Abstract

The aim of this study is to understand the perspective of elderly residents on their neighborhood and how the composition of the neighborhood influences their daily life. The study took place in the city of Cáceres (Spain) that aspires to become an age-friendly city. This study focused on the intangible elements of the neighborhood related to feelings of safety, well-being, loneliness, belonging to the community and development of trusting relationships. The research was based on the sociology of aging, specifically referencing the theory of the activity of aging, and also urban sociology, which assumes the environment as a conditioning agent of daily life. Using a qualitative approach, 32 in-depth interviews were conducted with individuals over 65. The interviews were analyzed according to grounded theory. The results show how social aspects are key factors for the elderly in their perception of the neighborhood. Therefore, psychological, social and emotional dimensions of the neighborhood influence elderly residents and could have a positive or negative effect on successful aging. These findings also suggest that a crucial aspect of the positive perceptions of the environment lies in the quality of social interactions that take place inside the neighborhood.

1. Introduction

Modern societies are worried about their aging populations, since it is an unprecedented situation that derives from cultural and social changes (Chao 2005; Cordero del Castillo 2007). Consequently, a new profile of elderly people has arisen characterized by: economic stability, higher educational levels, use of new technologies and the rise in awareness regarding both physical and mental care (Bazo and García Sanz 2014; Requena 2006). In keeping with these developments, the third age is related to activity, leisure and social participation (Sancho Prieto et al. 2015), while the fourth age represents the last stage of life, associated with diseases, dependence and, finally, death (Chao 2005; Cordero del Castillo 2007; Requena 2006). Therefore, the life of people over 65 is different from the classic social image in which grandparents were passive participants (Dias 2012). Nowadays, elderly people are an active part of the community and are involved in a variety of ways.

In this new social and demographic environment, the elderly seek an independent aging, being active and living in their own homes. With old age, spaces for social interaction are modified and reduced mainly to the home and the neighborhood. Hence, these two contexts become key elements of successful aging (Puga González and Abellán García 2006; Wiles et al. 2012).

Studies about neighborhoods or cities and their relationships with elderly residents usually focus on the effects that these spaces have on the physical health of the elderly (Hoffimann et al. 2017; Stafford and Marmot 2003). Several authors have analyzed the effects that a neighborhood has on its aging inhabitants (Cerin et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2017; Sallis et al. 2015). These types of studies are usually based on the quantitative analysis of the availability of certain services, such as green areas, public transport and pedestrian areas. These studies affirm that certain types of infrastructure are positive for aging citizens, regardless of how they are perceived or used by them. Indeed, sometimes their sheer presence is more important than the actual interaction with them, demonstrating that the subjective image of this type of infrastructure is just as important as the existence of them.

There are a limited number of research studies (Conde et al. 2018; Howell 1983; Ronzi et al. 2016) that analyze neighborhoods from the subjective point of view of residents. I believe that the amount of businesses and services in itself could be insufficient to meet the needs of elderly residents, requiring an analysis of the perception of the use of existing infrastructure in the neighborhood. Hoffiman, Barros and Ribeiro Hoffimann et al. (2017) affirmed that, to encourage people to use the spaces in cities, it is first necessary to understand the real needs of the cities’ residents.

2. Background: Spain and Cáceres Context

Spain is a member of the European Union and has a total population of 46.72 million people. Its gross domestic product (GDP) is around 1.2 trillion Euros and it is within the twenty largest economies in the world (IMF 2018). Similar to other countries with comparable socioeconomic characteristics, it is faced with the gradual aging of its population. Thanks to technological and medical advances, it is possible to live longer healthier lives, which translates into an increased life expectancy (Beard and Bloom 2015). In accordance with this increase, the life-span stages have been adapted, adding a new life stage: the fourth age. This refers to the last stage of life characterized by disease, loss of body control and, finally, death. For its part, the third age is now considered a stage defined primarily by freedom, health and independence (Wiggins et al. 2004). For this reason, starting in the 1990s, organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) have been placing special emphasis on active aging and aging in place (Phillipson 2011). Despite their age, older people continue to participate in society after retirement, and value the independence of continuing to live in their homes (Wiles et al. 2012).

In Spain, the life expectancy at birth is 86.1 years for women and 80.6 years for men. According to the statistical projections in 2020, 20% of the population will be composed of people aged 65 and over, and this will exceed 30% by 2050 (EUROSTAT 2017). It also increases life expectancy at 65; according to Eurostat, it is expected that at 65 the healthy life years for women will be 23.4 years and 19.3 years for men. Therefore, Spanish people, in addition to becoming octogenarians, will be able to fully enjoy their retirement years. These projections mean that, once retired, older Spanish people will still have about a quarter of their lives left to enjoy.

For this study, I chose 65 as the marker for the beginning of the old age period because it is the established retirement age in Spain. In Spain, retirement determines the departure of the individual from the working world and, therefore, the beginning of the third age. Historically, this moment was associated with the negative effects of aging such as illness or dependency, but today, the profile of senior citizens has changed.

Two aspects are essential in this new profile: healthcare and pensions. In Spain, healthcare is free and it is a citizen’s right. In the same way, receiving a pension at the end of one’s working life is also a right, which ensures economic stability for seniors and their families. The economic crisis has made pensions an economic lifeline for many families (Sancho et al. 2015).

Educational level is another key aspect in this new profile. The end of the dictatorship and the beginning of democracy (1978) ensured the right to free education in Spain. Consequently, the educational level of the elderly, as well as that of the entire population has increased. As a result, the illiterate population decreased from 7% in 1981 to 1.7% in 2019 (INE 2019).

The last defining characteristic of the new profile of the elderly in Spain is related to family dynamics. In the Spanish culture, seniors are an integral part of the family. There are strong social networks and support amongst family members, as well as moral obligations to take care of each other (Bazo and García Sanz 2014). Nowadays, it is frequent for grandparents to care for grandchildren, as well as help the family unit financially.

Thus, seniors in Spain are characterized as having a good educational level and as well as good health for many years after retirement. They are independent, both physically and economically, enjoying their freedom and social life. Additionally, Spanish culture places great value on social and family networks, which are indispensable and recognized as important resources. Therefore, elderly people constitute an essential resource and economic support for their children and society.

