The Use of Social Digital Networks by NGDO from a Social Marketing Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theory Framework and Hypothesis Development

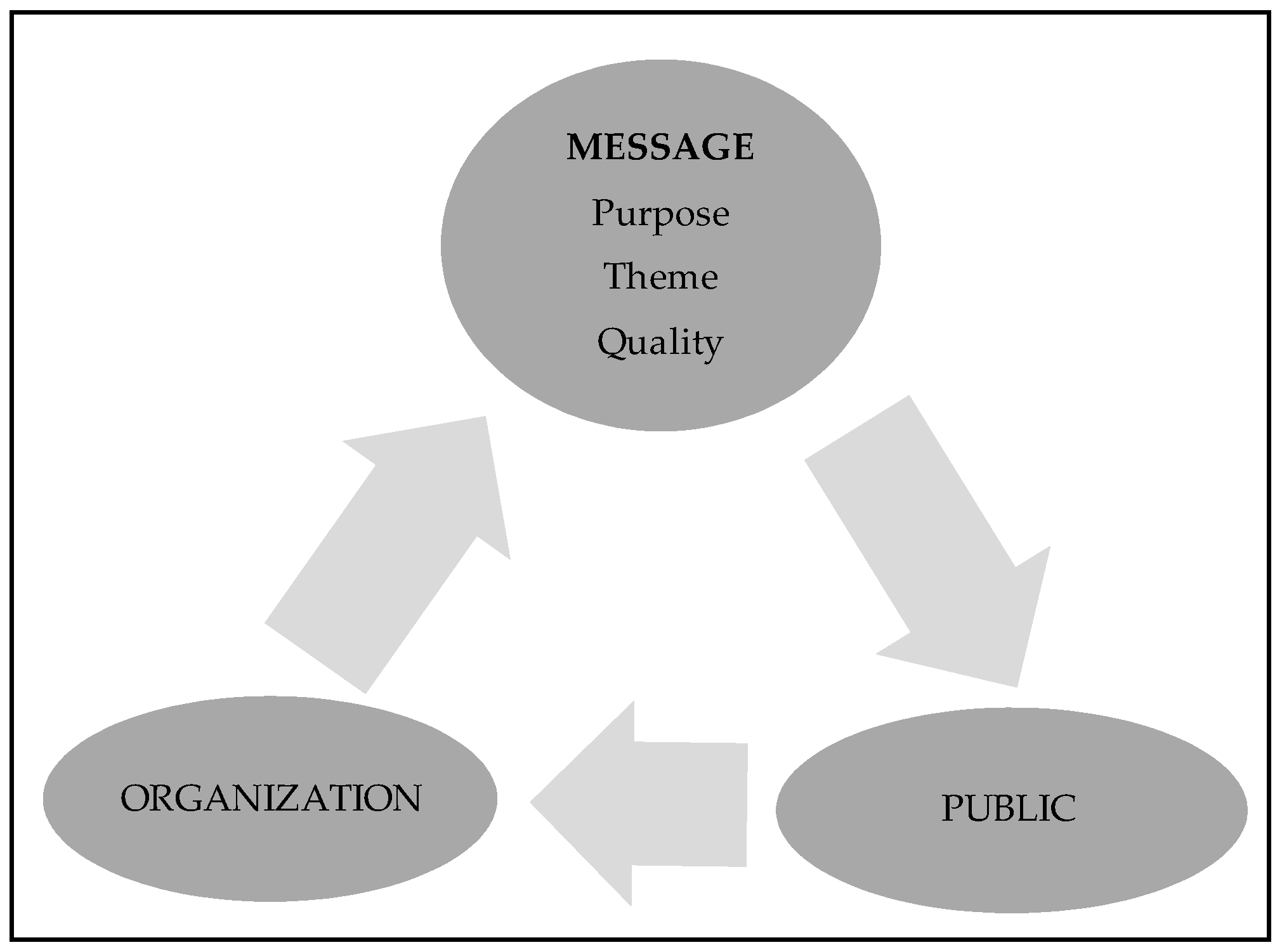

2.1. Social Marketing and Effectiveness

“Social marketing is the adaptation of commercial marketing technologies to programs designed to influence the voluntary behavior of target audiences to improve their personal welfare and that of the society of which they are a part”(p. 110)

2.2. The Reaction from the Public or Interactions on Social Digital Network

- The number of responses or comments from fans;

- The actions associated with each message, such as the number of favorite messages, or “likes”;

- The number of times a publication has been shared.

