The Development of Generalized Trust among Young People in England

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is the level of generalized trust among young people in Great Britain today and how does that relate to other kinds of social trust?

- How has generalized trust developed over the life course of the current generation of young people?

- How influential are socio-economic conditions experienced during early adulthood by comparison to other factors shaping generalized trust among young people?

2. Generalized Trust: What Is It and What Influences It?

2.1. Defining the Concept

2.2. Explaining Generalized Trust

3. Data Sources, Variables and Methods of Analysis

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variables

3.3. Methods of Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Levels and Interrelations of Different Forms of Trust

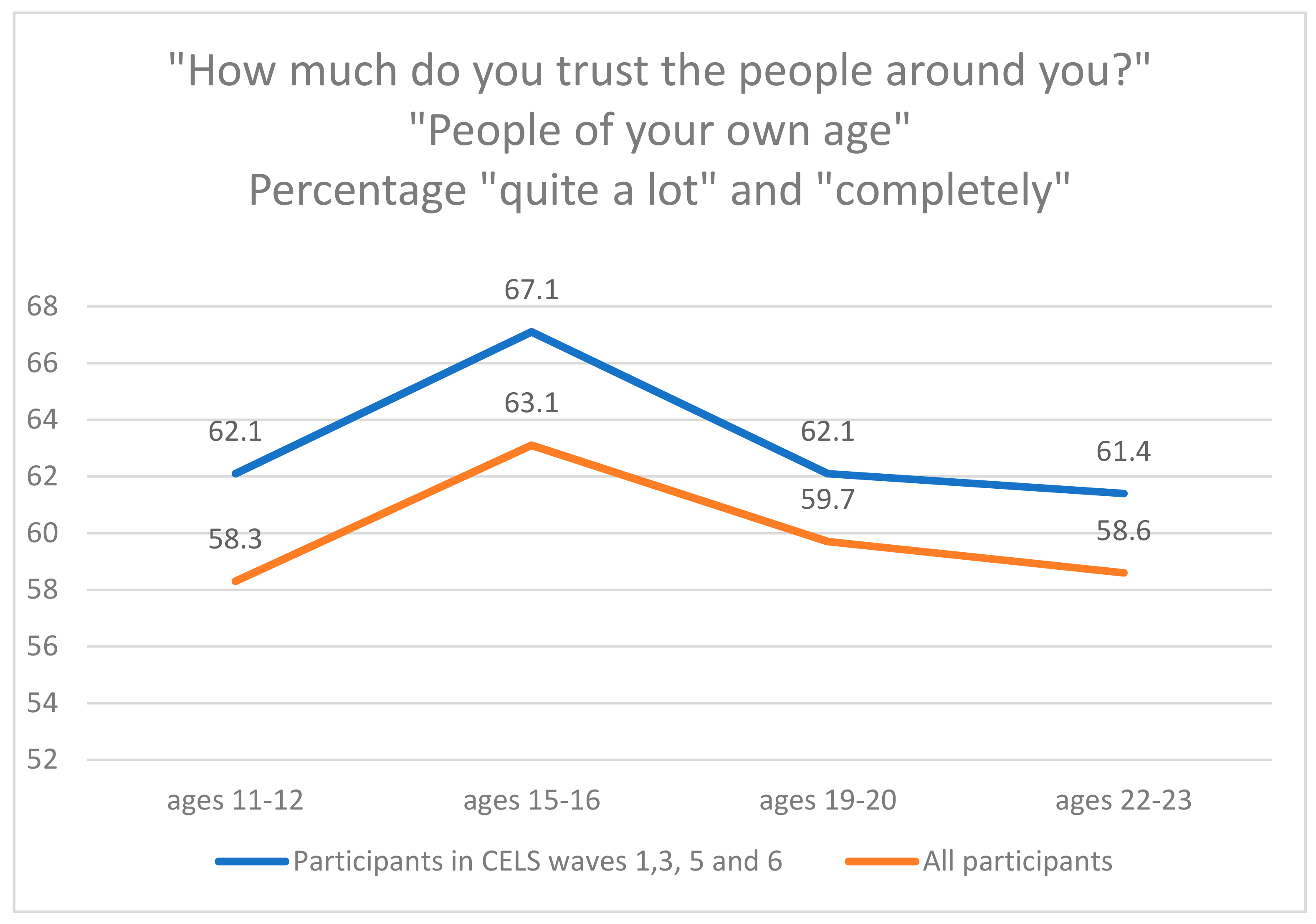

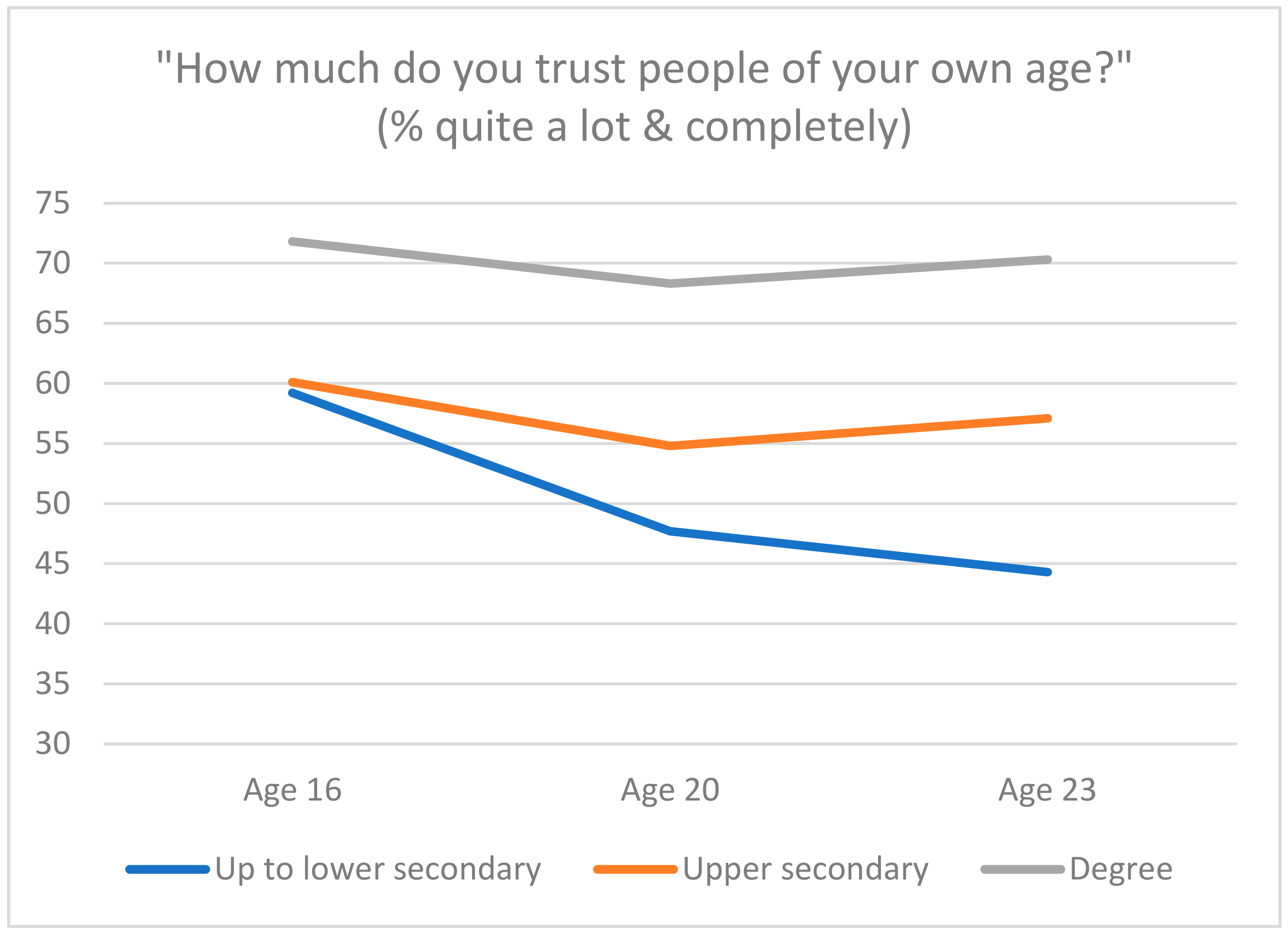

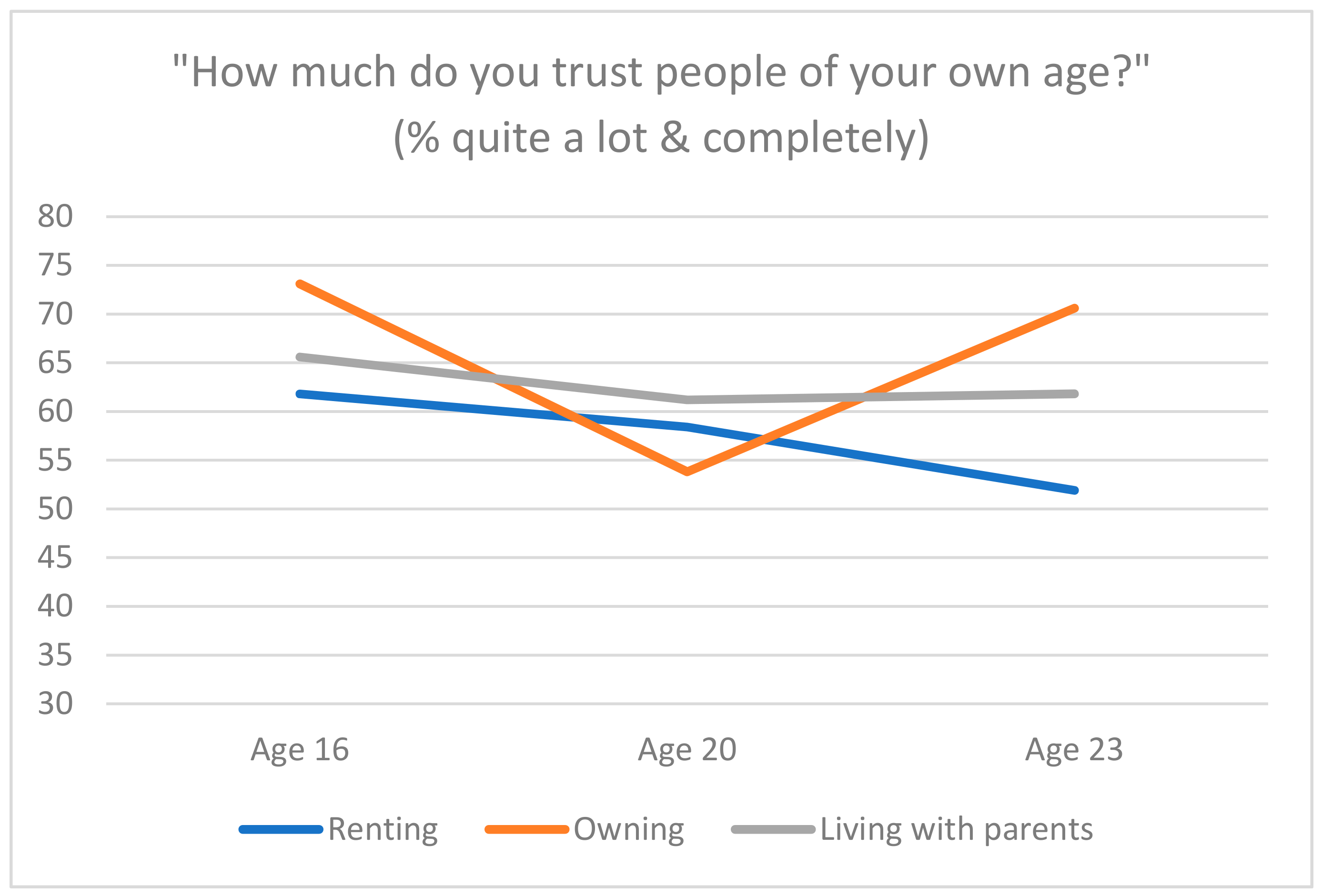

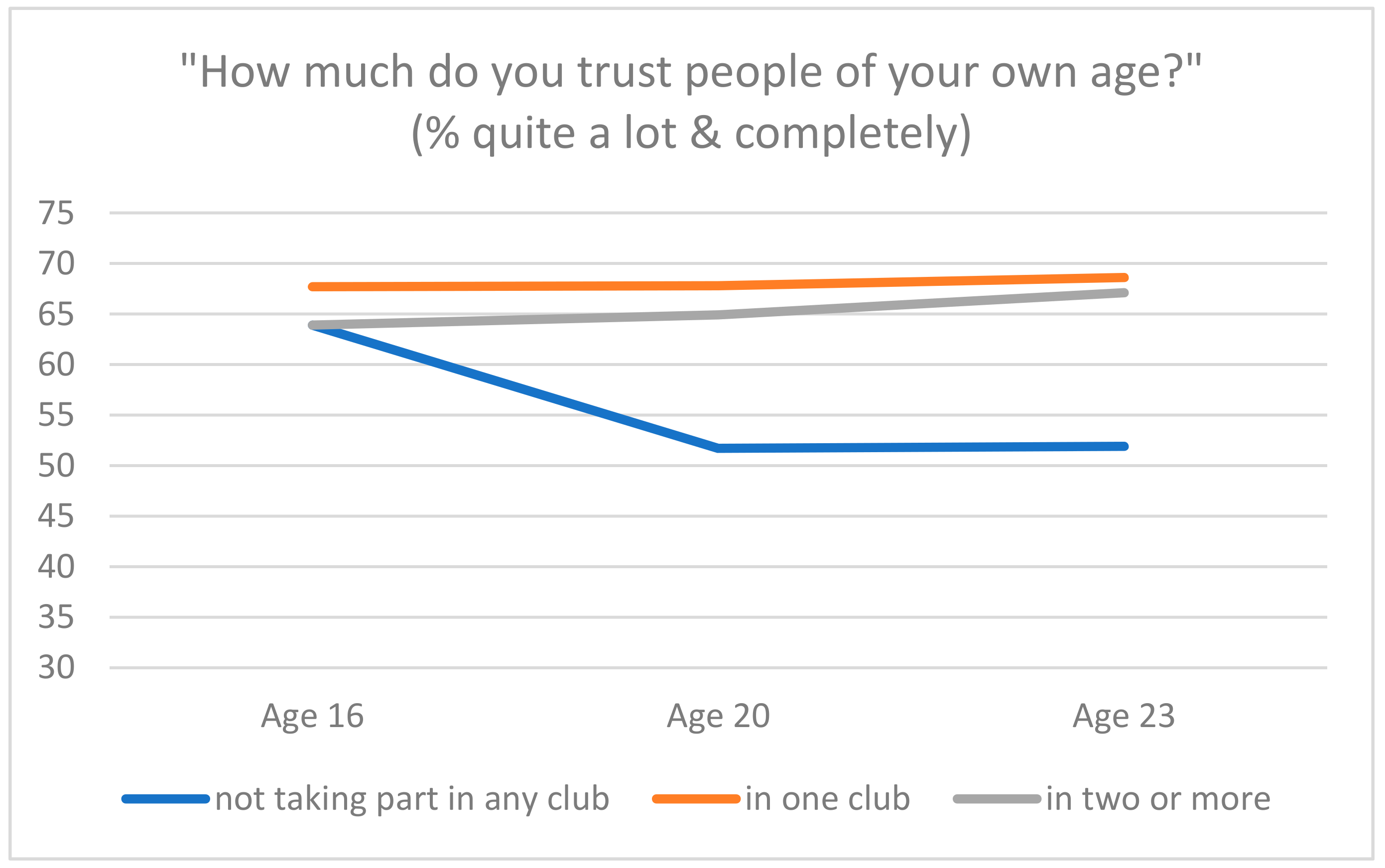

4.2. The Development of Generalized Trust over the Life Course

4.3. The Determinants of Generalized Trust

4.4. The Determinants of Educational Attainment, Tenure and Civic Participation

5. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbott, Stephen, and Della Freeth. 2008. Social capital and health starting to make sense of the role of generalized trust and reciprocity. Journal of Health Psychology 13: 874–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelzadeh, Ali, and Erik Lundberg. 2017. Solid or Flexible? Social Trust from Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood. Scandinavian Political Studies 40: 207–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, Harol, Jere Behrman, Hans-Peter Kohler, John Maluccio, and Susan Cotts Watkins. 2001. Attrition in Longitudinal Household Survey Data. Demographic Research 5: 79–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, Tom, David Kerr, and Joana Lopes. 2008. Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study (CELS): Sixth Annual Report Young People’s Civic Participation in and Beyond School: Attitudes, Intentions and Influences. London: DCSF. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørnskov, Christian. 2007. Determinants of generalized trust: A cross-country comparison. Public Choice 130: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, Christian. 2012. How does social trust affect economic growth? Southern Economic Journal 78: 1346–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, John, and Wendy Rahn. 1997. Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science 41: 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, Ronald. 2005. Brokerage and Closure: In Introduction to Social Capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, David. 2006. What is education’s impact on civic and social engagement? In Measuring the Effects of Education on Health and Civic/Social Engagement. Edited by Richard Desjardins and Tom Schuller. Paris: OECD/CERI, pp. 25–126. [Google Scholar]

