Abstract

Masculinist contours have legitimized male domination in Indonesia’s upper public service ranks. However, some women have managed to crack the glass ceiling. A systematic search was undertaken of seven academic databases and the Google Scholar search engine to identify facilitative features of women’s career advancement through Indonesia’s echelon ranks. Fourteen articles, representing nine studies, were identified. While policy initiatives exist to increase women’s representation and career advancement, studies consistently identified little application to practice. Patterns across the studies located women’s career advancement as an individual concern and showed that women wanting careers were expected to manage the double burden of productive and reproductive life, obtain permissions from husbands and extended family, and adopt masculine leadership traits to garner colleagues’ support. Barriers frequently outweigh opportunities for career advancement; these including entrenched homo-sociability asserting that men make better leaders. Consequently, the blocking of women’s opportunities invoked personal disappointments, resulting in women’s public denial of their leadership ambitions.

1. Introduction

More than 4.5 million people are employed in Indonesia’s public service, which represents approximately 1.7 percent of the population (World Bank 2018). Indonesia’s public service has long been intertwined with the country’s political history in which men have traditionally dominated (Vickers 2013). For example, Suharto’s New Order-era (1967–1998) favored a masculinist-authoritarian leadership style that biased the appointment of men into strategic senior public service positions (Tidey 2018). ‘Fathering’ Indonesia during these times relied on a heavily centralized government system, one that rewarded loyalty and was premised on ensuring regime stability and economic growth (Vatikiotis 2013; McLeod 2008). According to Tidey (2018), public service appointments to senior positions during the Suharto regime were predominantly based on favoritism towards men with political and family connections to power and who were loyal allies in corruption, as opposed to merit.

It is more than two decades since Suharto’s demise. Political transitions, from authoritarianism to democracy, and decentralization’s downwards rescaling of power have been accompanied by large-scale reassignment of public servants from a centralized government to sub-national and local public administrative units (provincial, municipal, district, and sub-district/village) (Aspinall 2010; Manurung 2017; Ito 2011; Widianingsih et al. 2018; Widianingsih and Morrell 2007). Accompanying decentralization, Law No. 43/1999 proclaimed a merit-based human resource approach for employing and promoting public servants. This represents a positive move towards favoring the most qualified and relevantly experienced candidates for public service jobs irrespective of gender or other variables. While this marked significant progress towards adopting a meritocratic human resource system, the masculinist contours of Suharto’s New-Order-era still appear to dominate Indonesia’s public service (Vatikiotis 2013). Women continue to experience barriers in their public service careers and promotional advancements.

Women in Indonesia’s Public Service Echelons

In terms of career opportunities and promotion, mapping of the public service indicates only minor improvements for women since the Suharto era. The World Bank (2018) found considerable variations in gender balance across Indonesia’s national and sub-national governments. While the number of women public servants in some locations are reported to be higher than men (i.e., Government of Ambon City: 70%; Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection: 60%; National Library of the Republic of Indonesia: 52%), Indonesia’s public service is largely dominated by men. Most national and sub-national governments employ comparatively few women (i.e., Ministry of Law and Human Rights: 26%; State-Owned Enterprise: 24%; Secretariat General of Corruption Eradication Commission: 16%; Government of Pegunungan Arfak Subdistrict: 9%). Some employ no women at all (i.e., Regional-Owned Enterprise: 0%, Secretariat General of Commission for the Supervision of Business Competition: 0%) (World Bank 2018). Gender equity is more readily found in functional public service positions; these are positions with no staff to supervise and with no management responsibility. There are substantially fewer women in structural public service positions; these are the echelon ranks that have management or leadership responsibilities (World Bank 2018).

Structural positions consist of five echelon ranks, with Echelon 1 the highest and Echelon 5 the lowest. Most public service positions have no echelon rank, as they have no management or leadership responsibilities (i.e., teachers, healthcare, or social workers). Echelon positions represent approximately 5.8 percent (n = 253,679) of all of Indonesia’s public service; 75 percent (n = 191,849) of echelon positions are ranked Echelon 4 and Echelon 5 (World Bank 2018). These lowest two echelon ranks are tasked with supervisory responsibilities and are considered to be echelon subordinates (Sartika et al. 2018). Approximately 21 percent (n = 52,146) of echelon ranks are Echelon 3 (World Bank 2018). The responsibility of an Echelon 3 could be considered equivalent to a manager of a private company requiring technical knowledge relevant to a given directorate (Sartika et al. 2018). Echelon 2 represents less than 4 percent (n = 9398) of the echelon ranks (World Bank 2018) and has full authority to command entire ministries or government departments. The highest rank of Echelon 1 (0.1 percent, n = 286; World Bank 2018) is an elite position with overall power in any government office in Indonesia. It operates as a political conduit between a portfolio Minister and the Echelon 2s of the relevant directorate. While the structure of some countries’ public service systems appear to be evolving from hierarchy to heterarchy (O’Leary 2015; Shahan and Khair 2018), pyramid shaped bureaucracies such as Indonesia’s have universally remained the most popular model for most of the last century (Park 2019; Bailey 2018).

