1. Introduction

Climate changes are reshaping agricultural production and food security across the globe (

IPCC 2014b), leading to increased uncertainty (

Torquebiau et al. 2015), changing production processes (

Bryant et al. 2016), greater levels of outmigration from rural areas for alternative income (

Alston 2015), and a reshaped agricultural workforce (

Preibisch and Grez 2010). As these impacts take hold, significant gendered workforce realignments are underway in agricultural production units. One result evident across the world is that women are having a much greater role in food production and now comprise 43% of the global agricultural workforce (

World Bank 2012;

FAO 2013;

World Bank 2017), over 50% in many Asian nations, and over 40% in southern Africa (

FAO 2010;

World Bank 2017). Nonetheless, there is far less documented information on women’s contribution to agriculture in developed countries and almost no systematic data collection in Australia. This is despite the fact that 99% of the 134,000 Australian farms are run as family farms (

National Farmers’ Federation 2012), confirming that Australian agriculture is highly dependent on the labour flexibility female and male family members provide.

Yet, developed world agricultural industries operate in a policy, media, and industry environment that is hegemonically masculine (

Knuttila 2016) and that rarely acknowledges the significance of women’s input to successful farm production. Consequently, although women’s work is acknowledged as crucial in the private family sphere (

Alston and Whittenbury 2014), women have struggled for public recognition of their contributions and may feel powerless to shape their own destiny. Consequently, when radical changes such as climate events occur, forcing significant adjustments to agricultural production processes and major gender renegotiations around workloads, women and men enter these negotiations from vastly different power positions (

Shortall 2006). Thus, while documenting agricultural work by gender in developed countries is long overdue, documenting the adjustments resulting from climate-induced environmental events would seem critical.

To examine how women’s labour on farms is being reshaped in the context of both climate changes and a historical invisibility, this paper focuses on one example of an environmental crisis that is reshaping gender relations on Australian farms. The Murray-Darling Basin (MDB) area of Australia is a large, traditionally highly productive area of Australia, known colloquially as the nation’s food bowl. This area is experiencing significant problems associated with water availability for irrigation farming following long years of drought and a historical over-allocation of water licenses. This has resulted in major ecological and river health issues, leading to government policies being introduced to recover water for the environment, which in turn reduces the amount of water available for irrigation farms in the Basin. Through a series of measures, water savings have necessitated sometimes radical changes in farm operations and this has had significant impacts on irrigation family farms across the Basin (

Alston et al. 2018). In a previous paper (

Alston et al. 2017), we noted that these negotiations have resulted in the emergence of a ‘farmer-manager’ role occupied by male farmers while women appear to be taking on a more ‘directed worker’ role. We noted that women’s work remains far less visible despite the fact that they appear to be increasing their workloads both on farms and away from the farm, securing much needed income through their off-farm work.

In this paper, we explore gendered labour adjustments further by documenting gendered changes in workloads on Australian family farms subsequent to the introduction of environmental water saving policies in the MDB. Given the historical invisibility of women in agriculture in developed countries, we provide a particular focus on women’s views in the context of their farm and community. We argue that despite women’s significant input to agricultural production on these farms, many continue to view themselves as agricultural outsiders. Before turning to our findings, and to contextualise women’s agricultural labour, we discuss the rich and ongoing feminist analysis of farm women in developed countries and outline global climate change experiences and predictions.

1.1. Women in Agriculture: Developed World Analysis

For over three decades, feminist analyses of farm women have addressed the invisibility of women engaged in agricultural production in developed countries (for an early feminist analysis see for example (

Rosenfeld 1986)). As we wrote in 2010 referring to feminist research on agriculture, these earlier researchers ‘addressed a set of issues: the gendered division of labour within households, women’s identities as farmers or farm wives, the economic contribution of women through their on- and off-farm work, women’s access to land and capital, and the virtual invisibility of women in agriculture’ (

Sachs and Alston 2010, p. 277), issues that continue to be relevant. Critically feminist theorists noted that family farms had previously been viewed as largely undifferentiated production systems in which women were ‘invisible farmers’ (

Sachs 1983;

Williams 1992). Thus, they argue that there has been very little acknowledgement of women’s work other than as a largely hidden ‘factor of production’ (

Whatmore 1991, p. 5). Farm women’s identities continued to be constructed around their most common entry point to agriculture: through marriage, and the notion of ‘wifehood’ has tended to shape the expectations of their role, particularly in relation to caring for, and enhancing, the wellbeing of other family members (

Sachs and Alston 2010, p. 279).

More contemporary feminist analyses of farm women across the developed world continue to expose the critical nature of women’s work to a farm enterprise, by focusing on the significance of gender to farming and the deeply embedded gender relations that shape, and are essential to, family farming. In so doing, feminists have facilitated a healthy critique of farm women’s invisibility (

Riley 2009); of the ideologies that prioritise male power and influence (

Brandth 2002a;

Price and Evans 2006); of hegemonic masculinity (

Knuttila 2016); of the patriarchal power and male privilege that shape both agriculture (

Shortall 1999) and gender identities on farms (

Brandth and Haugen 1998;

Haugen and Brandth 2017); of power, agency, and resistance (

Shortall 2017;

O’Hara 1998); of the masculination process and its links to technological developments (

Brandth 2002b); and of rural customs, such as patrilineal inheritance practices and farm organisational leadership roles, that continue to disempower women (

Bock and Shortall 2017;

Alston 2000).