2.3. The Purpose of the Message

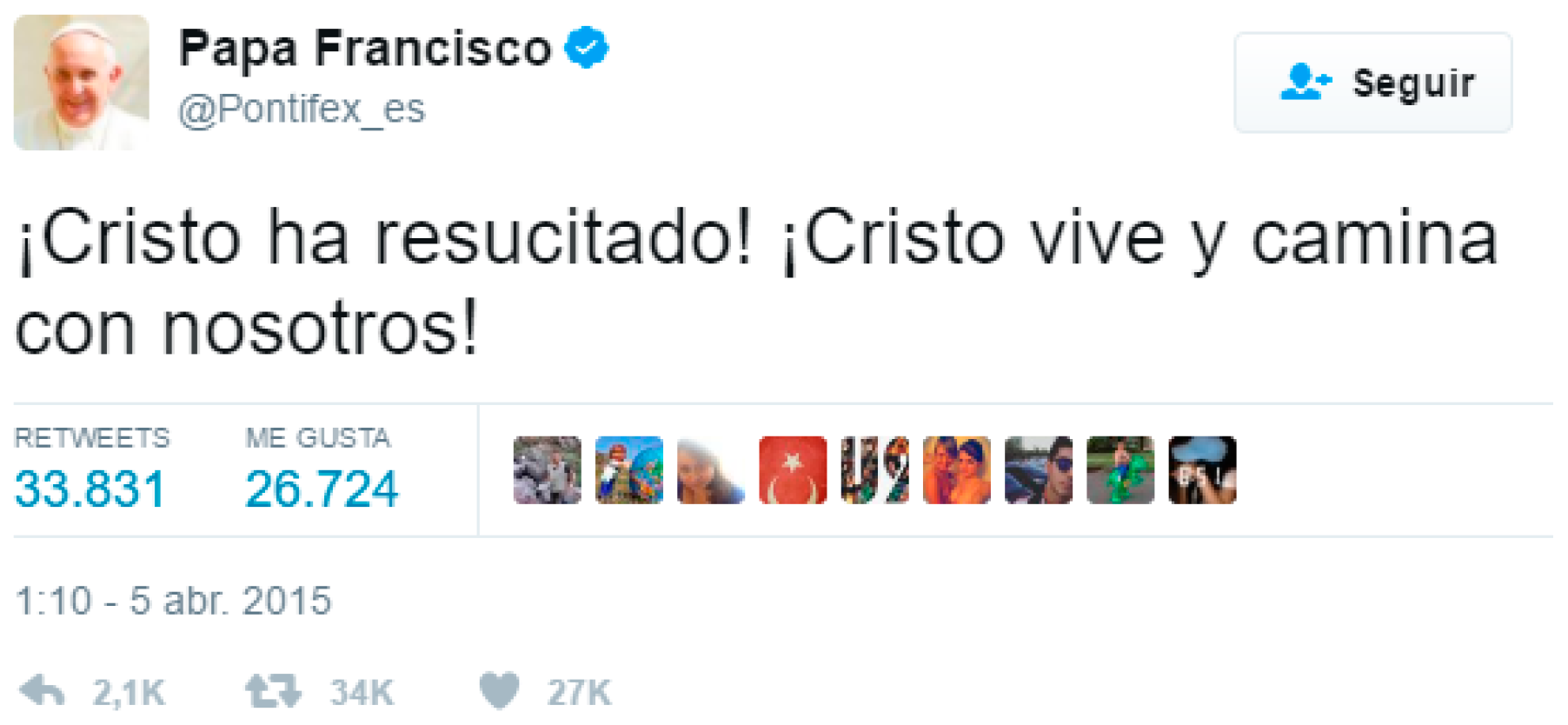

2.4. The Theme of the Message

2.5. The Quality of the Message

3. Materials and Methods

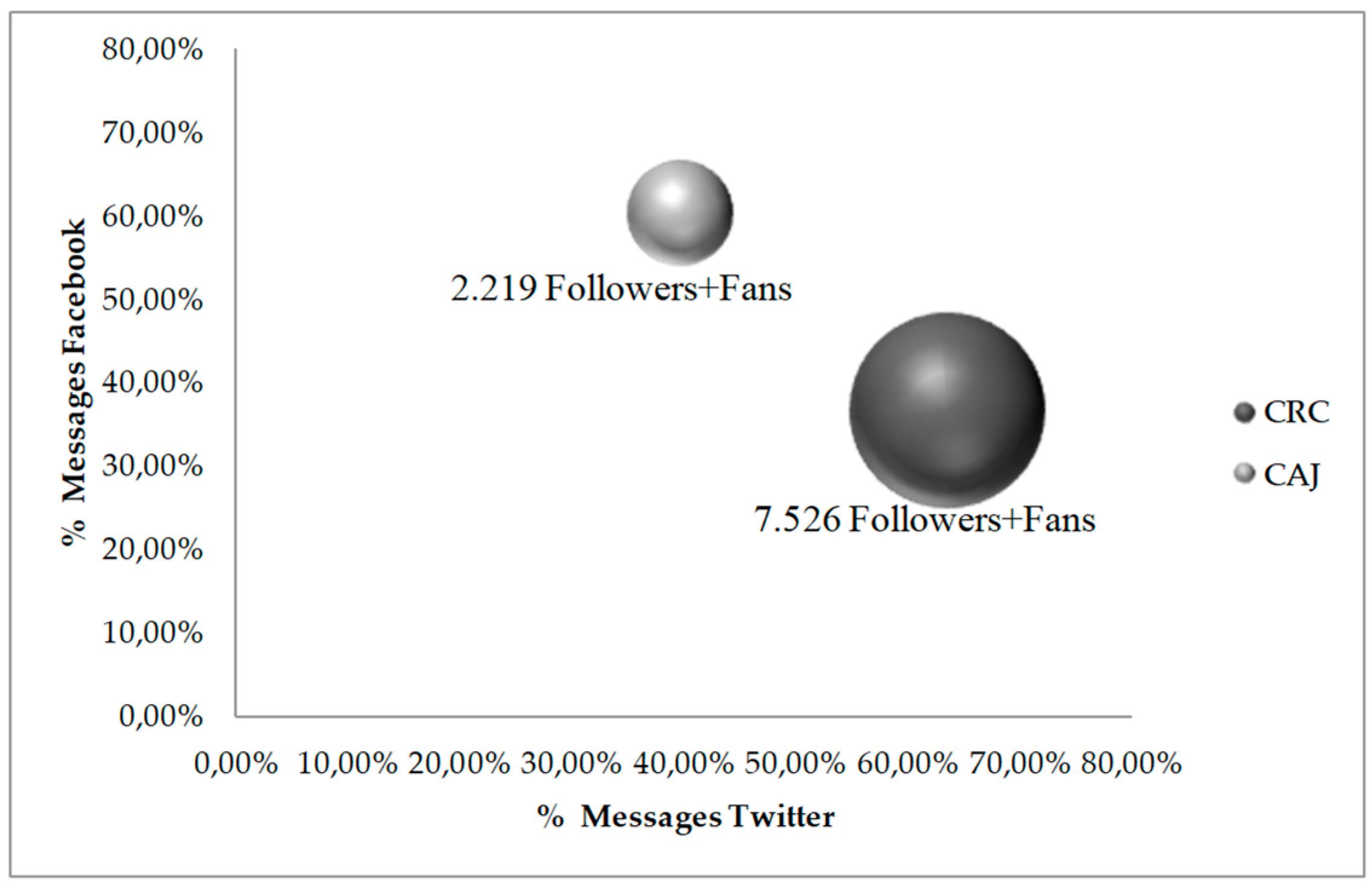

3.1. Non-Govermental Development Organizations and Selection of Social Media

3.2. Investigation Approach and Information Gathering Techniques

3.2.1. Pre-Analysis: Identification of the Sample and Variables

3.2.2. Data Extraction and Information Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

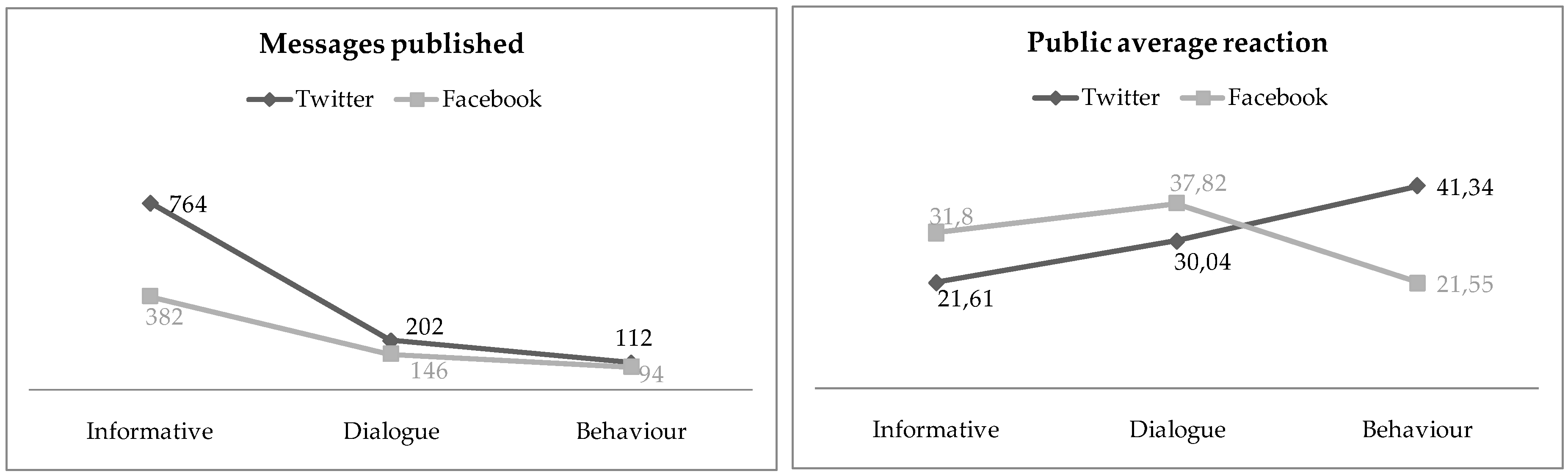

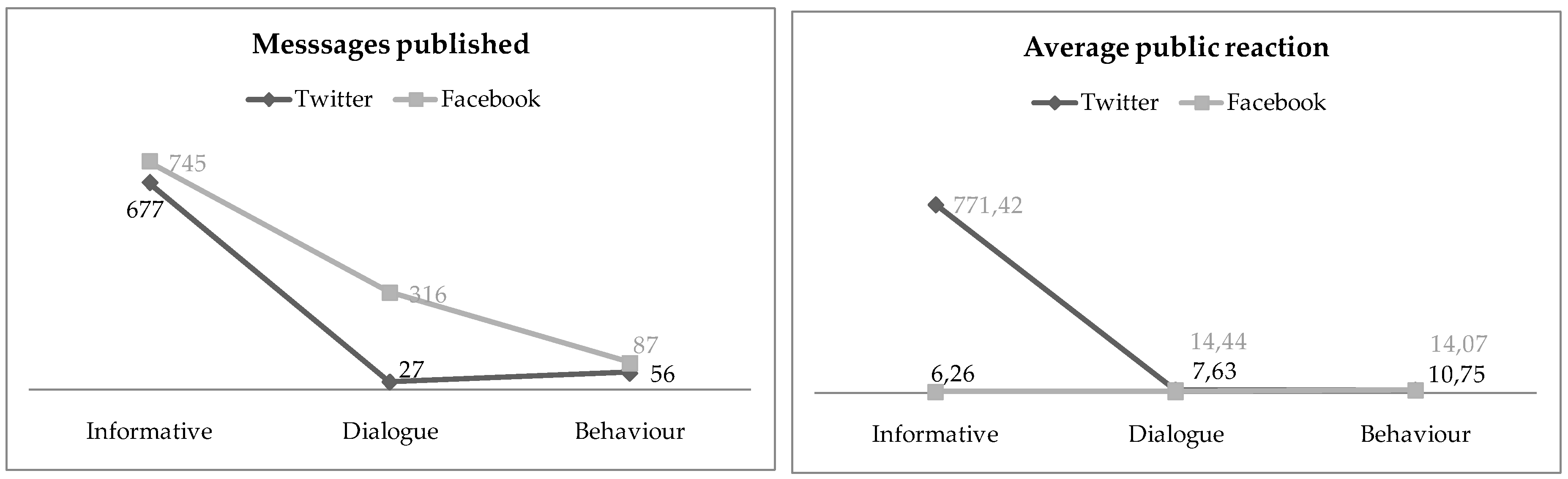

4.1. The Purpose of the Message

4.2. The Theme of the Message

4.3. The Quality of the Message

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Hypothesis (Twitter) | NGOD | Link | p Value | Aceptac. |

| H1. The purpose of the message influences the public’s reaction, both on Twitter and on Facebook. | CAJ | Greater reaction of the public in informative messages | p = 0.000 | Yes |

| CRC | Greater public reaction to behavioral messages | p = 0.001 | Yes | |

| H2. The reaction of the public is different depending on the theme of the message, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater reaction of the public in religious messages | p = 0.003 | Yes |

| CRC | Greater reaction of the public in emergency messages | P = 0.000 | Yes | |

| H3. The reaction of the public is different depending on the format used in the messages, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater reaction of the public in messages with text only | p = 0.494 | No |

