Cross-National Attunement to Popular Songs across Time and Place: A Sociology of Popular Music in the United States, Germany, Thailand, and Tanzania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

It can now be said with assurance that individuals are dominated in their behavior by complex hierarchies of interlocking rhythms. Furthermore, these same interlocking rhythms are compatible to fundamental themes in a symphonic score, a keystone in the interpersonal processes between mates, co-workers, and organizations of all types on the interpersonal level within as well as across cultural boundaries. I am convinced that it will ultimately be proved that almost every facet of human behavior is involved in the rhythmic process.

When popular music is repeated to such a degree that it does not any longer appear to be a device but rather an inherent element of the natural world, resistance assumes a different aspect because the unity of individuality begins to crack.

Consume music in order to be allowed to weep. They are taken in by the musical expression of frustration rather than by that of happiness. The so-called releasing element of music is simply the opportunity to feel something. But the actual content of this emotion can only be frustration. Emotional music has become the image of the mother who says, “Come and weep, my child.” It is catharsis for the masses, but catharsis which keeps them all the more firmly in line. One who weeps does not resist any more than one who marches. Music that permits its listeners the confession of their unhappiness reconciles them, by means of this “release”, to their social dependence.

2. Methods

2.1. Selection of the Song Intros

2.2. Description of the Intros

2.3. Survey Instrument

2.4. Administration of the Survey

- (1)

- Sociology classrooms in Chico, California, 2015 (N = 70).

- (2)

- Korean Exchange students in Chico, California, 2015 (N = 31).

- (3)

- German and international students at Leuphana University, Germany 2015 and 2016 (N = 57).

- (4)

- International and Thai students at Payap University, Chiangmai, Thailand 2016, (N = 92).

- (5)

- Undergraduate students at Stefano Moshi Memorial University (SMUCCO), Moshi, Tanzania 2016 (N = 33).

- (6)

- Undergraduate Students at Midland University in Midland Nebraska 2015, (N = 33).

- (7)

- Grass Valley, California, Church, Adult Education Class (N = 40). 2015.