While this research suggests that women are having a much more visible role in global food production, there are a number of factors that reduce the acknowledgement of their labour. Chief amongst them is the issue of land ownership, which is one of the key facilitators of the invisibility of women in farming. Patrilineal inheritance practices have dominated global agricultural resource ownership, leaving women’s chief point of entry to farming to be marriage. Globally, women own less than 10% of land, receive only 5% of all agricultural extension services, and have access to only 10% of total agricultural aid (

FAO 2013). In Australia, gender-disaggregated data on land ownership is scarce; however, research suggests that women inherit farm land in only 5–10% of cases (

ABC Rural 2016;

Dempsey 1992). Yet, as

Shortall (

1999) notes, ‘property is power’ and, because women rarely figure in agricultural land ownership, they have far less power in farm family agricultural units. At its most extreme, this lack of ownership and support can translate to reduced access to household goods and to greater food insecurity for women and girls (

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD 2015);

Pinstrup-Andersen 2009;

Alston and Akhter 2016). At the very least, it leads women to feel keenly the lack of acknowledgement of their work.

Research from several developed countries reveals that women’s labour remains a taken-for-granted, largely invisible factor in a structural system where gender relations are dominated by patriarchy and male privilege, and women’s work remains essential but masked (

Fletcher and Kubik 2016).

Sheridan and Haslam-McKenzie (

2009, p. 9) note that women’s invisibility in plain sight is partly explained by their role straddling the private world of the farm and the public world of the community: the ‘space of betweenness’ that reduces their legitimacy as farmers.

Additionally, could we not also argue that men are equally trapped in the prescribed role of the ‘good farmer’ (

Haugen and Brandth 2017), a role that when not fulfilled—for example when drought erodes agricultural expectations as it did in the Basin—it can lead to mental health consequences (

Alston 2012)? Does their ‘power’ have a downside when times are so tough? Perhaps we might also ask could climate change, when linked to climate-related policy developments and increases in women’s agricultural labour, be a point of departure from women’s invisibility? Will these changes give women increased agency and relieve the pressures on men to be exemplary, stoic, ‘good’ farmers? Or will recognition of their efforts be dampened by the lack of gender mainstreaming of policy and a failure to attend to the gender implications of policy developments and national responses to climate change in developed world economies? As

Prugl (

2010) notes, the state is Janus-faced and has the capacity to reproduce or challenge gender inequalities. It could potentially do this through gender mainstreaming of policies to assess the types of supports required by women and men to make the significant changes required by climate changes.

However, with the Murray-Darling Basin water reform process, the state has not only stood back from actions that might assist equality, it has also been ruthlessly gender-blind, and has committed to policies that appear to run counter to gender equality. Largely, this is because the neoliberalism underpinning policy developments in Australia have led to a retreat by government from any form of subsidisation of agriculture; a hands-off approach to policy development (

Alston et al. 2016); and reliance on markets to achieve environmental and social outcomes (

Hussey 2014). These processes in turn place pressure on individual farm units, and it is left to them—and the people who work there—to adjust to market forces by shaping their enterprise and labour accordingly. How then do the neoliberal market-based principles that underpin the Murray-Darling Basin Plan affect gender relations and labour allocation on Australian farms? Before turning to a discussion of the research, we describe the area that formed the basis of the study and examine climate change predictions.

1.2. Murray-Darling Basin Area of Australia

The Murray-Darling Basin is a large highly productive area that extends across much of the eastern area of Australia. It covers over 1 million square kilometres, or 14% of the country, and 23 river valleys and produces 40% of Australia’s agricultural produce (

MDBA 2010). Over 2 million live in the Basin and a further 1.3 million live outside the Basin but are dependent on Basin water (

MDBA 2010). In the Basin, there is one major city, nineteen urban centres with populations greater than 10,000, 159 small towns, and 230 small rural locations. A majority of these communities are reliant on agriculture (

MDBA 2010). In addition, a significant proportion of the population, particularly in the smaller communities, are employed in agriculture or food processing. The Basin sustains a variety of industries, many dependent on irrigation water. Thus, when environmental scientists expressed concerns about river health and ecosystem damage in the Basin following years of drought, this raised significant concerns across the Basin.

Previously, the state governments had been responsible for water; however, the problems identified in the Basin forced the national government’s hand and the 2007 Water Act (and its 2008 amendment) gave water responsibility to the federal government. Consequently, a number of water policies have been introduced by the federal government to increase the amount of water available to the environment. This necessarily requires the retrieval of water from agriculture, and hence there have been major disruptions in the Basin. However, it is important to note that despite a lack of trust in governance processes and increased uncertainty amongst water users, there is general acceptance of the need to address water concerns amongst all stakeholders, including irrigation farmers (

Alston et al. 2015). The Murray-Darling Basin Plan (

MDBA 2012) was released in 2012 after much disquiet being expressed by Basin people. Irrigation farm families and their communities were concerned about the fairness and justice of the processes to be implemented to save water.

Subsequent water policies have led to schemes, such as the buy-back of water licenses from farmers and the introduction of efficiency measures, to improve irrigation infrastructure and reduce water wastage. These have required significant investment by government, major adjustments by industries, and changes in farm production units across the Basin. In 2014–2017, we undertook a major study with dairy farm families in the southern parts of the Basin to ascertain how these changes were impacting the social sustainability of Basin communities. Arguably, this case study reveals the way climate-related drought conditions and a consequent need to deliver water to the environment have had a major impact on food production processes. This research provides a useful example of adjustments made in response to climate change. In this paper we narrow our focus to the impacts of a climate related event, and of water markets on gender changes in workloads on farms.

