1. Introduction

Quality management is an evergreen research theme in the contemporary world (

Gunasekaran et al. 2019) and quality itself has been a top subject for years (

Ondra et al. 2018). The world is at the threshold of the fourth industrial revolution that has already begun. This is the fourth milestone which is fundamentally changing enterprises (

Mohelska and Sokolova 2018). Within a modern enterprise, change is a constant process that can be managed and predicted (

Sujova and Remen 2018). All sectors have to move toward Industry 4.0 (

Hamid et al. 2018). Although quality management became popular in the 1980s and 1990s, 21st-century enterprises in the era of Industry 4.0 are still struggling with the concept (

Gunasekaran et al. 2019). Industry 4.0 significantly changes products and production systems concerning design, processes, operations and services. Certainly, the implementation of this concept has further consequences for management and future jobs through the creation of new business models (

Moravcikova et al. 2017;

Meyer 2018;

Slusarczyk 2018) and in the cases when it is not appropriately managed, financial losses may occur (

Meyer et al. 2017). Since the primary impact of Industry 4.0 is perceived in value-creating processes, and has so far had the greatest transformative effect in this area, the model can be considered to be appropriate (

Nagy et al. 2018).

Industry 4.0 and its other synonyms such as Smart Manufacturing, Smart Production or the Internet of Things have been identified as major contributors in the context of the digital and automated manufacturing environment or projects aimed at the creation of zones of economic activity related to economic support and high level of economic efficiency (

Pierzyna 2019). The term Industry 4.0 comprises a variety of technologies to enable the development of the value chain resulting in reduced manufacturing lead times, as well as improved product quality and organisational performance (

Kamble et al. 2018).

Dalenogare et al. (

2018) consider Industry 4.0 a new industrial stage in which vertical and horizontal manufacturing process integration and product connectivity can help companies to achieve a higher level of industrial performance. Most studies discuss technical aspects, but do not pay attention to managerial approaches and organisational culture, which are a major factor influencing the success of this concept. It is especially interesting to find out whether, how and to what extent these knowledges are embedded into the business world and market (

Domańska 2018). Implementing the Industry 4.0 concept requires continuous innovation and education that not only depend on people’s abilities, but also on organisational culture (

Mohelska and Sokolova 2018).

Barney (

1986) indicates that organisational culture was a source of sustained competitive advantage for enterprises almost 35 years ago, and

Jancikova and Brychta (

2009) also consider organisational culture a significant factor in ensuring competitive advantage, an argument which is still highly relevant nowadays. Positive organisational culture is an essential principle of a successful enterprise.

Muras (

2017) emphasises that modern enterprises are constantly searching for an optimal enterprise infrastructure and culture, as well as changing their managerial approach to pave the way for innovative culture; quality culture is that innovative culture.

Wu et al. (

2011) reiterate that quality culture plays a critical role in organisational culture and appropriate quality makes management programs more effective. Industry 4.0 can be recognised as a great opportunity for the development and improvement of competitiveness, although the state of preparations for its implementation varies widely depending on country, sector, or even an individual company (

Slusarczyk 2018); developed quality culture can facilitate implementation of this concept. The key to success is to understand customer needs, and fulfill them with the highest quality, adapting at the same time to the expected changes in market demand (

Kovács and Kot 2017).

Definitions by authors that have been interested in quality culture vary quite widely. Quality culture encompasses organisational practices, central values and philosophy and can be defined as the concentration of all people and resources in a never-ending quest for greater quality and service in every dimension of the organisation (

Viljoen and van Waveren 2008). Quality culture is the pattern of habits, beliefs and behaviour concerning quality (

Watson and Gryna 2001;

Palus et al. 2014;

Popescu 2018). The quality culture of an organisation is a subset of the organisation’s overall culture. It reflects the general approach, the values, and the orientation to quality that permeate organisational actions (

Cameron and Sine 1999). Leadership emphasis, message credibility, peer involvement, and employee ownership are attributes which predict the corporate culture focused on quality (

Srinivasan and Kurey 2014).

Popescu et al. (

2018a) declare that even if sophisticated technologies of Industry 4.0 have been embraced, productivity growth is still moderate.

