‘No, I Don’t Like the Basque Language.’ Considering the Role of Cultural Capital within Boundary-Work in Basque Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Education System Structure and Distribution of Studentship

2.2. Conceptualizing Boundary-Work, Intergroup Contact Theory, and Social Identity

3. Setting and Methods

3.1. The Basque Country and Basque Education System

3.2. Methods

- General distribution of students: It refers to the criteria guiding how students were distributed. Two main elements were taken into account:

- ○

- Distribution of students recommended by teachers and chosen by students in 2G and their families.

- ○

- 2nd CSE students’ spatial distribution during recess.

- Academic interactions during Basque language lessons in 2G: It refers to peer interactions involving affinity, friendship, and language learning. It also includes student to teacher interactions when learning Basque. I chose Basque lessons as these immigrant students showed a high level of interaction both with other students and teachers. The elements taken into account were:

- ○

- The lower-level Basque lesson.

- ○

- The higher-level Basque lesson.

- ○

- Students who disliked Basque.

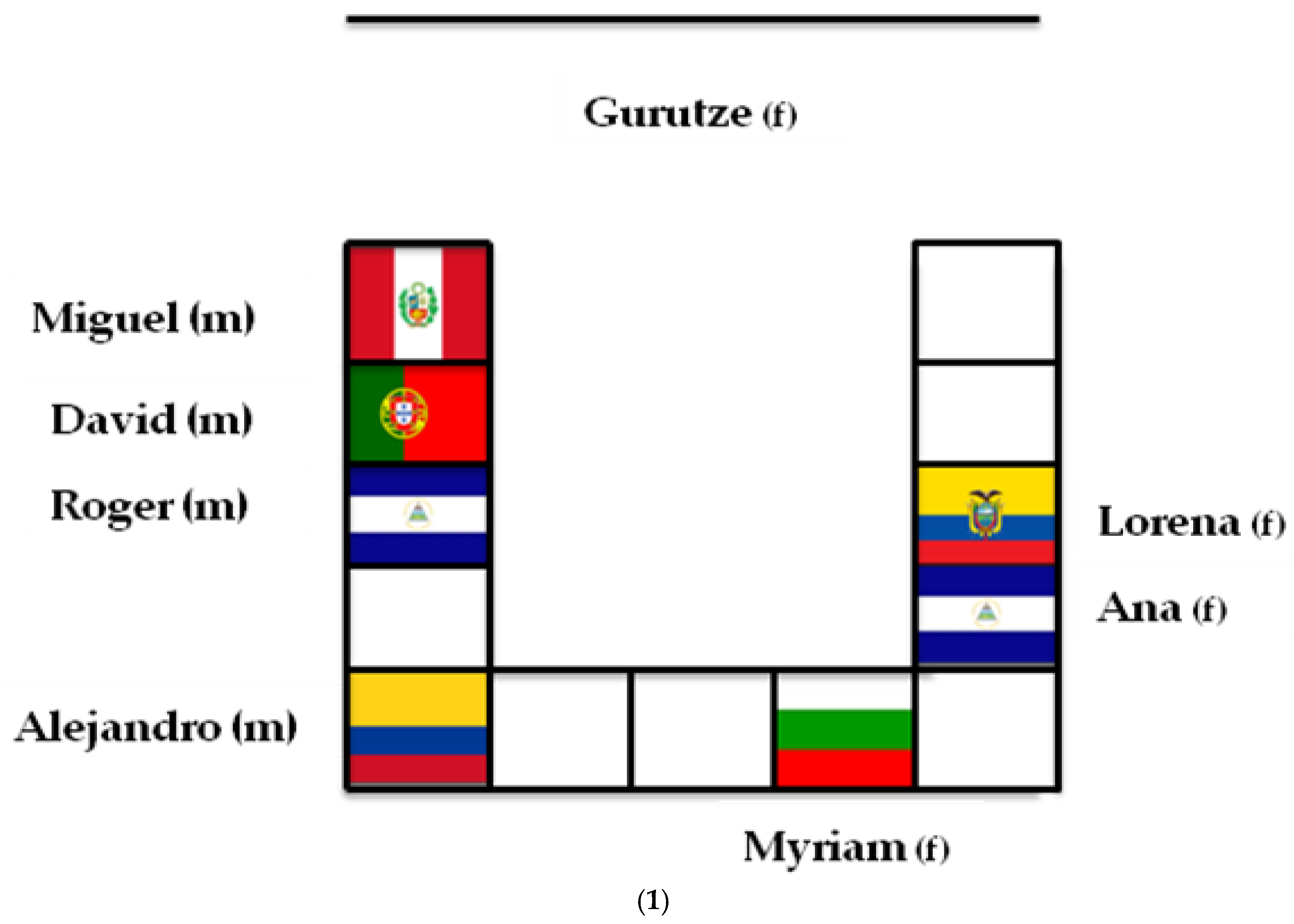

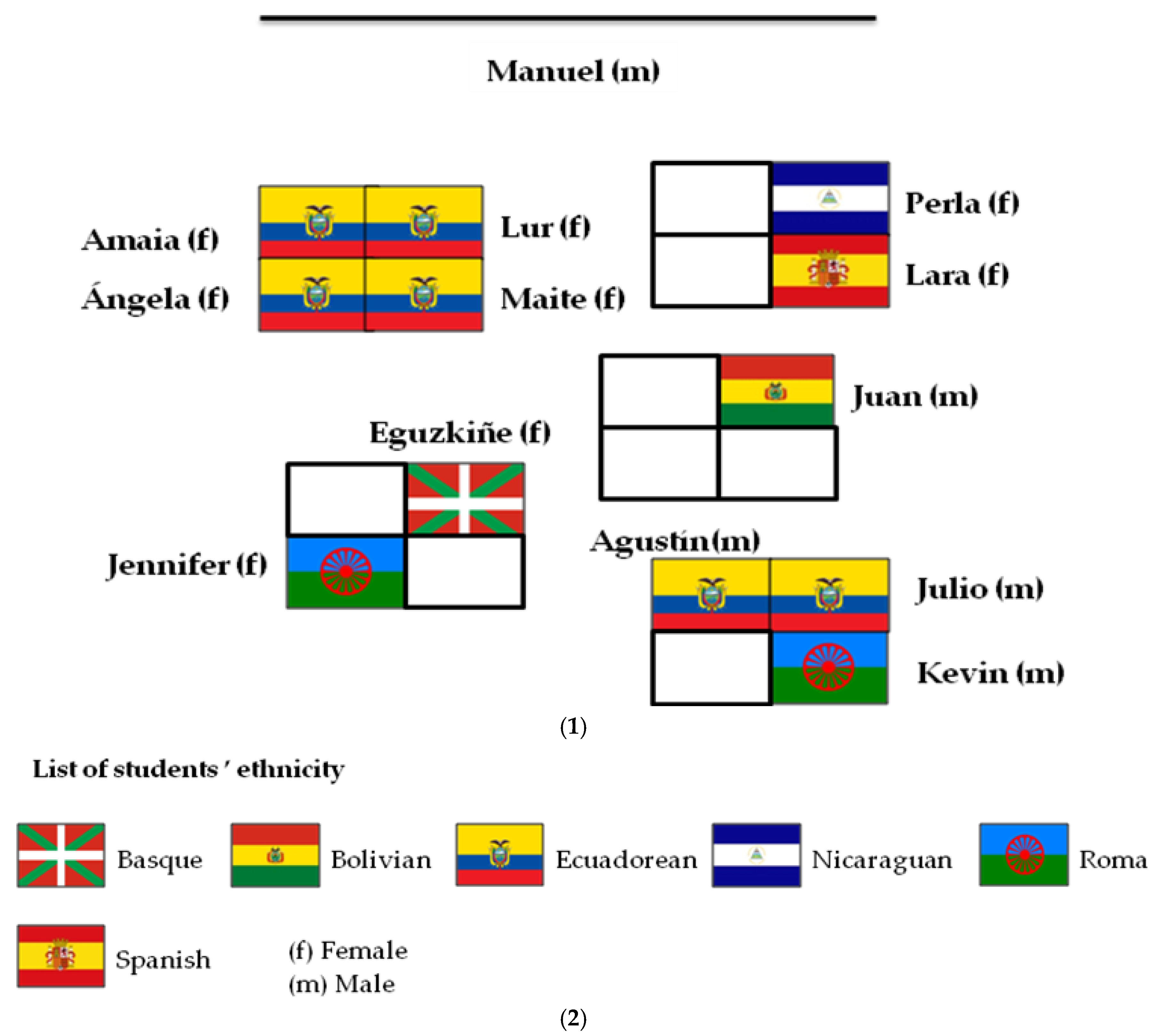

3.3. Sample

4. Results

4.1. General Distribution of Students

4.1.1. Distribution of Students Recommended by Teachers and Chosen by 2G Students and Their Families

4.1.2. 2nd CSE Students’ Spatial Distribution during Recess

4.2. Academic Interactions during Basque Lessons in 2G

4.2.1. The Lower-Level Basque Lesson

4.2.2. The Higher-Level Basque Lesson

4.2.3. Students Who Disliked Basque

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baquedano-López, Patricia, Anne R. Alexander, and Sera J. Hernández. 2013. Equity Issues in Parental and Community Involvement in Schools: What Teacher Educators Need to Know. Review of Research in Education 37: 149–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, Frederik. 1976. Los Grupos Étnicos y sus Fronteras. La Organización Social de las Diferencias Culturales. México D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian, Brock, Dean Lusher, and Abe Ata. 2012. Contact, evaluation and social distance: Differentiating majority and minority effects. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36: 100–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Päivi. 2010. Shifting Positions in Physical Education—Notes on Otherness, Sameness, Absence and Presence. Ethnography and Education 5: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boda, Zsófia, and Bálint Néray. 2015. Inter-ethnic Friendship and Negative Ties in Secondary School. Social Networks 42: 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Oxford: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2008a. Capital Cultural, Escuela y Espacio Social. Argentina: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2008b. Qué Significa Hablar. Economía de los Intercambios Lingüísticos. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1973. Los Estudiantes y la Cultura. Buenos Aires: Labor. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1981. La Reproducción. Elementos para una Teoría del Sistema de Enseñanza. Barcelona: Laia. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Roger. 2014. Beyond Ethnicity. Ethnic and Racial Studies Symposium 37: 804–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, Erin A. 2017. What fosters concern for inequality among American adolescents? Social Science Research 61: 160–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Convertino, Christina. 2015. Misfits and the Imagined American High School: A Spatial Analysis of Student Identities and Schooling. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 46: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. 2016. II Plan de Atención Educativa al Alumnado Inmigrante en el Marco de la Escuela Inclusiva e Intercultural 2016–2020; Vitoria-Gasteiz: Basque Government.

- Dewalt, Kathleen M., Billie B. Dewalt, and Coral B. Wayland. 2011. Participant observation. In Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Edited by Kathleen M. Dewalt and Billie B. Dewalt. Maryland: AltaMira Press, pp. 259–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, Radosveta, Deborah Johnson, and Fons Van de Vijver. 2017. Ethnic Socialization, Ethnic Identity, Life Satisfaction and School Achievement of Roma Ethnic Minority Youth. Journal of Adolescence 62: 175–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubet, François. 2010. Sociología de la Experiencia. Madrid: Editorial Complutense. [Google Scholar]