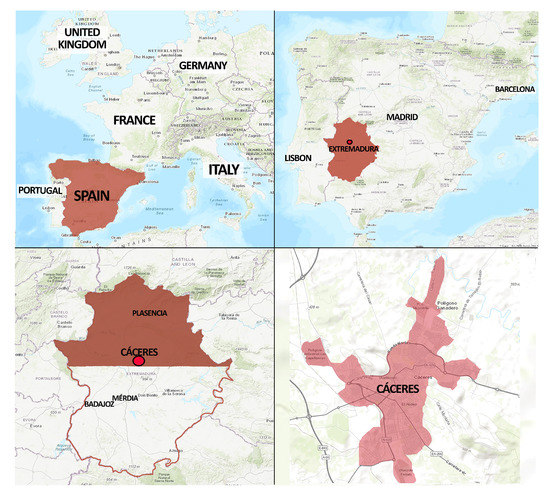

Cáceres

Cáceres belongs to the autonomous community of Extremadura. Extremadura is divided into two provinces: Cáceres and Badajoz. The city of Cáceres is the capital of the province of Cáceres (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of Cáceres within Europe, Spain and the autonomous community of Extremadura.

It is the second most populated city in Extremadura with 96,068 inhabitants. The Old Quarter of Caceres is one of the best preserved medieval ensembles in Europe and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1986. Since then, tourism has been increasing, especially around the medieval quarter of the city. This area is full of businesses dedicated to tourism, including hotels and tourist apartments. Currently, tourism combined with the service sector make up the core of the city’s economy (Gallego et al. 2015).

The profile of elderly residents in Cáceres has the same characteristics as the overall Spanish population, with an increase in the aging population similar to other cities around the world. Demonstrating this trend, the life expectancy for men at 65 years in the province of Cáceres is 18.68 years and 22.66 years for women. These numbers are very similar to the national average aforementioned (INE 2018a). In 2018, the aging index—elderly people per 100 young people under 16 years old (Gavrilov and Heuveline 2003)—reached the value of 110.53 in the city of Cáceres (IEEX 2018a). This value is similar to the aging index of the country: 120.46 (INE 2018b). However, the aging index of the province of Cáceres is 164.64 (INE 2018b), due to the depopulation of rural areas in favor of urban areas (Nieto and García 2014). The percentage of people over 65 in rural areas of the province of Cáceres—municipalities with under 10,000 inhabitants—is 31.78%, whereas in the city of Cáceres it is 16.81%, which is more in line with the rest of the country with a rate of 19.20% (IEEX 2018b; INE 2018b).

3. Theoretical Underpinning

This study was based on the sociology of aging—activity theory of aging (Havighurst 1963)—and urban sociology, assuming the environment as a conditioning agent of daily life.

In 2002, the WHO formalized the term active aging—which is closely related to the term successful aging—at the institutional level, explicitly defined as: “Active aging is the process of optimizing opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people aged” (WHO 2002, p. 12). This declaration not only recognizes the new social status of the elderly but also allows them to claim rights as active citizens, who continue to be part of their communities. There are three pillars to consider when evaluating active aging: physical, mental and social health; safety and protection systems against problems related to aging; and active participation within the community (Rodríguez et al. 2013; WHO 2002).

According to Remy and Voyé (1976), the lifestyle of individuals is conditioned by the elements that make up their surroundings and their relationship with those surroundings. In the same way that social agents influence spaces through interactions, physical spaces also influence people. However, as Lynch (Lynch 1960) noted, the relationship between an individual and a city may vary. Lynch explained this using the concept of the image of the city, observing how the interaction with urban spaces can vary greatly depending on the individual that is asked. This subjective view evokes symbolic interactionism. In addition, and according to the ecological model by Lawton (1989), those subjects who interact more with their environment will have better resources at their disposal and will be better adapted.

Puga González and Abellán García (2006) warned of a correlation between an aging population and the reduction of accessible urban spaces. The correlation is primarily caused by the increase in physical problems and the lack of adaptations of the architectural environment. In this way, cities can be perceived as hostile or insecure places (Phillipson 2011), which, on occasion, can have negative consequences for the health of elderly residents (Buffel et al. 2012). The physical and cognitive benefits of continuing to live in their own homes for this age group has been demonstrated (Almeida 2014; Lecovich 2014). Being part of the neighborhood and the community evokes feelings of familiarity, security and identity, which are converted into positive emotions in old age (Glass and Balfour 2003).

From the view point of infrastructure and services, accessible spaces and appropriated services that meet the real needs of this age group contribute significantly to successful aging (Lopes et al. 2016; WHO 2007). For this reason, and as Vinuesa and Moreno (Vinuesa and Jiménez 2000, p. 63) explained, “the spatial analysis of diverse phenomena based on cartography, since it is a key element to form a correct impression of the problems” is necessary in the evaluation of successful aging. Therefore, in this study, the environment was analyzed from the subjectivity of the individual. Only through an understanding of elderly residents images of the neighborhood can we help to improve and successfully promote active aging within the city.

4. Materials and Methods

The main objective of this study was to examine the perception of neighborhoods from viewpoint of elderly residents. The specific objectives were: (1) observe how and in what way the composition of the neighborhood effects the daily life of elderly residents, according to their perception; and (2) find out what characteristics and components of the neighborhoods are related to the activity of the elderly and, more explicitly, how they correspond to the desire to pursue active aging. Hence, the study was based on three main hypotheses:

- Elderly people do most of their activities in the neighborhood, therefore the components of the neighborhood will directly affect elderly residents.

- People who live in neighborhoods better suited for their daily activities will enjoy healthier and more successful aging.

- The perception of the environment can, positively or negatively, influence individuals by creating psychological barriers that can limit their activities and, therefore, decrease successful aging.

4.1. Grounded Theory and Qualitative Analysis

I selected grounded theory by Glaser and Strauss (1967) as the method of qualitative analysis. I consider this method the most suitable for the purpose of examining the subjective experiences of the interviewees, as well as their relationships with the environment. Grounded theory is based on the paradigm of symbolic interactionism (Giraldo Prato 2011), placing people and their relationships, at the center of scientific inquiry. This analysis technique aims to explain a social problem using data and materials provided by social agents.

