1. Introduction

In recent years, crowdfunding has become an alternative source of external funding for a project that has a profit or non-profit orientation in various countries. Crowdfunding has been growing until now because the number of successful crowdfunding projects is increasing. Besides, among the various types of crowdfunding, reward-based crowdfunding is one of the most widely used by project owners and backers (

Belleflamme et al. 2014;

Mollick 2014).

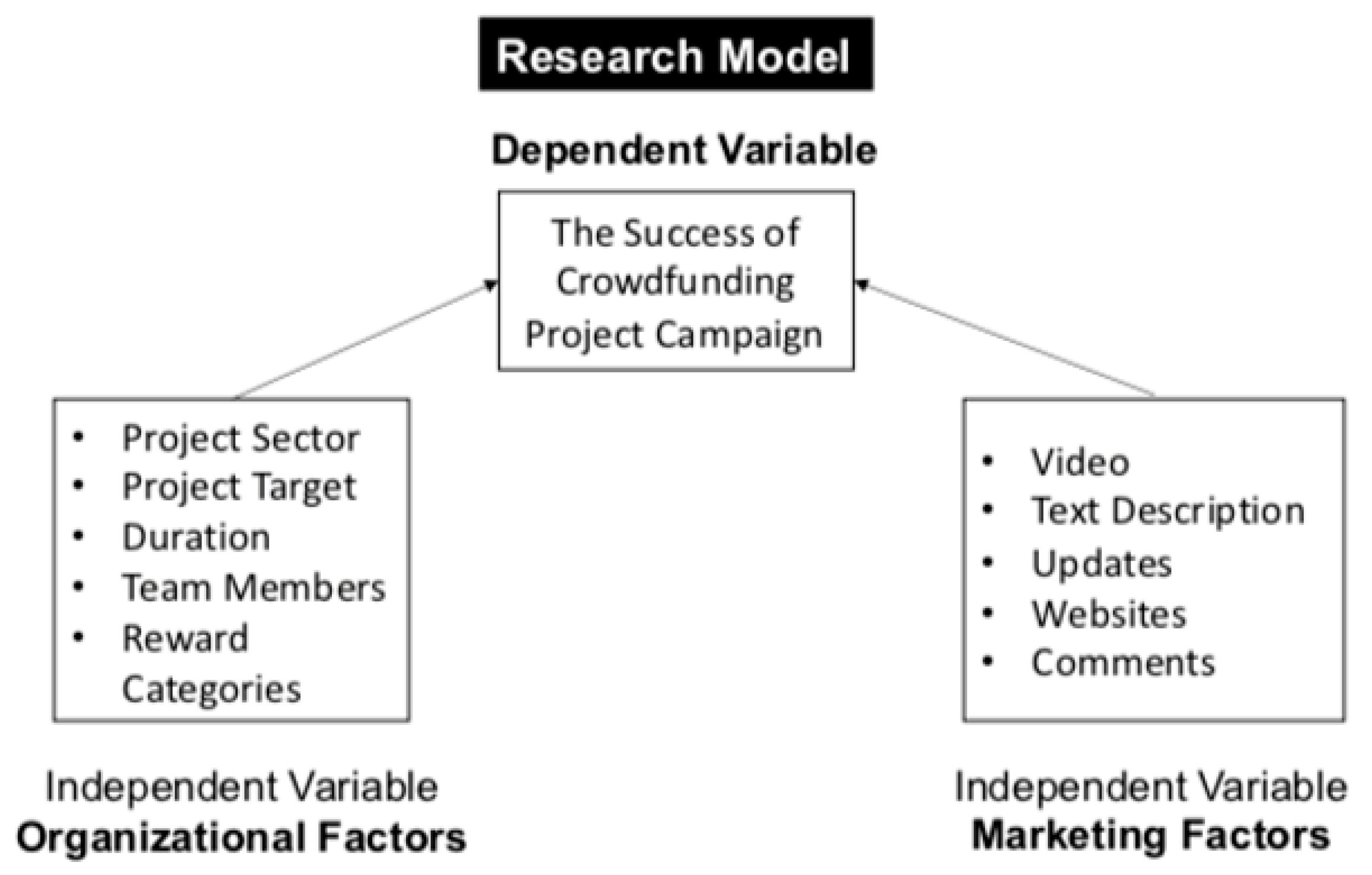

The success of a crowdfunding project campaign can be reflected in the performance of targeted fundraising. When the amount of funds from the crowdfunding project campaign collected successfully exceeds the target amount of funds, the crowdfunding project can be declared successful. The success of a crowdfunding project campaign is influenced by the organizational factors that involve the campaign’s specification and design, and marketing factors that connect the potential backers to the campaign (

Lagazio and Querci 2018).

In the context of reward-based crowdfunding, rewards play an important role as one of the organizational aspects of the crowdfunding campaign for prospective backers to participate in funding (

de Witt 2012;

Nania and Sulung 2019). This paper uses the self-determination theory (

Deci and Ryan 1985) to explain that phenomenon, where someone can behave proactively or even passively towards something because it is influenced by self-motivation. Ryan and Deci divided the two types of motivation: intrinsic motivation that makes a person engage in a behavior that is driven by internal rewards, and extrinsic motivation that makes a person motivated to do something because there are rewards to be achieved (

Ryan and Deci 2000). Wechsler classified both tangible and intangible rewards in reward-based crowdfunding as the extrinsic motivation from the potential backers to participate in the crowdfunding project that can increase the probability of the project’s success (

Wechsler 2013). Besides, this paper also uses appropriate cross-disciplinary literatures such as altruism and warm-glow giving (

Andreoni 1990), resource-based view of firms (

Grant 1991), narrative theories on persuasion and information processing (

Stern 1991), industrial–organizational psychology (

Locke 1968), and signaling theory (

Spence 1973;

Ross 1977) to interpret the multi-sided success factors of crowdfunding campaigns.

This study focuses on ASEAN-5 countries, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapura, Philippines, and Thailand due to their future economic potential (