- Dubet, François, and Danilo Martuccelli. 1997. En la Escuela. Sociología de la Experiencia Escolar. Madrid: Losada. [Google Scholar]

- Dumais, Susan A. 2005. Children’s Cultural Capital and Teacher’s Assessment of Effort and Ability: The Influence of School Sector. Catholic Education: A Journal for Inquiry and Practice 8: 418–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dumais, Susan A., and Aaryn Ward. 2010. Cultural Capital and First-generation College Success. Poetics 38: 245–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrheim, Kevin, Xoliswa Mtose, and Lyndsay Brown. 2011. Race Trouble: Race, Identity and Inequality in Post-Apartheid South Africa. New York: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria, Begoña. 2003. Schooling, Language and Ethnic Identity in the Basque Autonomous Community. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 34: 351–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2002. Constructing Meaning in Sociolinguistic Variation. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, New Orleans, LA, USA, November 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, Penelope. 2004. Adolescent language. In Language in the USA: Themes for the Twenty-First Century. Edited by Edward Finegan, Charles Albert Ferguson, Shirley Brice Heath and John R. Rickford. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- EFE. 2016. Uriarte Reconoce que la Segregación Escolar ‘no es Baladí’ y Anuncia Medidas. Diario Vasco. February 19. Available online: http://www.diariovasco.com/sociedad/201602/19/uriarte-reconoce-segregacion-escolar-20160219115154.html (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- EHIGE Gurasoen Elkartea. 2016. Hezkuntza-Sistema Inkulsiboa Lortzeko Proposamenak. Bilbao: EHIGE Gurasoen Elkartea, Available online: http://www.ehige.eus/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/RP-Hezkuntza-sistema-inklusiboa-Sistema-educativo-inclusivo.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2016).