From the careful examination of subject’s words, meanings arise as a series of networks that are systematically related and help give meaning to the behavior of individuals (Giménez 2007; Vargas Beal 2011). Consequently, a bottom-up or inductive coding was carried out, striving to take the information directly from the transcripts and, therefore directly from the words of interviewees (Andréu Abela et al. 2007; Hernández Carrera 2014). The detailed analysis of the transcripts was made using Atlas.ti 8.

Following this methodology, and analyzing the neighborhoods separately, categories, dimensions and codes arose. The categories are groups of concepts with similar meanings and with a high level of abstraction. Each category is composed of a set of dimensions that define it. The events were coded for comparison, thus several networks and relationships among them were identified (Andréu Abela et al. 2007).

It is established that research carried out using grounded theory may be subject to verification of its methodological process, but cannot be reproduced (Corbin and Strauss 1990). The contexts from which the data arise are unique, and any change will result in new data, making them unrepeatable (Luján 2010). One of the pillars of grounded theory is that theory is built from data. However, each researcher starts from previous scientific knowledge when proposing a study; therefore, it is crucial that the theory prevents the reflexivity of the researcher from distorting the analysis of the data (McGhee et al. 2007). In this study, to ensure robust results and overcome the limitations of grounded theory, the validation of the interviews analysis was conducted by external and independent researchers, specialized in the matter. The coincidence between the categories and codes generated supports the validity and trustworthiness of this research.

Grounded theory does not set limitations on sampling; the sampling is considered finished when theoretical saturation is reached, namely when there are no subjects left who can provide new information. In practice, it is difficult to reach theoretical saturation because research depends on economic issues and time constraints. Consequently, it is possible to lose relevant information due to subordinating theoretical sampling to practical needs (Strauss and Corbin 2002). Therefore, this study did not reach theoretical saturation. A larger sample—and perhaps more balanced sample between neighborhoods and gender demographics—probably could have mitigated this inherent limitation.

4.2. In-Depth Interviews

Throughout the interviews, several aspects regarding the relationship and the interactions between subjects and their neighborhoods were addressed. Special emphasis was placed on examining the most common daily activities of the elderly, with the aim of achieving a realistic vision of their day-to-day experience. Subjects were also asked about weekends and holidays, since these days differ from their weekday routine and there are no workshops or courses at the old people center; therefore, their weekend and holiday schedule is structured differently.

The script of the interviews consisted of six open questions, from which a guided conversation based on the interests of the study was conducted. Using this method, the conversations achieved specific nuances, avoiding direct questions that could influence the subjects answers. The aim was to guide the conversation towards topics that are relevant for the research (Hernández Carrera 2014; Vargas Beal 2011). The following items were addressed in the interviews:

- Activities. Questions were asked about activities carried out throughout the week, taking into account both formal—workshops, courses, association meetings, etc.—and informal—purchases, home care, leisure activities, free time, etc.—activities. The focus of this item was to identify the physical places in which theses activities take place.

- Social relationships. Questions were asked about what kind of social interactions—friends, companions, relatives, etc.—elderly people have during the week and where those interactions usually to take place.

- Level of satisfaction with the neighborhood. The goal of this item was to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the neighborhood as perceived by elderly residents.

- Perceived health and well-being. The goal of this item was to understand the relationship between subjects physical health and their subjective experience of well-being, as well as the decision to participate or abstain from certain activities.

To achieve a trusting and pleasant interview environment, the majority of interviews were carried out in the same place as the activities of the elderly center or in another location of the subjects’ choosing, such as in their home or at local coffee shops.

4.3. Setting and Subjects

The neighborhoods selection was focused on two main features. The first was that they should be aging neighborhoods, defined by a high population density of elderly people. After studying the demographic information available in Cáceres City Council (Ayuntamiento 2018), two zones were selected. Both neighborhoods show indicators of aging populations. The second motive for selecting this neighborhood was the nursing home should be run by the Extremadura Service for the Promotion of Autonomy and Care for Dependents (SEPAD)1. This service is dedicated to promoting active aging through different activities and services. The center was a key tool in facilitating contact with individuals who fit the profile for the study2.

The two selected neighborhoods are Plaza Mayor (hereafter, Neighborhood A) and Peña del Cura (hereafter, Neighborhood B), which are just over 1 km away from each other. Despite being relatively close to each other in terms of distance, the differences between the two neighborhoods are obvious to the naked eye. Neighborhood A is located in the tourist and pedestrian area of the city close to the medieval area. Neighborhood B is located in a more recently developed area and is surrounded by green areas and social services (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Zone of influence of the selected neighborhoods.

Both neighborhoods are characterized by the gradual aging of residents and declining populations. Indeed, Neighborhood A is populated by the oldest people in the city. According to official data, the population in Neighborhood A has decreased by 5.5% and Neighborhood B has lost 3% of its population (Ayuntamiento 2018).

In this study, 32 in-depth interviews were conducted. Interviews had an average duration of 65 min, and were divided according to the two neighborhoods selected. Eighty-one percent of the sample was female, 50% of whom were widows. In the sample, 62.5% pertain to Neighborhood B, of whom 75% are women and 25% are men. The rest of the sample, 37.5%, pertains to Neighborhood A, where there is a large majority of women: 91.7% compared to 8.3% of men.

This data reflect national trends, regarding the reality facing elderly people in across Spain. This reality is characterized by feminization in the last stage of life due to cultural norms: women have older partners who they often outlive combined with the difference in life expectancy between men and women (Abellán García et al. 2018; Rodríguez et al. 2013). The average age of the sample was 73 and, regarding gender and age, no large differences between the neighborhoods were found. The objective profile of the subjects had the following characteristics: 65 years or older, living in one of the neighborhoods for more than four years, and being an independent person.

5. Results

The results obtained are grouped below into three blocks related to the feelings of loneliness or well-being perceived in the neighborhood, the influence that the neighborhood has on activities and routines, and the neighborhoods influence on social relationships, which contribute, or detract from, a sense of safety and belonging in the community.

5.1. Influence of the Neighborhood in the Well-Being, Identity, Comfort, Loneliness and Abandonment

One of the most recurrent topics, especially for residents in Neighborhood A, was the feeling of living in an abandoned zone, even though it is located in the center of the city. According to study participants, many residents have slowly been leaving their homes as a result of age or death, as explained by one resident:

In the back we had a very good neighbor, Ana but she also left, very young.The husband also left and the son has gone … he was a teacher, he went away. In the end I do not have neighbors.(I:11; N.A)3

Each time we are less because they are dying and we are elderly(I:04; N.A.)