Putra et al. 2019). In ASEAN-5 countries, crowdfunding is still an emerging market but shows great dynamism and potential upside growth for the next couple of years. Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia already have legal frameworks to support the use of crowdfunding. The emerging potential of crowdfunding in ASEAN-5 countries can also be seen from the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2019 to 2023, projected at 12% (

Statista 2019). In addition, the revenue growth rate (CAGR) of financial technology in the area was recorded at 41% in 2017, greater than the growth rate in the last 3 years at 30% (

EY 2018). From those perspectives, ASEAN-5 countries have considerable space in developing literacy and the use of crowdfunding as an alternative to resolve various issues that affect their financial situation (

Iwasaki 2018). Crowdfunding also can be utilized as a platform to raise external funding for startups and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in ASEAN-5 countries. The SMEs in ASEAN are an integral part of the economic development and growth of countries, where 92–99% of the total business units in ASEAN are in the form of SMEs and employ 58–91% of the domestic workforce and have a contribution rate of exports of 19–31% (

González 2017). In addition, the presence of the ASEAN economic community (AEC) can have a positive impact by generating a level of profit around 5.3% of ASEAN regional income (

Petri et al. 2012) and should be anticipated by the SMEs as the backbone of ASEAN’s economy.

Crowdfunding is needed by SMEs, which are a major part of the ASEAN economy, as an alternative source of funding. Therefore, this study aims to help the project owners in ASEAN, who are small enterprises, in their effort to set up attractive crowdfunding campaigns. Moreover, this study uses several literatures that contribute in theory building to uncover the backer’s decision-making motive to contribute to crowdfunding campaigns.

There are currently few studies that focus on the development of crowdfunding in ASEAN even though countries in ASEAN have shown development in technology literacy and crowdfunding as the alternative source of financing. Moreover, there is still no research that has captured the influence of organizational and marketing factors on crowdfunding campaigns’ success in ASEAN. Therefore, this study attempts to see the multi-sided success factors of crowdfunding campaigns in ASEAN-5 countries, which have a big potential in the future as the contribution of this study.