3. Results

3.1. Results (Quantitative)

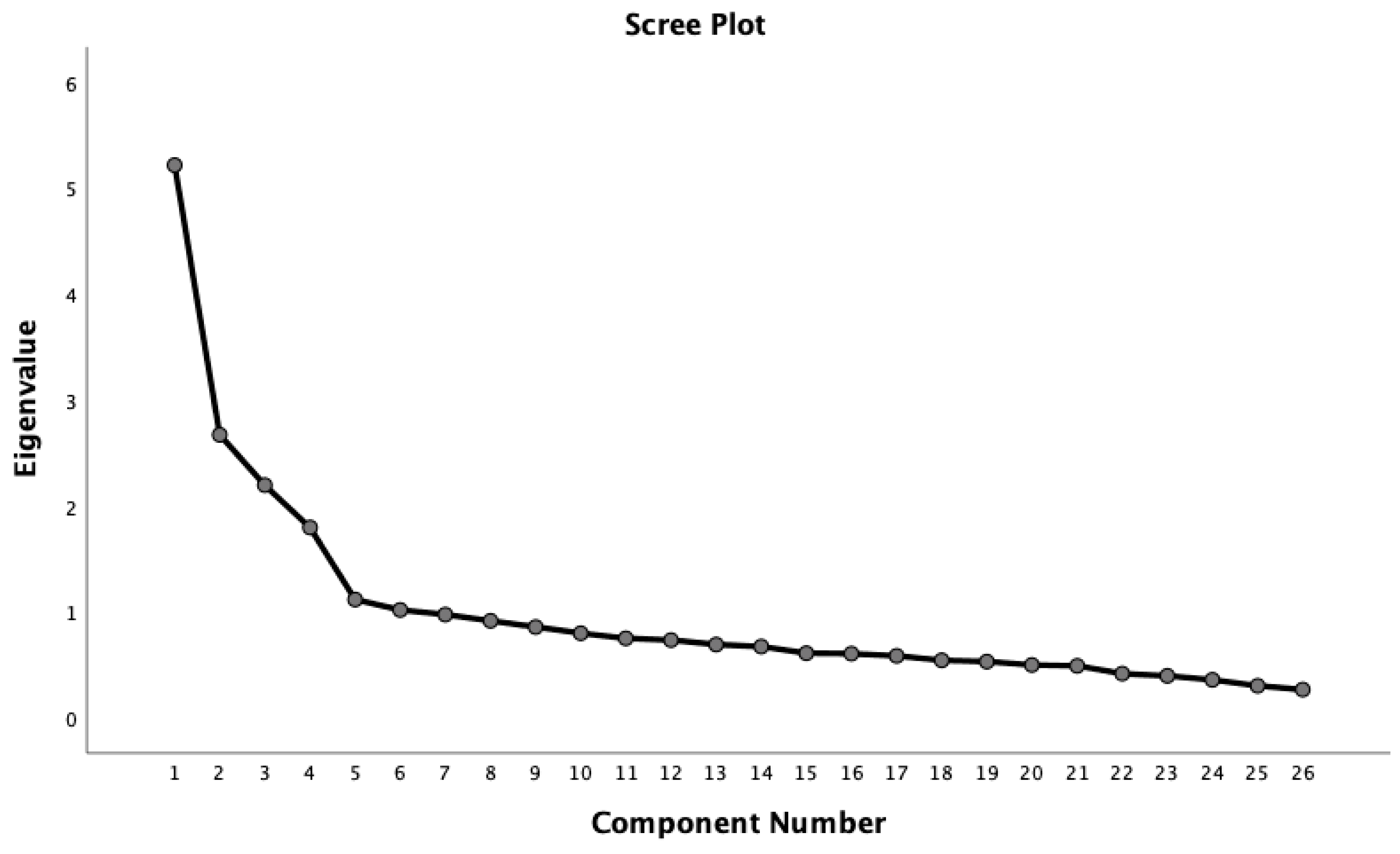

3.1.1. Factor Analysis.

3.1.2. Positive Correlations between Songs

3.1.3. Negative Correlations between Songs

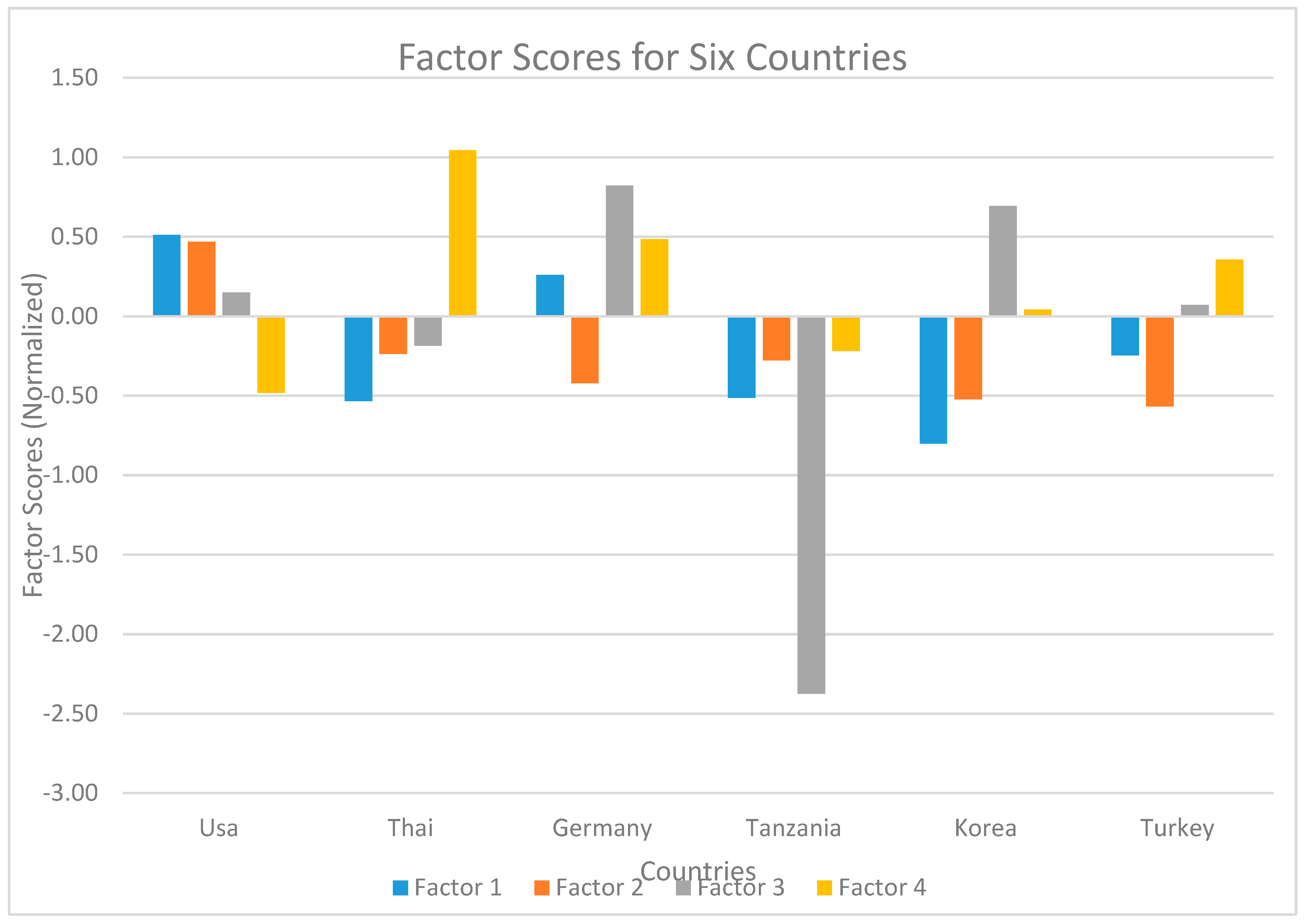

3.2. Country Breakdowns

3.3. Age Breakdown—Americans over 60 and under 30

3.4. Qualitative Comments

4. Discussion

4.1. The Original Thesis

It can now be said with assurance that individuals are dominated in their behavior by complex hierarchies of interlocking rhythms. Furthermore, these same interlocking rhythms are compatible to fundamental themes in a symphonic score, a keystone in the interpersonal processes between mates, co-workers, and organizations of all types on the interpersonal level within as well as across cultural boundaries. I am convinced that it will ultimately be proved that almost every facet of human behavior is involved in the rhythmic process.

4.2. What the Data Show

4.3. Music Recognition as a Methodology in Culture Studies

4.4. Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adorno, Theodor. 1941. On Popular Music. I. The Musical Material. In Studies in Philosophy and Social Science. New York: Institute of Social Research, vol. 9, pp. 17–48. Available online: http://www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/DATABASES/SWA/On_popular_music_1.shtml (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Ball, Philip. 2010. The Music Instinct: How Music Works and Why We Can’t Do without It. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2016. Musical Twin Cities Emerge from Data. BBC. January 14. Available online: http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-35290619 (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- DuBois, William Edward Burghardt. 1903. The Souls of Black Folk. Available online: http://web.archive.org/web/20081004090243/http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/DubSoul.html (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Durkheim, Emile. 1973. On Morality and Society. Edited by Robert Bellah. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Egermann, Hauke, Nathalie Fernando, Lorraine Chuen, and Stephen McAdams. 2015. Music induces universal emotion-related psychophysiological responses: Comparing Canadian listeners to Congolese Pygmies. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feher, Ferenc. 1987. Weber and the Rationalization of Music. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 1: 337–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, Simon. 1998. Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, Simon. 2004. Towards and Aesthetic of Popular Music. In Popular Music Critical Concepts in Media and Cultural Studies, Vol IV, Music and Identity. Edited by Simon Frith. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward T. 1983. The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Levitin, Daniel J. 2006. This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession. New York: Dutton. [Google Scholar]