- Claibourn, Michele P., and Paul S. Martin. 2000. Trusting and Joining? An Empirical Test of the Reciprocal Nature of Social Capital. Political Behaviour 22: 267–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhey, Jan, and Kenneth Newton. 2003. Who Trusts? The Origins of Social Trust in Seven Societies. European Societies 5: 93–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPasquale, Denise, and Edward Glaeser. 1998. Incentives and Social Capital: Are Homeowners Better Citizens? NBER Working Paper 6363. Cambridge: Harvard University and NBER. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, Kenneth. 1995. Fear of Crime. Albany: State University Press of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, Steven. 1995. Causal Analysis with Panel Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Constance, and Michael Stout. 2010. Developmental patterns of social trust between early and late adolescence: Age and school climate effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence 20: 748–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambetta, Diego. 1988. Can we trust trust? In Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Edited by Diego Gambetta. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Glanville, Jennifer, and Pamela Paxton. 2015. How Do We Learn to Trust?: A Confirmatory Tetrad Analysis of the Sources of Generalized Trust. ASA Working paper. Washington: American Sociological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Andy, Jan Germen Janmaat, and Helen Cheng. 2011. Social cohesion: Converging and diverging trends. National Institute Economic Review 215: 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, Russell. 1999. Do we want to trust in government? In Democracy and Trust. Edited by Mark Warren. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hirashi, Kai, Shinji Yamagata, Chizuru Shikishima, and Juku Ando. 2008. Maintenance of genetic variation in personality through control of mental mechanisms: A test of trust, extraversion and agreeableness. Evolution and Human Behavior 29: 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howker, Ed, and Shiv Malik. 2013. Jilted Generation: How Britain has Bankrupted Its Youth. London: Icon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jian, Henriette Maassen van den Brink, and Wim Groot. 2009. A meta analysis of the effect of education on social capital. Economics of Education Review 28: 454–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Jian, Henriette Maassen van den Brink, and Wim Groot. 2011. College Education and Social Trust: An Evidence-Based Study on the Causal Mechanisms. Social Indicators Research 104: 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janmaat, Jan Germen. 2016. Values in times of austerity: A cross-national and cross-generational analysis. Citizenship Teaching and Learning 11: 267–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahne, Joseph, David Crow, and Nam Jin Lee. 2013. Different Pedagogy, Different Politics: High School Learning Opportunities and Youth Political Engagement. Political Psychology 34: 419–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Hannah. 2015. Young people and the predictability of precarious transitions. In Defense of Welfare 2. Edited by Liam Foster, Anne Brunton, Chris Deeming and Tina Haux. York: The Social Policy Organisation, pp. 143–45. [Google Scholar]

- Knack, Stephen, and Phillip Keefer. 1997. Does social capital have an economic pay-off? A cross-country investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112: 1251–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, Stephen, and Paul Zak. 2002. Building trust: Public policy, interpersonal trust, and economic development. Supreme Court Economic Review 10: 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauglo, Jon. 2011. Political socialization in the family and young people’s educational achievement and ambition. British Journal of the Sociology of Education 32: 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, James. 2015. (Dis)placing Trust: The Long-Term Effects of Job Displacement on Generalized Trust over the Adult Lifecourse. Social Science Research 50: 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yaojun, Andrew Pickles, and Mike Savage. 2005. Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review 21: 109–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, Martin. 2009. Psychosocial work conditions, unemployment, and generalized trust in other people: A population-based study of psychosocial health determinants. The Social Science Journal 46: 584–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopaciuk-Gonczaryk, Beata. 2019. Does participation in social networks foster trust and respect for other people—Evidence from Poland. Sustainability 11: 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manturuk, Kim, Mark Lindblad, and Roberto Quercia. 2010. Friends and Neighbours: Homeownership and Social Capital among Low—to Moderate—Income Families. Journal of Urban Affairs 32: 471–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Peter, and Kirsten Besemer. 2015. Social networks, social capital and poverty: Panacea or placebo? Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 23: 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthen, Linda, and Bengt Muthen. 2009. Mplus User’s Guide, 5th ed. Muthen & Muthen: Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Oskarsson, Sven, David Cesarini, Christopher Dawes, James Fowler, Magnus Johannesson, Patrik Magnusson, and Jan Teorell. 2015. Linking Genes and Political Orientations: Testing the Cognitive Ability as Mediator Hypothesis. Political Psychology 36: 649–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, Lindsay. 2013. Comprehensive education, social attitudes and civic engagement. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 4: 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, Pamela. 1999. Is Social Capital Declining in the United States? A Multiple Indicator Assessment. American Journal of Sociology 105: 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, Pamela. 2007. Association memberships and generalized trust: A multilevel model across 31 countries. Social Forces 86: 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, Hillary, and Gary Pollock. 2015. “Politics are bollocks”: Youth, politics and activism in contemporary Europe. The Sociological Review 63: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert. 2007. E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century, the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies 30: 137–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, Julian. 1971. Generalized Expectancies for Interpersonal Trust. American Psychologist 26: 443–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, Wolfram, John Ainly, Julian Fraillon, David Kerr, and Bruno Losito. 2010. ICCS 2009 International Report: The Civic Knowledge, Attitudes and Engagement among Lower Secondary School Students in 38 Countries. Amsterdam: IEA. [Google Scholar]