Georgescu et al. (

2018) explain that adopting the overall quality system is a profound transformation involving changes at all levels of the enterprise, starting with the management system as a whole, continuing with the change in attitudes and behaviours among the employees of the enterprise.

Goetsch and Davis (

2013) consider the ultimate, anticipative result of endeavour in the quality culture, the environment of continuous improvement of quality in all areas of the enterprise.

Fielden et al. (

2018) mention that news stories that are rapidly shared through social media can generate important advertising returns. In our case, in the quality culture, news stories about continuous improvement of the quality shared through employees can generate the most important advertisement of the enterprise.

Popescu et al. (

2018b) point out that underperforming individuals confront a deep supervisory exigency, but

Kuo and Tsai (

2019) demonstrate—from the perspective of employees—that this innovative culture also has a positive effect on performance and underperformance and the supervisory exigency has disappeared. The positive influence on operational performance is confirmed by the empirical study of

Gambi et al. (

2015). The study by

Hebbar and Mathew (

2017) interprets the significance in harnessing the quality culture of the enterprise to enhance the overall quality of performance.

Abakumova and Primierova (

2018) and

Ahmad et al. (

2018) support the importance of the quality culture of the enterprise and its consequence of quality performance because, as a rule, households with a high level of earnings prefer high-quality and exclusive goods.

Numerous studies can be found which focus on bankruptcy prediction in Slovakia (

Kovacova et al. 2018), Slovak research on identifying significant sources of enterprise goodwill (

Kliestik et al. 2018a), or using controlling as a competitiveness tool on the Slovak market (

Vagner 2016), but detection of the existence and the development of quality cultures in the context of Industry 4.0 is still lacking. It is necessary to examine these facts, as

Kanovska (

2018) notes that smart manufacturing is still developing and taking place in different forms.

Krajcsak (

2018) finds ISO standards and Total Quality Management (TQM) only appropriate organisational cultures, not quality culture; this is another scientific gap when it comes to determining a representative culture quality for traditional quality concepts. Those are sectoral standards, ISO standards and TQM philosophy (

Konecny 2017). Classical quality-orientated managements change, learn and adapt to innovation brought about by Industry 4.0 (

Bourke and Roper 2017).

Given the deliberations presented, the aim of this paper is to analyse the typical dependence between quality cultures and quality concepts and to detect the factors that differentiate individual quality cultures in Slovakia. Our paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we present the literature review, concentrating on analyses of different aspects associated with quality culture in contemporary enterprises. Secondly, we present the materials and methods that were applied in this research. The appropriately methods of mathematical statistics are used and described to fulfil the aim. These methods were run: Person chi-square test, Cramer’s V and Pearson contingency coefficient, correspondence analysis, test of a proportion, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of adequacy, Bartlett’s test of sphericity, Varimax with Kaiser normalisation, Cronbach’s alpha, the test of Box’s M, Wilks’ Lambda test, and discriminant analysis. The next part of our paper presents the research results and analyses the results in detail. We use data from our own survey. It was made purposive sample of 2909 “respondents”, it must be manufacturing enterprises, which implementing at one quality management system. The enterprises were addressed electronically by emails and was required to fill the survey by quality managers, technical managers or supervisors. Based on provided data medium dependence between the quality concepts and the quality cultures is indicated, typical relations between individual quality concepts and individual quality cultures are characterised, and three significant factors (the improvement and assurance of quality, the use of information and the overall effectiveness) are detected that differentiate individual quality cultures in Slovakia. Finally, we present the conclusions and limitations of our study.

Literature Review

The topic of quality culture is a matter of interest for a number of scholars representing a variety of scientific institutions who have analysed it from different points of view. For example,

Sinclair and Collins (

1994) discuss the quality culture, whilst

Dellana and Hauser (

1999) went even further in carrying out a study defining the quality culture.

Woods (

1997) detects six values of quality culture and

Harvey and Stensaker (

2007) link understandings and the boundaries of the quality culture.

Tari et al. (

2018) highlight that the quality culture can motivate the enterprise to adopt quality standards (sectoral standard and ISO standards).