1.3. Climate Change in the Basin

There is no doubt that climate changes are having a significant impact on food production across the world and this will continue to affect farm production units. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (

IPCC 2014a,

2014b) predicts that the earth will become hotter and drier, that there will be more extreme weather events, increased temperatures, and a rise in sea levels across the globe. More frequent heat waves and extreme rainfall events will affect many parts of the world, and these will extend for longer periods, resulting in a negative impact on crop yields in many regions (

IPCC 2014a). Without attention to emissions reductions, the IPCC predicts that there is a significant likelihood of more severe and irreversible outcomes (

IPCC 2014a). The impact of these changes on food security will be critical. The

IPCC (

2014b) notes that there is a high risk of disruption to water supply and food production and that this will cause food insecurity, a breakdown in food production systems, and disruptions to food access, food utilization, and food price stability across the world.

Climate-related research in the MDB supports these global contentions. Researchers suggest that the temperatures in the Basin have increased by up to 1 degree since 1910 and that this is predicted to rise by up to 1.5° by 2030 (

Whetton 2017;

Timbal et al. 2015). This will lead to hotter days, increased periods of drought, less frosts, soil moisture and rain, and a harsher bushfire environment.

It should not be surprising then that climate-related events are changing agricultural industries, practices, and the agricultural workforce in the Basin and are accelerating socio-economic trends, such as a reduction in full-time employment (

To 2017), the outmigration of rural workers seeking alternative incomes for their families, together with a greater role for women in farm labour. In this paper, we note that while gender power relations persist, climate changes are reshaping work practices in agricultural units in developed countries along gendered lines. Our research with women and men on irrigated dairy family farms in the Murray-Darling Basin area of Australia provides one example of these changes.

3. Findings

A number of issues emerge from this research that suggest that climate changes are creating significant realignments in gender relations on farms. As we have noted previously (

Alston et al. 2017), the emergence of the ‘farmer-manager’ role undertaken by male farmers and the ‘directed worker’ role undertaken largely by women is evident. What is also apparent, and the argument that this paper develops, is that there appears to be a significant increase in women’s work hours on- and off-farm and this affects the way women view themselves and their roles on farms and in their communities. Yet, because this receives little recognition beyond the farm, there is limited acknowledgement of these changes and little policy development to address the issues this raises for women. Further, we note that women and men going through significant adaptations to climate-induced changes report significant health issues and these provoke further changes in gender dynamics.

3.1. Changing Work Roles

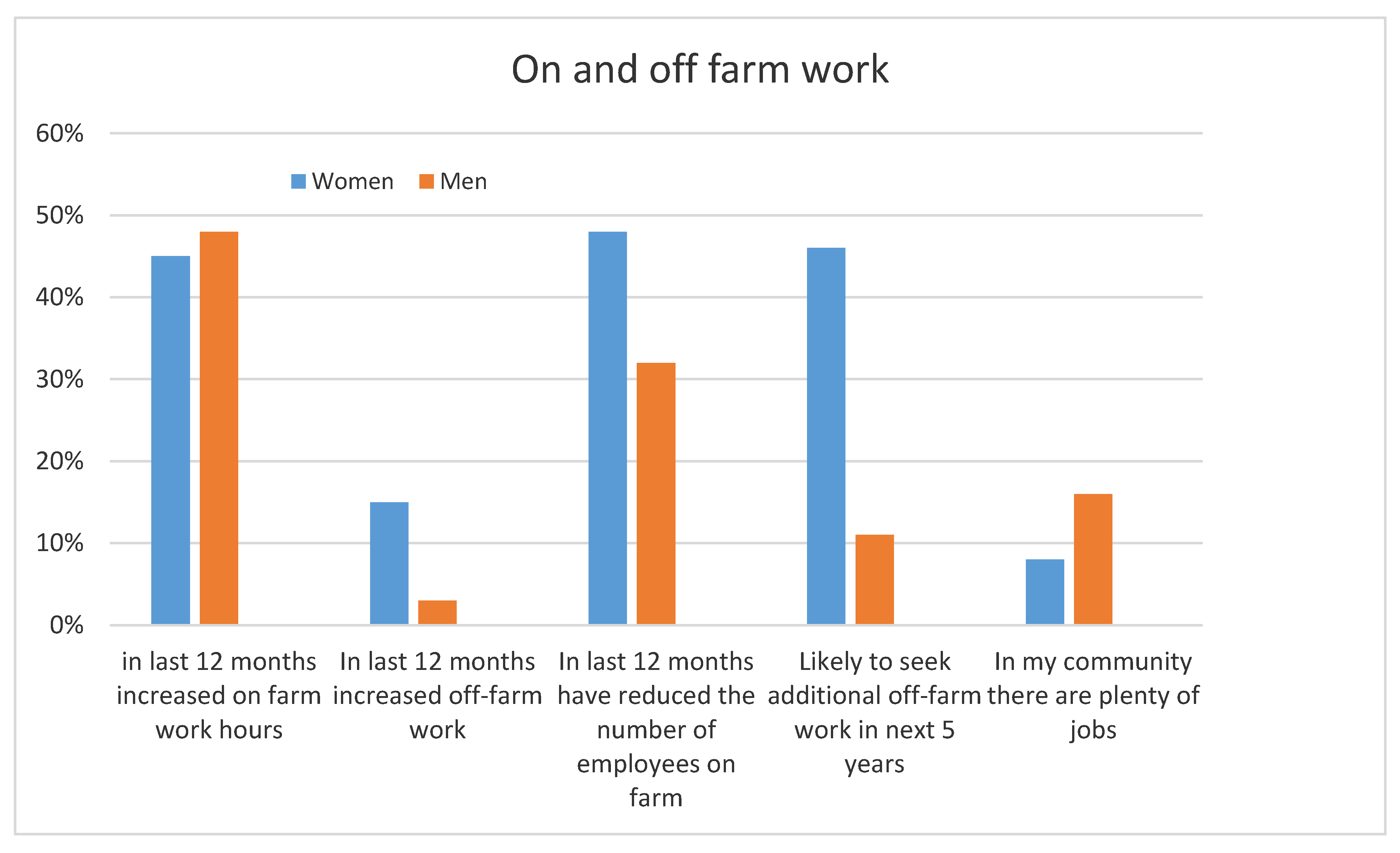

Our research reveals that there have been major changes in women’s and men’s work on farms and