However, in Neighborhood B, when a flat is empty, it does not take long until it is rented out again. The feeling of well-being and comfort is perceived by residents. They feel that their neighborhood is alive; at the same time, they feel safe and comfortable living there. The streets are full of people and the “lifelong bars” in the area, combined with the friendliness amongst neighbors, contribute to the sentiment of inhabitants, which is very different from those of Neighborhood A. One of the women interviewed expressed the perception of safety, comfort and familiarity that she feels in her neighborhood:

Man, that gives a lot of safety, and the bars a lot of safety because you see yourself in a bind in a moment, you go into a bar and call home. […] Because anyone follows you, you go into a bar, here we know everyone.(I: 11; N.B)

This neighborhood is far from the University of Extremadura and is well located in terms of public transport. The buildings are relatively modern, which makes it an attractive area for young people. Although the respondents of this study do not mind sharing their block of flats with students, there is some distance between the two social groups. On various occasions, the separation between We (neighbors) and They (students) is experienced. In this way, elderly neighbors distinguish themselves and the people who have been living near them for a longer period of time as people with whom they have created trusting relationships and friendships. The sentiment of separation between the two groups is expressed by this resident:

Here there are no neighbors! […]This is one is divorced, that he lives his life goes in and out and it’s over. This one there are students, the other there are students. The one above my sister-in-law, who is 86 years old, and the other over there are also students. There are 3 flats with students and 3 flats with us.(I: 13; N.B)

On the other hand, the young adult population has increased in other zones of the city. Such demographic trends are observed in our sample, at least half of the participants’ children do not live near their parents. This has two primary consequences for the life experience of the elderly.

- Family meetings could decrease in frequency due to the distance between homes and the lack of free time of young adults (Wiles et al. 2012). The modern family structure, in which both parties work outside the home, can also be an obstacle for family meetings, in addition to the shift away from the intergenerational family, which has become a concept of the past (Beard and Bloom 2015). One participant illustrates the challenges of modern family life:Because in my house I saw that my parents took care of my grandparents and that, but my mother was dedicated to the children, to the husband and to … to take care of the people. But I understand that now … if you are not able to take care of your children how are you going to be able to take care of the elderly? Well, how? … no, you do not have time. I see that my daughter, how she is going to take care of me, how? … if she keeps working taking care of her own … you know, when? How?(I.12; N.A)

- Due to the distance between homes, elderly people must travel long distances to meet with family members, requiring the use of a car, especially when the elderly have assumed the role of the informal caregivers:What happens is that as I usually have to pick up a child, I have to take the car. If not, if I do not have to pick up any children or do not have to take them anywhere, I go walking.(I: 14; N.B)

5.2. Influence of the Neighborhood on the Activities and Routines of the Elderly Residents

As Figure 2 shows, Neighborhood B is located near to one of the bigger green zones, which is called: Parque del Príncipe (“It is painted in green”). About 75% of participants mentioned this park, either because they carry out supervised activities, such as exercise organized by the local program ETC (Exercise Takes Care of you), pétanque competitions, or just because they spend part of their free time there. Most of the participants’ spare time is occupied by walking and playing with their grandchildren.

But there in the park, now when the holidays arrive we will go to the park. She (her granddaughter) loves it. Also, as it has the water and then there at the end it has the pond, there are frogs … and we are always trying to hunt a frog.(I: 02; N.B)

Nevertheless, respondents from Neighborhood A hardly talk about this park—Parque del Príncipe—or any green areas of the city. Indeed, only one resident of Neighborhood A was enrolled in the ETC program, which may be a consequence of the absence of this type of infrastructure in Neighborhood A. In fact, for some participants, a feeling of discomfort about this situation seems to arise.

In front of their house there is a park, the avenues are big … where my son lives, there is everything; supermarkets […]Because there (a newly built neighborhood) they have absolutely everything, they have primary schools, high-schools … absolutely everything. And we here … […]Because yes, it is true, we do not even have a sports center, a park, or anything …(I: 10; N.A)

In both communities, one of the most common activities, and also the main physical activity in their routines, is walking. After a careful analysis of the transcripts, two patterns were found:

- Secondary activity (derived from the primary activity). The goal of walking is doing exercise while another activity —the main activity— is being done. A significant example could be the daily shopping, related to buying vegetables, bread or fresh fruit. Instead of going straight to the local shop, the study participants looked for a longer route, going a round about way, with the only aim of walking a bit more, and, in doing so, getting the recommended amount of daily exercise.

- Main activity. As expected, for several in the sample, walking is a form of physical exercise; therefore, it is as an activity with the exclusive purpose of self care.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no such categorization in the literature. The secondary activity requires extra planning, since it consumes more time and needs to be performed together with the main activity. This planning, to include it whenever possible, shows the importance of personal and physical care amongst elderly people. Below are two examples, one from each neighborhood, of walking as secondary activity:

And then I take advantage when I go shopping and I go walking, and in this way, I do exercise too (laughs).(I: 09; N.A.)

I prefer to go far, better. Look, at the door of the house I have bread, but I go to Santa Joaquina (far) to buy it. So I get my walk, I train …(I: 15, N.B)

Regardless of the neighborhood in which they reside, many of the respondents prefer to walk along the streets rather than in parks, since they can see storefronts and other people. Of course, the physical activity is moderate but it is understood as a good way of taking care of themselves and staying active. The following interviews show the importance of walking as a healthy and necessary component in the routines of participants:

But good … well I know, I should take more care of myself. Now for example that I do not go to the gym … although it is true that I walk a lot.(I: 10; N.A)

The days that I do not come here (The Home for the Elderly) in the morning I pick up the girl, I put her in the chair and we go to the Ronda Norte, we see storefronts and things and then I come to prepare the food.

Although most participants prefer to walk through the streets than through parks, it is uncommon to choose Neighborhood A to do so. This can seem contradictory, since Neighborhood A has pedestrian streets, a big pedestrian square and is full of storefronts. According to the transcripts, the reason lies in the increasing presence of tourists and tourist geared shops. Residents of Neighborhood A do not usually go to Neighborhood B; they only go on special occasions, such as a friend or relative’s visit or cultural events. As explained by this participant, it is something exceptional, and, he and his wife, carry out their life in Neighborhood B.