3. Research Method

The analysis considers hand-collected and cross-section data analysis (

Paudel and Devkota 2018) on reward-based campaigns from ASEAN-5 countries launched on Kickstarter from 2014 to January 2019. This research also used five project categories on Kickstarter that have the biggest number of project proportion, which are design, fashion, film and video, games, and technology. The reasons for selecting the Kickstarter platform is data availability and it is known as the biggest crowdfunding services provider in the world. Moreover, many fund seekers from ASEAN-5 countries prefer international reward-based crowdfunding platforms to raise funds, especially for creative projects. This is because the number of local reward-based crowdfunding is very limited.

The samples in this study is the total population from the five categories campaigns in ASEAN-5 countries launched on Kickstarter from 2014 to January 2019. This is because this study wants to analyze all campaign performance in ASEAN-5 countries. So, in order to solve the outlier data problem (e.g., extreme values of numeric variables), the numeric variables in this study are transformed to log. In detail, the total sample used in this research is 620 projects. The sample numbers of each country are 76, 29, 111, 360, and 44 for Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, and Philippines, respectively. The sample numbers of each category are 205, 99, 91, 114, and 111 for design, fashion, film and videos, games, and technology, respectively. Additionally, we used Stata13 to process the data.

This study used the probit model to analyze how each explanatory variable affects the probability of success of the crowdfunding project campaign. Mathematically, the model can be represented as follows:

where Pr is the probability; Φ is the cumulative standard normal probability distribution; Yι is dependent variable which is the dummy variable that marks out successful and unsuccessful project; Xι is the explanatory variables; and Φ is estimated by maximum likelihood.

According to

Figure 1, the dependent variable, which is successful, occurs if the project owner raises at least the same amount as the target funding. This variable is dummy, where “1” is assigned when the funding at least meets the target and “0” when the funding is less than the target. The organizational variables are measured by several proxies, such as, the sector that shows the field of the project (social vs. non-social); project target that shows the amount of money requested by the project owner in USD; duration that shows the number of days for which a project accepts funding team members, the number of individuals working on the project, and rewards that show the number of reward categories offered by the fundraisers. The marketing variables are also measured by several proxies, such as, video that shows the presence of a pitch video in campaign; text description that shows the number of words used in project description; updates that show whether the project owner keeps the backers informed on the progress; comments that show the existence of comments on the campaign; and websites that show the presence of links to external websites that contain the comprehensive information on the project.

Table 1 shows the definition of operationalization variables.

4. Findings and Discussion

Table 2 shows that the average funding target for the 620 crowdfunding campaign was

$24,741 US. For variable duration projects, the Kickstarter platform allows project campaign activities to be carried out within a span of 1 to 60 days. The average duration of the project campaign is 33.56 days. Then, the number of team members involved in the project has an average value of 3 people per team. This indicates that most projects in ASEAN-5 countries are still run by small teams, not by large teams. On average there are 8 prize categories offered by project owners to potential backers for their financial contributions. Finally, all project owners write project descriptions on the Kickstarter platform with the highest number of word descriptions in the project being 964 words. Then, the success rate of the project campaign achieved was 48.87%, or 303 project campaigns that managed to get 100% funding or more (see

Table 3). This indicates that there are still many campaigns in ASEAN-5 countries that have not succeeded. The majority of projects with a proportion of 82.58% have non-social goals. As much as 84.35% of project campaigns on the Kickstarter platform include an introductory pitching video on the project campaign page. Then, 70.65% of project owners provide the latest information regarding the project on the update feature on the Kickstarter platform page. Furthermore, 64.52% of the comment column on the project campaign page is filled with comments from both the project owner and prospective backers. Finally, 77.10% of project campaigns on the Kickstarter platform provide external website links.

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the results of a goodness of fit test for the model of this study.