Figure 1, outlining results from our quantitative survey, gives some indication of the way these changes affect both women and men. The change appears to be greater for women, many of whom have increased, or intend to increase, both their on- and off- farm work. More than half of the female survey respondents reported they had, or intended to, increase their off-farm work and their on-farm work. At the same time, a high proportion of women and men reported that the amount of hired labour on farms had been reduced, suggesting that more work is being absorbed within the family. Adding to the complexity of job-seeking off-farm is the fact that both women and men felt there were few jobs available locally and this will have a critical impact on access to paid work off the farm.

Figure 1 illustrates these issues.

As noted previously (

Alston et al. 2017), our qualitative interviews give additional insights into how individual women’s lives are being shaped by their increased workload. The following is from a young dairy farm woman who reported her workload as follows.

I do the most milking, [partner] helps me and we also have two others, we have [partner]’s mum that milks as well so I work with her predominantly and then we have people on the weekends to give her a spell … I do whatever else he tells me to do, which might be drenching cows, calves, seeding … So, it’s a lot, the bookwork is insane, it’s crazy … This is an 800 acre farm and we’re milking 550 cows, and just milking cows alone is 35 h, so 35 h of my week I’m just milking cows before I do anything else, before I do any bookwork, before I do anything on the farm, and I’m still doing stuff on the farm, so, you know, it’s just a lot, and the kids, so just everything. Stage 3 C1 10.

Other women reported on their off-farm work contributions, many noting its significance to the day-to-day survival of the family.

I’m working off farm because it does put food on the table, and that is a good thing. That is a good thing… But as far as running the farm’s concerned it doesn’t touch the edges. Not even close, it wouldn’t even touch a quarter of the interest. It might keep food on the table. And, it keeps me sane, because as much as it’s interesting to talk about the water I couldn’t do it all day every day. Stage 3 C1 5.

Older women sometimes noted the transition from hands on work to running the business management side of the farm as a stage of life transition.

Well, originally when we first started the farm I milked seven days a week and then did the farm work in the middle of the day and then did all the bookwork at night, and now I only fill gaps on the farm in terms of the physical roles, … Now I just do the financials, so that’s my main role and to keep on top of everything it really takes about three days a week to keep up with everything and the wages and the superannuation and any other staff issues, and paying bills and doing cash flows and keeping your finger on the pulse of where all that’s going and dealing with the banks and those sorts of things. Stage 3 C2 2.

Several women noted that farm work tasks are re-defined as domestic labour when taken over by women and therefore as an extension of their household tasks.

So, I think it is hard for women to see themselves as an equal because we’re seen as the wife, raising kids, washing clothes, and calf rearing, that’s the normal traditional woman’s job on the farm. … Oh yeah, and hosing out the [dairy] yard, that’s the other girl job. Stage 3, C1 5.

Men also refer to their increased workloads.

I’m out half the night watering … so that’s your tipping point, and you can’t put labour on to water at night. Because you already know where the water’s going from the day time you tend to be the one who goes around it again at night, and you can’t get a labourer to do it at two in the morning to go around and change that bay from one to the other, you can’t. Stage 3, C1 07.

3.2. Economic Pressures

The changes in the Basin and in the dairy industry more generally have had an impact on dairy prices and on the capacity of individual farm families to reshape a viable production unit. Farm families continue to adjust to the new realities, yet key informants confirm the economic pressures on families. This has had a significant impact on the way farm family members feel about their work and this too has a gendered dimension.