- Mauch, Matthias, Robert M. MacCallum, Mark Levy, and Armand Leroi. 2015. The Evolution of Popular Music: USA 1960–2010. Royal Society Open Science, May 6. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, Richard. 1990. Studying Popular Music. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, Murray. 1993. The Soundscape: The Tuning of the World. Rochester: Destiny Books. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, John. 2006. Cultural Theory and Poplar Culture, 3rd ed. New York: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Tagg, Philip. 1997. Understanding musical time sense. In Tvarspel—Festskrift for Jan Ling (50 år). Göteborg: Skriften fran Musikvetenskapliga. First published 1984. Available online: https://www.tagg.org/articles/xpdfs/timesens.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Waters, Tony. 2014. Of Looking Glasses, Mirror Neurons, Culture, and Meaning. Perspectives on Science 22: 616–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, Tony. 2018. Max Weber and the Modern Problem of Discipline. Lanham: Hamilton Books. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2015. Charisma and Discipline. In Weber’s Rationalism and Modern Society. Edited by Tony Waters and Dagmar Waters. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. First published 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1978. The History of the Piano. In Weber: Selections in Translation. Edited by Walter G. Runciman. Translated by Eric Matthews. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, pp. 378–82. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Tagg (Tagg [1984] 1997, pp. 1–2) has a similar argument but is not quite as reductionist as E. T. Hall. In his paper about music and time, Tagg writes in his article “Understanding Musical Time Sense” that “Such varying sets of rules governing musical structuration in different cultures and subcultures contribute strongly to the construction of ideology by establishing different symbolic universes of affective, gestural and corporeal attitudes or behavior.” This statement is I think consistent with what Hall writes. |

| 2 | The mechanism for understanding this is probably embedded in mirror neurons which are a basis for the empathy via which the culture of music, nature, speech, and all other linguistic elements are acquired. See (Waters 2014). |

| 3 | For a critique of Adorno’s pessimism, and appreciation of Adorno’s ideas about commodification of music, see (Frith 1998, pp. 13–14). |

| 4 | Cultural theorists of the Birmingham School like Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams (see Storey 2006), have developed this point broadly, particularly in the context of modern capitalism. |

| 5 | The attuned worker is in Max Weber’s term a “disciplined worker” whose psycho-biological being is rationalized to the factory, bureaucracy, or other large rationalized social institution. Weber writes: “the point of such rational discipline is that rationalized orders are executed when received in a predictable fashion. This happens because the execution of any received command emerges from tactical responses that are conditioned reactions to precise drills. In the context of such drills, all personal critique is unconditionally deferred, and personal convictions are constantly adjusted towards the pre-determined goal reflected in how the received order is executed.” Predictability, tactical responses, and precise drills are all undertaken reference to underlying culturally-generated rhythm. See (Weber [1921] 2015, p. 59; Waters 2018). |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Marcos Zepeda contributed to the selection of songs, and testing them with his fellow students. |

| 8 | Tagg (Tagg [1984] 1997) developed similar ideas about the same time as E. T. Hall, though they did not reference each other. Tagg (Tagg [1984] 1997, p. 1) writes of the role of culture and “time sense.” He writes of the “cultural skill of decoding the ‘meaning’ of the sounds in the form of an adequate response.” He connects musical elements including tempo, linear time, cyclical times, present time, and hierarchies of duration. This, he claims, is correlated with different traditions from agricultural societies in Europe and Asia. Notably for Tagg this “time sense” is separate from the newer time sense correlated with modern capitalism. |

| Rotated Component Matrix a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song | Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Ice Ice Baby | 0.763 | |||