According to the World Bank (2018), over 70 percent of Indonesia’s national government echelon positions (consistent across Echelon 1 to Echelon 5) are occupied by men. The proportion of men across sub-national echelon ranks range from 58 percent (Echelon 5) to 90 percent (Echelon 1) (World Bank 2018). The disparity of women in Indonesia’s public service upper echelons is not a unique phenomenon. Research internationally evidences the ‘glass door’ phenomena in which women’s careers are inhibited as early as the recruitment phases where getting on career-track is inequitable in the first place (Picardi 2019). Other researchers critique the effect of social barriers and institutional blockages that impede women’s movement to the upper management echelons, known as the ‘glass ceiling’ (Azmi et al. 2012; Forster 1999; Jalalzai 2008; Yukongdi and Benson 2005; Coleman 2010; O’Neil and Hopkins 2015; Newman 2016; Curtin 2019; De Simone et al. 2018). Men are reported to enjoy notable advantage in career advancement across the public service and its private sector counterparts (Ensour et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2017; Chappell and Waylen 2013). Furthermore, when women are promoted to senior leadership, authors highlight the benevolent sexism that exists. The ‘glass cliff’ phenomena is frequently used to explain how women are set up to fail—they experience shorter than average tenures, thereby receiving less opportunity than men to prove their leadership capability (Cook and Glass 2014; Jenter and Kanaan 2015), women are more likely to be promoted to precarious positions in poorly performing organizations (Ryan et al. 2016; Elsaid and Ursel 2018; Bruckmüller et al. 2014; Acar and Sümer 2018), and women are terminated more frequently when they subsequently follow someone else’s bad leadership (Kulich et al. 2015) than men.

Research by The World Bank (2018) confirms the phenomena of the ‘glass ceiling’ and the ‘glass cliff’ in Indonesia’s public service. While the presence of women in the upper echelons is growing, there does not appear to be any gender symmetry in the highest of echelons. Few women are of echelon rank one and two. The importance for Indonesia of addressing the disparity in women’s participation in senior public service leadership is articulated in the public policy and public administration literature. For example, research consistently associates higher numbers of women in politics and the public service with lower corruption rates and better quality leadership (Goetz 2007; Dollar et al. 2001; Esarey and Chirillo 2013; Swamy et al. 2001; Besley et al. 2017; Omar and Ogenyi 2004; Coleman 2010). It is not clear whether women are less corrupt, if nurturing roles lean women towards altruism and good governance, or whether less opportunities for corruption exist for women in comparison to men (Zhao and Xu 2015; Sung 2012; Swamy et al. 2001; Esarey and Chirillo 2013; Michailova and Melnykovska 2009; Alhassan-Alolo 2007). Regardless of causation, increasing women’s participation in public sector leadership is generally associated with good governance, effective leadership, integrity, more equitable societies, and strengthened economies (Cosgrove and Lee 2016; Haack 2014; Kymlicka and Rubio-Marin 2018; Goetz 2018; Markham 2013; Dollar et al. 2001; Swamy et al. 2001; Eckel and Grossman 1998). Gender quotas for women’s parliamentary representation of 30% have been in place since Indonesia’s 2004 electoral cycle (Hillman 2018); however, there are currently no gender quotas for Indonesia’s public service (World Bank 2018).

The authors of the current paper commenced a participatory research project with Echelon 2 ranked women public servants from West Java early in 2018. Preparatory work involved high-level, international dialogues between women from different countries to devise a strategic plan for research, program development, and the implementation of solutions. The first stage of this project is a systematic search and rapid review of published academic research studies. This is to be followed by original research with Indonesian women public servants in echelon ranked positions and together inform the design and delivery of an Indonesian career mentoring program to be piloted with women public servants.

2. Methods

Accordingly, the objective of the current rapid review is to document the current state of knowledge about the mobilizing features of women’s successful career advancement through the Indonesian public service echelon ranks. This will enable the following questions to be addressed:

- What is known about women’s career advancement to the upper echelon ranks of Indonesia’s public service?

- What are the strategies of Indonesian women who have succeeded with career advancement to the upper echelons?

- What interventions have been trialed, found effective, and/or ineffective for increasing Indonesian women’s promotional opportunities and representation in the upper echelons?

2.1. Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

A systematic search of academic journal articles was conducted in December 2018. Databases searched were Informit, ProQuest, Scopus, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, Web of Science, and PsycInfo, as well as the first 20 pages of results from the Google Scholar search engine. Search terms were: Indonesia AND women OR female OR gender OR glass AND echelon OR executive OR leader OR (manager OR management) OR “structural position” AND government OR “public management” OR “public sector” OR (“public administration” OR “public administrator”) OR (“public service” OR “public servant”) OR (“civil service OR “civil servant”).