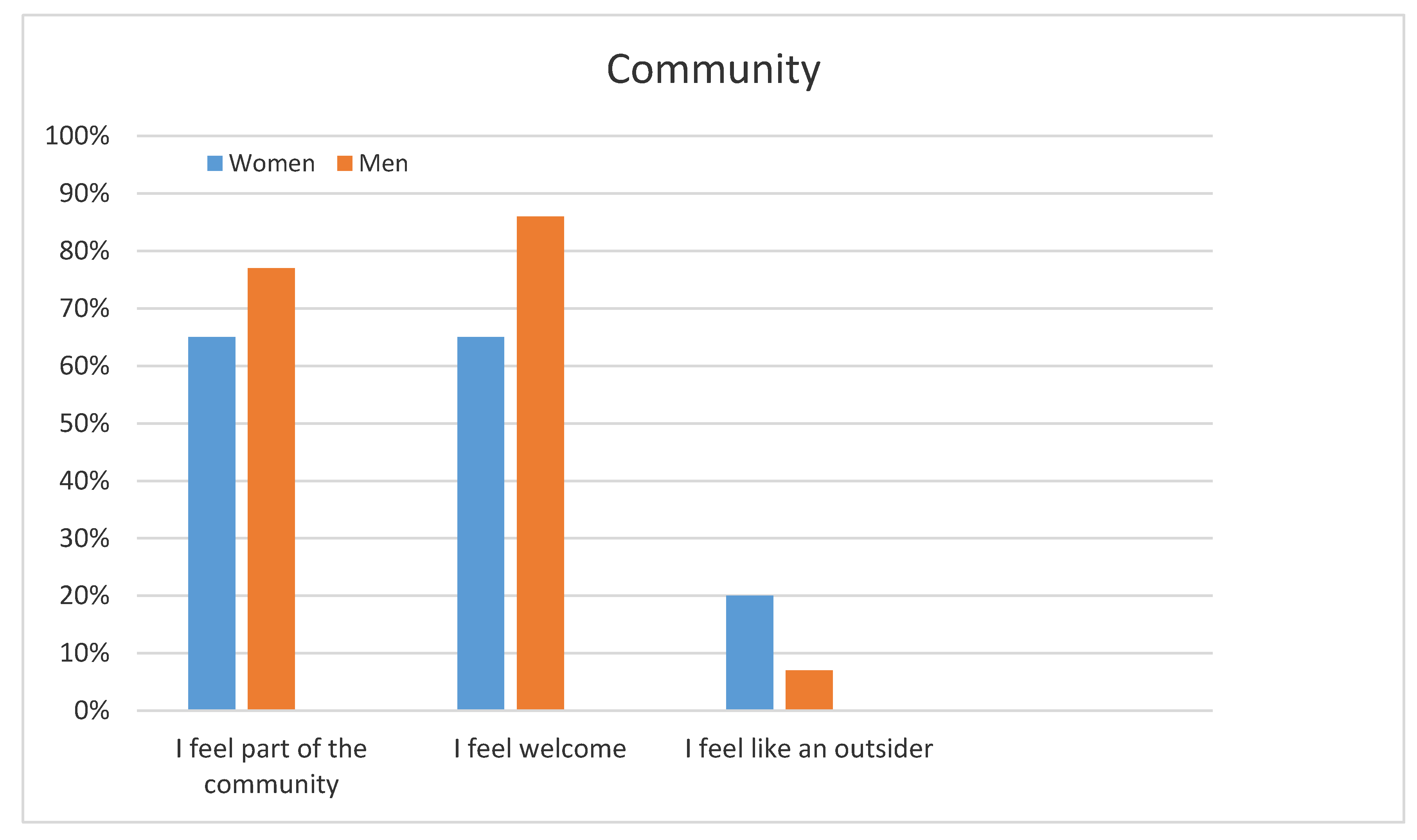

As illustrated in

Figure 2, women dairy farmers were more likely to report feeling less positive about the viability of their communities and hence the liveability of their environments. This translates into negative views held by women and men on the capacity of the Basin Plan ‘architects’ to understand their experiences. Women are less likely to feel positive about the community and local economy but were more trusting of government understanding their experiences.

3.3. View of Themselves

In both the survey and interviews, women were more likely than men to report feeling like an outsider (18% women, 4% men), and were less likely to report feeling welcome in their community or to be part of their community.

Figure 3 illustrates these points. This suggests that, because of their entry point to farming, and the consequent uneven power relations, women struggle with identifying themselves as farmers despite their workloads.

Qualitative data supports this view, with women commenting on the ‘blokeyness’ of both farming and farming communities.

Most of the women that I know have got young children so they’re sort of balancing feeding calves and looking after kids with not much support from the men. They are quite ‘blokey’ around here … it is really, really sexist. Stage 3 C1 5.

Others refer to the difficulties they have defining themselves.

I used to introduce myself, “I’m a dairy farmer’s wife,” and so [I say to myself], “No, you’re a full time professional dairy farmer, that’s what you should say you are, and when you meet men you shake their hand and say hello”. I shouldn’t have to do all that stuff really, I should be treated as equal but it is hard in probably a male dominated industry to step up, but there are some pretty good women who I talk to. Stage 2 C1 KI 7.