Gaigne and Larue (

2016) study the impact that minimum quality standards have on industry structure, trade, and welfare when firms can develop their own private standard which is of a higher quality than the public standard.

Vanagas (

2005) evaluates the role of quality culture in the implementation of total quality management in agricultural companies.

Panuwatwanich and Nguyen (

2017) deal with the evidence from the Vietnamese construction industry considering the influence of culture on the implementation of TQM philosophy. The tangibility of quality culture is described by

Porter (

1997).

Campos et al. (

2014) test total quality culture in the enterprises of two subsectors of the tourism industry and show that leadership is a critical success factor for total quality culture, mainly if the manager is directly involved in quality, behaves unambiguously, and leads and motivates cultural changes. In addition,

Meyer and Meyer (

2016) found that leadership also contributes to the creation of enabling business environment in general. Industry 4.0 implementation for multinationals was the goal of the work of

Telukdarie et al. (

2018). Previous research into diagnosing and changing culture was undertaken by

Handfield and Ghosh (

1994);

Cameron and Barnett (

2000);

Lo (

2002);

Cao et al. (

2005);

Kull and Wacker (

2010);

Baird et al. (

2011). Changing and learning in enterprises oriented to quality in the era of Industry 4.0 is highlighted in the study by

Bourke and Roper (

2017).

Iqbal and Asrar-ul-Haq (

2018) examine the relationship between TQM practices and employee performance in the dynamic technological sector in Pakistan.

Amin et al. (

2017) show that TQM constructs have significant relationships to employee satisfaction. A new TQM model in the environment of innovation is delivered by

Shan et al. (

2018a,

2018b). The relationship between TQM and quality culture has been examined by

Hildebrandt (

1991);

Hauser and Dellana (

1998);

Kujala and Lillrank (

2004);

Prajogo and McDermott (

2005);

Wu et al. (

2009);

Gimenez-Espin et al. (

2013);

Todorut and Bojnica (

2013); and

Pakurár et al. (

2019).

Hebbar and Mathew (

2017) identify the critical TQM practices or factors and the impact of the quality culture on these practices and quality of performance in automotive enterprises in India. The results obtained support the significant positive relationship between quality culture and all critical factors. TQM practices have a positively significant relationship to quality culture, which plays a major role in boosting the quality of performance in the enterprise (

Androniceanu 2017). Another study from India carried out by

Patyal and Koilakuntla (

2017) explores the relationship between quality management and performance, specifically how the infrastructure and core quality management practices affect quality and business performance.

Garvin (

1988) points out that quality cultures have developed over time in enterprises. He labels four major quality cultures: inspection culture, statistical control culture, quality assurance culture and strategic quality management culture.

Cole (

1999) identifies two main quality cultures that typify manufacturing enterprises: a new quality paradigm and an old quality paradigm.

Cameron and Sine (

1999) and

Cameron and Quinn (

1999) made a comprehensive classification of quality culture (QC) and divided QC into levels depending on their development: the absence of emphasis on quality (QC1), error detection culture (QC2), error prevention culture (QC3) and creative quality culture (QC4). Based on this proposed classification,

Gimenez-Espin et al. (

2013) introduce an alternative type of culture: the mixed culture or culture for quality, which can be between adhocratic and clan cultures. It can have a double orientation—external and internal—and can promote flexibility. The culture of operational excellence through Industry 4.0 is monitored by

Quezada et al. (

2017).

Shan et al. (

2018a,

2018b) develop a model of a prominent paradigm to improve manufacturing performance in order to gain further competitive advantage.

Empirical evidence of the impact of quality culture on quality or operational performance was provided by

Adam et al. (

1994) in Korea, New Zealand and the USA,

Kanji and Wong (

1998) in the construction industry,

Ogbonna and Harris (

2000) in UK enterprises,

Barrett and Waddell (

2001a,

2001b) in Australia, and

Corbett and Rastrick (

2000) in New Zealand.

Watson and Gryna (

2001) analyse the quality culture in small businesses.