Yes, but well, less because we go to the park in the morning and we always move through this circle (in their neighborhood) but in summer I go to the classical theater, when they play movies in the Balbos forum or if there is something special in the Old Town (neighborhood A), I also go.(I:16, N.B)

5.3. Influence of the Neighborhood on the Feeling of Community, Safety and Social Relationships

5.3.1. Relationships with Local Businesses: Safety

The zone of influence is found within a radius of 0.5 km and up to 1 km around residents homes (Cerin et al. 2018; Sallis et al. 2016). Inside this space, the services will have a big impact on residents well-being. Figure 2 presents a radius of 500 m around the center of the selected neighborhoods. The services within this area of influence, in each neighborhood, were grouped with the following variable: service. This variable has three elements: commerce (local businesses and shops), places of worship and elderly associations.

In Neighborhood B, the lack of businesses focused on tourism is the most distinguishing factor differentiating the two neighborhoods. Furthermore, Neighborhood B has more local businesses and shops. In our sample, the most repeated task of the week was daily shopping. A disparity was observed in the frequency of performing this task among those who live alone and those who live with others. Generally, elderly people who live alone do not need to do a big shop, for instance, once a month; instead, they go to the grocery store a few times per week. Conversely, if there are several elderly people living with relatives in the same home, they usually go to a supermarket about once a month to do a big shop.

And for me all this is very familiar, because … I have everything and more, all kinds of shops … anyway, if I do not want to leave the neighborhood, I do not leave, I am very good here I am very happy.(I:18; N.B)

I think, I do not know the other neighborhoods but I think … that you have everything you need at hand. You have the church; you have the shops … many supermarkets.(I: 17; N.B)

Nevertheless, after a thorough analysis of the interviews, I found that the difference in how and where the purchases are made lies in the composition of the neighborhood. The main factor is the contrast between the types of stores found in each neighborhood. In Neighborhood A, the prices are higher than in Neighborhood B, due to tourism. Even the few remaining local shops are more expensive:

There is a small supermarket but it is very expensive and the shops are also expensive those shops that have a little bit of everything.(I: 03, N.A)

Consequently, in Neighborhood B, it is a voluntary choice to go shopping outside of the zone of influence. Nonetheless, elderly people in Neighborhood A mention the difficulty of finding good grocery stores in their immediate surroundings. Therefore, leaving their area of influence to go shopping has become necessary. Below are two examples, one for each of the neighborhoods:

Yes, but well, when we have to do a big shop for everything, we go to Carrefour (hypermarket). But come on, if not, here there is a very good assortment of supermarkets.(I: 16; N.B)

Yes, but well, when we have to do a big shop for everything, we go to Carrefour (hypermarket). But come on, if not, here there is a very good assortment of supermarkets.(I: 16; N.B)

Ah yes, there is nothing to buy. You have to take the car and go to Mercadona (big supermarket) or Eroski (hypermarket). There are two or three local shops but come on, to do a shop, a real shopping … you have to go outside.(I: 08, N.A)

Perhaps the main drawback is related to the feeling of dependency because the elderly rely on other family members for even this, apparently, simple task. Furthermore, the dependency increases, because their relatives are the ones with the car:

I already told you, my daughters have to accompany me to do the shopping, at Eroski (hypermarket) up there (by car)(I: 04; N.A)

One of the most interesting results is related to the lack of trusting relationships with local workers in Neighborhood A. However, in Neighborhood B, trusting relationships with employees have clearly developed. The trust created between the client and the attendant helps to nurture a pleasant shopping atmosphere. For this reason, some people, despite going to the hypermarket where the products are usually cheaper, prefer to do their shopping in the neighborhood, because they rely on the shopkeepers and the specific products they carry:

I always buy fruit, fish and meat in the neighborhood. I see it like that, in the big supermarkets, I barely buy those kinds of products. Here is my butcher, my fruit seller and my daughters order me the fruit, it is very good fruit.(I: 14; N.B)

This confidence leads toward a sense of safety, especially for people who live alone. The attention shown by the shopkeepers regarding their health combined with the short conversations about their daily lives, seems to have a positive impact on elderly residents. Shopping in the neighborhood allows them to feel comfortable and safe in a familiar atmosphere, as this interviewee stated:

There the boy from the pharmacy every time I pass, he says “oh well, here is the joy!” (Laughs). […]Yes, yes, it is the one I go to because it is the closest one. They already know me from the years I have been here, you know.(I: 10; N.B)

One of the most significant factors influencing participants shopping experiences was the ability to make orders over the phone. The employees even bring the products to their homes for free. This service is not only available at grocery stores but also can be found at other types of stores, such as clothing stores. The construction of trusting relationships reaches its zenith when the customers who, due to age related limitations, such as lack of flexibility and balance, do not feel comfortable trying on clothes in the shop and the staff allow them to try on within the comfort of their homes:

But then if, in the shops, everyone knows you, they trust you … they let you take the clothes to your house to try on, I … for me everywhere. […]In the places where I already have trust and where I almost always go.(I: 18; N.B)

Unfortunately, these examples of safety and familiarity with shopkeepers, mentioned above, have not been found in interviews from Neighborhood A.

5.3.2. Religion and Elderly Associations

Religion is part of the profile of the elderly person (Cordero del Castillo 2007). Our sample is not an exception. About 65% of those interviewed are Catholics and practice their religion, going to church regularly, even several times a week. Hence, the church is an essential part of their environment:

On Sundays and every day. I have the church here very close, Santo Domingo and I go there to the friars.(I: 02, N.A)

For this woman, the importance of the church is clear: it is an almost daily task. Furthermore, in the rest of the conversation, it could be concluded that this woman enjoys going every day. This activity is facilitated by the amount of temples and even a Co-Cathedral in Neighborhood A. In addition, in Neighborhood A, the distance between homes and temples is shorter, facilitating the attendance of the faithful. By contrast, in Neighborhood B, there is only one chapel. Consequently, the celebrations of key religious events, such as Holy Week or local saint days, take place in Neighborhood A. This finding implies that residents in Neighborhood B could go to Neighborhood A to participate in religious events. However, the underlying issue, according to the results, is that Neighborhood A has been relegated to religious events or holidays and there are no other reasons to go there.