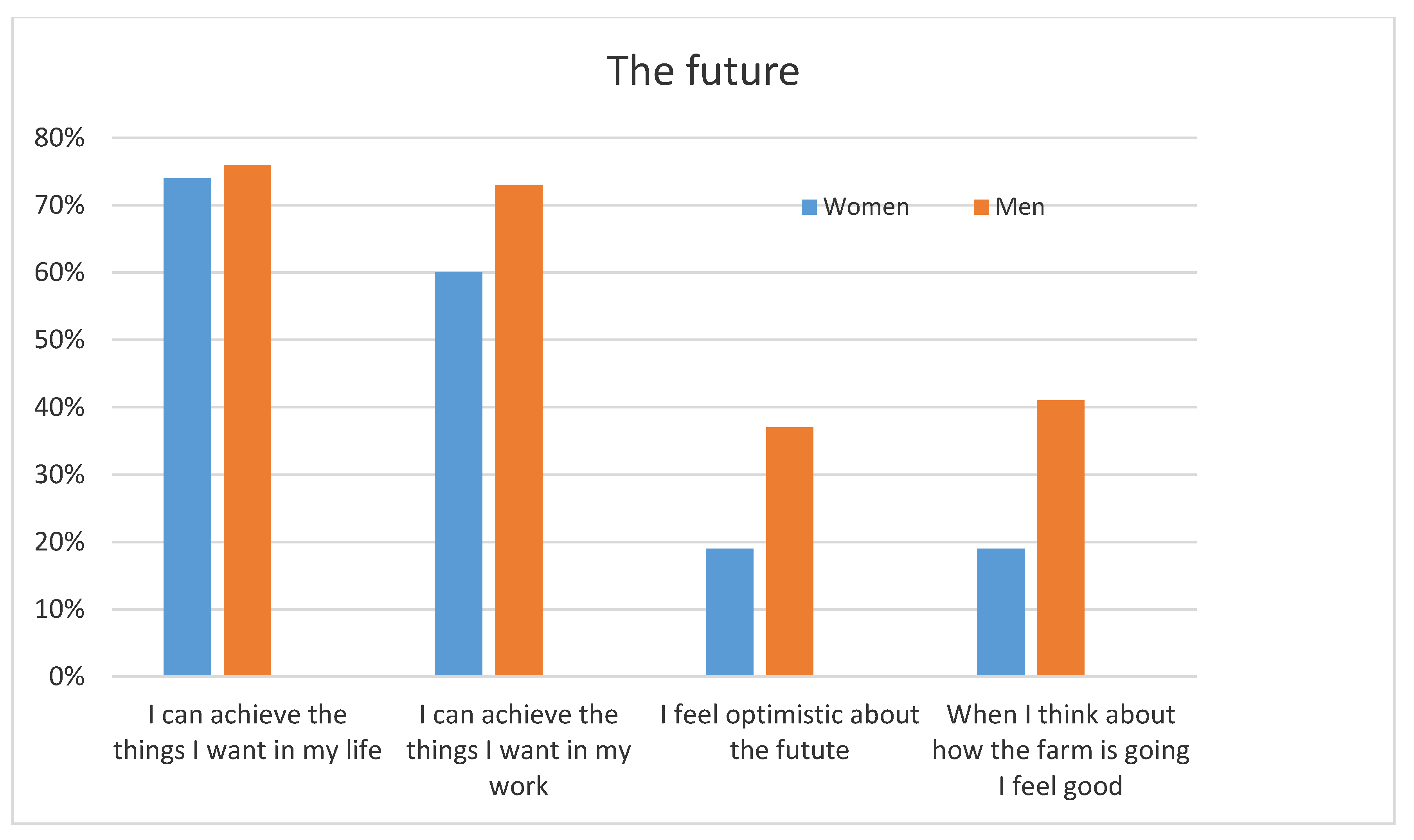

As illustrated in

Figure 4, while there is little difference in the expectations of women and men about being able to achieve life goals, there are marked gender differences expectations relating to work, optimism about the future, and feelings about the farm. The difficulties experienced by women in trying to define themselves appear to translate into lower expectations for women, lower levels of optimism, less positive views of the farm’s future, and less certainty that they will be able to achieve what they had hoped in their life and in their work.

3.4. Health Consequences

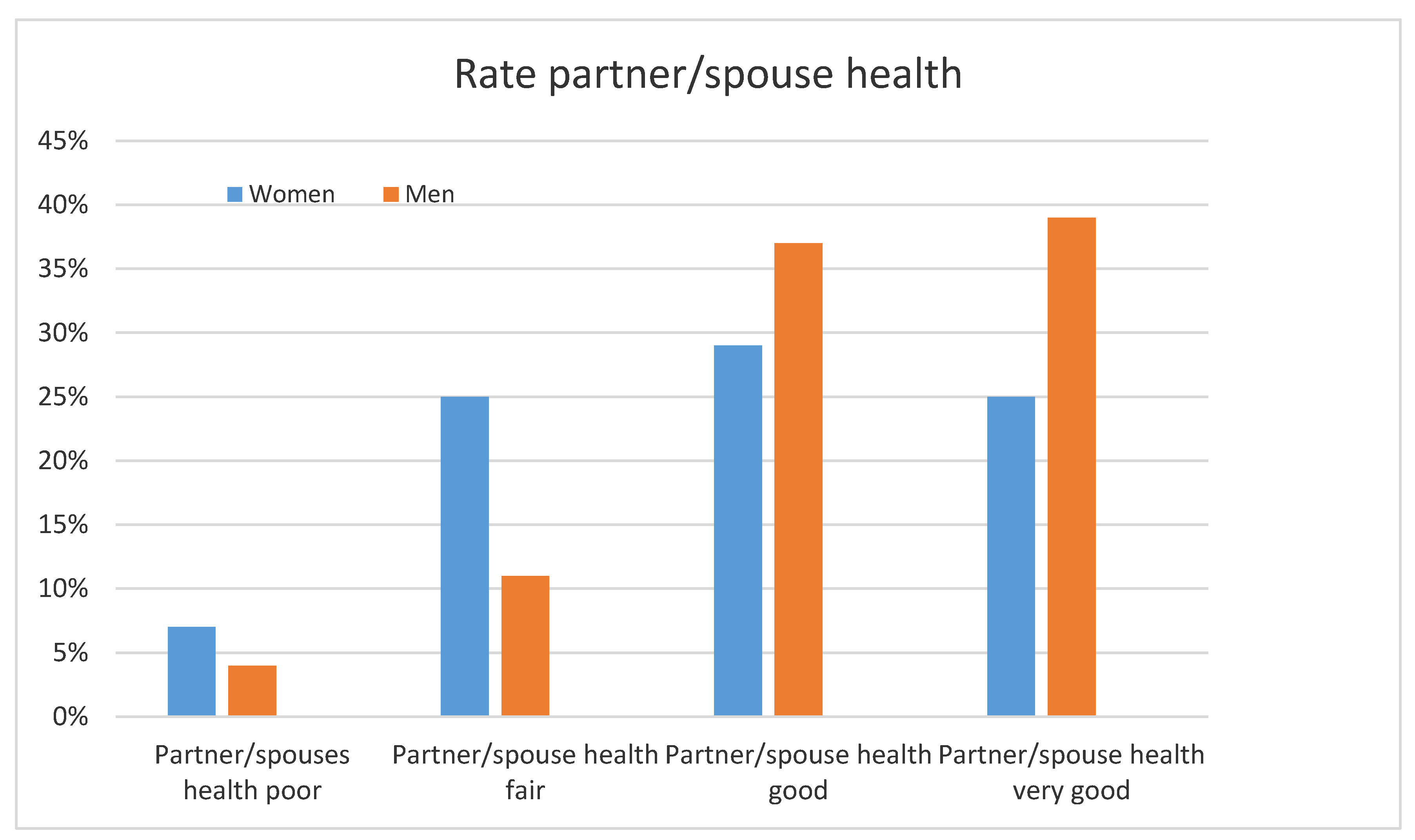

One of the most evident issues for farm family members going through the uncertainty of climate changes, the policies developed to address them, and drastic changes in livelihoods and labour is the health outcomes. Because women appear to be more conscious of the health of family members, this issue has a significant impact on gender relations and the compliance of women when family members are suffering. Women are more likely to discuss their men’s health and ignore their own, and they tend to rate their men’s health more poorly than men rate women’s health (see

Figure 5). Men rarely discuss women’s health in interviews and are more likely to report women’s health status more positively. This suggests not only that women continue to ignore their own health issues, but also that there are gendered differences relating to health and this adds to the complexity associated with livelihood adaptation.