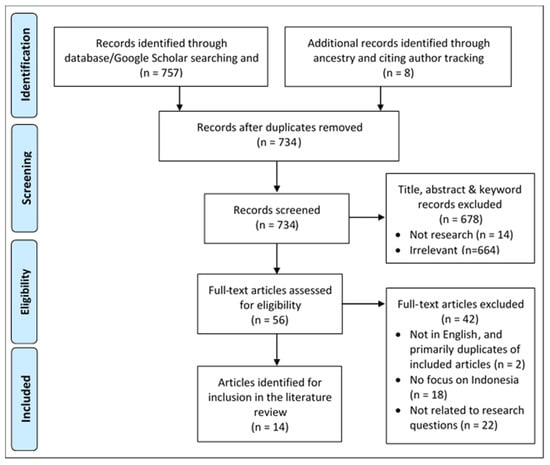

The database search produced 757 items (see Figure 1). Eight additional items were identified from other sources (ancestry searching of reference lists and Google Scholar progression tracking of citing authors). Thirty duplicates were removed. Titles, abstracts, and keywords of the remaining 734 articles were screened for potential eligibility. Fifty-six articles were deemed potentially relevant as they made mention of women and Indonesia’s public service (including management of State enterprise and civil service academic positions in government universities). To ensure all possible relevant articles were included, there were no year of publication restrictions.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search and inclusion strategy.

Fifty-six articles were subjected to full-text review, resulting in fourteen articles, representing 11 research studies, that met the inclusion criteria. To be included in the present review, articles were required to meet the following criteria: (1) women’s career advancement in the public service in Indonesia; (2) promotional opportunity or strategies of women in Indonesia to advance their public service careers; or, (3) interventions aimed to increase women’s representation in the public service or promotional opportunities. Only six discrete studies, reported across 11 articles, met the inclusion criteria. The criteria were subsequently expanded to include other relevant studies, namely: (4) glass ceiling phenomena in Indonesia. A further three articles, representing three discrete studies, were located. The primary interest was of the mobilizing features of women’s career advancement in Indonesia. Articles on the barriers in women’s career trajectories were included because they provided insights into the challenges that Indonesian women have succeeded in overcoming.

2.2. Quality Appraisals

The STROBE statement (Von Elm et al. 2008) and The Joanna Briggs Institute (2018) (JBI) have some of the best known critical appraisal tools for items to be reported in review studies. Both had limitations for assessing the nine studies under review due to their emphasis on experimental, quasi-experimental and systematic research. However, they assisted in the development of an adapted appraisal checklist to assess the theoretical synthesis and methodological rigor of studies reviewed. The quality appraisal checklist comprised five criteria, each of which was assessed on a three-point scale of 1 = low, 2 = medium and 3 = high (total score range: 5–15). These criteria related to the clarity of: population definitions; intervention, comparators, or critique; methodological approach; validity, reliability, and theory considerations; consistency of results, discussion, and limitations with the methodological framework stated. An overall quality assessment was determined by the mean of scores across the five quality appraisal criteria.

3. Results

Details from the nine research studies were extracted and entered in a summary table (Table 1), which included the research focus, methodology, and key findings relevant to women’s senior leadership representation and career advancement. An assessment of study quality was undertaken (Table 2), followed by a narrative overview of study outcomes. Barriers and facilitators of career advancement and interventions to support women’s advancement to the civil service upper echelons were the primary foci. Two studies critiqued the success of Indonesia’s merit based promotion system (Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b), both finding that merit based appointments were uncommon. One study mentioned policies on child supportive and flexible work arrangements for women (Azmi et al. 2012) as a mechanism to assist women to remain in the public service workforce, most often utilized by women in lower public service positions. There were no other policy interventions described for increasing women’s representation or career opportunities.

Table 1.

Overview of research studies and articles included, research design and findings.

Table 2.

Quality assessments of overviewed research studies (multiple papers from the same study assessed as one).

3.1. Overview of the Studies Included

Nine research studies, represented across 14 articles, were included in this review. Studies were categorized into three types: research on women in Indonesia’s civil service (Azmi et al. 2012; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017); research on women in public universities (quasi-public service in the Indonesian context) (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Murniati 2012; Toyibah 2018); and other relevant studies on women’s career advancement in to senior leadership in Indonesia (Nurak et al. 2018; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017; Simorangkir 2009).

Most of the studies (n = 5) had small sample sizes, discretely applying qualitative methods involving participant interviews (Azmi et al. 2012; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Murniati 2012; Simorangkir 2009; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017). While not generalizable, these studies provided rich insights into the way that career advancement barriers and facilitators are conceptualized by the researchers, as well as the participants interviewed. Three studies used either mixed-method (Nurak et al. 2018; Toyibah 2018) or multi-method (Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017) research designs. One study was an opinion based narrative overview utilizing purposively selected literature (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010). While all the studies had a focus on women’s opportunities for career advancement, there were five studies with specific focus on women upper echelon, academic leadership or executive positions (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017; Murniati 2012; Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010).