- Erikson, Erik. 1989. Identidad, Juventud y Crisis. Madrid: Taurus. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik. 2000. El Ciclo Vital Completado. Buenos Aires: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria, Félix, and Kristina Elosegi. 2008. Basque, Spanish and Immigrant Minority Languages in Basque Schools. Language, Culture and Curriculum 21: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, Félix, and Kristina Elosegi. 2010. Integración del Alumnado Inmigrante: Obstáculos y Propuestas. Revista Española De Educación Comparada 16: 235–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de Arangiz, Saioa. 2016. Hezkuntzaren Jarrera Gogor Kritikatu du Eskola Publikoaren Aldeko Plataformak. Argia. February 21. Available online: http://www.argia.eus/albistea/hezkuntzaren-jarrera-gogor-kritikatu-du-eskola-publikoaren-aldeko-plataformak (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- Fernández Vallejo, Marta. 2016. Inmigrantes, la Mochila de la Escuela Vasca. El Correo. March 16. Available online: http://www.elcorreo.com/bizkaia/sociedad/educacion/201603/06/inmigrantes-mochila-escuela-vasca-20160306170144.html (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- Foley, Douglas. 2010. The Rise of Class Culture Theory in Educational Anthropology. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 41: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goikoetxea, Garikoitz. 2016. Neurriak Eskatu dituzte Etorkinak Eskola Publikoetan ez daitezen Pilatu. Berria. February 16. Available online: https://www.berria.eus/paperekoa/1851/008/001/2016-02-16/neurriak_eskatu_dituzte_etorkinak_eskola_publikoan_ez_daitezen_pilatu.htm (accessed on 10 April 2016).

- González, Norma. 2010. The End/s of Anthropology and Education: 2009 CAE Presidential Address. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 41: 121–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irena, Loudova, Katarina Prikrylova, Eva Kudrnova, and Adam Trejbal. 2016. What do Pupils Laugh at? Content Analysis of Jokes. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research, Singapore, July 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, Michelle M. 2017. Indigenous Studies Speaks to American Sociology: The Need for Individual and Social Transformations of Indigenous Education in the USA. Social Sciences 7: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe-Walter, Reva, and Stacy J. Lee. 2011. To Trust in my Root and to Take that to go Forward: Supporting College Access for Immigrant Youth in the Global City. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 42: 281–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmaat, Jan G. 2015. School Ethnic Diversity and White Students’ Civic Attitudes in England. Social Science Research 49: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, Richard. 1982. Pierre Bourdieu and the Reproduction of Determinism. Sociology 16: 270–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Richard. 1992. Pierre Bourdieu. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Richard. 2008. Social Identity. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kanas, Agnieszka, Peer Scheepers, and Carl Sterkens. 2017. Positive and Negative Contact and Attitudes towards the Religious Out-group: Testing the Contact Hypothesis in Conflict and Non-conflict Regions of Indonesia and the Philippines. Social Science Research 63: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, Anthony. 2000. Thinking with Bourdieu against Bourdieu: A ‘Practical’ Critique of the Habitus. Sociological Theory 18: 417–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisida, Brian, Jay P. Greene, and Daniel H. Bowen. 2014. Creating Cultural Consumers: The Dynamics of Cultural Capital Acquisition. Sociology of Education 87: 281–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koefoed, Lasse, and Kristen Simonsen. 2012. (Re)scaling Identities: Embodied Others and Alternative Spaces of Identification. Ethnicities 12: 623–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, Michèle, and Virag Molnár. 2002. The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareau, Annette. 2011. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race and Family Life. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, Annette. 2015. Cultural Knowledge and Social Inequality. American Sociological Association 80: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareau, Annette, Shani A. Evans, and April Yee. 2016. The Rules of the Game and the Uncertain Transmission of Advantage. Sociology of Education 89: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, Francisco. 2014. Evaluación de Diagnóstico 2013. Resultados del Alumnado Inmigrante en Euskadi. Bilbao: Instituto Vasco de Evaluación e Investigación Educativa. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Stefan. 2015. School Dhoice, Ethnic Divisions and Symbolic Boundaries. New York: Palgrave McMillian. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Rojo, Luisa. 2010. Critical Sociolinguistic Ethnography in Schools. In Constructing Inequality in Multilingual Classrooms. Edited by Luisa Martín Rojo. Götingen: DeGruyter, pp. 51–92. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Rojo, Luisa. 2011. Discourse and Schools. In The SAGE Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Edited by Ruth Wodak, Barbara Johnstone and Paul Kerswill. London: SAGE, pp. 345–60. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, María. 2014. La Educación de los Otros: Gestión de la Diversidad y Políticas Interculturales en la Escuela Inclusiva Básica. In De la Identidad a la Vulnerabilidad. Alteridad e Integración en el País Vasco Contemporáneo. Edited by Ignacio Irazuzta and María Martínez. Barcelona: Edicions Bellaterra, pp. 70–111. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Ramón A., and P. Zitlali Morales. 2014. ¿Puras Groserías? Rethinking the Role of Profanity and Graphic Humor in Latino Students’ Wordplay. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 45: 337–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvasti, Amir Barzegar. 2010. Interviews and Interviewing. In International Encyclopedia of Education. Edited by Eva Baker, Penelope Peterson and Barry McGaw. London: Elsevier Science, pp. 424–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, Geroge Herbert. 1982. Espíritu, Persona y Sociedad Desde el Punto de Vista del Conductismo Social. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Merolla, David, and Omari Jackson. 2014. Understanding Differences in College Enrolment: Race, Class and Cultural Capital. Race and Social Problems 6: 280–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulyuk, Ashley B., and Jomills H. Braddock. 2018. K-12 School Diversity and Social Cohesion: Evidence in Support of a Compelling State Interest. Education and Urban Society 50: 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskal, Marta. 2016. Language and Cultural Capital in School Experience of Polish Children in Scotland. Race Ethnicity and Education 19: 141–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munniksma, Anke, Maykel Verkuyten, Andreas Flache, Tobias Stark, and René Veenstra. 2015. Friendships and Outgroup Attitudes Among Ethnic Minority Youth: The Mediating Role of Ethnic and Host Society Identification. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 44: 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, Ainhoa. 2015. La Concentración de Inmigrantes en la Escuela Pública se Acentúa en Euskadi. Diario Vasco. June 21. Available online: http://www.diariovasco.com/sociedad/educacion/201506/21/concentracion-inmigrantes-escuela-publica-201506210759.html (accessed on 25 June 2015).