Table 4 shows that the Pearson Chi-square of this research model is 598.73 with a probability of 0.6090. When the probability value is greater than 0.05, it indicates that the model is an already good fit (

Hosmer and Lemeshow 2013). In addition, when there is a difference between the frequency of data observed and those predicted in the research model, the research model is not yet a good fit (

Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000). In this study there is no difference between the frequency of data (N) and the value of the covariate pattern so that this research model has a good fit.

Table 5 shows the Hosmer–Lemesow Chi-square model of this study is worth 10.41 with a probability of 0.2374. So, it can be concluded, that based on the Hosmer–Lemeshow test this research model is feasible to use.

Table 6 shows the results of probit regression models that identify both organizational and marketing aspects that affect the success of crowdfunding campaigns. Regarding organizational aspects, the pro-social initiative does not significantly affect the success of reward-based crowdfunding campaigns, which is not in line with H1a. These results do not automatically refute the theory of warm glow giving, which states that a person has an altruism side and feels satisfied when helping others. Paschen suggested that project owners who have pro-social projects use donation-based crowdfunding such as StartSomeGood to raise funds for projects that contribute to social empowerment (

Paschen 2017). In the context of crowdfunding platforms in Southeast Asia, many pro-social projects have received funding, such as the platform of Kitabisa.com in Indonesia. Lagazio and Querci also stated that endorsement by public institutions and government can boost the pro-social crowdfunding project fundraising performance (

Lagazio and Querci 2018). Meanwhile, the support from public institutions for crowdfunding is very limited (especially in Indonesia and Philippines where there is not a special legal framework for crowdfunding) where the use of traditional media in fundraising for social projects is still more popular in ASEAN-5 countries. So, that may also be the reason that pro-social initiatives do not significantly affect the success of reward-based crowdfunding campaigns.

Based on the table of results, our results are different from other previous results, which indicates a positive relationship between target funding and crowdfunding success. The funding target from our sample negatively influences the crowdfunding success which means that the greater the funding target of projects, the lower rate of crowdfunding campaign success. This is because our sample uses projects from ASEAN countries whose owners or investors are concerned more with being risk averse than being risk takers. This indicates that a high funding target might indicate the high level of risk embedded in that project and thus decreases the trust of potential funders in the project campaign. This is also in line with the goal setting theory which states that when the project funding target is set very high, the element of rationality of the target will decrease and this will consequently, at the same time, demonstrate that the target is beyond the reach of potential funders. In line with the literature on the goal setting theory, the higher the amount targeted, the lower the rate of probability of the campaign to meet the target (H1b). Lagazio and Querci stated that prospective backers are very concerned with the possibility that the projects can run effectively so that the rationality factor in determining funding targets must be considered by the project owner (

Lagazio and Querci 2018). According to

Table 7, this funding target varies in the 5-ASEAN countries, of which the highest and lowest of funding target countries are Singapore (

$14,290) and Indonesia (

$373), respectively.

Campaign duration does not have a significant effect on the success of crowdfunding campaigns, which is not in line with H1c. This result is supported by Wati and Winarno who found that the fundraising period does not significantly affect the success of crowdfunding campaigns (

Wati and Winarno 2018). Periods of time that are too long can be considered annoying because it is difficult to focus on achieving its goals at the right time (

Lunenburg 2011). On the other hand, Lagazio and Querci found that potential backers appreciate longer periods of time to understand the project’s specifications (

Lagazio and Querci 2018). Thus, whether the duration of the campaign is long or not has no significant effect on the success of the campaign.

In line with the literature on the resource-based view, the more individuals working on the team, the higher rate of probability of the campaign meeting the target (H1d). The results are also in line with Lagazio and Querci, who found that the more team members involved in project execution, the greater the chance of crowdfunding project campaigns will achieve success (

Lagazio and Querci 2018). This is very influential on the performance of crowdfunding projects where, with the increasing number of team members, the workload can be efficiently divided and the team can give the best effort to meet the backers’ expectation (e.g., project owners can give more updates, answer every backers’ question). Having more group members in a project, the specialization of the group job can be built and thus provides specific information to the targeted members. In addition, it also helps project owners to build stronger relationships and interactions with potential funders. Therefore, crowdfunding projects can be run more efficiently with effective results.