| CRC | Greater reaction of the public in messages with text and photo | p = 0.000 | Yes | |

| H4. The number of mentions and hashtags influences the reaction of the public, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater reaction of the public in messages containing 0 and 1 mentions, and between 1 and 2 hashtags | M. p = 0.104 | M. No |

| H. p = 0.032 | H. Yes | |||

| CRC | Greater reaction of the public in messages that have 0 and 1 hashtag, and 0–1 mention | M. p = 0.024 | M. Yes | |

| H. p = 0.119 | H. No | |||

| H5: The reaction of the public depends on the link, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater public reaction if the message does not contain links | p = 0.248 | No |

| CRC | Greater public reaction if the message contains links | p = 0.0009 | Yes | |

| Hypothesis (Facebook) | NGOD | Link | p Value | Acept. |

| H1. The purpose of the message influences the public’s reaction, both on Twitter and on Facebook. | CAJ | Greater reaction of the audience in dialogue messages | p = 0.000 | Yes |

| CRC | Greater reaction of the audience in dialogue messages | p = 0.003 | Yes | |

| H2. The reaction of the public is different depending on the theme of the message, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater reaction of the public in emergency messages | p = 0.000 | Yes |

| CRC | Greater reaction of the public in prevention messages | p = 0.000 | Yes | |