- Nawyn, Stephanie, Linda Gjokaj, DeBrenna LaFa Agbényiga, and Breanne Grace. 2012. Linguistic Isolation, Social Capital, and Immigrant Belonging. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 41: 255–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez Paz, Carlos. 2012. La Escuela, un Espacio Simbólico que Construir: Estigmas y Estrategias de los Agentes en los Procesos de Segregación Étnica y Escolarización. In Segregaciones y Construcción de la Diferencia en la Escuela. Edited by Javier García Castaño and Antonia Olmos Alcaraz. Madrid: Trotta, pp. 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Izaguirre, Elizabeth. 2015. When the Others Come to School: A Marginalization Framework in Multicultural Education. Sociology Compass 10: 887–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F. 2008. Future Directions for Intergroup Contact Theory and Research. Intercultural Journal of Intercultural Relations 32: 187–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., Linda R. Tropp, Ulrich Wagner, and Oliver Christ. 2011. Recent Advances in Intergroup Contact Theory. Intercultural Journal of Intercultural Relations 35: 271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, Diane, Gill Crozier, and John Clayton. 2010. ‘Fitting In’ or ‘Standing Out’: Working-Class Students in UK Higher Education. British Educational Research Journal 36: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children. 2016. Necesita Mejorar. Por un Sistema Educativo que no Deje Nadie Atrás. Anexo Euskadi. Published Online: Save the Children España. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/sites/default/files/imce/docs/necesita_mejorar_veusk_cas_web.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2018).