| Fresh Prince of Bel Air | 0.704 | |||

| Born to Run | 0.632 | |||

| Free Bird | 0.567 | |||

| 60 Minutes Clock | 0.531 | |||

| Somewhere—Iz | 0.528 | 0.333 | ||

| Happy | 0.523 | −0.495 | ||

| Don’t Stop | 0.506 | |||

| Let it Be | 0.417 | 0.334 | ||

| Teach the World to Sing | 0.727 | |||

| As Time Goes By | 0.673 | |||

| We Shall Overcome | 0.672 | |||

| America the Beautiful | 0.525 | 0.561 | ||

| Marlboro Commercial | 0.378 | 0.527 | ||

| Los Tigres del Norte | 0.488 | |||

| I Love Lucy | 0.416 | |||

| TID—Zeze | −0.667 | |||

| Fur Elise | 0.649 | |||

| Somewhere | 0.309 | 0.644 | ||

| Ode to Joy | 0.642 | |||

| So. African National Anthem | 0.326 | −0.549 | ||

| Moon Represents | 0.682 | |||

| Loi Katong | 0.670 | |||

| Chevrona Ruta | 0.583 | |||

| Made in Thailand | 0.567 | |||

| Tagesschau | 0.449 | |||

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. a | ||||

| Song Title | Correlates With | Researchers Comments |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Let it Be | Free Bird | The Beatles Are Less Enduring than we Thought |

| Somewhere | ||

| Fuer Elise | ||

| Ice Ice Baby | ||

| (2) Free Bird | Let it Be | Very American set of correlations |

| America the Beautiful | ||

| Don’t Stop | ||

| Somewhere—Iz Version | ||

| Fresh Prince | ||

| Ice Ice Baby | ||

| Born to Run | ||

| (3) South African National Anthem | TID Zeze | Tanzania |

| (4) America the Beautiful | Fresh Prince | Most American set |

| Marlboro | ||

| Free Bird | ||

| Somewhere | ||

| I Love Lucy | ||

| Los Tigres Del Norte/La Mesa del Rincon | ||

| We Shall Overcome | ||

| Born to Run | ||

| I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | ||

| (5) Don’t Stop | Born to Run | American baby boomers |

| Free Bird | ||

| Somewhere—Iz | ||

| (6) Made in Thailand | Moon Represents | Chinese music made it to Thailand, but not to Germany, California, or Tanzania |

| (7) Ode to Joy | Somewhere | The correlations with the German Tagesschau is surprisingly low |

| Fuer Elise | Two songs from Beethoven correlate, though not as strongly as others | |

| (8) Somewhere | Ode to Joy | |

| Let it Be | ||

| America the Beautiful | ||

| Somewhere—Iz | ||

| Ice Ice Baby | ||

| (9) 60 Minutes Clock | Fresh Prince | Gen X recognizes the 60 Minutes clock, but not older people |

| Ice Ice Baby | ||

| (10) Moon Represents | Made in Thailand | China and Thailand go together |

| Loi Katong | ||

| (11) Chervona Ruta | (None) | This was included as a control. |

| (12) Somewhere—Iz | Free Bird | |

| Don’t Stop | ||

| Somewhere | ||

| Fresh Prince | ||

| (13) I Love Lucy | Don’t Stop | Older Americans who remember the 1992 presidential campaign? |

| (14) Happy | Ice Ice Baby | Only one strong correlation. Probably due to the more global recognition |

| (15) Fuer Elise | Let it Be | This goes across generations, and from Germany to the US |

| Ode to Joy | ||

| Ice Ice Baby | ||

| (16) TID Zeze | South African National Anthem | Tanzania |

| (17) Fresh Prince | Ice Ice Baby | Younger Americans are patriotic Americans, too. |

| America the Beautiful | ||

| Free Bird | ||

| 60 Minutes | ||

| Somewhere—Iz | ||

| (18) Los Tigres del Norte | America the Beautiful | Perhaps Latinos are patriotic—and elderly like Latino music, too. |

| As Times Go By | ||

| We Shall Overcome | ||

| (19) Ice Ice Baby | Fresh Prince of Bel Air | Gen X American youth anthems |

| Happy | ||

| Let it Be | ||

| Free Bird | ||

| Somewhere | ||

| 60 Minutes | ||

| Born to Run | ||

| (20) As Time Goes By | We Shall Overcome | Elderly and Latinos |

| I’d Like to Teach | ||

| Lost Tigres del Norte | ||

| (21) We Shall Overcome | America the Beautiful | American Patriotism from the elderly and Latinos |

| Los Tigres del Norte | ||

| Marlboro | ||

| I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | ||

| (22) Born to Run | Don’t Stop | |

| Free Bird | ||

| America the Beautiful | ||

| Ice Ice Baby | ||

| (23) Tagesschau | (None) | |

| (24) Loi Kathong | Moon Represents | |

| (25) Marlboro | America the Beautiful | Marlboro was generally equated with “Bonanza” |