| H3. The reaction of the public is different depending on the format used in the messages, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater public reaction in video messages | p = 0.030 | Yes |

| CRC | Greater reaction of the public in messages with text and video | p = 0.000 | Yes | |

| H4. The number of mentions and hashtags influences the reaction of the public, both on Twitter and Facebook. | CAJ | Greater public reaction in messages containing between 1 and 2 hashtags and mentions | M. p = 0.176 | M. No |

| H. p = 0.182 | H. No | |||

| CRC | Greater public reaction in messages that have between 3 and 5 hashtags and between 0 and 1 mention | M. p = 0.609 | M. No | |

| H. p = 0.936 | H. No | |||

| H5: The reaction of the public depends on the link, both on Twitter and Facebook | CAJ | Greater public reaction if the message does not contain links | p = 0.000 | Yes |

| CRC | Greater public reaction if the message does not contain links | p = 0.001 | Yes |

References

- Aldás, Eloísa, and Montserrat Santolino. 2015. La Investigación en Comunicación y Cooperación en los nuevos escenarios de movilización social: ONGD, objetivos de justicia social y eficacia cultural. Revista de La Asociación Española de Investigación de La Comunicación 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, Alan. 1994. Social Marketing: Its Definition and Domain. Journa] of Public Policy & Marketing 13: 108–14. [Google Scholar]