Wu (

2015) empirically assesses the path from quality culture to infrastructure practices, core practices, and finally to quality performance using data collected from Chinese manufacturing enterprises in a structural equitation model. The results indicate a chain effect that quality culture serves as an antecedent of infrastructure practices to take effect and infrastructure practices providing a supporting foundation for core practices to generate a positive impact on quality performance.

Ilies et al. (

2015), based on evidence from metal construction industry organisations from northwestern Romania, develop regression models explaining and making predictions about the variation of variables which synthesise the quality culture. Another study from the Romanian metal construction industry, undertaken by

Ilies et al. (

2017), obtains a surprising result concerning the leadership style favourable to the development of the quality culture. The managers from the organisations analysed, who have an authoritarian leadership style, favour the development of the quality culture more than managers who adopt a democratic style. It is worth to add that a part of the organisational culture is also the intergenerational collaboration of employees. As the majority of developed countries faces changing transition towards older population structure, it has to be reflected also in organisations and the organisational culture (

Kubíčková et al. 2018).

Cronemyr et al. (

2017) indicate the need for a tool that measures not only the quality values but also behaviour that supports or obstructs the quality culture. They suggest how a measuring tool which measures quality culture can be designed and structured in Swedish conditions.

Ko and Stein (

2019) propose two methodologies to catalyse and sustain continuous improvement within an enterprise to adopt a positive quality culture. Key factors of manufacturing enterprise development in the context of Industry 4.0 in Russia are assessed by

Tolstykh et al. (

2018).

A systematic literature review identifying the current trends and future perspectives of Industry 4.0 is undertaken by

Kamble et al. (

2018).

Ghobakhloo (

2018) provides a strategic roadmap for the future of the manufacturing industry toward Industry 4.0.

Gunasekaran et al. (

2019) present a research pathway towards Industry 4.0 for quality management in 21

st-century enterprises. Mohelska and Sokolova describe management approaches for Industry 4.0 from an organisational culture perspective in the Czech Republic.

Sujova and Remen (

2018) evaluate the management of changes in business processes affected by Industry 4.0 in Slovak conditions. A review of service-oriented manufacturing paradigms is carried out by

Siderska and Jadaan (

2018).

Luthra and Mangla (

2018) as well as

Ohanyan and Androniceanu (

2017) comprehensively evaluate the challenges of Industry 4.0 in emerging economies.

Oliff and Liu (

2017) integrate methods of Industry 4.0 with emerging paradigms of existing manufacturing processes to quality improvement. The use of ISO standards in Big Data analytics cloud services is analysed by

Roy et al. (

2017).

Slusarczyk (

2018) inspects the attitudes to and preparation of entrepreneurs for Industry 4.0. The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance is discussed by

Dalenogare et al. (

2018).

2. Materials and Methods

A detailed analysis of the literature allows us to formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. A significant dependence exists between quality culture and quality concept.

Hypothesis 2. Error detection culture is implemented in more than 50% of enterprises with sectoral standards.

Hypothesis 3. Error prevention culture is implemented in more than 50% of enterprises with ISO standards.

Hypothesis 4. Creative quality culture is implemented in more than 50% of enterprises with TQM.

Hypothesis 5. A significant discriminant function exists in differentiating quality cultures.

All details regarding the materials and methodology are as follows:

1. The information (primary source) used in this article was gained from the survey undertaken by the authors. The content and the trend of the questions were taken from the American research carried out by

Cameron and Sine (

1999) and modified to Slovak conditions because of the subsequent possibility of comparing the results. The survey was carried out in 2018 to detect the level of the development of a quality culture in Slovak manufacturing enterprises. The decision was made to provide non-probability sampling (purposive sampling). Two required conditions must be met by the enterprises: it had to be a manufacturing enterprise and at least one of the quality management systems had to be implemented in the enterprise.

2. After determining the attributes of the purposive sampling of the enterprises, the sample size is determined, meaning the number of responses from each quality culture. The decision was made to connect two recommendations.

Saunders et al. (

2012) state in their book that sample size determination is specific for each case and must reflect a number of factors. They specify minimum sample sizes for different study characters, specifically 12 to 30 responses for heterogeneous samples.