| I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | ||

| (26) I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | As Time Goes By | Coca-cola, Casablanca, Civil Rights, and Cigarettes. |

| We Shall Overcome | ||

| America the Beautiful | ||

| Marlboro |

| Song Title | Correlates With | Correlation | Researchers Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| South African National Anthem | Let It Be | −0.107 * | Tanzania Missed on Beethoven and the Beatles |

| Ode to Joy | −1.12 * | ||

| Somewhere | −0.174 ** | ||

| Fuer Elise | −0.198 ** | ||

| Ice Ice Baby | −0.124 * | ||

| Happy | As Time Goes By | −0.190 ** | Elders missed 2014 pop hit Happy |

| We Shall Overcome | −0.208 ** | ||

| I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | −0.231 ** | ||

| Tagesschau | I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | −0.114 * | |

| TID Zeze | Fuer Elise | −0.339 ** | Tanzanians again—the missed out on Beethoven and the Beatles |

| Somewhere | −0.276 ** | ||

| Ode to Joy | −0.268 ** | ||

| America the Beautiful | −0.155 ** | ||

| Let it Be | −0.120 * |

| Percent Recognizing Particular Song Clips | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song Clip | USA | Turkey | Thai | Tanzania | Korea | Germany |

| (N = 149) | (N = 10) | (N = 34) | (N = 33) | (N = 34) | (N = 36) | |

| Ice Ice Baby | 72% | 56% | 30% | 13% | 29% | 89% |

| Fresh Prince of Bel Air | 56% | 22% | 6% | 13% | 3% | 44% |

| Born to Run | 38% | 22% | 15% | 9% | 3% | 31% |

| Free Bird | 57% | 22% | 21% | 16% | 16% | 47% |

| 60 Minutes Clock | 52% | 33% | 21% | 9% | 19% | 25% |

| Somewhere - Iz | 79% | 78% | 64% | 16% | 42% | 97% |

| Happy | 72% | 100% | 88% | 75% | 61% | 94% |

| Don’t Stop | 42% | 0% | 30% | 16% | 19% | 36% |

| Let it Be | 65% | 33% | 42% | 13% | 84% | 83% |

| America the Beautiful | 92% | 11% | 18% | 16% | 6% | 36% |

| Marlboro Commercial | 79% | 56% | 36% | 19% | 13% | 56% |

| I Love Lucy | 66% | 44% | 39% | 34% | 32% | 31% |

| Los Tiegres del Norte | 43% | 22% | 21% | 13% | 3% | 28% |

| Teach the World to Sing | 46% | 11% | 30% | 22% | 6% | 22% |

| As Time Goes By | 35% | 22% | 36% | 13% | 29% | 25% |

| We Shall Overcome | 55% | 33% | 33% | 6% | 16% | 56% |

| Somewhere | 97% | 33% | 58% | 13% | 97% | 94% |

| Fur Elise | 97% | 100% | 88% | 25% | 94% | 100% |

| TID—Zeze | 3% | 0% | 15% | 75% | 6% | 6% |

| So. African National Anthem | 19% | 22% | 9% | 72% | 3% | 14% |

| Ode to Joy | 72% | 78% | 55% | 6% | 77% | 97% |

| Tagesschau | 14% | 44% | 27% | 3% | 42% | 100% |

| Made in Thailand | 11% | 11% | 76% | 13% | 3% | 17% |

| Chevrona Ruta | 7% | 33% | 27% | 13% | 6% | 11% |

| Moon Represents | 23% | 11% | 64% | 19% | 35% | 36% |

| Loi Katong | 9% | 22% | 36% | 13% | 13% | 14% |

| Song | Eta | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Let it Be | 0.424 | 53.088 |