- Antevenio. 2016. Estudio sobre el sector de las ONGs en España. Parte II. Available online: https://www.antevenio.com/blog/2016/04/ii-estudio-sobre-el-sector-de-las-ongs-en-espana-realizado-por-guiaongs-asturianos-y-gallegos-los-mas-solidarios-con-la-labor-de-las-ongs/ (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Arroyo, Isidoro, Miguel Baños, and Teresa Rodríguez. 2009. Social advertising in the NGOs of Cordoba (Argentina). Message construction profiles. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 64: 1011–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, Isidoro, Miguel Baños, and Teresa Rodríguez. 2012. Modelo de investigación de las piezas audiovisuales de las organizaciones del tercer sector en redes sociales 1. Paper presented at the III Congrés Internacional Associació Espanyola d’Investigació de La Comunicació, Tarragona, Spain, January 18–20; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo, Isidoro, Antonio J. Baladró, and Rebeca Martín. 2013. Social Network Communication: Perceptions and Uses for Spanish NGOs. Cuadernos. Info 32: 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baamonde, Xosé Manuel, Alberto Pena, and Xabier Martínez. 2015. La gestión de la comunicación digital como herramienta de transparencia y rendición de cuentas en la ONGDs. Revista de La Asociación Española de Investigación de La Comunicación 2: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bales, Kevin. 1996. Measuring the Propensity to Volunteer. Social Policy & Adminstration 30: 206–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, Laurence. 1983. Análisis de contenido. Madrid: Ediciones Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Bellucci, Marco, and Giacomo Manetti. 2017. Facebook as a tool for supporting dialogic accounting? Evidence from large philanthropic foundations in the United States. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 30: 847–905. [Google Scholar]

- Berends, Lynda, and Rebecca Halliday. 2018. Capacity building and social marketing promotes healthy lifestyle behaviour in an Australian Aboriginal community. Australian Journal of Rural Health 26: 279–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, Jay M., Darren Mays, and Amanda K. Hall. 2012. Social marketing at the right place and right time with new media. Journal of Social Marketing 2: 130–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, Yarimar, and Jonathan Rosa. 2015. #Ferguson: Digital protest, hashtag ethnography, and the racial politics of social media in the United States. American Ethnologist 42: 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordarie, Jimmy. 2019. Social representations and social marketing: Effectiveness of awareness campaigns on the representation of public policies. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 24: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briones, Rowena L., Beth Kuch, Brooke F. Liu, and Yan Jin. 2011. Keeping up with the digital age: How the American Red Cross uses social media to build relationships. Public Relations Review 37: 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Suzan, and Alena Soboleva. 2011. Interactive or reactive? Marketing with Twitter. Journal of Consumer Marketing 28: 491–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, Marylyn, and Sally Dibb. 2013. Social marketing transformed: Kotler, Polonsky and Hastings reflect on social marketing in a period of social change. European Journal of Marketing 47: 1376–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casais, Beatriz, and João F. Proença. 2012. Inhibitions and Implications Associated with Celebrity Participation in Health-Related Social Marketing: An Exploratory Research Focused on HIV Prevention in Portugal. Health Marketing Quarterly 29: 206–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, Cristina Martorell, and Carolina Serra Folch. 2018. The Presence of NGOs on Instagram: A Case Study of Proactiva Open Arms. Trípodos 43: 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, Marco, Rogan Petrie, and Clarence Wardell. 2014. Fundraising through online social networks: A field experiment on peer-to-peer solicitation. Journal of Public Economics 114: 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, Johana, and Juan Sobejano. 2011. Social Media IOR—Las Relaciones como Moneda de Rentabilidad. Madrid: Bubok Publishing S.L. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Jae Eun. 2017. Retweeting in health promotion: Analysis of tweets about Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Computers in Human Behavior 74: 112–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coordinadora de ONGD España. 2017. Resumen ejecutivo del informe web sobre las organizaciones de cooperación para el desarrollo. Available online: https://informe2017.coordinadoraongd.org/downloads/informe_del_sector_2017.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Dann, Stephen. 2010. Redefining social marketing with contemporary commercial marketing definitions. Journal of Business Research 63: 147–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Chuqing, and Hyejoon Rim. 2019. Exploring nonprofit-business partnerships on Twitter from a network perspective. Public Relations Review 45: 104–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, Jennifer Allyson, Sandra C. Jones, and Don Iverson. 2012. Web 2.0: An assessment of social marketing principles. Journal of Social Marketing 2: 207–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, Harmonie, and Y. Connie Yuan. 2011. Facebook to Increase Volunteerism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication Building 16: 115–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Miriam, Lara Piccolo, Harith Alani, Diana Maynard, Christop Meili, and Meia Wippoo. 2017. Pro-Environmental Campaigns via Social Media: Analysing Awareness and Behaviour Patterns. The Journal of Web Science 3: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, Rebecca, Cassandra J. Rowe, Shilpa N. Modi, and Dana Sievers. 2017. The effectiveness of social marketing in global health: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning 32: 110–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, Alexandre. 2014. Marketing digital en redes sociales: Lo imprescindible en Marketing. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=ibBEBAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=es#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Gálvez-Rodríguez, Maria D. M., Carmen Caba-Pérez, and Manuel López-Godoy. 2016. Drivers of Twitter as a strategic communication tool for non-profit organizations. Internet Research 26: 1052–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Torres, Elvira, Lyudmyla Yezers’ka, Alejandro Rost, Mabel Calderín, Concha Edo, Miladys Rojano, Elias Said, Pedro Jeronimo, Carlos Arcila, Ana Serrano, and et al. 2011. Uso de Twitter y Facebook por los medios iberoamericanos. El Profesional de La Información 20: 611–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gomes, Rita Ferreira, and Beatriz Casais. 2018. Feelings generated by threat appeals in social marketing: Text and emoji analysis of user reactions to anorexia nervosa campaigns in social media. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 15: 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunig, James, and Todd Hunt. 2000. Dirección de Relaciones Públicas. Barcelona: Gestión. [Google Scholar]