Singh and Masuku (

2014), quoting

Sudman (

1976), suggest that each minor group of the sample should necessarily contain 20 to 50 elements.

3. There is no database in Slovakia that would meet the conditions demanded; because of this, the researchers compiled their own database based on data from the Slovak Society for Quality, the Slovak Office of Standards, Metrology and Testing, participants of the National Quality Award of the SR, the Slovak National Accreditation Service and Certification companies. The final database created by authors consists of 2909 enterprises. 2909 questionnaires were sent electronically, and the number of correctly recorded responses in the given time was 126, representing the completion of approximately every 23rd questionnaire and a return rate of 4.33%.

4. The survey determined the level of the development of quality culture and implemented the quality concept. Cross-tabulation of quality culture and quality concept was undertaken to identify the possibility of the use of the Person chi-square test and to test the dependence between nominal variables. The assumption of 20% of cells having less than five expected (theoretical) observations is satisfied. The strength of dependence and its statistical significance were tested by Cramer’s V and Pearson contingency coefficient according to

Rezankova (

2017).

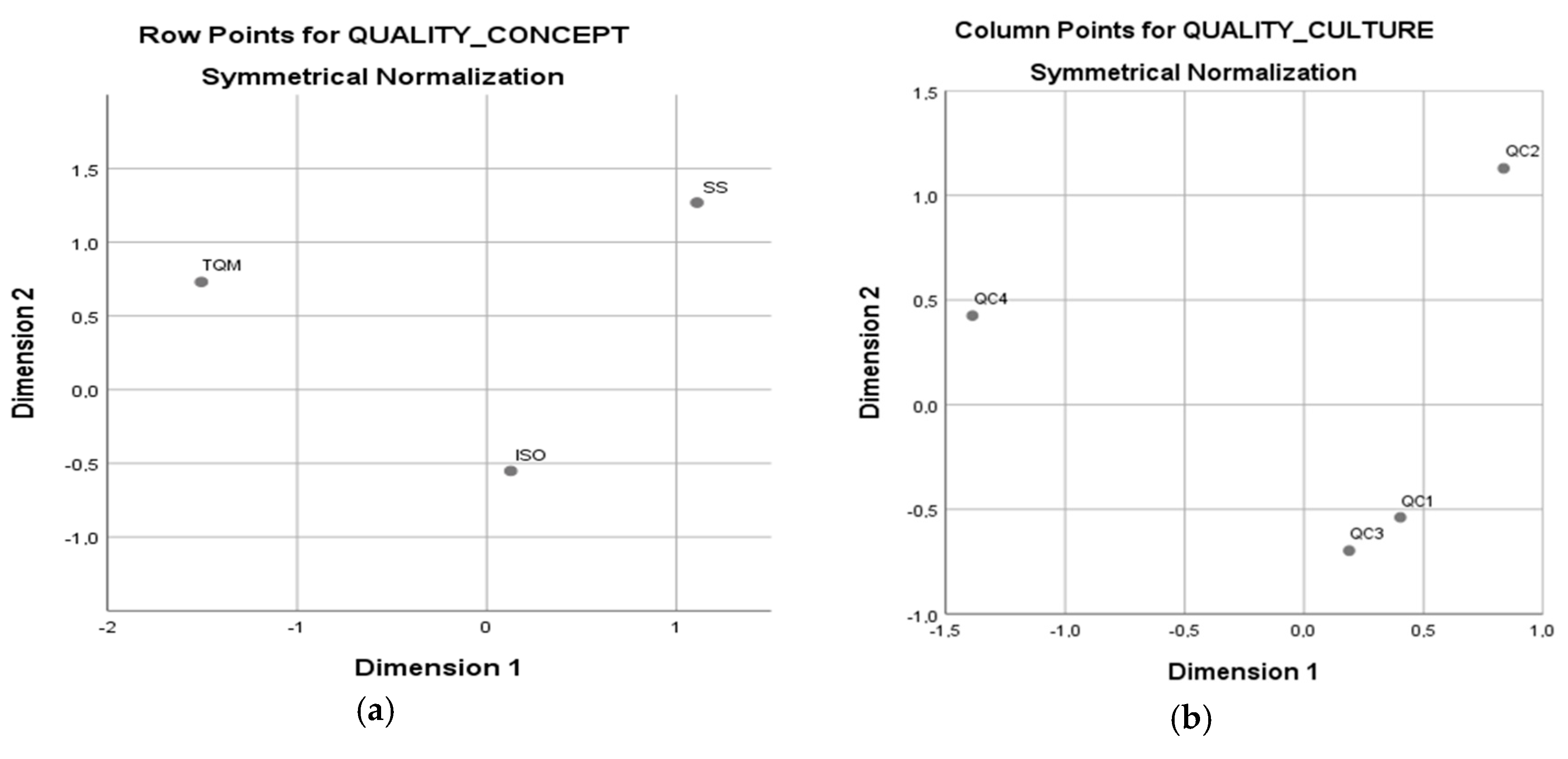

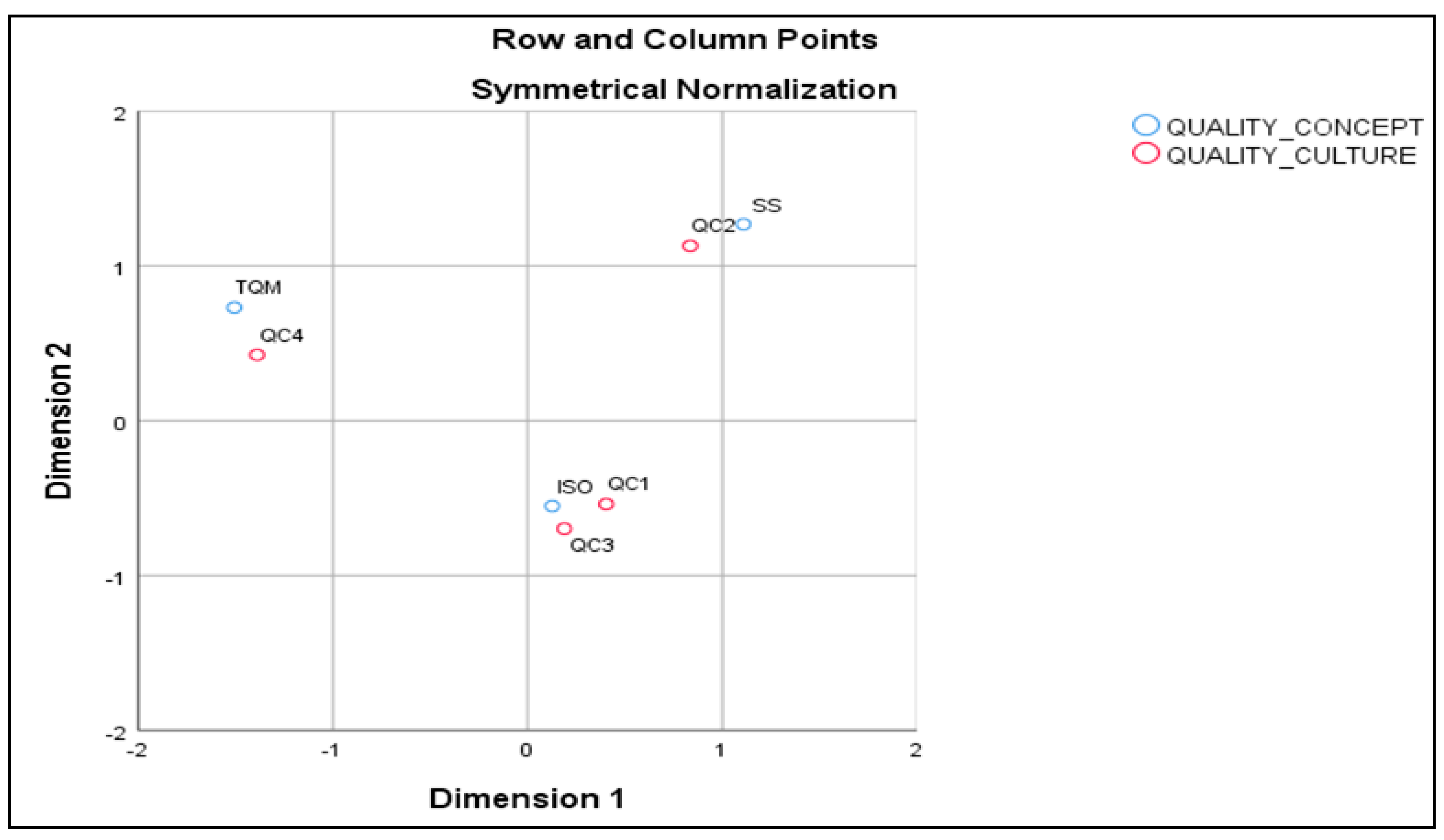

5. Subsequently, the authors undertook the correspondence analysis with an overview and correspondence map of row points, an overview and correspondence map of column points, and a correspondence map of row and column points as well, in order to detect the relationship between categories of quality culture and the quality concept. Correspondence analysis is a method used to detect groups of similar categories. Its main advantage is the ability to analyse the relationship between the categories of two variables at the same time (