| (2) Free Bird | 0.371 | 40.659 |

| (3) South African National Anthem | 0.464 | 63.843 |

| (4) America the Beautiful | 0.755 | 168.289 |

| (5) Don’t Stop | 0.242 | 17.338 * |

| (6) Made in Thailand | 0.513 | 78.030 |

| (7) Ode to Joy | 0.501 | 74.224 |

| (8) Somewhere | 0.734 | 159.446 |

| (9) 60 Minutes Clock | 0.338 | 33.800 |

| (10) Moon Represents | 0.282 | 22.047 |

| (11) Chevrona Ruta | 0.228 | 15.381 * |

| (12) Somewhere—Iz | 0.449 | 73.784 |

| (13) I Love Lucy | 0.230 | 58.77 |

| (14) Happy | 0.259 | 19.796 |

| (15) Fuer Elise | 0.709 | 148.631 |

| (16) TID Zeze | 0.654 | 126.294 |

| (17) Fresh Prince | 0.444 | 58.178 |

| (18) Los Tigres del Norte | 0.305 | 27.367 |

| (19) Ice Ice Baby | 0.502 | 74.119 |

| (20) As Time Goes By | 0.172 | 8.727 ** |

| (21) We Shall Overcome | 0.376 | 41.674 |

| (22) Born to Run | 0.293 | 25.302 |

| (23) Tagesschau | 0.637 | 119.783 |

| (24) Loi Kathong | 0.239 | 16.781 * |

| (25) Marlboro | 0.466 | 74.442 |

| (26) I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | 0.298 | 26.050 |

| 17–30 Years Old (N = 95) | 60 and Older (N = 38) | Difference | Independent t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Let it Be | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.14 | 1.50 ns |

| (2) Free Bird | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 1.76 ns |

| (3) South African National Anthem | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.11 | −1.43 ns |

| (4) America the Beautiful | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.13 | −3.69 p < 0.001 |

| (5) Don’t Stop | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 1.78 ns |

| (6) Made in Thailand | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.02 | −0.18 ns |

| (7) Ode to Joy | 0.61 | 0.95 | 0.34 | −5.41 p < 0.001 |

| (8) Somewhere | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.04 | −2.03 p < 0.05 |

| (9) 60 Minutes Clock | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 4.91 p < 0.001 |

| (10) Moon Represents | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.03 | −0.47 ns |

| (11) Chervona Ruta | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.23 ns |

| (12) Somewhere—Israel K. | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 2.67 p < 0.01 |

| (13) I Love Lucy | 0.56 | 0.79 | 0.23 | −2.74 p < 0.01 |

| (14) Happy | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 18.91 p < 0.001 |

| (15) Fuer Elise | 0.96 | 1.00 | 0.04 | −2.03 p < 0.05 |

| (16) TID Zeze | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | −0.57 ns |

| (17) Fresh Prince | 0.79 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 15.38 p < 0.001 |

| (18) Los Tigres del Norte | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.25 | −2.65 p < 0.01 |

| (19) Ice Ice Baby | 0.95 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 18.91 p < 0.001 |

| (20) As Time Goes By | 0.14 | 0.74 | 0.60 | −7.44 p < 0.001 |

| (21) We Shall Overcome | 0.34 | 0.97 | 0.63 | −11.50 p < 0.001 |

| (22) Born to Run | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.29 | 3.84 p = 0.001 |

| (23) Tagesschau | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 3.55 p < 0.001 |

| (24) Loi Kathong | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 1.92 ns |

| (25) Marlboro | 0.67 | 0.97 | 0.30 | −4.13 p < 0.001 |

| (26) I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | 0.19 | 0.97 | 0.81 | −16.26 p < 0.001 |

| Song | Summary of Qualitative Comments |

|---|---|

| (1) Let it Be | 159 comments. Is correctly associated with The Beatles and “Let it Be” by most. Low recognition by Thai and Tanzanian. |

| (2) Free Bird | 96 comments. Typically associated with Free Bird and Lynyrd Skynyrd. Recognized primarily in the United States. |

| (3) South African National Anthem | 58 comments. 10 associated with church. 17 Associated it with Africa and/or South Africa. Most positive responses came from Tanzania. |

| (4) America the Beautiful | 144 comments. Most associated it with American patriotism. 9 associated it with Coca-Cola |

| (5) Don’t Stop | 92 comments. Associated with Fleetwood Mac. Also “t.v. show.” |