- Guidry, Jeanine P. D., Richard D. Waters, and Gregory D. Saxton. 2014. Moving social marketing beyond personal change to social change: Strategically using Twitter to mobilize supporters into vocal advocates. Journal of Social Marketing 4: 240–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Chao, and Gregory Saxton. 2014. Tweeting Social Change: How Social Media are Changing Nonprofit Advocacy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Chao, and Gregory Saxton. 2018. Speaking and Being Heard: How Nonprofit Advocacy Organizations Gain Attention on Social Media. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmig, Bernd, and Julia Thaler. 2010. On the Effectiveness of Social Marketing.What Do We Really Know? Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 22: 264–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmig, Bernd, Marc Jegers, and Irvine Lapsley. 2004. Challenges in Managing Nonprofit Organizations:A Research Overview. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations Voluntary and Nonprofit Organization 15: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, Teri, and Jeanine Guidry. 2004. Online communication in nonprofit organizations. Paper presented at the Sixteenth Annual Robert B. Clarke Direct/Interactive Marketing Educators’ Conference, New Orleans, LA, October 17. [Google Scholar]

- Hestres, Luis. 2014. Preaching to the choir: Internet-mediated advocacy, issue public mobilization, and climate change. New Media & Society 16: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hootsuite. 2018. Digital Report 2018. We are Social. Available online: https://www.juancmejia.comwp-content/uploads/2014/02/Estudio-de-estadísticas-de-Internet-y-Redes-Sociales-WeAreSocial-y-Hootsuite.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Hoover, Joe, Kate Johnson, Reihane Boghrati, Jesse Graham, and Morteza Dehghani. 2018. Moral Framing and Charitable Donation: Integrating Exploratory Social Media Analyses and Confirmatory Experimentation. Psychology 4: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAB Spain, and Elogia. 2018. VIII Estudio anual de las rede sociales 2018. Available online: https://iabspain.es/wp-content/uploads/estudio-redes-sociales-2018_vreducida.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Ihm, Jennifer. 2015. Network measures to evaluate stakeholder engagement with nonprofit organizations on social networking sites. Public Relations Review 41: 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, Amador, and Alessandra Farné. 2014. Herramientas de comunicación parra el tercer sector: El uso de las redes sociales por las ONGD catalanas. COMMONS—Revista de Comunicación y Ciudadanía Digital 3: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Sandra C., Kelly Andrews, and Kate Francis. 2017. Combining Social Norms and Social Marketing to Address Underage Drinking: Development and Process Evaluation of a Whole of Community Intervention. PLoS ONE 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, P. K, and Hongshuang Alice. 2017. Digital marketing: A framework, review and research agenda. International Journal of Research in Marketing 34: 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, Michael L., and Maureen Taylor. 2002. Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relations Review 28: 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite, James, Bridget C. Foley, Anne C. Grunseit, and Becky Freeman. 2016. Please Like Me: Facebook and Public Health Communication. PLoS ONE 11: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, Philip. 2011. Reinventing Marketing to Manage. Journal of Marketing 75: 132–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 1990. Metodología de análisis de contenido. Teoría y práctica. Barcelona: Paidós Comunicación. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Chih-hui, Bing She, and Chen-chao Tao. 2017. Computers in Human Behavior Connecting the dots: A longitudinal observation of relief organizations representational networks on social media. Computers in Human Behavior 74: 224–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, Carlos. 2010. Los medios interactivos y su publicidad. La medición de audiencias. Cuadernos de Comunicación e Innovación 82: 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, Réjean. 1998. L´analyse de contenu. Edited by B. Gauthier. Sillery: Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, Kristen, and Gregory D. Saxton. 2012. Information, Community, and Action: How Nonprofit Organizations Use Social Media. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17: 337–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Evie. 2017. Reinventing the rattling tin: How UK charities use Facebook in fundraising. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing 22: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucerga, Maria. 2013. Nuevas herramientas para viejos interrogantes. Contradicciones de la comunicación de las organizaciones de desarrollo en la era de la solidaridad digital. COMMONS—Revista de Comunicación y Ciudadanía Digital 2: 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macia, Fernando, and Javier Gosende. 2011. Marketing Con Redes Sociales. Madrid: Anaya. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, Rebeca. 2010. La comunicación web del tercer sector. Análisis estructural de los sitios web de las ONGD calificadas por la Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo. Ph.D. thesis, University of Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie-mohr, Doug, and P. Wesley Schultz. 2014. Choosing Effective Behavior Change Tools. Social Marketing Quarterly 20: 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, Marcus, Maureen Linke, and Asriel Eford. 2012. Shoveling Tweets: An Analysis of the Microblogging Engagement of Traditional News Organizations. International Symposium on Online Journalism 2: 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, Eva. 2015. Análisis comparativo de la utilización de twitter como canal de comunicación para las principales editoriales estadounidenses y españolas. Ph.D. thesis, University Autónoma of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Moonhee, Ying, and Brandon Boatwright. 2019. Hastags Activism.pdf. Public Relations Review 45: 10–23. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Isabel. 2015. El alcance mediático de los gabinetes de comunicació de las ongd pro inmigrantes. Análisis de la campaña ¿Y tú de quién eres? De la fundación Sevilla Acoge en 2013. Ph.D. thesis, University of Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Naik, Prasad A., and Kay Peters. 2009. A Hierarchical Marketing Communications Model of Online and Offline Media Synergies. Journal of Interactive Marketing 23: 288–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Erin. 2019. Come on feel the noise: The relationship between stakeholder engagement and viral messaging through an association’s Twitter use. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 16: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliński, Marian, and Piotr Szamrowski. 2019. The Use of the Twitter in Public Benefit Organisations in Poland: How Communicative Function of Tweets Translates Into Audience Reaction? Central European Economic Journal 5: 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, Joy, Rebekah Russell-Bennett, and Josephine Previte. 2018. Challenging the planned behavior approach in social marketing: Emotion and experience matter. European Journal of Marketing 52: 837–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, Ken, and Sue Peattie. 2009. Social marketing: A pathway to consumption reduction? Journal of Business Research 62: 260–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, Cristina M., Gisela Redondo, Teresa Sordé, and Ramon Flecha. 2018. Social impact in social media: A new method to evaluate the social impact of research. PLoS ONE 13: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PVE. 2016. Hechos y cifras del voluntariado en España 2015. Available online: http://www.fevocam.org/sites/default/files/pve_hechos_y_cifras_del_voluntariado.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Ramil, Xose. 2012. ¿Cuál es el nuevo paradigma de la comunicación en el que nos movemos las ONG de Desarrollo? pp. 16–25. Available online: https://coordinadoraongd.org/old/1024/original/20120620_140606_culturadigital.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Saiz, Vanesa, and Marina Mantini. 2012. Las emergencias ambientales en las redes sociales de las ONGD. Paper presented at III Congrés Internacional Associació Espanyola d’Investigació de La Comunicació, Tarragona, Spain, January 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Stephen G, and Dani J Barrington. 2015. Redefining social marketing: Beyond behavioural change. Journal of Social Marketing 5: 160–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, Gregory D., and Richard D. Waters. 2014. What do Stakeholders Like on Facebook? Examining Public Reactions to Nonprofit Organizations’ Informational, Promotional, and Community-Building Messages. Journal of Public Relations Research 26: 280–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, Sara, Krzyszto Kubacki, Timo Dietrich, and Scott Weaven. 2019. Using social media to create engagement: A social marketing review. Journal of Social Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Filipa, Teresa Proença, and Marisa R. Ferreira. 2018. Volunteers’ perspective on online volunteering—A qualitative approach. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing 15: 531–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboleva, Alena, Suzan Burton, Kate Daellenbach, Debra Z. Basil, Kate Daellenbach, and Debra Z. Basil. 2017. Tweets for tots: Using Twitter to promote a charity and its supporters. Journal of Consumer Marketing 34: 515–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, Ma del Mar. 2013. Métodos de sensibilización de las ONGD españolas: Una aproximación a través de la visión de las organizaciones de la COND. Revista F@ro 1: 92–103. [Google Scholar]