To distinguish our paper from others, we also fill in the reward variable of the organizational factors as an independent variable. Therefore, based on the table of results, we found that the more reward categories offered, the higher rate of probability of the campaign to fulfill the fundraising target (H1e). The results are also in line with the self-determination theory where reward as an extrinsic motivation can stimulate the potential backers to financial contribute to the project. Each reward has a category level based on the amount of funds provided by the funder. Therefore, in terms of ASEAN projects, potential backers should be provided with many options of rewards to motivate them to fund prospective projects. This is because the greater the amount of funds provided to backers, the more benefits of rewards will be received by the funders. The project owner must be able to provide many options to the prize category level that is in accordance with the motivation and ability of the funder to contribute financially to the project. Therefore, project campaigns that can provide a greater range of prize categories have a higher success rate campaigns (

Kuppuswamy and Bayus 2014;

Hobbs et al. 2016). Hobbs et al. stated that at high reward levels, project owners offer tangible rewards such as products at lower prices, while at low reward levels, project owners offer intangible rewards such as recognition in several forms. Thus, as the project owner can provide many choices and variations in the level of prize categories in both intangible and tangible forms, prizes in return will become a motivation for potential funder to contribute more according to their capabilities.

Regarding marketing aspects, the presence of a video does not significantly affect the success of campaign, which is not in line with H2a. Lagazio and Querci stated that the presence of videos in crowdfunding project campaigns is not automatically able to increase persuasion of potential backers (

Lagazio and Querci 2018). Also, Kickstarter suggests that project owners include a pitching video to attract backers. So, the existence of the video is a must in this era. Then, the quality and/or length of the video may be more significant in persuading potential backers.

The number of words on the project description does not significantly affect the success of the campaign either, which is not in line with H2b. In this era of high mobility, Han et al. stated that people have no time to read a very long text description (

Han et al. 2018). They also found that a longer description is likely to decrease the clarity of the message and the quality of the argument. So, very detailed text description of the project campaign does not play a significant role anymore to persuade potential backers. Stern also suggested that several supporting media should be used to maximize the persuasion and information process such as photos, graphs, or sound clips (

Stern 1991).

The presence of updates positively affects the success of the campaign, which is in line with H2c. As the signaling theory states, the project owner should give a signal to the potential backers to minimize the information asymmetry (

Ross 1977;

Bergh et al. 2010). The results of this study are also in line with the theory of signaling where companies must provide information that signals the quality of the company to reduce information asymmetry between the company and potential funders. Furthermore, information asymmetries can increase when stakeholders, including potential investors, cannot find the company’s information easily (

Stiglitz 2002) and thus the company must actively communicate every detail of progress to potential investors. In the context of crowdfunding and according to the results, the project owner should actively provide the latest information about the project, which is the best way for the project owner to communicate to potential funders. In addition, an update can significantly play a role as a signal related to the quality of the project to potential funders so that they can evaluate project progress critically and comprehensively

In line with the signaling theory, the presence of external website links positively affects the success of the campaign (H2d). Lagazio and Querci stated that the presence of external website links in crowdfunding project campaigns can increase the success of crowdfunding project campaigns (

Lagazio and Querci 2018). This is a positive signal given by the project owner to potential funders, that they have put extensive effort to bring transparency to potential funders and at the same time provide comprehensive information related to the project. With the provision of the external website link, potential funders can access a variety of more detailed and comprehensive project-related information aside from the official crowdfunding platform. Thus, the presence of an external website link, such as social media Facebook and LinkedIn, can improve the process of evaluating information related to project campaigns by potential funders in another critical and comprehensive way. Through this approach, potential funders will increasingly make investment decisions on the project providing more transparent and reliable information.