3.2. Quality of Studies

The quality of research across the studies was mixed, with three assessed as being low quality (Azmi et al. 2012; Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017), one medium quality (Shasrini and Wulandari 2017), and five as high quality (Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Murniati 2012; Nurak et al. 2018; Simorangkir 2009; Toyibah 2018) (Table 2). The only two studies specifically on Indonesian women’s career advancement in public service were assessed as low quality research, which was due to not clearly defining their samples and incomplete articulation of their research frameworks (Azmi et al. 2012; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017). Of the three studies concerning women in senior public service positions in public higher education institutions, one was likewise rated as poor in research quality (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010). The remaining two described the application of high-quality research frameworks (Kholis 2012a, 2012b; Murniati 2012). Three additional studies relevant to Indonesian women’s career opportunity and advancement were of medium to high quality (Nurak et al. 2018; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017; Simorangkir 2009). Of the five high quality studies, three were identifiable as having been PhD research undertaken at universities in developed countries (Kholis 2014; Murniati 2012; Simorangkir 2009).

3.3. Women’s Career Advancement to the Upper Echelons

All nine studies acknowledged that opportunities for women to advance to senior positions in Indonesia’s public service, academia, and the corporate world are low in comparison to that of men, and they either named or inferred patriarchal organizational cultures as responsible. One study identified how men’s voices are seen as legitimate when making unfounded assertions about women’s lack of leadership capacity (Murniati 2012). Alternatively, women were reported as being ostracized when outspoken about gender inequality, or when challenging the dominant masculine voice (Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017). Three studies identified the existence of homo-sociability in senior management that discursively reinforced favoritism towards, and a sense of comfort in having, male leaders (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Murniati 2012). Krissetyanti et al. (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017) found that even women who had succeeded to senior echelon positions in Indonesia’s public service were not immune from homo-sociability as many favored the employment of men as leaders. Despite Indonesia’s merit-based system for job selection, Kholis (2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017) found that interview processes were sexist, as they burdened women with questions about reproductive responsibilities that were not ask of men. In other jurisdictions, such questions constitute employment discrimination, which is illegal (Bartlett 2018; Gatrell et al. 2017).

Three studies named culture and Muslim beliefs, especially among conservative Islam supporters, as being adverse to women being leaders of men (Azmi et al. 2012; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017). Two studies explained how contemporary Muslim intellectuals could lead organizations, but that these women should not be in higher level jobs than their husbands (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Simorangkir 2009). This was reinforced by two other studies in which women’s incomes are generally viewed in Indonesian society as secondary to their husbands’ (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017). These dominant discourses construct leadership in the psyche of Indonesian women as being part of the ‘man’s world’; that men are ‘natural leaders’, and not women (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017).

Two studies indicated women’s participation in discourses that reinforced men’s perceived importance over women in both work and family life. For example, the first identified that women conformed to gender priorities of family over career (Azmi et al. 2012); the second displayed how women agreed with men that women’s reproductive work interfered with senior leadership capacity (Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017). Three studies asserted expectations of Indonesian women; that if they wanted a career, they should not let their reproductive work suffer (Shasrini and Wulandari 2017; Nurak et al. 2018; Murniati 2012). While this double burden exists, the women who succeeded to senior leadership had to out-perform men in their jobs (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017) and exceed in their education levels and/or skills (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010). However, women’s lack of access to formal and informal mentoring and support with promotions was noted in three studies (Azmi et al. 2012; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017). When women held lower level leadership positions, Kholis (2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017) noted how these women competed against each other for career advancement as opposed to engaging in a culture of support.

3.4. Strategies of Women Who Have Succeeded with Career Advancement

At the interpersonal level, the nine studies reviewed indicated workplace supports and strategies of women who had achieved promotion to the upper echelons, senior leadership or executive management. Consistently, the studies found that both career advancement and maintaining reputation as senior leaders required persistent efforts of the women. Two studies proposed that women’s educational achievements needed to surpass the educational levels of male counterparts to be competitive for career advancement to senior levels (Azmi et al. 2012; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017). Five of the studies identified how having the support of staff, particularly competent staff, reflected on leadership capability and opened up opportunities for further career advancement to more senior levels (Azmi et al. 2012; Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Murniati 2012; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017). Two of these studies found that the women’s interpersonal styles took on board the leadership traits of Indonesian men, which was perceived as necessary to gain respect as leaders (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Azmi et al. 2012).

While support from within the workplace was important, all nine studies explained how gender performativity in Indonesian culture required women to manage both their productive and reproductive work should they want a career. Accordingly, gaining support for career advancement from the women’s families was important across several studies (Toyibah 2018; Nurak et al. 2018; Azmi et al. 2012). ‘Support from family’ often meant convincing husbands and others that that they would not have to alleviate the women of their reproductive burdens (Toyibah 2018). Three studies suggested that women from middle- and upper-class families were more likely to advance their careers because: (1) they could afford higher education; and (2) could afford domestic help when the support of close family members was not available (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Murniati 2012). Murniati (2012) found that women with middle- and upper-class status more easily progressed to senior leadership positions, often requiring job rotations to regions away from family, because paid domestic workers enabled women to alleviate domestic constraints to pursue their careers.