- Schellhaas, Fabian M. H., and John F. Dovidio. 2016. Improving Intergroup Relations. Current Opinion in Psychology 11: 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septien, Jesús Manuel. 2006. Una Escuela sin Fronteras. La Enseñanza del Alumnado Inmigrante en Álava. Vitoria-Gazteiz: Ararteko. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, Charlana, Cameron Lewis, and Joanne Larson. 2011. Narrating Identities: Schools as Touchstones of Endemic Marginalization. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 42: 121–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Miri. 2014. Raising the Bar in Analysis: Wimmer’s Ethnic Boundary Making. Ethnic and Racial Studies 37: 829–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotillo, Beatriz. 2016. Educación Quiere Equilibrar el Número de Alumnos Inmigrantes y Autóctonos. Deia. January 23. Available online: http://www.deia.eus/2016/01/23/sociedad/euskadi/educacion-quiere-equilibrar-el-numero-de-alumnos-inmigrantes-y-autoctonos (accessed on 15 April 2016).

- Spradley, James L. 1980. Participant Observation. Long Grove: Waveland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Sandra. 2004. The Culture of Education Policy. New York: Teachers Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sterzuk, Andrea. 2015. ‘The Standard Remains the Same’: Language Standardisation, Race and Othering in Higher Education. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 36: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, Robin, and Sheldon Stryker. 2016. “Does Mead’s Framework Remain Sound?”. In New Directions in Identity Theory and Research. Edited by Jan E. Stets and Richard Serpe. Oxford: Online, pp. 31–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tabib-Calif, Yosepha, and Edna Lomsky-Feder. 2014. Symbolic Boundary Work in Schools: Demarcating and Denying Ethnic Boundaries. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 45: 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijs, Jochem. 2017. Children’s Evaluations of Interethnic Exclusion: The Effects of Ethnic Boundaries, Respondent Ethnicity, and Majority In-group Bias. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 158: 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredoux, Colin, John Dixon, Kevin Durrheim, and Buhle Zuma. 2017. Interracial Contact among University and School Youth in Post-Apartheid South Africa. In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents. Edited by Adam Rutland, Drew Nesdale and Christia S. Brown. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praag, Lore, Peter A. Stevens, and Mieke Van Houtte. 2015. Defining Success in Education: Exploring the Frames of Reference Used by Different Voluntary Migrant Groups in Belgium. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 49: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervoort, Miranda H. M., Ron H. J. Scholte, and Peer L.H. Scheepers. 2011. Ethnic composition of school classes, majority–minority friendships, and adolescents’ intergroup attitudes in the Netherlands. Journal of Adolescence 34: 257–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, Jean-Jacques. 2009. Multilingualism, Education and Change. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2008. The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory. American Journal of Sociology 113: 970–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yosso, Tara J. 2005. Whose Culture has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education 8: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, Bulhe, and Kevin Durrheim. 2012. The state of the ‘rainbow nation’: childhood prejudice reduction and multicultural education. In Contextualising Community Psychology in South Africa. Edited by Martha Visser. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In this paper I will use the terms multiethnic, intraethnic and interethnic. Multiethnic makes reference to the presence of individuals or groups from diverse ethnic backgrounds, regardless of their interactions. Intraethnic refers to the interaction between members of the same ethnic background, and interethnic involves the interaction among members of various ethnic backgrounds. |

| 2 | Wimmer (2008, 2013) uses the term ‘Them’ instead of ‘Others’ in his work. However, I chose to use the designation ‘Others’ to refer to the extensively researched ‘Us/Others’ binary, in line with most authors in the social sciences (Berg 2010; Simmons et al. 2011; Koefoed and Simonsen 2012; Sterzuk 2015). |

| 3 | Anonymity and confidentiality of the research participants and their personal information are guaranteed at all times; hence, all the names used throughout this article are pseudonyms. |

| 4 | Please note that although officially a Spanish student is not an immigrant in the BAC, his/her mother language is usually Spanish. In that sense, his/her linguistic situation is similar to that of a Latino student when he/she arrives in the BAC. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-Izaguirre, E. ‘No, I Don’t Like the Basque Language.’ Considering the Role of Cultural Capital within Boundary-Work in Basque Education. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090150

Pérez-Izaguirre E. ‘No, I Don’t Like the Basque Language.’ Considering the Role of Cultural Capital within Boundary-Work in Basque Education. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(9):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090150

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-Izaguirre, Elizabeth. 2018. "‘No, I Don’t Like the Basque Language.’ Considering the Role of Cultural Capital within Boundary-Work in Basque Education" Social Sciences 7, no. 9: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090150

APA StylePérez-Izaguirre, E. (2018). ‘No, I Don’t Like the Basque Language.’ Considering the Role of Cultural Capital within Boundary-Work in Basque Education. Social Sciences, 7(9), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090150