- Soria, Ma del Mar. 2014. El mensaje informativo en Facebook y Twitter en las ONGD: Un enfoque desde suspúblicos. Revista Internacional de Comunicación 27: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Soutter, Alistair R. B., and Simon Boag. 2019. Environmental advertising: The effect of imagery on pro-environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behaviour/Publicidad medioambiental: El efecto de las imágenes sobre las actitudes proambientales y el comportamiento proambiental. Psyecology: Revista Bilingüe de Psicología Ambiental/Bilingual Journal of Environmental Psychology 10: 88–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S. Shyam. 2008. The MAIN Model: A Heuristic Approach to Understanding Technology Effects on Credibility. In Digital Media, Youth, and Credibility. Edited by Miriam J. Metzger and Andrew J. Flanagin. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning; Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, Rosemary, Brad L. Neiger, and Heidi Keller. 2012. Integrating social media and social marketing: A four-step process. Health Promotion Practice 13: 165–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsur, Oren, and Ari Rappoport. 2012. What’s in a Hashtag?: Content Based Prediction of the Spread of Ideas in Microblogging Communities. Paper presented at WSDM ‘12: Proceedings of the Fifth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Seattle, WA, USA, February 8–12; pp. 643–52. Available online: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2124295.2124320%5Cnpapers3://publication/doi/10.1145/2124295.2124320 (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Veer, Ekant, Lucie Ozanne, and Michael Hall. 2015. Sharing cathartic stories online: The internet as a means of expression following a crisis event EKANT. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15: 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Elaine, Isabel Buil, and Leslie De Chernatony. 2017. When does “liking” a charity lead to donation behaviour? European Journal of Marketing 51: 2002–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrens, Matthijs J. 2011. Cohen’s kappa is a weighted average. Statistical Methodology 8: 473–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Hywel T. P., James R. McMurray, Tim Kurz, and F. Hugo Lambert. 2015. Network analysis reveals open forums and echo chambers in social media discussions of climate change. Global Environmental Change 32: 126–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, Walter. 2017. Social marketing strategy and industry involvement. Journal of Social Marketing 7: 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Mimi. 2010. Brands All a Twitter: The Influences of Twitter on Brands and Consumers. Ph.D. thesis, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Zollo, Lamberto, Maria Carmen, and Laudano Andrea. 2019. From governance to organizational effectiveness: The role of organizational identity and volunteers’ commitment. Journal of Management and Governance 23: 111–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value | Asymp. Std. Error a | Approx. T b | Approx. Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure of Agreement Kappa | 0.709 | 0.052 | 16.379 | 0.000 |

| N of Valid Cases | 100 |

| NGDO | Twitter Average Public Reaction | Facebook Average Public Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Cruz Roja Cadiz | 2524 | 3167 |