Rezankova 2017). Correspondence analysis examines the internal structure by means of correspondence maps showing variable categories in a reduced two-dimensional coordinate system.

Kral et al. (

2009) discuss the fact that row and column points can be considered as coordinates of the point in r(s)—dimensional space, and from the viewpoint of the practical application, their visual representation uses two-dimensional correspondence maps.

6. The hypothesis is determined to identify the relations between categories of variables. To test the hypothesis, a test of a proportion is used, where test statistics

T (Equation (2)) to the critical value of standard normal distribution are compared. There are two approaches to verify the range of the test (due to the approximation of the normal distribution) and none of them has a significant preference. Thus, the validity of both approaches is verified (Equations (3) and (4)).

7. The survey contained 97 questions measured by a 6-point Likert scale, where point 1 corresponds to ‘strongly disagree’ and 6 ‘strongly agree’. Questions were labelled from Q18 to Q114. All questions have the same positive coding. The set of questions is reduced to 8 heterogeneous components (factors, variables) by factor analysis, and it assessed percentages of total variance explained not the criterion of convergence of eigenvalue to the value 1. The adequacy of the use of factor analysis is checked by the KMO measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The extraction method is a principal component analysis, the rotation method is Varimax with Kaiser normalisation and rotation converged in 10 iterations. The reliability of the factors is tested by Cronbach’s alpha. The values of internal consistence of factors are made both with and without outliers and for divided parts of the sample, by the Pareto principle (80:20).