- Shildrick, Tracy, Robert MacDonald, Colin Webster, and Kayleigh Garthwaite. 2012. Poverty and Insecurity: Life in Low-Pay, No-Pay Britain. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stack, Lois C. 1978. Trust. In Dimensions of Personality. Edited by Harvey London and John Exner. New York: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 561–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, Dietlind. 2003. The Sources of Social Capital. In Generating Social Capital: Civil Society and Institutions in Comparative Perspective. Edited by Dietlind Stolle and Marc Hooghe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stolle, Dietlind, and Marc Hooghe. 2004. The Roots of Social Capital: Attitudinal and Network Mechanisms in the Relation between Youth and Adult Indicators of Social Capital. Acta Politica 39: 422–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolle, Dietlind, and Thomas Rochon. 1998. Are All Associations Alike? Member Diversity, Associational Type and the Creation of Social Capital. American Behavioral Scientist 42: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubager, Rune. 2008. Education effects on authoritarian-libertarian values: A question of socialization. British Journal of Sociology 59: 327–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturgis, Patrick, Sanna Read, Peter Hatemi, Gu Shu, Tim Trull, Margaret Wright, and Nicholas Martin. 2010. A genetic basis for social trust? Political Behavior 32: 205–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgis, Patrick, Roger Patulny, Nick Allum, and Franz Buscha. 2012. Social Connectedness and Generalized Trust: A Longitudinal Study. ISER Working Paper Series; Wollongong: University of Wollongong. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, Imogen. 2013. Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner, Eric M. 2002. The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner, Eric M., and Mitchell Brown. 2005. Inequality, trust, and civic engagement. American Politics Research 33: 868–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, Lea. 2007. Experiential differences between voluntary and involuntary job redundancy on depression, job-search activity, affective employee outcomes and re-employment quality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 80: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, Dieter, Andrea Waylen, and Muthanna Samara. 2009. Selective drop-out in longitudinal studies and non-biased prediction of behaviour disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 195: 249–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollebaek, Dag, and Kristin Strømsnes. 2008. Voluntary associations, trust and civic engagement: A multi-level approach. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 37: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrightsman, Lawrence. 1992. Assumptions about Human Nature: Implications for Researchers and Practitioners. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wuthnow, Robert. 1997. The Role of Trust in Civic Renewel. Working Paper #1. College Park: National Commission on Civic Renewal. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | It should also be noted that a recent strand in the literature has explored whether and to what extent trust has a genetic basis (Hirashi et al. 2008; Sturgis et al. 2010; Oskarsson et al. 2015). Sturgis et al. (2010), for instance, found that a majority of the variation in social trust can be explained by a genetic factor. We neither challenge these findings nor engage with this literature in greater depth because we are primarily interested in environmental influences on trust, i.e., influences that can be changed through interventions. Even if most of the variation in trust could be explained by nature, that still leaves a considerable part to be accounted for by factors amenable to manipulation. |

| 2 | These figures are based on the longitudinal sample. As this sample suffers from selective attrition (as noted before), the results should not be understood as nationally representative. |

| Variable | Category (%) | Wave | Valid N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | |||