| Caritas Asidonina Jerez | 68,872 | 698 |

| Twitter-informative | Facebook-informative | |||

| NGDO | Messages published | Public average reaction | Messages published | Public average reaction |

| CRC | Information about organization (76.96%) | Information about social issues (29.96) | Information about organization (74.87%) | Information about organization (36.15) |

| CAJ | Information about social issues (77.25%) | Information about social issues (994.80) | Information about organization (72.35%) | Information about organization (8.70) |

| Twitter-dialogue | Facebook-dialogue | |||

| NGDO | Messages published | Public average reaction | Messages published | Public average reaction |

| CRC | Recognition (47.46%) | Recognition (43.48) | Recognition (43.15%) | Question (53.18) |

| CAJ | Recognition (44.44%) | Gratitude (36.80) | Recognition (96.52%) | Gratitude (16.00) |

| Twitter-behaviour | Facebook-behaviour | |||

| NGDO | Messages published | Public average reaction | Messages published | Public average reaction |

| CRC | Event (78.57%) | Colaboration (82.58) | Event (70.21%) | Event (23.36) |

| CAJ | Event (73.21%) | Colaboration (46.80) | Event (74.71%) | Event (11.48) |

| Twitter-theme | Facebook-theme | |||

| NGDO | Messages published | Public average reaction | Messages published | Public average reaction |

| CRC | Poverty and social exclusion (20.78%) | Emergencies (38.34) | Poverty and social exclusion (30.78%) | Prevention (44.09) |

| CAJ | Poverty and social exclusion (30.39%) | Religion or spiritual (3040.28) | Religion or spiritual (30.92%) | Emergencies (11.29) |

| Twitter-Quality | Facebook-Quality | |||

| NGDO | Messages published | Public average reaction | Messages published | Public average reaction |

| CRC | Text and photo (41.56%) No link (81.45%) One hashtag (43.04%) No mentions (84.87%) | Text and photo (29.71) Link (33.06) One hashtag (34.81) No mentions (29.60) | Text and photo (57.55%) No link (73.63%) No hashtag (73.47%) No mentions (99.36%) | Text and video (38.42) No link (34.99) 4 hashtags (45.00) No menions (31.76) |

| CAJ | Text (71.05%) No link (44.74%) No hashtag (66.18%) No mentions (84.87%) | Text (960.24) No link (1511.25) No hashtag (937.71) No mentions (805.58) | Text (43.73%) No link (49.65%) No hashtag (95.85%) No mentions (98.87%) | Video (39.00) No link (8.31) No hashtag (7.08) 2 mentions (20.00) |

| Correlations a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº hashtags | Public reaction | Nº mentions | ||

| Nº hashtags | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.047 | −0.116 ** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.119 | 0.000 | ||

| N | 1078 | 1078 | 1078 | |

| Public reaction | Pearson Correlation | −0.047 | 1 | −0.69 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.119 | 0.24 | ||

| N | 1708 | 1078 | 1078 | |

| Nº mentions | Pearson Correlation | −0.116 ** | −0.69 * | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.024 | ||

| N | 1078 | 1078 | 1078 |

| Correlations a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº hashtags | Public reaction | Nº mentions | ||

| Nº hashtags | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.003 | 0.054 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.936 | 0.175 | ||

| N | 622 | 622 | 622 | |

| Public reaction | Pearson Correlation | −0.003 | 1 | −0.021 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.936 | 0.609 | ||

| N | 622 | 622 | 622 | |

| Nº mentions | Pearson Correlation | 0.054 | −0.21 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.175 | 0.609 | ||

| N | 622 | 622 | 622 |

| Correlations a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº hashtags | Public reaction | Nº mentions | ||

| Nº hashtags | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.078 * | −0.115 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.32 | 0.002 | ||

| N | 760 | 760 | 760 | |

| Public reaction | Pearson Correlation | −0.78 * | 1 | −0.059 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.032 | 0.104 | ||

| N | 760 | 760 | 760 | |

| Nº mentions | Pearson Correlation | −0.115 ** | −0.059 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.104 | ||

| N | 760 | 760 | 760 |

| Correlations a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº hashtags | Public reaction | Nº mentions | ||

| Nº hashtags | Pearson Correlation | 1 | −0.039 | 0.70 * |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.182 | 0.002 | ||

| N | 1148 | 1148 | 760 | |

| Public reaction | Pearson Correlation | −0.039 | 1 | −0.059 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.182 | 0.104 | ||

| N | 1148 | 1148 | 760 | |

| Nº mentions | Pearson Correlation | −0.070 | 0.040 | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.018 | 0.176 | ||

| N | 1148 | 1148 | 760 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galiano-Coronil, A.; MierTerán-Franco, J.J. The Use of Social Digital Networks by NGDO from a Social Marketing Perspective. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060192

Galiano-Coronil A, MierTerán-Franco JJ. The Use of Social Digital Networks by NGDO from a Social Marketing Perspective. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(6):192. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060192

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaliano-Coronil, Araceli, and Juan José MierTerán-Franco. 2019. "The Use of Social Digital Networks by NGDO from a Social Marketing Perspective" Social Sciences 8, no. 6: 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060192

APA StyleGaliano-Coronil, A., & MierTerán-Franco, J. J. (2019). The Use of Social Digital Networks by NGDO from a Social Marketing Perspective. Social Sciences, 8(6), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060192