Finally, the presence of comments increases the success of the campaign (H2e). Kim et al. stated that in the comment feature of crowdfunding project campaigns, prospective backers can find various additional information, this is clear and comprehensive, related to projects, which reduces information gaps between project owners and potential backers (

Kim et al. 2017). The comments variable can be defined as an electronic word-of-mouth, describing project reviews online in both positive and negative terms. When a potential funder feels confident and satisfied with a project, the individual will give a positive review about the project, and vice versa if the prospective funder is doubtful and dissatisfied with a project, the individual will give a negative review of the project in the comment column. Therefore, this comments feature implies that the project owner offers clear and comprehensive information related to the project, which will reduce information gaps between project owners and potential funders. That way the presence of comments in the platform can increase the confidence and interest of potential funders to invest in the project and at the same time increase the probability of success of the crowdfunding project campaign.

The marginal effects represent the change in the probability when the variable of interest increases by one unit. Then, in the case of the log-transformed variables, we multiply the corresponding value by 0.1, as the baseline to obtain the changing probability of the variable of interest increases by 10%. So, any increase in funding target of 10% will decrease the probability of project campaign success by 1.4 percentage points. Each increase in the number of reward categories by 10% will increase the probability of the success of the project campaign by 1.3 percentage points. Each increase in the number of team members by 10% will increase the probability of project campaign success by 0.9 percentage points.

Moreover, we also use several dummy variables to explain the multi-faceted factors on success of the crowdfunding campaign. Therefore, we use the odds ratio in order to understand and interpret the relationship between the success in the crowdfunding campaign and independent variables which are in categorical or dummy format. The following are the interpretations for the categorical independent variables’ odds ratio: First, the presence of comments in the project campaign will increase the probability of project campaign success by 2225 times the initial probability. Then, the presence of updates in the project campaign will increase the probability of project campaign success by 4239 times from the initial probability. Finally, the presence of external website links will increase the probability of success of the project campaign by 1,876 times the initial probability.

5. Conclusions

Both organizational and marketing factors play an important role on the success of crowdfunding project campaigns. According to organizational factors, the pro-social initiative does not have a significant effect in the success of reward-based campaigns where it can be more relevant in donation-based crowdfunding. After that, the higher the amount of fundraising targeted, the lower rate of probability of the campaign to meet the target. This is because we use projects from ASEAN countries whose owners or investors are more concern with being risk averse than being risk takers. The increasing number of team members makes the workload of the project more efficiently divided. In addition, to distinguish with previous literatures, we added the reward variable to the organizational categories which shows that the more reward categories offered, the higher rate of probability of the campaign to fulfill the fundraising target. Therefore, potential backers for ASEAN projects should be provided with many options of rewards to motivate them to fund prospective projects.

As expected, the presence of updates plays a significant role as a signal to provide the latest information and progress of the project. Potential backers also appreciate the project owner that puts an external website link as a good intention to provide transparency and comprehensive information. Finally, comments can be used to interact with potential backers by actively answering their questions and accommodating advices.

This study also offers added-value to include crowdfunding projects in ASEAN-5 countries which are rarely covered by most researchers.

Table 2 shows that 51% of crowdfunding campaigns in ASEAN-5 countries are not successful. This might occur due to the lack of studies that focus on exploring the organizational and marketing factors that should be considered and utilized by project owners to attract potential backers. Therefore, this research can be used as a reliable resource for every stakeholder to be able to maximize every economic potential in ASEAN-5 countries through crowdfunding in the future.

Gaining research implication, project owners or initiators are able to observe the organizational and marketing factors that will improve the performance of fundraising. They may decrease the fundraising target, hire more people, add more reward categories, frequently give updates, provide the website of the project, and actively interact with potential backers through the comment sections. For the backers’ implication, they are able to evaluate the projects by looking at the funding target, number of team members, number of rewards offered, and the presence of updates, comments, and also external website links.