Service providers within the communities also commented on the health of families.

we certainly found in the drought, the men didn’t often do much talking but the wives did, because they’re the ones that often carry the burdens—they carry it more on their sleeve and the guys tend to just go in the paddock and do what they’ve got to do. Stage 2 C3 KI 3.

Well, the impacts were obviously isolation, and depression was one of the big ones that we saw, and particularly back in the early to mid-2000s thereabouts, or … from probably 2001 through to about 2008 there were quite a few suicides across the region, we were seeing more and more wives presenting for health reasons, because the men didn’t present because they were too busy trying to either save what they had or buried themselves in their work. So, I guess overall health generally was what presented and obviously mental health was one of the big key themes. Stage 2 C3 KI 3.

One service provider pointed out:

We had a young fellow ring us up, who was just at his wits end, he’d been everywhere, they’d taken his water off him, and that’s according to him, they’d taken his water off him, his wife and kids had left him. Stage 2 C2 K1 2.

Health workers, education providers, and other key informants also commented on the impact on relationships, with many noting a rise in relationship breakdown, family violence, mental health issues, and the use of drugs and alcohol in their communities. In the survey, women were more likely to report that there is alcohol abuse (64% of women as opposed to 40% of men) and drug abuse in their community (56% of women as opposed to 39% of men).

What is evident from the interviews with both women and men is that men are experiencing significant mental anguish at the same time as women are actively monitoring the health of their partner. This supports the idea that men strive to be ‘good’ farmers and when they cannot achieve the ideal standard their mental health deteriorates. Women referred to how extreme this behaviour could be. Men withdraw, relationships suffer, and there may be self-medication with drugs and alcohol. Because women monitor their men closely, they may step in and take over farm tasks for periods of time as the following quotes indicate.

My husband was extremely depressed probably 12 months after we got married because it was really, really hard and financially it was very tough, and so I took over the managing of the farm and he would just milk the cows and drive tractors. Stage 2 C1KI7.

My husband he may as well have died, I reckon, nearly. He’d stopped milking and walked away, and didn’t pack anything up, it just looked like that. Now he would hate me saying all this, by the way, so lucky his name is not the same as mine. So yeah, that’s what it was like, it was devastating, and then it took about probably three years before he could even go back there to look at it because every time he went he would get so angry and devastated and watching it all fall apart, he just couldn’t handle it. Stage 3 C1 10.

As a result, it was not surprising that women were more likely to note the very real issues associated with a lack of specialist services, including mental health services.

Out here, between [town name] and [town name], no one can hear you, no one can see you properly, you’ve got to drive a couple of k’s down the driveway, and I think that’s really scary. So, there’s a lot of hidden stuff going on, and then the other professionals are almost scared and not knowing what to do … Stage 3 C1 5.

When men discussed their health issues in interviews, they invariably referred to mental health factors.

It’s always that male thing, we always struggle with going to the doctor and stuff like that, I reckon. I know in this area especially there is a lot more suicide and stuff like that, and I’ve had people that I know that have been in that position, so that’s a big issue, I think, mental health in general. Stage 3 C1 4.

When women discussed their health, it was more likely to note the bodily ailments that accompanied the increase in physical labour, particularly those affecting knees, hands, and backs.

We’re milking 550, it’s back breaking. Physically if I think about it, I’m milking those cows, it’s three and a half thousand, four thousand times I’m doing this a week, that on your body, doing that, you get sore shoulders, back problems, it’s hard, it’s hard work. It’s hard work but it’s not, do you know what I mean, it just takes its toll on you. Stage 3 C18.

As a result of the pressures on families, service providers were also likely to note that women are more likely to leave when the pressures are too great. This may be a result of their status as outsiders and ‘non- beneficiaries’ of farm inheritance practices.

The family breakdown that can happen because of the economic pressures, and wives will be more willing usually to cut losses and walk away than men will from farms … But on the whole it’s the women that will say, ‘I can’t take this anymore, I just don’t want to do it anymore’, and its often because they’re seeing the impact on their children … so mothers are more likely to be the ones who will say, “This is just not acceptable”, and want out from farms. And, you can see immediately the problem when one wants out and one wants in you’ve got a breakup of a marriage and then you’ve got the breakup of the farm, and then you’ve got all sorts of huge issues there. Stage 2 C1 KI 4.

In summary, while farm labour is reconfigured in response to climate events and subsequent policy changes, this is taking place against a background of complex health impacts. Women appear to be constantly monitoring family health, often while ignoring their own, and the changes have particular impacts on men’s health and family dynamics. These complexities may make it difficult for women to address gender negotiations as they may be reluctant to upset family dynamics further by challenging the status quo.

3.5. Government Response

The response of government to the climate-related environmental crisis in the Basin was to put in place complex water recovery strategies, and these addressed the identified crisis: the lack of environmental water. Governments acted in both an environmentally and economically responsible fashion and these actions were accepted by stakeholders as necessary and desirable. Yet what was not addressed were the social outcomes of these significant changes.