| Generalized trust | 6 | 585 (98.2) | |

| Not at all | 3.9 | ||

| A little | 35.9 | ||

| Quite a lot | 54.9 | ||

| Completely | 5.3 | ||

| Independent | |||

| Education mother | 6 | 493 (82.7) | |

| Left full time education at 15 or 16 | 52.1 | ||

| Left after college or sixth form | 28.2 | ||

| Studied at university/got a degree | 19.7 | ||

| Education father | 6 | 492 (82.6) | |

| Left full time education at 15 or 16 | 56.9 | ||

| Left after college or sixth form | 23.4 | ||

| Studied at university/got a degree | 19.7 | ||

| Books at home | 3 | 591 (99.2) | |

| 0 books | 2.2 | ||

| 1–10 books | 10.2 | ||

| 11–50 books | 22.3 | ||

| 51–100 books | 20.6 | ||

| 101–200 books | 18.6 | ||

| More than 200 books | 26.1 | ||

| Ethnic background | 6 | 593 (99.5) | |

| Asian | 10.5 | ||

| Black | 1.5 | ||

| White British | 84.5 | ||

| Other | 3.5 | ||

| Educational attainment * | 6 | 595 (99.8) | |

| Level 1 | 5.0 | ||

| Level 2 vocational | 5.7 | ||

| Level 2 academic (GCSE: 5 A to Cs) | 10.3 | ||

| Level 3 vocational (NVQ or Btech) | 13.8 | ||

| Level 3 academic (A levels) | 10.8 | ||

| Level 4 vocational | 7.4 | ||

| Degree or higher | 45.9 | ||

| Other qualifications | 1.2 | ||

| Tenure | 6 | 590 (99.0) | |

| Social rent, living independently | 5.1 | ||

| Private rent, living independently | 18.3 | ||

| Owner, living with parents | 41.4 | ||

| Renting, living with parents | 11.9 | ||

| Owner, living independently | 8.8 | ||

| Other living arrangement | 14.6 | ||

| Current activity | 6 | 596 (100.0) | |

| Working | 80.9 | ||

| In education | 7.7 | ||

| Something else | 11.4 | ||

| Active civic participation | 6 | 596 (100.0) | |

| In none of these clubs/groups | 49.5 | ||

| In one of these clubs/groups | 37.4 | ||

| In two of these clubs/groups | 10.9 | ||

| In three of these clubs/groups | 2.0 | ||

| In four of these clubs/groups | 0.2 | ||

| Control variables | |||

| Gender | 6 | 596 (100.0) | |

| Boy | 48.0 | ||

| Girl | 52.0 | ||

| Generalized trust | 3 | 580 (97.3) | |

| Not at all | 4.8 | ||

| A little | 29.8 | ||

| Quite a lot | 55.0 | ||

| Completely | 10.3 |

| How Much Do You Trust the People Around You? | Generally Speaking, Would You Say That Most People Can Be Trusted or You Cannot Be Too Careful in Dealing with People? | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Quite a Lot’ and ‘Completely’ (%) | ‘Most People Can Be Trusted’ (%) | |

| Your family | 90.8 | |

| Your colleagues | 62.2 | |

| Your employer | 55.6 | |

| People of your own age | 53.9 | |

| People of a different nationality | 46.7 | |

| Your neighbours | 46.0 | |

| People of a different religion | 43.7 | |

| People you meet for the first time | 21.6 | |

| 36.4 |

| Generalized Trust | |

|---|---|

| Your family | 0.16 *** |

| Your employer | 0.25 *** |

| Your neighbours | 0.29 *** |

| Your colleagues | 0.30 *** |

| People of your own age | 0.31 *** |

| People of a different religion | 0.37 *** |

| People of a different nationality | 0.38 *** |

| People you meet for the first time | 0.44 *** |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Your family | 0.17 | 0.81 |

| Your colleagues | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| Your employer | 0.60 | 0.61 |

| Your neighbours | 0.66 | 0.49 |

| People of your own age | 0.67 | 0.44 |

| People you meet for the first time | 0.81 | 0.22 |

| People of a different nationality | 0.84 | 0.27 |

| People of a different religion | 0.84 | 0.25 |

| Most people can be trusted | 0.63 | 0.15 |

| Correlation Factor 1 × Factor 2: 0.32 | ||

| Correlation | Explained Variance (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Trust age 12 × trust age 16 | 0.09 | 0.5 |

| Trust age 16 × trust age 20 | 0.28 *** | 7.5 |

| Trust age 20 × trust age 23 | 0.36 *** | 12.7 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Trust | Generalized Trust | Generalized Trust | ||||

| Beta | (SE) | Beta | (SE) | Beta | (SE) | |

| Education mother | ||||||

| Left full time education at 15/16 | −0.10 | (0.07) | −0.08 | (0.07) | −0.07 | 0(0.07) |

| Left after college or sixth form | −0.12 | (0.06) | −0.10 | (0.06) | −0.10 | (0.07) |

| Studied at university (ref cat) | ||||||

| Education father | ||||||

| Left full time education at 15/16 | −0.01 | (0.07) | −0.05 | (0.07) | −0.02 | (0.07) |

| Left after college or sixth form | −0.02 | (0.06) | −0.05 | (0.06) | −0.04 | (0.07) |