I really like the Old Town, a lot. Every time someone comes I go there, although, usually, I do not go alone. But when someone comes, relatives or friends, always, I always take them to the historic center.(I: 14; N.B)

As explained, one of the selection requirements for the neighborhoods used in this study was to have a hogar de mayores—an institution for the elderly. The presence of an official location where activities and workshops for seniors are offered was key in this study, since it provided information regarding the types of activities and workshops available to seniors as well as providing me an appropriate channel for initiating contact.

Both institutions are under the supervision of the SEPAD (see Figure 2). Their workshops are similar, each of them offering computer or painting courses, and gym activities, among others. One of the physical activities offered that attracted my attention was the petanque competition, which is only offered in Neighborhood B, due to its proximity to the park (Parque del Príncipe), where this activity can be performed.

And then Monday, Wednesday and Friday we walk here from 10 to 11 (ETC program). And then at 11 on Mondays and Thursdays we stay at the park (Parque del Príncipe) because we play petanque. Then we go walking, we say goodbye, people leave and a few of us stay with others who come from here from the Home (Hogar de mayores), and we play petanque.(I: 17; N.B)

Once again, the characteristics of the neighborhood play a crucial role in the opportunities of elderly residents. In addition, in Neighborhood A, another drawback was observed. The zone of influence of the Neighborhood B is composed of a greater number of locations where workshops and courses for elderly can take place. As a result, residents of Neighborhood A are forced to leave their neighborhood if they want to enjoy such activities.

But we do not have parks, we have absolutely nothing. In other words, it is very nice because you are in the historic center and if you like stones and such … but of course, you do not have large avenues …(I: 10; N.A)

6. Discussion

The change in the physiognomy of the population in the selected neighborhoods is a reality. In Neighborhood A, where buildings are older and there is less infrastructure and services, the change is more noticeable. Several factors have contributed to this situation: deterioration and abandonment of houses, the transformation of buildings into tourist apartments, and depopulation, have contributed to a feeling of insecurity amongst the elderly people that still inhabit the neighborhood. As several papers note (Buffel et al. 2012; Wiles et al. 2012), this feeling of insecurity in the neighborhood could have pernicious repercussions on the health of residents. In addition, the study participants perceive their neighborhood as if it were a ghost town. This is translated into a feeling of loneliness that is one of the most frequent problems among the elderly (Bazo 1992). As a result, the loneliness and the feeling of insecurity could limit the number of times seniors go outside the home and the duration of their time outside. In this way, leaving the perceived protection of the home at certain times of day could be a problem for our group, making them prisoners of their own homes (Phillipson 2011).

The physiognomy of the population has also changed in Neighborhood B, mainly because empty flats are rented to students or other temporary renters. This has created a division into two groups, elderly and the others, commonly younger people. This differential gap has not been the direct outcome of an age difference, but is due to an idea of stability and continuity of relationships between elders. As a result, building trusting relationships with the younger residents is unlikely, especially compared to relationships with “lifelong neighbors” (Conde et al. 2018).

Moderate exercise is essential for successful aging (Lee et al. 2012). However, the amount and diversity of physical activities can be limited by available infrastructure in the neighborhood (Bauman et al. 2012; Conde et al. 2018). In this regard, almost all residents of Neighborhood B walk through the neighborhood or its surroundings. In Neighborhood A, when “walking” is the main activity, less than half of the sample chose their neighborhood or its surroundings to walk in. However, when “walking” is a secondary activity, almost all of them go to other areas of the city, since they do their shopping or their workshops there.

One of the central pillars of the WHO on successful aging is based on the concept that older people should remain free and autonomous in all areas of interaction with society. The lack of services, mainly grocery stores in Neighborhood A, limits this principle and forces people to depend on others to do something basic such as shopping, limiting their autonomy. This type of situation could lead to a feeling of uselessness that could have a negative health effects for the elderly (Almeida 2014; Lecovich 2014). Buildings, businesses and other physical infrastructure in a neighborhood are not the only deciding factors in a neighborhood, the relationships with other people also have a significant impact. The trusting relationships, constructed from daily interaction with neighbors and with the employees at local businesses, generates security for the elderly, positively contributing to their health and well-being (Buffel et al. 2012; Glass and Balfour 2003).

Another feature that stood out in this study is that religion remains a key element in the daily life of elderly people. The study of Rodríguez et al. (2013) affirms that religion in Spain is one of the most valued and important aspects for the elderly, together with friendship, spare time, money and volunteering. The truth is that communities are not only composed of infrastructure, they need families, people living together, relationships, shared public spaces, and places of worship (Lecovich 2014). In this study, an important feature in day-to-day life of the elderly was to have an accessible church to practice their faith.

Places specifically designed for the elderly and their activities, such as homes or senior centers and associations, are essential for elderly residents. Lifelong learning is also one of the key characteristics of active aging, due to its multiple benefits (Sancho et al. 2015). Lifelong learning allows elders to continue socialization through interactions with other people. The positive consequences are not only found in the psychological dimension, but also in the physical health of participants. The activity of dressing, getting ready and attending any of these centers or activities, combined with walking to the location, contributes to the improve health and well-being of participants. In addition, participation in workshops, activities and courses that are attractive and suitable for them, is an enriching experiences. They feel useful within society and they interact with others. They also have material for conversations with family members regarding their new knowledge, allowing them to share what they have learned. Therefore, and in concurrence with the interviews, it seems necessary to increase the variety and quantity of workshops, activities and courses for seniors. As in the case of local shops, Neighborhood B is better valued in this study, since it offers a wider range of activities.

7. Conclusions

Through this qualitative research, it has been possible to understand the subjective reality of two neighborhoods. The study was carried out in an aspiring age-friendly city, of medium-sized, within the European Union (Cáceres, Spain). To the best of my knowledge, these types of cities are not usually studied in the literature. The qualitative approach aimed to understand the interaction, both physical and social, between the subjects and their environment. The analysis of the transcripts suggests two types of conclusions: on the one hand, conclusions related to the social relationships, and, on the other hand, conclusions related to the physical environment.