In addition to receiving workplace and domestic support, five studies identified that successful Indonesian career women had a positive self-perception, aspirations for senior leadership, and a commitment to succeed at all odds (Toyibah 2018; Azmi et al. 2012; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Murniati 2012). Six studies stated that women either lacked confidence or did not have sufficient aspiration to vie for advancement to senior leadership (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Azmi et al. 2012; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Murniati 2012; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017; Simorangkir 2009). However, two of these studies argued that women were more likely to deny their ambition when unsuccessful in their career advancement, and ultimately become resigned to the gender inequality (Simorangkir 2009; Shasrini and Wulandari 2017). It appeared from four studies that women’s denial of ambition or resignation was often soured by sabotage, such as when women were assigned low prestige projects (Azmi et al. 2012), allocated heavy workloads (Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017), excluded from key networks (Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017), received few opportunities to showcase their leadership capacity (Simorangkir 2009), or by being assigned to a location that offered no career advancement (Nurak et al. 2018).

3.5. Strategies and Interventions to Support Women’s Career Advancement

Three macro interventions aimed to increase women’s career advancement to upper echelons, senior leadership or executive management were identified across the studies. These included equal opportunity policies (Azmi et al. 2012), workplace policies in support of flexible working arrangements for women (Azmi et al. 2012), and merit-based appointments in Indonesia’s public service (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017). Krissetyanti et al. (2017) found, despite the decree of merit-based civil service appointments in Indonesia, that dominant patriarchal practices compelled the relatively few women who succeeded in career advancement to co-participate with men in discrimination towards women. While Indonesia’s civil service system has made progress in gender responsive policy, barriers for women’s advancement have remained deeply entrenched and policy implementation is limited.

There were no micro-interventions or meso-programs identified in the literature specific to supporting women’s senior level career advancement in Indonesia. Despite this, the studies reviewed proposed several recommendations. Four studies proposed the development of stronger support networks among women, such as informal networking groups, identifying successful senior echelon public servants to mentor women aspiring to upper level careers, and formal career coaching (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Azmi et al. 2012; Murniati 2012). At the simplest level, Krissetyanti (2018a) suggested that women need support to develop positive self-image to overcome lack of confidence and resignation to the gender status quo. Secondly, Dzuhayatin and Edwards (2010) argued that women need assistance to identify career pathways and locate promotional opportunities.

4. Discussion

Two studies (Azmi et al. 2012; Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017) were located that specifically focused on women’s careers in Indonesia’s public service. Little could be garnered from these two studies; hence, the scope of the current review was extended to include relevant articles on Indonesia’s academic public service. Private sector research enabled socio-cultural aspects impeding women’s career advancement to senior public service positions to be observed.

The studies reviewed consistently depicted male domination of Indonesia’s upper echelons, senior leadership, or executive management. These groups of men are tasked with deciding on appointments of others to senior positions; male leaders are known to favor the appointment of other men (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017). Women in senior positions are, likewise, reported to favor male leadership (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017). Paradoxically, individuals become subsumed by discourse and they may concomitantly participate in it (McLaren 2016). In the case of both men and women favoring male leadership, their participation in homo-sociability reinforces appointment of mostly men to Indonesia’s upper level employment. This is to the detriment of merit-based appointments and other strategies aiming to improve women’s promotional opportunities and representation in upper echelons. What can be said about women’s career advancement to the upper echelon ranks of Indonesia’s public service, therefore, is that entrenched structures continue to disadvantage women irrespective of policies attempting to address them. Merit-based selections in Indonesia remain hampered by favoritism towards men as leaders and discrimination towards women with reproductive responsibilities. The barriers for women seeking advancement to senior roles is consistent with studies internationally, where combinations of both visible and invisible barriers persist (Xiang and Ingram 2017; Wesarat and Mathew 2017; Ndebele 2018; Amponsaa-Asenso 2018; Chitsamatanga et al. 2018).

In terms of strategies used by Indonesian women to advance their careers to senior levels, it appeared that ‘work’ to marshal career support was deemed an individual responsibility. The inequity, here, is that women are expected to make choices between career and family, whereas men are not (Krissetyanti 2018a, 2018b; Krissetyanti et al. 2017). Gender discourses compel women to sustain their reproductive work while engaging in productive work and in seeking career advancement (Nawaz and McLaren 2016). Negotiating this double burden is evident across the studies. It includes women’s negotiations with family, selection panels, and others, involving promises that career advancement would not domestically burden others (specifically men) (Azmi et al. 2012; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Nurak et al. 2018; Toyibah 2018; Murniati 2012). For modern Indonesian Muslim women, this means embracing traditions of domesticity irrespective of the women’s future career directions. While work-life balance may be easier for women in the upper echelons as they can afford paid domestic help (Murniati 2012), getting to the top is more difficult for women who are not from traditional middle- or upper-class families. It appears that many Indonesian women give up the fight and resign themselves to their lower level work.