Thus to the outside observer, there appeared to be no government departments that acted as ‘champions’ for rural people and communities going through critical adaptations to climate-related stress. Further, there appeared to be no social analysis on factors such as employment, welfare, services, health, and other factors that shaped people’s responses. There were no obvious community development processes, no fostering of alternative industries, and limited attention to telecommunications and transport infrastructure. There was no gender mainstreaming of water policies, no gender analysis of outcomes to determine the issues affecting women and men, particularly on family farms, and hence no focus on child care services, mental health provisions, and employment development and training programs. Because there was no attempt to apply gender mainstreaming processes to water policies, there is limited institutional awareness of the gendered implications of the changes nor any analysis of the complex gender negotiations taking place on affected family farms.

As one industry leader noted:

I still believe there was this massive denial that taking the water out wouldn’t cause massive adjustment within communities, and I think the Commonwealth didn’t want to recognise it and it is still happening today. They just don’t want to face up to it as a consequence of their decision, they’ll say, “Oh well, the market will look after it, the water will trade from the low value users, so it won’t have much impact”, but it definitely had… Stage 1KI 46.

4. Discussion

While women’s work on family farms in developed countries has been largely invisible, we argue that climate changes, and consequent workload adjustments taking place on family farms, continue to marginalize women. Climate-related changes, such as temperature rises, less rainfall, and more periods of drought, leading to the reduction in the amount of water available for irrigation in the MDB, have created the need for farm production units to restructure their enterprises. One result is the increased workloads on- and off-farm being undertaken by women. There has been limited attention to, or acknowledgement of, changing gender workloads in the developed world and minimal focus on these gendered changes in the context of climate-related events.

It is perhaps no surprise then that when women are drawn into agricultural production as a result of the complex interaction of climate changes, recast agricultural production techniques, and renegotiated gender work roles, women’s input is treated as a ‘farm survival strategy’ rather than a major personal economic contribution by women to the enterprise (

Alston and Whittenbury 2014). Their tendency to relieve their partners of various work tasks in order to lessen emotional distress is largely hidden. Women’s increased involvement in agricultural labour is not necessarily a source of empowerment for women and appears to reflect the ‘feminisation of agrarian distress’ that

Pattnaik et al. (

2017) identified in their research. Further, as women move into increased farm work roles, society ‘reinterprets women’s new work through a heterosexual matrix’ and gender relations are reshaped and redefined in hierarchical ways (

Sachs and Alston 2010, p. 279). Thus, we find various tasks redefined as an extension of household tasks or of women’s nurturing role and not necessarily ‘work’. In this way, as

Prugl (

2010) writing about German farm women notes, patriarchy constantly reproduces itself in new ways to fit new circumstances and altered configurations of unequal power. Ultimately, this has repercussions for women’s capacity to influence not only the discursive constructions of family farming, but also power relations, labour allocations, and policies and practices relating to agriculture, climate changes, and rural communities that shape agricultural production on their farms.

Our research mirrors that of other male-dominated areas where women’s work is undervalued. Drawing on our research example in the MDB, we have established that climate change-related events and agricultural restructuring have significant gender implications for women and men on family farms in the developed world. For women, it continues a historical ignorance of women’s farm work, resulting in a lack of understanding, limited official acknowledgement, and a subsequent discounting of the labour contribution of women to agriculture. It also facilitates and continues the historical absence of women from leadership roles and fails to address the implications for service delivery and support strategies needed for viable adaptation. For men, the lack of services, including in particular mental health services, can lead to increased social isolation and despair. For women, the lack of child care services and limited training opportunities limit their adaptive capacity. We therefore argue that the lack of gender mainstreaming in climate change and water policies has significant implications for women’s continued invisibility and for women’s and men’s health and wellbeing.

We would argue the need for significant changes in the way women’s contributions to food security in developed countries are assessed, valued, recorded, and supported. This will require governments to respond more effectively to all members of farm families in the context of climate changes. What is needed in affected areas, such as the MDB, is a whole of region development plan incorporating gender equality, community development, and a supportive service infrastructure to assist families adapting to changes that are beyond their control. It is insufficient to expect markets to be the sole determinant of people’s capacity to adapt. As we have argued elsewhere (

Shortall and Alston 2016), this necessitates a ‘rural champion’: a dedicated government department that focuses squarely on rural development, and one that incorporates attention to gender mainstreaming during increasingly prevalent climate-related changes.

When we view this research in the context of farm women’s historical invisibility, it is perhaps not surprising to see complex gender negotiations occurring in the private family sphere being ignored by industry and government. The history of farm women is peppered with extensive research indicating not only their invisibility, but also the continuation of the public view of farming as a male occupation. Thus, women’s efforts go largely unnoticed beyond the farm gate and this creates significant personal tensions for women. As a result, women feel less optimistic about their futures and more like outsiders in agricultural industries that cannot operate without women’s labour. While women have increased their efforts in the wake of climate and policy changes, state and industry bodies continue to operate in an environment that ignores gender. The continuing male dominance of industry bodies, the lack of gender mainstreaming in climate and agricultural policies, and the total disregard of the need for supportive social policies for families and communities making significant adjustments confirms that gender equality is unimportant to those with the power to effect change. As we argue in this paper, women’s work on farms has become more essential at the same time as it has become more hidden and the additional factor of a changing climate is significantly increasing the uncertainty experienced by farm families. Attention to gendered relations is essential if we are not only to avoid the continuation of the invisible farmer tradition, but also to ensure food security. Feminist scholars must continue to expose gender inequalities in agriculture and food production in the developed world and argue strongly for gender mainstreaming in agricultural and climate-related policies.