The research was mainly based on activity theory of aging and the WHO pillars of active aging. All of them highlight the desire of the elderly to be active and participate in society. This premise has been demonstrated throughout the paper and several examples have been selected to show the desire to be autonomous and independent in old age. In turn, the ability of these people to adapt to their new physical and social conditions shows that they are far from the preconceived idea of old age, a life stage stereotypically characterized by weakness or sadness. This success, and desire to continue living a full life, has been illustrated in the self-care of both body and mind practiced by study participants. Finally, the participation in different collective activities, both educational and leisure, demonstrates the importance of socialization for the elderly and the importance of interaction with the greater community.

This paper references several studies and theories that support the concept that the physical environment consists of much more than buildings, as demonstrated by our sample. Supporting this idea, the subjective image of each neighborhood obtained through the interviews is added here.

Many negative factors were found in Neighborhood A. Some of these factors are related to a lack of appropriate infrastructure, which has been aggravated by the absence of urban policies directed towards elderly residents. Accordingly, another negative factor is the scarcity of places that encourage socialization among residents, including the practice of outdoor activities such as exercise or leisure activities. Therefore, the absence of grocery stores, places to conduct workshops and green zones, result in a decrease in the quality of life for residents. From the psychological point of view, the most harmful characteristic of Neighborhood A has been identified as the following: the perceived insecurity, a consequence of depopulation and tourism. In the case of tourism, it manifests itself in the lack of social interaction with visitors and, therefore, the inability to create trusting relationships. In addition, trusting relationships with local employees in the area have disappeared, since business are oriented towards tourists.

In agreement with the information gathered from the interviews, these negative factors are the product of the structural elements of the neighborhood itself, since they are specific to Neighborhood A and were not identified in Neighborhood B. This research provides valuable subjective information, hardly observable without a qualitative approach. It provides details that go beyond the architecture of the neighborhoods and the amount of services available, revealing the real use and perception of the neighborhood features. Therefore, it demonstrates the physical, psychological, social and emotional dimensions of the neighborhood and how they influence elderly residents.

Funding

This work has not received any type of funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the SEPAD for the help they provided; all 32 study participants; Jesús Rivera from the University of Salamanca, for the effort made as my doctoral advisor and for providing technical support on this paper; and Annamalka Chadwick for help revising the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abellán García, Antonio, Alba Ayala García, Julio Pérez Díaz, and Rogelio Pujol Rodríguez. 2018. Un perfil de las personas mayores en españa, 2018. indicadores estadísticos básicos. In Informes Envejecimiento en Red. Madrid: CSIC-Instituto de Economía, Geografía y Demografía (IEGD), pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, Maria. 2014. A identidade na velhice. In Envelhecimento, Saúde e Cidadania. Coimbra: UICISA: E, pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Andréu Abela, Jaime, Antonio García-Nieto, and Ana Pérez Corbacho. 2007. Evolución de la teoría fundamentada como técnica de análisis cualitativo. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuntamiento, de Cáceres. 2018. Análisis de las cifras de población obtenidas a 01 de enero de 2018. Cáceres: Ayuntamiento de Cáceres. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Adrian, Rodrigo Reis, James Sallis, Jonathan Wells, Ruth Loos, Brian Martin, and Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. 2012. Correlates of physical activity: Why are some people physically active and others not? The Lancet 380: 258–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazo, María Teresa. 1992. La nueva sociología de la vejez: De la teoría a los métodos. Reis, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazo, María Teresa, and Benjamín García Sanz. 2014. Envejecimiento y sociedad: Una perspectiva internacional. Edited by Pilar Rodriguez. Madrid: Médica Panamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Hon Prof John, and David Bloom. 2015. Towards a comprehensive public health response to population ageing. Lancet (London, England) 385: 658–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, Tine, Chris Phillipson, and Thomas Scharf. 2012. Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’ cities. Critical Social Policy 32: 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, Ester, Terry L. Conway, Marc A. Adams, Anthony Barnett, Kelli L. Cain, Neville Owen, Lars B. Christiansen, Delfien Van Dyck, Josef Mitáš, Olga L. Sarmiento, and et al. 2018. Objectively-assessed neighbourhood destination accessibility and physical activity in adults from 10 countries: An analysis of moderators and perceptions as mediators. Social Science & Medicine 211: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Alfredo Alfageme. 2005. Desigualdades mundiales ante el proceso de envejecimiento demográfico. Recerca: revista de pensament i anàlisi 5: 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hong, Jeffrey C. Kwong, Ray Copes, Karen Tu, Paul J. Villeneuve, Aaron Van Donkelaar, Perry Hystad, Randall V. Martin, Brian J. Murray, Barry Jessiman, and et al. 2017. Living near major roads and the incidence of dementia, parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis: A population-based cohort study. The Lancet 389: 718–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, Paloma, Marta Gutiérrez, María Sandín, Julia Díez, Luisa Borrell, Jesús Rivera-Navarro, and Manuel Franco. 2018. Changing neighborhoods and residents’ health perceptions: The heart healthy hoods qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, Juliet M., and Anselm Strauss. 1990. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology 13: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero del Castillo, Prisciliano. 2007. Situación social de las personas mayores en españa. Humanismo y trabajo Social 5: 161–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Isabel. 2012. O uso das tecnologias digitais entre os seniores: Motivações e interesses. Sociología, problemas e práticas 68: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. 2017. estructura demográfica y envejecimiento de la población. Luxembourg: Eurostat (Statistics Explained). [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, J. I. Rengifo, A. J. Campesino Fernández, and J. M. Sánchez Martín. 2015. El turismo en la ciudad de cáceres (1986-2010): un cuarto de siglo emblemático. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 67: 375–401. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilov, L. A., and P. Heuveline. 2003. Aging of population. In The Encyclopedia of Population. Edited by P. Demeny and G. McNicoll. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, Rubén Cuñat. 2007. Aplicación de la teoría fundamentada (grounded theory) al estudio del proceso de creación de empresas. In Decisiones basadas en el conocimiento y en el papel social de la empresa: XX Congreso anual de AEDEM. Vigo: Asociación Española de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa (AEDEM), p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo Prato, Marisela. 2011. Abordaje de la investigación cualitativa a través de la teoría fundamentada en los datos. Ingeniería Industrial. Actualidad y Nuevas Tendencias 6: 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, Thomas A., and Jennifer L. Balfour. 2003. Neighborhoods, aging, and functional limitations. Neighborhoods and Health 1: 303–34. [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst, Robert J. 1963. Successful aging. Processes of Aging: Social and Psychological Perspectives 1: 299–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Carrera, Rafael Manuel. 2014. La investigación cualitativa a través de entrevistas: Su análisis mediante la teoría fundamentada. Cuestiones Pedagógicas 23: 187–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffimann, Elaine, Henrique Barros, and Ana Ribeiro. 2017. Socioeconomic inequalities in green space quality and accessibility—Evidence from a southern european city. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, Sandra C. 1983. The meaning of place in old age. In Aging and Milieu: Environmental Perspectives on Growing Old. New York: Academic Press, pp. 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- IEEX. 2018a. Datos padrón extremadura, resultado detallados 2019. Mérida: Instituto de estadística de extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- IEEX. 2018b. Datos padrón municipios de cáceres, resultado detallados 2018. Mérida: Instituto de estadística de extremadura. [Google Scholar]