| (6) Made in Thailand | 54 comments. Recognized by Thai students, and some of the other students living in Thailand. |

| (7) Ode to Joy | 147 comments. German students recognized it as the European Anthem, Freude Schoene Gottefunken, Americans as “Ode to Joy,” and Koreans and Thai as “church music.” |

| (8) Somewhere | 242 comments. Associated correctly with Wizard of Oz and/or Judy Garland by about 140. However, some interference from from other singers. But minor. This was recognized properly except in Tanzania. |

| (9) 60 Minutes Clock | 128 comments. Younger Americans recognized it as associated with an American news show. About half associated it with a clock. |

| (10) Moon Represents | 77 comments. Most common response that it was a “Chinese song (13 comments). Four or five wrote the Chinese characters. Few referred to the title in English. Most commonly recognized in Thailand, and by Korean students. |

| (11) Chervona Ruta | 24 comments. Four students associated the song with Turkey—one Thai, and three Turkish students. One association with Cambodia, and another with Asia. No students associated it with Ukraine. |

| (12) Somewhere—Iz | 174 comments. Correctly identified in many iterations as the Hawaiian version of Over the Rainbow with a ukulele. Also recognized as part of the Adam Sandler movie “50 First Dates” (5), commercials (5), cartoon music associated with Tom and Jerry (12), and Bruno Mars (2). |

| (13) I Love Lucy | 136 comments. 34 associations with cartoons, particularly Tom and Jerry. The association was strongest among the Korean students. Older Americans tended to associate it correctly with “I Love Lucy” at the highest rates. |

| (14) Happy | 228 comments. Everybody except the older Americans and Tanzanians. Two people thought it was Bruno Mars, but most correctly placed it as Pharrell Williams. |

| (15) Fuer Elise | 228 comments. Most associated with Beethoven and the Fuer Elise. Others included ring tones (7), and piano lessons (34). |

| (16) TID Zeze | 38 comments. Very familiar in Tanzania. Two students in Thailand identified it by name. Nowhere else. |

| (17) Fresh Prince | 102 comments. Mostly from the United States, and younger. |

| (18) Los Tigres del Norte | 69 comments. Students from both Nebraska and Mexico refer to family. Six refer to Germany/Russia. Four refer to polkas. |

| (19) Ice Ice Baby | 167 comments. Most young people associated it with Ice and Ice Baby/Vanilla Ice. Five associated with Queen. Others with MC Hammer. |

| (20) As Time Goes By | 73 comments. Associated with jazz and old movies. |

| (21) We Shall Overcome | 117 comments. 50 associated with church and Christmas. 20 identified it as “We Shall Overcome.” |

| (22) Born to Run | 68 comments. 20 identified it correctly. |

| (23) Tagesschau | 114 comments. All Germans recognized it. Others from everywhere except Tanzania identified it as the lead-in to the news. |

| (24) Loi Kathong | 47 comments. Typically associated with Chinese or other Asian music. 6 o7 identify as Thai. No one identified Loi Katong. |

| (25) Marlboro | 140 comments. Primarily associated with Bonanza, and other western shows. No association with Marlboro or commercial. |

| (26) I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing | 60 comments. 15 associated it with Coca-cola or a commercial. Just 7 identified it by name. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Waters, T.; Philhour, D. Cross-National Attunement to Popular Songs across Time and Place: A Sociology of Popular Music in the United States, Germany, Thailand, and Tanzania. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110305

Waters T, Philhour D. Cross-National Attunement to Popular Songs across Time and Place: A Sociology of Popular Music in the United States, Germany, Thailand, and Tanzania. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(11):305. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110305

Chicago/Turabian StyleWaters, Tony, and David Philhour. 2019. "Cross-National Attunement to Popular Songs across Time and Place: A Sociology of Popular Music in the United States, Germany, Thailand, and Tanzania" Social Sciences 8, no. 11: 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110305

APA StyleWaters, T., & Philhour, D. (2019). Cross-National Attunement to Popular Songs across Time and Place: A Sociology of Popular Music in the United States, Germany, Thailand, and Tanzania. Social Sciences, 8(11), 305. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110305