8. The use of canonical discriminant analysis is conditional on fulfilling some assumptions. It is necessary to check assumptions concerning independent variables (created by factor analysis) and the dependent variable (detected quality culture). All observations are assumed to be independent and have identical distribution (

Sadaf et al. 2018). Factor analysis prevents the occurrence of multicollinearity between dependent variables. The assumption of the multivariate normal distribution is not met, but the discriminant analysis is quite robust in order to break this assumption. The outliers, identified by box-plots, have to be removed. The equality of covariance matrices of individual groups retained in the test of Box’s M and the equality among groups of the independent variables is rejected by Wilks’ Lambda test.

9. The sample is divided 80%/20%; data is stratified and divided according to the individual group based on

Kral et al. (

2009). The larger part of the sample is used to construct the model, and the smaller part to validate the model. A significant canonical discriminant function was created in the discriminant analysis; this function was run by means of the stepwise method in three steps. The stepwise method of the discriminant analysis was applied to find the linear combination of those variables that best discriminate the groups of cases (

Kliestik et al. 2018b). Three significant factors were identified; the value of intercept and the equation of the model were also written.

10. The final model (Z-score) differentiates individual quality cultures in Slovak manufacturing enterprises; the selection of the enterprise to individual quality culture is based on a comparison of counted scores to centroids.

11. The validation of the model formed was carried out on the origin sample, from which the model was created, cross-validation and test sample.

IBM SPSS Statistics v. 25 software was used, rented from Kivuto Solutions Inc., Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland.