- IMF. 2018. GDP by Countries. Washington: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- INE. 2018a. Indicadores de mortalidad: esperanza de vida a los 65 años; Madrid: INE.

- INE. 2018b. Instituto nacional de estadística: Indicadores de estructura de la población; Madrid: INE.

- INE. 2019. Instituto nacional de estadística: Población de 16 y más años por nivel de formación alcanzado; Madrid: INE.

- Lawton, M. P. 1989. Behavior-relevant ecological factors. In Social Structure and Aging Psychological Processes. Edited by K. Schaie and C. Schooler. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlabaum Associates, Inc., pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lecovich, Esther. 2014. Aging in place: From theory to practice. Anthropological Notebooks 20: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I.-Min, Eric J. Shiroma, Felipe Lobelo, Pekka Puska, Steven N. Blair, Peter T. Katzmarzyk, and Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. 2012. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet 380: 219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Alexandra, Teresa Pinto, and Rute Lemos. 2016. Age-friendly cities and the who checklist: Lessons from a portuguese survey. In International Perspectives on Age-Friendly Cities. Edited by K. G. Fitzgerald and F. G. Caro. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Luján, Noemí. 2010. Lo cualitativo como estrategia de investigación: Apuntes y reflexiones. In El arte de investigar. Edited by Pablo Mejía and José Manuel Juárez y Sonia Comboni. México: Mc Editores, pp. 213–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- McGhee, Gerry, Glenn R. Marland, and Jacqueline Atkinson. 2007. Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing 60: 334–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, A., and C. García. 2014. Análisis del envejecimiento demográfico en extremadura a escala de detalle: Distritos y secciones censales. In Actas XIV Congreso Nacional de la Población. Cambio demográfico y socio territorial en un contexto de crisis. Grupo de Población de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles. Sevilla: University of Sevilla, pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, Chris. 2011. Growing Older in Urban Environments: Perspectives from Japan and the UK: A Report on a Symposium Held in Church House Conference Centre, Westminster, London, March 29–30 2011. London: International Longevity Centre-UK. [Google Scholar]

- Puga González, María Dolores, and Antonio Abellán García. 2006. Las escalas territoriales del envejecimiento. SEMATA, Ciencia Sociais e Humanidades 18: 121–41. [Google Scholar]

- Remy, Jean, and Liliane Voyé. 1976. La ciudad y la urbanización. Madrid: Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local. [Google Scholar]

- Requena, Antonio Trinidad. 2006. El nuevo discurso de los mayores: La construcción de una nueva identidad social. Revista Española de Sociología 6: 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, G., P. Rodríguez, P. Castejón, and E. Morán. 2013. Las personas mayores que vienen. Autonomía, solidaridad y participación social. Madrid: Fundación Pilares. [Google Scholar]

- Ronzi, Sara, Daniel Pope, Lois Orton, and Nigel Bruce. 2016. Using photovoice methods to explore older people’s perceptions of respect and social inclusion in cities: Opportunities, challenges and solutions. SSM-Population Health 2: 732–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, James F., Ester Cerin, Terry L. Conway, Marc A. Adams, Lawrence D. Frank, Michael Pratt, Deborah Salvo, Jasper Schipperijn, Graham Smith, Kelli L. Cain, and et al. 2016. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. The Lancet 387: 2207–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, James F., Neville Owen, and E. Fisher. 2015. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice 5: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, Mayte, Dolores Puga González, and Aina Faus Bertomeu. 2015. Deconstruyendo la vejez, construyendo la atención a los mayores. entrevista con mayte sancho. Encrucijadas-Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales 10: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sancho Prieto, Daniel, Diego Herranz Andújar, and Pilar Rodríguez Rodríguez. 2015. Envejecer sin ser mayor: Nuevos roles en la participación social en la edad de jubilación. Madrid: Fundación Pilares para la Autonomía Personal. [Google Scholar]

- Stafford, Mai, and Michael Marmot. 2003. Neighbourhood deprivation and health: Does it affect us all equally? International Journal Epidemiology 32: 357–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauss, Anselm L., and Juliet Corbin. 2002. Bases de la investigación cualitativa: Técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. Medellín: Universidad de Antioquia. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Beal, Xavier. 2011. ¿Cómo hacer investigación cualitativa? Una guía práctica para saber qué es la investigación en general y cómo hacerla, con énfasis en las etapas de la investigación cualitativa. México: ETXETA. [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa, Julio, and Antonio Moreno Jiménez. 2000. Sociodemografía. In Gerontología Social. Madrid: Pirámide, pp. 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2002. Active Ageing: A Police Framework. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. 2007. Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins, Richard D., Paul F. D. Higgs, Martin Hyde, and David B. Blane. 2004. Quality of life in the third age: Key predictors of the casp-19 measure. Ageing & Society 24: 693–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, Janine L., Annette Leibing, Nancy Guberman, Jeanne Reeve, and Ruth E. S. Allen. 2012. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist 52: 357–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | It is an official institution dependent of the autonomous community of Extremadura (Spain) https://saludextremadura.ses.es/sepad/inicio. |

| 2. | I would like to thank SEPAD and their related entities, the Nursing Homes, the workshops of the University of the Third Age (Universidad Popular), the Exercise Take Care program of the City Council and the University of the Elderly (Universidad del Mayor), for facilitating contact with interviewees. |

| 3. | I:11 means interviewee number 11 and N.A means Neighborhood A. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).