5. Conclusions

The World Bank (2018, iii) report on women’s representation in Indonesia’s public service made a series of recommendations for increasing women’s representation, especially in the senior echelon ranks. This included: encouraging more women graduates to apply for the public service; engaging high-level dialogues aimed at implementing solutions to a ‘gender-based promotion penalty’ affecting women’s career advancement; and a leadership career mentoring program focused on pairing lower level women public servants with successful women leaders. However, the World Bank (2018) report cites no evidence that these actions will actually lead to increases women’s promotional opportunities and representation in the Indonesian public service upper echelons. The studies in this review (Dzuhayatin and Edwards 2010; Kholis 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2017; Azmi et al. 2012; Murniati 2012) suggest a promise in support schemes aimed at women’s advancement, such as peer mentoring and career coaching, but provide no evidence of potential effectiveness for the Indonesian context is not available as such schemes do not appear to exist. Further research and project work on the best designs for mobilizing Indonesian women’s advancement to the upper echelons is required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M., C.S. and I.W., methodology, H.M.; formal analysis, H.M., C.S. and I.W.; resources, H.M. and C.S.; data curation, H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, I.W. and C.S.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. and C.S.

Funding

This research was conducted in conjunction with funding received from the Australia Indonesia Institute: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian Government for the project entitled: Women’s public sector leadership: Learning from what works.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acar, F. Pinar, and H. Canan Sümer. 2018. Another test of gender differences in assignments to precarious leadership positions: Examining the moderating role of ambivalent sexism. Applied Psychology 67: 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan-Alolo, Namawu. 2007. Gender and corruption: Testing the new consensus. Public Administration and Development: The International Journal of Management Research and Practice 27: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsaa-Asenso, Esther. 2018. Career Progression of Women in the Accountancy Profession in Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly of Ghana. Cape Coast: University of Cape Coast. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, Edward. 2010. The irony of success. Journal of Democracy 21: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, Ilhaamie Abdul Ghani, Sharifah Hayaati Syed Ismail, and Siti Arni Basir. 2012. Women Career Advancement in Public Service: A Study in Indonesia. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 58: 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Stephen K. 2018. Ethics and the public service. In Classics of Administrative Ethics. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Katherine. 2018. Feminist legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Besley, Timothy, Olle Folke, Torsten Persson, and Johanna Rickne. 2017. Gender quotas and the crisis of the mediocre man: Theory and evidence from Sweden. American Economic Review 107: 220–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmüller, Susanne, Michelle K Ryan, Floor Rink, and S Alexander Haslam. 2014. Beyond the glass ceiling: The glass cliff and its lessons for organizational policy. Social Issues and Policy Review 8: 202–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, Louise, and Georgina Waylen. 2013. Gender and the hidden life of institutions. Public Administration 91: 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitsamatanga, Bellita Banda, Symphorosa Rembe, and Jenny Shumba. 2018. Promoting a Gender Responsive Organizational Culture to Enhance Female Leadership: A Case of Two State Universities in Zimbabwe. Anthropologist 32: 132–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, Isobel. 2010. The global glass ceiling: Why empowering women is good for business. Foreign Aff. 89: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Alison, and Christy Glass. 2014. Women and top leadership positions: Towards an institutional analysis. Gender, Work & Organization 21: 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove, Serena, and Kristi Lee. 2016. Persistence and resistance: Women’s leadership and ending gender-based violence in Guatemala. Seattle Journal for Social Justice 14: 8. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin, Jennifer. 2019. Feminist Innovations and New Institutionalism. In Gender Innovation in Political Science: New Norms, New Knowledge. Edited by Marrian Sawer and Kerryn Baker. Berlin: Springer, pp. 115–33. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, Silvia, Daniela Putzu, Diego Lasio, and Francesco Serri. 2018. The hegemonic gender order in politics. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 37: 832–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollar, David, Raymond Fisman, and Roberta Gatti. 2001. Are women really the “fairer” sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 46: 423–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dzuhayatin, Siti Ruhaini, and Jan Edwards. 2010. Hitting our Heads on the Glass Ceiling: Women and Leadership in Education in Indonesia. Studia Islamika 17: 203–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel, Catherine C., and Philip J. Grossman. 1998. Are women less selfish than men?: Evidence from dictator experiments. The Economic Journal 108: 726–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, Eahab, and Nancy D. Ursel. 2018. Re-examining the Glass Cliff Hypothesis using Survival Analysis: The Case of Female CEO Tenure. British Journal of Management 29: 156–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensour, Waed, Hadeel Al Maaitah, and Radwan Kharabsheh. 2017. Barriers to Arab female academics’ career development: Legislation, HR policies and socio-cultural variables. Management Research Review 40: 1058–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esarey, Justin, and Gina Chirillo. 2013. “Fairer sex” or purity myth? Corruption, gender, and institutional context. Politics & Gender 9: 361–89. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, Nick. 1999. Another ‘glass ceiling’?: The experiences of women professionals and managers on international assignments. Gender, Work & Organization 6: 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Gatrell, Caroline, Cary L. Cooper, and Ellen Ernst Kossek. 2017. Maternal bodies as taboo at work: New perspectives on the marginalizing of senior-level women in organizations. Academy of Management Perspectives 31: 239–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, Anne Marie. 2007. Political cleaners: Women as the new anti-corruption force? Development and Change 38: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, Anne Marie. 2018. National women’s machinery: State-based institutions to advocate for gender equality. In Mainstreaming Gender, Democratizing the State? Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haack, Kirsten. 2014. Gaining Access to the “World’s Largest Men’s Club”: Women Leading UN Agencies. Global Society 28: 217–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Ben. 2018. The Limits of Gender Quotas: Women’s Parliamentary Representation in Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Asia 48: 322–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Takeshi. 2011. Historicizing the power of civil society: a perspective from decentralization in Indonesia. The Journal of Peasant Studies 38: 413–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalzai, Farida. 2008. Women rule: Shattering the executive glass ceiling. Politics & Gender 4: 205–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jenter, Dirk, and Fadi Kanaan. 2015. CEO turnover and relative performance evaluation. The Journal of Finance 70: 2155–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholis, Nur. 2012a. Career advancement in Indonesian academia: A concern of gender discrimination. Jurnal Kependidikan Islam 2: 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kholis, Nur. 2012b. Gendered career productivity and success in academia in Indonesia’s Islamic higher education institutions. Journal of Indonesian Islam 6: 341–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholis, Nur. 2014. Academic Careers of Women and Men in Indonesia: Barriers and Opportunities. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Kholis, Nur. 2017. Barriers to Women’ s Career Aadvancement in Indonesian Academia: A qualitative empirical study. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR) 66: 158–64. [Google Scholar]