4. Discussion

Firstly, we compare our results to previous research undertaken by

Cameron and Sine (

1999) and

Jancikova (

2008) because the same questions were used in the survey. The levels of the quality culture are differentiated by the approach to the use of the information about the expectations and the satisfaction of the customer, the quality of the product and the production quality, the cost items, the reasons for success or its shortcomings. This content is captured as the use of information and proved to be significant in both Slovak and American research (

Table 19). More developed quality cultures focus on quality as a strategic advantage, engaging employees and giving them greater powers. Quality teams are founded, and enterprises focus on improvement and the assurance of quality. They come with quality-improving reports, and stories of the improvement are shared within the enterprise. Quality has its own plans, management and goals. This description of these activities is involved in a variable called improvement and the assurance of quality. It is a statistically significant factor in all analysed research. The last significant factor in our discriminant function is the overall effectiveness of the enterprise, which is identical to the content of the excellence used in Czech research (

Table 19). This factor is characterised by its orientation to high quality, which gains a new definition. Organisational culture and the strategy of the enterprise are no longer separate. The preferences of the customers are created through the provision of the services beyond their expectations. New loyalty of the employees is thereby created. The work of the employees is consistent, production is characterised by minimal repairs and reworking of the products, and work absenteeism is also minimal. There is a high degree of teamwork within the department as well as in cooperation between the departments. As indicated by the label and the content of the variable in Czech research, this factor is aimed at achieving excellence and world-class quality. Comparing the significant discriminant variables, we have two common variables in the case of the identified American function as well as in the case of the determined Czech function. Slovak enterprises should pay attention to the significant factors detected to ease their effort to absorb and adopt the principles of Industry 4.0.

All three functions have the same position of the centroids for the individual quality culture. Comparing our research and that of

Cameron and Sine (

1999) and

Jancikova (

2008), there is a clear intersection in

Table 20. The centroid positions of the two less developed quality cultures are found in the negative part, while the opposite position of the centroids of the two more advanced cultures are oriented in the positive part.

Srinivasan and Kurey (

2014) support the connection between quality culture and Industry 4.0 and their study confirms that an excellent quality environment can be created through a true culture where every employee has a passion to imbue rather than simply follow mundane rule-based techniques, such as quality control tools or imitation of best procedures and practices.

Mohelska and Sokolova (

2018) also do not focus on technical aspects, but rather managerial approaches for Industry 4.0. According to their findings, Czech respondents perceive the organisational culture in the organisations under review as more bureaucratic and supportive than innovative. In their view, the signs of innovative culture are not so striking. It is necessary to change managerial approaches to support innovative solutions. Quality culture is one of the possible innovative solutions.

A limitation of our research is that we focus on only creating positive quality culture, but other authors discuss further possible solutions for manufacturing enterprises to prepare for Industry 4.0.

Ghobakhloo (

2018) discusses the fact that manufacturers who are transitioning into Industry 4.0 need to devise new marketing strategies, and the assessment of their level of digital market maturity is the first step for this purpose, and describes modern marketing strategies such as market sensing and learning strategy as well as data-driven marketing, which is coupled with blockchain-based platforms and smart contracts.

Wu (

2015) emphasis that an IT governance team should perform a detailed analysis of existing IT infrastructure (e.g., networks, computer hardware and software, sensors, controllers and actuators) and identify the most meaningful approach for using them in support of Industry 4.0 transition.

Hamid et al. (

2018) highlight the effective application of a reinvestment allowance that was designed to support Industry 4.0.

Tolstykh et al. (

2018) suggest the creation of a laboratory which will allow manufacturing enterprises to carry out analysis, assessment and engineering of existing processes from the perspective of digitalisation, performance, project orientation and efficiency.

Telukdarie et al. (

2018) propose global standardisation and inter-functional integration. They deal with a global system approach, as defined by Industry 4.0 (vertical, horizontal and total business integration).

We consider the following areas as potential directions for further progress on this topic:

An extension of the areas of interest to the service enterprises and public organisations.

An extension of the areas of interest to businesses that have not implemented a certain quality management system.

Characterisation of a comprehensive framework of the quality culture in the era of Industry 4.0 through active cooperation with the business sphere.