Metrics. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saur-Amaral, Irina, Pedro Ferreira, and Rosa Conde. 2013. Linking past and future research in tourism management through the lens of marketing and consumption: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management Studies 9: 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schloegel, Catherine. 2007. Sustainable tourism: Sustaining biodiversity? Journal of Sustainable Forestry 25: 247–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scranton, Philip. 1995. The Politices of Production: Technology, Markets, and the Two Cultures of American Industry. Science in Context 8: 369–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, Hugues, Anca C. Yallop, Alexandru Capatîna, and Vanessa G. B. Gowreesunkar. 2018. Heritage in tourism organisations’ branding strategy: The case of a post-colonial, post-conflict and post-disaster destination. International Journal of Culture, Tourism, and Hospitality Research 12: 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, Greg. 2019. Putin’s International Political Image. Journal of Political Marketing 18: 307–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Manjet Kaur Mehar. 2016. Socio-Economic, Environmental and Personal Factors in the Choice of Country and Higher Education Institution for Studying Abroad among International Students in Malaysia. International Journal of Educational Management 30: 505–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, Sanna. 2019. Fighting for public health: The promotion of desirable bodies in interactive military marketing. Media, War and Conflict. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiarto, Sugiarto, Tomio Miwa, and Takayuki Morikawa. 2020. The tendency of public’s attitudes to evaluate urban congestion charging policy in Asian megacity perspective: Case a study in Jakarta, Indonesia. Case Studies on Transport Policy 8: 143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, Norazah Mohd. 2013a. Green Awareness Effects on Consumers’ Purchasing Decision: Some Insights from Malaysia. International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies 9: 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Suki, Norazah Mohd. 2013b. Students’ Dependence on Smart Phones. Campus-Wide Information Systems 30: 124–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szablewska, Natalia, and Krzysztof Kubacki. 2019. A Human Rights-Based Approach to the Social Good in Social Marketing. Journal of Business Ethics 155: 871–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, David M., and David H. Henard. 2001. Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 29: 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Chris K. K. 2009. ‘But They Are Like You and Me’: Gay Civil Servants and Citizenship in a Cosmopolitanizing Singapore. City & Society 21: 133–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Gina, Allison Nichols, and Ami Cook. 2014. How Knowledge, Experience, and Educational Level Influence the Use of Informal and Formal Sources of Home Canning Information. Journal of Extension 52: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tweneboah-Koduah, Ernest Yaw, Matilda Adams, and Kwamina Minta Nyarku. 2020. Using Theory in Social Marketing to Predict Waste Disposal Behaviour among Households in Ghana. Journal of African Business 21: 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, Muzaffer, and John L. Crompton. 1985. An Overview of Approaches Used to Forecast Tourism Demand. Journal of Travel Research 23: 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2014. Visualizing bibliometric networks. In Measuring Scholarly Impact. Edited by Ding Y, Rousseau R and Wolfram D. Cham: Springer, pp. 285–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2019. VOSviewer Manual. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.13.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Vining, Aidan R., and Anthony E. Boardman. 2008. The Potential Role of Public–Private Partnerships in the Upgrade of Port Infrastructure: Normative and Positive Considerations. Maritime Policy & Management 35: 551–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukovič, Goran, Tomaž Kern, Gozdana Miglič, Bruno Završnik, and Robert Leskovar. 2010. Interdependence of the Evaluation and Marketing of Education Services in the State Administration. Didactica Slovenica Pedagoska Obzorja 25: 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Kieron. 1991. Citizens and Consumers: Marketing and Public Sector Management. Public Money & Management 11: 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Kieron. 1994. Marketing and Public Sector Management. European Journal of Marketing 28: 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, Elizabeth M., Nicole C. Jarrett, April M. W. Young, Sherry A. Adeyemi, and Leda M. Perez. 2007. Building Effective Programs to Improve Men’s Health. American Journal of Men’s Health 1: 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winett, Liana B., and Laurence Wallack. 1996. Advancing public health goals through the mass media. Journal of Health Communication 1: 173–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wymer, Walter, Katie McDonald, and Wendy Scaife. 2013. Effects of Corporate Support of a Charity on Public Perceptions of the Charity. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 25: 1388–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G., and J. G. Myrick. 2020. Online media use and HPV vaccination intentions in mainland China: Integrating marketing and communication perspectives to improve public health. Health Education Research 35: 110–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, Lydia, Robin Douthitt, and So-Ye You. 2003. Consumer Risk Perceptions toward Agricultural Biotechnology, Self-Protection, and Food Demand: The Case of Milk in the United States. Risk Analysis 23: 973–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Daowei, and Eric Aboagye Owiredu. 2007. Land Tenure, Market, and the Establishment of Forest Plantations in Ghana. Forest Policy and Economics 9: 602–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Huiquan, and Shihua Ye. 2019. Legitimacy, Worthiness, and Social Network: An Empirical Study of the key Factors Influencing Crowdfunding Outcomes for Nonprofit Projects. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 30: 849–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Term | Number of Articles and Reviews Found in Scopus Database |

|---|---|

| Public marketing | 28,809 |

| Marketing in the public sector | 3447 |

| Public marketing benefits | 3463 |

| Public Marketing barriers | 905 |

| Public marketing OR Marketing in the public sector | 28,809 |

| OR Public marketing benefits OR Public Marketing barriers | |

| (TITLE-ABS-KEY (public AND marketing) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (marketing AND in AND the AND public AND sector) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (public AND marketing AND benefits) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (public AND marketing AND barriers)) |

| Cluster Topic | Benefits | Barriers |

|---|---|---|

| Educational | Development of maternal education, promotion of equality of opportunities, campaigning for public health education. | Problematic relationship between schools, communities, organizations and cultures. Social media platforms influence on public services. |

| Higher education, health education, marine education, educational systems | ||

| Public Health | Increase of campaigns for breast cancer prevention, access to genetically modified food, promotion of physical activity benefits, reduction of pesticides. | Insufficient organ donations, high financial costs, socially acceptable alcoholism, high Legal requirements to access the markets, lack of e-regulation. |

| Health behavior, public health, health politics, health promotion, health sciences, legal restrictions | ||

| Social Economy | Greater social integration, Better social awareness for victims of domestic violence. | Lack of market innovation, low level of Social responsibility, Growth of Economic exclusion, Social change avoidance, political power pressure, persistent political instability. |

| Social services, social policy, social structure, social values | ||

| Urban Politics | Advancements in urban economy, increase of political legitimacy, reinforcement of political engagement. | Restrictions of city development, lack of trust of city brand and image, slow adoption of innovative behaviors. |

| Urban development, political economy, political science, urban political research |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matos, N.d.; Correia, M.B.; Saura, J.R.; Reyes-Menendez, A.; Baptista, N. Marketing in the Public Sector—Benefits and Barriers: A Bibliometric Study from 1931 to 2020. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9100168

Matos Nd, Correia MB, Saura JR, Reyes-Menendez A, Baptista N. Marketing in the Public Sector—Benefits and Barriers: A Bibliometric Study from 1931 to 2020. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(10):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9100168

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatos, Nelson de, Marisol B. Correia, José Ramón Saura, Ana Reyes-Menendez, and Nuno Baptista. 2020. "Marketing in the Public Sector—Benefits and Barriers: A Bibliometric Study from 1931 to 2020" Social Sciences 9, no. 10: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9100168

APA StyleMatos, N. d., Correia, M. B., Saura, J. R., Reyes-Menendez, A., & Baptista, N. (2020). Marketing in the Public Sector—Benefits and Barriers: A Bibliometric Study from 1931 to 2020. Social Sciences, 9(10), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9100168