- Krissetyanti, E. P. L. 2018a. Gender bias on structural job promotion of civil servants in Indonesia (a case study on job promotion to upper echelons of civil service in the provincial government of the special region of Yogyakarta). In Topics in Social and Political Sciences, Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Research in Social Sciences and Humanities, Depok, Indonesia, 7–9 November 2016. Edited by Isbandi Rukminto Adi and Rochman Achwan. London: Routledge, pp. 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Krissetyanti, E. P. L. 2018b. Women’s Perceptions about Glass Ceiling in their Career Development in Local Bureaucracy in Indonesia. Bisnis & Birokrasi Journal 25: 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Krissetyanti, E. P. L., Eko Prasojo, and Azhar Kasim. 2017. Meritocracy And Gender Equity: Opportunity For Women Civil Service To Occupy The High Leader Position In Local Bureaucracy In Indonesia. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 167: 107–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kulich, Clara, Vincenzo Iacoviello, and Fabio Lorenzi-Cioldi. 2015. Refining the conditions and causes of the glass cliff. In Gender and Social Hierarchies: Perspectives from Social Psychology. Edited by Klea Faniko, Fabio Lorenzi-Cioldi, Oriane Sarasin and Eric Mayor. London: Routledge, pp. 104–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kymlicka, Will, and Ruth Rubio-Marin. 2018. The Participatory Turn in Gender Equality and its Relevance. In Gender Parity and Multicultural Feminism: Towards a New Synthesis. Edited by Ruth Rubio-Marin and Will Kymlicka. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Manurung, Hendra. 2017. Indonesia’s Democracy under Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo Leaderships: Constructing human rights in the globalization (2014–2019). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, Susan. 2013. Women as Agents of Change: Having Voice in Society and Influencing Policy. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, Helen Jaqueline. 2016. Adult women groomed by child molesters’ heteronormative dating scripts. Women’s Studies International Forum 56: 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Ross H. 2008. Inadequate budgets and salaries as instruments for institutionalizing public sector corruption in Indonesia. South East Asia Research 16: 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailova, Julija, and Inna Melnykovska. 2009. Gender, corruption and sustainable growth in transition countries. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences 4: 387–407. [Google Scholar]

- Murniati, Cecilia Titiek. 2012. Career advancement of women senior academic administrators in Indonesia: Supports and challenges. Educational Policy and Leadership Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, Educational Policy and Leadership Studies, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, Faraha, and Helen Jaqueline McLaren. 2016. Silencing the hardship: Bangladeshi women, microfinance and reproductive work. Social Alternatives 35: 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ndebele, Clever. 2018. Gender and School Leadership: Breaking the Glass Ceiling in South Africa. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies 7: 1582–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Benjamin J. 2016. Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Local Gender-Based Earnings Inequality and Women’s Belief in the American Dream. American Journal of Political Science 60: 1006–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurak, Lusia Adinda Dua, Armanu Thoyib, Noermijati Noermijati, and I. Gede Riana. 2018. The Relationship between Work-Family Conflict, Career Success Orientation and Career Development among Working Women in Indonesia. International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration 4: 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Leary, Rosemary. 2015. From Silos to Networks: Hierarchy to Heterarchy 1. In Public Administration Evolving: From Foundations to the Future. Edited by Mary E. Guy and Rubin Maralyn M. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, Deborah A., and Margaret M. Hopkins. 2015. The impact of gendered organizational systems on women’s career advancement. Frontiers in psychology 6: 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Omar, Ogenyi, and Victoria Ogenyi. 2004. A qualitative evaluation of women as managers in the Nigerian Civil Service. International Journal of Public Sector Management 17: 360–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Seejeen. 2019. Dusk for the pyramid-shaped bureaucracy: examining the shape of the US federal bureaucracy in the twenty first century. Quality & Quantity 53: 1565–85. [Google Scholar]