| Studied at university (ref cat) | ||||||

| Books at home | −0.03 | (0.05) | 0.04 | (0.05) | −0.01 | (0.05) |

| Ethnic background | ||||||

| Asian | −0.08 | (0.04) | −0.04 | (0.04) | −0.07 | (0.04) |

| Black (ref cat for Model 3) | −0.06 | (0.04) | −0.06 | (0.04) | −0.05 | (0.04) |

| Other | −0.01 | (0.04) | −0.01 | (0.04) | −0.00 | (0.04) |

| White British (ref cat) | ||||||

| Gender (1 = boy; 2 = girl) | 0.01 | (0.04) | −0.01 | (0.04) | −0.01 | (0.04) |

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| Other qualifications | −0.05 | (0.04) | −0.04 | (0.04) | ||

| Level 1 | −0.1 * | (0.04) | −0.11 * | (0.04) | ||

| Level 2 vocational | −0.12 ** | (0.04) | −0.10 * | (0.04) | ||

| Level 2 academic | −0.08 | (0.04) | −0.06 | (0.04) | ||

| Level 3 vocational | −0.11 * | (0.04) | −0.08 | (0.04) | ||

| Level 3 academic | −0.02 | (0.04) | −0.01 | (0.04) | ||

| Level 4 vocational | −0.07 | (0.04) | −0.06 | (0.04) | ||

| Degree or higher (ref cat) | ||||||

| Tenure | ||||||

| Social rent, independent | −0.16 ** | (0.05) | −0.15 ** | (0.05) | ||

| Private rent, independent | −0.15 * | (0.07) | −0.14 * | (0.06) | ||

| Owner, living with parents | −0.10 | (0.07) | −0.08 | (0.07) | ||

| Renting, living with parents | −0.06 | (0.06) | −0.07 | (0.06) | ||

| Other living arrangement | −0.07 | (0.06) | −0.05 | (0.06) | ||

| Owner, independent (ref cat) | ||||||

| Current activity | ||||||

| Working | 0.03 | (0.05) | 0.05 | (0.05) | ||

| In education | −0.06 | (0.05) | −0.04 | (0.05) | ||

| Something else (ref cat) | ||||||

| Active civic participation | 0.08 * | (0.04) | 0.09 * | (0.04) | ||

| Generalized trust Wave 3 | 0.20 *** | (0.04) | ||||

| R square (%) | 9.3 | 2.1 | 13.2 | |||

| Having a Degree | Social Rent, Living Independently | Active Civic Participation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logit | (SE) | Logit | (SE) | Beta | (SE) | |

| Education mother | ||||||

| Left full time education at 15 / 16 | −0.20 | (0.18) | 0.40 | (0.47) | −0.13 * | (0.06) |

| Left after college or sixth form | −0.16 | (0.19) | 0.44 | (0.45) | −0.11 | (0.06) |

| Studied at university (ref cat) | ||||||

| Education father | ||||||

| Left full time education at 15 / 16 | −0.61 ** | (0.18) | 0.77 | (0.52) | 0.03 | (0.06) |

| Left after college or sixth form | −0.45 * | (0.18) | 0.90 | (0.49) | 0.04 | (0.06) |

| Studied at university (ref cat) | ||||||

| Books at home | 0.23 *** | (0.05) | −0.09 | (0.08) | 0.16 *** | (0.05) |

| Ethnic background | ||||||

| Asian | 1.29 | (0.70) | 4.95 | (4.56) | 0.08 | (0.11) |

| Black (ref cat) | ||||||

| Other | 1.28 | (0.73) | 5.58 | (5.56) | 0.03 | (0.07) |

| White British | 0.85 | (0.68) | 5.24 | (4.98) | −0.04 | (0.11) |

| Gender (1 = boy; 2 = girl) | 0.19 | (0.11) | 0.56 *** | (0.02) | −0.17 *** | (0.04) |

| Generalized trust wave 3 | 0.19 * | (0.08) | −0.06 | (0.16) | −0.04 | (0.04) |

| R square (%) | 23.0 | 43.0 | 9.0 | |||

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janmaat, J.G. The Development of Generalized Trust among Young People in England. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110299

Janmaat JG. The Development of Generalized Trust among Young People in England. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(11):299. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110299

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanmaat, Jan Germen. 2019. "The Development of Generalized Trust among Young People in England" Social Sciences 8, no. 11: 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110299

APA StyleJanmaat, J. G. (2019). The Development of Generalized Trust among Young People in England. Social Sciences, 8(11), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110299