- Picardi, Ilenia. 2019. The Glass Door of Academia: Unveiling New Gendered Bias in Academic Recruitment. Social Sciences 8: 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Michelle K., S. Alexander Haslam, Thekla Morgenroth, Floor Rink, Janka Stoker, and Kim Peters. 2016. Getting on top of the glass cliff: Reviewing a decade of evidence, explanations, and impact. The Leadership Quarterly 27: 446–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartika, Dewi, Noneng N. Kormara, and Nina Setiana. 2018. Three women who are Echelon 2 ranked civil servants from West Java Government and Bandung Municipal Government. Paper presented at the High-Level Meetings with the researchers at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, Provided an Explanation of Indonesia’s Echelon Ranks, Adelaide, Australia, November 27. [Google Scholar]

- Shahan, Asif M., and Rizwan Khair. 2018. Inclusive Governance for Enhancing Professionalism in Civil Service: The Case of Bangladesh. In Inclusive Governance in South Asia. Edited by N Ahmed. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 123–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shasrini, Tessa, and Happy Wulandari. 2017. Existence of Glass Ceiling in Private University, Riau Indonesia, Were They being Obstructed? Paper presented at the 3rd World Conference on Media and Mass Communication, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, April 21–22; Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte: TIIKM, pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Simorangkir, Deborah. 2009. Has the Glass Ceiling Really been Broken?-The Impacts of the Feminization of the Public Relations Industry in Indonesia. Doctor of Philosophy. Ph.D. Thesis, Fakultät für Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften, Technische Universität Ilmenau, Ilmenau, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Hung-En. 2012. Women in government, public corruption, and liberal democracy: a panel analysis. Crime, Law and Social Change 58: 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, Anand, Stephen Knack, Young Lee, and Omar Azfar. 2001. Gender and corruption. Journal of Development Economics 64: 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2018. Critical Appraisal Tools. The University of Adelaide. Available online: http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical-appraisal-tools.html (accessed on 30 January 2018).

- Tidey, Sylvia. 2018. A tale of two mayors: configurations of care and corruption in eastern Indonesian direct district head elections. Current Anthropology 59: S117–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyibah, Dzuriyatun. 2018. The Gender Gap and Career Path of the Academic Profession Under the Civil Service System at a Religious University in Jakarta, Indonesia. Komunitas: International Journal of Indonesian Society and Culture 10: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatikiotis, Michael R.J. 2013. Indonesian Politics under Suharto: The Rise and Fall of the New Order, 3rd ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers, Adrian. 2013. A history of modern Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, Erik, Douglas G. Altman, Matthias Egger, Stuart J. Pocock, Peter C. Gøtzsche, and Jan P. Vandenbroucke. 2008. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology [STROBE] statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Gaceta Sanitaria 22: 144–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesarat, Phathara-on, and Jaya Mathew. 2017. Theoretical Framework of Glass Ceiling: A Case of India’s Women Academic Leaders. Paradigm 21: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widianingsih, Ida, Helen Jaqueline McLaren, and Janet McIntyre-Mills. 2018. Decentralization, Participatory Planning, and the Anthropocene in Indonesia, with a Case Example of the Berugak Dese, Lombok, Indonesia. In Balancing Individualism and Collectivism: Social and Environmental Justice. Edited by Janet McIntyre-Mills, Norma Romm and Yvonne Corcoran-Nantes. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 271–84. [Google Scholar]

- Widianingsih, Ida, and Elizabeth Morrell. 2007. Participatory planning in Indonesia: seeking a new path to democracy. Policy Studies 28: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2018. Mapping Indonesia’s Civil Service. South Jakarta: The World Bank Office Jakarta. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Xiaoxue, and Jay Ingram. 2017. Barriers Contributing to Under-Representation of Women in High-level Decision-making Roles across Selected Countries. Organization Development Journal 35: 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Yukongdi, Vimolwan, and John Benson. 2005. Women in Asian management: cracking the glass ceiling? Asia Pacific Business Review 11: 139–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Xuejiao, and Hua Daniel Xu. 2015. E-government and corruption: A longitudinal analysis of countries. International Journal of Public Administration 38: 410–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Chunyan, Jiahui Ai, and Sida Liu. 2017. The Elastic Ceiling: Gender and professional career in Chinese courts. Law & Society Review 51: 168–99. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).